-

The posterior segment of the eye, comprising structures such as the retina, choroid, optic nerve, and vitreous body, plays a vital role in the pathogenesis of various ocular diseases. Disorders affecting the posterior segment are among the leading causes of severe vision loss and blindness worldwide[1,2]. The effective treatment of these conditions often requires the delivery of therapeutic agents to the vitreous body, retina, or choroid. However, the anatomical and physiological barriers of the eyes pose substantial challenges to achieving efficient and sustained drug delivery to the posterior segment. This issue has been mostly resolved through intraocular injection when the characteristics of the drug allow this.

However, although intravitreal injections can be highly practical, the requirement for repeated administration poses some problems, such as poor patient compliance, discomfort, and potential complications like infection or retinal damage. Moreover, drugs with short half-lives require repeated injections, further increasing the treatment and financial burden on patients. Therefore, approaches that enable drugs to be retained within the vitreous body and continuously released can resolve previously existing problems. The materials encompass the in situ formation of hydrogels, microspheres, and polymers[3,4]. Among these, the hydrogels formed in situ are regarded as highly promising biomaterials, offering advantages such as excellent biocompatibility, sustained release capacity, and tunable properties. Gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) hydrogels, originating from natural hydrogels, have been used in tissue engineering, biological adhesion, and drug delivery with photocrosslinking by visible light[5−9]. With peptide moieties like arginine–glycine–aspartic acid for cell adhesion and protease degradation, GelMA can closely replicate the natural extracellular matrix[10]. Moreover, GelMA is a multifunctional material that can be easily altered with various bio-functionalities by embedding molecules like drugs, cytokines, and growth factors[11]. It has been designed as an injectable substance for cell delivery with minimal invasiveness[12]. Therefore, these features suggest GelMA as a promising candidate for the design of long-acting intraocular drug delivery systems.

Fungal endophthalmitis is a severe intraocular infection that can cause significant vision loss or even enucleation of the eye[13]. Fungal endophthalmitis poses significant therapeutic challenges because of the prolonged treatment course, high recurrence rate, and poor prognosis[14]. Although repeated intravitreal injections of antifungal drugs offer an effective approach, they are invasive and associated with risks such as retinal detachment and cataract formation. It is urgent to develop antifungal drug delivery systems that can address the limitations of current treatment strategies. Voriconazole (VCZ) is commonly used to manage fungal endophthalmitis because of its wide antifungal effectiveness[15]. However, its poor water solubility and rapid metabolism lead to fluctuating concentrations and limited bioavailability. A sustained release system for VCZ is essential to deliver an initial burst that quickly achieves therapeutic levels, followed by a steady release that maintains the effectiveness over time. Although there have been a few studies on drug delivery systems for VCZ, they have some limitations, such as the insufficient duration of release and the potential for inflammatory stimulation[16,17].

In this study, a GelMA-based hydrogel was developed as an intraocular delivery system for VCZ, and the release properties were assessed for its potential application for sustained vitreous release of the drug. The characteristics of the GelMA hydrogel were also evaluated for this application, including its morphology, injectability, mechanical properties, swelling behavior, biodegradability, and cytotoxicity. This innovative approach aimed to achieve controlled and sustained release, reduce the dosing frequency, and enhance the therapeutic outcomes of fungal endophthalmitis.

-

GelMA (EFL-GM-90, 90% ± 5% graft degree, 100–200 kDa; Lot No. 230921) and lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) (Lot No. 230921) were obtained from Suzhou Intelligent Manufacturing Research Institute (IMRI, Jiangsu, China). All reagents for cell culture were sourced from Gibco BRL (New York, USA). The dispase was purchased from Roche (IN, USA; Lot No. C100C1). VCZ was obtained from MCE (NJ, US; Lot No. 20322). Live/dead assay kits were sourced from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Shanghai, China; Lot No. 2566203). Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) was purchased from Xinsaimei (Suzhou, China; Lot No. 20231213). Collagenase II was sourced from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA; Lot No. 0000371452). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA; Lot No. G1005-1). Human retinal pigment epithelial (HRPE) cells were obtained from the Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, Sun Yat-sen University, under ethical approval (2018KYPJ034, 1 March 2018). New Zealand White rabbits (three months old) were obtained from Huadong Xinhua Experimental Animal Farm (Guangzhou, China).

Preparation of the GelMA and VCZ-loaded GelMA hydrogels

-

LAP was fully dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a concentration of 0.25% (w/v) and heated to 50–60 °C for complete dissolution. Subsequently, the LAP solution and GelMA powder were thoroughly mixed at three concentrations (5%, 10%, and 20%), in line with previous studies[18−20]. The precursor solution was sterilized with a 0.22-μm membrane filter. VCZ was incorporated into the GelMA solution at 1 and 2 mg through full mixing. The precursor solutions of the hydrogels were maintained at 37 °C for 10 min and then photocrosslinked under visible light (405 nm, 30 mW/cm2) for 30–60 s using a visible light source (Suzhou IMRI, Suzhou, China). The visible light falls within the human visible spectrum, and the safety of the visible light of the device has been validated in a previous study[18]. GelMA hydrogel samples were fabricated into rectangular slabs measuring 3 cm in length, 1 cm in width, and 0.1 cm in thickness to evaluate optical transparency. The light transmittance was recorded over the 400–800 nm wavelength range using an ultraviolet (UV) spectrophotometer, with the LAP solution used as the reference blank.

Scanning electron microscopy

-

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) was used to assess the morphology and outer surfaces of the lyophilized samples. First, the samples were frozen at −80 °C for 24 h to ensure complete solidification. The frozen samples were then subjected to lyophilization at −50 °C for a duration of 72 h under a vacuum pressure of 10−1 mbar. After lyophilization, the samples were coated with a thin layer of gold to enhance conductivity, and SEM imaging was performed to observe their surface topography, porosity, and overall structural characteristics.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and thermogravimetric analysis

-

The structural characterization of GelMA hydrogels was examined by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy using a Cary 630 FTIR spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) in attenuated total reflection (ATR) mode. Spectra were collected in the range of 4,000–400 cm–1 with a resolution of 4 cm–1, averaged over 16 scans. Thermal stability and degradation behavior were further assessed by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) using a Discovery TGA 550 instrument (Waters Corporation, New Castle, DE, USA). Freeze-dried hydrogel samples were placed in platinum pans and heated from 30 to 600 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere.

Mechanical, swelling, and degradation behaviors in vitro

-

The tensile and compressive properties of the GelMA hydrogel, from 5% to 20%, were assessed using standardized mechanical testing protocols. Uniaxial tensile testing was performed on hydrogel specimens at a constant displacement rate of 1 mm/min until failure. Compressive testing was conducted using a texture analyzer with cylindrical hydrogel samples (8 mm in diameter, 5 mm in height) compressed at a rate of 2 mm/min at maximum deformation.

