-

Vitreoretinal surgery is a common procedure for treating various vitreoretinal diseases, including retinal detachment, proliferative diabetic retinopathy, and macular holes. An intraocular tamponade, such as silicone oil or gas, is often used to facilitate the sealing of retinal breaks and provide support to the retina[1]. The tamponade bubble has low density and high surface tension in the vitreous cavity[1]. These properties prevent the tamponade from inflowing into the subretinal space through retinal breaks, while allowing it to float in the vitreous cavity. This results in upward pressure on the retina, and acts as a barrier between the retinal break and vitreous fluid[2]. However, the tamponade may not completely occupy the entire vitreous cavity. Therefore, special postures (e.g., prone, lateral recumbent, and Fowler's posture) are required after the operation to ensure the contact between the intraocular tamponade and the retinal breaks[3−9]. This contact facilitates the closure of the retinal breaks, prevents complications, and enhances the success of vitreoretinal surgery[4,10−12]. The duration of the posture may range from several days to months, posing significant challenges to patient compliance. Studies have reported that patients can only maintain the target posture without intervention 10%–40% of the time[13]. Therefore, improving patients' compliance is essential.

Several devices have been developed to monitor and improve patient's compliance with keeping specific postures. Some studies have focused on detecting posture[8,13−18]. Others have developed systems to provide audio and visual feedback on a smartphone when deviations from the target posture are detected[19,20]. Dimopoulos and colleagues integrated audio and vibratory feedback with a sensor and demonstrated that this feedback improved patient compliance[21]. However, the temporal change in compliance over time and the spatial distribution of posture deviation remain poorly understood[21].

In the current study, we developed a comprehensive hardware–software system that integrates posture monitoring, alerting, setting customization, data transfer, and data analysis. We assessed the system's efficiency in improving patients' compliance, explored the temporal patterns of compliance, and analyzed the spatial distribution of posture deviations.

