-

Given the continuous growth of the global population and the increasing urgency of food demand, the rapid development of high-yielding and stress-resilient crop varieties has become a top priority for plant breeding. Among the available strategies, haploid breeding has emerged as a powerful tool for shortening breeding cycles and enhancing the efficiency of selection by enabling rapid genome-wide homozygosity. Since Harland’s seminal identification of the first haploid angiosperm in a sea island cotton variant in 1920[1], researchers have made substantial progress in elucidating the biological basis of haploid induction (HI) and translating this knowledge into breeding practices. Nevertheless, despite over a century of research, the molecular mechanisms underlying HI remain only partially understood. Deciphering these mechanisms is not only of fundamental importance for understanding plants' reproductive biology but is also critical for translational applications. On a basic research level, insights into haploid formation will enrich our theoretical framework of plant development. From an applied perspective, the discovery of novel and efficient HI genes could overcome existing technical bottlenecks, establish universal HI systems across diverse crop species, and even enable the creation of apomictic crops. Such advances would directly accelerate breeding pipelines and support the iterative improvement of major crops, thereby contributing to global food security and resilience to climate change.

Haploids are individuals whose somatic cells contain the same number of chromosomes as the gametes of the species. The haploid phenomenon is widely distributed among angiosperms[1]. By doubling haploid chromosomes, breeders have developed haploid breeding technology, which allows the direct production of completely homozygous individuals within a single generation[2]. This technology has become a cornerstone of modern crop breeding. Producing homozygous inbred lines is a prerequisite for developing hybrid varieties. Conventional breeding typically requires six to eight generations to generate genetically uniform lines, followed by three or four generations of hybrid testing and field evaluation, a process that spans 6–10 years[3]. In contrast, haploid breeding significantly shortens this timeline: HI systems generate haploid embryos or plants, which are then doubled to create fully homozygous doubled haploids (DH). This reduces the development of inbred parental lines to just one or two generations[4]. Furthermore, combining haploid breeding with nonreduced gamete technology has the potential to enable apomixis, permitting clonal propagation of hybrids, ensuring trait fixation over generations, and drastically reducing seed production costs[5].

