-

Fire blight, a highly destructive bacterial disease, is caused by Erwinia amylovora[1]. It primarily harms pome fruit trees of Rosaceous. It infects the plants through the nectaries of the flowers, and also infects host's tissues through wounds. The pathogen multiplies in large quantities in the vascular bundles after infecting the tree, and then migrates inside the tree, causing necrotic lesions on flowers, leaves, fruits, shoots, and roots. The physiological functions of the plants are impaired, and eventually, the entire plant dies as the disease progresses. It causes severe economic losses to agricultural production[2]. Fire blight was classified as a major quarantine disease in the world, as well as being categorized as a Class I crop disease in China[3].

Fire blight was first reported in North America in 1780. Currently, it has spread to over 60 regions around the world, including many countries and regions in North America, Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, Oceania, and Asia[4]. In 2016, the fire blight spread to places such as Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan in Central Asia, and South Korea in East Asia[5−7]. The disease was first reported in Yili Prefecture, Xinjiang (China), in May 2016[8]. As of 2023, fire blight spread to both Xinjiang and Gansu (China)[9]. Fire blight is advancing in China, and seriously endangers the production of apples, therefore, the evaluation and screening of resistant Malus resources to fire blight is crucial.

The methods for the evaluation of fire blight resistance mainly include field natural infection and artificial inoculation. Field natural infection is a more direct method; it reliably quantifies field resistance in the actual environment by cultivating test varieties in high-risk infection zones and monitoring natural infection progression. However, this method is greatly influenced by environmental conditions, with a high uncertainty in the occurrence of diseases and a long evaluation period, making it difficult to obtain reliable results in a short time. Artificial inoculation offers advantages such as simple operation, short cycle, and environmental independence. Common methods include the syringe inoculation of detached plant organs such as leaves, immature fruits, and young shoots[10], the soil inoculation of pot-grown seedlings with injured roots[11], as well as the spray inoculation method[12]. These methods had high repeatability and accuracy. Moreover, they were suitable for large-scale screening. However, the resistance performance under conditions in vitro may differ from the actual situation in the field, and cannot fully reflect the overall resistance level of the plants.

In practical applications, several methods should be combined to obtain more comprehensive and accurate results of resistance evaluation. Therefore, how to improve the accuracy of detection is an urgent problem to be solved in the evaluation and screening of fire blight resistance in Malus plants. In this study, the toothpick puncture method was adopted. The identification results obtained from three inoculation methods, namely, young leaves, young shoots in vitro, and young plants in vivo, were compared and analyzed. Nineteen Malus plants were evaluated for resistance to fire blight, and resistant resources were screened out to provide materials for fire blight-resistant breeding and related resistance gene mining.

-

Nineteen types of Malus plants were obtained from the National Pear and Apple Germplasm Repository (Xingcheng, China) (Table 1). In May 2019, the plants were grafted onto 'Malus baccata (L.) Borkh.' and were sent to Korla, Xinjiang, for pot cultivation. In May 2020, leaves and shoots were collected for inoculation in vitro, and at the same time, inoculation was carried out on plants in vivo in the field.

Table 1. Nineteen types of Malus plants.

Number Resource name Scientific name Resource type Origin 1 Huazhen No. 5 Malus domestica Borkh. Rootstock variety Liaoning, China 2 SH3 Malus domestica Borkh. Rootstock variety Shanxi, China 3 SH6 Malus domestica Borkh. Rootstock variety Shanxi, China 4 OT3 Malus domestica Borkh. Rootstock variety Canada 5 M9T337 Malus domestica Borkh. Rootstock variety Netherlands 6 B118 Malus domestica Borkh. Rootstock variety Russia 7 E Shanjingzi No. 2 Malus baccata (L.) Borkh. Wild resources Russia 8 Shajinhaitang Malus sargentii Rehd. Wild relatives Japan 9 Xiaojinhaitang Malus xiaojinensis Cheng et Jiang Wild resources Sichuan, China 10 Xiaogucheng Lenggunzi No. 1 Malus robusta (Carr.) Rehd. Landraces Hebei, China 11 Daobazui Wuxianghaitang Malus honanensis Rehd. Wild resources Shanxi, China 12 Longdonghaitang Malus kansuensis (Batal.) chneid. Wild resources Gansu, China 13 Balenghaitang Malus robusta (Carr.) Rehd. Landraces Hebei, China 14 Luanzhuang Shaguo Malus asiatica Nakai. Landraces Hebei, China 15 Zhaojue Shanjingzi Malus baccata (L.) Borkh. Wild resources Yunnan, China 16 Xishuhaitang Malus prattii (Hemsl.) Schneid. Wild resources Sichuan, China 17 Chuisihaitang Malus halliana Koehne, Gatt.Pomac Wild resources Gansu, China 18 Shidong Caiping No. 1 Malus domestica Borkh. Subsp. Chinensis Li Y.N. Landraces Hebei, China 19 Yingyehaitang Malus ceracifolia Spach. Wild resources Liaoning, China Preparation of bacterial suspension