-

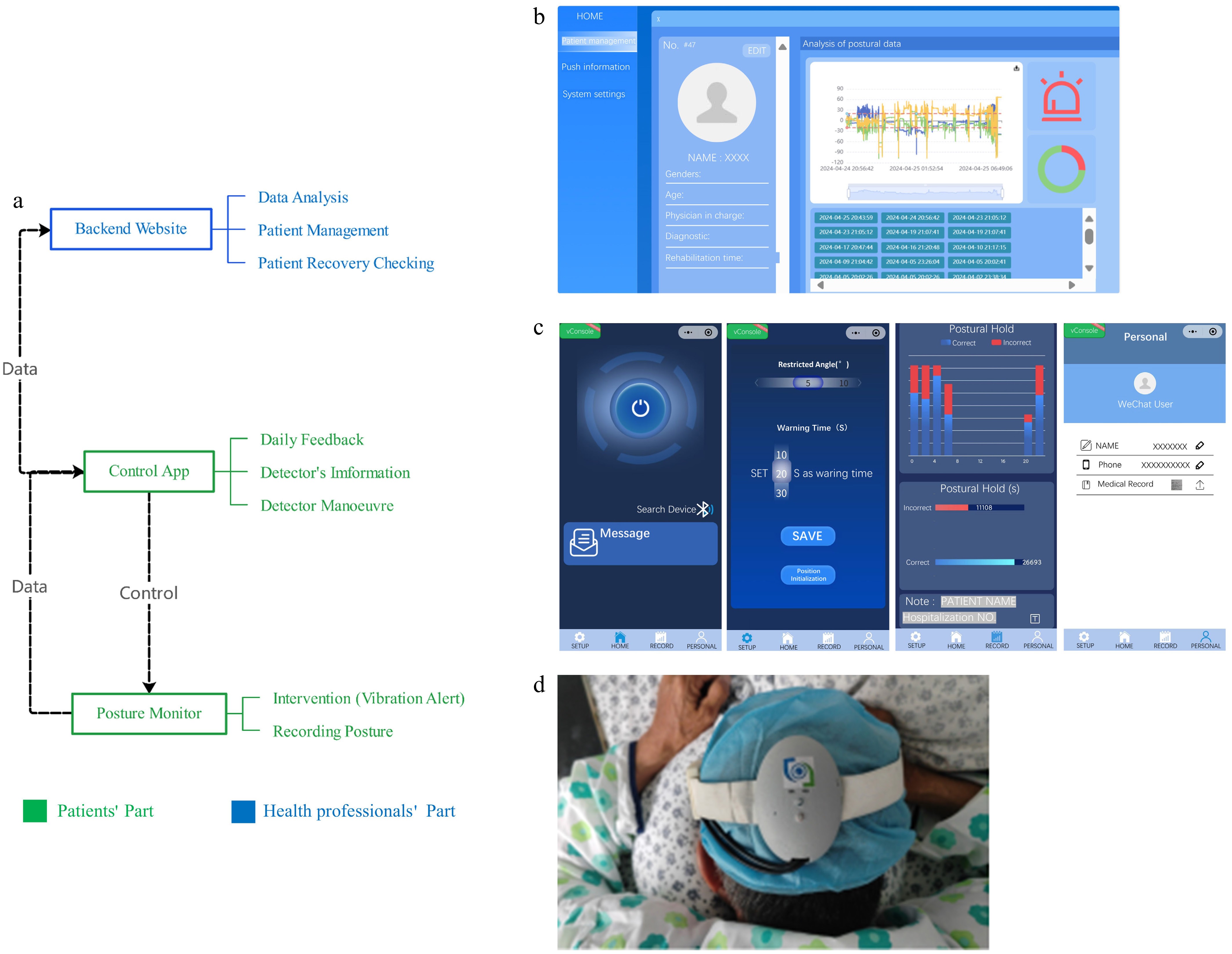

We developed a comprehensive system comprising a posture monitor, an applet on a smartphone, and a backend website (Fig. 1). The posture monitor records three-axis posture angles (°) per second and provides vibration alerts to the user. The applet allows the users to: (1) set the target posture, tolerance angle (°), and tolerance time deviation(s) from the target posture; (2) download the data from the monitor and upload the data to the backend website; and (3) provide the user with the results of his/her compliance within a timeframe. The backend website aggregates the data from individual patients, enabling health professionals to identify the patients with poor compliance for targeted intervention. Both the website and applet were password-protected to ensure patients' privacy.

Figure 1.

Head posture monitoring system's architecture. (a) System overview. The posture monitor was controlled by the app. The posture data are transferred to the app, which uploaded it to the backend website. (b) The backend website provides basic information and the posture compliance data of each patient for health professionals. (c) The control app controls the monitor, sets the target posture, and demonstrates the compliance results for each session. (d) The head posture monitor can detect posture and provides vibration alerts.

Experiment

-

We recruited inpatients who had undergone vitreoretinal surgery with intraocular tamponade and required specific postoperative postures. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Joint Shantou International Eye Center, Shantou University and the Chinese University of Hong Kong (EC20200609(6)-P10). All participants provided informed consent before enrollment. We collected demographic (e.g., age, gender) and clinical data (e.g., diagnosis, type of intraocular tamponade, and target posture) from each patient.

The patients' target posture was determined on the basis of whether retinal breaks could be covered by the tamponade. In this study, the patients' target postures included the prone and Fowler's postures. In Fowler's posture, the patient is kept at 45° dorsal elevation, using Fowler's beds. In prone posture, the direction of the patient's eyeball is 90° downward from the horizontal line, assisted by prone position cushions.

Patients received instructions from a physician on maintaining the target posture using the posture monitor. The posture monitor was set to alternate between alert-on and alert-off periods every 30 min. Patients were unaware of the alert's alternation. During alert-on periods, the posture monitor triggered a vibration alert if the head deviated from the target range, which was more than 30° from the target posture for over 20 s, and it continued to vibrate until the target range was resumed[13]. During alert-off periods, the posture monitor recorded the patients' posture but did not issue any alerts.

Patients wore the posture monitors for 7 h during the daytime, or continuously from going to bed until morning awakening during the nighttime.

