-

The domestication and ecological expansion of rice (Oryza sativa L.) represent a landmark event in the evolutionary history of agriculture. Cultivated rice originated from wild rice populations descended from Oryza rufipogon Griff., a perennial species native to tropical and subtropical regions, and gradually spread to Southeast and South Asia through continuous human selection and adaptation to local environmental conditions[1]. Over time, this close interaction between humans and the environment has shaped a globally distributed cropping system, characterized by strong adaptability across diverse climatic regions and responsiveness to varying photoperiods[2,3]. Central to this broad adaptability is rice's ability to finely coordinate environmental cues, particularly photoperiod and temperature cues, through genetic reprogramming of heading date regulation. This regulatory flexibility has been pivotal in enabling rice to shift from single to multiple cropping systems and to expand from tropical to temperate cultivation zones[4−6].

As rice spread to regions with different latitudes and climates, it evolved region-specific traits that enhanced flexibility in heading date and developmental rhythms. Among these traits, the regulation of heading date played a central role in enabling ecological adaptation. Key photoperiod-responsive genes, including Hd1, Ghd7, DTH8, and Ehd1, experienced genetic changes such as mutations, loss-of-function events, and alterations in cis-regulatory changes during rice's geographic expansion[7,8]. These modifications gave rise to diverse photoperiodic response types across different rice lineages. Although the individual functions of these flowering-related genes have been extensively studied, a comprehensive understanding of how they integrate environmental signals to shape rice adaptation remains incomplete. It is still unclear which regulatory pathways were preferentially conserved or modified through the processes of domestication and breeding. Furthermore, modern breeding systems continue to rely on a narrow pool of elite cultivars. Modern breeding relies heavily on elite cultivars with limited environmental flexibility, leaving vast diversity in global germplasm collections untapped.

One of the most pressing challenges in rice improvement is the disconnect between the growing knowledge of adaptive traits, the discovery of key alleles, and their effective integration into breeding practices. Despite the global collection of over 780,000 rice accessions[9], only a small subset has been thoroughly characterized or incorporated into breeding pipelines, leaving a wealth of valuable traits unexploited in landraces and wild relatives underutilized[10]. At the same time, achieving stable expression of heading date under multifactorial environmental stress continues to be a critical bottleneck for achieving yield reliability, particularly in high-latitude and environmentally fragile regions. Addressing this issue will depend on deeper insight into the regulatory flexibility of domestication-associated networks, as well as on the ability to rewire and precisely design these pathways for enhanced environmental resilience.

To address these challenges, this review is organized around a framework of environmental signal perception, genetic regulatory response, and germplasm evolution. This structure enables a systematic exploration of the genetic architecture, evolutionary trajectories, and ecological adaptations underlying the rice flowering network. The objective is to identify ecologically significant alleles associated with heading date and to explore strategies for enhancing adaptation in increasingly complex environmental conditions. This review is structured into four main sections: (1) The domestication history and adaptive expansion of rice; (2) Key molecular pathways regulating flowering in response to photoperiod; (3) Genetic mechanisms supporting multi-regional adaptation; and (4) Future directions in germplasm development and intelligent breeding. By elucidating both the genetic basis and resource-level mechanisms that underlie rice's environmental adaptability, this review aims to provide theoretical insights and strategic guidance for the development of climate-resilient rice breeding systems.

