-

GIT-NECs are extremely rare tumours accounting for 0.1% to 1% of all GIT malignancies. A retrospective study of 2,314 GIT-NEC cases drawn from the National Cancer Database between 2014 and 2016 reported that the most common sites of NECs were colo-rectum and anal canal (51.9%), followed by the stomach and oesophagus together (25.9%), while pancreatic and gall bladder NECs accounted for 18.3% and 3.84% of cases each. Colon was singularly the most common primary site involved (30.1%). Overall, while SmCC constituted 30.9% of cases, the rest was made up of other histological variants[1]. In the colon, they are common in the rectosigmoid and caecum, are highly aggressive, and distant metastasis at presentation is almost always the rule[2]. NECs account for 5% of all NET of the small bowel and occur mainly in the ampulla region. Primarily, men over 60 years are affected. In general, NENs present late due to lack of well-defined clinical manifestations or carcinoid syndrome, the latter seen in < 5% of NENs overall. This is because of the metabolism of neuro-endocrine substances secreted by the tumour cells by entero-hepatic circulation, making them undetectable by biochemical screening. Thus, most smaller tumours are missed and only larger tumours manifest when they have liver secondaries producing carcinoid syndrome by bypassing entero-hepatic circulation or by causing local obstructive symptoms. On immunohistochemistry, they possess molecular markers of neuroendocrine differentiation; synaptophysin usually stains positive while chromogranin A (CgA) is less frequently positive. Treatment is usually palliative chemotherapy with platinum agents in metastatic disease. Loco-regional disease is treated with sequential or concurrent chemoradiation (depending on the site) followed by surgery with unclear outcomes. In rare cases of localised tumours, surgery is followed-up with adjuvant chemotherapy with or without radiation. Nonetheless, prognosis remains dismal, with median survival durations of 34, 14, and 5 months in patients with localized, loco-regional, and distant disease, respectively even for those receiving appropriate treatment. Here, we present a case of SmCC involving the ileo-caecal junction with liver and possibly bilateral adrenal gland metastasis presenting as an acute abdomen due to tumour perforation. He underwent an emergency limited right-hemicolectomy with end ileostomy and a distal colonic mucous fistula. He made good progress in the immediate post-operative period but we were informed by his care-giver that he had expired suddenly about 2 weeks after discharge, possibly from an unrelated cause aggravated by surgery. This case highlights the gravity of the diagnosis and the unexpectedly disastrous outcome in our case despite early surgery and adequately addressing the peritoneal sepsis.

-

We present the case of a 66-year-old male who came to the surgery out-patient department in 2023. He gave us a history of continuous right lower abdomen pain for three months along with perceptible but unquantified weight loss and loss of appetite. The pain had gotten worse in the last three days with frequent bouts of fever that subsided with oral paracetamol. The patient also felt his urine output had reduced noticeably since. The abdomen pain was dull-aching, boring, and now felt all over the abdomen. There was no history of abdomen distension, vomiting, change in stool frequency, colour or form, jaundice, or urinary complaints. He had systemic hypertension under control with regular oral antihypertensive medication. He gave no history of heart disease or previous surgeries. He was dehydrated, had an ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) performance score of 2, with pulse rate - 103/min, temperature of 39.4 °C, and a blood pressure of 100/60 mm Hg. His abdomen was distended with diffuse tenderness and guarding. A vague ill-defined firm mass of approximately 6 × 8 cm size with limited mobility was palpable in the right iliac fossa. Per rectal examination showed no abnormality apart from pellet-like stools. Except for leucocytosis (14,620 cells/cu mm), other blood cell counts, serum electrolytes, renal and liver function tests were within normal limits. Chest X-ray was normal.

