-

Weedy rice (Oryza spp.), a conspecific weed of cultivated rice, has emerged as one of the most challenging paddy weeds globally, particularly as agriculture transitions from traditional hand-transplanted rice farming to mechanized direct seeding[1]. Despite their high phenotypic variability, weedy rice often exhibits traits similar to wild rice, such as seed dispersal mechanisms (e.g., seed shattering, awns), seed dormancy, and red-pigmented pericarps. However, unlike wild rice, weedy rice has adapted to agricultural environments, where it aggressively competes with cultivated rice for essential resources, resulting in significant yield reductions[2]. Due to their close genetic affinity and frequent gene flow with cultivated rice, developing herbicides or herbicide-resistant rice varieties to control weedy rice has been particularly challenging. Consequently, weedy rice poses the most formidable weed control issue in rice cultivation, potentially causing up to 90% yield loss in heavily infested fields[3]. The origin of weedy rice has been a subject of extensive historical debate, which includes mainly three origin hypotheses. Early studies proposed that weedy rice emerged through the continuous selection and adaptation of wild rice populations. An alternative hypothesis suggested that weedy rice originated from hybridization events between cultivated rice and its wild progenitor. Additionally, the de-domestication hypothesis proposed that weedy rice might have resulted from the reversion of domesticated rice to a feral form, particularly under conditions where cultivated rice was abandoned or left unmanaged[4]. However, most early hypotheses are based on a subset of weedy rice collections from a specific geographic location. Moreover, in-depth knowledge of the genomic basis for their weediness and rapid adaptation cannot be revealed with limited genomic data. With the accumulation of genomic resources in Oryza species and the comprehensive collection of worldwide weedy rice, our understanding of the origins and evolutionary mechanisms of weedy rice has substantially deepened over the past decade. Here, we revisit the advancements in population genomics that shed light on its de-domestication or feralization origin. We contrast the characteristics of genomic selection signatures associated with rice domestication and feralization. Furthermore, the contributions of multi-way introgressions for its weediness and rapid adaptation are assessed. From the perspective of genetics, we review the current status in the dissection of characteristic traits of weedy rice through QTL mapping and multi-omics approaches. Finally, the strategies for weedy rice control and the potential utilization of its desirable traits are discussed.