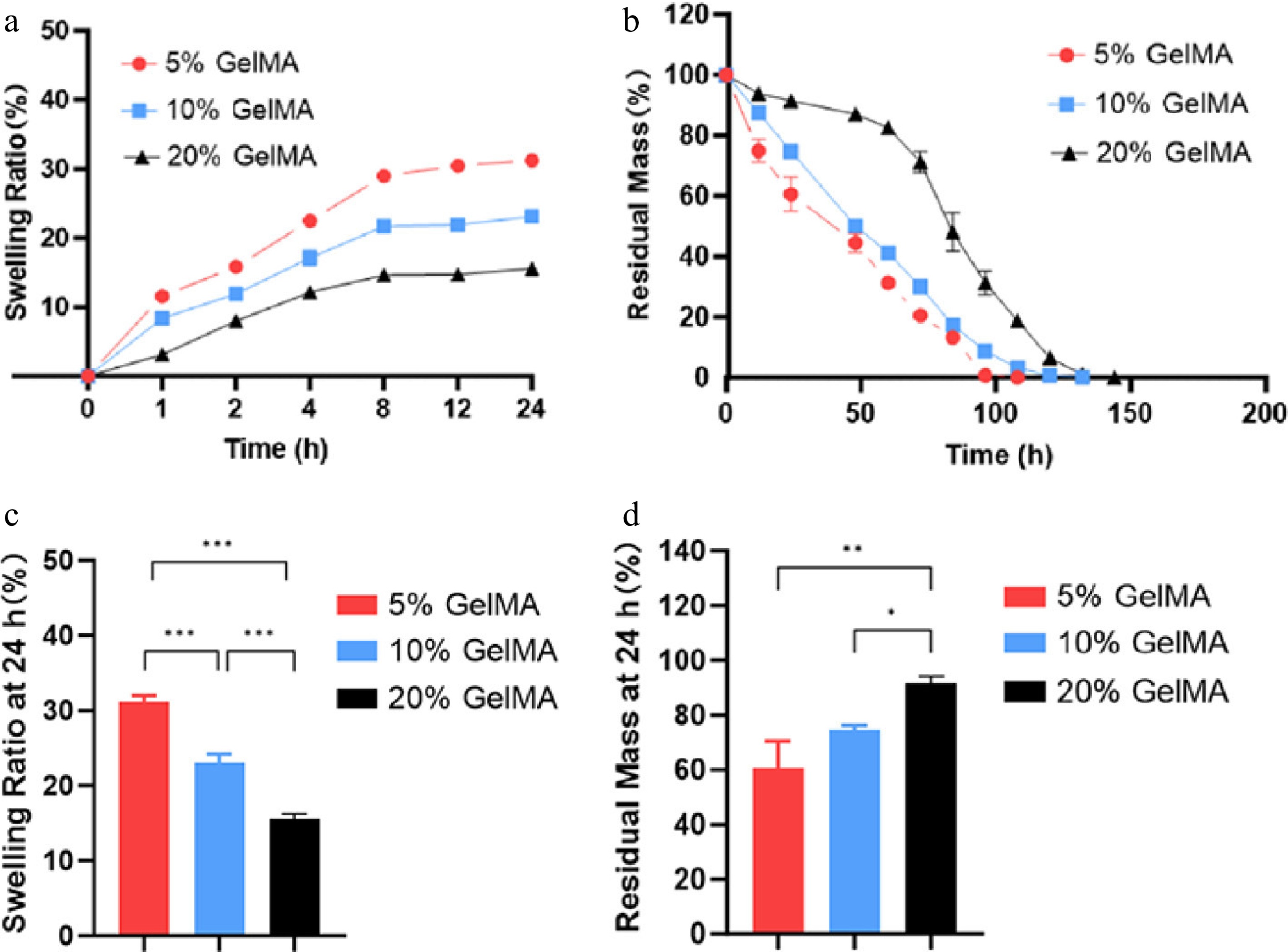

The swelling and degradation behaviors of GelMA hydrogels (250 µL) were evaluated in vitro using a gravimetric method in PBS at 37 °C. The initial weight of the hydrogel (W0) was recorded, after which the hydrogel was immersed in sufficient PBS and incubated at 37 °C. The degree of swelling was monitored by measuring the swollen hydrogel (Wt) weight at predetermined intervals (1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h). The swelling ratio was determined according to the following equation: Swelling ratio (%) = (Wt − W0)/W0 × 100%

The GelMA hydrogels were immersed in PBS and maintained at 37 °C for the degradation study, and the weight loss was monitored over time. GelMA hydrogels were subjected to degradation analysis using Collagenase II, following a method described previously[21]. At each time point (every 8 h), the hydrogels were removed to be weighed (Wt) after being gently blotted with filter paper. The PBS was then replaced with fresh medium to maintain consistent soaking conditions. The degradation percentage was calculated on the basis of the initial and final weights of the hydrogels using the following equation: Degradation ratio (%) = (W0 − Wt)/W0 × 100%

Drug release behavior in vitro

-

The in vitro release of VCZ from the GelMA hydrogels in PBS (pH 7.4) at 37 °C was assessed. The precursor GelMA solution (200 µL) was first loaded with 1 mg and 2 mg of VCZ, and then the mixture was solidified. Following formation of the hydrogel, 25 mL of PBS was poured into the vial to serve as the release medium. The vial was then placed in a water bath shaker maintained at 37 °C with a frequency of 50 cycles per min. At predetermined time intervals, 2 mL of the sample was collected for analysis, and the same amount of fresh PBS was replenished in the release vessel. According to the pharmacopeia, the concentration of VCZ was assessed using high-performance liquid chromatography with UV detection on a C18 reversed-phase analytical column at 251 nm and 35 °C. The mobile phase consisted of 0.02 mol/L ammonium acetate buffer (pH 4.0 ± 0.3), methanol, and acetonitrile, mixed at a volume ratio of 55:15:30. The volume injected was 10 µL, and the flow rate was set to 1.0 mL/min. VCZ concentration was evaluated by comparing the sample's absorbance with a standard curve. The cumulative percentage of VCZ released was calculated to express the drug release profile.

