-

Seed germination is a critical transition point from quiescence to growth and a key agronomic trait determining the field emergence rate, crop stand uniformity, and yield. Rice is a fundamental dietary component for nearly 50% of the human population, holding substantial scientific importance and practical applications for deciphering the governing principles underlying seed germination traits. This is particularly important with the rapid development of direct-seeding rice cultivation, mechanization, and simplified farming techniques, which require faster and more uniform seed germination[1]. However, cultivated rice gradually lost the deep dormancy characteristic of wild rice during long-term domestication, leading to pre-harvest sprouting (PHS), which is a major constraint for rice yield and quality. Currently, PHS is one of the most severe threats to grain production worldwide. In southern China's rice-growing regions, PHS causes annual losses ranging from 6%–20%, with severe years exceeding losses of 30%. In these regions, which are affected by wet weather conditions during the harvesting period, PHS reduces the planting acreage for standard rice varieties by approximately 6%, and premium hybrid strains may experience losses reaching one-fifth of the total cultivated land[2]. Consequently, deciphering the molecular mechanisms controlling seed dormancy and sprouting processes has become imperative for the cultivation of enhanced rice cultivars, especially those exhibiting PHS.

Seed dormancy is the inability of viable seeds to germinate for a certain period, even under suitable environmental conditions. As seed dormancy is influenced by both genetic and environmental factors; it can prevent seeds from germinating under short-term favorable conditions in adverse seasons. The evaluation of dormancy is often expressed as the seed germination rate under certain conditions. Seed dormancy and germination are two interrelated independent events with a series of different physiological and biochemical processes[3,4]. Germination is the process by which a viable seed without dormancy or released dormancy changes from a relatively static state to a physiologically active state after water absorption, causing embryo growth. The radicle breaking through the seed coat is generally believed to be a sign of germination. Seed germination is the initial step in the plant life cycle, especially that of annual and biennial plants, and is the premise of realizing the function of seed chips[5].

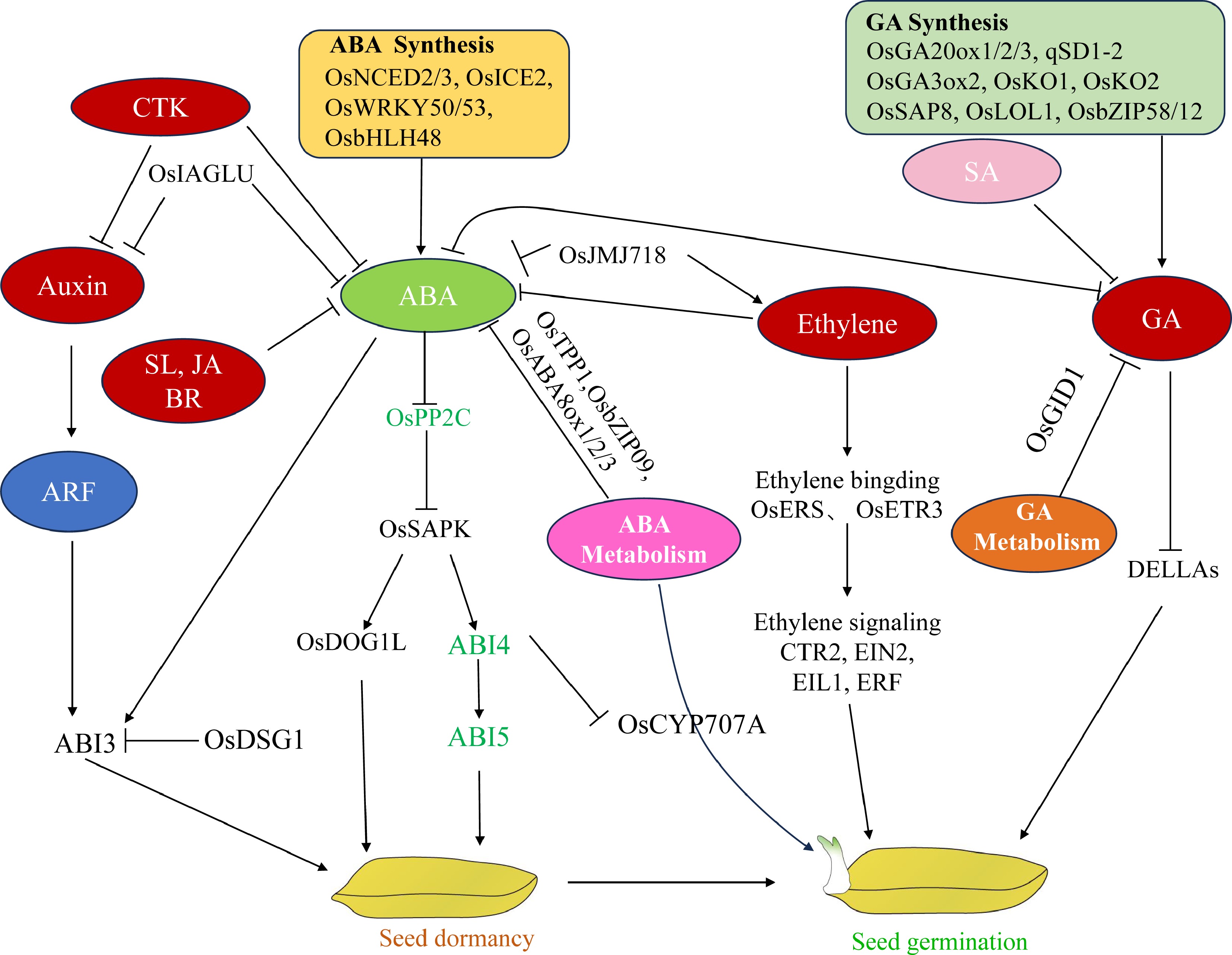

Through the integration of endogenous hormonal signals with external environmental cues, dormancy ensures the optimal timing for seed germination. Among the hormones, the intricate equilibrium between abscisic acid (ABA) and gibberellin (GA) constitutes a fundamental biological mechanism controlling seed dormancy release and subsequent sprouting initiation. ABA triggers and sustains seed dormancy by suppressing sprouting, and GA stimulates germination and offsets the inhibitory effects caused by ABA[6]. Exogenous ABA suppresses seed germination, and mutants defective in ABA biosynthesis or signaling have increased germination rates. ABA-insensitive factors (ABI1, ABI2, ABI3, ABI4, and ABI5) negatively regulate seed germination[7]. However, exogenous GA promotes germination. GA-deficient mutants, such as ga1 and ga2, have delayed or defective germination[8]. DELLA proteins, which comprise GA response inhibitor (RGA), gibberellin acid non-responsive (GAI), and RGA-similar 2 (RGL2) proteins, function as inhibitory elements in germination. These molecular regulators constitute fundamental aspects of GA-mediated signal transduction pathways. The protein family operates via suppression mechanisms that modulate plant developmental responses to hormonal stimuli[9]. Although ABA and GA remain central, cytokinin (CK), ethylene (ETH), and indole acetic acid (IAA) significantly influence dormancy termination and sprouting initiation. Emerging research has revealed the involvement of other phytohormones, such as brassinosteroids (BRs), strigolactones (SLs), jasmonates (JAs), and salicylates (SAs) in seed quiescence and activation processes. These compounds form an intricate signaling framework in which the ABA/GA balance serves as the primary regulatory hub, with extensive hormonal interactions occurring across multiple pathways. Coordination between these diverse plant growth regulators creates a sophisticated control system governing physiological transitions in the seed.

This review examines the distinct regulatory elements governing seed dormancy and sprouting processes in rice, presenting a comprehensive analysis of metabolic control systems and interplay dynamics among key phytohormones, including ABA, GA, and ETH. Incorporating recent scientific developments, the discussion highlights prospective research pathways designed to advance our understanding of the hormonal regulation mechanisms affecting seed dormancy and germination at the molecular level, and details genetic improvement approaches for boosting rice crop tolerance to environmental stressors.

-

ABA, a sesquiterpenoid carboxylic acid composed of 15 carbon atoms derived from isoprene units, predominantly accumulates in plant organs and tissues undergoing abscission or dormancy. It serves as a critical regulator for multiple biological functions.

