-

In daily life, individuals constantly get visual information from the environment. When a stimulus is seen, visual perception is quickly formed to enable easy recognition of this stimulus, such as its color, form, and the object category it belongs to. It is well known that this perceptual knowledge is represented in the ventral occipito-temporal stream of the human brain[1]. Although visual perception allows for the identification of a stimulus, it also plays a role in guiding appropriate responses to it[2,3]. For instance, when a person sees a cup with a right-facing handle, it would naturally occur to them to take it with the right hand. This notion is supported by both behavioral and neural evidence that viewing a cup with a right-facing handle was accompanied by facilitated responses at the right hand[4] and the activation of the motor areas in the left hemisphere[5,6].

The conjunctive involvement of the visual system and the motor system in the encounter of a visual stimulus manifests in the way that both systems are commonly modulated by reward, an important reinforcer in shaping human cognition[7]. A great number of studies have shown that the visual representations[8−10] and the motor activations[11−13] related to a stimulus were modulated by reward. For instance, on one aspect, Hickey & Peelen showed that the neural representation of a specific visual category in the ventral visual cortex was enhanced when this visual category was followed by high-reward feedback relative to when this same category was followed by low-reward feedback[8]. On the other aspect, a lateral visual stimulus associated with high reward induced stronger neural activity in the motor cortex contralateral to the stimulus location than a stimulus associated with low reward[12].

Despite the common observation of the reward modulation on the visual representation and the motor activation of a visual stimulus, the visual components and the motor components in previous studies were often treated in isolation. It thus remains unclear if and how the visual components link to the motor components. One hypothesis is that selective visual processing and motor activation are simultaneously elicited by the encounter of the stimulus[14], and these two processes are modulated by reward in parallel. Another hypothesis is that reward improves the visual analysis of the stimulus at an earlier stage and transforms the action-relevant perceptual information into the motor system to facilitate the action selection[15]. A third hypothesis, although not exclusively alternative to the second hypothesis, is that reward enhanced the proactive preparation of the multiple motor candidates earlier before the visual analysis. The relevant information from the visual analysis would be integrated to resolve the competition between the motor activations and facilitate the action selection[16,17].

In the present study, three hypotheses were tested in a visual perceptual discrimination task with a reward context. A visual cue was first presented to indicate whether the current trial would result in a monetary reward or not (reward vs no-reward). After a period, a visual form was presented as the target, and the head of the form pointed to the left or right direction. A response at the left hand had to be made given a left-pointing form, and a response at the right hand had to be made given a right-pointing form. It was predicted that the performance of the visual discrimination would be improved in the reward condition relative to the no-reward condition. Electroencephalography (EEG) signals were recorded to reveal how the neural activities over the motor cortex and the visual cortex would be affected by reward over time. According to the first hypothesis, the motor cortex and the visual cortex would show a similar pattern of selective processing. Specifically, as an index of selective processing of the target, the activity difference between the contralateral and the ipsilateral sides of the target direction over both the visual cortex and the motor cortex would be modulated by reward, and the reward modulations would be observed in the same time range. According to the second hypothesis, the selective processing of the target and the reward modulation would be observed earlier over the visual cortex than over the motor cortex. The prediction of the third hypothesis differs from the second hypothesis in the way that the motor activities, both contralateral and ipsilateral to the target direction, would be proactively activated and enhanced by reward. The selective processing in terms of the difference between the contralateral and the ipsilateral sides would be observed after the proactive motor activations.

Previous studies have documented several well-known components of event-related potentials (ERPs) concerning the discriminative processing of visual stimuli. For instance, N1, the negative activity that peaked around 100 ms after stimulus onset, was taken as reflecting the early sensory discrimination of the visual stimulus[18]. N2pc, the negative activity that emerged around 200 ms over the posterior cortex, was identified by contrasting the activities between the contralateral and the ipsilateral side of the lateral stimulus. This component was taken as reflecting the selective attention to the visual stimulus[19]. The lateral readiness potential (LRP) was identified by contrasting the activities between the contralateral motor cortex and the ipsilateral motor cortex to the responding hand and was taken as reflecting the response preparation for the target. Importantly, the N2pc was shown earlier and with higher amplitudes for high-reward targets compared to low-reward targets in a visual search task[20]. The LRP exhibited higher amplitudes when the visual target contralateral to the responding hand was associated with high reward than when the target was associated with low reward[12]. Here, it was expected that one or more of the components would be modulated by reward.

-

The required sample size was estimated with G*Power 3.1[21] based on the statistics of an earlier study that similarly used a reward-driven visual task with EEG recording[20]. Given the reported effect size of the reward modulation (Cohen's d = 1.3), a minimum sample size of 13 participants was required to achieve a power of 99%. To avoid potential dropout or potential exclusion due to poor data quality, 20 university students (age range: 19−26 years; mean age: 21.4 years; 14 males) were recruited for the study. All participants were right-handed, with normal or corrected-to-normal vision. None of the participants reported any history of psychiatric or neurological disorders. Informed written consent was obtained from each participant before the experiments. No participant was excluded from the data analysis.

Design and procedures

-

Participants were seated in a dimly-lighted, sound-attenuated, temperature-controlled room, with their heads stabilized in a chin rest. The eye-to-monitor distance was fixed at 57 cm. Stimuli were presented on a black background of a computer screen, with a refresh rate of 100 Hz. Responses were collected with a standard keyboard.

