-

In nature, light plays a crucial role in the growth and development of plants. A large number of studies have shown that light quality has a significant regulatory effect on seed germination, morphogenesis, physiological and biochemical characteristics, yield, and quality of plants[1−3]. With the continuous in-depth research in photobiology, the regulatory mechanisms of light quality on plant growth and development have gradually been revealed, becoming a key focus in plant science research.

Light quality is an important factor affecting plant growth and development[4]. Previous studies have demonstrated that specific light wavelengths can regulate key physiological processes, including seed germination, flowering, hormone signaling, and stress responses[5−7]. For instance, studies have shown that red light (R light) can influence chlorophyll content and photosynthetic function, regulate cell turgor and growth, and promote hypocotyl elongation via phytochromes in plants[8]. Red light-emitting diodes (LEDs) have been used to stimulate stem elongation in Phalaenopsis and lettuce[9,10]. Blue light can be absorbed by cryptochromes[11], which regulate bud growth and stomatal opening and closing. This, in turn, affects photomorphogenesis and photosynthesis[11]. Blue light has been shown to regulate the biosynthesis of anthocyanins, betaine, and total phenolic compounds, with documented effects in diverse plant systems including Amaranthus species, Lactuca sativa, and multiple moss genera[12]. However, exposure to only red or blue light cannot guarantee the normal growth of plants[13], while combining red and blue light is more conducive to plant growth than monochromatic light[14,15]. Research has found that the combination of R/B light can effectively enhance the photosynthetic rate in tomatoes, increase the accumulation of sucrose, fructose, glucose, and starch, and promote the synthesis of chlorophyll and carotenoids[16,17]. Currently, the primary or supplemental light sources commonly used in horticulture are LEDs. These have many advantages, including low heat generation, small size, low energy consumption, and a long service life. It is also easy to adjust the light intensity of an LED. Furthermore, many LEDs have an advanced wavelength adjustment configuration, which can be used to more conveniently optimize the growth processes of plants[18]. Recently, researchers have successfully used LED light sources to conduct research on chrysanthemums, tomatoes, and other crops[19,20].

Variable light conditions can induce stress in plants, leading to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). As key regulatory factors in plant metabolism and stress responses, ROS play important roles in regulating cell wall development and activating antimicrobial defense signaling molecules[21]. However, being toxic by-products of aerobic metabolism, ROS can also cause damage to plant cells and their photosynthetic systems. This damage manifests as oxidative damage to DNA, RNA, proteins, and cell membranes[22]. ROS primarily originate from the electron transport chains in photosystem I (PSI), photosystem II (PSII), and photorespiration[23]. These processes can affect the stability of chlorophyll, thereby reducing the activity of photosynthesis. To mitigate this damage, plants have evolved a mechanism over time to clear ROS using antioxidant enzymes (such as superoxide dismutase [SOD], catalase [CAT], peroxidase [POD], and ascorbate peroxidase [APX])[24]. This is the main way plants perform photoprotection[25].

Philodendron 'con-go' is a common indoor ornamental plant in the Araceae family. Currently, most studies on Philodendron 'con-go' have focused on tissue culture and morphogenesis, and there have been relatively few studies on how light quality affects this species[26,27]. This study aims to identify the optimal red-to-blue light ratio for enhancing commercial seedling quality and indoor acclimatization of Philodendron 'con-go', establish a theoretical basis and technical protocols for standardized production. Through comprehensive evaluation of R:B light effects on biomass accumulation, chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, gas exchange characteristics, and antioxidant defense systems, along with systematic analysis of dynamic physiological response patterns, this study elucidates the regulatory mechanisms underlying light-quality adaptation. The findings are expected to optimize photoassimilate partitioning efficiency and ROS-scavenging capacity in Philodendron 'con-go', thereby improving its structural traits and environmental resilience under indoor conditions. Ultimately, this investigation will provide evidence-based spectral management strategies to refine the species' propagation protocols and advance its cultivation as a premium indoor foliage plant.

-

The experimental material was the Philodendron 'con-go', using tissue-cultured domesticated seedlings as the transplanting material. These seedlings are 2 cm tall with three true leaves. The seedlings were two months old at the time of transplantation, and uniform transplanted and domesticated seedlings with consistent growth conditions and specifications were selected for further experimentation.

A 1:1 perlite:vermiculite mix was used as substrate. The containers were placed in an LED-illuminated culture rack, and each treatment consisted of 20 seedlings. The experiments were performed in triplicate, meaning there were a total of 60 seedlings. Each plant was irrigated with 100−150 mL of nutrient solution per application. The plantlets were fertigated every 3 d with a nutrient solution containing the following concentrations: N 243.9 mg·L−1, P 41.8 mg·L–1, K 312.8 mg·L–1, Ca 161.0 mg·L–1. Five different red-blue light quality ratios were set up, including 100% red light (R), 80% R + 20% blue light (B), 70% R + 30% B, 60% R + 40% B, and 100% B. Ordinary fluorescent light sources were used as a control (CK), with red (640 nm) and blue (646 nm) LEDs as light sources. The temperature was maintained at 24 °C, with a light intensity of 1,500 lux and a photoperiod of 12 h per day. The experimental duration spanned 60 d, commencing on 10th May 2024 and concluding on 9th July 2024, and the spectral composition was consistent with that reported in the study by Song et al.[28]. LED lamp belts were designed and custom-made by the research team, and tailored by Xiamen Hualian Electronics Co., Ltd, Xiamen, China.

Growth parameters

-

Plant height, leaf number, leaf length, leaf width, root number, maximum root length, fresh weight, and dry weight were all measured. When determining dry weight, plant samples were dehydrated in a constant-temperature oven at 105 °C for 30 min, followed by constant-temperature drying at 60 °C for 48 h. The aboveground, underground, and total dry matter rates (Dry matter rate = dry weight / fresh weight × 100%) were also calculated[29].

Chlorophyll and carotene content

-

The chlorophyll content was determined using a mixture of absolute ethanol and acetone extraction[30]. Briefly, 0.2 g of chopped leaves were placed in a 1:1 mixture of 80% acetone (acetone : water = 80%:20%) and absolute ethanol and incubated for 24 h in the dark. Absorbance (OD) was measured using a UV spectrophotometer at 663, 645, and 470 nm, with 80% acetone as a blank control. The chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoid contents of the plants were calculated based on these results.

Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters

-

Chlorophyll fluorescence was measured using a MIMI-PAM portable modulated fluorometer produced by the WALZ company in Germany. The light quality and intensity should be set according to the equipment user manual. Measurements were conducted from 11:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. on day 60. The third fully expanded leaf from each plant was selected for use in the assay. Before the assay, each tested leaf was clamped and acclimatized to dark conditions for 30 min. The initial fluorescence (Fo), maximum fluorescence (Fm), fluorescence yield (Ft), maximum fluorescence under light (Fm′), and minimum fluorescence under light (Fo′) were measured.

The maximum photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm), actual photochemical efficiency (ФPSII), photochemical quenching coefficient (qP), and non-photochemical quenching coefficient (NPQ) were calculated based on the method of Wu et al.[31].

Leaf photosynthetic parameters

-

The net photosynthetic rate (Pn), transpiration rate (E), stomatal conductance (gs), and intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) were measured using the LI-6400XT portable photosynthesis measuring instrument produced by LI-COR in the United States. All of these values were determined using the third fully expanded leaf between 8:00 a.m. and 11:00 a.m. The atmospheric pressure was 102 kPa, the leaf temperature was (25 ± 1) °C, and the external CO2 concentration was 450 μmol·mol–1.

Root activity

-

Root activity was determined using the triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) reduction method of Ryssov-Nielson & Trevors[32,33]. The cleaned roots were immersed in TTC solution and phosphate buffer, and the reaction was terminated using 1 mol·L–1 sulfuric acid solution after incubation at 37 °C for 1 h. After elution with ethyl acetate, the absorbance at 485 nm was measured using a UV spectrophotometer. Root activity was calculated based on these results.

Soluble sugar content

-

Soluble sugar content was measured using the method of Clegg et al.[34]. The specific method is as follows: briefly dehydrate the samples at 105 °C for 30 min, followed by constant-temperature drying at 60 °C for 48 h. Subsequently, take 1 g of the leaf sample for grinding. Then, add distilled water, and boil the mixture for 10 min. After filtering, a 100 mL sample was collected for further use. Half a milliliter of anthone-ethyl acetate reagent was added to 1 mL of the sample, followed by 5 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid. The resulting solution was boiled for 5 min, and then its absorbance at 630 nm was measured.

Antioxidant enzyme activity and soluble protein content

-

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was determined using a method based on the photochemical reduction of nitrotetrazolium blue chloride (NBT)[35]. The leaves were ground and added to a 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) containing 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP). This mixture was then centrifuged at 4 °C at 12,000 rpm, and the supernatant was collected for enzyme extraction. To 0.05 mL of enzyme extract was added 1.5 mL of phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.8), 0.3 mL of Met solution (130 mM), 0.3 mL of NBT solution (0.75 mM), 0.3 mL of EDTA solution (0.1 mM), 0.3 mL of riboflavin solution (0.02 mM), and 0.25 mL of distilled water. Two controls, one for light and one for dark conditions, were also prepared. Finally, the OD at 560 nm was measured using a UV spectrophotometer. The soluble protein content was determined using the Coomassie Brilliant Blue (G250) method[36]. Briefly, 1 mL of enzyme extract was collected, to which 5 mL of Coomassie Brilliant Blue solution was added. The mixture was shaken well, and after being allowed to stand for 2 min, its absorbance at 595 nm was measured to determine its soluble protein content.

Statistical analysis

-

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed with SPSS 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States), and significant differences between means were determined by Duncan's multiple range test (DMRT) at p ≤ 0.05.

-

As shown in Table 1, when the Philodendron 'con-go' cultivar was grown under hydroponic conditions and under the previously described light quality conditions, plant height was found to be the highest under the 6:4 light treatment. However, there was no significant difference in plant height between the plants in the 6:4 and 7:3 treatments. The next tallest group of plants was that grown under the 8:2 light conditions, followed by those in the B and R treatments. The plants in the control group (CK) were the shortest. The maximum number of leaves also appeared in the plants in the 6:4 light treatment group. However, no significant difference in leaf number was observed between the 6:4 group and other treatments. The plants in the CK group had the smallest number of leaves. The maximum leaf length was observed in the 6:4 treatment, followed by the 7:3 treatment. In contrast, the B treatment yielded significantly shorter leaves than the other two treatments. No significant differences in leaf width were detected among treatments.

Table 1. The growth status of Philodendron 'con-go' under different light qualities.

Different treatments Plant height (cm) No. of leaves (piece) Leaf length (cm) Leaf width (cm) No. of roots (strip) Root length (cm) Fresh weight (g) Dry weight (g) Ground Ground floor Ground Ground floor CK 9.78 ± 0.17 c 7.40 ± 0.68 b 4.62 ± 0.21 bc 2.02 ± 0.05 a 12.20 ± 0.97 b 7.34 ± 0.68 a 2.03 ± 0.08 b 0.51 ± 0.08 b 0.14 ± 0.014 b 0.06 ± 0.006 b R 10.41 ± 0.36 bc 9.00 ± 1.05 ab 4.24 ± 0.09 c 2.01 ± 0.09 a 14.20 ± 1.24 ab 9.57 ± 0.89 a 2.11 ± 0.12 b 0.58 ± 0.08 b 0.13 ± 0.004 b 0.05 ± 0.002 b B 10.44 ± 0.22 bc 9.40 ± 0.81 ab 4.62 ± 0.08 bc 2.18 ± 0.11 a 14.20 ± 1.28 ab 7.78 ± 0.33 a 2.26 ± 0.20 b 0.54 ± 0.04 b 0.15 ± 0.011 b 0.06 ± 0.006 b 6:4 11.94 ± 0.65 a 11.20 ± 1.68 a 5.20 ± 0.19 a 2.22 ± 0.04 a 14.40 ± 1.36 ab 7.91 ± 0.66 a 3.39 ± 0.15 a 0.55 ± 0.08 b 0.25 ± 0.019 a 0.06 ± 0.01 b 7:3 11.02 ± 0.93 ab 9.80 ± 0.86 ab 4.96 ± 0.23 ab 2.22 ± 0.02 a 16.20 ± 1.07 a 9.68 ± 1.11 a 2.27 ± 0.12 b 0.97 ± 0.08 ab 0.16 ± 0.011 b 0.08 ± 0.006 a 8:2 10.60 ± 0.30 bc 10.40 ± 0.87 ab 4.68 ± 0.22 abc 2.04 ± 0.08 a 15.40 ± 10.3 ab 9.16 ± 1.01 a 2.28 ± 0.21 b 1.20 ± 0.03 a 0.17 ± 0.015 b 0.09 ± 0.009 a Blue (B), Red (R), 60% Red + 40% Blue (6:4), 70% Red + 30% Blue (7:3), 80% Red + 20% Blue (8:2). The statistical analysis has been carried out separately for each cultivar. Different letters indicate significant differences using Duncan's multiple range test (p ≤ 0.05; n = 10). In terms of roots, the plants in the 7:3 treatment had the highest number of roots and the longest root length, with the number of roots significantly exceeding that of the plants in the CK group. For shoot biomass, the 6:4 treatment showed the maximum fresh weight, which was significantly higher than that in all other treatments. The maximum fresh weight for the underground plant parts was found in the 8:2 treatment group, followed by the 7:3 and 6:4 treatments. The maximum dry weight for the aboveground plant parts was found in the 6:4 treatment, and the dry weight of the underground part was highest in the 8:2 treatment. The second-highest dry weight of the underground part occurred in the 7:3 treatment, which was significantly higher than that in other treatments.

