|

[1]

|

Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Zhao D, Yu X, Shen X, et al. 2024. TTD: Therapeutic Target Database describing target druggability information. Nucleic Acids Research 52:D1465−D1477 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad751

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[2]

|

Manglik A, Kobilka B. 2014. The role of protein dynamics in GPCR function: insights from the β2AR and rhodopsin. Current Opinion in Cell Biology 27:136−143 doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.01.008

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[3]

|

Hauser AS, Attwood MM, Rask-Andersen M, Schiöth HB, Gloriam DE. 2017. Trends in GPCR drug discovery: new agents, targets and indications. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 16:829−842 doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.178

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[4]

|

Wu B, Chien EYT, Mol CD, Fenalti G, Liu W, et al. 2010. Structures of the CXCR4 chemokine GPCR with small-molecule and cyclic peptide antagonists. Science 330:1066−1071 doi: 10.1126/science.1194396

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[5]

|

Rosenbaum DM, Cherezov V, Hanson MA, Rasmussen SGF, Thian FS, et al. 2007. GPCR engineering yields high-resolution structural insights into β2-adrenergic receptor function. Science 318:1266−1273 doi: 10.1126/science.1150609

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[6]

|

Cohen P. 2002. Protein kinases — the major drug targets of the twenty-first century? Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 1:309−315 doi: 10.1038/nrd773

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[7]

|

Yun CH, Mengwasser KE, Toms AV, Woo MS, Greulich H, et al. 2008. The T790M mutation in EGFR kinase causes drug resistance by increasing the affinity for ATP. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105:2070−2075 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709662105

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[8]

|

Noble MEM, Endicott JA, Johnson LN. 2004. Protein kinase inhibitors: insights into drug design from structure. Science 303:1800−1805 doi: 10.1126/science.1095920

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[9]

|

Klaeger S, Heinzlmeir S, Wilhelm M, Polzer H, Vick B, et al. 2017. The target landscape of clinical kinase drugs. Science 358:eaan4368 doi: 10.1126/science.aan4368

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[10]

|

Attwood MM, Fabbro D, Sokolov AV, Knapp S, Schiöth HB. 2021. Trends in kinase drug discovery: targets, indications and inhibitor design. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 20:839−861 doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00252-y

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[11]

|

Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Thomas PD, Huang X, Bateman A, et al. 2018. The MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors in 2017 and a comparison with peptidases in the PANTHER database. Nucleic Acids Research 46:D624−D632 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1134

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[12]

|

Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ. 1993. Evolutionary families of peptidases. Biochemical Journal 290:205−218 doi: 10.1042/bj2900205

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[13]

|

Raj VS, Mou H, Smits SL, Dekkers DHW, Müller MA, et al. 2013. Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 is a functional receptor for the emerging human coronavirus-EMC. Nature 495:251−254 doi: 10.1038/nature12005

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[14]

|

Nauck MA, Meier JJ, Cavender MA, Abd El Aziz M, Drucker DJ. 2017. Cardiovascular actions and clinical outcomes with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. Circulation 136:849−870 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028136

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[15]

|

Zhou CK, Liu ZZ, Peng ZR, Luo XY, Zhang XM, et al. 2025. M28 family peptidase derived from Peribacillus frigoritolerans initiates trained immunity to prevent MRSA via the complosome-phosphatidylcholine axis. Gut Microbes 17:2484386 doi: 10.1080/19490976.2025.2484386

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[16]

|

Hörlein AJ, Näär AM, Heinzel T, Torchia J, Gloss B, et al. 1995. Ligand-independent repression by the thyroid hormone receptor mediated by a nuclear receptor co-repressor. Nature 377:397−404 doi: 10.1038/377397a0

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[17]

|

Chen JD, Evans RM. 1995. A transcriptional co-repressor that interacts with nuclear hormone receptors. Nature 377:454−457 doi: 10.1038/377454a0

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[18]

|

Zhang M, Xie X, Chen E, Guo Y, Wang H, et al. 2025. The ribonucleoprotein hnRNP K promotes hepatic steatosis by suppressing the nuclear hormone receptor PPARα. Journal of Biological Chemistry 301:110500 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2025.110500

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[19]

|

Jefferson WN, Wang T, Padilla-Banks E, Williams CJ. 2024. Unexpected nuclear hormone receptor and chromatin dynamics regulate estrous cycle dependent gene expression. Nucleic Acids Research 52:10897−10917 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkae714

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[20]

|

Vlamis-Gardikas A, Aslund F, Spyrou G, Bergman T, Holmgren A. 1997. Cloning, overexpression, and characterization of glutaredoxin 2, an atypical glutaredoxin from Escherichia coli. Journal of Biological Chemistry 272:11236−11243 doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11236

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[21]

|

Abdelwaly A, Helal MA, Fathy MM, Alaaeldeen H, Klein ML, et al. 2025. Design and synthesis of novel small molecules targeting the Kv1.3 voltage-gated potassium ion channel. Scientific Reports 15:32756 doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-18086-8

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[22]

|

Kariev AM, Green ME. 2025. H+ and confined water in gating in many voltage-gated potassium channels: ion/water/counterion/protein networks and protons added to gate the channel. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26:7325 doi: 10.3390/ijms26157325

