-

Cotton (Gossypium spp.) is the most widely cultivated fibre crop on all continents of the world, except for the Antarctic, and is cultivated in more than 60 countries[1]. Cotton fibre serves as a raw material for textile industries with an annual economic value worth more than USD

${\$} $ Generally, climatic factors (rainfall, number of rainy days, temperature, relative humidity, sunshine hours, light, and wind) affect the growth of cotton because they interact with other environmental factors such as nutrient availability in soil, cultivar, soil moisture, and agronomic practices to affect cotton growth[7,8]. In recent decades, climate change has been reported to affect the phenological phases of cotton[9,10]. Globally, integrated approaches to reduce the losses attributable to climate change are being developed while tackling other traditional challenges to crop production[11,12]. A combination of crop rotation and early warning systems (EWS) were recently recommended as a highly promising archetype for achieving the objectives of the CSA in tropical Africa[13]. The Early Warning System (EWS) is a general agricultural alert system that provides reliable and early information on agricultural impacts induced by climate change[14]. It is a system designed to monitor changes in weather patterns, climate conditions, and environmental factors that can engender agricultural losses[4]. The system is to predict and provide timely alerts about adverse agricultural conditions, such as droughts, floods, or pest outbreaks[15]. To achieve this, it integrates satellite-derived climate data, information from weather stations, and predictive models to help farmers make informed decisions and mitigate risks[16]. Establishing a robust near-real-time climate information service system together with crop rotation practices will enhance the overall stability and productivity of cotton farming in the humid tropics.

Crop rotation has been described as a veritable strategy to achieve one of the principles of agroecology aimed at enhancing the recycling of biomass, optimizing nutrient availability, and balancing nutrient flow[17]. A recent study concluded that cotton demonstrated an increase in yield when planted after soybean due to increased levels of soil N through fixation from the preceding soybean crop or an alteration of soil microbial populations favourable to the succeeding cotton crop[18]. Crop yields have been improved further by introducing longer rotations, such as the addition of a third crop to the rotation, and reported yield increases attributed to greater residue diversity and improvement in soil conditions[19], and alleviation of some of the problems associated with no-till[20]. Unfortunately, the bulk of conventional cotton is produced under a continuous cropping system that often records an increase in the prevalence of soil-borne diseases which is directly linked to the increase of the pathogen abundance[21] and reduction in the abundance of beneficial soil organisms over time[22], which are essential to soil fertility, health, and crop yield. Organic fertilizer application to cotton can help alleviate some of these problems because organically bound nutrients are held more tightly in soil than nutrients obtained from mineral fertilizers; therefore, their chances of losses by volatilization and leaching are far less[23].

This study was therefore carried out to determine the agronomic performance of cotton sown after sowing soybeans and sesame under different cropping systems in an organic crop rotation scheme under prevailing climatic conditions in a humid tropical location.