In conclusion, the 6:4 light quality treatment had a significant effect on the growth performance of Philodendron 'con-go', especially for plant height, leaf number, leaf length, and aboveground fresh weight. In terms of the root system and underground dry weight, the plants in the 7:3 and 8:2 treatments performed best.

Effect on chlorophyll content in leaves of Philodendron 'con-go'

-

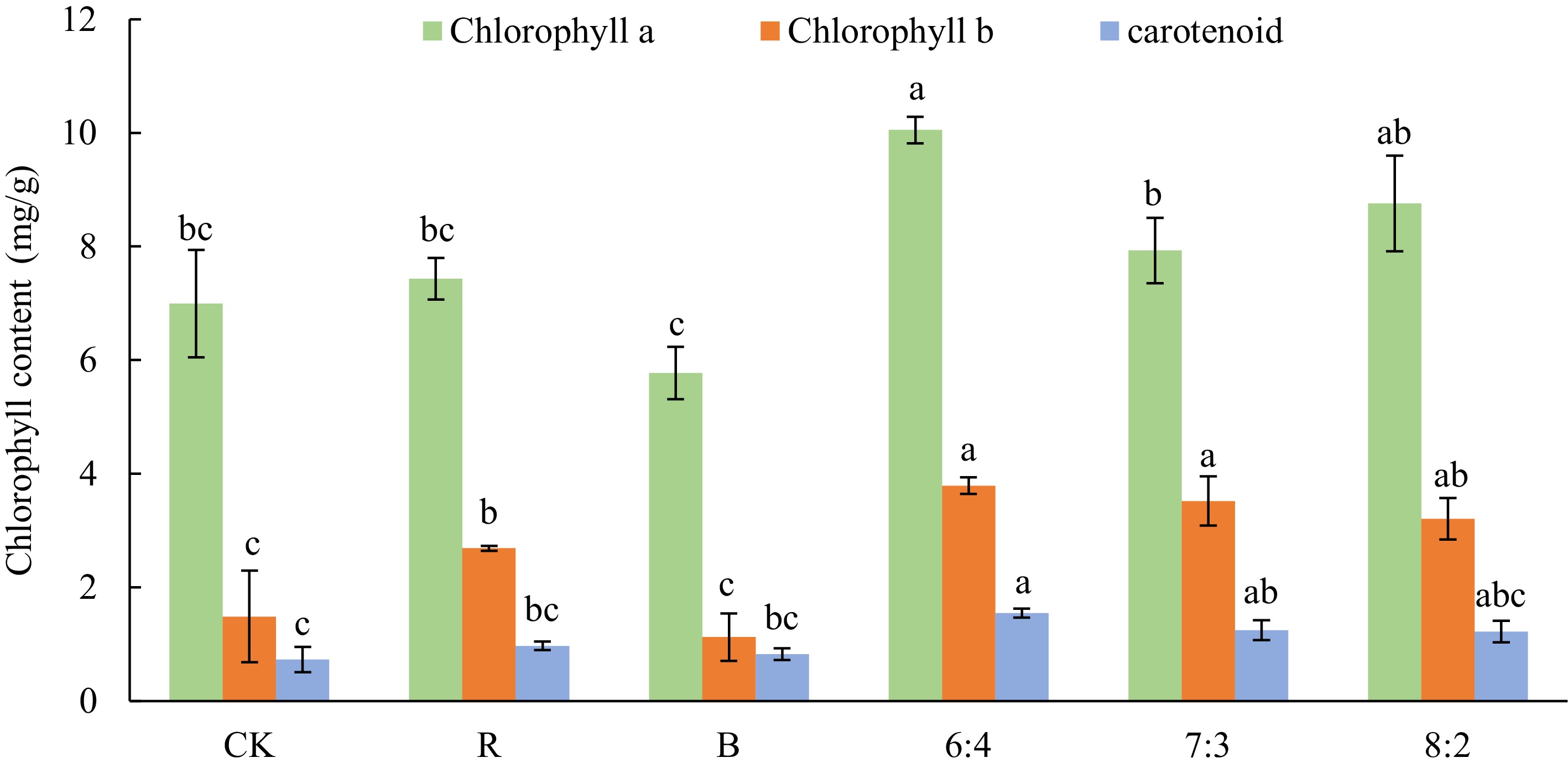

The chlorophyll content of the Philodendron 'con-go' cultivar under different light treatments is shown in Fig. 1. The contents of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoids under combined red and blue light treatments were generally higher than those under monochromatic light treatments. These components reached their highest levels under the 6:4 treatment, with values 43.79%, 154.76%, and 112.28% higher than the CK treatment, respectively.

Figure 1.

Effects of different light qualities on leaf chlorophyll content of Philodendron 'con-go'. Blue (B), Red (R), 60% Red + 40% Blue (6:4), 70% Red + 30% Blue (7:3), 80% Red + 20% Blue (8:2). Vertical bars indicate standard error (n = 5). Different letters represent a significant difference at p ≤ 0.05 among treatments by Duncan's multiple range test.

