-

Peptide signaling plays a central role in coordinating plant development and environmental responses. Among various classes of plant peptides, the CLE (CLAVATA3/EMBRYO SURROUNDING REGION-RELATED) family represents a major group with important functions in regulating plant development, growth, and stress responses[1−4].

CLE peptides are typically 12–14 amino acids in length, derived from larger precursor proteins via proteolytic processing[5]. These peptides are perceived by membrane-localized leucine-rich-repeat receptor-like kinases (LRR-RLKs), such as CLAVATA1 (CLV1)[6], BARELY ANY MERISTEMs (BAMs)[7,8], and PHLOEM INTERCALATED WITH XYLEM (PXY)/TDIF RECEPTOR (TDR)[9−11], forming ligand-receptor modules that regulate cellular communication and tissue patterning.

In the last two decades, a wealth of studies has uncovered the vital functions of CLE peptides in maintaining shoot and root apical meristems (SAM and RAM)[12−40], regulating vascular and reproductive development[36,41−46], and mediating adaptive responses to environmental stresses[47−51]. Notably, CLE signaling often intersects with phytohormone pathways, such as cytokinin[52,53], auxin[15,54], and brassinosteroids[55], to fine-tune plant development under fluctuating conditions. The availability of synthetic CLE peptides, transcriptome datasets, and genome-editing tools has significantly advanced our understanding of CLE function and dynamics.

Here, we systematically review the current understanding of CLE peptides in regulating plant development and stress responses. We begin by discussing their roles in development and then highlight their roles in nutrients and abiotic stress responses. Lastly, we examine CLE crosstalk with classical hormones and outline challenges and perspectives for future research.

-

CLE proteins share several conserved structural features, including a signal peptide at the N-terminus for secretion, a variable domain, and a highly conserved CLE domain at the C-terminus[56]. The 12-amino acid (aa) CLE motif is central to the diverse biological roles of these peptides and are typically conserved across species[56]. Synthetic CLE peptides corresponding to this conserved sequence can mimic gene overexpression phenotypes. For instance, exogenous applied synthetic CLE7 or overexpression of this polypeptide both significantly inhibit the infection of multiple RNA viruses in plants[57]. Overexpression of tracheary element differentiation inhibitory factor (TDIF)/CLE41, or exogenous application of TDIF peptide inhibits xylem differentiation in Arabidopsis[58,59]. Domain-swapping studies indicate that the 12-aa peptide alone is sufficient for in vivo function. For example, treatment with synthetic CLV3 peptide and CLE40 peptide resulted in a clear reduction in root length, similar to CLE19 peptide in vitro[60], confirming the central role of the CLE motif as the primary bioactive component in CLE signaling.

Interestingly, in some plants and nematodes, CLE precursor proteins exhibit an unusual structure with multiple CLE motifs within a single precursor protein. This structural feature likely supports high-efficiency peptide production. For example, CLE precursor proteins in Oryza sativa (rice, such as OsCLE502, OsCLE504, or OsCLE506), Triticum aestivum (wheat), and Medicago truncatula, contain multiple CLE domains separated by polyproline linkers[61]. These polyproline regions may influence peptide maturation by facilitating sequential cleavage and activation of CLE motifs[61]. This unique arrangement may enable plants to produce multiple signaling peptides from a single precursor, improving efficiency and regulatory flexibility. However, further studies are needed to fully elucidate the processing and activation mechanisms involved.

In addition, structural diversity is obvious in CLE domain positioning. For example, the Arabidopsis CLE18 precursor contains a central CLE domain and a CLE-like (CLEL) motif near the C-terminus[56]. Overexpression of the full-length CLE18 precursor enhances root elongation in comparison to the empty-vector control, with the CLEL motif responsible for wavy and elongated root traits[62]. However, the synthetic 12-aa peptide from the variable CLE motif region functions significantly differently, the application of the synthetic peptide resulting in a short root phenotype contrasting with the inhibitory effects on root growth[63] observed with the CLE domain alone. Eight other homology CLE-like peptides from CLEL1 to CLEL9, except CLE18, which share a similar CLE domain, may function the same with CLE18[63]. This functional bifurcation suggests that differential positioning and cleavage of CLE domains may provide distinct signaling cues, adding complexity to CLE peptide signaling.

Post-translational modifications and receptor specificity

-

Post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as hydroxylation and arabinosylation, are common in CLE peptides and play important roles in maintaining their stability and specificity in receptor binding[64−67]. These PTMs are essential for the functional diversity of CLE peptides. For instance, hydroxylation of proline residues enhances the binding affinity of CLE peptides to CLV1 receptors, which are crucial for SAM regulation[68]. In addition, distinct CLE peptides selectively bind to different receptor-like kinases (RLKs), such as CLV1, CLV2/CRN, and BAM1, enabling them to elicit unique signaling outputs and regulate tissue-specific functions[19]. Recent mass spectrometry results have also revealed that the arabinosylation modification of the proline residues is crucial for receptor binding, RDN1 can mediate the arabinosylation activation of MtCLE12 receptor CLV1 to participate in the SUPER NUMERIC NODULES (SUNN) perception[66]. In tomato, SlCLE11 suppresses the arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) colonization of roots after arabinosylation[65]. These results demonstrate the importance of post-translational modifications in CLE peptide function.

Conserved mechanism for recognition of CLE peptide and receptors

-

Recent structural analyses have revealed that tri-arabinosylation of hydroxyproline (e.g., CLV3, MtCLE12) is critical for receptor binding[66,69]. Detailed structural studies of the TDIF-PXYLRR complex show that TDIF adopts an 'Ω' -like conformation when interacting with PXYLRR[9,70,71]. Amino acids Hyp4, Gly6, Hyp7, and Pro9 of the TDIF peptide form the 'Ω' -like structure, and these four amino acid residues are highly conserved among CLE peptides.

Alignment of several receptor sequences, including PXY, CLV1, BAM1/2, STERILITY-REGULATING KINASE MEMBER 1 (SKM1), and PXY-LIKE1 (PXL1), reveals that these receptors contain similar motifs predicted to interact with CLE peptides. Mutation of Asn12 at the C-terminal of TDIF disrupts the interaction with PXYLRR[9,70,71]. For instance, mutations of two Arg residues (421 and 423) at the PXY site affect its interaction with SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE 2 (SERK2), which leads to being unable to activate the downstream signaling pathway. Genetic complementation assays in vivo confirmed the importance of these two residues in vascular development[9,70,71], as supported by the observation that PXY with mutations in these two Arg (PXYR421A/R423A) failed to rescue the defect phenotype of the pxy mutant. Importantly, this Arg-x-Arg motif is conserved in CLE receptors, which is evidenced by recent work on CLE19-PXL1-SERKs ligand-receptor-coreceptor complex in pollen walls[72]. The CLE19-PXL1-SERKs complex has been demonstrated to be critical in maintaining pollen wall developmental homeostasis[72]. The R417 and R419 sites of PXL1 are predicted to be in the PXL1-CLE19 interaction surface, and mutation of these two sites abolished the PXL1's activation by CLE19, and the interaction between PXL1 and its coreceptor SERK1[72]. These findings suggest that CLE receptors share a conserved mechanism for ligand recognition and receptor activation.

