-

Rice (Oryza sativa L.) is an extensively cultivated cereal crop that provides essential food support to more than half of the people on Earth[1]. This major cereal crop retains pivotal importance for worldwide food security since it satisfies most individuals who reside beneath the poverty line[2]. In Bangladesh, rice is farmed on around 11.7 million hectares, or 77% of the cultivable area, through three distinct growing seasons called Aus, Aman, and Boro (named after their separate growing times)[3]. Boro is an irrigation-dependent season because of the lack of rainfall at this time, while Aus and Aman are completely tropical monsoon rain-dependent seasons for rice cultivation[4]. Approximately 522 million metric tons of rice are produced globally each year, whereas over 39.1 million metric tons are produced in Bangladesh for 169 million people[5,6]. A staple crop throughout the world, rice provides up to 76% of Southeast Asians' calorie consumption and more than 21% of human caloric needs[7]. The demand for rice has increased in Bangladesh, although the area planted to rice is not growing, the country's growing population requires quick growth in rice production. The low rice yield in Bangladesh is as a result of a number of causes. Among these, the crops' susceptibility to diseases and pests is crucial. Various types of pathogenic microbes are responsible for rice diseases. Five diseases, such as sheath blight, bacterial blight, blast, tungro, and ufra have been identified as the most serious among them due to their widespread incidence and substantial damage potential[8]. Over 50% of the world's rice output is affected by sheath blight, a serious disease caused by the fungus R. solani[3], which can spread across large areas and lead to yield losses of up to 70%[9]. Sheath blight affects the entire life cycle of rice, from seedling to heading stage, causing wilting of leaves and sheaths as well as a reduction in seed laying rates[9]. The pathogen hampers rice growth and yield by causing lodging, low yield, and poor grain quality, while also infecting the soil with pathogens and disrupting its biochemical compositions. Large areas may be affected by the disease, which can result in a yield loss of up to 70%[3]. The disease primarily affects the lower leaf sheaths at the maximal tillering or early internode elongation stages of plant growth[10]. The infection spreads swiftly through hyphal runners, which rise from the roots to higher plant parts like leaf blades and other plants, especially in the early phases of grain filling and heading growth[11]. Transplanted aus rice suffers from the worst disease intensity, followed by aman and boro rice[12].

Recovering from sheath blight diseases requires more initiatives than just using conventional rice cultivars or synthetic fungicides to target sustainable rice production[13]. The main strategy for managing rice sheath blight is chemical control, although there are only a few fungicides available for this disease[14]. Currently, the primary methods for treating and preventing the disease are chemical fungicides and cultivation techniques[15,16]. In the field, a variety of fungicides were effective in managing sheath blight disease, including benomyl, captafol, carbendazim, carboxy, chloroneb, edifenphos, mancozeb, thiophanate, and zineb[17,18]. However, there is a chance that fungicide-resistant organisms will arise as a result of ongoing usage of these pesticides, making future disease control more difficult[19], and results in long-term damage to human health and the environment[20]. Fungicide resistance has increased as a result of the frequent and excessive use of these products. Serious public health concerns, particularly in developing nations, are the acute and long-term health impacts of dietary exposure to agricultural pesticides. Chemical pesticides have the potential to be mutagenic, cytotoxic, and carcinogenic to human health[21]. On the other hand, most of the promising cultivars are not able to survive the pathogen, and there are no known resistant cultivars against it[11]. Fungicides that are resistant to diseases like blast and powdery mildew are found in Mediterranean countries. To control conditions, various methods such as biocontrol and integrated pest and disease management techniques are taken into consideration[22]. Utilizing biological organisms such as Bacillus sp. and Pseudomonas sp. to reduce crop disease rates is a tried-and-true method when taking environmental sustainability into account[23]. Nowadays, most individuals have adopted biological ways for growing plants because they are aware of the risks associated with fungicides. In India, Phythium aphanidermatum-induced damping off of mustard is well managed by Trichoderma viridae mutants[24]. They interfere with certain microbes' metabolic processes, which eventually kill the organisms that are infected. Furthermore, bio-control agents work well for diseases caused by soil such Rhizoctonia sp., Pythium sp., and Fusarium sp.[25,26].

Bacillus subtilis, a gram-positive bacterium that belongs to the order Bacillales of the family Bacillaceae, is one of the main bio-control agents used today. It shows promise in managing microbial illnesses that affect both plants and soil. Up to 90% of sheath blight disease can be controlled by Bacillus strains that block R. solani growth[27,28]. Similarly, Pseudomonas fluorescens, a gram-negative bacterium genus belonging to the Pseudomonadaceae family, is also employed extensively as a biocontrol agent to prevent foliar infections brought on by soil-borne infectious illnesses. It is one of the most promising rhizosphere bacteria since it both inhibits disease and encourages plant growth[29]. Additionally, it can avoid plant diseases like soft rot, powdery mildew, and sheath blight. The genus Pseudomonas exhibits resistance to microbial attack on plants and soil because of a variety of processes, including the generation of enzymes, siderophores, volatile organic compounds, biofilms, and other efficient actions[30]. In Bangladesh, a significant amount of research has been conducted on the formulation and application of Pseudomonas sp. and B. subtilis. Its application against the rice sheath blight pathogen R. solani, however, is insufficiently understood.

Antagonistic bacteria have become a viable biocontrol weapon against sheath blight because of their capacity to suppress R. solani growth and activity. To assess the efficacy of bacterial bioagents in practical settings, field tests are necessary. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to find possible bacterial bioagents that could inhibit R. solani, such as Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas sp. The study specifically aimed to determine their efficacy in lowering rice sheath blight in field settings and increasing rice yield while also evaluating their capacity to inhibit the radial mycelial proliferation of R. solani.

-

The experiment was carried out in Plant Bacteriology and Biotechnology Laboratory, Department of Plant Pathology, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh and in a farmer's field, Sutiakhali, Mymensingh Sadar, Mymensingh, Bangladesh. Experiments were conducted during the period of October, 2022–September, 2023.

Sources of Rhizoctonia solani and its isolation

-

Infected rice plants were collected from a farmer's field in Sutiakhali, Mymensingh Sadar, Mymensingh, Bangladesh, and taken to the Plant Bacteriology and Biotechnology Laboratory, Department of Plant Pathology, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh, Bangladesh. The leaf sheaths were then removed from the infected plants and cut into small pieces, about 1 cm long, containing the growing lesion. After that, the pieces were surface sterilized with 1% Clorox (1g NaOCl per 100 mL) for 3 min and washed three times with sterile water. They were then blot-dried and placed on a Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) plate, which was incubated at 28 °C for 3 d. After incubation, actively growing mycelium were transferred to a fresh plate to obtain a pure culture, and finally, a slide was prepared and examined under a microscope.