Each trial started with a white fixation dot at the center of the screen. Participants were asked to maintain eye fixation on the dot without making eye movements throughout every trial. The duration of this fixation dot was jittered from 400 to 1,200 ms. Then, a visual cue (3° × 3° of visual angle) was presented at the center of the screen for 100 ms, indicating whether current trial was a reward trial or a no-reward trial. In a reward trial, the visual cue was an image of a 1-Yuan coin (RMB, 1 Yuan ≈ 0.15 US dollar); in a no-reward trial, the cue was a visual mask of the same shape. After the presentation of the cue, the fixation dot was presented for a varying interval randomly chosen from 200 to 1,100 ms (in a step of 100 ms), preventing the prediction of the target onset. Then, the target was presented at the center of the screen for 100 ms. The target was an arrow-like pentagon (4° × 2°), with the head pointing to the left or the right. Participants were asked to discriminate the head of the arrow by pressing the 'F' key in the left direction with the left index finger or the 'J' key in the right direction with the right index finger. After the presentation of the target, the fixation dot was presented for 900 ms, and the response given between the onset of the target and the offset of this fixation dot was identified as a valid response. Responses given outside this time window were identified as omissions. Participants were instructed to respond as accurately and quickly as possible. Inter-trial-interval was a blank screen of 800 ms. Feedback was not presented during each trial, and participants were informed that only a correct response given within the time window would be counted for reward. They were informed that the received reward in each trial would be accumulated throughout the experiment, and the accumulated reward would be proportionally exchanged for the actual payment.

There were 400 trials in each of the reward and no-reward conditions, rendering 800 trials in total. The trials were mixed and separated into four blocks of equal length and with equal probabilities of the two conditions in each block.

Participants were informed that a correct and quick response in each reward trial would gain ten points, and the points would be accumulated during the experiment. The total points after the experiment would be proportionally exchanged into money (RMB, 100 points = 1 Yuan) and added to the payment for participating in the experiment. Participants were asked to respond as accurately and quickly as possible in each trial, irrespective of the two conditions.

EEG recording and preprocessing

-

EEG data were recorded using 64 Ag-AgCl scalp channels placed according to the International 10−20 system (Brain Products GmbH, Munich, Germany; passband: 0.01−100 Hz; sampling rate: 500 Hz). The nose tip was used as the reference channel, and all channel impedances were kept below 5 kΩ. To monitor ocular movements and eye blinks, electro-oculographic (EOG) signals were simultaneously recorded using two surface electrodes: vertical EOG was placed over the right eye, and horizontal EOG was placed 1 cm lateral to the outer canthus of the right eye.

EEG data were processed using EEGLAB[22] in the MATLAB (MathWorks) environment. Continuous EEG data were high-pass filtered above 1 Hz and low-pass filtered below 30 Hz. Eye blinks and movements were corrected using an Independent Component Analysis (ICA) algorithm. In the cue phase, the EEG epoch of each trial was extracted from the −200 to 300 ms relative to the cue onset. In the target phase, the EEG epoch of each trial was extracted from the 0 to 400 ms relative to the target onset. For the epochs of both phases, baseline corrections were applied with a time interval of −200 to 0 ms relative to the cue onset. Epochs with amplitude exceeding 100 µV were excluded from further analysis (seven epochs in total across all participants).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of behavioral data

-

For each of the two experimental conditions, omissions, trials with incorrect responses, and trials with reaction times (RTs) beyond three standard deviations (SDs) of the mean RTs of the correct trials were excluded from further analysis. These trials were also excluded from the following EEG analysis. Mean RTs were then calculated for the remaining trials, which accounted for 95.85% of the trials in the reward condition and 96.24% in the no-reward condition. Paired t-test was performed to compare the RTs and accuracies between the reward and no-reward conditions.

Analysis of event-related potentials

-

The study first investigated if reward modulated the neural activities over both the motor and the visual areas during the cue phase. Subsequent analysis was then used to examine if and how reward modulated the target processing and the response selection. In the following sections, focus was placed on reward modulation on the relationship between visual and motor components regarding target selection, namely comparing such modulation in motor and visual areas in terms of both amplitude and latency.

To investigate how the motor and visual activities were modulated by reward, two groups of electrodes were identified. Specifically, C5, C3, C1, C2, C4, C6 were identified as motor electrodes; PO7, PO3, O1, PO4, PO8, O2 were identified as visual electrodes. Per convention, C3 and C4[23,24] were used to locate the motor activity, and PO7 and PO8 were used to locate the visual activity[20,25]. However, considering the electrode placement variations in the 10−20 system[26], adjacent electrodes were also included, and signals were averaged over these electrodes to ensure statistical reliability. The electrodes contralateral or ipsilateral to the correct response hand were also identified. Given a right-hand response as the correct response (i.e., when the target head pointed to the right), C5, C3, and C1 were identified as contralateral motor electrodes, C2, C4, C6 as ipsilateral motor electrodes, PO7, PO3, O1 as contralateral visual electrodes, and PO4, PO8, O2 as ipsilateral visual electrodes.

In the cue phase, the data from trials was analyzed with a cue-target interval ≥ 700 ms to reflect the preparation for the upcoming target. A long interval was chosen to avoid the activities during the cue-target interval might be biased by the stimulus-related difference (e.g., a coin vs a mask, see Supplementary Fig. S1). Given that 700 ms was the mid-point of the longest interval, there were still 60% of trials included in the analysis. The amplitudes were averaged over the 0−700 ms time interval for each trial and each electrode, over each group of electrodes (contralateral motor, ipsilateral motor, contralateral visual, ipsilateral visual), and over each condition (reward, no-reward). This was to investigate if both the contralateral and the ipsilateral areas were equally motivated by reward in the preparation of the target. Thus, a 2 (reward: reward vs no-reward) * 2 (target direction: contralateral vs ipsilateral) repeated measures ANOVA was conducted on the mean amplitudes for the motor area and the visual area, respectively.