-

One of the earliest and best-characterized functions of CLE peptides is the maintenance of stem cell homeostasis in the SAM[62]. The SAM of plants contains a central organizing center that maintains the identity and activity of the stem cell reservoir[39]. The canonical CLE peptide CLV3 is expressed exclusively within the shoots and floral stem cell reservoir[39], and plays a central role in SAM homeostasis (Figs 1 & 2a). Through binding to its receptor/co-receptor complexes and activating downstream signaling components, CLV3 limits the expression of the homeo-domain transcription factor gene WUSCHEL (WUS), and thereby regulates the SAM stability by restricting stem cell populations in the SAM[22].

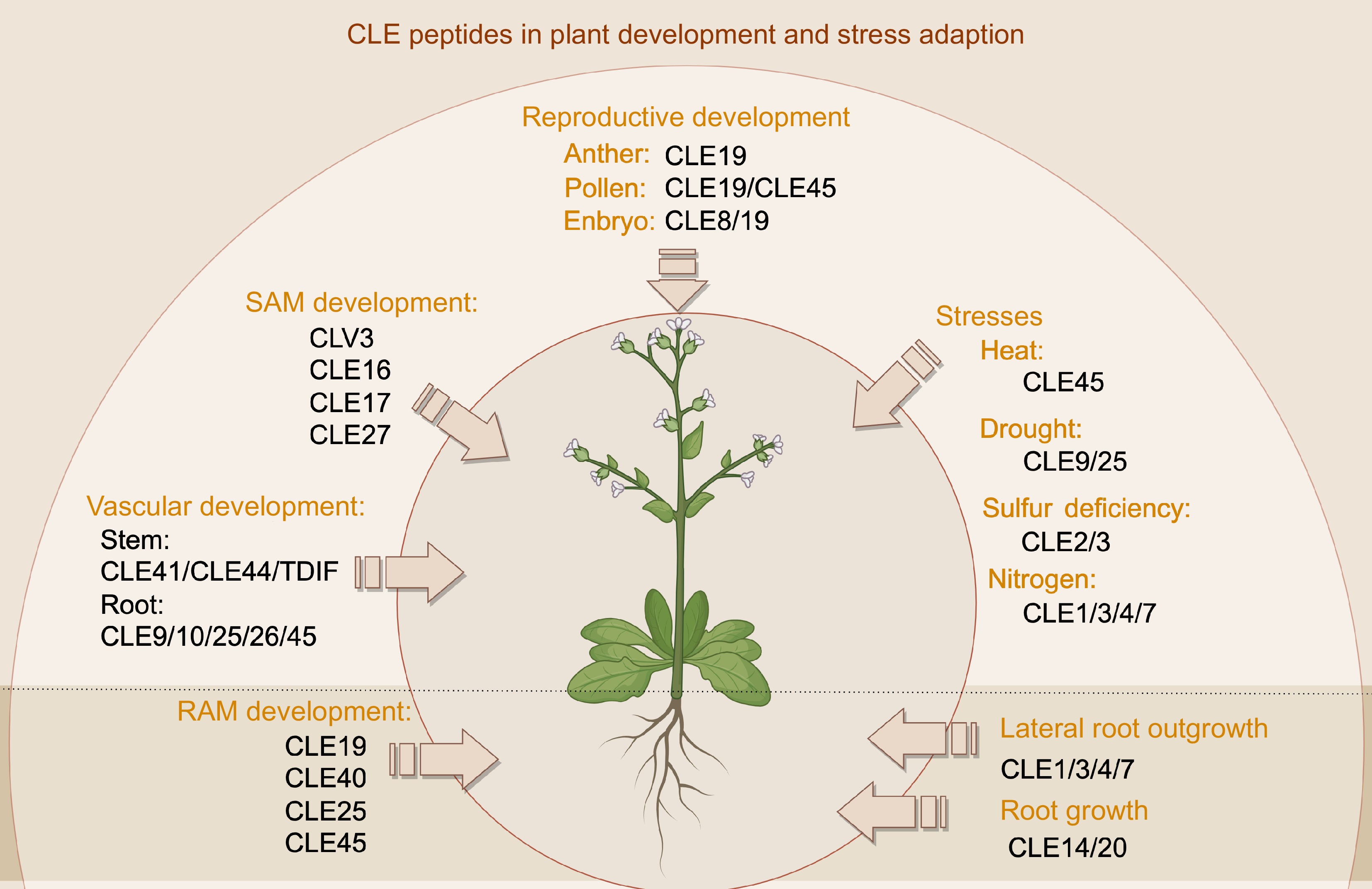

Figure 1.

CLE peptides' functions in plant development and stress adaption. CLE peptides play critical roles in both tissue development and stress response processes. They regulate key aspects of meristem maintenance, vascular and reproductive development, while also mediating plant adaptation to environmental stresses such as drought and temperature fluctuations.

CLV3 restricts the expression of WUS through multiple receptor kinase complexes, such as CLV1-CLV2-CLAVATA3 INSENSITIVE RECEPTOR KINASE (CIK)-CORYNE (CRN), CLV1-CIKs, BAM1-POLLEN RECEPTOR LIKE KINASE (PRK2)-CIKs, and CLV2-CIKs. There are distinct functions of these receptor complexes (Fig. 2a). For instance, the restriction of WUS expression by CLV3 in the primordia zone is mediated by the BAM1 receptor, whereas in the organizing center, it is mediated by CLV1/CIK. Moreover, the RPK2/CIK receptor kinases function in the periphery zone, the organization zone, and regulate the stability of G proteins on the plasma membrane. In comparison, CLV2/CIK/CRN receptors respond to CLV3 and regulate WUS expression throughout the SAM development. After being activated by CLV3, these receptor/co-receptors activate PBS1-LIKE 34/35/36 (PBL34/35/36) kinases and/or MAPK cascade to suppress WUS transcription (Fig. 2a).