ABA biosynthesis, metabolism, and signal transduction

-

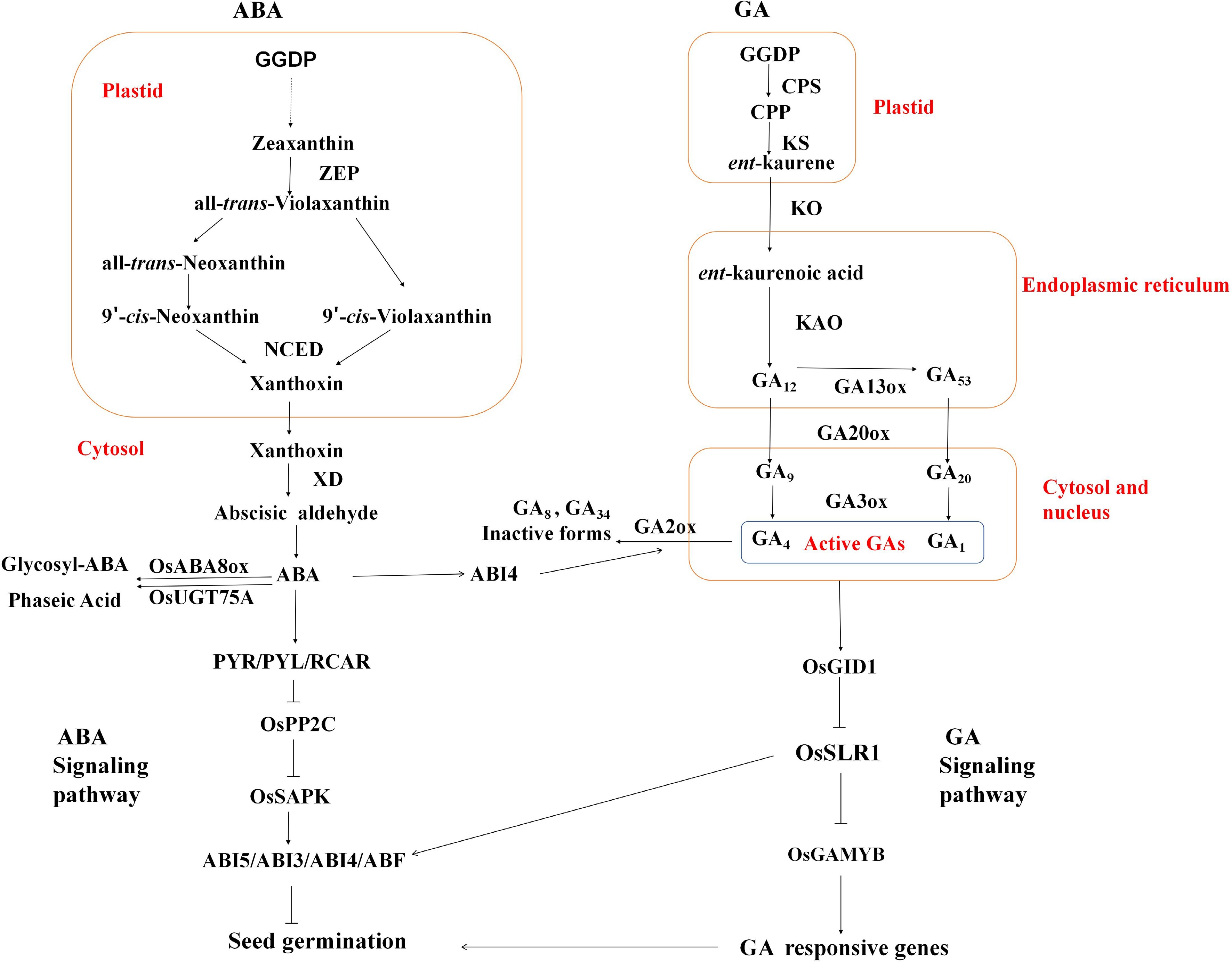

ABA production begins in plastids and is completed in the cytoplasmic compartment, and its concentration is regulated through specialized biochemical routes. For land-dwelling plants, the C40 compound 9'-cis-neoxanthin functions as the principal starting material for ABA generation and is synthesized from isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) through the plastid-resident methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) metabolic sequence[10]. The enzymatic breakdown of 9'-cis-neoxanthin through 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED) activity, which results in xanthoxin formation, is the primary bottleneck for ABA production. This catalytic conversion establishes the pivotal regulatory phase governing the efficiency of ABA synthesis. In rice, endogenous ABA levels are positively correlated with NCED transcript abundance, and OsNCED expression levels are commonly used as biomarkers for determining the ABA content. Phenotypes promoting germination or reducing dormancy are typically correlated with downregulated OsNCED expression (except for OsNCED1)[11]. ABA catabolism occurs through hydroxylation and glucosylation pathways. 8'-Hydroxylation constitutes a critical step in ABA degradation, which is catalyzed by cytochrome P450 monooxygenases encoded by the CYP707A gene family and converts ABA into phaseic acid (PA). Subsequently, PA undergoes two parallel metabolic routes: reduction by PA reductase and ABH2 to dihydrophaseic acid (DPA) and glucosylation by UDP-glucosyltransferases (UGTs) to form DPA-4-O-β-D-glucoside[12]. ABA glucosyl ester (ABA-GE), the primary ABA derivative, serves as both a reservoir and a mobile transport version of ABA. Enzymatic glucosyltransferases facilitate the attachment of glucose to ABA's carboxyl moiety, and β-glucosidase-triggered cleavage of ABA-GE liberates active ABA, regulating tissue-specific ABA levels.

The fundamental ABA signaling system incorporates pyrabactin resistance 1 and its homologs/regulatory elements of ABA receptors (PYR/PYL/RCAR), class A PP2C phosphatases[13], category III SnRK2 kinases involved in sucrose metabolism, and transcription regulators that bind to ABA-responsive motifs (ABRE-binding proteins/AREBs) (Fig. 1)[6]. When ABA levels increase, OsPYL/RCAR proteins, such as OsPYL5, undergo structural modifications that enable them to interact with and suppress group A PP2C phosphatases, such as OsPP2C30/51. This inhibition liberates subclass III SnRK2 kinases, including SAPK2/10, from suppression. The liberated SnRK2 enzymes then phosphorylate ABF/bZIP transcriptional regulators (e.g., OsABF2 and OsbZIP10), triggering the expression of ABA-dependent target genes[14].

Figure 1.

The biosynthesis, metabolism, and signaling pathways of abscisic acid (ABA) and gibberellin (GA). GGDP: Geranylgeranyl diphosphate; ZEP: Zeaxanthin epoxidase; NCED: 9-cis-Epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase; XD: Xanthoxin dehydrogenase; CPS: ent-Copalyl diphosphate synthase; KS: ent-Kaurene synthase; CPP: ent-Copalyl diphosphate; KO: ent-Kaurene oxidase; KAO: ent-Kaurenoic acid oxidase.

Regulation of rice seed dormancy and germination by ABA

-

The process by which ABA controls seed dormancy involves intricate genetic interactions (Table 1). There are five rice ABA production pathway genes in the NCED family (OsNCED1−5)[15]. Transcription factor OsbHLH048 modulates ABA biosynthesis by specifically controlling OsNCED2 expression levels during rice seed germination. OsNCED3 overexpression significantly increases the seed ABA content and enhances dormancy, whereas knockout mutants exhibit precocious germination and reduced dormancy[16]. The functions of other OsNCED family members vary due to tissue-specific expression or functional redundancy, which requires further investigation[17]. Knockout of the OsNCED3 gene decreases ABA accumulation in embryos, reducing seed dormancy and consequently inducing PHS. Haplotype analysis revealed that the Hap1 allele of OsNCED3 is associated with higher PHS susceptibility, and Hap2 and Hap7 are correlated with lower PHS rates[16]. Seed Dormancy 6 (SD6), which encodes a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor, is a quantitative trait locus (QTL) regulating seed dormancy in indica rice and underlies the natural variation in seed dormancy. SD6 modulates seed dormancy in a temperature-dependent manner by directly regulating the ABA catabolic gene ABA8ox3, thus controlling ABA homeostasis and dormancy[2].

Table 1. Genes regulating rice seed germination and dormancy through abscisic acid (ABA) metabolism, transport, and signal transduction.

