-

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have become integral to modern technology, powering everything from portable electronics to electric vehicles, due to their high energy density and long cycle life[1]. However, the safety of LIBs remains a significant concern, particularly in the event of thermal runaway (TR), which can lead to hazardous outcomes such as fires and explosions[2]. TR is typically triggered by factors such as internal short circuits, overcharging, or excessive external temperatures[3]. Once initiated, it can result in a rapid increase in temperature and the release of flammable gases, presenting serious risks to both the battery and its surroundings. As such, mitigating TR is crucial to improving the safety of LIBs in extreme conditions[4].

Research on TR in LIBs has made significant strides, focusing on understanding its triggers, advancing thermal management, and developing safety-enhancing materials[5,6]. TR, a self-sustaining exothermic reaction, typically results from factors like internal short circuits, overcharging, or external heating, each causing rapid temperature escalation that can lead to catastrophic failure[7]. Researchers have utilized tools to study the thermal stability of battery components and pinpoint specific reactions that accelerate TR. In response, researchers have focused on the thermal runaway law of the battery under different environments and conditions[8,9], and flame-retardant electrolytes with additives like phosphates to reduce flammability[10,11]. Additionally, safer cathode materials, such as lithium iron phosphate, have been investigated for their ability to remain stable under high temperatures, lowering the probability of TR onset. Together, these advancements in materials strategies contribute to reducing the likelihood of TR and enhancing the safety of LIBs in practical applications. As the demand for LIBs continues to grow in industries such as electric vehicles, consumer electronics, and renewable energy storage, ongoing research into these materials and their integration into battery design will be critical in ensuring that the next generation of batteries remains both high-performing and safe under a wide range of operational conditions[12]. In the realm of active TR suppression, researchers have employed methods such as liquid nitrogen, aerogel extinguishing agents, perfluorohexane, and fine water mist, all achieving favorable outcomes[13,14]. In recent years, researchers have focused on enhancing the thermal safety of LIBs by developing various thermal management materials to prevent or delay TR, including high thermal conductivity composites with metal or ceramic fillers, which disperse heat more effectively. These materials are designed to isolate external heat sources and absorb excess internal heat, thereby improving the thermal stability of the battery[15]. Chavan et al. reviewed a variety of thermal models and cooling techniques, such as air, liquid, phase change materials (PCMs), and hybrid cooling systems, which offer promising solutions for mitigating thermal issues, enhancing battery performance, and extending the lifespan of LIBs in EVs[16]. Wu et al. concluded that liquid cold plate (LCP) cooling technology, as a key component of battery thermal management systems (BTMS), offered effective solutions for maintaining the performance, safety, and longevity of LIBs in electric vehicles, but highlighted the need for a multi-objective optimization approach that considered safety, cost, efficiency, and system simplification to further enhance its cooling capacity and overall system performance[17]. Nasiri & Hadim concluded that while various BTMS, including air, liquid, and phase change material cooling methods, have been explored to address the temperature limitations of LIBs in electric vehicles and stationary energy storage, significant challenges remain, highlighting the need for continued research to improve their performance, safety, and overall efficiency[18]. Among the materials studied, PCMs have shown promise in delaying TR onset and mitigating heat accumulation within the battery[19−21]. Chen et al. argued that integrating suppression strategies into existing thermal management approaches was optimal, such as employing PCMs in thermal management systems[22]. Chen et al. found through comparative analysis that different materials and thermal management methods exhibit varied effects on TR and its propagation, indicating ample room for exploration of novel suppression materials and techniques[23]. PCMs provide a dynamic temperature regulation mechanism by absorbing and releasing heat during battery overheating, effectively preventing further temperature escalation. Huang et al. designed a novel flame-retardant flexible composite PCM, which had shown promising results in mitigating TR in LIBs[11]. Recent research has focused on optimizing the integration of PCMs into battery designs to enhance their cooling capabilities. Various types of PCMs, such as organic, inorganic, and eutectic blends, have been evaluated for their thermal performance. However, there are several challenges in the widespread application of PCMs in battery thermal management.

While the BTMS plays a crucial role in controlling the temperature and preventing the initial onset of TR, its ability to halt or slow down the propagation of TR remains limited. The BTMS can delay the occurrence of TR by maintaining the battery temperature within a safe range, but once TR initiates, the system struggles to prevent it from spreading to adjacent cells. As a result, additional strategies are required to address the propagation of TR in high-risk scenarios. Zhang et al. concluded that a novel hybrid TR propagation mitigation system, combining low and high thermal conductivity PCM, heat pipes, and air-cooling, successfully reduced the risk of TR propagation in LIB packs for electric vehicles[24]. The aerogels, due to their lightweight and efficient insulation properties, are regarded as potential enhancements to battery thermal management systems. Tang et al. discovered that silica aerogel sheets can effectively inhibit the propagation of TR when arranged in three layers[25]. Yang et al. found that the addition of aerogel insulation materials can delay the spread of TR, although they may not completely sever the propagation process; however, the combined use of aerogels and liquid cooling plates can prevent the transmission of TR[26]. Wong et al. concluded that nanofiber aerogel effectively inhibited TR propagation within high-energy-density LIB modules, with the thickness of the aerogel significantly extending the time interval between propagation events and reducing the peak temperature difference, providing valuable insights for designing safer battery systems[27]. Yang et al. studied and evaluated the performance of heat exchangers with three different configurations (liquid cooling, insulation materials, and PCMs), and proposed their respective applicable ranges[28]. Dai et al. concluded that encapsulated inorganic phase change material enhanced with carbon nanotubes effectively improved both battery thermal management and TR mitigation, demonstrating a significant reduction in peak battery temperature and a delay in the propagation of TR[29]. Chen et al. found that a 2 mm glass-fiber reinforced flame retardant polypropylene thermal barrier effectively prevented TR propagation in LIBs by providing thermal insulation, significantly delaying the propagation time and suppressing both radiation and convection heat transfer mechanisms[30]. Chen et al. found that the developed multifunctional fire shield, composed of hydrogel, aluminum hydroxide, ceramic fiber, and ammonium bicarbonate, effectively suppressed thermal propagation and diluted combustible gases during TR in large-capacity lithium iron phosphate batteries, offering significant improvements in heat conduction, thermal insulation, and gas regulation for enhanced battery safety[31]. Shen et al. demonstrated that the novel sandwich-type fire-resistant flexible composite PCM (PEE@EBF) effectively mitigated overheating and TR in LIBs by reducing peak heat release, peak smoke production, and battery temperatures, while delaying TR by 633 s, making it an ideal solution for thermal management and fire protection in energy storage systems[32]. The existing literature on the comparative performance of these materials is limited, particularly regarding their effectiveness under real-world conditions and their long-term stability in commercial applications[33]. At the same time, the comprehensive performance and long-term stability of these materials in practical battery systems remain insufficiently studied. Additionally, the effects and adaptability of certain materials concerning TR warrant further research and validation.

Therefore, this study's novelty lies in establishing the systematic cross-comparison of four distinct material classes under identical abuse conditions, directly quantifying their efficiency in suppressing LIB TR through experimental validation. By utilizing these materials, the research aspires to offer a holistic framework for assessing and optimizing battery thermal management systems, thereby enhancing their safety and reliability under extreme conditions.

-

In this experiment, the tested battery was the Panasonic NCR 21700T LIB, with a cathode material represented as NCA (Nickel-Cobalt-Aluminum). The specific parameters of the battery are detailed in Table 1. Before the experiment, the battery was charged to 100% state of charge (SOC), corresponding to a charge capacity of 4,800 mAh, using a charge-discharge cycling instrument from Shenzhen Neware Electronics Co., Ltd., China. The battery was then left to rest for 24 h before conducting the TR experiment. The purpose of this resting period was to balance the internal charge distribution within the battery and minimize its self-discharge rate, thereby ensuring greater accuracy and reliability in the experimental results.

Table 1. Composition of 21700T lithium-ion battery.