In the target phase, point-to-point statistical analysis was conducted on the data of the 0−368 ms time interval, as the 368 ms is the mean RT across all participants and conditions. Specifically, the data at each time point were averaged over the trials in each condition and over each group of electrodes. A paired t-test was performed at each time point of the 0−368 ms interval between the reward and no-reward conditions for each of the four areas (contralateral motor, ipsilateral motor, contralateral visual, ipsilateral visual). The threshold for identifying a significant time point was set at p < 0.05 (one-tailed), and continuous time points (n > 1) meeting the significance criterion were grouped into a cluster. A cluster-based permutation test was introduced to correct the multiple comparisons[27]. For each cluster, the t values across the data points were summed into a cluster t value (Tobs). Then, the time courses (one per trial, obtained after averaging across the electrodes) of the reward and no-reward conditions were randomly shuffled. A paired t-test was performed at each time point of the shuffled time courses and the summed T value of the largest cluster (Tper) was obtained. This process was repeated 5,000 times to yield a set of permutated T values (Tpers). The probability of Tobs in the distribution of Tpers was computed to test the cluster-level significance. A cluster was considered significant, given a p < 0.05.

To examine the selective processing related to the target direction, the activity over the ipsilateral area was subtracted from the activity over the contralateral area. This calculation was performed respectively for the visual area and the motor area while collapsing over the reward and no-reward conditions. To statistically validate the selective processing, a paired t-test (two-tailed) was performed for each of the data points within the 0−368 ms time interval. The same permutation above was introduced to identify the significant time cluster.

To assess if there was a shift in latency between the visual selective processing and the motor selective processing, a cross-correlation analysis was performed on the two-time series that averaged across trials and participants. A lag value was generated where the correlation was maximized to indicate the temporal shift between the two-time series. Statistical significance was assessed by permutating the participant-level time series to calculate the null lag value (n = 5,000). Similar cross-correlation was performed to validate if there was a latency difference in both reward and no-reward conditions. Importantly, it was then investigated whether the latency difference was more prominent in the reward condition than in the no-reward condition. A jackknife method (or leave-one-out) was introduced to obtain the individual-level lag value[28]. Permutation-based statistical testing (n = 5,000) was performed to test the difference in the lag values between reward and no-reward conditions.

A potential argument concerning the motor activity is that all of the participants are right-handed, which might have led to biased motor activity. However, it should be noted that the analysis concerning the two hands in this study was focused on whether the hand was contralateral or ipsilateral to the target direction. Given the experimental design in which the target could point to either left or right, the trials under the contralateral condition involved both left and right hands, and the trials under the ipsilateral condition also involved both left and right hands, resulting in the handedness as a controlled factor.