Genes Gene accession number Signaling pathway Ref. OsNCED3 LOC_Os03g44380 Mutant seeds show a decreased ABA content and PHS. [16] OsbZIP10/ABI5/ OREB1 LOC_Os01g64000 Induced by ABA and high salinity, it negatively regulates rice seed germination. [18] OsDOG1L-3 LOC_Os01g20030 ABA positively regulates OsDOG1L-3 expression, and OsDOG1L-3 positively regulates the ABA pathway in a feedback manner, enhancing seed dormancy. [19] OsTRAB1 LOC_Os08g36790 Regulates ABA-induced transcriptional responses and plays an important role in regulating embryo maturation and dormancy. [18] SAPK2 LOC_Os07g42940 Mutants are insensitive to ABA during germination and post-germination stages. [20] OsFbx352 LOC_Os10g03850 OsFbx352 plays a role in the regulation of glucose-induced seed germination inhibition by targeting ABA metabolism. [21] OsWRKY29 LOC_Os07g02060 OsWRKY29 is a negative regulator of rice dormancy. The presence of ABA inhibits the expression of OsWRKY29, increasing the transcription of OsVP1 and OsABF1 and ultimately increasing rice seed dormancy. [22] OsWRKY50 LOC_Os11g02540 OsWRKY50 negatively regulates ABA-dependent seed germination by directly inhibiting the expression of the rice ABA biosynthesis gene OsNCED5. [23] OsWRKY53 LOC_Os05g272730 OsWRKY53 directly binds to the promoters of ABA catabolic genes OsABA8ox1 and OsABA8ox, inhibiting their expression, which results in ABA accumulation and further inhibits rice seed germination. [22] OsGAMYB LOC_Os01g0812000 MYBS1 and MYBGA are two MYB transcription factors. GA enhances the co-nuclear transport of MYBGA and MYBS1 and forms a stable binary MYB-DNA complex that activates α-amylase gene expression. Transcription factor 14 and OsGAmyb are downstream target genes of miR319. miR319 negatively regulates rice tillering and yield per plant by targeting OsTCP21 and OsGAmyb. [24] OsbHLH048 LOC_Os02g52190 bHLH transcription factors SD6 and ICE2 indirectly act on the ABA synthesis gene NCED2 through OsbHLH048 to regulate the ABA content in seeds and antagonistically regulate rice seed dormancy. [2] OsTPP1 LOC_Os02g44230 OsTPP1 controls rice seed germination through crosstalk with the ABA catabolic pathway. [25] Sdr4 LOC_Os07g39700 Positively regulated by OsVP1, mutants are insensitive to ABA. [26] SD6 LOC_Os06g06900 Negatively regulates dormancy and targets ABA8ox3 to indirectly regulate NCED2. [19] ICE2 LOC_Os01g70310 Positively regulates dormancy and antagonistically regulates ABA metabolism and synthesis with SD6. [2] ABA8ox3 LOC_Os09g28390 An ABA catabolic gene directly regulated by SD6/ICE2. [2] NCED2 LOC_Os12g24800 An ABA synthesis gene indirectly regulated by SD6/ICE2 through OsbHLH048. [2] DG1 LOC_Os03g12790 A MATE transporter that regulates the long-distance transport of ABA from leaves to caryopses and responds to temperature changes. [27] OsSAE1 LOC_Os06g43220 Directly binds to the promoter of the key ABA signaling pathway gene OsABI5, inhibiting its expression and promoting rice seed germination. [28] OsG LOC_Os03g01014 G affects seed dormancy through the interaction with NCED3 and psy and then regulates ABA synthesis [29] Similarly, the reduced expression of ABA catabolic genes OsABA8ox1, OsABA8ox2, and OsABA8ox3 inhibits seed germination. OsABA8ox1 and OsABA8ox2 expression in rice is negatively regulated by OsWRKY53, and overexpression lines exhibit delayed germination due to ABA accumulation[30]. OsNAC3 increases rice seed germination through ABA-mediated regulation of OsABA8ox1 expression, functioning within the ABA signaling cascade[2].

In rice, 13 genes homologous to AtPYL have been identified. Genetic modification experiments revealed that elevated expression of OsPYL3, OsPYL5, and OsPYL9 induces exaggerated ABA responses during seedling emergence. Biochemical analysis has confirmed the physical association between OsPYL5 and OsPP2C30[18]. Simultaneously mutating genes encoding ABA receptor class pyrrolic resistance 1 (PYL1), PYL4, and PYL6 promotes rice growth and increases grain yield. Among the single pyl mutants, pyl1 and pyl12 have visible seed dormancy defects. Rice class I (pyl1–pyl6 and pyl12) genes play a more important role in seed dormancy than class II (pyl7–pyl11 and pyl13) genes. Pyl1/4/6 have almost reached normal seed dormancy under natural rice field conditions[31]. The OsABIL2 gene, which is classified under PP2C, functions as an inhibitory component in ABA-mediated pathways, with its elevated expression resulting in PHS in rice. Representing the most extensive phosphatase group in plant systems, PP2C enzymes serve pivotal functions in ABA transduction mechanisms. Research has demonstrated that OsPP2C51 forms molecular associations with OsPYL/RCAR5 in response to ABA, subsequently removing phosphate groups from OsbZIP10 to facilitate grain sprouting via the OsPYL/RCAR-OsPP2C-bZIP transduction cascade (Fig. 2)[32].

In the 14-3-3 family, a 4-bp insertion–deletion (InDel) variant, OsGF14h, modulates rice germination rates under optimal temperature conditions. The GF14h protein establishes a transcriptional control network in conjunction with the bZIP factor OREB1 and the florigen-related protein MFT2, modulating the efficiency of rice seed germination via the regulation of ABA-responsive genetic elements. Mutant variants of GF14h intensify ABA-mediated signaling pathways but decrease germination performance[33].

There are 10 members of the SnRK2 family in rice, which are named SAPK1–SAPK10. Among them, SAPK2 primarily mediates ABA signaling due to its physical interactions with OsPP2C30 and OsPP2C51. Enhanced SAPK10 expression postpones seed sprouting and increases sensitivity to ABA. In rice, OsPYL/RCAR5 overexpression delays germination via interactions with OsPP2C30 and OsPP2C51, leading to SAPK2 phosphorylation and activation. Activated SAPK2 interacts with ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE5 (OsABI5), inducing the expression of ABA signaling pathway genes. OsUBC12 primarily catalyzes K48-linked polyubiquitination and recruits OsSnRK1.1, promoting its degradation. As a key downstream regulator, OsSnRK1.1 negatively regulates low-temperature germination by upregulating ABA signaling[34].

ABI5 serves as a fundamental regulator in the ABA-mediated signaling cascade, influencing seed sprouting. Although ABI5 does not impact dormancy states, it actively suppresses the germination process (Fig. 2). Research in rice has revealed multiple ABA-responsive ABI5-related transcription factors, including TRAB1 and OsbZIP10. OsABI5 is phosphorylated by SAPK2 or dephosphorylated by OsPP2C51, thus bypassing SAPK2[35]. Du et al.[36] identified rice mutant phs8, which exhibits PHS phenotype accompanied by sugary endosperm. The mutation of phs8 results in plant glycogen decomposition and sugar accumulation in the endosperm. With the increase in the sugar content, the expression of OsABI3 and OsABI5 and the sensitivity to ABA decreased in the phs8 mutant[36]. Guo et al. cloned seed dormancy 3.1 (sdr3.1), which negatively regulates seed dormancy by inhibiting the transcriptional activity of ABIS, under a major QTL, and revealed that two key amino acids of sdr3.1 contribute to the difference in seed dormancy between indica and japonica[37].

In rice plants, bZIP transcriptional regulators have been widely documented to control seed dormancy and sprouting processes. The OsbZIP09 protein accelerates seed germination through two mechanisms, boosting ABA breakdown and weakening ABA signal transduction pathways, reducing ABA-induced germination suppression. In contrast, OsMFT2 forms molecular complexes with OsbZIP23/66/72 proteins, amplifying ABA signaling cascades, which inhibit seed germination activity. OsbZIP23 and OsbZIP46 are activated via SnRK2-mediated phosphorylation (Fig. 2)[38]. CCT30, which has been identified as a novel regulator promoting PHS in rice, reduces seed dormancy by enhancing sugar signaling and suppressing ABA biosynthesis and signaling pathways. Further studies have shown that CCT30 interacts with transcription factor OsbZIP37, coordinately regulating downstream genes, which negatively modulates rice seed dormancy[39].

WRKY transcription regulators significantly influence ABA-mediated signaling cascades. Functioning as an ABA signaling suppressor, OsWRKY29 actively suppresses rice seed dormancy through the direct transcriptional repression of key ABA-responsive elements, specifically OsABF1 and OsVP1, demonstrating the critical involvement of WRKY proteins in hormonal response modulation[40]. Red pericarp rice enhances the ABA signaling pathway through the synergistic action of Rc (a bHLH transcription factor) and OsVP1, thereby improving the seed dormancy intensity and PHS resistance[40]. OsVP1 coactivates TRAB1, regulating SDR4 via ABREs. Both osvp1-1 and sdr4 mutants exhibit ABA-insensitive germination, placing them downstream of ABA signaling. OsVP1-mediated SDR4 regulation and altered OsPYL1/2 expression confirm their roles in dormancy control, with SDR4 acting as a key dormancy determinant[41,42].

Oryza sativa delayed seed germination 1 (OsDSG1) produces a RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase that inhibits ABI3 activity. Plants with osdsg1 mutations have shown postponed sprouting and increased expression of ABA-related genes, including OsABI3 and OsABI5. Consequently, the breakdown of OsABI3 by OsDSG1 is essential for rice seed germination, interrupting ABA signal transmission through the OsABI3–OsABI5 regulatory axis. This process enables the re-expression of genes that are normally suppressed by ABA, particularly those that produce hydrolytic enzymes, thereby facilitating successful seed germination[43]. OsDOG1-like gene (OsDOG1L-3) overexpression significantly enhances seed dormancy. OsbZIP75 and OsbZIP78 directly bind to the promoters of OsDOG1L-3, inducing their expression[19].

