-

Sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) is highly valued by consumers for its unique flavor, vibrant color, and nutritional benefits, with its market value strongly correlated with fruit quality[1−3]. Consumer preferences are driven by key quality attributes of sweet cherries, including firmness, sugar-acid balance, aromatic complexity, and nutrition, which collectively define sensory experience[3,4]. However, these characteristics are highly perishable during storage[5,6]. To mitigate quality deterioration, the recommended handling protocol for sweet cherries in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) regions of the United States involves maintaining a temperature of 0 °C and 90%–95% relative humidity (RH) during storage and transit[5,6]. Additionally, modified atmosphere packaging (MAP, 6.0%–8.0% O2 and > 8.0% CO2) liners have been widely recommended in PNW regions for over a decade, as they have proven effective in enhancing postharvest performance[7−10]. Therefore, when the above practices are properly implemented, these MAP liners can extend the storage life of sweet cherries by up to 6 weeks while maintaining optimal eating quality[11,12].

In PNW regions, more than half of the sweet cherries produced were late-season sweet cherry cultivars, including 'Lapins', 'Skeena', 'Regina', and 'Sweetheart'. However, due to the narrow harvest window, labor shortages, and variable production elevation (PE) from 0–750 m above sea level (MASL), a significant proportion of late-maturing sweet cherries from high-elevation orchards have to be delayed for harvesting or abandoned. Prior studies in Greece indicated that early-maturing sweet cherry cultivars, such as 'Byrlat', 'Van', Tragana', and 'Mpakirtzeika', from high-elevation orchards exhibited higher antioxidant levels compared to those from lower PE[13]. However, in PNW regions, little information is available for growers to plant the late-maturing sweet cherry cultivars at different PE; therefore, investigating how PE impacts the quality of these cultivars was a critical knowledge gap for local growers to decide what the optimum PE and cultivars to plant were. To address these knowledge gaps, this study evaluated three major late-maturing sweet cherry cultivars from four orchards spanning elevations of 117 to 697 MASL, aiming to provide useful insights for orchard site and cultivar selection.

Irrespective of cultivar, PE, planting/storage conditions, or packaging materials, elevated respiration rates and produced off-flavor in sweet cherries, are both key indicators of physiological senescence, leading to economic losses after long-term storage[14,15]. The development of off-flavor was primarily associated with changes in aromatic volatile compounds[16]. Furthermore, alterations in aromatic volatile compounds occurred earlier than sensory determination[17]. Therefore, reducing respiration rates might help delay the losses in aromatic volatile compounds after an extensive storage duration. In pears, studies had shown that fruit harvested at 610 m displayed higher respiration rates than those from 150 m[18]. In sweet cherries, however, little information was available to determine whether PE impacts fruit respiration and their susceptibility to off-flavor and losses in aromatic volatile compounds. Therefore, the second objective was to reveal the relationships among respiration rate, quality parameters, antioxidant properties, and sensory quality of flavor between pre-storage and after storage, and to understand the dynamic changes in aromatic volatile compounds, which are critical for optimizing postharvest technologies for sweet cherries grown at different elevations. Ultimately, the goal was to provide actionable guidance for growers to establish orchards and supply high-quality cherries with longer flavor to overseas markets.

-

The 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' cherries were obtained during the 2018–2019 harvest seasons. Furthermore, the meteorological data from both growing seasons are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. Gebbers Farms collected the cherries of each cultivar from the different production locations, which were 132, 268, 550, and 697 MASL for 'Skeena' cherries; 117, 331, 502, and 688 MASL for 'Lapins' cherries; and 152, 365, 518, and 640 MASL for 'Sweetheart' cherries in Brewster, WA, USA. 'Skeena' and 'Lapins' trees were grafted on Mazzard rootstock; the 'Sweetheart' trees were grafted on Gisela 6 rootstock. All trees in each location were maintained with standard fertilizer (45 kg per ha of actual nitrogen was applied once before bloom), herbicide, and pesticide practices. The irrigation was applied for 24 h, once per week from May to October with a capacity of 56.8 L of water per hour. The harvested fruit were processed uniformly as follows: hydrocooled and sterilized (0 °C tap water with 100 mg·L−1 sodium hypochlorite for 5 min), rinsed (0 °C tap water), sorted by commercial electronic fruit grader (MAF RODA, Montauban, France), packed in MAP liners (L207, 8 to 11 kg bags designed for sweet cherry storage, 770 mm × 600 mm, Amcor, Victoria, Australia), and sealed using an elastic band by Gebbers Farms packing lines. Twelve boxes (~9.07 kg per box, row size 9.5 = 28.17 mm in diameter) per cultivar in each location were randomly selected and transported to the Mid-Columbia Agricultural Research and Extension Center in Hood River, OR, USA within 5 h. Then, all fruits were stored in a cold room at 0 °C and 90%–95% relative humidity (RH). Gaseous compositions in bags (i.e., O2 and CO2 concentrations), respiration rate, quality attributes (i.e., fruit firmness [FF], fruit size, soluble solids content [SSC], and titratable acidity [TA]), sensory score of flavor, antioxidants (i.e., total phenolics [TP] and total flavonoids [TF]), antioxidant capacity (i.e., the ability to scavenge 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl [DPPH] and ferric reducing antioxidant power [FRAP]), and volatile aroma compounds were evaluated on 50 cherries per replicate (three replications and two boxes per replicate in each location) after packaging and 5 weeks of storage at 0 °C and 90%–95% RH. Due to the similar meteorological data and trends of FF (only FF was evaluated in 2018, Supplementary Table S2) between the two years, the full evaluations were conducted in 2019.

Assessments of gaseous compositions in bags and respiration rate

-

The concentrations of O2 and CO2 per replicate were assessed using the O2/CO2 analyzer (Model 900161, Bridge Analyzers Inc., Alameda, CA, USA) every week. A silicon septum was glued to each MAP liner to prevent gas leakage at the sampling site. Fruits per replicate were sealed in a glass container (960 mL) at 0 °C. After 1 h incubation, the headspace CO2 concentration was determined using the O2/CO2 analyzer. Respiration rate (RR) was expressed as μg CO2 kg−1·s−1 on a fresh weight basis.

