-

Cropping system diversification is important for sustainable agriculture[1]. As a winter cash crop, garlic (Allium sativum L.) production in Brazil is feasible based on the adoption of artificially vernalized cultivars using clove seeds obtained by meristem culture[2]. In 2023, Brazil's garlic production reached over 13,544 hectares, with an average yield of 13.6 tons per hectare, totaling 185,000 tons[3].

Goiás state is the second-largest national garlic producer, accounting for over 25% of the total area and 30% of the production volume, outyielding the national average by 18%[3]. Central-pivot irrigation systems are standard in the region, making it a value-added crop with a high production cost[4]. Soybeans (Glycine max (L.) Merr.), and other rainfed commodities, succeed garlic in the summer[5], offering economic gains and other benefits.

An emerging niche in horticultural crops involves cultivating varieties suited for producing edamame (vegetable soybean). This specialty crop is experiencing a surge in global demand due to its nutritional value as a plant-based protein, rich in vitamins and fiber[6]. Traditionally consumed in East Asia, edamame is gaining attention in new regions, such as the USA, where the domestic market appears viable[6].

A recognized advantage of this succession is cultivating a resistant or non-host to prevail against diseases, such as plant parasitic nematodes (PPN). PPN threatens high-value crops, including vegetables and field crops[7], with worldwide losses reaching over

${\$} $ This strategy, carried out for a single year, is effective[9], but extending the cultivation of a non-host crop over two or more years significantly reduces populations of the soybean cyst nematode (SCN), Heterodera glycines (Ichinohe), to low or undetectable levels while still achieving good yields[9,10]. Soybean is the sole major agronomic host of SCN, along with other edible crops and ornamental legumes (Fabaceae). Individual species from 23 different genera within this family, and 116 weed species from other 23 plant families, are also susceptible[11]. Given this limited range, which facilitates rotation, in Brazil, non-host crops include summer-grown species like maize, sorghum, rice, cotton, sunflower, and winter species like oats[12]. Garlic provides an effective non-host alternative for winter rotation and succession, which is crucial for managing SCN, while also offering a greater potential for profitability.

Currently, chemical nematicides remain the primary strategy for managing this PPN. Newly developed products like fluensulfone and fluopyram exhibit drawbacks, including longer soil residual times and higher costs than traditional nematicides[13]. Abamectin is a chemical insecticide/miticide employed successfully for nematode control[14]. More recently, biological control agents (BCA) could be a promising shift, positively modifying the rhizosphere microbiome, and improving yields[15].

PPN occurrences are often associated with mineral deficiencies; thus, plant nutrition is a factor that can also aid disease control[16,17]. Nutrient sprays have been utilized in agriculture for over a century in commercial fertilization programs globally[18], with several products advertised as a valuable component of integrated pest and disease management (IPM) programs.

Even though the succession of garlic and soybeans happens in some regions of Brazil, like in the Goiás state, there are no studies about the dynamics of the H. glycines race 5 and the effect of fertilizers, BCA, and nematicides in this context. Thus, this study aimed to harness the role of garlic and control strategies in a crop succession with soybean affecting H. glycines dynamics, a finding reported here for the first time.

-

The trials were conducted in a central-pivot irrigation area at Paineiras Farm, Campo Alegre de Goiás - GO, Brazil (17°19'47" S 47°47'08" W, 950 masl) - during the seasons of 2023 and 2024. The field was naturally infested with SCN (H. glycines race 5) and had previously been cultivated with soybeans. The regional climate is tropical Aw (Köppen-Geiger classification), characterized by two distinct seasons: one rainy (October to April), and the other dry (May to September). At altitudes above 800 m, average temperatures range between 18 and 26 °C, with an annual temperature range of 7 to 9 °C[19]. The soil was classified as Acric Red Latosol[20], with a texture consisting of 71% clay, 15% silt, and 14% sand.

Seven treatments were employed: 1) Messenger; 2) Abamectin; 3) Baryon; 4) Verango; 5) Nemat + Ecotrich + Pick up Moss; 6) Control. Their composition, class, formulation, application method, and dosage are in Table 1.

Table 1. Experimental treatment composition, class, formulation, and application method/dosage.

