-

The mango 'Tainong No.1' (Mangifera indica 'Tainong No.1') is one of the main varieties in Hainan province, China, which is renowned for its distinctive flavor and nutritional richness. It is extensively cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions worldwide, accounting for more than 25% of mango planting area and increasing annually[1,2]. However, as a climacteric fruit, mango is highly susceptible to mechanical damage, temperature fluctuations, and rapid ripening, leading to spoilage and reduced storage life, ultimately impacting its commercial viability[3]. Therefore, research on postharvest storage and preservation of mango is imperative for optimizing its shelf life and quality retention.

Various postharvest preservation methods have been extensively employed to extend the shelf life of fruits and vegetables, including phytohormones, low temperature storage, and antagonistic bacteria[4]. Among these, low temperature storage has emerged as a crucial technique for preserving a wide range of fruits. Generally, when the storage and transport temperature is higher than the critical cold damage temperature, the lower the temperature, the longer the preservation time[5]. For instance, storage at 0 °C prolonged the shelf life of grapes (Vitis vinifera L.) by 21 d compared to ambient storage[6]. Low temperature storage can significantly improve the quality of guava (Psidium guajava L.)[7]. Weight loss and firmness decline play important roles in the storability of fresh fruit, and they affect consumer acceptance directly[6]. Previous reports have demonstrated that low temperature storage can preserve fruit quality by inhibiting respiration rates and minimizing water loss, thereby maintaining firmness and freshness[8].

Moreover, the homeostasis of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is intricately linked to the onset of senescence of fruit and vegetables. ROS can both damage plant biomolecules and trigger defense mechanisms as a second messenger molecule[9]. Plants have a precise antioxidant system to regulate ROS homeostasis, comprising enzymes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), ascorbate peroxidase (APX) and phenylalanine ammonialyase (PAL), and non-enzymatic components, including vitamin C and phenolics[10−13]. Low temperature can maintain ROS homeostasis through enhancing the activity of antioxidant enzymes and increasing the content of antioxidant compounds. All of these contribute to improving fruit defense mechanisms and preserving nutritional value[14]. Additionally, shelf life after cold storage enhanced the activities of PAL and C4H in flavonoid biosynthesis, and increased the expression of carotenoid biosynthesis genes PSY, ZDS, and ZISO, which promoted the accumulation of flavonoids and carotenoids in nectarines (Prunus persica L.)[15].

In recent years, applications of low temperature to tropical fruits have been widely reported. For example, cold storage of passion fruit (Passiflora edulis) significantly delayed skin shrinkage and maintained quality compared to ambient conditions[16]. Compared with room temperature storage, the shelf life of dragon fruit (Hylocereus sp.) was extended by 10 d under a low-temperature environment[17]. Banana (Musa acuminata) ripening was significantly delayed by low temperature treatments[18]. Furthermore, fresh fruits and vegetables are still alive, and all physiological activities continue. Tropical fruits can be harvested in advance, kept at a relatively low temperature and transported to the sales site for artificial ripening, which can significantly reduce losses. For example, after storing bananas at a low temperature of 20 °C, the application of ethephon accelerates ripening without loss of fruit quality or flavor[19,20].

Currently, 'Tainong No.1' in Hainan Province is mostly picked at 80% ripeness and transported by road and railway to the sales place for ripening artificially and then sold. After harvesting, more than 90% of mangoes are stored and transported at ambient room conditions (26 ± 7 °C)[21]. Previous research showed that most ripe mangoes are susceptible to cold damage when stored and transported at temperatures below 12 °C[22]. Meanwhile, due to different maturities, the individual mango varieties have greatly different low temperature tolerance[23,24]. However, the appropriate low temperature conditions and the duration of 'Tainong No.1' mango preservation at these temperatures have not been reported in detail. Therefore, 12 °C was taken as the critical low temperature to study how and why low-temperature storage can maintain the fruit quality of 'Tainong No.1' mangoes.

The aim of this study was to clarify whether 12 °C is a suitable storage and transport temperature for 'Tainong No.1'. The impact of low temperature (12 °C) and ambient (30 °C) storage on the postharvest physiology and antioxidant properties of 'Tainong No. 1' mango was examined, focusing on antioxidant enzyme activity, cell morphology, gene expression, and other aspects of the harvesting of 'Tainong No.1'. Correlation analysis, qRT-PCR, and cytomorphological analysis were used to investigate the effects of low temperature storage on postharvest physiology and antioxidant defense-related enzymes in mango. The findings of this study offer valuable insights for the long-distance transportation and cold chain logistics of postharvest 'Tainong No.1' mango, with potential applications for other tropical fruits.

-

Mango fruits were harvested at commercial maturity (70%–80% ripeness, approximately 110 d after flowering, with less than 5% yellowing of the fruit skin, weighing about 200 g) from a mango orchard in Lingshui County, Hainan Province. The fruit was immediately transported to the laboratory without any preharvest treatment. Fruit free from disease and mechanical damage, and with uniform color and size, were selected and used in the study. The selected fruit was surface sterilized by soaking in a 0.1% sodium hypochlorite solution for 15 min, followed by rinsing and drying. Subsequently, the fruit was treated with 0.1% Spirocell solution for 10min, dried, and then set aside for further experimentation.

Fruit treatment

-

The cleaned fruit was randomly allocated to two temperature treatments (30 and 12 °C) and incubated in a climatic chamber (MGC-350BP, YiHeng, China). The experimental design consisted of three biological replicates per treatment, taking three fruits from each repetition for a total of nine fruits. Sampling was conducted at 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 d post treatment. Following sampling, fruit tissues were immediately flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent analyses.

Morphological analysis

-

Morphological observations were performed on tissue sections prepared in accordance with the protocol outlined by the previous report[25]. Briefly, 1 cm2 tissue samples were excised from three equidistant points on the kernel, approximately 0.5 cm from the center. The samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Biosharp), dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (70%, 85%, 95%, and 100%) followed by xylene, and embedded in paraffin wax. Part of the samples (5 μm) were cut using a microtome (Rm2245, LEICA, German), mounted on glass microscope slides, and stained with toluidine blue. After washing and sealing with gum, samples were examined using a light microscope (DP26, OLYMPUS, Japan).

Evaluation of fruit quality attributes

Peel color, firmness, and weight loss rate

-

Fruit skin color and firmness at the center of both the shaded and sunny sides of mangoes were measured using a colorimeter (Konica Minolta CM-700D, Japan) and a texture analyzer (TA TOUCH, Bao Sheng Technology, China), respectively. The color and firmness data were recorded and averaged. The weight loss rate was determined by weighing six mangoes from each treatment group at each sampling time point. The mass of mangoes in each group was recorded at each time point of sampling and compared to the initial mass to calculate the weight loss rate.