Evaluations of quality attributes and sensory score of flavor

-

Fruit firmness (FF) per replicate was nondestructively measured using a FirmTech-2 instrument (BioWorks Inc., Stillwater, OK, USA) and was expressed as N. After determination of FF, pits, and stems were removed, and the fruits were halved. One half were selected at random for soluble solids content (SSC), and titratable acidity (TA) evaluation; the remainder were quick-frozen, ground in liquid N2, then stored at −80 °C. One hundred grams per replicate were juiced for 3 min using a juicer (Model 6001, Acme Juicer Manufacturing Co., Sierra Madre, CA, USA) equipped with a uniform milk filter strip (Schwartz Manufacturing Co., Two Rivers, WI, USA). SSC was determined using a refractometer (Model PAL-1, Atago, Tokyo, Japan) and expressed as a percentage. TA was determined by titrating 10 mL of juice plus 40 mL of distilled water to pH 8.1 with a 0.1 N NaOH solution using a titrator (Model DL-15, Mettler-Toledo, Zurich, Switzerland) and expressed as a percentage of malic acid. Sensory score of flavor (SSF) was scored on a nine-point hedonic scale (1 = extremely poor, 3 = poor, 5 = acceptable (limit of marketability), 7 = good, 9 = excellent)[19]. Before the first evaluation session, a total of 10 panelists were selected and oriented on scale anchor points and definitions. Five cherries per replicate were sampled by each panelist.

Determinations of antioxidants and antioxidant capacity

-

The 0.5 g of frozen sample per replicate were extracted in 5 mL ethanol/acetone (7/3, v/v) at 4 °C for 1 h, and centrifuged at 8,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were collected and stored at –20 °C for subsequent evaluations.

For TP determination[20], a 0.2 mL aliquot of the extract (the blank using ethanol/acetone solution) per replicate was added to 4.9 mL of distilled water and 0.3 mL of 0.25 M Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. After mixing for 5 min at 20 °C, 0.6 mL of 1 M Na2CO3 was added, and the mixture was incubated in darkness at 20 °C for 2 h. Absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a spectrophotometer (model T6, Purkinje General Instrument Co., Beijing, China). A standard calibration curve was constructed using gallic acid, and the data were expressed on a fresh weight basis as g·kg−1.

For TF determination[20], a 1 mL aliquot of the extract (the blank using ethanol/acetone solution) per replicate was added to 2.7 mL of 30 % (v/v) ethanol, 0.15 mL of 0.5 M NaNO2, and 0.15 mL of 0.3 M AlCl3. After mixing for 5 min at 20 °C, absorbance at 506 nm was measured. A standard calibration curve was constructed using rutin, and the data were expressed on a fresh weight basis as g·kg−1.

For the ability to scavenge DPPH determination[20], a 0.1 mL aliquot of the extract (the blank using ethanol/acetone solution) per replicate was added to 0.9 mL of ethanol/acetone (7/3, v/v) and 3 mL of 62.5 μM DPPH in methanol. A control sample consisting of the same volume of solvent was used to measure the maximum DPPH absorbance. The mixture was shaken vigorously and incubated at 37 °C in darkness for 30 min, and absorbance at 517 nm was recorded to determine the concentration of DPPH remaining. A standard calibration curve was constructed using trolox, and the data were expressed on a fresh weight basis as g·kg−1.

For FRAP determination[20], stock solutions included 25 mL of 0.3 M acetate buffer (pH 3.6), 2.5 mL of 10 mM 2,4,6-tripyridyl-S-triazine (TPTZ) solution in 40 mM HCl, and 2.5 mL of 20 mM FeCl3. A 0.1 mL aliquot of the extract (the blank using ethanol/acetone solution) per replicate was added to 0.9 mL of ethanol/acetone (7/3, v/v) with a 3 mL fresh working solution for 10 min at 37 °C. Absorbance was measured at 593 nm. A standard calibration curve was constructed using Trolox, and the data were expressed on a fresh weight basis as g·kg−1.

Sample extraction and determination of aromatic volatile compounds

-

After packaging and after 5 weeks of storage at 0 °C, 2 g of frozen sample per replicate were ground in liquid N2, then transferred to a 2-mL vial with 0.5 mL of saturated NaCl solution. The aroma compounds were extracted with headspace solid phase microextraction. The volatiles were assayed by a gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometer (Model 6890/5973 N, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a DB-5 column (60 m length, 0.25 mm inner diameter, and 1 μm film thickness, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The injector temperature was 250 °C; the initial oven temperature was 40 °C for 3.5 min, which was increased to 100 °C at a rate of 10 °C·min−1, increased to 180 °C at a rate of 7 °C·min−1, and then to 280 °C at a rate of 25 °C·min−1, where it was maintained for 5 min. The mass spectrometer was operated in electron impact mode at 70 eV. The temperatures of the quadrupole mass detector, ion source, and transfer line were set at 150, 230, and 280 °C, respectively. The ion monitoring mode was selected for the identification and quantification of analyses. The peaks of the volatile aroma compounds were identified by comparison of their mass spectra with library entries (NIST/EPA/NIH Mass Spectral Library, 2.0 version). Levels of aromatic volatile compounds were calculated and expressed as the area units of their abundance.

Statistical analysis

-

Experiments were performed using a completely randomized design. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for assessing all data using Fisher's protected least significant difference (LSD) test at p < 0.05. The regression coefficients of linear, quadratic, and cubic between PE and respiration rate, FF, SSC, TA, SSF, TP, TF, DPPH, and FRAP per cultivar were analyzed by Pareto analysis of ANOVA using OriginPro software (version 2022b, OriginLab Co., Northampton, MA, USA). The determination coefficients (R2) from the linear, quadratic, and cubic models were used to reflect the statistical significance of the fitted polynomial equation. Principal component analysis (PCA) was applied to analyze the data of respiration rate, quality attributes, antioxidants, and antioxidant capacity in each cultivar and represented the associations after packaging (AP) and after storage (AS). Principal components with variances less than 10%, or eigenvalues less than 1.0 were removed.