Treatments

(trade name)Composition Class Formulation Application method and dosage Messenger Bacillus subtilis Biological control agent (BCA) Wet powder (WP) In-furrow spraying + 30 d after (DAP)

500 g·ha−1Abamectin Abamectin Miticide/Insecticide/Nematicide Emulsifiable concentrate (EC) In-furrow spraying + 30 d after planting (DAP) 1 L·ha−1 Bayron Nitrogen + amino acids Organo-mineral fertilizer Emulsifiable concentrate (EC) In-furrow spraying 500 mL·ha−1 Verango Prime Fluopyram Systemic fungicide/nematicide

(pyridyl-ethyl-benzamides)Suspension concentrate (SC) In-furrow spraying at planting 0.5 L·ha−1 Nemat + Ecotrich +

Pick up Moss (N+E+M)P. lilacinum + T. harzianum +

organo-mineral fertilizer

(urea + algae extract +

plant-based meals)BCA- biological control agents Wet powder (WP) In-furrow spraying + 30 d after planting (DAP)

250 g·ha−1 Nemat 150 g·ha−1 Ecotrich

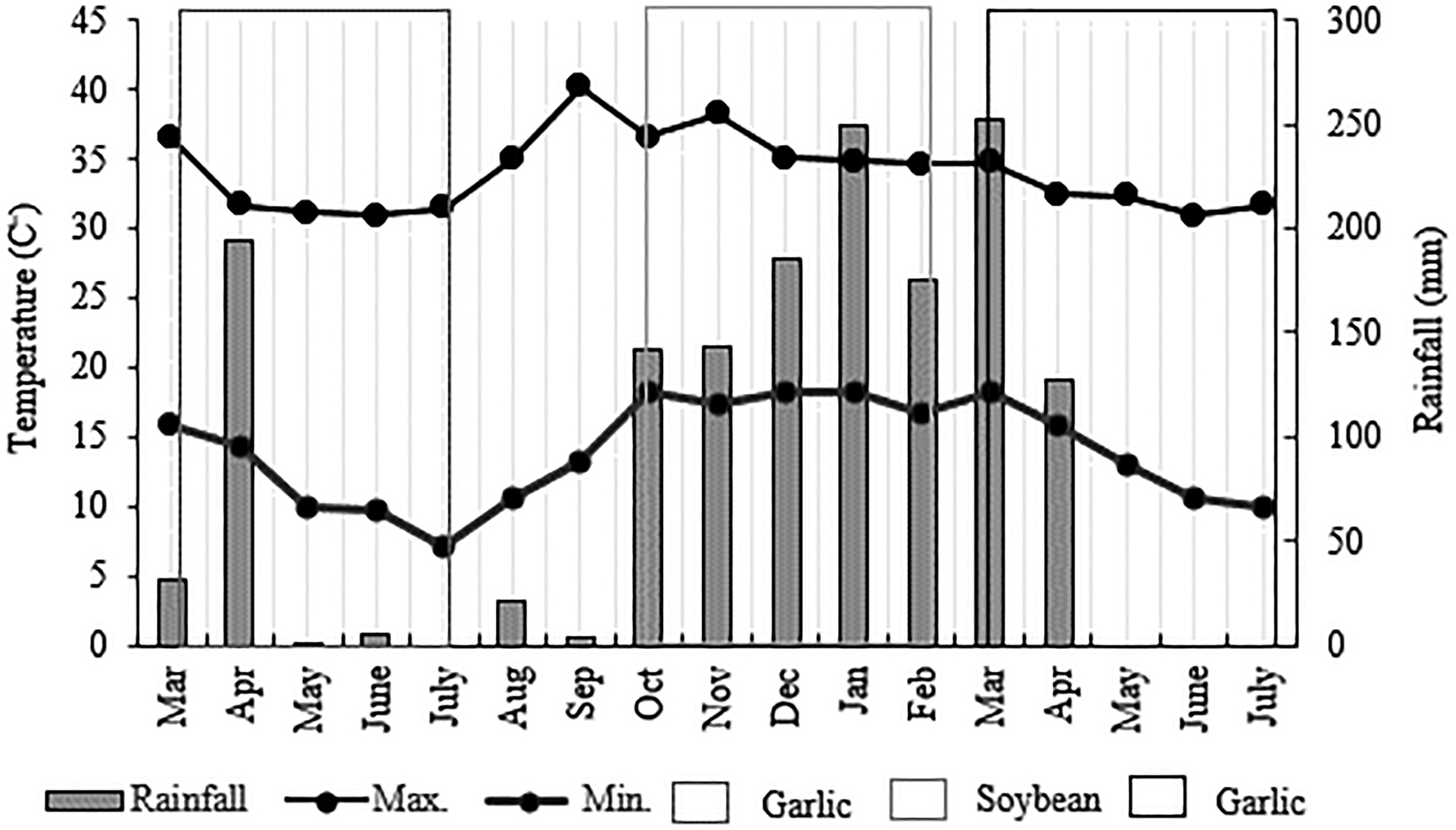

500 mL·ha−1 MossControl − − − − Experiments were held in a randomized complete block design with six replications, in a factorial scheme of treatments (six) x sampling periods (four to five times). The garlic plots featured beds with twin rows of 15 cm, spaced 48 cm from each other, with plants 9 cm apart, resulting in a planting density of 22 bulbils per meter. The three central rows constituted the sampling area, while the two outer rows served as borders. Soybean plots of seven 2-m-long rows, spaced 0.5 m within each other (7m2 x plot). The two outer rows served as borders, while the neighboring rows were used for the SCN population analysis, and the three central rows were designated for yield measurement using 10 plants from the central rows. Weather data for the precipitation, maximum, and minimum temperature values were obtained from an on-site automatic weather station (iCRop, Uberlândia-MG, Brazil), shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Precipitation, maximum and minimum air temperature in the 2023 and 2024 cropping seasons (garlic-soybean-garlic). Campo Alegre de Goiás-GO, Brazil. Source: iCRop weather station.

Concerning weed management, for the garlic trials, the herbicides Goal (Oxyfluorfem) − 1 L·ha−1, Flumyzin (Flumioxazin) − 60 mL·ha−1, and Cotril (Benzonitrile) − 1 L·ha−1 were applied to control broadleaf species. As for grasses, Kenox (Clethodim + Haloxyfop) − 300 mL·ha−1 was applied. The soybean weed control consisted of a single Round-up (Glyphosate) spraying, 20 d after planting. Fungicide applications for the management of leaf diseases were Score Flexi (Propiconazole and Difenoconazole), Fox (Prothioconazole and Trifloxystrobin), Blindado (Picoxystrobin + Tebuconazole + Mancozeb), and SC Nortox (Tebuconazole). All other production and management practices were performed according to the farm system. The identification of SCN race 5 was achieved using a differential host test[21]. Second-stage juveniles and cysts were extracted using the rapid centrifugal-flotation technique, employing a sucrose solution[22]. The extraction of PPN associated with roots was performed using the method of Wilcken et al.