-

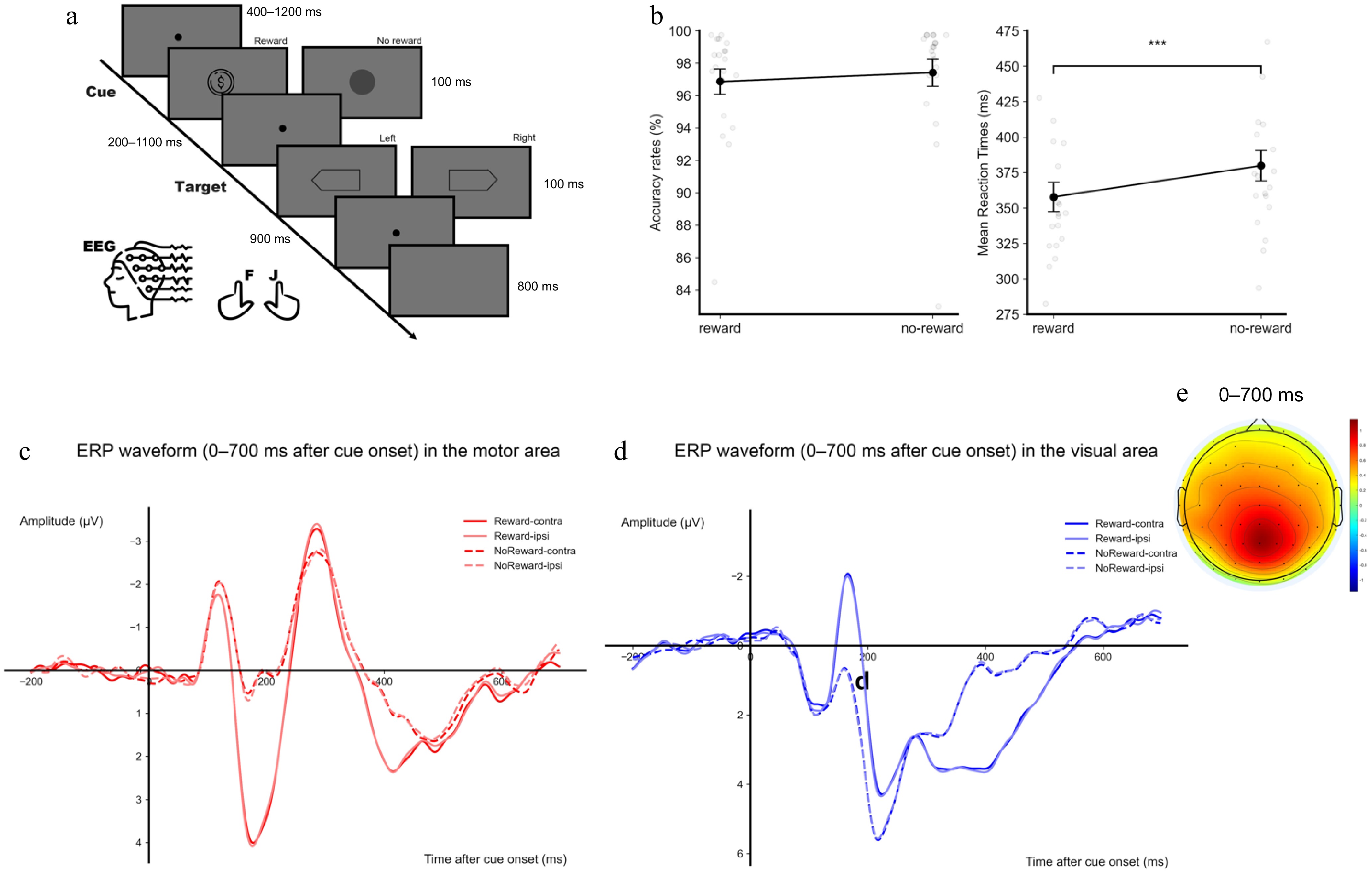

The paired t-test showed that RTs were significantly lower in the reward condition (M ± SE: 358 ± 11 ms) than in the no-reward condition (380 ± 11 ms), t(19) = 6.76, p < 0.001, Cohen's d = 1.510. The accuracy did not show a significant difference between the reward (96.9% ± 0.8%) and the no-reward (97.4% ± 0.9%) condition, t(19) = 1.69, p = 0.107 (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1.

(a) Illustration of the experimental design and an example of a trial sequence. The reward cue was shown as the 1-Yuan coin, while the no-reward cue was shown as the round mask. Participants had to judge the head direction of the target hexagon. (b) Mean accuracies (left) and reaction times (RT, right) are shown as a function of reward. (c) ERP waveforms within 0–700 ms after the cue onset over the motor area. (d) ERP waveforms within 0–700 ms after the cue onset over the visual area. The four conditions are reward-contralateral, reward-ipsilateral, no-reward-contralateral, and no-reward-ipsilateral. (e) The topographical distribution of amplitude difference between reward and no-reward conditions within 0–700 ms after the cue onset. Error bars represent ± 1 s.e.m. calculated across participants (n = 20). ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

EEG data in the cue-target interval: reward-modulated motor and visual activity during target expectation

-

In the cue phase, the ANOVA on the amplitudes of the motor area showed a significant main effect of reward, F(1, 19) = 18.52, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.494, with more positive activity in the reward condition than in the no-reward condition. Neither the main effect of target direction, F(1, 19) = 1.95, p = 0.179, nor the interaction, F < 1, reached significance (shown as ERP representation in Fig. 1c). The ANOVA on the amplitudes of the visual area also showed a significant effect of reward, F(1, 19) = 6.280, p = 0.021, η2p = 0.248, with more positive activity in the reward condition than in the no-reward condition. Neither the main effect of target direction nor the interaction reached significance, both F < 1 (shown as ERP representation in Fig. 1d). These results suggested that both the motor and the visual activity were modulated by reward during the expectation of, hence, the preparation for the target. The scalp distribution of the activity during the cue phase is shown in Fig. 1e.

To test if the EEG activities were biased for one brain hemisphere as all participants are right-handed, the preparation activities between the left (motor: C5, C3, C1; visual: PO7, PO3, O1) and right hemisphere (motor: C2, C4, C6; visual: PO4, PO8, O2) were also compared. For the motor area, the ANOVA on the amplitudes averaged over the 0−700 ms time interval showed a significant main effect of reward, F(1, 19) = 18.522, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.494, with more positive activity in the reward condition than in the no-reward condition. Neither the main effect of the brain hemisphere nor the interaction reached significance, both F < 1. For the visual area, there was also a significant effect of reward, F(1, 19) = 6.279, p = 0.021, η2p = 0.248, with more positive activity in the reward condition than in the no-reward condition (Fig. 1d). Neither the main effect of brain hemisphere nor the interaction reached significance, F < 1. Therefore, the EEG activities were not biased for one hemisphere against the other.

EEG data after target onset: early reward-modulated motor activity corresponding to both response hands