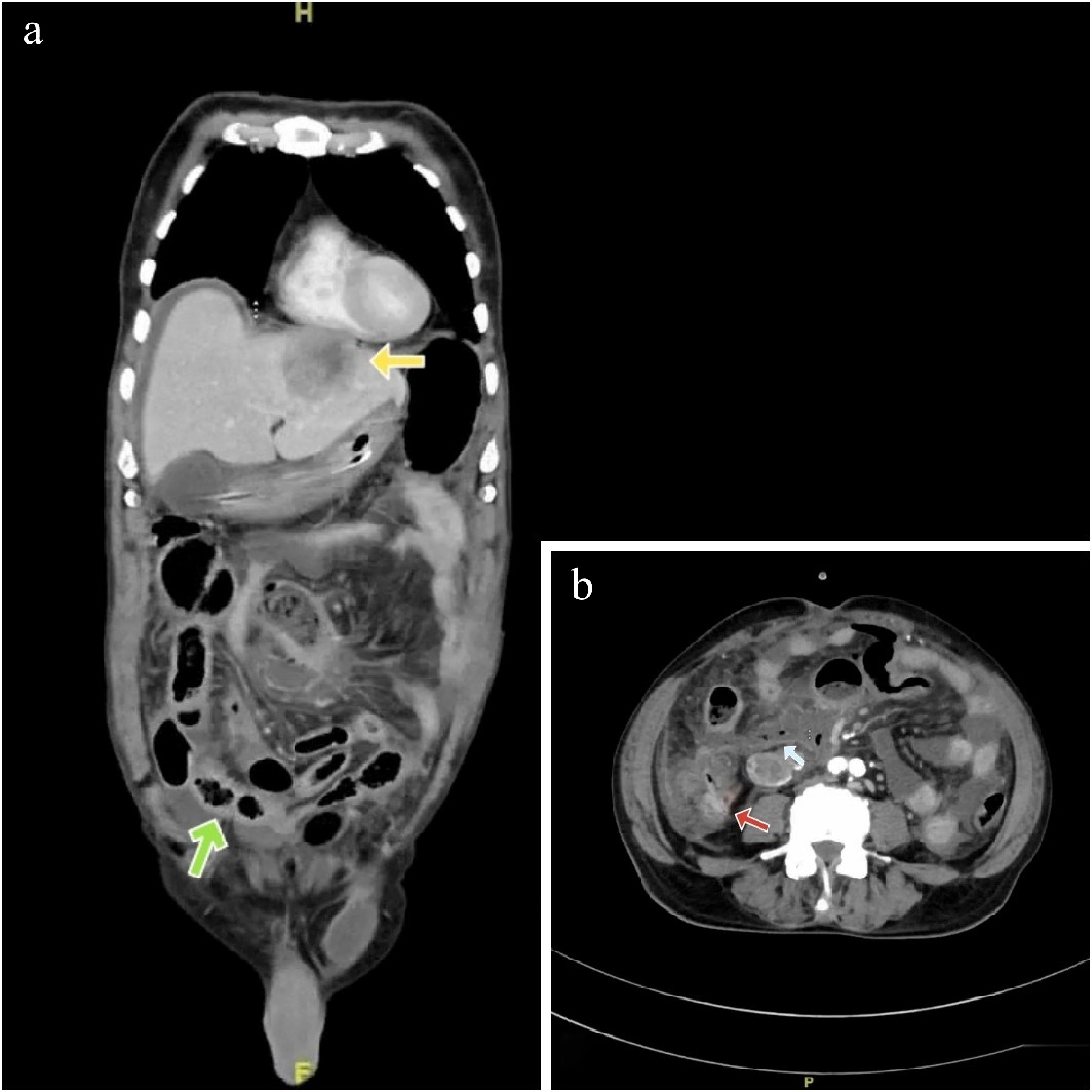

Intravenous contrast CT of abdomen showed an irregular asymmetric hyper-enhancing circumferential wall thickening seen in the terminal ileum and ileo-cecal junction for a length of 4.5 cm (Fig. 1a) with a focal wall defect in the anterior wall of terminal ileum and extraluminal air foci suggestive of perforation (Fig. 1b). Moderate ascites with diffuse mesenteric and omental fat stranding was also seen. Multiple hyper-enhancing enlarged nodes along the right ileo-colic vessels and a well-defined irregular heterogeneously enhancing lesion with central non-enhancing areas and peripherally enhancing solid components measuring 5 cm seen in segments 2 and 3 of the liver in the arterial phase, likely metastatic with central necrosis, was reported (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Yellow arrow - heterogenous, peripherally enhancing lesion in segments 2, 3 of liver (Hounsfield units: min- 10, max- 120, avg- 84). Green arrow - hyperenhancing circumferential thickening of the terminal ileum and ileo-caecal junction (Hounsfield units: min- 15, max- 100, avg- 60). (b) Red arrow showing thickened enhancing wall of ileo-caecal junction and a light blue arrow showing extraluminal gas pockets (Hounsfield units: min- 600, max- 1000, avg- 890).