[23]. After the extraction, the quantification of the nematodes was performed with Peter's chamber, and the visualization was made under a trinocular stereoscopic microscope (model Eclipse 80i, Nikon, Melville, NY, USA), following Bellé et al.[24] methodology.

Five variables were evaluated: 1) the number of viable cysts of SCN/150 cm3 of soil (NVCS); 2) the number of non-viable cysts of SCN/150 cm3 of soil (NNVCS); 3) the number of juveniles of the second stage (J2) of SCN/150 cm3 of soil (NJ2); 4) number of females in the root system (Nf); 5) reproduction factor (Rf), that is the rate among NJ2 + the viable cysts in the last sampling + NF/NVCS + NJ2, before planting.

Samples were collected to evaluate the SCN population during four stages of the crops: 1− planting: soil; 2 − vegetative growth: soil and plant; 3 − garlic bulbs initial development/soybean flowering: soil and plant; 4 − pre-harvest: soil and plant. The soil sampling dates and samplings for the garlic trial are described as follows: 1 − soil and treatment application: 27/03/2023; 2 − soil and roots (1st): 24/04/2023 (28 d after application); 3 − soil and roots (2nd): 22/05/2023 (56 d after application); 4 − soil and roots (3rd): 23/06/2023 (84 d after application); 5 − soil and roots (4th): 17/07/2023 (112 d after application).

For the first garlic trial, the cultivar Ito was planted on March 26, 2023, and harvested on July 17, 2023. The bulbs classification followed ordinance nº 435, published on May 18, 2022, by the Ministry of Agriculture and Supply Chain–MAPA[25], which established the standards for garlic grades in Brazil. The diameter was measured with a digital caliper, being considered as class 2, when < 32 mm; class 3, when > 32–37 mm; class 4, when > 37–42 mm; class 5, when > 42–47 mm; class 6, when > 47–56 mm; and class 7, when > 56–60 mm. When the bulbs were under 32 mm and presented with slight defects, they were classified as a 'discard' category. As for the second trial, soybean cultivar Brasmax Tormenta CE, resistant to the SCN race 3 and moderately resistant to races 6, 9, 10, 14, and 14+[26], was sown on October 15, 2023, after a fallow period, and harvested on February 15, 2024. Sampling dates are described as follows: 1− (soil and treatments application): 18/10/2023; 2 − soil and roots (1st): 21/11/2023 (34 d after application); 3 − soil and roots (2nd): 14/12/2023 (57 d after application); 4 − soil and roots (3rd): 15/02/2024 (120 d after application). The nematological variables from the previous trial were evaluated along with the following variables: number of pods in 10 plants (NP), pods weight (g) in 10 plants (PW), number of seeds in 10 plants (NS), and seeds weight (g) in 10 plants (SW).