-

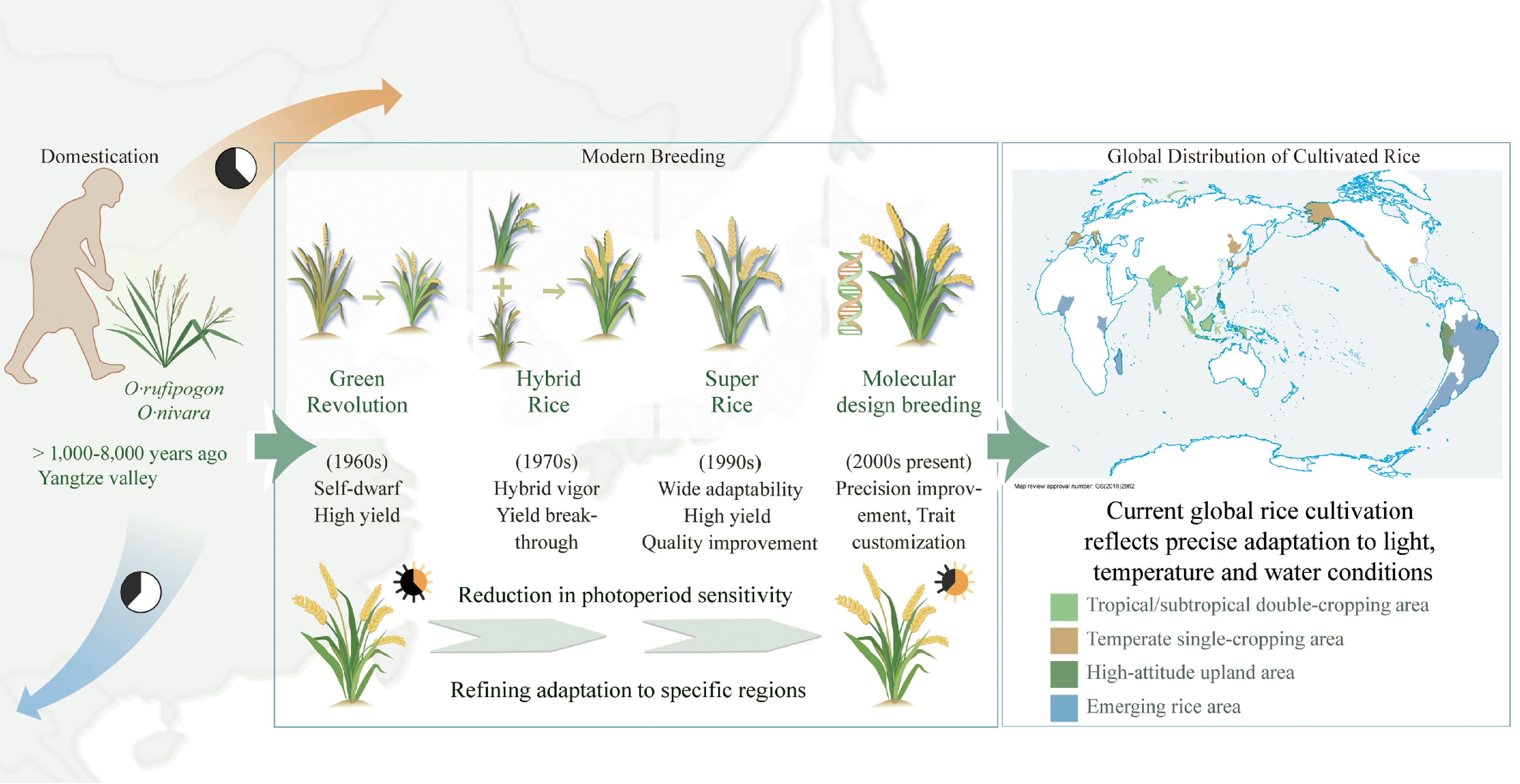

The broad ecological adaptability of rice is not a product of chance, but rather the result of a complex evolutionary trajectory shaped by both natural selection and human influence, spanning from its wild origins to modern genetic improvement[11]. This evolutionary journey offers critical insights into how photoperiod sensitivity, heading date regulation, and spatial distribution have been reshaped throughout the processes of domestication and adaptation (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

From natural selection to artificial breeding: evolutionary adaptation and global expansion of rice. Rice has evolved from its wild progenitors (O. rufipogon and O. nivara) through successive breeding phases, including the Green Revolution (semi-dwarf, high yield), hybrid rice (heterosis utilization), super rice (yield and quality improvement), and molecular design breeding (trait-level precision). This evolutionary trajectory reflects a gradual reduction in photoperiod sensitivity and enhanced regional adaptability. The map illustrates current global rice-growing regions, including tropical and subtropical double-cropping, temperate single-cropping, high-altitude upland, and emerging areas, demonstrating rice's precise ecological adaptation to light, temperature, and water conditions.

Current archaeological and genetic evidence suggests that rice was domesticated in the subtropical monsoon regions of southeastern China, where its wild progenitors, O. rufipogon and O. nivara, are distributed across East and Southeast Asia. Phytolith analysis and radiocarbon dating indicate that rice cultivation began in the middle and lower Yangtze River basin between 12,000 and 9,000 years ago. The Shangshan site in Zhejiang, dated to ~9,400 before present (BP), provides compelling evidence for the onset of domestication during the early Holocene. This region, at ~31.8° N, served as the center of domestication and the divergence point for the indica and japonica subspecies. It also functioned as a key transitional zone for the north-south dispersal of rice[1,12]. According to the single-origin hypothesis, japonica rice was first domesticated in China. It later migrated southward and hybridized with local wild rice populations, giving rise to the indica subspecies[13,14]. This adaptive transition, driven by gene flow and the co-evolution of photoperiodic regulatory networks, facilitated the rapid ecological expansion and geographic spread of rice.

As agricultural societies developed, rice cultivation systems matured and expanded beyond their original center of domestication. From the Yangtze River basin, rice spread northward into the Huang-Huai Plain and temperate Northeast Asia, and southward into the tropical regions of Southeast and South Asia[15]. Throughout this expansion, rice underwent adaptive differentiation in response to a wide range of ecological pressures. In hot and humid tropical-subtropical regions, indica ecotypes predominated and exhibited strong photoperiod sensitivity. In contrast, japonica varieties in temperate climates developed early maturity, cold tolerance, and reduced sensitivity to photoperiod. This ecological divergence between indica and japonica reflects both natural adaptation to environmental selection and the establishment of a genetic foundation for the subsequent evolution of heading date regulatory networks.

At the same time, human activity played a significant role in shaping rice adaptation. As agricultural systems diversified, irrigation technologies improved, and cropping calendars evolved, rice cultivation expanded into a variety of marginal environments, including the Yunnan Plateau, the Himalayan foothills, the arid regions of northern China, and coastal saline zones. Over time, the dynamic interplay between localized farming practices and natural selection gave rise to a wide array of landraces, each exhibiting unique ecological adaptations. Many traditional landraces such as Kasalath, Nagina 22 (N22), and Kinandang Patong (KP) harbour rich variation for photoperiod sensitivity and abiotic stress tolerance, and thus constitute a crucial reservoir of adaptive germplasm for modern rice breeding[16].

Since the twentieth century, rice improvement has advanced rapidly, progressing from the semi-dwarf, high-yielding IR8 of the Green Revolution to widely adopted hybrid rice such as Shanyou 63, and more recently to super rice and molecular design breeding[17−19]. By stacking favorable alleles, breeders have reconfigured photoperiod and heading-date regulatory networks, which have enabled elite cultivars represented by Zhongkefa 5 (ZKF5) to perform across both early-season environments in southern China and mid-season temperate climates in the northeast[20].

The combined effects of long-term natural evolution and modern technological innovation have collectively shaped the current global landscape of rice cultivation. Today, rice-growing regions can be broadly classified into four major agroecological systems: (1) tropical and subtropical double-cropping zones (e.g., Southeast Asia, southern China); (2) temperate single-cropping zones (e.g., Northeastern China, Japan); (3) high-altitude mountain zones (e.g., Yunnan, Nepal); and (4) newly expanding rice-growing areas (e.g., parts of Africa and South America)[21]. Each of these agroecological zones imposes distinct requirements on rice in terms of adaptation to light, temperature, and water availability. Collectively, they provide the ecological foundation for rice's transition from a regionally domesticated crop into a globally cultivated staple.

In summary, rice adaptation is not a single historical event but a continuous evolutionary process that has unfolded over millennia. From its initial domestication and early diversification into regional landraces to the widespread adoption of modern breeding strategies, rice has developed a multi-layered adaptation system. This system integrates molecular regulation, population structure, and agronomic practices. To understand how rice precisely responds to photoperiod and other environmental signals, it is essential to begin with its most critical developmental transition: heading date. This requires dissecting the underlying genetic networks and evolutionary pathways that regulate this process. The following section will focus on this central aspect of rice adaptation.