-

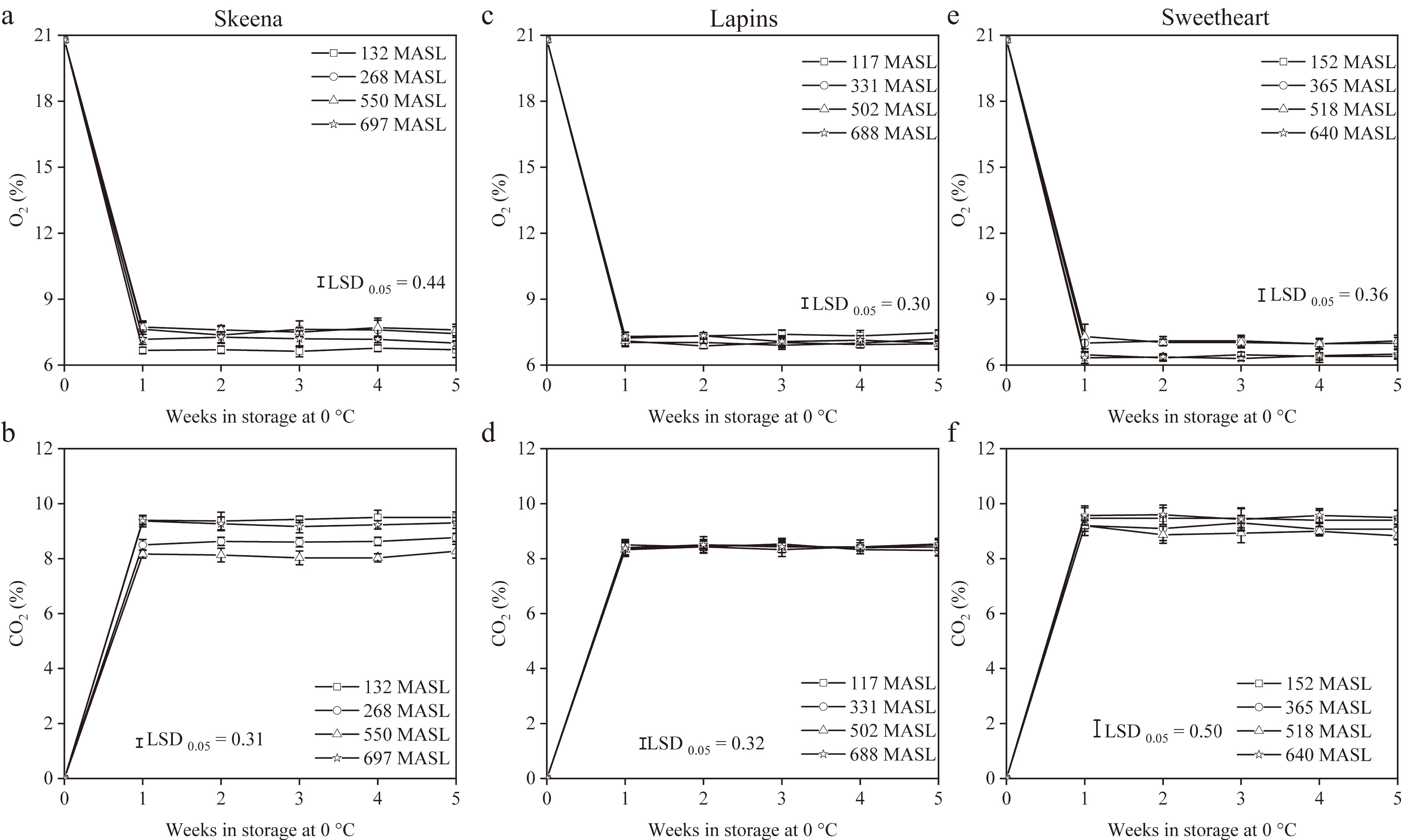

For gaseous composition evaluation (Fig. 1), regardless of cultivar and PE, O2 concentrations decreased sharply, while CO2 concentrations increased rapidly between post-packaging and 1 week of storage at 0 °C, eventually reaching relative stability from 1 to 5 weeks of storage. For 'Skeena' cherries, equilibrium O2 and CO2 concentrations across PE from 132 to 697 MASL ranged from 6.63% to 7.73%, and 8.03% to 9.50%, respectively; the lower O2 concentrations with higher CO2 concentrations were observed when cherries were harvested at 132 and 697 MASL compared to the fruit that were collected from 268 and 550 MASL. For 'Lapins' cherries, equilibrium O2 and CO2 concentrations across PE from 117 to 688 MASL ranged from 6.87% to 7.47%, and 8.30% to 8.53%, respectively; no difference was found for CO2 concentration among all PE. For 'Sweetheart' cherries, equilibrium O2 and CO2 concentrations across PE from 152 to 640 MASL ranged from 6.30% to 7.30%, and 8.83% to 9.60%, respectively; the lower O2 concentrations with high CO2 concentrations were found when cherries were harvested at 152 and 640 MASL compared to the fruit that were harvested at 365 and 518 MASL.

Figure 1.

O2 and CO2 concentrations of 'Skeena' (a) and (b), 'Lapins' (c) and (d), and 'Sweetheart' (e) and (f) sweet cherries from production elevation (PE) ranging from 117 to 697 m above sea level (MASL) after packaging and 1–5 weeks of storage at 0 °C. Vertical bars represent standard deviations (SD).

After packaging, RR of 'Skeena' cherries declined from 3.40 μg CO2 kg−1·s−1 at 132 MASL to 3.19 μg CO2 kg−1·s−1 at 268 MASL before increasing toward 697 MASL, showing significant quadratic and cubic models but no linear model (Table 1). For 'Lapins' cherries, RR decreased from 2.88 μg CO2 kg−1·s−1 at 117 MASL to 2.51 μg CO2 kg−1·s−1 at 688 MASL, with significant linear, quadratic, and cubic models. For 'Sweetheart' cherries, RR decreased from 2.80 μg CO2 kg−1·s−1 at 152 MASL to 2.39 μg CO2 kg−1·s−1 at 518 MASL before rising at 640 MASL, aligning with quadratic and cubic models. After 5 weeks of storage at 0 °C, RR trends were similar to the patterns of RR after packaging. For 'Skeena' cherries, the RR declined from 132 to 268 MASL and increased toward 697 MASL. For 'Lapins' cherries, a consistent RR drop was observed from 117 to 668 MASL. Notably, no RR difference occurred among 331–688 MASL. For 'Sweetheart' cherries, RR decreased from 152 to 365 MASL and then rose to 640 MASL, with quadratic and cubic models remaining significant.

Table 1. Changes in respiration rate (RR) of 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' sweet cherries from production elevation (PE) from 117 to 697 MASL after packaging and 5 weeks of storage at 0 °C.

Cultivar Elevation

(MASL)RR (μg CO2 kg−1·s−1) After packaging After 5 weeks of

storage at 0 °CSkeena 132 3.40 b 2.86 b 268 3.19 c 2.47 d 550 3.29 bc 2.67 c 697 3.55 a 3.02 a R2 of linear model 0.136ns 0.077ns R2 of quadratic model 0.881*** 0.908*** R2 of cubic model 0.881*** 0.920*** Lapins 117 2.88 a 2.66 a 331 2.64 b 2.38 b 502 2.57 c 2.38 b 688 2.51 c 2.37 b R2 of linear model 0.862*** 0.624** R2 of quadratic model 0.957*** 0.893*** R2 of cubic model 0.934*** 0.933*** Sweetheart 152 2.80 a 2.30 a 365 2.41 c 1.90 c 518 2.39 c 1.93 c 640 2.64 b 2.11 b R2 of linear model 0.176ns 0.211ns R2 of quadratic model 0.931*** 0.878*** R2 of cubic model 0.940*** 0.879*** Values are presented as means. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among means for each cultivar in each column using Fisher's protected least significant difference (LSD) test at p < 0.05. ns, not significant effect; *, significant effect at the 0.05 level; **, significant effect at the 0.01 level; ***, significant effect at the 0.001 level. Effect of PE on quality attributes of 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' sweet cherries