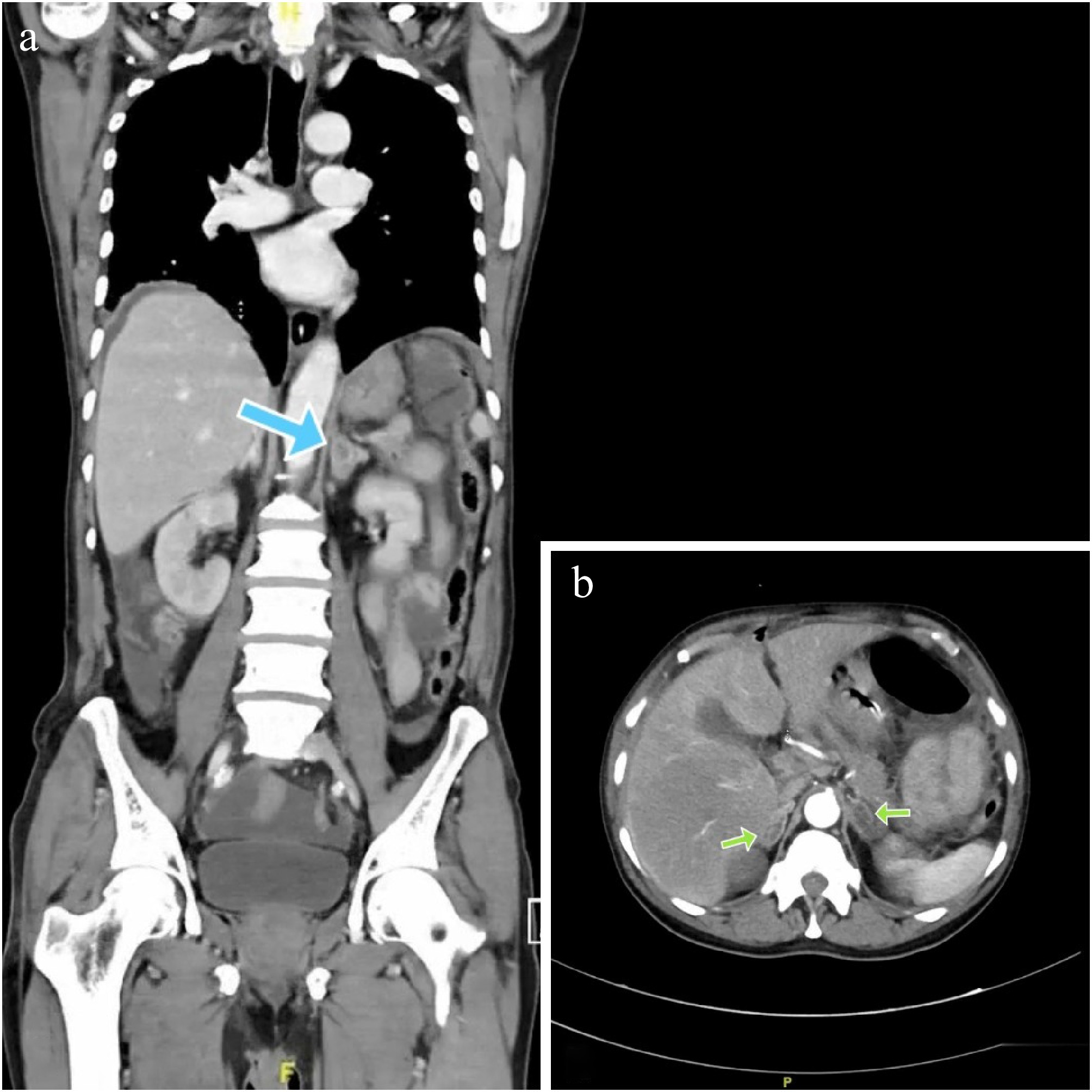

There were ill-defined hypodense areas seen in bilateral adrenals, likely metastatic deposits (Fig. 2a & b).

Figure 2.

(a) Blue arrow showing a hypodense lesion in the left supra-renal gland. (b) Green arrows showing bilateral hypodense adrenal lesions (Hounsfield units: min- 20, max- 104, avg- 38).

Due to worsening sepsis, the patient had exploratory laparotomy under vasopressor support. Around 300 ml of frank purulent material was drained and the omentum was found adherent to the small bowel loops, ascending colon, and the parietal wall. A hard mobile 7 × 5 mass was found at the ileo-caecal junction involving the caecal wall with serosal involvement and ulceration (Fig. 3). A limited right hemicolectomy was performed removing 9 cm of the distal ileum and 10 cm of the right colon. A hard 2 × 2 cm lymph node was found fixed to the right common iliac artery. An end ileostomy with a distal mucus fistula was created. The patient was extubated on the first post-operative day and discharged on day 7 uneventfully.

Figure 3.

Emergency limited right hemicolectomy specimen showing the growth involving the ileo-caecal junction.