Parameter Value Battery Panasonic NCR 21700T Capacity 4,800 mAh Voltage 3.7 V (discharge cut-off voltage 3.0 V, maximum charge voltage 4.2 V) Dimensions Φ 18 × 65 mm Anode Graphite Cathode NCA Electrolyte Solvents, salts, and additives In this experiment, four types of wrapping materials were selected to study their effects on the TR characteristics of LIBs. The materials included aerogel blankets, thermal conductive gel, and two types of PCM. The nano-silica aerogel blanket, with a thickness of 3 mm and a thermal conductivity of 0.021 W/m·K at room temperature, was purchased from Langfang Shengmai Insulation Materials Co., Ltd., Hebei (China). The thermal conductive gel was sourced from Guangzhou Boqiao Electronic Materials Co., Ltd (Guangzhou, China). It was produced by physically mixing two components, HY-8018/A and HY-8018/B, in a 5:1 ratio, resulting in a thermal conductivity of 1.0–1.1 W/m·K. The PCMs were prepared in the laboratory, with the specific composition ratios detailed in Table 2. PCM-1 has a thermal conductivity of 1.9 W/m·K, while PCM-2 has a thermal conductivity of 2 W/m·K. Paraffin wax was purchased from Cangzhou Haoyu New Energy Technology Co., Ltd., China, while expanded graphite with a purity of 99% was sourced from Qingdao Tengshengda Carbon and Graphite Co., Ltd., China. Single-layer graphene, with a specific surface area of 50–200 m²/g, was obtained from Shenzhen Suiheng Technology Co., Ltd (Shenzhen, China). Due to the inherently poor flame retardancy of phase change materials, DOPO, a novel flame retardant intermediate, was incorporated to enhance the fire resistance of the phase change materials. Graphene was used to improve the thermal conductivity of the phase change materials. The aerogel blanket, thermal conductive gel, PCM-1, and PCM-2 were all tightly wrapped around the battery, each with a thickness of 3 mm.

Table 2. Mass content of the components in the obtained CPCMs.

Sample Mass content (wt%) PA EG Graphene DOPO PCM-1 93 7 0 0 PCM-2 85 5 8 2 Experimental setup

-

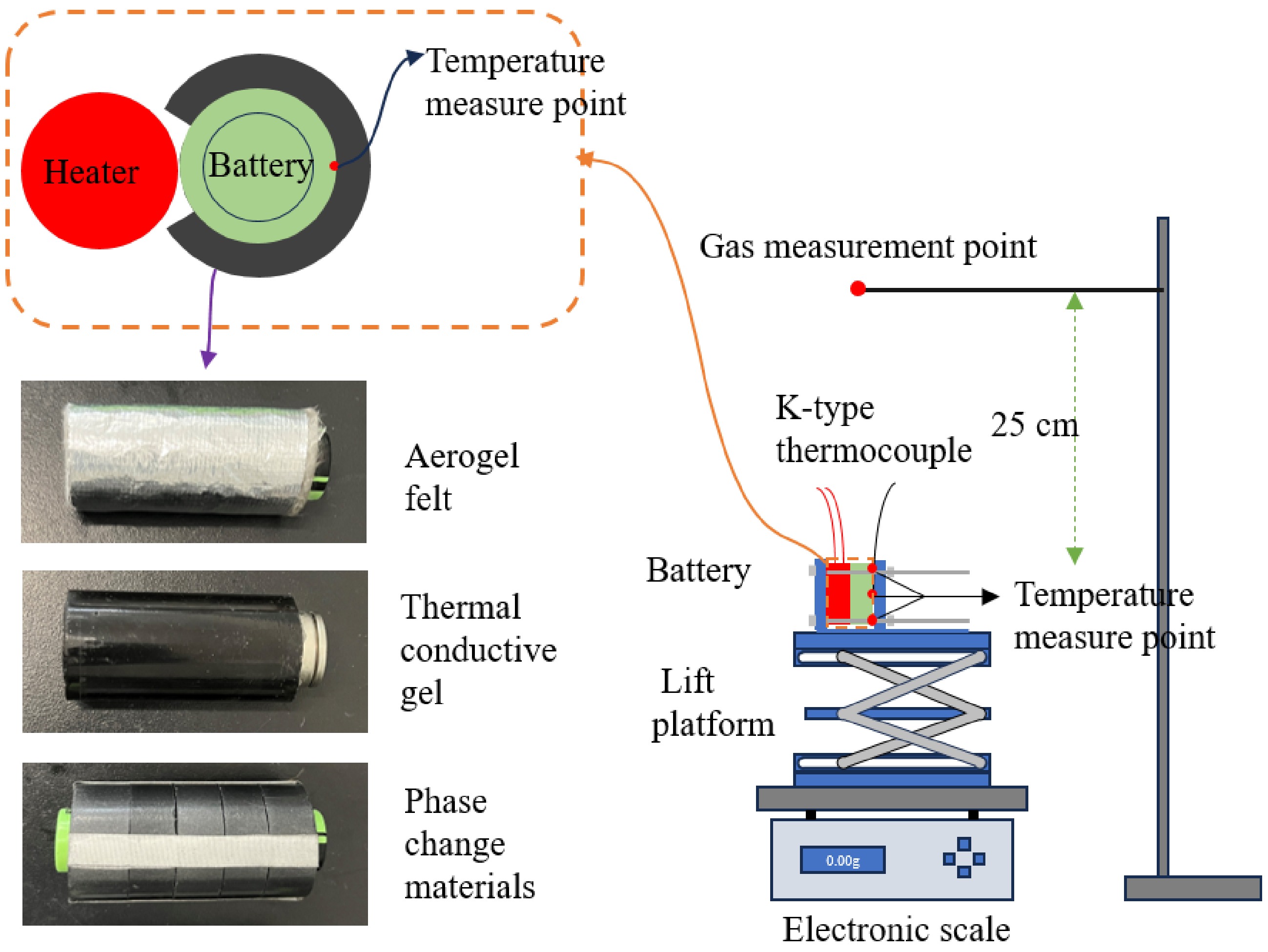

Figure 1 illustrates the schematic diagram of the overall setup for the TR suppression experiment. The apparatus primarily consists of a battery module, a lift platform, an electronic scale, a flue gas analyzer, and a temperature recording module. The entire setup is housed within an experimental chamber measuring 2.5 m × 2 m × 2 m (length × width × height).

The battery module is constructed from stainless steel metal plates, heating rods, and the battery itself. The plates are employed to secure the heating rods and the battery, preventing any displacement of the battery from the lift platform during TR. In this study, the heating rods operate at a power of 300 W and are positioned closely adjacent to the battery to induce the overheating conditions required for TR. Once TR is initiated, the heating rods are deactivated to prevent further external heat input. While this method effectively simulates TR initiation, it is important to consider that the TR behavior of the battery could be affected by factors such as the heating rate, the duration of heating, and the heat distribution, all of which may vary depending on the experimental setup. To address these potential influences, further studies could explore different heating methods, including distributed heat sources, to better replicate actual TR scenarios in practical applications.

Temperature measurement points are located on the battery's side surface at three levels: upper, middle, and lower. These measurements are recorded using K-type thermocouples. The thermocouples are connected to the temperature recording module, which transmits the data to a computer for temperature data logging. The K-type thermocouples have a temperature measurement range of 0–1,300 °C, which adequately meets the maximum temperature requirements during TR.

The flue gas measurement point is positioned 25 cm above the battery to capture the gases generated during TR while minimizing interference from the immediate vicinity of the battery surface. This height allows for a more accurate representation of the gas dispersion in the surrounding environment. The Testo 330 gas analyzer, manufactured in Germany, was employed to simultaneously measure the variations in CO concentration and flue gas temperature. This setup ensures a comprehensive analysis of the TR process by evaluating both the heat and gas emissions at a safe distance from the battery. Below the battery module, the lift platform and electronic scale are positioned. The lift platform protects the electronic scale from thermal hazards associated with the battery during TR, while the electronic scale is utilized to record changes in the battery's mass throughout the TR process.

