-

Agriculture has undergone many revolutions in its long journey. For example, the domestication and cultivation of animals and plants started a few thousand years ago, the organized implementation of crop rotations and other improvements in farming practices started a few hundred years ago, and the 'green revolution' with methodical breeding and the increasing popularity of man-made fertilizers and pesticides started a few decades ago. Currently, one of the key sectors that strategically contribute to achieving food security is agriculture. To sustainably feed the increasing global population in the face of limited land resources and increasing climatic and environmental constraints, it is of utmost importance to boost crop and livestock production efficiently to meet the world's rising food demand[1−3].

In the decades between 1940 and 1960, the Ford Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, and other major organizations spearheaded and generously funded programs for agricultural research, extension, and infrastructure development that resulted in the 'Green Revolution', a global alteration of agriculture that drastically boosted agricultural production[4]. However, to practice sustainable agriculture, it is now essential to adopt modern technologies such as remote sensing, the Internet of Things (IoT), agricultural robots, farming mechanization, cell phones, computers, etc. These modern technologies that have emerged with traditional agricultural knowledge are anticipated to uplift global agricultural production by solving critical issues in soil and farming practices. Currently, groundbreaking ideas in precision agriculture, smart agriculture, and sustainable agriculture are mentioned in several articles and journals that conceptually merge agriculture with modern technologies in an environmentally friendly way[5,6]. The application of advanced technologies such as robots, sensors, cloud computing (CC), big data analytics, and artificial intelligence (AI) will compel modern farms and agricultural enterprises to operate differently. These developments should enable firms to operate more economically, effectively, and sustainably[7].

In recent years, there have been several advances in technological intervention in agriculture. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) or drones with autonomous flight control together with lightweight and powerful multispectral, hyperspectral, and thermal infrared (TIR) cameras are being increasingly used to determine the biomass accumulation and fertilization status of crops[8−11], detect weeds[12], detect crop macronutrient (calcium, magnesium, potassium, sodium, etc.) variations and/or deficiencies early[13], quantify abiotic stress[2], estimate crop yield[14], determine sodicity and drought tolerance[15], and determine crop physiological performance[16]. Furthermore, evidence exists on how high-throughput phenotypic traits extracted from these powerful optical, thermal, and multispectral sensors are integrated with various machine-learning predictive algorithms, such as support vector machines, agglomerative clustering, and decision trees, which enable researchers to distinguish between plant diseases and/or biotic stress[17], genotypic water stress classification[18], crop biomass and yield prediction[19], etc. In addition to UAVs and/or close-range proximal imaging, computer simulation and geostatistical approaches using multicomponent metrics can be employed to improve the estimation of crop water use for better crop health discrimination and could provide useful insights into improved farm management[20].

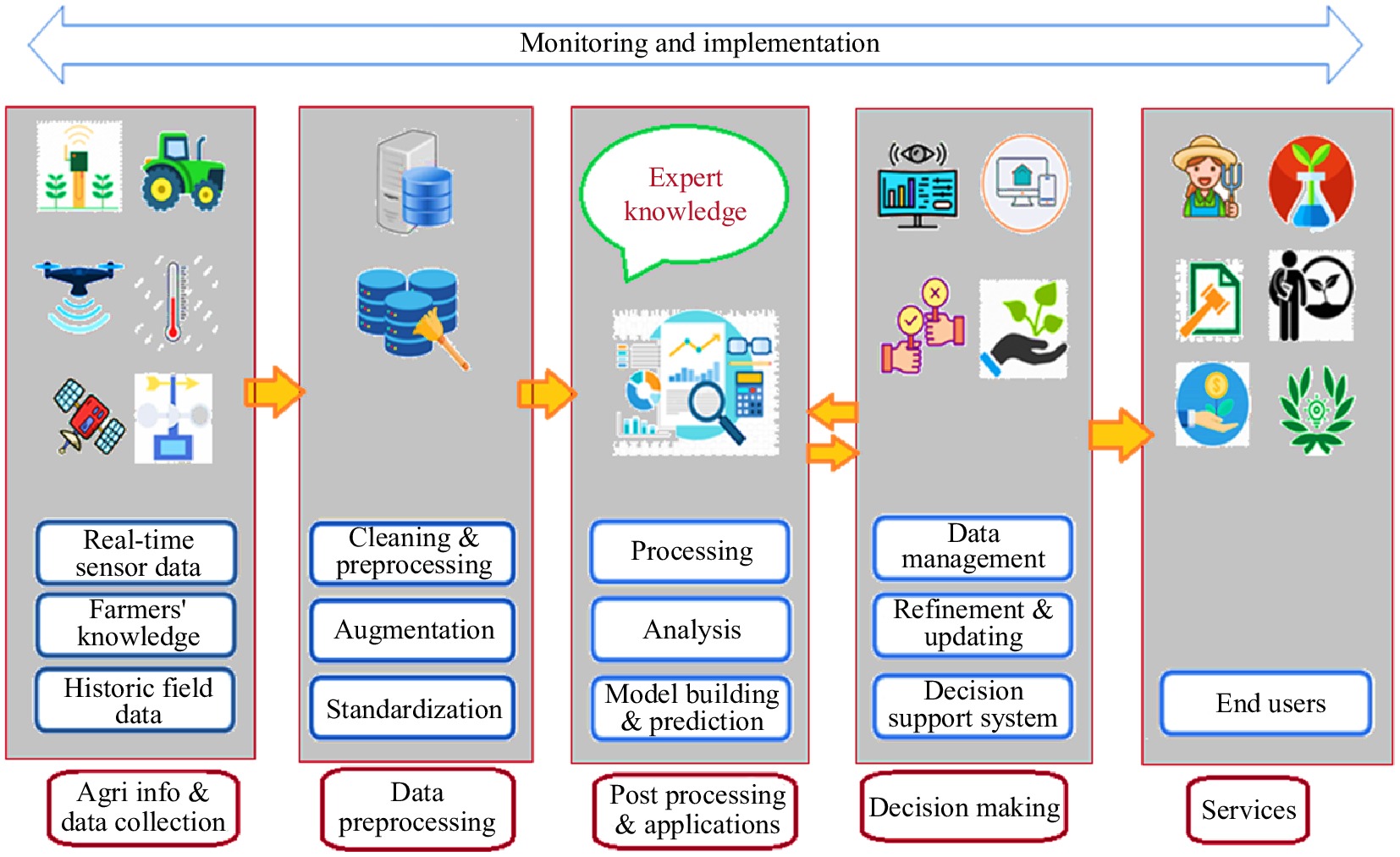

Cattle herd management is made possible by virtual fence technologies, which rely on distant sensing signals and sensors or actuators mounted on cattle[21]. Different robots assist farmers in milking their cattle[22], and removing weeds from crop fields[23]. Furthermore, the Cortana Intelligence Suite from Microsoft is being used globally to identify the best times to plant crops[24]. Collectively, these technological advancements form an innovative transformation that will cause significant shifts in agricultural methods that provide improved decision tools starting from data collection in the field to sustainable food security (Fig. 1). A previous study[25] reported that the present scenario is true for farming in both developed and developing nations, where information and communications technology (ICT) installations (such as the use of cell phones and Internet accessibility), computer simulation models and/or virtual and augmented reality are gaining traction quickly and have the potential to change the game in the future to achieve sustainability in agricultural practices, including climate-smart agriculture.

Figure 1.

An overview of the hierarchy of digital agricultural systems from data collection in the field to decision-making and services (from left to right), modified from Amiri-Zarandi et al.[26].

Considering the growing need for the digitalization of agriculture and/or agri-food industries, researchers across the world are developing tools, devices, smart sensors, machines, etc., that can be deployed at the canopy to farm level to assist with data-driven decision-making toward sustainable agriculture and farm management practices. However, there is a knowledge gap on how these different digital tools and/or techniques are being used to make informed decisions in agriculture and land management. Hence, summarizing the mechanisms, applications, and challenges of some of the tools and how they improve decision-making in agricultural sustainability is of great interest across agro-communities and agri-food industries. In the present review, we present our current understanding of how digital technologies provide viable solutions to agricultural innovations and secure future food demand from agricultural products. Specifically, we started our discussion with the digital revolution in agriculture and current needs by focusing on state-of-the-art digital tools and their mechanisms and applications in agriculture and how these technologies and tools will transform agriculture more productively and sustainably. In addition, dimensions, limitations, and future opportunities are also discussed. It is anticipated that this review will benefit researchers by providing useful information on digital agriculture and automation and offering recommendations to help stakeholders make a smooth transition to the digitalization of agriculture.