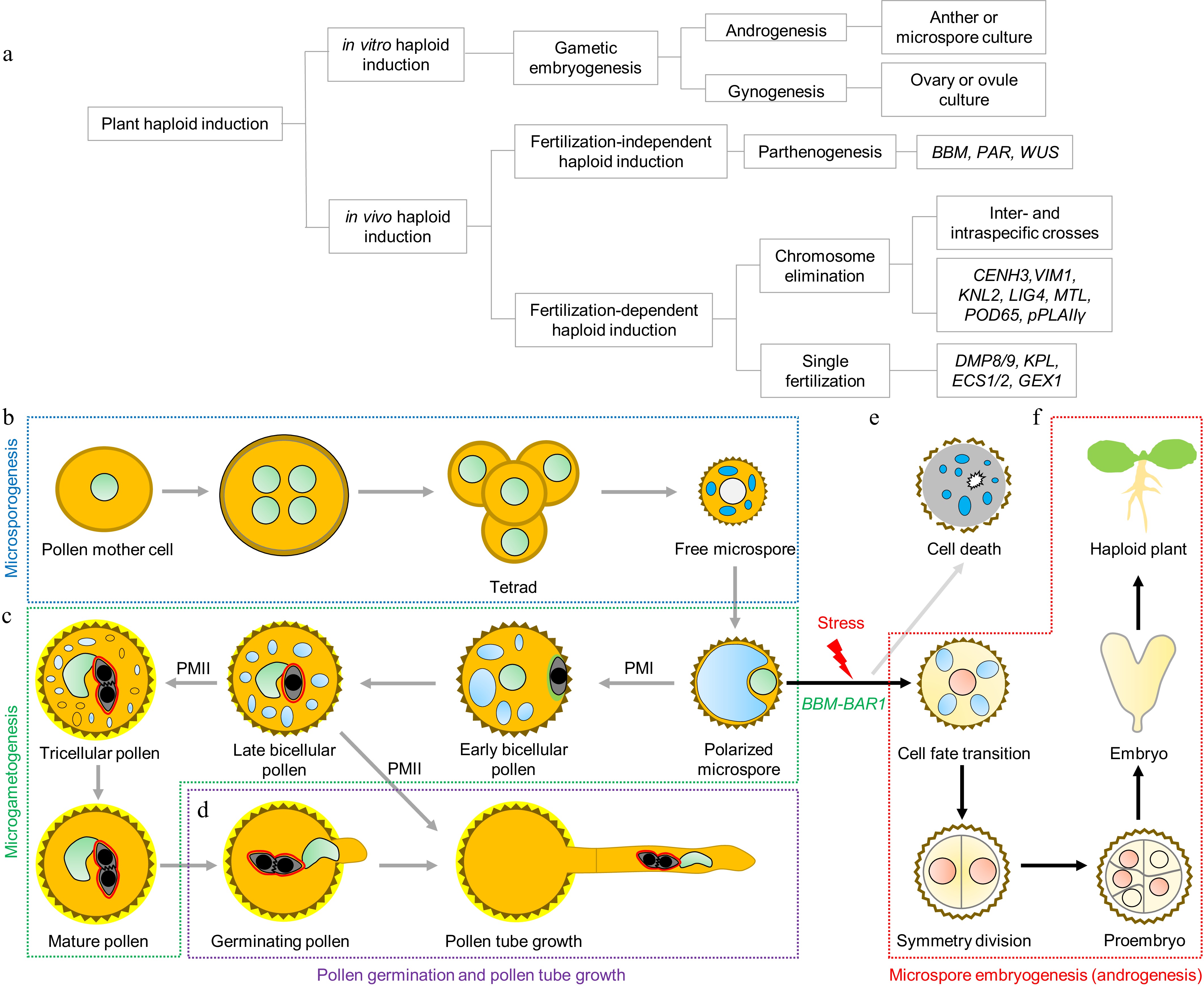

The efficient production of haploids is the central step of haploid breeding technology. Although some angiosperms naturally produce haploid offspring via apogamy or parthenogenesis, spontaneous HI rates are extremely low, rendering them impractical for large-scale breeding. To overcome this limitation, researchers have developed several strategies to increase the HI rate. Current HI approaches fall into two major categories: In vivo HI and in vitro HI (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Haploid induction (HI) strategies and BBM-BAR1-mediated androgenesis. (a) Plant HI methods and classification. Plant HI approaches are broadly divided into in vivo and in vitro strategies. In vivo HI typically relies on haploid inducer lines generated through genetic manipulation or mutation of key genes, triggering the development of haploid embryos after fertilization. This category includes (i) parthenogenesis-based methods (via ectopic expression of transcription factors such as BABY BOOM [BBM], PARTHENOGENESIS [PAR], or WUSCHEL [WUS]), (ii) chromosome elimination-based methods (via inter- or intraspecific crosses or gene knockout), and (iii) single fertilization-based methods (via gene knockout). In vitro HI employs tissue culture to induce embryogenesis from gametophytic cells, including anther or microspore culture (androgenesis) and ovary or ovule culture (gynogenesis). (b) Microsporogenesis. Pollen mother cells undergo meiosis to form tetrads of four haploid microspores that are synchronously released. (c) Microgametogenesis. Free microspores develop into polarized microspores and undergo PM I to produce a large vegetative cell and a smaller generative cell that subsequently undergoes PM II to yield two sperm cells. (d) Pollen germination and tube growth. (e) Microspores that fail to transition to the proper developmental fate undergo programmed cell death. (f) Androgenesis. Under specific stress conditions, a subset of microspores can be reprogrammed toward embryogenesis, forming haploid embryos, depending on the BBM–BAR1 module.