-

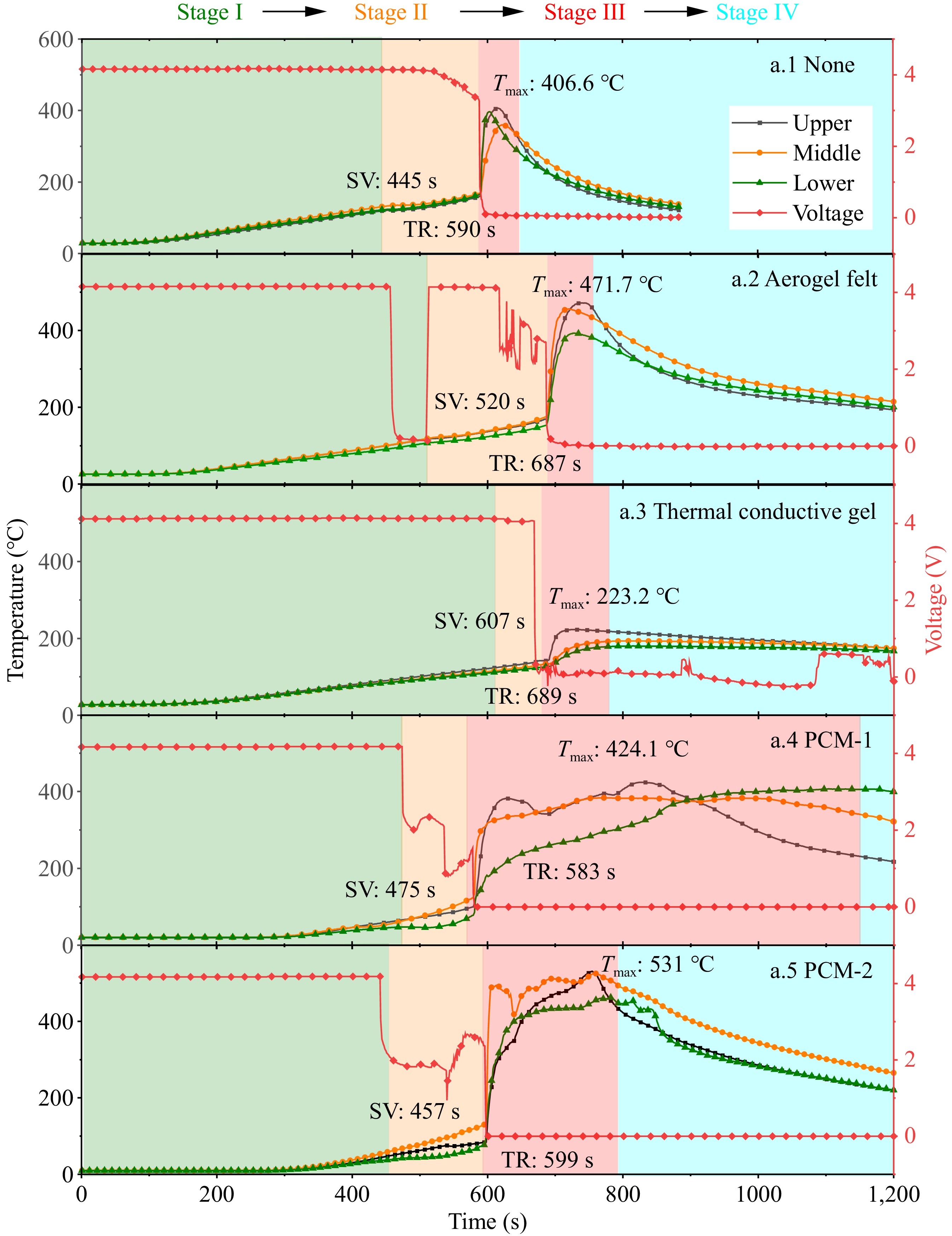

The variations in temperature and voltage during battery TR are two critically important parameters. In this experiment, the intermediate temperature on the side surface of the 21,700 battery were measured, and the voltage changes across the battery's terminals were examined. The temperature and voltage change curves are depicted in Fig. 2. The TR in this experiment can be categorized into four distinct stages.

Stage I represents the temperature rise phase before the safety valve ruptures. During this stage, the battery's temperature gradually increases, while the voltage remains stable in the early part of this phase. For batteries wrapped in aerogel, PCM-1, and PCM-2, a sharp decline in voltage is observed in the latter part of Stage I. This is attributed to the heating of the battery, where the internal separator remains intact at lower temperatures, preventing internal short circuits and resulting in no voltage change. When the temperature approaches approximately 100 °C, the internal separator is compromised, leading to a sudden drop in voltage.

Stage II corresponds to the gas release phase following the rupture of the safety valve. In the early part of this stage, the battery voltage increases before declining again, ultimately dropping to 0 V as TR occurs in Stage III. This increase is due to the release of internal pressure and electrolyte when the safety valve opens. The release of electrolyte results in some lithium salt being expelled, causing a decrease in the concentration of lithium salt within the electrolyte. Concurrently, because the boiling point of organic solvents is higher than that of water, some electrolyte evaporates, leading to an increase in the concentration of organic solvents. The increased presence of organic solvents can enhance the battery's conductivity, thus increasing the output current. As the output current rises, the rate of internal chemical reactions accelerates, temporarily restoring the battery's voltage to a certain degree.

Stage III marks the TR phase of the battery. At the onset of this stage, the battery experiences TR, causing the voltage to plummet to 0 V. TR is defined in this study as a sustained temperature rise rate of 1 °C/s or greater. During this phase, the battery temperature escalates dramatically, accompanied by the ejection of sparks and gases, and the release of substantial heat.

Stage IV represents the cooling phase, during which the temperatures at the upper, middle, and lower sections of the battery begin to decline after reaching their peak. Throughout this phase, the battery voltage remains constant at 0 V.