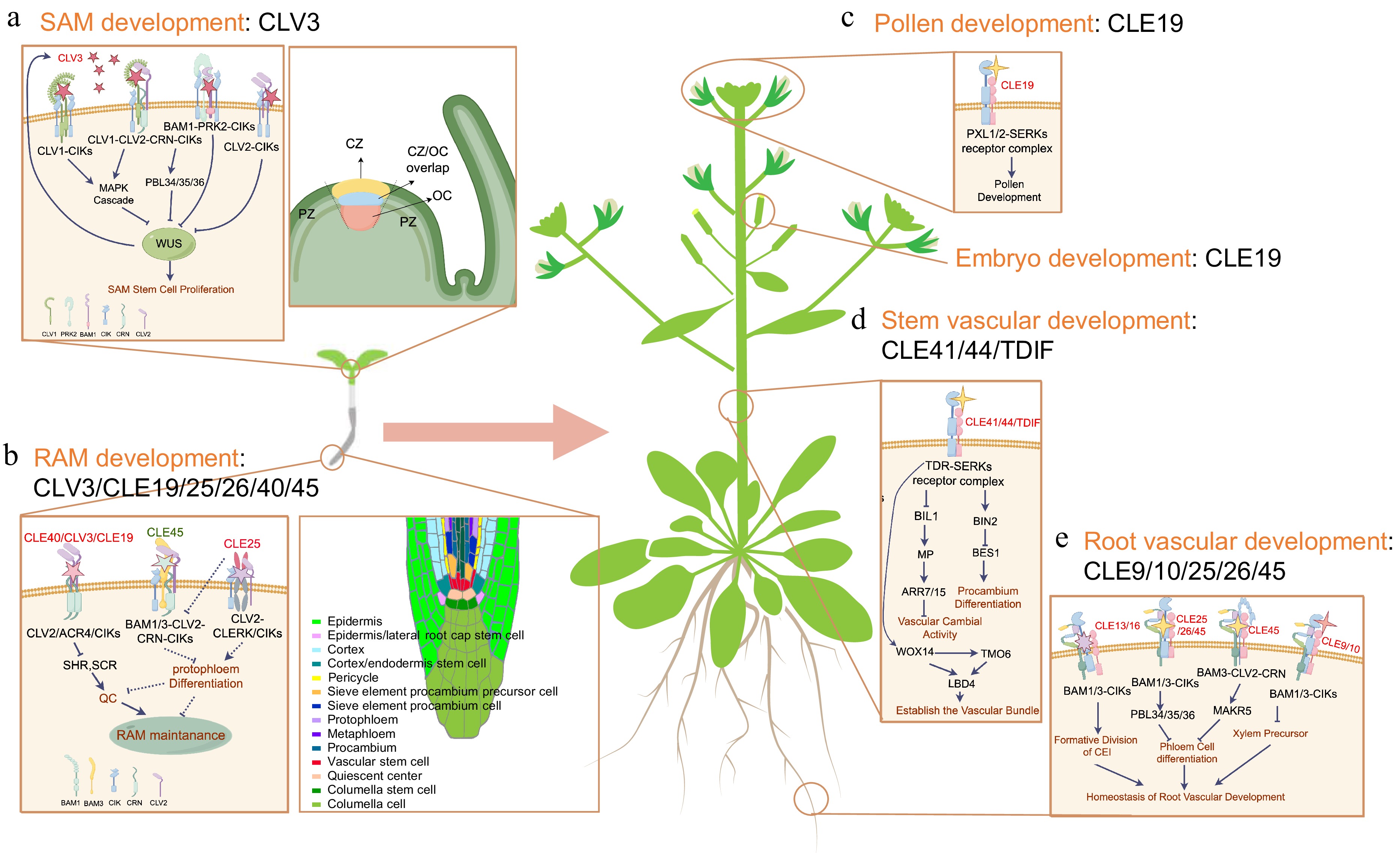

Figure 2.

CLE signaling pathways in regulating plant development. (a) CLV3-WUS feed-back regulatory loop in the organization of shoot apical meristem (SAM). Mature CLV3 peptide binds to the plasma membrane (PM)-localized receptor-coreceptor complexes to restricts WUS expression through the MAPK cascade, the receptor like cytoplasmic kinases PBS1-LIKE34/35/36 (PBL34/35/36), and other unknown downstream pathways. (b) CLE signaling pathways involved in root apical meristem (RAM) maintenance. The RAM is composed of quiescent center (QC) cells, stem cells surrounding the QC, and different cell layers derived from stem cells. CLE40/CLV3/CLE19 induce terminal RAM differentiation through CLV2-CRN receptors. CLE45 suppresses protophloem differentiation through the BAM1/3-CLV2-CRN-CIKs receptors and finally promotes RAM maintenance. CLE25 promotes the protophloem differentiation through CLV2/CLERK(CIKs) receptors and finally represses RAM maintenance. Moreover, CLE25 suppresses the activity of CLE45 receptors through OPS. These CLEs and related signaling pathways together maintain the RAM homeostasis. (c) CLE19 regulates pollen development through its PXL1/2-SERKs receptor-coreceptor complexes. (d) The CLE41/44/TDIF-TDR-SERKs peptide-receptor-coreceptor complex controls stem vascular development by coordinating the proliferation of vascular cells and establishing the precise position of vascular boundaries. CLE41/44/TDIF-TDR signaling interacts directly with the GSK3 family member BRASSINOSSTEROID-INSENSITIVE 2 (BIN2), and inhibits the activity of transcription factor BES1 to prevent procambium differentiation into xylem. Additionally, it inhibits the activity of another GSK3 family member BIN2-Like 1 (BIL1), which phosphorylates and activates the auxin response factor MONOPTEROS (MP), and subsequently induces the expression of ARR7 and ARR15 to repress vascular cambial activity. The WOX4-TMO6-LBD4 feed-forward loop acts downstream of CLE41/44/TDIF-TDR signaling to establish the vascular boundary. (e) CLE9/10/25/26/45 regulates the root vascular development through multiple receptor-coreceptor complexes, including BAM1/3-CIKs, BAM3-CLV2-CRN, and other downstream signaling components.

Notably, the function of CLV3 peptides in SAM is highly conserved across plant species. In rice, the CLV3 homologous proteins FLORAL ORGAN NUMBER 2 (FON2), and FON2-LIKE CLE PROTEIN1 (FCP1), also function in regulating SAM development[33]. 1,628 CLE genes are identified in 57 land plant species, with none from green algae[73]. Even the pteridophyte plant Selaginella moelendorffii has 15 putative CLE genes in its genome[74]. But interestingly, homologues of the CLV3 receptor CLV1 were identified in Selaginella moelendorffii and a moss, Physcomitrella patens, as well as in flowering plants, Arabidopsis, rice, Populus trichocarpa, and Vitis vinifera; but the SUPPRESSOR OF LLP1 2 (SOL2)/CRN, and CLV2 homologues are not identified in Selaginella moelendorffii and Physcomitrella patens[10,73,74], suggesting that the CLE-CLV1 pathway is conserved in the whole land plant kingdom, whereas the CLE-SOL2/CRN, and the CLV2 pathway likely has specific roles in vascular plants.