Identification of fungal isolates by sequencing of the ITS region

-

One hundred ml potato dextrose broth was prepared and the sample was cultured for 7 d. After that, the mycelia were harvested and blot dried with sterile Whatman filter paper. Then 400 mg of mycelium was used for DNA extraction using the Wizard DNA extraction kit. The genomic DNA of fungal isolates was extracted using Wizard® genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Extraction of genomic DNA from fungus was quantified by using a UV spectrophotometer absorbance at 260 nm with a model T-80 UV/VIS and stored at −20 °C. Then DNA concentration was adjusted to 100 ng/μL and verified by comparing it with a 100 bp DNA ladder (Invitrogen, USA) on 1.5% agarose gels.

DNA extraction procedure

-

Leaf tissues were initially frozen with liquid nitrogen and ground into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle. A 40 mg sample of the powdered tissue was transferred to a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube, followed by the addition of 600 μL of Nuclei Lysis Solution. The mixture was vortexed briefly and incubated at 65 °C for 15 min. RNase Solution (3 μL) was then added to the lysate, mixed by inversion, and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. After cooling, 200 μL of Protein Precipitation Solution was added, and the sample was vortexed before being centrifuged at 13,000–16,000 × g for 3 min. The supernatant was carefully transferred to a new tube containing 600 μL of isopropanol, and the DNA was precipitated by gentle mixing. The sample was centrifuged again, and the supernatant was discarded. The DNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol and centrifuged once more. After carefully removing the ethanol, the pellet was air-dried for 5 min and rehydrated with 25 μL of DNA Rehydration Solution at 65 °C for 1 h. The DNA solution was stored at 2–8 °C for further use.

Primers and PCR conditions

-

After isolation, the fungal samples were identified using universal primers ITS1 (5'-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3'), and ITS4 (5'-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3') specific to Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) regions of rDNA from the fungal isolate[31]. The PCR reaction was carried out by Hotstart Master mix (Promega, USA) with genomic DNA as a template. PCR conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, 35 cycles at denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 55 °C for 1 min, and extension at 72 °C for 1 min. The final extension was at 72 °C for 6 min. BLAST program was used to determine the species to identify the fungal isolate. PCR products were visualized in 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide using a Gel Documentation System after separating the PCR products in the agarose gel for 50 min at 80 v.

Bacterial isolates

-

Twenty-three bacterial isolates were used in this study that were identified previously in the Plant Bacteriology and Biotechnology Laboratory against the bacterial blight pathogen of rice[32]. In this study, these bacterial isolates were used to evaluate their efficacy in growth inhibition against the sheath blight pathogen R. solani (Supplementary Table S1).

Assessment of in vitro mycelial growth inhibition of R. solani through dual culture assay

-

The experiment was conducted in a Completely Randomized Design (CRD) with three replications. To assess the in vitro growth inhibition of R. solani by the bacterial isolates, Nutrient agar-Potato dextrose agar (NA-PDA) (1:1) medium was used as described in a previous study[33]. It was autoclaved at 121 °C, 15 PSI for 15 min and the medium was left to cool for 30 min before plating. The in vitro culture (double line method) method was used to test 23 bacterial isolates for their ability to suppress the growth of R. solani. A 6 mm mycelial block was taken from 4-day-old R. solani, and placed at the center of the NA-PDA medium. Single bacterial colonies were streaked in a straight line (40 mm in length) on both sides of the mycelial plug, at a distance of 25 mm from the fungal mycelial plug, in NA-PDA media. The control plate had no bacterial lines and only had a mycelial plug at the center of the Petri dish. These plates were incubated for 5 d at 28 °C. On the 5th d, mycelial growth data (mm) were recorded using a ruler. The radial mycelial growth of R. solani was measured after the incubation period, and the % inhibition was calculated using the following formula[10]:

$ \text{%}\; \rm{I}nhibition=(C-T)/T\times100 $ where, C = Growth of R. solani in control, and T = Growth of R. solani in treatment.

Field experiment and design

-

Field experiment's were conducted in the same farmer's field of Sutiakhali, Sadar Mymensingh, Bangladesh from December 2022–May 2023. The experiments were carried out in a farmer's field using a Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) design with four replications and a plot size of 1 m × 1 m each.

Treatments of the experiment

-

The following bacterial bioagents were used for field experiment based on their performance under in vitro growth conditions against R. solani - BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis); BDISO49JoyR (B. subtilis); BDISOB219R (Pseudomonas taiwanensis); BDISOB221R (Pseudomonas sp.). Here, BD: Bangladesh, ISO: Isolate, B: Bacteria, 'Joy' represents the first three letters of the Joypurhat region, and R: Rhizosphere.

In this study, selected treatments were: (1) T0 = Untreated control; (2) T1 = Positive control (where the plants are sprayed with Amistar Top 325 SC @ 1 mL/L of water with the active ingredient azoxystrobin and difenoconazole); (3) T2 = [BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis)], T3= [BDISO49JoyR (B. subtilis)]; (4) T4= [BDISOB219R (P. taiwanensis)]; (5) T5= [BDISOB221R (Pseudomonas sp.)]

Amistar Top 325 a fungicide launched by Syngenta, Bangladesh, and is the most widely used fungicide for field farming to fight sheath blight. The treatments from T0 to T5 were sprayed at the active tillering stage at 60 DAT. Bacterial formulation was hand sprinkled on the plant surface by hand @ 6.4 g per plot. One mL of chemical solution was suspended in 1 L of water and sprayed by knapsack sprayer. Every time hands were washed and sprinkled separately for each isolate.

Field condition and rice variety

-

For this investigation, the BRRI dhan58 rice variety was chosen. Although BRRI already declared BRRI dhan58 to be resistant to sheath blight, in certain developing regions of the nation, this variety is now exhibiting sheath blight susceptibility. BRRI dhan58 was chosen for this study as a result.

The experimental plots were fertilized with urea, triple super phosphate (TSP), muriate of potash (MoP), gypsum, and zinc sulphate at a rate of 225, 52, 60, 30, 5.5 kg/ha, respectively. The entire amounts of triple super phosphate, muriate of potash, gypsum, and zinc sulphate were applied at the time of final land preparation. Urea was applied in three equal installments at 15, 30, and 45 d after transplanting (DAT). After soaking overnight, the seeds were planted on the farmers land, and 30 d old seedlings were collected and transplanted in well-prepared puddled fields at the rate of four seedlings per hill, maintaining 20 cm × 15 cm spacing. The experimental plots were irrigated as and when it was necessary. During the whole growth period, two hand weedings were done, the first weeding was done at 25 d after transplanting followed by a second weeding at 45 DAT.

Preparation and preservation of talc-based formulation for selected bacterial bioagents

-

Five g carboxy methyl cellulose (CMC) and 7.5 g calcium carbonate was added to 500 g talc powder. This mixture was autoclaved for two consecutive days at 121 °C under 15 PSI pressure for 30 min each. Calcium carbonate was used to adjust the pH to 7.0, CMC to enhance adhesion, glycerol to stabilize bacteria during freezing, and talc powder to maintain bacterial viability, ensuring formulation stability.