In vivo HI exploits natural reproductive processes to trigger egg-cell-derived embryogenesis, resulting in spontaneous haploid formation within the plant, also referred to as in situ gynogenesis[6]. This approach is divided into fertilization-independent and fertilization-dependent modes, both of which usually require fertilization of the central cell to trigger the endosperm's development (Fig. 1a).

Fertilization-independent HI bypasses egg fertilization, with the egg cell autonomously initiating embryogenesis via parthenogenesis. This can be achieved by ectopically expressing embryogenic transcription factors in the egg cell[7]. Parthenogenesis, which is observed in numerous plant and animal species[8], is an effective route to generate maternal haploids. Artificial parthenogenesis can be induced by radiation, chemicals, distant hybridization, or by using genetic parthenogenesis- inducing genes. The latter is currently the most robust approach, relying on the identification and targeted expression of natural parthenogenesis genes such as BBM[7], PAR[9], and WUS[10] in egg cells to trigger fertilization-independent embryo development (Fig. 1a).

Fertilization-dependent HI, by contrast, requires pollination with haploid inducer plants. It operates via two main mechanisms: (1) Chromosome elimination, where one parental genome is selectively lost during early embryogenesis, producing haploids[11], and (2) single fertilization, where sperm–egg fusion is incomplete, preventing zygote formation, while central cell fertilization proceeds normally, stimulating haploid embryogenesis[12]. Chromosome elimination can occur via inter- or intraspecific crosses[13] or through targeted manipulation of HI genes such as CENH3[14], KNL2[15], MTL/PLA1/NLD[16−18], POD65[19], and pPLAIIγ[20] (Fig. 1a). Single fertilization-based HI depends on genes like DMP8/9[13], KPL[21], ECS1/2[12], and GEX1[22] (Fig. 1a). Both strategies rely on normal endosperm development to ensure haploid seeds' viability.

In vitro HI harnesses the developmental plasticity of gametophytic cells to reprogram them into embryogenic tissues, a process collectively known as gametic embryogenesis[23]. Depending on the explant source, in vitro HI can be classified as gynogenesis (using ovaries or ovules) or androgenesis (using anthers or microspores) (Fig. 1a). Androgenesis is generally preferred because of the ease of obtaining microspores and their rapid regeneration potential. Successful androgenesis-based HI has been reported in several crops, including maize[24], barley[25], wheat[26], rice[27], tobacco[28], and rapeseed[29]. Tobacco and rapeseed, in particular, have served as model systems to explore the molecular and cellular basis of microspore reprogramming.

In angiosperms, male gametophytes (pollen grains) are formed in two phases: Microsporogenesis and microgametogenesis. During microsporogenesis, diploid microsporocytes undergo meiosis to form tetrads of haploid microspores, which are then released following callose wall degradation (Fig. 1b). In microgametogenesis, microspores enlarge, polarize, and undergo asymmetric pollen mitosis I (PM I) to form a vegetative and a generative cell. The generative cell migrates into the vegetative cytoplasm, forming the male germ unit[30], and subsequently undergoes pollen mitosis II (PM II) to generate two sperm cells (Fig. 1c). Subsequently, the pollen undergoes dehydration, which is important for its survival during release and dispersal[31]. The division of the generative cell into two sperm cells via PM II occurs within the pollen grains in approximately 30% of angiosperm species, including Arabidopsis thaliana, whereas in the remaining angiosperm species, this process takes place within the pollen tube; thus, mature pollen grains may be released in either a two-celled (a vegetative cell and an undivided generative cell) or three-celled (a vegetative cell and two sperm cells) state[31] (Fig. 1c, d).

Under in vitro stress conditions, however, a subset of microspores can switch from the gametophytic pathway to an embryogenic pathway, acquiring totipotency and giving rise to haploid embryos, a process known as androgenesis (or microspore embryogenesis)[32] (Fig. 1e, f). Androgenesis is an invaluable tool for producing haploids and, following chromosome doubling, DH lines within a single generation. It is also an excellent model for studying cellular reprogramming. Despite decades of research since the first report of stress-induced androgenesis in the 1960s[33], the molecular triggers governing this developmental switch remain incompletely defined, and efficiency remains low in many crop species.