CrossRef Google Scholar

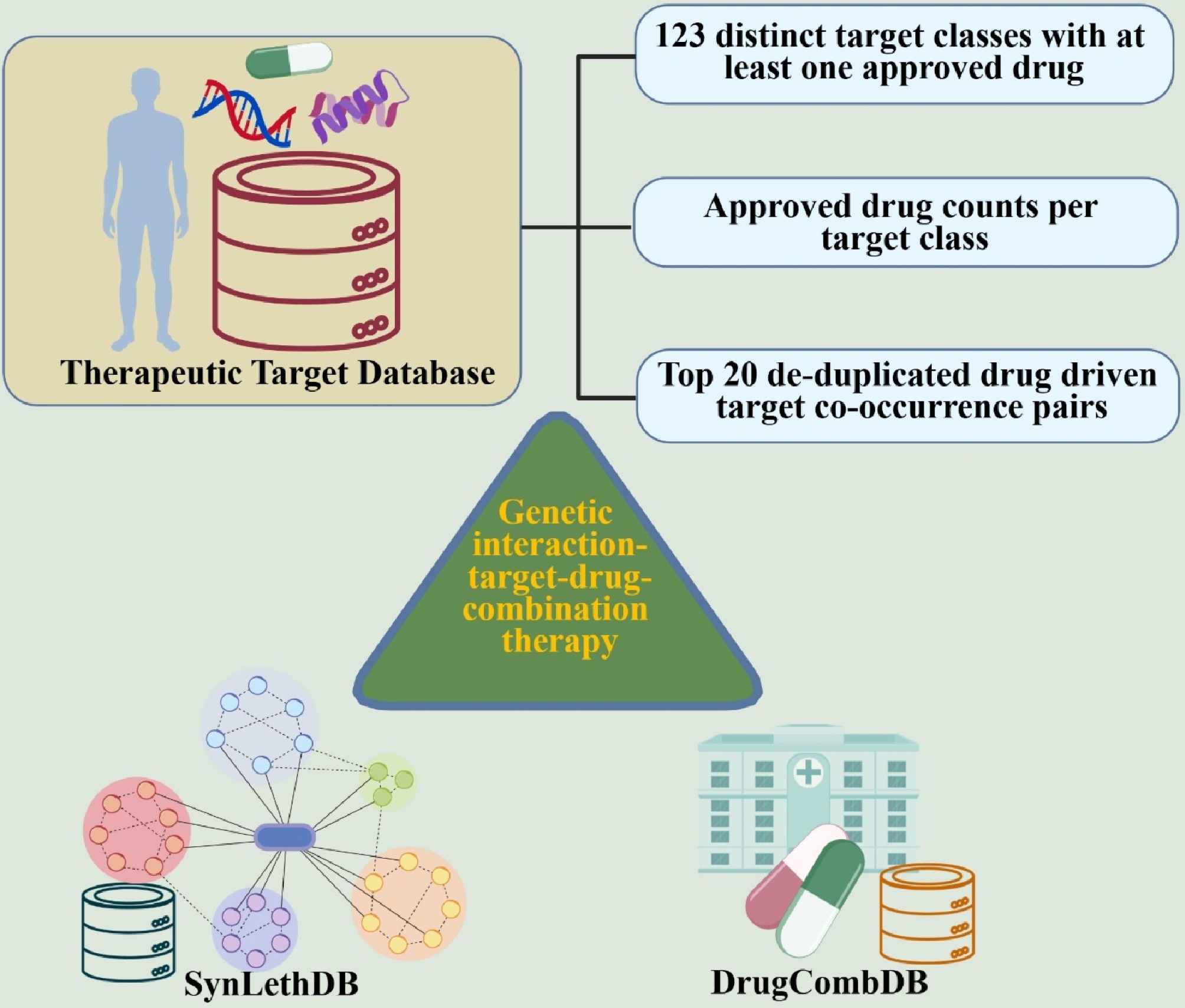

|

|

[23]

|

Catterall WA, Cestèle S, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Yu FH, Konoki K, et al. 2007. Voltage-gated ion channels and gating modifier toxins. Toxicon 49:124−141 doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.09.022

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[24]

|

Isom LL, De Jongh KS, Catterall WA. 1994. Auxiliary subunits of voltage-gated ion channels. Neuron 12:1183−1194 doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90436-7

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[25]

|

Lai HC, Jan LY. 2006. The distribution and targeting of neuronal voltage-gated ion channels. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 7:548−562 doi: 10.1038/nrn1938

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[26]

|

Schmitz J, Owyang A, Oldham E, Song Y, Murphy E, et al. 2005. IL-33, an interleukin-1-like cytokine that signals via the IL-1 receptor-related protein ST2 and induces T helper type 2-associated cytokines. Immunity 23:479−490 doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.09.015

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[27]

|

Bauernfeind FG, Horvath G, Stutz A, Alnemri ES, MacDonald K, et al. 2009. Cutting edge: NF-κB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. The Journal of Immunology 183:787−791 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901363

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[28]

|

Kotenko SV, Gallagher G, Baurin VV, Lewis-Antes A, Shen M, et al. 2003. IFN-λs mediate antiviral protection through a distinct class II cytokine receptor complex. Nature Immunology 4:69−77 doi: 10.1038/ni875

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[29]

|

Kunze R, Navratil F, Beichert J, Geyer F, Floss DM, et al. 2025. iBody-mediated tuning of synthetic cytokine receptor activation via rational nanobody interface engineering. mAbs 17:2563009 doi: 10.1080/19420862.2025.2563009

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[30]

|

Naz F, Arish M, Singh S, Naqvi N, Alam A. 2025. Mycobacterium tuberculosis PE5 stimulates anti-inflammatory cytokine production via innate immune toll-like receptor 4 signaling. Microbial Pathogenesis 208:107966 doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2025.107966

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[31]

|

Ercan M, Fırat Oğuz E, Özcan M, Alp HH. 2026. Within- and Between-Subject biological variation estimates of serum free light immunoglobulin chains in healthy individuals in Turkey. Clinica Chimica Acta 578:120545 doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2025.120545

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[32]

|

Wang Y, Liu N, Zou Y, Jie J, Liu Z, et al. 2026. A robust label-free workflow for the immunoglobulin G subclass site-specific N-glycopeptides and the glycosylation of IgG 2 correlated with colorectal cancer. Talanta 296:128326 doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2025.128326

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[33]

|

Ishida Y, Agata Y, Shibahara K, Honjo T. 1992. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. The EMBO Journal 11:3887−3895 doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05481.x

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[34]

|

van Dongen JJM, Langerak AW, Brüggemann M, Evans PAS, Hummel M, et al. 2003. Design and standardization of PCR primers and protocols for detection of clonal immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene recombinations in suspect lymphoproliferations: report of the BIOMED-2 concerted action BMH4-CT98-3936. Leukemia 17:2257−2317 doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403202

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[35]

|

Rief M, Gautel M, Oesterhelt F, Fernandez JM, Gaub HE. 1997. Reversible unfolding of individual titin immunoglobulin domains by AFM. Science 276:1109−1112 doi: 10.1126/science.276.5315.1109

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[36]

|

Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. 2010. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature 466:835−40 doi: 10.1038/nature09267