-

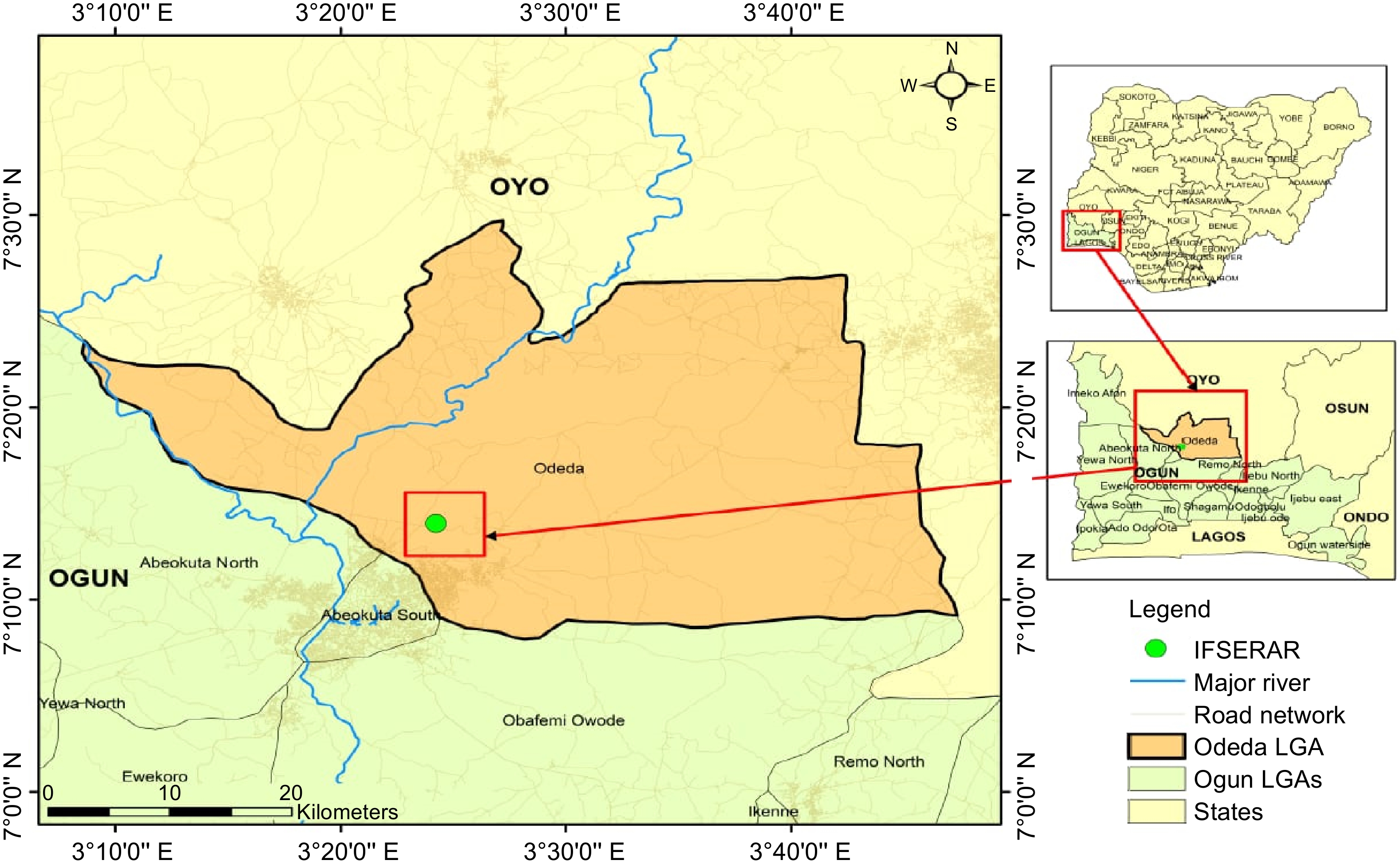

The study was conducted at the Organic Research Plots of the Institute of Food Security, Environmental Resources and Agricultural Research (IFSERAR) of the Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta (Nigeria). The farm is located within (7°13'51.17'' N and 7°13'53.16" N and longitudes 3°23'49.12" E and 3°23'51.86" E, at an altitude of 131.5 m above sea level). Figure 1 shows a map of the project area.

Figure 1.

Map of the experimental plots at the Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Nigeria.