-

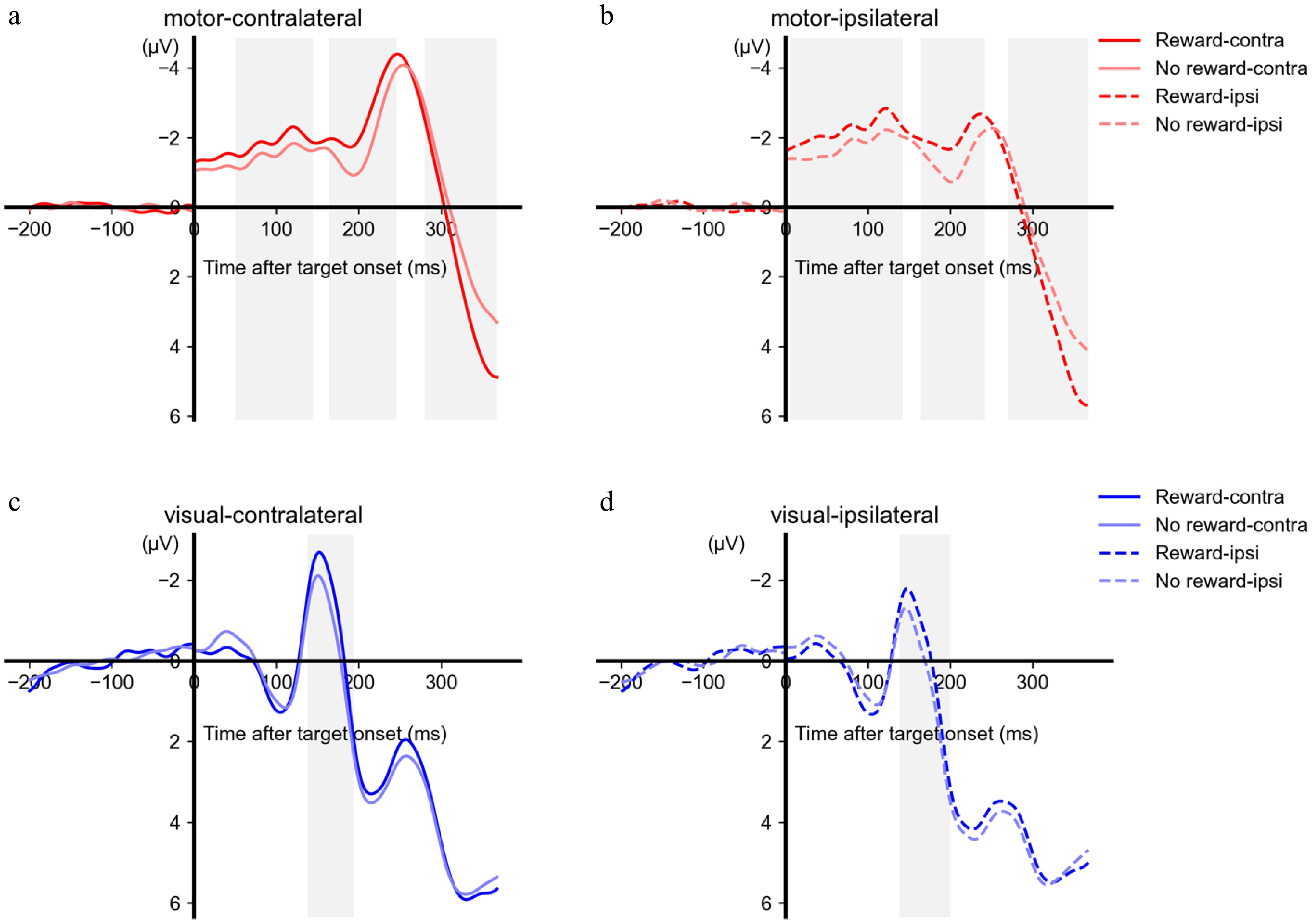

In the target phase, the motor activity contralateral to the target direction showed more negative activity in the reward condition than in the no-reward condition during the time intervals of 50−144 ms (cluster-level p = 0.021), 164−246 ms (cluster-level p = 0.023) and more positive activity in the reward condition during the time intervals of 280-368ms (cluster-level p = 0.024). The motor activity ipsilateral to the target direction showed more negative activity in the reward condition than in the no-reward condition during the time intervals of 6−142 ms (cluster-level p = 0.010), 164−242 ms (cluster-level p = 0.021) and more negative-positive in the reward condition during the time intervals of 270−368 ms (cluster-level p = 0.023). The visual activity showed more negative activity in the reward condition than in the no-reward condition during the time interval of 138−194 ms (cluster-level p = 0.033) over the area contralateral to the target direction, and more negative activity during the time interval of 138−200 ms (cluster-level p = 0.029) over the area ipsilateral to the target direction (Fig. 2). However, the mean difference in amplitudes between reward and no-reward conditions did not show significant differences between the contralateral side and the ipsilateral side, p > 0.102 for all clusters. Note that the results here were to show the reward modulations on the contralateral and ipsilateral side of the target direction, respectively. The point-to-point comparisons between the contralateral and the ipsilateral side are reported in the next section to show the target-selective effects. To avoid circular analysis and redundancy, the potential target-selective effects of the time ranges were not tested.

Figure 2.

ERP results of the target phase. The ERP waveforms are shown as a function of the time, hemisphere (a and c: contralateral to the target direction, b and d: ipsilateral to the target direction), reward, and areas (a and b: motor area, c and d: visual area). Note that the time points after the zero point are relative to the target onset, and the time points before the zero point are relative to the cue onset. The grey-shaded areas represent the time window during which a significant difference in amplitudes was observed between the reward and no-reward conditions.

The above results suggested that the reward modulation emerged at an early range only over the motor area but not over the visual area. To verify this pattern with statistical evidence, data within the early time interval (time range chosen according to the motor area: 50−144 ms at the contralateral side, 6−142 ms at the ipsilateral side) were extracted from the visual area. Analysis of the mean amplitude over the time interval showed no significant difference between reward and no reward conditions, contralateral: t < 1, ipsilateral: t(19) = 1.590, p = 0.128.

EEG data after target onset: reward modulated the integration between the visual and motor activity of the target discrimination

