-

With advances in computational power, the refinement of learning algorithms and architectures, and the widespread adoption of big data, artificial intelligence (AI) technologies are continuously evolving, providing clinicians with rapid, accurate, and automated tools for diagnostic support and treatment decision-making, thereby promoting the 'intelligent' development of healthcare systems[1]. Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) are both subsets of AI that rely on mathematical algorithms designed to recognize patterns and make predictions based on large volumes of data. The selection between ML and DL approaches should be determined by the specific characteristics of the dataset, the complexity of the clinical task, and the need for interpretability. ML involves using algorithms to learn from pre-extracted features, often based on expert domain knowledge, whereas DL employs neural networks that can automatically learn the relevant features from raw data by constructing multi-level abstractions[2]. Both approaches have important and complementary roles in advancing AI applications in healthcare, including neuro-ophthalmology[3].

In recent years, AI has been widely applied in ophthalmology, where it functions as a predictive biomarker or a clinical decision support tool for eye diseases[4]. Neuro-ophthalmology is an interdisciplinary medical specialty concerned with disorders that involve both the visual pathways and the nervous system. Since the visual system extends from the eyes through to the occipital cortex, intracranial pathologies can frequently result in visual disturbances, often prompting patients to seek an ophthalmologic evaluation[5]. Neuro-ophthalmic diseases are generally divided into two major categories: (1) disorders affecting the afferent visual system, leading to symptoms such as reduced visual acuity and visual field defects due to lesions along the visual pathways; and (2) disorders involving the efferent visual system, which manifest as oculomotor abnormalities, including ocular muscle paralysis, diplopia, gaze instability, and pupillary dysfunction. Conditions affecting the neuromuscular junction or extraocular muscles may also present with neuro-ophthalmic features. Common disease types include optic nerve head (ONH) lesions and various forms of ocular motor dysfunction.

Despite the promising prospects of AI in diagnosing systemic or neurological diseases through ocular examinations, related research and application in neuro-ophthalmology remain relatively underdeveloped[5]. Several factors contribute to this: (1) the low incidence and diversity of neuro-ophthalmic diseases lead to insufficient data for training DL algorithms; (2) the number of neuro-ophthalmologists is relatively small compared with other subspecialties within ophthalmology; and (3) there is considerable heterogeneity in defining the 'ground truth' across neuro-ophthalmic centers. Diagnosing neuro-ophthalmic disorders typically requires multidisciplinary collaboration and the integration of complex clinical information. Accurate diagnosis depends on comprehensive history-taking, comprehensive multi-system evaluation, appropriate neuroimaging, and a well-considered differential diagnosis. Diagnostic errors frequently stem from shortcomings in one or more of these areas[6]. Prior studies including multiple neuro-ophthalmic conditions found misdiagnosis rates of up to 69% prior to the neuro-ophthalmology consultation[7,8]. In some cases, the final diagnosis is made by neurologists rather than ophthalmologists, and this may not be consistently documented in ophthalmic datasets. Such variability leads to inconsistent reference standards and incomplete follow-up data, posing challenges for the development of reliable AI training datasets.

As a new clinical application, using ML and DL algorithms for the rapid and accurate diagnosis of neuro-ophthalmic diseases has become a prominent research direction. Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of the current landscape of AI applications in the management of neuro-ophthalmic disorders. However, guidelines for AI's application in diagnosing neuro-ophthalmic diseases are still lacking. To address the current gap in clinical guidance, members of the Chinese Neuro-ophthalmology Study Group conducted a consensus-driven evaluation of recent evidence from the literature to support the standardized integration of AI into neuro-ophthalmology. This article synthesizes expert perspectives on the application of AI in neuro-ophthalmic diseases, with a particular focus on classical machine learning (CML) and DL approaches. In this context, CML refers to traditional machine learning methods, such as Support Vector Machines, Random Forests, Decision Trees, and k-Nearest Neighbors, which typically rely on structured feature engineering and statistical learning principles. The consensus aims to provide practical recommendations for clinicians, guide future research directions, and promote the ethical and effective use of AI technologies in neuro-ophthalmological practice.

Table 1. Summary of current AI applications in the management of neuro-ophthalmic diseases.