Growth conditions during the experimental period

-

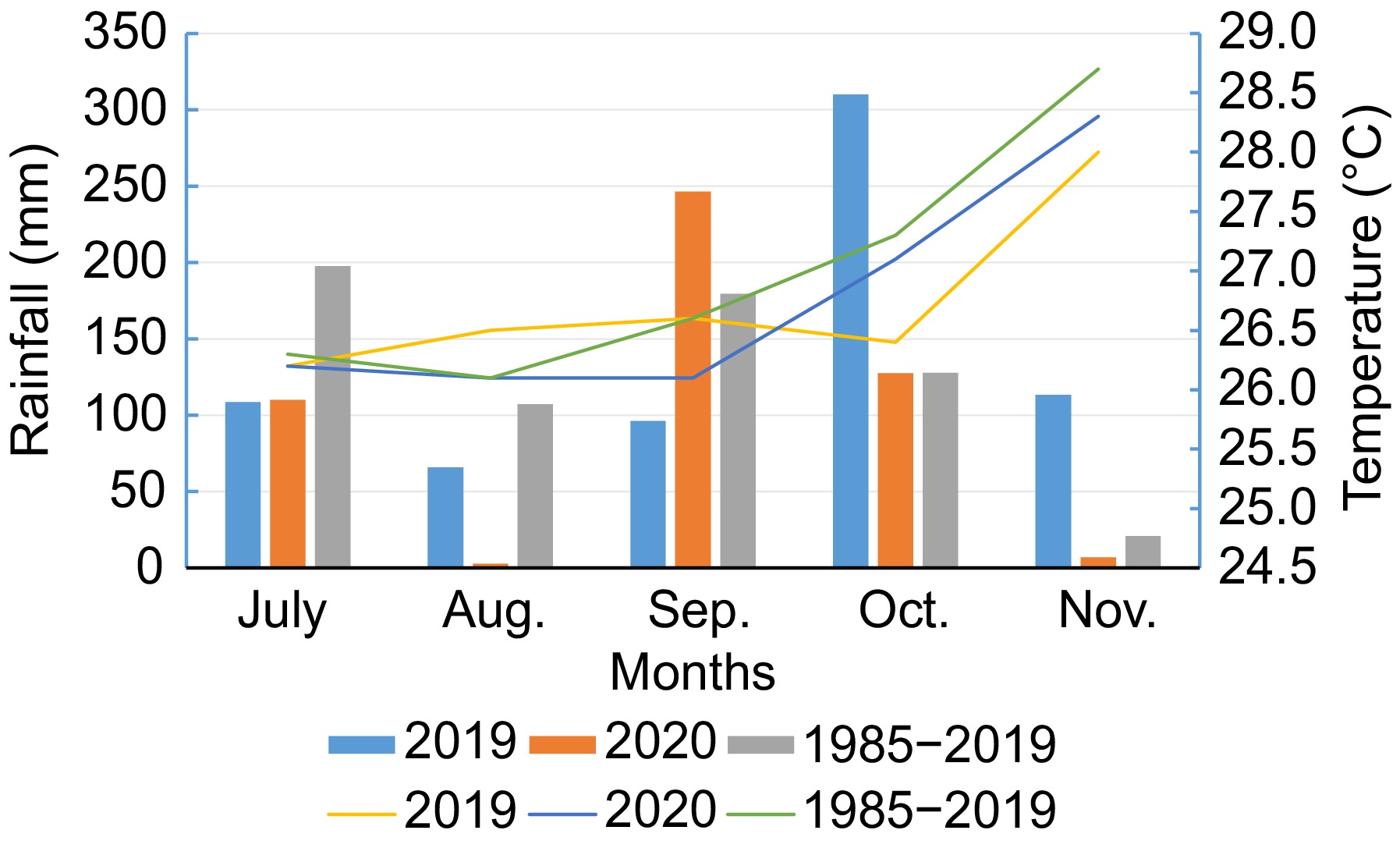

The rainfall pattern in the study area is bimodal with two peaks in July and September and a dry spell in August termed the 'August break'. However, the two peaks were recorded in June and October in 2019 and June and September in 2020. During the experimental period, a total rainfall of 693.1 and 493.3 mm were recorded in 2019 and 2020, respectively. The experiment was carried out during the late cropping seasons (July−December) of 2019 and 2020 (Fig. 2). The textural class of the soils under the cropping systems was loamy sand, except for the soil under continuous cropping (CS1) without organic fertilizer which was sandy in both years (Tables 1 & 2). The pH of the soils under the various cropping systems was slightly acidic, especially in 2019 and 2020, all the cropping system soils had slightly alkaline pH values with CS2 and CS4 having the highest values of 7.4. The nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and organic carbon contents of the soils across the cropping systems were generally low in both years (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Monthly rainfall distribution and mean temperature during the experimental periods (July−November 2019 and 2020) and the long-term (1985−2019) at the Federal University of Agriculture Abeokuta, Nigeria.

Table 1. Pre-cropping physical and chemical properties of the soil in 2019.

Soil

compositionContinuous cropping

(−OF) (CS1)Continuous cropping (+OF) (CS2) Rotation (+OF) (CS3) Rotation

(−OF) (CS4)Conventional

(CS5)Mechanical composition (g/kg) Clay 65 85 85 85 65 Silt 35 45 45 25 65 Sand 900 870 870 890 870 Textural classification Sand Loamy

sandLoamy sand Loamy sand Loamy

sandpH 6.6 6.9 6.5 6.9 6.8 Total N (g/kg) 0.97 0.94 0.77 0.84 0.59 OC (g/kg) 9.5 5.4 10.4 8.4 13.4 P (mg/kg) 2.56 4.87 23.59 3.01 3.64 Exchangeable cation (cmol/kg) K 0.12 0.06 0.08 0.09 0.12 Ca 3.89 2.89 2.99 3.39 4.59 Mg 1.74 1.48 1.63 1.96 1.81 Na 0.49 0.34 0.39 0.30 0.59 Micronutrient (mg/kg) Mn 264 280 356 288 299 Fe 12 12 12 10 14 Zn 51 54 51 52 51 OC: organic carbon. Table 2. Pre-cropping physical and chemical properties of the experimental site in 2020.

Soil

compositionContinuous cropping

(−OF) (CS1)Continuous cropping (+OF) (CS2) Rotation (+OF) (CS3) Rotation

(−OF) (CS4)Conventional

(CS5)Mechanical composition (g/kg) Clay 37.8 1.00 16.1 19.0 18.0 Silt 40.5 149.8 100 151.1 163.5 Sand 958.5 833.7 879.3 834.3 798.7 Textural classification Sand Loamy

sandLoamy

sandLoamy

sandLoamy

sandpH 7.3 7.4 7.3 7.4 7.2 Total N (g/kg) 0.82 0.53 0.87 0.81 0.92 OC (g/kg) 9.6 6.2 10.2 9.4 10.6 P (mg/kg) 35.68 45.42 37.51 61.86 40.55 Exchangeable cation (cmol/kg) K 0.34 0.36 0.69 0.41 0.36 Ca 0.98 1.52 2.29 1.68 1.51 Mg 1.04 1.08 1.79 1.21 1.13 Na 0.17 0.18 0.29 0.18 0.18 Micronutrient (mg/kg) Mn 4.29 4.68 7.35 4.52 4.20 Fe 9.10 10.22 10.70 7.35 8.00 Zn 5.61 7.23 9.69 7.28 6.81 OC: organic carbon. Experimental design and treatments

-

The experiment was performed in a Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) and replicated three times. The five cropping systems evaluated were as follows: a. CS1 - Continuous cropping (without organic fertilizer); b. CS2 - Continuous cropping (with organic fertilizer); c. CS3 - Rotation (with organic fertilizer); d. CS4 - Rotation (without organic fertilizer); e. CS5 - Conventional system (60 kg N, 56 kg P2O5 and 60 kg K2O and herbicide application).