-

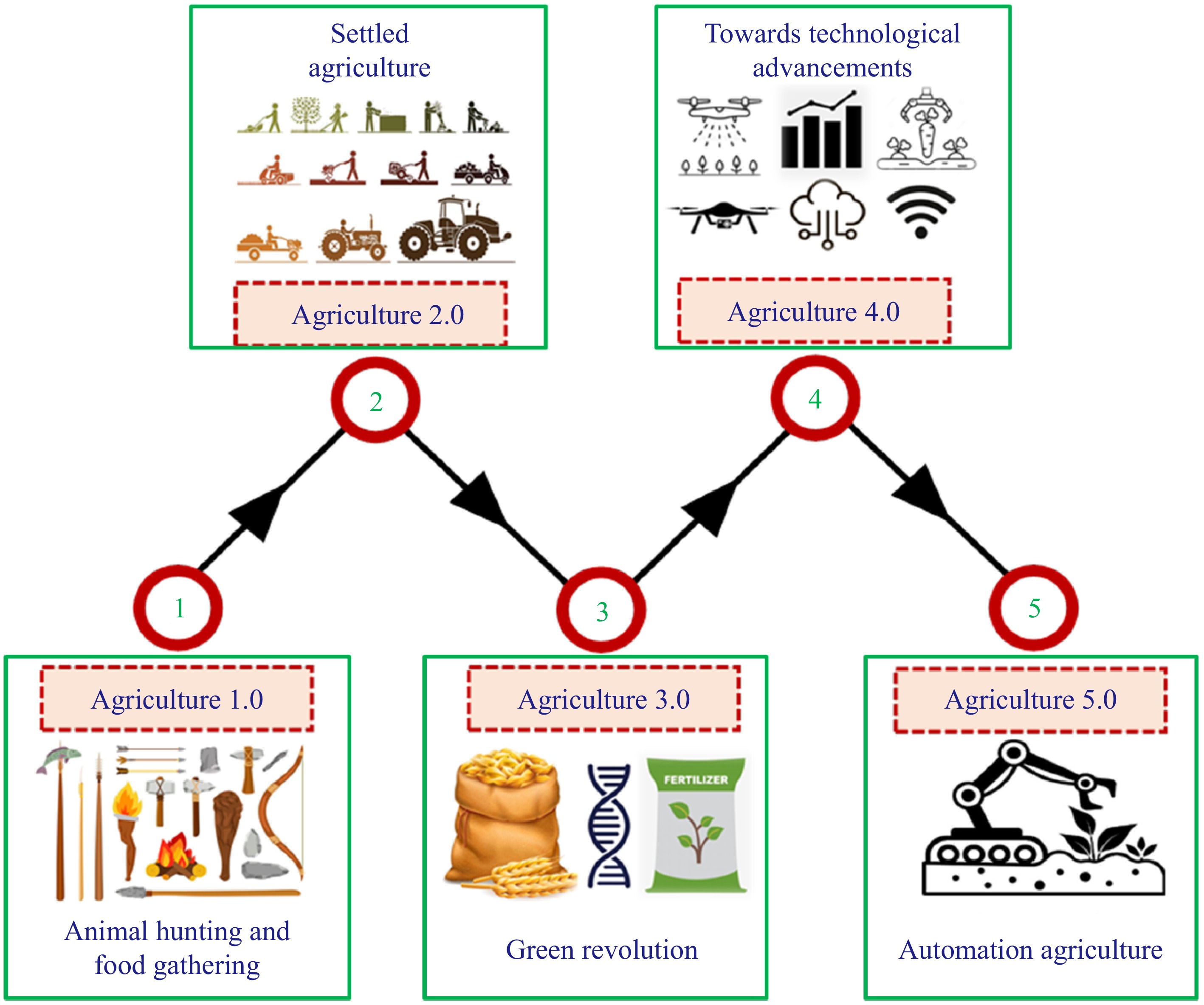

The 'First Agricultural Revolution' or 'Agriculture 1.0' introduced changes in human occupation from being an animal hunter to being a farmer (Fig. 2). This first phase of the revolution continued up to the technological innovations that came into existence during the British period[27]. Agriculture 1.0 provides poor yields but sufficient food for people and requires massive amounts of human resources to manually control agricultural pests (such as plant diseases, weeds, and various plagues, both vertebrates and invertebrates). This method was used from ancient times until approximately 1950[28]. Agriculture 2.0 began in the late 1950s with the advent of synthetic pesticides and specialized tools to tackle common agricultural pests (Fig. 2). At that time, agriculture began to advance economically to produce more food for less money or to become more industrialized[28]. Agriculture mechanization started in this phase, and different kinds of machines for various agricultural operations, such as Jethro Tull's seed drill, were used for easy sowing[29]. The 'Third Agricultural Revolution', or 'Agriculture 3.0', involves the Green Revolution era, when agricultural production reached its highest peak among all the past revolutions. Norman Borlaug's enhanced wheat varieties and the advanced rice strains from the International Rice Research Institute, combined with significant investments in irrigation expansion and agricultural chemicals by development agencies, led to the transformative 'Green Revolution'. During the postwar period, mechanization increased with the introduction of new and high-yielding varieties of seed (mainly for grain crops such as wheat and rice) and increased use of fertilizers, pesticides, and weedicides to lower agricultural losses and increase productivity[27]. The 'Fourth Agricultural Revolution' or 'Agriculture 4.0' (Fig. 2) advocated employing new technology and data-driven modeling as crucial tools for making decisions and managing agricultural systems and was developed at the close of the 20th century[28]. Precision agriculture was developed as a result of this revolutionary idea. Food quality was raised, pesticide costs and environmental effects were reduced, and agricultural protection activities were optimized through the use of telematics, global navigation satellite systems (GNSSs), mechanical guiding, and sensor devices[30]. Thereafter, sensors, mobile telephony, embedded systems, CC, IoT, and big data were integrated with onboard actuators, intelligent sprayers, and autonomous machinery to support the precision crop protection paradigm application within the context of Agriculture 4.0[31]. The 'Fifth Agricultural Revolution', or 'Agriculture 5.0', which is the latest innovation in this evolutionary cycle (Fig. 2), intends to facilitate the development of a new generation of intelligent crop management that uses the most advanced robotics, AI systems, and machine learning algorithms to enable automated decision-making, unmanned operations, and a decrease in the amount of human participation[32]. These cutting-edge technologies, such as UAVs or drones, the IoT, CC, robotics, sensors, nanotechnology, AI, and machine learning (ML), are being advanced toward their full operational phase to support the digitalization of agriculture, aquaponics, cellular agriculture, gene editing, the manufacture of artificial food (like protein), etc.

-

The concept of digitalization in agriculture started with Agriculture 4.0, which includes different ideas, techniques, and theories[33]. Before the fourth revolution, agricultural farms and technologies were mainly labour-intensive, tedious, driven by traditional knowledge and mechanisms, and mostly reliant on chemical fertilizers, fungicides, and pesticides. Currently, this basic concept and framework in agriculture are advancing with technological interventions such as different sensor devices, aerial devices, robots, AI global positioning systems (GPSs), geographical information systems (GISs), and remote sensing (RS), which are increasingly used for the digitalization of agriculture[34−36]. The primary goal is to make better farming decisions to produce sufficient nutritious food to provide food for the world's growing population in the face of climatic constraints, with the equally essential goal of preventing the deterioration of the ecosystems on which we depend for survival.

In the coming decades, global agriculture may face two major challenges. First, as noted by Hoegh-Guldberg et al.[37], climate change has a negative impact on agricultural systems, leading to unstable farming practices[38], and irregular crop seasons in large productive areas due to extreme heat and water scarcity[39,40]. These factors invariably contribute to the emergence of new invasive pests or exacerbate already existing pests. The second goal is to ensure food security by decreasing the use of agrochemicals and implementing strict restrictions throughout the whole agricultural supply chain, all while producing enough food to support an expanding human and animal population[41]. To cope with these challenges, transdisciplinary studies and interdisciplinary expertise are needed. In light of this impending future, digital technologies must offer innovative solutions built using cutting-edge technology advancements such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, which can potentially interact with the soil-crop-environment at the farm scale and could bridge the gaps between farming practices and agricultural production to provide accurate information to farmers and decision-makers.

These technological advancements are making agriculture more sustainable with the minimum use of water and chemical fertilizers across the field[42,43]. These modern innovations and digitalization are expected to lead the agricultural sector to become a more profitable and environmentally friendly industry. By employing a variety of cutting-edge technologies that strengthen innovative approaches at all points along the agricultural production chain, Agriculture 4.0 and 5.0 transform old farming practices and global agriculture tactics into an efficient value chain. To do so, it is necessary to convert systematic classical agriculture into a smarter one that relies on facts made accessible by a variety of developing technologies[44]. Although large-scale sectoral transitions typically take more than a decade or perhaps many decades for the dissemination of new concepts and innovations, such as precision farming methodologies, they are not always rapid[45]. For the entire world to profit from the opportunities that lie ahead of this new agricultural revolution, it is crucial to comprehend the constraints of the adoption of digital technologies concerning socioeconomic and behavioral changes, which must be addressed before their implementation[46]. However, before discussing the constraints, socioeconomic, and behavioral perspectives, it is important to discuss the data-driven digital tools, their components and mechanisms, and their adoption for modern farming practices, as described below.