Neuro-ophthalmic diseases Artificial intelligence method Goals/predicted categories Result 1. ONH edema Akbar et al. Support Vector Machine Diagnosing/grading the severity of ONH An average accuracy of 92.86% for the classification of normal and papilledema images; an average accuracy of 97.85% for the classification of mild and severe papilledema images Ahn et al. CNNs and migratory learning methods Classifying photographs according to normal eyes, ONH edema, and pseudo-ONH edema Accuracy of more than 95.8% BONSAI consortium U-Net segmentation network and DensNet classification network Classifying ONH edema and other ONH abnormalities In the validation set, the system discriminated disks with papilledema from normal disks and disks with nonpapilledema abnormalities with an AUC of 0.9, and normal from abnormal disks with an AUC of 0.99; In the external testing dataset, the system had an AUC for the detection of papilledema of 0.96, a sensitivity of 96.4%, and a specificity of 84.7%. 2. Optic atrophy Yang et al. Automatic computer-aided detection Diagnosis of ONH pallor The fully automated CAD system achieved a sensitivity of 95.3% and a specificity of 96.7% for detecting optic disc pallor in color fundus images. The overall accuracy of the CAD system was 96.1%. Cao et al. GroupFusionNet Diagnosis of five optic neuropathies (anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, ONH edema, ONH inflammation, ONH vasculitis, and optic atrophy) GFN achieved a five-class classification accuracy of 87.82% on the test dataset. 3. Chronic glaucoma Li et al. DL system Detecting referable glaucomatous optic neuropathy In the validation dataset, this deep learning system achieved an AUC of 0.986 with sensitivity of 95.6% and specificity of 92.0%. Yang et al. CNN with a residual neural network architecture Distinguishing chronic glaucoma-like optic neuropathy from NGON The diagnostic accuracy of the ResNet-50 model to detect GON among NGON images showed a sensitivity of 93.4% and specificity of 81.8%. The area under the precision–recall curve for differentiating NGON vs. GON showed an average precision of 0.874. Li et al. ResNet-101-based DL method Detection of chronic glaucomatous optic neuropathy: confirmed chronic glaucomatous optic neuropathy, suspected chronic glaucomatous optic neuropathy, and normal eyes Accuracy: 94.1%; sensitivity: 95.7%; specificity: 92.9%; AUC: 0.992 for the identification of chronic glaucoma-like optic neuropathy and suspected chronic glaucoma-like optic neuropathy 3. Ocular motility disorders 3.1 Paralytic strabismus Almeida et al. Computer-assisted diagnostic system Diagnostic system for strabismus The method was demonstrated to be 88% accurate in identifying esotropia, 100% for exotropia, 80.33% for hypertropia, and 83.33% for hypotropia. Figueiredo et al. ResNet-50 as the neural network architecture Classifying the eye versions into nine positions of gaze Accuracy ranged from 42% to 92% and the precision from 28% to 84%, depending on the type of eye Zheng et al. DL method Screening horizontal strabismus in children Using five-fold cross-validation during training, the average AUCs of the DL models were approximately 0.99. In the external validation dataset, the DL algorithm achieved an AUC of 0.99 with a sensitivity of 94.0% and a specificity of 99.3%. Lu et al. Deep neural network Detection of strabismus in a telemedicine setting An accuracy of 93.9%, a sensitivity of 93.3%, and a specificity of 96.2% Jung et al. Active appearance model algorithm Detection of strabismus based on facial asymmetry An accuracy of 95% Chen et al. CNN models Identifying strabismus using eye movement tracking data Accuracy of 95%, a sensitivity of 94%, and a specificity of 96% Valente et al. Traditional computer vision methods Detecting exotropia An accuracy of 93.3%, a sensitivity of 80.0%, and a specificity of 100.0% 3.2 Nystagmus D'addio et al. Randomized samples and logistic regression trees Predicting visual acuity and ocular positional variability Coefficients of determination of 0.70 and 0.73 Wagle et al. DL system to collect data from video of eye movements Identify normal or at least two consecutive episodes of nystagmus The AUC, sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were 0.86, 88.4%, 74.2%, and 82.7%, respectively. Kong et al. CNNs-LSTM Nystagmus Classifier Nystagmus pattern recognition Accuracy of 0.949 and an F1 score of 93.70% for nystagmus pattern classification; the accuracy of this classification network was 0.978 with an F1 score of 97.48%. 4. Other Neuro-ophthalmic Diseases Teh et al. Three-dimensional CNN Predicting the response of patients with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy to lidocaine treatment AUC: 0.96; the F1 score was 0.95 in a validation experiment. Mou et al. DL method Grading the severity of nerve tortuosity An overall accuracy of 85.64% in four levels of grading Thomas et al. Back-propagation artificial neural network Visual field loss caused by pituitary tumors A sensitivity of 95.9% and a specificity of 99.8% CNNs, convolutional neural networks; AI, artificial intelligence; ONH, optic nerve head; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CAD, computer-aided detection; GFN, GroupFusionNet; DL, deep learning; NGON, non-glaucomatous optic neuropathy; LSTM, long short-term memory. -

Neuroelectric signals generated during photochemical processes in the retina are transmitted to the brain via the visual pathway. Damage to this pathway frequently leads to pathological changes in the ONH. A common manifestation is ONH edema, often caused by elevated intracranial pressure, typically resulting from space-occupying lesions or venous sinus thrombosis. If not promptly diagnosed and treated, this condition may lead to optic nerve dysfunction, permanent vision loss, or even death due to sustained intracranial hypertension. Conversely, misdiagnosis of ONH edema can lead to unnecessary, costly, and invasive tests, making accurate diagnosis crucial.

While ophthalmologists can usually identify ONH abnormalities through ophthalmoscopy, clinicians without specialized training − such as emergency physicians or neurologists − often lack the expertise for accurate evaluation. Compared with traditional ophthalmoscopy, nondilated fundus photography offers greater sensitivity for detecting ONH lesions. It enhances diagnostic accuracy and improves the prognosis for optic nerve conditions[9,10], and produces high-quality images that serve as valuable input for AI-based diagnostic systems[10]. For instance, Akbar et al. used CML techniques to extract ONH features from fundus photographs and applied a support vector machine to diagnose and grade ONH edema[11]. Their model achieved classification accuracies of 92.9% and 97.9%, respectively. However, CML approaches typically require large volumes of high-quality, labeled data from clinicians to ensure model reliability, which is labor-intensive and costly. As a result, standalone CML-based models may fall short of clinical requirements for real-time, high-accuracy performance.