Functional investigations have demonstrated that stay-green G gene affected seed dormancy through interactions with NCED3 and PSY, thus modulating ABA synthesis. Wang et al. found that the wild rice gene OsG (LOC_Os03g01014) delayed germination compared to ZH11, and the introduction of OsG into another cultivated rice variety, HJ19, also resulted in delayed germination. Two LOC_Os03g01014 alleles of O. rufipogon (IRGC 105491, OsG) and cultivated rice ZH11 (Osg) were overexpressed, and comparisons showed that OsG plants had a stronger dormant phenotype[29].

-

GA represents a crucial category of tetracyclic diterpenoid phytohormones that control numerous physiological activities during plant growth cycles. These biochemical regulators influence multiple development stages, such as seed sprouting, vertical stem expansion, foliar growth stimulation, floral initiation, pollen grain maturation, and reproductive tissue formation. Embryonic tissues have an intrinsic biosynthetic capacity for GA production, with the developing embryo acting as the primary site of hormone generation. GA in the seed is in both free and bound states[44]. Bound GA does not result in physiological activity and is a storage and transportation form, whereas free GA has physiological activity. When seeds germinate, the physiological activity of GA promotes cell elongation and cell division, regulates seed dormancy, and promotes seed development[45]. Among the more than 130 GAs discovered thus far, those with biological activity include GA1, GA3, GA4, and GA7.

GA synthesis, metabolism, and signal transduction

-

Studies have shown that GA production is initiated by geranyl diphosphate (GGDP), which is the primary building block. This precursor undergoes sequential transformations facilitated by specific enzymes: ent-copalyl diphosphate synthase, ent-kaurene synthase, kaurene oxidase, and kaurenoic acid oxidase. Subsequent modifications involve GA20 oxidase and GA-3 oxidase, yielding physiologically active GA molecules. The metabolic pathway concludes with GA-2 oxidase-mediated deactivation. These catalytic proteins represent crucial components of both GA biosynthesis and catabolism (Fig. 1).

GA inactivation occurs through several mechanisms in plants, including inactivation by GA 2-oxidase, catalysis by methyltransferase to form GA methyl ester, conversion by GA 16,17-oxidase to 16α, 17 epoxides, and binding with glucose to form GA glucose ester. GA2ox is a type of 2ODD that can be divided into two groups based on its substrate: one group acts on C19-GA, including bioactive compounds and their direct non-3β-hydroxylated precursors; the other group acts on C20-GA. In rice, there are 7 C19-GA2ox genes (OsGA2ox1, OsGA2ox2, OsGA2ox3, OsGA2ox4, OsGA2ox7, OsGA2ox8, OsGA2ox10) and three C20-GA2ox genes (OsGA2ox5, OsGA2ox6, OsGA2ox9)[46]. Bioactive GAs undergo metabolic deactivation through the enzymatic action of cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (CYP714D1). In rice, in vitro experiments have shown that this enzyme is produced by the locus ELONGATED UPPERMOST INTERNODE (EUI) and catalyzes the conversion of GA precursors into 16α,17-epoxy GA derivatives. The CYP714D1 enzyme has substrate specificity for GA12, GA9, and GA4 molecules and exhibits significantly reduced catalytic efficiency toward 13-hydroxylated GA compounds. Artificially upregulating EUI expression in rice cultivars results in severe growth retardation phenotypes accompanied by diminished GA4 accumulation in apical stem segments, confirming that epoxidation is a biochemical pathway for GA deactivation.

Under continuously rainy weather, dry OsGA2ox9-cas9 grains showed early embryo germination, and the spikes of rice plants germinated. OsGA2ox9-OE seed dormancy increased and was restored by exogenous GA3, confirming that OsGA2ox9 regulates seed dormancy by affecting GA metabolism. Seed-specific expression of OsGA2ox9 eliminates the adverse effects of OsGA2ox9 overexpression in vegetative tissues, and the generation of beneficial alleles through single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) replacement can improve PHS resistance[47]. Sd1, a Green Revolution gene encoding gibberellin 20 oxidase 2 (GA20ox2), is widely used in modern rice breeding. As a transcriptional repressor of sd1/OsGA20ox2, zinc finger protein ZFP207 plays the role of fine-tuning GA biosynthesis in rice growth and development[48].

The GA signaling cascade comprises several key elements: the GID1 GA receptor, inhibitory DELLA proteins[49], and the activating F-box component GID2[50]. The initial identification of the GID1 receptor occurred during positional cloning studies of the extreme dwarf rice mutant gid1. The functional equivalent of DELLA proteins is known as SLR1 (SLENDER RICE 1) in rice, and successful rice seed germination requires its proteolytic breakdown.

The molecular mechanism of GA signaling in rice seed germination occurs through distinct regulatory phases. Under GA-deficient conditions, the SLR1 protein forms inhibitory complexes with GAMYB, suppressing α-amylase production. GA triggers the assembly of a tripartite GA-GID1-SLR1 structure, which undergoes targeted proteolysis through SCFGID2 ubiquitination machinery. Liberated GA MYB transcription factors recognize and bind GARE motifs within α-amylase gene regulatory regions, initiating starch breakdown in the endosperm.

OsSAP8 establishes protein–protein interactions with both OsLOL1 and OsbZIP58, diminishing the affinity of OsbZIP58 for the KO2 gene promoter[51]. This regulatory shift enhances GA biosynthesis, stimulating amylase production and germination processes (Table 2). The germination modulator OsGD1 exerts control by binding to the OsLFL1 promoter, downregulating GA2ox3 and upregulating GA20ox1, OsGA20ox2, and OsGA3ox2, which collectively affect germination kinetics.

Table 2. Genes regulating rice seed germination and dormancy through gibberellin (GA) metabolism, transport, and signal transduction.

Genes Gene accession number Signaling pathway Ref. IPA1 LOC_Os08g39890 IPA1 mediates part of the effect of miR156 on seed dormancy by directly regulating many genes in the GA pathway. [52] SAPK10 LOC_Os03g41460 SAPK10 increases the endogenous GA level and inhibits seed germination. [53] OsbZIP12 LOC_Os01g64730 OsbZIP12 inhibits GA synthesis and regulates rice seed germination. [53] WRKY72 LOC_Os11g29870 WRKY72 directly targets LRK1, activates its transcription, and inhibits OsKO2 (ent-kaurene oxidase), thereby reducing the endogenous GA level and inhibiting rice seed germination. [54] OsGA20ox2 LOC_Os01g66100 OsGA20ox2 is expressed in developing seeds, including endosperm tissues, and regulates rice seed germination through the GA signaling pathway. [55] OsLOL1 LOC_Os08g06280 OsLOL1 increases the GA level, affects the aleurone layer programmed cell death (PCD) process, and promotes rice seed germination. [56] OsSLR1 LOC_Os03g49990 GA relieves the inhibition of OsUDT1/OsTDR by OsSLR1, thereby positively regulating rice fertility. [22] OsKO1 LOC_Os06g37330 The mutation of OsKO1 reduces enzyme activity, decreasing the contents of GA1, GA3, and GA53 and delaying seed germination. [57] qSD1-2 LOC_Os01g66100 Involved in GA biosynthesis. [55] OsFIE1 LOC_Os08g04290 Osfie1 inhibits seed germination and aleurone layer thickening by inhibiting GA accumulation in rice endosperm [58] The GA signal transduction process relieves the inhibition caused by DELLA proteins on downstream transcription factors through the GA-GID1 complex, activating the expression of GA-responsive genes and thus regulating seed dormancy and germination[9]. After a GA signal is generated, it is immediately transmitted to the DELLA protein via the receptor system and then transmitted downstream. GA signals affect the stability of DELLA proteins and induce their degradation. The DELLA domain plays a crucial role in this GA-induced destabilization. DELLA proteins are nuclear transcription regulators that inhibit GA signal transduction and restrict plant growth. Based on their roles in GA signal transduction, genes associated with GA signal transduction are classified as positively or negatively acting components. Negative regulators in the GA signal transduction pathway act as molecular switches in the regulatory mechanism. Second messengers of intracellular signal transduction, such as Ca2+ and cGMP, are positive regulators of GA signal transduction. NO negatively regulates the GA signaling pathway. In rice, the nuclear protein OsWOX3A exerts negative feedback regulation on the plant GA biosynthesis pathway[59].

Effects of GA on rice seed dormancy and germination

-

Throughout the seed germination process, GAs serve crucial functions in stimulating sprouting, breaking dormancy, and opposing ABA's inhibitory actions. These biological impacts rely on GA metabolic pathways and signaling mechanisms. Mutant strains lacking endogenous GA production are incapable of germination unless supplemented with external GA sources. In contrast, chemical compounds blocking GA synthesis pathways, including paclobutrazol and tetcyclacis, inhibit the germination capacity of normal seeds. Consequently, the initiation of GA production during seed hydration is a vital requirement for successful germination (Fig. 2).

mir-156-IPA1 is a novel regulatory factor involved in rice growth and defense. The mir156 mutation upregulates IPA1, inhibiting the GA pathway and enhancing rice seed dormancy. SnRK2 kinase physically binds and phosphorylates ABF, especially bZIP, transmitting ABA signals in plants[60], increasing endogenous GA levels, and inhibiting seed germination. The SnRK2 kinase SAPK10, which relies on ABA, it reduces its DNA binding ability to AOS1 by phosphorylating the Thr129 site of WRKY72, thus alleviating its inhibition of AOS1 expression and JA synthesis. Enhanced OsWRKY72 expression disrupts ABA signal transduction and auxin mobilization mechanisms. Transcription factor WRKY72 specifically binds to the LRK1 promoter region, stimulating its transcriptional activity and simultaneously suppressing the native root enzyme OsKO2, which is responsible for kaempferol oxidation. This regulatory cascade results in diminished endogenous GA concentrations, impeding the germination process in rice seeds (Fig. 2).

