-

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is one of the primary staple crops for human consumption, ranked third in global importance after rice and wheat[1,2]. However, the yield and quality of potatoes are significantly affected by various pests and diseases during production, leading to substantial economic losses for farmers and businesses[3]. Among these diseases, blackleg, which is caused by pathogenic bacteria, can lead to the wilting and death of seedlings, with losses ranging from 3% to 68%, averaging around 15%[4]. Additionally, tuber losses can sometimes be as high as 30% to 50%. The infection can persist in tubers during storage, especially in those that have been mechanically injured. In favorable conditions for the pathogen's growth, these tubers may quickly become soft and rot, producing a foul smell[5,6]. Rotten tubers can infect healthy ones, leading to increased damage and a decline in the quality of seed potato, which in turn affects future potato yields[7,8].

The most common bacterial species responsible for blackleg disease belong to the genus Pectobacterium, particularly the carotovora subgroup, which includes Pectobacterium carotovora subsp. carotovora (Pcc) (formerly known as Erwinia carotovora subsp. Carotovora), Pectobacterium atrosepticum (Pca) (formerly Erwinia carotovora subsp. atroseptica), and Dickeya spp. (formerly Erwinia chrysanthemi)[9,10]. They produce various cell wall-degrading enzymes, which play crucial roles in the degradation of the plant cell wall, resulting in the characteristic soft-rot symptoms. Some of these enzymes are secreted, while others remain in the periplasm[11]. Pectate lyase is one critical enzyme for the infection of plants, thus serving as a primary factor in their pathogenicity[12].

Once infection occurs in the field, blackleg disease is exceedingly hard to control. The pathogen spreads by soil and water, posing risks to subsequent crops[13]. To date, resistant varieties are considered the most effective strategy for managing bacterial diseases. Although the cultivation of disease-free potatoes is an effective method for controlling potato blackleg, losses still occur even when these potatoes are used. In practice, different potato varieties exhibit varying susceptibility to blackleg pathogens; thus, selecting resistant potato varieties can significantly mitigate the economic losses associated with this disease.

To address these challenges, this study evaluated the disease resistance of 12 different potato varieties, screening for resistant and susceptible varieties while assessing various antioxidant enzyme activities, H2O2 levels, MDA, and Pro content across different varieties. By analyzing the correlation between physiological indices and disease resistance, this research aims to provide a scientific basis for breeding potatoes resistant to blackleg disease and developing improved field production strategies.

-

The tested potato varieties include Zhengshu No. 8, Zhongshu 170, 41-1×15FM11-1, 69-3×16EM02-3, Jinguan, Hongdao, Houma, Huashu No. 2, Zhongshu 316, Minshu, No. 1, Zhongshu 164, and Beifang 001, which were provided by the Vegetable Research Institute of Henan Province, Henan, China (Table 1). The tested strain, Pectobacterium carotovora, was provided by the College of Plant Protection, Henan Agricultural University, Henan, China. Zhongshu 316 and Zhongshu 317 were identified as resistant varieties based on field phenotypic evaluation.

Table 1. Potato varieties used in the study.

Number Variety Number Variety 1 Zhengshu No. 8 7 Zhongshu 170 2 41-1×15FM11-1 8 69-3×16EM02-3 3 Jinguan 9 Hongdao 4 Houma 10 Huashu No. 2 5 Zhongshu 316 11 Minshu No.1 6 Zhongshu 164 12 Beifang 001 Preparation of bacterial suspension

-

The potato blackleg pathogen, retrieved from a −80 °C freezer, was rejuvenated for 48 h on TSA medium at 28 °C. Single colonies of the strain were picked and placed in 100 mL of sterilized TSB medium, and incubated for 24 h under the following conditions: 180 r/min, 28 °C. The bacterial suspension was subsequently modified to achieve a concentration of 103 cfu/mL.

Infection of Pectobacterium carotovora in potato varieties in vitro

-

The method for in vitro petiole inoculation with blackleg pathogens was adapted from other articles with appropriate modifications[14,15]. Petiole samples were selected from robust potato plants of different varieties grown in the field. The petioles were uniformly cut to a height of 6.5 cm, and inserted into square dry floral foam blocks (5.8 cm length and 0.5 cm thickness). Three independent biological replicates were set up for each potato variety. In each biological replicate, three parallel culture flasks (with five petioles per flask) were arranged for each variety as technical replicates. The experiment was repeated three times. In square tissue culture bottles (60 mm × 60 mm × 90 mm), 40 mL bacterial suspension was added. For the control group, 40 mL of MES solution without bacteria was used. They were cultivated under a 16-h light/8-h dark cycle at 25 °C. The infection status of the pathogen was observed 36 h post-inoculation (hpi).

Assessment of resistance level in different varieties

-

The assessment of resistance level under in vitro conditions involved observing and recording the disease status of potato petioles in tissue culture bottles infected with the potato blackleg at 36 hpi. The height of soft rot and decay in the petioles was measured, and cross-sections of the petioles were taken 3 cm from the cut ends to examine any changes in vascular bundles under a light microscope. The disease index was calculated to determine resistance levels. The disease severity was graded according to the standards outlined in Table 2.

Table 2. Standardized assessment of disease grade.