-

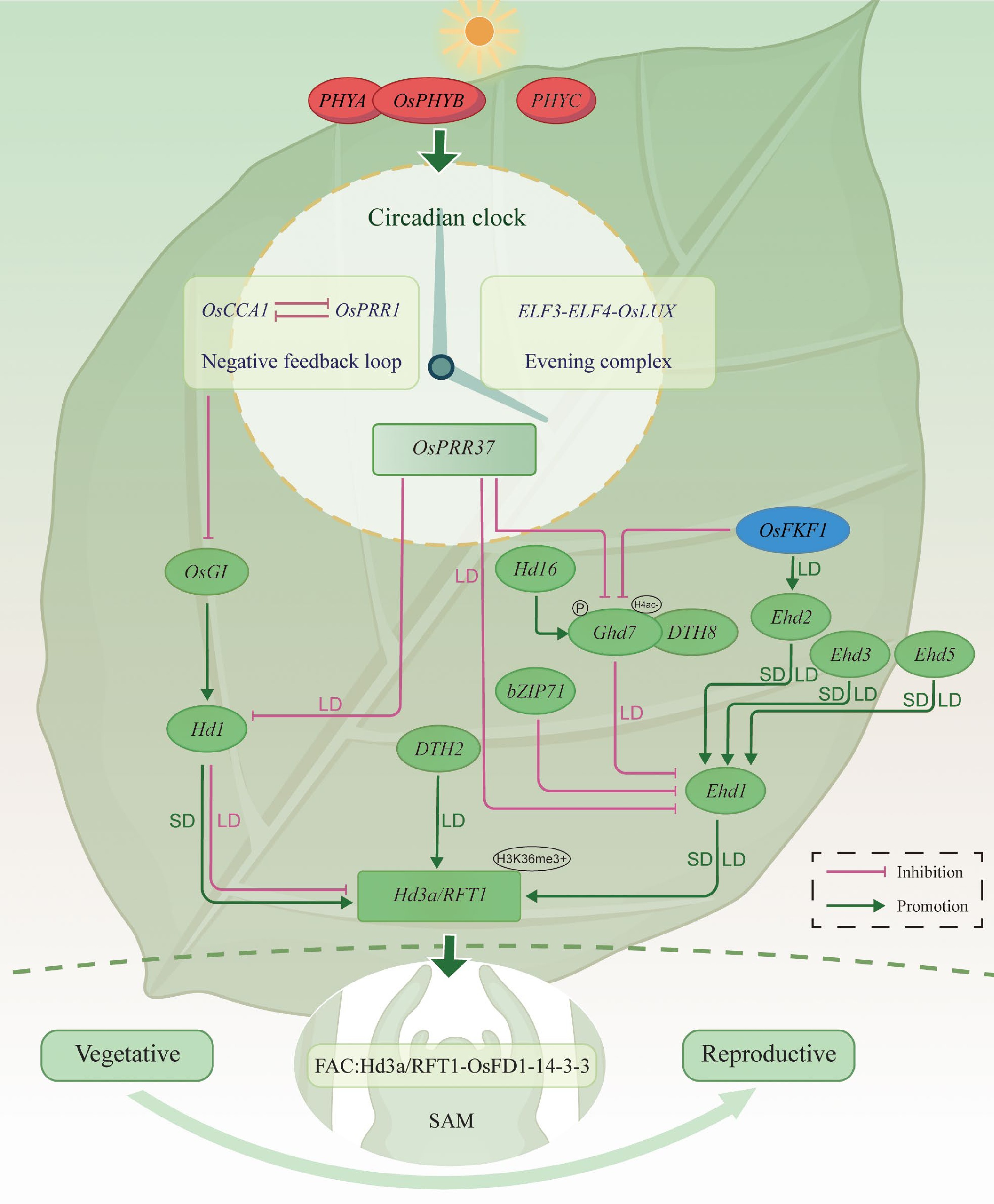

Flowering marks the transition from vegetative growth to the reproductive phase and represents a critical stage in the plant life cycle. In rice, a typical short-day plant, the photoperiod sensing system has evolved into a complex molecular network that enables precise seasonal regulation of flowering. Rice perceives day length through multiple photoreceptors. Among these, the phytochrome family, including Phytochrome A (PHYA), Phytochrome B (OsPHYB), and Phytochrome C (PHYC), senses red and far-red light. PHYB serves as the primary red-light receptor and regulates Hd1 and Hd3a, thereby acting as a key suppressor of flowering under long-day conditions[22]. PHYA and PHYC provide compensation or synergistic regulation in specific contexts[23]. In addition, FLAVIN-BINDING, KELCH REPEAT, F-BOX 1 (OsFKF1), a blue-light-responsive F-box protein containing a LOV (Light, Oxygen, or Voltage) domain, is regulated by the circadian clock. It promotes flowering by upregulating Early heading date 2 (Ehd2) and repressing Ghd7, which leads to activation of Ehd1 and subsequent induction of the florigen genes Hd3a and RFT1. Under long-day conditions, this OsFKF1 to Ehd2 branch provides a daylength-sensitive route to elevate Ehd1, thereby linking photoperiod sensing with circadian control[24].

The circadian system functions as a 'temporal decoder' of daylength, translating external light cues into internal rhythmic patterns through a series of interconnected transcriptional feedback loops[25,26]. In rice, CIRCADIAN CLOCK ASSOCIATED1 (OsCCA1, OsLHY) and PSEUDO-RESPONSE REGULATOR 1 (OsPRR1, OsTOC1) form a central negative feedback loop: OsCCA1 peaks at dawn and represses PRR1, while PRR1 accumulates during the day, and, in turn, represses OsCCA1, establishing a self-sustaining oscillatory circuit[27]. The ELF3-ELF4-OsLUX complex constitutes a key nighttime module of the rice circadian clock. This complex represses rhythm-associated genes such as Gigantea (OsGI), aligning environmental signals with flowering regulation and coordinating daily growth rhythms[25,28−30]. Functionally, this nighttime module complements the daytime OsCCA1-PRR1 loop to form an integrated and temporally balanced circadian system[31]. Pseudo-Response Regulator37 (OsPRR37, DTH7, Ghd7.1, Hd2) acts as a downstream output of the circadian rhythm, with peak expression occurring in the late photoperiod. Under long-day conditions, OsPRR37 represses Ehd1, thereby inhibiting the florigen genes Hd3a and RFT1, ultimately delaying flowering initiation. Under long-day conditions, OsPRR37 collaborates with other long-day repressors to reduce Ehd1 expression, which in turn lowers Hd3a and RFT1 and delays the onset of flowering[32,33]. Another key component, OsGI, is rhythmically expressed under circadian control and responds to both daylength and PHYA-mediated light signaling[27]. It contributes to flowering through the Hd1-Hd3a pathway, transmitting circadian phase information into Hd1's bifunctional output, namely activation under short-day and repression under long-day, thereby integrating circadian, photoperiod, and floral induction cues[34].