Effect on fluorescence parameters of Philodendron 'con-go' leaves

-

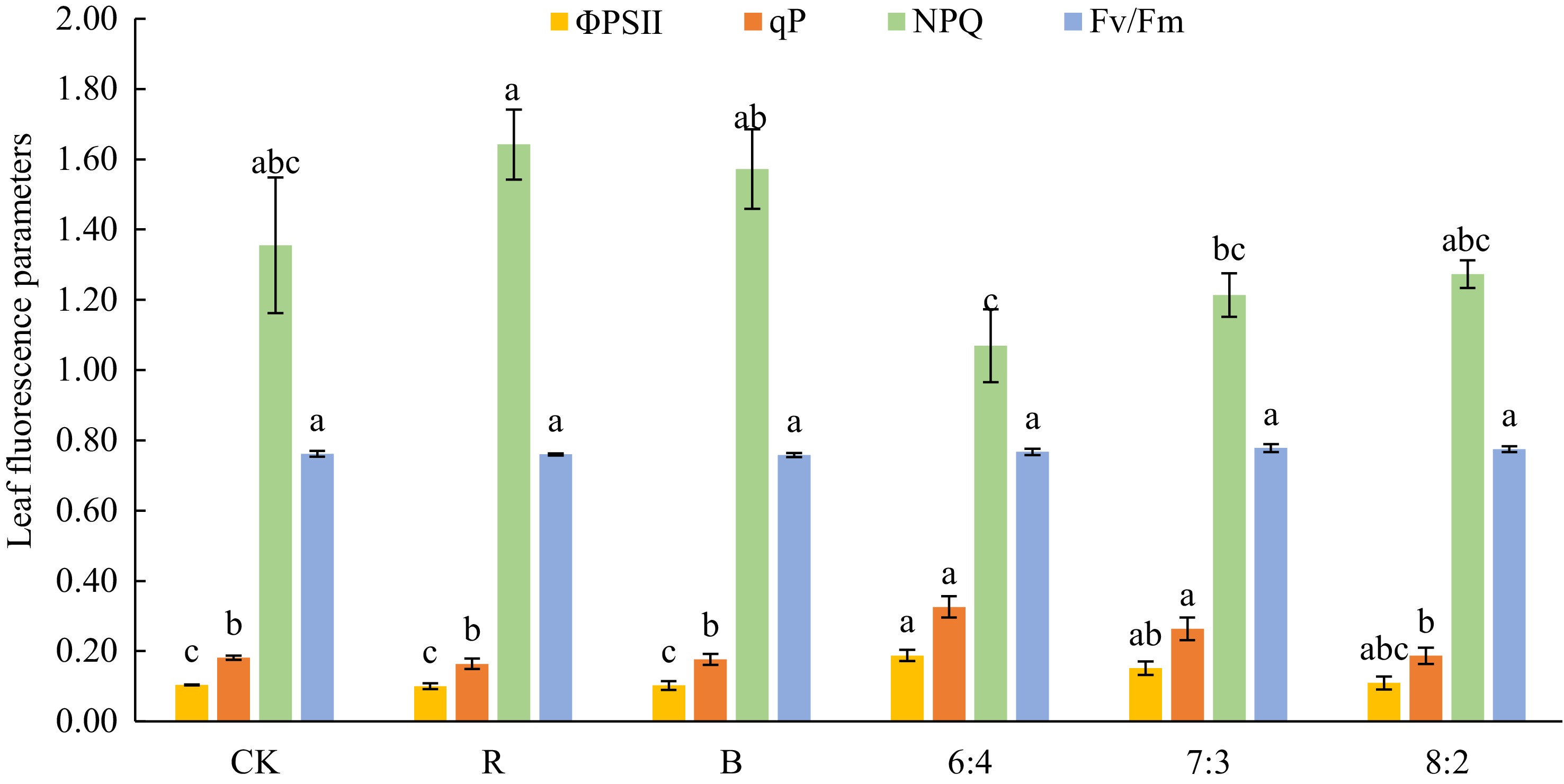

The fluorescence measurements of the leaves of Philodendron 'con-go' plants under different light quality treatments are shown in Fig. 2. The 6:4 treatment exhibited the highest actual photochemical efficiency (ΦPSII) and photochemical quenching coefficient (qP), which were 72.73% and 83.33% higher than those in the CK treatment, respectively. In contrast, the non-photochemical quenching coefficient (NPQ) was 21.33% lower than CK. However, the maximum photochemical efficiency (Fv/Fm) reached its peak value in the 7:3 treatment group. Plants under monochromatic light (B and R treatments) performed poorly in most photosynthetic parameters. The 6:4 and 7:3 treatments most significantly enhanced photosynthesis and were optimal for light quality optimization in hydroponic LED systems.

Figure 2.

Effects of different light qualities on chlorophyll fluorescence measurements in Philodendron 'con-go'. Blue (B), Red (R), 60% Red + 40% Blue (6:4), 70% Red + 30% Blue (7:3), 80% Red + 20% Blue (8:2). Vertical bars indicate standard error (n = 5). Different letters represent significant differences ( p ≤ 0.05) among treatments as determined using Duncan's multiple range test.

Effect on photosynthetic parameters of Philodendron 'con-go' leaves

-

According to the data in Table 2. The Pn was the highest in the plants in the 7:3 treatment group, followed by those in the 6:4 group. However, the difference between the two groups was not obvious. The plants in the CK and R treatments had even lower photosynthetic rates. The E value was the highest in the plants in the 6:4, and it was significantly higher than that in any other treatment except for the 7:3. The plants in the CK treatment had the smallest value for this parameter. The gs value was the highest in the plants in the 6:4, and it was significantly higher in this treatment than in the others. The next highest gs values were found in the plants in the 7:3 and 8:2. The gs values in the plants in the B, CK, and R treatments decreased in turn, but the difference was not significant. The Ci values were the highest in the plants in the 7:3. The values for the plants in this group were significantly higher than those of the plants in the other treatments. The next highest Ci values were found in the plants in the 8:2, 6:4, and B, and the Ci value was the smallest in the CK.

Table 2. Effects of different light qualities on photosynthetic parameters of Philodendron 'con-go'.

Dispose Pn

(µmol·m−2·s−1)E

(mmol·m−2·s−1)gs

(µmol·m−2·s−1)Ci

(µmol·mol−1)CK 0.34 ± 0.05 b 0.10 ± 0.003 d 3.14 ± 0.16 c 175.69 ± 9.47 d R 0.33 ± 0.02 b 0.11 ± 0.004 cd 3.12 ± 0.15 c 189.62 ± 15.78 cd B 0.37 ± 0.04 ab 0.11 ± 0.003 d 3.28 ± 0.45 c 204.67 ± 14.15 bcd 6:4 0.45 ± 0.03 a 0.14 ± 0.003 a 4.55 ± 0.11 a 223.16 ± 14.09 bc 7:3 0.47 ± 0.04 a 0.13 ± 0.005 ab 4.03 ± 0.10 b 301.78 ± 17.73 a 8:2 0.39 ± 0.04 ab 0.12 ± 0.008 bc 3.98 ± 0.22 b 246.41 ± 13.21 b Blue (B), Red (R), 60% Red + 40% Blue (6:4), 70% Red + 30% Blue (7:3), 80% Red + 20% Blue (8:2). The statistical analysis has been carried out separately for each cultivar. Different letters indicate significant differences using the Duncan's multiple range test (p ≤ 0.05; n = 10). The transpiration rate was the highest in the plants in the 6:4, which was significantly higher than that in the plants in the other treatments, except for the 7:3. The plants in the CK group had the lowest transpiration rates. The gs value was the highest in the plants in the 6:4, and it was significantly higher in these plants than in those in the other treatments. The next highest E values were found in the plants in the 7:3 and 8:2. The E values in the plants in the B, CK, and R treatments decreased in turn, but the difference was not significant. The Ci value was the highest in the plants in the 7:3 treatment, and it was significantly higher than that in the plants in the other treatments. The next highest Ci values were found in the plants in the 8:2, 6:4, and B treatments, and the lowest Ci value was found in the CK.