-

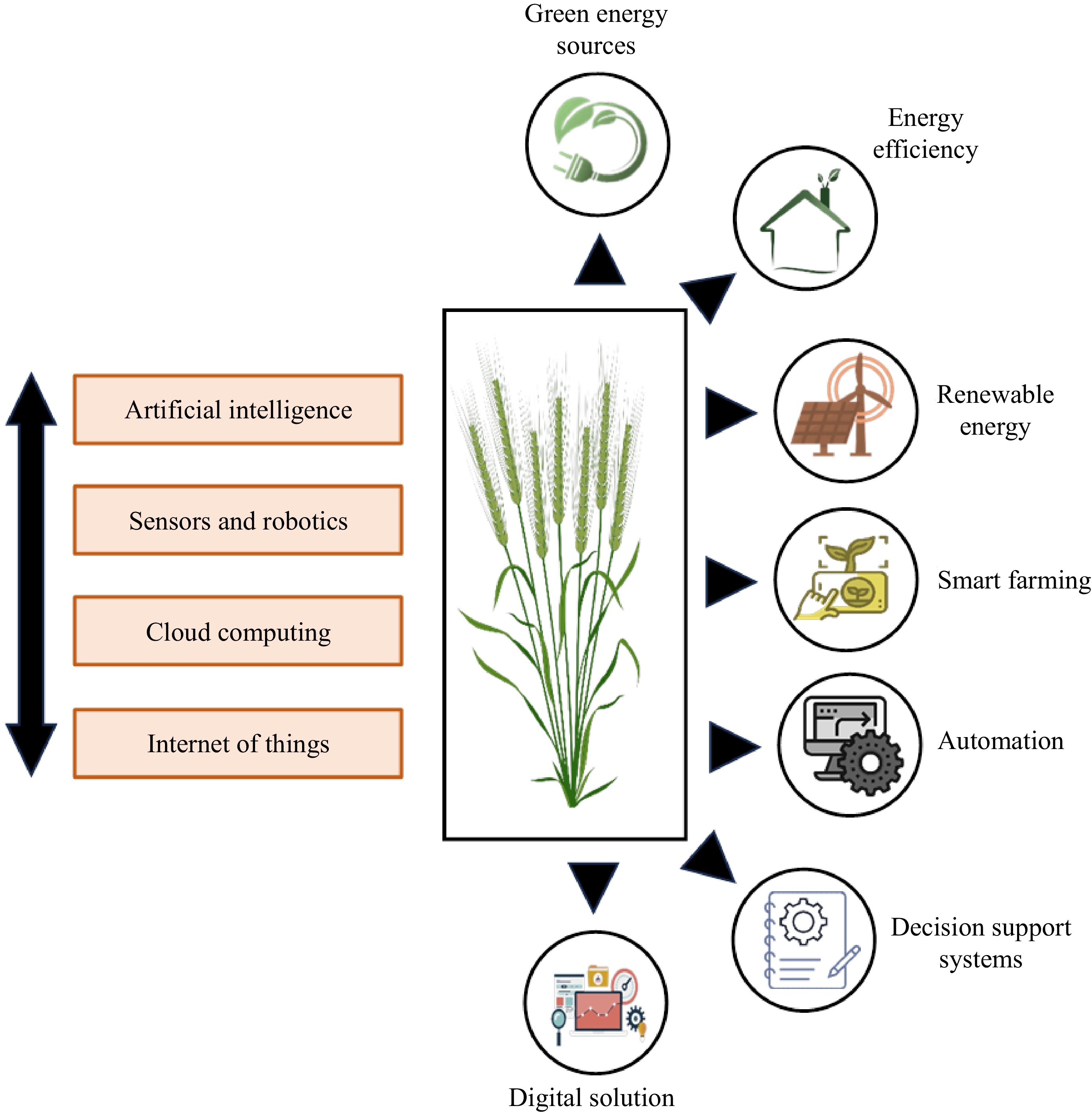

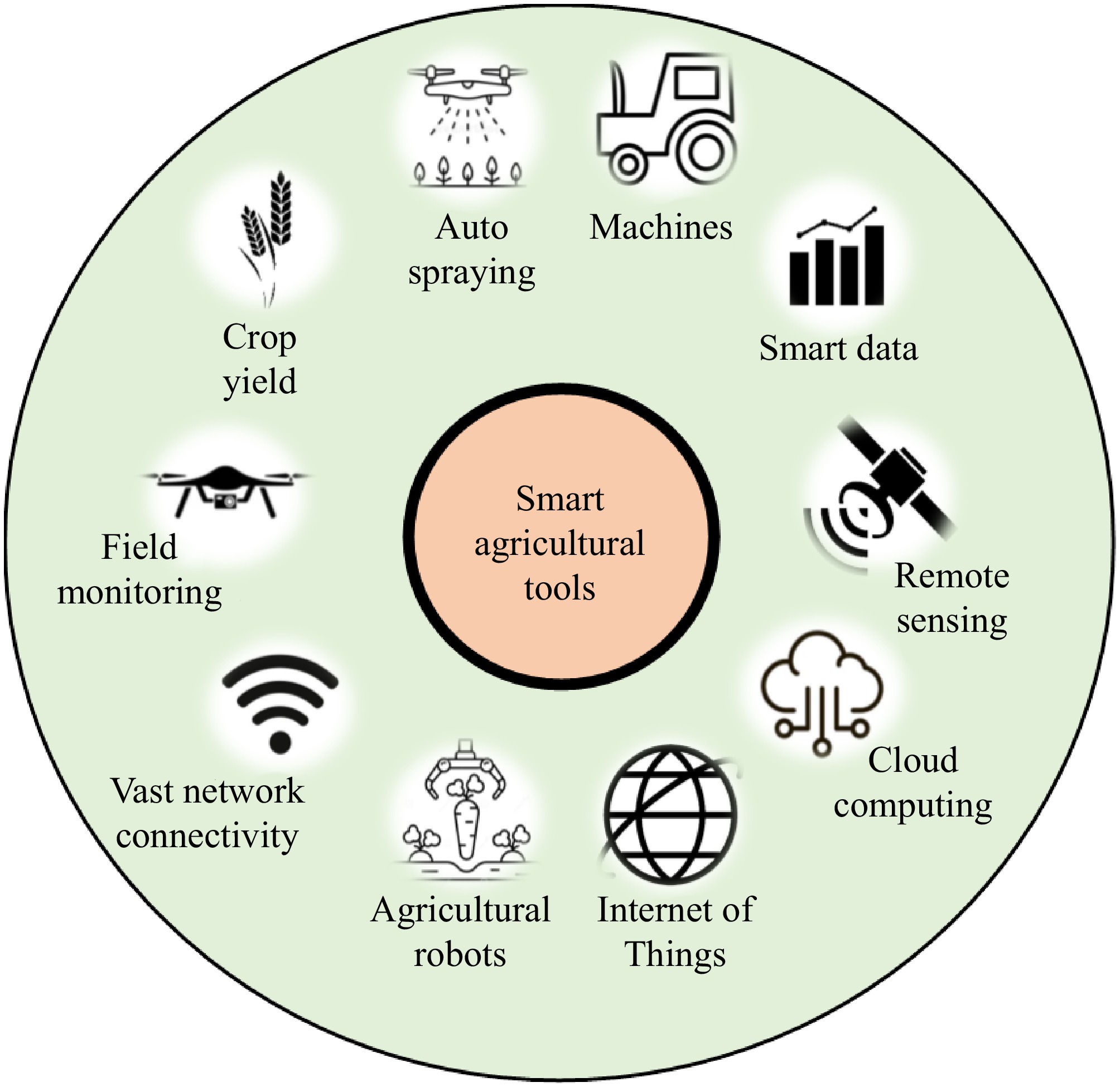

The adoption of a variety of novel hardware, software, smartphone applications, sensor-based devices, and data-driven apps on farms is what is meant by the term 'digital agriculture'[47]. Agriculture's digitalization primarily seeks to enhance connectivity among devices, gather and utilize more data from farms, and create provisions that are suitable for processing data on farms[48]. Figure 3 depicts the linkage between smart technologies and sustainable agricultural practices, where AI, sensors, IoT, cloud computing, etc., are used to collect and extract useful information from soil and crops to provide informed decisions on sustainable agriculture and land management practices. This includes the use of information technologies for farm operations to track various parameters founded on the gathering of a series of big data, which is capable of making it possible to raise crops with operational efficiency while lowering the cost of cultivation and reducing the use of agricultural pesticides and unnecessary fertilizers[49−51]. The various tools used for digital agriculture are depicted in Fig. 4, and their applicability is summarized below.

Internet of Things (IoT), vast network connectivity, and cloud computing

-

The huge network of interconnected machines, sensors, gadgets, and computer devices that make up the Internet of Things (IoT) and are capable of performing RS surveillance[52], and the data generated from these machines/sensors, are stored and retrieved through the cloud. The IoT, which may be used to measure and manage the physical world, has been the result of the convergence of various technologies for several decades. According to Abbasi et al.[53], IoT devices in physical strata can efficiently monitor and collect information about environmental and crop factors on agricultural farms, including the air-canopy temperature, humidity, pH, water level, colour of the leaves, and new leaf weight. The network is used to transfer these data via appropriate communication media considering the size, location, and farming method of the field. CC methods are used in the service stratum for conserving these data. The phrase CC has been utilized as an illustration of adaptable computer system resources accessible via the internet[54]. Currently, a new approach termed edge computing is computing infrastructure located closer to data sources, and this approach has entered the market with the promise of transforming machine-based data into actionable information[55]. Furthermore, the application stratum uses these data to create sophisticated programs that farmers, agricultural professionals, and supply chain specialists may utilize to increase the efficiency, and effectiveness of farm monitoring. Microprocessors have become more powerful while also being smaller and less expensive during the past two decades, making them more widely available and encouraging the creation of a wide range of IoT solutions[56]. Nectar Agriculture funded a senior capstone project at the University of North Texas (USA), which aimed to develop web-enabled control systems for crop adaptation to the environment[57]. IoT platforms such as IBM's Watson are implementing ML to drone or sensor data for converting management systems into actual AI systems[7], etc., and can be used as example cases of new generation IoT in agriculture.

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

-

One of the main fields of study in computer science is AI, which is increasingly used to solve issues that traditional computing systems and humans are unable to adequately accomplish. The term AI was first used in 1956 by John McCarthy[57], and it has since been researched. AI is currently widely used in a wide range of applications, including commercial operations, robots, and games. McKinion and Lemmon first suggested the use of AI techniques in crop management in their paper 'Expert Systems for Agriculture' published in 1985[58]. Precise details of each circumstance may now be captured using AI techniques, and the most appropriate answer is provided. For example, for cotton crop management, two expert systems named COTFLEX were introduced by Stone & Toman[59], and COMAX was introduced by Lemmon[60] in recent decades. One of the main forces behind the digitization of agriculture is AI, particularly in the areas of ML and deep learning (DL), especially when it is coupled with CC, the IoT, and big data[61]. These innovations may improve real-time monitoring, crop harvesting, processing, and marketing, as well as crop yield. Currently, many AI tools are available for several agricultural operations, even for different crops, specifically for soil and irrigation management[62], weed management[63], pest management[64], disease management[65], agricultural product monitoring, storage control[66], and yield prediction[67].

Agricultural robotics and machines

-

The term 'robotics' was first proposed by Isaac Asimov at the time of his famous 'Three Laws of Robotics' in 1942[68]. According to a previous study[69], agricultural robots are devices and machinery designed for use in agriculture. A rising number of agricultural robot genres have been developed, and as actual needs for labor-saving and efficient agricultural production have grown, so too have their intended uses. Various types of robots are being utilized in agricultural operations to increase the efficiency of each phase. Field robots are autonomous, mechatronic, mostly mobile, decision-making machines that can carry out a variety of agricultural chores either fully or partially automatically[70]. These robots can easily help in tilling fields, seed sowing, data recording, crop harvesting, and other operations regularly. Tillage robots are used to cultivate fields without the help of labourers, thus exempting farmers from this heavy and tedious operation. New software was developed for tilling robots to maintain a balance between existing robots and software systems[71]. In addition to regular tillage robots, robotic tractors significantly aid in tilling operations. Sesam 2, a new electric robot tractor manufactured by John Deere, can generate up to 300 kW (400 hp) of power and is used for both tilling and harvesting operations[72]. Some robots also help in precise sowing operations, such as seed sowing and microdose fertilizer applications[73], and complete automated seed sowing robots managed by an IoT framework[74]. Even robots can contribute to crop protection measures in the field. A multipurpose pesticide application robot has been introduced using a fuzzy control system that can easily search for infected plants and apply the pesticide in the required amount[75]. Furthermore, a field-based, high-throughput, mobile robotic device was installed at the University of Saskatchewan (Canada) for the surveillance of canola plants[76]. Paddy harvesters have been very popular and widely used for several years, but now, with the help of robotics, harvesters for different crops are also coming on the market. This reduces the labour intensiveness in harvesting operations. For example, an automated maize harvester was proposed by Geng et al.[77], and a robotic swarm harvester was introduced by Pooranam & Vignesh[78] for large-scale threshing, cleaning, and harvesting operations. Even robots and robotic systems are designed to monitor cattle performance[79], and for automatic milking[80] with the help of high-profile cameras and algorithms.