Data analysis

Selection of study data and calculation of compliance

-

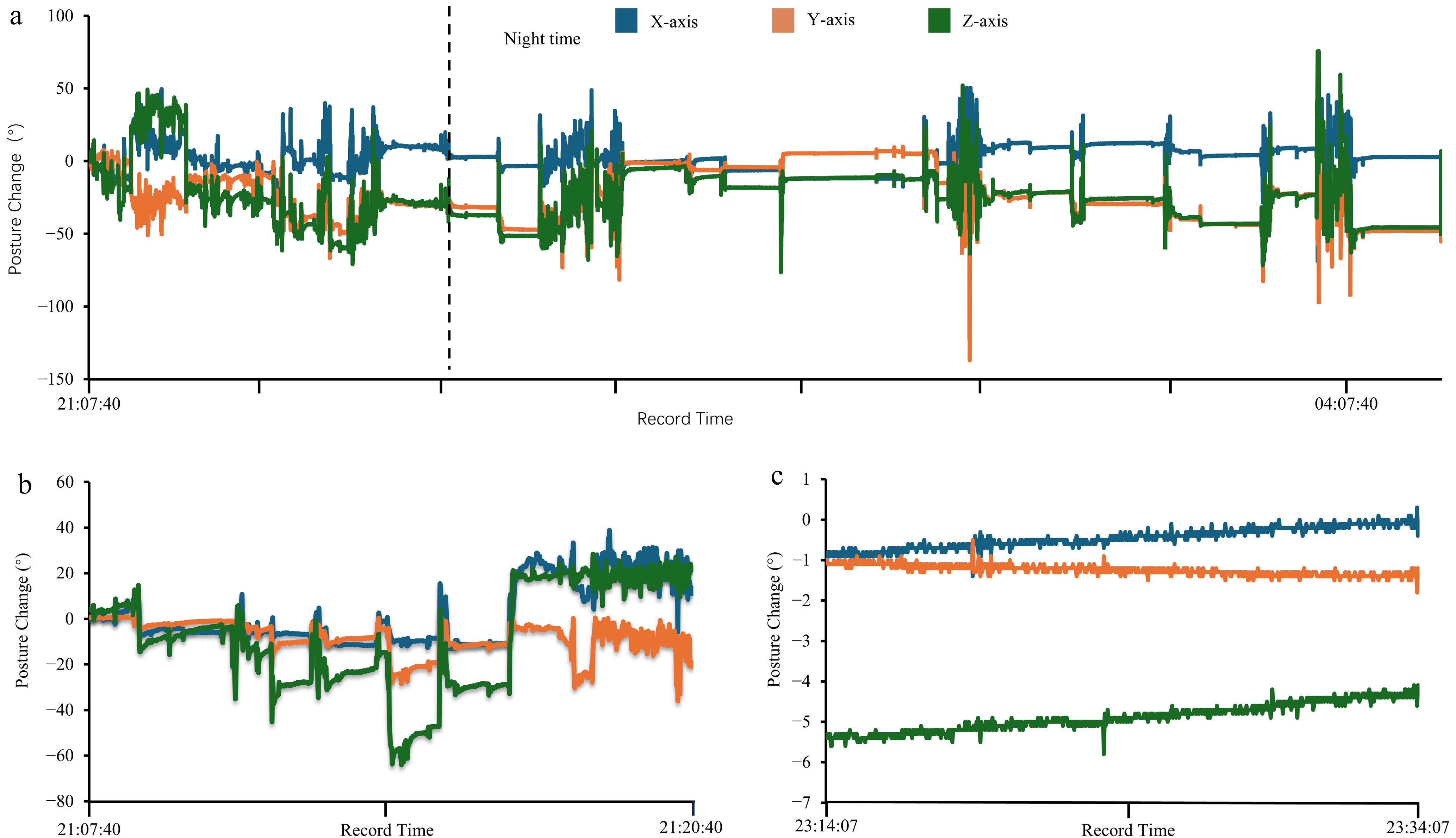

Data were analyzed by selecting six consecutive hours. In the nighttime, the start of nighttime was defined as the time when the patients' posture changed within 2° in 20 min (Fig. 2). Compliance was quantified as the proportion of time with posture in the target range within a given timeframe. Hourly compliance improvement was defined as the difference in compliance between the alert-on and alert-off periods within the same hour.

Figure 2.

(a) An example of three-axis posture angles changes over time at night. The dashed line indicates the start of the selected nighttime data. (b) Unstable posture angles with maximum change > 100°. (c) Stable posture angle with changes in all three axes < 2°.

Analysis of compliance

-

Independent samples t-tests were used to compare the compliance in patients with different genders and postures. Spearman's rank correlation was conducted to assess the relationship between age and compliance.

Paired t-tests were conducted to compare the compliance during alert-on and alert-off periods. Moreover, we used linear regression to analyze the relationship between hourly compliance improvement and compliance during the alert-off period. Furthermore, the average compliance of patients with its standard deviation was plotted over time for different postures.

