-

Seed germination is a complex and highly ordered biological process[1,2]. Germination is the process that begins with the uptake of water by a dry seed and ends with the emergence of part of the embryo (usually the radicle) from the surrounding tissues[1,3]. Strictly speaking, germination is considered complete upon radicle emergence, and does not include subsequent seedling growth[4]. During germination, stored nutrient reserves are rapidly mobilized to support the early growth of the seedling[5]. The process begins with the imbibition phase, during which the embryo quickly absorbs water and exits dormancy. At this stage, there are no visible morphological changes in the seed, but its physiological state has already been transformed. Next, the rate of water uptake slows down, metabolic processes such as transcription and translation resume, while the radicle cells divide and elongate to penetrate the seed coat. Finally, as the seedling continues to grow, water uptake increases again, coinciding with the complete degradation and utilization of the seed's nutrient reserves to sustain seedling growth[6].

Allelochemicals originating from plants/microorganisms/environment can either inhibit or promote the germination of seeds from various species through allelopathic interactions, thereby shaping the composition/distribution of plant communities and influencing ecosystem balance. These compounds also play a significant regulatory role in agricultural microenvironments and production systems. Among various sources, plants are one of the primary producers of allelochemicals. As early as AD 77, the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder observed that Juglans nigra (J. nigra) exerted toxic effects on surrounding plants[7]. Subsequent studies have elucidated that juglone (5-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone), a secondary metabolite biosynthesized in J. nigra, exerts significant phytotoxic effects on seed germination/seedling development of surrounding plant species[8].

Plant-derived allelochemicals suppress the germination of surrounding seeds, thereby playing a crucial role in maintaining ecosystem stability and preserving species diversity. For example, allelochemicals produced by Eupatorium adenophorum can significantly inhibit seed germination in sensitive species such as pea[9], while exerting minimal effects on less sensitive species like Medicago sativa (M. sativa)[10]. In agricultural settings, allelochemicals are regarded as promising candidates for developing eco-friendly herbicides. For instance, aqueous leaf extracts from poplar and Paulownia trees significantly inhibit seed germination in wheat, maize, and soybean[11]. Similarly, the rice accession PI312777 has been shown to effectively suppress the germination and emergence of barnyard grass (Echinochloa crus-galli), demonstrating considerable potential as a natural herbicide[12,13].

Understanding the structural diversity, ecological sources, and release mechanisms of these compounds is essential to contextualize their roles in germination regulation. The following section discusses major classes of plant allelochemicals and their pathways into the environment.