-

The preparation of the bacterial solution was carried out according to the method of Li et al.[13]. The fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora (E.a 6) was used. The concentration of the bacterial solution was 1 × 107 CFU·mL−1, and the OD600 was about 0.4[14].

Inoculation of leaves in vitro

-

First, new shoots of Malus plants were selected, and the third or fourth fully expanded healthy young leaves from the upper part were taken. Then, these leaves were washed with ddH2O, and their excess petioles were cut off. In the ultra-clean bench, a toothpick was dipped into the bacterial solution, with the bacterial suspension on the toothpick appearing as a hanging drop. Each sample was inoculated by piercing the main vein from the back of the young leaf. The inoculated young leaf was put on a triangular toothpick stand in a petri dish lined with sterile, moist filter paper, with its back facing up. Each petri dish contained one young leaf, then it was cultivated in a constant temperature incubator at 28 °C. The total length of the leaves and the length of the necrotic lesion were measured after 72 h.

Inoculation of shoots in vitro

-

Undamaged, healthy shoots of uniform size were selected from each Malus plant, and artificial inoculation conducted. First, they were washed with ddH2O and a 0.5 cm length cut off at the bottom, in the shape of a horseshoe. A toothpick was dipped in the bacterial solution, with the bacterial suspension on the toothpick appearing as a hanging drop. Inoculation was performed by inserting the toothpick 2 mm deep into the main stem at the base of the second fully expanded leaf. The inoculated shoots were placed in an environment containing 2% sucrose water for incubation, and the sucrose water was changed every 24 h. Humidity was maintained by spraying water mist. Total length and necrotic lesion length were measured two weeks after inoculation of the shoots.

Inoculation of young plants in vivo

-

When the seedlings of each resource grew to 50 cm in height, ten plants were selected with consistent growth vigor from each. These plants were placed in screening chambers and inoculated with Erwinia amylovora. The inoculation method was the same as that of the inoculation of young shoots in vitro. The total length and necrotic lesion length of the inoculated shoots were measured two weeks after inoculation.

Resistance evaluation

-

The infection conditions were recorded at different time points depending on the plant material: 72 h after inoculation on young leaves in vitro, and two weeks after inoculation on young shoots in vitro and young plants in vivo. The infection conditions of fire blight were classified according to the classification standard[15]. To reduce the influence of uneven lengths of young leaves and young shoots, the lengths of the lesions on young leaves and young shoots were normalized by dividing them by the longest lesion length of each. The normalized ratio was used as the classification value: Grade 0: no necrotic lesion on the shoots and normal leaves. Grade 1: The length of the necrotic lesion accounted for 1% to 5% of the total length. The leaves turned blackish-brown and did not fall off. Grade 3: The length of the necrotic lesion accounted for 5.1% to 15% of the total length. The leaves turned blackish-brown, and some leaves fell off. Grade 5: The length of the necrotic lesion accounted for 15.1% to 30% of the total length, the leaves turned blackish-brown, and about one-third of the leaves fell off. Grade 7: The length of the necrotic lesion accounted for 30.1% to 50% of the total length, the leaves turned blackish-brown, and about two-thirds of the leaves fell off. Grade 9: The length of the necrotic lesion accounted for 50.1% of the total length, the leaves turned blackish-brown, and half or more of the leaves fell off.

The disease index was calculated based on the disease condition classification. The calculation method of the disease index was as follows:

$ \text{DI}=\dfrac{\sum (\mathrm{N}\times \mathrm{G})}{\mathrm{T}\times \mathrm{H}}\times 100 $ where, DI = Disease Index; N = Number of diseased plants at each level; G = Corresponding disease grade; T = Total number of inoculated plants; H = The highest disease grade.

The classification criteria for the resistance of fire blight were as follows: High resistance (HR): DI was (0, 5]; Resistance (R): DI was (5, 15]; Tolerance (T): DI was (15, 30]; Moderate susceptibility (MS): DI was (30, 60]; Susceptibility (S): DI was (60, 80]; High susceptibility (HS): DI was (80, 100].