Total soluble solids (TSS) and cell membrane permeability (CMP)

-

TSS content was determined by extracting juice from mango pulp using four layers of gauze and measuring the juice with a digital refractometer (PAL-1, ATAGO, Japan), with results expressed as a percentage (%). CMP was assessed using a conductivity meter (ECOSCAN, Singapore). Mango peel samples (2 mm × 1 mm × 20 mm) were immersed in 25 ml of distilled water in a 50 mL glass centrifuge tube for 30 min. The initial conductivity was recorded. The tube was then heated, boiled for 15 min, cooled to room temperature (28 °C), and the final conductivity was recorded.

Titratable acidity (TA), vitamin C content, and respiration rate

-

TA content was determined using a standard 0.1% titration method and expressed as % malic acid equivalent. Vitamin C content was quantified using the 2,6-dichlorophenol indophenol titration method and expressed as mg 100 g−1 fresh weight[26]. Respiration rate was measured using an O2/CO2 headspace analyzer (Checkpoint 3 Premium O2/CO2, Mocon, Europe), involving 2 h incubation at 25 °C and subsequent O2 and CO2 concentration analysis.

Quantification of antioxidant related compounds

Malondialdehyde (MDA), total phenols, and flavonoids content

-

Malondialdehyde content was determined using the TBARS-TCA method as described in a previous report[27]. Total phenol and total flavonoid contents were assessed using a modified protocol based on the method in the previous study[28]. For total phenol and flavonoid extraction, 2 g of fruit pulp tissue was homogenized with 6 mL of 1% hydrochloric acid methanol solution on ice. The mixture was then incubated at 4 °C in darkness for 24 h, followed by centrifugation. The absorbance values of the resulting supernatant (3 mL) were measured at 280 and 325 nm using a spectrophotometer to quantify total phenols and flavonoids, respectively. Standard curves generated with gallic acid and rutin were used to calculate the contents of total phenols and flavonoids.

Analysis of H2O2 and O2−

-

The production rate of superoxide anion (O2−) and the content of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) were quantified using a commercial assay kit (Grace Biotechnology, China), following the manufacturer's instructions.

Determination of antioxidant enzyme activities

SOD and POD activities

-

SOD activity was determined using a modified protocol based on the method described in a previous study[29]. A 2 g sample of fruit pulp was homogenized in 5 mL of SOD extraction buffer, comprising 100 mmol L−1 sodium phosphate buffer, 5 mmol L−1 dithiothreitol, and 5% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP). The mixture was centrifuged to obtain a clear supernatant, which was then added to the reaction solution. Following a 15 min illumination period, the reaction was terminated, and SOD activity was determined in units of U kg−1. POD activity was determined using the guaiacol method[30]. POD activity was expressed as the absorbance at 470 nm of guaiacol oxidized by H2O2.

APX and PAL activities

-

APX and PAL activities were determined using commercial assay kits (Nanjing Jieji Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China). The specific assay methods were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions provided with the kits.

Relative expression of antioxidant enzyme genes

-

RNA extraction was carried out with the CTAB method in previous reports[31]. cDNA was synthesized using MonScriptTM RTIII All-in-One Mix with dsDNase kit (Mona, China) according to its manufactory instructions. The thermal cycling protocol used for qRT-PCR was as follows: 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s. The relative expression of genes was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method.

Statistical analysis

-

To ensure the reliability and accuracy of the experimental data, all experiments were conducted in triplicate, utilizing three biological replicates. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13.0 software (IBM Corp., USA). Multiple t-test analyses were employed to assess significant differences among treatments. All data are presented as mean ± standard error (SE), with statistical significance set at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