-

For quality evaluation after packaging (Table 2), the significant decrease in FF (from 4.31 to 3.98 N) of 'Skeena' cherries paralleled the increment in PE (from 132 to 697 MASL), showing significant linear, quadratic, and cubic R2 values; SSC showed a cubic model with the peaking of 19.30% at 550 MASL. TA of 'Skeena' cherries displayed the high values of 0.91% and 0.88% at 268 and 550 MASL, respectively, with no difference between the two PE. For 'Lapins' cherries, FF increased with PE, and the R2 of linear, quadratic, and cubic models were significant; SSC similarly presented significant linear, quadratic, and cubic models, peaking at 17.63% at 502 MASL. Additionally, TA rose from 0.75% at 117 MASL to 0.91% at 331 MASL and stabilized until 688 MASL with a significant R2 of the quadratic and cubic models. For 'Sweetheart' cherries, the fruit at 365 and 640 MASL showed higher FF than those cherries at 152 and 518 MASL; SSC increased from 22.03% at 152 MASL to 23.83% at 365 MASL, stabilizing till 640 MASL. The significance of R2 of linear, quadratic, and cubic models was observed on FF and SSC. However, only the significant R2 of quadratic and cubic models were found in TA; TA displayed the high levels at 365 and 518 MASL.

Table 2. Changes in quality attributes [fruit firmness (FF), soluble solid content (SSC), titratable acidity (TA), and sensory score of flavor (SSF)] of 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' sweet cherries from production elevation (PE) ranging of 117 to 697 MASL after packaging and 5 weeks of storage at 0 °C.

Cultivar Elevation (MASL) After packaging After 5 weeks of storage at 0 °C FF (N) SSC (%) TA (%) FF (N) SSC (%) TA (%) SSF (1–9) Skeena 132 4.31 a 18.10 b 0.79 b 3.96 b 17.07 bc 0.45 ab 6.40 b 268 4.25 a 15.97 c 0.91 a 4.36 a 16.47 c 0.46 ab 7.47 a 550 4.13 ab 19.30 a 0.88 a 3.90 b 17.67 ab 0.49 a 7.30 a 697 3.98 b 17.90 b 0.75 b 4.00 b 18.50 a 0.42 b 6.13 b R2 of linear model 0.663** 0.055ns 0.034ns 0.022ns 0.425* 0.030ns 0.009ns R2 of quadratic model 0.713** 0.136ns 0.844*** 0.235ns 0.665** 0.359ns 0.801*** R2 of cubic model 0.713* 0.928*** 0.845** 0.722* 0.709* 0.643* 0.806** Lapins 117 2.82 c 16.23 c 0.75 b 2.98 b 16.17 b 0.45 c 5.30 b 331 2.92 b 17.10 b 0.91 a 3.23 a 17.43 a 0.51 a 6.37 a 502 3.09 a 17.63 a 0.94 a 3.24 a 17.27 a 0.50 ab 6.03 a 688 3.13 a 16.83 b 0.91 a 3.30 a 16.90 a 0.47 bc 5.27 b R2 of linear model 0.863*** 0.590** 0.250ns 0.738*** 0.200ns 0.060ns 0.004ns R2 of quadratic model 0.871*** 0.914*** 0.800*** 0.874*** 0.751** 0.735** 0.873*** R2 of cubic model 0.907*** 0.916*** 0.864*** 0.910*** 0.794** 0.795** 0.906*** Sweetheart 152 2.68 c 22.03 b 0.97 c 2.93 c 22.67 a 0.55 c 7.20 b 365 3.29 a 23.83 a 1.20 a 3.49 b 23.30 a 0.73 a 7.50 a 518 2.99 b 24.17 a 1.21 a 3.61 b 23.50 a 0.74 a 7.00 bc 640 3.22 a 23.77 a 1.08 b 3.90 a 22.47 a 0.63 b 6.80 c R2 of linear model 0.420* 0.538** 0.228ns 0.920*** 0.000ns 0.216ns 0.349* R2 of quadratic model 0.581* 0.796*** 0.943*** 0.928*** 0.351ns 0.887*** 0.686** R2 of cubic model 0.898*** 0.796** 0.947*** 0.952*** 0.410ns 0.903*** 0.801** Values are presented as means. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among means for each cultivar in each column using Fisher's protected least significant difference (LSD) test at p < 0.05. ns, not significant effect; *, significant effect at the 0.05 level; **, significant effect at the 0.01 level; ***, significant effect at the 0.001 level. For the quality evaluation after 5 weeks of storage at 0 °C (Table 2), FF of 'Skeena' cherries had a peak at 268 MASL, and only the cubic model was significant; SSC increased to 18.50% at 697 MASL, with all models showing significance. TA at 0.42%–0.49% with the significant cubic model was observed across the PE. SSF had the significant R2 of quadratic and cubic models, scoring high at 268 and 550 MASL. For 'Lapins' cherries, FF and SSC rose from 2.93 N and 16.17% at 117 MASL to 3.49 N and 17.43% at 331 MASL, respectively, then remained stable between 331 and 688 MASL. Both TA and SSF peaked at 331 and 502 MASL with no difference between the two PE. No significant R2 of the linear model was found in SSC, TA, or SSF, but the R2 of the quadratic and cubic models were significant. For 'Sweetheart' cherries, FF and SSF exhibited the significant R2 of linear, quadratic, and cubic models, peaking at 640 and 356 MASL, respectively. No difference in SSC was found among all PE, and the R2 of the three models was not significant. TA peaked at 0.73% and 0.74% at 365 and 518 MASL, respectively, with a significant R2 of quadratic and cubic models.

Effect of PE on antioxidant properties of 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' sweet cherries

-

For the antioxidant properties after packaging (Table 3), TP, TF, DPPH, and FRAP of 'Skeena' cherries showed no significant R2 of the linear model, while the R2 of the quadratic and cubic models were significant; in addition, all four parameters had peaks at 268 MASL. For 'Lapins' cherries, TP, TF, DPPH, and FRAP exhibited the significant R2 of linear, quadratic, and cubic models; all four parameters increased from 117 to 331 MASL and retained the stable levels with no difference among 331, 502, and 688 MASL. For 'Sweetheart' cherries, similar to 'Skeena' cherries, only the significant R2 of quadratic and cubic models were observed in TP, TF, DPPH, and FRAP. The high levels of all four parameters were found at 518 MASL.

Table 3. Changes in antioxidant properties (total phenolics [TP], total flavonoids [TF], the ability to scavenge 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl [DPPH], and ferric reducing antioxidant power [FRAP]) of 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' sweet cherries from production elevation (PE) ranging from 117 to 697 MASL after packaging and 5 weeks of storage at 0 °C.