For the last trial, the garlic cultivar Ito was planted on March 18, 2024, and harvested on July 13. Sampling was performed as follows: 1 (soil and treatments application): 19/03/2024; 2 (soil and roots (1st): 19/04/2024 (31 d after application); 3 (soil and roots (2nd): 24/05/2024 (66 d after application); 4 (soil and roots (3rd): 13/06/2024 (86 d after application). The same variables evaluated in the initial trial were assessed. After verifying assumptions, the significance of differences between the means was submitted to an analysis of variance and grouped by the Scott & Knott test using Genes statistical software[27].

-

For the first garlic trial, most of the treatments presented a noticeable decline in the SCN Number of J2 (NJ2) at 28 d after planting and application (DAA), rising from 63 DAA to 112 DAA, except for Fluopyram (Verango) (Table 2).

Table 2. Heterodera glycines race 5: number of J2 (NJ2), number of viable cysts, number of non-viable cysts, and reproduction factor (Rf) for the garlic − 2023 season.

Treatment Days after planting and application Rf 0 28 63 88 112 Mean Number of J2 (NJ2) Messenger 533.33 Aa 133.33 Ba 150.00 Ab 250.00 Ab 333.33 Aa 280.00 b 1.16 a Abamectin 500.00 Aa 70.00 Ba 150.00 Bb 216.67 Bb 416.67 Aa 270.67 b 0.81 a Bayron 516.67 Aa 125.00 Ba 83.33 Bb 250.00 Bb 433.33 Aa 281.67 b 0.64 a Verango 600.00 Aa 400.00 Aa 466.67 Aa 583.33 Aa 233.33 Aa 456.67 a 0.39 a N+ E + M 550.00 Aa 133.33 Ba 116.67 Bb 450.00 Aa 466.67 Aa 343.33 b 0.93 a Control 366.67 Aa 75.00 Ba 116.83 Bb 266.67 Ab 516.67 Aa 268.37 b 1.54 a Mean 511.11 A 156.11 C 180.58 C 336.11 B 400.00 B 316.79 0.91 Viable cysts Mean 20.48 A 9.17 B 4.89 B 6.95 B 6.26 B 9.55 − Non-viable cysts Mean 13.07 A 15.40 A 21.25 A 23.62 A 20.48 A 18.76 − Means followed by the same capital letter in the rows and lower case letters in the column did not differ by the Scott-Knott grouping test (p < 0.05). There was no significance or interaction with the treatments for the number of viable and non-viable cysts. Viable cysts also diminished in the first sampling period (Table 1). In addition to Fluopyram (Verango), which provided higher nematode populations, mainly at 88 and 112 d, the P. lilacinum + T. harzianum + organo-mineral fertilizer (N + E + M) combination also provided higher values at 88 d. As for the overall mean of the bulb diameter (mm), no differences were observed, except for Fluopyram (Verango) and P. lilacinum + T. harzianum + organo-mineral fertilizer (N + E + M) as regards the 53–57 class (Table 3).

Table 3. Garlic yield (kg/ha) based on bulb diameter − 2023 season.