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[37]

|

Cheng Q, Wei T, Farbiak L, Johnson LT, Dilliard SA, et al. 2020. Selective organ targeting (SORT) nanoparticles for tissue-specific mRNA delivery and CRISPR–Cas gene editing. Nature Nanotechnology 15:313−320 doi: 10.1038/s41565-020-0669-6

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[38]

|

Llave C, Xie Z, Kasschau KD, Carrington JC. 2002. Cleavage of scarecrow-like mRNA targets directed by a class of Arabidopsis miRNA. Science 297:2053−2056 doi: 10.1126/science.1076311

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[39]

|

Yoon JH, Abdelmohsen K, Srikantan S, Yang X, Martindale Jennifer L, et al. 2012. LincRNA-p21 suppresses target mRNA translation. Molecular Cell 47:648−655 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.027

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[40]

|

Luo PK, Chang WA, Peng SY, Chu LA, Chuang YH, et al. 2026. Endogenous macrophages as "Trojan horses" for targeted oral delivery of mRNA-encoded cytokines in tumor microenvironment immunotherapy. Biomaterials 325:123620 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2025.123620

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[41]

|

Xiong XC, Zhang NN, Wu M, Cao TS, Deng K, et al. 2025. Development and characterization of a bivalent mRNA vaccine targeting the Delta and Omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics 21:2562730 doi: 10.1080/21645515.2025.2562730

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[42]

|

Hou X, Zaks T, Langer R, Dong Y. 2021. Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nature Reviews Materials 6:1078−1094 doi: 10.1038/s41578-021-00358-0

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[43]

|

Tenchov R, Bird R, Curtze AE, Zhou Q. 2021. Lipid nanoparticles─from liposomes to mRNA vaccine delivery, a landscape of research diversity and advancement. ACS Nano 15:16982−17015 doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c04996

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[44]

|

Ouranidis A, Vavilis T, Mandala E, Davidopoulou C, Stamoula E, et al. 2022. mRNA Therapeutic Modalities Design, Formulation and Manufacturing under Pharma 4.0 Principles. Biomedicines 10:50 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines10010050

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[45]

|

Lu RM, Hsu HE, Perez SJLP, Kumari M, Chen GH, et al. 2024. Current landscape of mRNA technologies and delivery systems for new modality therapeutics. Journal of Biomedical Science 31:89 doi: 10.1186/s12929-024-01080-z

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[46]

|

Zhang M, Hussain A, Yang H, Zhang J, Liang XJ, et al. 2023. mRNA-based modalities for infectious disease management. Nano Research 16:672−691 doi: 10.1007/s12274-022-4627-5

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[47]

|

Bersuker K, Hendricks JM, Li Z, Magtanong L, Ford B, et al. 2019. The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to GPX4 to inhibit ferroptosis. Nature 575:688−692 doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1705-2

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[48]

|

Mazel D, Pochet S, Marlière P. 1994. Genetic characterization of polypeptide deformylase, a distinctive enzyme of eubacterial translation. The EMBO Journal 13:914−923 doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06335.x

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[49]

|

Jadhav R, Shekar A, Westenhaver Z, Skandhan A. 2025. Abstract 4370073: a delayed diagnosis of anti-HMG-CoA reductase immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy. Circulation 152:A4370073 doi: 10.1161/circ.152.suppl_3.4370073

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[50]

|

Leitans J, Kazaks A, Balode A, Ivanova J, Zalubovskis R, et al. 2015. Efficient Expression and Crystallization System of Cancer-Associated Carbonic Anhydrase Isoform IX. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 58:9004−09 doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01343

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[51]

|

Ruusuvuori E, Hong L, Huttu K, Palva JM, Smirnov S, et al. 2004. Carbonic anhydrase isoform VII acts as a molecular switch in the development of synchronous gamma-frequency firing of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. The Journal of Neuroscience 24:2699−2707 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5176-03.2004

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[52]

|

Temperini C, Scozzafava A, Vullo D, Supuran CT. 2006. Carbonic anhydrase activators. Activation of isozymes I, II, IV, VA, VII, and XIV with l- and d-histidine and crystallographic analysis of their adducts with isoform II: engineering proton-transfer processes within the active site of an enzyme. Chemistry 12:7057−66 doi: 10.1002/chem.200600159

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[53]

|

Kamel EM, Ahmed NA, Maodaa S, Abuamarah BA, Othman SI, et al. 2025. Entrance-channel plugging by natural sulfonamide antibiotics yields isoform-selective carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors: an integrated in silico/ in vitro discovery of the lead SB-203207. BMC Chemistry 19:263 doi: 10.1186/s13065-025-01634-8

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[54]

|

Torres SW, Lan C, Harthorn A, Schmitz Z, Blanchard PL, et al. 2025. Molecular determinants of affinity and isoform selectivity in protein─small molecule hybrid inhibitors of carbonic anhydrase. Bioconjugate Chemistry 36:549−562 doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5c00006

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[55]

|

Ives NJ, Stowe RL, Marro J, Counsell C, Macleod A, et al. 2004. Monoamine oxidase type B inhibitors in early Parkinson's disease: meta-analysis of 17 randomised trials involving 3525 patients. BMJ 329:593 doi: 10.1136/bmj.38184.606169.ae

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[56]

|

Scozzafava A, Supuran CT. 2000. Carbonic anhydrase and matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors: sulfonylated amino acid hydroxamates with MMP inhibitory properties act as efficient inhibitors of CA isozymes I, II, and IV, and N-hydroxysulfonamides inhibit both these zinc enzymes. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 43:3677−3687 doi: 10.1021/jm000027t

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[57]

|

Mori M, Li G, Abe I, Nakayama J, Guo Z, et al. 2006. Lanosterol synthase mutations cause cholesterol deficiency–associated cataracts in the Shumiya cataract rat. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 116:395−404 doi: 10.1172/jci20797

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[58]

|

Mullins EA, Francois JA, Kappock TJ. 2008. A specialized citric acid cycle requiring succinyl-coenzyme A (CoA): acetate CoA-transferase (AarC) confers acetic acid resistance on the acidophile Acetobacter aceti. Journal of Bacteriology 190:4933−4940 doi: 10.1128/JB.00405-08