-

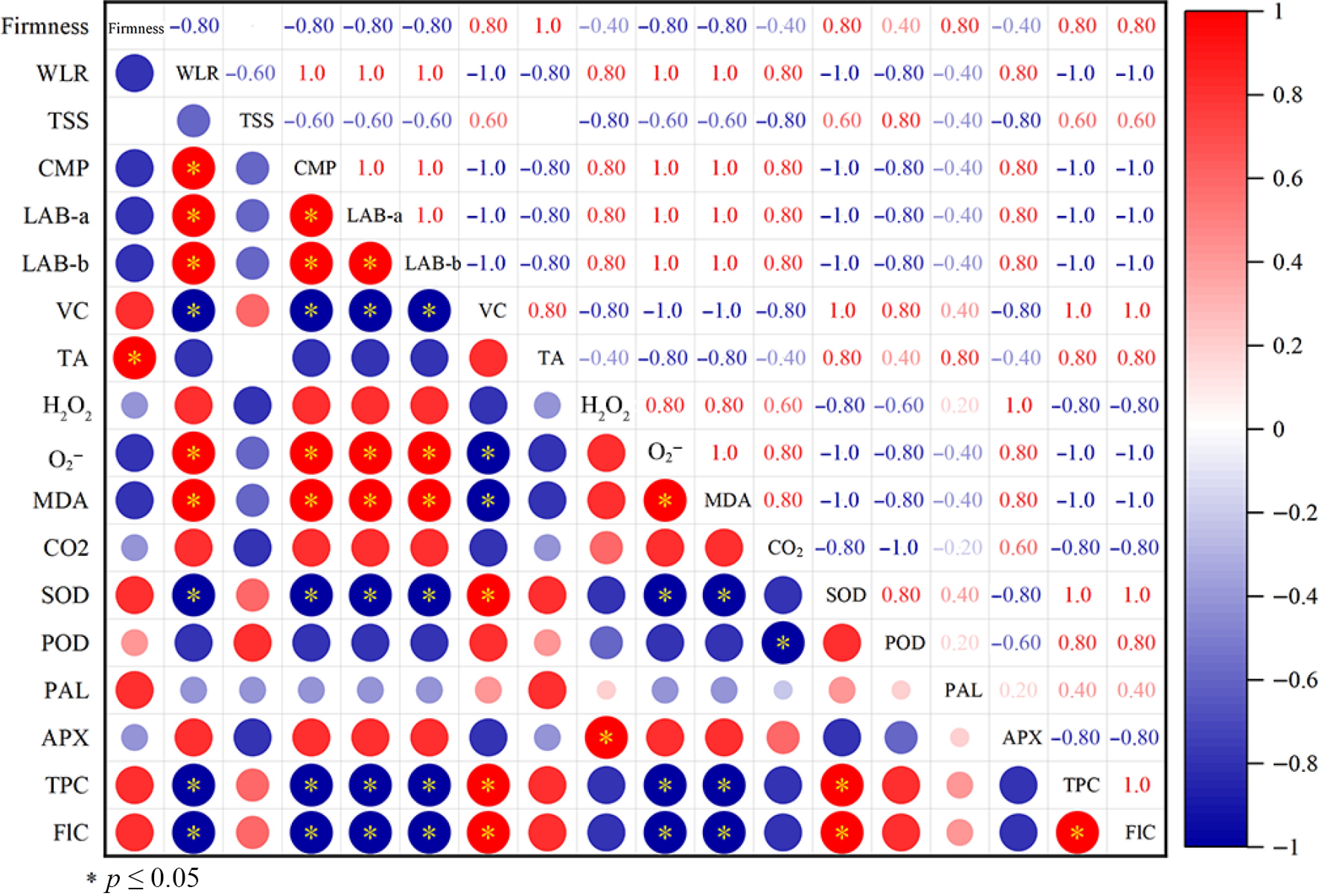

The impact of storage temperature on mango fruit quality was examined, revealing that initial visual appearance showed minor changes between mangoes stored at 12 and 30 °C for up to 12 d (Fig. 1a). However, beyond 16 d, mangoes stored at 30 °C exhibited pronounced yellowing, whereas those stored at 12 °C retained their color. The chromaticity values (a* and b*) increased over time, with a more prominent increase observed at 30 °C (Fig. 1b, c), indicating that low temperature storage (12 °C) can effectively inhibit mango color change and chlorophyll degradation. Furthermore, the TSS content of mangoes stored at 30 °C increased initially, peaked at 16 d, and then declined (Fig. 1d), whereas the TSS content of mangoes stored at 12 °C remained lower and increased gradually. Additionally, the TA content of mangoes stored at 30 °C decreased more rapidly than that of mangoes stored at 12 °C (Fig. 1e), with the TA content of mangoes stored at 12 °C remaining significantly higher throughout the storage period (p < 0.01), exhibiting a 371% increase and indicating that storage at 12 °C effectively inhibits TA degradation.

Figure 1.

Changes in (a) fruit appearance, (b) a* value, (c) b* value, (d) TSS content, and (e) TA content of mango fruits stored at 30 and 12 °C. Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean, the asterisks indicate significant difference between two groups at corresponding sampling point (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

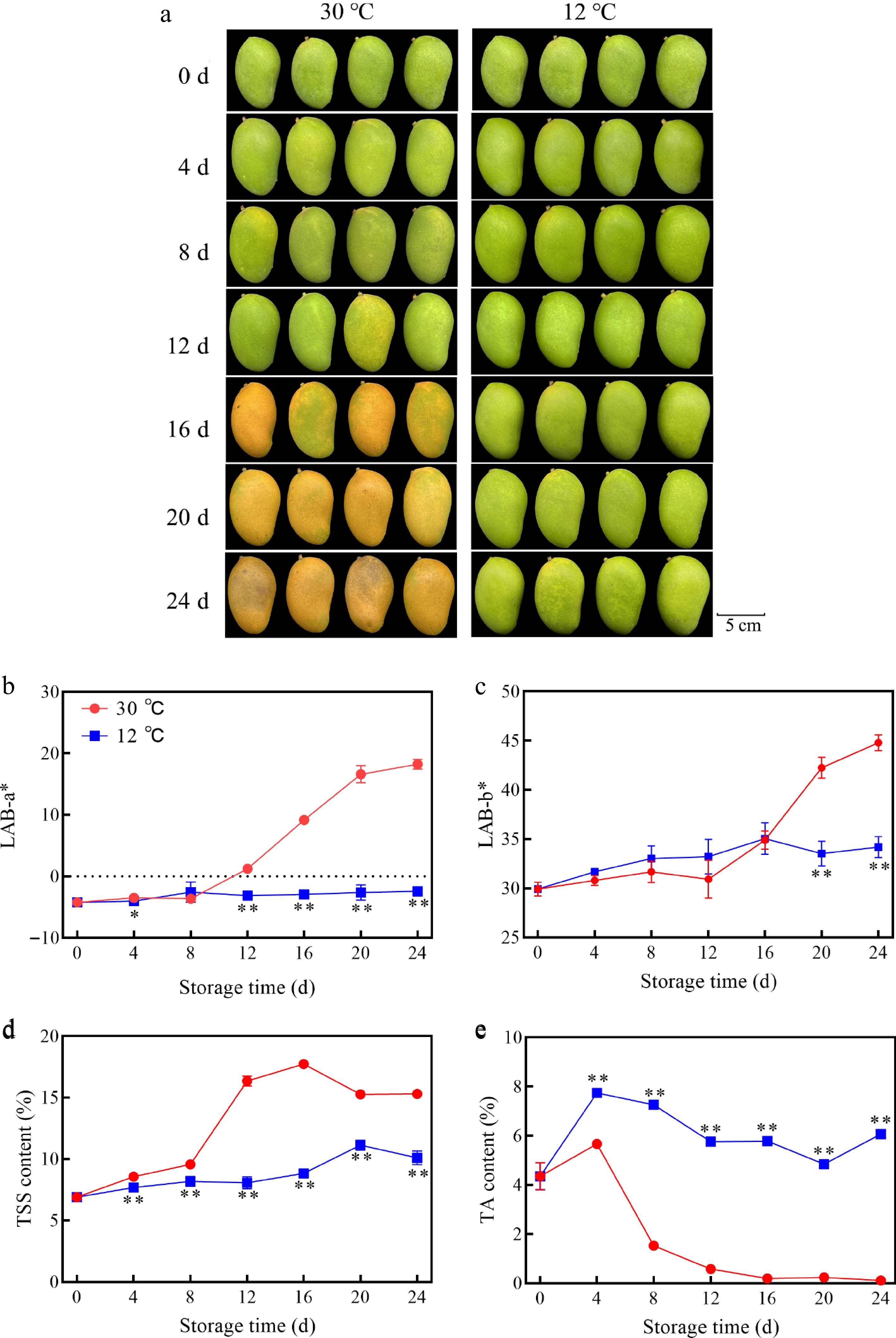

Storage temperature-induced changes in mango pulp cell morphology and fruit physiology