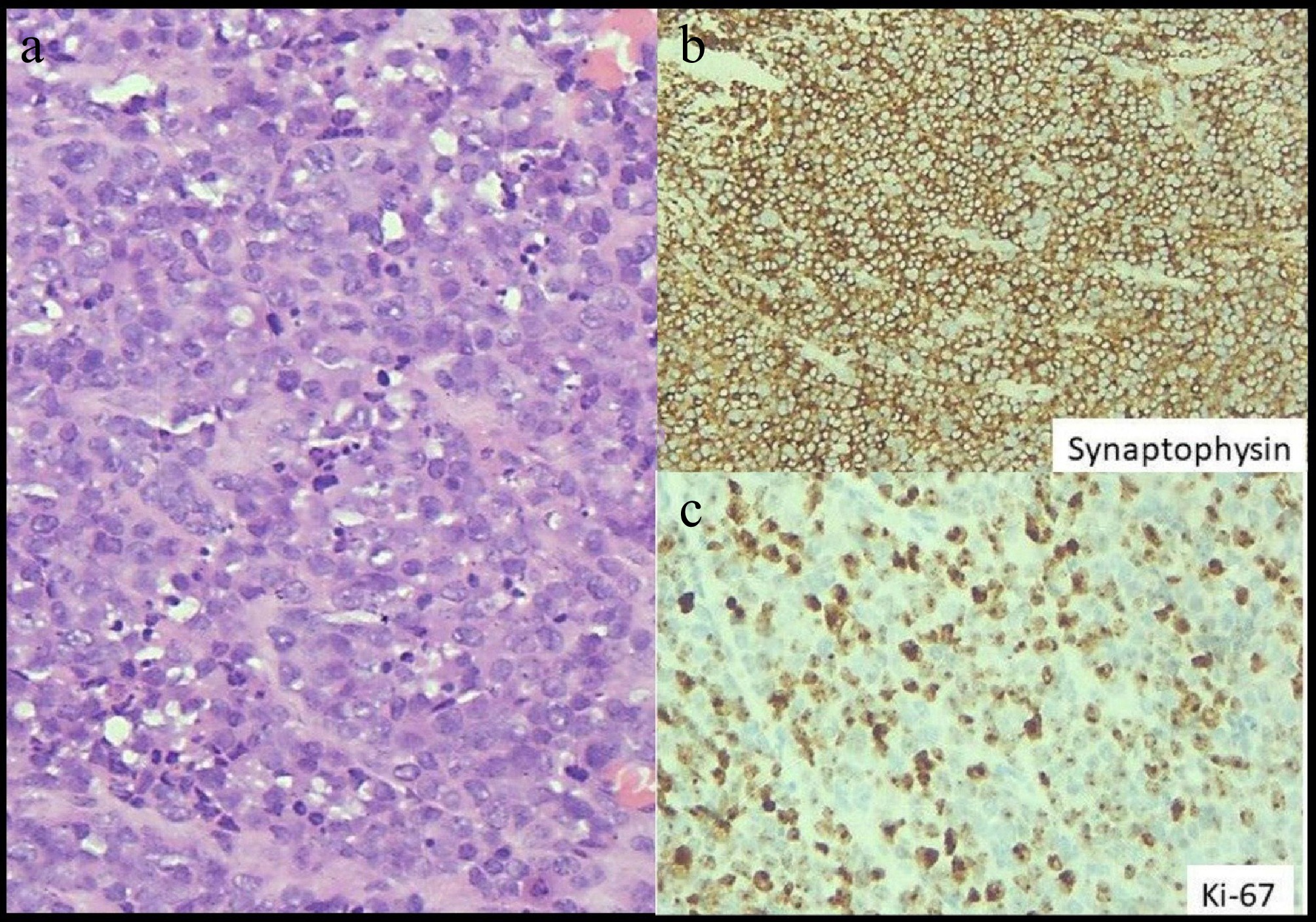

Histopathological examination of the operative specimen showed sheets of tumour cells which were monomorphic, round to oval with vesicular chromatin, moderate eosinophilic cytoplasm, areas of necrosis with apoptotic debris and no lympho-vascular invasion (Fig. 4a). Mitosis was 30 per 10 HPF and Ki67 index was 75% (Fig. 4c). On immunohistochemistry, the tumour cells were diffusely positive for synaptophysin (Fig. 4b), weakly positive for chromogranin A and negative for CD3, CD20, CD117 and cyclin D1. The tumour had breached the serosa and all three lymph nodes submitted were negative for tumour deposits. The diagnosis was small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (pT4a N0 Mx).

Figure 4.

(a) Highlights sheets of tumour cells with round to oval nuclei and ill-defined cell membrane. Nuclei exhibits stippled chromatin, with high mitotic and apoptotic activity. Haematoxylin and eosin stain, x 400. (b) Highlights diffuse strong cytoplasmic expression of Synaptophysin in tumour cells, immunohistochemistry with Ventana antibody. Diaminobenzidine stain, x 400. (c) Highlights high proliferation index in tumour cells as exhibited by Ki-67 immunoperoxidase stain, immunohistochemistry with Ventana antibody. Diaminobenzidine stain, x 400.

A subsequent serum tumour marker assessment showed near normal levels of carcinoembryonic antigen and Chromogranin A levels at 4.3 and 56.7 ng/ml respectively. A fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET-CT) scan was scheduled 3 weeks post-operatively and palliative chemotherapy with carboplatin and etoposide was proposed. Regrettably, we were notified by the patient’s relative that he had expired at home around the 15th day of discharge from an undetermined cause, presumably an acute coronary event.

-

This case proved diagnostically challenging owing to the vague presentation and ambiguous clinical signs which led us to believe it to be ileal perforation secondary to invasive infection, or worst case, either lymphoma or adenocarcinoma. There were no clinical manifestations of carcinoid syndrome from high serotonin one would expect from a conventional functioning neuroendocrine tumour located in the distal midgut. In the literature, tumour perforation as a complication in NETs has been a rarer presentation relative to complications like obstruction and bleeding, but with more severe and devastating prognostic implications as in our case. We believe that we are reporting the first case of a SmCC at the ileo-caecal junction that had presented with tumour perforation.