Treatment ≤ 32 mm 32–39 mm 39–44 mm 44–50 mm 50–53 mm 53–57 mm Mean Messenger 30.30 aD 333.33 aD 2,575.76 aB 6,606.06 aA 3,424.24 aB 909.09 bC 2,313.13 a Abamectin 0.00 aD 848.49 aC 2,636.37 aB 7,181.82 aA 3,333.33 aB 1,515.15 bC 2,585.86 a Bayron 0.00 aD 878.79 aC 2,424.24 aB 6,696.97 aA 3,212.12 aB 1,545.46 bC 2,459.60 a Verango 0.00 aC 303.03 aC 3,393.94 aB 7,151.51 aA 3,727.27 aB 4,242.42 aB 3,136.36 a N + E + M 0.00 aC 333.34 aC 2,945.45 aB 9,909.09 aA 4,212.12 aB 4,575.76 aB 3,662.63 a Control 0.00 aD 757.58 aC 1,969.70 aB 6,606.06 aA 2,757.58 aB 969.70 bC 2,176.77 a Mean 5.05 E 575.76 D 2,657.58 B 7,358.59 A 3,444.44 B 2,292.93 C 2,722.39 Means followed by the same capital letter in the rows and lower case letters in the column did not differ by the Scott-Knott grouping test (p < 0.05). The soybean trial exhibited a similar trend to the garlic, with a considerable number of J2 (NJ2) that decreased after the planting and treatment application (DAA). As it also occurred in the control treatment, it points out the same effect of soil tillage/disturbance and the application of the treatments, which may have influenced the SCN population, until the plant's full development. Fluopyram (Verango), mainly at 57 DAA, and the control, at 120 DAA, provided the largest populations of nematodes during the experiment. Later, at 120 DAA, B. subtilis (Messenger) and nitrogen + amino acids (Bayron) also increased the population. For all the treatments, the Rf values were greater, indicating that the number of J2 and viable cysts increased during the crop cycle. Abamectin and nitrogen + amino acids (Bayron) presented the greatest Rf value, similar to the Control. The number of viable and non-viable cysts also diminished from the first sampling taken after planting and treatment application (Table 4).

Table 4. Heterodera glycines race 5 populations for the soybean − 2023/2024 season.

Treatment Days after planting and application Rf 0 34 57 120 Mean Number of J2 (NJ2) Messenger 300.00 aA 0.00 aB 200.00 bA 400.00 aA 225.00 b 3.25 b Abamectin 166.67 aA 66.67 aA 333.33 bA 233.33 bA 200.00 b 6.19 a Bayron 183.33 aA 16.67 aB 183.33 bA 400.00 aA 195.83 b 11.63 a Verango 233.33 aB 150.00 aB 1,333.33 aA 316.67 bB 508.33 a 2.95 b N + E + M 200.00 aA 16.67 aB 216.67 bA 266.67 bA 175.00 b 1.65 b Control 300.00 aB 33.33 aC 366.67 bB 700.00 aA 350.00 a 7.05 a Mean 230.55 A 47.22 B 438.88 A 304.86 A 275.69 5.45 Viable cysts − Mean 37.25 A 12.91 B 10.38 B 13.10 B 18.41 − Non-viable cysts − Mean 59.18 A 20.66 B 23.78 B 23.77 B 31.85 − Means followed by the same capital letter in the rows and lower case letters in the column did not differ by the Scott-Knott grouping test (p < 0.05). Differences were observed for the soybean plants at 120 DAA, where the B. subtilis (Messenger), Fluopyram (Verango), and P. lilacinum + T. harzianum + organo-mineral fertilizer (N + E + M) had the smallest NJ2 for the average of all sampling dates. The organo-mineral fertilizer + amino acids (Bayron) and the control showed a greater NJ2 (Table 4). At 57 DAA, the number of females (Nf) was greater (mean of 45.42), and Fluopyram (Verango) and P. lilacinum + T. harzianum + organo-mineral fertilizer (N + E + M) distinguished from all the other treatments at this period, with the smallest Nf values. Fluopyram (Verango) displayed a derisory mean Nf value compared to all other treatments (Table 5).

Table 5. Interaction between treatments and sampling periods for the number of J2/150 cm3 of soil of Heterodera glycines race 5 in the roots of soybean − 2023/2024 season.

Treatments Days after planting and application 34 57 120 Mean Number of J2 (NJ2) Messenger 283.33 Aa 583.33 Aa 333.33 Ac 400.00 b Abamectin 83.33 Aa 666.67 Aa 1,000.00 Ab 583.33 b Bayron 200.00 Ba 333.33 Ba 1,666.67 Aa 733.33 a Verango 83.33 Aa 250.00 Aa 0.00 Ac 111.11 c N + E + M 216.67 Aa 333.33 Aa 0.00 Bc 183.33 c Control 450.00 Aa 583.33 Aa 1,333.33 Aa 788.89 a Mean 219.44 A 458.33 A 722.22 A Number of females (Nf) Messenger 18.33 Ba 64.00 Aa 36.17 Ba 39.50 a Abamectin 11.54 Ba 62.83 Aa 39.67 Aa 38.01 a Bayron 21.50 Ba 57.83 Aa 25.33 Ba 34.89 a Verango 1.00 Aa 5.83 Ab 5.33 Aa 4.06 b N + E + M 34.83 Aa 30.84 Ab 21.74 Aa 29.14 a Control 37.17 Aa 51.17 Aa 26.17 Aa 38.17 a Mean 20.73 B 45.42 A 25.73 B Means followed by the same capital letter in the row and lower case letters in the column did not differ by the Scott-Knott grouping test (p < 0.05). Regarding the soybean production components in the 2023/2024 soybean trial, Fluopyram (Verango) surpassed all the evaluated treatments for the number of pods (NP) and number of grains (NG), comparable to Nitrogen + amino acids (Bayron) for the weight of grains (WG). No differences amongst treatments were observed for the pod's weight (PW) (Table 6).