The OsKO1 gene plays a crucial role in early plant development, particularly during seed sprouting and young plant phases. When this genetic component is absent or impaired, GA levels significantly decrease, resulting in postponed germination and partially stunted growth. Furthermore, OsLOL1 promotes seed germination by upregulating OsKO2, indicating the important role of OsKO1 in rice seed germination[56]. The metabolic conversion of physiologically active GAs primarily occurs through the enzymatic actions of GA20ox and GA3ox, whereas their degradation is mediated by GA2ox[57]. Variations in endogenous bioactive GA concentrations and rice seed germination rates are correlated with the transcriptional activity of the genes that produce these catalytic enzymes. Embryonic OsGA3ox2 expression triggers α-amylase production during rice seed sprouting, whereas GA2ox transcription is suppressed throughout water absorption in nondormant seeds. The genetic region qSD1-2 harbors OsGA20ox2, a key GA biosynthesis gene. Disruptions in the functionality of this gene decrease GA accumulation in seeds and prolong dormancy[61]. OsGA2ox3 has been identified as a probable genetic determinant that influences the timing of germination[49]. In germination-impaired gd1 mutants, the transcriptional suppression of GA-producing genes (OsGA20ox1, OsGA20ox2, and OsGA3ox2) coincides with increased OsGA2ox3 expression, leading to depleted GA4 levels and arrested germination. Transcription factor OsbZIP12 modulates the rice stature and germination capacity through the negative regulation of GA biosynthesis pathways (Fig. 2).

ABA and GA coordinately regulate rice seed germination

-

The control of seed dormancy vs germination through the interactions of ABA and GA fundamentally depends on their proportional equilibrium (ABA/GA); this ratio determines whether seeds remain dormant or initiate sprouting. Elevated ABA/GA proportions are correlated with suppressed germination, and diminished ratios facilitate the germination process. Seed dormancy states progress across three primary categories: absence of dormancy, intermediate dormancy, and profound dormancy. For example, studies on the changes in the ABA and GA contents during rice seed development and imbibition have shown that non-dormant seeds have a low ABA content during development. Deep-dormant seeds exhibit the highest ABA content, with the ABA/GA ratio reaching its peak during mid-development, and non-dormant seeds have the lowest ABA content. Tiller enhancer (TE) encodes an activator of the APC/CTE E3 ubiquitin ligase complex that degrades the rice ABA receptor OsPYL. TE counteracts ABA signaling by facilitating the breakdown of PYL/PYR/RCAR receptors[62]. ABA suppresses the function of APC/CTE by triggering SnRK2-dependent TE phosphorylation, and GA blocks the action of SnRK2 and accelerates the turnover of OsPYL proteins.

The molecular pathways governing the ABA/GA equilibrium are not fully understood, but transcription factors featuring AP2 domains are believed to be crucial. ABI4, an AP2-type transcription factor, activates genes involved in ABA breakdown and suppresses those responsible for GA production. Consequently, ABI4 dysfunction elevates GA synthesis gene activity and lowers GA degradation gene expression, diminishing primary dormancy in abi4 mutant seeds. Similar to the function of ABI4 in Arabidopsis, the rice AP2 transcription factor OsAP2-39 controls seed germination by affecting the ABA/GA ratio. OsAP2-39 stimulates the expression of the ABA-producing gene OsNCED1 and increases the transcription of the GA-inactivating enzyme OsEUI, amplifying ABA generation and inhibiting GA buildup[63].

Furthermore, oslec1 mutant seeds lose their dormancy early during embryo development. Epigenetic modifications, particularly histone modifications regulated by OsLEC1, directly engage with genetic components regulating ABA/GA metabolic pathways and signaling cascades, affecting dormancy regulation in rice seeds[64]. The disruption of GA biosynthesis in rice plants increases the expression of the ABA-responsive transcription factor ARAG1. Regulatory protein OsGF14h orchestrates the balance between ABA signaling pathways and GA biosynthesis routes, affecting germination responses under submergence stress[65].

Key components in the GA signaling cascade have regulatory control over ABA biosynthesis mechanisms. In addition to their inhibitory function in GA signal transduction, DELLA proteins serve as critical intermediaries facilitating hormonal interplay between GA and ABA pathways during seed germination. The DELLA-ICE1-ABI5 transcriptional complex regulates plant ABA hormone signaling and seed germination. The transcription factor Inducer of CBF Expression 1 (ICE1) interacts with both ABI5 and DELLA proteins to form a transcriptional complex, precisely regulating ABA signaling and the seed germination process[66]. XERICO, a gene encoding a RING-H2 zinc finger factor, promotes ABA accumulation. During rice seed germination, XERICO overexpression exhibits hypersensitivity to exogenous ABA. The genetically modified variants exhibit elevated levels of naturally occurring ABA and increased transcriptional activity in both OsNCED and OsABI5 genes[67].

-

ETH functions as a fundamental gaseous phytohormone with diverse regulatory roles. This compound modulates metabolic processes on varying biological scales, from molecular interactions to systemic plant responses. In both optimal growth environments and stressful situations, ETH coordinates with other signaling compounds to direct physiological adaptations[68].

ETH metabolism and signal transduction

-

The metabolic route for ETH production in sprouting seeds mirrors that found in plant tissues. Methionine undergoes conversion to S-adenosyl-methionine (S-AdoMet), which is transformed into 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) before yielding ETH. Researchers regard ACC synthesis as the critical bottleneck governing the ETH generation process.

The ETH signaling cascade operates through a sequential mechanism in which ETH receptors function as inhibitory components, suppressing CTR1 activity and stimulating the cytoplasmic activator Ethylene insensitive 2 (EIN2). This signal reaches nuclear-localized EIN3/EIL transcription factors, triggering ERF transcription factor production, which activates ETH-responsive genetic networks. Among ETH receptors, ETR1 plays a pivotal role in the ETR protein group. Positioned on the endoplasmic reticulum membrane, it primarily detects ETH before initiating negative feedback regulation of ETH-mediated processes[69]. Regarding transcriptional regulation, EIN3/EIL proteins serve as central mediators in ETH signaling. Rice genome analyses have successfully identified these regulatory factors. Structural examinations have shown that EIN3/EIL1 possesses three distinct functional regions: a DNA recognition motif, a protein interaction segment, and a terminal regulatory portion. These transcription factors exhibit specific binding affinity for PERE motifs upstream of target genes, such as ERF1. Through these interactions, they modulate early ETH-responsive gene clusters, coordinating physiological responses to ETH. Five ETH receptor homologs, designated as OsERS1, OsERS2, OsETR2, OsETR3, and OsETR4, have been characterized in rice.

Rice possesses conserved ETH signaling components, including ETH receptors (OsERS2), OsRTH1, OsCTR2, OsEIN2, OsEBFs, and OsEIL1. Two branched pathways have been proposed downstream of the ETH receptor. In addition to the well-established receptor-CTR2-OsEIN2-OsEIL1 signaling cascade, recent studies have identified an alternative MHZ1-AHP1/2-OsRR21 phosphorelay mechanism that is directly controlled by OsERS2, mediating ETH-dependent responses in rice root systems. When ETH is absent, the activated ETH receptor exhibits dual functionality, stimulating OsCTR2 activity to suppress the canonical ETH pathway and interacting with Histidine kinase 1 (MHZ1) to restrict its enzymatic function, which blocks the phosphotransfer cascade. Upon ETH perception, the receptor loses its ability to activate OsCTR2 but relieves MHZ1 suppression, enabling the simultaneous activation of both signaling routes.

The coordination of MHZ1-dependent phosphotransfer mechanisms and OsEIN2-mediated signaling networks orchestrates the expression of multiple downstream targets that control root development. A recent investigation has revealed novel components, such as the endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein MHZ3[70], which participates in these regulatory interactions.

Effects of ETH on rice seed germination

-

ETH promotes coleoptile elongation and inhibits the expansion of the coleoptile tip. This dual effect is more conducive to the coleoptile's rapid penetration of obstacles, such as soil, providing access to oxygen and light in the air and ensuring the morphogenesis of rice seedlings. Several genes related to the ETH signaling pathway and homologous to Arabidopsis genes have been identified in rice. The mutation of OsERS1 enhances the sensitivity of etiolated rice seedlings to ETH, delaying root growth[71]. RICE RTE1 HOMOLOGUE (OsRTH) overexpression reduces the sensitivity of rice seedlings to ETH, impeding root development and coleoptile elongation. OsEIN2 antisense plants have poor development, severely inhibited tiller growth, and significantly reduced expression of ETH-responsive genes. Plants overexpressing OsEIL1 show enhanced ETH responses, and both the roots and shoots of these plants are shorter compared to the wild type.