RAM development

-

RAM is crucial for root growth and development (Figs 1 & 3b). In Arabidopsis, CLE peptides, including CLE1, CLE7, CLE13, CLE19, CLE25, CLE40, and CLE45, are specifically/preferentially expressed in roots and play important roles in RAM maintenance, cell differentiation, and root growth[75]. Overexpression of CLE19 and CLE40 causes premature termination of the root meristem, often linked to enhanced cell differentiation rather than proliferation[60]. Specifically, over-expression of CLE19 significantly diminishes the root meristem, likely by inhibiting cell division or promoting cell differentiation[60]. Similarly, overexpression of CLE40 results in terminal differentiation of root meristem cells, whereas its loss-of-function mutants exhibit unusual root waving. Synthetic peptides that mimic the CLE motifs of CLV3, CLE19, and CLE40 replicate these effects when applied exogenously to roots, promoting premature differentiation of ground tissue cells, while leaving the quiescent center (QC) intact[60].

The QC in RAM serves as an organizer by promoting stem cell fate in adjacent cells (Fig. 2b). CLE40 signaling originated from differentiated root cap cells and plays a key role in regulating QC activity, and late metaxylem formation[76,77]. Through interacting with ARABIDOPSIS CRINKLY4 (ACR4)/CIK kinases, CLE40 maintains the distal root meristem through the WUSCHEL-related homeobox 5 (WOX5) transcription factor, and downstream gene networks (Fig. 2b). Additionally, the TPLATE complex-dependent endocytosis is involved in attenuating CLAVATA1 signaling which is essential for both root and shoot meristem maintenance[13,78]. This indicates the shared regulatory mechanisms between the RAM and SAM, where CLE peptides and receptor kinases are key players[11,21,22,77−79].

The CLE25 peptide also plays an important role in RAM maintenance, particularly in regulating protophloem cell differentiation. Exogenous application of CLE25 suppresses root growth in wild-type plants[8,80], and overexpression of CLE25 leads to the formation of miniature roots, demonstrating the importance of CLE peptides in root development[75]. The BAM-CIK receptors are required for perceiving CLE25 peptide, and govern protophloem differentiation and proximal root meristem consumption. Mutants with defective BAM and CIK function show insensitivity to CLE25[7,81]. Furthermore, the CLE33 peptide represses phloem differentiation in the RAM, especially when CLE25, CLE26, and CLE45 are mutated[82]. While CLE25 signaling promotes phloem differentiation, CLE45 inhibits it by suppressing cell wall thickening in root cells.

Emerging structural analyses of CLE peptides like CLV3, CLE14, CLE19, and CLE20 have revealed their interaction with receptor complexes such as CLV2-CRN heterodimer, or heterotetrametric complex, offering new insights into their signaling mechanisms. CLE14 and CLE20 peptides inhibited root growth by reducing cell division rates in the RAM[32]. In Selaginella kraussiana, RAM development is guided by auxin signaling, with the rhizophore primordium initiating the RAM[15]. TDIF inhibits xylem differentiation in Arabidopsis. Homolog of TDIF and its receptor TDR/PXY were also found in Adiantum aethiopicum, Ginkgo biloba, and Selaginella kraussiana[10]. TDIF treatment also suppresses the differentiation of xylem in element in Ginkgo biloba and Adiantum aethiopicum. On the contrary, neither extra applied TDIF, nor endogenous TDIF, inhibited the lignification of new shoots and rhizophores of Selaginella kraussiana[10].

CLE26 influences auxin distribution in the RAM, and inhibits protophloem development. Interestingly, synthetic CLE26 peptides have been shown to affect root architecture in Brassia napus and Solanum lycopersicum[54]. In the moso bamboo, Phyllostachys edulis, PheCLE1 and PheCLE10 are highly expressed in the RAM, according to single-cell transcriptomic data and in situ hybridization, and overexpression of PheCLE1 and PheCLE10 in rice significantly enhanced root elongation[83]. These results together suggest the function of CLE peptides in RAM development is conserved across land plant species.

Vascular development

-

CLE peptides play crucial roles in vascular development in both stems and roots, including the formation and differentiation of the xylem and phloem (Figs 1 & 3d−e). Particularly, CLE41 and CLE44 promote tracheary element differentiation[64], whereas CLE26 and CLE45 regulate protophloem differentiation, which is essential for efficient nutrient transport and vascular patterning[43].

The vascular stem consists of a narrow strip of meristematic cells known as the vascular cambium or procambium. The procambial cells undergo highly coordinated division to generate the xylem and phloem. The activity of procambial cells is tightly regulated by the TDIF, which is a peptide homologous to Arabidopsis CLE41 and CLE44 (Fig. 2d)[64]. These ligand-receptor interactions prevents premature differentiation of vascular stem cells into xylem[64]. Structural analyses reveal that TDIF binds to the LRR4 and LRR5 domains of TDR, and triggers the heterodimerization of TDR and SERK1[9,70,71].

The WOX4-TMO6-LBD4 feed-forward loop acts downstream of the TDIF-TDR signaling pathway (Fig. 2d). TDIF-TDR activation induces WOX4 expression, which subsequently activates the expression of TARGET OF MONOPTEROS 6 (TMO6). In turn, WOX4 and TMO6 together enhance the expression of LATERAL ORGAN BOUNDARIES DOMAIN 4 (LBD4) at the interface of the procambium-phloem[44]. This regulatory module coordinates the proliferation of vascular cells, and establishes the precise position of the vascular boundary.

Comparative analyses showed that the TDIF/CLE and its receptor TDR/PXY are conserved across vascular plants, including non-flowering lineages[10]. This conservation highlights their fundamental role in the evolutionary adaption of vascular development[42].

In roots, xylem cells originate from vascular precursor cells within the RAM and divides further to establish the longitudinal axis of the root. CLE9/10 peptides are expressed in the xylem precursor cells, and act as negative regulators of root xylem cell proliferation[41]. Loss-of-function mutants deficient in CLE9/10 exhibit excessive periclinal cell divisions within the xylem axis, leading to the overproduction of xylem vessels and aberrant vascular architecture[84]. The receptor-like kinases BAM1 and BAM2 serve as central regulators of CLE9/10 peptides, modulating asymmetric cell division within xylem precursor cells (Fig. 2e)[52,56,85]. This regulation mechanism is crucial for ensuring proper vascular differentiation, and reinforcing the balance between proliferation and differentiation during both root and shoot development.

Flowering time and vegetative-to-reproductive phase transition

-

CLE peptides play emerging roles in plant reproductive development, influencing floral bud formation[11,86], pollen development[87], pollen tube growth[49], and embryo patterning[79].

In Populus trichocarpa, overexpression of PtCLE9 enhances vegetative growth in both basal and aerial rosettes by regulating the expression of AERIAL ROSETTE 1 (ART1), and FRIGIDA (FRI), which are associated with flowering time regulation. Moreover, PtCLE9 peptide influences the downstream FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) gene, a well-known regulator of flowering[86]. These changes suggest that the PtCLE9 peptide may play a role in flowering, particularly through its regulation of genes that control flowering time and vegetative-to-reproductive phase transitions.