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[59]

|

Kusano H, Li H, Minami H, Kato Y, Tabata H, et al. 2019. Evolutionary developments in plant specialized metabolism, exemplified by two transferase families. Frontiers in Plant Science 10:794 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00794

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[60]

|

Hediger MA, Romero MF, Peng JB, Rolfs A, Takanaga H, et al. 2004. The ABCs of solute carriers: physiological, pathological and therapeutic implications of human membrane transport proteins. Pflügers Archiv 447:465−468 doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1192-y

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[61]

|

César-Razquin A, Snijder B, Frappier-Brinton T, Isserlin R, Gyimesi G, et al. 2015. A call for systematic research on solute carriers. Cell 162:478−487 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.022

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[62]

|

Palmiter RD, Huang L. 2004. Efflux and compartmentalization of zinc by members of the SLC30 family of solute carriers. Pflügers Archiv 447:744−751 doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1070-7

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[63]

|

Kirii M, Yoshida Y, Takashima S, Uchio-Yamada K, Oh-hashi K. 2025. Transcriptional regulation of solute carrier family 6 member 9 gene. Molecular Biology Reports 52:540 doi: 10.1007/s11033-025-10591-3

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[64]

|

Ren X, Li W. 2025. Iron-handling solute carrier SLC22A17 as a blood–brain barrier target after stroke. Neural Regeneration Research 20:3207−3208 doi: 10.4103/NRR.NRR-D-24-00811

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[65]

|

Markadieu N, Delpire E. 2014. Physiology and pathophysiology of SLC12A1/2 transporters. Pflügers Archiv - European Journal of Physiology 466:91−105 doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1370-5

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[66]

|

Yokomori T, Tozaki T, Ohnuma A, Ishimaru M, Sato F, et al. 2024. Non-synonymous substitutions in Cadherin 13, solute carrier family 6 member 4, and monoamine oxidase A genes are associated with personality traits in thoroughbred horses. Behavior Genetics 54:333−341 doi: 10.1007/s10519-024-10186-x

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[67]

|

Brown KK, Hann MM, Lakdawala AS, Santos R, Thomas PJ, et al. 2018. Approaches to target tractability assessment - a practical perspective. Medchemcomm 9:606−613 doi: 10.1039/C7MD00633K

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[68]

|

Ou B, Hampsch-Woodill M, Prior RL. 2001. Development and validation of an improved oxygen radical absorbance capacity assay using fluorescein as the fluorescent probe. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 49:4619−4626 doi: 10.1021/jf010586o

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[69]

|

Gulati P, Taneja S, Ramasamy SK. 2026. Recent progress and developments on phenothiazine-based fluorescence probe for hypochlorous acid sensing. Journal of Molecular Structure 1349:143837 doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2025.143837

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[70]

|

Matuskey D, Gallezot JD, Nabulsi N, Henry S, Torres K, et al. 2023. Neurotransmitter transporter occupancy following administration of centanafadine sustained-release tablets: a phase 1 study in healthy male adults. Journal of Psychopharmacology 37:164−71 doi: 10.1177/02698811221140008

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[71]

|

Simon A, Nghiem KS, Gampe N, Garádi Z, Boldizsár I, et al. 2022. Stability study of Alpinia galanga constituents and investigation of their membrane permeability by ChemGPS-NP and the parallel artificial membrane permeability assay. Pharmaceutics 14:1967 doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14091967

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[72]

|

Madras BK, Xie Z, Lin Z, Jassen A, Panas H, et al. 2006. Modafinil occupies dopamine and norepinephrine transporters in vivo and modulates the transporters and trace amine activity in vitro. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 319:561−569 doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.106583

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[73]

|

Verrico CD, Miller GM, Madras BK. 2007. MDMA (Ecstasy) and human dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin transporters: implications for MDMA-induced neurotoxicity and treatment. Psychopharmacology 189:489−503 doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0174-5

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[74]

|

Bottalico B, Larsson I, Brodszki J, Hernandez-Andrade E, Casslén B, et al. 2004. Norepinephrine Transporter (NET), Serotonin Transporter (SERT), Vesicular Monoamine Transporter (VMAT2) and Organic Cation Transporters (OCT1, 2 and EMT) in human placenta from pre-eclamptic and normotensive pregnancies. Placenta 25:518−529 doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2003.10.017

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[75]

|

Meltzer PC, Butler D, Deschamps JR, Madras BK. 2006. 1-(4-Methylphenyl)-2-pyrrolidin-1-yl-pentan-1-one (pyrovalerone) analogues: a promising class of monoamine uptake inhibitors. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 49:1420−1432 doi: 10.1021/jm050797a

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[76]

|

Green H, Persson M, Wikström M, Monti MC. 2025. In vitro monoamine reuptake inhibition and forensic case series in Sweden of the synthetic cathinones 2-, 3-, and 4-Me-alpha-PiHP. Forensic Science International 377:112657 doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2025.112657

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[77]

|

Persson M, Vikingsson S, Kronstrand R, Green H. 2024. Characterization of neurotransmitter inhibition for seven cathinones by a proprietary fluorescent dye method. Drug Testing and Analysis 16:339−347 doi: 10.1002/dta.3547

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[78]

|

Sora I, Hall FS, Andrews AM, Itokawa M, Li XF, et al. 2001. Molecular mechanisms of cocaine reward: Combined dopamine and serotonin transporter knockouts eliminate cocaine place preference. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98:5300−05 doi: 10.1073/pnas.091039298

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[79]

|

Shen HW, Hagino Y, Kobayashi H, Shinohara-Tanaka K, Ikeda K, et al. 2004. Regional differences in extracellular dopamine and serotonin assessed by in vivo microdialysis in mice lacking dopamine and/or serotonin transporters. Neuropsychopharmacology 29:1790−1799 doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300476

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[80]

|

Capuron L, Miller AH. 2011. Immune system to brain signaling: Neuropsychopharmacological implications. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 130:226−238 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.01.014

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[81]

|

Nakatsuka N, Yang KA, Abendroth JM, Cheung KM, Xu X, et al. 2018. Aptamer–field-effect transistors overcome Debye length limitations for small-molecule sensing. Science 362:319−324 doi: 10.1126/science.aao6750