-

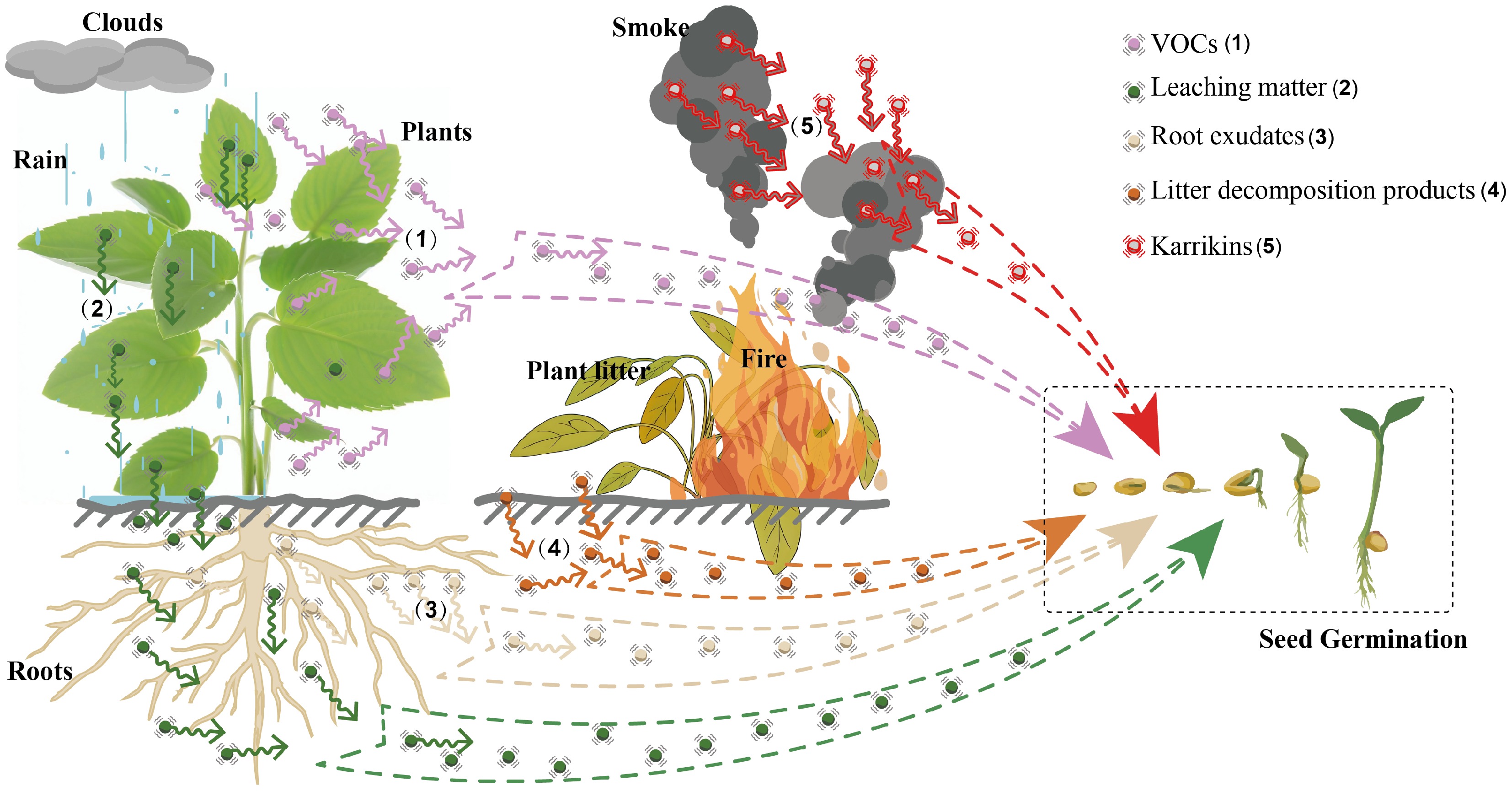

Plants release allelochemicals into the environment through several pathways: leaching, volatilization, root exudation, and residue decomposition (Fig. 1)[14,15]. Leaching occurs when rainwater or dew dissolves bioactive compounds from aerial plant parts, such as leaves, flowers, stems, and branches, and carries them into the soil or surrounding areas. For instance, Ambrosia artemisiifolia releases terpenoids via leaching, which inhibit the germination of soybean, maize, and wheat seeds[16]. Volatilization involves the emission of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) directly from plant tissues into the air, where they can influence neighboring plants. For example, Eucalyptus citriodora emits α-terpineol, which suppresses cucumber seed germination and radicle elongation[17]. Similarly, VOCs from Artemisia frigida significantly reduce seed germination and seedling growth in adjacent plants[18]. Root exudation refers to the active secretion of chemicals by plant roots into the soil. In Erigeron annuus, for instance, root exudates contain (5-butyl-3-oxo-2,3-dihydrofuran-2-yl)-acetic acid, which inhibits lettuce seed germination[19]. Residue decomposition entails the release of small-molecule allelochemicals during the breakdown or burning of dead plant material. These compounds enter the soil or atmosphere and influence plant interactions through soil or aerial pathways. For example, Eucalyptus litter and its leachates release various small molecules during decomposition, restricting the regeneration of native plants[20]. Additionally, smoke from forest fires contains karrikins, such as karrikinolide, which can stimulate seed germination and aid in post-fire ecosystem recovery[21].

Figure 1.

Release pathways of plant allelochemicals into the environment. Plant allelochemicals originate from intrinsic plant metabolism and are released into the environment through five primary pathways: (1) VOCs are emitted into the atmosphere through volatilization; (2) water-soluble phytochemicals enter the soil via leaching by precipitation (rain or dew); (3) diverse metabolites are secreted into the rhizosphere through root exudation; (4) low-molecular-weight compounds are produced and released into the soil through microbial decomposition of dead plant tissues; and (5) allelopathic compounds such as karrikins are generated and released into the environment through the combustion of plant residues. These released small molecules subsequently come into contact with seeds in the surrounding environment, influencing their germination.

Plant-derived allelochemicals range from simple hydrocarbons to structurally complex polyaromatic compounds, including phenolics, flavonoids, terpenoids, and alkaloids, many of which have been reported to influence seed germination[22,23]. Broadly speaking, certain known plant hormones and growth regulators are also considered plant-derived allelochemicals. After synthesis in plants, these molecules can diffuse into the surrounding environment and regulate the growth and development of other species, including seed germination. For instance, strigolactones, a group of sesquiterpenoid compounds derived from carotenoids, are secreted from roots and stimulate the germination of root parasitic plants. Other compounds, such as dihydroquinones and sesquiterpene lactones, exhibit similar effects[24]. In addition, gaseous molecules such as nitric oxide (NO) and ethylene, along with fire-derived compounds like karrikins, can enter the environment and modulate seed germination in neighboring plant species[21,25,26]. Given that the biosynthesis and molecular mechanisms of these compounds have been extensively studied and reviewed elsewhere, they will not be further elaborated upon in this article.