Cultivar Elevation (MASL) After packaging After 5 weeks of storage at 0 °C TP (g·kg−1) TF (g·kg−1) DPPH (g·kg−1) FRAP (g·kg−1) TP (g·kg−1) TF (g·kg−1) DPPH (g·kg−1) FRAP (g·kg−1) Skeena 132 5.28 c 5.41 c 5.69 c 5.95 b 4.84 b 5.03 b 4.98 c 4.87 b 268 6.17 a 6.36 a 6.89 a 7.15 a 5.00 a 5.20 a 5.32 a 5.67 a 550 5.69 b 6.17 b 6.76 b 6.96 a 4.84 b 5.03 b 5.12 b 5.58 a 697 5.17 c 5.18 d 5.61 c 5.89 b 4.66 c 4.90 c 4.96 c 4.68 c R2 of linear model 0.022ns 0.013ns 0.000ns 0.000ns 0.283ns 0.228ns 0.018ns 0.007ns R2 of quadratic model 0.911*** 0.989*** 0.987*** 0.978*** 0.812*** 0.782** 0.766** 0.967*** R2 of cubic model 0.978*** 0.991*** 0.991*** 0.979*** 0.838** 0.860*** 0.861*** 0.977*** Lapins 117 6.75 b 7.09 b 6.61 b 6.58 b 5.24 b 6.08 b 5.05 b 5.13 b 331 7.76 a 7.95 a 7.66 a 7.91 a 5.95 a 6.38 a 6.09 a 5.25 a 502 7.77 a 7.96 a 7.66 a 7.87 a 5.86 a 6.41 a 6.11 a 5.21 ab 688 7.79 a 7.97 a 7.70 a 7.91 a 5.86 a 6.18 b 6.10 a 5.18 ab R2 of linear model 0.643** 0.648** 0.659** 0.628** 0.494* 0.076ns 0.649** 0.049ns R2 of quadratic model 0.927*** 0.936*** 0.936*** 0.930*** 0.852*** 0.857*** 0.955*** 0.521* R2 of cubic model 0.968*** 0.974*** 0.983*** 0.985*** 0.940*** 0.859*** 0.993*** 0.600ns Sweetheart 152 7.32 c 7.58 c 7.49 d 7.30 d 5.38 c 5.61 c 5.53 d 5.28 b 365 8.27 a 8.51 b 8.76 b 8.69 b 5.95 a 6.06 b 6.09 b 6.07 a 518 8.35 a 8.64 a 8.94 a 8.84 a 6.02 a 6.19 a 6.25 a 6.15 a 640 7.83 b 7.67 c 7.94 c 7.69 c 5.62 b 5.67 c 5.84 c 5.25 b R2 of linear model 0.292ns 0.044ns 0.163ns 0.119ns 0.198ns 0.061ns 0.306ns 0.015ns R2 of quadratic model 0.955*** 0.927*** 0.956*** 0.957*** 0.939*** 0.866*** 0.927*** 0.928*** R2 of cubic model 0.963*** 0.988*** 0.990*** 0.991*** 0.959*** 0.960*** 0.973*** 0.991*** Values are presented as means. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among means for each cultivar in each column using Fisher's protected least significant difference (LSD) test at p < 0.05. ns, not significant effect; *, significant effect at the 0.05 level; **, significant effect at the 0.01 level; ***, significant effect at the 0.001 level. For the quality evaluation after 5 weeks of storage at 0 °C (Table 3), all parameters of 'Skeena' cherries retained the significant R2 of quadratic and cubic models, peaking at 268 MASL. For 'Lapins' cherries, TP and DPPH had the significant R2 of all three models, while TF and FRAP had the significant R2 of quadratic and cubic models; TP, TF, DPPH, and FRAP were similar to the trends observed after packaging, rising from 117 to 331 MASL with no difference observed among 331–688 MASL. For 'Sweetheart' cherries, the R2 of quadratic and cubic models remained significant for all four parameters: TP, TF, DPPH, and FRAP at 518 MASL displayed the highest levels.