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[82]

|

Marder SR, Davis JM, Chouinard G. 1997. The effects of risperidone on the five dimensions of schizophrenia derived by factor analysis: combined results of the North American trials. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 58:538−546 doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n1205

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[83]

|

Daw ND, Kakade S, Dayan P. 2002. Opponent interactions between serotonin and dopamine. Neural Networks 15:603−616 doi: 10.1016/S0893-6080(02)00052-7

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[84]

|

Shapiro DA, Renock S, Arrington E, Chiodo LA, Liu LX, et al. 2003. Aripiprazole, a novel atypical antipsychotic drug with a unique and robust pharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology 28:1400−1411 doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300203

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[85]

|

Ichikawa J, Ishii H, Bonaccorso S, Fowler WL, O'Laughlin IA, et al. 2001. 5-HT2A and D2 receptor blockade increases cortical DA release via 5-HT1A receptor activation: a possible mechanism of atypical antipsychotic-induced cortical dopamine release. Journal of Neurochemistry 76:1521−1531 doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00154.x

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[86]

|

Brunello N, Masotto C, Steardo L, Markstein R, Racagni G. 1995. New Insights into the Biology of Schizophrenia through the Mechanism of Action of Clozapine. Neuropsychopharmacology 13:177−213 doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00068-O

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[87]

|

Łupina M, Wąsik A, Baranowska-Bosiacka I, Tarnowski M, Słowik T, et al. 2024. Acute and chronic exposure to linagliptin, a selective inhibitor of dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4), has an effect on dopamine, serotonin and noradrenaline level in the striatum and hippocampus of rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25:3008 doi: 10.3390/ijms25053008

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[88]

|

Collin F, Karkare S, Maxwell A. 2011. Exploiting bacterial DNA gyrase as a drug target: current state and perspectives. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 92:479−497 doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3557-z

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[89]

|

Gradišar H, Pristovšek P, Plaper A, Jerala R. 2007. Green tea catechins inhibit bacterial DNA gyrase by interaction with its ATP binding site. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 50:264−271 doi: 10.1021/jm060817o

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[90]

|

Khalid M, Haider A, Shahzadi I, Ul-Hamid A, Imran M, et al. 2025. Dual functional samarium-chitosan doped CdTe nanoparticles: Dye degradation and bacterial inhibition targeting DHFR and DNA gyrase. Surfaces and Interfaces 72:107046 doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.38.1.97

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[91]

|

Ferrero L, Cameron B, Manse B, Lagneaux D, Crouzet J, et al. 1994. Cloning and primary structure of Staphylococcus aureus DNA topoisomerase IV: a primary target of fluoroquinolones. Molecular Microbiology 13:641−653 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00458.x

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[92]

|

Drlica K, Zhao X. 1997. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 61:377−392 doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.3.377-392.1997

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[93]

|

Aldred KJ, Kerns RJ, Osheroff N. 2014. Mechanism of Quinolone Action and Resistance. Biochemistry 53:1565−74 doi: 10.1021/bi5000564

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[94]

|

Pham TDM, Ziora ZM, Blaskovich MAT. 2019. Quinolone antibiotics. Medchemcomm 10:1719−1739 doi: 10.1039/C9MD00120D

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[95]

|

Patil GS, Gaikwad KN, Suryawanshi SS, Bhandurge P. 2025. A comprehensive review on discovery, development, the chemistry of quinolones, and their antimicrobial resistance. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 00:1−16 doi: 10.2174/0115680266355989250730072511

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[96]

|

Khanna A, Narang A, Thakur V, Singh K, Kumar N, et al. 2025. Design, synthesis, antibacterial evaluation, and molecular modelling studies of 1,2,3-triazole-linked coumarin-vanillin hybrids as potential DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV inhibitors. Bioorganic Chemistry 164:108815 doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2025.108815

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[97]

|

Zhu M, Tse MW, Weller J, Chen J, Blainey PC. 2021. The future of antibiotics begins with discovering new combinations. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1496:82−96 doi: 10.1111/nyas.14649

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[98]

|

Silverstein FE, Faich G, Goldstein JL, Simon LS, Pincus T, et al. 2000. Gastrointestinal toxicity with celecoxib vs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: The CLASS Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 284:1247−1255 doi: 10.1001/jama.284.10.1247

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[99]

|

Vane JR, Bakhle YS, Botting RM. 1998. Cyclooxygenases 1 and 2. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 38:97−120

Google Scholar

|

|

[100]

|

Smith WL, DeWitt DL, Garavito RM. 2000. Cyclooxygenases: structural, cellular, and molecular biology. Annual Review of Biochemistry 69:145−182 doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.145

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[101]

|

Abdul-Malik MA, El-Dean AMK, Hussein AHM, Abdelmonsef AH, Tolba MS. 2026. Synthesis, in silico and in vivo evaluation of new pyrazole-based thiosemicarbazones containing thiazole and thiazolone moieties as potential anti-inflammatory agents. Journal of Molecular Structure 1350:143990 doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2025.143990

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[102]

|

Isa A, Banevičiūtė E, Piskin E, Cetinkaya A, Atici EB, et al. 2026. Design of an electrochemical sensor based on molecularly imprinted polymers for sensitive and selective detection of the JAK inhibitor baricitinib. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 267:117154 doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2025.117154

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[103]

|

Zaretsky JM, Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DS, Escuin-Ordinas H, Hugo W, et al. 2016. Mutations Associated with Acquired Resistance to PD-1 Blockade in Melanoma. The New England Journal of Medicine 375:819−829 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1604958

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[104]

|

Heinrich PC, Behrmann I, Müller-Newen G, Schaper F, Graeve L. 1998. Interleukin-6-type cytokine signalling through the gp130/Jak/STAT pathway. The Biochemical Journal 334:297−314 doi: 10.1042/bj3340297

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[105]

|

Verstovsek S, Kantarjian H, Mesa RA, Pardanani AD, Cortes-Franco J, et al. 2010. Safety and efficacy of INCB018424, a JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor, in myelofibrosis. The New England Journal of Medicine 363:1117−1127 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002028

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[106]

|

McNally R, Eck MJ. 2014. JAK–cytokine receptor recognition, unboxed. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 21:431−33 doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2824