To address these limitations, the integration of DL techniques has been proposed. Ahn et al. developed a DL model using a dataset comprising 95 images of optic neuropathies, 295 pseudopapilledema images, and 779 control images[12]. The model integrated convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and transfer learning, along with data augmentation techniques. It achieved over 95.8% accuracy in differentiating ONH edema from pseudo-ONH edema. However, the generalizability of the model is limited by its single-center design, relatively small sample size, and the absence of external validation. To overcome these challenges, the Brain and Optic Nerve Study with Artificial Intelligence (BONSAI) consortium initiated a large-scale, multi-center study in collaboration with ophthalmology centers worldwide. Milea et al. developed a deep learning system (DLS) combining a U-Net segmentation network and a DensNet classification network to classify ONH edema and other ONH abnormalities[13]. The model was trained on 14,341 dilated fundus photographs from 6,779 patients across 19 centers globally, encompassing a wide range of ethnic backgrounds. The training dataset included 9,156 images of normal ONH and 2,148 images of ONH edema, along with additional images of other ONH abnormalities. The final model showed superior performance in classifying normal ONH, ONH edema, and other ONH abnormalities, achieving an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.96 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.95–0.97), a sensitivity of 96.4% (95% CI: 93.9–98.3), and a specificity of 84.7% (95% CI: 82.3–87.1). In addition, BONSAI-DLS was effective in the classification of normal ONH and other abnormalities (e.g., ONH atrophy, non-arteritic ischemic optic neuropathy, ONH drusen), with AUCs of 0.98 and 0.90, respectively[13].

Another key question is whether DLS can outperform human classification accuracy. A recent study demonstrated that the BONSAI-DLS system achieved an overall classification accuracy of 84.7%, similar to that of two experienced neuro-ophthalmologists with over 25 years of clinical practice (80.1% and 84.4%)[14]. Moreover, assessing the severity of ONH edema is vital for predicting the visual prognosis and monitoring disease progression. To this end, the BONSAI study further trained a DLS to classify 1,052 photographs of mild to moderate ONH edema and 1,051 images of severe ONH edema. The model achieved an AUC of 0.93 (95% CI: 0.89–0.96), with an accuracy of 87.9%, a sensitivity of 91.8%, and a specificity of 82.6%, comparable with the performance levels of expert neuro-ophthalmologists[15].

Optic atrophy

-

Optic nerve atrophy results from damage to retinal ganglion cells and their axons caused by various diseases. It is characterized by impaired optic nerve conduction, visual field defects, and reduced or even lost visual acuity. A pale or whitish ONH is a hallmark of optic atrophy[16], and early recognition of this color change can facilitate timely diagnosis. However, due to the subjective nature of ONH color assessments and the lack of standardized diagnostic and severity grading criteria, accurate diagnosis and evaluation remain challenging. To address this, Yang et al. developed a computer-aided detection (CAD) system based on CML[4]. The system automatically segments and enhances ONH features, extracting the color and structural parameters from 230 fundus photographs with varying degrees of pallor and 123 normal images. It achieved a sensitivity of 95.3%, a specificity of 96.7%, and an overall accuracy of 96.1%, outperforming manual assessments. These results suggest that the CAD system can assist ophthalmologists in detecting ONH pallor and improve the early diagnosis of optic nerve atrophy.

In addition, early manifestations of several optic neuropathies often overlap, making differential diagnosis difficult and potentially delaying treatment. To address these issues, Cao et al. developed a CAD system capable of automatically diagnosing five types of optic neuropathies, namely anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, ONH edema, ONH inflammation, ONH vasculitis, and optic atrophy, which achieved an accuracy of 87.8% for early identification of these conditions[17].

Optic neuropathy of chronic glaucoma

-

Glaucoma, which is usually characterized by widening and deepening of the ONH excavation and visual field damage, is the leading cause of irreversible blindness[18,19]. Accurate identification of chronic glaucomatous optic neuropathy is therefore essential, and AI technologies have shown great promise in improving screening and diagnostic efficiency. Li et al. developed a DL system for the automated classification of glaucomatous optic neuropathy, which achieved an AUC of 0.986 with a sensitivity of 95.6% and a specificity of 92.0%[20]. In addition, Yang et al. developed a DL model based on a CNN with a ResNet-50 architecture that was capable of differentiating chronic glaucoma-like optic neuropathy from non-glaucomatous optic neuropathy (NGON)[21]. The system achieved classification accuracies of 99.7% for normal eyes, 86.4% for NGON, and 92.5% for chronic glaucoma-like optic neuropathy, with an overall accuracy of 99.1%. Furthermore, a separate DL model based on a ResNet-101 architecture was applied for multiclass classification among confirmed glaucoma, suspected glaucoma, and normal eyes. This system achieved an accuracy of 94.1%, a sensitivity of 95.7%, and a specificity of 92.9%. The AUC for identifying both confirmed and suspected glaucomatous optic neuropathy was 0.992[22]. These findings underscore the potential of DL algorithms as rapid, accurate, and cost-effective tools to assist in large-scale glaucoma screening and early diagnosis.

AI-assisted diagnosis of ocular motility disorders

-

The precise control of eye movements requires the coordinated integration of the cortical regions, subcortical centers, ocular conjugate premotor circuits, extraocular muscles, and oculomotor-related cranial nerves − particularly the third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerves. This intricate system functions to maintain stable binocular vision. Disruptions along the oculomotor pathway can result in ocular misalignment, conjugate gaze abnormalities, or nystagmus. Both congenital and acquired strabismus may arise from mechanical restrictions of the extraocular muscles, deficits in neural integration or dissociation, or an underlying refractive error. Strabismus can be clinically diagnosed through methods such as the Hirschberg and Krimsky tests and the prism cover test (PCT)[23]. These diagnostic techniques require considerable clinical expertise, typically provided by experienced refractive ophthalmologists. Recent advances in AI have enabled the development of models that analyze eye movement data to predict the features of congenital nystagmus and detect strabismus[24,25]. These AI-based approaches hold promise for broader applications, including the identification of ocular motility disorders caused by oculomotor cranial nerve palsies.