PCA analysis

-

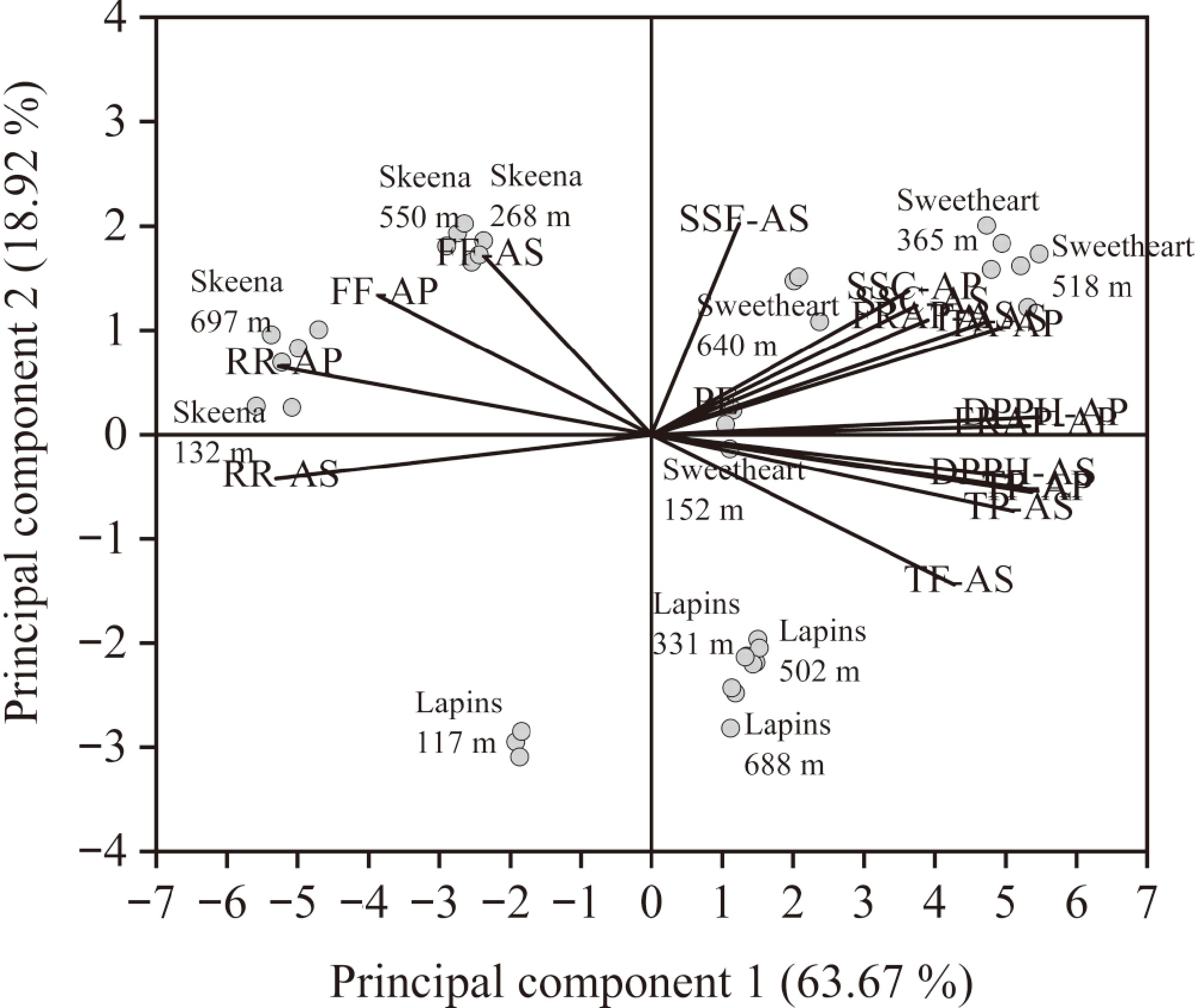

Two principal components, 63.67% from principal component (PC) 1 and 18.92% from PC2, together accounted for 82.59% of the overall variation in the data (Supplementary Table S3). The TA-after packaging (AP), TP-AP, TF-AP, DPPH-AP, FRAP-AP, TA-AS, TP-after storage (AS), and DPPH-AS were positively correlated with PC1, whereas RR-AP and RR-AS were negatively correlated, suggesting that PC1 might be related to fruit respiratory, TA accumulation, and antioxidant properties (Supplementary Table S4). For PC2, high positive correlations were observed in PE, FF-AP, SSC-AP, FF-AS, SSC-AS, SSF-AS, and FRAP-AS, whereas negative correlations were found in TF-AS, suggesting that PC2 might be associated with PE, FF, SSC accumulation, and flavor development. PCA results indicated that, compared to the 'Skeena' and 'Lapins' cherries, the scores of the 'Sweetheart' cherries from four orchards were highly correlated with the characteristics of PE, TA-AP, SSC-AP, DPPH-AP, FRAP-AP, TA-AS, SSC-AS, SSF-AS, and FRAP-AS, especially in the cherries among 365–640 MASL (Fig. 2). For 'Skeena' cherries, fruit at 268 and 550 MASL had characteristics of FF-AS and were close to the characteristic of SSF-AS. For 'Lapins' cherries, compared to the fruit at 117 and 688 MASL, the scores of cherries at 331 and 502 MASL were moved closer to the characteristics of PE and SSF-AS.

Figure 2.

Principal component analysis of respiration rate (RR), fruit firmness (FF), soluble solid content (SSC), titratable acidity (TA), sensory score of flavor (SSF), total phenolics (TP), total flavonoids (TF), the ability to scavenge 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) of 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' cherries from four orchards from production elevation (PE) ranging from 117 to 697 MASL after packaging (AP), and storage (AS).

Effect of PE on aromatic volatile compounds of 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' sweet cherries