-

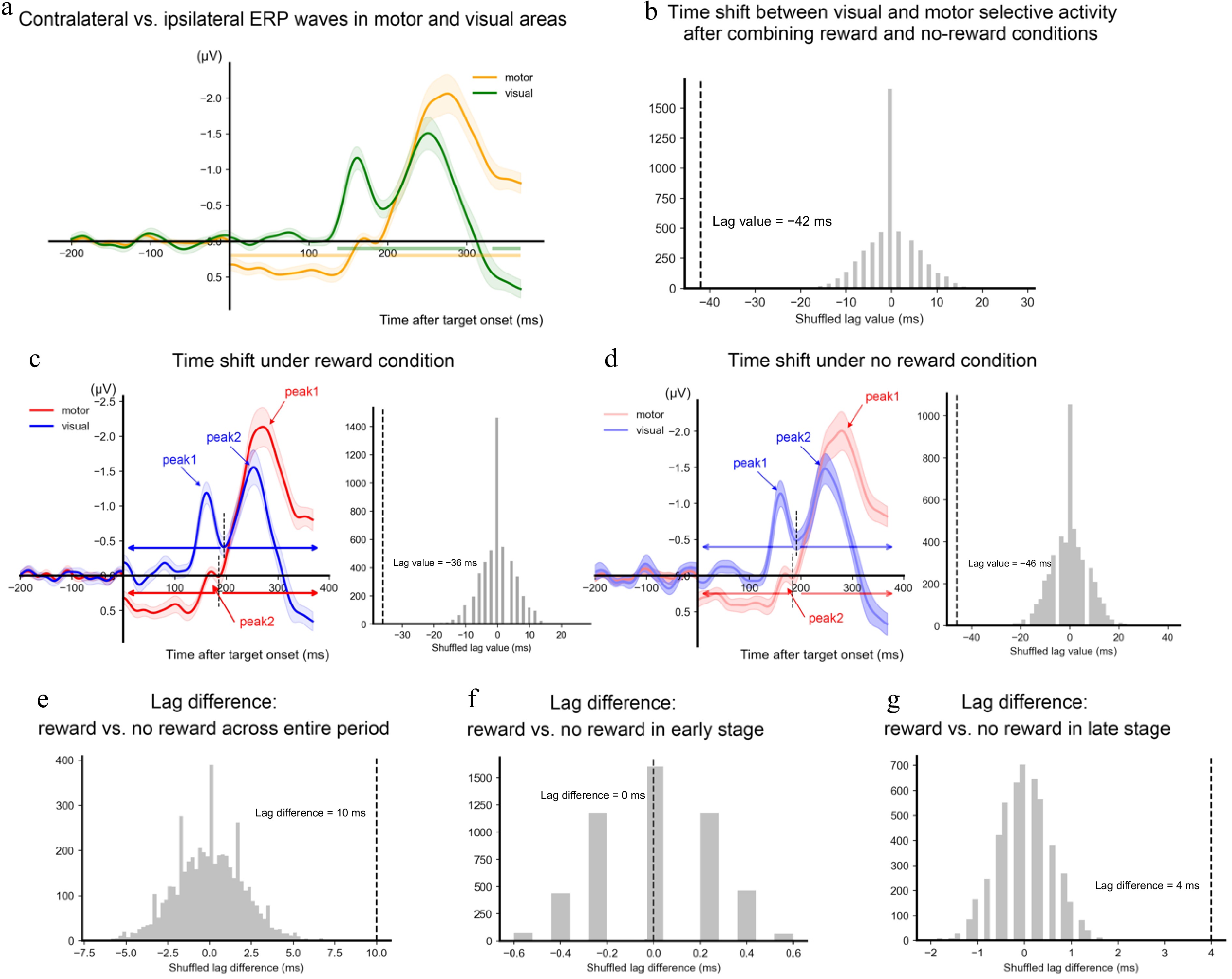

For both the visual and the motor areas, there was selective processing of the target direction, as shown by the significant difference between the contralateral and the ipsilateral activities (Fig. 3a). Specifically, the contralateral visual area showed significantly more negative activity than the ipsilateral visual area during 136−298 ms (p < 0.001) after the target onset, and a trend of difference during 332−368 ms (p = 0.054). The contralateral motor area showed significantly more positive activity than the ipsilateral motor area during 0−152 ms (p = 0.001) but more negative activity during 202−368 ms (p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Latency results of the selective activity. (a) The differences in waveforms between the contralateral side and the ipsilateral side of the target direction are shown as a function of time and area (yellow for motor area and green for visual area). The horizontal lines denote the time clusters showing a significant difference between contralateral and ipsilateral activities. (b) The dashed vertical line denotes the lag value between the visual selective activity and the motor selectivity estimated based on the cross-correlation. The gray bars denoted the distribution of the estimated lag values based on permutations (n = 5,000). (c) Visual (red) and motor (blue) selective activity and the lag results in reward conditions. (d) Visual (red) and motor (blue) selective activity and the lag results in no-reward conditions. Peak values of the identified components are marked in arrows. The short dashed vertical lines on the left panel denote the lowest amplitude between the two peaks. The time range before the lowest amplitude was identified as the early stage, and the time range after the lowest amplitude was identified as the late stage. (e) The difference in visual-motor lag values between reward and no-reward conditions estimated based on the whole time range. (f) The difference of visual-motor lag values between reward and no-reward conditions estimated based on the early stage. (g) The difference of visual-motor lag values between reward and no-reward conditions estimated based on the late stage. All shadings represent ± 1 s.e.m. calculated across all participants.

The results of amplitude did not show a reward modulation on the target selection (i.e., no interaction between reward and target direction over either motor cortex or visual cortex). The study then investigated if reward modulated the latency of activity related to the target. An initial analysis was conducted to determine whether there was an overall latency difference between the visual activity and the motor activity across reward and no-reward conditions. The cross-correlation analysis showed that the selective activity over the visual cortex emerged earlier than the motor cortex, lag value = −42 ms, p < 0.001 (Fig. 3b). Analysis separating the reward and no-reward trials confirmed this earlier emergence of visual selection in both the reward condition, lag value = −36 ms, p < 0.001, and the no-reward condition, lag value = −46 ms, p < 0.001 (Fig. 3c & d). Moreover, further analysis showed that the lag value was larger in the reward condition than in the no-reward condition, lag difference = 10 ms, p < 0.001 (Fig. 3e). These results suggested that there was an overall lag between the visual selective activity and the motor selective activity, this lag was shortened in the reward condition relative to the no-reward condition.

The next analysis examined if the reward modulation on the latency difference between visual selective activity and motor selective activity emerged at an early or a later stage. Specifically, two peak components were detected for each of the time series at the group level and split each time course based on the local maximum of the delineating time point between the two peaks. The former time range was defined as the early stage, and the later time range was defined as the late stage. The cross-correlation analysis revealed that only the late stage indicated a significant difference between the two reward levels (lag difference = 4 ms), p < 0.001, whereas the early stage did not show any significant difference, lag difference = 0 ms, p > 0.999 (Fig. 3f & g). These results suggested that the reward modulation on the lag latency between the visual selective activity and the motor selective activity occurred after the early selective processing.