Rice heading date is primarily governed by two evolutionarily conserved and functionally coordinated core pathways: the OsGI-Hd1-Hd3a/RFT1 pathway and the Ghd7-Ehd1-Hd3a/RFT1 pathway[35−37]. These two photoperiod response mechanisms function independently but integrate at the point of florigen activation to regulate flowering. The OsGI-Hd1-Hd3a/RFT1 cascade is considered a functional analogue of the classical CONSTANS (CO)–FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) module in Arabidopsis[35]. Under short-day conditions, OsGI promotes the expression of Hd1, which in turn activates Hd3a by directly binding to its promoter, thereby inducing flowering. In contrast, under long-day conditions, Hd1 acts as a repressor of Hd3a, delaying the flowering process. At the same time, several long-day repressors, including Ghd7, OsPRR37 (DTH7), and DTH8, converge on Ehd1 and on Hd3a to postpone heading under long-day conditions, whereas DTH2 provides a counteracting branch that promotes the Ehd1 to Hd3a/RFT1 route in long-day conditions. This pattern illustrates the bifunctional nature of Hd1 as a central molecular switch in the rice photoperiod response[38].

Hd3a and RFT1 are essential florigen genes expressed in the leaves and transported through the phloem to the shoot apical meristem, where they interact with 14-3-3 proteins and OsFD1 (OsbZIP77) to form the Florigen Activation Complex (FAC). This protein interaction complex converts leaf-borne florigen into the activation of meristem identity genes at the shoot apex, initiating the transition from vegetative to reproductive development[39,40]. Hd3a functions predominantly under short-day conditions, while RFT1 compensates for its role under long-day conditions[41−43]. Field observations indicate that Hd3a shows a short-day bias, whereas RFT1 is more permissive in long-day conditions, and chromatin context further tunes their expression. Positioned at the convergence point of the OsGI-Hd1 and Ghd7-Ehd1 pathways, Hd3a and RFT1 serve as terminal integrators within the rice photoperiodic flowering network[44].

The Ghd7-Ehd1-Hd3a/RFT1 pathway, operating in parallel, is a rice-specific and non-canonical regulatory route essential for adaptation to temperate regions, especially in japonica cultivars. Ehd1 serves as a central floral inducer, translating photoperiod signals into flowering by directly activating the florigen genes Hd3a and RFT1[45]. Distinct from the OsGI-Hd1-Hd3a cascade, Ehd1 operates independently and remains functional even in the absence of Hd1, highlighting its evolutionary importance and breeding potential[43]. As a central integrative hub, Ehd1 is positively regulated by upstream activators such as Ehd2, Early heading date 3 (Ehd3), and Early heading date 5 (Ehd5)[27,38,43], while it is negatively regulated by repressors including Ghd7, OsLFL1 (B3 domain transcription factor), and bZIP71 (bZIP transcription factor)[46−48]. In long-day backgrounds, Ghd7 is reinforced at the chromatin level, where reduced H4 acetylation at the Ghd7 locus raises the repression threshold acting on the Ehd1 to Hd3a/RFT1 axis. In contrast, activating H3K36 methylation at Ehd1, Hd3a, and RFT1 is associated with higher transcription when day length is permissive.

Additional accessory genes contribute regulatory depth and functional flexibility to the rice photoperiodic flowering network. DTH8 and OsPRR37 can form protein complexes with Ghd7 to enhance repression of Ehd1 transcription, thereby amplifying the inhibitory effect of long-day conditions on flowering initiation[37]. Heading date 16 (Hd16), which encodes a Casein Kinase I (CKI), reinforces Ghd7 activity through phosphorylation, providing a post-translational layer that strengthens long-day repression[34]. Days to heading 2 (DTH2) plays a compensatory role by directly activating Hd3a when Ehd1 is suppressed, particularly under stress conditions[49]. CO-like gene 16 (COL16) functions as a signal integrator for photoperiod and temperature cues; under suboptimal conditions such as elevated temperature, it promotes Ghd7 expression, which in turn represses Ehd1 and the downstream florigen genes[50].

Together, these regulatory interactions form a multilayered flowering network that integrates light perception, circadian rhythms, and floral decision-making modules (Fig. 2). This intricate architecture ensures robust control of heading date in response to environmental cues such as photoperiod and temperature, thereby providing a molecular foundation for ecological adaptation across diverse rice-growing regions. However, these regulatory pathways represent only the baseline of adaptive evolution. The successful expansion of rice from short-day tropical environments to long-day temperate and high-latitude regions has depended largely on natural variation in key heading date genes, as well as their accumulation, recombination, and selective fixation within populations[51]. The following section will explore how functional variation in these core regulators has driven the adaptive diversification and geographic spread of rice.

Figure 2.

Integrated regulatory network linking light signaling, circadian rhythm, and photoperiodic flowering in rice. Photoreceptors (PHYA, OsPHYB, PHYC) entrain the circadian clock (the OsCCA1-OsPRR1 negative loop and the ELF3-ELF4-OsLUX evening complex), which routes signals into the OsGI-Hd1-Hd3a/RFT1 and Ghd7-Ehd1-Hd3a/RFT1 axes. Small SD/LD labels on edges indicate predominant effects under short-day (SD) or long-day (LD): Hd1 activates Hd3a/RFT1 in SD but represses in LD; Ghd7, OsPRR37/DTH7, and DTH8 predominantly repress Ehd1 in LD; DTH2 promotes Hd3a/RFT1 under LD; Ehd2/3/5 promote Ehd1. Protein-protein interactions are overlaid, including the florigen activation complex (FAC; Hd3a/RFT1-14-3-3-OsFD1) at the SAM. Protein post-translational modification control is indicated by Hd16/CKI-dependent phosphorylation that potentiates Ghd7 repression under LD. Chromatin badges mark H3K36me3+ (activation) at Hd3a/RFT1 and H4ac− (deacetylation/raised repression threshold) at Ghd7. Green arrows denote promotion; magenta blunt lines denote repression. (Hd3a is SD-biased, whereas RFT1 is more LD-permissive).