Paralytic strabismus

-

Paralytic strabismus is a common neuro-ophthalmic disorder resulting from dysfunction in the visual efferent pathways. Recent advances in AI have enabled the detection of strabismus through analysis of facial photograph[26]. For instance, Sousa de Almeida et al. developed a CAD system for strabismus using the Hirschberg reflex across five gaze positions, achieving accuracies of 100% for exotropia, 88% for esotropia, 80% for hyperopia, and 83% for hypotropia[27]. Further developments include a DL algorithm proposed by de Figueiredo et al., which categorized eye positions from adult facial photographs via a mobile application. The model achieved accuracy rates ranging from 42% to 92% and precision ranging from 28% to 84%[28]. Zheng et al. proposed a DL method based on primary gaze photographs for screening horizontal strabismus in children, achieving an accuracy of 95%, outperforming ophthalmology residents whose accuracy ranged from 81% to 85%[29]. To advance automated screening techniques, Lu et al. developed a deep neural network for detecting strabismus in telemedicine settings, achieving an accuracy of 93.9%, with a sensitivity and specificity of 93.3% and 96.2%, respectively[30]. In another study, Jung et al. (2019) used full-face images to detect strabismus on the basis of facial asymmetry, reaching an accuracy of 95%[31]. Beyond static image analysis, several studies have explored the use of eye movement videos. Chen et al. utilized eye-tracking data and CNNs in a sample of 17 adults with strabismus and 25 controls, achieving an accuracy of 95%, a sensitivity of 94%, and a specificity of 96%[32]. Valente et al. (2017) analyzed videos of the cover test without specialized equipment, successfully detecting exotropia with 93.3% accuracy, 80.0% sensitivity, and 100.0% specificity[33].

Nystagmus

-

Eye movement is regulated by complex neural and muscular coordination, and damage to any component of the oculomotor pathway can lead to nystagmus[34]. Nystagmus is typically caused by central nervous system pathology, peripheral vestibular disorders, or severe visual impairment, and it can be classified as either congenital or acquired[35]. Because of its complex clinical manifestations, identifying and interpreting the etiology of nystagmus remains a challenge for clinicians. In a study on congenital nystagmus, D'Addio et al. developed a predictive model using randomized samples and logistic regression trees to assess visual acuity and ocular positional variability. On the basis of electrooculographic data from 20 patients, the model achieved coefficients of determination of 0.70 and 0.73 for visual acuity and ocular positional variability, respectively, offering a potential framework for investigating other types of nystagmus[25]. Wagle et al. employed a DL system to analyze eye movement videos and detect normal or pathological nystagmus episodes. The system achieved an AUC of 0.86, with a sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of 88.4%, 74.2%, and 82.7%, respectively. Notably, the model's performance remained stable despite reduced image resolution, suggesting that DL techniques maintain robust accuracy under suboptimal imaging conditions and may serve as effective tools for assisting in diagnosing nystagmus[36].

Accurate identification of the characteristics of nystagmus is critical for determining its underlying cause. Nystagmus is generally categorized as horizontal, vertical, or torsional; however, the existing diagnostic methods often struggle to distinguish these types effectively. To address this, Li and Yang (2023) proposed a DL-based method for recognizing vertical nystagmus, incorporating dilated convolutional layers, depthwise separable convolutions, a convolutional attention module, and a BiLSTM-GRU module, achieving high classification accuracy[37]. To further improve pattern recognition in nystagmus, Kong et al. introduced an automatic classification framework using a combination of DL and optical flow techniques. Their model, built on CNNs for spatial feature extraction and long short-term memory networks for temporal analysis, achieved an overall accuracy of 0.949 and an F1 score of 93.70% for classifying nystagmus patterns. Specifically, the model demonstrated excellent performance in identifying torsional nystagmus, with an accuracy of 0.978 and an F1 score of 97.48%[38]. These findings highlight the potential of AI technologies to accurately classify different nystagmus types and support clinicians in determining the etiology.

AI-assisted diagnosis of other neuro-ophthalmic diseases

-

Ocular myasthenia gravis, a subgroup of myasthenia gravis, primarily affects the extraocular and eyelid muscles, with variable, fatiguing ptosis and ocular muscle paralysis being its most common manifestations[39]. Diagnosing ocular myasthenia gravis remains challenging because of the absence of clear diagnostic criteria[40]. On the basis of the clinical manifestations of ocular myasthenia gravis, Liu et al. developed a CAD system to aid in its diagnosis[41]. This system utilized facial images captured during neostigmine tests and videos of eye movements and eyelid positions. By analyzing parameters such as eyelid distance, scleral distance, and the duration of lid fatigue tests, the CAD system demonstrated superior performance in determining eyeball and eyelid positions compared with manual measurements by clinicians.