According to the latest WHO classification (2022), NENs are broadly classified into well-differentiated NETs and poorly differentiated NECs. Well-differentiated epithelial NETs are graded as G1 NET (no necrosis and < 2 mitoses per 2 mm2; Ki67 < 20%), G2 NET (necrosis or 2–20 mitoses per 2 mm2, and Ki67 < 20%) and G3 NET (>20 mitoses per 2 mm2, or Ki67 > 20%, and absence of poorly differentiated cytomorphology). Neuroendocrine carcinomas (> 10 mitoses per 2 mm2, Ki67 > 20%, and often associated with a Ki67 > 55%) are further subclassified based on cytomorphological features into small-cell and large-cell NECs. GIT-NECs have a high proliferation rate with Ki-67 index > 20%, but most tumours have a Ki-67 index of > 50% to 100%[3]. NECs are always high-grade or poorly-differentiated neoplasms, composed of cells with severe cellular atypia and severely deranged genetic profiles, but mostly retaining neuroendocrine markers. The most frequently mutated genes in GIT-NECs are TP53 (64%), APC (28%), KRAS (22%), BRAF (20%) and RB1 (14%). One study reported that the Ki-67 index was usually > 55% in primary tumours from the oesophagus (67% of tumours), colon (70%) and rectum (80%), whereas in the pancreas only 30% had a Ki-67 ≥ 55%. No difference was observed in the Ki-67 level between SmCC and non-SmCC. This study of 305 patients also reported the small-cell morphology was more frequent in primary oesophageal (75%) and rectal NECs (65%), whereas non-small-cell morphology was more often present in colonic (70%) tumours[4]. Dasari et al in their retrospective study of 2,314 cases of GIT-NECs, reported small-cell morphology predominating in the oesophagus (58%), anal canal (79.7%) and gall bladder (68.5%). Large-cell and other morphological types were the majority in gastric (79%), pancreatic (82%), colon (87.1%) and rectal tumours (62.7%)[1]. Another study classified 87 cases of high-grade GIT-NEC into four distinct categories, based on cytomorphological features: SmCC, large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, mixed NEC (sharing histological features of both SmCC and large cell NEC) and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. They reported that most NECs arising in the squamous lined parts (oesophagus and anal canal) were small cell type (78%), whereas most involving the secretory columnar mucosa were large cell (53%) or mixed NECs (82%); co-existing adenocarcinomas were more frequent in large cell (61%) or mixed NECs (36%) type than in small cell NECs (26%); and focal intracytoplasmic mucin was seen exclusively in large cell or mixed NECs[5].

GIT-NECs are seldom functional and hormone-related symptoms of carcinoid syndrome are almost never seen. Clinical signs and symptoms are therefore due to primary tumour location and metastasis and include abdomen pain, anorexia, fatigue, weight loss, obstruction, and melena[6]. NECs are rarely known to perforate and we were unable to find literature reporting a similar presentation at this location. Tumour markers such as serum CgA and urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid levels are typically not as helpful in NECs as in well-differentiated NETs and not recommended[7]. While CgA is negative, other markers like CEA, CA125 and CA19-9 may be elevated[3].

In addition to CT scans with intravenous contrast, smaller luminal lesions can be picked up by CT-enterography or MR-enterography (magnetic resonance-enterography) for small bowel NETs. Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy uses 111In–diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA)-labelled octreotide to locate small tumours that overexpress somatostatin receptors (particularly subtypes 2 and 5), usually G1 and G2 NETs and may only be diagnostic in about 70% of NECs. This is true of NECs whose Ki-67 index is lower (< 55%). While Gallium-68 DOTA PET-CT was found to be superior to 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with low-grade tumours which express somatostatin receptors, the latter is more useful in NEC as they are PET-avid and do not frequently express somatostatin receptors. It can identify up to 90% of lesions[3] and is indicated in localised disease before surgery or before considering adjuvant chemotherapy to rule out distant metastasis, as this has implications in further course of treatment[8].