-

The wild ancestor of cultivated rice, O. rufipogon, originated in tropical to subtropical regions characterized by short-day environments, where flowering was strictly regulated by photoperiodic cues[8,52]. Around 10,000 years ago, domestication began in the Yangtze River basin[12,53], accompanied by a series of functional and loss-of-function mutations in key heading date genes[46,54−57]. Through successive mutations, cultivated rice lost its strict dependence on tropical photoperiods, facilitating its spread into higher-latitude regions[1].

Strategy I: promoting early flowering through glorigen pathways

-

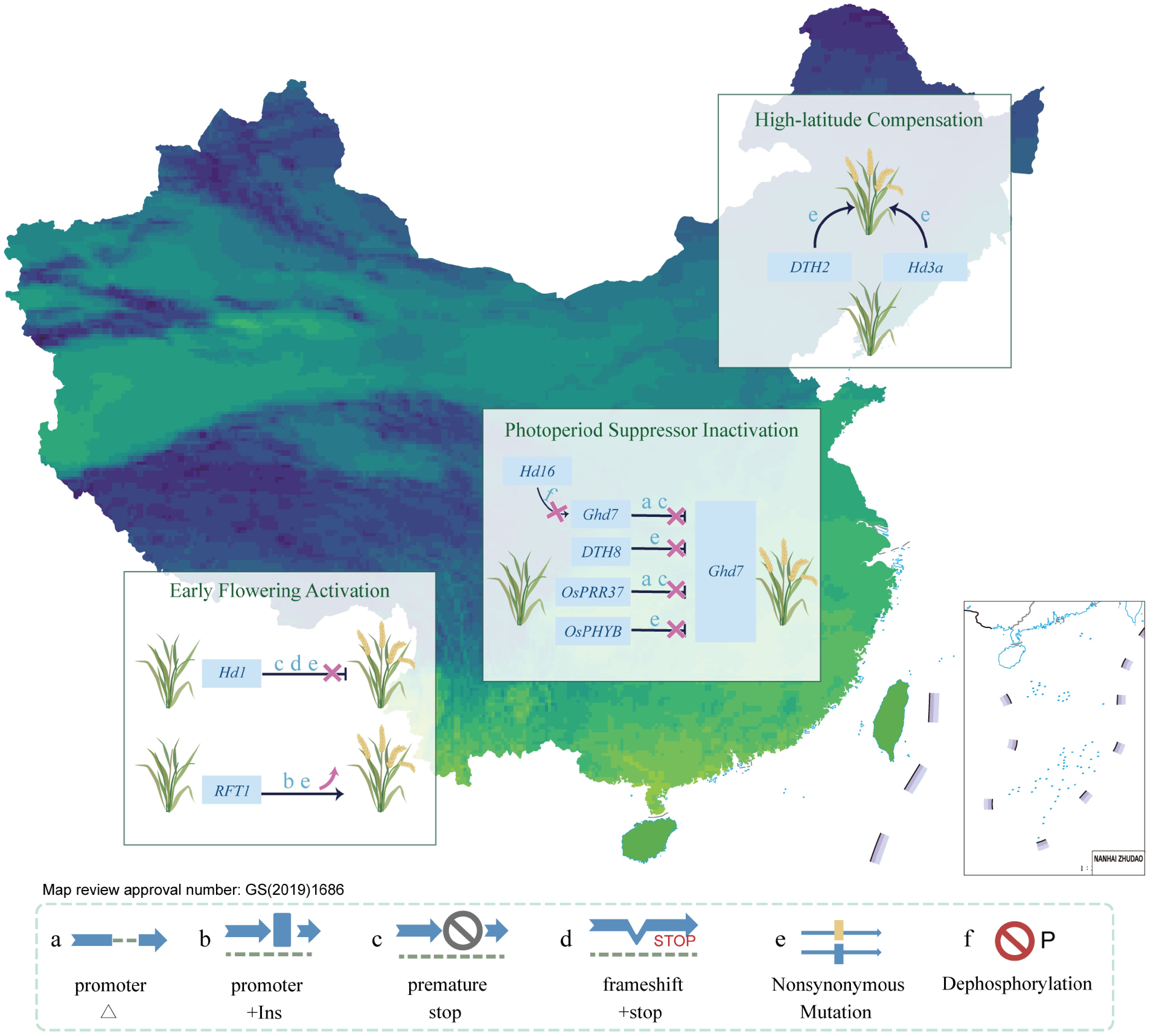

In the early stages of rice expansion from tropical to temperate regions, genetic reconfiguration focused on alleviating photoperiod-mediated repression of florigen expression. Among the key regulatory genes, Hd1 accumulated multiple natural mutations that enabled fine-tuning of heading date across diverse photoperiodic and geographic conditions. These included small deletions (2- and 4-bp) within the coding region, which introduced frameshift mutations and resulted in loss of protein function. Such variants are commonly found in tropical cultivars and wild rice, where they facilitate flowering under long-day conditions and support multi-seasonal cropping systems[58]. Additional nonsense and missense mutations, such as the Arg368 substitution, have also been identified, resulting in nonfunctional Hd1 alleles that promote early flowering in short-day environments like South and Southeast Asia[58]. In certain East Asian landraces, including the japonica cultivar Taichung 65, the insertion of a 1.9-kb fragment within exon two disrupts Hd1 function, reflecting region-specific selection trajectory during local adaptation[58].

At the transcriptional level, a 4.4-kb mobile element insertion within the Hd1 promoter silences its expression, resulting in a photoperiod-insensitive phenotype that is particularly advantageous for rice cultivation in temperate regions such as Europe[59]. In addition, a lysine deletion within the CCT domain disrupts the formation of Hd1–Nuclear Factor Y (NF-Y) transcriptional complexes, thereby weakening Hd1's regulatory function. This variant is commonly found in temperate japonica cultivars, where it contributes to extended growth duration, making it well-suited for shorter growing seasons[59]. These naturally occurring mutations highlight the ongoing selection for Hd1 plasticity during both the domestication process and the geographic expansion of rice[4,7,56,59].

Meanwhile, RFT1 has been identified as a compensatory florigen that functions under long-day conditions. Promoter-strengthening mutations, particularly tandem repeat expansions, are significantly enriched in japonica cultivars and enhance RFT1 transcription when Hd3a expression is repressed[5]. The glutamate residue at position 105 (E105) of the RFT1 protein is essential for its interaction with 14-3-3 proteins. A common E105K substitution found in indica weakens this protein-protein interaction, thereby diminishing RFT1-mediated floral induction, whereas japonica retains the functional E105 allele[60]. Collectively, the combination of Hd1 loss-of-function mutations and upregulated RFT1 activity contributed to the development of an early-flowering system, facilitating the initial northward expansion of japonica rice.