-

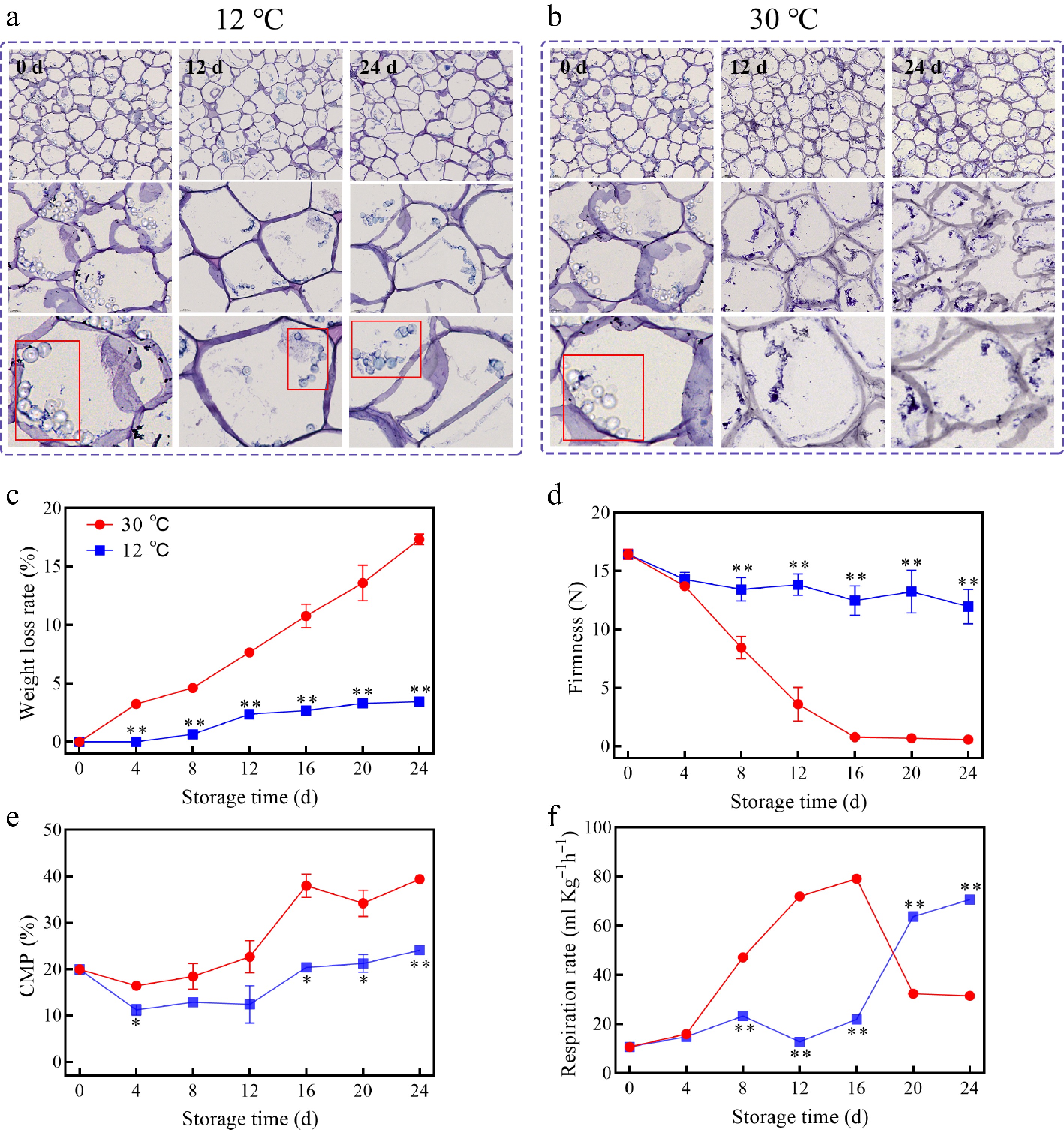

Fresh pulp cells exhibited a characteristic irregular shape and tight packing, featuring dense and smooth cell walls and abundant starch granules (rounded and clustered spheres in the red box (Fig. 2a). As storage time elapsed, pulp cells underwent pronounced transformations, becoming rounded and enlarged due to cell wall degradation, which alleviated protoplasmic pressure and facilitated cell expansion. A comparative analysis revealed that pulp cells stored at 12 °C retained their structural integrity, with negligible changes in cell wall morphology and starch granule content, even after 24 d. However, pulp cells stored at 30 °C exhibited accelerated degradation, characterized by loose flocculation, complete starch granule depletion, and cell wall thinning and rupture by 12 d, ultimately leading to cell collapse by 24 d (Fig. 2a, b).

Figure 2.

Changes of pulp cell in SEM at (a) 12 °C, (b) 30 °C, (c) weight loss, (d) firmness, (e) CMP, (f) respiration rate of mango fruits stored at 30 and 12 °C. Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean, the asterisks indicate significant difference between two groups at corresponding sampling point (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

The weight loss rate of mangoes stored at 30 °C exhibited a linear increase over time, whereas storage at 12 °C resulted in a relatively stable weight loss rate on 24 d, with values of 17.332% ± 0.451% and 3.455% ± 0.400%, respectively (Fig. 2c). Furthermore, firmness measurements revealed an overall decreasing trend, with storage at 12 °C significantly mitigating the decline in firmness, whereas mangoes stored at 30 °C exhibited a rapid decline in firmness, plateauing at 0.800 ± 0.401 N by the 16 d (Fig. 2d). Furthermore, CMP of mangoes stored at both temperatures exhibited an increasing trend (Fig. 2e). Notably, mangoes stored at 12 °C maintained a high level of firmness throughout the storage period, characterized by a gradual decline in values. As a climacteric fruit, mangoes exhibit a distinct respiratory peak during ripening, which accelerates fruit senescence. Especially, mangoes stored at 30 °C reached their peak respiration rate on 16 d, followed by a continuous decline, whereas those stored at 12 °C exhibited a delayed respiratory peak, occurring on 24 d, thereby extending the preclimacteric phase by 8 d (Fig. 2f). Hence, storage at 12 °C effectively inhibited the respiration rate, delayed softening, and late maturity and senescence.