Spatial distribution of patients' postural deviation

-

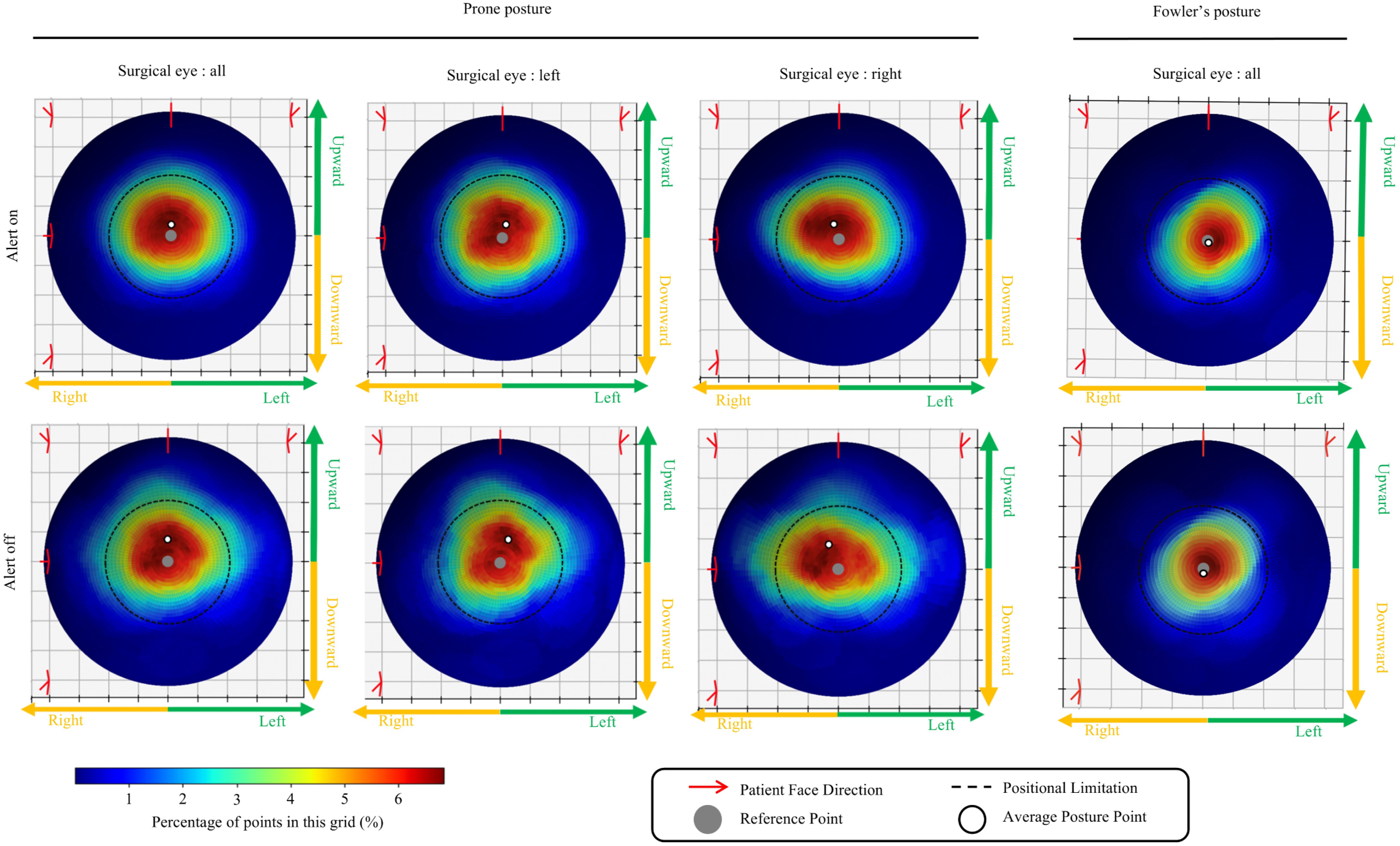

We used Python to create a heatmap to visualize the spatial distribution of patients' posture deviations. This allowed for an analysis of the head tilt trends during posture maintenance. The heatmap was created from data for every second from the posture monitor (Fig. 3). We also analyzed the average vector of the deviation and displayed it on the heatmap. The data from the alert-on and alert-off periods were analyzed separately. For patients with prone posture, the left eye and right eyes were calculated separately.

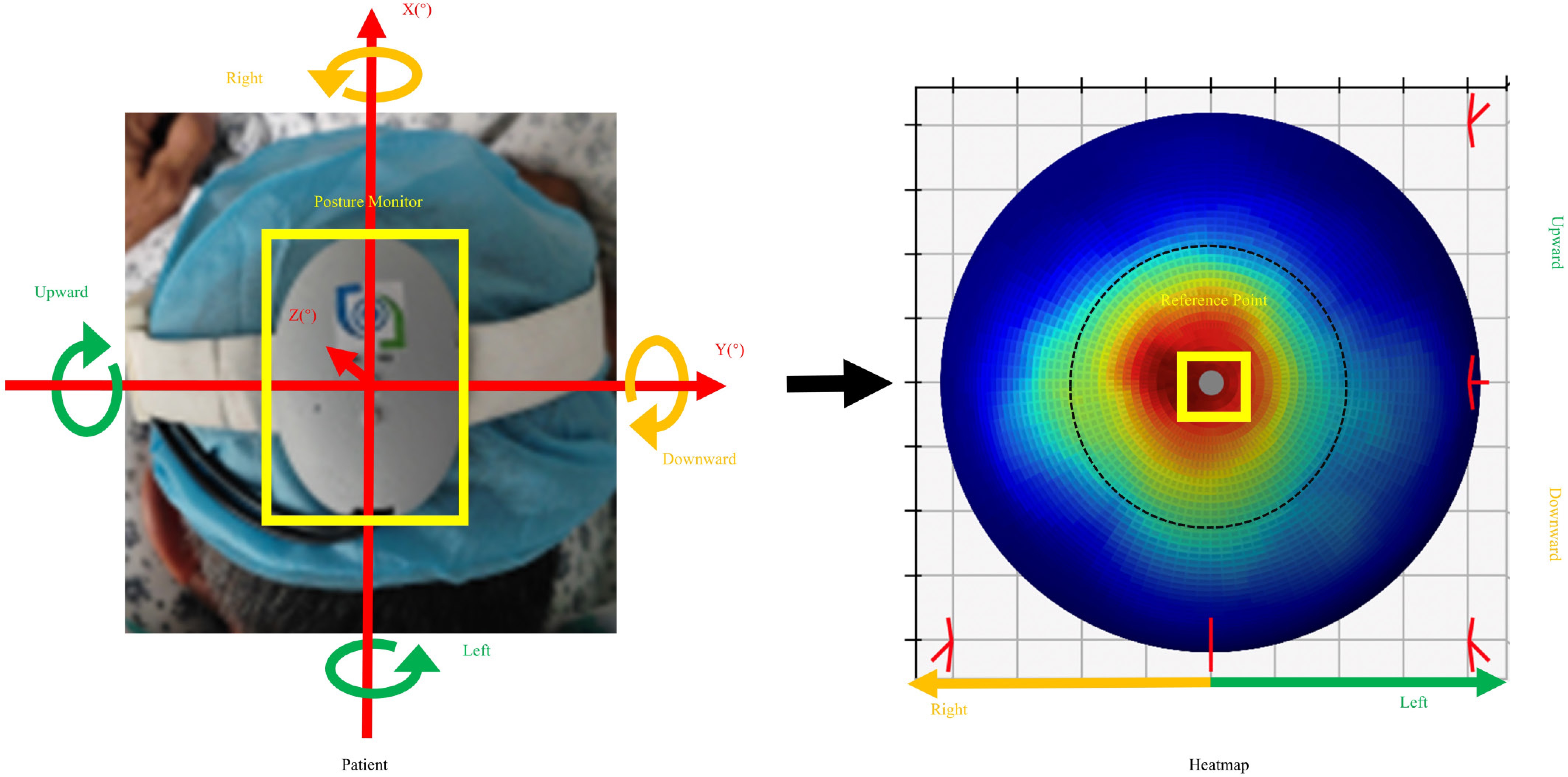

Figure 3.

