-

As one of the world's most important staple crops, rice (Oryza sativa L.) provides food for more than 3 billion people worldwide[1]. In China, the rice yield per unit area exceeded 7.06 t·ha−1 in 2022[2], reaching an advanced level worldwide due to rapid progress in cultivation and breeding technologies. Located in the arid region of Northwest China, Xinjiang is rich in light and heat resources and has the potential to produce high rice yields[3,4]. However, scarce rainfall and excessive evaporation lead to water shortages, severely limiting large-scale conventional rice production in this area[5]. According to statistics, conventional rice production requires two to three times the amount of water needed by other cereal crops, such as wheat, making rice production unsustainable in the arid region of Xinjiang[6]. Compared with conventional methods, drip irrigation, which delivers water directly to the root zone, can reduce water consumption by 60%, fertilizer use by 20%, and production costs by more than 17.2%[4,7,8]. For this reason, the development of novel water-saving rice cultivation techniques, such as drip-irrigation, has become an effective way to expand rice planting areas and ensure the food supply in this region.

Nitrogen (N) is the nutrient element required in the greatest amount for plant growth[9]. In traditional paddy fields, the anaerobic conditions formed by long-term flooding lead to nitrogen being absorbed mainly in the form of ammonium (NH4+), which is closely related to the adaptive domestication of rice in swamp environments[10]. Rice can also absorb and utilize nitrate (NO3−). Oxygen (O2) secretion by rice roots promotes the growth and reproduction of nitrifying microorganisms in the root zone, oxidizing NH4+ to NO3−, which is then directly absorbed by rice[11]. A previous study by Kirk also suggested that approximately 1/3 of the total nitrogen uptake by rice comes from NO3−[12]. However, under drip-irrigation conditions, where water is delivered directly to the root zone, the water transport pattern is altered. Compared with traditional flooding, drip-irrigation changes soil aeration and results in the concentration of water in the root zone, affecting the nitrogen distribution. The subsequent alteration in the soil redox potential further influences the conversion of ammonium to nitrate, shifting the nitrogen forms in the root zone from being dominated by NH4+ to being dominanted by both NH4+ and NO3−[13]. However, although drip-irrigation affects nitrogen absorption in rice, the physiological mechanisms through which drip-irrigated rice responds to changes in nitrogen forms remain unclear.

Rice yields primarily depend on leaf photosynthesis after heading, and the stability of leaf function during this stage is closely related to the nitrogen supply. In addition to the amount and management of nitrogen application, a plant's preference for specific nitrogen forms also regulates its photosynthetic physiological processes through signalling molecules[14]. Differences in nitrogen forms primarily affect the net photosynthetic rate by modulating stomatal conductance and intercellular CO2 concentration[15]. Xie et al.[16] suggested that this phenomenon may be related to the increase in rhizosphere pH caused by nitrate uptake, which alters iron availability and mobility in the leaf mesophyll apoplast through signalling molecules, thereby inhibiting chlorophyll synthesis and the photosynthetic rate. Moreover, some studies have shown that increasing nitrate application can increase the maximum photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm) and carboxylation rate in rice[14]. Additionally, plant antioxidant enzymes and hormones play important regulatory roles in the response of photosynthetic physiological characteristics to varying nitrogen forms[17]. Zeng et al.[18] proposed that NH4+ maintains leaf structural stability by enhancing antioxidant enzyme activity; Heuermann et al.[19] reported that NH4+ and NO3− are likely to promote the synthesis of auxin and cytokinin, respectively, thereby affecting the chlorophyll content and photosynthetic capacity; Krouk[20] reported that NO3− affects stomatal opening and closing by increasing the leaf abscisic acid (ABA) content and regulating the leaf photosynthetic capacity. However, studies on how nitrogen form differences systematically regulate photosynthetic physiology, nitrogen metabolism, and hormone balance and their contributions to yield formation in rice are limited under the combined effects of altered water-fertilizer supply patterns due to drip irrigation and the climatic characteristics of low rainfall and high evaporation in Xinjiang.

Extensive research has been conducted on the effects of nitrogen forms on rice growth, but most related studies have focused on laboratory simulations or conventional paddy fields. Under drip-irrigation conditions, changes in the water-fertilizer supply and root zone environment may lead to significant differences in nitrogen absorption and transformation when compared to traditional flooding. However, the mechanisms through which different nitrogen forms affect yield through the regulation of physiological processes such as photosynthetic characteristics, nitrogen metabolic enzyme activity, and endogenous hormone balance under drip-irrigation are still not fully understood. Therefore, this study employs correlation analysis and partial least squares path modelling (PLS‒PM) to analyse the physiological differences and adaptive mechanisms of rice cultivars with different nitrogen efficiencies in response to different nitrogen forms under drip-irrigation, aiming to provide a theoretical basis for efficient nutrient utilization by drip-irrigated rice in arid areas.

-

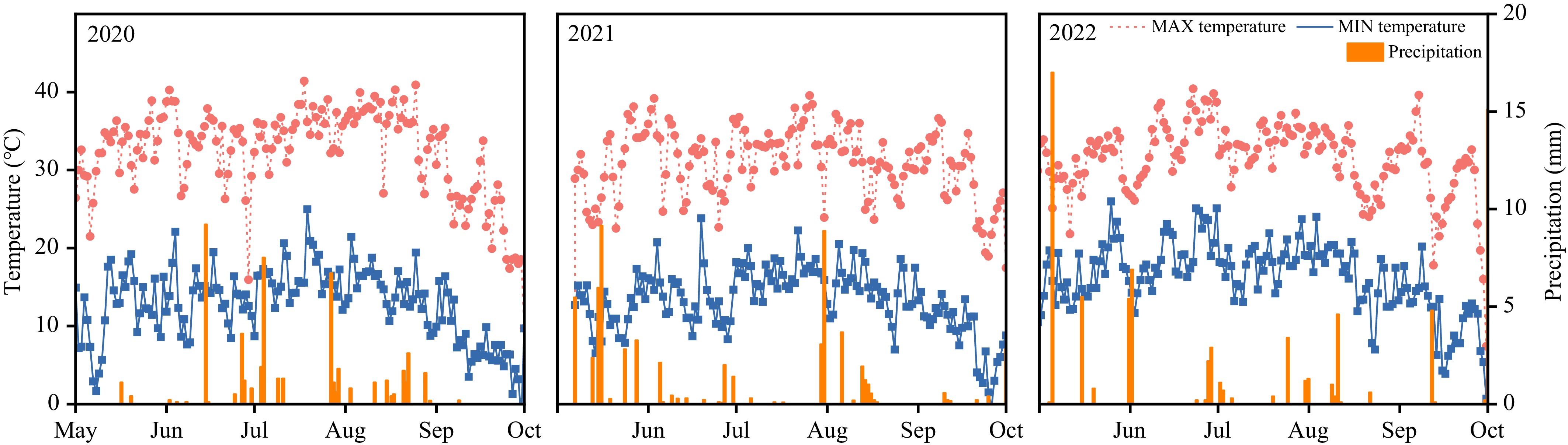

This experiment was carried out at the Xinjiang Academy of Agricultural and Reclamation Sciences (Shihezi, Xinjiang, 44°18' N, 86°03' E) from 2020–2022. The study area has a typical arid and semiarid continental climate, with scarce precipitation and concentrated light and heat. The region is characterized by an annual average total solar radiation of 5,133.06 MJ·m−2 (3,614.25 MJ·m−2 during the growing season), with climatic conditions featuring an average annual temperature of 6.5–8.1 °C, precipitation of 180 mm, and evaporation of approximately 1,500 mm, while the crop growing seasons from 2020–2022 recorded three, five, and five effective precipitation events exceeding 5 mm, average daily maximum temperatures of 32.29, 30.72, and 31.79, and average daily minimum temperatures of 12.78, 13.20, and 16.53 °C, respectively (Fig. 1). The soil tested was a Calcaric Fluvisol, with a pH of 8.37, organic matter content (OMC) of 1.07 g·kg−1, total N of 0.68 g·kg−1, available phosphorus (P) of 36 mg·kg−1, and available potassium (K) of 204 mg·kg−1.

Experimental design and treatments

-

The drip-irrigated rice cultivars included high-NUE (T-43) and low-NUE Liangxiang 3 (LX-3) cultivars. Four treatments were established: no nitrogen application (CK), urea application (Urea), ammonium application (NH4+), and nitrate application (NO3−), with a uniform pure nitrogen application rate of 300 kg·ha−1. The corresponding nitrogen forms for the Urea, NH4+, and NO3− treatments were CH4N2O (46% N), (NH4)2SO4 (21% N), and Ca(NO3)2 (12% N), respectively. Phosphorus and potassium fertilizers were applied as KH2PO4 at a rate of 225 kg·ha−1. The Urea and NH4+ treatments were supplemented with 1% 3,4-dimethylpyrazole phosphate (DMPP) and 0.5% N-(n-butyl) thiophosphoric triamide (NBPT) to control urease catalysis and nitrification. The planting pattern followed the configuration described by Tang et al.[21], with a 10–26–10 cm arrangement, one film and two tubes covering eight rows, a film width of 1.45 m, a plant-to-plant spacing of 10 cm, an inlaid drip-irrigation belt, an emitter spacing of 30 cm, and an emitter flow rate of 2.1 L·h−1. A split-plot design was used, with a plot area of 60 m2 and three replications. Sowing was carried out on April 28, 2020, May 1, 2021, and May 1, 2022, with a single operation for pipelaying, film mulching, on-demand sowing, and soil covering. The sowing depth ranged from 1.5 to 2.0 cm, and the covering soil thickness ranged from 1.0 to 1.5 cm. The plants were harvested on September 30. The fertilizers were applied seven times during the growth period through integrated water and fertilizer drip-irrigation, with 10,200 m3·ha−1 total irrigation. The specific nitrogen application rates and irrigation volumes are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Disease, insect, weed, and pest management practices were the same as those used in field production practices.