Storage temperature-induced changes in antioxidant quality of mango fruit

-

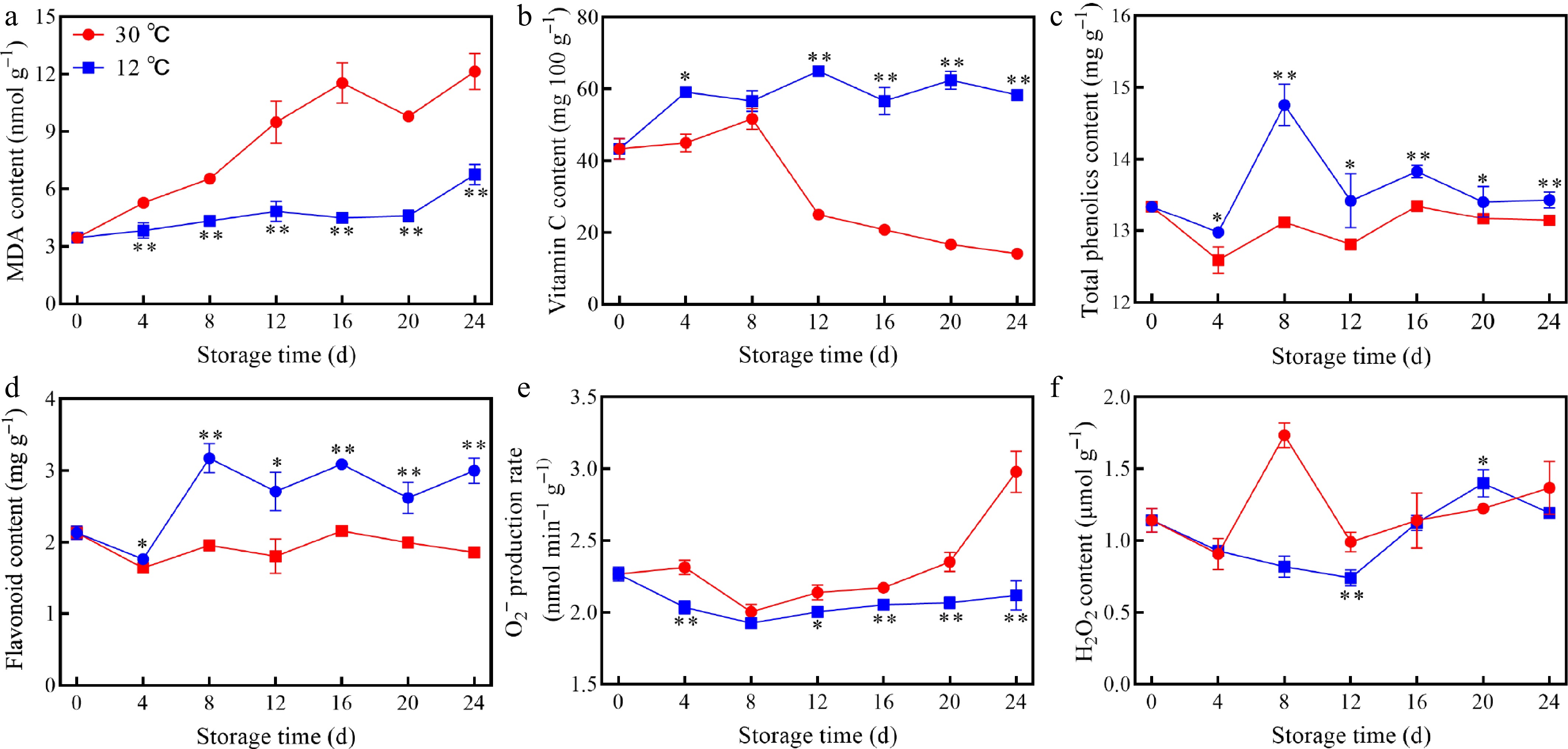

The impact of different storage temperatures on the antioxidant quality of mango fruits was explored. Results showed that MDA content of mangoes at 30 °C increased significantly compared to 12 °C between 4 and 24 d (Fig. 3a), while vitamin C content at 30 °C showed a converse change trend compared with MDA. However, contents of MDA and vitamin C all displayed relatively smooth fluctuations during the whole storage time (Fig. 3b). Phenolic compounds of mangoes at 12 °C, including total phenols and flavonoids, were significantly higher than that at 30 °C (Fig. 3c, d), while O2− production rate and H2O2 content at 30 °C fluctuated more pronouncedly compared with 12 °C (Fig. 3e, f). Overall, storage at 12 °C effectively preserved the antioxidant capacity of mango fruit.

Figure 3.

Changes in (a) MDA content, (b) vitamin C content, (c) TP content, (d) flavonoid content, (e) O2− production rate, and (f) H2O2 content of mango fruits stored at 30 and 12 °C. Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean, the asterisks indicate significant difference between two groups at corresponding sampling point (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

Storage temperature-induced changes in antioxidant enzyme activities of mango fruit