Phenolic compounds are a class of molecules characterized by the presence of one or more hydroxyl groups attached to a benzene ring, which typically exist in the form of monomers or complex polymers[27]. Monomeric phenolics are structurally simple, low-molecular-weight compounds featuring one or more phenolic rings. Common examples include phenolic acids like p-hydroxybenzoic acid, vanillic acid, and protocatechuic acid (with hydroxyl and carboxyl groups on the ring), as well as p-coumaric, caffeic, and ferulic acids (which possess a propionic acid side chain). Flavonoid monomers, such as quercetin, kaempferol, and apigenin, also fall into this category. Complex phenolic compounds are formed by the polymerization of monomeric phenolics. Examples include lignin, which is composed of polymers of cinnamic acid derivatives (e.g., coniferyl alcohol, sinapyl alcohol); hydrolyzable tannins formed by the conjugation of gallic acid or ellagic acid with sugars; and proanthocyanidins formed through the polymerization of flavan-3-ols. Phenolics are synthesized and accumulated in various plant tissues, including roots, leaves, stems, flowers, fruits, and seeds. Their concentration and distribution are jointly regulated by plant species, developmental stage, and environmental factors. For instance, environmental stressors such as drought, salt stress, UV radiation, and pathogen infection can significantly influence the synthesis of flavonoids in plants[28−30]. Various phenolic compounds have been identified in soil, and their seasonal fluctuations may be attributed to microbial utilization of these compounds as carbon sources[31].

Terpenoids are a large class of isoprenoid derivatives widely distributed in nature and represent one of the most prominent groups of allelochemicals. Terpenoid biosynthesis primarily involves two metabolic pathways: the mevalonate (MVA) pathway and the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway. The MVA pathway occurs mainly in the cytosol and endoplasmic reticulum, contributing to the biosynthesis of triterpenes (e.g., sterols), polyterpenes, and sesquiterpenes, while the MEP pathway takes place in plastids and is primarily involved in the synthesis of diterpenes, monoterpenes, and carotenoids[32]. The environmental distribution of terpenes is influenced by factors such as plant species, soil properties, environmental conditions, and microbial activity[33,34]. They are released into the environment through several pathways. Volatile terpenoids are emitted into the atmosphere via stomata or directly through the cuticle[35,36], with emission rates increasing significantly following mechanical damage or insect herbivory[37]. Under arid conditions, these volatile terpenoids can accumulate around the plant, forming a 'terpene cloud' that exerts negative effects on adjacent vegetation. Upon rainfall, the compounds are washed into the soil, where they further inhibit the germination of nearby seeds[38]. In addition to aerial release, plant roots (especially those of pine species) actively secrete terpenoids, including monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes such as α-pinene, into the soil[33,34]. Terpenoids are also released during the decomposition of plant litter (e.g., leaves, branches, and roots). For instance, decomposing pine needles release considerable quantities of monoterpenes.

Alkaloids are nitrogen-containing organic bases, typically featuring complex cyclic structures. Their biosynthesis proceeds through class-specific pathways[39,40], many of which involve enzymes or reaction steps that remain unidentified. The production of alkaloids is often upregulated by biotic and abiotic stresses; for example, insect herbivory can induce the accumulation of tomatine in tomato plants[41]. Once synthesized, these plant-derived alkaloids can enter the soil via various pathways, as evidenced by the detection of nicotine residues in soils where tobacco has been cultivated[42].

Other nitrogen-containing allelochemicals produced by plants include non-protein amino acids (NPAAs), amines, and glucosinolates. NPAAs arise from modifications or branch pathways of standard amino acid metabolism, with representative compounds including γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), canavanine, and β-cyanoalanine. The amine class encompasses monoamines, polyamines, aromatic amines, and heterocyclic amines, which are principally formed during microbial decomposition of plant litter and organic matter in soils. Glucosinolates similarly derive from amino acid metabolic pathways, representing another important class of nitrogenous plant defense compounds.

As outlined above, most plant allelochemicals suppress seed germination. Supplementary Table S1 summarizes the major types and plant sources of reported germination-inhibiting allelochemicals. Among these, phenolic acids such as ferulic acid, coumarin, benzoic acid, and vanillic acid significantly inhibit germination across various species, often in a concentration-dependent manner[31,43−45]. The polyphenol epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), for example, suppresses germination in tomato and Arabidopsis[46,47]. Interestingly, some phenolics like those affecting hot pepper seeds can promote germination at low concentrations but inhibit it at higher levels[48]. Many terpenoids also inhibit germination. Examples include wangzaozin A, leukamenin E, and weisiensin B, which delay ryegrass and lettuce germination[49], and α-pinene from Eucalyptus, which inhibits cucumber seed germination[17]. Similarly, α-thujone from Thuja occidentalis suppresses dandelion and Arabidopsis germination[50], while β-caryophyllene from pine litter inhibits grass seed germination[51]. Diterpenoids such as ent-kaurene and phyllocladane from Araucania senescent needles also hinder germination and seedling growth[52]. Notably, oxygenated monoterpenes often show stronger inhibitory effects than non-oxygenated forms, sometimes completely preventing germination[22]. Alkaloids, likewise, can suppress germination at high concentrations, as seen with extracts from Peganum multisectum affecting crops like maize and wheat[53,54], and Cinchona alkaloids inhibiting the germination of various plants, including self-seeds[55].