Cell studies in vitro

-

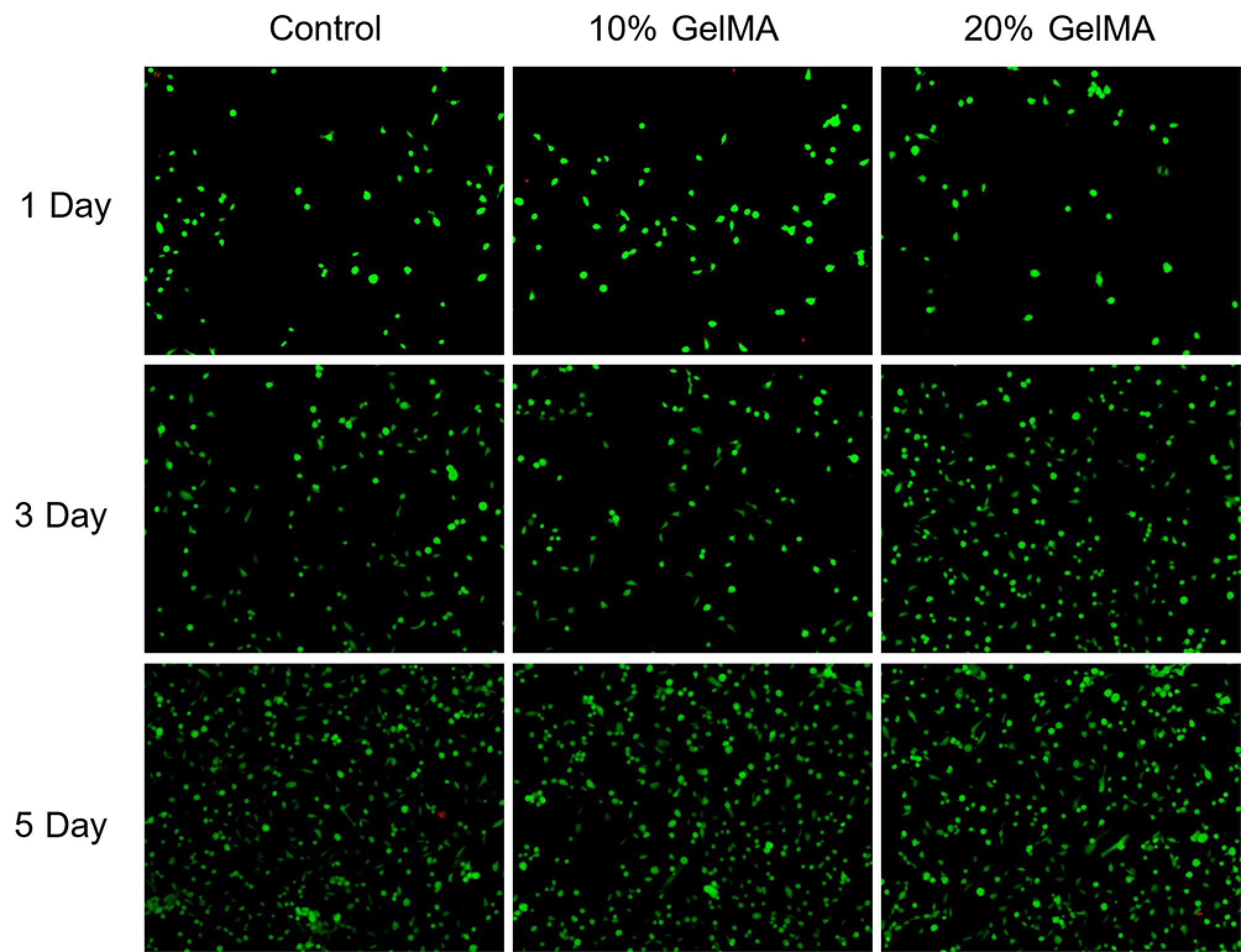

Cytotoxicity assessments in vitro were performed on HRPE cells, a commonly utilized cell for cytotoxicity testing. For leachate-based cytotoxicity evaluation, the hydrogels were soaked in the culture medium at a ratio of 0.1 g of gel per 1 mL of medium. The extract was then used to culture HRPE cells under standard conditions (37 °C, 5% CO2). The precursor solutions were prepared as previously described and filtered using a 0.22-µm filter.

A live/dead assay kit was used to assess cell viability. HRPE cells (3 × 105 cells/well) were treated with 0.5 µL/mL calcein acetoxymethyl ester (AM) and 2 µL/mL ethidium homodimer-1 in Dulbecco's PBS for 15 min at 37 °C, enabling simultaneous staining of living and dead cells. The live (green fluorescence) and dead (red fluorescence) cells were visualized using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Germany) at 1, 3, and 5 days after cell seeding. Subsequently, the numbers of live and dead cells were quantified using ImageJ (Fiji) software. Cell viability was determined according to the following equation: Cell viability (%) = (Number of living cells/Total number of cells) × 100%.

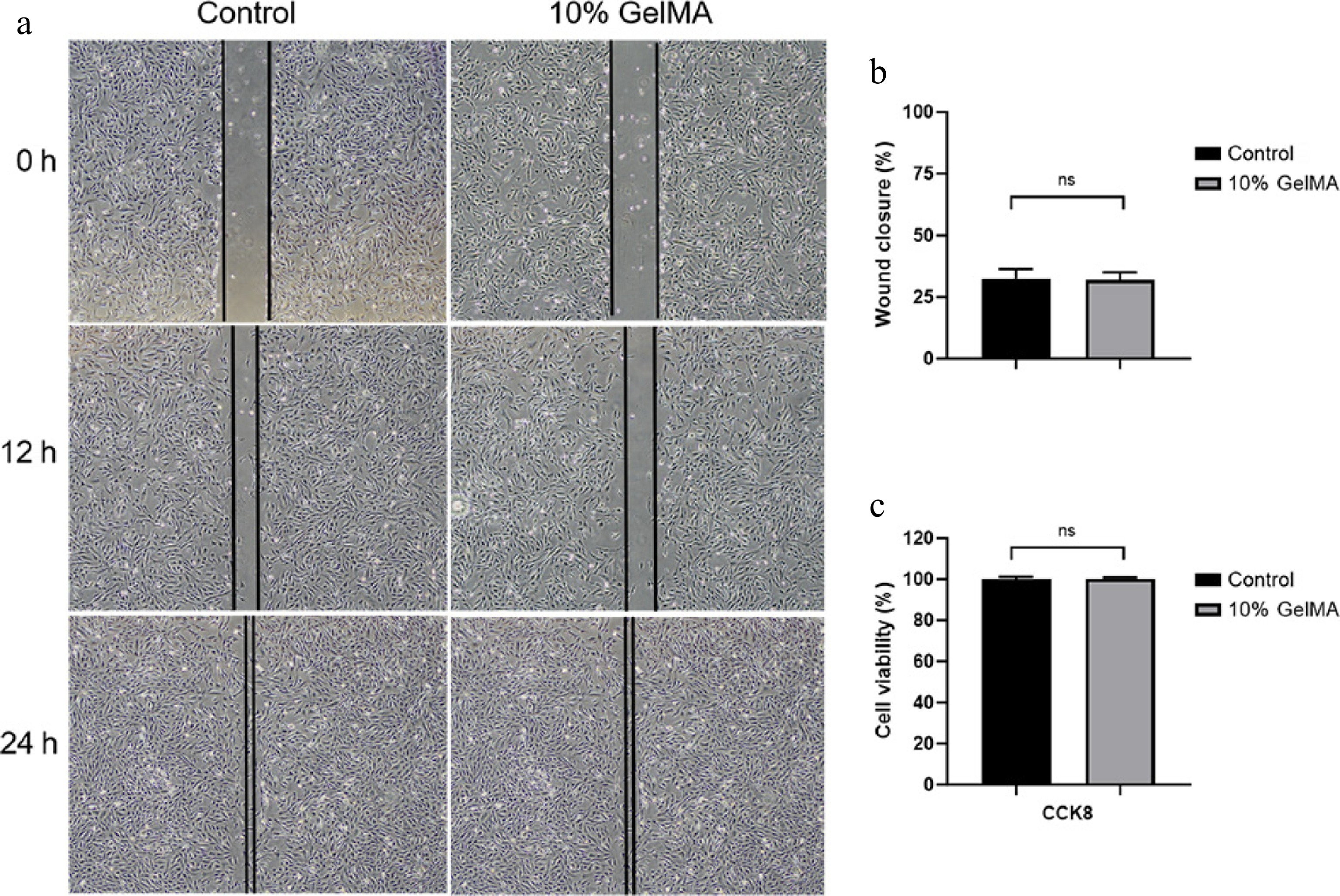

HRPE cells were inoculated into 96-well plates (5 × 103 cells/well) for 24 h to facilitate cell adhesion and assess the cells' activity using a CCK-8 kit. The medium was then removed from the 96-well plate, and the adhering HRPE cells were rinsed three times with PBS. The wells for the test and control groups were inoculated with the plain culture medium and the culture medium containing 10% GelMA hydrogel leachate. After culturing for 24 h, the initial culture medium was replaced with 100 μL of fresh culture medium combined with 10 μL of the CCK-8 solution. The absorbance was then measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader after a 2-hour incubation.

The wound healing experiment was performed to assess cell migration function. HRPE cells at a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL were seeded into six-well plates. Once HRPE cells achieved 80%–90% confluence, a cell scraper was used to create straight scratches in the cell monolayer. Subsequently, plain culture medium and the medium with 10% GelMA hydrogel were added to the wounded cell monolayers. The area of the scratch region was measured by Fiji software after 12 h.

Biocompatibility in vivo

-

All animal experimental protocols are conducted following the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research[22]. The guidelines were developed according to the Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center. The biocompatibility in vivo was assessed by implanting the hydrogel into the vitreous cavity of three-month-old New Zealand White rabbits. The rabbits were maintained in an environment with standard conditions of 25 °C and 50% relative humidity at the Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center (Sun Yat-Sen University) animal facilities with food and water. The procedure involved anesthetizing the rabbits via an intravenous administration of 2% pentobarbital sodium at a dosage of 30–40 mg/kg. After administering a xylazine solution intramuscularly at a dosage of 0.5 mL/kg per kilogram of body weight, topical anesthesia was applied using 0.5% alcaine to minimize the discomfort of the rabbits. Fifty microliters of the prepared precursor solution loaded in a 1-mL syringe (25-gauge) was injected into each rabbit's vitreous body through a 25-gauge incision. Subsequently, the precursor solutions were crosslinked via photopolymerization under 405 nm visible light for 30–60 s. An Elizabethan collar was applied to prevent the rabbits from scratching their eyes after they received the treatment. Slit lamp biomicroscopy, color fundus photography, optical coherence tomography (OCT), electroretinography (ERG), and intraocular pressure (IOP) measurements were performed at predetermined time intervals. At 2 months post-injection, the eyeballs of the rabbits were enucleated after the animals were euthanized and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Paraffin-embedded sections with a thickness of 10 μm were prepared and stained with H&E following standard protocols, and the slides were then examined.