Measurement items and methods

-

From 2020–2021, fully expanded flag leaves were selected and marked between 11:00 and 13:00 at heading (HS; T-43 and LX-3 headed on 14 and 19 July 2020 and 18 and 24 July 2021, respectively) and 20 d after heading (20 DAH). A portable photosynthesis measurement system (LI-6400XT, LICOR, USA) was used with a light intensity of 1,800 µmol·m−2·s−1 and a sample chamber CO2 concentration of 400 µmol·mol−1 to measure the net photosynthetic rate (Pn), stomatal conductance (Gs), intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci), and transpiration rate (Tr).

At the HS and 20 DAH, the marked flag leaves were selected for a 30-min dark adaptation period (dark-adapted leaf clip, DLC-B). A portable chlorophyll fluorometer (PAM-2500, Heinz Walz GmbH, Germany) was used to measure the initial fluorescence (F0) and maximum fluorescence (Fm). The actinic light (PAR = 617 mmol·m−2·s−1) was subsequently turned on to measure the minimum fluorescence yield (F0′) and maximum fluorescence yield (Fm′). The Fv/Fm, actual quantum efficiency (ΦPSII), photochemical quenching (qP), and nonphotochemical quenching (qN) for photosystem II were calculated as follows[22]:

$ {F}_{\mathrm{V}}/{F}_{\mathrm{m}}=\dfrac{({F}_{\mathrm{m}}-{F}_{0})}{{F}_{\mathrm{m}}} $ (1) $ \mathrm{Y}(\mathrm{II})=\dfrac{\left(F_{\mathrm{m}}^{'}-{F}^{'}\right)}{F_{\mathrm{m}}^{'}} $ (2) $ \mathrm{q}P=\dfrac{\left(F_{\mathrm{m}}^{'}-{F}^{'}\right)}{\left(F_{\mathrm{m}}^{'}-F_{0}^{'}\right)} $ (3) $ \mathrm{q}N=1-\dfrac{\left(F_{\mathrm{m}}^{'}-F_{0}^{'}\right)}{({F}_{\mathrm{m}}-{F}_{0})} $ (4) At the HS and 20 DAH stage, the leaves previously used for gas exchange measurements were excised and divided into four portions. One portion was used to measure the absorbance values at 663 and 645 nm via an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (UV-1800) to calculate the contents of Chl a and Chl b. The other three portions were stored at −80 °C, and one portion was sent to the College of Agronomy and Biotechnology, China Agricultural University, for the determination of ABA, gibberellin A3 (GA3), zeatin riboside (ZR), and indole acetic acid (IAA) contents via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). One portion was used to measure the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), and catalase (CAT)[23], and the third portion was used to determine the activities of nitrate reductase (NR), glutamine synthetase (GS), and glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH). The determination methods followed those of Zhao et al.[4].

At the HS and 20 DAH stage, five representative rice plants were collected according to the average number of tillers and divided into three parts: the stem sheath, leaves, and panicle. The samples were placed in an oven at 105 °C for 30 min to kill the green material, dried to a constant weight at 85 °C, and finally weighed and recorded. After being weighed, the rice leaves were ground and passed through a 0.246 mm sieve and then digested via the H2SO4–H2O2 method, and the leaf N content was determined via a FOSS 8400 semimicro Kjeldahl nitrogen analyser.

At the maturity stage, three rice plants with consistent growth were selected from each treatment; the number of effective panicles, 1,000-grain weight, spikelets per panicle, and filled-grain percentage were measured. The rice yield was calculated on the basis of the conversion of a moisture content of 14.5%, with three replications. After the yield measurement, the nitrogen partial factor of production (NPFP) was calculated. The NPFP (kg·kg−1) was calculated as follows:

$ \text{NPFP}=\dfrac{\mathrm{Y}}{\text{NAR}} $ (5) where, Y represents the grain yield under nitrogen fertilization treatment (kg·ha−1), and NAR represents the nitrogen application rate (kg·ha−1).

Data analysis

-

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan's test were performed via IBM SPSS Statistics, version 27.0 (IBMCorp., Armonk, NY, USA). Charts were created via Excel 2019 (Microsoft, Bothell, WA, USA) and Origin 2022 (OriginLab, Northampton, USA). The results are expressed as the means ± standard errors, and the significance level was set at p < 0.05. The 'plspm' package in R (version 4.3.3, R Core Team, 2024) was used for partial least squares path modelling analysis (PLS−PM) and plotting.

-

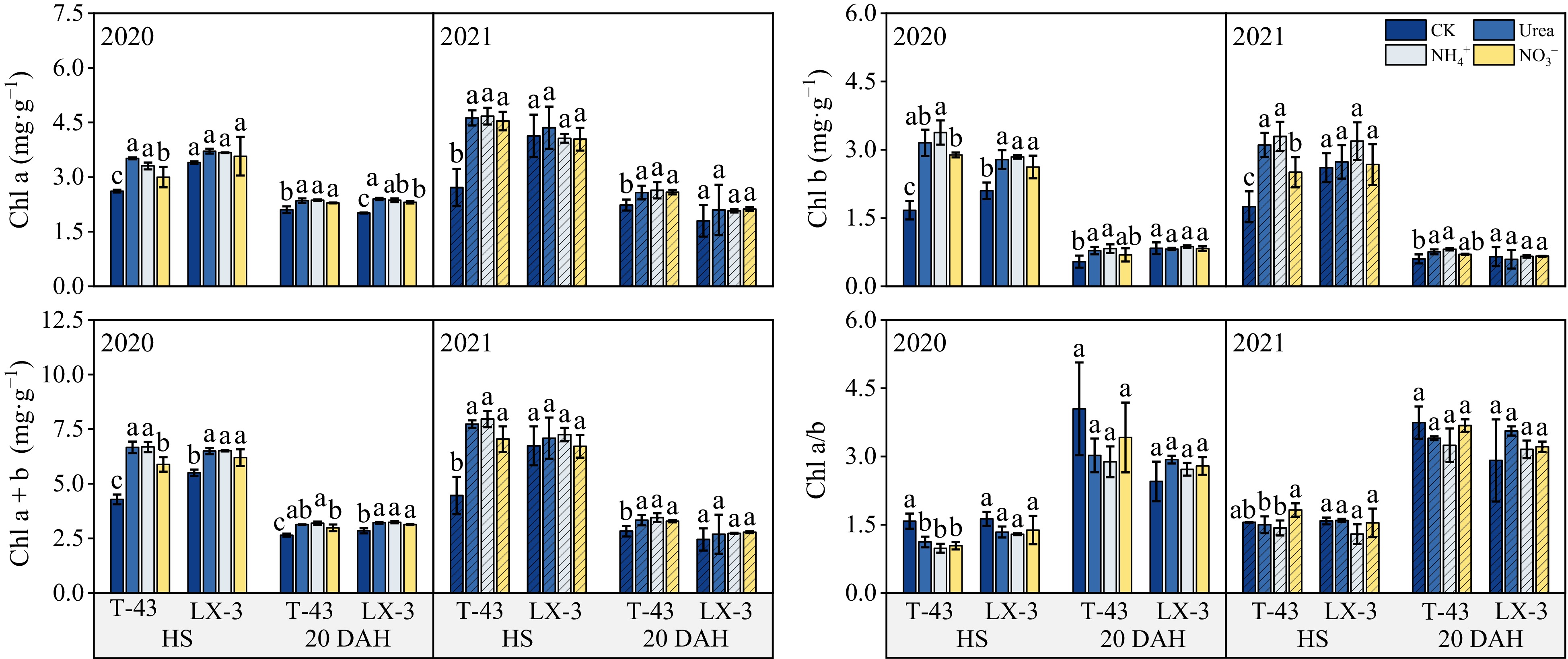

Compared with those in the CK treatment, N application increased the Chl a, Chl b, and Chl a + b contents in both cultivars under N application tended to increase consistently across the years; in addition, the chlorophyll content in each treatment was lower at 20 DAH than at HS (Fig. 2). In terms of the N form, the Chl a content was the highest under the Urea treatment, but there was no significant difference between the Urea and NH4+ treatments (p < 0.05). The Chl b and Chl a + b contents were highest under NH4+, i.e., 7.79% and 1.67% higher than those under the Urea, respectively, and 6.96% and 7.89% higher than those under NO3−, respectively. In addition, at HS and 20 DAH, the Chl a/b values under the Urea and NO3− treatments were greater than those under the NH4+, but there was no significant difference among the treatments. In terms of the cultivars, under CK, the Chl a, Chl b, and Chl a + b contents of T-43 were greater than those of LX-3; under N application, the Chl a, Chl b, and Chl a + b contents of T-43 were 4.56%, 7.65%, and 5.69% greater than those of LX-3, respectively.

Figure 2.

Effects of N form on the chlorophyll content of drip-irrigated rice leaves. Chl a, chlorophyll a; Chl b, chlorophyll b; Chl a + b, chlorophyll a + b; Chl a/b, chlorophyll a/b. Different letters indicate that the same cultivar is significantly different within the same year (p = 0.05).