The pure cultures of bacterial bioagents were cultured on Lauria Bertani (LB) agar medium for 24 h[10], and the bioagent was grown in LB broth for about 6 h by taking a loopful of bacteria from the LB agar plate. After that, the liquid culture was centrifuged and the pellet resuspended in previously prepared 200 mL peptone broth aimed to fortify with the bactopeptone. This culture broth was then grown for another 2 h with shaking. After that 5 mL of sterile 100% glycerol was added to this 200 mL culture. Then the cultures of the bacterial bioagents (200 mL water fortified with 5 g peptone and 5 mL glycerol 1% of the carrier materials) were added to 500 g sterile talc powder in the tray and mixed well. The formulations were then dried over-night. After that the formulations were powdered manually, and the formulated bacterial antagonists were packed in plastic bags. The shelf life or viability of the formulated bacterial bioagents were also checked (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Artificial inoculation of R. solani in rice plants of the experimental plots

-

Maize sand meal (MSM) media was prepared and the bags filled with MSM media were sterilized at 121 °C, 15 PSI for 20 min in an autoclave, twice at 24-h intervals[34]. Briefly, the R. solani culture was taken from the Plant Bacteriology and Biotechnology Laboratory, BAU, which was identified by sequencing of the ITS region in this study. Three 9 mm mycelial discs were taken from 4-d-old actively growing R. solani cultures from PDA plates. These blocks were cut from the periphery of the plates with the help of a cork-borer. Three mycelial discs were inoculated into the MSM media in a laminar air flow cabinet. Then the bag was tied tightly after releasing air from the bag. The inoculated bag was kept at room temperature until white colored mycelial were completely covering the media. Any contamination observed in the bags was immediately discarded.

Inoculation of R. solani was done at active tillering stage, 60 DAT on the same day as bacterial bioagent application to assess the efficacy of the bacterial bioagents in inhibiting the radial mycelial growth of R. solani. Fifteen-day-old MSM media with mycelium were mixed well by shaking and breaking sand clogs. About 1.04 g per plot of the media with sufficient inoculum of the pathogen were uniformly distributed by hand near the waterline in experimental plots. Regular observations on the development of initial symptoms as elliptical to oval greenish-grey spots in sheaths near the waterline were made at 24 h intervals.

Assessment of sheath blight disease in the experimental plots

-

Sheath blight disease was assessed on the following parameters: (1) Lesion length (cm) at 70 and 81 d after transplanting (DAT). (2) Number of infected tillers 70 and 81 d after transplanting (DAT). The % of disease incidence was calculated using the following formula[35]:

$ \rm{S}heath\; blight\; incidence\; (\text{%})=\dfrac{No.\; of\; sheath\; blight\; infected\; plants}{Total\; no.\; of\; plants}\times100 $ Briefly, 1 = 0% blight (no disease observed), 2 = 0.1% blight (a few scattered plants blighted; no more than 1 or 2 spots in a 12-yard radius), 3 = 1% blight (up to 10 spots per plant; or general light infection), 4 = 5% blight (about 50 spots per plant; up to 1 in 10 leaflets infected), 5 = 25% blight (nearly every leaflet infected, but plants retain normal form; plants may smell of blight; field looks green although every plant is affected), 6 = 50% blight (every plant affected and about 50% of leaf area destroyed), 7 = 75% blight (about 75% of leaf area destroyed; field appears neither predominantly brown or green), 8 = 95% blight (only a few leaves on plants, but stems green), and 9 = 100% blight (all leaves dead, stems dead, or dying).

Harvesting and data collection on growth and yield parameters

-

The crops were harvested at the full maturity stage. The maturity of crops was determined when 90% of the grains became golden yellow in color. Then the harvested crops of each plot were bundled separately, properly tagged, and brought to the floor. After harvesting, data were collected on the following parameters: (1) Plant height (cm); (2) Length of panicle (cm); (3) Number of grains per panicle; (4) Number of chuffy grains per panicle; (5) Weight of 1,000 grains; (6) Yield (t/ha).

Data were collected on lesion length (cm) which was measured using a 15 cm ruler at 10 and 21 d after inoculation for field experiments using the following formula:

$ \begin{aligned} & \text{%}\; \rm{R}eduction\; of\; lesion\; length= \\ & \; \rm{\dfrac{Lesion\; length\; in\; control\; plant-Lesion\; length\; in\; treated\; plant}{Lesion\; length\; in\; control\; plant}}\times100\end{aligned} $ Yield data was recorded at the time of harvest and fresh weight was converted at 14% moisture content using the following formula:

$ \rm{D}ry\; weight=\dfrac{\mathrm{F}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{h}\; \mathrm{w}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{g}\mathrm{h}\mathrm{t}\; (100-\mathrm{ }\mathrm{M}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{e}\; \mathrm{c}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{t}\; \mathrm{a}\mathrm{t}\; \mathrm{h}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{v}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{t}\; (30\text{%})}{100-\mathrm{ }\mathrm{D}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{d}\; \mathrm{m}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{e}\; \mathrm{c}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{t}\; \left(14\text{%}\right)} $ Data analysis

-

The data recorded on different parameters were tabulated in Microsoft Excel 2010 and documented under the RCBD design. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed using the 'agricolae' package in R-Studio (R version 3.5.3). To compare means, Duncan's Multiple Range Test (DMRT) was applied to the analyzed data at a significance level of 5%.