Statistical analysis

-

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Student's t-test in SPSS (IBM SPSS 23.0, SPSS Inc). Differences with p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

-

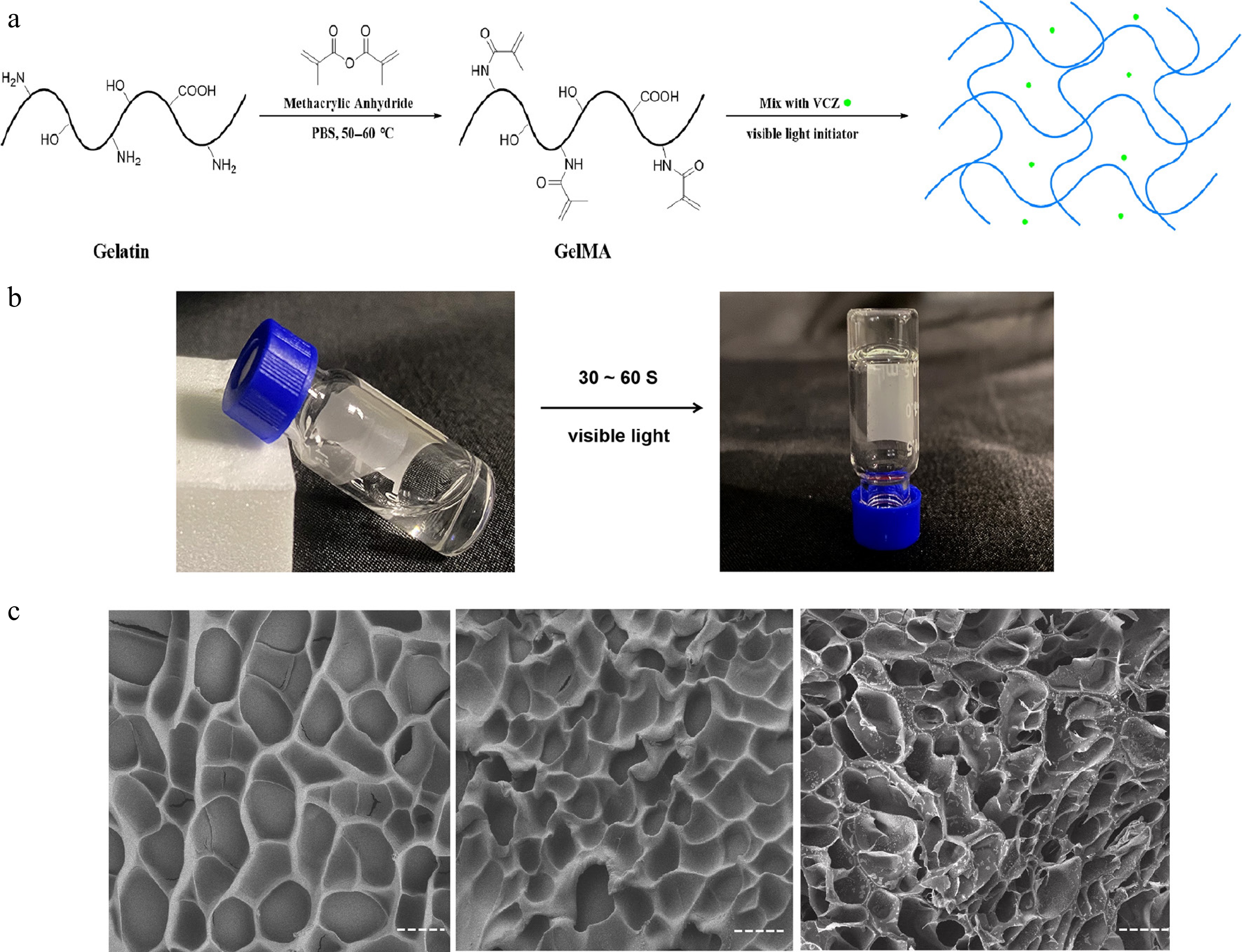

The GelMA hydrogels were synthesized via the photochemical reaction of methacryloyl units on GelMA chains in LAP solutions and photocrosslinked by visible light at 405 nm for 30–60 s (Fig. 1a, b). This wavelength falls within the human visible spectrum, ensuring safety and preventing intraocular damage. The GelMA hydrogels exhibited favorable optical transparency over 94.92% ± 0.33%, 94.33% ± 0.25%, and 93.83% ± 0.12% in 5% to 20% GelMA in the visible light spectrum, minimally obstructing visible light imaging within the eye. Furthermore, GelMA hydrogels demonstrated tunable injectability across varying concentrations. Specifically, 10% GelMA hydrogels could be easily injected in the desired shapes at ambient temperature through a standard 1-mL syringe.

Figure 1.

The preparation and characterization of the GelMA hydrogels. (a) Schematic illustrations of the synthesis of GelMA hydrogel with VCZ. (b) Enlarged view of the GelMA hydrogel's formation. (c) SEM images of the blank hydrogels (10% and 20% GelMA) and the drug-loaded hydrogels (10% GelMA).

Morphology of the hydrogels

-

The SEM images revealed the structural characteristics of freeze-dried GelMA hydrogels loaded with VCZ as a model drug. Increasing the GelMA concentration resulted in a concomitant decrease in the hydrogels' pore size, indicating a denser structural arrangement. The apparent pore sizes of GelMA hydrogels with 10% and 20% concentrations were approximately 16.9 ± 3.24 and 12.00 ± 3.04 μm (p < 0.05, t-test), respectively. The SEM images revealed that the pit-like structures were highly homogeneous and largely noninterconnected, indicating robust structural integrity and a consistent chemical composition. The morphology of the drug-loaded GelMA hydrogel closely resembled that of the blank hydrogel, implying that the drug was uniformly distributed within the GelMA matrix (Fig. 1c). This uniform pit-like architecture plays a crucial role in facilitating the efficient transport and sustained release of the encapsulated drug.