-

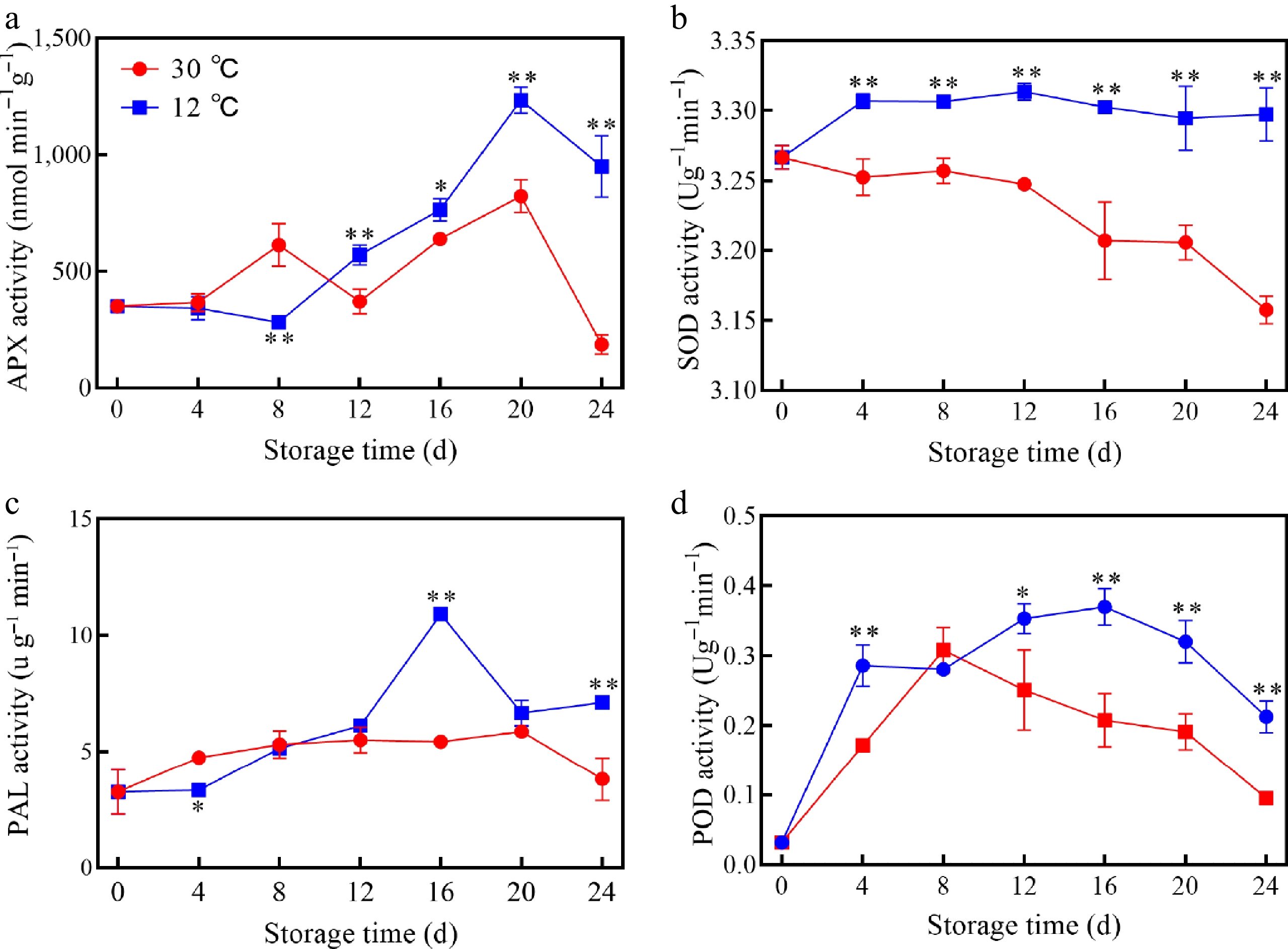

The activities of antioxidant-related enzymes in mango fruits were significantly influenced by storage temperature. The overall APX activity showed an increasing and then decreasing trend, and the activity increased sharply from 12 to 20 d, reached the peak, and then began to decline. Compared with 30 °C, APX activity at 12 °C always remained at a higher level after 12 d (Fig. 4a). In contrast, SOD activity decreased gradually at 30 °C, but remained stable at 12 °C (Fig. 4b). PAL activity showed an initial increase followed by a decrease at both temperatures, with overall higher activity observed at 12 °C (Fig. 4c). With the prolongation of storage time, POD activity showed an increasing and then decreasing trend, while POD activity at 12 °C on 8 and 12 d were significantly higher than that at 30 °C (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

Changes in (a) APX, (b) SOD, (c) PAL, and (d) POD of mangoes stored at 30 and 12 °C. Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean, the asterisks indicate significant difference between two groups at corresponding sampling point (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

Storage temperature-induced transcriptional regulation of antioxidant genes in mango

-

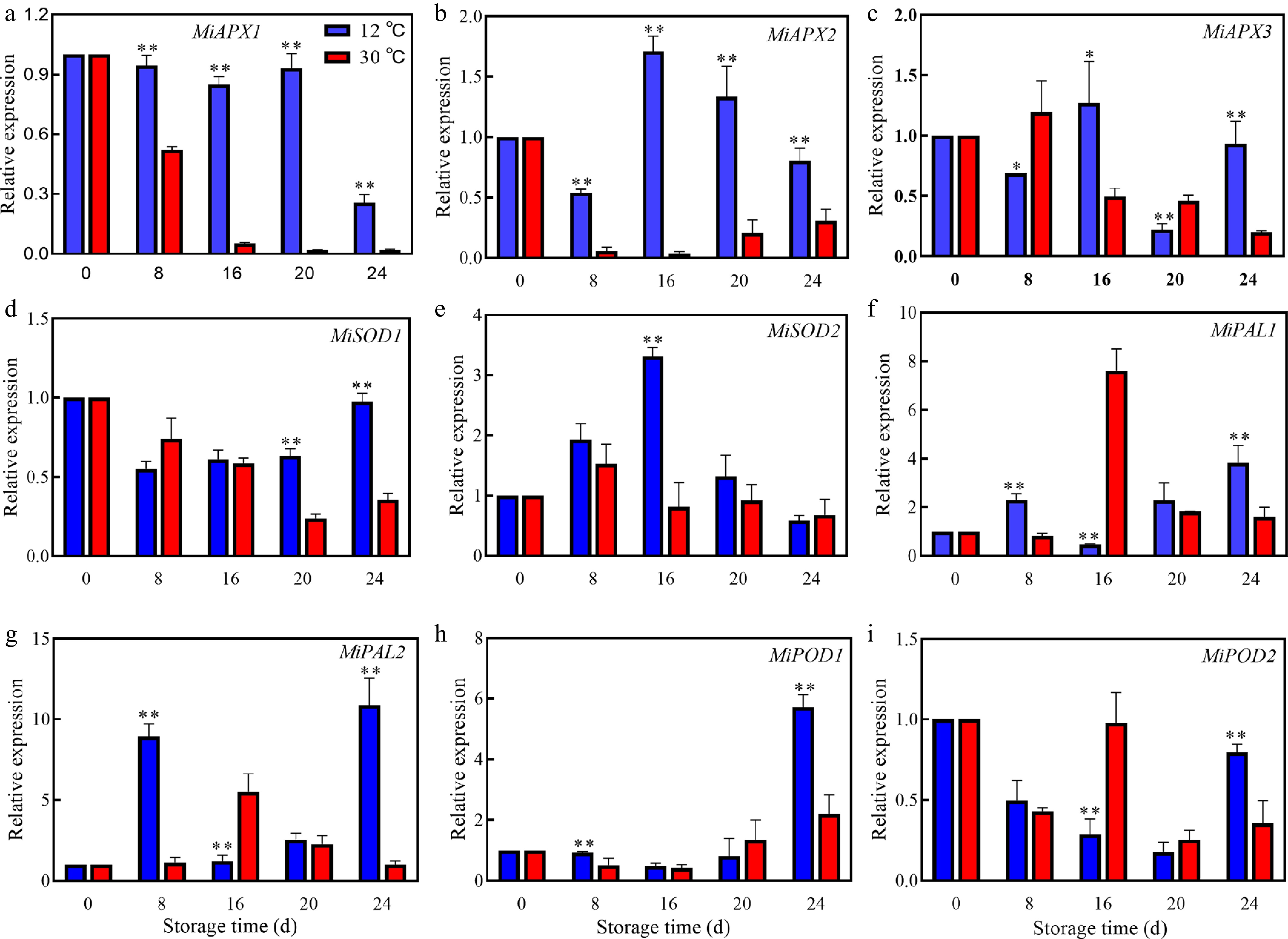

Comparative analysis of the transcriptional responses of mango fruits to different storage temperatures revealed that storage at 12 °C significantly upregulated the expression of MiAPX1 and MiAPX2, with minimal effects on MiAPX3 (Fig. 5a–c). Moreover, MiSOD1 expression at 12 °C was significantly higher than that at 30 °C on 20 and 24 d (Fig. 5d). Similarly, MiSOD2 expression was maximal on 16 d, with significantly higher levels observed at 12 °C (Fig. 5e) MiPAL1 expression at 30 °C peaked on 16 d followed by a decline, whereas MiPAL2 and MiPOD1 expressions at 12 °C were significantly higher than those at 30 °C on 8 and 24 d. MiPOD2 expression in mango at 12 °C reached its peak on 24 d.