Mean of petiole lesion height (cm) Disease grade 0~0.5 0 0.5~1 1 1~2 2 2~4 3 4~6.5 4 And the disease index was calculated based on these severity grades. The resistance levels of the potato varieties were classified as follows: high resistance (R) for disease index 0.2 ≤ index < 0.4; moderate resistance (MR) for 0.4 < index ≤ 0.6; moderate susceptibility (MS) for 0.6 < index ≤ 0.8; and high susceptibility (S) for index > 0.8. The formula for calculating the disease index is as follows:

$ \mathrm{D}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{e}\; \mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{x}=\dfrac{\sum_{ }^{ }(\mathrm{N}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{m}\mathrm{b}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{r}\; \mathrm{o}\mathrm{f}\; \mathrm{s}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{c}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{p}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{b}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{e}\; \mathrm{p}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{s}\times\mathrm{ }\mathrm{R}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{n}\mathrm{c}\mathrm{e}\; \mathrm{l}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{v}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{s})}{\mathrm{T\mathrm{o}}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}\; \mathrm{p}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{s}\times\mathrm{H}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{g}\mathrm{h}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{t}\; \mathrm{l}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{v}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{l}\; (4)} $ Determination of SOD activity

-

The activity of SOD in the petioles infected at 0 and 36 hpi were tested using nitro blue tetrazolium assay[16,17]. Petiole tissue (0.5 g) was blended with 5 mL of pre-chilled phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) extraction buffer (0.05 M, pH 7.8) on ice. The mixture was subjected to centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatant was collected as the enzyme extract. The reaction was initiated by exposing the mixture to 4,000 lux light for 15 min and was terminated immediately by transferring the tubes to the dark. The optical density (OD) was measured at 560 nm using a spectrophotometer. A blank control was used by replacing the enzyme extract with 30 μL of PBS (0.05 M, pH 7.8). SOD activity is calculated as follows:

$ \mathrm{SOD(Ug}^{{-1}}\, \mathrm{FW)=[(A}_ { \mathrm{ck}} \mathrm{-A}_{ \mathrm{E}} \mathrm{)\times V_{t}]/(1/2A}_{ \mathrm{ck}} \times \mathrm{ W\times V_{s})} $ Ack is the absorbance of the control tube. AE indicates the absorbance of the sample tube. Vt refers to the volume of the sample. Vs represents the volume of enzyme solution utilized. W is the fresh weight of the sample (g).

Determination of POD activity

-

The activity of peroxidase (POD) of the petioles infected by the pathogen at 0 and 36 hpi was measured. POD activity was determined using the guaiacol method as follows[18,19]: Mix 3 ml of the POD reaction mixture with 30 μl of the enzyme extract in a test tube, and 30 μl PBS (0.2 M, pH 6) was used as a blank control. Measure the absorbance changes at 470 nm over 4 min, recording every minute. The POD activity is calculated as:

$ \mathrm{POD=((A}_{\mathrm{ck}}\mathrm{-A}_{\mathrm{E}}\mathrm{)}\times\mathit{\mathit{\mathrm{\mathit{\mathrm{V}}_{\mathit{\mathrm{t}}}}}}\mathrm{)/(}\mathit{\mathrm{W}}\times\mathrm{\mathit{\mathrm{V}}_{\mathit{\mathrm{s}}}}\times\mathrm{0.01}\times\mathit{\mathrm{t})(}\mathrm{U/g/min)} $ The meanings of these terms (Ack, AE, Vt, W, Vs) are the same as those used when measuring SOD activity above, t is the reaction time (min).

Determination of CAT activity

-

Plant materials were the same as above, and the activity of catalase (CAT) in the petioles infected by the pathogen at 0 and 36 hpi were measured[20,21]. CAT activity is determined using the H2O2 method as follows: Mix 3 ml of the CAT reaction mixture with 100 μl of the enzyme extract, measure the absorbance at 240 nm, and then measure again after 40 s. The CAT activity (μg−1 min) is calculated as:

$ \rm CAT\;({\text μ}g^{-1} \;min)=[(A_{{ck}} -A_{E} )\times V_{t}]/(W\times V_{s}\times 0.01\times t) $ The meanings of these terms (Ack, AE, Vt, W, Vs) are the same as those used when measuring POD activity above.

Measurement of APX activity

-

The ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity was determined using the H2O2 method[22,23]. A volume of 0.10 ml of enzyme solution (extracted using the same method as for SOD) was added to the APX reaction mixture. The reaction mixture without H2O2 served as the control for zero adjustment. The optical density (OD290) was measured (40 s per reading, with two consecutive readings), and the APX activity was calculated: a decrease of 0.01 in OD per minute was considered one unit of enzyme activity (u);

$ \rm APX\;({\text μ}g^{ -1}\; min)=[(A_{ ck} -A_ {E} )\times V_{t}]/(W\times V_{s}\times 0.01\times t) $ The calculation method and formula for this enzyme activity are the same as those used for POD.

Measurement of malondialdehyde (MDA) content

-

To measure the MDA content, 1.5 mL of the enzyme solution (extracted using the same method as for POD) was combined with 2.5 mL of 0.5% thiobarbituric acid (TBA)[24]. Phosphate buffer (0.05 M, pH 7.8) was used as a control. The mixtures were shaken and then incubated in a boiling water bath for 20 min. After cooling, the samples were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. Absorbance values were tested at wavelengths of 600, 532, and 450 nm.

MDA concentration C (μM) is calculated using the formula:

$ \mathrm{C=6.45\times (OD}_{ \mathrm{532}} \mathrm{-OD}_{ \mathrm{600}} \mathrm{)-0.56\times OD}_{ \mathrm{450}} $ where, MDA content (µmol/g FW) = C × V/W, V represents the volume of extraction solution (mL); W means the fresh weight of the sample (g).

Data analysis

-

Data from three independent biological replicates for each experiment were analyzed using SPSS 17.0 software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data analysis was then performed using One-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons. Tukey's HSD test (p < 0.05) was used to determine the significant differences between different treatments.