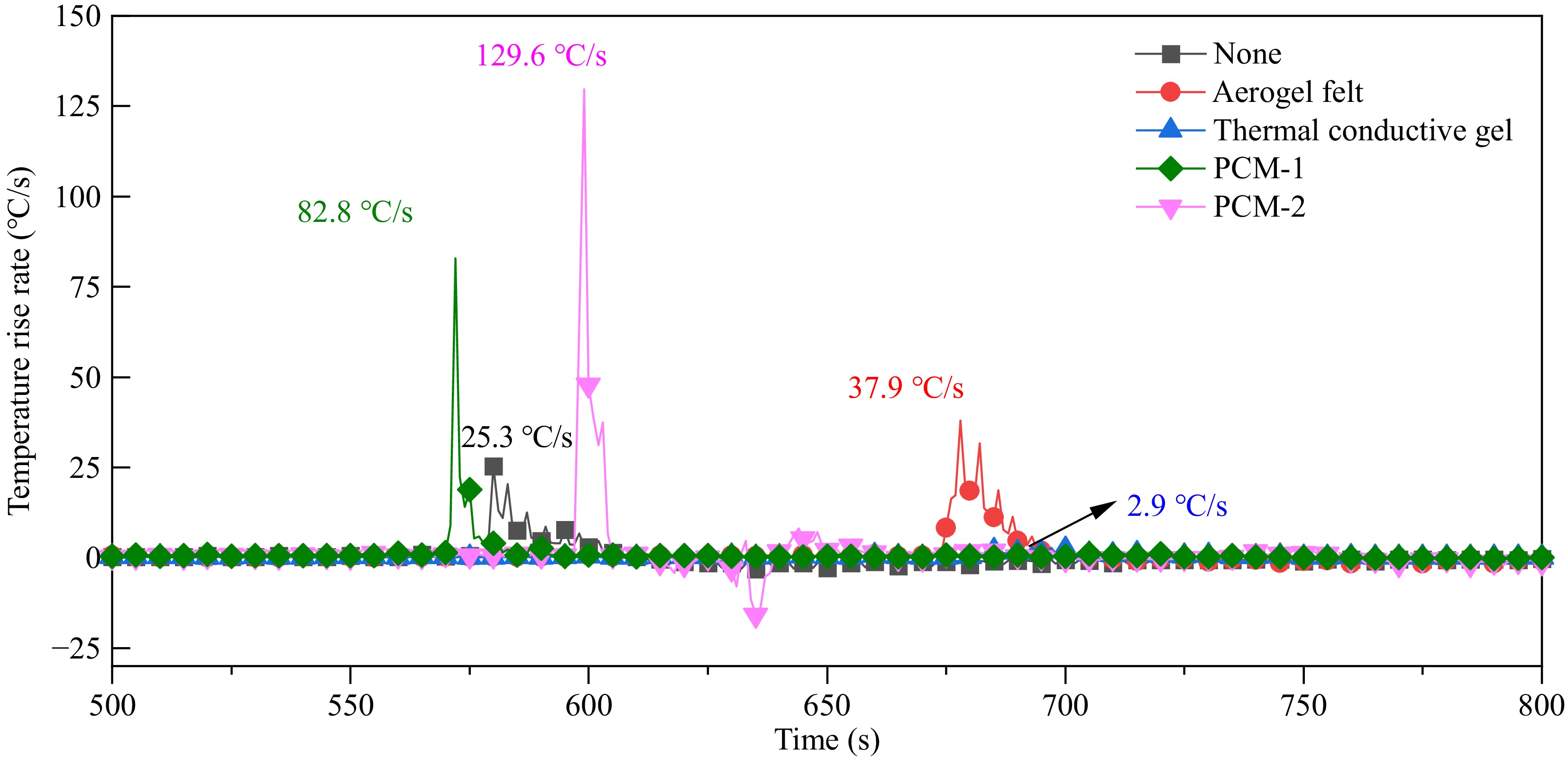

Additionally, as illustrated in the Fig. 2, except for the battery wrapped in thermal conductive gel, all other batteries exhibited an increase in maximum TR temperature. As shown in Fig. 3, the maximum temperature rise rate during TR exhibits significant variations under different wrapping materials. Experimental data reveals that Aerogel felt, PCM1, and PCM2 demonstrate maximum temperature rise rates of 37.9, 82.8, and 129.6 °C/s respectively. Compared to the control group without wrapping material (25.3 °C/s), these values represent increases of 49.8%, 227.3%, and 412.3% respectively. In striking contrast, the thermal conductive gel shows superior thermal suppression performance with a maximum temperature rise rate of only 2.9 °C/s, corresponding to an 88.5% reduction compared to the control group. This phenomenon is attributable to the extended heating duration of the battery itself; although the initiation of TR is delayed, the temperature escalates rapidly during the event, releasing considerable heat. The materials themselves accumulate significant thermal energy, which cannot be efficiently dissipated to the surroundings, resulting in further heat accumulation and elevated battery temperatures. Conversely, the battery wrapped in thermal conductive gel experiences more extensive ejection of multi-layer separators and electrolytes into the external environment during TR, thereby reducing the internal heat sources and resulting in a lower maximum temperature. Furthermore, the opening of the safety valve causes high-temperature electrolyte to be ejected upward, leading to the lowest temperatures at the bottom of the battery during the TR process.

The times for safety valve rupture (SV) and the onset of TR are summarized in Table 3. It is evident that, compared to the unwrapped battery, the batteries wrapped in aerogel blankets, thermal conductive gel, and phase change materials experienced delays in both safety valve rupture time and TR onset time. Specifically, the onset of TR was delayed by 97 s for the aerogel-wrapped battery, 99 s for the thermal conductive gel-wrapped battery, and 9 s for the PCM-2-wrapped battery. Although the safety valve rupture time for the PCM-1 was also delayed, its TR onset time was comparable to that of the unwrapped battery.

Table 3. Starting time of safety valve rupture and thermal runaway.

Protective material Safety valve

rupture time (s)Thermal runaway

occurs time (s)None 445 590 Aerogel felt 520 687 Thermal conductive gel 607 689 PCM-1 475 583 PCM-2 457 599 Before the occurrence of TR, the insulating and heat-absorbing properties of the wrapping materials positively influenced the triggering of TR in LIBs, effectively suppressing its occurrence. Among the materials, the thermal conductive gel exhibited the most significant impact on both safety valve rupture and the onset of TR, while the phase change materials provided only a slight reduction in the corresponding times.

Flue gas characteristics

-

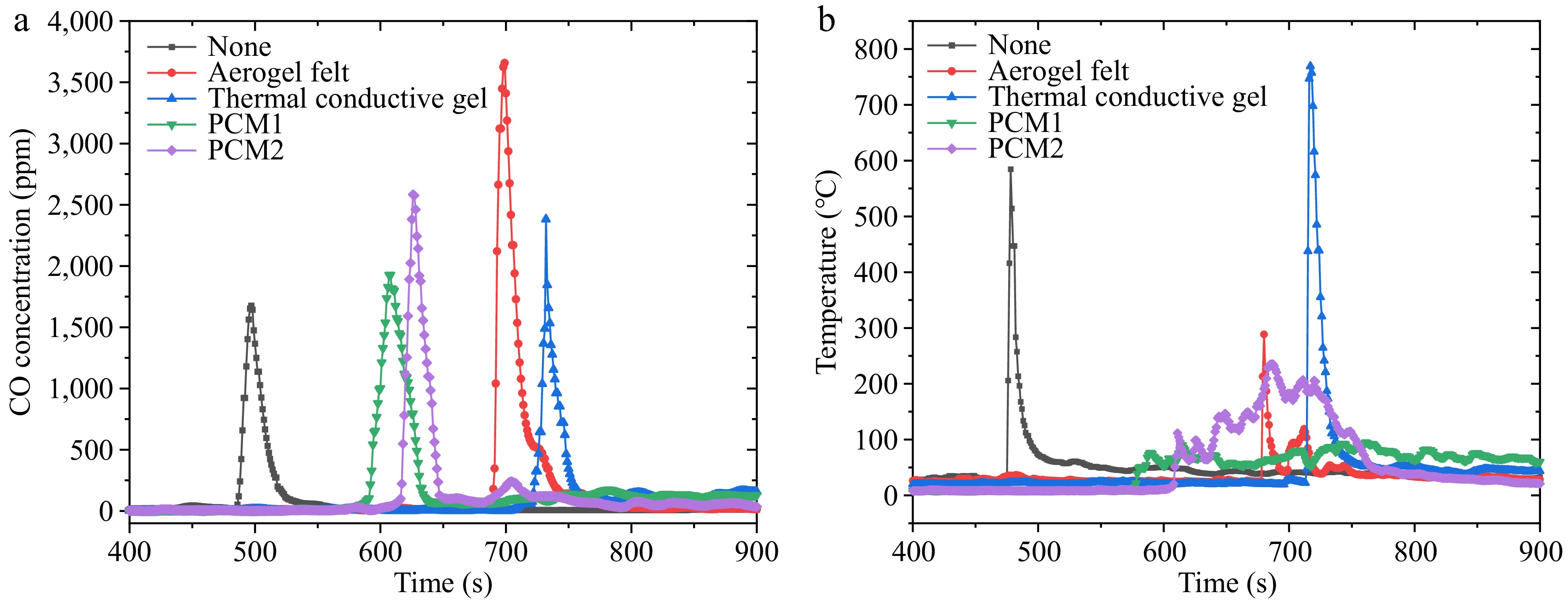

During TR following the rupture of the safety valve, LIBs release a significant amount of flue gas, often accompanied by the ejection of sparks. Figure 4 illustrates the changes in CO concentration, flue gas temperature, and ambient temperature at a distance of 25 cm above the 21,700 battery. Compared to unwrapped batteries, those wrapped in materials exhibited higher CO concentrations, with a maximum concentration of 3,658 ppm recorded for the aerogel-wrapped battery. The wrapped battery exhibits higher CO concentration during TR, indicating that the wrapping material delays the onset of TR and may also change the nature of the TR. This property is related to combustion efficiency. A higher CO concentration may indicate a decrease in combustion efficiency.