-

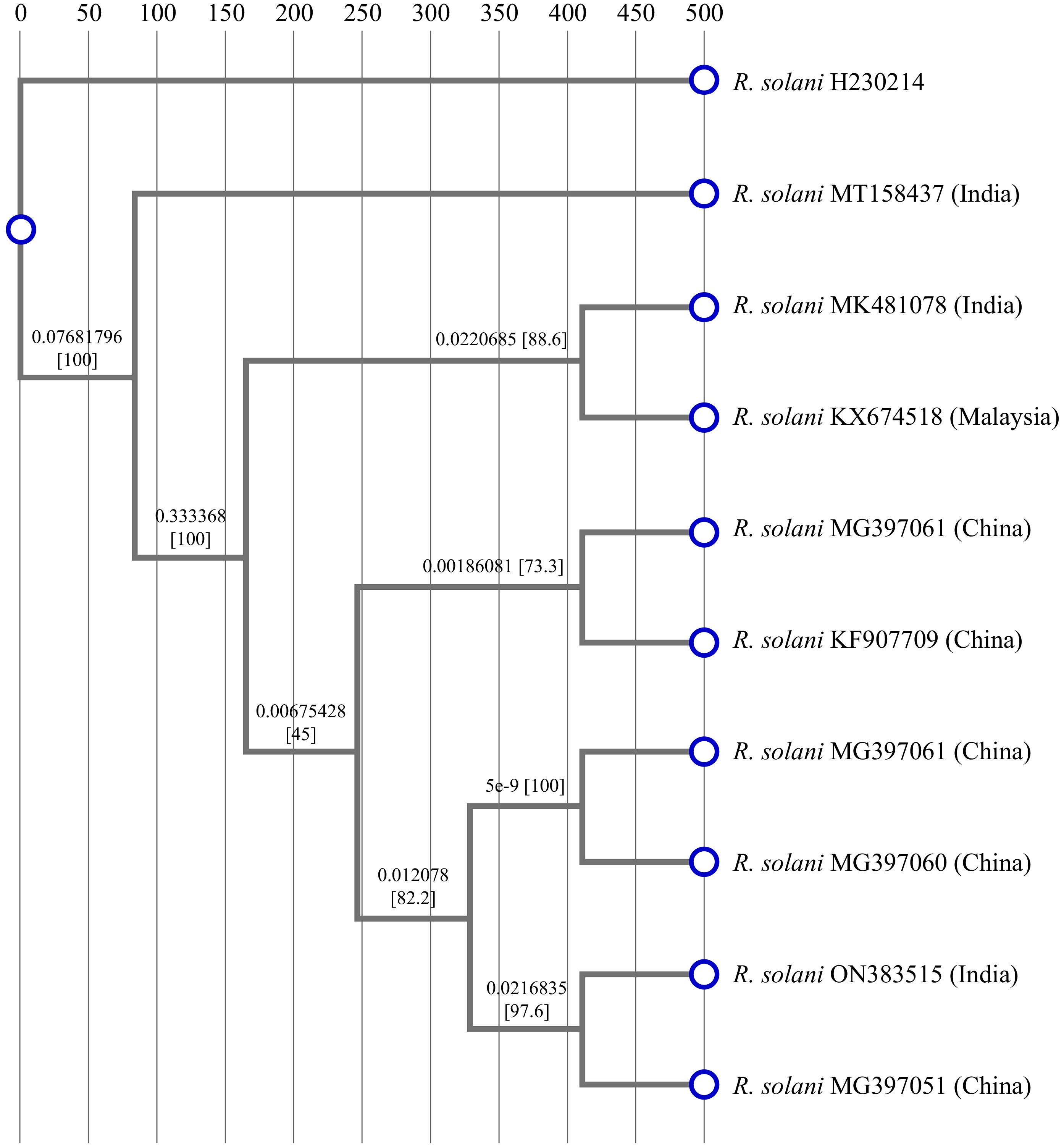

Fungal isolate was identified by sequencing of ITS (internal transcribed spacer) region using ITS-1 and ITS-4 primers, and PCR products were then sequenced. Analysis of sequencing data of amplified ITS region using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) program revealed that the selected R. solani H230214 showed the highest homology with R. solani MT158437 (India) and with R. solani KX674518 (Malaysia), and confirmed that the fungal species was R. solani. Nucleotide sequence alignment by Mega-11 software showed that the nucleotide sequence of the ITS region of R. solani H230214 showed 96.58% homology with R. solani MT158437 with the strain present in the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information). The phylogenetic relationships showed that R. solani was distributed in four clusters. The strain R. solani H230214 belonged to cluster 1 which consists of R. solani (MT158437) in India, and R. solani KX674518 in Malaysia (Fig. 1)[36].

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationship of R. solani H230214 deposited in NCBI. The optimal tree is shown. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (10,000 replicates) are shown next to the branches.

In vitro growth inhibition of R. solani in dual culture assay

-

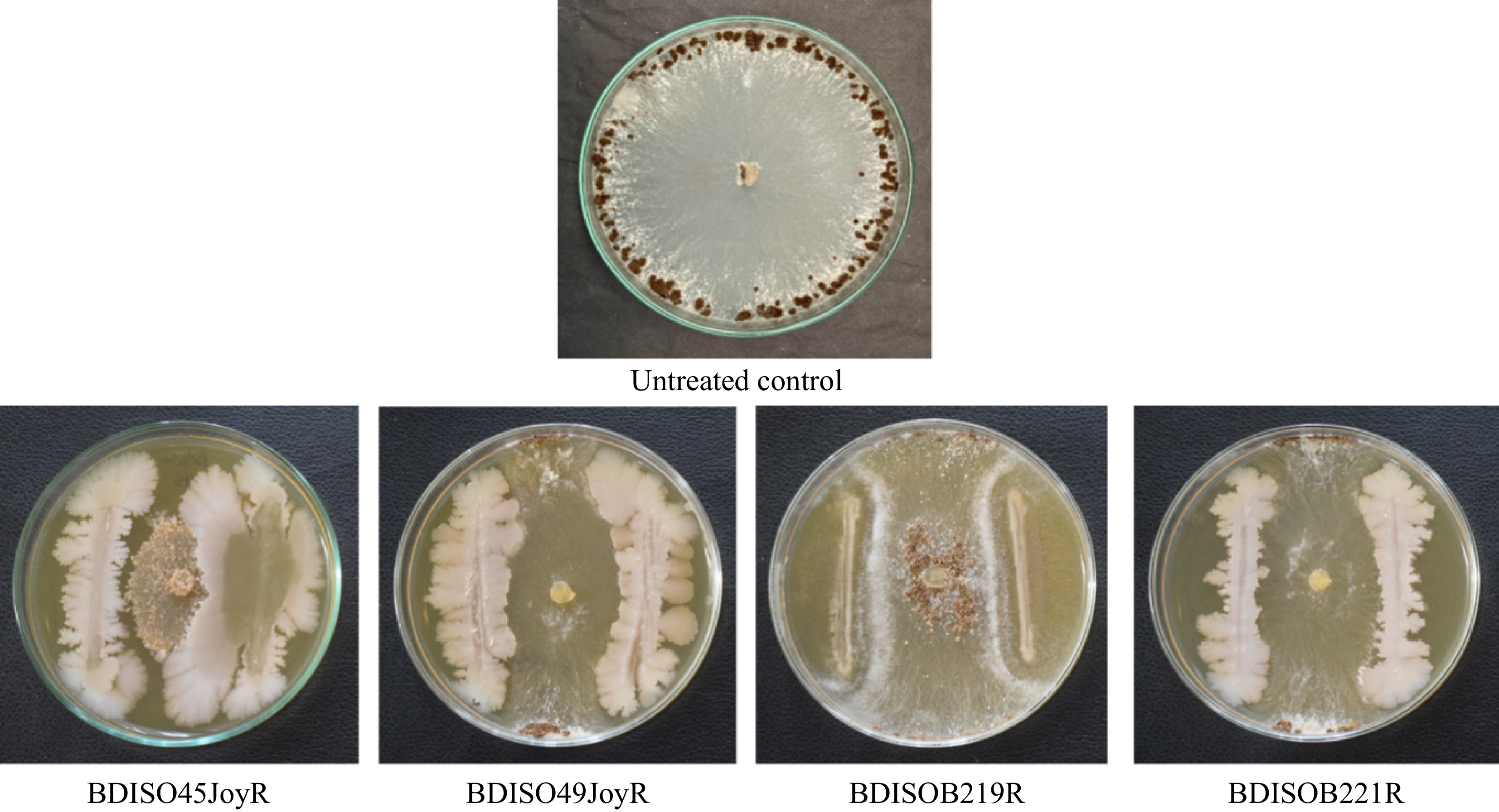

Of the 23 bacterial bioagents of different genera viz BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis strain SA9), BDISO49JoyR (B. subtilis strain K24), BDISOB219R (P. taiwanensis strain GGRJ11), and BDISOB221R (Pseudomonas sp. strain M2.2.1) were found more effective in controlling radial mycelial growth of R. solani (Fig. 2). The isolate BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis strain SA9) showed radial mycelial growth (10.17 cm) which was 76.89% reduction over the control treatment of the dual line method. For the isolate BDISO49JoyR (B. subtilis strain K24), BDISOB219R (P. taiwanensis strain GGRJ11) and BDISOB221R (Pseudomonas sp. strain M2.2.1) the radial mycelial growth was 16.33, 22.67, and 21.42 cm respectively (Table 1).