-

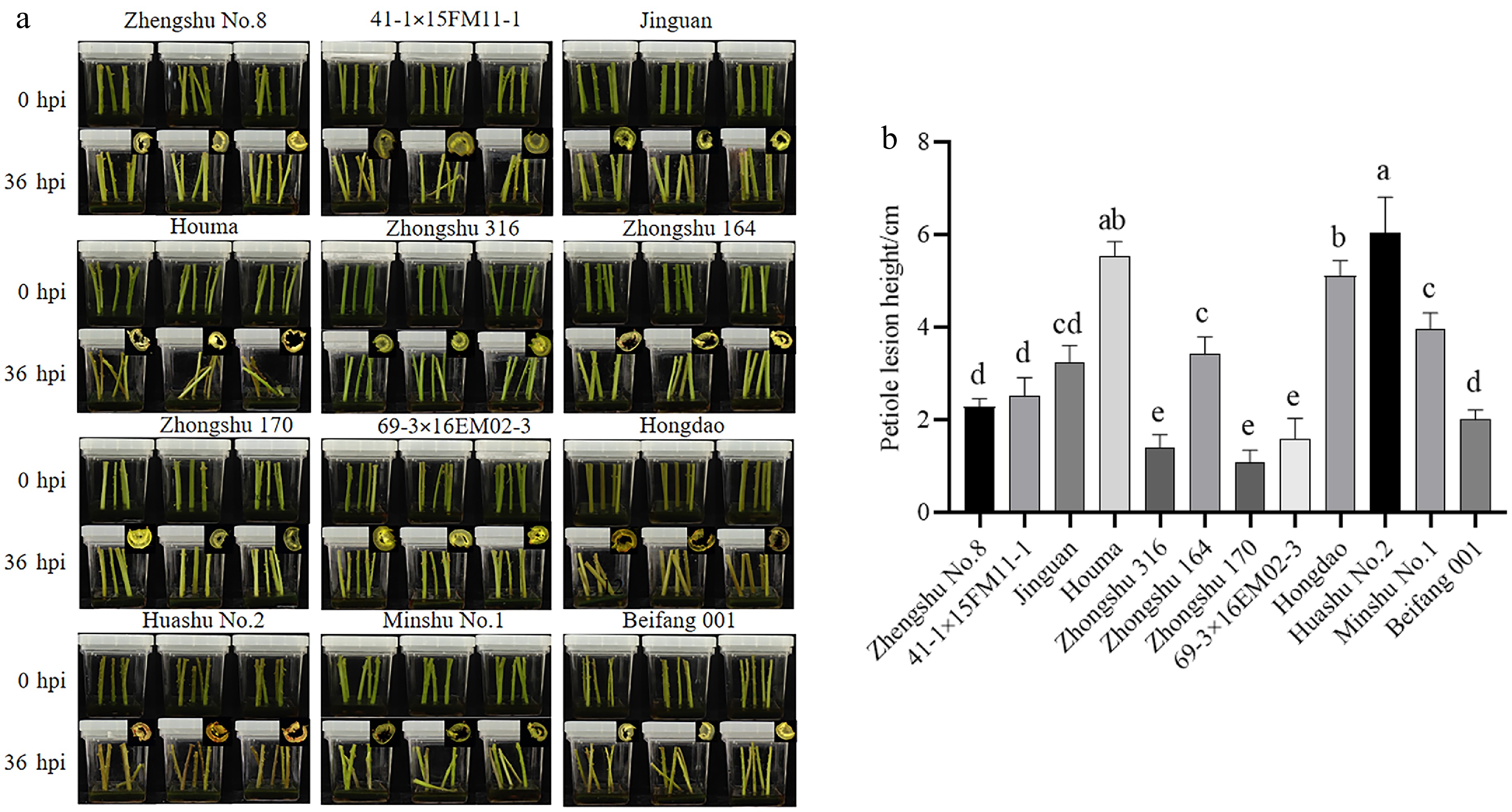

As shown in Fig. 1a and b, the petioles of the resistant potato varieties largely remained upright at 36 hpi compared to 0 hpi, and the lesion height was less than 2 cm, such as Zhongshu 170 and Zhongshu 316. While the petioles of the susceptible varieties show significant bending, the lesion height can reach about 6 cm, including Hongdao, Houma, and Huashu No. 2 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Evaluation of resistance of different potato varieties to Pectobacterium carotovorum infection. (a) Phenotypes of different potato varieties at 0 and 36 h post-infection with blackleg disease. (b) Lesion height of petioles on different varieties. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences among varieties (p < 0.05, One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's HSD test). Error bars represent standard error (SE). n = 3 (biological replicates); each biological replicate contained three technical replicates (culture flasks, five petioles per flask), and data were computed as the average of technical replicates across three biological replicates.

Based on the lesion height of the stem segments, disease grade, and disease index, the resistance levels of the different varieties were classified. As shown in Table 3, the varieties exhibiting high resistance (R) to blackleg disease included Zhongshu 170 and Zhongshu 316, with decay degrees of rot ranging from 1.4 to 1.1 cm, respectively. The potato varieties classified as moderate resistance (MR) included Zhengshu 8, 41-1×15FM11-1, 69-3×16EM02-3, and Beifang 001. Varieties displaying moderate susceptibility (MS) include Jinguan, Minshu No.1, and Zhongshu 164. The high susceptibility (S) varieties were Hongdao, Houma, and Huashu No. 2.

Table 3. Investigation on infection of petiole infected by blackleg.