Resistance evaluation reference standards

-

In previous studies[16], by inoculating young plants with OT3, it was confirmed that OT3 was susceptible to infection by Erwinia amylovora. Therefore, the results obtained with OT3 in this study served as a reference for comparing the inoculation methods.

Data statistical analysis

-

Each experimental procedure was performed in triplicate. Excel (Microsoft 365) was utilized for comprehensive data processing, including organization, calculation of means, and coefficient of variation, as well as the generation of standardized column charts. Based on one-way ANOVA, Duncan's multiple range test (p < 0.05) in SPSS 27.0 was used for statistical analysis.

-

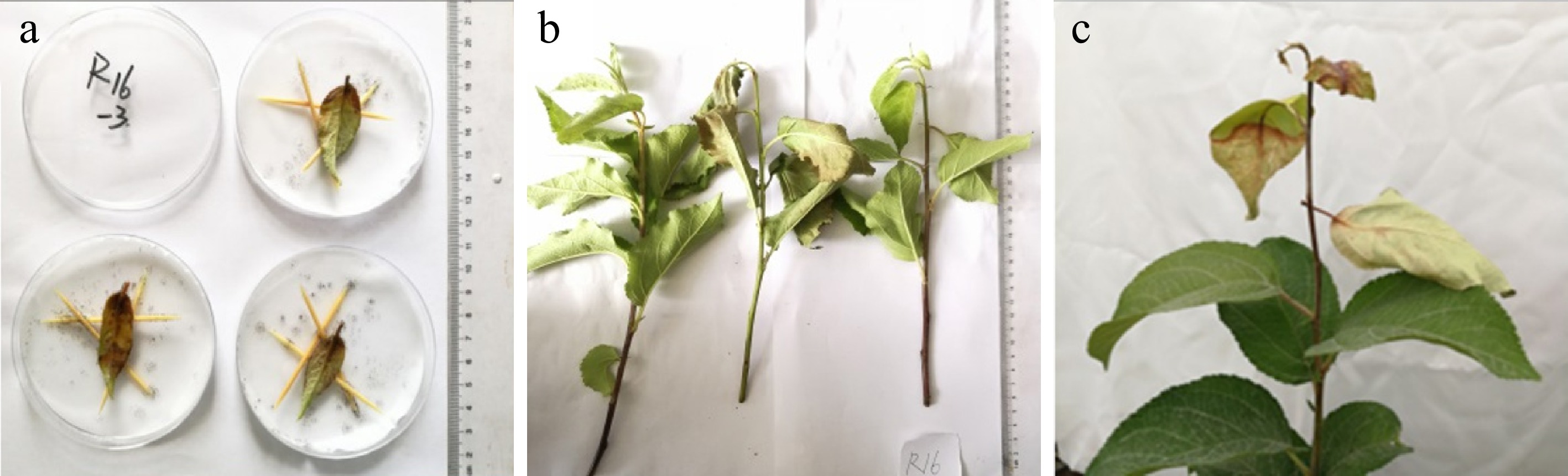

After 72 h of inoculation (Fig. 1a), the disease index of 19 Malus plants ranged from 31.11 to 100 (Table 2). It was categorized into four types: tolerant, moderately susceptible, susceptible, and highly susceptible, with a ratio of 1:1:6:11. Among them, only Shidong Caiping No. 1 was evaluated as tolerant. Luanzhuang Shaguo was moderately susceptible. A total of six resources—M9T337, Shajinhaitang, Xiaogucheng Lenggunzi No. 1, Longdonghaitang, Balenghaitang, and Yingyehaitang—were susceptible. The remaining 11 resources were highly susceptible. The variation coefficients of each replicate of each resource ranged from 0.00% to 52.70%. The one with the highest coefficient of variation was Shidong Caiping No. 1.

Figure 1.

Incidence of (a) young leaves in vitro, (b) young shoots in vitro, and (c) young plants in vivo.

Table 2. Results of three different inoculation methods of Malus plants for resistance to fire blight.