Diabetes mellitus can lead to various ocular surface disorders, including dry eye, recurrent corneal ulcers, and diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN)[41]. DPN is one of the most common long-term complications of diabetes, occurring in approximately 10% of patients during the preclinical stage[42]. Current methods for detecting and quantifying DPN find it difficult to detect lesions in small nerve fibers[43]. To improve detection, Williams et al. (2020) developed a DL-based software that integrates corneal confocal microscopy (CCM) with a CNN, enabling end-to-end classification. It achieved an AUC of 0.83, with a specificity and sensitivity of 87% and 68%, respectively[44]. In a separate study, Teh et al. (2023) trained a model using a three-dimensional (3D) CNN to evaluate treatment efficacy for painful DPN. This algorithm analyzes resting-state functional imaging data to extract functional connectivity features and uses independent component analysis to predict the patient's response to lidocaine treatment. In a validation cohort, it achieved an AUC of 0.96 and an F1 score of 0.95, demonstrating that the 3D CNN algorithm can differentiate the response to neuropathic pain treatment in patients with painful DPN[45]. Additionally, Mou et al. (2022) proposed a DL-based approach for analyzing corneal nerves from CCM images to assess the severity of nerve tortuosity in corneal neuropathies. The method involves feature extraction, refinement using a bilinear attention module for predicting the region of interest, and a curvature grading network for final classification. It achieved an overall accuracy of 85.64% across four grading levels, showing promise for broader application in CCM and wide-field fundus imaging[46].

AI technology has also been applied to visual field analysis in neuro-ophthalmic diseases. Lesions along the visual afferent pathways can cause visual field defects, which can be difficult to diagnose when multiple pathologies are present[47,48]. For instance, distinguishing between pituitary adenoma and glaucomatous progression in cases of temporal visual field defects remains a clinical challenge[49,50]. To aid in differentiation, Thomas et al. (2019) developed a feed-forward back-propagation artificial neural network (ANN) for detecting field defects caused by pituitary disease within a glaucomatous population. The predictions of the model were ranked by the probability of having a defect of temporal blindness, with 67% (1,631/2,420) of the tested network models recognizing the lesion as most likely to be of pituitary origin, giving the method a sensitivity of 95.9% and a specificity of 99.8%[51]. In addition, detection of the function of visual afferent pathways can also be accomplished by visual electrophysiological diagnostic tests, such as visual evoked potential (VEP). Early studies have indicated that ML and ANN have significant accuracy in detecting abnormalities in VEP. However, the majority of VEP diagnoses currently rely on interpretation by experienced specialists[52,53].