The test varieties of the experimental crops were as follows: Cotton - Samcot 11, an erect type, lobed land glanded leaves, slightly conical bolls, a long staple, with a potential yield of seed cotton at 2.5 t/ha, mean fibre length of 26.5−27.5 mm and late maturing variety[24]; soybean - TGx 1448-2E, a medium maturing, pod shattering resistant and high yielding variety[25] and sesame - E-8 variety, a drought-tolerant, good seed quality, with a 1,000-seed weight > 3.0 g and high yield[26]. Sowing was performed on July 10, 2019, and July 24, 2020.

Soil sampling and analysis

-

Before planting each year, soil samples were collected from the experimental field on a cropping system basis for routine soil analysis to determine the physical and chemical properties of the soil.

Crop husbandry

-

Each year, the experimental field was ploughed twice at two-week intervals and subsequently harrowed one week later. The crops were sown in their respective plots using the following row spacings: soybean - 60 cm × 5 cm, sesame - 60 cm × 5 cm, and cotton - 90 cm × 40 cm. Weeding was performed at 3, 6, and 9 weeks after sowing (WAS). Five plants (cotton) were randomly selected and tagged at 5 WAS from the net plot for plant height and yield attribute measurements on a plot basis. The experiment was carried out under rain-fed conditions. The organic fertilizer used was Aleshinloye Grade B (an abattoir-based fertilizer) which was applied at 3 WAS using the side dressing method at the rate equivalent to the recommended nitrogen level (60 kg N/ha) while the inorganic fertilizer was applied to the conventional system at 3 WAS at the rate of (60 kg N, 56 kg P2O5, and 60 kg K2O). The organic fertilizer contained 10.96 g/kg N, 0.01 g/kg P, and 6.30 g/kg K in 2019 and 12.30 g/kg N, 3.37 g/kg P, and 2.01 g/kg K in 2020. In 2018 and 2019, soybean and sesame were planted as preceding crops for cotton grown in 2019 and 2020, respectively.

Data collection

-

The rainfall distribution, monthly mean temperature, sunshine hours, and relative humidity were used as proxies for weather variations. Five plants (cotton) were randomly selected and tagged at 5 WAS from the net plot for plant height and yield attribute measurements on a plot basis. Data were collected on the following parameters: plant height (cm) at harvest was measured as height from the soil surface to the apex of the plant, which was measured with a metre rule; number of sympodia branches (primary) as the total number of the fruiting branches which was carried out by visual counting; number of monopodia branches (secondary) as the total number of the vegetative branches which was done by visual counting; total number of branches by counting the number of branches per plant and the mean average determined; number of bolls per plant (NBOLLS) by counting the number of bolls for each tagged plant at harvest and the average determined; weight (g) of seed cotton per plant (SCWT) was weighed after the bolls were detached from the cotton plant and they contained both the seeds and the lint; number of seeds per open boll (NSEED), weight (g) of seeds (SEEDWT) the seeds were weighed after the seeds have been detached from the lint from the tagged plants; weight (g) of lint (WTLINT) per plant this was weighed after the lint has been detached from the seed, and cotton seed yield (kg/ha) was computed from seed cotton yield per plot and converted to a unit area. Weighing of all the samples was carried out using a sensitive scale (ATOM A – 120 with maximum capacity of 10 kg).

Statistical analysis

-

All data collected were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test the significance of the cropping system effects using the MSTATC package[27]. When the cropping system effects were significant (p < 0.05), the means were separated using the least significant difference (LSD) method at the 5% probability level.