Unmanned ground and aerial vehicles for smart data acquisition

-

Unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs) and UAVs are agricultural robots that are either human operated or fully automated in nature. UGVs can work on the ground with or without the assistance of a human operator. For example, a previous study[81] reported that for small to medium farms, close-range proximal multispectral sensors can be easily carried by UGVs for effective monitoring and quantification of crop growth dynamics. Generally, UGVs are made up of a platform for manipulators and locomotive apparatuses, sensors for mapping, a controlling system, a UI for the control system, a connection for device-to-device information sharing, and a framework for combining hardware and software agents[82]. They are primarily used for sowing operations[83], weed control[84], pesticide spraying[85], artificial pollination[86], crop treatment[87], and harvesting[88] on small- to medium-sized farms. However, limitations exist in using UGVs for mapping agricultural farms at large field and/or regional scales due to their limited speed, small field-of-view, and weak communication, where UAVs can address these issues effectively[89]. UAVs or agricultural drones can be of various types, such as fixed-wing or planes, single-rotor or helicopters, hybrid systems or vertical take-off and landing, or multirotor or drone[53]. Drones (a type of multirotor technology) are popular in the agriculture industry because of their mechanical ease and highly advanced plate control system[90]. UAVs can carry powerful sensors, such as multispectral, red green blue (RGB), thermal, and hyperspectral sensors, for effective monitoring of crop physiological growth dynamics, water status, aboveground biomass, yield variations, etc., across seasons on large farms[16,18,19]. A recent study highlighted the superior potential of integrated UAV thermal and multispectral imaging and derived physiological traits for the accurate quantification of drought tolerance of various wheat cultivars in Australian water-limited environments[15]. In addition, UAV imaging can help farmers analyze the soil quality and even the nutrient level of the land, which helps them determine the sowing time and irrigation management. Although these UAV-based sensing and imaging technologies and accurate data acquisition at farm scales provide viable solutions to many complex agricultural problems, the challenge exists in handling and critically processing these big imaging data across the crop cycle and farms to provide vital information on seasonal crop growth dynamics, stress, yield potential, etc. To address this, researchers are developing more advanced algorithms, tools, and software-based pipelines that could be integrated with UAV-based imaging and high-throughput phenotyping to manage large amounts of imaging data for multiple crops and farms at a time. For example, a recent study[91] developed a UAV image extraction pipeline using an executable software code, i.e., 'Xtractori', for rapid quantification of morphological and physiological crop traits to accurately estimate crop growth and phenology across large agricultural farms (Fig. 5). They also reported that this software code can handle complex interactions of crop physiological traits extracted from multiple UAV images of different crops and their cultivars (Fig. 6). The improved quantification of the complex interactions of crop traits across seasons and different crop/cultivar types is essential for understanding phenological progress, stress, and/or yield variations across farms and environments.

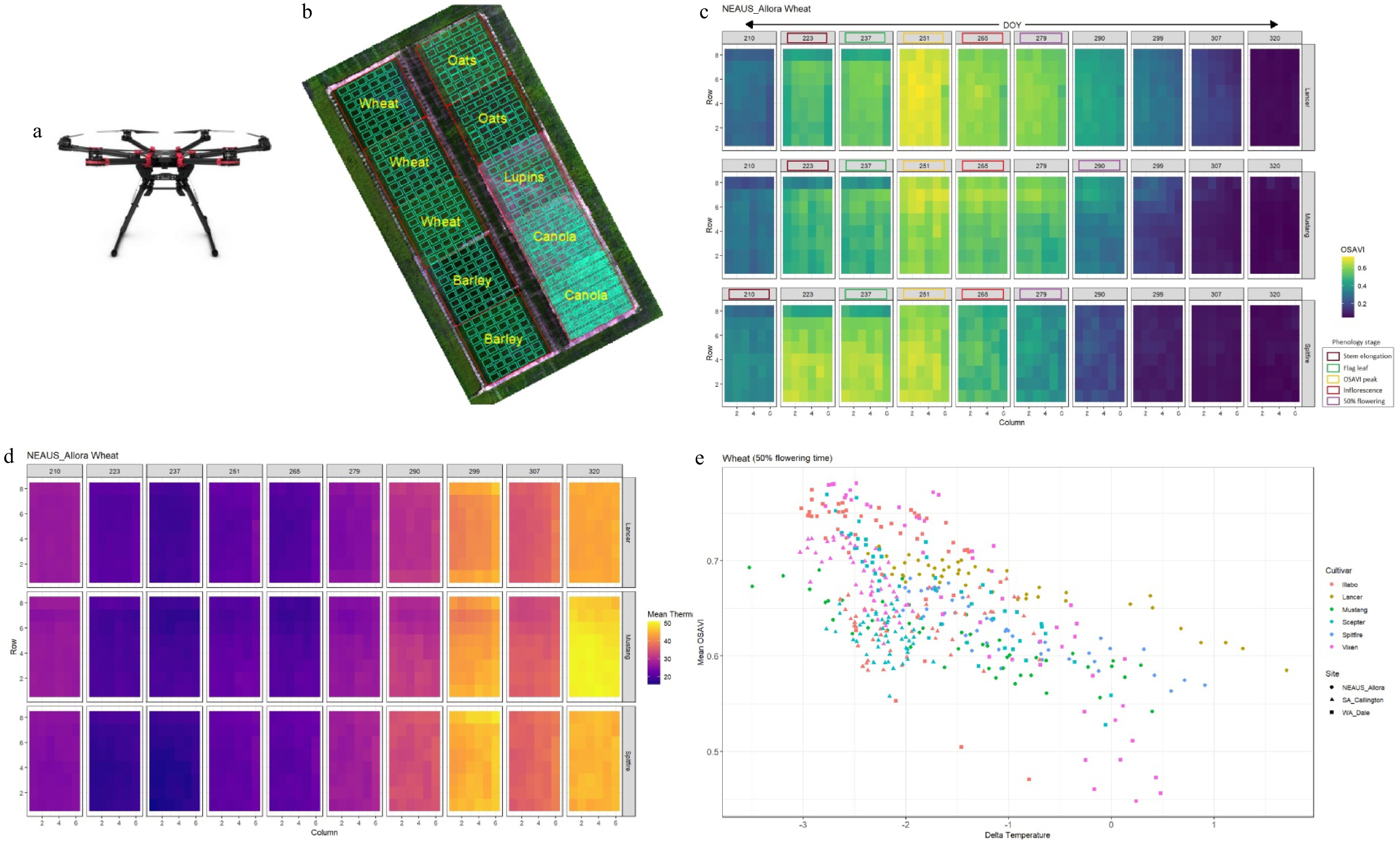

Figure 5.

(a) A UAV platform (DJI Matrice Hexacopter). (b) A composite five-band (blue, green, red, near-infrared, and longwave thermal infrared) multispectral image of a large multicropping field in Australia captured using the UAV. Each plot (60 m × 60 m) represents each crop and its different cultivars. The green rectangular boxes within each plot represent the gridded (6 m × 10 m) profile of each crop and/or cultivar to determine spatial variability within each plot (60 m × 60 m). (c) The 'Xtractori' outcome derived from the UAV-multispectral images over the season shows spatial and temporal variations (across the season on the day of year (DOY)) in crop greenness and vigour based on an optimized soil adjusted vegetation index (OSAVI) among different cultivars (Lancer, Mustang, and Spitfire) of wheat in a northeastern Australian field (NEAUS). A number of vegetation and soil indices, including land surface and canopy temperatures, can be extracted from the 'Xtractori' program. Among others, OSAVI was used as an example case. The colour scale of the OSAVI (right side) indicates a value ranging between 0 and 1. When OSAVI > 0.5 indicates adequate crop greenness and vigour, an OSAVI < 0.5 indicates relatively low greenness. Phenology observations of the cultivars (stem elongation, flag leaf, 50% flowering, etc.) were mapped using different colours on the spatiotemporal gridded OSAVI profile to determine the relationships between phonological changes and changes in greenness and vigour of the culivars/crop across the season (DOYwise). (d) The 'Xtractori' program was effectively used on seasonal UAV-multispectral images to determine spatiotemporal variations (DOYwise) in canopy temperature dynamics (mean thermal) among different cultivars of wheat in the NEAUS field. (e) Integrated UAV-multispectral imagery and the 'Xtractori' program-derived OSAVI and Delta temperature (air temperature, canopy temperature) was closely correlated for different wheat cultivars at 50% flowering stage across different sites in Australia (NEAUS, South Australia (SA), and Western Australia (WA)) (data source: Das et al.[91]).