Number Resource name Leaf inoculation Shoot inoculation Plant inoculation Disease index Coefficient of variation Resistance evaluation Disease index Coefficient of variation Resistance evaluation Disease index Coefficient of variation Resistance evaluation 1 Huazhen No. 5 92.59a 13.85% HS 0.00c 0.00% HR 55.55b 0.00% MS 2 SH3 92.59a 13.85% HS 0.00b 0.00% HR 87.30a 13.60% HS 3 SH6 92.59a 13.85% HS 0.00c 0.00% HR 66.66b 19.24% S 4 OT3 100a 0.00% HS 0.00c 0.00% HR 71.42b 29.59% S 5 M9T337 77.78a 0.00% S 0.00b 0.00% HR 77.78a 18.07% S 6 B118 92.59a 13.85% HS 92.59a 13.85% HS 74.60a 20.55% S 7 E Shanjingzi No. 2 100 0.00% HS 0.00 0.00% HR 0.00 0.00% HR 8 Shajinhaitang 80.00a 24.32% S 53.33a 36.48% MS 0.00b 0.00% HR 9 Xiaojinhaitang 84.44a 21.67% HS 84.44a 17.76% HS 88.89a 24.30% HS 10 Xiaogucheng Lenggunzi No. 1 77.78a 28.57% S 0.00b 0.00% HR 0.00b 0.00% HR 11 Daobazui Wuxianghaitang 85.18a 15.06% HS 0.00c 0.00% HR 51.85b 17.49% MS 12 Longdonghaitang 77.78a 35.63% S 17.78b 109.71% T 0.00b 0.00% HR 13 Balenghaitang 77.78a 23.33% S 28.89b 48.65% T 40.00b 26.84% MS 14 Luanzhuang Shaguo 45.56a 46.63% MS 8.89b 114.87% R 33.33a 0.00% T 15 Zhaojue Shanjingzi 84.44a 21.67% HS 84.44a 21.67% HS 88.89a 13.18% HS 16 Xishuhaitang 82.22a 21.32% HS 66.67b 23.57% MS 88.89a 17.68% HS 17 Chuisihaitang 84.44a 21.67% HS 91.11a 12.60% HS 51.11b 27.50% MS 18 Shidong Caiping No. 1 31.11a 52.70% T 16.67a 137.88% T 0.00b 0.00% HR 19 Yingyehaitang 73.33a 23.90% S 4.44b 124.71% HR 0.00b 0.00% HR Different letters (a, b, c) on the same row indicated values that were significantly different (p < 0.05) based on one-way ANOVA, Duncan post-hoc test. And E Shanjingzi No. 2 exhibited zero variance across all inoculation methods, this extreme situation violated the basic assumptions of ANOVA. Therefore, no significance analysis was conducted on this set of data. Evaluation and screening of shoots inoculation in vitro

-

Two weeks after inoculation, the length of the necrotic lesion on the shoots was measured and compared from 8:00 to 12:00 on the 14th day (Fig. 1b). The disease index was between 0.00 and 92.59 (Table 2). It was categorized into five types: highly resistant, resistant, tolerant, moderately susceptible, and highly susceptible, with a ratio of 9:1:3:2:4. Among them, nine resources exhibited highly resistant to fire blight: Huazhen No.5, SH3, SH6, OT3, M9T337, E Shanjingzi No. 2, Xiaogucheng Lenggunzi No. 1, Daobazui Wuxianghaitang, and Yingyehaitang. One resource was resistant to fire blight: Luanzhuang Shaguo. Three were tolerant to fire blight: Longdonghaitang, Balenghaitang, and Shidong Caiping No. 1. Two were moderately susceptible to fire blight: Shajinhaitang, and Xishuhaitang. Four were highly susceptible to fire blight: B118, Xiaojinhaitang, Zhaojue Shanjingzi, and Chuisihaitang. The coefficient of variation ranged from 0.00% to 137.88%. Among them, Longdonghaitang, Luanzhuang Shaguo, Shidong Caiping No. 1, and Yingyehaitang exhibited higher coefficients of variation.

Evaluation and screening of young plants inoculation in vivo

-

Two weeks after inoculation, the length of the necrotic lesion on the propagation seedlings after inoculation was measured (Fig.1c). The results were listed in Table 2. The disease index was between 0.00 and 88.89. It was categorized into five types: highly resistant, tolerant, susceptible, moderately susceptible, and highly susceptible, with a ratio of 6:1:4:4:4. Among them, six resources were highly resistant to fire blight: E Shanjingzi No. 2, Shajinhaitang, Xiaogucheng Lenggunzi No. 1, Longdonghaitang, Shidong Caiping No.1, and Yingyehaitang. One was tolerant to fire blight: Luanzhuang Shaguo. Four resources were susceptible to fire blight: SH6, OT3, M9T337, and B118. Four resources were moderately susceptible to fire blight: Huazhen No.5, Daobazui Wuxianghaitang, Balenghaitang, and Chuisihaitang. Four resources were highly susceptible to fire blight: SH3, Xiaojinhaitang, Zhaojue Shanjingzi, and Xishuhaitang. The coefficient of variation of each resource ranges from 0.00% to 29.59%.