-

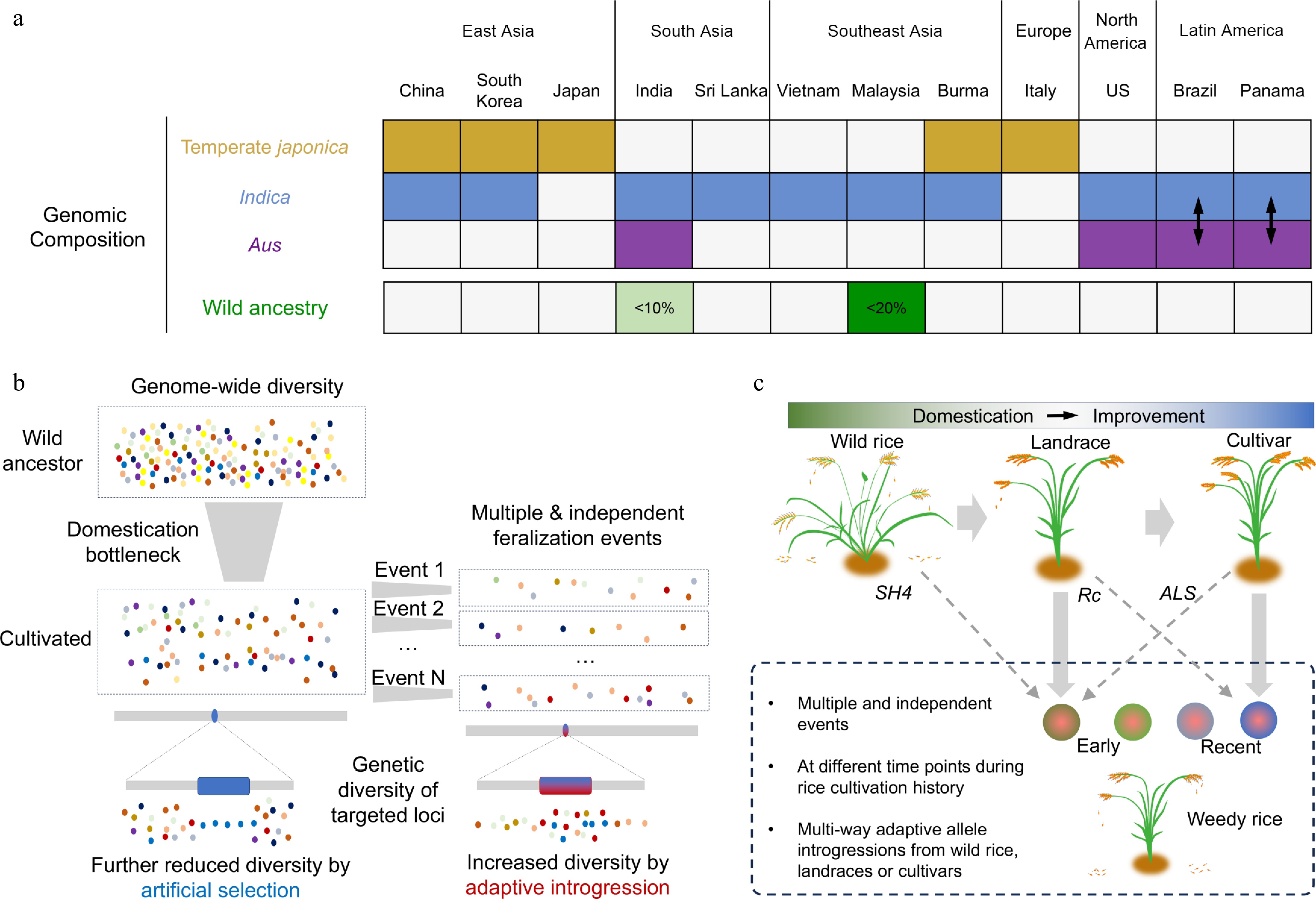

Over the past decade, population genomic studies have reached a consensus that weedy rice around the world has evolved from cultivated ancestors[5−10]. Based on genetic composition, global weedy rice populations are predominantly derived from domesticated rice, exhibiting three primary genetic types: indica, japonica, and aus[9] (Fig. 1a). For instance, in the regions of Southern China, South Asia, and Southeast Asia, weedy rice is predominantly of the indica type, whereas in high-altitude areas such as Northern China and Japan, it is primarily of the japonica type[7,11−13]. In North America, weedy rice is primarily composed of indica and aus types[5,14], whereas indica-aus hybridization origin was observed in South America[9,15]. Geographically, these weeds tend to share a closer phylogenetic relationship with locally cultivated rice at its origin (with the exception of US populations), indicating an in situ origin for most cases[9]. From a temporal scale perspective, their emergence spans a broad spectrum, with some lineages diverging centuries ago and others originating very recently. US weedy rice likely originated from Asian cultivated rice, introduced to North America through human activities several centuries ago[16]. In the high latitudes of Northeast China and North Japan, they may have a semi-domestication origin[8]. Weedy rice in East China is of relatively recent origin, likely derived from the Green Revolution variety 'Nanjing11', abandoned after the 1990s[9,17]. In conclusion, weedy rice across the globe have independently and repeatedly evolved from diverse cultivated ancestors at various historical junctures throughout rice cultivation. This unique origin characteristic provides a crucial foundation for researchers to more effectively investigate the evolutionary mechanisms of rice feralization and to develop effective management strategies.

Figure 1.

Characteristics of genetic origin, selection signatures, and introgression of weedy rice. (a) Summary of the genomic composition of weedy rice populations worldwide. The majority of weedy rice populations are derived from domesticated indica, japonica, and aus genetic backgrounds, represented by blue, brown, and purple colors, respectively. Weedy rice populations exhibiting wild introgressions are indicated in green, while those resulting from admixture between indica and aus are depicted with a bidirectional arrow. The percentage values represent the proportion of wild rice ancestry present in weedy rice genomes. (b) A comparison of changes in genetic diversity for both genome-wide and target genes during the processes of rice domestication and feralization. (c) A schematic illustration highlighting the multiple independent origins of weedy rice and the role of multi-way introgressions in facilitating its adaptations.