FTIR and TGA of hydrogels

-

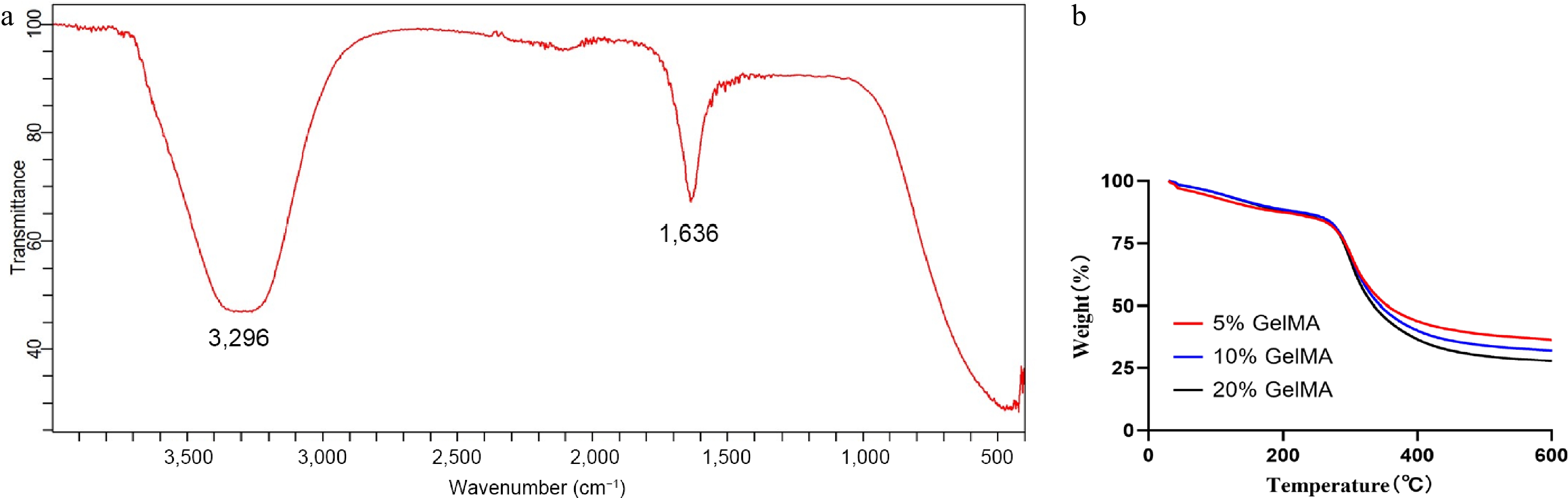

FTIR spectroscopy confirmed the characteristic absorption bands of GelMA hydrogels (Fig. 2a). The broad peak at 3,296 cm−1 corresponded to O–H and N–H stretching vibrations, whereas the band at 1,636 cm−1 was assigned to the C=O (Amide I), indicating the presence of functional groups typical of GelMA. TGA further revealed the thermal stability of the hydrogels with different concentrations (5%, 10%, and 20%; Fig. 2b). All samples lost weight below 150 °C through water evaporation, and a major degradation occurred between 250 and 400 °C from breakdown of the polymer backbone. Among the different concentrations, the 20% GelMA hydrogel had a slightly lower weight at high temperatures.

Figure 2.

Fabrication and thermogravimetric analysis of GelMA hydrogels. (a) The FTIR spectra of the GelMA hydrogels. (b) Thermogravimetric analysis of 5%, 10%, and 20% GelMA hydrogels.

Mechanical, swelling, and degrading properties of hydrogels

-

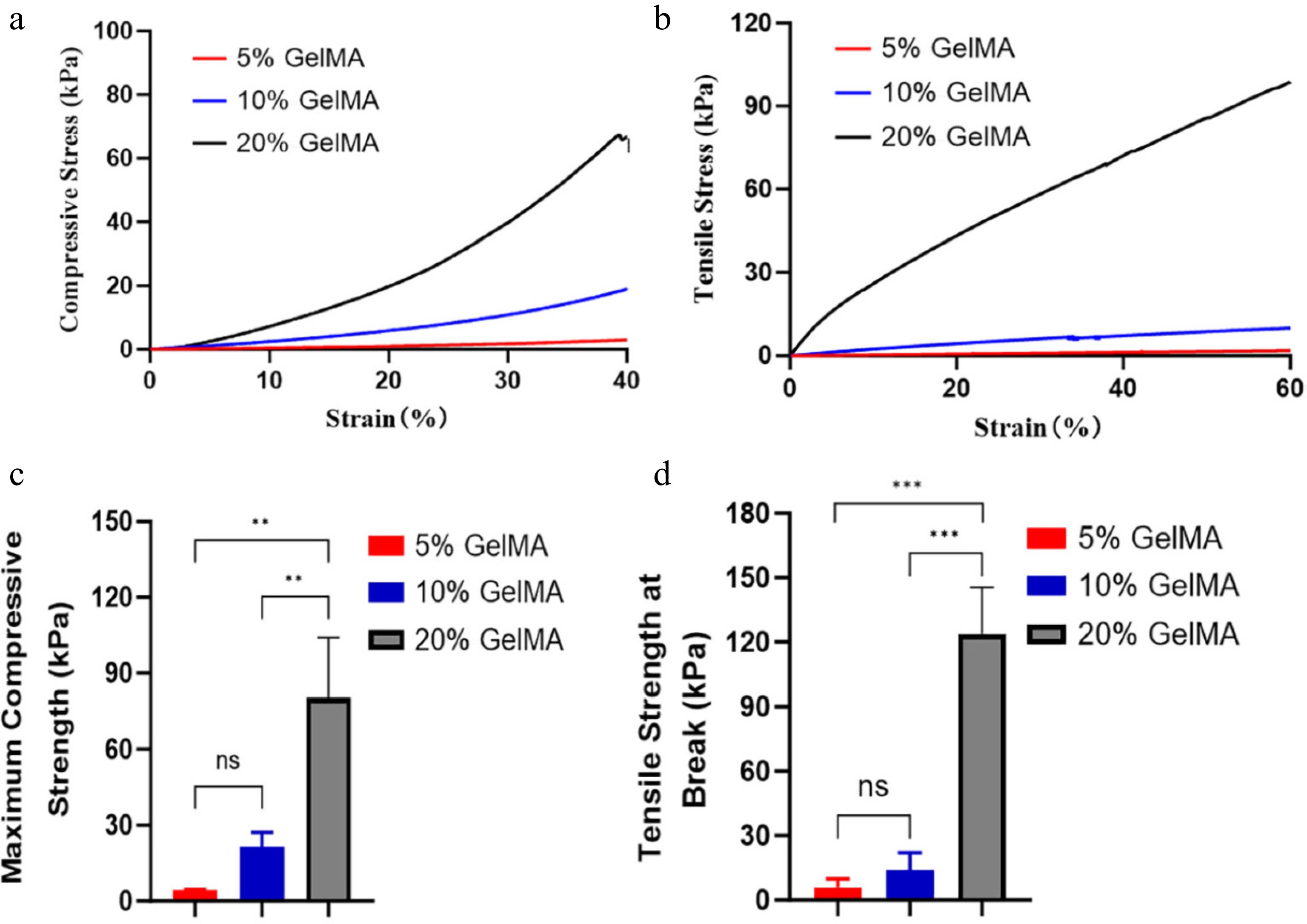

GelMA hydrogels were mechanically assessed using standard uniaxial tension and compression tests at varying concentrations. The hydrogels demonstrated maximum compressive moduli (4.34 ± 0.24, 21.33 ± 5.87, 80.33 ± 23.79 kPa; p < 0.05, ANOVA, Fig. 3c) and tensile moduli (4.14 ± 5.39, 13.96 ± 8.14, and 123.89 ± 21.62 kPa; p < 0.05, ANOVA, Fig. 3d), both of which increased with higher GelMA concentrations from 5% to 20%. Notably, their mechanical properties can be modified to closely resemble those of natural retinal tissue (10–20 kPa)[23], suggesting that GelMA hydrogels could integrate seamlessly with native retinal tissue.

Figure 3.

The mechanical properties of GelMA hydrogels. (a) The compressive stress–strain curve of GelMA hydrogels at different concentrations. (b) The tensile stress–strain curve of GelMA hydrogels across different concentrations. (c) The maximum compressive stress among 5%, 10%, and 20% GelMA hydrogels (p > 0.05, ANOVA). (d) Tensile modulus at breaking strength of different hydrogels (p > 0.05, ANOVA). ns > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

The swelling characteristics of hydrogels are crucial for intraocular implant applications. A lower swelling ratio is desirable to mitigate the risk of elevated intraocular pressure and other ocular complications. The present study revealed that GelMA exhibits a higher volumetric expansion at low concentrations. As the concentration of GelMA was raised from 5% to 20%, the maximum swelling ratio of the hydrogel decreased from 31.23% ± 0.77% to 15.54% ± 0.68% (p < 0.001, ANOVA, Fig. 4a, c). Moreover, the hydrogel reached the maximum swelling volume within 12 h. The enzymatic degradation of hydrogels significantly impacts the rate of drug release. To investigate the protease-mediated degradation behaviors of GelMA hydrogels, we immersed GelMA samples in a collagenase solution and monitored the change in the hydrogels' weight over time (Fig. 4b). The 5% GelMA hydrogel exhibited rapid degradation, with a mean mass loss of 39% ± 9.81% within 24 h. In contrast, the 20% GelMA hydrogel showed significantly slower degradation, losing only 8.52% ± 2.88% of its mass over the same period. This marked difference in the degradation kinetics highlights the potential to fine-tune GelMA-based biomaterials to achieve customized drug release profiles for targeted therapeutic interventions.