-

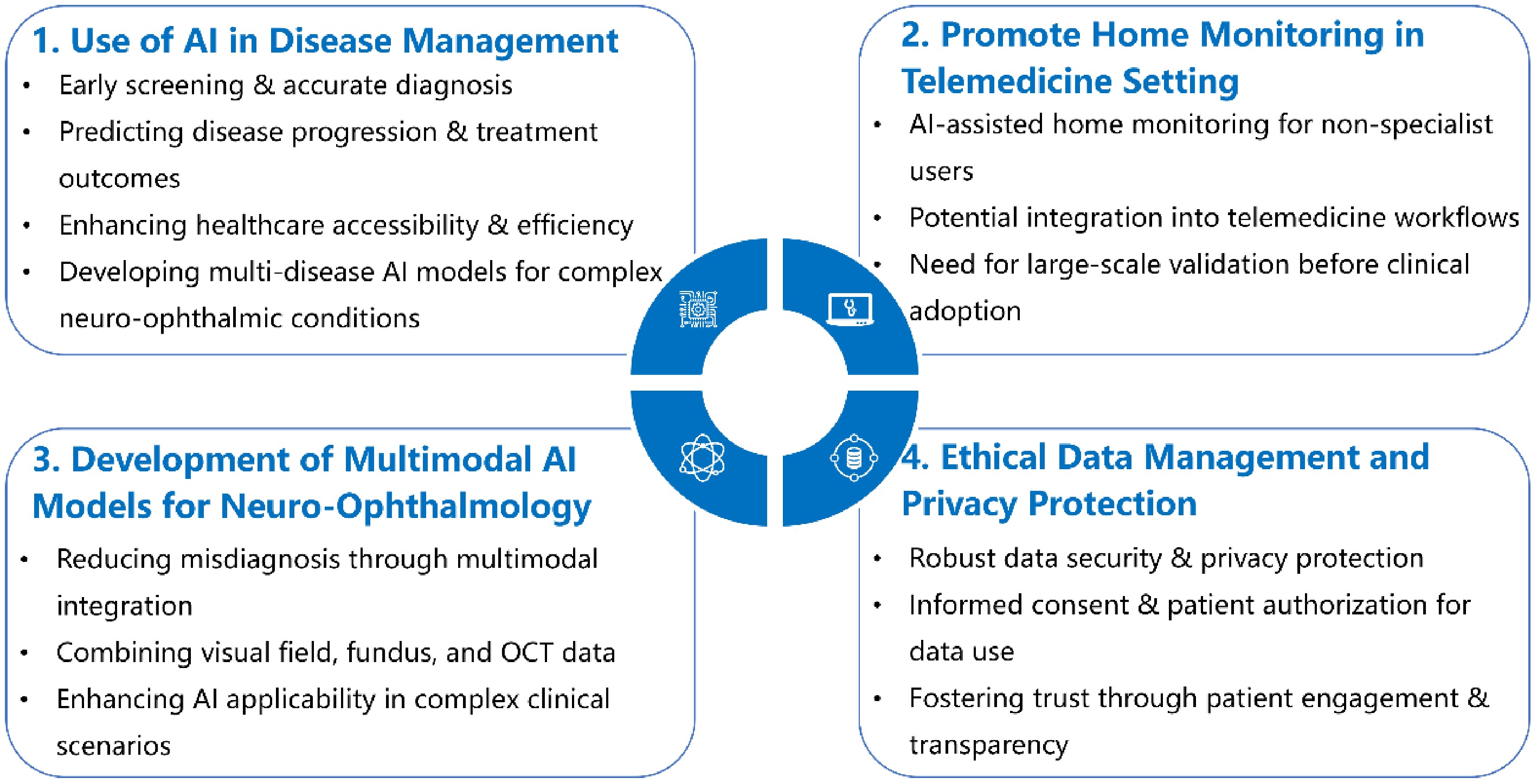

The Neuro-Ophthalmology Vision Academy acknowledges the transformative potential of AI technologies and recommends their adoption to complement and enhance existing standards of care. The expert recommendations are summarized in Fig. 1. In the context of diagnosing and managing neuro-ophthalmic disorders, we highlight the following strategic directions and emphasize key considerations for the future development of AI in neuro-ophthalmology.

Recommendation 1: use of AI in disease management

-

The Neuro-Ophthalmology Vision Academy underscores the promising role of AI technologies in transforming neuro-ophthalmic practice. AI can be integrated into various stages of disease management, including early screening, accurate diagnosis, standardized grading of disease severity, prediction of disease progression, and forecasting of treatment outcomes to support personalized care. Furthermore, AI offers the potential to address the shortage of neuro-ophthalmology specialists − particularly in remote or underserved areas − by providing cost-effective, high-value tools that enhance healthcare's accessibility and efficiency. While current AI research in ophthalmology often focuses on dual classification tasks, given the complexity of conditions involving both the optic nerve and ocular motor systems, it is critical to develop advanced, multi-disease AI models capable of concurrently diagnosing a broader spectrum of disorders. Such comprehensive systems are essential for improving diagnostic precision, optimizing treatment strategies, and ultimately enhancing patient outcomes in neuro-ophthalmic care.

Recommendation 2: promote home monitoring in telemedicine settings

-

AI applications show great potential in the field of neuro-ophthalmology. Patients with certain types of neuro-ophthalmic diseases, such as strabismus and nystagmus, may benefit from AI-based diagnostic approaches utilizing photographs or videos of their eye movements captured via mobile phones[33,54,55]. For instance, Bastani et al. demonstrated that the EyePhone system, which analyzes video oculography data, achieved an AUC of 0.87 for detecting horizontal and vertical nystagmus, highlighting the potential of mobile-based home monitoring in neuro-ophthalmology[55]. This approach could enhance home monitoring for nonspecialist users. However, further large-scale research and validation are needed before these technologies can be widely adopted in clinical practice and telemedicine programs.

Recommendation 3: development of multimodal AI models for neuro-ophthalmology

-

Prior studies involving multiple neuro-ophthalmic conditions have reported misdiagnosis rates of up to 69% prior to the neuro-ophthalmology consultation[7,8]. Potential methods to reduce misdiagnosis include gathering a comprehensive history and using diverse imaging modalities and multimodal AI models to assist in differential diagnosis. Integrating data from sources such as visual field testing, fundus photography, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) can lead to the development of more robust diagnostic tools capable of managing the complexity of concurrent neuro-ophthalmic disorders. For example, a 3D deep-learning system using OCT proposed by Ran et al. demonstrated strong performance in detecting glaucomatous optic neuropathy across both primary and external validation datasets[56]. Therefore, combining multiple modalities can significantly enhance detection capabilities and broaden the clinical applicability of AI in neuro-ophthalmology. This integration not only reduces diagnostic errors but also improves the overall accuracy and reliability of AI-assisted evaluations.

Recommendation 4: ethical data management and privacy protection in AI applications for neuro-ophthalmology

-

Ethical data management and privacy protection are critical in the application of AI to neuro-ophthalmology, especially considering the uniquely sensitive nature of visual data, such as facial images, eye movement recordings, and high-resolution optic nerve imaging. These data types pose heightened risks for re-identification compared with other medical data. We propose the following focused actions.

(1) Enhanced informed consent processes: Patients should receive detailed, understandable information about how their data, including highly identifiable visual information, will be used. Consent should emphasize patient autonomy, allow for specific data-use permissions, and reaffirm the voluntary nature of participation without any form of coercion.

(2) Specialized privacy safeguards for visual data: Given the potential for identity disclosure through eye or facial images, strict anonymization procedures, encryption during storage and transmission, and minimization of identifiable features must be implemented. These measures should be particularly rigorous compared with standard protections of health data.

(3) Ethics and compliance oversight tailored to neuro-ophthalmology: Beyond routine ethical reviews, AI projects in neuro-ophthalmology should adopt domain-specific oversight standards that account for the unique risks of visual data misuse. Institutions should ensure continuous monitoring of privacy risks throughout AI development and deployment.

(4) Promotion of public trust and patient-centric policies: Engaging patients, caregivers, and advocacy groups in discussions about data governance for neuro-ophthalmology AI research can enhance transparency, identify concerns early, and foster responsible innovation.

-

Compared with traditional analytical approaches, AI holds tremendous potential in medical decision support by learning from large datasets and rapidly providing clinical decision-making tools. One of the major challenges currently facing neuro-ophthalmology is the shortage of trained specialists[57]. Leveraging AI technologies, researchers have developed various systems to screen and extract characteristics of the ONH's structure and function, as well as to detect certain ocular motility disorders. These advancements have greatly simplified complex diagnostic processes, offering robust, reproducible, and rapid quantitative diagnoses. To some extent, they have helped alleviate the burden caused by the shortage of neuro-ophthalmologists[58]. With AI-assisted diagnosis and screening, we can further enhance the efficiency and accuracy of neuro-ophthalmic care and improve the overall patient experience. Moreover, AI applications can effectively reduce manual errors and subjective bias, thereby improving the reliability and clinical value of neuro-ophthalmic diagnoses.