Figure 5.

Changes in relative expressions of (a) MiAPX1, (b) MiAPX2, (c) MiAPX3, (d) MiSOD1, (e) MiSOD2, (f) MiPAL1, (g) MiPAL2, (h) MiPOD1, and (i) MiPOD2 of mangoes stored at 30 and 12 °C. Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean, the asterisks indicate significant difference between two groups at corresponding sampling point (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01).

Multivariate correlation analysis of postharvest physiology and antioxidant activity in mango fruit

-

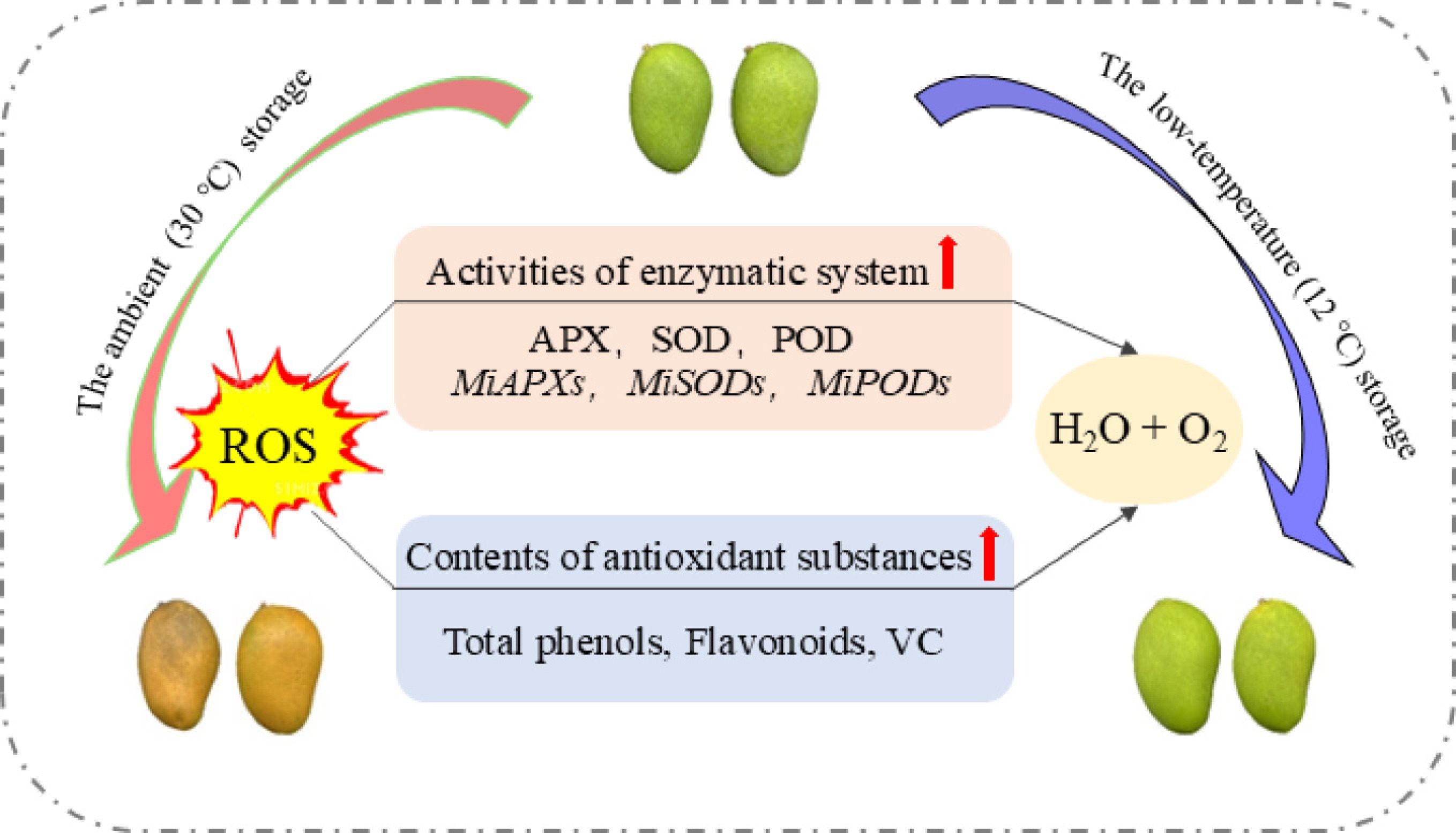

Correlation analysis analyzed the relationships between quality indicators, ROS accumulation, and enzyme activities (Fig. 6). Results showed that the weight loss rate negatively correlated with the firmness of postharvest mango. Vitamin C content was significantly negatively correlated with weight loss rate, CMP, Lab a* and b* (p < 0.05). Furthermore, O2− content was significantly correlated with weight loss rate and CMP. Similarly, MDA content was also significantly positively correlated with weight loss rate and CMP. However, O2− content was significantly negatively correlated with SOD, total phenols and flavonoids, but positively correlated with MDA content.

-

Low-temperature storage is regarded as an effective technique for preserving postharvest fruits and vegetables. Different mango varieties vary greatly in their sensitivity to low temperatures. For example, the critical storage temperature of Kent is 12.5 °C, while that of 'Keitt' is about 10 °C[5]. 'Alphonso' belongs to the low temperature-sensitive variety; its critical temperature of storage and transportation needs to be higher than 20 °C. Although the phenomenon of cold damage does not occur at 20 °C, fruit quality after returning to room temperature is still inferior to that of mango being preserved at room temperature[32]. In a study, low temperature (12 °C) can maintain mango quality from 0–24 d after harvesting, which suggests that 12 °C is a suitable storage temperature for 'Tainong No.1' mango.

Moreover, weight loss and texture were often used as the evaluation index of storage quality, and weight loss associated with fruit firmness during storage has received numerous reports[6]. In this study, low-temperature storage effectively reduced weight loss and respiration rates (Fig. 2c, d), and correlation analysis showed that weight loss rate negatively correlated with firmness of postharvest mango (Fig. 6), which was consistent with a previous report[33]. Moreover, overaccumulation of H2O2 and O2− can induce oxidative stress, which leads to senescence, browning, and disease development of postharvest fruit[9, 34]. In this work, low-temperature storage significantly reduced the contents of H2O2 and O2− (Fig. 3e, f), which contributed to preserving mango quality. Vitamin C can act as an essential antioxidant to scavenge excess ROS and mitigate oxidative stress[35]. Low-temperature storage in this study significantly enhanced vitamin C contents (Fig. 3b), which were consistent with the previous studies in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum)[34] and peach[36]. Additionally, the reduced ROS accumulation of mango stored at 12 °C also supported the decreased MDA content (Fig. 3a) and the structural integrity of pulp cells (Fig. 2a), suggesting that low temperature delayed lipid peroxidation and cellular aging in mango.