Comparison of the evaluation results of the three inoculation methods

-

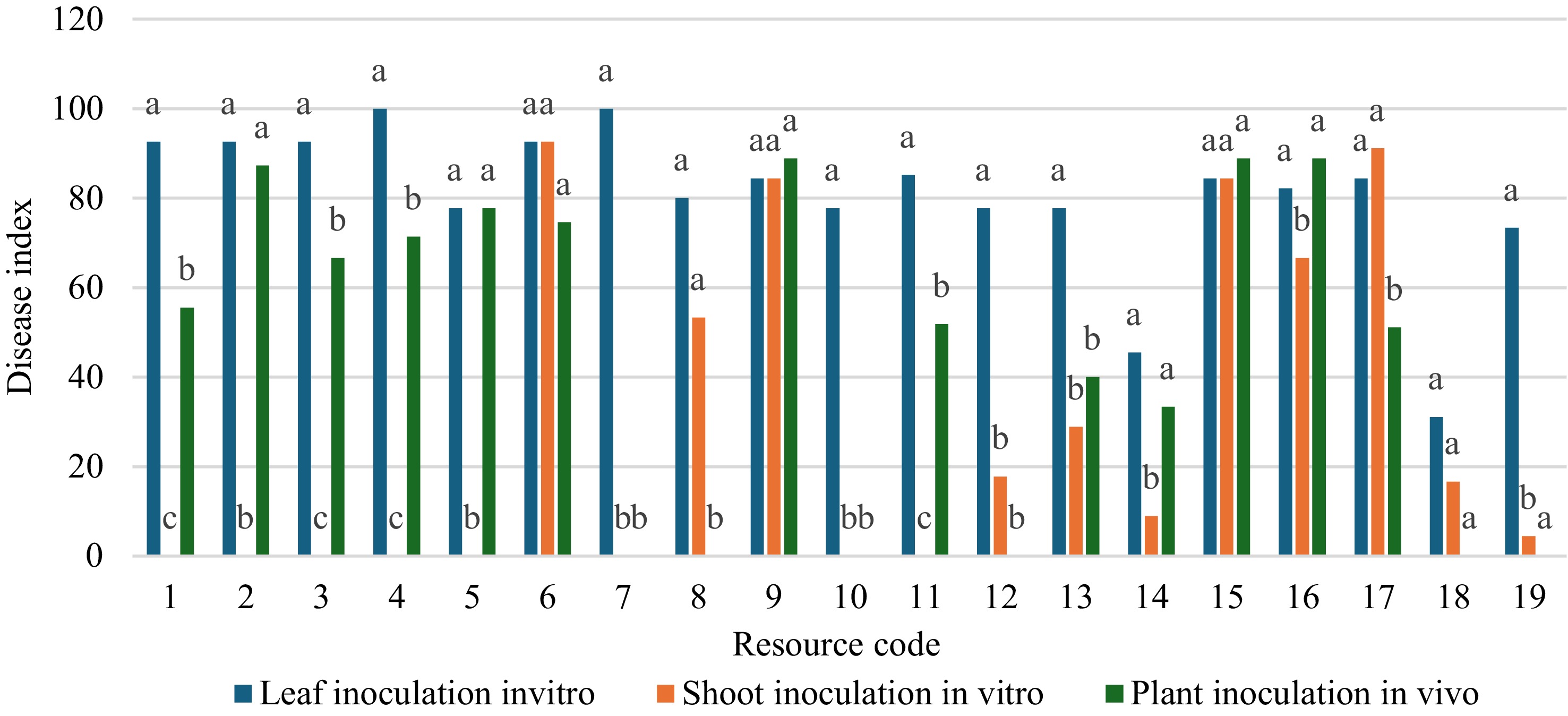

Through one-way ANOVA and Duncan's post-hoc test, the resistance evaluation results obtained by the three methods were compared and analyzed (Fig. 2). Firstly, a comparative analysis of the two inoculation methods in vitro revealed that among the 19 resources, only B118, Shajinhaitang, Xiaojinhaitang, Zhaojue Shanjingzi, Chuisihaitang, and Shidong Caiping No. 1 showed no significant difference in resistance outcomes under the two conditions, while others exhibited varying degrees of discrepancy. Although both methods involve inoculation in vitro, due to the different inoculation positions, the integrity of the materials might vary, resulting in inconsistent resistance evaluation results between young leaves inoculation and young shoots inoculation in vitro. Next, the two inoculation methods that were both applied to the shoots would be analyzed. Among the 19 resources, the resistance results of some resources under the two inoculation conditions showed no significant differences, including B118, Xiaojinhaitang, Xiaogucheng Lenggunzi No. 1, Longdonghaitang, Balenghaitang, Zhaojue Shanjingzi, and Yingyehaitang. However, the remaining resources showed varying degrees of differences. Although the inoculation sites of the two methods were the same, the differences in the identification results occurred due to the different physiological states.