Materials Petiole lesion

height (cm)Disease

gradeDisease

indexGrade Zhengshu No.8 2.3d 3 0.65 MR 41-1×15FM11-1 2.5d 3 0.58 MR Jinguan 3.2cd 3 0.73 MS Houma 5.5ab 4 0.85 S Zhongshu 316 1.4e 2 0.4 R Zhongshu 164 3.4c 3 0.72 MS Zhongshu 170 1.1e 2 0.38 R 69-3×16EM02-3 1.6e 2 0.45 MR Hongdao 5.1b 4 0.96 S Huashu No.2 6.0a 4 0.96 S Minshu No.1 4.0c 4 0.8 MS Beifang 001 2.0d 2 0.46 MR Variations in MDA, H2O2, and pro content among different potato varieties

-

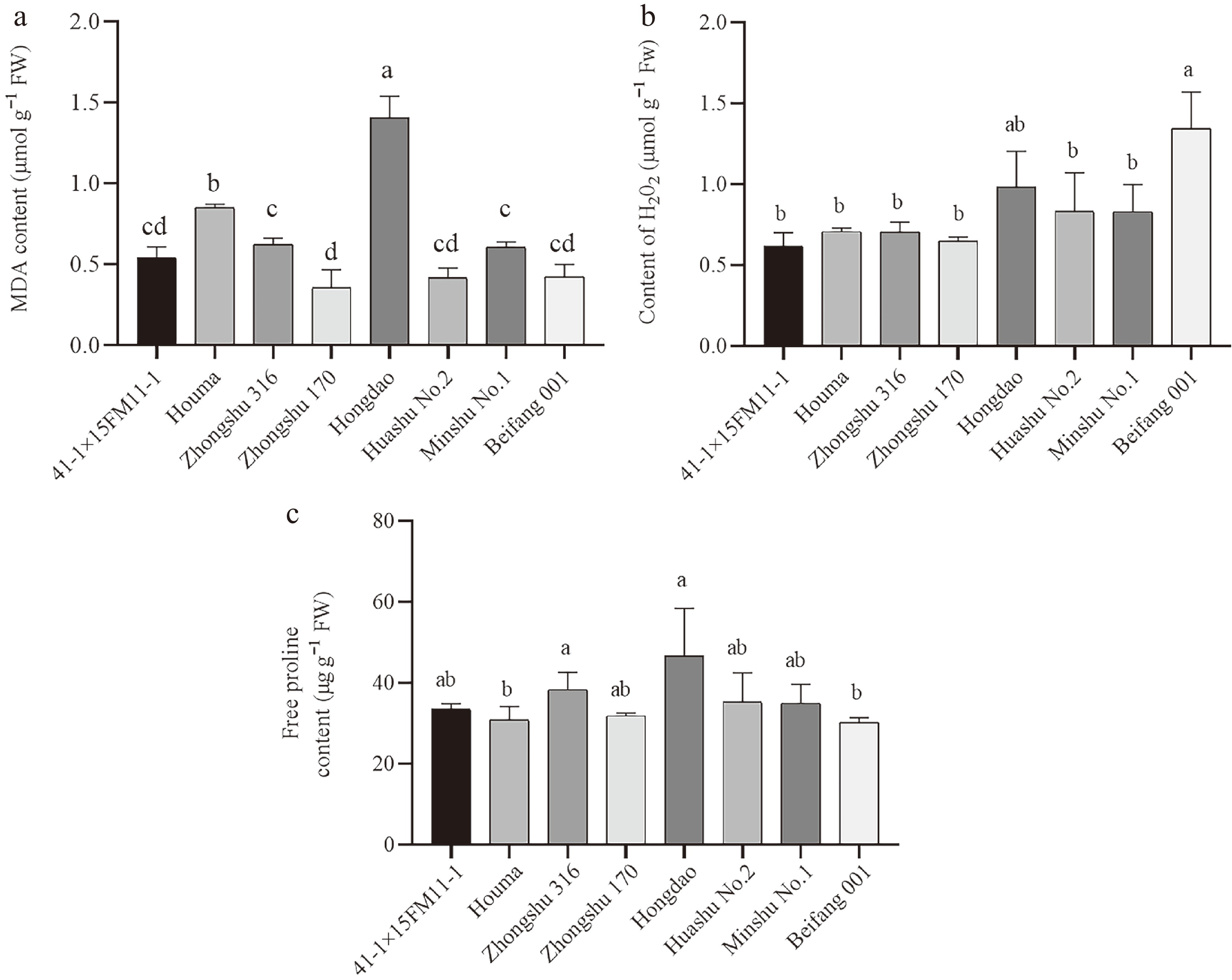

To further investigate the differences in resistance among various potato varieties to blackleg disease, samples were analyzed at 36 hpi with the blackleg pathogen for MDA, H2O2, and Pro measurement (Fig. 2). As depicted in Fig. 2a, the Hongdao variety, classified as highly susceptible to blackleg, exhibited the highest MDA content at 1.41 μmol/g−1 FW, significantly surpassing that of other varieties. This was followed by Houma (S), Zhongshu 316 (R), and Minshu No. 1 (MR). The lowest MDA content was observed in Zhongshu 170, which is considered R. Figure 2b illustrates that Beifang 001 (MR) had the highest H2O2 content, followed by Hongdao (S), Huashu No. 2 (S), and Minshu No. 1 (MR). The lowest H2O2 levels were recorded in Zhongshu 170 (R) and 41-1×15FM11-1 (MR). In Fig. 2c, it is evident that Hongdao (S) also had the highest Pro content, followed by Zhongshu 170 (R), Huashu No. 2 (S), and Minshu No. 1 (MS). Conversely, Houma (S) and Beifang 001 (MR) exhibited the lowest Pro levels.

Figure 2.

Changes of (a) MDA, (b) H2O2, and (c) proline content of different potato varieties after blackleg disease infection. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences among varieties (p < 0.05, One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's HSD test). Error bars represent standard error (SE). n = 3 (biological replicates); each biological replicate contained three technical replicates (culture flasks, five petioles per flask), and data were computed as the average of technical replicates across three biological replicates.