Figure 2.

In vitro growth inhibition of R. solani by bacterial bioagents. BDISO45JoyR = B. subtilis, BDISO49JoyR = B. subtilis, BDISOB219R = P. taiwanensis, and BDISOB221R = Pseudomonas sp.

Table 1. The effect of different bacterial bioagents on inhibiting the radial mycelial growth of R. solani.

Isolate ID Name of the bacteria Mean radial mycelial growth % Inhibition of radial mycelial growth BDISO02PanR Pseudomonas fluorescens 28.5 ± 0.14b 35.23 ± 0.3f BDISO04PanR Pseudomonas putida 44a 0.00g BDISO38ThaP Pseudomonas fluorescens 27.75 ± 0.75bc 36.93 ± 1.7ef BDISO56BogP Pseudomonas fluorescens 26.58 ± 0.61bc 39.58 ± 1.3ef BDISO64RanP Pseudomonas putida 26.92 ± 0.21bc 38.83 ± 0.46ef BDIS036ThaR Bacillus subtilis 44a 0.00g BDISO39ThaR Bacillus subtilis 44a 0g BDISO45JoyR Bacillus subtilis 10.17 ± 0.95g 76.89 ± 2.1a BDISO49JoyR Bacillus subtilis 16.33 ± 0.55f 62.84 ± 1.2b BDISO61JamR Bacillus subtilis 25 ± 1.08cd 43.18 ± 2.4de BDISOBO4P Pseudomonas putida 44a 0.00g BDISOBO5P Pseudomonas putida 26 ± 0.14bc 40.91 ± 0.31ef BDISOB219R Pseudomonas taiwanensis 22.67 ± 0.55de 48.48 ± 1.23cd BDISOB221R Pseudomonas sp. 21.42 ± 0.34e 51.33 ± 0.77c BDISOB275R Pseudomonas putida 44a 0.00g BDISOB283R Pseudomonas fluorescens 44a 0.00g BDISOB306R Pseudomonas putida 28.42 ± 0.07b 35.42 ± 0.15f BDlSO01R Bacillus amyloliquefaciens 44a 0.00g BDlSO04P Pseudomonas putida 26.17 ± 0.14bc 40.53 ± 0.31ef BDISO45P Bacillus paramycoides 28.42 ± 0.07b 35.42 ± 0.16f BDlSO154P Pseudomonas taiwanensis 44a 0.00g BDISO356P Pseudomonas hibiscicola 27.58 ± 0.61bc 37.31 ± 1.39ef BDISOB92R Pseudomonas fluorescens 44a 0g Level of significance 0.05 CV (%) 2.78 LSD 6.36 Mean values ± standard error. Values with similar letters are statistically similar. BD: Bangladesh, ISO: Isolate, B: Bacteria, First three letters of Location, R: Rhizosphere, and P: Phylloplane. Effect of formulated bacterial bioagents in reducing sheath blight infection of rice under field conditions

-

Although this study offers insightful information about the efficacy of bioagents, it is crucial to acknowledge the limitations resulting from the trial's one-year, single-location design. This scope might not adequately represent the bioagents' wider effects under various circumstances. To further understand the impacts of the bioagents, more research is also required to examine how lesions arise and spread in tillers. Examining the incidence and length of lesions in tillers may provide crucial information that makes the findings more relevant.

Percent lesion length reduction of sheath blight infection

-

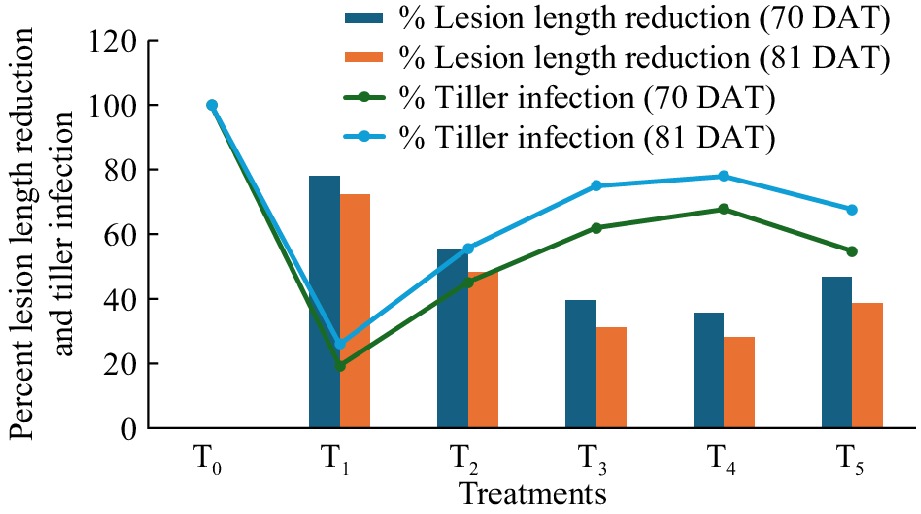

Plants treated with T2 exhibited a 55.25% reduction in lesion length at 70 d after treatment (DAT) in comparison to the control. The reductions for treatments T5, T3, and T4 were 46.96%, 39.78%, and 35.91%, respectively (Table 2). Plants treated with T2 showed a 48.30% reduction in lesion length by 81 DAT, whereas plants treated with T5, T3, and T4 showed reductions of 38.87%, 31.32%, and 28.30%, respectively (Table 2). Under field conditions, T2 achieved the highest lesion reduction, but T1, the positive control, outperformed the other treatments overall (Table 2). At 70 DAT, treatments were most effective, and this is probably the economic threshold when the pathogen was most dramatically impacted by treatment. After this, the treatments' efficacy began to decline as the plants attained their ideal levels of growth and development.

Table 2. Potential of different formulated bacterial bioagents in reducing percent lesion length and tiller infection of rice sheath blight under field conditions.

Treatment Percent lesion length reduction Percent tiller infection 70 DAT 81 DAT 70 DAT 81 DAT T0 0e 0e 100a 100a T1 78.17 ± 2.04a 72.45 ± 0.72a 19.31 ± 1.73e 26.08 ± 2.13e T2 55.25 ± 1.06b 48.30 ± 1.29b 45.20 ± 1.54d 55.73 ± 1.05d T3 39.78 ± 3.42cd 31.32 ± 0.98d 62.05 ± 1.74bc 75.11 ± 1.86b T4 35.91 ± 0.90d 28.30 ± 0.98d 67.83 ± 0.79b 78.05 ± 1.13b T5 46.96 ± 0.91c 38.87 ± 1.00c 54.81 ± 1.64c 67.69 ± 1.55c Level of significance 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 LSD 4.66 3.88 4.77 5.7 CV (%) 8.88 5.24 5.46 7.68 Mean values ± standard error. Values with similar letters are statistically similar. T0 = Control, T1 = Positive control, T2 = BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis), T3 = BDISO49JoyR (B. subtilis), T4 = BDISOB219R (P. taiwanensis) and T5 = BDISOB221R (Pseudomonas sp.). Percent tiller infection and reduction of the infection of sheath blight of rice

-

At 70 d after treatment (DAT), plants treated with T2 had the lowest percentage of tiller infection (45.20%), whereas T5, T3, and T4 had 54.81%, 62.05%, and 67.83% infection, respectively, compared to the control (Table 2). By 81 DAT, plants treated with T2 had the lowest tiller infection rate (55.72%) compared to the control (Table 2). T5, T3, and T4 had tiller infection rates of 67.69%, 75.11%, and 78.05%, respectively, while the positive control (T1) worked better than all other treatments (Table 2).