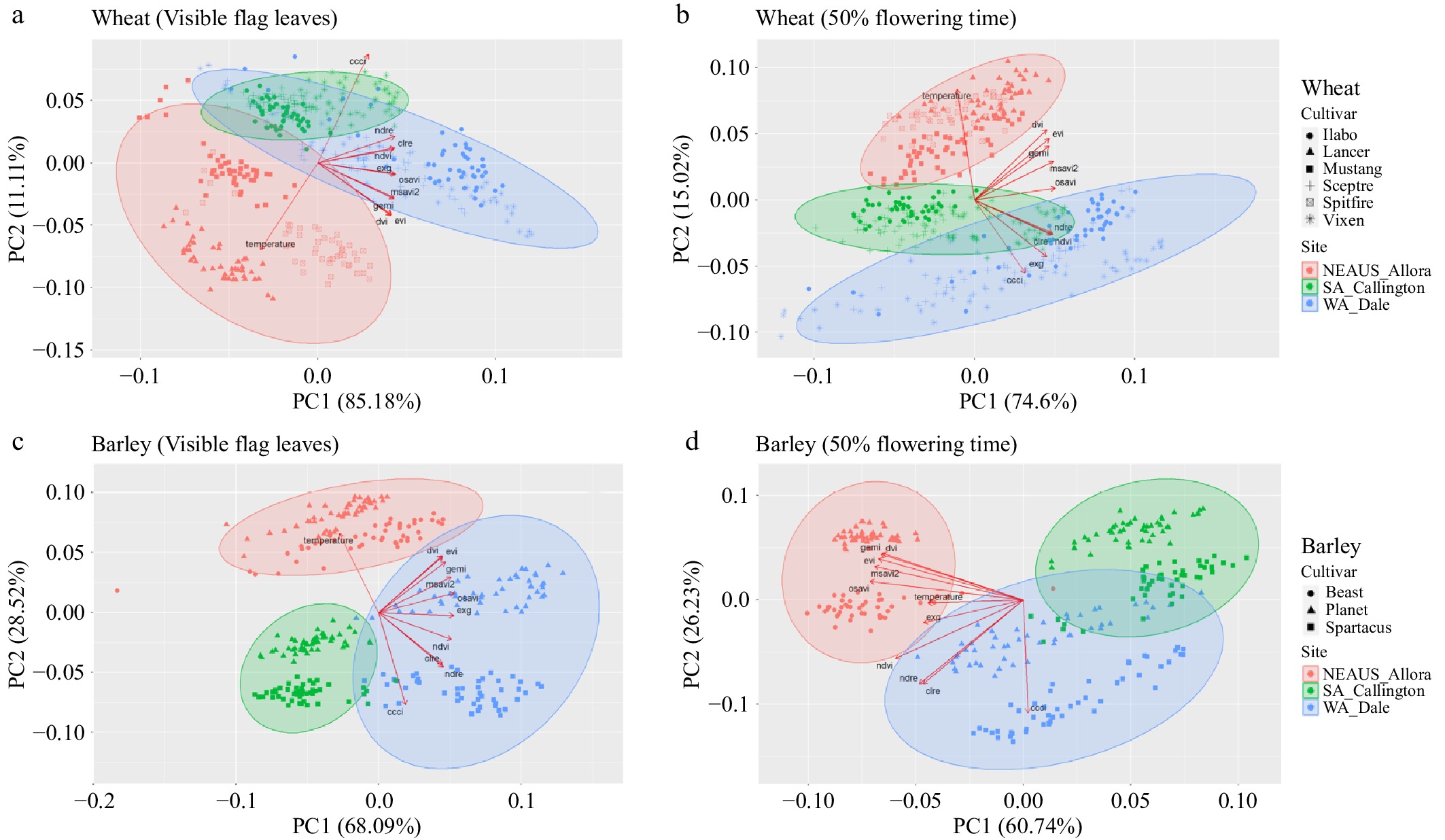

Figure 6.

Principal component analysis and clustering methods were applied to the UAV-multispectral images and the 'Xtractori'-derived multiple crop physiological and morphological traits, such as canopy temperature, canopy chlorophyll content index (ccci), chlorophyll rededge index (clre), normalized difference rededge index (ndre), normalized difference vegetation index (ndvi), excess green index (exg), optimized soil adjusted vegetation index (osavi), modified soil adjusted vegetation index 2 (msavi2), global environmental monitoring index (gemi), enhanced vegetation index (evi), and difference vegetation index (dvi), on different cultivars of wheat and barley crops across different sites in Australia (NEAUS, WA, and SA) to determine the associations and directions among the traits at different phenological stages. PCA biplots using two components (PC1 and PC2) indicating the interactions between crop traits and clustered datasets among cultivars across different sites and changes with the crop phenological stage: (a) wheat cultivars at the 'flag leaf' phenological stage; (b) wheat cultivars at the '50% flowering' phenological stage; (c) barley cultivars at the 'flag leaf' phenological stage; and (d) barley cultivars at the '50% flowering' phenological stage (data source: Das et al.[91]).

Moreover, drone-based planting systems, which can reduce the sowing cost by up to 85% compared to traditional practices, are currently being used[7]. From spraying pesticides or any other nutrient solution to overall crop monitoring seems very easy with these kinds of sensor drones. By scanning the crops, UGVs and UAVs can detect crop disease in the field even if it has appeared in a very small patch of the total field. With the help of highly advanced software, these devices can be used for data collection and for performing several laborious field operations quite easily and even within a very short period. The thematic analysis also revealed that 'economic and social effects', 'energy efficiency', 'RS', and 'AI', with related concepts such as 'anaerobic digestion', 'wireless sensor network', 'agricultural robots', and 'smart agriculture', are the specialized areas of digital agriculture combined with renewable energy sources, which can lead to more affordable, sustainable, and energy-efficient energy-smart farms[92].

-

To secure future demand for food, many nations are using these digital technologies in their farming practices in innovative ways. Some of them are discussed below.

Vertical farming and urban agriculture

-

Vertical farming and/or urban agriculture is one of the solutions for a sustainable food supply in modern urbanization. Urban vertical farming has received increasing attention since the global demand for food has risen in recent years. Vertical farming is the practice of cultivating crops in layers that are built and assembled vertically to produce food in challenging circumstances without access to adequate land[7]. Ultimately, it helps to reduce the crop growth cycle, boost plant density, and increase the harvest output by maintaining a controlled and optimal crop-growing environment[93]. Farms can appear in places where traditional agriculture is not possible, such as underground, abandoned areas, or even on rooftops, without the need for proper agricultural land[94]. Each farm uses unique technologies for particular microenvironments, and crops can be grown on a local level, allowing them to remain fresh for a longer period. With the help of digital technologies, this approach has taken conventional agricultural systems to a new level in many countries, such as AeroFarms in New Jersey (USA), Smart Farm in China, Nuvege Plant Factory in Japan, Sky Green Farms in Singapore, and NextOn in South Korea[95,96].

Hydroponics and aquaponics

-

According to a previous study[97], the two most cutting-edge agricultural practices are hydroponics and aquaponics. Hydroponics is the off-soil cultivation of plants, while aquaponics blends hydroponics with aquaculture (rearing of fish). In conventional agriculture, growing healthy crops demand high amounts of water and labour-intensive weeding. However, in hydroponics, the soil is substituted with gravel, rose-fibre mulch, clay stone, and water-infused nutrients[98,99]. In the case of hydroponics, a microcontroller module coupled with a wireless sensor network works as a well-controlled system that regulates temperature, humidity, and water levels according to crop needs. For example, Sundrop is an Australian agri-industry that effectively grows vegetables in any region through a sea water-based hydroponics technology that combines solar power and desalinization techniques for the sake of agriculture[7]. Currently, this hydroponic system can be merged with greenhouse technology, smart artificial light, and IoT systems for increasing production and profit and for continuously monitoring plant health. Researchers[100] designed an IoT-based Intelligent Plant Care Hydroponic Box with programmable software that allows one to rapidly and easily add, delete, and switch sensors and actuators based on crop requirements. On the other hand, the aquaponic approach combines hydroponics with aquaculture to produce both plants and fish as well as organic food; mainly, the nutrients generated by the fish in the system are distributed to the plants to grow[97]. According to a previous study[101], several techniques, aimed at rendering a specific aquaponic system environmentally friendly and long-lasting, are involved in using water and a certain quantity of fertilizers. A smart growbox based on aquaponics was designed to optimize agricultural produce by utilizing numerous technologies that can work in both automatic and manual modes due to the increasing urbanization caused by insufficient local food and land shortages in Indonesia[102].

Nanotechnology

-

While we consider emerging technologies in agriculture, we must include nanotechnology[103]. The major goals of nanomaterials in agriculture are to decrease the number of chemicals dispersed, reduce nutrient losses from fertilization, and boost production via water and nutrient management[104]. In terms of dimensions, nanomaterials can be zero-dimensional (quantum dots or nanodots), one-dimensional (1D) (carbon nanotubes), two-dimensional (2D) (graphene), or three-dimensional (3D) (gold nanoparticles), etc.[105]. In agriculture, several kinds of nanoparticles are used based on their composition and effectiveness, such as polymeric nanoparticles for the release of agro-chemicals, silver and gold nanoparticles for their antimicrobial properties, nano alumino-silicates as pesticides, titanium oxide nanoparticles for disinfecting water bodies, carbon nanoparticles for crop growth improvement, and liquid nanoparticles as fertilizers[106]. In agreement with the needs of crops, nano fertilizers are nutrient carriers with nano-dimensions that have large surface areas, a strong capacity to hold many nutrient ions, and the capacity to supply nutrients slowly but continuously. On the other hand, any product that can kill crop pests and has nanometer-sized components or offers novel properties relating to these tiny dimension ranges is regarded as a nanopesticide. Either the active ingredient or the carrier molecule of these pesticides is produced through nanotechnology. These pesticides can be in the form of nanoemulsions, nanosuspensions, nanogels, polymer-based nanoparticles, or any such formulations[103]. Nanosensors and nano-biosensors are two new concepts in this field. For harmless, minimally invasive, accurate analysis and surveillance of biological systems, including plant signal transduction pathways and metabolism, nanosensors can be used as transducers, with unique nanometer-scale measurements[107]. Nano biosensors are often built at the nanoscale to gather, comprehend, and evaluate data at the microscopic level. They typically incorporate immobilized bioreceptor probes specific to certain analyte molecules. Nanobiosensors facilitate environmental sustainability, effectively detect harmful substances and other chemicals, monitor DNA and protein, and serve as screening tools for disease and soil quality monitoring[108]. In the case of biotechnology, silicon dioxide (SiO2) nanomaterials have been created to safely transfer DNA snippets and motifs to targeted species during genetic engineering[109]. An entirely new category of 'smart' agricultural inputs is currently being created, including nanoseed varieties with built-in insecticides, that will release them when the needful environmental circumstances are encountered[104].