-

The evolutionary process of weedy rice feralization leaves distinct genomic signatures of selection compared to those of the domestication process. In crop domestication, the number of domestication events is typically limited. When early cultivated populations were selected from wild species by humans, the populations experienced a strong bottleneck effect, leading to a significant reduction in overall genomic genetic diversity. Furthermore, during the intentional selection of traits by humans, domestication genes controlling the targeted traits are often subject to positive selection, with their allele frequencies becoming fixed, and genetic diversity further reduced[18]. In contrast, the process of feralization involves multiple independent events. In one such event, limited individuals from domesticates can survive and adapt to the complex natural environment, a process also characterized by a strong bottleneck effect (Fig. 1b). Therefore, the genome-wide diversity of weedy rice is typically lower than its counterpart cultivated rice[5,7]. However, unlike the domestication process, crucial genes or genomic regions associated with the feralization process generally exhibit higher averaged genetic diversity relative to the other genomic segments[7] (Fig. 1b), which could largely be attributed to factors such as gene flow and new mutations[9], and maintained by evolutionary driving forces including balancing selection[7]. Moreover, the selection signal intervals during the feralization process of weedy rice have a very low overlap with the domestication intervals of rice. Among the genes in the indica rice domestication interval, only 7.6% overlap with the feralization genomic signals of weedy rice. Similarly, only 2.1% of the genes in the japonica rice domestication interval overlap with signals related to weedy rice feralization[9]. This low overlapping rate indicates that during this process, it is not a simple reversion to the genotype of wild rice, but rather a targeted natural selection that occurs outside the domestication genomic intervals. Notably, Despite the independent and repeated origins for different weedy rice populations, there stands one 0.5-Mb genomic region (6.0 to 6.5 Mb on chromosome 7) potentially under convergent evolution, in which resides both Rc and a cluster of six RAL (seed allergenic protein) genes[7,9,14]. The Rc gene, a well-documented pleiotropic regulator, controls both seed pericarp color and seed dormancy, playing a significant role in the adaptation of weedy rice. It enhances ABA biosynthesis in early seeds to promote dormancy and activates a gene network for flavonoid production in the pericarp[19]. In contrast, the RAL gene cluster has only recently begun to reveal its functional significance. For instance, RAL4 (RAG2) is a major allergen in rice, highly expressed in the developing embryo and endosperm. It is known to regulate grain weight and seed quality in rice. Specifically, overexpression of RAL4 in transgenic rice increases the content of storage proteins and lipids in seeds, thereby improving grain yield[20]. However, the functional implications of the RAL gene cluster for weedy rice remain largely unexplored. This 0.5-Mb region being repeatedly target of selection should be associated with crucial functions during weedy rice feralization and deserves further in-depth investigations.

-

Given that the general genetic makeup of weedy rice is derived from domesticated rice, a critical question arises: how have these domesticated rice-derived weeds acquired their wild-like weedy or adaptive traits (such as herbicide resistance) so rapidly? Recent findings reveal that genetic introgressions from wild rice, ancient landraces, and even modern cultivars into weedy rice are frequent, significantly contributing to their weediness and rapid adaptations (Fig. 1c). In Southeast and South Asia, particularly in Malaysia, Thailand, and India — regions where wild rice coexists with cultivated varieties — the phenomenon of genetic introgression from wild rice is observed, with the proportion of wild rice ancestry typically being less than 20%[10,21,22] (Fig. 1a). Remarkably, such introgression has impacted several genes in chromosome 4 that regulate traits such as seed shattering (sh4), panicle architecture (OsLG1), awn length (An-1 and LABA1), and hull pigmentation (Bh4 and Phr1)[10]. Notably, such genes in weedy rice genomes also share significantly higher similarity with wild rice compared to cultivated rice in another study using syntelog-based pan-genome[23].

The advantageous alleles of cultivated rice can shape both genetic diversity and adaptive evolution in weedy rice[24]. In East China, recently feralized weedy rice has been significantly influenced by landraces[17]. Large genomic blocks from landraces have been introgressed into Nanjing11-derived weeds—approximately 10% of this introgression has been fixed in weedy rice, including genes associated with pericarp color (Rc), and flowering time regulation (Hd3a, RFT1, Ghd7). These genes may enhance the environmental adaptability of weedy rice through adaptive introgression, thus accelerating its feralization process[17]. Furthermore, since the introduction of herbicide-resistant rice cultivars in the 21st century, the genomes of some contemporary weedy rice in the southern United States have evolved through the introgression of the resistance gene ALS from modern herbicide-resistant cultivars[25]; a similar trend has been observed in Argentinian weedy rice[15]. Therefore, the multi-way introgressions from diverse ancestries, particularly involving alleles that confer a selective advantage, greatly contribute to the adaptive evolution of weedy rice populations.