It is important to note that many reported inhibitory effects of allelochemicals on seed germinat ion are derived from laboratory studies, where the compound concentrations applied often exceed those found in natural settings. In fact, some studies have shown that at environmentally realistic levels, certain allelochemicals do not significantly inhibit and may even promote germination[56]. This has led to the recognition of hormesis as a key concept in allelopathy: a biphasic response where low doses stimulate and high doses inhibit[57]. Mechanistically, low concentrations may mildly enhance antioxidant enzyme activity (e.g., super oxide dismutase, SOD; catalase, CAT), 'priming' seed defenses and promoting germination. High concentrations, however, cause severe oxidative stress, metabolic shutdown, and cellular damage, leading to germination failure. The threshold between these effects varies with the compound, plant species, and environment. Coumarin (1,2-benzopyrone) is a typical example: low doses stimulate germination and root growth, while high doses inhibit them via disrupted respiration and hormone signaling[58]. This hormetic pattern emphasizes that allelochemical effects are concentration-dependent and context-specific. Accurate ecological assessment must therefore consider threshold concentrations, warranting further study under realistic conditions.

Increasing evidence indicates that chemical inhibition of germination may be an adaptive strategy rather than pure toxicity. Suitable concentrations of inhibitors can extend seed dormancy, allowing seeds to sense competition and wait for favorable conditions. Many allelochemicals only delay germination without harming seedlings[59], making them promising natural seed preservatives. On the other hand, various chemicals, including respiratory inhibitors, thiol compounds, oxidants, nitrates, nitrites, and azides, can break dormancy in specific plants[60].

-

The inhibitory effects of plant allelochemicals on seed germination involve multiple aspects, such as the accumulation of ROS, disruption of hormonal balance, and impairment of plasma membrane integrity. A single compound may inhibit germination through multiple pathways, while different compounds may also act synergistically[43,46,61,62]. Common mechanisms and representative examples of how plant allelochemicals inhibit seed germination are summarized in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Multilevel mechanisms of allelochemical-mediated regulation of seed germination. (1) Interference with signal transduction: allelochemicals can modulate oxidative stress responses by inducing ROS bursts or enhancing ROS scavenging systems. They may also disrupt the balance of endogenous hormones, particularly the GA to ABA ratio, thereby influencing the decision to initiate germination. (2) Disruption of energy metabolism: allelochemicals can impair the mobilization of stored reserves (e.g., carbohydrates, proteins, lipids), and inhibit key metabolic processes such as respiration and photosynthesis. By blocking the supply of energy and biosynthetic precursors, they effectively starve the seed of the resources essential for germination. (3) Damage to subcellular structures and function: allelochemicals can compromise seed germination by damaging the structure and function of cellular organelles, including the cell membrane, mitochondria, chloroplasts, and ribosomes, leading to a breakdown in cellular homeostasis. (4) Inhibition of embryonic tissue growth: allelochemicals can directly suppress the growth of embryonic structures such as the radicle, plumule, and hypocotyl. This physical restraint on the expansion and development of the embryo presents a final barrier to the completion of germination.

Disruption of ROS homeostasis

-

The success of seed germination is critically dependent on maintaining a dynamic balance between the production and scavenging of ROS, which play a dual role by either promoting or inhibiting the process[60,63,64]. At moderate levels, ROS facilitates germination by activating GA signaling and suppressing ABA pathways[65]. They can also drive germination through the oxidation of specific proteins or mRNAs[66]. However, excessive ROS accumulation causes severe cellular damage, including to membranes and macromolecules, which may lead to the suppression of germination[67].

Allelochemicals can disrupt the delicate ROS balance, often resulting in germination inhibition. Many induce oxidative stress and trigger ROS bursts in recipient plants. For instance, high concentrations of coumarin alter ROS homeostasis in wheat seeds by interfering with antioxidant enzymes (e.g., SODs; dehydroascorbate reductases, DHARs; monodehydroascorbate reductases, MDHARs) and antioxidants (e.g., ascorbic acid, AsA; reduced glutathione, GSH), thereby inhibiting germination[68]. Myrigalone A (MyA) from Myrica gale suppresses ROS production in garden cress (Lepidium sativum) seeds, hindering cell division and radicle growth[69]. Similarly, α-pinene inhibits germination by disrupting the mitochondrial electron transport chain, leading to elevated ROS levels and membrane damage[70,71]. Conversely, certain plant-derived molecules, such as phthalic acid and p-hydroxybenzoic acid, can promote maize seed germination by enhancing peroxidase activity, scavenging ROS, and protecting cells from oxidative damage[72].