Direction of the heatmap corresponding to the patient's posture. The posture data on the angle and direction of rotation along the axis were projected onto a spherical surface as a point. The distribution of posture data for each second generated a heatmap. The reference point indicates the original posture.

-

We excluded eight patients because they took off the posture monitor during the experiment. Therefore, the final analysis included 47 patients. Of these, 26 patients wore the posture monitor during the daytime, while 21 wore it at night. The target postures included prone posture in 38 patients and Fowler's posture in nine patients (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the included patients

Day Night Age Median (min, max) 65 (25, 70) 62 (17, 75) Gender Male/female 17/9 8/13 Tamponade Air/C3F8/silicon oil 4/7/15 5/8/9 Body position Prone/Fowler's 21/5 17/4 Patients' compliance

-

There was no significant difference in compliance between males and females (0.789 ± 0.107 vs 0.796 ± 0.140, respectively, p = 0.870), nor a significant correlation between age and compliance (r = 0.043, p = 0.767). Compliance was higher for patients with Fowler's posture compared with those in prone posture (0.927 ± 0.904 vs 0.760 ± 0.106, p < 0.001).

Efficiency of alert on compliance

-

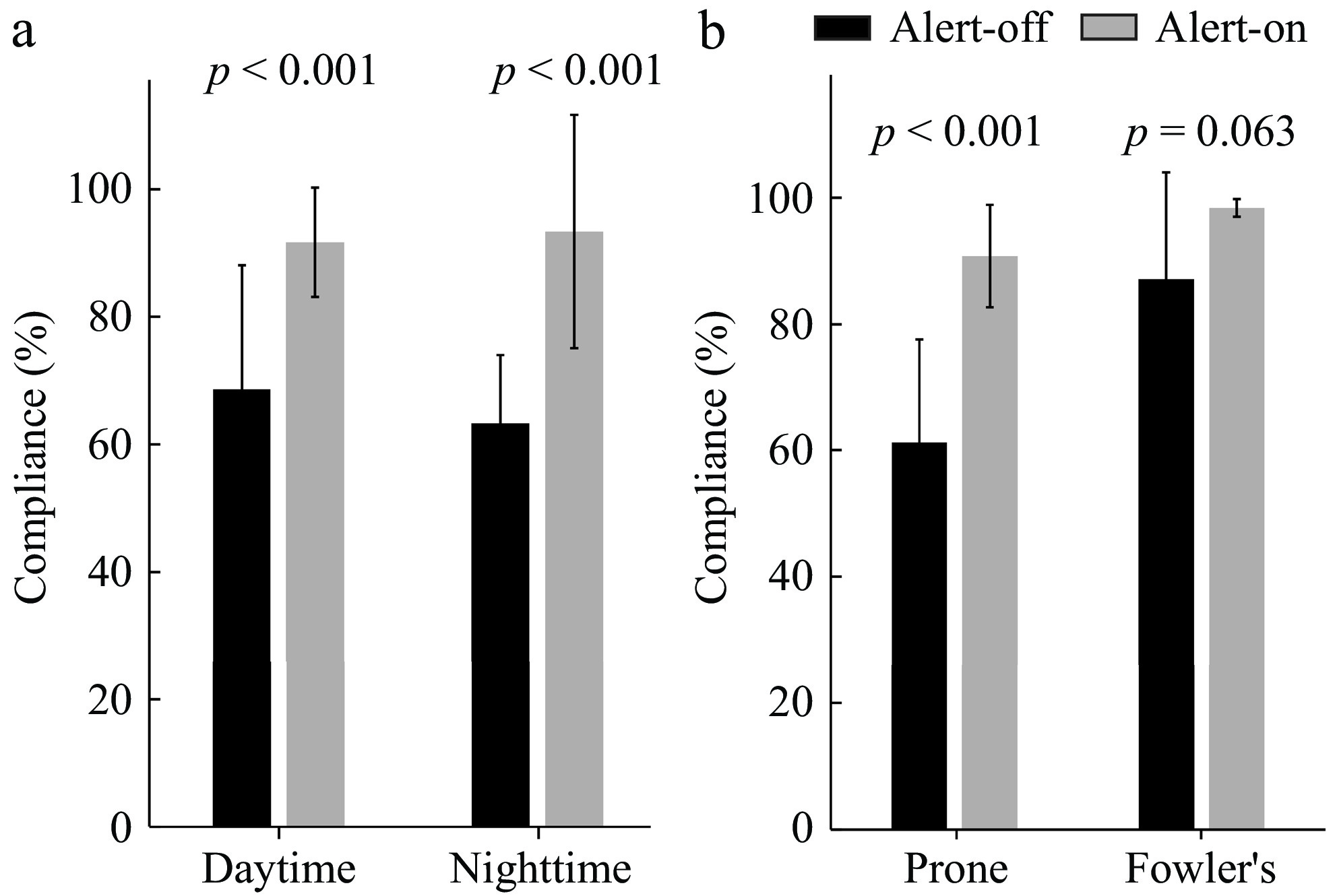