Rice leaf gas exchange parameters: Pn, Gs, Ci, and Tr

-

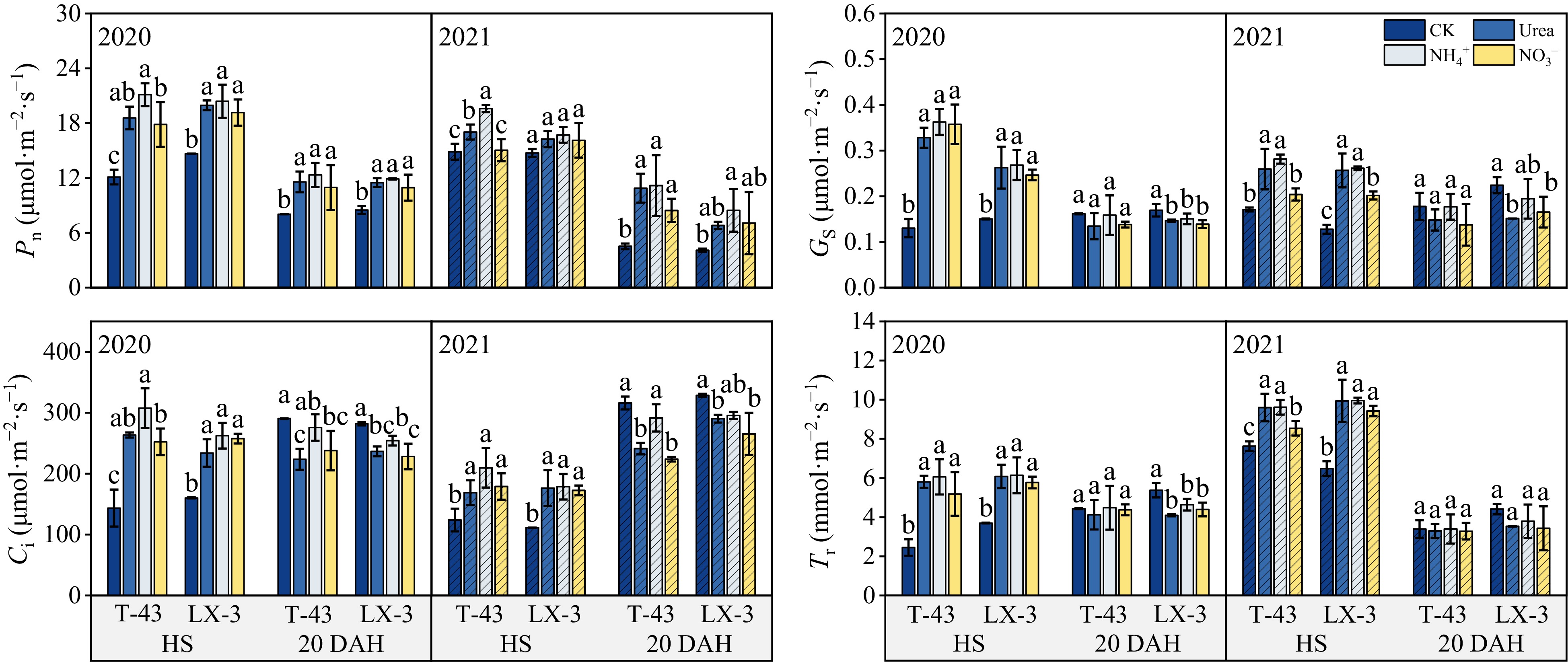

Compared with those in the CK treatment, the Pn, Gs, Ci, and Tr contents in the leaves of both cultivars at HS significantly increased (p < 0.05) under N application; at 20 DAH, the Ci and Tr contents of the leaves in the CK treatment were greater than those in the other treatments (Fig. 3). With respect to the N form, the Pn decreased in the order of NH4+ > Urea > NO3− at both HS and 20 DAH; the Gs and Ci contents were both the highest under NH4+; however, there was no significant difference between the Urea and NO3− treatments, and the Tr content was not significantly different between the NH4+, Urea, and NO3− treatments. In terms of the different cultivars, at HS under each N treatment, the average values of Pn, Gs, and Ci in T-43 were 0.56%, 19.78%, and 7.77% greater than those in LX-3, respectively, and the Tr of T-43 was 5.31% lower than that of LX-3. At 20 DAH under each N application, the average Pn of T-43 was 15.38% greater than that of LX-3, whereas the Ci and Tr of T-43 were 4.85% and 3.88% lower than those of LX-3, respectively.

Figure 3.

Effects of N form on the photosynthetic parameters of drip-irrigated rice leaves. Pn, net photosynthetic rate; Gs, stomatal conductance; Ci, intercellular CO2 concentration; Tr, transpiration rate. Different letters indicate that the values for the same cultivar are significantly different within the same year (p = 0.05).

Rice chlorophyll fluorescence parameters

-

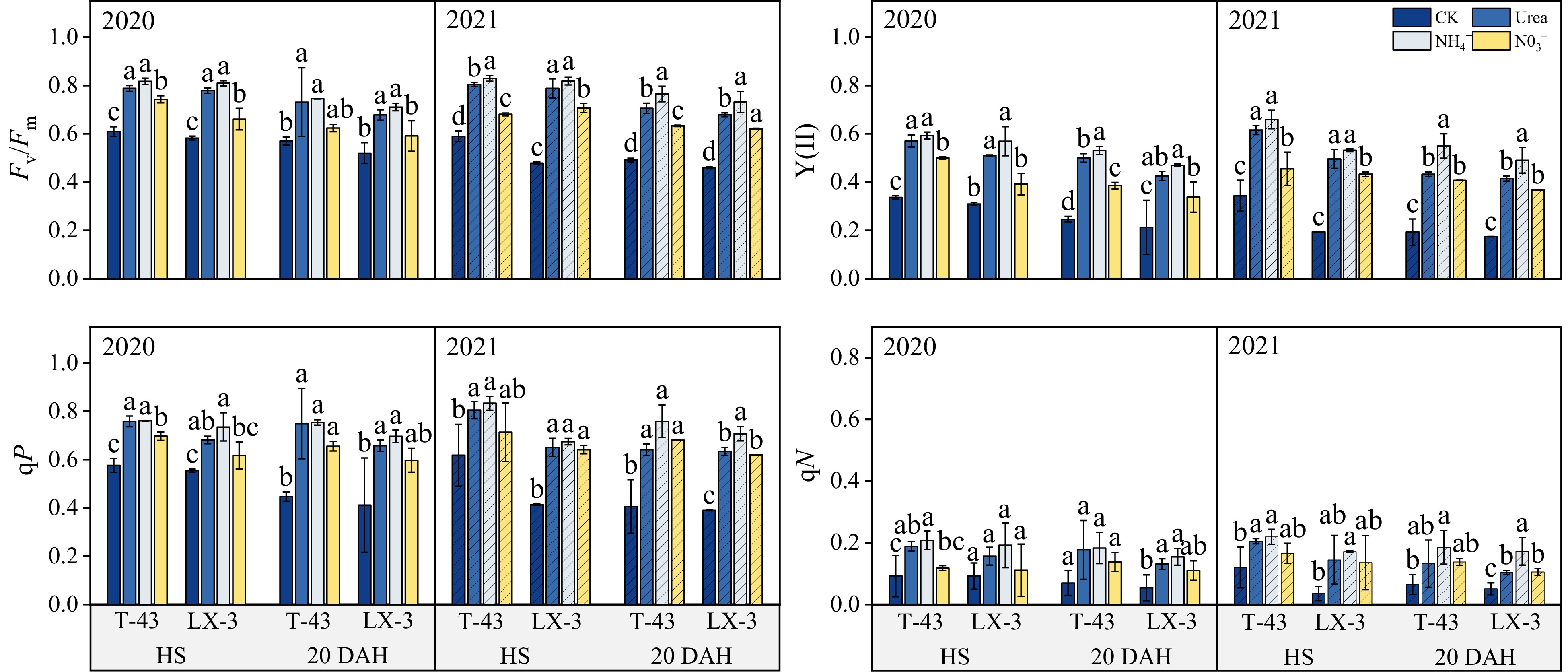

Compared with those in the CK treatment, the Fv/Fm, Y(II), qP, and qN in both cultivars significantly increased under N application (P < 0.05), with a consistent trend across the years (Fig. 4). In terms of N forms, in the HS treatment, the Fv/Fm, Y(II), qP, and qN under the NH4+ treatment were 17.67%, 33.87%, 14.81%, and 54.68% greater than those under the NO3− treatment, respectively, but there were no significant differences in Y(II), qP, and qN between the NH4+ and Urea treatments. At 20 DAH, the Fv/Fm, Y(II), qP, and qN under NH4+ were greater than those under the Urea and NO3−, and there was no significant difference in the qP and qN did not significantly differ between the NO3− and Urea treatments (p < 0.05). The average values of Fv/Fm, Y(II), qP, and qN of T-43 under each N application treatment were 5.18%, 13.92%, 9.79%, and 18.35% greater than those of LX-3 at HS, respectively, and 1.69%, 14.16%, 12.87%, and 25.64% greater than those of LX-3 at 20 DAH, respectively.

Figure 4.

Effects of N form on chlorophyll fluorescence parameters in drip-irrigated rice leaves. Fv/Fm, maximal photochemical efficiency of photosystem II; Y(II) actual photochemical efficiency of photosystem II; qP, photochemical quenching; and qN, nonphotochemical quenching. Different letters indicate that the values for the same cultivar are significantly different within the same year (p = 0.05).

Rice leaf antioxidant enzyme activity

-

Compared with those of the CK treatment, N application significantly increased the CAT activity in the leaves of both cultivars (p < 0.05); the SOD and POD activities of the leaves of the LX-3 cultivar at the heading stage under CK were greater than those under N application (Supplementary Fig. S1). SOD activity in the leaves was highest under NH4+, i.e., 9.36% and 12.59% higher than that under Urea and NO3− treatments, respectively. The activities of POD and CAT decreased in the order of NH4+ > Urea > NO3− at both HS and 20 DAH, with no significant difference between the NH4+ and Urea treatments; at 20 DAH, POD activity was not significantly different between the NH4+ and Urea treatments but was greater in both treatments than in the NO3− treatment. In terms of the cultivars subjected to HS under each N treatment, the POD and CAT activities in T-43 were 13.06% and 14.19% higher than those in LX-3, respectively, while the SOD activity in T-43 was lower than that in LX-3; at 20 DAH, the SOD, POD, and CAT activities were all lower in the leaves of T-43 than they were in those of LX-3.