Effect on root activity of Philodendron 'con-go'

-

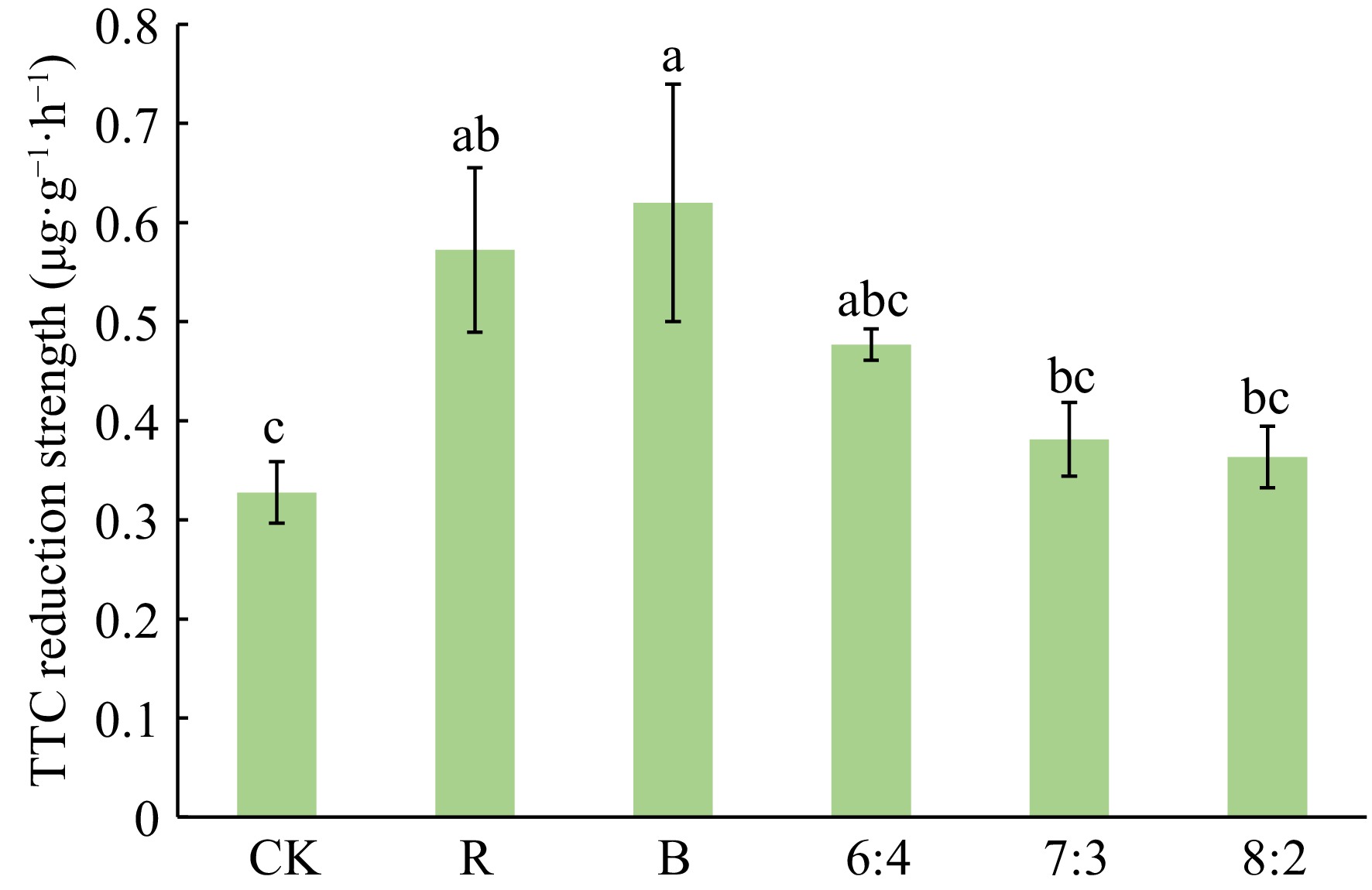

As can be seen from Fig. 3, under the B treatment, Philodendron 'con-go' exhibited the highest root activity, which was significantly greater than that in the CK group. The R and 6:4 treatments showed intermediate root activity levels, slightly lower than B but still higher than CK. No significant differences were observed among the 7:3, 8:2, and CK treatments.

Figure 3.

Effects of different light qualities on root activity of Philodendron 'con-go'. Blue (B), Red (R), 60% Red + 40% Blue (6:4), 70% Red + 30% Blue (7:3), 80% Red + 20% Blue (8:2). Vertical bars indicate standard error (n = 5). Different letters represent a significant difference at p ≤ 0.05 among treatments by Duncan's multiple range test.

Effect on soluble sugars in Philodendron 'con-go'