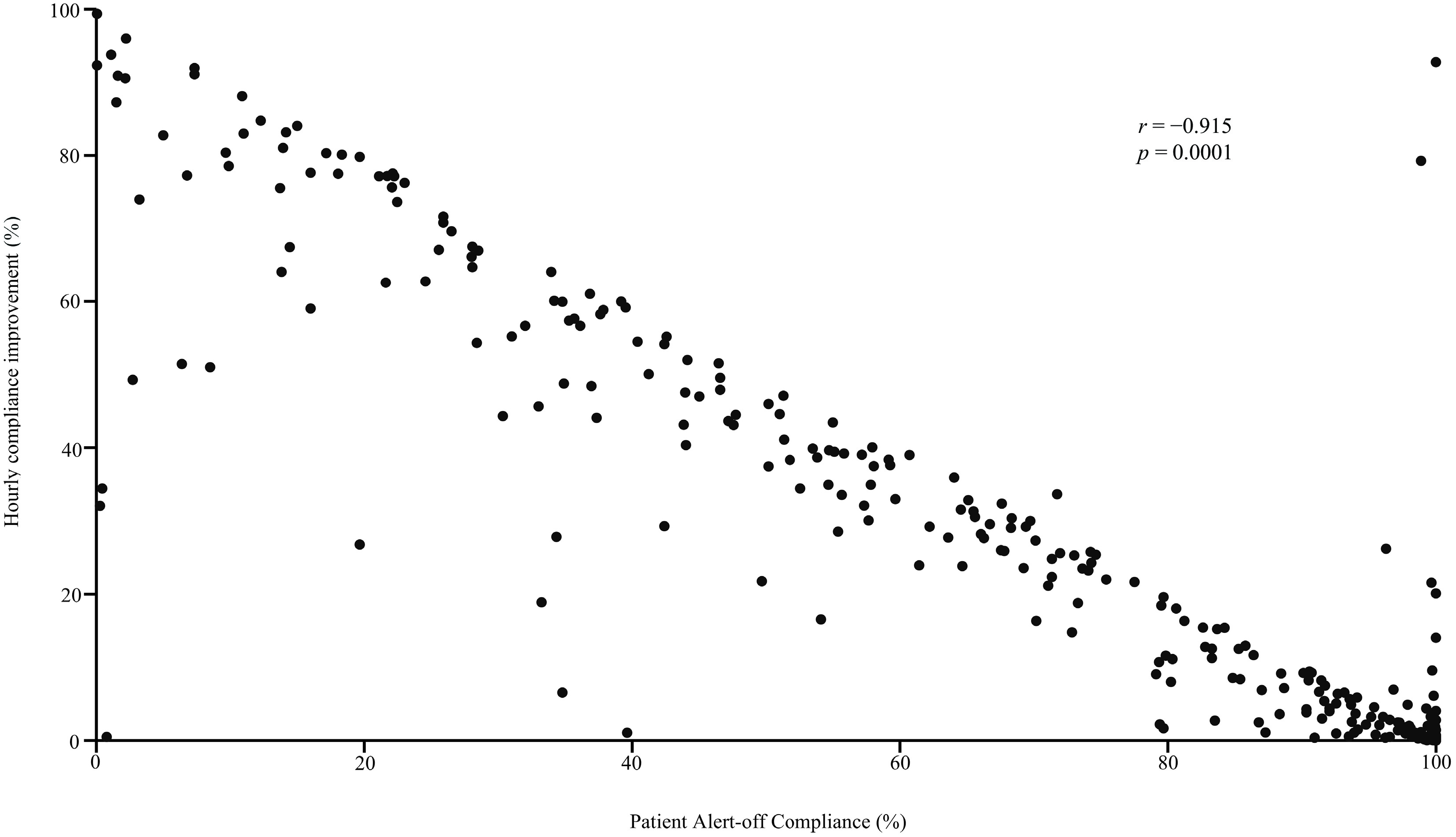

Significant improvements in compliance were observed during alert-on periods compared with alert-off periods, during both daytime (from 0.686 ± 0.198 to 0.916 ± 0.085, p < 0.001) and nighttime (from 0.631 ± 0.109 to 0.930 ± 0.186, p < 0.01) (Fig. 4). There was no statistically significant difference between daytime and nighttime compliance (p = 0.733 and 0.378 for alert-off and alert-on periods, respectively). Compliance improved for both prone and Fowler's posture, although the difference did not reach statistical significance in Fowler's posture (Fig. 4). Furthermore, there was a significant negative correlation between patients' compliance during alert-off periods and the hourly compliance improvement (r = −0.915, p < 0.001), indicating that patients with lower initial compliance showed greater improvement (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Patient's compliance was higher in the alert-on period compared with the alert-off period during both daytime and nighttime (a), and for both prone posture and Fowler's posture (b), although the difference for Fowler's posture did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 5.

Scatter plot showing statistically significant correlations between hourly compliance improvements and patient compliance in the alert-off period.