-

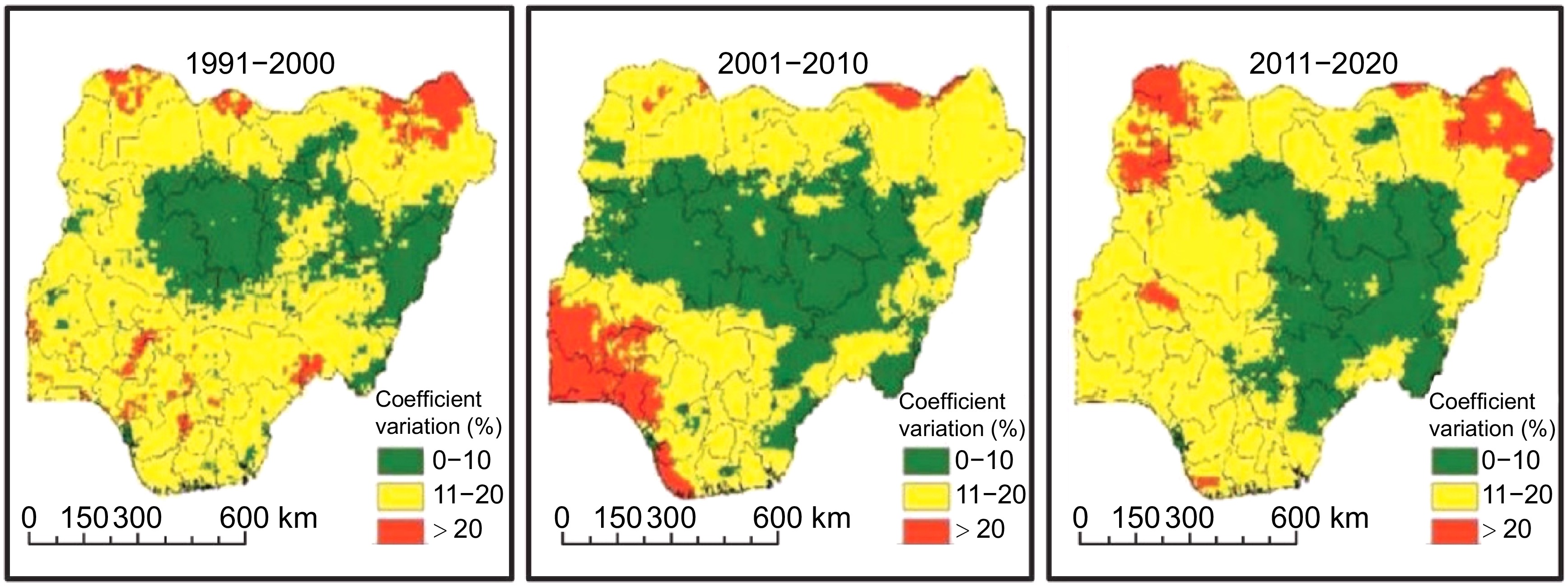

The agronomic performance of crops, especially under rain-fed conditions, is largely affected by prevailing weather conditions and water is the major limiting growth resource[28]. The rainfall distribution was more favourable in 2019 (693.1 mm) than in 2020 (493.3 mm) as shown in Table 3. The mean long-term (35 years) average of 632.8 m only compared favourably with the 2019 rainfall and the recommended water requirement of 700–1,300 mm for good cotton crops[29]. The number of rainy days recorded in 2019 and 2020 late cropping seasons were 53 and 32 d, respectively (Table 3). Water has been reported to be critical to cotton seed and lint yield[30]. Moisture is most critical for cotton from the square (flower bud) stage to the first bloom and first boll opening stages. During this critical period, cotton vegetation growth is rapid, and the number of potential fruiting sites is high[29]. In our study, the critical period occurred approximately 45 d after sowing (DAS), and the cotton plants were able to escape the prolonged dry spell of August 2020, since sowing was done on July 24, 2020. The beginning of the critical period coincided with a wetter September (246.3 mm) in 2020 compared with 96.3 mm in 2019. Similarly, the mean monthly temperature ranges of 26.2−26.5 °C, in 2019 and 25.7−28.3 °C, in 2020 compared well with the recommended temperature range of 15–32 °C[7]. At higher temperatures, cotton plants are likely to experience inhibited photosynthesis[31] and at temperatures above 32 °C, boll growth decreases significantly and boll shedding can set in[32]. However, these high-temperature conditions were not experienced during flowering and boll formation in our study. Sunshine hours have been reported as an effective climatic factor during and preceding and succeeding periods of boll production[33]. In our study, sunshine hours recorded in 2019 (13.6 h) and 2020 (17.7 h) during the late cropping seasons were not limiting (Table 3). Figure 3 illustrates the coefficient of variation (CV) of rainfall patterns during Nigeria's primary growing season (June−September) for the last 30 years. Most states in Nigeria experienced CV beyond 10%, meaning there are uncertainties in the rainfall patterns. The decade 1991−2000 was remarkably volatile, with almost the entire country exhibiting CV in the range of 11% to 20% as indicated in the map. A higher CV indicates more erratic rainfall, while a lower CV reflects a more stable and consistent rainfall pattern within a given period. A location with a CV of 10% suggests that erratic rainfall occurs once every 10 years, and a CV of 20% implies that extremities and uncertainties in rainfall are experienced two out of every five years.

Table 3. Some weather parameters during the late cropping season (July–November) in 2019 and 2020.