Similarly, in addition to acting as inhibitors of tracheary element differentiation, TDIF and CLE41/42 are also involved in secondary shoot development, and axillary bud formation via their interaction with the TDR[11]. Overexpression of CLE41/42 enhances axillary bud formation, and exogenous supply of either TDIF or CLE42 peptide to the wild type induces similar excess bud emergence. In contrast, the axillary bud emergence of tdr mutants was little affected by either of the peptides[11]. These observations support that TDIF/CLE41/42-promoted meristem activity and axillary bud formation is TDR-dependent. While this does not directly implicate their function in flowering time regulation, they could potentially influence processes related to flowering through modulation of shoot and meristem development. However, this requires further research to directly connect CLE41/42 with flowering time regulation.

Floral organ number is closely associated with floral meristem size. In Oryza sativa, the Arabidopsis CLV1 homologous gene FON1 regulates floral meristem size[46]. FON2, which encodes a small secreted protein with a CLE domain, influences the number of flowers and floral organs in rice[36]. In contrast, mutants of ZmCLE7 produce an enlarged inflorescence meristem[45], suggesting that OsFON2 and ZmCLE7 regulate distinct meristem types. However, the functional similarity between SvFON2 in Setaria, and ZmCLE7 in maize, suggests a conserved mechanism for inflorescence meristem regulation in panicoid grasses[88].

Pollen development

-

Seven CLE genes including CLE9, CLE16, CLE17, CLE19, CLE41, CLE42, and CLE45 are highly expressed in Arabidopsis anthers, and are redundantly required for anthers' development[87].

In comparison to wild types, the cle19, cle19 cle42, and cle19 cle17 cle42 mutants, and transgenic plants carrying pCLE19: CLE19G6T (dominant negative CLE19, DN-CLE19), DN-CLE9, DN-CLE16, DN-CLE17, DN-CLE41, DN-CLE42, and DN-CLE45, all produce smaller anthers and fewer pollen grains. In contrast, overexpression of CLE19 (CLE19-OX) causes a more severe phenotype, with extremely small anthers, and predominantly defective pollen grains. Regarding the pollen wall, the DN-CLE19 shows excessive filling of the pollen wall material, while the CLE19-OX exhibits absent connections in the pollen wall network[87], suggesting the proper amount of CLE19 is required for normal anther and pollen development.

Transcriptomic and genetic analyses have revealed that CLE19 contributes to maintaining the pollen wall developmental homeostasis by negatively regulating the genetic transcriptional pathways that regulate the pollen wall precursor synthesis[72,87,89−91]. In CLE19-OX anther, the expression of tapetum key transcription factor gene ABORTED MICROSPORES (AMS), and pollen exine synthesis genes, such as ACYL-COA SYNTHETASE 5 (ACOS5) and CYP703B, are all reduced; whereas their expression in DN-CLE19 anther are all enhanced[87].

CLE19 binds to its receptor-coreceptor complex (PXL1/2-SERKs) on the tapetal cell plasma membrane, which induces the phosphorylation of PXL1, and activates intracellular signaling cascades that modulate the expression of downstream TFs like AMS, ultimately maintaining tapetum homeostasis, and ensuring normal pollen development[72] (Fig. 2c). This represents the first complete CLE ligand-receptor pair identified in pollen exine development.

Embryo development and seed dormancy

-

The CLE19 peptide gene is expressed in epidermal cells, hypocotyls, and the endosperm of the cotyledon primordium, suggesting its role in these developmental processes. Transgenic plants carrying DN-CLE19 confirmed that CLE19 is required for cotyledon formation by regulating nuclear differentiation and cytogenesis during embryonic development[79]. The embryo sac of many DN-CLE19 transgenic plants were smaller than those of the wild-type plants at the same developmental stage. The number of nuclei in the endosperm of DN-CLE19 plants was also reduced compared to the wild-type. In DN-CLE19 plants, the expression of the early endosperm development genes, such as MEDEA (MEA), FERTILIZATION INDEPENDENT SEED 2 (FIS2), and Agamous-like 62 (AGL62), was elevated in abnormal ovules. Endosperm development in DNA-CLE19 plants was delayed, accompanied by a delay in the expression of these endosperm developmental genes[79].

In addition, CLE8 has been implicated in zygotic embryo development, fertilization, and seed formation[92]. CLE8 mRNA is expressed in the embryo from the one-cell stage, through the globular and the triangular stages but disappears at the heart stage[92]. Seeds from cle8-1 mutants and CLE8 amiRNA plants exhibit morphological defects, including wrinkling, deformation, discoloration, and early miscarriage, indicating CLE8 plays a role in early seed development[92]. The loss of CLE8 function results in seed shrinkage, reduced endosperm proliferation, and premature differentiation, whereas its overexpression leads to elongated mature embryos, and enlarged seeds. CLE8 positively regulates WOX8 expression, forming a signaling module that promotes seed growth[92]. The WOX8 expression is increased in CLE8 overexpressed plants, indicating that CLE8 is sufficient to induce WOX8 expression. Moreover, wox8-1 mutant seeds are smaller than wild-type seeds, and WOX8 loss-of-function suppresses the enlarged seed phenotype in CLE8-OX plants, demonstrating that CLE8 functions upstream of WOX8 to promote seed growth[92].

-

The CLE45 peptide has been shown to prolong pollen tube growth in vitro. Two LRR-RLKs, SKM1 and SKM2, have been identified as candidate receptors for CLE45. At 22 °C, CLE45 is preferentially expressed in the stigma of the pistil, but expands to the transmitting tract when the temperature rises to 30 °C. Both SKM1 and SKM2 are expressed in pollen, and disruption of CLE45-SKM1/SKM2 signaling through RNAi, or a kinase-dead SKM1 version leads to reduced seed production at 30 °C (Fig. 3a). These results suggest that the CLE45-SKM1/SKM2 signaling pathway plays a protective role in maintaining pollen viability under short-term high-temperature stress, thereby contributing to stable seed production[49].