In addition to genetic introgression, new mutations may also play a significant role in the evolution of weedy rice. Genes with highly fixed private variants (potentially new mutations) in weedy rice from East China are functionally enriched in processes related to pollination and reproduction. Notably, the allele frequency of these private SNPs is highly fixed, suggesting that traits related to reproduction have undergone strong natural selection[17].

-

Given weedy rice generally harbors a domesticated genetic composition, Lin et al.[26] proposed that some traits might be explained by standing variation in cultivated rice. They utilized the publicly available phenotypic and genotypic database from the 3000 Rice Genome Project (3K Rice) to conduct a genome-wide association study (GWAS) on five weedy traits: awn color, seed shattering, seed threshability, seed coat color, and seedling height. However, they found that only the seed coat color in weedy rice could be largely attributed to the GWAS signals identified using the 3K rice dataset, highlighting the distinct and complex genetic architecture of weedy traits.

One of the most critical yet mysterious traits of weedy rice is seed shattering. Despite multiple independent origins, the majority of weedy rice populations have inherited non-shattering alleles from their domesticated ancestors[17,27]. For instance, the alleles of all known seed-shattering genes exhibiting natural variation (e.g., sh4, qSH1, and sh3) are of the domesticated type[17]. Recent detailed phenotypic characterization of seed shattering in weedy rice from diverse rice subspecies has revealed that this trait involves multiple developmental mechanisms across independently evolved weedy rice worldwide[28]. Several studies have been undertaken to investigate the genetic basis of seed shattering through bi-parental quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping (Supplementary Table S1). For example, Qi et al.[29] employed traditional QTL mapping methods to study hybrid populations of two types of US weedy rice (BHA and SH) crossed with cultivated indica rice. They generated recombinant inbred lines (RILs) and identified multiple QTLs controlling seed shattering, suggesting that the genetic basis of these traits may involve diverse genetic mechanisms. Similarly, Sun et al.[8] utilized the semi-domesticated weedy rice accession 'WR04-6' and a modern japonica cultivar 'Qishanzhan' to construct an F8 RIL population comprising 168 individuals. They identified a genomic block at the end of chromosome 1 that contributes to various weediness traits, including seed shattering, awn length, and plant height. Furthermore, Li et al.[30] examined a hybrid population of BHA weedy rice and its ancestral cultivated rice (aus subspecies), employing QTL-seq technology to precisely map multiple QTLs related to seed shattering. These QTLs were concentrated in genomic regions selected during the de-domestication process of weedy rice. This study revealed multiple candidate genes associated with seed shattering and underscored the benefits of using closely related parental species to capture evolutionarily relevant QTLs[30]. While several QTLs related to seed shattering have been identified, no candidate genes have yet undergone functional validation. Future investigations should leverage multi-omics data and cutting-edge gene prioritization methods, such as RiceG2G[31], to ascertain candidate genes and conduct further functional validations, including knockout and genetic complementation experiments.

-

Beyond genomics, integrative multi-omics strategies encompassing transcriptomics, metabolomics, and methylomics have emerged as pivotal in recent studies on weedy rice. Cao et al.[32] executed a synergistic analysis of transcriptomics and methylomics, revealing a reduction in DNA methylation levels during rice domestication, with a decrease observed during the feralization process. Notably, there is minimal overlap between hypomethylated sites transitioning from wild to cultivated rice and hypermethylated sites from cultivated to weedy rice. Intriguingly, the methylation status of stress-responsive genes, such as ERF genes, appears to be dynamically altered during both the domestication and feralization phases. Another study indicated that variations in stem strength and lodging resistance in weedy rice are modulated by DNA methylation in genes associated with lignin biosynthesis[33]. The cold tolerance of weedy rice has been linked to the expression levels of CBF genes within the cold response pathway, as well as to methylation levels, particularly at CHG and CHH sites, in the promoter region of OsICE1[34].