Disruption of hormonal balance

-

Hormonal regulation of seed dormancy and germination is likely a highly conserved mechanism among seed plants. Plant allelochemicals can modulate this process by altering endogenous hormone levels, particularly the balance between GA and ABA, thereby influencing germination[73]. For example, MyA disrupts hormonal equilibrium through multiple pathways. It perturbs the metabolism of GAs, ABA, which in turn affects auxin signaling genes and various transport proteins[69]. A recent study further revealed that MyA directly inhibits the ethylene biosynthetic enzyme 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase (ACO), reducing ethylene production and suppressing Arabidopsis seed germination[74]. Similarly, EGCG elevates ABA levels while reducing GA3, shifting the GA3/ABA ratio and inhibiting germination in tomato[46]. EGCG also influences JA biosynthesis and signaling by modulating key enzymes such as lipoxygenase 2 (LOX2) and downstream targets like VEGETATIVE STORAGE PROTEIN 2 (VSP2), ultimately affecting Arabidopsis germination[47]. Notably, the JA receptor mutant coronatine insensitive1 (coi1) loses sensitivity to EGCG, confirming the involvement of JA signaling in this regulation. Additional examples include the coumarin derivative 4-methylumbelliferone, which inhibits Arabidopsis germination likely by altering the expression of auxin transport genes (PIN-FORMEDs, PINs) and inducing auxin redistribution[44]. Benzoic acid has also been shown to affect auxin accumulation via modulation of auxin transport (AUXIN RESISTANT 1, AUX1; PIN2) and biosynthesis genes[75]. These findings collectively suggest that several allelochemicals inhibit germination, at least in part, through interference with auxin signaling pathways.

Disruption of the energy supply for germination

-

Plant allelochemicals can suppress seed germination by disrupting the mobilization of stored reserves and impairing energy metabolism. These compounds often interfere with the degradation of storage materials, such as carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, and starch, which are essential energy sources during germination. For example, phenolic acids like benzoic acid and cinnamic acid inhibit the activity of hydrolytic enzymes such as α-amylase[76]. Similarly, Eucalyptus globosus leaf extracts reduce α-amylase activity in Eleusine coracana seeds, thereby inhibiting germination[77]. o-Cresol suppresses both protease and amylase activity in a dose- and time-dependent manner[78]. In oilseeds, inhibition of lipase by allelochemicals impedes lipid breakdown, leading to insufficient energy and carbon skeletons for germination[79]. Certain terpenoids can also bind to ribosomes, disrupting mRNA binding or tRNA-mediated amino acid transport, which inhibits protein synthesis and ultimately affects germination[80].

Germination demands substantial energy to support cell division and growth. Allelochemicals frequently target key steps in glycolysis and the respiratory chain, limiting aerobic respiration and ATP production. Sunflower (Helianthus annuus) extracts, for instance, inactivate isocitrate lyase, thereby suppressing germination[79]. Compounds such as cinnamic acid and pinene disrupt the mitochondrial electron transport chain, impairing electron transfer from NADH and FADH2 to oxygen. This uncouples oxidative phosphorylation, reduces ATP synthesis, and starves the seed of energy. Some allelochemicals also inhibit ATP synthase, preventing ADP phosphorylation and further compromising cellular energy supplies[81].

Additionally, allelochemicals can inhibit photosynthetic establishment in germinating seedlings by damaging chloroplast structure or inhibiting chlorophyll biosynthesis. Extracts of Artemisia argyi suppress chlorophyll synthesis in receiving plants[82], while Ageratina adenophora extracts containing camptothecin reduce chlorophyll content and impair seedling growth[83]. Phenolic acids, including caffeic, trans-cinnamic, p-coumaric, ferulic, gallic, and vanillic acids, downregulate key chlorophyll biosynthetic enzymes, such as protochlorophyllide reductase, leading to lower chlorophyll levels, reduced photosynthetic capacity, and compromised autotrophic growth after germination[84].

Effects on the cell membrane and the cell wall

-

Plant allelochemicals can disrupt seed germination by compromising the structural and functional integrity of the cell membrane and cell wall. These compounds often increase membrane permeability, leading to a loss of cellular homeostasis. Certain phenolic acids, for instance, can insert into the phospholipid bilayer, disturbing its ordered structure. This disruption impairs the membrane's capacity to regulate material exchange and transmit physiological signals, ultimately affecting water uptake, cell expansion, and the metabolic activation necessary for germination[85].

A key mechanism underlying membrane damage is oxidative stress. The oxidation of cellular macromolecules, particularly membrane lipids, induces lipid peroxidation, which causes membrane hyperpolarization followed by depolarization and ultimately leads to a complete loss of membrane integrity[86]. For example, treatment of white mustard (Sinapis alba) seeds with sunflower leaf extracts significantly increases electrolyte leakage, indicating severe membrane disruption and efflux of intracellular contents[87]. Additionally, some allelochemicals bind to membrane proteins such as nutrient transporters, inhibiting the uptake of essential compounds, including glucose and amino acids, thereby further suppressing seed germination and early seedling growth[88].

Allelochemicals also target the cell wall, which must be remodeled and loosened to permit radicle emergence. Some compounds inhibit cellulose synthase (CesA), reducing cellulose biosynthesis and resulting in mechanically weaker or abnormally thin cell walls that may rupture during germination[89]. Others interfere with wall-loosening enzymes, such as xyloglucan endotransglucosylases (XETs), which are critical for cell expansion[90]. By inhibiting these processes, allelochemicals prevent the necessary relaxation of the cell wall, restrict radicle and plumule growth, and ultimately block the completion of germination.