Table 6. Soybean production components in the presence of Heterodera glycines race 5 − 2023/2024 season.

Treatments NP

(10 plants)PW (g)

(10 plants)NG

(10 plants)WG

(10 plants)Messenger 635.67 b 361.50 a 1,484.33 b 248.83 b Abamectin 578.50 b 333.17 a 1,277.33 b 255.33 b Bayron 694.00 b 412.33 a 1,520.17 b 304.50 a Verango 831.00 a 482.67 a 1,973.50 a 352.83 a N + E + M 637.33 b 354.00 a 1,640.50 b 269.50 b Control 663.50 b 349.50 a 1,580.00 b 279.00 b Mean 668.10 375.88 1565.74 275.38 Means followed by the same letter in the row did not differ by the Scott-Knott grouping test (p < 0.05). NP, number of pods; PW, pods weight; NG, number of grains; WG, weight of grains. In the second garlic trial, J2 (NJ2) decreased to 66 DAA. The same possible factors might have influenced it, as pointed out in the first trial (tillage to establish beds and form of application of the treatments), as it started to increase again at 86 DAA, showing a lower value than the initial population (Table 7). The interaction between the treatments and the sampling periods was not significant. For the overall mean, Abamectin, nitrogen + amino acids (Bayron), and P. lilacinum + T. harzianum + organo-mineral fertilizer (N+E+M) differed from the Control and the rest of the treatments. The number of viable cysts decreased at 31 DAA, with a slight increase at 66 DAA, returning to an equivalent amount at 86 DAA (Table 6). This did not occur in the previous garlic and soybean trials. The Rf and all treatment values were below unity, indicating that the SCN population multiplied less in this last crop, and the initial population was reduced compared to the first trial (Table 7).

Table 7. Number of J2 (NJ2), number of viable and non-viable cysts of Heterodera glycines race 5, and reproduction factor (Rf) for the garlic crop − 2024 season.

Treatment Days after planting and application Rf 0 31 66 86 Mean Number of J2 (NJ2) Messenger 8.667 2.000 2.000 2.000 3.667 b 0.43 a Abamectin 6.000 1.333 1.000 333 2.167 c 0.12 a Bayron 4.333 1.333 1.000 2.667 2.333 c 0.80 a Verango 8.000 2.333 667 3.000 3.500 b 0.39 a N + E + M 5.667 2.000 1.333 1.333 2.583 c 0.37 a Control 15.667 4.667 2.400 3.333 6.517 a 0.21 a Mean 8.056 A 2.278 B 1.400 C 2.111 B 3.461 0.39 Viable cysts − Mean 936 A 545 B 839 A 583 B 726 − Non-viable cysts − Mean 21.19 A 1.640 A 1.946 A 1.145 A 1.713 − Means followed by the same capital letter in the row and lower case letters in the column did not differ by the Scott-Knott grouping test (p < 0.05). Unlike the first trial, the production of garlic bulbs of the upper classes (50–53 mm and 53–57 mm) did not occur in this last season. The reduced yields and initial populations might explain the lower PPN multiplication (Table 7). Nonetheless, the results for the higher class obtained in this experiment (44–50 mm) were very similar, with differences observed between the treatments, and some treatments providing a good production/classification, something also observed in the first garlic trial: Fluopyram (Verango) and P. lilacinum + T. harzianum + organo-mineral fertilizer (N + E + M) outyielding the others, together with Fluensulfone (Messenger) (Table 8).

Table 8. Garlic yield (kg·ha−1) based on bulb diameter − 2024 season.