ETH enhances seed germination by modulating GA biosynthesis or related signaling cascades and functions as an ABA antagonist in Arabidopsis and other plant species[72]. OsJMJ718 eliminates H3K9me3 methylation marks from OsPP2C and OsERF genes, triggering their transcriptional activation, simultaneously suppressing ABA-mediated signaling and stimulating ETH-dependent pathways, which accelerates rice seed germination (Fig. 2). Genes within the rice MHZ family participate in ETH responsiveness and early seedling growth, with MHZ4 restricting root development in rice by promoting ABA accumulation[73].

-

IAA functions as a crucial signaling compound in plants, governing nearly every facet of botanical growth and maturation and encompassing structural formations and adaptations to external stimuli[74]. Seed dormancy and sprouting processes are controlled by intracellular IAA levels and the responsiveness of cellular structures to this phytohormone[75].

IAA biosynthesis and signal transduction

-

IAA is synthesized, stored, and deactivated via multiple pathways and is perceived and transduced via canonical and non-canonical pathways. Tryptophan serves as a primary building block for IAA production across various plant species and bacterial organisms[76]. The indole-3-pyruvic acid route represents the initial fully characterized and evolutionarily preserved mechanism for IAA generation in plants. According to Mano and Nemoto[77], plants also have the capacity to synthesize IAA through the indole-3-acetamide process, which has been confirmed in staple crops, including corn and rice[78].

IAA metabolism includes biosynthesis, conjugation, and degradation, which regulate auxin gradients and intercellular and intracellular transport. Biosynthesis of the IAA precursor L-tryptophan occurs in plastids[79]. Subsequent IAA biosynthesis, catabolism, and conjugation reactions take place in the cytoplasm. The indole-3-pyruvic acid (IPyA) biosynthesis pathway serves as the principal mechanism for generating IAA in plant systems and involves sequential enzymatic conversions. Tryptophan initially undergoes deamination via the action of TRYPTOPHAN AMINOTRANSFERASE OF ARABIDOPSIS 1 (TAA1) and its associated TAR proteins, yielding IPyA as an intermediate. The subsequent decarboxylation of IPyA occurs via YUCCA (YUC) family flavin-dependent monooxygenases, which is both the decisive and non-reversible step in this metabolic sequence[80].

IAA signal transmission mechanisms involve standard and alternative auxin response routes, which are principally governed by two genetic groups: AUXIN RESPONSE FACTORS (ARFs) and Auxin/Indole-3-acetic acid (Aux/IAA) proteins. There are three distinct transmission routes: the nuclear signaling cascade involving Aux/IAA-TIR1 (Transport inhibitor response 1) interactions; the membrane-initiated signaling route; and the SKP2A-dependent signaling mechanism. In the primary auxin response system, the hormone attaches to transport inhibition resistant1/auxin signaling Fbox (TIR1/AFB) proteins and Aux/IAA transcriptional inhibitors. The SCFTIR1/AFB ubiquitin ligase assembly facilitates ubiquitin transfer to Aux/IAA proteins, resulting in their polyubiquitination and breakdown through 26S proteasome activity. This proteolytic process removes the inhibitory constraints on ARFs, initiating the expression of auxin-responsive genetic elements. Secondary auxin signaling mechanisms feature routes controlled by TIR1, Arabidopsis thaliana ETTIN, and receptor-like kinase molecules.

Regardless of whether they are extracellular or intracellular, auxin receptors must possess two essential characteristics: the ability to directly bind auxin and to trigger subsequent downstream biological responses[81]. Auxin and CK, which are crucial plant hormones, interact synergistically or antagonistically, regulating development processes and affecting plant growth in response to environmental stimuli[82,83]. Currently, three distinct auxin signal transduction pathways have been identified: the nuclear Aux/IAA-TIR1 signaling pathway; the cell surface-initiated signaling pathway; and the SKP2A-mediated signaling pathway. Among them, the nuclear Aux/IAA-TIR1 pathway mediates auxin-induced transcriptional regulation, and the cell surface-initiated signaling pathway facilitates rapid, non-transcriptional responses to auxin. Collectively, these pathways highlight the complexity and versatility of auxin signaling mechanisms in plants.

IAA regulates rice seed dormancy and germination

-

Specific ARFs, particularly ARF10 and ARF16, enhance ABA signaling via their regulation of ABI3 gene expression. The application of GA4 to ga1 mutant seeds increases the transcription of auxin transport genes, including AUX1, PIN2, and PIN7. The AUX1 transporter is crucial for ABA-mediated germination suppression, with its defective mutants showing reduced ABA sensitivity. Comparative studies have revealed the elevated activity of both auxin influx and efflux carriers in after-ripening versus dormant seeds, demonstrating their involvement in germination[84]. These observations suggest that multiple auxin signaling mechanisms influence germination by modulating ABA and GA hormonal pathways.

IAA7/AXR2 and IAA17/AXR3 serve as transcriptional suppressors within the auxin signaling cascade governed by TIR1/AFB receptors[85]. The axr2-1 and axr3-1 mutants, which have gain-of-function properties, demonstrate compromised auxin response mechanisms. Their dormancy levels are similar to those of tir1 afb2 and tir1 afb3 seeds, which show significantly faster germination than the wild type. Additionally, ARF10, ARF16, and ARF17 from the ARF family are key transcription factors in this response. ARF10/ARF16 can directly regulate seed dormancy genes or interact with other hormones through intermediate mediators to co-regulate this process[32]. The screening of previous studies has revealed functional genes in ABA biosynthesis and signal transduction pathways[86]. These genes commonly feature one or more auxin responsive binding elements (AuxREs), with the core motif TGTGTC in their promoter regions[87].

OsIAGLU activation results in substantial responsiveness to both IAA and ABA treatments, with consistent induction observed during treatment periods ranging from 12 to 72 h. Germinating seeds of osiaglu mutants exhibit elevated unbound IAA and ABA concentrations relative to standard rice varieties[88]. The regulatory influence of OsIAGLU on seed vitality likely involves its capacity to affect OsABI gene expression patterns, mediating the crosstalk between IAA and ABA signaling pathways during rice seed sprouting (Fig. 2). Notably, during the germination phase, the transcriptional levels of OsABI3 and OsABI5 maintained persistent elevation in osiaglu genetic variants compared to conventional wild-type specimens[88]. This suggests that the elevated endogenous IAA and ABA levels in germinating osiaglu mutant seeds increase the expression of OsABI3 and OsABI5, reducing vigor in the mutant seeds. OsCNLs regulate rice seed flooding germination via the interaction between SA and IAA metabolism[89].

The auxin-inducible gene OsSAUR33 plays a crucial role in determining rice seed viability (Fig. 2). OsSAUR33 expression increases substantially in fully developed grains and during initial sprouting stages, forming molecular complexes with OsSnRK1A, a key sucrose metabolism regulator. The disruption of the function of OsSAUR33 alters transcriptional patterns of carbohydrate-responsive genes in germinating seeds and increases free sugar concentrations. These physiological changes reduce the germination efficiency and seed vitality[90]. Auxin is also regulatory in rice grain development. The rice auxin oxidase gene DAO encodes a glutarate- and ferrous-dependent dioxygenase that oxidizes active IAA into inactive OxIAA, thus participating in auxin metabolism and homeostasis. By regulating IAA levels, DAO affects the auxin signaling cascade. A novel mechanism involving IAA, OsARF18, OsARF2, and OsSUT1 has been shown to mediate carbohydrate allocation during rice reproductive development, contributing to increased grain yield. Furthermore, the loss of function in OsARF4 increases the rice grain size.

-

Studies have shown that CK and signal transduction pathways in seeds regulate their development, dormancy, and germination[91]. The dormancy acquired in the maternal plant during seed maturation is termed primary dormancy, and its induction and maintenance are regulated by plant hormones[6]. After ripening, a method used to break seed dormancy also regulates seed dormancy and germination by affecting CK levels and signal transduction[92].

CK metabolism and signal transduction

-

CK represents a crucial phytohormone that profoundly impacts development mechanisms in plants and governs key agricultural responses, such as growth regulation, nutrient perception, and stress adaptation. The CK production pathway is initiated by a pivotal rate-determining reaction mediated by isopentenyltransferase (IPT), an enzyme that facilitates the transfer of isoprenoid moieties from dimethylallyl diphosphate to adenosine phosphates (AMP/ADP/ATP), generating isopentenyladenine nucleotide derivatives (iP nucleotides)[93,94]. Following this step, iP nucleotides undergo transformation into trans-zeatin (tZ) nucleotides via hydroxylation, which is facilitated by cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (CYP735A). The concluding phase involves CK nucleoside 5'-monophosphate phosphoribohydrolase, which is commonly referred to as 'Lonely Guy' (LOG), catalyzing the activation of both tZ and iP nucleotides. This enzymatic process directly generates biologically active free CKs, including zeatin and isopentenyladenine (iP)[75]. These enzymatic steps collectively constitute the essential pathway for CK biosynthesis, highlighting their critical roles in plant growth and environmental response mechanisms.