-

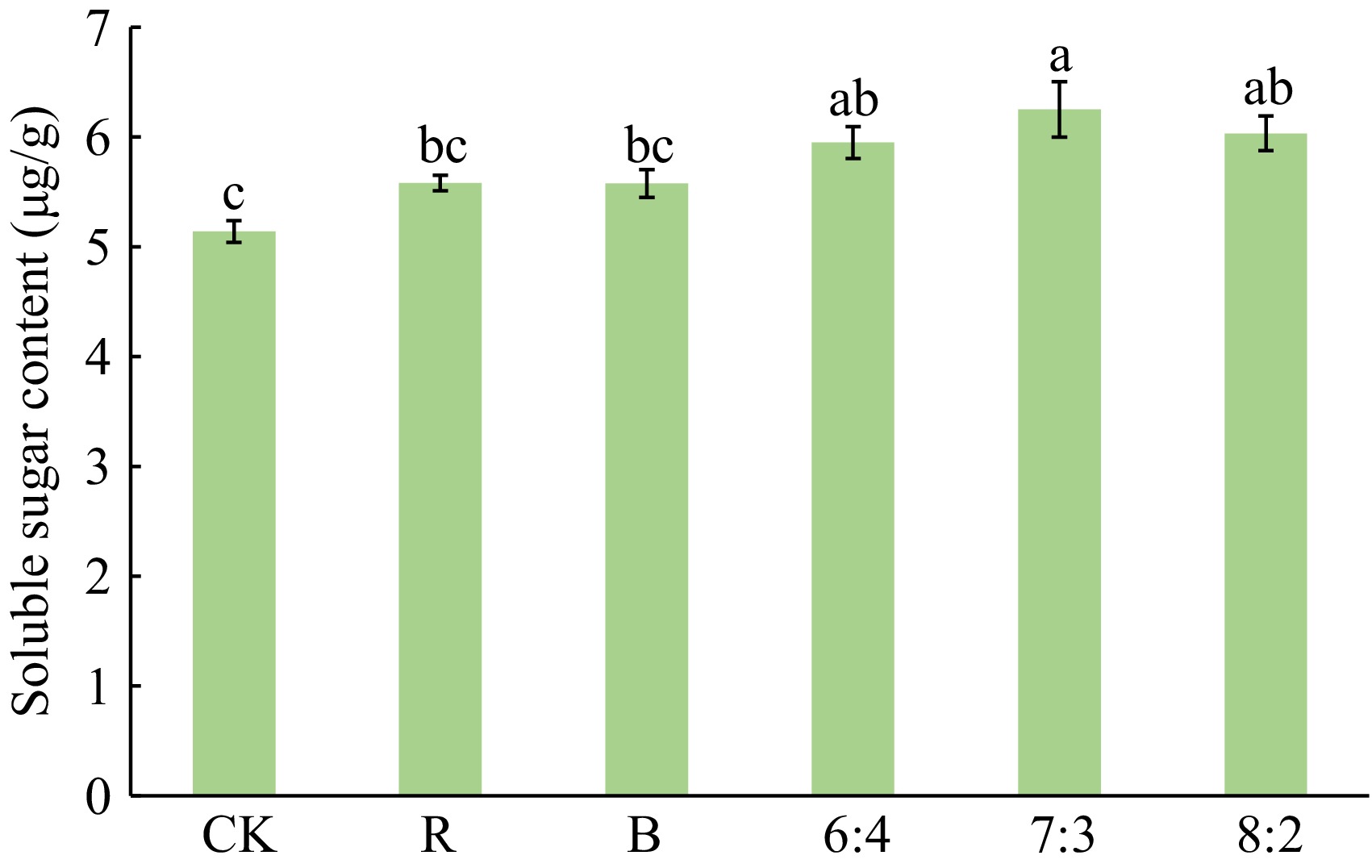

As shown in Fig. 4, the soluble sugar content of Philodendron 'con-go' showed significant differences under different light treatment conditions. Specifically, the plants in the 7:3 had the highest soluble sugar content, followed by the plants in the 8:2 and 6:4. The next highest soluble sugar contents were found in the plants in the R and B groups, and the plants in the CK had the lowest soluble sugar content.

Figure 4.

Effects of different light qualities on soluble sugar of Philodendron 'con-go'. Blue (B), Red (R), 60% Red + 40% Blue (6:4), 70% Red + 30% Blue (7:3), 80% Red + 20% Blue (8:2). Vertical bars indicate standard error (n = 5). Different letters represent a significant difference at p ≤ 0.05 among treatments by Duncan's multiple range test.

Effect on the enzyme activity of Philodendron 'con-go'