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[107]

|

Tong X, Qiao S, Dong Z, Zhao X, Du X, et al. 2024. Targeting CSF1R in myeloid-derived suppressor cells: insights into its immunomodulatory functions in colorectal cancer and therapeutic implications. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 22:409 doi: 10.1186/s12951-024-02584-4

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[108]

|

Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. 2009. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nature Reviews Cancer 9:798−809 doi: 10.1038/nrc2734

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[109]

|

Heinrich PC, Behrmann I, Haan S, Hermanns HM, Müller-Newen G, et al. 2003. Principles of interleukin (IL)-6-type cytokine signalling and its regulation. The Biochemical Journal 374:1−20 doi: 10.1042/bj20030407

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[110]

|

Wang Z, Wang M, Sun Y. 2025. Vitiligo exacerbation during upadacitinib treatment for atopic dermatitis and improvement following a switch to abrocitinib: a case report. Journal of Dermatological Treatment 36:2528344 doi: 10.1080/09546634.2025.2528344

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[111]

|

Li X, Lewis MT, Huang J, Gutierrez C, Osborne CK, et al. 2008. Intrinsic resistance of tumorigenic breast cancer cells to chemotherapy. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 100:672−9 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn123

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[112]

|

Aggarwal BB, Shishodia S. 2006. Molecular targets of dietary agents for prevention and therapy of cancer. Biochemical Pharmacology 71:1397−1421 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.02.009

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[113]

|

Mekheimer RA, Al-Sheikh MA, Medrasi HY, Jaragh-Alhadad L, Moustafa MS, et al. 2026. Design, synthesis, and antiproliferative activity of antipyrine linked 2-amino-quinoline-3-carbonitrile derivatives as potential dual EGFR/HER-2 inhibitors. Journal of Molecular Structure 1349:143789 doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2025.143789

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[114]

|

Munir M, Forentin AM, Febrian MB, Fakih TM, Utomo RY, et al. 2025. Radiosynthesis of [131I]I-hesperidin: optimization, physicochemical profiling, and computational insights for targeted radiopharmaceuticals. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 225:111977 doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2025.111977

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[115]

|

Salemi A, Zenjanab MK, Adili Aghdam MA, Sahragardan N, Esfahlan RJ. 2025. Niosome-loaded silibinin and methotrexate for synergistic breast cancer combination chemotherapy: in silico and in vitro study. Cancer Cell International 25:336 doi: 10.1186/s12935-025-03977-7

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[116]

|

Moura SPSP, Cascante M, Rufino I, Guedes RC, Marin S, et al. 2025. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel carnosic acid derivatives with anticancer activity. RSC Advances 15:36861−36878 doi: 10.1039/D5RA02441B

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[117]

|

Hu H, Wang Y, Wang M, Zhang Z, Gu X, et al. 2025. Translational Research on the Oral Delivery of the Cytotoxic PROTAC Molecule via Tumor-Targeting Prodrug Strategy for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Treatment. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 68:20464−86 doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5c01640

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[118]

|

Vani S, Balasubramanyam D, Karthickeyan SMK, Tirumurugan KG, Gopinathan A, et al. 2025. Genome-wide selective sweeps providing classic evidence of emotional and behavioural control in Bos indicus cattle breeds. Journal of Livestock Science 16:392−401 doi: 10.33259/jlivestsci.2025.392-401

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[119]

|

Shang Y, Wang Q, Feng S, Du Z, Liang S, et al. 2024. Antioxidant mechanism of black garlic based on network pharmacology and molecular docking. Journal of Biobased Materials and Bioenergy 18:215−224 doi: 10.1166/jbmb.2024.2374

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[120]

|

McCoach CE, Le AT, Gowan K, Jones K, Schubert L, et al. 2018. Resistance mechanisms to targeted therapies in ROS1+ and ALK+ non-small cell lung cancer. Clinical Cancer Research 24:3334−3347 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2452

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[121]

|

Suehara Y, Alex D, Bowman A, Middha S, Zehir A, et al. 2019. Clinical genomic sequencing of pediatric and adult osteosarcoma reveals distinct molecular subsets with potentially targetable alterations. Clinical Cancer Research 25:6346−6356 doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-4032

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[122]

|

Gorin NC. 2022. Développements thérapeutiques en hématologie au XXIe siècle. Bulletin de l'Académie Nationale de Médecine 206:952−60 doi: 10.1016/j.banm.2022.07.005

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[123]

|

Pyne S, Pyne NJ. 2000. Sphingosine 1-phosphate signalling in mammalian cells. The Biochemical Journal 349:385−402 doi: 10.1042/bj3490385

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[124]

|

Hunter T. 2012. Why nature chose phosphate to modify proteins. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London Series b, Biological Sciences 367:2513−2516 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0013

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[125]

|

Karaman MW, Herrgard S, Treiber DK, Gallant P, Atteridge CE, et al. 2008. A quantitative analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nature Biotechnology 26:127−132 doi: 10.1038/nbt1358

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[126]

|

Lipson D, Capelletti M, Yelensky R, Otto G, Parker A, et al. 2012. Identification of new ALK and RET gene fusions from colorectal and lung cancer biopsies. Nature Medicine 18:382−384 doi: 10.1038/nm.2673

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[127]

|

Inuzuka H, Shaik S, Onoyama I, Gao D, Tseng A, et al. 2011. SCFFBW7 regulates cellular apoptosis by targeting MCL1 for ubiquitylation and destruction. Nature 471:104−109 doi: 10.1038/nature09732

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[128]

|

Louandre C, Ezzoukhry Z, Godin C, Barbare JC, Mazière JC, et al. 2013. Iron-dependent cell death of hepatocellular carcinoma cells exposed to sorafenib. International Journal of Cancer 133:1732−1742 doi: 10.1002/ijc.28159

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[129]

|

Gao S, Wang X, Zhao X, Xiao Z. 2026. Rational design of next-generation FLT3 inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia: from laboratory to clinics. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 301:118214 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2025.118214

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[130]

|

Yuan Y, Wang MR, Ding Y, Lin Y, Xu TT, et al. 2025. Lenvatinib promotes hepatocellular carcinoma pyroptosis by regulating GSDME palmitoylation. Cancer Biology & Therapy 26:2532217 doi: 10.1080/15384047.2025.2532217