Changes in potato varieties on antioxidant enzyme activity on blackleg disease inoculation

-

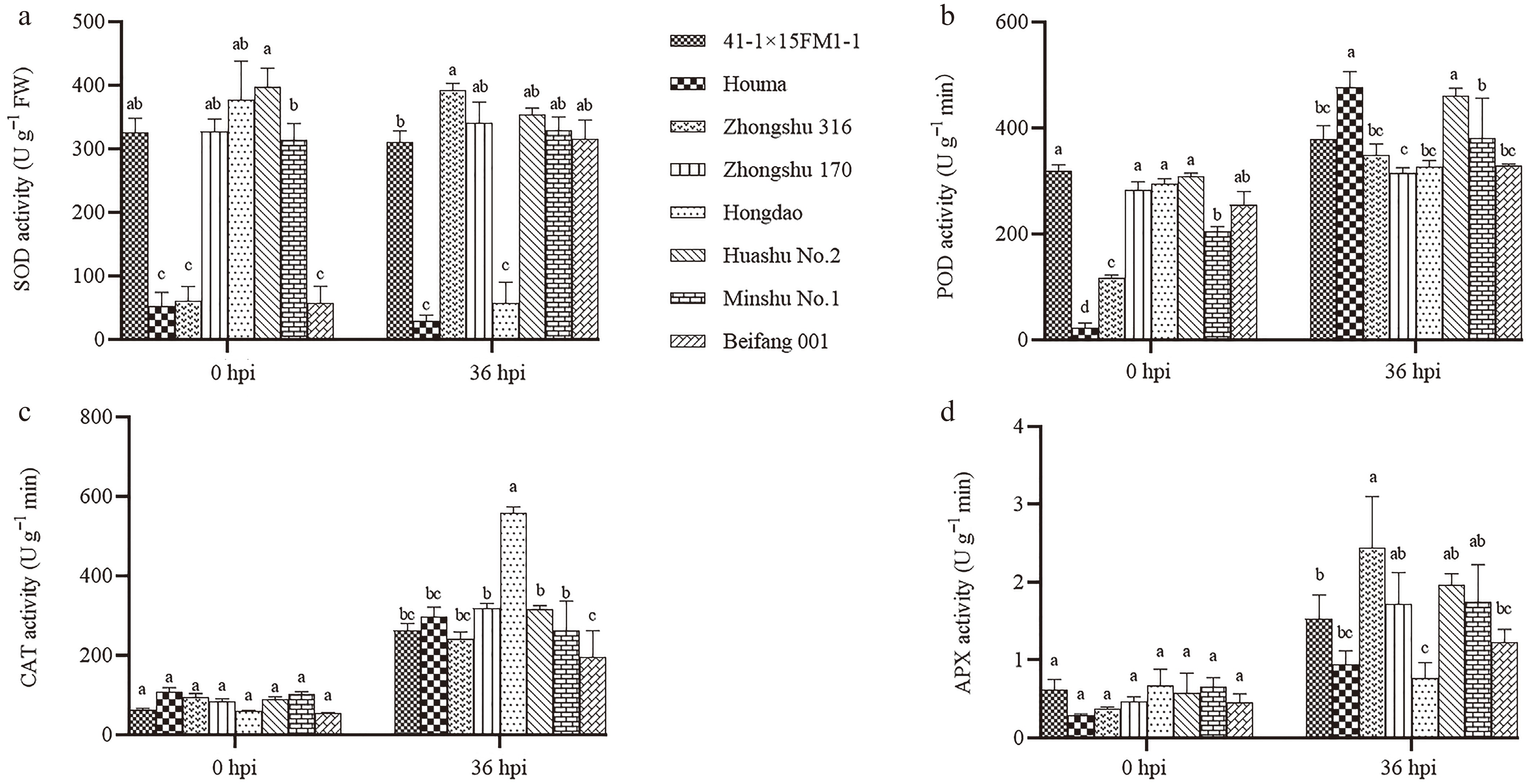

To assess the impact of blackleg inoculation on various potato varieties, samples were taken for the measurement of SOD, CAT, POD, and APX activities before and after pathogen exposure (Fig. 3). As shown in Fig. 3a, prior to inoculation, Huashu No. 2 (S) exhibited the highest SOD activity, which significantly decreased at 36 hpi. Hongdao (S) followed closely, presenting an initial SOD activity around 400 U/g−1 FW, which sharply declined to 50 U/g−1 FW at 36 hpi. Other varieties, such as 41-1×15FM11-1 (MR) and Minshu No. 1 (MS), also displayed relatively high SOD activity before inoculation, with minimal changes in their levels post-infection. In contrast, Beifang 001 (MR), Houma (S), and Zhongshu 316 (R) showed the lowest SOD activity prior to pathogen exposure. Notably, SOD activity significantly increased in Beifang 001 (MR) and Zhongshu 170 (R) at 36 hpi, while Houma (S) maintained consistently low levels.

Figure 3.

Changes of antioxidant enzyme activity on blackleg infection. (a) Changes in SOD enzyme activity at 0 and 36 h post-infection with blackleg disease. (b) Changes in POD enzyme activity. (c) Changes in CAT enzyme activity. (d) Changes in APX enzyme activity. Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences among varieties (p < 0.05, One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's HSD test). Error bars represent standard error (SE). n = 3 (biological replicates); each biological replicate contained three technical replicates (culture flasks, five petioles per flask), and data were computed as the average of technical replicates across three biological replicates.