Treatment 32–39 mm 39–44 mm 44–50 mm ≤ 32 mm Mean Messenger 5,003.02 aA 5,160.61 aA 1,309.85 aB 853.54 aB 3,081.76 a Abamectin 4,497.48 aA 5,909.10 aA 623.74 bB 787.88 aB 2,954.55 a Bayron 4,858.58 aA 5,679.28 aA 590.92 bB 952.02 aB 3,020.20 a Verango 4,005.05 aA 5,088.38 aA 1,247.48 aB 952.02 aB 2,823.23 a N + E + M 4,057.57 aB 5,554.55 aA 2,316.37 aC 1,063.63 aB 3,248.03 a Control 5,383.83 aA 5,777.77 aA 827.27 bB 1,148.99 aB 3,284.47 a Mean 4,634.26 A 5,528.28 A 1152.60 B 959.68 B 3,068.71 Means followed by the same capital letter in the row and lower case letters in the column did not differ by the Scott-Knott grouping test (p < 0.05). -

In Brazil, garlic is an important winter cash crop, commonly succeeded by summer crops such as soybeans, mainly cultivated for grains, or to supply a rising niche-a vegetable known as edamame. This crop succession affects the population dynamics of the soybean cyst nematode (SCN), a finding reported for the first time in this study. The study also examined the impact of various chemical and biological products that could add to integrated management programs. Overall, the observed differences are intrinsically associated with the fluctuation of the PPN population and nematicide potential control of the products, which are influenced by distinct environmental factors (soil type, organic matter content, pH, temperature, macronutrients, precipitation) that can alter the feeding behavior, making the population unstable across periods[28,29].

The initial decrease of NJ2 in the two garlic trials also occurred for the control treatment. This can be attributed to tillage and the establishment of beds. Turning over the soil is a practice recommended in integrated pest management to eliminate PPN by exposing them to sunlight and high temperatures[30].

Garlic does not serve as a host for the soybean cyst nematode (SCN), which helps to reduce the initial population of cysts in the soil. However, an increase in the SCN population over multiple crop cycles may occur due to alternative hosts or volunteer plants, such as soybean plants and glyphosate-resistant weeds like tropical spiderwort (Commelina benghalensis L.). These plants can remain in the field or arise from lost seeds and the soil seed bank, contributing to the survival and maintenance of this PPN. Therefore, implementing integrated weed management and controlling volunteer herbicide-resistant soybean plants is essential. Eggs inside the cysts in the soil may hatch due to the release of root exudates from nearby plants[31].

Additionally, in this first garlic trial, the number of J2 (NJ2) and viable cysts at the end of the experiment, compared to the sampling done before it was established, remained stable during the cultivation cycle, displaying values close to unity (0.91). This suggests that, under certain circumstances, this PPN could persist in the soil. In the biological cycle of SCN, the females present in the root system will die as the crop develops and detach from the soybean's root system, remaining in the soil as cysts containing eggs. Cysts can survive in moist soil for many years, even when host plants are absent[31].

Mainly in the first garlic trial, the environmental conditions for this crop development were better, even if the larger number of J2 (NJ2) in some treatments was associated with higher yields. This raises the hypothesis of greater development of the garlic plants. Bulb diameter and root area are traits related to the number and length of leaves to plant height. Thus, plants with a greater leaf area tend to have higher production and translocation of photoassimilates for bulb and root growth[32]. Meza et al.[33], evaluating the effect of Fluopyram (Verango), observed an increase in the vigor of tomato plants. As for the garlic productivity increase provided by P. lilacinum + T. harzianum + organo-mineral fertilizer (N + E + M), it can be attributed to the fact that when BCA products like Bacillus are applied in-furrow, they protect plant roots from infections[34]. When used with an organic fertilizer, as in the N + E + M formula, it also has other beneficial effects on plant nutrition[35]. Rigobelo et al.[36] highlighted the benefits of combining P. lilacinum with T. harzianum, which are in the components of the N + E + M formulation.

Related to the soybean crop, Oliveira et al.[35] found that BCA products outperformed abamectin in the management of P. brachyurus in a soybean crop grown in Mato Grosso state in two seasons, stating that abamectin lost effectiveness over time (higher Rf), similar to this study, with other treatments showing better control at 120 d after sowing. Dosages of abamectin reduced the number of females and eggs, and Abamectin in combination with P. lilacinum shows promise for managing SCN in soybeans in Urutaí-GO, Brazil[37], supporting the results of this study.