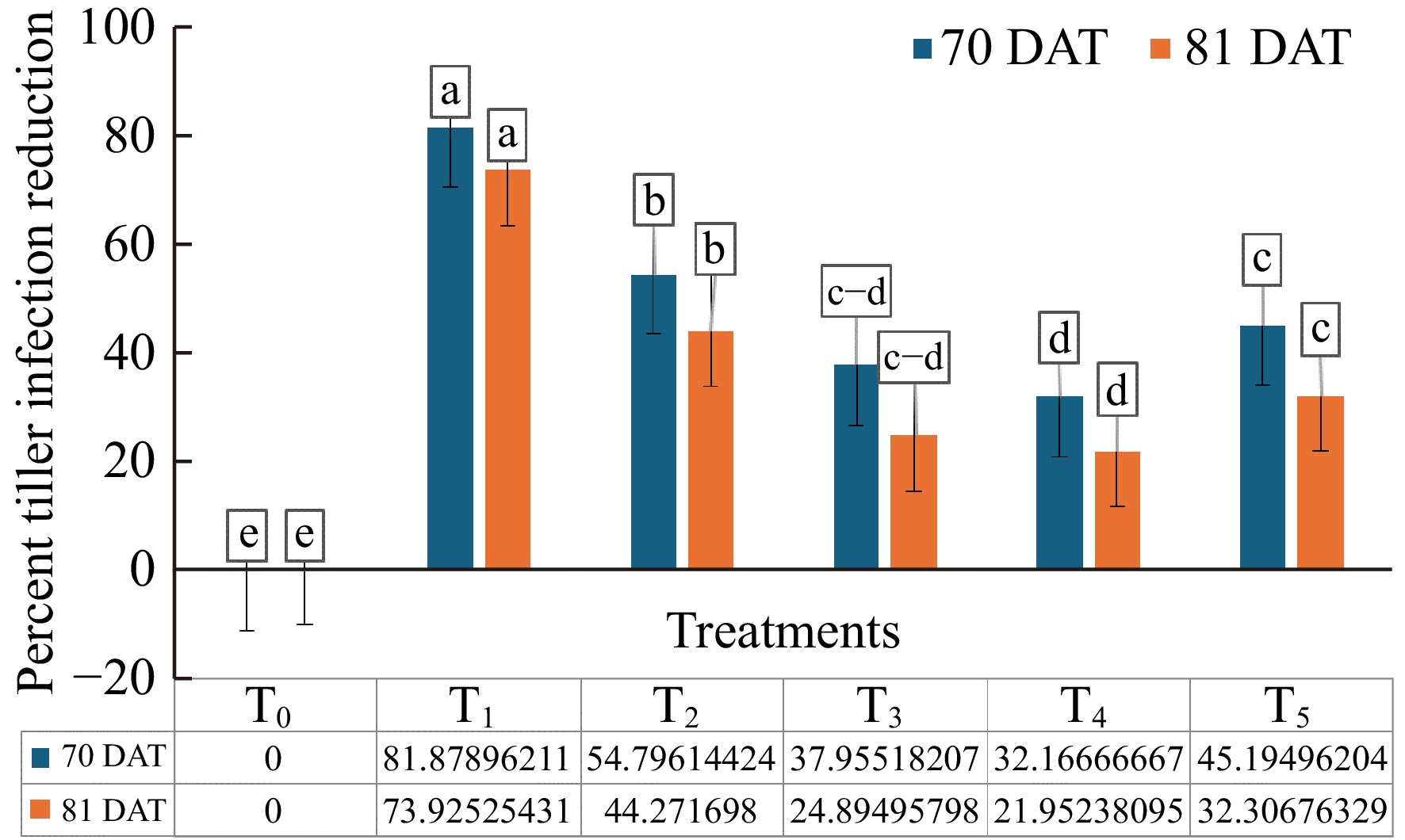

To increase readability and clarity, graphical representations of reduced lesion lengths and tiller infection percentages were incorporated into the tables (Fig. 3). Although these measures transmit comparable information, displaying them from different angles would provide a full picture of the bioagents' performance.

Figure 3.

Effect of formulated bacterial bioagents in percent lesion length reduction and tiller infection of rice sheath blight caused by R. solani under field conditions at 70 and 81 DAT. T0 = Control, T1 = Positive control, T2 = BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis), T3 = BDISO49JoyR (B. subtilis), T4 = BDISOB219R (P. taiwanensis) and T5 = BDISOB221R (Pseudomonas sp.).

At 70 DAT, among the bacterial bioagents used in this study, plants treated with T2 showed a 54.80% reduction in tiller infection (Fig. 4). The treatments with T5, T3, and T4 resulted in 37.97%, 32.17%, and 45.20% reductions in tiller infection over the control, respectively (Fig. 4). By 81 DAT, the plants treated with T2 showed a 44.27% reduction in tiller infection, while T5, T3, and T4 showed reductions of 24.90%, 21.95%, and 32.31%, respectively (Fig. 4). The positive control, T1, performed better than all other treatments (Fig. 4). Compared to 81 DAT, the number of tiller infections was much lower at 70 DAT. This suggests that the bioagent treatments were effective in reducing the intensity of the pathogen early on. The bioagents largely controlled the pathogen, leading to a significant reduction in infection levels by 70 DAT.

Figure 4.

Effect of formulated bacterial bioagents in percent tiller infection reduction of rice sheath blight caused by R. solani under field conditions at 70 and 81 DAT. T0 = Control, T1 = Positive control, T2 = BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis), T3 = BDISO49JoyR (B. subtilis), T4 = BDISOB219R (P. taiwanensis), and T5 = BDISOB221R (Pseudomonas sp.)

Effect of formulated bacterial bioagents on growth and yield parameter of rice under field conditions

-

Among the bacterial bioagents used in this study, plants treated with T5 exhibited the maximum plant height (116.5 cm), while the lowest plant height was recorded in untreated plants T0 (Control). In terms of panicle length, plants treated with T2 showed the maximum length (22.93 cm), with the lowest panicle length observed in untreated plants T0 (Control). The highest number of grains per panicle (234.75) was found in plants treated with T2, while untreated plants T0 (Control) had the lowest number. Regarding chuffy grains per panicle, plants treated with T2 showed the lowest number (11.5), while untreated plants T0 (Control) had the highest. Additionally, plants treated with T2 had a maximum weight of 1,000 grains (22.44 g), with the minimum recorded in untreated plants T0 (Control). However, it is important to note that the weight of 1,000 grains is primarily influenced by the genetic material of the rice type, so there was no significant variation in this characteristic. Overall, the positive control T1 outperformed other treatments (Table 3).