-

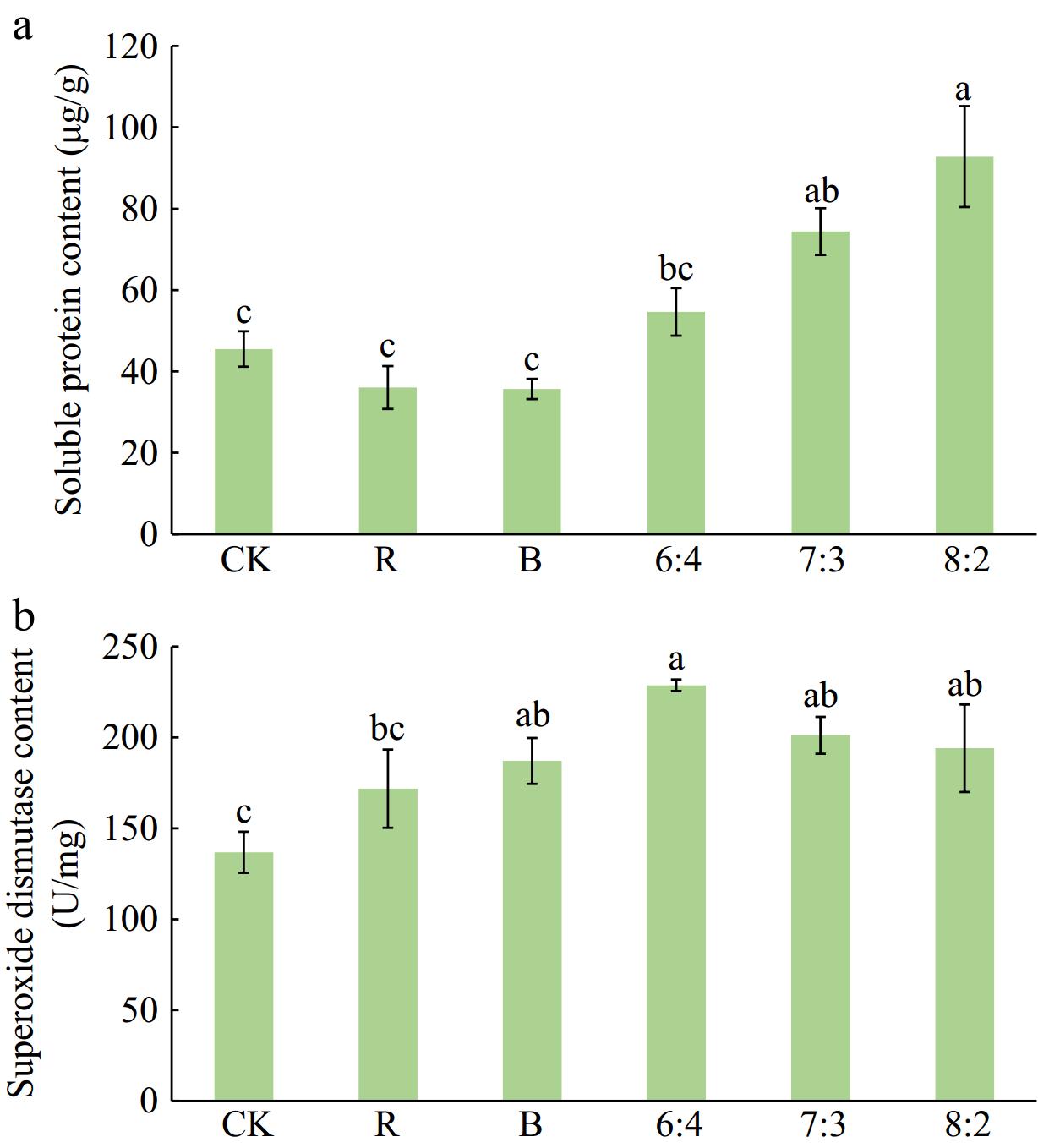

Under different light quality treatments, the soluble protein content of Philodendron 'con-go' was highest in the 8:2 treatment, exceeding all other treatments except the 7:3. The next highest content occurred in the 6:4 treatment. Sequentially lower soluble protein content appeared in the CK, R, and B treatments.

As shown in Fig. 5, SOD activity in Philodendron 'con-go' leaves was highest under the 6:4 treatment. Under combined red-blue light treatments, SOD activity decreased gradually with increasing red light proportion. SOD activities in 6:4, 7:3, 8:2, B, and R treatments were all higher than in CK. The 6:4 treatment exhibited 67.17% higher SOD activity compared to CK.

Figure 5.

Effects of different light qualities on (a) the soluble protein content, and (b) SOD activity of Philodendron 'con-go'. Blue (B), Red (R), 60% Red + 40% Blue (6:4), 70% Red + 30% Blue (7:3), 80% Red + 20% Blue (8:2). Vertical bars indicate standard error (n = 5). Different letters represent a significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) among treatments as determined using Duncan's multiple range test.

-

With increasing proportions of red light (R), the plant height of Philodendron 'con-go' first increased and then decreased, reaching a maximum in the 6:4 treatment. This indicates that although red light promoted growth, red and blue light were optimal for its growth. These results also demonstrate that adjusting the R:B ratio significantly affects plant development. The maximum number of leaves, leaf length, and aboveground fresh weight were found in plants in the 6:4 treatment. However, root number and length peaked in the 7:3 treatment, while underground dry and fresh weight maximized in the 8:2 treatment. In other words, in the treatment with both red and blue LEDs, a high proportion of blue light (B) was beneficial to the growth and development of the aboveground part, whereas a high proportion of red light (R) was beneficial to the development of the underground part. This finding is consistent with reports in cucumber and tomato[37,38], and treating plants with various ratios of red and blue light was found to result in growth that was higher than that of plants treated either with monochromatic light or CK.

Light quality is an important condition affecting the synthesis of photosynthetic pigments[6,28]. Meng et al.[39] found that the content of photosynthetic pigments in tobacco leaves was highest with white light, followed by red light and blue light in that order. In this study, the levels of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoids were the highest in the plants in the 6:4 treatment, and the levels of chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b were the lowest in the plants in the B treatment. These results suggest that combined red and blue light at appropriate ratios promotes photosynthetic pigment accumulation in leaves. Similar findings have been reported for daylilies and tobacco[40,41].

This study found no significant changes in the Fv/Fm of Philodendron 'con-go' under different light quality treatments; although values differed, differences were insignificant. However, the ΦPSII and qP values fluctuated significantly under different light quality treatments, and there were significant differences between the ΦPSII and qP values in the control and in the 6:4 and 7:3 treatment groups. These results indicate that an appropriate combination of red and blue light can promote the openness of the PSII reaction center, thus allowing the plant to use light energy for photosynthesis more efficiently[42,43]. Higher NPQ values indicate greater proportions of absorbed light that cannot be utilized effectively, impairing plant growth[44]. The minimum NPQ value was observed at 6:4, showing significant differences compared to the control. Notably, NPQ under monochromatic red light was significantly higher than CK, while no significant difference was found under monochromatic blue light. This phenomenon may be attributed to the pseudo-stress environment induced by red light treatment, which potentially leads to excess light energy absorption by PSII antenna pigments that cannot be effectively utilized and is subsequently dissipated as thermal energy. The results showed that a red-blue monochromatic light treatment was much inferior to a red-blue light combination treatment[45,46], with the 6:4 ratio being optimal.

Photosynthesis depends on the fluorescence parameters of chlorophyll, and is an important factor affecting plant growth and development[47]. In this study, Pn and Ci peaked in the 7:3 treatment, while transpiration and gs rates peaked in the 6:4 treatment. Plants in both treatments outperformed those under monochromatic R/B light and the fluorescent white light control. These results align with prior reports on soybean photosynthetic parameters[48]. The gs, Ci, and Pn values in the plants in the B treatment were higher than those of the plants in the R treatment and the plants in the fluorescent white light control group. These findings are consistent with those of Lin et al., who found that the photosynthetic rate of tobacco seedlings was higher under blue light than red light[49]. Innes et al. also found that the transpiration rate and stomatal conductance gradually decreased as the proportion of blue light in the ratio of red to blue light decreased, which may be due to the fact that blue light can regulate the activity of photosynthetic enzymes and induce and promote the increase of stomatal conductance[50]. The present findings indicate that red-blue light irradiation modulates photosynthetic efficiency and stress resistance by regulating key physiological parameters, including photosynthetic pigment content and stomatal conductance.

Plant roots are important nutritional organs, providing water and nutrients for plant growth, and light quality affects the growth and physiological activity of plant roots. Previous studies have indicated that red and blue light signals can regulate root development via photoreceptor-mediated pathways[51]. This study found that root vigor in Philodendron 'con-go' peaked in the B treatment, followed by the R treatment, and was lowest in the CK. In the plants treated with a combination of red and blue light from LEDs, the root activity showed a decreasing trend as the blue light (B) content in the LED light source decreased. It can be seen that blue light treatment is beneficial to root development in Philodendron 'con-go', which is consistent with Pu's findings[52].

Soluble sugar is the main form of soluble carbohydrate storage and is important in plant carbohydrate metabolism. Thus, it is of great significance in the process of plant carbon metabolism. Light quality affects soluble sugar content through photosensitizer-mediated regulation of sucrose-related enzymes[53]. This study showed that the soluble sugar content of Philodendron 'con-go' reached a maximum value in the plants in the 7:3 treatment. Its content first increased and then decreased with the increase of red light content in LED light sources. These results indicated that R promotes soluble sugar accumulation, and Gao Bo et al. reached the same conclusion based on a study of celery[54]. However, blue light also has a positive effect on the accumulation of soluble sugars in apple leaves[55].