Comparative multi-omic analyses, including transcriptomics, metabolomics, and proteomics, have been conducted to elucidate differences during seed germination between weedy and cultivated rice[35,36]. Weedy rice has been found to accumulate substantial quantities of flavonoids, amino acids, and their derivatives, which significantly enhance its antioxidant capacity and resource utilization efficiency, thereby conferring a heightened competitive edge under resource-limited conditions. Moreover, weedy rice demonstrates an efficient energy metabolism profile under stress, attributed primarily to the robust activity of oxidative phosphorylation and carbohydrate metabolism pathways[35,36].

While multi-omics approaches offer novel genetic perspectives into the adaptive mechanisms of weedy rice, the integration of multi-omics data remains a complex and challenging task. One of the primary challenges is the lack of standardized methods for integrating omics datasets in weedy rice, which can lead to inconsistencies and difficulties in comparing and validating findings across studies. In addition, future research should exercise caution regarding the ancestry of the weedy rice populations under investigation, given their multiple independent origins. Better clarity regarding genetic ancestry, or even the specific cultivated progenitors, could facilitate more accurate identification of the dynamic changes across various omics levels during the feralization of weedy rice. Developing standardized protocols for multi-omics data integration, exploring advanced integration methods, and developing a more flexible and comprehensive database platform are essential for advancing multi-omics research in weedy rice.

-

Effective control and management of weedy rice require an integrated approach that combines preventive measures, cultivation management techniques, chemical applications, and biotechnological strategies, rather than relying on a single method[37] (Fig. 2). In terms of prevention, the most crucial action to mitigate weedy rice infestations is the use of clean rice seeds. A commonly employed cultivation management practice is the stale seedbed technique, which entails irrigating the field and leaving it unsown for about two weeks. This practice allows weedy rice to germinate, after which the emerged seedlings can be controlled using herbicides or tillage before rice planting[38]. Furthermore, deep tillage and crop rotation can also help reduce the emergence of weedy rice[39]. In rotated fields, weedy rice tends to be more apparent, facilitating easy identification and removal or treatment with herbicides.

Regarding chemical control, considering the genetic and physiological similarities between weedy rice and cultivated rice, it is vital to determine the optimal timing for herbicide application. For example, non-selective herbicides, such as glyphosate, can be applied only before sowing rice, often in conjunction with the stale seedbed method. Some selective herbicides, such as benzobicyclon, have shown effectiveness against certain indica-type weedy rice where temperate japonica is cultivated[40].

The adoption of herbicide-resistant rice varieties represents another strategy for selectively managing weedy rice within cultivated rice systems. There are three types of herbicide-resistant rice, including those tolerant to imidazolinone, glyphosate, and glufosinate. Notably, imidazolinone-resistant rice is non-transgenic, having arisen through natural mutations. Clearfield rice and Jietian varieties are two types of imidazolinone-resistant rice that are commercially applied, which carries the Ser627Asn and Trp548Met mutation in ALS gene, respectively. It is documented that Jietian varieties with Trp548Met mutation confer several advantages over Ser627Asn rice, including resistance to more families of ALS-inhibiting herbicides, and provide safety for hybrid rice as the heterozygous allele provides sufficient herbicide resistance[41].

Beyond traditional breeding and transgenic methods, CRISPR-based gene editing has revolutionized the development of herbicide-resistant rice by offering unprecedented precision and efficiency. CRISPR/Cas9, for example, has been effectively employed to introduce specific mutations in key genes: in the EPSPS gene (such as Thr102Ile and Pro106Ser) to confer resistance to glyphosate[42], and in the ALS gene (such as Trp574Leu) to enhance resistance to ALS-inhibiting herbicides[43]. These edited rice lines not only demonstrate robust herbicide tolerance but also bypass the regulatory hurdles and public acceptance issues often associated with transgenic crops. Additionally, advanced base-editing technologies like cytosine base editors (CBEs) and adenine base editors (ABEs) allow for precise single-nucleotide modifications (for instance, Met268Thr in the α-tubulin gene for dinitroaniline resistance) without incorporating foreign DNA, thereby broadening the scope for non-transgenic herbicide-resistant rice development[44,45]. By harnessing these CRISPR-based techniques, researchers can efficiently generate and stack multiple herbicide-resistant alleles into elite rice varieties, offering a sustainable strategy to counter the evolving threat of herbicide-resistant weedy rice.