Before TR occurs, various wrapping materials can mitigate some of the heat transfer from the heating rod while facilitating a more rapid dissipation of internal heat to the environment. This results in a more stable release of flue gas, reducing the risk of excessive ejection of electrolytes and sparks due to heat accumulation, thereby lowering CO concentration. In comparison to the unwrapped battery, CO concentrations for the aerogel and thermal conductive gel-wrapped batteries increased by 118.3% and 42.1%, respectively. Conversely, batteries wrapped in PCM-1 and PCM-2 generated higher CO concentrations during TR, potentially due to incomplete combustion of the phase change materials, resulting in the production of additional CO.

The thermal conductive gel demonstrated the lowest CO concentration increase and the highest flue gas temperature. This can be attributed to its high thermal conductivity, which facilitates rapid heat dissipation from localized hot spots. By homogenizing the temperature distribution within the battery, it reduces localized overheating that drives incomplete combustion (a primary source of CO). However, its viscoelastic nature allows partial retention of internal pressure, leading to delayed electrolyte ejection and prolonged high-temperature reactions, thereby increasing flue gas temperature.

Aerogel felt, despite its ultra-low thermal conductivity (0.021 W/m·K), paradoxically produced the highest CO concentration (3,658 ppm). We propose two mechanisms: (1) Thermal Insulation Effect: The aerogel's insulating properties prolong the battery's internal heat retention, delaying venting and extending the duration of incomplete organic solvent decomposition (e.g., EC/DMC electrolytes), which preferentially generates CO over CO2 under oxygen-limited conditions. (2) Structural Degradation: Post-TR imaging reveals porous channels, which may trap combustion intermediates and promote CO formation through heterogeneous reactions.

Interestingly, an increase in CO concentration does not necessarily correlate with a rise in flue gas temperature. Except the battery wrapped in thermal conductive gel, other batteries exhibited a decrease in flue gas temperature during TR. The elevated CO concentration indicates a more stable release of flue gas, which correlates with fewer ejections of high-temperature sparks. Such spark ejections typically elevate the overall flue gas temperature. In contrast, the battery wrapped in thermal conductive gel experienced more vigorous ejection of internal separators and electrolyte, resulting in a decrease in CO concentration but an increase in flue gas temperature. Moreover, after the conclusion of TR, the ambient temperature was generally higher than it had been before the sharp increase in flue gas temperature.

Comparison of mass changes and visual changes in batteries and materials before and after thermal runaway