Rice leaf endogenous hormone contents

-

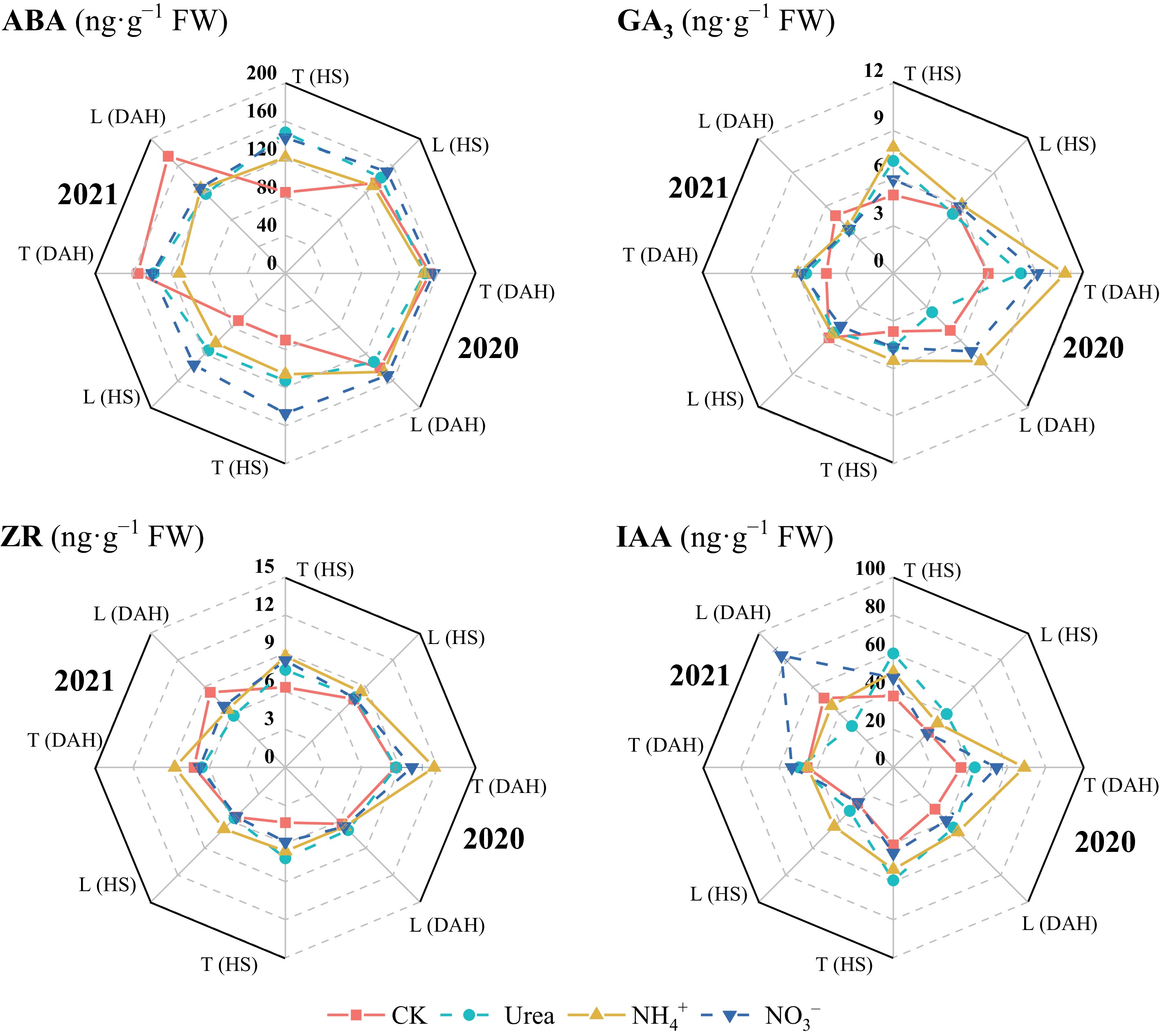

Compared with the CK treatment, N application increased the GA3, ZR, and IAA contents in the leaves of both cultivars (Fig. 5), whereas the ABA content in LX-3 at 20 DAH in 2021 was significantly greater under no N application than under the N treatments (p < 0.05). In terms of the N form, except at 20 DAH in 2021, the ABA content in the leaves was greatest under the NO3− treatment, followed by the Urea treatment and then the NH4+ treatment. The GA3 content was highest under NH4+ and was significantly greater than that under Urea and NO3− in 2020. The highest ZR content was reached under NH4+, i.e., 13.71% and 11.15% higher than that under Urea and NO3− treatments, respectively. The IAA content was the highest under Urea treatments at HS and under NO3− treatment at 20 DAH, i.e., 10.79% and 37.12% higher than that under NH4+ and Urea, respectively. In terms of cultivar, the average ABA, GA3, ZR, and IAA contents in T-43 were 0.11%, 9.15%, 6.09%, and 57.30% greater than those in LX-3 at HS under each N treatment, respectively, and 4.75%, 50.02%, 33.83%, and 7.56% greater than those in LX-3 at 20 DAH, respectively.

Figure 5.

Effects of N forms on the hormone contents of drip-irrigated rice leaves. HS, heading stage; DAH, 20 d after heading. ABA, abscisic acid; GA3, gibberellin; ZR, zeatin riboside; IAA, indole-3-acetic acid. Different letters indicate that the values for the same cultivar are significantly different within the same year (p = 0.05).

Rice leaf N metabolic enzyme activity

-

According to the data in Supplementary Table S2, cultivar (C) had a significant effect on leaf GS and NR, whereas the amount of nitrogen forms (N) applied had a highly significant effect on GS, GDH, and NR (p < 0.05). Compared with the CK, nitrogen application significantly increased the GS, GDH, and NR in the leaves of the two cultivars, and the trend was essentially consistent across years. Among the different N forms, at HS, the GS, GDH, and NR under the NH4+ treatment was 36.83%, 29.45%, and 10.18% greater than those under the NO3− and 38.38%, 33.47%, and 11.77% greater than those under the Urea treatment, respectively; at 20 DAH, the GS, GDH, and NR under the NH4+ treatment were 26.99%, 35.06%, and 26.40% greater than those under the NO3− and 44.85%, 35.96%, and 30.83% greater than those under Urea, respectively. Among the cultivars, the average values of GS, GDH, and NR for T-43 under all the treatments were 8.82%, 4.07%, and 9.32% greater than those for LX-3, respectively.

Rice leaf N content

-

As shown in Supplementary Fig. S2, cultivar and N form had highly significant effects on total N accumulation in the leaves of drip-irrigated rice, but the interaction effect between cultivar and N form was not significant (p < 0.05). Compared with the CK treatment, the application of nitrogen significantly increased nitrogen accumulation in the leaves of the two cultivars (p < 0.05). Among the nitrogen forms, at HS, the leaf N accumulation under the NH4+ treatment was 7.64% greater than that under the NO3− treatment and 10.49% greater than that under the Urea; at 20 DAH, the accumulation of N under the NH4+ was 12.95% greater than that under the NO3− and 11.78% greater than that under the Urea treatment. Among the cultivars, at HS and 20 DAH, the leaf N content of T-43 under all the treatments was 12.02% and 20.21% greater than that of LX-3, respectively.

Rice biomass accumulation

-

According to the data in Table 1, cultivar (C) had a highly significant effect on accumulation of leaves, panicles, and whole plants; nitrogen form (N) had a highly significant effect on accumulation of stems and sheaths, panicles, and whole plants; and C × N had no significant effect (p < 0.05) on dry matter accumulation in stems and sheaths, leaves, panicles, or whole plants. Compared with that in the CK treatment, the nitrogen form significantly increased dry matter accumulation in all aboveground plant organs of both T-43 and LX-3, with consistent trends across years. Among the nitrogen application forms, under HS, the total plant dry matter accumulation under the NH4+ was 0.26%–2.47% greater than that of NO3− and 2.16%–6.26% greater than that of Urea, whereas the dry matter accumulation in panicles was also greater than that under the NO3− and Urea, and the dry matter accumulation in stems and sheaths was lower than that of NO3− and Urea. At 20 DAH, the dry matter accumulation in leaves and panicles under the NH4+ treatment was greater than that under the NO3− and Urea treatments. Additionally, compared with that under the NO3− and Urea treatments, the proportion of panicle dry matter under NH4+ at HS increased by 16.02% and 9.29%, respectively, and at 20 DAH, it increased by 5.65% and 2.37% compared with that under the NO3− and Urea treatments, respectively. Compared with that in the stems and sheaths of LX-3, the dry matter accumulation in the stems and sheaths, leaves, panicles, and whole plants of T-43 increased by 4.60%, 15.83%, 21.83%, and 11.43%, respectively.

Table 1. Effects of N form on the mass of drip-irrigated rice.