Strategy II: releasing photoperiodic suppression for long-day adaptation

-

As rice continued to expand into higher latitudes, the extended photoperiod posed additional challenges for the initiation of flowering. Although elevated RFT1 activity provided a florigenic signal, several upstream repressors remained active under long-day conditions, continuing to inhibit floral induction[61]. The second stage of adaptive evolution thus involved the stepwise loss or attenuation of these repressors, forming what may be termed a 'photoperiod unlocking module'. For example, promoter deletions in Ghd7 reduce its transcriptional activity, while a missense mutation in DTH8 impairs its physical interaction with Ghd7, both contributing to the derepression of Ehd1 expression[37,62]. Additionally, a missense mutation in Hd16, identified in the Japanese cultivar Koshihikari, attenuates CKI kinase activity, thereby lowering the phosphorylation efficiency of Ghd7 and promoting an accelerated floral transition under long-day conditions[34].

OsPRR37 is a major repressor of flowering under long-day conditions and exhibits extensive natural variation. In the indica cultivar IR64, a +1 insertion causes a frameshift and introduces a premature stop codon at amino acid position 120, resulting in a nonfunctional protein that fails to repress Ehd1 and Hd3a, thereby promoting flowering under long-day conditions[4]. In japonica cultivar Kita-ake, a TGG-to-TGA nonsense mutation in exon six similarly leads to early flowering in high-latitude environments[54]. Another variety, Akita 63, carries a 43-bp deletion in the OsPRR37 promoter region (−230 to −188 bp), which reduces gene expression and weakens its suppressive effect on flowering (ibid.). In the H143 background, an arginine-to-histidine substitution within the CCT domain compromises OsPRR37's coordination with Ghd7, further attenuating repression under long-day conditions[54]. In many high-latitude japonica cultivars, both OsPRR37 and Ghd7 are nonfunctional, jointly contributing to early flowering and providing a molecular basis for photoperiod adaptation in northern environments[4]. These null alleles can upregulate Ehd1 expression and advance heading date by more than 20 d[54]. In addition to coding region mutations, promoter single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertions/deletions (InDels) have also been identified that modulate OsPRR37 transcription and fine-tune its responsiveness to photoperiod[46,54]. Population genetic analyses reveal strong ecological differentiation of OsPRR37 haplotypes across latitudes, underscoring its critical role in long-day adaptation[63].

In addition to OsPRR37, OsPHYB, a red-light photoreceptor, exhibits substantial haplotype diversity. In high-latitude japonica varieties, the Group A haplotype, which contains several non-synonymous mutations, is notably enriched. These mutations are hypothesized to attenuate signal transduction to downstream Phytochrome-Interacting factor transcription factors, thereby alleviating the repression of Ehd1 and promoting the expression of Hd3a and RFT1. The difference in heading date between Group A and Group B haplotypes can exceed 15–20 d, and the frequency of Group A alleles increases with latitude, indicating strong geographic selection pressure[5,33,64]. A large-scale analysis of 783 global rice accessions further reveals that high-latitude varieties (> 30° N) frequently carry four or more loss-of-function alleles in Hd1, Ghd7, DTH8, and OsPHYB. This pattern suggests that adaptive variation tends to accumulate across multiple loci, forming a composite genetic architecture that underpins photoperiodic adaptation to long-day environments[56].

Strategy III: enhancing florigen signaling for heading stability in cold long-day environments

-

Following the release of floral repressors, further amplification of florigenic signals becomes essential to ensure timely heading under long-day and low-temperature conditions. DTH2 contains InDel polymorphisms in its promoter region that enhance its transcriptional activity[49,65]. In addition, specific missense mutations have been reported to increase its ability to promote flowering[63]. These variations enable DTH2 to activate Hd3a independently of Ehd1, and its alleles are under strong positive selection in japonica cultivars adapted to high-latitude environments[49,66]. Similarly, a novel Hd3a-435G coding variant enhances its interaction with 14-3-3 protein GF14b, thereby potentiating FAC activity and upregulating downstream MADS-box gene 14 (OsMADS14) expression, which accelerates heading in temperate environments[67].

Collectively, rice has evolved a multilayered flowering regulatory network centered on Hd3a and RFT1, orchestrated by upstream regulators such as Ghd7, Ehd1, and Hd1. Through the stepwise accumulation of both gain-and loss-of-function mutations, this network enables fine-tuned photoperiodic adaptation across diverse ecological gradients. These adaptations reflect not only isolated mutational events but also broader patterns of regional allele reshuffling, combinatorial variation, and phenotypic plasticity that have collectively reshaped the latitudinal distribution of cultivated rice (Fig. 3). However, as climate volatility and environmental stressors intensify, the adaptive potential of existing mutational resources may become increasingly limited. Addressing this emerging challenge will require a transition toward forward-looking breeding strategies. The next section outlines such strategies, ranging from the construction of dynamic germplasm networks and the integration of multi-omics data to artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted prediction and the synthetic redesign of regulatory pathways.

Figure 3.

Region-specific adaptation of rice flowering driven by regulatory gene variation. Region-specific allelic variation underlies the adaptive differentiation of heading date across China. In southern regions, loss-of-function mutations in Hd1 and upregulation of RFT1 promote early flowering under long-day conditions. In central areas, inactivation of repressors (Ghd7, DTH8, OsPRR37, OsPHYB) relieves photoperiod sensitivity. In northern high-latitude zones, compensatory mechanisms involving DTH2 and Hd3a ensure timely flowering. Major mutation types include: a, promoter deletion; b, promoter insertion; c, premature stop; d, frameshift + stop; e, nonsynonymous mutation; f, dephosphorylation site loss. These variations form the molecular basis for latitudinal flowering adaptation.