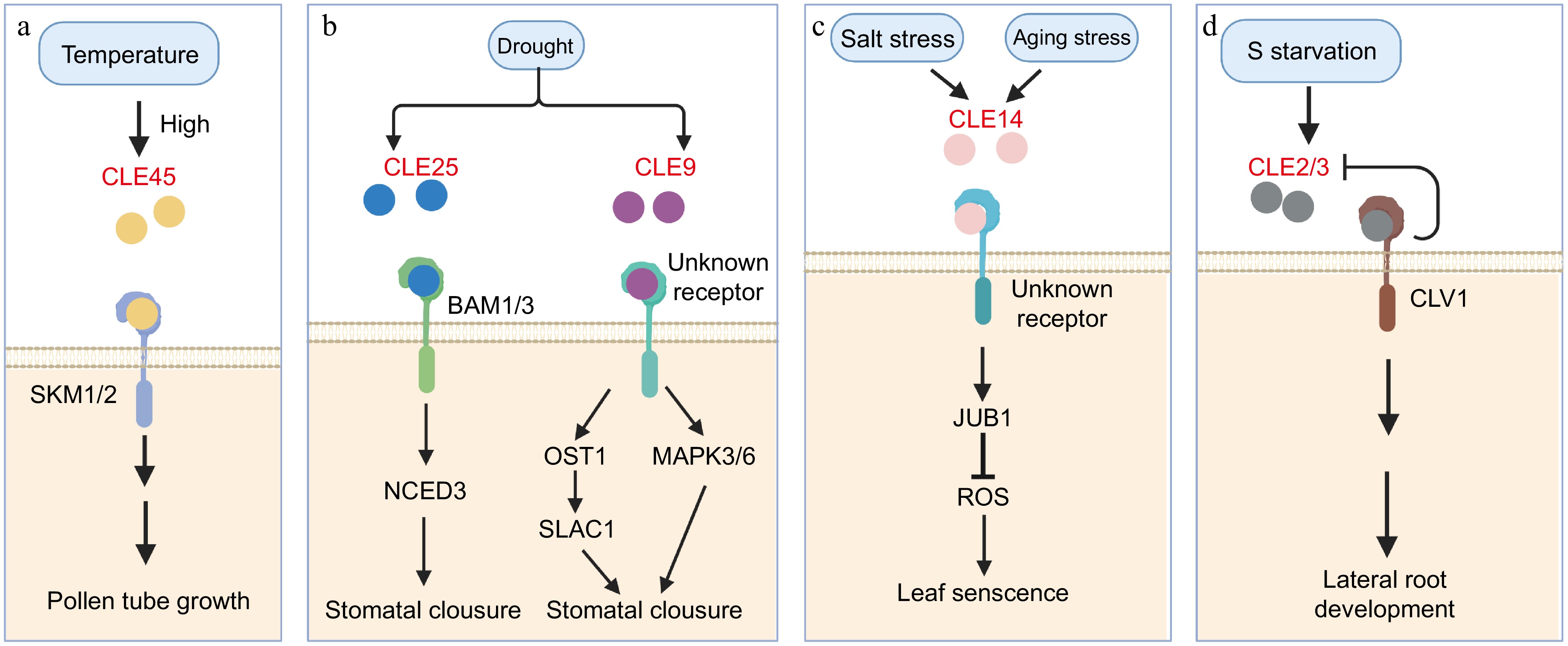

Figure 3.

CLE signaling pathway under different abiotic stresses. (a) The CLE45 peptide is perceived by the SKM1/2 receptors under high temperatures, regulating pollen tube growth and maintaining pollen viability. (b) The CLE25 peptide is perceived by BAM1/2 receptors, which regulate the NCED3 enzyme to modulate stomatal closure in response to drought stress. Additionally, CLE9 also responds to drought stress through unknown receptors, governing stomatal closure via distinct downstream signaling cascades. (c) CLE14 mediates responses to salt and aging stress by interacting with unknown receptors, regulating the transcription factor JUB1. JUB1 negatively regulates ROS levels, thereby influencing leaf senescence. (d) Sulfur (S) starvation induces CLE2/3 peptides, which are perceived by CLV1 to regulate lateral root development. In a feedback loop, CLV1 suppresses CLE2/3 expression to maintain root growth homeostasis.

Drought tolerance

-

CLE peptides play critical roles in drought tolerance by modulating stomatal movements[47,93−95]. CLE25, specifically, moves from roots to shoots during dehydration, where it promotes stomatal closure to reduce water loss[47,48]. Water availability is essential for plant growth, and drought stress severely impacts growth, development, and yield. Abscisic acid (ABA) is a key hormone in plant responses to drought stress, and plays a major role in regulating stomatal closure. The expression of NINECIS-EPOXYCAROTENOID DIOXYGENASE 3 (NCED3), an enzyme involved in ABA synthesis, serves as an indicator of ABA changes. The long-distance transport of CLE25 peptides increases NCED3 expression, which, in turn, enhances ABA accumulation in leaves. Moreover, drought treatment induces CLE25 expression in roots, activating ABA synthesis, and transport genes in vascular tissue, emphasizing the importance of vascular tissues in ABA production under drought stress[47,48].

GUS reporter assays revealed that CLE25 promoter activity occurs in lateral roots (LRs), root tips, leaf vascular tissue, and the procambium of primary roots. In situ hybridization further confirmed CLE25 expression in the root meristem and leaf vascular tissue. CRISPR-Cas9-mediated CLE25 mutants exhibited reduced sensitivity to drought stress, with suppressed drought-induced NCED3 expression. Additionally, genes involved in drought response, such as LATE EMBRYOGENESIS ABUNDANT (LEA) and RESPONSIVE TO DESICCATION 29B (RD29B, also known as LTI65), were not induced in cle25 mutants.

In bam1-5 bam3-3 double mutants, NCED3 expression was suppressed, and ABA accumulation in response to drought stress was absent. CLE25 treatment did not alter NCED3 gene expression in bam1-5 bam3-3 mutants but induced expression in bam2-5 bam3-3 double mutants[47], suggesting that CLE25 moves from the root to the leaf to modulate NCED3 expression through BAM1 and BAM3 receptors (Fig. 3b).

CLE9 induces stomatal closure in Arabidopsis through an ABA-dependent pathway involving OPEN STOMATA 1 (OST1), SLOW ANION CHANNEL-ASSOCIATED 1 (SLAC1), MAP KINASE 3/6 (MPK3/6), and reactive oxygen species (ROS)/nitric oxide (NO), thereby enhancing drought tolerance[96−98]. Cell-specific RNA transcriptomic analyses revealed that CLE9 is preferentially expressed in guard cells of Arabidopsis thaliana, indicating its potential role in stomata regulation. A GUS reporter assay driven by a CLE9 promoter confirmed this guard cell-specific expression. Exogenous CLE9 application triggered rapid stomatal closure, unlike with other CLE peptides such as CLE1, CLV3, CLE26, and CLE41. CLE9-overexpression (CLE9-OE) plants showed reduced stomatal aperture and improved drought resistance, whereas cle9-cr1 (CLE9-CRISPR-Cas9) mutants displayed impaired drought resilience. CLE9-induced stomatal reduction was abolished in ABA-deficient and ABA-insensitive mutants[98], highlighting a strict dependency on endogenous ABA signaling[96].