The fundamental purpose of disease resistance identification was to accurately predict the performance of germplasm resources in their natural growth environment. Therefore, the form of young plants inoculation was more in line with the standard, as it can most realistically simulate the natural infection process and the complex physiological state of the plant as a whole. The results obtained from this were of the highest predictive value for actual agricultural production. Previous studies, using the method of young plants in vivo inoculation has established OT3 as susceptible to Erwinia amylovora. The identification results obtained in this study were consistent with previous studies. Therefore, the results obtained with OT3 in this study served as a reference for comparing the inoculation methods. At the same time, for some resources, the results of young shoots inoculation in vitro did not have a statistically significant difference from those of shoots inoculation in vivo. This meant that the young shoots technique in vitro had the potential to be used as an efficient and reliable method to replace the more time-consuming and labor-intensive inoculation method in vivo for the preliminary screening of large-scale germplasm resources in the early stage. By combining the ecological relevance advantages of the method in vivo with the efficiency advantages of the shoots method in vitro, more reliable identification results can be obtained. Therefore, based on the resistance evaluation obtained from young plants in vivo and combined with the evaluation from young shoots in vitro as a reference, three resistance resources have been obtained, namely E Shanjingzi No. 2, Xiaogucheng Lenggunzi No. 1, and Yingyehaitang.

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of the same resource using different inoculation methods (the numbers 1 to 19 on the horizontal axis represented the resource codes in Table 1). Different letters (a, b, c) on the same group indicate values that were significantly different (p < 0.05) based on one-way ANOVA, Duncan post-hoc test.

-

In the current prevention and control of fire blight, resistance breeding[17], physical control[8], chemical control[18], and biological control[19] were used. However, these measures did not thoroughly eliminate the damage caused by fire blight to the fruit industry. Screening for resistance resources and cultivating resistant varieties was the most fundamental and effective strategy. Resistance evaluation was the basis for pathogenicity research and resistant breeding, and methods of resistance evaluation were critical. Therefore, it was of great practical significance to study and establish a set of resistance evaluation technology systems that were reliable and accurate[20]. Fire blight mainly harmed the flowers, leaves, shoots, trunks, and rootstocks of fruit trees such as apples and pears, eventually leading to tree death and orchard yield reduction[21]. Therefore, the resistance to fire blight could be evaluated by a variety of inoculation methods, such as flowers, young leaves, young shoots, and young plants. Erwinia amylovora could easily infect flowers during the flowering period[22], but the incidence of the disease on flowers was difficult to evaluate. The current method for evaluating resistance to fire blight was mainly based on artificial inoculation. It could quickly and accurately screen resistant materials and was suitable for situations where there were few materials and only one disease was being evaluated[23]. Within this framework, incidence rate and lesion proportion were commonly used to evaluate host disease resistance[24]. Harshman et al. obtained 12 resources resistant to fire blight among nearly 200 samples of Malus sieversii, using young shoot inoculation[25]. Ozrenk et al. used young shoots inoculation to evaluate the resistance of 32 apple resources, of which five were rated as resistant, seven as moderate resistance, nine as moderate susceptibility, five as susceptibility, and six as high susceptibility[26]. Liu et al. evaluated the resistance of 54 pear resources by inoculating fruits, with resistant resources accounting for 70.4%[27]. Zhu et al. identified 28 resources with moderate resistance or higher to fire blight among 258 Malus sieversii samples, from seven natural populations through young shoot inoculation and field evaluation[28]. Cao et al. identified five resistant resources among 83 Malus sieversii samples through leaf in vitro and shoot inoculation, which can serve as foundation materials for breeding resistant rootstocks[29]. Consistent with the methods of predecessors, the resistance was evaluated using a combined inoculation method that targeted both young leaves and young shoots. Erwinia amylovora was inoculated on young leaves, shoots in vitro, and young plants in vivo, respectively. Ultimately, a total of three highly resistant resources were screened, namely E Shanjingzi No. 2, Xiaogucheng Lenggunzi No. 1, and Yingyehaitang. The three resources came from Russia and China, respectively. Among them, Xiaogucheng Lenggunzi No. 1 was a landrace, while the others were wild resources.