Plants have evolved a complex antioxidant system to scavenge excess ROS and counteract oxidative stress induced by ROS accumulation[37]. Previous reports have identified POD, SOD, PAL, and APX as crucial components of the antioxidant enzyme defense system, and they work together to balance ROS homeostasis of fruits and vegetables[38,39]. The antioxidant enzyme system directly scavenged ROS through enzymatic reactions, maintaining redox balance and delaying fruit senescence and disease development. For example, SOD maintains antioxidant balance by catalyzing electron transfer between metal ions and reduced states, thereby reducing oxidative stress and damage in fruits[40]. PAL regulates the phenylpropanoid metabolism pathway, producing secondary metabolites that help fruits cope with environmental stresses and improve quality[41]. APX is a crucial antioxidant enzyme in ROS metabolism and the ascorbate glutathione cycle, metabolizing H2O2 to reduce oxidative stress[42]. In this study, low-temperature storage significantly induced the activities of SOD, APX, and PAL in postharvest mango (Fig. 4a–c), which contributed to the remaining ROS homeostasis of mango. The above findings are consistent with the previous study[43], which demonstrated that treatment with M. guilliermondii enhanced antioxidant defense enzyme activity and reduced ROS accumulation, thereby improving disease resistance and antioxidant capacity in Broccoli (Brassica oleracea). These findings indicate that the coordinated action of these enzymes contributes to the antioxidant capacity of mango, highlighting the complex interplay between enzyme activity and antioxidant properties.

Enzyme synthesis and function are ultimately regulated by gene expression, which controls the transcription and translation of genetic information into functional enzymes[44]. Findings revealed that low temperature storage upregulated the expression of MiAPX1, MiAPX2, MiSOD1, MiSOD2, and MiPOD1, but downregulated the expression of MiPAL1 and MiPOD2 (Fig. 5). These findings are in agreement with the results in a previous report[45]. Additionally, PAL is a key enzyme in the phenylpropane metabolic pathway and flavonoid synthesis[46]. The downregulation of MiPAL1 and MiPAL2 expression (Fig. 5f, g), and subsequent decrease in PAL activity (Fig. 4c), might be responsible for the reduced accumulation of flavonoid and delayed color shift of 'Tainong No. 1' fruit[47]. However, the precise mechanisms by which individual enzyme genes influence enzyme function require further exploration.

In addition, correlation analysis revealed that both contents of O2− and MDA were significantly positively correlated with weight loss rate and CMP (Figs. 6 and 2c, e), suggesting ROS homeostasis plays a critical role in retention of postharvest mango quality. Not only SOD but also the content of total phenols and flavonoids were significantly negatively correlated with O2− content (Figs. 6 and 3e), indicating that both enzymatic and nonenzymatic systems participate in regulating ROS homeostasis in postharvest mango during the storage time.

-

In this study, the nutritional value of postharvest mango was maintained, and fruit ripening and senescence were delayed. Results showed that low-temperature storage induced the expression of antioxidant enzyme genes and enhanced the activity of defense enzymes. Moreover, accumulation of antioxidant substances, including Vitamin C, total phenols and flavonoids, were also significantly induced by low temperature storage, which contributed to regulating ROS homeostasis and reducing oxidative stress of postharvest mango. These findings demonstrate that low temperature is an effective method for extending the shelf life and maintaining the postharvest quality of 'Tainong No.1' mango.

This research was funded by the Hainan Province Agricultural Reclamation Team Joint Innovation Project (Grant No. HKKJ202432), the National Key Research and Development Program Project (Grant No. 2023YFD2300803–7), and Hainan University Mango Industry Technology System Construction Project.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: methodology: Wang X, Gong Y; investigation: Li J; formal analysis: Li J, Gao Y, Zeng S; software: Li J; data curation: Li J; data analysis: Gong Y; validation: Gao Y, Wang X; visualization: Ma D; draft manuscript preparation: Li J; writing−review and editing: Li W; supervision: Zeng S, Ma D, Shao Y, Li W; funding acquisition: Li W. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Received 26 October 2025; Accepted 16 December 2025; Published online 28 January 2026

-

Storage at Low temperature effectively preserved the postharvest quality and cellular morphological stability of 'Tainong No.1' mango.

Low temperature significantly enhanced the activities of antioxidant enzymes in mango, with induced expression of corresponding enzyme genes.

SOD, total phenols and flavonoids were identified as the main factors balancing ROS homeostasis in postharvest mango under 12 °C storage.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li J, Gao Y, Wang X, Zeng S, Ma D, et al. 2026. Low temperature mitigates mango quality deterioration by improving antioxidant ability and gene expression levels. Tropical Plants 5: e001 doi: 10.48130/tp-0025-0034

Low temperature mitigates mango quality deterioration by improving antioxidant ability and gene expression levels

- Received: 26 October 2025

- Revised: 01 December 2025

- Accepted: 16 December 2025

- Published online: 28 January 2026

Abstract: Mango (Mangifera indica) is a tropical, climacteric fruit with unique flavor and rich nutrition, but its postharvest shelf life is limited due to softening, rotting, and cold damage susceptibility. Recent research indicates that storage at 12 °C can preserve mango fruit well, but the underlying preservation mechanism remains poorly understood. In this study, postharvest quality changes and antioxidant mechanism of 'Tainong No.1' mango stored at 12 and 30 °C with 90% ± 5% RH for 24 d were explored. The results showed that, compared with storage at 30 °C, storage at 12 °C significantly maintained fruit firmness, while reducing weight loss rate and malondialdehyde (MDA) content. Better cell morphology and delayed starch degradation were found at 12 °C through microscopic analysis. Moreover, the mango fruit stored at 12 °C showed significantly enhanced activities of antioxidant enzymes, including peroxidase (POD), superoxide dismutase (SOD), phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX). Induced expressions of enzyme genes supported the corresponding enhanced enzyme activities. Furthermore, correlation analysis demonstrated that SOD, total phenols, and flavonoids might have a greater contribution to balancing the ROS homeostasis of postharvest mangoes. These findings suggest that storage at 12 °C might maintain mango quality and prolong the storage period by regulating fruit antioxidant capacity.

-

Key words:

- Mango /

- Fruit quality /

- Antioxidant enzymes /

- Cold chain /

- ROS