Downstream guard cell kinase OST1, and the anion channel SLAC1 are essential for CLE9-induced stomatal closure. In the ost1-3 and slac1-4 mutants, stomatal responses were abolished. Moreover, CLE9 treatment enhanced the phosphorylation of MPK3/6, and stomatal closure induced by CLE9 was impaired in mpk3-1 and mpk6-2 mutants, indicating that MPK3 and MPK6 are crucial components in the CLE9-mediated signaling pathway downstream of ABA (Fig. 3b). Additionally, CLE9 elevated H2O2 levels in guard cells, and the inhibition of NO signaling impaired CLE9-mediated stomatal closure, highlighting the role of ROS and NO as key messengers in this pathway[96].

Nutrient deficiency

-

Under environmental stress, plants may initiate early leaf senescence to complete their life cycle. This process is tightly regulated by both positive and negative regulators. CLE14 expression is induced by aging and salt stress and functions to delay leaf senescence by modulating ROS homeostasis[50]. CLE14 knockout mutants exhibit accelerated senescence under salt stress. In contrast, increased CLE14 expression or application of synthetic CLE14 peptides delays aging and ABA-induced leaf senescence. By reducing ROS levels, CLE14 signaling activates the transcription of JUNGBRUNNEN 1 (JUB1), a NAC transcription factor that negatively regulates aging (Fig. 3c)[50].

Root architecture is dynamically influenced by nutrient availability in the soil. While sulfur (S) uptake plays a critical role in plant growth and reproduction, the molecular mechanisms underlying root development in response to sulfur availability remain incompletely understood. A signaling module consisting of CLE peptides, and the CLV1 receptor kinase, regulates LR development in response to sulfur levels. Wild-type seedlings chronically deficient in sulfur show reduced LR density, which is restored by sulfate supplementation. In contrast, the LR growth rate in clv1 mutants is higher than in wild-type plants under chronic S-deficiency, and it normalizes upon sulfate supply[51]. This suggests that CLV1 signaling inhibits LR development under S-limiting conditions. Furthermore, the expression of CLE2 and CLE3 decreases in response to sulfur deficiency. These findings together demonstrate a finely tuned mechanism wherein CLE-CLV1 signaling coordinates LR development in response to sulfur availability (Fig. 3d)[51].

-

CLE peptides interact with major phytohormones, including auxin, cytokinin, brassinosteroids (BRs), and gibberellins (GAs), to regulate a wide range of developmental processes and stress responses. This intricate crosstalk enables plants to precisely control stem cell maintenance, vascular differentiation, root architecture, and response to environmental stresses. Recent studies have uncovered how CLE peptides modulate downstream signaling pathways and physiological outcomes by interacting with these key hormones. These interactions not only fine-tune developmental processes, but also enable plants to adapt to changing conditions, ensuring growth, survival, and reproductive success under varying environmental challenges.

Crosstalk between CLE peptides and cytokinin

-

Recent studies have revealed intricate crosstalk and interactions between CLE peptides and cytokinin, with both antagonistic and synergistic relationships in regulating plant development across various tissues and species[25,53,99,100].

In the SAM, cytokinin plays a key role in SAM maintenance by promoting the expression of the WUS gene[35]. Cytokinin directly induces WUS expression in the organizing center of the SAM, which helps stabilize the stem cell pool by inhibiting the expression of A-type ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATORS (A-ARRs)[37]. However, CLE peptides, especially CLV3, antagonize this process. CLV3 is secreted by the stem cells in the SAM, and inhibits WUS expression through its receptor complex[101,102]. This repression of WUS prevents excessive expansion of the stem cell pool, ensuring that the SAM does not grow unchecked. Thus, while cytokinin promotes stem cell identity and SAM function, CLE peptides act to limit stem cell proliferation, maintaining a delicate balance between stem cell maintenance and differentiation.

In the RAM, CLE peptides and cytokinin also exhibit antagonistic interactions regulating stem cell identity and differentiation[22,24,103,104]. In contrast to the SAM, where cytokinin promotes stem cell identity, cytokinin in the RAM induces differentiation, especially in the transition zone, where cells exit the meristematic zone and begin to elongate. Cytokinin signaling helps promote this differentiation by repressing auxin signaling through the induction of SHORT HYPOCOTYL 2 (SHY2), an AUX/IAA protein that inhibits auxin response[34]. This regulation of the transition zone identity is essential for proper root growth and patterning. CLE peptides, particularly CLE40, function to restrict the expression of WOX5, a key regulator of stem cell identity in the RAM[105]. It interacts with cytokinin signaling to inhibit root meristem activity, especially under nutrient-limited conditions. By signaling through CLV1 and ACR4 receptors, CLE40 promotes differentiation and suppresses proliferation by repressing WOX expression, which is necessary for maintaining the QC in the root, and promoting adaptive responses to environmental stresses[76,77]. This antagonistic interaction between CLE and cytokinin in the RAM ensures that the root maintains an appropriate balance of stem cells and differentiated cells, preventing both excessive proliferation, and premature differentiation.

Additionally, CLE peptides interact with cytokinin signaling in regulating vascular development, stomatal movement, and adapting to drought stress[41,52]. Cytokinin signaling inhibits the differentiation of protoxylem cells by preventing auxin transport in the procambium, maintaining the balance between the xylem and phloem, and ensuring proper vascular patterning[106]. On the other hand, CLE peptides, such as CLE10, also regulate vascular tissue development by inhibiting protoxylem formation. CLE10 peptide signaling works through the CLV2 receptor to suppress the expression of A-ARRs, including ARR5 and ARR6, which in turn allows for sustained cytokinin signaling, and the inhibition of protoxylem identity[37]. This cooperation between CLE and cytokinin signaling is critical for the proper patterning of vascular tissues, balancing xylem and phloem differentiation to ensure efficient water and nutrient transport in plants. Moreover, CLE9 and cytokinin signaling pathways both regulate stomatal activity[52]. CLE9 peptides primarily function to induce stomatal closure in response to drought, while cytokinin regulates stomatal formation and density[41]. The interaction between CLE and cytokinin in stomatal regulation highlights the complementary roles of these two signaling pathways in plant water regulation, ensuring that plants can adapt to changing environmental conditions.

Crosstalk between CLE peptides and auxin signaling

-

Auxin plays a central role in root and vascular development, influencing processes such as cell differentiation and tissue patterning. Recent studies highlight the intricate interactions between CLE peptides and auxin signaling and demonstrate how these pathways coordinate to regulate various developmental processes[56,107−110]. In root vascular tissue, CLE41 and CLE44 peptides interact with the PXY receptor-like kinase to influence procambium development[56,107]. This CLE-PXY signaling pathway works in close coordination with auxin gradients, which are critical for vascular cell fate determination, and differentiation[108]. Auxin induces CLE41 expression, and the resulting CLE-PXY feedback limits excessive auxin accumulation[108,109]. By controlling auxin levels, CLE peptides help maintain proper tissue differentiation in the root vascular system.