SmCC of the GIT is staged according to two staging systems used in parallel in clinical practice: the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC, 2018) TNM staging system for GIT-NEN and the Veterans' Administration Lung Study group (VALSG) for primary SmCC of the lung[9]. The second system consists of two categories, limited disease (LD) and extensive disease (ED). LD is defined as a tumour contained within a localised anatomic region, with or without regional lymph node spread. ED is defined as a tumour spread outside the locoregional boundaries[6]. TNM stage III was observed to be the most common stage at diagnosis for all sites but pancreatic primary tumours were more commonly identified at TNM stage 2 followed by stage 1[1].

In immunohistochemistry, well-differentiated NETs stain for synaptophysin and usually also for CgA, while the poorly differentiated NECs stain for synaptophysin, but only infrequently and sparsely for chromogranin A. Positive CgA staining indicates a more mature tumor, and the presence of both synaptophysin and CgA could be favourable prognostic factors[10]. There is no correlation in CgA staining when comparing SmCC with non-SmCC (52% vs 45%, p = 0.2) and also the CgA staining intensity and the site of the primary tumour[4]. Other immunohistochemical markers showing more than 90% positivity include CK8, NSE and CD56.

In locoregional disease, chemotherapy can be initiated and then, if metastasis is ruled out, surgical resection may be considered. Resectability was highest with colonic NECs (80%) and significantly lower for gastric (31%), rectal (28%), oesophageal (22%) and pancreatic (15%) tumours. Prognosis is better with large-cell morphology in both localised and metastatic disease and SmCCs were also less often resected compared to non-SmCCs (19% vs 34%, p = 0.012)[4]. Patients with localized non-SmCC colorectal NEC had better survival benefits after surgery (21 months vs 6 months), compared to small-cell (18 months vs 14 months), questioning the benefit of surgery for localized small-cell colorectal NEC[8]. First-line chemotherapy for NECs is cisplatin or carboplatin and etoposide for 4–6 cycles. With most patients eventually relapsing, they would require second-line chemotherapy (gemcitabine, everolimus, bevacizumab alongside cisplatin, irinotecan, and etoposide). In general, the prognosis of recurrence and metastasis is grave and response to second-line chemotherapy will be limited. Of note again, is the Nordic NEC study suggesting retreatment with etoposide and cisplatin as up to 42% patients can achieve remission. They also found that tumours with Ki-67 < 55% were less responsive to platinum-based chemotherapy (15% vs 42%, p < 0.001), but had a significantly longer survival than patients with Ki-67 ≥ 55% (14 vs 10 months, p < 0.001) and may constitute a subtype with a favourable prognosis. This includes pancreatic NECs which are often SRS-positive tumours and associated with a lower Ki-67 index[4].

Although surgery is the primary treatment in small or localised tumours, as a sole strategy it is rarely curative. Rates of relapse even after radical surgery is very high, mandating platinum-based adjuvant therapy in this setting. With liver and lymph-node secondaries noted in approximately 80% of patients at the time of diagnosis, prognosis is uniformly poor[2]. Debulking surgery and surgery for liver metastasis are generally not recommended due to high recurrence rates, making palliative chemotherapy the only viable option[3]. The 5-year survival rate for patients with loco-regional disease was from 40% to 50% for pancreatic, gastric and colorectal NECs and 25% for oesophageal NECs. The longest median survival at 28.5 months and 5-year survival of 39.7% was reported with colonic primary tumours, while gall bladder primary tumours had the shortest median survival at 14.8 months with 5-year survival of 20.9%. SmCC had the shortest median survival compared to other histological variants (17.7 months vs 22.3 months)[1]. The overall survival in metastatic NECs on chemotherapy is reportedly between 7 and 19 months and confers a significant survival advantage over those opting for best supportive care who, at best, have 1 month of survival. Adverse prognostic factors include old age, co-morbidities/performance status, stage at presentation, small-cell morphology, colorectal and biliary tract primary tumours, elevated platelet, and serum lactate dehydrogenase levels, and where surgery is an unviable option[1,4].