-

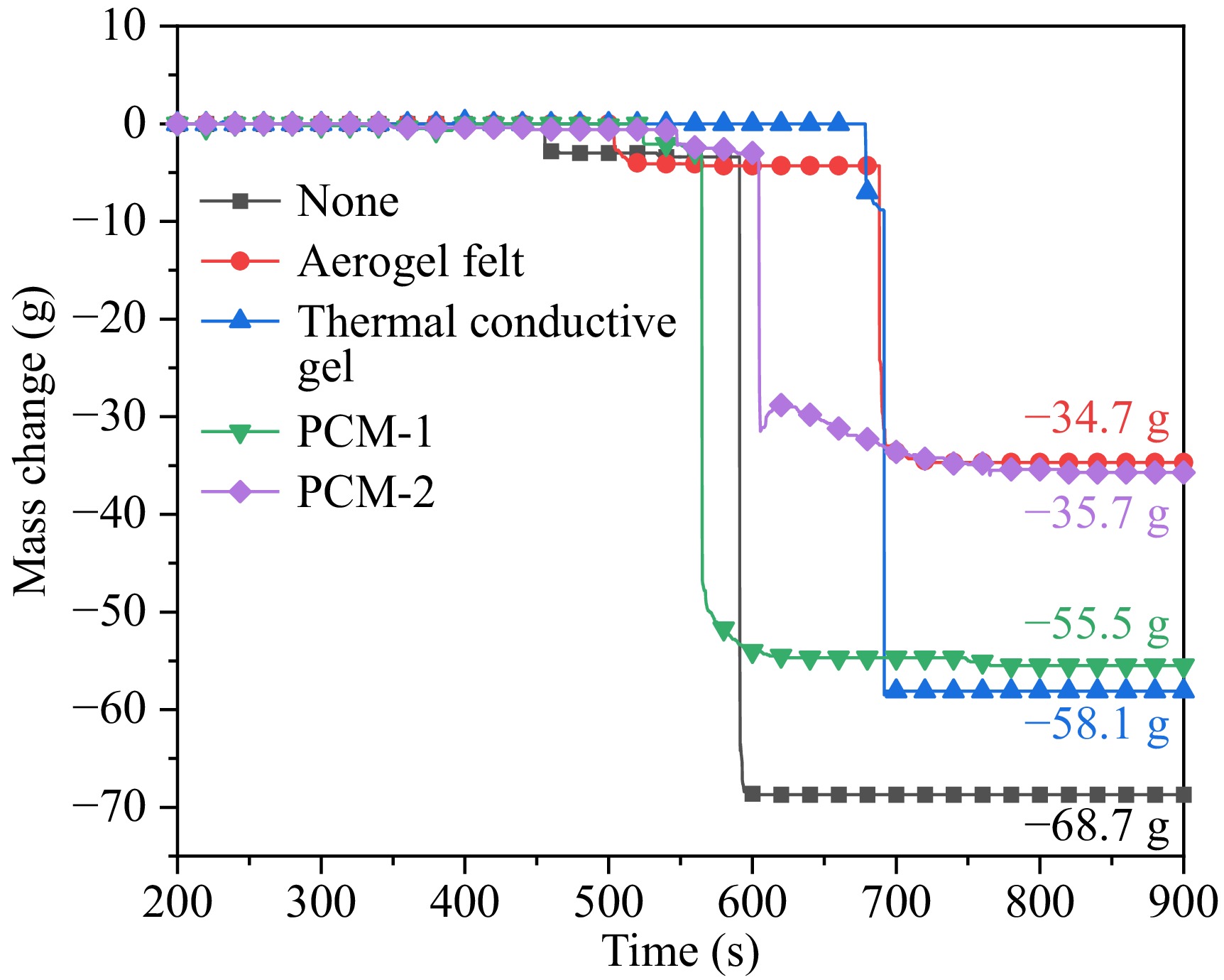

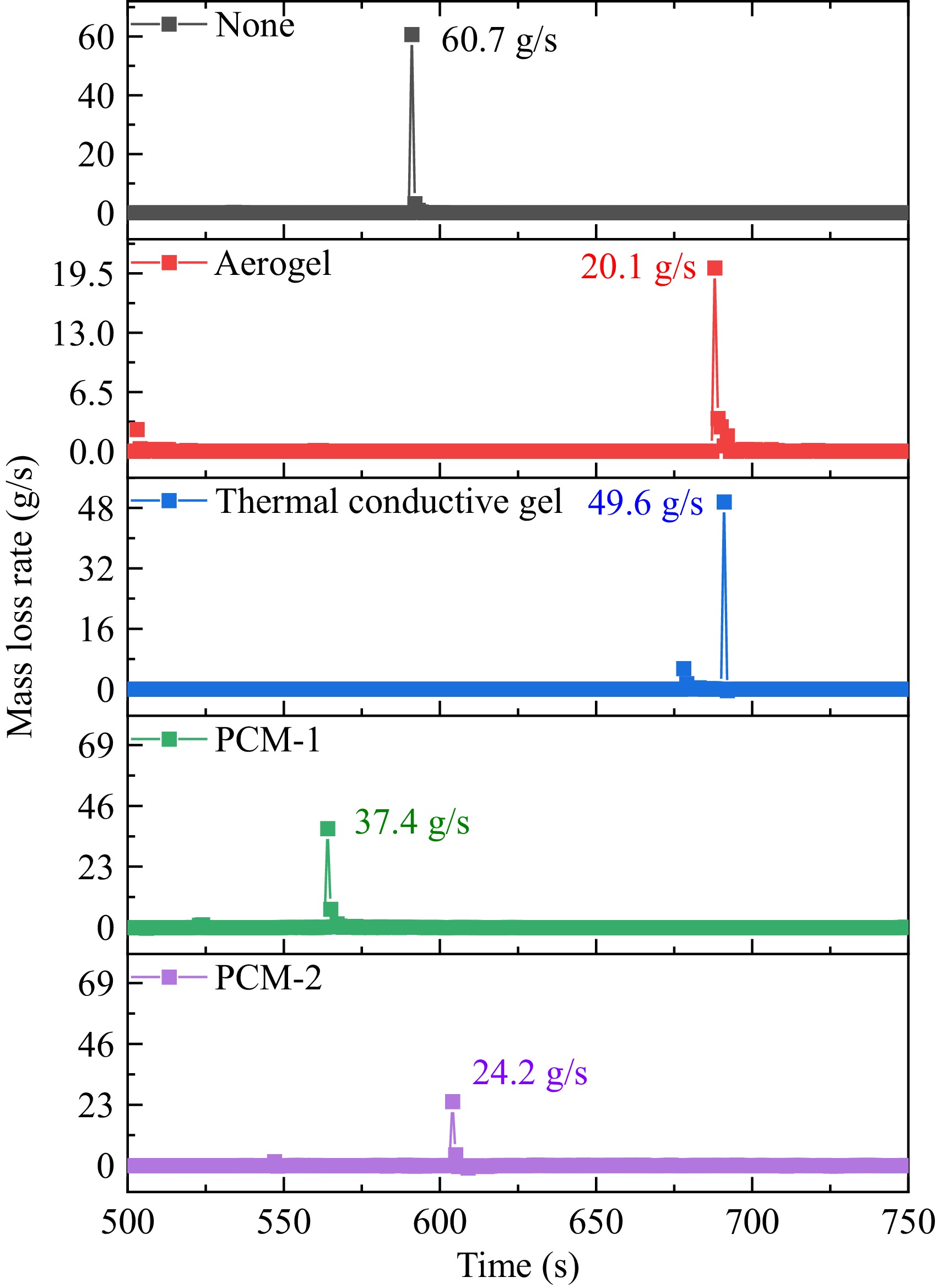

Figure 5 illustrates the absolute mass changes of unwrapped and various wrapped 21700 batteries during the TR process. Compared to the mass change of the unwrapped battery, those wrapped in aerogel and thermal conductive gel exhibited a lower overall mass loss. In contrast, batteries wrapped in PCM-1 and PCM-2 experienced greater mass losses. The reduced ejection of electrolytes and sparks from the aerogel, thermal conductive gel, and phase change material-wrapped batteries resulted in lower mass loss compared to the unwrapped battery.

Figure 6 presents the variation in mass loss rates based on the observed mass changes of the different wrapped batteries. The maximum mass loss rates for the batteries under different wrapping conditions ranged from 20.1 to 68.5 g/s, with the sequence being: unwrapped battery > thermal conductive gel > PCM-1 > PCM-2 > aerogel. This indicates that the choice of wrapping material significantly influences the mass loss dynamics during TR, with aerogel providing the most effective protection. While the current calculation focuses on battery mass loss, future studies will include control experiments with wraps alone to isolate their thermal decomposition effects.

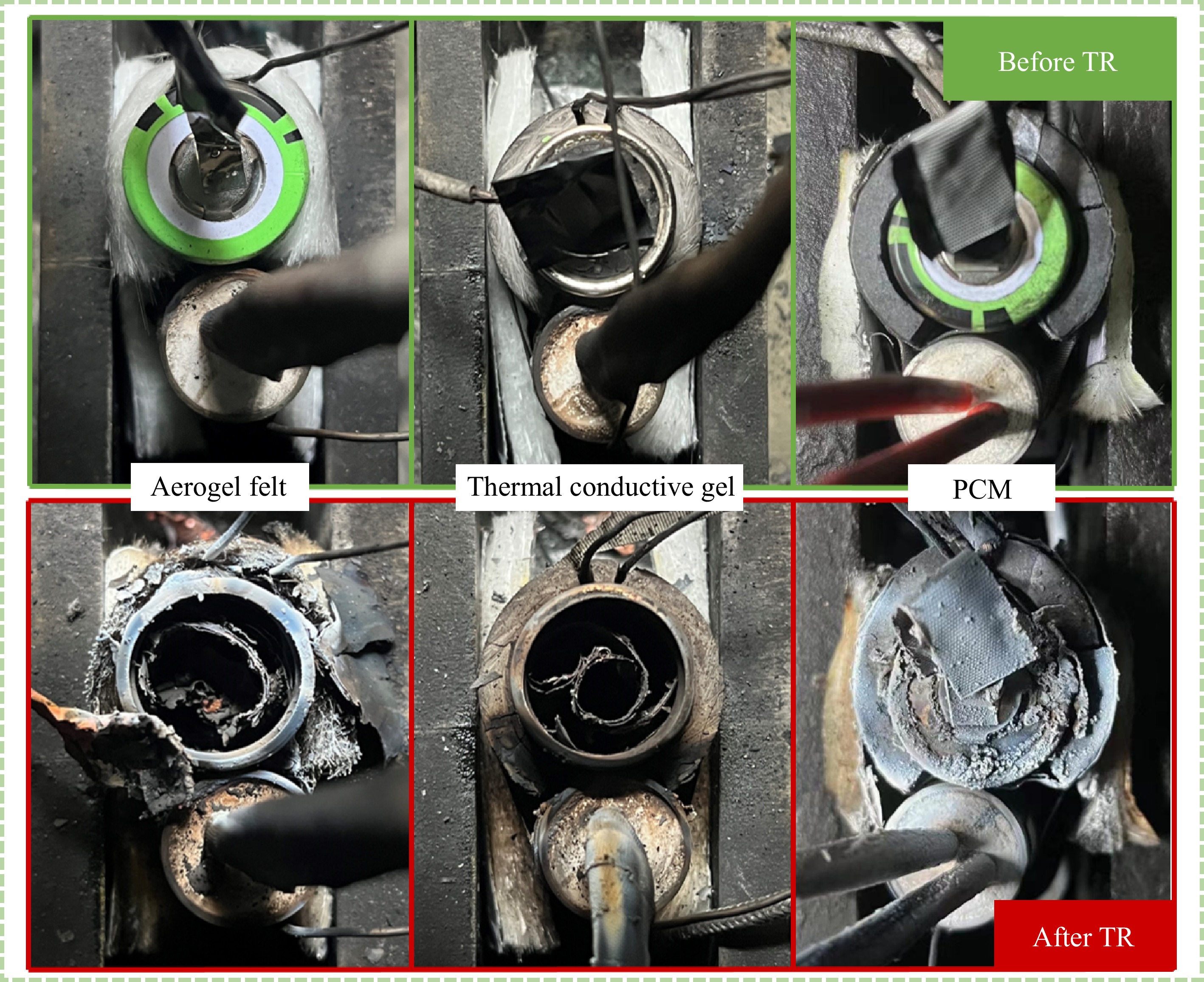

Figure 7 presents the visual appearances of the batteries and materials before and after TR. The images indicate that significant deformation occurred in the aerogel blanket after TR. This deformation can be attributed to the material's low melting point and its response to rapid temperature increases during TR. Similarly, both PCM-1 and PCM-2 also exhibited deformation and cracking. This is primarily due to the phase change temperature of the paraffin component, which is 42 °C. As the TR generates substantial heat, the material absorbs this heat, causing the paraffin to melt, softening the material and eventually leading to its deformation and cracking. In contrast, the thermal conductive gel displayed minimal changes in appearance before and after TR, with only some localized charring observed. The gel's ability to maintain its physical integrity despite thermal stress can be attributed to its excellent flame-retardant properties, as well as its good hardness and high thermal conductivity. These characteristics enable the gel to effectively resist deformation and maintain its structure even under extreme conditions. The images also show that, following TR, the batteries' safety valves were expelled due to the release of internal electrolytes. This phenomenon is a typical result of internal pressure buildup during TR, which forces the safety valves to rupture, leaving behind remnants of the damaged internal materials.

Figure 7.

Battery and material appearance before and after thermal runaway under different protection materials.