Year Cultivar Nitrogen forms HS 20 DAH Stem

(t·ha−1)Leaf

(t·ha−1)Panicle

(t·ha−1)Total

(t·ha−1)Stem

(t·ha−1)Leaf

(t·ha−1)Panicle

(t·ha−1)Total

(t·ha−1)2020 T-43 CK 5.48 ± 0.37 c 3.11 ± 0.19 b 1.98 ± 0.12 b 10.56 ± 0.59 b 5.38 ± 0.25 b 2.14 ± 0.14 b 3.67 ± 0.03 b 11.18 ± 0.16 b Urea 6.83 ± 0.19 a 3.57 ± 0.6 ab 2.54 ± 0.45 ab 12.94 ± 0.67 a 7.84 ± 0.17 a 3.45 ± 0.18 a 5.60 ± 0.27 a 16.90 ± 0.00 a NH4+ 6.14 ± 0.27 b 4.28 ± 0.74 a 2.84 ± 0.37 a 13.26 ± 0.10 a 7.61 ± 0.50 a 3.77 ± 0.29 a 5.96 ± 0.32 a 17.33 ± 0.85 a NO3− 6.30 ± 0.35 ab 4.23 ± 0.08 a 2.45 ± 0.05 ab 12.98 ± 0.30 a 7.81 ± 0.30 a 3.42 ± 0.08 a 5.62 ± 0.42 a 16.85 ± 0.46 a LX-3 CK 4.65 ± 0.04 c 2.26 ± 0.04 b 1.35 ± 0.01 b 8.25 ± 0.02 c 4.89 ± 0.25 b 2.02 ± 0.10 b 2.84 ± 0.33 c 9.75 ± 0.52 c Urea 6.43 ± 0.09 a 2.98 ± 0.40 ab 2.08 ± 0.12 a 11.50 ± 0.23 a 6.62 ± 0.07 a 2.65 ± 0.12 a 4.10 ± 0.15 b 13.38 ± 0.11 b NH4+ 5.92 ± 0.13 b 3.20 ± 0.38 a 2.41 ± 0.24 a 11.53 ± 0.25 a 6.43 ± 0.27 a 2.84 ± 0.15 a 4.93 ± 0.25 a 14.20 ± 0.04 a NO3− 5.67 ± 0.26 b 3.16 ± 0.63 a 2.22 ± 0.27 a 11.06 ± 0.18 b 6.43 ± 0.34 a 2.69 ± 0.15 a 4.71 ± 0.37 a 13.82 ± 0.55 ab 2021 T-43 CK 5.55 ± 0.38 b 2.90 ± 0.03 b 1.77 ± 0.08 c 10.23 ± 0.46 b 7.02 ± 0.81 a 2.73 ± 0.19 c 4.62 ± 0.46 b 14.37 ± 1.24 b Urea 6.81 ± 0.56 a 3.19 ± 0.21 a 2.11 ± 0.18 bc 12.11 ± 0.54 a 7.34 ± 0.12 a 3.01 ± 0.16 bc 5.05 ± 0.21 ab 15.40 ± 0.32 ab NH4+ 6.52 ± 0.31 a 3.25 ± 0.23 a 2.63 ± 0.43 a 12.40 ± 0.26 a 7.42 ± 0.34 a 3.49 ± 0.17 a 5.68 ± 0.35 a 16.59 ± 0.68 a NO3− 6.80 ± 0.33 a 2.49 ± 0.17 a 2.39 ± 0.23 ab 11.67 ± 0.42 a 7.60 ± 0.34 a 3.22 ± 0.07 ab 5.42 ± 0.43 a 16.24 ± 0.61 a LX-3 CK 6.66 ± 0.35 a 2.81 ± 0.09 a 1.00 ± 0.13 b 10.47 ± 0.30 a 5.89 ± 0.35 b 2.26 ± 0.08 b 3.59 ± 0.50 b 11.74 ± 0.91 b Urea 7.02 ± 0.18 a 3.02 ± 0.27 a 1.13 ± 0.08 ab 11.17 ± 0.38 a 7.88 ± 0.05 a 3.09 ± 0.30 a 5.59 ± 0.12 a 16.56 ± 0.44 a NH4+ 6.82 ± 0.84 a 3.06 ± 0.06 a 1.37 ± 0.20 a 11.25 ± 0.80 a 7.70 ± 0.27 a 3.17 ± 0.06 a 5.69 ± 0.33 a 16.57 ± 0.04 a NO3− 7.04 ± 0.09 a 2.84 ± 0.06 a 1.08 ± 0.21 ab 10.97 ± 0.30 a 7.63 ± 0.25 a 3.06 ± 0.35 a 5.43 ± 0.42 a 16.12 ± 0.32 a p-Value Cultivar (C) ns ** ** ** ** ** ** ** Nitrogen forms (N) ** * ** ** ** ** ** ** C × N ns ns ns ns ns ns ns ns HS, heading stage; 20 DAH, 20 d after heading. Different letters indicate that the values for the same cultivar were significantly different within the same year (p = 0.05). * and ** indicate significance at the p = 0.05 and 0.01 levels, respectively, and NS indicates nonsignificance at the p = 0.05 level. Rice yield and NPFP

-

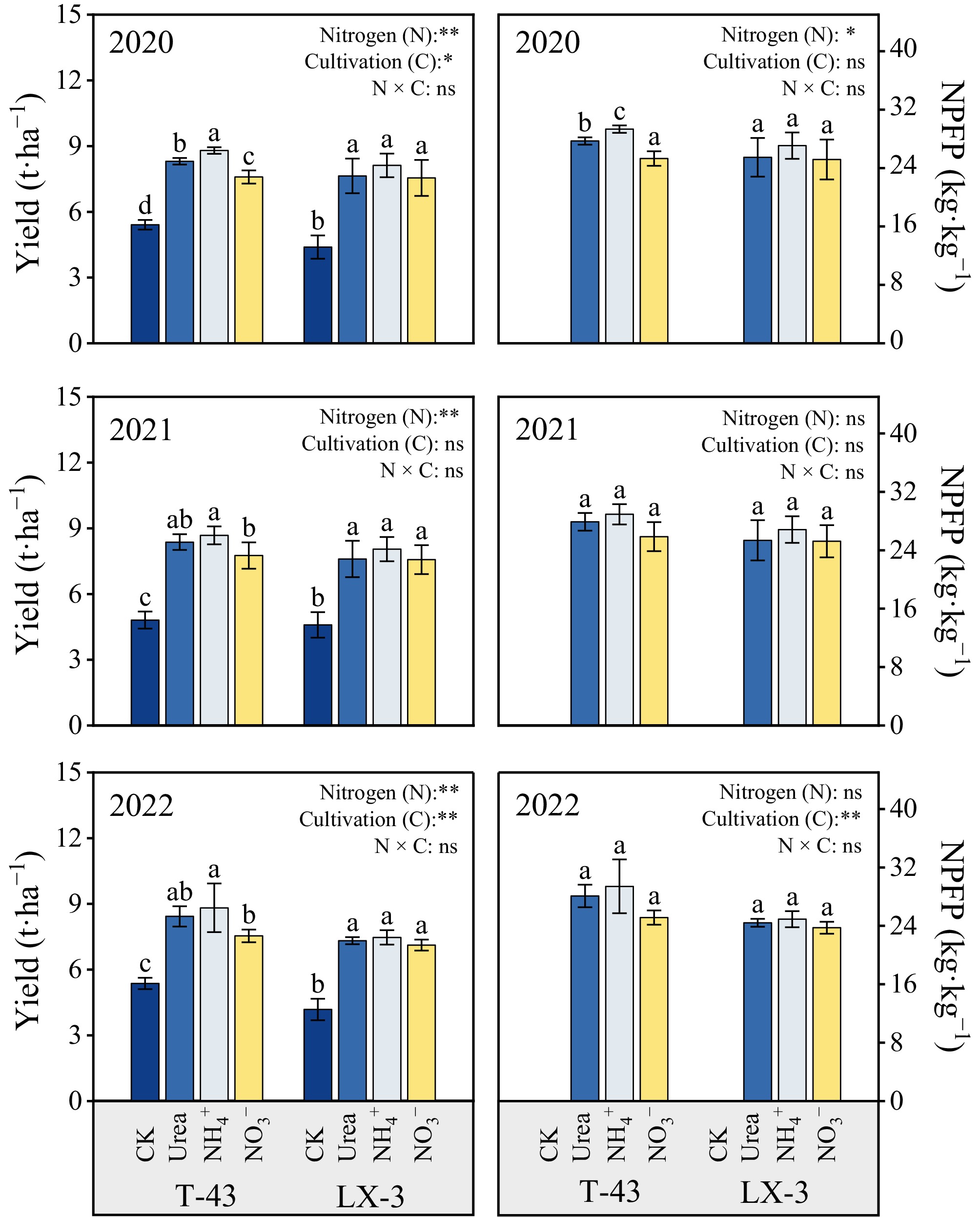

The response of yield to the different nitrogen forms (N) differed significantly (p < 0.05) between the two rice cultivars (C), and the trend was essentially consistent across years (Fig. 6). Compared with the CK treatment, N application significantly increased the yield of both cultivars (7.12–8.82 t·ha−1). The yield under the NH4+ treatment application was 2.04%–6.25% greater than that under the Urea and 4.95%–16.96% greater than that under the NO3−, and the NPFP was 4.74% and 10.63% greater than that under the Urea and NO3− treatments, respectively. Among the cultivars, the yield of T-43 was greater than that of LX-3 each year (0.53%–28.35%), and the NPFP was 8.54% greater than that of LX-3.

Figure 6.

Effects of N forms on the yield and NPFP of drip-irrigated rice. Different letters indicate that the values for the same cultivar are significantly different within the same year (p = 0.05). * and ** indicate significance at the p = 0.05 and 0.01 levels, respectively, and NS indicates nonsignificance at the p = 0.05 level.