One may note that the target-selective effect over the motor area emerged as early as the target onset, which might have been due to a lingering effect from the cue-evoked activity. It should be noted that, however, such lingering effects would have been observed over both the visual and the motor areas. This prediction did not fit with the absence of early selective processing over the visual area. Moreover, to statistically test if there was a lingering effect over the motor cortex, data from the −300 to 0 ms relative to the target onset were compared between the contralateral and the ipsilateral sides. This time range was chosen because it covered the cue-target intervals across all trials. Time ranges longer than 300 ms would extend to the time before the cue onset in some of the trials. The data averaged over this time range showed no evidence that the activities differ between the contralateral and the ipsilateral sides, t < 1 (Supplementary Fig. S2). Moreover, a Bayesian t-test yielded a Bayes factor (BF01) = 3.13, indicating that the null hypothesis was 3.13 times more likely to be true than the alternative hypothesis. Following the conventional criteria, a BF > 3 can be taken as moderate evidence for the tested hypothesis[29]. Therefore, the early target-selective effect over the motor area cannot be due to a lingering effect from the cue-evoked activity.

To further test the reliability of the early target-selective effect observed from target onset, additional analysis was conducted using a new baseline interval (−200 to 0 ms relative to target onset). With this baseline, the contralateral motor area showed a trend toward more positive activity compared to the ipsilateral motor area between 44 and 102 ms (p = 0.062), namely, still early but numerically not from 0 ms. The latency results still held under this baseline (Supplementary Fig. S3).

-

The present study investigated how reward modulated the perceptual processing and the action selection of a visual stimulus. The behavioral results confirmed that the perceptual discrimination of the target was facilitated by reward. Regarding how reward modulated visual and motor processing, three hypotheses were raised in the introduction. The first hypothesis predicted that the reward simultaneously modulated the visual and motor processing of the target direction. The second hypothesis predicted that reward modulated the visual processing in an earlier stage than the motor processing of the target direction. The third hypothesis predicted that reward first enhanced both motor candidates of the target direction and then facilitated the integration between visual processing and motor processing. These results clearly supported the third hypothesis. During the expectation of the target, the amplitudes at the contralateral side and the ipsilateral side of the target direction were equally enhanced by reward over both the motor cortex and the visual cortex. Importantly, the reward-enhanced amplitudes over both the contralateral and ipsilateral motor cortex persisted after the onset of the target, whereas this pattern was observed later over the visual cortex. Moreover, after the onset of the target, the selective visual activity concerning the target direction emerged earlier than the second component of selective motor activity. Of note, the latency difference between the two areas was modulated by reward after the initial selective processing (e.g., after the first component of selective processing). Taken together, the findings of this study suggested that reward proactively enhanced the preparation of the target-relative motor candidates before the visual analysis of the target and facilitated the integration of the analyzed visual information with the motor components for action selection.

Considering that the exact time range of an ERP component is subject to the experimental design and the physical properties of the target stimulus, the observed ERP components were not labeled here. However, the two windows of the visual selective activity (136−298 ms, 332−368 ms) could be related to the N1 and N2pc that have been documented in previous studies using forms as target stimuli[30−32]. While N1 was suggested for the processing of early sensory discrimination[18], N2pc was suggested for the feature analysis with focal attention[33]. Of note, N2pc was suggested to be a marker to signal the start of feature integration, where the target feature was integrated with the mental template guided by the task rule[30]. In the same vein, the second window of the motor selective activity (202−368 ms) could be related to the lateral readiness potentials (LRPs) that are time-locked to a visual stimulus[12,34,35]. According to the different functional roles of these components, the first visual selective activity here thus reflected the sensory discrimination of the target stimuli; the second visual selective activity reflected the focal analysis of the target feature so that the target feature can be integrated with the action code required for the final response output. The first motor selective activity reflected response preparation, and the second motor selective activity reflected response generation[36].

One may note that the selective motor activity starting from the target onset (0−152 ms) appeared in positive amplitude in contrast to the negative amplitude of the second selective motor activity (Fig. 3a). This pattern was due to that the motor component contralateral to the target direction was less active than the motor component ipsilateral to the target direction, although they were both proactively prepared for generating response output (Fig. 2a & b). This result might be related to the preparatory motor inhibition that is part of the motor dynamics in action selection[37,38]. In a similar cue-target paradigm, a target was presented either on the left visual field or the right visual field, requiring the response from the left hand or the right hand, respectively. A central cue was presented prior to the target, offering no predictive value for the task-required response. Crucially, response inhibition at the task-required hand, indexed by below-baseline motor-evoked potential (MEP), was observed during the period right before the target onset. This inhibitory process was suggested to decrease the activation of the selected response in order to prevent the premature release of the selected response[38]. Thus, the pattern of the first motor selective activity could be a net result of the proactive motor activation and the preparatory inhibition. Given that the preparatory motor inhibition was present during the period right before the target, the net result of the proactive motor activation and the preparatory inhibition may not last long. The net result thus was soon replaced by the dominance of the selective motor activity concerning the target direction, resulting in a shift of the direction of the activity from positivity to negativity.

Previous studies have treated the visual and motor components in isolation and independently shown that reward can enhance both the perceptual representation[8,10,15], and the action selection[11,12,39] related to a visual stimulus. Extending previous studies, the present work demonstrated how the two components were modulated by reward in a single context and provided a model to link the visual processing and the action selection. Importantly, these results revealed that reward modulation on visual and motor components showed different patterns between the phase of target preparation and the phase of response to the target. Specifically, during the expectation of and hence the preparation for the target, the motor candidates for the final action were proactively prepared, and these motor candidates were equally enhanced during the expectation of a potential reward outcome. These reward-enhanced motor activations persisted after the target was presented and lasted during the visual processing of the target. After the target onset, while the early visual processing was equally enhanced by reward over the contralateral and the ipsilateral side of the target direction, the amplitude of the selective visual processing was not modulated by reward. Instead, the latency results showed that reward shortened the lag between the focal analysis of the target direction and the generation of the response output, suggesting a facilitated integration of the target direction and the action selection.