Inhibition of cell division and elongation

-

Certain allelochemicals disrupt seed germination by directly inhibiting cell division and elongation in embryonic tissues. Alkaloids such as vincristine and quinine interfere with mitosis, impairing both processes and preventing normal radicle and plumule development. Similarly, terpenoids from Larix principis-rupprechtii volatiles significantly inhibit radicle and hypocotyl elongation in its own seeds[91]. High concentrations of phenolic acids restrict radicle and hypocotyl growth in ginseng (Panax ginseng) seeds[92]. Other compounds, including organic acids like p-hydroxybenzoic acid and cinnamic acid, inhibit melon (Cucumis melo) seed radicle and hypocotyl growth at elevated doses[93]. Vanillin strongly suppresses radicle elongation in China fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) and causes toxicity to seedling tissues[94].

At the cellular level, essential oils from Dysphania ambrosioides induce chromosomal aberrations in broad bean (Vicia faba) root tip cells, disrupting DNA synthesis and inhibiting radicle growth[95]. Aqueous extracts from ginger stems and leaves also suppress radicle and hypocotyl growth in soybean and Allium fistulosum, with effects intensifying at higher concentrations[96]. Furthermore, monoterpenes released by Salvia leucophylla, including camphor, 1,8-cineole, α-pinene, β-pinene, and camphene, suppress cell proliferation in the radicle apical meristem, leading to significant inhibition of radicle growth in Brassica campestris[97].

Other possible mechanisms

-

Beyond the direct physiological disruptions described above, allelochemicals may also influence seed germination through less-explored mechanisms. Recent evidence indicates that certain phenolic acids can promote the formation of stress granules (SGs) in plant root cells, a process associated with reduced global translational activity[98]. This suggests that allelochemicals may suppress germination by impairing the translational machinery essential for early germination events. Furthermore, phenolic acids significantly influence soil microbial biomass and community structure[99], indicating that their inhibitory effects on germination could be partially mediated by indirect soil microbiological pathways. By altering the rhizosphere microbiome, these compounds may modify nutrient availability, induce pathogen activity, or modulate microbial-derived signaling molecules that regulate seed dormancy and germination.

Interactive and integrative mechanisms

-

The inhibitory effects of allelochemicals on seed germination involve multiple interconnected mechanisms that often operate synergistically. Among these, oxidative stress may serve as a central node integrating various allelopathic pathways. ROS play a dual role in seed physiology. At moderate levels, they promote dormancy release and germination by contributing to the mobilization of seed storage reserves and by directly interacting with cell wall polysaccharides to facilitate cell elongation[100]. However, excessive ROS accumulation (e.g., H2O2) induced by allelochemicals inflicts oxidative damage on macromolecules, disrupts cellular membranes and organelles, and ultimately limits the energy supply required for radicle emergence[87]. Furthermore, ROS act as signaling molecules that interact with hormonal pathways. For instance, H2O2 can regulate lipid mobilization during germination through the sulfenylation of key enzymes and promote ABA degradation via the activation of ABA-8'-hydroxylase[101]. Notably, ROS production in the endosperm is inhibited by ABA but promoted by GA and ethylene[102]. This crosstalk between oxidative stress and hormonal signaling forms a complex regulatory network that critically influences the seed's decision to germinate.

In conclusion, the mechanisms by which allelochemicals affect seed germination are not linear but form a highly interconnected network. Cellular damage, oxidative stress, metabolic interference, hormonal disruption, and genotoxicity do not operate in isolation but continuously influence and amplify each other. Future research, utilizing multi-omics approaches, is essential to further unravel these complex interactive networks under realistic environmental conditions.

-

Current research on the effects of plant allelochemicals on seed germination is constrained by several limitations, including a narrow selection of study subjects, insufficient diversity in the types and concentrations of compounds investigated, a lack of mechanistic depth, and limited applied research. Most existing studies focus on a limited number of models or economically important species, such as tomato, Glehnia littoralis, and Larix sibirica, with inadequate coverage across broader plant taxa. This narrow scope hinders a comprehensive understanding of allelopathic interactions within diverse ecosystems. Furthermore, research often centers on a small subset of well-known plant-derived molecules (e.g., certain phenolic acids or abscisic acid) tested at isolated concentrations, leaving the vast structural diversity of allelochemicals and their complex mixture effects largely unexplored. Mechanistically, there is a critical need to elucidate the precise pathways through which allelochemicals influence seed germination in the real world. Key priorities include clarifying their interactions with plant hormone signaling, effects on enzyme kinetics, and disruption of antioxidant defense systems, alongside systematic studies of interspecies variation in sensitivity.

Although allelopathy holds significant potential for applications in sustainable agriculture and ecosystem management, such as weed control, crop enhancement, and invasive species regulation, translational research remains underdeveloped. Future efforts should expand the taxonomic and chemical scope of studies, particularly by examining interactions between invasive and native species across different ecosystems. Systematic investigation into the effects of diverse allelochemical mixtures and concentrations on seed germination is essential to uncover their ecological significance and practical utility. Such foundational work will be crucial for developing novel agroecological technologies based on allelopathic principles.