These results highlight the critical role of wrapping materials in mitigating the risks associated with TR in LIBs, especially in applications where battery safety is paramount, such as EVs and large-scale energy storage systems. The materials tested in this study demonstrate varying degrees of effectiveness in delaying the onset of TR and minimizing structural damage during the process. For practical applications in battery thermal safety, the choice of material is highly dependent on the specific needs of the system. Aerogels, with their excellent thermal insulation properties, could be especially useful in situations where rapid heat dissipation needs to be prevented. However, as shown in the results, their structural integrity can be compromised during the high heat flux of TR, suggesting they might be more suitable for systems where the primary concern is delaying heat buildup rather than managing it post-failure. PCMs, which absorb and store heat, could be ideal for applications requiring effective heat management over extended periods. Their ability to absorb excess heat and prevent immediate TR progression could make them an important safety feature in large battery packs where the risk of cascading TR events must be minimized. The thermal conductive gel, with its flame-retardant properties and ability to withstand high temperatures without significant deformation, is promising for environments where both fire resistance and thermal conductivity are essential. Its stability under thermal stress, as shown in our study, makes it a strong candidate for practical applications, particularly in battery packs used in electric vehicles and other high-power storage systems.

Comparative analysis and discussion of the influence of wrapping materials on thermal runaway characteristics

-

The impact of different wrapping materials on the TR process in LIBs, focusing on two key aspects: (1) the effect of insulation and heat absorption properties before TR occurs, and (2) the influence of wrapping materials on combustion efficiency during TR.

The insulation and heat absorption capabilities of the wrapping materials play a critical role in delaying the onset of TR. Before the TR is triggered, materials with higher heat absorption properties, such as aerogel and PCMs, effectively suppress the rate of temperature rise within the battery. This delay in temperature increase directly contributes to postponing the triggering of TR, which is evident in the data shown previously. Specifically, the onset of TR is significantly delayed in batteries wrapped in these materials compared to unwrapped batteries, with aerogel and thermal conductive gel exhibiting the strongest effects in delaying both the onset of TR and safety valve rupture times.

The second major effect of the wrapping materials is their influence on the combustion efficiency once TR is triggered. Combustion efficiency is crucial in determining the amount of gas released during TR, as well as the rate of mass loss and the generation of CO. As shown in Fig. 4, the wrapping materials with better thermal insulation and heat absorption properties, such as PCMs and aerogel, are more effective in reducing the amount of CO generated. This results in a lower peak CO concentration and a slower rate of mass loss compared to unwrapped batteries. On the other hand, materials with higher thermal conductivity, such as the thermal conductive gel, tend to accelerate the combustion process, leading to a higher CO generation and more intense mass loss, as observed in Figs 5 and 6. These differences in combustion efficiency are closely linked to the observed changes in mass loss rate, with some materials showing a greater reduction in peak mass loss compared to others.

Understanding heat transfer during the TR of LIBs is critical for improving safety and designing effective thermal management strategies. The TR process of a single battery involves several stages, including the rupture of the safety valve, gas release, TR, and the ejection of sparks and flames. Before the onset of TR, the battery is heated by a heating rod through both conduction and radiation. The wrapping materials applied to the battery, such as aerogel, thermal conductive gel, and PCMs, play a key role in modifying heat transfer during this process.

The aerogel blanket exhibits excellent thermal insulation properties. It significantly reduces the heat transfer by radiation from the heating rod, thus delaying the battery's temperature increase. The nanostructure of aerogel, with its numerous pores and high surface area, enhances its ability to absorb and diffuse heat from the surrounding air. This absorption and diffusion process not only lowers the temperature of the battery but also extends the time required for the battery to reach the critical temperature necessary for TR, effectively delaying its onset. In contrast, the thermal conductive gel has high thermal conductivity, which allows it to absorb heat from both the heating rod and the battery. The gel then efficiently transfers this heat to the surrounding medium or environment. Additionally, it serves as an effective insulator against heat transfer through radiation. Batteries wrapped in thermal conductive gel exhibit the lowest heat absorption before TR, resulting in the longest delay time for the TR process. This is because the gel facilitates rapid heat dissipation to the environment, reducing the temperature build-up within the battery. PCMs, known for their high latent heat and strong thermal conductivity, absorb significant amounts of heat transferred from the heating rod. As a result, batteries wrapped in PCMs accumulate substantial heat before reaching TR. Consequently, the timing of safety valve rupture and the onset of TR in PCM-wrapped batteries is closer to that of unwrapped batteries. While PCMs are effective at absorbing heat, their slower heat dissipation capabilities make them less effective in preventing TR compared to aerogel and thermal conductive gel.

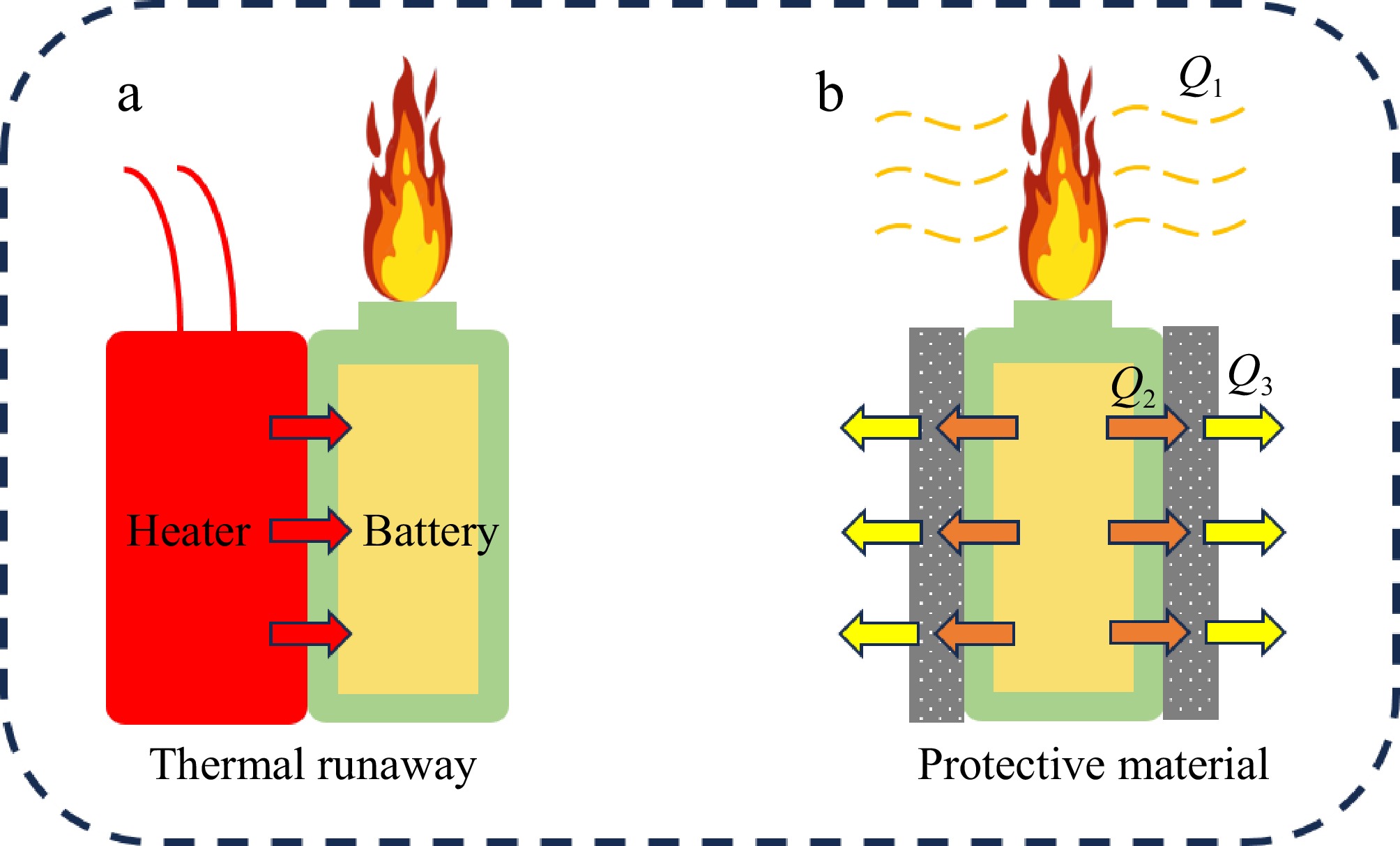

Figure 8 provides a visual representation of the heat transfer dynamics during battery TR. When TR occurs, the flames and sparks emitted from the battery transfer heat to the surrounding environment, referred to as Q1. Due to the poor thermal conductivity of air, the insulating effect of the wrapping material ensures that heat generated by the battery is effectively contained and transferred. The battery itself transfers heat to the wrapping material through conduction, and the material subsequently radiates some of this heat to the environment, represented by Q2 and Q3, respectively.