Parameters July Aug Sept Oct Nov Total Long term rainfall 2019 2020 2019 2020 2019 2020 2019 2020 2019 2020 2019 2020 35 years Mean temperature (°C) 26.2 25.7 26.5 26.2 26.6 26.1 26.4 27.1 27.9 28.3 141.2 133.4 − Total rainfall (mm) 108.7 109.5 65.8 2.9 96.3 246.31 310 127.6 112.3 7.0 693.1 493.3 632.8 Number of rainy days 11 8 8 1 10 11 19 11 5 1 53 32 − Relative humidity (%) 87.4 82.5 83.4 80.0 85.7 79.0 84.0 71.8 86.9 69.1 427.4 382.4 − Sunshine (h) 2.2 2.3 2.5 3.2 2.0 2.9 1.7 3.8 5.2 5.5 13.6 17.7 − Source: Department of Agro Meteorology and Water Management, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Nigeria.

Figure 3.

The coefficient of variation of rainfall during the growing season in Nigeria for three decades.

These rainfall uncertainties are particularly noticeable in the South-western region, during the 2001 to 2010 period and in the North-west and North-east regions during 2011 to 2020, where the CV exceeded 20%. The average number of wet and dry days per year for all Agro-Ecological Zones in Nigeria during the last three decades revealed that the Arid/Sahel (AS) and Semi-Arid (SA) zones in the north recorded significantly fewer wet days compared to dry days, making them suitable for growing short-duration crops like millet, cowpea, and sorghum. Conversely, the Humid Forest (HF) and derived Savanna (DS) zones in the south (which describes the ecology of our project site), have slightly more wet days than dry. This derived savanna region has consistently stable rainy days ranging from 127.5 to 129.1 d over the last four decades compared to other AEZs (Table 4). The derived Savannah zone should therefore be ideal for producing fibre crops like cotton.

Table 4. Mean annual rainy days (MAnRD) and Mean annual dry days (MAnDD) in the agroecological zones (AEZs) from 1991 to 2020.

AEZs 1991−2000 2001−2010 2011−2020 MAnRD MAnDD MAnRD MAnDD MAnRD MAnDD AS 56.2 309.1 56.9 308.3 58.6 306.7 SA 83.1 282.2 84.3 280.9 84.9 280.4 NGS 107.1 258.2 106.9 258.3 107.8 257.5 SGS 115.1 250.2 114.1 251.1 115.2 250.1 HA 184 181.3 177.7 187.5 181.6 183.7 MA 138.4 226.9 135.8 229.4 139.5 225.8 DS 127.5 237.8 127.8 237.4 129.1 236.2 HF 161 204.3 162.3 202.9 167.4 197.9 AS: Arid/Sahel; SA: Semi-Arid; NGS: Northern Guinea Savanna; SGS: Southern Guinea Savanna; HA: High Altitude; MA: Mid Altitude; DS: Derived Savanna; HF: Humid Forest; MAnDD: Mean Annual Dry Days; MAnRD: Mean Annual Rainy Days. The connection between adopting a crop rotation system involving sesame and soybean with organic fertilizer and establishing a near-real-time climate information service lies in enhancing the resilience and productivity of cotton production under changing weather conditions. Cotton grows best in rich soils and under optimum weather conditions. Access to virgin land in tropical Africa is a challenge, hence there is the need to effectively manage the land used for continuous production. Since crop rotation and organic fertilizer application improve soil health and reduce pest and disease pressures, it is logical to adopt the system for sustainable productivity. Meanwhile, the farmers also require clear guidance in the timing of farming operations, fertilizer application, and harvesting dates. Thus, allowing them to adapt more effectively to weather variability and reduce potential crop losses. A robust climate information service is required to provide timely information that can guide farmers decisions.

Cotton agronomic traits and seed cotton yield

-

Cotton plants tend to experience inhibited photosynthesis[33], boll growth decreases significantly, and boll shedding at high temperatures above 32 °C[34]. However, these high-temperature conditions in our study did not affect flowering or boll formation. Similarly, sunshine hours affect boll production[31]. In our study, sunshine hours recorded in 2019 (13.6 h) and 2020 (17.7 h) during the late cropping seasons were not limiting (Table 3).

At maturity in 2020, cotton plants under CS2, CS3, and CS5 were significantly taller than those from CS1 and CS4 (Table 5). This finding is similar to that of Kumbhar et al.[35], Rochester et al.[36], and Ndor et al.[37] that the plant height of cotton plants is related to nitrogen application. In both years, all the cotton plants grown under CS2, CS3, CS5, or CS4 produced more sympodia branches than the cotton under CS1. A similar trend was reported for cotton grown in legume rotation with nitrogen application[35]. The number of bolls per plant increased in response to the application of fertilizer (CS2, CS3, and CS5) and crop rotation (CS4) in 2019. Apparently, the applied fertilizers and nutrients from the preceding soybean in 2018 enhanced the production of fruiting bolls by the plants. Earlier reports have shown an increased number of bolls per plant following the application of nitrogen fertilizer and the incorporation of preceding legume crops[38] and cotton sown after soybean in a soybean, corn, and cotton rotation[18]. Similarly, Ndor et al.[37] reported a linear increase in the number of bolls per plant as the nitrogen application rate increased from 30 to 90 kg in the southern Guinea savannah in Nigeria.