Plant CK concentrations are controlled by dual mechanisms involving their production and breakdown. Cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase (CKX) irreversibly cleaves free CKs and CK nucleosides at the N6 side chain, reducing the levels of biologically active CKs. Studies have shown that CKX overexpression decreases internal CK concentrations and multiple growth abnormalities. Although trans-zeatin and isopentenyladenine undergo CKX-mediated breakdown, dihydrozeatin and artificial CKs, including kinetin and 6-benzylaminopurine, remain unaffected by CKX activity. Plant cells detect CKs through plasma membrane-bound histidine kinase receptors, with subsequent signal transmission occurring through phosphorelay mechanisms that stimulate nuclear transcription factors[95]. The production and catabolism of these phytohormones are controlled by intrinsic developmental cues and external environmental stressors.

The CK signaling cascade operates through a dual-component mechanism that involves three core elements: histidine (His) kinase receptors (HK); intermediate His-containing phosphotransfer proteins (HP); and terminal response regulators (RR). This molecular relay system facilitates plant hormone perception and cellular responses. HK acts as the CK receptor, and HP transmits the signal from HK to nuclear RRs, regulating target gene transcription. The CK signal transduction pathway involves a His-Asp phosphotransfer, similar to bacterial two-component signaling systems, which are the main pathways by which bacteria sense and respond to environmental stimuli[96]. In these bacterial systems, the key signaling components are membrane-localized sensor kinases that sense environmental stimuli and response regulators, which transmit the signal through immediate control over the expression of specific target genes. The signaling mechanism involves phosphate transfer from a His residue within the sensor component to an Asp residue in the regulatory domain of the response regulator.

CK regulates rice seed germination and dormancy

-

Research has shown that CK suppresses OsMT2b gene activity, indicating a regulatory loop in which OsMT2b modulates CK concentrations. Observations in OsMT2b-overexpressing rice plants reveal its critical function in root formation and seed embryo development. The protein appears to stabilize CK concentrations within optimal ranges. Alterations in OsMT2b expression patterns disrupt the CK balance in transgenic specimens, demonstrating its role in preserving CK equilibrium during the rice life cycle[97].

In the CK signaling cascade in rice, the hormonal signal is initially detected by histidine kinases before being relayed through histidine phosphotransfer proteins to type-B response regulators, potentially decreasing OsMT2b expression[97]. During wheat grain development, the transcriptional activity of TaAHK4, TaARR9, and TaARR12 progressively decreases in embryos of both 'AC Domain' and 'RL4452' cultivars. Comparative analysis 20 d after flowering has shown that TaARR12 exhibits reduced expression in the AC Domain embryos compared to RL4452. Functioning as an activator of CK signaling, the diminished activity of TaARR12 in AC Domain may suppress CK-mediated processes and promote seed dormancy establishment. Conversely, in wheat line RL4452, the increased sensitivity to CK inhibits seed dormancy. At 20–30 days after anthesis (DAA), TaARR9, an A-type ARR that negatively regulates CK signaling, reduces the sensitivity of AC Domain.

CK can reverse the inhibitory effect of ABA on seed germination. ABI5 physically interacts with ARR4-6, and the ARR-ABI5 complex of type A potentially obstructs the binding between the ABI5 protein and proteasomal degradation machinery. CKs suppress the transcriptional activity of auxin-producing genes IAMT1 and ILL6 and activate the catabolic gene GH3.6. Additionally, CK stimulates the expression of AUX/IAA transcriptional repressor SHY2/IAA3, functioning as an antagonist in auxin signaling pathways. An experimental study has shown that the germination potential is correlated with ETH biosynthesis and that external ETH application or ethephon (an ETH donor compound) effectively terminates both primary and secondary seed dormancy states[7]. CK promotes ETH biosynthesis by activating ACC synthase via transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms, and ETH production promotes hypocotyl elongation and inhibits root growth in dark-grown seedlings inhibited by CK. Furthermore, B-type ARRs bind to many genes affecting ETH signal transduction.

In cereal species, including corn, wheat, and barley (Hordeum vulgare), CK concentrations exhibit an initial surge post-pollination followed by a gradual reduction during seed development. Within the grain structures of staple crops, such as corn and rice, these plant hormones predominantly accumulate in the growing endosperm tissue, stimulating the mitotic activity of embryonic cells[98].

-

The d61 genetic variant, which demonstrates BR insensitivity in rice, shows retarded germination kinetics, requiring 12 additional hours to achieve complete germination compared to normal plants. Furthermore, the coleoptile length of d61 seeds is shorter than that of wild-type seeds. Similarly, OsGSK2 overexpression results in germination rate and coleoptile length trends similar to the d61 mutant.

For seeds in which BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT 1 (BZR1) signaling is affected, the soluble sugar content of bzr1-d4 was lower than that of the control after 96 h of germination, consistent with the results for α-amylase activity. Consequently, the proposed mechanism suggests that BRs regulate rice seed germination by altering the metabolic conversion rate of stored starch into soluble carbohydrates, primarily through the transcriptional control of α-amylase biosynthesis. The central regulatory component BZR1, functioning as a terminal effector in BR signaling cascades, facilitates germination processes via direct interaction with RAmy3D's regulatory sequences (coding for α-amylase 3D), thereby enhancing both enzymatic expression levels and catalytic functionality. This BZR1-RAmy3D transcriptional module regulates starch degradation in the endosperm, promoting seed germination[99].

The effect of BR on rice root vitality may be a primary reason for its promotion of rice growth, while its influence on the activities of POD, CAT, and SOD in rice seedlings likely underlies its enhanced stress resistance. Although 50 mg/L ABA inhibits rice seed germination, 10 mg/L BL can significantly counteract this inhibitory effect, indicating the interactive regulation of plant seed germination by BR and ABA[100].

Strigolactones, jasmonates, and salicylates

-

In rice, five distinct DWARF (D) genes play critical roles in SL production (D10, D17/HTD1, and D27), SL signal reception (D3), and subsequent processing of SL-derived signals. When grown under dark conditions, these SL compounds actively suppress cellular division within the mesocotyl tissue during seed sprouting and seedling development.

In rice, the ABA-responsive transcription factor OsbZIP82 enhances JA levels through the direct transcriptional control of JA biosynthesis-related genes. Exogenous ABA induces the autophosphorylation of SAPK10 at serine177, enabling SAPK10 to phosphorylate bZIP72 at serine71. Phosphorylation facilitated by SAPK10 strengthens the durability of the bZIP72 protein, protecting it from breakdown by the 26S proteasome while simultaneously improving its binding capacity to G-box regulatory sequences in the AOC promoter region. Consequently, this mechanism increases AOC gene expression and JA levels, having a synergistic suppression effect on rice seed sprouting. The enzyme OsUGT75A controls the concentrations of unbound ABA and JA in embryonic tissues through glycosylation modifications, establishing regulatory control over coleoptile extension during submergence stress through interconnected ABA and JA transduction cascades[101].

SA is a crucial phytohormone involved in plant defense mechanisms. Research has shown that SA enhances rice seed germination during flooding by modulating auxin degradation pathways. Applying exogenous SA improves rice seed germination rates under saline conditions[102]. Different rice cultivars exhibit varying responsiveness to SA treatment when exposed to salt stress, depending on their inherent salt tolerance.

-

Seed germination is the crucial beginning of the plant life cycle, representing a complex and sophisticated multi-step process. During this process, the initially static, dry seed rapidly awakens its dormant metabolic machinery, enabling the embryo to break through surrounding tissues, which lays the foundation for vigorous seedling growth. This critical developmental node is regulated by both environmental signals and plant hormones, with mechanisms realized through the precise coordination of gene expression networks and the flexible operation of metabolic pathways.

Of the plant growth regulators, ABA stands out as a thoroughly investigated phytohormone. It serves as a crucial modulator governing shifts in seed maturation, quiescence, and sprouting phases. Additionally, it influences a plant's capacity to withstand water deficit conditions, affecting both crop productivity and seed characteristics[6,103]. Since the 1960s, ABA metabolism, physiological functions, and signal transduction pathways have been research focal points in plant science, leading to numerous groundbreaking advances. However, despite this progress, core scientific questions still urgently require clarification. For example, the metabolic homeostasis of ABA relies on the deactivation process catalyzed by the CYP707A family (conversion to 8'-hydroxy-ABA and spontaneous isomerization to PA), storage mediated by ABA glucosyltransferases (conversion to ABA-GE), and hydrolytic release catalyzed by β-glucosidases, but it remains unclear how these key enzymes and their genes precisely respond to plant developmental stages and environmental conditions to maintain normal intracellular ABA concentrations that are adapted to different physiological needs. Furthermore, DOG1 and AHG1/AHG3 regulate seed dormancy and germination by operating in parallel with core ABA signaling pathways SnRK2 and ABI5, which intersect at the PP2C component[9]. A deeper question is how PP2C selectively responds to a specific pathway when integrating complex physiological states or diverse environmental signals. How do these two pathways coordinate to achieve precise control over the seed fate? Are there undiscovered targets for PP2C? These unknowns constitute critical barriers to understanding the complexity of the ABA regulatory network.