A related question would be why the reward-facilitated integration occurred during the focal analysis of the target direction (i.e., the late stage) rather than the sensory discrimination of the target direction (i.e., the early stage). It is suggested that the initial sensory discrimination of the target provided only low-level information. Due to a lack of focal attention, the signal-to-noise ratio of the target direction may not be strong enough to be integrated with the action codes. Linking an action code with a noisy visual representation also runs the risk of making an incorrect response. By contrast, during the focal analysis of the target, the increased signal-to-noise ratio would be better integrated with the action codes, which thus would be more subjective to top-down factors such as reward expectation. Similar late effects of reward modulation were also observed in a previous study, which investigated how reward modulated auditory conflict processing[40]. In a cue-target paradigm, a reward (vs no reward) cue was followed by congruent or incongruent auditory information (e.g., an auditory word 'male' pronounced by a male or female voice). The results showed that reward did not affect the N1 component (early sensory discrimination) but reduced the conflict negativity (Ninc, an index of interference effect) in the time range of 300−400 ms[40].

These findings are in agreement with the affordance competition hypothesis of action selection[41]. In contrast to the traditional serial processing framework under which sensory information was first analyzed to inform the action plan and implementation, this hypothesis treated action selection as a dominant role and highlighted it as the primary goal that visual processing serves. In the context of visual perception, it is suggested that the potential actions relative to the visual stimulus compete with each other, during which visual information is collected to bias the competition so that a final response can be selected[16,41]. For instance, in tasks where the participants had to make a reaching movement toward one visual target among the alternatives, the multiple motor components toward the potential targets were activated before the target was specified[17]. Consistent with previous studies, these results suggested that the two potential responses of the visual target were actively motivated by reward, as shown by the sustained amplitude difference between reward and no-reward conditions over both contralateral and ipsilateral motor areas. The motor selection emerged earlier than the visual analysis for discriminating the target feature. These findings suggested that reward enhanced the preparation of the potential actions and sped up the integration of visual information with the action code. The reward modulations suggested that the dominant and active role of action selection may be reinforced through development, as individuals are constantly interacting with the environment and are forced to make action choices[2].

Although the present study focused on the ERP results to show the neural patterns of the reward-modulated visual and motor processes, it should be noted that ERP analysis was one approach among the others to this research question. For instance, oscillatory activities in different bands (e.g., alpha, beta, and theta) can advance the current understanding, as these neural oscillations have been linked to visual spatial attention, action preparation, and value representation[42−44].

-

In summary, this study showed an active role of action selection in a reward-modulated visual perceptual task. Reward enhanced both potential motor activations related to the target during the expectation of the target, and the reward-enhanced motor activations persisted during the visual processing of the target. Moreover, reward did not modulate the early sensory discrimination of the target but rather facilitated the integration of the target feature and the action code required for the response output.

The authors thank Dr. Zhongbin Su for his technical support in data analysis. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 32000779, 32271086), Shanghai Jiao Tong University (Grant No. YG2025QNB13) awarded to LW, and the research project of Shanghai University of Sport (Grant No. 2025STD006) awarded to LZ.

-

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Psychological and Cognitive Sciences, Peking University (#2019-12-01). All procedures were carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Wang L, Zhang L; data collection: Zhang L; data analysis: Ni T, Zhang L; writing original manuscript: Ni T, Wang L. All authors reviewed the results and approved thefinal version of the manuscript.

-

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the OSF repository. These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: https://osf.io/BRDXS.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 EEG data within the 0-300ms cue-target interval.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Contralateral and ipsilateral motor activity in the -300-0ms interval relative to the target onset.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Latency results of the selective activity when the -200 – 0 ms interval relative to target onset was chosen for the baseline correction.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ni T, Zhang L, Wang L. 2025. Active action selection in reward-modulated visual perception. Visual Neuroscience 42: e013 doi: 10.48130/vns-0025-0011

Active action selection in reward-modulated visual perception

- Received: 26 February 2025

- Revised: 06 May 2025

- Accepted: 03 June 2025

- Published online: 22 July 2025

Abstract: Although studies have shown that reward modulates both visual processing and action selection, these components are often treated in isolation. It thus remains unclear how the visual processing links to the motor components. This study answers this question in a cue-target paradigm, where a cue indicates whether a response to the following target can lead to the receipt of a monetary reward or not. The target, a visual form with a left- or right-pointing head, required a corresponding left- or right-hand response, with the cue uninformative of the target direction. Electroencephalography (EEG) signals were recorded to show how the visual and motor activities were modulated by reward. Behavioral results showed facilitated reaction times in the reward condition than in the no-reward condition. EEG results showed that, during the cue-target interval, the activity amplitudes at the contralateral and the ipsilateral sides of the target direction were equally enhanced by reward over both the motor cortex and the visual cortex. After target onset, reward-enhanced motor cortex activity persisted for both sides, whereas this pattern was not observed over the visual cortex. Overall, selective processing of the target direction occurred earlier in the visual cortex than in the motor cortex, and this latency difference was shortened in the reward condition after visual sensory discrimination. Taken together, the derived results suggested that reward proactively enhanced the preparation of the target-relative motor candidates before the visual analysis and facilitated the integration of the analyzed visual information with motor components for action selection.

-

Key words:

- Electroencephalography /

- Reward /

- Visual perception /

- Action selection