Table 5. Effects of cropping system on plant height (cm) at maturity, number of synpodia, monopodia, and total branches of plant, and bolls per plant in 2019 and 2020.

Cropping system 2019 2020 PHTMAT (cm) NSYPB per plant NMONB NTBR NBOLLS PHTMAT (cm) NSYPB per plant NMONB NTBR NBOLLS CS1 86.1a 11.4c 1.1a 12.5c 13.6c 54.8c 12.6c 0.4a 13.0a 9.1c CS2 109.6a 14.7ab 1.0a 15.8b 24.3a 79.6ab 15.7ab 0.7a 16.4a 11.7bc CS3 109.1a 14.3b 1.5a 15.8b 24.2a 85.9a 15.6ab 1.3a 16.9a 17.6a CS4 105.3a 14.0b 1.5a 15.5b 22.3ab 67.0bc 14.7b 0.6a 15.3a 9.8c CS5 113.1a 16.9a 2.3a 19.2a 21.2b 87.0a 17.0a 1.5a 18.6a 13.5b LSD 5% ns 2.28 ns 2.26 2.26 16.90 1.98 ns ns 2.90 CS1 - Continuous cropping (without organic fertilizer), CS2 - Continuous cropping (with organic fertilizer), CS3 - Rotation (with organic fertilizer), CS4 - Rotation (without organic fertilizer) and CS5 - Conventional system (60 kg N, 56 kg P2O5 and 60 kg K2O, and herbicide), ns: not significant, LSD: least significant difference, PHTMAT: Plant height at maturity, NSYPB: Number of synpodia branches, NMONB: number of monopodia branches, NTBR: number of total branches, NBOLLS: Number of bolls. Means followed by the same alphabeths are not significantly different from each other based on the leaset significance difference test at 5% probability level. In our study, CS3 and CS4 increased the seed cotton weight per plant in both years (Table 6). This could be attributed to the significant role played by nitrogen in enhancing the photosynthetic activity of the plants and the partitioning of photosynthates from the leaves to the seeds of cotton plants grown on CS2, CS3, and CS4. The slow release of nutrients by the organic fertilizer and crop residues incorporated into the soil could have contributed to the observed trend as suggested by Pettigrew et al.[18], Kumbhar et al.[35], and Olowe & Adejuyigbe[17]. The weight of the seeds per plant of cotton followed a trend similar to that of the seed cotton weight. Nitrogen is crucial to cotton seed yield[38−40] and the cropping systems that received organic fertilizer application significantly enhanced cotton seed yield relative to the CS1 and CS5 in both years. During the wetter year (2019), the seed cotton yield of cotton plants under CS2, CS3, and CS4 ranged between 631.9 and 677.8 kg/ha (Table 6). However, in 2020, the yield under similar cropping systems ranged between 541.8 and 784.8 kg/ha. These values are slightly lower than the Nigerian average of 842.8 kg/ha and less than the African average of 1,044 kg/ha and the global average of 2,137 kg/ha according to FAOSTAT[3]. The markedly high world seed cotton yield could be attributed to the inclusion of the yield of genetically modified organism (GMO) cotton (e.g. Bt cotton). A seed yield of 3,395 kg/ha of Bt cotton was reported following the use of drip irrigation combined with bio-fertigation of a liquid formulation[11].

Table 6. Effects of cropping system on seed cotton weight (g), weight of seeds (g), weight of lint (g), and seed cotton yield (kg/ha) in 2019 and 2020.

Cropping system 2019 2020 SCWT WTSEEDS WTLINT SCYD SCWT WTSEEDS WTLINT SCYD CS1 7.3a 5.3b 2.0a 204.96b 8.6b 6.3c 2.5c 230.44c CS2 22.5a 16.0a 6.4a 631.95a 19.3a 12.1b 6.4b 541.80b CS3 24.1a 18.9a 5.1a 675.08a 25.7a 18.1a 8.2ab 692.16ab CS4 24.2a 19.3a 4.8a 677.88a 28.0a 20.1a 9.3a 784.56a CS5 11.3a 5.8b 5.5a 318.40b 9.7b 5.8c 3.2c 272.72c LSD 5% 4.35 3.75 ns 122.048 7.90 4.06 2.55 207.380 CS1 - Continuous cropping (without organic fertilizer), CS2 - Continuous cropping (with Organic fertilizer), CS3 - Rotation (with Organic fertilizer), CS4 - Rotation (without organic fertilizer) and CS5 - Conventional system (60 kg N, 56 kg P2O5 and 60 kg K2O, and herbicide), ns: not significant, LSD: least significant difference, SCWT: Seed cotton weight, WTSEEDS: Weight of seeds, WTLINT: Weight of lint, SCYD: Seed cotton yield. Means followed by the same alphabeths are not significantly different from each other based on the leaset significance difference test at 5% probability level. -