Figure 4.

The swelling and degrading characterization of GelMA hydrogels. (a) Swelling curves of the hydrogels. (b) The remaining weight curves of the GelMA hydrogels under enzymatic hydrolysis. (c) The swelling ratio of GelMA hydrogels in PBS at 24 h. (d) The residual mass rate of GelMA hydrogels at 24 h. ns > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Drug release characteristics in vitro

-

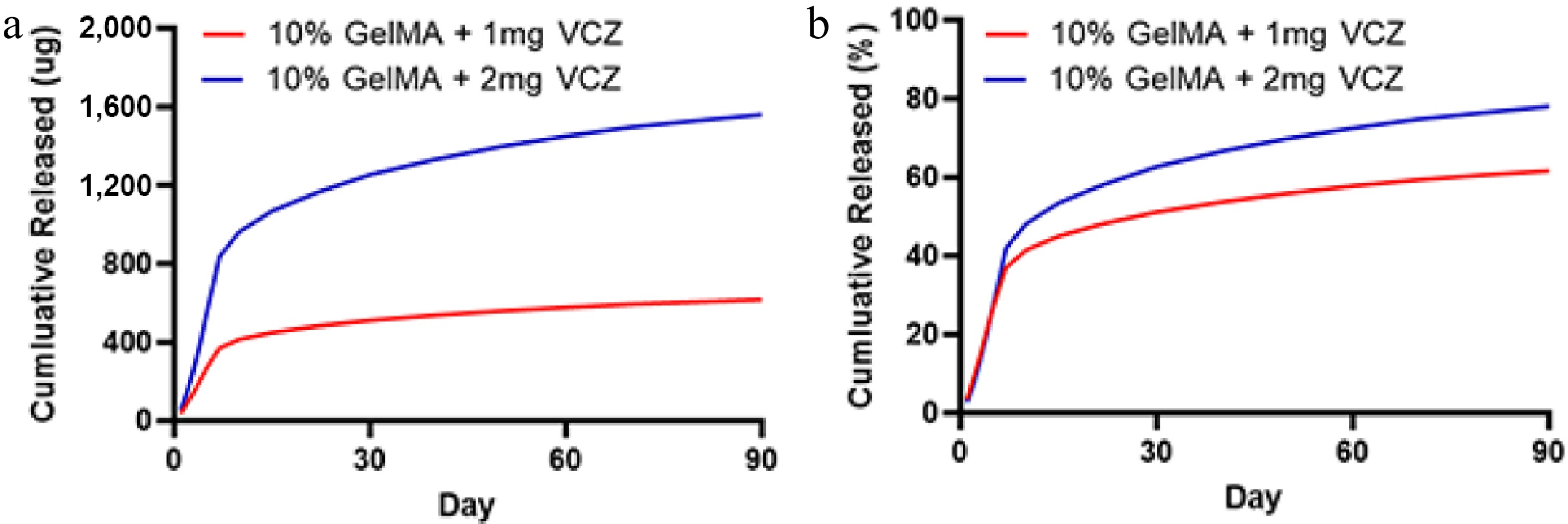

On the basis of the swelling and degradation properties of GelMA hydrogels across varying concentrations, the 10% GelMA hydrogel was chosen for the sustained release of VCZ. The release profiles of VCZ at 1 and 2 mg were examined to assess its sustained-release capabilities. By Day 7, the release rates exceeded 36.99% ± 0.26% and 41.95% ± 0.28%, respectively, for 1 and 2 mg. Subsequently, the release rate of the drug-loaded hydrogel exhibited a steady trend. By Day 90, the cumulative release reached 61.61% ± 0.65% and 78.02% ± 0.63%, respectively, for 1 and 2 mg (Fig. 5). Therefore, the drug-loaded GelMA hydrogel exhibited a more gradual release pattern, suggesting the potential for prolonged therapeutic delivery over a period longer than 90 days.

Figure 5.

The release characteristics of the GelMA hydrogels with VCZ at different concentrations after incubation in drug release media (PBS). (a) The quantification of VCZ released from 10% GelMA hydrogel loaded with 1 and 2 mg after incubation in the drug release media (PBS). (b) The cumulative release rate of VCZ of the drug-loaded hydrogels at 37 °C in PBS.

Cytocompatibility and biocompatibility in vitro and in vivo

-

The live/dead assay detected the viability of HRPE cells cultured on the GelMA hydrogels. Many live HRPE cells were indicated by green fluorescence, with only a few scattered dead cells marked by red fluorescence throughout the observation period. The viability of HRPE cells increased over time and remained over 95% among the three groups after 3 and 5 days of culture (Fig. 6). In addition, HRPE cell proliferation and migration assays were performed in the three groups to assess the compatibility of the hydrogels. The wound healing assay showed a similar migrating rate at 12 and 24 h between the two treatment groups (p > 0.05, t-test, Fig. 7a, b). The CCK-8 assay also showed excellent cell viability between the two treatment groups (p > 0.05, t-test, Fig. 7c).

Figure 6.

The live and dead cells assay after 1, 3, and 5 days of the control, 10% GelMA, and 20% GelMA hydrogels (live HRPE cells are in green and dead HRPE cells are in red).

Figure 7.

Assessment of the cytocompatibility of GelMA hydrogels. (a) Microscopy images of the HRPE cell migration scratch assay at 0, 12, and 24 h. (b) The wound closure rate of cells at 12 h (p > 0.05, t-test). (c) The cell viability was assessed using the CCK8 assay (p > 0.05, t-test). ns > 0.05.