-

Modern rice breeding is guided by two central objectives: improving yield potential and enhancing ecological adaptability. While both are essential, the latter has become increasingly critical for securing global rice production under the threat of climate change[68]. However, ecological breeding still struggles with two key issues: regional adaptation and the acceleration of generational turnover. In high-altitude areas such as the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau and the mountainous regions of southwestern Yunnan, cultivation is constrained by short growing seasons and low-temperature stress. Current varieties show unstable heading and low seed-setting rates, making stable production difficult[69]. Meanwhile, in northern regions experiencing an upward shift in agro-climatic zone IV, extended daylength and persistent low temperatures significantly delay heading date. These trends underscore the urgency of developing regulatory networks capable of integrating multiple environmental cues. Progress in rice breeding is further constrained by the slow renewal of breeding materials and extended selection cycles. Traditional breeding workflows are time-consuming and offer limited ability to predict phenotypes at early stages, making them less responsive to rapidly changing agroecological conditions. Several structural constraints within current ecological breeding strategies contribute to these limitations. First, the over-reliance on a few major photoperiod-related gene mutations in widely cultivated varieties has simplified their regulatory networks. This reduces their ability to respond flexibly to daylength variation across ecological zones, limiting adaptability. Second, phenotypic data related to photoperiod and temperature responses remain limited, and trials are often conducted under homogeneous conditions. This hinders accurate assessment and application of adaptive traits. Third, wild rice and ecotype-specific landraces have not yet been integrated into high-throughput screening or early evaluation platforms. As a result, their regulatory gene resources remain underutilized. Fourth, the absence of genotype design strategies tailored to specific ecological zones compromises the stability and adaptability of varieties introduced to new regions.