As an important structural substance in plants, soluble protein can both directly and indirectly regulate plant growth and development. Thus, soluble protein content is an important indicator of plant metabolism health[53]. This study showed that the Philodendron 'con-go' in the 8:2 had the highest soluble protein content. This content was significantly higher than that of the plants grown under monochromatic light, which was consistent with the results of a study in red tip photinia[56]. In that study, the soluble protein content was positively correlated with the ratio of red light in the LED red-blue ratio combination treatment. The results showed that red light had a significant promoting effect on the synthesis and accumulation of soluble protein in Philodendron 'con-go' grown under hydroponic conditions. The results of Wu et al.[57] are also consistent with those of this study. However, many scholars have reported different results. These differences could be due to variations in light sources, materials, and test methods.

SOD is a plant endogenous reactive oxygen species scavenger and is the plant's own protective enzyme system. Junyan et al. pointed out that in plants grown under different LED light quality treatment conditions, SOD activity was the highest under blue light and the lowest under red light[58]. The SOD activity of Philodendron 'con-go' leaves under the red and blue light treatments was higher than that of the control plants grown under fluorescent light. This effect indicates that the red and blue light were more conducive to improving the resistance of plants to oxidative stress, and it was most prominent in the plants in the 6:4. The SOD activity gradually increased as the proportion of blue light increased in the combined treatment of red and blue light, and the SOD activity in plants grown under B was higher than that in plants grown under R. It is hypothesized that plants perceive blue light via cryptochromes (CRY). CRY inhibits the E3 ubiquitin ligase CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENESIS 1 (COP1), thereby activating ELONGATED HYPOCOTYL 5 (HY5). Subsequently, HY5 upregulates phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) expression to control phenolic biosynthesis. Many studies have shown that phenolic compound abundance is directly linked to the antioxidant potential of many fruits and vegetables[11,59]. This study showed that blue light has a significant effect on the activity of SOD and reduces the degradation of soluble proteins in plants.

This study investigated the effects of different red-to-blue light ratios on the growth and physiology of Philodendron 'con-go'. The findings revealed that a 6:4 red-to-blue light ratio was most conducive to promoting shoot growth and photosynthetic efficiency, while a higher proportion of red light favored root development. The research uncovered a dual regulatory mechanism by which light quality influences plant growth: directly modulating growth and physiological processes, and indirectly affecting photosynthetic efficiency and stress resistance by regulating key indicators such as photosynthetic pigment content, stomatal conductance, and antioxidant enzyme activity. Notably, blue light significantly enhanced SOD activity and root vigor, whereas red light promoted soluble protein synthesis. These findings not only elucidate the dynamic balancing role of light quality in plant metabolism—highlighting the light adaptation strategy where blue light promotes shoot growth while red light facilitates root development—but also provide new insights for leveraging light quality regulation to improve plant stress resistance. Future research could further explore the molecular mechanisms of light quality regulation, validate the universality of these conclusions, and investigate the effects of light quality on secondary metabolites to optimize light environment control strategies.

-

The above results showed that red and blue light promoted the growth of Philodendron 'con-go'. Specifically, blue light enhanced aboveground growth, whereas red light promoted dry matter accumulation in underground parts. Aboveground growth was optimal in the 6:4 treatment, which performed best. However, maximum root length occurred in the 7:3 treatment, and the highest underground dry weight occurred in the 8:2 treatment. Red light promoted photosynthetic pigment accumulation, most evidently in the 6:4 treatment. Soluble sugar and soluble protein values peaked in the 7:3 and 8:2 treatments, respectively. Red light significantly enhanced these accumulations, while blue light increased root activity. Under 6:4 treatment and 7:3 treatment conditions, fluorescence parameters were optimal for growth, with Pn highest in the 7:3 and E highest in the 6:4. Monochromatic red light increased NPQ, creating a stress-like environment and elevating SOD activity. The 6:4 treatment performed best, indicating an ideal light environment for Philodendron 'con-go'. These results provide theoretical support for commercial production and light-regulation technologies, though the underlying mechanisms require further study.

This work was funded by the University-Industry Cooperation Foundation of Henan Province (Grant No. 162107000068), and the Science and Technology Innovation Fund of Henan Agricultural University (Grant No. KJCX2021A05).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Song Y, Wang Z; data collection: Zhu J, Shang W, Li D, Liu W; analysis and interpretation of results: Zhu J, Shang W, Sun Y, He S; draft manuscript preparation: Zhu J, Shen Y, Song Y, Wang Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Jiale Zhu, Wenqian Shang

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu J, Shang W, Li D, Sun Y, Liu W, et al. 2025. Effects of LED red and blue light quality on the growth and photosynthetic characteristics of Philodendron 'con-go' hydroponic seedlings. Technology in Horticulture 5: e038 doi: 10.48130/tihort-0025-0033

Effects of LED red and blue light quality on the growth and photosynthetic characteristics of Philodendron 'con-go' hydroponic seedlings

- Received: 02 March 2025

- Revised: 14 August 2025

- Accepted: 12 September 2025

- Published online: 01 December 2025

Abstract: Philodendron 'con-go' was used to study the effects of different red-to-blue light ratios on its physiological indices. Six light treatments were applied: Fluorescent Daylight Lamp (CK), and RB (100% Blue, 60% R + 40% B, 70% R + 30% B, 80% R + 20% B, 100% Red) via LEDs. Results showed both red and blue light benefited Philodendron 'con-go' growth. Red light aided underground dry matter accumulation and photosynthetic pigment buildup, while blue light helped aboveground dry matter accumulation and root activity enhancement. Under the 6:4 treatment, Philodendron 'con-go' displayed better morphological parameters, chlorophyll content, photosynthetic parameters, and antioxidant enzyme activity. The 6:4 group's chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoids were 43.79%, 154.76%, and 112.28% higher than CK. In chlorophyll fluorescence parameters, the 6:4 group had 72.73% and 83.33% higher ΦPSII and qP, and 21.33% lower NPQ than CK. The optimal treatment increased Pn by 32.35% and E by 40% compared to CK. For antioxidant enzyme activity, the 6:4 group's SOD was 67.17% higher than CK. Overall, the 6:4 treatment is a suitable indoor light environment and is recommended for Philodendron production and application.

-

Key words:

- Light quality /

- Light emitting diode /

- Philodendron /

- Antioxidant enzyme /

- Photosynthetic parameters