-

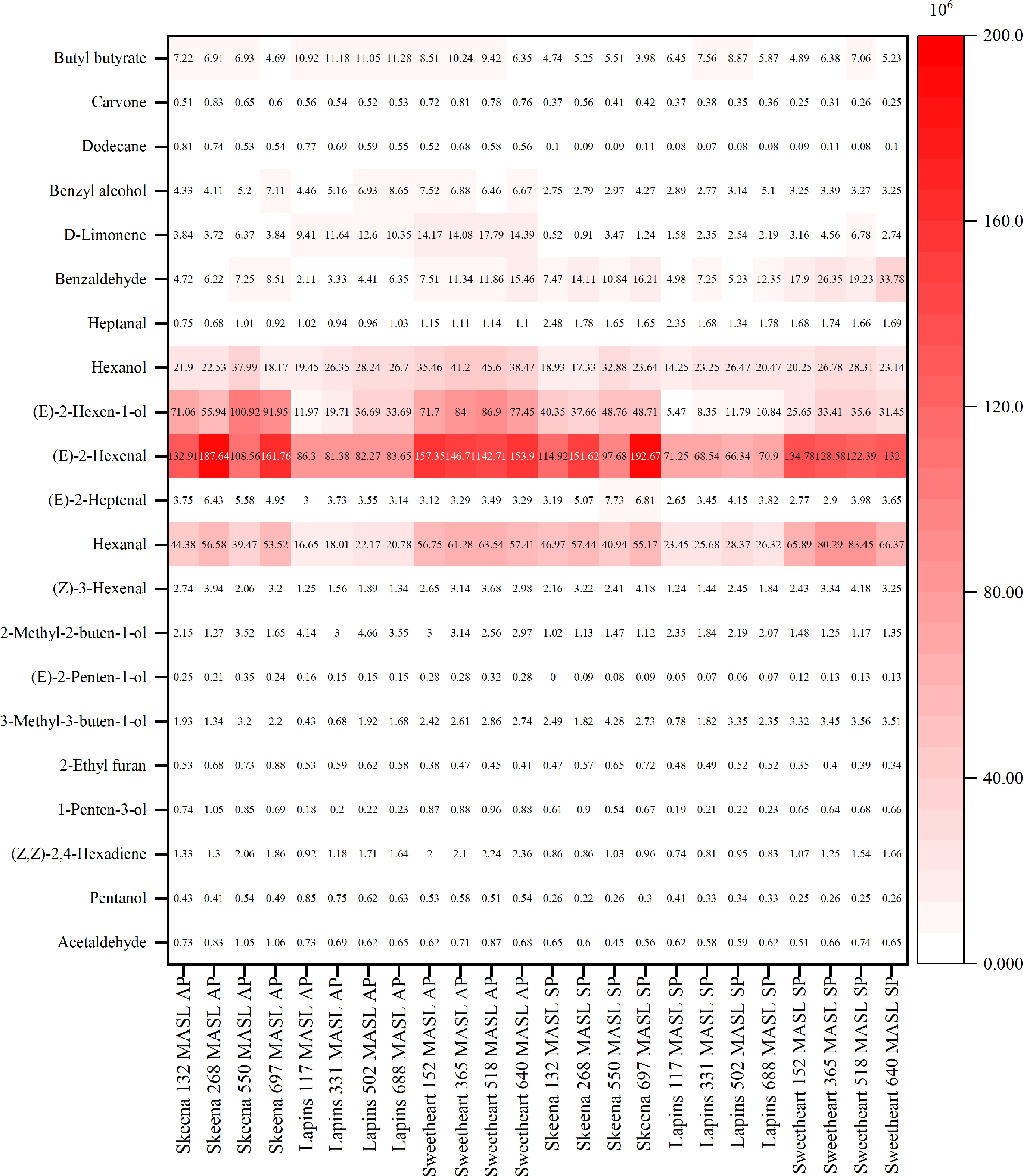

In total, 21 aromatic volatile compounds were identified in 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' sweet cherries from four orchards with different PE (Fig. 3), belonging to six chemical classes, including eight alcohols, seven aldehydes, two hydrocarbons, two terpenoids, one ester, and one heterocyclic compound (Supplementary Table S5). In addition, the alcohol (i.e., [E]-2-hexen-1-ol) and aldehyde (i.e., [E]-2-hexenal) compounds showed higher area units of their abundance compared to the other classes. Irrespective of cultivar and PE, the 15 aromatic volatile compounds decreased after 5 weeks of storage at 0 °C, including acetaldehyde, pentanol, (Z,Z)-2,4-hexadiene, 1-penten-3-ol, 2-ethyl furan, 3-methyl-3-buten-1-ol, (E)-2-penten-1-ol, 2-methyl-2-buten-1-ol, (E)-2-hexenal, (E)-2-hexen-1-ol, hexanol, D-limonene, benzyl alcohol, dodecane, carvone, and butyl butyrate, while the three aromatic volatile compounds increased, including hexanal, heptanal, and benzaldehyde. Notably, 'Skeena' and 'Lapins' cherries at 132–268 and 117–331 MASL showed decreases in (Z)-3-hexenal and (E)-2-heptenal after storage, while cherries at 550–697 and 502–688 MASL showed increases, respectively. 'Sweetheart' cherries at 152 MASL similarly showed decreases in (Z)-3-hexenal and (E)-2-heptenal after storage, while fruit at 518 and 640 MASL displayed the increases.

Figure 3.

Changes in aromatic volatile compounds of 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' sweet cherries from production elevation (PE) ranging from 117 to 697 MASL after packaging (AP), and storage (AS). Values are mean area units (divided by 106). Color scale represents the peak number corresponds to elution order.

-

As non-climacteric fruits, the postharvest quality of sweet cherries is significantly influenced by respiration rates, which are a critical factor in accelerating fruit senescence[14,21]. However, MAP has been widely adopted as an effective strategy to reduce respiration rates, thereby extending the storage life of sweet cherries for 4–6 weeks at 0 °C by sustaining the equilibrated O2 (6.0%–8.0%) and CO2 (> 8.0%) concentrations in bags, irrespective of cultivar[7,9,11,18,22,23]. In the present study, regardless of PE, the O2 and CO2 concentrations of 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' cherries from all PE were sustained at 6.30%–7.73% and 8.03%–9.60%, respectively, throughout the entire 5-week storage period at 0 °C (Fig. 1). These results indicated that neither PE nor cultivar would affect the effectiveness of MAP when the appropriate gas compositions in bags and the storage condition at 0 °C were maintained during storage. However, 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' cherries displayed the distinct gas compositions and RR in response to PE (Table 1). For example, the higher O2 concentration with lower CO2 concentration and RR were observed in 'Skeena' and 'Sweetheart' cherries at 268–550 and 365–518 MASL, respectively, compared to those of low or high PE; RR of 'Lapins' cherries exhibited declining trends with the increase in PE, especially at 502–688 MASL. Additionally, the significant R2 of the linear model was found between PE and RR in 'Lapins' cherries, but not in 'Skeena' or 'Sweetheart' cherries. These findings suggested that the 'Skeena' and 'Sweetheart' cherries were more suitable for growing in the mid-elevation sites, while the 'Lapins' cherries were sufficient to plant at high-elevation sites, perhaps due to their high adaptability[24].

Previous research had demonstrated that warm-humid low-altitude zones proved ideal for growing early-ripening, large-fruited sweet cherry cultivars, owing to compressed fruit development periods[25−28]. In contrast, elevated mountainous regions were suited for late-maturing cultivars, due to the long growing season and extended harvest windows[29]. In this study, high FF values occurred for 'Skeena' cherries at 132 and 268 MASL, 'Lapins' cherries at 502 and 688 MASL, and 'Sweetheart' cherries at 365 and 640 MASL (Table 2). Post-storage observations further demonstrated that 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' cherries grown at 268, 331–688, and 640 MASL, respectively, maintained superior FF, indicating that three late-maturing sweet cherry cultivars were all suitable for growing from mid to high PE, due to providing a positive effect on enhancing FF; as a result, high FF would contribute to minimizing the development of surface pitting during storage[30−32]. However, previous studies indicated that rising elevations progressively diminished fruit weight and moisture in apricot fruit[33], and decreased the SSC of mangoes[34]. Although no weight loss data were evaluated in this study, the retained high levels of SSC, TA, and SSF were observed in 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' cherries at 550, 502, and 365 MASL, respectively, after packaging and storage (Table 2), indicating that selecting a PE site between 365 and 550 MASL to build an orchard in PNW regions had greater benefits in increasing sugar and acid accumulations and maintaining desirable flavor in late-maturing sweet cherry cultivars.

On the other hand, the geographic elevation profoundly influences the antioxidant content of sweet cherries, with orchards at higher elevations yielding fruits richer in antioxidant compounds compared to those at lower elevations[13]. Furthermore, the late-maturing sweet cherry 'Kordia' maintained consistently high antioxidant activity across both low (200 m), and high (800 m) altitudes[35]. In this study, 'Skeena' cherries at 268 MASL and 'Sweetheart' cherries at 518 MASL showed the peak values in TP, TF, DPPH, and FRAP after packaging and storage; for 'Lapins' cherries, fruit at 331–688 MASL exhibited elevated TP, TF, DPPH, and FRAP levels compared to those at 117 MASL (Table 3). These results indicated that these three late-maturing sweet cherry cultivars grown at high-elevation sites indeed were prone to produce more antioxidants and have higher antioxidant capacity compared to the low-elevation sites. However, cultivar-specific responses drove divergent elevation-antioxidant relationships[13]. Furthermore, the significant R2 of quadratic and cubic models were observed on all four antioxidant parameters in three sweet cherry cultivars, while only significant R2 of linear models were found on TP and DPPH in 'Lapins' cherries. Combined with the results of quality attributes, the present findings indicate that 'Lapins' cherries had a wider suitable PE range than 'Skeena' and 'Sweetheart' cherries. For better utilization and maintaining high antioxidant compounds in 'Skeena' and 'Sweetheart' cherries, the orchard site between 268 and 365 MASL would be suitable for growing.