Correlation analysis

-

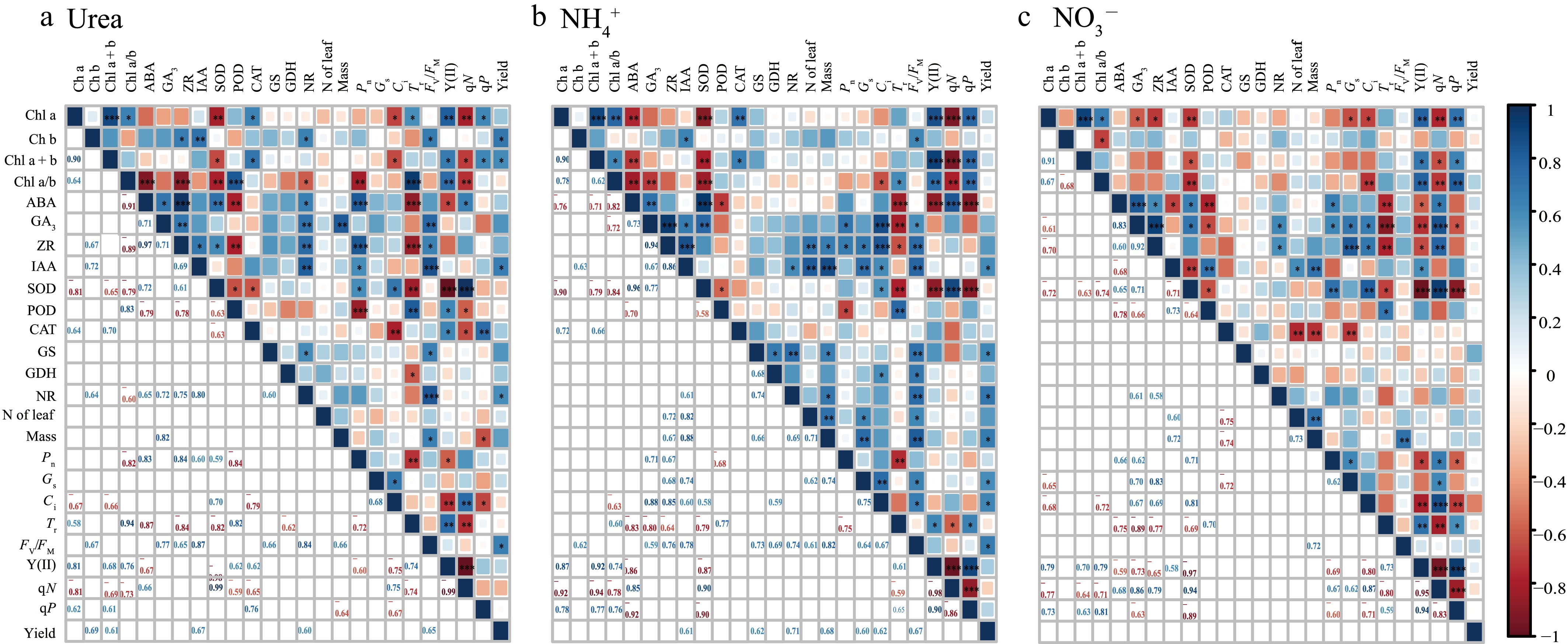

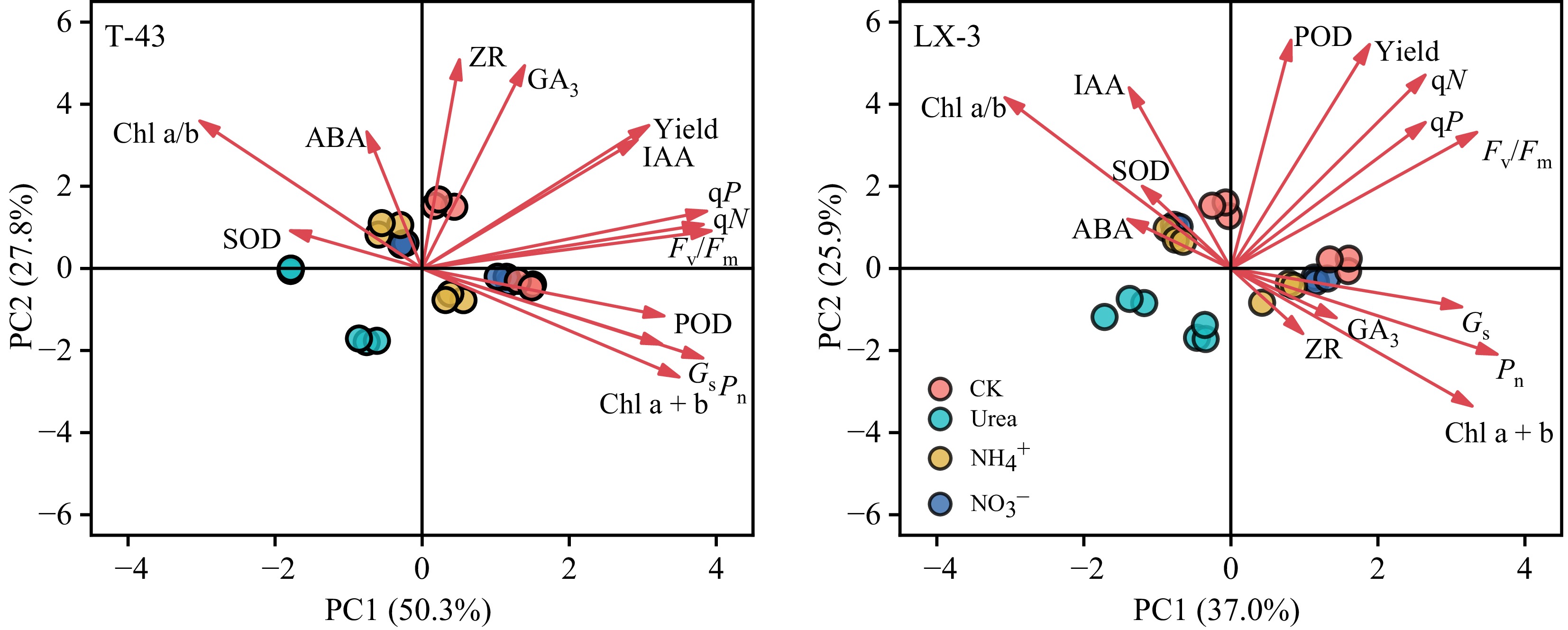

Correlation analysis revealed the effects of different N forms on plant photosynthesis, physiological characteristics, and yield (Fig. 7). Under the Urea, NH4+, and NO3− treatments, Chl a + b was significantly positively correlated with Y(II) and qP, whereas Fv/Fm was significantly positively correlated with Mass. Conversely, SOD was significantly negatively correlated with Chl a + b and POD, and ABA was significantly negatively correlated with POD, Tr, and Y(II). Further analysis revealed that under the Urea, Pn was significantly positively correlated with Chl a/b and IAA and significantly negatively correlated with Y(II); Mass was significantly positively correlated with GA3 and Chl a + b and significantly negatively correlated with qP. Under the NH4+, Ci was significantly positively correlated with IAA and Fv/Fm, and both Mass and Nleaf were significantly positively correlated with ZR and Gs. Under the NO3−, qN was significantly positively correlated with Pn, ZR, and Gs, but Pn was negatively correlated with qP, and Mass and Nleaf were both significantly negatively correlated with CAT. Additionally, under the NH4+, yield was significantly positively correlated with IAA, GS, NR, Pn, Gs, and Fv/Fm; under the Urea, yield was significantly positively correlated with Chl a + b, IAA, NR, and Fv/Fm, whereas under the NO3−, there was no significant correlation between the indicators and yield. PCA revealed that the first axis of T-43 explained 50.3% of the total variation (Fig. 8), with Fv/Fm, qN, and qP being indicators with high contributions, and the second axis explained 27.8% of the total variation, with ZR, GA3, and ABA being highly contributing indicators. The first axis of LX-3 explained 37.0% of the variation, with Fv/Fm, Gs, and Pn as highly contributing indicators; the second axis explained 25.9% of the variation, with POD, IAA, and qN being highly contributing indicators.

Figure 7.

Correlations between chlorophyll content, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, gas exchange parameters, antioxidant enzymes and hormones in different N forms. *, ** and *** indicate significance at the p = 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 levels, respectively.

Figure 8.

Principal component analysis of the photosynthetic physiology and leaf photosynthetic yield of different NUE cultivars of drip-irrigated rice cultivated with different N forms. PC1, principal component 1; PC2, principal component 2.