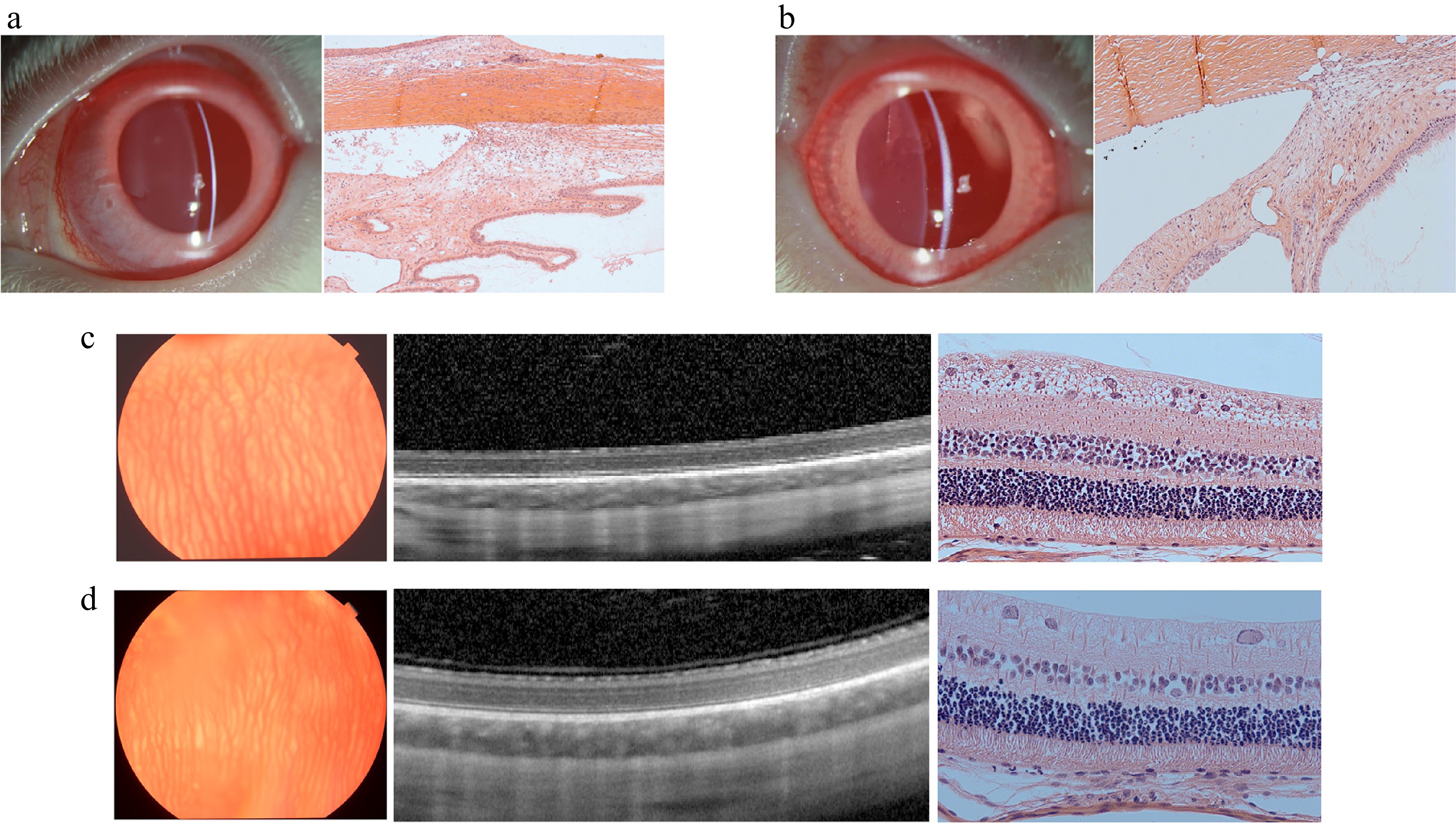

The 10% GelMA hydrogel was injected into the eyes of rabbits to assess its in vivo biocompatibility. Over the two-month experimental period, intraocular pressure remained within the normal range in both the GelMA hydrogel and control groups (p < 0.05, t-test). Additionally, retinal thickness did not differ significantly between the two treatment groups (p < 0.05, t-test). To further evaluate the impact of the GelMA hydrogel on ocular electrophysiological function, we assessed the photopic and scotopic responses of the retina. In both the first and second months, there were no statistically significant differences in these electrophysiological measurements between the hydrogel and control groups (Supplementary Fig. S1). The slit-lamp examination at the end of the experiment revealed no apparent abnormalities in the anterior segment of the eyes treated with hydrogel (Fig. 8a, b). Fundus photography also showed no apparent changes to structures such as retinal blood vessels. Histological analysis of the normal control group demonstrated no apparent abnormalities in the anterior chamber angle or the layered structure of the retina (Fig. 8c, d). Overall, these results indicate that the structures and functions of the eyes injected with GelMA remained normal, suggesting that the hydrogel exhibits good biocompatibility in vivo.

Figure 8.

Images of the biocompatibility in vivo of the control group and GelMA hydrogel group after 2 months. (a) Slit-lamp photo and H&E staining light photomicrographs of the anterior chamber angle in the control (balanced salt solution) group. (b) Slit-lamp photo and H&E staining light photomicrograph of the anterior chamber angle in the 10% GelMA group. (c) Fundus photo, OCT images, and H&E staining light photomicrograph of the retina in the control (balanced salt solution) group. (d) The fundus photo, OCT images, and H&E staining light photomicrograph of the retina in the 10% GelMA group.

-

The present study demonstrated that GelMA hydrogel possesses several distinctive features that suit to be used for long-term controlled drug delivery. The GelMA hydrogel exhibits the appropriate transparency, morphology, mechanical, swelling ratio, and degradation properties. It provides an injectable, biodegradable, and nontoxic platform capable of sustained drug release in the posterior vitreous body, highlighting its potential as an ophthalmic drug delivery system.

SEM analysis revealed highly homogeneous, unconnected pit-like structures, indicating favorable structural stability and a consistent chemical composition. The similar morphological features between the drug-loaded hydrogel and the blank hydrogel suggested that the VCZ was encapsulated within the hydrogel network. Moreover, this pit-like configuration effectively supports the transport and controlled release of the encapsulated drug. Additionally, as the GelMA concentration increased, the pore size gradually decreased, and the denser hydrogel network structure impeded the release of the encapsulated drugs. Previous studies have also confirmed that a higher GelMA concentration results in reduced mesh size, increased stiffness, and decreased permeability[24−26]. The pit-like structure of GelMA hydrogels allows drugs to be encapsulated within it, which can be positioned and aggregated in the appropriate location through photocrosslinking. The FTIR spectra of GelMA hydrogels showed characteristic peaks at 3,296 cm−1 (O–H and N–H stretching) and 1,636 cm−1 (C=O stretching of Amide I), consistent with previous reports and confirming the preservation of functional gelatin groups after methacrylation[27]. TGA revealed concentration-dependent stability, with all hydrogels exhibiting an initial weight loss below 150 °C as a result of water evaporation and major degradation between 250 and 400 °C through decomposition of the polymer backbone. The 20% GelMA hydrogel retained a lower residual mass than the 5% and 10% formulations, indicating that higher methacrylation and polymer content may lead to more complete thermal decomposition. These findings emphasize the influence of the GelMA concentration on the physicochemical properties, providing guidance for designing hydrogels with enhanced stability for biomedical applications.

The evaluation of mechanical properties plays a critical role in the design of implantable hydrogel-based drug delivery systems to ensure both controlled degradability and mechanical stability. Increasing the GelMA concentration from 5% to 20% led to enhanced resistance of the hydrogels against enzymatic degradation. Specifically, 5% GelMA hydrogels exhibited complete degradation in approximately 100 hours, whereas those with 20% GelMA concentrations required nearly 150 hours. The rapid degradation of 5% GelMA is mainly attributed to the loose network structure, lower mechanical strength, and higher porosity, which significantly enhance the accessibility of collagenase to the substrate. In contrast, 20% GelMA has increased polymer density and crosslinking strength, slowing down the enzymatic degradation rate[28−30]. Hydrolytic and enzymatic cleavage of gelatin chains and methacryloyl crosslinks gradually enlarge the hydrogel network, facilitating VCZ's diffusion. The degradation rate can be precisely tuned by adjusting the degree of methacrylation, the polymer concentration, and the crosslinking density, with higher crosslinking slowing release and lower crosslinking accelerating it[9]. Throughout the degradation process, the hydrogels underwent gradual shrinkage without disintegrating into multiple fragments, ultimately disappearing as a whole structure. This degradation behavior is particularly advantageous for intraocular applications, where the formation of small debris particles may obstruct the trabecular meshwork, potentially leading to increased intraocular pressure or other ocular complications[31,32]. GelMA hydrogels exhibit tunable compressive and tensile moduli, offering a versatile range of mechanical properties. Their stiffness aligns closely with the mechanical characteristics of retinal tissue, and the tunable nature of GelMA hydrogels allows adjustment of the mechanical properties to better match the soft viscoelastic characteristics of the vitreous body[23,33]. This mechanical similarity suggests that GelMA hydrogels are well-suited for intraocular drug delivery applications, as their mechanical properties are unlikely to cause retinal damage through excessive rigidity. In the present study, 10% GelMA hydrogel demonstrated a favorable balance between mechanical strength and degradation behavior, making it well-suited for the sustained intraocular release of VCZ. Its moderate crosslinking density provides sufficient structural integrity to withstand the physiological conditions within the eye, while still allowing for gradual enzymatic degradation. This ensures a consistent drug release profile over time, minimizing the risk of burst release or premature breakdown[34]. Therefore, for achieving a balance between mechanical strength and control, intact degradation is essential for ensuring both the efficacy and safety of hydrogel-based drug delivery systems[35].