Advanced analytical techniques driving mechanistic insights into allelochemicals

-

Research on plant allelochemicals faces several methodological challenges in extraction, isolation, and detection, including interference from complex matrices and difficulties in separating intricate sample compositions. Co-existing substances in soil or plant extracts can introduce significant interference, complicate separation, and potentially mask trace allelopathic signals. These issues necessitate the development of efficient pretreatment techniques, such as molecularly imprinted solid-phase extraction. Furthermore, allelochemicals often occur at low concentrations and are susceptible to adsorption or degradation during processing. In environmental samples, certain plant-derived small molecules may fall below instrumental detection limits (e.g., pg/mL levels), requiring enrichment strategies using nanomaterials or signal amplification. Finally, current methods often lack the capability for in situ, continuous monitoring, such as tracking the dynamic release of root exudates in real time.

Recent advances in analytical technology and interdisciplinary collaboration have substantially improved the sensitivity, throughput, and applicability of detection methods for plant small molecules. Traditional solvent extraction, based on the "like dissolves like" principle, is often inefficient, consumes large volumes of solvent, and risks degrading heat-labile components. In contrast, novel extraction techniques provide more efficient and environmentally friendly alternatives, for instance, ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE), microwave-assisted extraction (MAE), supercritical fluid extraction (SFE), pressurized liquid extraction (PLE), and solid-phase microextraction (SPME). These methods surpass conventional techniques in efficiency, selectivity, and sustainability. For example, optimized conditions (50% ethanol, solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:20, particle size 0.75 mm) have been used to efficiently extract total phenolics and anthocyanins from Aronia berries, demonstrating that soaking can be a simple yet effective polyphenol isolation method[103]. Future innovations in green solvents, intelligent coupled systems, and in situ extraction will further improve performance.

The separation and purification of plant allelochemicals, which typically form complex mixtures, are essential for deciphering their ecological functions and enabling practical applications. Traditional methods such as silica gel column chromatography and solvent partitioning are often slow (hours to days), require large solvent volumes, yield low recovery rates (< 70%), and may degrade thermosensitive compounds. They also struggle to resolve structurally similar molecules. Advanced techniques like ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC), and high-speed countercurrent chromatography (HSCCC) address these issues through miniaturized stationary phases (UPLC particle size < 2 μm) or solid-support-free operation (HSCCC), reducing separation time, increasing recovery, and minimizing solvent use[104,105]. When combined with AI-assisted optimization and integrated online detection, these methods offer superior resolution, efficiency, and sustainability for complex mixtures.

Emerging mass spectrometry platforms have revolutionized the discovery and study of plant allelochemicals. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) enhances the separation and detection speed of small molecules in complex matrices such as soil or plant extracts, allowing accurate quantification of trace compounds[106]. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) is well-suited for volatile plant metabolites (e.g., terpenes, aldehydes, ketones), while advanced ion sources like atmospheric-pressure chemical ionization (APCI) improve detection of thermally labile compounds[106,107]. New analytical strategies, such as molecular networking (MN) based on LC-MS/MS data and small molecule accurate recognition technology (SMART) using NMR, provide powerful tools for the targeted discovery of novel bioactive structures.

On another front, spectroscopic and imaging technologies are expanding spatial and temporal resolution in allelochemical research. Raman spectroscopy and surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) employ nanomaterials (e.g., gold or silver nanoparticles) to amplify signals, enabling near-single-molecule detection suitable for in situ analysis of surface secretions[108,109]. Mass spectrometry imaging (MSI), particularly when coupled with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI), visualizes the spatial distribution of small molecules within plant tissues or their diffusion patterns in soil[110−112]. Biosensors and microfluidic devices, such as electrochemical sensors incorporating molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) or aptamer-based recognition elements, allow specific detection of target compounds (e.g., ferulic acid). Microfluidic chips that integrate sample pretreatment and detection modules in portable setups are especially promising for real-time field monitoring of allelopathic interactions[113].

Future research on plant-derived small molecules is expected to progress along two key trajectories: (1) shifting from controlled laboratory analyses to in situ field monitoring systems; and (2) advancing from single-compound profiling to integrated multi-omics network analysis. The incorporation of nanotechnology, artificial intelligence, and high-resolution in situ imaging will make detection more efficient, intelligent, and ecologically relevant, providing critical technical support for sustainable agriculture and ecosystem restoration.

Harnessing allelopathic insights for germination management in sustainable agriculture

-

Plant allelochemicals have served as powerful phytochemical probes, fundamentally deepening our understanding of seed germination physiology. By observing the inhibitory or promotive effects of these diverse compounds, researchers have moved beyond a simplistic 'go/no-go' model of germination. The phenomenon of hormesis, where low doses of a typically inhibitory substance can stimulate germination, has been particularly illuminating[57]. It demonstrates that germination is not merely a passive process awaiting permissive conditions but an active, finely-tuned decision-making system that interprets chemical cues from the environment. These insights carry profound implications for both basic science and agricultural application, emphasizing that future germination research must consider multi-omics networks and the ecological context of chemical interactions. From an applied perspective, understanding how natural chemicals regulate germination opens avenues for developing novel strategies in seed priming, weed management, and crop protection. Furthermore, research on allelochemicals illuminate the sophisticated chemical interactions that underpin natural ecosystems, including bidirectional plant communication, compound synergy or antagonism, and microbially mediated indirect effects. Ultimately, allelochemical research teaches us that the secret to controlling germination lies in understanding the complex language of chemical ecology.