Upon examining POD activity (Fig. 3b), it was observed that Houma (S) had the lowest POD activity before pathogen exposure. However, at 36 hpi, its POD activity surged to the highest level among all varieties. Zhongshu 316 (R), which also exhibited low POD activity before inoculation, showed a significant increase in activity following pathogen exposure. All potato varieties demonstrated varying degrees of increased POD activity after inoculation, with Houma (S), Huashu No. 2 (S), and Minshu No. 1 (MS) showing the highest level.

Figure 3c illustrates that there were no significant differences in CAT activity among the various potato varieties prior to inoculation, with overall low activity levels. However, CAT activity significantly increased across all varieties after inoculation, with Hongdao (S) exhibiting notably higher CAT activity than the others, marking the greatest increase compared to pre-inoculation levels. This was followed by Zhongshu 170 (R) and Huashu No. 2 (S), both of which also demonstrated elevated CAT activity after pathogen exposure.

As depicted in Fig. 3d, APX activity in different potato varieties increased following pathogen inoculation. The most significant change was observed in Zhongshu 316 (R), which had the highest APX activity at 36 hpi. Huashu No. 2 (S) and Minshu No. 1 (MS) followed with elevated APX activity levels.

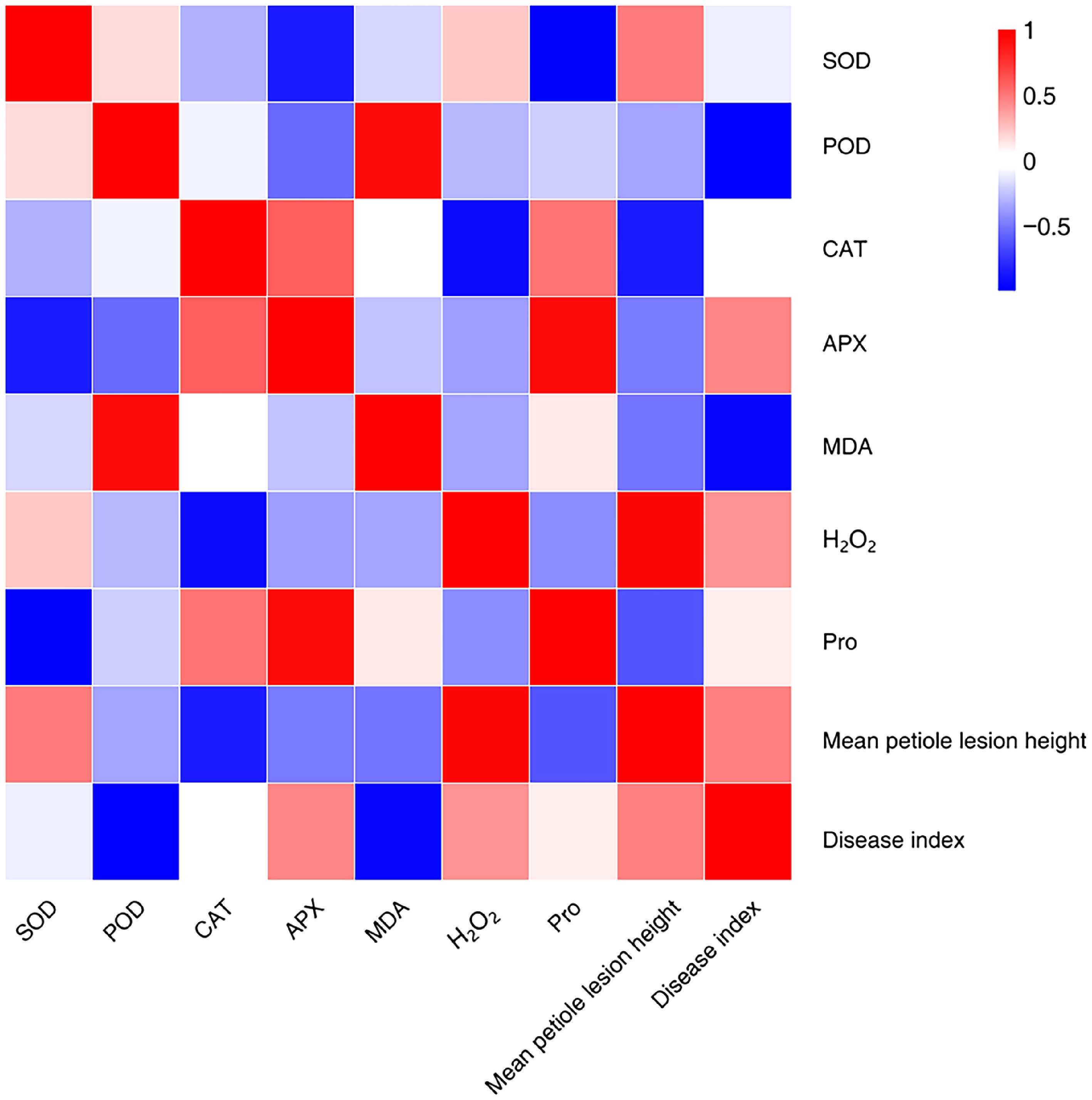

Correlation analysis between disease resistance and physiological indicators in different potato varieties

-

To explore the relationship between physiological indicators and disease resistance in various potato varieties, a correlation analysis was conducted (Fig. 4). In resistant varieties, the disease index exhibited a strong positive correlation with the severity of symptoms; as resistance decreased, the severity of stem rot increased, leading to a higher disease index. Some physiological parameters, including SOD and POD activity, displayed negative correlations with the disease index, suggesting a positive association with resistance; while H2O2 level displayed positive correlations with the disease index, suggesting a negative association with resistance. Furthermore, H2O2 level were positively correlated with SOD activity while showing negative correlations with POD, CAT, and APX.