The 19 resources used in this experiment came from 12 different species. Among them, the three evaluated resistant resources belonged to 'Malus baccata (L.) Borkh.', 'Malus robusta (Carr.) Rehd.', and 'Malus ceracifolia Spach.' respectively. Zhaojue Shanjingzi belonged to the same species as E Shanjingzi No. 2. The Balenghaitang was also part of the same species as Xiaogucheng Lenggunzi No. 1. However, in this experiment, Zhaojue Shanjingzi and Balenghaitang were not evaluated as resistant resources. The variation in fire blight resistance among different resources of the same species was possibly due to distinct genetic backgrounds shaped by their geographical origins, and was further modulated by morphological factors. In previous studies[30,31], QTLs for resistance to fire blight have been identified in the wild species M. baccata and M. robusta. These two species were consistent with those in this experiment. However, in this experiment, some varieties were identified as resistant resources, which was not the case for others. This might be due to the differences in resistance to fire blight within the same species. It is also well-established from prior studies that resistance and susceptibility to fire blight varies within and among Malus species[32].

Liu et al. conducted inoculation on pear at the young fruit stage, expansion stage, and maturity stage. The results showed that the inoculation on young fruit was more accurate than the expansion and maturity stages of pear[33]. Wang et al. found five hawthorn resources showed different pathogenic responses to the fire blight by inoculation of the leaves, shoots, and young fruits in vitro[34]. Jing et al. found that the resistance to fire blight of different tissues of the seven crabapple varieties was different under the same experimental conditions[35]. It was found that shoots and flower inoculation were poorly correlated, indicating that the resistance of different parts were different[36]. The studies by Zhu et al. also showed that there were certain differences in the resistance to fire blight of young leaves and young shoots of the tested red flesh apples[37]. Wang et al. evaluated the resistance of 488 Malus resources and found that the number of resistant resources inoculated by young shoots in vitro was significantly more than that by young leaves[15]. All the above-mentioned studies have shown that resistance to fire blight for the same resource was different with different inoculation periods, different inoculation methods, and different inoculation sites. The same conclusion was also obtained in this study. For the same resource, when three different methods were inoculated with Erwinia amylovora, there were differences in the degree of resistance, and the number of resistant resources obtained varies. Therefore, in fire blight resistance evaluation, it is not advisable to rely solely on a single method. Instead, an integrated approach combining multiple techniques should be adopted, depending on the scale of screening and the specific objectives of the study.

Multiple factors contributed to such differential outcomes, as documented in prior studies. Plants formed complex defense mechanisms containing morphological structures and physiological and biochemical changes in the long-term interaction and adaptation with pathogenic bacteria. Pathogens first attached to the plant surface, the size and shape of stomata, the thickness and tightness of the palisade and spongy tissue, and the uniformity of epidermal cells may affect the invasion and spread of pathogens in terms of morphological structure[38]. Crucially, morphological traits exhibited clear correlations with disease resistance: leaves can easily be infected by other pathogens and interfere with the experimental results. At the same time, there was a significant or highly significant positive correlation between stomata density, leaf thickness, upper epidermal thickness, lower epidermal thickness, and disease index[39]. Şahin studied the relationship between the leaf characteristics and its resistance to fire blight for quince. The results showed that the resistance to fire blight of quince was strongly correlated with leaf blade: undulation of margin[40]. Therefore, in the present experiment, the leaves were more susceptible. This might be due to the relatively young cell structure of the young leaves and the incomplete development of their defense mechanisms, or because the nutrients were more easily utilized by the pathogen. Additionally, the inoculation of shoots over a longer period of time would result in wilting, and the limited time for culture in vitro would also affect the physiological state of the plants. However, the method in vivo was closer to the natural environment, but the process was more complex and had limitations. Moreover, the phenotypic evaluation relied on manual judgment of the disease condition, which was highly subjective. This inherent subjectivity inevitably introduced variability into the evaluation of disease. To objectively quantify the extent of this variation and evaluate the consistency of different leaves, shoots, or evaluators, the coefficient of variation was calculated for the disease index. It was worth noting that among the four resources of Longdonghaitang, Luanzhuang Shaguo, Shidong Caiping No. 1, and Yingyehaitang, which were inoculated with young shoots in vitro, the coefficient of variation of the disease index was relatively high. According to the raw data, the high coefficients of variation observed in this experiment were primarily caused by the low mean values. The primary factor was that the mean value of the data set was very low. When the mean approaches zero, even if the absolute standard deviation is small, the coefficient of variation can become very large.