Biotic stress selection and crop protection

-

Plant disease and pest identification is a difficult task in complex natural environments. Additionally, taking pictures of plant diseases and pests under natural light conditions can cause many problems[110]. Machine vision-based techniques for identifying pests and plant diseases often use traditional image processing algorithms or human feature development in conjunction with classifiers[111]. Utilizing the diverse traits of pests and plant diseases, this kind of technology usually creates an image scheme and chooses an appropriate light source and shooting angle. This method works well for obtaining images with consistent lighting. In general, crop security has been transformed by the development of AI and robotic solutions, which provide more capacity and accuracy to handle agricultural issues[112]. Automated monitoring, early pest and disease detection, targeted treatment application, and effective resource management are all made possible by these technologies, which boost crop yields and promote sustainable farming methods. Semantic recognition accurately analyzes photographs, sensor data, and other inputs and contributes significantly to crop protection by making it possible to identify and categorize pests, diseases, and other hazards to crops[113]. This allows for the provision of timely and targeted interventions that improve crop health and productivity[112]. To accurately classify biotic stress and anticipate production for various crops, many sophisticated ML algorithms have recently been proposed. Support vector regression[114], M5-prime regression trees[115], k-nearest neighbors[116], etc., were the most effective approaches. In addition, DL algorithms are anticipated to offer accurate forecasting of plant diseases and agricultural production[117]. A recent study demonstrated that the adoption of new technology requires passionate farm managers as well as widespread support from the public and consumers, which may be attained by emphasizing how little pesticide is used when using these digital technologies[118]. Additionally, image databases of various plant diseases and pests in authentic natural settings are currently in the unpopulated stage[110].

-

While these technological advancements and data-driven solutions have the potential to improve decisions in securing agricultural productivity, it is essential to understand how to take advantage of developing technology at each stage of the crop production chain to have the desired influence on food production in terms of quantity as well as quality. It is also worth noting that this technological revolution has had an enormously positive effect on society. Caution should be exercised when dealing with the widespread technocentric narratives associated with smart farming since they can both create harm and benefit[119]. Predictive analytics and machine learning techniques are typically used in web-based software applications that assist farm-related activities and operations[57]. Many nations worldwide, such as the DigiScape Platform and Food Agility Hub in Australia, the DigitAg program in France, the Internet of Food and Farming Program and Digital Innovation Hubs or SmartAgriHubs in the European Union, etc., have already released different research initiatives to increase the importance of this digitization[120].

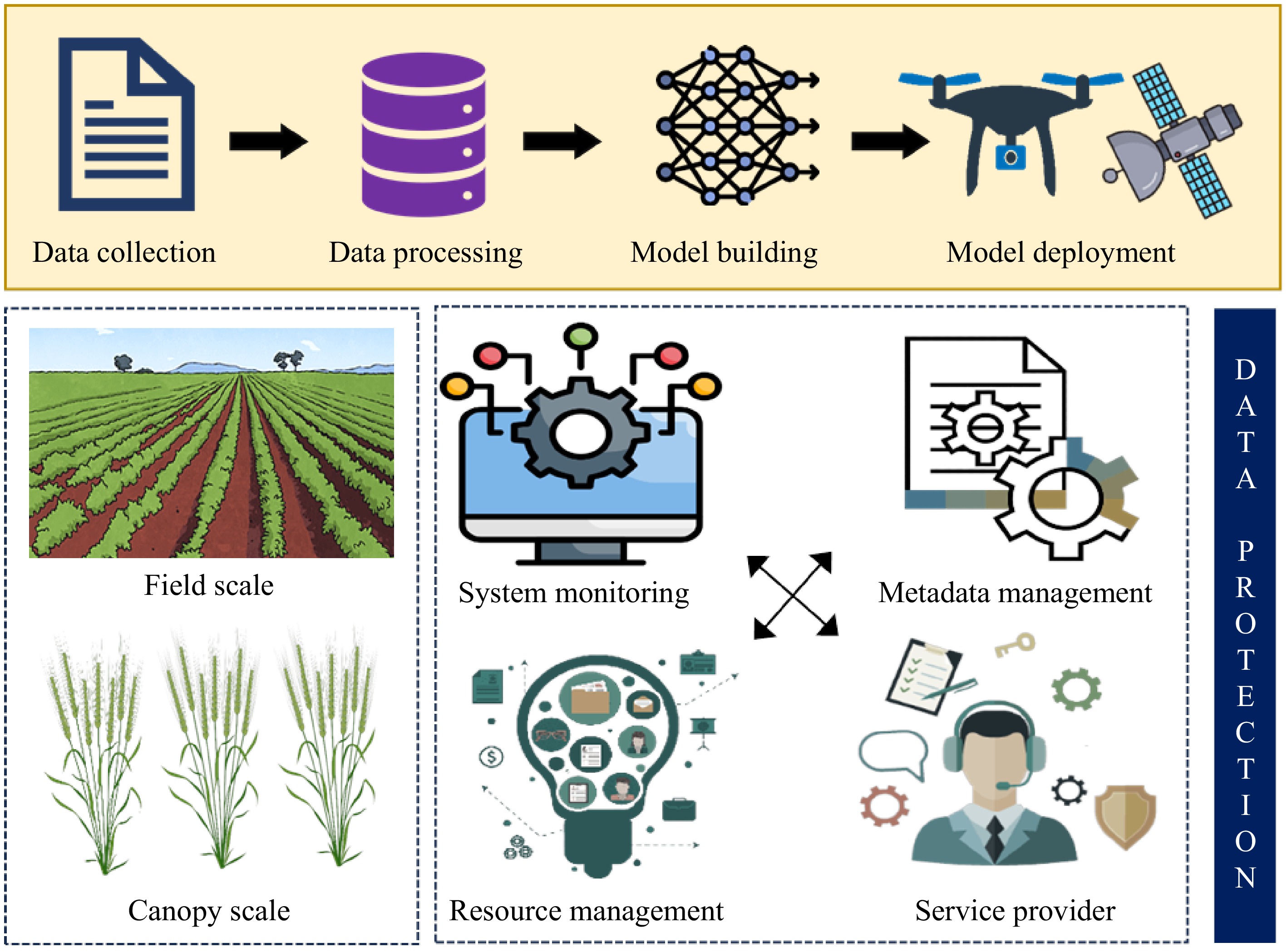

Notably, the applications of these digital tools are not restricted to a single phase of agricultural operation. The chain starts from the initial pre-farm operation and continues through the post-farm stage. Before sowing a crop, field condition data, weather, soil physicochemical data, moisture, etc., can be monitored by several sensing technologies and robotic devices to support farmers in making certain decisions to improve crop production[121]. The processes of data acquisition, data processing, model building and deployment, database generation, connections, and application building in agriculture using these digital technologies are summarized and depicted in Fig. 7. Although agricultural decision-making is heavily reliant on the accuracy of collected soil-crop-weather data/information, as stated above, the primary objective is to acquire an adequate and highly accurate dataset using these smart and/or digital tools on which a decision should rely. Sometimes, to achieve more accurate and reliable outcomes, several computer simulation models using ML and/or DL algorithms can also be applied to collected data to accurately forecast crop water stress[18], nutrient deficiency[13], crop physiological performance[16], crop biomass and yield potential[19], etc. In addition, with the help of gene editing technologies and other genomic developments, it is also possible to improve the characteristics of seeds, such as resistance to certain weed species or tolerance to any specific disease[122].

Figure 7.

Interconnections between agricultural data acquisition, data processing, model building and deployment, database generation, connections, and application building using digital technologies.

In addition, several digital tools based on advanced nanotransporters also help maintain plant growth and protection in this stage[123]. Computational vision, which combines robots and AI, is one of the technologies being employed to automatically carry out operations from planting to harvesting[124]. Some IoT technologies can help farmers monitor and manage their crops from a distance with the help of their cell phones[125]. For the easy application of useful agricultural chemicals such as fungicides, weedicides, and pesticides, several robotic devices can be used in a fully automatic or semiautomatic way for both spray and ground application. The Robot Fleet for Highly Effective Agricultural and Forestry Management (RHEA) was developed and evaluated by a group of 15 organizations and enterprises for use in spraying tree crops and chemical and physical weed control[82]. Many ground and aerial robots with built-in sensors and decision-making algorithms are used, and they are connected to a base station to control the project and allow the robots to work together[126]. Even harvesting operations can easily be performed with the help of machinery connected to different sensors and devices. In postfarm operations such as crop distribution and processing, a set of data-driven technologies can be adopted. AI, CC, mobile and autonomous robots, intelligent software algorithms, etc., have already been proven to be effective in this stage[127].

An iterative approach starting with human operators and moving towards little to no human involvement will be necessary to achieve automation on the farm[57]. Robotics and computer vision are used in the field to remove undesirable plants, apply herbicides, and detect crops and weeds. In the case of any disease and pest detection in crops, the most important aspect is to have prior knowledge of pest control and management. Using these digital technologies, it is now possible to improve crop protection effectively. Researchers worldwide have created several programs that use visual recognition and ML algorithms to identify diseases and pests in different plants. For example, software created by Penn State University researchers is equipped with a deep convolutional neural network (CNN) to detect many diseases in cassava plants, infections by autumn armyworms in African maize, diseases of the potato and wheat, and pests such as spotted lanternflies through transfer learning[128]. Crop harvesting can be considered one of the most laborious tasks in agricultural practices. To address this problem, crop harvesting robots can be deployed that can use their image recognition system and robotic arms for easy harvesting of crops without involving any manual manpower. Even some robots are in the research and development stage and can detect the ripening and proper harvest stage of fruits before harvesting. Israel-based FFRobotics can pick delicate fruits such as apples, pears, plums, and citrus fruits, and AgroBot from Spain can collect more delicate strawberries because both employ DL algorithms to recognize fruits, assess their ripeness, and assign unidirectional robotic arms to pick them[57]. In addition to crops, innovative smart technologies made livestock management easier than early systems. On-farm robotic milking technologies can be mentioned in support of the previous statement[129], which has proven their efficiency in easily milking cattle. To lower the cost of individual robot systems, multi-robot systems have been developed. These systems aid in managing more complex environmental farms and increase the accuracy of operations.