Table 3. Effect of different formulated bacterial bioagents in enhancing growth and yield parameters of rice.

Treatment Plant height

(cm)Panicle length

(cm)No. of grains per panicle No. of chaffy grains per panicle Weight of 1,000 grains (g) Yield (t/ha) % Yield increase T0 106 ± 2.97c 19.3 ± 0.9d 138.5 ± 1.9e 54.3 ± 2.2a 21.7 ± 0.3b 3.34 ± 0.06e 0e T1 113.3 ± 1.7ab 23.2 ± 0.6a 240.3 ± 1.7a 9.8 ± 0.9d 22.7 ± 0.05a 5.87 ± 0.09a 76.29 ± 1.44a T2 115.3 ± 2.3ab 22.9 ± 0.6ab 234.8 ± 2.6ab 11.5 ± 1.3cd 22.4 ± 0.1ab 5.28 ± 0.06b 58.51 ± 0.9b T3 110.5 ± 1.9abc 21.5 ± 0.6bc 221.8 ± 2.6cd 16.3 ± 1.3b 22.3 ± 0.1ab 4.38 ± 0.09d 31.57 ± 1.39cd T4 109 ± 2.5bc 21.2 ± 0.3cd 215.7 ± 2.7de 17.2 ± 0.9b 22.2 ± 0.2ab 4.31 ± 0.11d 29.67 ± 1.65d T5 116.5 ± 1.1a 21.9 ± 0.2abc 228 ± 3.2bc 14.8 ± 1.1bc 22.4 ± 0.2ab 4.53 ± 0.09c 36.03 ± 1.49c Level of significance 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 0.05 LSD 6.3 2.42 7.66 4.28 1.58 0.21 5.08 CV (%) 3.74 4.63 8.69 13.79 2.32 2.39 8.50 Mean values ± standard error. Values with similar letters are statistically similar. T0 = Control, T1 = Positive control, T2 = BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis), T3 = BDISO49JoyR (B. subtilis), T4 = BDISOB219R (P. taiwanensis), and T5 = BDISOB221R (Pseudomonas sp.). Yield (ton per hectare) and yield increase in percentage

-

Among the bacterial bioagents used in this study, the plants treated with T2 showed the maximum yield (5.31 t/ha), followed by T5 (4.67 t/ha), T3 (4.59 t/ha), and T4 (4.67 t/ha). The lowest yield was recorded in untreated plants T0 (Control). Similarly, the plants treated with T2 showed the maximum yield percentage (59.31%) and the lowest yield percentage was recorded in untreated plants T0 (Control). However, the positive control T1 showed better yield and yield increase percentage compared to other treatments (Table 3).

-

Biological control offers a viable alternative to the chemical management strategy for disease with little or no genetic resistance in host plants[35]. However, identifying possible antagonist strains that can successfully suppress the pathogen in a variety of environmental and soil conditions, thrive in the introduced target areas, and enhance crop growth and yield, are the primary requirements for the success of a biocontrol strategy[37]. In our study, the identification of R. solani was confirmed by sequencing the ITS region using ITS-1 and ITS-4 primers[38–39]. Among 23 bacterial bioagents, the results in dual culture assay revealed that the percent radial mycelial growth inhibition of R. solani exhibited by these bacterial bioagents ranged from 35.23% to 76.89% on the 5th day in the double line method (Table 1). Notably, four bacterial bioagents of different species viz. BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis), BDISO49JoyR (B. subtilis), BDISOB219R (P. taiwanensis), and BDISOB221R (Pseudomonas sp.) were found to be the most effective against R. solani, exhibiting 76.89%, 62.84%, 48.48%, and 51.33% inhibition of radial mycelial growth, respectively. In particular, T5 [BDISOB221R (Pseudomonas sp. strain M2.2.1)] has shown 51.33% radial mycelial growth inhibition against R. solani in vitro. It is similar to the findings and results which found that 56% reduction in P. fluorescens inhibits the mycelial growth and works as an antisporulant to fungal spore development which consequently reduces the disease severity[40]. This kind of bacterial behavior is an added advantage to fight with soil-borne fungal plant pathogens under adverse conditions. They revealed that the B. subtilis strain RH5 well colonized the surrounding of the fungal mycelia and inhibition of spore germination, causing cytoplasmic leakage and bifurcation in newly generated hyphae of R. solani[33]. Similarly, under laboratory conditions, specific strains of B. subtilis and P. fluorescens suppressed mycelial growth up to 75% and 51%, respectively[41], while Raj et al.[41] found that the B. subtilis Bs-1 isolate demonstrated the highest growth inhibition (60.20%) of R. solani. Additionally, both P. fluorescens and B. subtilis isolates have been shown in numerous studies to be able to inhibit the pathogen's mycelial growth[42] because of their ability to produce certain enzymes, volatile organic compounds, peptides, and antibiotics[43–44]. These bacterial biochemical compositions play a vital role in the control of fungal growth and inhibit its disease causal mechanisms. Therefore, bacterial treatments result in positive effects on plant growth and disease management.

Under field conditions, all the bacterial bioagents showed lesion length reduction and tiller infection reduction over control in BRRI dhan58 at 70 and 81 DAT (Table 2). At 81 DAT the maximum (55.25%) lesion length reduction and (54.80%) tiller infection reduction was recorded in BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis strain SA9). This suggests that these bioagents could potentially reduce sheath blight incidence in rice under specific conditions. Another study investigated the efficacy of Bacillus spp. for controlling sheath blight disease in rice where they found that the application of B. subtilis significantly reduced the incidence of sheath blight[45]. Previous studies found that these antimicrobial peptides were observed from a wide range of biocontrol active Bacillus species[46–47]. It was assumed that the antimicrobial peptides produced by bacterial species had been responsible for antifungal activity[48]. T5 [BDISOB221R (Pseudomonas sp.)] showed maximum plant height (116.5 cm) followed by BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis) (115.25 cm) compared to positive control (113.25 cm) (Table 3). The bacterial bioagents were used in this study, among them, the plants treated with T2 [BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis)] showed maximum panicle length, (22.93 cm), number of grains per panicle (234.75), weight of 1,000 grains (g) (22.44 g), yield (5.28 t/ha) and the lowest results were recorded in untreated plants T0 (Control) (Table 3). The plants treated with T2 [BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis)] showed the lowest number of chuffy grains per panicle (11.5), and the highest number of chuffy grains per panicle was recorded in untreated plants T0 (Control) in this study (Table 3). T2 [BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis)] showed maximum performance due to both it's inherent compositions and better treatment compositions.