From a systemic heat transfer perspective, we observe the following dynamics:

Q1 (Heat Emission): The order of heat emission during TR is as follows: thermal conductive gel > aerogel > PCMs. This indicates that batteries wrapped in thermal conductive gel are more likely to emit intense flames and sparks.

Q2 (Heat Absorption): The order of heat absorption is: PCMs > aerogel > thermal conductive gel. This shows that PCMs are more effective at absorbing heat from the battery, thereby delaying the propagation of TR by redistributing the thermal energy.

In summary, while aerogel and thermal conductive gel materials significantly delay the onset of TR by insulating and absorbing heat, the performance of phase change materials is less effective in preventing TR, as they primarily serve to absorb heat without sufficient heat dissipation. The ability of each material to influence heat transfer is central to understanding the effectiveness of these materials in mitigating the risks associated with LIB TR.

Future applications

-

The insights from this study open transformative pathways for next-generation battery safety technologies. For electric vehicles, the thermal conductive gel's dual capability to delay TR onset by 97 s while maintaining structural integrity could be integrated into battery module interconnects, enabling critical time buffers for onboard safety systems to isolate damaged cells. Conversely, PCMs, with their superior heat absorption capacity, are particularly promising for stationary energy storage systems where gradual heat dissipation prioritizes over rapid ejection suppression. The observed correlation between aerogel's insulation properties and elevated CO emissions necessitates hybrid solutions. For instance, aerogel-PCM laminates could be deployed in aviation battery packs where weight minimization is paramount. Furthermore, the material-specific flame intensity profiles (e.g., thermal conductive gel's high-flame emissions vs PCMs' subdued reactions) could guide the development of tiered emergency response protocols: battery enclosures using thermal conductive gel might integrate embedded flame-retardant microcapsules triggered at 150 °C, while PCM-based systems could leverage their stable heat release to power self-actuating cooling circuits. These applications, grounded in our quantified performance metrics, highlight the potential for customized thermal management architectures across industries.

Thermal safety of batteries holds paramount significance for the widespread adoption of new energy vehicles and renewable energy storage systems, as TR remains a critical risk factor leading to catastrophic failures, fires, or explosions[34]. Advanced thermal safety materials, such as phase-change composites, flame-retardant aerogels, and thermally conductive ceramics, play a dual role in mitigating these risks: they not only dissipate heat efficiently to maintain optimal operating temperatures but also physically isolate thermal propagation and suppress hazardous chemical reactions[35]. For instance, flexible phase change materials integrated with cooling systems can homogenize temperature distribution in battery packs, while nanocomposites like zirconia-enhanced aerogels demonstrate exceptional capabilities in blocking heat and toxic gas diffusion during TR events. However, current solutions still face limitations in dynamic adaptability, long-term stability under extreme conditions, and environmental trade-offs, such as nanoparticle pollution or non-recyclable components.

Looking ahead, the convergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and novel materials promises transformative breakthroughs. AI-driven thermal management systems, leveraging real-time data from embedded sensors and predictive algorithms, could dynamically adjust cooling strategies based on battery usage patterns, ambient conditions, and degradation states[36,37]. For example, fuzzy logic or deep learning models might optimize coolant flow rates, activate self-healing thermal barriers, or preemptively shut down risky modules before TR initiates[38,39]. Simultaneously, next-generation materials like stimuli-responsive polymers, bio-based phase-change composites, or graphene-enhanced thermal interfaces could autonomously adapt their properties, such as switching between insulating and conductive states, to address transient thermal spikes. Furthermore, AI-powered digital twins could simulate battery behavior across lifecycle stages, identifying failure precursors and guiding material redesigns for enhanced safety and sustainability. This synergy between smart materials and adaptive intelligence will not only minimize energy consumption, critical for reducing carbon footprints but also enable closed-loop recycling systems to recover and repurpose thermal safety components. By bridging material innovation, intelligent control, and eco-design principles, the future of battery thermal safety will prioritize both human safety and planetary health, accelerating the global transition to carbon-neutral energy systems.

-

Through a comprehensive experimental analysis of the four wrapping materials, this study explores their specific roles and efficiencies in suppressing TR in LIBs. The experimental data indicate that wrapping with aerogel, thermal conductive gel, and phase change materials significantly delays both the onset of TR and the safety valve rupture time. Notably, the thermal conductive gel and aerogel exhibit the strongest suppression effects, with delays of 97 and 99 s in TR onset, respectively, while phase change material PCM-1 only influences the safety valve rupture time.

The experiments also revealed that batteries wrapped in aerogel produced the highest CO concentration during TR, likely due to the inherent properties of the material. The maximum mass loss rate of batteries under different materials indicates that the unwrapped battery experienced the highest loss rate, while those wrapped in thermal conductive gel tended to emit more intense flames. In contrast, the phase change materials were more effective at absorbing and transferring heat, thereby reducing the severity of TR.

In summary, thermal conductive gel and phase change materials demonstrate significant potential for applications in LIB thermal management systems. They can effectively enhance the safety and reliability of batteries under extreme conditions, providing important insights for the future development of battery technology.

This research was supported by Zhenjiang Science and Technology Plan Social Development Project (ZK20240533), Shanghai Key Projects of Soft Science (24692105900), the School of Emergency Management of Jiangsu University, and Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center of Technology and Material of Water Treatment.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: supervision, coordination of the whole study: Chen M; methodology, results analysis: Chen Y; data collection, processing, and paper writing: Zhu M; review of the results, manuscript revision and editing: Chen M, Chen Y, Zhu M. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Tech University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Chen Y, Zhu M, Chen M. 2025. Comprehensive experimental research on wrapping materials influences on the thermal runaway of lithium-ion batteries. Emergency Management Science and Technology 5: e007 doi: 10.48130/emst-0025-0005

Comprehensive experimental research on wrapping materials influences on the thermal runaway of lithium-ion batteries

- Received: 11 November 2024

- Revised: 24 March 2025

- Accepted: 28 March 2025

- Published online: 22 April 2025

Abstract: This study investigates the effectiveness of different wrapping materials, namely aerogel felt, thermal conductive gel, and two phase change materials (PCMs) in mitigating thermal runaway in lithium-ion batteries. The experimental results reveal that all the materials tested delay the onset of thermal runaway and safety valve rupture compared to unwrapped batteries. Specifically, aerogel felt and thermal conductive gel offer substantial thermal runaway inhibition, delaying the safety valve rupture time by 97 and 99 s, respectively. PCM-1 demonstrates a delay in safety valve rupture but has a limited impact on the onset of thermal runaway. Among all materials, thermal conductive gel shows the most significant impact, postponing both safety valve rupture and thermal runaway onset. In contrast, the PCMs exhibit relatively weaker effects. Furthermore, batteries wrapped in aerogel felt produce the highest CO concentration during thermal runaway, reaching 3,658 ppm. The maximum mass loss rate of the batteries varies with the wrapping material, ranging from 20.1 to 68.5 g/s, with the unwrapped batteries exhibiting the highest loss rate. Overall, the results suggest that thermal conductive gels and phase change materials improve the safety and emergency response of lithium-ion batteries under extreme conditions, with the thermal conductive gel showing the most promising results in delaying both safety valve rupture and thermal runaway.