-

The concept of 'digital' and/or 'smart' agriculture has not been entirely established thus far. To do so, there should be a specific framework regarding its development. To promote accountable innovation for digital agriculture, a thorough and systemic strategy must be developed through understanding its dimensions, limitations, and opportunities.

Dimensions

-

A previous study[130] proposed a well-organized analytical framework for smart dairying technology. This can also be adapted and synergized in agricultural digitalization and smart farming practices. To do so, first, we need to identify the major dimensions for directing technological progress in agriculture. This may include anticipation, inclusion, reflexivity, and responsiveness[27].

In the case of technological advances in agriculture, it is important to analyze the possible outcomes through various techniques to anticipate the most suitable outcome. A list of essential technologies for addressing specific problems should be created at this point. The study by Eastwood et al.[130] mentioned two techniques, foresight exercises and horizon scanning and scenario building, for effectively predicting the impacts of new technological innovations. As environmental and production effects can be systematically evaluated, researchers are often able to predict them. However, social consequences are more challenging, and even if they are not generalized, they have to be taken into account[131]. At the time of implementing the techniques, all the possible positive and negative effects should be taken into consideration, whether they are inside the farm or on the life of the farmers, as well as the environment. In every case, a trade-off between these positive and negative consequences must be made. Although it may sometimes be difficult to predict consequences, measures should be taken according to the precautionary principle[132].

Inclusion refers to the incorporation of any tools, techniques, or participation in an idea to make it executable. To reach out beyond agricultural innovation systems and gather the opinions of all stakeholders, a variety of strategies are needed. All stakeholders, including technological firms, farmers, and local communities, should participate in the digitalization of agriculture and the innovation process. The issue of food security cannot be solved by increasing food production through technology, especially in developing nations. While technology is crucial to increasing production and has indeed enhanced food security and wealth, simply producing more food does not ensure better food security for underprivileged people[133]. According to many researchers, digital technologies have been argued to have the potential to concentrate power in the hands of a small number of corporate or state players, both for developed[134,135], and developing nations[136,137]. Therefore, it is important to include strategies for digitalization that are to be disseminated among all the associated stakeholders.

Reflexivity refers to the ability to examine one's motivations and assumptions and how this influences what one does or thinks about particular issues. It is important to take some time to reflect on and further consider how technology may be used to attain these goals[138]. There are several opportunities to evaluate whether mutually beneficial sequences are being followed in agricultural technology ventures. The methods used to help research teams think about primary assumptions and ideas regarding the creation and usage of technology are referred to as reflexive guidance. The ability to take action rapidly on the issues created by new technology is another skill that researchers should acquire. According to a previous study[139], a way for public and private organizations to convey their standards is through certification and standardization processes. Reflexivity has become a public concern, and engaging social scientists in initiatives assists in the reflexive process[140]. This might demand a revision in the law governing technologies secured by the private sector or a modification to the standards for innovations supported by public funds.

In the case of any new research, technology, and/or innovation, overall response or responsiveness is very important. According to the Stilgoe et al.[140], the responsiveness of innovation can be judged by how well it responds to significant societal concerns. Responsible innovation must be able to adjust its direction or extent using methods such as stage gates because societal difficulties, viewpoints, and conventions change with time. Access to research data, open research methodologies, and the ability to modify projects can all be used to evaluate a technology's responsiveness[130]. Finally, individuals who offer innovations to farmers must ensure that corrective systems are put in place to address faults and stop the reoccurrence of any possible disputes (such as safety concerns or animal welfare)[131].

To make the technology and data-driven digital agriculture fully operational, the following aspects should be considered. First, we must increase food production while using less land and less energy. The adoption of technologies that increase farmers' productivity while reducing agriculture's environmental impact is the focus of the vast field of sustainable intensification[141]. Modern biotechnologies and digital innovations are most likely to be the most important in this area, and in the future, anything from 'smart tractors' to 'designer crops' will mean that we can farm more effectively. However, such capital-intensive technologies might only be partially useful in places where a lack of resources and education necessitate the employment of alternative approaches. Second, socioeconomic and political aspects should be included in the digitalization of agriculture. In some countries around the world, improving food security is more successful when considering socioeconomic and political factors, such as women's empowerment, market access, and low-cost instruments[120,142]. Therefore, an agricultural digitalization strategy that is only technology-driven and does not consider the above factors may have variable success rates. Third, we need to carefully address food distribution and waste. Food wastage is an issue in wealthier regions of the world that is caused by grocery stores, eateries, and households. This is a kind of 'wicked problem', in that when nations become wealthy enough to make the investments necessary to build the on-farm food-storage facilities required to reduce food loss, they also become wealthy enough that food waste begins to occur at the opposite end of the food value chain[143]. Fourth, any discussion on how to feed the future must take into account the effects that food choices have on the environment. It is particularly well known that producing cattle consumes a significant amount of resources compared with producing the same amount of nourishment from plant-based sources[144].

Opportunities

-

Over the coming decades, agricultural operations are anticipated to be fully automated and technology-driven, thus creating new economic possibilities as well as novel forms of commerce. Hence, it is necessary to create a more thorough and structured strategy for sustainable innovation to reduce the overuse of agricultural inputs such as fertilizers and pesticides and to combat leaching losses and greenhouse gas emissions at the utmost level[25]. The digital revolution in agriculture is linked to several emerging breakthroughs that are interacting and blending in an evolving 'ecology of innovation'[27]. The installation of a sensor-based system and the establishment of a well-structured communication network in agricultural farms is now possible due to advancements in information and communication technology, which helps in real-time farm monitoring and decision-making. For instance, there are possibly items and services that approach crop production, such as food preparation, using a set of procedures in a strictly regulated framework to grow crops with predictable yields, textures, and flavour characteristics. Through the Open Agriculture Initiative, one such approach was reported to be in the development stage[145].

Most agricultural research still uses top-down, exclusive methods, and important stakeholders, such as farmers and breeders, who are rarely involved in the initial stages[146]. These approaches lower the opportunities of this new generation of agriculture, as farmers must be the major driving stakeholders. Farmers should be involved in open-source agricultural innovations to change economies and meet other crucial development goals, such as ensuring food security and improving nutrition[147]. There are several platforms, including interest group visualization on steering committees, workshops, surveys, online forums, and citizen forums where all stakeholders can be engaged together to discuss and provide their views[130]. Site-specific information can open up new insurance and business opportunities for the whole value chain, from technology and input providers to farmers, manufacturers, and the retail sector in developing and developed nations[148]. The most important fundamental building block in many different digitalizations is network connectivity. The IoT in smart farming needs to be more advanced using 5G technology in the coming years to carry out farming operations and data collection more efficiently, sustainably, and reliably than before once this framework is held in existence[149].

In addition, to increase crop yield and quality, new nanotools, including nano fertilizers, nano-pesticides, nano biosensors, and nano-enabled soil remediation methods, can be used. These methods can alter the classical concepts of crop production and promote the development of smart farming. In the context of growing populations and climatic constraints, today's agriculture strongly emphasizes digitalization and automation using the IoT and the implementation of massive amounts of data to improve economic effectiveness[150]. Field managers can collect and display real-time agricultural data using tablets and cell phones with the help of drones, satellite images, and programs, which facilitate the monitoring and management of whole farms and crop health[151,152]. On farms, close-range fixed proximal sensors have been utilized to monitor and capture the finest details of variables such as soil and crop moisture, temperature, crop growth rates, greenness, vigour, canopy height, biomass, and nutrient concentrations. If the IoT considers linking all of those systems together, it will no longer be necessary to regularly enter data into several programs in the future[153]. Even with the help of these new technologies, it is possible to lower the environmental impact of agrichemicals. Additionally, farmers might apply these technologies to increase the resistance of their crops to adverse weather and climate change. With the use of such technology, farmers may make more accurate agricultural decisions that can minimize farm expenses, boost profitability, reduce water waste, and play a role in maintaining soil quality[154].

Farmers' working hours will expand not only in the case of minimizing expenses and environmental impacts but also due to the possibility of managing various tasks remotely[155]. Moreover, they can utilize vast amounts of data collected from other farmers' fields to boost their farming operations, monitor weather changes, and maintain close monitoring of several other factors that could have an impact on their agricultural farms and harvests year after year. They can easily combat the effects of disease and pest attacks[111] and nutrient deficiency[13] in their crop fields through the detection of symptoms at early stages. Recently, due to the workforce scarcity triggered by the 'COVID-19' pandemic, field robots have been deployed on farms more frequently to move plants in greenhouses, assess the moisture level of the soil, and spray crops with automated pesticides during pest attacks[156]. In addition, recent advances in IoT and sensor technologies can provide in-depth information about climate and weather, which can help farmers choose climate-resilient crops to be sown and guide them to understand the appropriate sowing time based on the conditions of their farms.

Limitations

-

Although 'digitalization' in agriculture has a wide range of acceptability and prospects, there are still many obstacles to overcome to make it fully operational. In some cases, this digital revolution is changing farming life in an undesirable way, such as decreasing attachment between farmers and their land and decreasing work satisfaction, as most of the work is done by machines or technologies. Therefore, small and marginal farmers face difficulties working with modern technologies, which leads to the consolidation of all the data and technology in the hands of a few large farmers[131]. Emerging technologies produce vast volumes of data, but the ownership of this ample amount of data is questionable. Data generated by commercial machinery that might aid farmers in their process of making decisions are often consolidated in the hands of large companies or firms. Sometimes trust issues can occur between internal firms and foreign investors or companies[157]. This leads to an economic and societal imbalance that can hamper the progress of this new evolving concept. Governments must provide a legal framework that guarantees correct data and encourages collaboration amongst all relevant stakeholders. Irrespective of these issues, mismanagement of technologies, unemployment in rural life due to this machine-driven concept, higher costs, limited knowledge and skills in the farming community about the technologies, the tendency to focus only on major crops, the outbreak of minor diseases and pests, the merging of farmers' traditional knowledge with these new technologies, and limited acceptance of these techniques in the farming community can also emerge as potential barriers to smart farming and/or digital agriculture[25].