Currently, molecular identification techniques for plant diseases such as fire blight and other plant pathogens, including multiplex PCR and gene chips, have become increasingly mature in various host detection practices. Based on this solid foundation, the forefront of research is gradually shifting towards more efficient and comprehensive dimensions. Adomako et al. evaluated the resistance to Ralstonia solanacearum of tomato plants by using the method of molecular markers[41]. Khan et al. uncovered that the resistance of fire blight was regulated by multiple genes, and identified two novel QTLs and several functional candidate genes. It offered molecular tools and a theoretical basis for breeding resistant apple varieties[42]. Li et al. identified 125 candidate genes associated with grape white rot resistance through WGCNA analysis[43]. Fahrentrapp et al. identified the resistant genes associated with fire blight in Malus × robusta 5 through various methods, including fine mapping and gene prediction[44]. Stefano et al. showed that the expression of EFR in apple rootstock may be a valuable biotechnology strategy to improve the resistance of apple to fire blight[45]. Therefore, the combination of phenotype identification and molecular techniques should be applied to detect and evaluate fire blight resistance in the future.

-

This study evaluated fire blight resistance in 19 Malus plants using three inoculation methods—young leaves, young shoots in vitro, and young plants in vivo. The results demonstrated that there were significant differences in the resistance performance of different methods. The identification results established using young shoots in vivo served as the benchmark, supplemented by those obtained from young shoots in vitro. A total of three resistance resources were obtained, namely E Shanjingzi No. 2, Xiaogucheng Lenggunzi No. 1, and Yingyehaitang. Therefore, in the evaluation of fire blight resistance, it is recommended to adopt a combined approach using shoots in vitro and in vivo assays to obtain more reliable results, further integrated with molecular methods to achieve higher accuracy. The above three types of resistance resources can be used as parents for the breeding of resistant varieties. Furthermore, Xiaogucheng Lenggunzi No. 1 can also be used as a parent for the cultivation of fresh food varieties. This served as a reference for fire blight resistance breeding in Malus plants and the exploration of related resistance genes.

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program Project (2021YFE0104200-4), and the Science and Technology Innovation Project of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-ASTIP-2021-RIP-02).

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Wang D; data collection: Lu X, Gao Y, Sun S, Zhang X, Wang K, Liu Z; analysis and interpretation of results: Shang W, Guo H, Tian W, Wang L, Li Z, Li L; draft manuscript preparation: Shang W, Wang D. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article, and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Shang W, Gao Y, Lu X, Zhang X, Wang K, et al. 2025. Evaluation and screening of fire blight resistance in Malus plants. Technology in Horticulture 5: e042 doi: 10.48130/tihort-0025-0041

Evaluation and screening of fire blight resistance in Malus plants

- Received: 29 June 2025

- Revised: 14 November 2025

- Accepted: 07 December 2025

- Published online: 24 December 2025

Abstract: Fire blight, a devastating bacterial disease, primarily infects fruit trees of Rosaceous, leading to their decline and eventual death. This study aims to evaluate and screen the fire blight resistance in 19 Malus plants; additionally, the effectiveness and applicability of three inoculation methods were compared. The toothpick acupuncture method in young leaves, shoots in vitro, and young plants in vivo were used in this study. The results were significantly different from the three inoculation methods for some Malus plants. Under the inoculation conditions of young leaves in vitro, only Shidong Caiping No. 1 was tolerant to fire blight, exhibiting the highest resistance level, while others showed susceptibility at graded severity levels. Under the inoculation condition of young shoots in vitro, nine highly resistant resources were screened, such as OT3, SH3, SH6, etc. Under the inoculation condition of young plants in vivo, six highly resistant resources were obtained, included E Shanjingzi No. 2, Xiaogucheng Lenggunzi No. 1, Yingyehaitang, and so on. For practical applications, the evaluation of young shoots in vitro, and young plants in vivo should be integrated to achieve a comprehensive and accurate result. A total of three resistance resources were obtained, namely E Shanjingzi No. 2, Xiaogucheng Lenggunzi No. 1, and Yingyehaitang, which can be used for the breeding of parents of fire blight resistant varieties.

-

Key words:

- Fire blight /

- Evaluation /

- Malus Plants