However, it is crucial to monitor the potential for gene flow to ensure the sustainability of this solution. If herbicide resistance genes transfer to weedy rice populations, these populations may develop increased resistance[46], potentially posing a greater agri-ecological risk than transgenic varieties[47]. Establishing guidelines for the responsible use of herbicide-resistant rice cultivars is of utmost importance. Future weedy rice management could benefit from genomics-assisted approaches, focusing on clarification of the weedy rice genetic composition, as well as detecting potential gene flow from herbicide-resistant rice and de novo mutations conferring herbicide-resistant alleles (Fig. 2).

-

The greatest virtue of a weed is its ability to adapt[48], and weedy rice is a hidden gold genetic mine in the paddy field[49]. Weedy rice, with its superior traits and excellent adaptability under various abiotic stresses such as drought, cold, and flooding tolerance, and biotic stresses like rice blast and sheath blight disease (Supplementary Table S1)[50]. In addition, weedy rice has a high tillering ability and a developed root system, which enhances nitrogen absorption and nutrient use efficiency. It performs well in nutrient-limited soils, and its nutrient uptake and biomass accumulation under limited nitrogen conditions are significantly higher than that of cultivated rice[50,51]. Moreover, weedy rice seeds harbor much greater quantities of anthocyanin, beneficial trace elements, and unsaturated fatty acids than cultivated rice[52]. While weedy rice possesses various genetic resources that could be utilized for rice improvement, currently, limited functional genes have been cloned from weedy rice (Supplementary Table S1). Han et al.[53] integrated multi-omics approaches like GWAS, transcriptomic and parallel reaction monitoring analyses, as well as functional experiments, and identified PAPH1 gene in weedy rice plays an important role in conferring strong drought resistance. Sun et al.[54] has found and validated that the OsGF14h gene in weedy rice could balance ABA signaling and GA biosynthesis during anaerobic germination, this gene can significantly boost the germination rate of rice seeds under anaerobic conditions, from 13.5% to 60.5%[54]. The superior allele of OsGF14h has been lost during modern japonica improvement, and therefore could serve as a genetic resource to improve flood adaptation in elite rice. Using weedy rice for trait improvement offers several advantages. Its ease of hybridization is a significant benefit, as there are no concerns regarding hybrid sterility compared to using wild rice. Furthermore, local weedy rice has adapted well to the regional environment, making it a valuable genetic resource for enhancing the qualities of locally cultivated rice.

-

The extensive research on the genomics of weedy rice over the past decade has significantly advanced our understanding of its origins and evolution. In the near future, the genomic mechanism for its rapid adaptation and functional genes responsible for their special traits are imperative to be undermined. Weed rice generally has a selfing reproductive system, and experiences strong bottleneck effects during the process of feralization. Populations of specific origins have extremely low effective population sizes. Therefore, the strong environmental adaptability and competitiveness of weed rice seem to contradict its extremely low genetic diversity, presenting a 'genetic paradox of biological invasion'[55]. The activity of transposon elements (TEs) may concentrate variations in functional gene regions, creating local high-variation hotspots and thereby bypassing the limitation of global low diversity. Therefore, it would be promising to dive into the contribution of TEs for their rapid adaptation. The potential effects of TE insertions on the expression and epigenetic modifications of key environmental adaptability genes in rice, such as those controlling flowering time and herbicide resistance are to be explored. In addition, in contrast to the 'domestication cost', how the genetic load could be changed during feralization and the contributions by TEs remains to be investigated. Meanwhile, for underpinning the genetic basis for the feralized traits of weedy rice (Supplementary Table S1), given that weedy rice has evolved through multiple independent origins, it is crucial to select an appropriate genetic background when investigating its specific phenotypic characteristics. For instance, when constructing genetic mapping populations, it is advisable to identify the potential direct ancestor materials based on genomic relationships. Utilizing these ancestral materials, along with the derived weedy rice populations, can facilitate the identification of functionally causal genes leading to the feralization process.