For intraocular therapies, the easy injectability of a drug delivery system plays a crucial role in its suitability for intraocular administration. Traditional solid or pellet-shaped implants often require specially designed applicators, which are not only expensive but also involve invasive procedures. These systems necessitate the use of large-gauge needles and insertion into the sclera, resulting in greater patient discomfort and potential risks[36,37]. In contrast, GelMA-based hydrogels offer a promising alternative because of their ability to undergo in situ sol–gel transitions. The liquid precursor of GelMA can be injected using standard ophthalmic instruments such as 25-gauge needles and subsequently undergoes rapid gelation under 405-nm visible light for photocrosslinking within 30–60 s. Clinically, a gelation time of 3–5 min is suitable for surgical applications with great visibility during surgery, and less than 1 min is anticipated in vivo[38]. To further evaluate its clinical applicability, we tested the injectability of 10% GelMA using a 30-gauge needle syringe. The results demonstrated that GelMA maintained excellent injectability even through this smaller-gauge needle, confirming its suitability for use in various clinical settings that demand precision and reduced invasiveness. Overall, the mechanical behavior exhibited by the 10% GelMA formulation corresponds closely with the values established in previous studies[39,40], making it stable for ocular drug delivery.

The VCZ was loaded into the GelMA hydrogel to release slowly, and the release pattern of drug-loaded hydrogels was influenced by the degradation of the hydrogel's structure. The release rate of drug-loaded hydrogels with different drug doses significantly and continuously increased within the first week, which could meet the therapeutic goal of effective drug concentrations in the early stage of fungal infection. Within 60 days, the cumulative drug release percentages of 10% GelMA with 1 and 2 mg VCZ were both over 50%. The remaining drug continued to be released in a sustained manner to meet the therapeutic effect. Over 90 days, the drug-loaded hydrogel's release rate of the higher drug dose was faster than that of the lower dose. One potential explanation for this phenomenon is the elevated drug loading content, which correlates with a relatively high release quantity during the release process. VCZ, a hydrophobic drug, may aggregate into particulate forms. Additionally, the spatial distribution of the drug within the hydrogel matrix may significantly influence the rate of drug release[41]. Overall, the GelMA drug-loaded hydrogel can achieve > 90 days of controlled release inside the eye, which is significant for the treatment of intraocular fungal infections.

The cytotoxicity of hydrogels is critical for their application for intraocular drug delivery. The viability of HRPE cells was detected by the CCK-8 test, live/dead staining, and a wound healing assay to evaluate the GelMA's cytotoxicity in the present study. In all groups, many HRPE cells labeled with green fluorescence were observed across the field of view, with only a few dead HRPE cells identified by red dots. In addition, the viability of HRPE cells increased over time. The CCK-8 assay results further confirmed that the GelMA hydrogels exhibited little cytotoxicity to cells in vitro. We performed an OCT examination and H&E staining to evaluate inflammation levels following hydrogel implantation in vivo. The ERG demonstrated that both photopic and scotopic functions showed no abnormal changes at 1 and 2 months after implantation in rabbits. The control and GelMA hydrogel groups exhibited no disorganized microstructure, inflammatory cell presence, hemorrhage, or edema in the ciliary and retinal tissues across all examined sections. Overall, the functional and structural evaluations further confirmed that the novel hydrogel holds significant promise as a vitreous implant for drug delivery applications.

The GelMA hydrogel presented in this study offers distinct advantages for intraocular drug delivery compared with both polysaccharide-based injectable hydrogels and and polymeric implant systems such as poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA). The acylhydrazone-derived whole pectin-based hydrogel demonstrates good syringeability, self-healing capacity, and short-term chemotherapeutic delivery, but lacks the long-term release profile required for treating ocular infections[42]. PLGA-based implants, such as the commercially available Ozurdex® (dexamethasone-loaded PLGA), enable the extended release of small molecules over several weeks[43]. However, PLGA degrades hydrolytically into lactic and glycolic acids, resulting in an acidic microenvironment that can trigger local inflammatory responses[44,45]. In contrast, the GelMA hydrogel with VCZ forms a stable covalent network through rapid visible-light photopolymerization, allowing for fine control over the mechanical properties and degradation rate while maintaining high transparency to avoid visual disturbance. Notably, this system achieves sustained therapeutically effective VCZ release for over 90 days, significantly exceeding the duration of the pectin-based hydrogels and avoiding the acidic degradation issues of PLGA[26,46].

In conclusion, this study has revealed the properties of an injectable, photocrosslinkable, biocompatible GelMA hydrogel designed for the sustained release of VCZ to the intraocular vitreous body. This GelMA-loaded drug hydrogel offers the potential to enhance patient adherence and enable more practical long-term therapeutic applications. Furthermore, the injectable GelMA hydrogel holds promise for further development and adaptation as a long-term and nontoxic controlled delivery system.

This work was supported by grants from the Guangzhou Municipal University Joint Funding Project (2025A03J4030).

-

The in vitro study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center, Sun Yat-sen University (Approval No. 2022KYPJ246, approval date: 17 January 2023). All the animal experiments were approved by the Institution Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center (IACUC No. 2022005, approval date: 20 July 2022) and were conducted in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. The research followed the "replacement, reduction, and refinement" principles to minimize harm to the animals. This study involved the use of primary human cells from the eye bank of Zhongshan Ophthalmic Center (Approval No. 2018KYPJ034, approval date: 1 March 2018).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Jiang Z, Shen C, Hu J; data collection: Jiang Z, Shen C, Su K, Wang Y, Ma S, Xie J; analysis and interpretation of results: Jiang Z, Shen C, Hu A, Hu J; draft manuscript preparation: Jiang Z, Shen C, Hu A, Hu J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Zhihao Jiang, Chaolan Shen

- Supplementary Fig. S1 The retinal function assessment of rabbits using ERG (a) The amplitudes of photopic b-wave and 30Hz after 1 and 2 months with the GelMA Hydrogel. (b) The scotopic b-wave during the experiment.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang Z, Shen C, Su K, Wang Y, Ma S, et al. 2026. An injectable gelatin methacryloyl hydrogel for long-term intraocular drug delivery of voriconazole. Visual Neuroscience 43: e002 doi: 10.48130/vns-0025-0028

An injectable gelatin methacryloyl hydrogel for long-term intraocular drug delivery of voriconazole

- Received: 28 June 2025

- Revised: 20 August 2025

- Accepted: 02 September 2025

- Published online: 22 January 2026

Abstract: Injectable hydrogels have emerged as promising candidates for intraocular drug delivery systems, but achieving long-term controlled release with minimal cytotoxicity remains challenging. In this study, an injectable hydrogel based on gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) with favorable physical properties was fabricated via visible-light-induced crosslinking. Morphology and transparency properties were characterized using scanning electron microscopy and an ultraviolet spectrophotometer. Structural features and thermal stability were further characterized by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and thermogravimetric analysis. Mechanical, swelling, and degradation behavior were assessed across different GelMA concentrations. Voriconazole (VCZ) was selected as a model antifungal agent. The drug release kinetics and biocompatibility were also evaluated. The hydrogel exhibited a pit-like microstructure (16.9 ± 3.24 μm at 10% and 12.00 ± 3.04 μm at 20%) and maintained > 90% transparency throughout the visible spectrum. Mechanical testing across different concentrations revealed maximum compressive and tensile moduli ranging from 4.34 ± 0.24 to 80.33 ± 23.79 kPa and from 4.14 ± 5.39 to 123.89 ± 21.62 kPa, respectively. The maximum swelling ratios were 31.23% ± 0.77% to 15.54% ± 0.68%, and enzymatic degradation was observed over 4 days. The GelMA/VCZ hydrogel demonstrated sustained drug release for over 90 days, achieving sustained and therapeutically effective drug release. Live/dead cell staining, a wound healing assay, and Cell Counting Kit-8 assays confirmed excellent cytocompatibility with the viability of human retinal pigment epithelial cells exceeding 95%. Biocompatibility studies in vivo revealed no observable damage or inflammation in ocular tissues following intravitreal injection after 2 months. In conclusion, the GelMA hydrogel is a promising candidate for long-controlled drug delivery, particularly in treating intraocular infections such as fungal endophthalmitis.

-

Key words:

- GelMA hydrogel /

- Intraocular drug delivery /

- Voriconazole