The metabolism, physiological roles, and signal transduction of GA, another hormone with significant germination-promoting effects, have also been extensively studied, resulting in important applications in agricultural production[104]. Through genetic and molecular biological analyses in model plants, such as rice and Arabidopsis, research has successfully identified the main components of the GA signal transduction pathway and elucidated its mode of action. GA-induced DELLA protein degradation acts as the 'on switch' for signal transmission[105]. In addition to their role in transcriptional control, DELLAs directly participate in microtubule reorientation in Arabidopsis hypocotyls. DELLA protein hydrolysis-independent GA signal transduction pathways also exist in plant cells[106]. However, it is unclear whether DELLA proteins regulate new downstream targets and what their relationships are among downstream DELLA targets with different functions. Therefore, the following questions remain to be addressed: when responding to different physiological or environmental signals, which pathway, the classic DELLA-dependent pathway or the non-classic pathway, is preferentially activated? What interrelationships and synergistic effects exist between them? The GA receptor GID1 has dual localization in the cytoplasm and nucleus. The functional distinction and significance of the differential subcellular localization for GA signal perception and subsequent signal transduction processes are also areas requiring future in-depth exploration.

In addition to ABA and GA, other hormones, such as ETH, play important roles. ETH significantly promotes seed germination and dormancy release by affecting the biosynthesis and signal transduction of ABA and GA, highlighting the complex network of hormone interactions. Therefore, the specific mode of action by which ETH promotes seed germination—whether it is a direct effect or primarily achieved by regulating the balance of ABA and GA—still requires further experimental evidence for confirmation[73]. Determining how ABA and GA affect ETH biosynthesis and signaling pathways in seeds is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of this interactive network. Reactive oxygen species, as important signaling molecules, influence seed germination by forming complex regulatory networks with hormones, including ABA and GA. Distinguishing the hierarchical relationships of different signaling pathways and dissecting their roles in perceiving environmental signals will be important directions for future research. In a recent study on the epigenetic regulation mechanism of rice seed germination, Jia et al. found that OsJMJ718 regulates seed germination by affecting the ABA signaling pathway[73], suggesting that the regulation of seed germination and dormancy extends beyond the levels of hormones and gene expression. Epigenetic modifications are a crucial, indispensable link, and strengthening research on the epigenetic regulation of seeds will help fill the gaps in our understanding of the mechanisms controlling seed germination and dormancy.

The diversity of auxin biosynthesis and catabolism pathways also brings new questions. It is currently unclear whether these pathways coexist in the same tissue of the same species or if they exhibit specificity across different species, tissues, and development stages. A more important concern is how these synthesis and metabolic pathways are initiated, coordinated, and dynamically balanced to precisely regulate auxin levels within tissues and cells during plant growth, development, and responses to environmental changes. Auxin signal transduction is complex, including canonical and non-canonical signaling pathways. In the non-canonical auxin signal transduction pathway, auxin enters cells via the AUX1 transporter and is perceived by the SCFTIR1/AFB receptor complex localized in the nucleus and TIR1 in the cytoplasm[107]. However, similar to the issues faced in GA and ABA signaling pathways, it remains unclear which of the canonical and non-canonical auxin signaling pathways responds when integrating physiological conditions or environmental signals, and the internal connections between these two pathways are unknown. Furthermore, the downstream events of non-canonical auxin signaling still await in-depth analysis.

The auxin-induced acid growth model provides a mechanistic explanation for cell elongation. Auxin activates plasma membrane-localized H+-ATPase proton pumps, pumping protons into the cell wall matrix, which leads to cell wall acidification. The acidic environment then activates potassium channels, promoting K+ influx into the cytoplasm, maintaining turgor pressure, and activating cell wall loosening proteins (expansins) and related enzymes, which loosens the polysaccharide connections in the cell wall, increases cell wall extensibility, and drives rapid cell elongation. Functional analysis of OsEXPA8, a cell wall loosening protein in rice, has confirmed the importance of cell wall loosening for plant growth, such as its role in improving the rice root structure. The embryo protrusion required for seed germination primarily relies on cell elongation in the hypocotyl–radicle transition zone rather than cell division, and low auxin concentrations (0.05–5 nmol/L) promote seed germination[108]. Therefore, the hypothesis that low auxin concentrations promote seed germination by inducing the acid growth model is worth investigating. Verification of this model may provide new perspectives for understanding the mechanical mechanisms of seed germination.

Epigenetic regulation plays a crucial role in rice dormancy and germination by modulating phytohormone biosynthesis and signaling. Fertilization-independent endosperm1 (OsFIE1), which is expressed in the maternal source, is the core component of Polycomb inhibitory complex 2 (PRC2), inhibiting target gene expression by catalyzing H3K27me3 modification. OsPIE1 deficiency leads to abnormal endosperm development, thickening of the endosperm layer, and the upregulation of ABA synthesis genes, such as OsNCEDs, which increase seed ABA accumulation and prolong the dormancy period. OsFIE1 overexpression reduces ABA levels and promotes germination but increases the risk of spike germination[109]. Chen et al. identified a lncRNA, vivipary, which is specifically expressed in embryos and promotes the release of seed dormancy by regulating ABA signaling. Vivipary regulates seed dormancy and PHS in rice by regulating ABA signaling and the chromatin structure, providing a potential target for the improvement of agronomic traits[110]. Due to the unique advantages of epigenetics in revealing major scientific issues in the life sciences, such as Song's research on the key role of cold stress-induced DNA methylation variations in rice adaptation to high latitude and low temperature environments, direct molecular evidence has been provided for Lamarck's theory of 'acquired genetics'[111]. The epigenetic regulation mechanisms related to seed dormancy and germination need to be further explored.

Considering the complexity of the regulatory mechanisms of seed germination and dormancy, the integration of multi-omics technologies has become a trend. Combining data from transcriptomics, translatomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and environmental omics with studies involving ABA, GA, ETH, and other hormone-related mutants and corresponding inhibitor experiments and constructing a new multi-omics research system for plant hormones affecting seed germination and dormancy release will greatly facilitate the systematic exploration of the complex regulatory networks behind this miraculous beginning of life.

This work was supported by grants from the Guangdong Provincial Key Research and Development Program (Grant Nos 2022B0202110003, 2024B1212060007), and the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31871716).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Liu J, Yang C; data collection: Shi X, Jia J; draft manuscript preparation: Shi X, Jia J, Liu J; revision of the manuscript: Song S, Dai Z, Luo Y, Wang Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Xinyue Shi, Junting Jia

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Laboratory. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Shi X, Jia J, Song S, Dai Z, Luo Y, et al. 2025. Research progress in rice seed dormancy and germination regulated by plant hormones. Seed Biology 4: e018 doi: 10.48130/seedbio-0025-0017

Research progress in rice seed dormancy and germination regulated by plant hormones

- Received: 05 May 2025

- Revised: 11 August 2025

- Accepted: 15 August 2025

- Published online: 28 October 2025

Abstract: Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is a globally significant agricultural commodity that is crucial for maintaining stable food supplies worldwide. The speed and uniformity of seed germination are fundamental prerequisites for achieving optimal rice productivity and grain excellence. Seed germination is a result of complex interactions between hereditary traits and external conditions. Hormonal control governs the termination of dormancy termination and the initiation of sprouting initiation, a process that is evolutionarily preserved across seed-bearing flora. Abscisic acid (ABA) functions as a stimulant for dormancy initiation and preservation, and simultaneously inhibits the germination process. Conversely, gibberellins (GAs) actively facilitate seedling emergence following dormancy cessation. Ethylene regulates the germination and dormancy of many species via complex signaling networks. The auxin signaling cascade contributes to seed sprouting by regulating the ABA and GA signaling networks. Germination exhibits dose-dependent responsiveness to auxin levels, and cytokinins actively stimulate seed sprouting. In addition to these primary regulators, secondary plant growth substances, including brassinosteroids, strigolactones, jasmonates, and salicylates, significantly contribute to germination modulation mechanisms. This comprehensive analysis focuses on contemporary scientific advancements in understanding the molecular mechanisms of phytohormonal regulation of dormancy and germination processes in rice. Finally, we outline the scientific issues that require further research in this field and provide references for future studies on the molecular mechanisms by which plant hormones regulate rice seed dormancy and germination, as well as the development of new rice varieties.

-

Key words:

- Rice /

- Dormancy /

- Germination /

- Seed /

- Plant hormone