Various strains of Bacillus, including B. subtilis, reduced SCN density in soybean plants in a greenhouse, micro-trials, and field tests, with varying levels of efficacy[38]. Beeman & Tylka[39] pointed to Fluopyram use as a seed treatment nematode-protectant for soybeans to aid SCN control. Dias-Arieira et al.[40] verified that the combination of P. lilacinum + T. harzianum + moss, similar to the ingredients of the N + E + M treatment, promoted the control of P. brachyurus and increased yield in soybeans. Roth et al.[41] described Rf values consistently greater than 1, whether or not the soybean seeds were treated with fluopyram (Verango) in Michigan, USA, indicating that SCN populations still increased in the presence of this nematicide, as occurred in this study. This reinforces the effectiveness and longer half-life of the abovementioned nematicide in tropical soils[42]. Meza et al.[33], evaluating the effect of Fluopyram (Verango), described an increase in the vigor of tomato plants, which could explain or have had the same response in the soybean trial. In addition, the fact that nitrogen + amino acids (Bayron) promoted an increase in soybean productivity, and not in the control of SCN, is solely due to its composition, which in this case had a positive effect as a fertilizer but not as a nematicide.

Thus, in the garlic-soybean-garlic succession dynamic, the management of soil tillage for garlic planting, which allows for a fallow period, but especially the use of products with nematicide potential such as Fluopyram and biologically based products like P. lilacinum + T. harzianum + organo-mineral fertilizer, proved effective in this context. They resulted in a decrease in the number of J2 and females and increased productivity for both crops. Furthermore, they can be components of an integrated disease management system that employs sustainable practices to control this PPN in tropical regions.

-

Although garlic is not a host for SCN, this PPN could survive in the soil and multiply in volunteer glyphosate-resistant soybean plants or weeds, which help maintain its population. Turning over the soil and allowing a fallow period for garlic production can help reduce the population. Fluopyram, P. lilacinum + T. harzianum + fertilizer also reduced SCN. Hence, garlic/soybean integrated disease management programs can gain from new nematicides and biological control agents.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Pinheiro JB; data collection: Santos LA, Mendes PAS, Rafael FS, Pereira JL, Amorim MHN; analysis and interpretation of results: Pinheiro JB, Silva GO, Melo RAC; draft manuscript preparation: Pinheiro JB, Santos LA, Mendes PAS, Rafael FS, Pereira JL, Amorim MHN, Silva GO, Melo RAC. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

We would like to express our gratitude to João Wandelci Romeiro of Paineiras Farm and the Brazilian National Association of Garlic Producers (ANAPA).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Pinheiro JB, da Silva GO, de Castro e Melo RA, Santos LA, da Silva Mendes PA, et al. 2025. Harnessing the role of garlic and control strategies in a crop succession with soybean affecting Heterodera glycines dynamics. Technology in Agronomy 5: e017 doi: 10.48130/tia-0025-0011

Harnessing the role of garlic and control strategies in a crop succession with soybean affecting Heterodera glycines dynamics

- Received: 24 May 2025

- Revised: 05 September 2025

- Accepted: 16 September 2025

- Published online: 20 November 2025

Abstract: Garlic is a significant winter cash crop in Brazil, succeeded by soybeans during the summer, providing economic benefits and other advantages. Soybeans are primarily cultivated for their seeds, but they can also be harvested as a vegetable known as edamame. Since there are currently no studies regarding the soybean cyst nematode (SCN)–Heterodera glycines (Ichinohe) in garlic-soybean-garlic crop succession, this study aimed to explore its role in addition to control strategies that affect SCN dynamics. The trials occurred in a central-pivot irrigation area naturally infested with SCN race 5 in Campo Alegre de Goiás, GO, Brazil, in 2023 and 2024. Six treatments were employed: (1) Bacillus subtilis; (2) Abamectin; (3) Nitrogen + amino acids; (4) Fluopyram; (5) Purpureocillium lilacinum + Trichoderma harzianum + organo-mineral fertilizer; and (6) Control. Although garlic is not a host for SCN, this PPN could survive in the soil and multiply in volunteer glyphosate-resistant soybean plants or weeds, which help maintain its population. Still, turning over the soil for garlic planting and allowing a fallow period reduced the population. Fluopyram and P. lilacinum + T. harzianum + organo-mineral fertilizer, particularly Fluopyram, provided a decrease in the number of J2 and females as well as higher productivity for both crops. In this context, sustainable practices can help reduce nematode populations, and biological products may play a crucial role in integrated management systems within this tropical region.

-

Key words:

- Integrated disease management /

- Allium sativum L. /

- Glycine max (L.) Merr.