Beyond the nutritional value and beneficial health, flavor constitutes a critical sensory attribute of sweet cherries that directly correlates with consumer acceptance and market value[36,37]. PCA results revealed that divergent elevation affected the SSF in all three late-maturing sweet cherry cultivars. For example, the scatter plots of 'Skeena' cherries at 268 MASL, 'Lapins' cherries at 331 MASL, and 'Sweetheart' cherries at 640 MASL exhibited close proximity to the SSF characteristic (Fig. 1). These results indicated that the optimum of elevation production was strongly preferred to maintain desirable flavor. However, flavor profiles are principally determined by aromatic volatile compounds, with aldehydes, alcohols, terpenoids, and esters constituting the major classes[38−40]. In this study, aldehydes and alcohols were quantitatively the major volatile compounds present after packaging and storage. Previous studies indicated that hexanal, (E)-2-hexenal, benzaldehyde, and (E)-2-hexen-1-ol were important aroma volatile compounds in 'Bing', 'Van', 'Salmo, 'Lapins', 'Lambert', 'Summit', 'Hongdeng', and 'Sweetheart' cherries[41−43]. Similar results were observed in our study, that the amount of hexanal, (E)-2-hexenal, (E)-2-heptenal, and benzaldehyde in aldehydes and (E)-2-hexen-1-ol and benzyl alcohol in alcohols occupied the large portion of these two classes. Hexenal and (E)-2-hexenal are both products of lipoxygenase activity[41] and have fruity and grassy odors, respectively (Supplementary Table S5). Notably, the increment of hexenal paralleled the observed decrease in (E)-2-hexenal in three sweet cherry cultivars from all PE after storage. In addition, 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' cherries at 268, 502, and 518 MASL, respectively, had the largest quantification after storage, indicating that these cherries retained a desirable fruit flavor. (E)-2-heptenal is formed in a model system including 1-stearoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine with fatty and fruity odor[44]; benzaldehyde, a characteristic of sweet, bitter, almond, and cherry odor, can be produced from the benzyl alcohol to the aldehyde or from hydrolysis of amygdaline[44]; (E)-2-hexen-1-ol had green and fruity odor. In this study, the increasing quantitation of benzaldehyde with the decrease of benzyl alcohol and (E)-2-hexen-1-ol was observed in three cultivars from all PE after storage. The 'Skeena', 'Lapins', 'Sweetheart' cherries at 550–697, 502–688, and 518–640 MASL, respectively, displayed the enhanced quantitation of (E)-2-heptenal; by contrast, 'Skeena', 'Lapins', 'Sweetheart' cherries at 132–268, 117–331, and 152–365 MASL, respectively, displayed the declining quantitation of (E)-2-heptenal. Taken together, results indicated that high-elevation sites provided more benefits than low-elevation sites in producing sweet cherries with desirable flavor after storage.

-

This study's finding showed that the RR, quality attributes, antioxidants, antioxidant capacity, and aroma volatile compounds of three late-maturing sweet cherry cultivars after packaging and storage were affected by PE in the PNW regions. Additionally, 'Skeena' cherries at 268 MASL had low RR, but high levels of antioxidants and antioxidant capacity; increasing PE from 268 to 550 MASL could further maintain relatively high SSC, TA, and SSF and retain the key aroma-active compounds (including [E]-2-hexenal and [E]-2-hexen-1-ol). For 'Lapins' cherries, fruit growing at 331–502 MASL effectively reduced the deterioration in quality and antioxidant properties during storage; the cherries at 502–688 MASL had low RR with high levels of antioxidants, antioxidant capacity, and fruity aroma. For 'Sweetheart' cherries, PE at 365–518 MASL resulted in low RR with high quality, antioxidants, antioxidant capacity, and fruity aroma. These findings support optimized cultivar-elevation matching to maintain desirable postharvest quality and market value of late-maturing sweet cherries in PNW regions. In the future, a comparative research approach to revealing the effect of year-to-year climate variability on late-maturing sweet cherries at different PE might provide more information for selecting orchard sites and cultivars.

We thank the Qinghai Academy of Agricultural and Forestry Sciences Innovation Fund Project (2022-NKY-02), and Central Guidance on Local Science and Technology Development Fund (246Z6802G) for funding.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: methodology, software, formal analysis, writing − original draft, visualization: Zhi H; validation, investigation, resources, supervision: Dong Y, writing − review and editing, project administration: Zhi H, Dong Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Meteorological data in 2018 and 2019.

- Supplementary Table S2 Changes in fruit firmness (FF) of 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' sweet cherries from production elevation (PE) ranging of 117 to 697 MASL after packaging and 5 weeks of storage at 0 °C in 2018.

- Supplementary Table S3 Eigenvalues (> 1.0) and proportion of variability (> 10 %) in 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and ‘Sweetheart’ cherries from production elevation (PE) range of 117−697 meters above sea level (MASL) after packaging and and 5 weeks of storage at 0 °C by the two principle components (PCs).

- Supplementary Table S4 Component loadings for respiration rate (RR), fruit firmness (FF), soluble solids content (SSC), titratable acidity (TA), sensory score of flavor (SSF), total phenolics (TP), total flavonoids (TF), the ability to scavenge 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) of 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' cherries from production elevation (PE) ranging of 117−697 meters above sea level (MASL) after packaging (AP) and after storage (AS) from principal component (PC) analysis.

- Supplementary Table S5 Aromatic volatile compounds identified in 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' cherries.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhi H, Dong Y. 2025. Postharvest quality, physiological, and biochemical responses of three late-maturing sweet cherry cultivars to production elevation after storage. Technology in Horticulture 5: e039 doi: 10.48130/tihort-0025-0036

Postharvest quality, physiological, and biochemical responses of three late-maturing sweet cherry cultivars to production elevation after storage

- Received: 28 July 2025

- Revised: 08 October 2025

- Accepted: 31 October 2025

- Published online: 10 December 2025

Abstract: Orchard site and cultivar selection represent critical determinants in maintaining the desirable quality of sweet cherries. This study investigated the effect of production elevation (PE, 117–697 m above sea level [MASL]) on the gaseous compositions, respiration rate, quality parameters, antioxidant properties, and aromatic volatile compounds of three late-maturing cultivars ('Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart') with modified atmosphere packaging after 5 weeks of storage at 0 °C. Results showed that either low (132 and 152 MASL), or high (697 and 640 MASL) PE further reduced O2 concentration and increased CO2 concentration of 'Skeena' and 'Sweetheart' cherries; however, gaseous compositions in 'Lapins' cherries were not affected by PE. Additionally, low respiration rates (RR) were observed in the 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' cherries at 268, 502–688, and 365–518 MASL, respectively. After storage, high soluble solids content, titratable acidity, and sensory score of flavor were observed in 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' cherries at 550, 331–502, and 365 MASL, respectively. Furthermore, the 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' cherries at 268, 331–688, and 518 MASL, respectively, maintained the high antioxidants and antioxidant capacities after packaging and storage. Compared to after packaging and low PE, the 'Skeena', 'Lapins', and 'Sweetheart' cherries at 550–697, 502–688, and 518–640 MASL, respectively, retained more fruity aroma (including acetaldehyde, 3-methyl-3-buten-1-ol, 2-hexen-1-ol, hexanol, and butyl butyrate) after storage. In conclusion, PE at 268–550 and 365–518 MASL was suitable for growing 'Skeena' and 'Sweetheart' cherries, respectively, whereas 'Lapins' cherries demonstrated superior adaptation to > 502 MASL with low RR and high antioxidant properties and flavor retention.