In the root tip, CLE peptides also regulate protophloem differentiation through auxin interactions. Specifically, CLE25 inhibits auxin signaling in developing protophloem cells, reducing the auxin response in these cells[110]. This localized suppression of auxin activity ensures spatially regulated phloem differentiation, and helps maintain root architecture, enabling proper differentiation and overall root function.

CLE and gibberellin signaling in growth regulation

-

Gibberellin signaling interacts with CLE signaling in the regulation of stem cell dynamics. In the SAM, GA signaling promotes cell proliferation and organ initiation. CLE peptides, especially CLV3, limit this proliferative effect by modulating the spatial expression of genes involved in GA biosynthesis and response. This regulation helps prevent excessive GA activity in the stem cell niche, maintaining a balance between growth-promoting and growth-limiting signals.

CLE-GA interactions also occur in other tissues, such as the vascular cambium. CLE41-PXY signaling in the cambium restricts GA response in differentiating xylem cells, preventing premature xylem expansion, and maintaining vascular tissue integrity. This CLE-GA antagonism illustrates how CLE peptides restrict hormone action in specific domains to shape plant tissue architecture.

-

In this review, we have explored the diverse roles of CLE peptides in plant development and stress responses, highlighting their interactions with major phytohormones, such as cytokinin, auxin, and gibberellins. CLE peptides play critical roles in regulating a wide range of processes, including stem cell maintenance, vascular differentiation, pollen development, stress responses, and nutrient adaptation. The crosstalk between CLE signaling and these hormones drives plant growth and development in a highly dynamic and context-dependent manner.

Current limitations in CLE signaling research

-

Despite the identification of functions of several CLE peptides in distinct processes, many other CLE peptides remain uncharacterized. One of the major challenges in studying CLE peptide function is the high degree of functional redundancy observed among CLE genes. Due to the large number of CLE family members and their structural similarity, many CLE peptides have redundant functions, making it difficult to distinguish the individual contributions of each peptide. In Arabidopsis, for example, single mutations often do not result in clear phenotypic changes, necessitating the use of higher-order mutants to uncover functional differences.

Additionally, the complexity of CLE receptor-ligand interactions adds another layer of difficulty. CLE peptides typically function through RLKs, which are highly redundant themselves, with many receptors involved in multiple signaling pathways. This receptor complexity makes it challenging to pinpoint which receptors are involved in responding to specific CLE peptides, and how these receptors interact with other signaling components, such as co-receptors and intracellular signaling molecules. The convergence of several CLE peptides on the same receptor, such as BAM1, which binds both CLE3 and CLE25, further complicates the understanding of receptor specificity and function.

Next-generation solutions for CLE signaling research

-

To overcome the challenge of CLE redundancy and limitations of global knockout models, tissue-specific and inducible CRISPR/Cas9 systems offer a promising solution. By controlling the expression of CRISPR/Cas9 constructs in specific tissues, or at specific developmental stages, researchers can investigate the roles of CLE peptides in tissue-specific contexts. This approach allows for more precise functional dissection and will help identify the unique contributions of CLE peptides to various developmental processes, such as meristem maintenance, vascular development, and stress responses. In addition, the CRISPR method that allows for the knockout of multiple genes simultaneously[111] can help address the functional redundancy issue in CLE peptides.

Additionally, the creation of DN-CLE constructs, achieved by targeted mutation of G6T residue and overexpression of point mutant CLE proteins, has partially addressed the issue of functional redundancy within the CLE family. The peptide produced with the Gly-to-Tyr substitution has lost the ability to activate downstream signaling. However, the use of DN-CLEs has been controversial. It was only in 2023 that Yu et al.[72] demonstrated that CLE19 with a G6T point mutation retains its ability to interact with the receptor PXL1, and promotes its interaction with the co-receptor SERKs. Crucially, however, this G6T mutation prevents CLE19 from activating the PXL1 receptors through phosphorylation, and initiating downstream signaling pathways[67]. This genetic and biochemical evidence supports the use of CLE19 with a G6T mutation as a functional dominant negative, thus validating the application of DN-CLEs in research.

Another next-generation tool that holds great potential for studying CLE peptides is peptidomics. This technology allows for the identification, quantification, and characterization of CLE peptides in various plant tissues. Combined with spatial transcriptomics, which provide insights into the spatial distribution of gene expression at a cellular level, peptidomics can reveal how CLE peptides are produced, transported, and act in different plant tissues. These techniques will be crucial in understanding the dynamics of CLE signaling, particularly in complex tissues like the root meristem and vascular bundles, where CLE peptides play critical roles.

Looking ahead, the integration of CLE peptide signaling with environmental responses, as well as the use of tissue-specific CRISPR systems and spatial transcriptomics, will provide deeper insights into the precise roles of CLE peptides across tissues and developmental stages. As our understanding of CLE signaling continues to evolve, these approaches hold the potential to drive innovations in crop breeding, improve stress resilience, and contribute to the development of more sustainable agricultural practices. Ultimately, the unraveling of CLE peptide signaling promises to offer new tools for enhancing crop productivity, quality, and environmental adaptability in the face of global challenges.

This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Science and Technology, People's Republic of China (2023YFA0913500), a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32270347 and 32470348) to Fang Chang, and a grant from the China Post-doctoral Science Foundation (2023M740705) to Ying Yu.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: draft manuscript preparation: Yu Y, Zhang S, Chang F; manuscript and figures revision: Yu Y, Zhang ST, Chang F; All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Ying Yu, Shiting Zhang

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Laboratory. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yu Y, Zhang S, Chang F. 2025. CLE peptides: key regulators of plant development and stress adaption. Seed Biology 4: e009 doi: 10.48130/seedbio-0025-0009

CLE peptides: key regulators of plant development and stress adaption

- Received: 10 February 2025

- Revised: 14 April 2025

- Accepted: 30 April 2025

- Published online: 06 June 2025

Abstract: CLAVATA3/EMBRYO SURROUNDING REGION (CLE) peptides are among the most well-studied families of plant peptide hormones, playing essential roles in regulating a wide range of biological processes, including plant growth, development, and stress adaptation. In this review, we explore the structural diversity of CLE peptides across species and provide a comprehensive summary of the biological functions and signaling mechanisms of CLE peptides. We first discuss their roles in plant development, including stem cell homeostasis, meristem activity, vascular patterning, and reproductive organ formation. We then explore how CLE peptides contribute to plant responses to environmental stresses such as nutrient deficiency, drought, and heat. Additionally, we summarize recent insights into the crosstalk between CLE signaling and classical phytohormonal pathways. Finally, we outline current challenges and propose future directions. By integrating knowledge from developmental and stress biology, this review aims to promote a deeper understanding of CLE signaling in dynamic plant environments, leveraging this knowledge to enhance crop resilience and productivity in changing climates.