Change in compliance with time

-

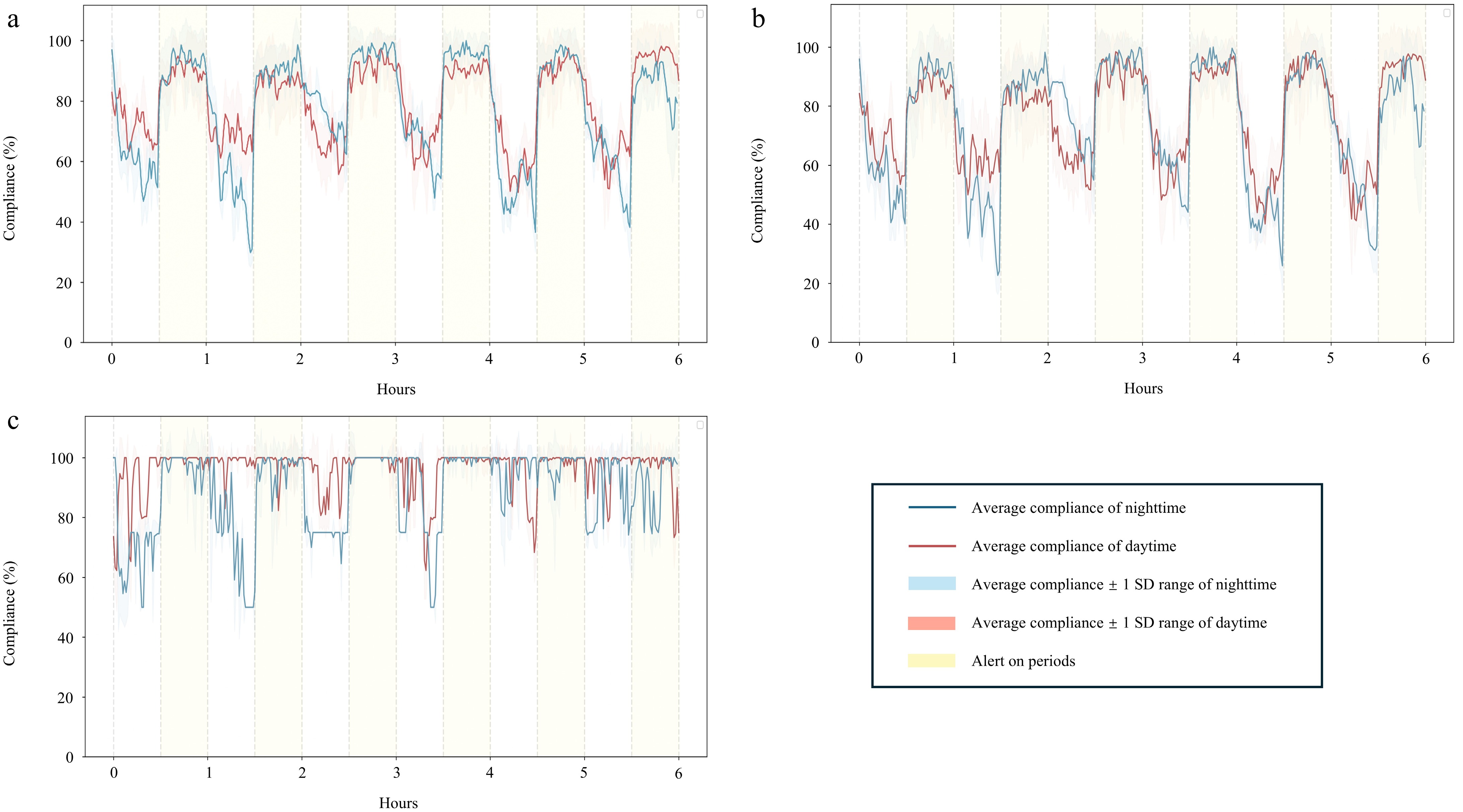

The changes in average compliance with time are shown in Fig. 6. Generally, compliance was lower during the alert-off periods compared with the alert-on periods. Compliance in Fowler's posture reached nearly 100% during alert-on periods.

Figure 6.

Patient's average compliance over time. (a) All postures. (b) Prone posture. (c) Fowler's posture. The alert-on periods are marked in yellow.

Direction of postural deviation

-

The heatmap analysis of patients in the prone position is shown in Fig. 7. The average deviation in the sagittal plane was upward, regardless of whether the left or right eye was operated on. However, in the horizontal plane, the average deviation was to the left when the left eye was operated on, and to the right when the right eye was operated. The average deviation during alert-on periods was less compared with alert-off periods, although the direction of deviation was similar. In contrast, there was no significant head tilting observed in patients with Fowler's posture (Fig. 7).

-

In this study, we developed a comprehensive hardware–software system to improve compliance in patients with intraocular tamponade. Our findings demonstrate that the vibration alert significantly enhanced compliance, particularly in patients with lower initial compliance during alert-off periods. This improvement was observed in both daytime and nighttime, and for both prone and Fowler's postures. The direction of deviation was upward and toward the operated eye in the prone posture, but no specific directional trend was observed in Fowler's posture.