Plant allelochemicals are increasingly recognized as promising candidates for developing eco-friendly biopesticides, particularly herbicides. These naturally occurring compounds, derived from plants such as rice, poplar, and Paulownia, can significantly inhibit the germination and growth of various weed species, e.g., allelopathic rice accession PI312777 suppresses barnyard grass[12,13], while aqueous extracts from poplar leaves affect common weeds in wheat and maize fields[11]. However, their modes of action often involve multi-target mechanisms, including disruption of mitochondrial function, induction of oxidative stress, and interference with hormone signaling, which reduces the likelihood of weed resistance compared to single-target synthetic herbicides. Further research is needed to elucidate these mechanisms and optimize application methods.

Beyond direct application, allelochemicals offer broader agroecological utility. They can serve as lead compounds for synthesizing novel herbicides with optimized stability and selectivity, as exemplified by the derivation of glufosinate from a microbial phytotoxin[114]. Furthermore, the integration of allelopathic plants, through intercropping, cover cropping, or rotation, provides a sustainable weed management strategy. For instance, cultivating allelopathic varieties like rye or sorghum can naturally suppress weeds through root exudates and residue decomposition, reducing reliance on chemical inputs while enhancing ecosystem-based plant defense[115].

Despite their potential, several challenges must be addressed before the wide-scale adoption of allelochemical-based strategies becomes feasible. Key limitations include the rapid degradation of these compounds under field conditions, high extraction or synthesis costs, and the need for comprehensive environmental safety assessments. Future efforts should prioritize the development of encapsulated formulations to enhance persistence, the application of synthetic biology for cost-effective production, and rigorous evaluation of impacts on non-target organisms. To accurately assess ecological risks and optimize application strategies, future research must focus on direct measurement of in situ concentrations and account for critical environmental processes such as soil adsorption and microbial degradation. Advanced sensing technologies, such as gradient diffusion films (DGT) for passive sampling or optical sensors (e.g., tryptophan-like fluorescence sensors)[116], can provide high-resolution, real-time data on bioavailable concentrations in water and soil. It is equally essential to quantify environmental fate parameters, including adsorption-desorption kinetics that govern compound mobility and microbial degradation pathways (e.g., enzymatic transformations via decarboxylases or oxidases) that influence persistence and metabolite formation. Integrating these parameters into predictive models, which incorporate partitioning coefficients, degradation rate constants, and bioavailability modifiers, will enable more reliable extrapolation from laboratory results to field conditions. Furthermore, studies should examine seasonal and spatial variability in these processes to ensure model applicability across diverse ecosystems. Overall, interdisciplinary collaboration remains crucial to translating these natural solutions into reliable and sustainable agricultural tools.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31970344), Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LHZQN25C130001), the Henan Provincial Science and Technology Research Project (232102311150, 235200810037), and the Henan Academy of Sciences (240613011, 20253713001, 220913002).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design:Chen M, Chen XC, Wang ZY; data collection: Wang ZY, Yan KL, Zhang NC; draft manuscript preparation: Wang ZY, Yan KL, Chen M, Qin YM, Zhang NC. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Zhi-Yao Wang, Kai-Long Yan

- Supplementary Table S1 List of allelochemicals influencing seed germination.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Laboratory. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang ZY, Yan KL, Qin YM, Zhang NC, Chen XC, et al. 2025. Effects of allelochemicals from plants on seed germination. Seed Biology 4: e023 doi: 10.48130/seedbio-0025-0022

Effects of allelochemicals from plants on seed germination

- Received: 20 August 2025

- Revised: 25 September 2025

- Accepted: 24 October 2025

- Published online: 15 December 2025

Abstract: Seed germination is a pivotal stage in the plant life cycle, profoundly influenced by allelochemicals—biologically active compounds released by plants into the environment. These compounds can either suppress or stimulate germination, thereby shaping agricultural productivity and ecological dynamics. However, research on plant-derived allelochemicals faces significant challenges, including their structural diversity, low natural abundance, and methodological limitations in isolation/characterization. Furthermore, the precise mechanisms through which these compounds modulate seed germination are not yet well understood. Elucidating these processes is crucial for deciphering the chemical ecology of plant–plant interactions, optimizing agricultural practices, and guiding ecological restoration efforts. This review synthesizes current knowledge on the structural classes and natural sources of allelochemicals, their roles in germination regulation, emerging analytical techniques for their study, and their potential applications in sustainable agriculture.

-

Key words:

- Allelochemicals /

- Secondary metabolites /

- Seed germination /

- Allelopathy