-

Potato, as a staple food crop supporting billions of people worldwide, faces persistent threats from blackleg. It is a destructive bacterial disease capable of triggering extensive yield losses and post-harvest rot. The identification of blackleg resistance across diverse potato cultivars holds paramount significance for global potato production and agricultural sustainability. Given the difficulty in eradicating these pathogens once established in soil or tubers, the selection of disease-resistant germplasm resources is fundamental to the work of resistance breeding. In the present study, field-grown potato plants were utilized, and an ex vitro petiole inoculation technique employed to screen and evaluate the resistance of potato varieties to blackleg disease. This method is efficient and facilitates the provision of parental materials for disease-resistant breeding, thereby enriching the available disease-resistant resources. Using this technique, 12 potato varieties were screened and two varieties identified, Zhongshu 170 and Zhongshu 316, which were demonstrated resistant to Pectobacterium carotovorum. Additionally, susceptible varieties such as Hongdao, Houma[25], and Huashu No. 2 were noted, which provide a theoretical basis for subsequent field evaluations of resistant varieties.

Lipid peroxidation is widely recognized as a reliable marker for evaluating oxidative damage in plants, as it directly reflects the extent of membrane impairment caused by stress[26,27]. This process can be quantified by measuring MDA levels; in the present study, significant differences in MDA content were observed among potato cultivars after blackleg pathogen infection. Hongdao (S) exhibited the highest MDA content, which was markedly elevated compared to other tested varieties. In contrast, the lowest MDA content was detected in Zhongshu 170 (R), a finding that aligns with its strong resistance and minimal oxidative damage. In the context of potato blackleg resistance identification, the determination of MDA content and Pro (a key osmolyte and antioxidant involved in plant stress tolerance) content is mutually complementary. They reveal the differential levels of oxidative damage and stress adaptation capacity among potato cultivars, thereby providing a comprehensive biochemical basis for evaluating their resistance to blackleg pathogens. Turning to Pro content, the present results show distinct varietal differences. Hongdao (S) had the highest Pro content, followed by Zhongshu 170 (R), Huashu No. 2 (S), and Minshu No. 1 (MS). Conversely, Houma (S) and Beifang 001 (MR) exhibited the lowest Pro levels. The high Pro content in Hongdao (S) may reflect a heightened but ineffective stress response: while Pro typically accumulates to mitigate osmotic stress and scavenge ROS, its overaccumulation in this susceptible cultivar might not be sufficient to counteract severe oxidative damage induced by blackleg infection. In contrast, the moderate Pro levels in resistant (Zhongshu 170), and low Pro levels in moderately resistant (Beifang 001) cultivars could indicate a more balanced stress adaptation—one that supports defense without excessive metabolic expenditure, further contributing to their resistance against blackleg.

ROS are universally generated in plants during infections by diverse pathogens, including those induced by blackleg pathogens in potato. ROS are crucial for plant defense, acting directly as an antimicrobial agent, aiding in the lignification of cells and the cross-linking of lignified structures with hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins, while also acting as a secondary messenger to modulate the expression of resistance genes[28,29]. In healthy states, plants maintain a dynamic equilibrium between the generation and removal of ROS[30]. However, upon invasion by blackleg pathogens, this balance is disrupted, leading to the rapid accumulation of ROS[31]. Elevated levels of ROS can interact with various cellular components, including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, resulting in lipid peroxidation, membrane damage, and the deactivation of essential enzymes, ultimately producing toxic effects[32−34]. Among ROS, H2O2 (1 ms half-life) is more stable than superoxide (O2–) and hydroxyl radicals (•OH) (2–4 µs)[29]. In the present study, significant differences in H2O2 accumulation were observed among the tested potato cultivars after blackleg pathogen inoculation. Beifang 001(MR) exhibited the highest levels of H2O2, followed by Hongdao (S), Huashu No. 2 (S), and Minshu No. 1 (MS). Conversely, the lowest H2O2 levels were observed in Zhongshu 170 (R) and 41-1×15FM11-1 (MR). Based on these results, a dual physiological mechanism underlying blackleg resistance in potato is proposed: resistant cultivars possess both an enhanced capacity to generate H2O2 (to initiate early defense responses), and a robust ability to scavenge excess H2O2 (to mitigate oxidative damage)[35]. In contrast, susceptible cultivars show a deficiency in H2O2 detoxification systems, leading to the prolonged accumulation of H2O2 beyond the threshold required for beneficial defense signaling. This physiological limitation likely contributes to the development of severe blackleg symptoms, as persistent oxidative stress amplifies cellular damage and impairs the host's ability to contain pathogen spread.

To mitigate oxidative damage induced by excessive ROS, plants deploy a coordinated defense system consisting of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants. Among the enzymatic components, SOD, CAT, POD, and APX are the primary enzymes responsible for ROS scavenging, with SOD playing a pivotal upstream role in this detoxification pathway[36,37]. Specifically, SOD acts as the first line of defense by catalyzing the conversion of highly reactive O2− into H2O2, this is a reaction that not only reduces the toxicity of O2− but also produces H2O2, which can be further scavenged by CAT, POD, or APX to prevent oxidative stress. In this study, prior to pathogen inoculation, the two S cultivars (Huashu No. 2 and Hongdao) exhibited the highest baseline SOD activity. However, at 36 hpi, their SOD activity declined significantly. This sharp decrease likely reflects an overwhelmed ROS detoxification system, as blackleg pathogens proliferate, the rapid surge in ROS production outpaces the capacity of SOD (and downstream enzymes) to scavenge free radicals, leading to a collapse in SOD-mediated defense and subsequent accumulation of oxidative damage, which is consistent with their H2O2 content. In stark contrast, Beifang 001 (MR) and Zhongshu 316 (R) displayed the lowest baseline SOD activity before pathogen exposure, but their SOD activity increased markedly at 36 hpi. This induced SOD activation is a hallmark of effective resistance: rather than maintaining high constitutive SOD levels (which may incur unnecessary metabolic costs), these resistant cultivars upregulate SOD expression to limit ROS-induced membrane damage (as discussed in the MDA and H2O2 section), and supporting a robust defense response.