A recent breakthrough by Shi and colleagues identified a conserved BBM–BAR1 regulatory module capable of reprogramming microspores into embryos without external stress (Fig. 1f)[34]. Comparative transcriptomics revealed that NtBBM1 and NtBBM2 are expressed not only in zygotic embryos but also during the early stress response in microspores. Microspore-specific expression of NtBBM1/2 (NtBBM1/2-me) in tobacco induced symmetric division—a hallmark of embryogenesis—and led to the formation of embryo-like structures even in the absence of stress[34]. Under in vitro stress-induced conditions, NtBBM1/2-me microspores showed significantly enhanced androgenesis efficiency.

However, the embryonic development of NtBBM1/2-me microspores was arrested within intact anthers, likely because of insufficient nutritional support from the anther tissues for further embryo growth. To overcome this limitation, Shi and colleagues cultured NtBBM1/2-me microspores in vitro without stress induction. They found that NtBBM1/2-me microspores produced significantly more embryos, 86.7% of which matured into haploid plants. Conversely, Ntbbm1–Ntbbm2 double mutants exhibited severely reduced androgenesis frequency under stress conditions, confirming that BBM is required for stress-induced microspore reprogramming.

This approach was successfully translated to rice using a microspore-preferred promoter, where the expression of OsBBM1 triggered androgenesis in vivo and in vitro. Furthermore, overexpression of NtBBM1/2 in the leaves also triggered embryo-like structures, which is consistent with the conventional effect of BBM in somatic embryogenesis[35]. Cross-species expression experiments using BnBBM1 from Brassica napus also induced androgenesis in tobacco, indicating broad conservation of function.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analyses identified BAR1, a basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) transcription factor, as a direct BBM target. Ectopic expression of BAR1 in the microspores phenocopied the overexpression of BBM, underscoring its key role in BBM-mediated reprogramming. Moreover, BBM proteins from rice and soybean also bind to the promoters of the BAR1 in each species, suggesting conservation of the BBM–BAR1 module[34].

These findings position the BBM–BAR1 module as a versatile and powerful tool for HI, offering a stress-free and genetically encoded approach to triggering androgenesis. Beyond its practical value for accelerating breeding pipelines, this discovery provides a framework to study microspores' totipotency, transcriptional reprogramming, and the balance between proliferation and differentiation. BBM’s conserved roles across species, such as in zygotic embryogenesis, microspore embryogenesis, and even somatic embryogenesis, underscore its central function as a developmental switch that activates proliferation and morphogenesis while repressing differentiation programs.

This work raises several new questions. First, the upstream signaling network that activates BBM in response to stress remains unknown and represents a key knowledge gap. Second, the applicability of BBM–BAR1-based HI strategies in self-incompatible species such as Brassica vegetables warrants investigation, as it could overcome barriers to breeding. Finally, broader deployment of BBM-mediated HI will require the development of alternative delivery platforms, such as protein/RNA transfection into microspores or chemical activators of endogenous BBM pathways, to bypass reliance on stable transformation, particularly for recalcitrant crops. These innovations could dramatically accelerate the generation of homozygous lines and enhance compliance with biosafety standards for agricultural use.

HTML

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32425009, 32170343, 32500293), the CAS Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research (Grant No. YSBR-078), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFF1003500), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFF1001504), and Biological Breeding – National Science and Technology Major Project (2024ZD04078).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: draft manuscript preparation: Chen SY; manuscript revision: Li HJ, Yang WC. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Laboratory. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

| Chen SY, Li HJ, Yang WC. 2025. How microspores are reprogrammed into embryos. Seed Biology 4: e021 doi: 10.48130/seedbio-0025-0026 |