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[131]

|

Guo J, Liu H, Zheng J. 2016. SynLethDB: synthetic lethality database toward discovery of selective and sensitive anticancer drug targets. Nucleic Acids Research 44:D1011−D1017 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1108

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[132]

|

Wang J, Wu M, Huang X, Wang L, Zhang S, et al. 2022. SynLethDB 2.0: a web-based knowledge graph database on synthetic lethality for novel anticancer drug discovery. Database 2022:baac030 doi: 10.1093/database/baac030

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[133]

|

Ying S, Hamdy FC, Helleday T. 2012. Mre11-dependent degradation of stalled DNA replication forks is prevented by BRCA2 and PARP1. Cancer Research 72:2814−2821 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.c.6503301

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[134]

|

Liu H, Zhang W, Zou B, Wang J, Deng Y, Deng L. 2020. DrugCombDB: a comprehensive database of drug combinations toward the discovery of combinatorial therapy. Nucleic Acids Research 48:D871−D881 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1007

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[135]

|

Neri D, Supuran CT. 2011. Interfering with pH regulation in tumours as a therapeutic strategy. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 10:767−777 doi: 10.1038/nrd3554

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[136]

|

Supuran CT. 2016. Structure and function of carbonic anhydrases. The Biochemical Journal 473:2023−2032 doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160115

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[137]

|

Pala N, Ladu F, Szlasa W, Cadoni R, Lomelino C, et al. 2025. Design, anticancer activity, and mechanistic evaluation of a novel class of selective human carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors featuring a trifluorodihydroxypropanone pharmacophore. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 298:118043 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2025.118043

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[138]

|

Jung S, Strotmann R, Schultz G, Plant TD. 2002. TRPC6 is a candidate channel involved in receptor-stimulated cation currents in A7r5 smooth muscle cells. American Journal of Physiology Cell Physiology 282:C347−C359 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00283.2001

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[139]

|

Soboloff J, Spassova M, Xu W, He LP, Cuesta N, Gill DL. 2005. Role of endogenous TRPC6 channels in Ca2+ signal generation in A7r5 smooth muscle cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 280:39786−39794 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506064200

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[140]

|

Kola PK, Oraegbuna CS, Lei S. 2024. Ionic mechanisms involved in arginine vasopressin-mediated excitation of auditory cortical and thalamic neurons. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience 130:103951 doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2024.103951

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[141]

|

Colović MB, Krstić DZ, Lazarević-Pašti TD, Bondžić AM, Vasić VM. 2013. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: pharmacology and toxicology. Current Neuropharmacology 11:315−335 doi: 10.2174/1570159X11311030006

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[142]

|

Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL. 2007. Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104:5163−5168 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700293104

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[143]

|

Oğlak SC, Aşır F, Korak T, Aşır A, Yılmaz EZ, et al. 2025. Reduced M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor expression in gestational diabetes mellitus: implications for placental dysfunction and vascular regulation. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 38:2521799 doi: 10.1080/14767058.2025.2521799

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[144]

|

Marsh SA, Heslep N, Paronis CA, Bergman J, Negus SS, et al. 2025. Xanomeline treatment attenuates cocaine self-administration in rats and nonhuman primates. Neuropharmacology 281:110686 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2025.110686

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[145]

|

Liu W, Putnam AL, Zhou XY, Szot GL, Lee MR, et al. 2006. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 203:1701−11 doi: 10.1084/jem.20060772

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[146]

|

Bendall SC, Simonds EF, Qiu P, Amir el AD, Krutzik PO, et al. 2011. Single-cell mass cytometry of differential immune and drug responses across a human hematopoietic continuum. Science 332:687−96 doi: 10.1126/science.1198704

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[147]

|

Chistiakov DA, Killingsworth MC, Myasoedova VA, Orekhov AN, Bobryshev YV. 2017. CD68/macrosialin: not just a histochemical marker. Laboratory Investigation 97:4−13 doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2016.116

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[148]

|

Li S, Li J, Al Faruque H, Shami P, Knoechel B, et al. 2025. Self-assembling multi-antigen T cell hybridizers for precision immunotherapy of multiple myeloma. Advanced Healthcare Materials 14:e02156 doi: 10.1002/adhm.202502156

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[149]

|

Furka Á. 2022. Forty years of combinatorial technology. Drug Discovery Today 27:103308 doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2022.06.008

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[150]

|

Hajduk PJ, Greer J. 2007. A decade of fragment-based drug design: strategic advances and lessons learned. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 6:211−219 doi: 10.1038/nrd2220

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[151]

|

Shi B, Zhou Y, Li X. 2022. Recent advances in DNA-encoded dynamic libraries. RSC Chemical Biology 3:407−419 doi: 10.1039/D2CB00007E

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[152]

|

Clark MA, Acharya RA, Arico-Muendel CC, Belyanskaya SL, Benjamin DR, et al. 2009. Design, synthesis and selection of DNA-encoded small-molecule libraries. Nature Chemical Biology 5:647−54 doi: 10.1038/nchembio.211

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[153]

|

Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, et al. 2020. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 181:281−292.e6 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[154]

|

Wrapp D, Wang N, Corbett KS, Goldsmith JA, Hsieh CL, et al. 2020. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 367:1260−63 doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[155]

|

Altman JD, Moss PAH, Goulder PJR, Barouch DH, McHeyzer-Williams MG, et al. 1996. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science 274:94−96 doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.94

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[156]

|

Jiang B, Koo SH, Ang DSW, Ang TL, Lee HZ, et al. 2026. Development of a real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay for simultaneous detection of Helicobacter pylori infection and genetic mutations associated with clarithromycin resistance: A single-center, cross-sectional study from Singapore. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 114:117131 doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2025.117131

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[157]

|

Schedin F, Geim AK, Morozov SV, Hill EW, Blake P, et al. 2007. Detection of individual gas molecules adsorbed on graphene. Nature Materials 6:652−5 doi: 10.1038/nmat1967

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[158]

|

Josefsen LB, Boyle RW. 2012. Unique diagnostic and therapeutic roles of porphyrins and phthalocyanines in photodynamic therapy, imaging and theranostics. Theranostics 2:916−66 doi: 10.7150/thno.4571

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[159]

|

Lee KY, Mooney DJ. 2012. Alginate: properties and biomedical applications. Progress in Polymer Science 37:106−126 doi: 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2011.06.003