Partial least squares path model analysis

-

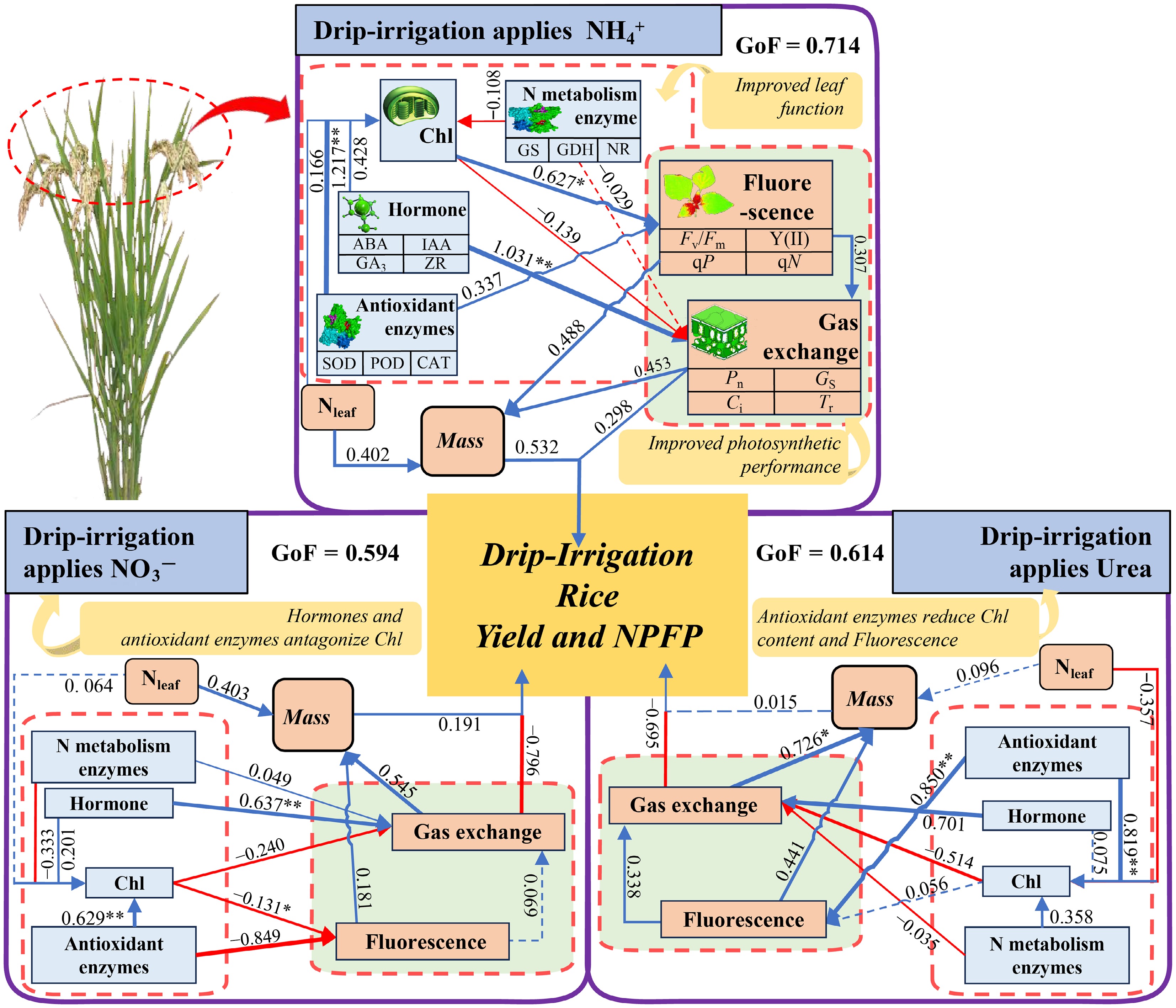

By constructing a partial least squares path model (PLS−PM), the pathways through which the photosynthetic and physiological characteristics of rice contribute to yield under different N forms were explored (Fig. 9). Under NH4+, the positive effects of leaf antioxidant enzymes on Chl (1.217**) indirectly promote plant chlorophyll fluorescence (0.627*), and the positive effects of hormones on gas exchange parameters (1.031**) further increase the leaf light quantum conversion efficiency. Concurrently, the positive effects of leaf N content, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, and gas exchange parameters on plant biomass increase the material accumulation ability of rice, ultimately contributing 0.714 to grain yield. Under NO3− conditions, although leaf hormones, antioxidant enzymes, and N metabolic enzyme activities all positively promote Chl, the negative inhibitory effects of Chl on gas exchange parameters (–0.240) and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (–0.131*) and the negative inhibitory effects of N metabolic enzymes on chlorophyll fluorescence parameters (–0.849) limit a plant's photosynthetic capacity, resulting in a contribution of 0.594 to grain yield. Under urea conditions, the positive effect of leaf N metabolic enzyme activity on chlorophyll fluorescence (0.850**) is counteracted by the inhibitory effect of leaf N content on chlorophyll content (–0.357), which negatively affects gas exchange parameters. Additionally, the negative effects of N metabolic enzyme activity on gas exchange parameters also limit a plant's photosynthetic capacity, ultimately leading to a contribution of 0.614 to grain yield.

Figure 9.

Partial least squares path model analysis (PLS−PM) of the photosynthetic physiology and yield of leaves in drip-irrigated rice under different N forms. Urea represents the CH4N2O treatment, NH4+ represents the (NH4)2SO4 treatment, and NO3− represents the Ca(NO3)2 treatment. The blue arrows represent facilitation, and the red arrows represent inhibition. GoF, goodness of fit. *, ** and *** indicate significance at the p = 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 levels, respectively.

-

The leaf serves as the primary organ for light interception and photosynthesis in crops[24]. Chlorophyll, the key light-harvesting component in chloroplasts, features Chl b, which captures low-radiance light under dim conditions to sustain essential photosynthesis, while the Chl a/b ratio reflects leaf senescence and stress responses[9,25]. In this study, both the T-43 and LX-3 cultivars presented relatively high Chl a and Chl b contents under the NH4+ treatment (Fig. 2), increasing light energy capture while minimizing photodamage to the photosynthetic apparatus. Conversely, the elevated Chl a/b ratios observed under the Urea and NO3− treatments reduced the photoprotective capacity of rice and impaired the photosynthetic system[9,26]. Furthermore, cultivar differences significantly influenced the chlorophyll content, with T-43 having consistently higher Chl a and Chl b levels than those in LX-3 (Fig. 2), indicating that high-NUE cultivars possess superior nitrogen assimilation capacity for chlorophyll biosynthesis and enhanced light energy utilization[27].

The absorption and translocation of different nitrogen forms by plants can influence their photosynthetic capacity. A study by Song et al.[28] revealed that the Pn of rice under ammonium nutrition was significantly greater than that under nitrate nutrition, and similar results were reported for cotton by Li et al.[29]. In the present study, the leaf Pn under the NH4+ nutrition was consistently greater than that in the Urea and NO3− treatments, indicating that NH4+ can increase the photosynthetic efficiency of rice during the grain-filling stage. Lyu et al.[10] attributed the differences in leaf photosynthetic rates among nitrogen forms to stomatal factors, whereas Guo et al.[30] reported that the reduction in Rubisco enzyme activity was the primary reason for the decreased photosynthetic rate under NO3− nutrition in hydroponic experiments. This study revealed that both Gs and Ci were greater in leaves under the NH4+ treatment than those under the NO3− treatment, suggesting that the increased stomatal conductance under NH4+ nutrition increases Ci, thereby increasing Rubisco carboxylation and CO2 assimilation capacity and ultimately improving photosynthetic efficiency[31]. Additionally, when leaf chlorophyll molecules absorb light energy and transition from the ground state to the excited state before returning to the ground state, they emit fluorescence[9]. Chlorophyll fluorescence serves as a probe for photosynthesis, and Guo et al.[32] proposed that nitrogen forms affect the Fv/Fm and Y(II). However, Zhou et al.[33] reported that nitrogen nutrition had no significant effect on chlorophyll fluorescence parameters in rice cultivation experiments. In this study, rice under NH4+ nutrition presented relatively high Fv/Fm, Y(II), and qP values (Fig. 4), indicating that drip-applied NH4+ enables the conversion of light energy into chemical energy in rice. The relatively high qN under the NH4+ further suggests that ammonium nutrition helps maintain the stability of photosynthetic structures and improves photochemical quantum efficiency. T-43 presented higher Pn, Gs, Y(II), and qN values than those in LX-3, implying that T-43 has superior light energy conversion and excess energy dissipation capabilities. Moreover, the stronger correlation between qN and both Chl a + b and Pn in T-43 (Fig. 7) further confirms that nitrogen-efficient varieties exhibit enhanced nonphotochemical quenching, increasing the chlorophyll content and maintaining photosynthetic apparatus stability[34].

Drip-applied ammonium nitrogen improves the stability of the internal leaf environment and prolongs leaf functionality

-

Following heading, grain filling is initiated while concurrent leaf senescence leads to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which disrupts cellular redox homeostasis, impairing photosynthetic function and ultimately reducing grain yield[35]. Nitrogen forms play crucial roles in maintaining leaf homeostasis by regulating hormone balance and antioxidant enzyme activity. For example, Singh et al.[36] reported that NO3− improves PSII activity, whereas Zeng et al.[18] reported that NH4+ enhances leaf structural stability through increased antioxidant enzyme activity in wheat. Krouk[20] further confirmed that NO3− increases the leaf ABA content. In this study, the SOD, POD, and CAT activity levels were significantly greater in NH4+-treated rice than those in NO3−-treated rice in the HS, with the enzyme activity in the low-NUE cultivar LX-3 greater than that in T-43. This increased antioxidant capacity alleviated oxidative stress, stabilized the leaf structure, and maintained superior photosynthetic performance. Notably, NH4+ nutrition resulted in relatively high GA3 and ZR levels but relatively low ABA contents, which contrasts with the findings of Walch-Liu et al.[37], who reported that of NH4+ suppressed cytokinins. This discrepancy may stem from rhizosphere acidification (pH reduction) caused by H+ release during NH4+ uptake under drip-irrigation, which potentially facilitates cytokinin diffusion[38]. The interplay between hormones and antioxidant enzymes critically regulates photosynthetic capacity. Our results revealed that NH4+ promoted ZR, IAA, and GA3 biosynthesis while inhibiting ABA production, collectively increasing Gs and improving quantum efficiency in drip-irrigated rice. Under NO3− nutrition, however, IAA was significantly negatively correlated with the Chl content and the Pn, ABA, and CAT activity. In particular, in the high-NUE cultivar T-43, IAA was positively correlated with Gs but negatively correlated with Chl a/b, whereas POD activity was negatively correlated with both Chl a + b and Gs. Conversely, LX-3 displayed the opposite trend. These findings suggest that the high-NUE cultivar, the low-NUE cultivar incurs greater metabolic costs than the high-NUE cultivar to sustain its antioxidant capacity, which compromises hormone biosynthesis and transport. This trade-off ultimately suppresses the chlorophyll content and stomatal conductance, thereby limiting the functional longevity of leaves[39].