The application of bacterial bioagents as a talc-based formulation reduced disease severity and promoted plant growth under field conditions. Though positive control treatment reduced the disease intensity, bacterial bioagent treatments played a dual role by reducing disease severity and promoting the growth of the plant, resulting in increased biomass and yield. A study found that inoculated rice plants with bacterial bioagents resulted in increasing plant height, number of tillers, and grain yield compared to non-inoculated plants[49]. The researchers suggested that the bacteria may have stimulated plant growth by increasing the availability of nutrients or producing growth-promoting compounds. The treatments of rice plants with bacterial bioagents showed significant enhancement of plant height and biomass as compared to control. According to Karnwal et al.[50], plots treated with B. subtilis UASP17 produced more than the control. Their ability to create IAA, siderophores, atmospheric nitrogen fixation, and solubilize phosphate by both antagonist strains may be the reason, as their employment as biological agents aids in promoting plant growth[51–52]. Similiarly, another study showed that B. subtilis strain RH5 produces various plant growth-promoting substances such as hydrogen cyanide, siderophore, indole acetic acid, and has phosphorus, potassium and zinc solubilizing activity, which help plants to survive under R. solani infections[53]. IAA promotes plant growth, and also helps plants grow by improving root formation and growth[54]. Although phosphate is a crucial ingredient for plants, it is nevertheless inaccessible in certain forms[55]. Researchers cited several explanations for the consortium's higher efficacy, including the variety of mechanisms antagonists in the collaboration offer, the wide spectrum of target pathogens, and the synergistic relationship between compatible consortium members[56]. In addition to breaking down the cell walls of invasive pathogens, Pseudomonas fluorescens and Bacillus subtilis are known to produce defense-related enzymes during the early stages of colonisation, including chitinase, peroxidase, and β-1,3-glucanase. These enzymes may activate induced systemic resistance (ISR) in host plants, increasing their resistance to a variety of phytopathogens[52,57]. According to reports, both antagonists contribute to the formation of biofilm[58] between the pathogen and the lesion, which helps to keep the pathogen and host from coming into contact.

In contrast, the use of fungicides is the most popular strategy for controlling rice sheath blight[59], with foliar spraying[60], and seed treatment[61] being the widely adopted application techniques. Fungicides continue to be the most successful control method for rice sheath blight, lowering percent disease index (PDI) ranged from 11.16% to 34.85%, with a reduction in PDI ranging from 53.1% to 67.9%[62]. They prevent the spread of the disease on rice sheaths by affecting R. solani and its sclerotia in a number of ways, such as by rupturing the fungal cell membrane[63], inhibiting enzymes[64], interfering with vital functions like respiration or energy production[65–66], or disrupting metabolic pathways linked to the biosynthesis of sterol and chitin for the formation of cell walls[67]. Although this study shows that bacterial bioagents can be used to manage rice sheath blight, its conclusions are limited by a single-year, single-location field experiment. This narrow focus might not adequately take into consideration differences in pathogen dynamics, environmental factors, and rice cultivar reactions. Hence, these bioagents require additional multi-location and multi-year tests to ensure their resilience and wider applicability. Since the initial experiment focused on evaluating the effects of individual bioagents against R. solani to manage rice sheath blight, future studies could explore their combined application to assess potential synergistic effects and improved disease control. Given the strong evidence for bacterial bioagents in sheath blight control, further efforts should focus on their formulation and large-scale commercialization. Additionally, characterizing biosynthetic gene clusters responsible for antifungal secondary metabolites could lead to the development of novel biopesticides for managing this seed- and soil-borne pathogen.

-

The results of the dual culture assay revealed that among four bacterial bioagents of different species, BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis) was the most effective against R. solani, exhibiting 76.89% inhibition of radial mycelial growth. The results showed that the application of BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis) significantly reduced the lesion length by 55.25% compared to the untreated control in field experiments. Similarly, the same bacterial bioagent also reduced the maximum tiller infection by 54.80. Furthermore, BDISOB221R (Pseudomonas sp.) showed a maximum plant height of 116.5 cm. From all treatments, BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis) resulted in the maximum yield of 5.28 t/ha (58.51% increase over control) compared to the control. These findings suggest that the use of these bacterial bioagents can serve as a promising eco-friendly approach for the management of rice sheath blight, contributing to sustainable rice production. However, the evaluation of the field potential of these bacterial bioagents in other rice varieties in different seasons will be the next step of the research, to find out the best potential bacterial bioagents in controlling sheath blight of rice. In addition, identification of the bioactive compound(s) from these bacterial bioagents and formulation of biopesticide(s) instead of live bacteria for field application would be the best option for future studies.

This research was carried out with the financial support from National Agricultural Technology Phase-2.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: data collection: Reedoy MAH, Khan I, Sarly SP, Rahaman M, Dipty AR; laboratory work, and data analysis: Reedoy MAH; analysis and interpretation of results: Reedoy MAH, Shahi M, Hasan MH, Auyon ST, Islam MR; draft manuscript preparation: Reedoy MAH, Shimu JF, Hasan MH, Singha UR; project supervison: Islam MR. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 List of bacterial isolates used in this study.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Formulation of some selected potential bacterial bioagents.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Reedoy MAH, Shimu JF, Khan I, Shahi M, Hasan MH, et al. 2025. Harnessing bacterial bioagents to control sheath blight of rice. Technology in Agronomy 5: e010 doi: 10.48130/tia-0025-0005

Harnessing bacterial bioagents to control sheath blight of rice

- Received: 19 October 2024

- Revised: 17 March 2025

- Accepted: 29 March 2025

- Published online: 02 July 2025

Abstract: Sheath blight is caused by the fungal pathogen Rhizoctonia solani which causes yield losses of 20% up to 70%. While fungicide application is indeed effective against R. solani and can be safe when applied correctly, improper applications can have potentially negative effects on the environment and animals and may lead to fungicide resistance in pathogen subpopulations. The present study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of formulated bacterial bioagents in controlling sheath blight pathogen R. solani and sheath blight disease of rice to assess their performance in increasing rice yield. Out of 23 bacterial isolates, four bacterial isolates of different species viz. BDISO45JoyR (Bacillus subtilis), BDISO49JoyR (B. subtilis), BDISOB219R (Pseudomonas taiwanensis), and BDISOB221R (Pseudomonas sp.) were found to be the most effective against R. solani. These four bacterial isolates were formulated using talcum powder as a carrier material in the laboratory. Under field conditions, the formulated bacterial bioagents significantly reduced the lesion length and tiller infection of sheath blight, with BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis) showing a maximum reduction of 55.25% and 54.80%, respectively, over the untreated control. The minimum reduction of lesion length and tiller infection was 28.30% and 32.17% was recorded in BDISOB219R (P. taiwanensis). BDISOB221R (Pseudomonas sp.) showed a maximum plant height of 116.5 cm. All the formulated bacterial bioagents showed better performance over control that increased yield. The maximum yield of 5.28 t/ha with a 58.51% increase over control was observed with BDISO45JoyR (B. subtilis) treatment compared to the untreated control. Therefore, bacterial bioagents should be considered for use in disease prevention and for the healthy growth of plants.

-

Key words:

- Sheath blight /

- Rhizoctonia solani /

- Bacterial bioagents