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[160]

|

Stuart MAC, Huck WTS, Genzer J, Müller M, Ober C, et al. 2010. Emerging applications of stimuli-responsive polymer materials. Nature Materials 9:101−113 doi: 10.1038/nmat2614

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[161]

|

Cho JH, Collins JJ, Wong WW. 2018. Universal Chimeric antigen receptors for multiplexed and logical control of T cell responses. Cell 173:1426−1438.e11 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.038

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[162]

|

Röthlisberger P, Hollenstein M. 2018. Aptamer chemistry. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 134:3−21 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2018.04.007

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[163]

|

Giraudet R, Laroche A, Chalopin B, Dubois S, Correia E, et al. 2025. Immunogenicity of single-chain antibodies: germlining of a VHH lowers T-cell activation from epitopes in FR2 and CDR regions. mAbs 17:2571406 doi: 10.1080/19420862.2025.2571406

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[164]

|

Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, et al. 2020. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. The New England Journal of Medicine 383:2603−15 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[165]

|

Millán-Martín S, Guapo F, Carillo S, Mistarz UH, Cook K, et al. 2026. Characterisation of small RNA-based therapeutics and their process impurities by fast and sensitive liquid chromatography high resolution mass spectrometry. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 268:117097 doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2025.117097

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[166]

|

Cheng L, Wang T, Pi R, Zhao P, Chen J. 2025. A novel derivative of rhein overcomes temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma by regulating SOX9 through m6A methylation. Brain Research 1866:149889 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2025.149889

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[167]

|

Illuminati D, Foschi R, Marchetti P, Zanirato V, Fantinati A, et al. 2025. Multi-step synthesis of chimeric nutlin-DCA compounds targeting dual pathways for treatment of cancer. Molecules 30:3908 doi: 10.3390/molecules30193908

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[168]

|

Xie SS, Lan JS, Wang X, Wang ZM, Jiang N, et al. 2016. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel donepezil-coumarin hybrids as multi-target agents for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 24:1528−1539 doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.02.023

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[169]

|

Zheng W, Zhao Y, Luo Q, Zhang Y, Wu K, Wang F. 2017. Multi-targeted anticancer agents. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 17:3084−3098 doi: 10.2174/1568026617666170707124126

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[170]

|

Assaraf YG, Brozovic A, Gonçalves AC, Jurkovicova D, Linē A, et al. 2019. The multi-factorial nature of clinical multidrug resistance in cancer. Drug Resistance Updates 46:100645 doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2019.100645

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[171]

|

Cohen L, Livney YD, Assaraf YG. 2021. Targeted nanomedicine modalities for prostate cancer treatment. Drug Resistance Updates 56:100762 doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2021.100762

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[172]

|

Perona MTG, Waters S, Hall FS, Sora I, Lesch KP, et al. 2008. Animal models of depression in dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine transporter knockout mice: prominent effects of dopamine transporter deletions. Behavioural Pharmacology 19:566−574 doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32830cd80f

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[173]

|

Fathullahzadeh S, Mirzaei H, Honardoost MA, Sahebkar A, Salehi M. 2016. Circulating microRNA-192 as a diagnostic biomarker in human chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Gene Therapy 23:327−332 doi: 10.1038/cgt.2016.34

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[174]

|

Honardoost MA, Kiani-Esfahani A, Ghaedi K, Etemadifar M, Salehi M. 2014. miR-326 and miR-26a, two potential markers for diagnosis of relapse and remission phases in patient with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Gene 544:128−133 doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.04.069

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[175]

|

Wang Y, Zhang S, Li F, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, et al. 2020. Therapeutic target database 2020: enriched resource for facilitating research and early development of targeted therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Research 48:D1031−D1041 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz981

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[176]

|

Avillach P, Mougin F, Joubert M, Thiessard F, Pariente A, et al. 2009. A semantic approach for the homogeneous identification of events in eight patient databases: a contribution to the European eu-ADR project. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 150:190−194 doi: 10.3233/978-1-60750-044-5-190

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[177]

|

Avillach P, Joubert M, Thiessard F, Trifirò G, Dufour JC, et al. 2010. Design and evaluation of a semantic approach for the homogeneous identification of events in eight patient databases: a contribution to the European EU-ADR project. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 160:1085−1089 doi: 10.3233/978-1-60750-588-4-1085

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[178]

|

Simon J, Dos Santos M, Fielding J, Smith B. 2006. Formal ontology for natural language processing and the integration of biomedical databases. International Journal of Medical Informatics 75:224−231 doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.07.015

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[179]

|

Bodenreider O. 2004. The Unified Medical Language System (UMLS): integrating biomedical terminology. Nucleic Acids Research 32:D267−D270 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh061

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[180]

|

Schnell R, Bachteler T, Reiher J. 2009. Privacy-preserving record linkage using Bloom filters. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 9:41 doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-9-41

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[181]

|

Schnell R, Borgs C. Building a National Perinatal Data Base without the Use of Unique Personal Identifiers. 2015 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshop (ICDMW), 2015, Atlantic City, NJ, USA. USA: IEEE. pp. 232−239 doi: 10.1109/ICDMW.2015.19

|

|

[182]

|

Brown EG. 2003. Methods and pitfalls in searching drug safety databases utilising the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA). Drug Safety 26:145−158 doi: 10.2165/00002018-200326030-00002

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[183]

|

Djennaoui M, Ficheur G, Beuscart R, Chazard E. 2015. Improvement of the quality of medical databases: data-mining-based prediction of diagnostic codes from previous patient codes. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 210:419−423 doi: 10.3233/978-1-61499-512-8-419

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[184]

|

Voss EA, Makadia R, Matcho A, Ma Q, Knoll C, et al. 2015. Feasibility and utility of applications of the common data model to multiple, disparate observational health databases. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 22:553−64 doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocu023

CrossRef Google Scholar

|

|

[185]

|

Stadler CB, Lindvall M, Lundström C, Bodén A, Lindman K, et al. 2021. Proactive construction of an annotated imaging database for artificial intelligence training. Journal of Digital Imaging 34:105−115 doi: 10.1007/s10278-020-00384-4

CrossRef Google Scholar

|