For weedy rice control and management, developing herbicide-resistant rice has been proven as an effective approach. However, given that weedy rice is a conspecific weed of cultivated rice, gene flow between them is inevitable in the field, which enables weedy rice to acquire herbicide-resistance genes. To address this challenge, the strategy of transgene mitigation (TM) has been proposed as a solution[56,57]. The core principle of TM is to insert a tandem secondary mitigator that is tightly linked to the herbicide resistance gene, thereby forming a 'safety box' for the development of herbicide-resistant (HR) rice (Fig. 2). These TM genes confer traits that are either beneficial or neutral to the crop but significantly reduce the fitness of crop-weed hybrids and their descendants. For weedy rice, potential TM genes could include those leading to seed non-shattering or non-dormancy phenotypes. Therefore, elucidating the genetic mechanisms underlying the weediness or adaptive traits of weedy rice is crucial for the efficient design of the 'safety box'. Additionally, genes that are under highly convergent evolution of diverse populations may represent more practical and optimal targets. In addition to genetic-based approaches, the development of artificial intelligence powered drones or robots for the identification and precise removal of weedy rice using herbicides during the seedling stage also holds promise[58,59].

Crop domestication often results in a reduction of genetic diversity, which poses a threat to the resilience of agroecosystems. In recent years, de novo domestication — a form of neodomestication achieved through genome editing of domestication-related genes or alleles — has been proposed as a means to accelerate domestication in rice wild relatives[60]. Similarly, spontaneously evolved weedy rice also holds the potential for re-domestication[61] and offers valuable traits for developing resilient crops adapted to sustainable agricultural systems, particularly in addressing climate change and escalating environmental pressures. For example, due to naturally evolved traits favoring direct-seeding cultivation, the Rc gene has been targeted as a priority for re-domestication to eliminate undesirable traits in rice adapted to such practices[62]. Given their close genetic relationship with cultivated rice, de novo re-domestication efforts can leverage accumulated rice genetic knowledge and existing transformation and genome editing systems. By employing strategies like RiceNavi[63] and advanced genomic editing technologies, unfavorable feralized alleles in weedy rice can be efficiently replaced or modified to facilitate re-domestication.

Globally, extensive research of different groups has been conducted on the phenotypic and physiological ecological traits of weedy rice, including herbicide resistance and various omics studies. However, the findings from each weedy population may clarify the mechanisms for only a branch of weedy rice. Therefore, the genetic mechanisms underlying the traits of weedy rice studied in one region may not be applicable to other populations with different origins. Therefore, it is essential to establish a shared information resource and genomics platform. Increased collaboration among geneticists, agronomists, and weed scientists is encouraged. Together, they can accelerate and share research on weedy rice, thereby enhancing the utilization of genetic resources and promoting effective management strategies.

This work was funded by Shanghai Science and Technology Committee Rising Star Program (22QA1406800 to JQ) and the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2022J01471 to YG).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Qiu J; draft manuscript preparation: Cong Y, Qiu J, Liu J, Gui Y, Yong K, Zhu M, Liu K. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed in this review.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Yunqi Cong, Yijie Gui

- Supplementary Table S1 Summary of QTL mappings of keys traits for weedy rice.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Cong Y, Gui Y, Yong K, Zhu M, Liu K, et al. 2025. Deciphering rice feralization: insights from genomics of weedy rice. Genomics Communications 2: e007 doi: 10.48130/gcomm-0025-0007

Deciphering rice feralization: insights from genomics of weedy rice

- Received: 31 December 2024

- Revised: 04 March 2025

- Accepted: 19 March 2025

- Published online: 14 April 2025

Abstract: Weedy rice (Oryza spp.) threatens global rice production due to its high seed shattering, persistent soil seed dormancy, and strong competitiveness against cultivated varieties. Population genomic studies over the past decade have revealed that weedy rice primarily originated from domesticated rice through de-domestication or feralization, establishing it as a key model for studying the genomic basis of crop feralization. Beyond elucidating their unique evolutionary origins, critical challenges and research gaps persist, particularly concerning the genetic underpinnings of their weediness and adaptive traits. Additionally, there is a need to effectively translate genomic insights into practical field management strategies and to fully leverage the potential of the genetic resource pool. This mini-review synthesizes recent advances in understanding its evolutionary trajectories, adaptation-related genomic signatures, multi-way introgression dynamics, and genetic mapping of weedy traits. We further discuss current control strategies alongside the underutilized potential of weedy rice as a genetic resource. Enhanced collaboration among geneticists, agronomists, and weed scientists will be vital for developing sustainable solutions while harnessing adaptive traits from weedy rice for rice improvement.

-

Key words:

- Weedy rice /

- Feralization /

- Genetic introgression /

- Weed management