The contact of intraocular tamponade is important for the preventing fluid entering the subretinal space through retinal breaks, which is crucial for the success of vitreoretinal surgery[4,10−12]. Maintaining a specific posture enables the tamponade to exert its tamponade effect and aid in retinal reattachment, with longer periods of posture maintenance leading to better prognoses. Patients with higher compliance can maintain the specific posture for longer periods, thus achieving better prognoses[22]. The result of current study suggest that our system may help to improve the outcome of patients with intraocular tamponade.

When patients deviate from the prescribed posture, timely intervention through vibration alerts can effectively improve compliance. This is consistent with the finding of Dimopoulos et al., who observed that sound and vibration alerts can play a significant role in improving patient adherence[21]. However, sound alerts may be less effective in elderly patients due to age-related hearing loss. Additionally, setting sound alerts at a sufficiently loud volume to be heard by elderly patients would increase power consumption, thereby reducing the operational time of the posture monitor. Furthermore, sound alerts can also cause unnecessary disturbance to other patients in the same ward[23]. In contrast, vibration alerts offer several advantages, including lower power consumption and reduced sensitivity to environmental factors or hearing impairments.

Patients in Fowler's posture demonstrated higher compliance compared with those in prone posture. This may be attributed to the inherently more comfortable nature of Fowler's posture, which allows for better adherence even without alerts. The vibration alerts further contributed to more consistent posture maintenance, as evidenced by a reduced standard deviation in compliance. In contrast, compliance in the prone posture exhibited greater fluctuations across both the alert-on and alert-off periods.

To understand the instability observed in the prone posture, we explored the underlying factors. Previous studies using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have shown that patients in the prone position often tend to raise their heads[24]. Our study also revealed that patients not only raised their heads but also turned them in the opposite direction from the surgical wound. This behavior suggests that patients instinctively attempt to prevent potential compression on the surgical eye. While vibration alerts can improve compliance, additional measures such as using an eye shield to protect the surgical eye and instructing patients to avoid lateral head tilting may further reduce deviations[4,6,25].

Several limitations of our study need to be acknowledged. Firstly, the observation period was limited to 6 hours, which may not fully capture the long-term effectiveness of the intervention. Future studies should investigate the efficiency of the system over extended periods. Secondly, our results are based on data from a single center. Conducting multi-center trials will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the system's efficacy across diverse patient populations.

-

We developed a posture monitor system that significantly improves compliance in patients with intraocular tamponade. Compliance was not affected by patients' sex or age but was lower in prone posture compared with Fowler's posture. The direction of deviation in prone posture was predominantly upward and toward the operative eye. Vibration alerts significantly enhanced patient compliance and reduced posture deviations. Future work will focus on long-term studies and multi-center trials to further validate the system's effectiveness.

-

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Joint Shantou International Eye Center, Shantou University and the Chinese University of Hong Kong (EC20200609(6)-P10). All participants provided informed consent before enrollment.

This study was supported in part by Department of Education of Guangdong Province (2024ZDZX2024), Shantou Science and Technology Program (200629165261641), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2025A1515011204), and Guangdong Students' Platform for Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training program. The authors would like to thank all patients who were involved in the project.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Ou S, Yang N, Chen H; hardware: Zhang D, Ye W; software: Zhu Z, Tang L; data collection: Liao X; analysis and interpretation of results: Ou Y, Zhu Z, Zhang D, Ye J, Zhang R; literature search: Chen Y, Yu S; draft manuscript preparation: Ou Y, Zhu Z, Chen H. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ou Y, Liao X, Zhu Z, Zhang D, Chen Y, et al. 2025. Monitoring and improvement of posture compliance in patients with intraocular tamponade. Visual Neuroscience 42: e014 doi: 10.48130/vns-0025-0014

Monitoring and improvement of posture compliance in patients with intraocular tamponade

- Received: 13 May 2025

- Revised: 23 June 2025

- Accepted: 01 July 2025

- Published online: 11 August 2025

Abstract: Vitreoretinal surgery usually utilizes intraoperative tamponade agents to seal retinal breaks, which requires patients to maintain specific postures postoperatively. This requirement poses challenges to patient compliance. We developed a device for monitoring and intervening in posture maintenance. The purpose of this study was to investigate the efficiency of this system in improving patients' compliance with specific postures. Forty-seven patients wore the device for 6 h. During each hour, patients received a vibration alert when the posture was out of the target range in 30 min, with the alert off in the remaining 30 min. Compliance was quantified as the percentage of time with the posture in target range within a given timeframe. The factors affecting compliance were further explored. We recorded patients' posture and analyzed head-tilting tendency using heatmaps. The compliance in the alert-on and alert-off periods was compared. The compliance was not affected by sex or age. Patients in Fowler's posture exhibited higher compliance compared with those in prone posture. The deviation in prone posture was predominantly upward and toward the operative side. The compliance was 0.686 during the day and 0.631 at night in alert-off mode and improved to 0.916 and 0.930 with the alert, respectively (both p < 0.01). Patients with lower initial compliance (p < 0.001) had more compliance improvements. The device efficiently monitors and improves posture compliance in patients with intraocular tamponade.

-

Key words:

- Devices /

- Vitreoretinal surgery /

- Posture compliance /

- Prone posture /

- Fowler's posture