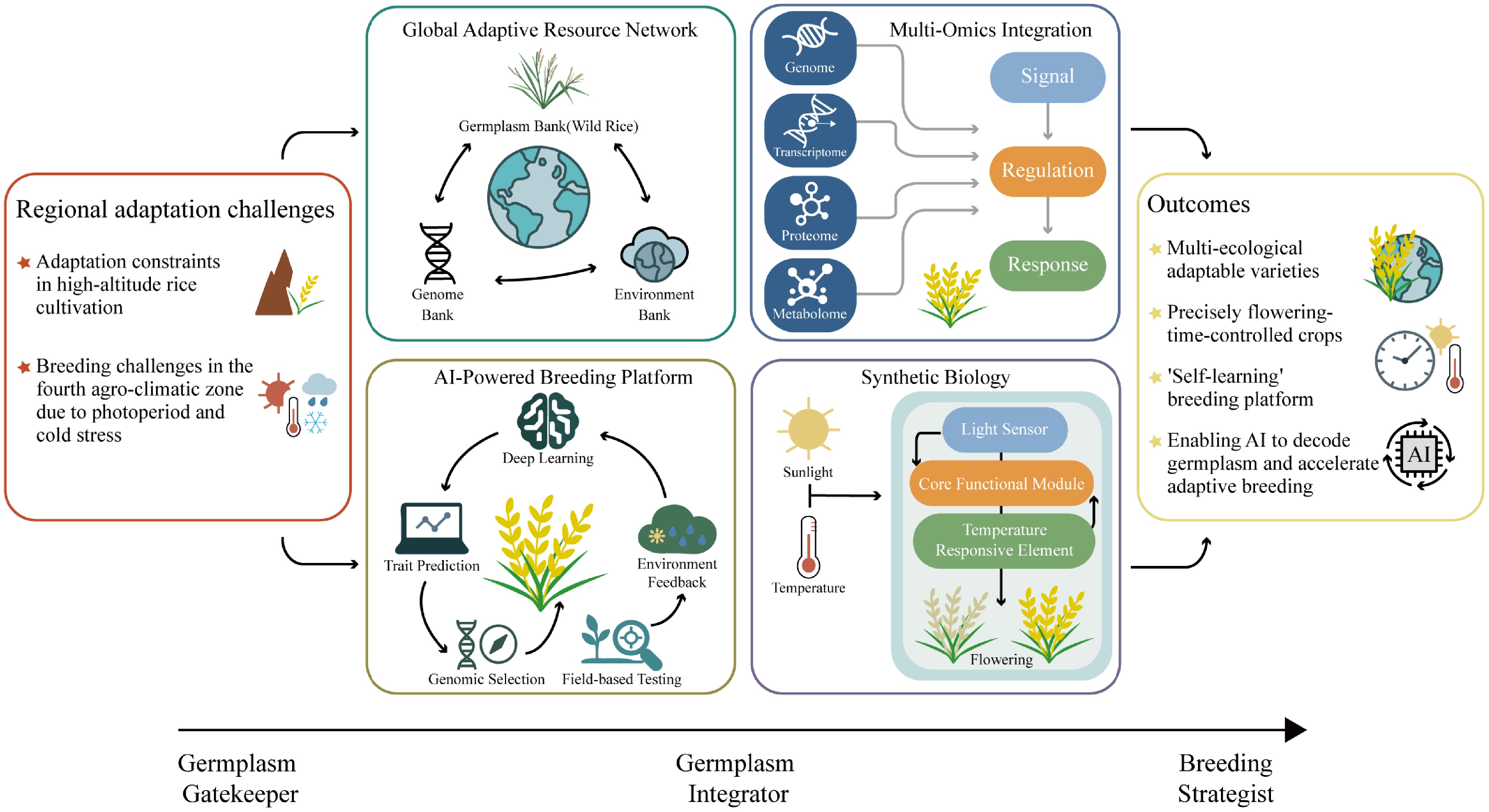

As cultivated rice becomes increasingly uniform and genetically rigid, wild rice populations offer a vital reservoir of ancestral regulatory diversity and transcriptional redundancy that confer strong environmental stability[68]. Studies have shown that upstream enhancers of Ehd1[70], compensatory expression of RFT1[71], and altered expression rhythms of OsPRR37[54] contribute to flowering stability under high-latitude and extreme conditions. These regulatory mechanisms offer critical genetic support for reconstructing photoperiod and circadian response pathways in rice. Therefore, tapping into the regulatory resources of wild rice may present new opportunities for improving adaptive breeding and addressing complex ecological challenges. Given the dual challenges of limited resource diversity and increasing environmental complexity, rice breeding must adopt interdisciplinary strategies. Integrating genetic resources, multi-omics approaches, and breeding workflows is essential for building a forward-looking adaptive improvement system (Fig. 4). First, build a global adaptive resource network that links germplasm repositories (including wild rice) with genomic and environmental databases, supported by standardized multi-location phenotyping and monitoring through regional platforms and national banks. Second, identify key regulators not only from established pathways but also from wild and ecotype-specific materials, and transfer useful alleles into elite backgrounds with minimal linkage drag using marker-assisted backcrossing, genomic background recovery, and targeted editing[72−74]. For example, the wild O. rufipogon QTL qHD7.2 was fine-mapped with CSSLs to a ~101.1-kb interval harboring a novel OsPRR37 allele that delays heading under long-day conditions while shortening panicle length, illustrating pleiotropy and how minimal donor segments help mitigate linkage drag[63]. When linkage drag persists or donor genomes are structurally complex, de novo domestication offers a complementary path: in allotetraploid Oryza alta, establishing efficient transformation and a reference genome enabled CRISPR (including multiplex) editing of domestication/agronomic gene homologs (e.g., qSH1, An-1, sd1, GS3), rapidly improving shattering, awn length, plant height, grain size, and heading date, thereby bypassing classical introgression constraints[75]. Third, an integrated resource platform should be developed by combining ecological experiments, climate modeling, high-throughput phenotyping, and advanced data analysis. This will support precise identification of important genotypes and help predict their adaptation potential in specific regions. The ultimate goal is to empower artificial intelligence to decode the complexity of germplasm resources, thereby improving genotype identification and region-specific adaptation forecasting. Fourth, it is essential to reconstruct regulatory pathways that integrate photoperiod, temperature, and abiotic stress responses using multi-omics approaches. This will enable a deeper understanding of early-flowering escape strategies and their potential for enhancing stress resilience. To advance this goal, artificial intelligence should be applied not merely for data processing, but to decode genotype–phenotype–environment (G × P × E) linkages and extract biologically meaningful patterns from complex datasets. By enabling intelligent systems to decode germplasm diversity, AI can provide more accurate predictions of environmental adaptation and guide the strategic deployment of key genetic resources. Recent advances, such as the AI-integrated breeding pipeline that combines genome editing and robotics to automate cross-pollination[76], predictive models can estimate heading date across sites[77]; image-based pipelines enable high-throughput scoring of flowering traits[78,79]; and climate-responsive simulations evaluate performance under future scenarios[80], illustrate the potential of AI to move from data handling toward operational decision-making in crop improvement. Fifth, combining bioinformatics tools with environmental simulation methods will enhance the identification and screening of critical regulatory elements. Building on this foundation, synthetic regulatory components can be designed to fine-tune responses to light and temperature signals. This may offer a viable path for breeding rice varieties with specific environmental responsiveness. As adaptive breeding systems evolve, germplasm researchers are shifting from passive gatekeepers to integrators and breeding strategists. Strengthening the connections among phenotypic traits, genotypic data, and environmental adaptability, along with advancing regulatory mechanism research and digital infrastructure, will be essential for supporting future rice breeding across diverse ecological zones.

Figure 4.

A strategic roadmap for smart and climate-resilient rice breeding. The roadmap highlights a transition from germplasm gatekeeper to strategic, technology-enabled breeding. Central components include the construction of a global adaptive resource network that links germplasm, genomic, and environmental data; multi-omics integration to decode signal-regulation-response pathways; AI-powered breeding platforms for predictive selection and field feedback; and synthetic biology approaches for programmable control of flowering traits. Together, these components support the development of intelligent, adaptive, and future-oriented rice breeding systems.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 32261143465 and 32350710198), the Project of Sanya Yazhou Bay Science and Technology City (Grant Nos SCKJ-JYRC-2023-47 and SKJC-2023-02-001), the Project of Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund (Grant No. 24HNZX-08), the Nanfan special project, CAAS (Grant Nos YBXM2503, YBXM2556, YBXM2501), the Project of Hainan Province 'Nanhai New Star' Technology Innovation Talent Platform (Grant No. NHXXRCXM202302), and the Project of Hainan Province Science and Technology Innovation (Grant No. KJRC2023A01), the Hainan Province International Scientific and Technological Cooperation Talent and Exchange Project (Foreign Expert Program) Plan (Grant No. G20241024007E).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper: conceived the manuscript: Qian Q, Zheng X, Zhou L; drafted the manuscript preparation: Zheng X, Zhou L, Liu Y, Sandamal S; literature review and data collection: Zhang Y, Tennakoon A. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Leina Zhou, Yinyin Liu, Salinda Sandamal

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Laboratory. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou L, Liu Y, Sandamal S, Zhang Y, Tennakoon A, et al. 2025. From germplasm diversity to genetic design: strategies for photoperiod adaptation in rice. Seed Biology 4: e020 doi: 10.48130/seedbio-0025-0020

From germplasm diversity to genetic design: strategies for photoperiod adaptation in rice

- Received: 15 August 2025

- Revised: 15 September 2025

- Accepted: 17 September 2025

- Published online: 13 November 2025

Abstract: Rice (Oryza sativa L.) serves as a model for understanding how domestication and ecological adaptation together shape the global distribution of crops. Originating in tropical and subtropical regions characterized by short-day photoperiods and high temperatures, rice has undergone thousands of years of human selection and environmental shaping. These processes have enabled its cultivation across a broad range of latitudes, climates, and photoperiod conditions. A key driver of this ecological plasticity is the genetic reprogramming of heading date regulation. This review focuses on the genetic network underlying photoperiodic control of heading date (HD), with a focus on the evolutionary trajectories of major regulators, including Heading date 1 (Hd1), Grains Height Date 7 (Ghd7), Days to heading 8 (DTH8), Early heading date 1 (Ehd1) and Heading date 3a (Hd3a)/RICE FLOWERING LOCUS T 1 (RFT1). The expansion of rice from tropical short-day to temperate long-day regions has been facilitated by loss-of-function mutations, expression divergence, and complex allelic combinations. Specific allele assemblies have also contributed to the divergence between indica and japonica subspecies, as well as to latitudinal adaptation. Despite the existence of over 780,000 germplasm accessions, a large portion of this germplasm diversity remains untapped. To bridge this gap, a conceptual framework for global adaptation that integrates multi-omics data, artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted modeling, and synthetic biology, is composed to reengineer heading date regulation. This review envisions a forward-looking breeding strategy that unites germplasm utilization, mechanistic understanding, and predictive design to develop rice varieties optimized for complex and variable agricultural environments.

-

Key words:

- Rice /

- Adaptive evolution /

- Heading date (HD) /

- Natural variation /

- Germplasm /

- AI-powered breeding