In addition, technical and operational constraints include a lack of knowledge, instrument handling and maintenance issues, and improper data extraction. This scenario is more profound in underdeveloped and developing countries, where farming communities are unaware of the latest technologies and lack the skills to operate and maintain this equipment. According to a previous study[158], farmers and holders of rural enterprises are unable to acquire equipment and machinery due to the complexity of technology and the incompatibility of its components. Moreover, the complexity of combining data from several sensors is one of the key issues preventing progress[159]. Sometimes it is not feasible for farmers to understand the proper function and application of different software for analyzing agricultural data. For a fully functional digital agricultural system, telecommunications systems should be well developed in rural areas, which is often not feasible[33]. This leads to hampering the progress of these technologies in most cases for many developing countries. Agricultural data typically come from a range of diverse sources including corporate applications that use a variety of formats and thousands of individual farms and animal farms. Therefore, creating such a sophisticated database pipeline is challenging[160]. Standardization of the tools is also necessary to create relevant results and maintain the quality of the data to properly utilize digital technology for smart farming applications. Furthermore, it is difficult to commercially apply these smart agricultural systems in wide areas. This is because every piece of hardware, including Internet of Things devices, sensor networks featuring wireless sensor nodes, machinery, and equipment, is subject to a variety of unfavourable environmental factors. These factors include intense rain, extreme heat or cold, high or low humidity, strong winds, and numerous other possible dangers that could damage or disrupt electronic circuits[161]. Adequate power supply in farms for large-scale production is another challenging issue for the adoption of digital/smart agricultural technologies.

The development of smart and/or digital agriculture is also somewhat constrained by the high cost of acquiring machinery and technological components. Farmers in developing countries cannot invest such large amounts of capital at a time in the development of smart software and technologies[162]. The low wages of qualified laborers to manage and maintain such sophisticated instruments are another critical and challenging economic aspect in the successful implementation of smart agricultural technologies at farms. From a social perspective, the gap between farmers and researchers is one of the most important roadblocks to the digitization of agriculture in this revolutionary era. Building faith in the efficacy of smart technology in agriculture is challenging, in contrast to other fields, because many actions have an impact on systems involving both living and nonliving forms, and the effects might be difficult to undo[163]. Additionally, the differing legal systems in different places and countries have an impact on the adoption of digital technology in the agricultural business, particularly in monitoring and agri-food supply. These legal systems may also be a major obstacle to the effective implementation of digital/smart agriculture[164]. A fresh policy may be required to make technology more widely available and approachable to farmers. To accelerate the practices of smart agricultural technologies, farmer-focused strategies, and novel efforts must be employed[127]. For technology to have a major impact on the industry, a previous study[165] mentioned the necessity of making behavioral changes in farming communities.

-

This review has provided comprehensive insights into the transformative potential of digital and smart technologies in revolutionizing agriculture and enhancing food security. Digital agricultural systems and smart agricultural systems, though interconnected, represent distinct yet sequential advancements in modern farming. Digital agriculture leverages data and digital technologies, including remote sensing, GIS, AI/ML, IoT, and big data analytics to collect, store, and analyze agricultural information. It facilitates evidence-based decision-making by integrating diverse data sources to boost farm productivity, optimize resource use, and promote sustainability. As a foundational step, digital agriculture establishes a robust data infrastructure, enabling farmers to better understand soil conditions, weather patterns, crop health, and resource availability. Building upon this foundation, smart agriculture goes a step further by incorporating automated systems and real-time responses. It employs AI, robotics, and sensor networks to autonomously monitor, predict, and optimize agricultural processes. Unlike digital agriculture, which focuses on data collection and analysis, smart agriculture actively uses algorithms to make immediate adjustments, such as automatically regulating irrigation based on soil moisture levels detected by IoT sensors. This progression from digital to smart agriculture enhances the precision and efficiency of farming practices. The combined implementation of digital and smart agriculture is crucial for future farming, though their importance may vary depending on technological readiness and regional agricultural contexts. In regions with developing digital infrastructure, digital agriculture serves as a critical first step, laying the groundwork for data-driven insights. For more technologically advanced areas, smart agriculture emerges as a key driver for innovation, ensuring precision farming, minimizing resource wastage, and bolstering crop yields. Importantly, this progression underscores that without a solid digital foundation, smart agricultural systems cannot function effectively, as real-time decision-making and automation rely heavily on accurate data inputs.

The adoption of these technologies presents significant opportunities across the agricultural value chain, from precision farming to supply chain management — fostering efficiency, productivity, and sustainability. Furthermore, they play a pivotal role in enhancing food security by optimizing resource use, improving climate resilience, and supporting adaptive farming strategies. Real-time monitoring and data-driven decision-making enable farmers to mitigate risks and boost yields, contributing to a more stable and secure food supply. Despite their promising benefits, the widespread adoption of digital and smart technologies in agriculture faces several challenges. These include issues related to affordability, accessibility, digital literacy, and data privacy. Addressing these barriers is essential to ensure equitable access to technology and maximize its impact on food security. Collaborative efforts among governments, private sector actors, research institutions, and farmers' organizations are necessary to overcome these obstacles. Policymakers play a critical role in fostering an enabling environment through supportive regulations, investment incentives, and infrastructure development. Additionally, integrating traditional knowledge with digital interventions is key to ensuring that technological solutions are contextually relevant and sustainable. Leveraging local expertise and indigenous wisdom allows these technologies to be tailored to diverse agroecological settings, enhancing their effectiveness.

Moving forward, governments and development agencies should prioritize investments in rural infrastructure, including broadband connectivity and electricity access, to support the widespread adoption of digital technologies. Strengthening digital literacy and providing targeted training for smallholder farmers and marginalized communities is equally important. Extension services and farmer cooperatives can facilitate knowledge transfer and skill development, ensuring that farmers can effectively use digital tools. Collaboration between the public and private sectors should be encouraged to accelerate innovation, scale successful interventions, and address market failures. Public-private partnerships can harness the strengths of both sectors, catalyzing investment in research, development, and technology transfer. Moreover, policymaking must be guided by inclusivity, participation, and equity, with consultation from local communities to ensure digital interventions address the specific needs of end-users. Moreover, establishing robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms is critical to continually assess the impact of digital and smart technologies on agriculture and food security. By tracking progress and identifying lessons learned, policymakers and practitioners can refine strategies and allocate resources effectively.

Overall, the integration of digital and smart agriculture holds immense potential to transform farming practices and secure global food systems. Realizing this potential will require concerted efforts, collaboration, and sustained investment. By addressing key challenges and adopting a holistic approach that merges technological innovation with traditional knowledge and community participation, one can build a more resilient, sustainable, and equitable food system for future generations. In summary:

(1) Agricultural decision-making from field to plate has benefited from the use of digital and smart technology applications.

(2) We discussed the evolution of digital and smart technologies in agriculture, in-field applications, and mechanisms.

(3) Digital and smart technologies in crop management encourage activities to relieve the burden on agro-ecosystems and boost economic gains.

(4) Future opportunities, dimensions, limitations, adoption, and behavioral changes in digital and/or agriculture are discussed.

(5) The inclusion of socio-economic and behavioral perspectives in agricultural digitalization should empower economic growth and food security.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conceptualization: Das S, Dutta S, Roy Choudhury M; methodology: Das S, Dutta S, Roy Choudhury M; visualization, writing – original draft: Das S; section writing: Dutta S; Bhattacharya S, Sadhukhan R, Chatterjee R; literature search and review, data curation, software, formal analysis, validation, resources, co-ordination, supervision: Das S; writing – review and editing: Das S; Roy Choudhury M. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to researchers worldwide for their pioneering contributions in the fields of digital agriculture, agricultural technology, and agri-food sustainability, which have greatly enriched this domain of study. Our sincere thanks also go to the anonymous reviewers for their forthcoming evaluation of this paper, whose insights will undoubtedly enhance its quality. Additionally, we deeply appreciate the dedicated efforts of the research team at the Queensland Alliance for Agricultural and Food Innovation (QAAFI), Centre for Crop Science, The University of Queensland, Australia. We are particularly indebted to Dr. Andries Potgieter and his team, whose exceptional work on 'Xtractori'[91] has been instrumental in advancing knowledge in this area. Finally, we acknowledge with gratitude the invaluable support and collaboration of our colleagues, whose contributions have been pivotal in the successful completion of this comprehensive review article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Das S, Dutta S, Bhattacharya S, Sadhukhan R, Chatterjee R, et al. 2025. Agri-tech evolution: harnessing digital pathways for sustainable agri-food systems. Technology in Agronomy 5: e007 doi: 10.48130/tia-0025-0003

Agri-tech evolution: harnessing digital pathways for sustainable agri-food systems

- Received: 24 October 2024

- Revised: 13 March 2025

- Accepted: 25 March 2025

- Published online: 08 May 2025

Abstract: In recent years, the agriculture sector has witnessed a significant shift towards digitalization, driven by advancements in technology and the pressing need to address food security challenges. This review examines the potential of digital technologies to transform agriculture and ensure food security effectively. By synthesizing the literature and case studies, this paper explores various digital solutions and their impacts on different facets of agricultural practices and food production systems. This synthesis begins by outlining the key drivers behind the adoption of digital technologies in agriculture, including the need for increased productivity, resource efficiency, and resilience to climate change. It then delves into the diverse array of digital tools and platforms available, ranging from precision farming technologies and sensor networks to remote sensing applications. Through an analysis of empirical studies, this paper evaluates the efficacy of these technologies in enhancing crop yields, optimizing resource utilization, and improving supply chain management. Furthermore, this review addresses the socioeconomic and environmental implications of digital agricultural transformation. It also discusses issues such as access to technology, the digital divide, data privacy, and the potential for exacerbating inequalities within the agricultural sector. Future opportunities, adoption, and behavioral changes associated with agricultural digitalization are also covered, highlighting the importance of addressing associated challenges and ensuring equitable access to these technologies. By harnessing digital innovations responsibly and integrating them into holistic agricultural strategies, policymakers, researchers, and practitioners can pave the way for a more sustainable and resilient food system in the face of evolving global challenges.