However, despite the promise shown by AI in medicine, more nuanced perspectives have emerged[59,60]. First, AI algorithms require large, high-quality datasets for effective classification and prediction. The quality and size of the training datasets directly affect the accuracy and reliability of AI models, making it crucial to establish clear image quality evaluation criteria to quickly screen for high-quality neuro-ophthalmic disease images[61]. Second, although AI models have demonstrated remarkable diagnostic capabilities, their "black box" nature remains a significant barrier to clinical adoption. In neuro-ophthalmology − where diagnostic uncertainty is common and clinical decisions can greatly influence patient outcomes − explainability and interpretability are particularly important. Clinicians must understand the rationale behind AI-generated predictions in order to evaluate their appropriateness, contextualize model outputs within clinical frameworks, and effectively communicate findings to their patients[62]. Interpretable AI frameworks, such as attention heatmaps, saliency maps, and rule-based models, can help build trust and foster collaboration between human expertise and algorithmic support[63]. Thus, future development and evaluation of AI models in neuro-ophthalmology should prioritize not only performance metrics but also transparency, explainability, and alignment with clinical reasoning. Additionally, substantial anatomical and physiological variability among individuals requires AI algorithms to be optimized and adapted across diverse populations to ensure generalizability. Factors such as age and overall health status can influence the presentation of neuro-ophthalmic diseases, underscoring the need to integrate clinical judgment carefully when applying ML models in diagnosis. Furthermore, existing studies often suffer from methodological shortcomings and issues with scientific reporting, such as a lack of prospective randomized controlled trials and insufficient adherence to transparent reporting guidelines. These limitations undermine the credibility and clinical applicability of the research findings. To address these challenges, high-quality studies are urgently needed to evaluate the real-world utility and clinical impact of AI systems in neuro-ophthalmology. Improving the research methodology, enhancing reporting standards, and developing tools to assess the risk of bias will be essential steps forward. While the integration of AI into medical practice will require time and a standardized approach, its long-term potential is considerable. Ophthalmologists may ultimately benefit from AI-assisted disease prediction and monitoring, enabling more personalized treatment strategies. Additionally, nonspecialists may also be able to rapidly identify potential neuro-ophthalmological disorders through AI-enhanced ophthalmologic examinations.

In summary, the integration of AI-driven ophthalmic diagnostic tools is poised to transform the field of neuro-ophthalmology by improving the detection, treatment, and monitoring of neurological disorders, while also addressing the shortage of specialists through scalable solutions. Additionally, mobile-based AI applications, such as video analysis of eye movements, show great promise for supporting home monitoring and telemedicine, especially in conditions like nystagmus. However, further prospective studies using real-world datasets are essential to validate these tools as decision support systems and to benchmark their performance against current standards of care before they can be fully adopted in clinical practice. Nonetheless, several overarching challenges remain, including the need for high-quality training datasets, improved model interpretability, greater population generalizability, and rigorous scientific validation. Ultimately, although AI offers substantial benefits in enhancing diagnostic accuracy, efficiency, and accessibility, its clinical adoption must be informed by ethical, methodological, and practical considerations to ensure its safe and effective implementation in neuro-ophthalmic care.

This study was Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos 82160195, 82201223, 82303221, and 82460203). The authors gratefully acknowledge the members of the expert panel for generously sharing their specialized expertise and dedicating their valuable time to this study.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception: Shao Y, Lou Y, Yu H; study protocol development: Shao Y, Gao Y, Tan G, Liu T. All the authors drafted the manuscript and critically revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Chinese Neuro-ophthalmology Study Group:

-

Yi Shao (Shanghai General Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, China); Yan Lou (China Medical University, China); Yuan Gao (Shanxi Medical University, China); Gang Tan (The First Affiliated Hospital of University of South China, China); Tingting Liu (Shangdong Eye Hospital, China); Honghua Yu (Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital (Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences), Southern Medical University, China); Biao Li (Pingxiang People's Hospital, China); Bin Li (Xinhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, China); Bilian Ke (Shanghai Renji Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, China); Bing Zhang (Hangzhou Children’s Hospital, China); Chenxiao Shen (Guangdong Eye Institute, Department of Ophthalmology, Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital [Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences], Southern Medical University, China); Cheng Chen (The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, China); Cheng Li (Eye Institute of Xiamen University, China); Cheng Yang (Guangdong Eye Institute, Department of Ophthalmology, Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital [Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences], Southern Medical University, China); Chunling Liu (West China Hospital, Sichuan University, China); Chengwei Lu (First Hospital of Jilin University, China); Dan Ji (Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, China); Deyong Deng (Yueyang Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China); Feng Wang (Meizhou People’s Hospital, China); Guanghui Liu (Affiliated People’s Hospital (Fujian Provincial People’s Hospital), Fujian University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, China); Haijun Yang (Nanchang Puri Eye Hospital, China); Hong Wei (The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, China); Hongling Liu (The First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, China); Hui Zhang (The First Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, China); Huiye Shu (Aier Eye Hospital (Wuhan) , China); Jia He (Jining Medical College, China); Jian Ma (The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, China); Jie Zou (The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, China); Jieli Wu (Aier Eye Hospital (Changsha), China); Jingyao Chen (The First Hospital of Kunming, China); Jinyu Hu (The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, China); Juan Peng (The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, China); Jun Liu (The 924th Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, China); Kai Wu (The First Affiliated Hospital of University of South China, China); Lei Shi (Anhui Eye Hospital, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Province, China); Lei Tian (Beijing Tongren Hospital, Capital Medical University, China); Lei Ye (Yichang Central Hospital, China); Liangqi He (The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, China); Lidan Hu (Children’s Hospital Affiliated to Zhejiang University School of Medicine, China); Lijuan Luo (Xiaoshan Hospital, Affiliated with Hangzhou Normal University, China); Lijuan Zhang (Nanchang Puri Eye Hospital, China); Lijun Ji (Shanghai Dahua Hospital, China); Liyang Tong (Wenzhou Medical University Ningbo Eye Hospital, China); Liying Tang, Zhongshan Hospital Xiamen University, China); Liying Zhang (The Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, China); Min Kang (The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, China); Minghai Huang (Aier Eye Hospital (Nanning) , China); Mu Qin (The Affiliated Hospital of Xiangnan University, China); Peiwen Zhu (Eye & ENT Hospital of Fudan University, China); Qi Lin (Shenzhen Futian District Maternity & Child Healthcare Hospital, China); Qi-Chen Yang (West China Hospital of Sichuan University, China); Qian Ling (The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, China); Qianmin Ge (The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, China); Qiaowei Wu (Guangdong Eye Institute, Department of Ophthalmology, Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital [Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences], Southern Medical University, China); Qing Yuan (Jiu Jiang No.1 People’s Hospital, China); Qinxiang Zheng (Eye Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Zhejiang Eye Hospital, China); Qiuyu Li (Women's and Children's Hospital of Hubei Province, China); Rongbin Liang (Jinshan Hospital of Fudan University, China); Sanhua Xu (The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, China); Shen Wang (The First Affiliated Hospital of Xinxiang Medical College, China); Ting Su (Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, China); Weihua Yang (Shenzhen Eye Hospital, China); Wenjuan Zhuang (Ningxia Eye Hospital, China); Wenqing Shi (Jinshan Hospital of Fudan University, China); Xiaomin Zeng (Guangdong Eye Institute, Department of Ophthalmology, Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital [Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences], Southern Medical University, China); Xia Hua (Tianjin Aier Eye Hospital, China); Xiaoming Huang (Sichuan Eye Hospital, China); Xiaoqin Hu (Eye Hospital of Nanchang University, China); Xiaoyu Wang (The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, China); Xiusheng Song (The Central Hospital of Enshi Tujia and Miao Autonomous Prefecture, China); Xuelin Wang (The First Affiliated Hospital of the Jiangxi Medical College, China); Xue-Zhi Zhou (Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, China); Yang Yang (Yueyang Central Hospital, China); Yanmei Zeng (The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, China); Yanwu Xu (South China University of Technology, China); Yanyan Zhang (Wenzhou Medical University Ningbo Eye Hospital, China); Yao Yu (The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, China); Yehui Tan (The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, China); Yichen Xiao (Eye & ENT Hospital of Fudan University, China); Yicong Pan (Shunde Hospital of Southern Medical University, China); Ying Jie (Beijing Tongren Hospital, Capital Medical University, China); Yong Wang (Guangdong Eye Institute, Department of Ophthalmology, Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital [Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences], Southern Medical University, China); Youlan Min (Aier Eye Hospital (Wuhan), China); Yuqing Zhang (The Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, China); Zhe Cheng (Aier Eye Hospital (Changsha), China); Zhengri Li (Affiliated Hospital of Yanbian University, China); Zhenhao Zhang (Suzhou Science Technology Town Hospital, China); Zhenkai Wu (The First People’s Hospital of Changde City, China); Zhirong Lin (Xiamen Eye Center of Xiamen University, China); Zhixing Cheng (Guangdong Eye Institute, Department of Ophthalmology, Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital [Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences], Southern Medical University, China); Zhiyuan Li (Chenzhou No.1 People’s Hospital, China); Zhongwen Li (Wenzhou Medical University Ningbo Eye Hospital, China).

-

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Shao Y, Lou Y, Gao Y, Tan G, Liu T, et al. 2025. Expert consensus on the application of artificial intelligence in neuro-ophthalmic diseases. Visual Neuroscience 42: e019 doi: 10.48130/vns-0025-0018

Expert consensus on the application of artificial intelligence in neuro-ophthalmic diseases

- Received: 07 January 2025

- Revised: 18 July 2025

- Accepted: 21 July 2025

- Published online: 16 September 2025

Abstract: Neuro-ophthalmology is a specialized field at the intersection of ophthalmology and neurology, focusing on visual disorders caused by diseases of the nervous system. With the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) technologies, there is increasing potential to enhance the screening, diagnosis, and management of neuro-ophthalmic diseases, especially in telemedicine and resource-limited settings. To address the current gap in clinical guidance, members of the Chinese Neuro-ophthalmology Study Group conducted a consensus-driven evaluation of recent evidence from the literature to support the standardized integration of AI into neuro-ophthalmology. This article synthesizes expert perspectives on the application of AI in neuro-ophthalmic diseases, with a particular focus on classical machine learning (CML) and modern DL techniques. The consensus aims to provide practical recommendations for clinicians, guide future research directions, and promote the ethical and effective use of AI technologies in neuro-ophthalmological practice.

-

Key words:

- Expert consensus /

- Artificial intelligence /

- Neuro-ophthalmic diseases