POD is a multifunctional enzyme regulating plant processes like metabolism, cell wall lignification, and pathogen defense. For resistance, it strengthens cell walls via lignin monomer polymerization, and promotes antimicrobial phytoalexin synthesis, while synergizing with cytochrome P450 to form antibacterial terpenoid polymers[38]. In the present study, Zhongshu 316 (R) and Zhongshu 170 (R) had low baseline POD activity but saw a dramatic surge to the highest levels at 36 hpi post-blackleg inoculation. All cultivars showed increases in POD activity, but resistant ones had stronger, more targeted activation. This aligns with other plant-pathogen systems, and POD overexpression boosts potato late blight resistance[39]. It is suspected that POD surge in resistant cultivars scavenges excess H2O2 (preventing oxidative damage) and accelerates lignification to block pathogen spread.

CAT and APX are core antioxidant enzymes that scavenge hydrogen peroxide H2O2[40]. In the present study on potato blackleg resistance, the dynamics of CAT and APX activities further supported their defensive roles. Prior to inoculation with the blackleg pathogen, there were no significant differences in CAT or APX activities across all tested potato varieties, and overall activity levels were relatively low—suggesting minimal constitutive expression of these enzymes in unstressed conditions. However, post-inoculation, CAT activity increased significantly in all varieties. Notably, the susceptible (S) cultivar Hongdao exhibited the highest CAT activity and the most substantial pre- to post-inoculation increment, indicating a strong stress response; yet this elevated CAT activity was not sufficient to confer resistance, likely because it failed to counteract the excessive ROS production or other pathogenic effects of the blackleg pathogen. The role of APX in disease resistance is further validated by previous studies, such as OsAPX8 and OsAPX1[41,42]. For potato blackleg resistance, these findings collectively imply that while both CAT and APX are induced in response to pathogen attack, the timing, magnitude, and coordination of their activation (rather than mere elevation) determine resistance. Resistant potato varieties likely exhibit more balanced CAT/APX activation to regulate ROS levels (supporting signaling and avoiding damage), whereas susceptible varieties (like Hongdao) may have uncoordinated or insufficient APX induction—limiting their ability to sustain ROS detoxification and cell wall reinforcement, ultimately leading to severe disease symptoms.

-

In summary, this study employed an in vitro petiole inoculation method to screen and evaluate resistant potato varieties against blackleg disease. The results demonstrated that Zhongshu 170 and Zhongshu 316 are resistant varieties, while Hongdao, Houma, and Huashu No. 2 are susceptible. Furthermore, significant differences in antioxidant enzyme activity and physiological parameters were observed among the various potato varieties in response to blackleg pathogen infection. Additionally, variations in the correlation between physiological indicators and disease resistance were noted between resistant varieties. This research provides a crucial theoretical foundation for disease-resistant breeding in potatoes, aiding in the identification of varieties with high resistance, and establishing a basis for future field evaluations and breeding efforts. Further studies should focus on elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying disease resistance genes in potatoes and how genetic improvements can enhance the overall disease resistance of potato varieties.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32301848, 32172575, and 31801420).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Meng G, Sun K, Zhang X; materials and data collection: Ye Q, Hou Y, Song C, Ge T, Liu P, Wang S, Yang W, Pang G; analysis and interpretation of results, draft manuscript preparation: Ye Q, Meng G. Review and editing: Sun K, Zhang X, Jia Z, Hu J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Geng Meng, Qianwei Ye

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Meng G, Ye Q, Hou Y, Song C, Ge T, et al. 2026. Exploring resistance in potatoes to combat blackleg disease. Technology in Horticulture 6: e001 doi: 10.48130/tihort-0025-0034

Exploring resistance in potatoes to combat blackleg disease

- Received: 03 July 2025

- Revised: 30 August 2025

- Accepted: 18 September 2025

- Published online: 21 January 2026

Abstract: Blackleg, a devastating bacterial disease primarily caused by Pectobacterium carotovorum, poses a considerable threat to potato production. Accordingly, it is critical for the development of resistant cultivars to elucidate the physiological bases of resistance. Here, the resistance of 12 potato cultivars to blackleg were evaluated, identifying two highly resistant cultivars, and three susceptible cultivars. High resistant varieties Zhongshu 170 and Zhongshu 316 exhibited significantly lower decay levels compared to susceptible varieties, including Houma, Hongdao, and Huashu No. 2. This study also investigates the variations in malondialdehyde (MDA), proline (Pro), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content among potato varieties with different blackleg resistance levels. The results indicate that high susceptibility is associated with elevated MDA and Pro, consistent with severe membrane lipid peroxidation. By contrast, H2O2 levels did not align strictly with resistance rankings, suggesting genotype-specific ROS signaling and scavenging strategies. Detection of antioxidant enzyme activities after pathogen inoculation showed that the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and peroxidase (POD) in resistant varieties increased sharply post-inoculation. Additionally, catalase (CAT) and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activities increased across all varieties after infection, with resistant types showing higher levels. Finally, the correlation analysis revealed a complex relationship between these indicators and disease resistance. Overall, this provides a scientific foundation for breeding programs aimed at developing potatoes with improved resistance to blackleg disease, ultimately enhancing agricultural strategies and production efficiency.

-

Key words:

- Pectobacterium carotovorum /

- Resistant /

- ROS /

- Antioxidant enzyme /

- Potato /

- Blackleg.