Compared with the continuous cropping system without fertilizer (CS1), the crop rotation system plus organic fertilizer application (CS3), crop rotation without organic fertilizer application (CS4), and continuous cropping with organic fertilizer application (CS2) increased the number of bolls per plant (24.3, 23.2, and 22.3), seed weight (16.0, 18.9, and 19.3 g) and greater seed yield (631.96, 675.08, and 677.88 kg/ha) than did cotton plants under CS1, respectively in 2019. A similar trend was recorded in 2020, except for the number of bolls per plant. With respect to climate variability, drought scenarios were recorded in the derived savanna region (study area) in both years with wet days ranging from 127.5 to 129.1 d over the last three decades. The late cropping seasons of 2019 and 2020 recorded 53 and 32 rainy days, respectively. It is therefore, recommended that cotton can be cultivated in rotation schemes involving soybean and sesame with (CS3) or without (CS4) the application of organic fertilizer and under continuous cropping with organic fertilizer application (CS2) for enhanced food security and soil sustainability in the forest–savanna transition zone of Nigeria. The cultivation of crops such as cotton on a commercial scale in this agroecological zone will require a robust near real-time climate information service to guide prospective farmers on when to grow cotton.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conceptualization: Olowe VIO; methodology, and supervision: Ijaodola OE, Olowe VIO; data curation: Ijaodola OE, Olowe VIO, Adejuyigbe CO; data analysis: Ijaodola OE, Oyedepo JA; formal analysis: Olowe VIO, Adejuyigbe CO; field experiment: Ijaodola OE; Enikuomehin OA; investigation: Odedina JN; draft manuscript preparation: Olowe VIO, Oyedepo JA; manuscript reviewing and editing: Olowe VIO, Enikuomehin OA, Adejuyigbe CO, Odedina JN. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors would like to sincerely express our profound gratitude to the technical staff of the Institute of Food Security, Environmental Resources and Agricultural Research (IFSERAR) for their support and assistance in preparing the land for the experiment and the management of the Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta (FUNAAB) for providing all the farm equipment and implements used for the research. We are also grateful to the staff of Crop Research Programme for their technical support in the field.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Ijaodola OE, Olowe VIO, Oyedepo JA, Enikuomehin OA, Adejuyigbe CO, et al. 2025. Cotton (Gossypium hirsirtum L.) production under an organic crop rotation system and weather vagaries in the humid tropics. Technology in Agronomy 5: e005 doi: 10.48130/tia-0024-0033

Cotton (Gossypium hirsirtum L.) production under an organic crop rotation system and weather vagaries in the humid tropics

- Received: 02 September 2024

- Revised: 06 November 2024

- Accepted: 19 November 2024

- Published online: 04 March 2025

Abstract: Climate change is an established challenge to global agricultural productivity. This two-year study evaluated the effects of five cropping systems on the agronomic performance of cotton in the humid tropics. Field trials were carried out during the late cropping seasons (July–December) of 2019 and 2020 on the Organic Research plot of the Institute of Food Security, Environmental Resources and Agricultural Research, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Nigeria. Five cropping systems: continuous cropping without organic fertilizer (CS1), continuous cropping with organic fertilizer (CS2), crop rotation with organic fertilizer (CS3), crop rotation without organic fertilizer (CS4), and conventional cropping (CS5) were evaluated in a randomized complete block design and replicated three times. Sesame and soybeans were the preceding crops. The weather vagaries were described during the cropping seasons. In 2019, cotton plants under CS2, CS3, and CS4 produced significantly (p < 0.05) greater number of bolls per plant (24.3, 23.2, and 22.3), seed weight (16.0, 18.9, and 19.3 g), and greater seed yield (631.96, 675.08 and 677.88 kg/ha) than did cotton plants under CS1, respectively. A similar trend was recorded in 2020, except for the number of bolls per plant. Number of rainy days was 53 and 32 in 2019 and 2020, respectively. Prospective cotton growers in the region can adopt cotton production in rotation schemes that involve sesame and soybeans with (CS3) or without (CS4) the application of organic fertilizer and continuous application of organic fertilizer (CS2). A robust near real-time climate information service to aid farmers in their production activities is recommended.

-

Key words:

- Climate /

- Conventional /

- Cotton seed yield /

- Cropping system /

- Organic cotton /

- Crop rotation