As the central organ for both photosynthesis and nitrogen assimilation, leaf function depends on not only the redox capacity but also the coordinated regulation of nitrogen metabolism[40]. In this study, the GS, GDH, and NR activity levels under the NH4+ treatment were significantly greater than those under the NO3− and urea treatments at both the HS and 20 DAH. The effect of NH4+ on GDH activity was the most pronounced, which is likely attributable to the pivotal role of GDH in the direct assimilation of NH4+. Moreover, compared with those in LX-3, the nitrogen-metabolizing enzymes in T-43 were, on average, more active, with NR activity being 9.32% higher, indicating that the genotypic difference in nitrogen metabolism arises mainly from the efficiency of assimilation[41]. In terms of leaf nitrogen accumulation, the NH4+ treatment resulted in leaf N contents that were 11.08% and 10.02% greater than those in the urea and NO3− treatments, respectively, and this trend mirrored the changes in enzyme activity. This advantage can be linked to the rice nitrogen-response strategy: unlike NO3−, whose reduction by NR is energetically costly, NH4+ is rapidly converted to amino acids via the GS-GOGAT pathway, thereby reducing energy expenditure and providing ample nitrogen for chlorophyll synthesis[10,42]. Collectively, these results suggest that NH4+ not only supports the photosynthetic substrate supply by increasing nitrogen metabolism but also maintains cellular homeostasis—through the modulation of hormones and antioxidant enzymes—thus delaying leaf senescence and sustaining leaf functionality[9,14,18].

Coordinated regulation of leaf photosynthetic capacity and assimilate partitioning enhances yield in drip-irrigated rice

-

Different nitrogen forms (such as NH4+, NO3−, and Urea) regulate ionic homeostasis in plants through their distinct ionic properties, thereby influencing the photosynthetic balance and partitioning of assimilates between source and sink organs and ultimately determining yield[43,44]. Previous studies have reported crop-specific preferences for NO3− or NH4+ with respect to yield in wheat, rice, and other species[13,45]. In the present study, the NH4+ treatment increased dry matter accumulation in both the source (leaves) and sink (panicles) at both the HS and 20 DAH, and the panicle-to-total dry mass ratio was also greater than that under the NO3− or Urea. These findings indicate that drip-applied ammonium nitrogen not only increases the overall source–sink capacity of drip-irrigated rice but also promotes the allocation of photoassimilates to panicles, thereby strengthening the competitive ability of the sink[46]. The high-NUE cultivar T-43 presented high contents of phytohormones and chlorophyll; high Fv/Fm, Y(II) and qP; and elevated activities of nitrogen-metabolizing enzymes, all of which further increased dry matter accumulation and yield formation. In contrast, the relatively high ABA content in LX-3, together with its significant negative correlations with Chl a + b, qN, and Gs, constrained the photosynthetic capacity and impaired source–sink coordination.

Partial least squares path analysis (Fig. 9) further revealed that under NH4+ nutrition, the activity of antioxidant enzymes in rice leaves increased the Chl content (1.217), which in turn indirectly increased the Chl fluorescence (0.627*). Moreover, endogenous hormones positively regulate gas exchange parameters (1.031), ultimately driving biomass formation. In contrast, under urea and NO3−, the leaf N content had a suppressive effect on the Chl content, and chlorophyll itself negatively influenced gas exchange variables, resulting in reduced light-use efficiency. These contrasting responses are attributable to the distinct physiological consequences of each N form. When rice takes up NO3−, OH− is released, increasing the rhizosphere pH and inducing iron plaque formation on the root surface[47]. Conversely, NH4+ uptake occurs via the glutamine–arginine pathway, releasing H+ and decreasing the rhizosphere pH value[14,16,38]. In the alkaline soil used in this study, the decrease in pH induced by NH4+ was beneficial for rice growth, and the applied nitrification inhibitor further suppressed nitrification, thereby increasing NH4+ acquisition and utilization[48]. Consequently, the contribution of photosynthetic traits to grain yield under NH4+ (GoF = 0.714) exceeded that under NO3− (GoF = 0.594) and Urea (GoF = 0.614).

These results demonstrate that, compared with NO3− and Urea, NH4+ nutrition provides pronounced advantages: (1) it results in increased chlorophyll content, photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm), and elevated qN, and thereby enhances overall photosynthetic performance; (2) it strengthens the leaf antioxidant capacity and rebalances phytohormones—decreasing ABA and increasing stomatal conductance—while preserving the integrity of photosynthetic structures; and (3) it increases nitrogen-metabolizing enzyme activity levels and leaf N contents, increasing biomass accumulation and partitioning in both sources (leaves) and sinks (panicles) and ultimately increasing grain yield and nitrogen use efficiency. Nevertheless, yield formation is also shaped by canopy light distribution and the vertical allocation of photosynthetic nitrogen within leaves[49,50]. Future studies should therefore investigate how different NH4+/NO3− ratios modulate canopy architecture and light interception/utilization in drip-irrigated rice—a promising avenue for further insights.

-

Under drip-irrigation conditions, ammonium nitrogen (NH4+) increases leaf chlorophyll content and nitrogen metabolism enzyme activity levels while reducing abscisic acid (ABA) levels, thereby improving leaf stomatal conductance and light quantum conversion efficiency, which promotes biomass accumulation and partitioning. The PLS‒PM results further confirmed that the contribution of photosynthetic and physiological traits to yield under the NH4+ treatment (GoF = 0.714) was greater than that under the Urea (GoF = 0.614) and NO3− (GoF = 0.594) treatments. Compared with the low nitrogen use efficiency cultivar LX-3, the high nitrogen use efficiency cultivar T-43, which is characterized by high levels of IAA, GA3, and ZR, effectively maintained high Chl a + b contents and increased stomatal conductance, thereby increasing its photosynthetic capacity and ultimately increasing yield by 0.53%–28.35%. In summary, under drip-irrigation with ammonium nitrogen fertilizer, the hormonal balance in the high nitrogen use efficiency cultivar (T-43) is synergistically regulated, which in turn increases enzyme activity and stomatal conductance related to leaf nitrogen metabolism, maintains a relatively high chlorophyll content, improves light quantum efficiency, and consequently further increases the yield of drip-irrigated rice.

We are very grateful for the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32360527, 31460541).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Song Z, Li Y, Wang G; data collection: Song Z, Tang Q; Zhao L; analysis and interpretation of results: Song Z, Tang Q; draft manuscript preparation: Song Z, Li Y, Wang G. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Zhiwen Song, Qingyun Tang

- Supplementary Table S1 Nitrogen and irrigation application rates for drip-irrigation rice.

- Supplementary Table S2 Effects of N form on N-metabolizing enzyme activity in drip-irrigated rice leaves.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Effects of N forms on N metabolizing enzymes in drip-irrigated rice. SOD, superoxide dismutase; POD, peroxidase; CAT and catalase. Different letters indicate that the values for the same cultivar are significantly different within the same year (p = 0.05).

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Effects of N form on the N content in rice leaves. HS, heading stage; 20 DAH, 20 days after heading. Different letters indicate that the values for the same cultivar are significantly different within the same year (p = 0.05).

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Song Z, Tang Q, Zhao L, Wang G, Li Y. 2026. Ammonium nutrition improves the yield of drip-irrigated rice by prolonging leaf photosynthetic capacity and enhancing source‒sink performance. Technology in Agronomy 6: e004 doi: 10.48130/tia-0025-0017

Ammonium nutrition improves the yield of drip-irrigated rice by prolonging leaf photosynthetic capacity and enhancing source‒sink performance

- Received: 21 August 2025

- Revised: 17 October 2025

- Accepted: 14 November 2025

- Published online: 13 February 2026

Abstract: The effects of the application of different nitrogen (N) forms via drip-irrigation on the physiological photosynthetic characteristics of rice and their contributions to yield remain incompletely understood. To address this knowledge gap, a field drip-irrigation experiment was conducted from 2020 to 2022 using a high-NUE cultivar (T-43) and a low-NUE cultivar (LX-3). Using a no-nitrogen treatment (CK) as the control, the effects of three nitrogen fertilizer treatments—urea (Urea), ammonium (NH4+), and nitrate (NO3−)—were compared. The main results are as follows. (1) The application of nitrogen significantly increased the biomass (26.74%–30.71%) and yield (40.35%–84.91%). Compared with Urea and NO3−, NH4+ increased the chlorophyll content (Chl) and N metabolic enzyme activity, decreased the abscisic acid (ABA) content, and improved stomatal conductance (Gs). (2) T-43 presented relatively high levels of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), Chl a + b, and Gs, and a relatively high photosynthetic rate (Pn), whereas LX-3 presented increased ABA levels and reduced Chl a + b, and Gs. (3) Partial least squares path model revealed that under NH4+, IAA was positively correlated with Chl b, Gs, and Fv/Fm, whereas ABA was negatively correlated with Y(II), and Chl a + b. Conversely, the Chl contents decreased, and the ABA and Chl a/b increased in the Urea and NO3− treatments, thereby increasing the contribution of NH4+ (GoF = 0.714) to yield when compared to the yields in the Urea (0.614) and NO3− (0.594). In summary, NH4+ synergistically enhances Chl content, photochemical efficiency, antioxidant capacity, and regulates hormone balance while increasing source–sink dry matter accumulation and distribution, thereby achieving efficient production of drip-irrigated rice in arid areas.

-

Key words:

- Drip-irrigated rice /

- Nitrogen forms /

- Photosynthetic physiology /

- Yield