There also has been a surging interest in the use of targeted therapy like PD-L1 inhibitors to capitalise on the increased PD-L1 expression on poorly-differentiated NETs, with one study showing 41.2% of high-grade NET and NECs expressing PD-L1. However, a study involving dual checkpoint inhibitors i.e. anti-PD-L1 (nivolumab), and anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab), showed only modest response in patients with high-grade NETs who had received prior chemotherapy[11]. While combining chemotherapy with targeted therapy may enhance the anti-tumour activity of the latter, studies have reported that among other variables, tumour mutational burden (TMB) could be a major determinant in evaluating the efficacy of targeted therapy in poorly differentiated NECs. More inquiry is needed to determine the factors that affect the efficacy of these newer agents.

A rigorous follow-up strategy is employed, with all patients who have had radical surgery monitored every three months with CT-scan due to high recurrence rates. Patients solely on chemotherapy should be monitored by CT bi-monthly for response and disease progression[3].

-

The overall prognosis for GIT NECs, regardless of site, is dismal due to metastatic lesions preponderating at the time of diagnosis. The performance status, tumour site, the extent of the disease (ED or LD) at diagnosis and serious complications like tumour perforation are major determinants of prognosis. Palliative resections are commonly performed to alleviate symptoms with subsequent adjuvant chemotherapy while metastatectomy has shown little to no benefit. A few other therapeutic options like targeted therapy are being investigated with modest efficacy and no demonstrable overall survival benefit.

-

All procedures were reviewed and preapproved by the Institutional Ethics Committee for Observational Studies, JIPMER, Pondicherry with identification number JIP/IEC-OS/2024/543 on 15/02/2025.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Arunachalam Jeykumar NS, Krishnaraj B, Maroju NK; data collection: Arunachalam Jeykumar NS, Arumuga Nainar V; analysis and interpretation of results: Nachiappa Ganesh R, Krishnaraj B; draft manuscript preparation: Arunachalam Jeykumar NS. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Arumuga Nainar V, Arunachalam Jeykumar NS, Krishnaraj B, Nachiappa Ganesh R, Maroju NK. 2025. Metastatic small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ileo-caecal junction presenting with tumour perforation - case report of a rare tumour at an unusual site with an uncommon presentation, and literature review. Gastrointestinal Tumors 12: e008 doi: 10.48130/git-0025-0009

Metastatic small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ileo-caecal junction presenting with tumour perforation - case report of a rare tumour at an unusual site with an uncommon presentation, and literature review

- Received: 29 November 2024

- Revised: 10 March 2025

- Accepted: 11 April 2025

- Published online: 29 April 2025

Abstract: Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NEN) arise from neuroendocrine cells distributed in the lining epithelium of the lung, the gastro-intestinal tract (GIT) and genitourinary tract. They are classified into well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumours (NET) and poorly-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC), the latter including large-cell and small-cell variants. NECs are high-grade with aggressive histological features (high mitotic rate, extensive necrosis, and nuclear atypia). Most NECs are locally advanced or metastatic at diagnosis due to their inherent biological aggressiveness and therefore have a grim prognosis. Their peculiarity is characterised by the absence of features of carcinoid syndrome which typify their more differentiated counterparts. In this case report, we discuss a case of small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (SmCC) of the ileo-caecal junction, a rather unusual site, in a 66-year-old male with multiple distant metastases and abdominal signs of perforation peritonitis with septic shock. He underwent emergency laparotomy and ileo-colic resection with a double-barrel enterostomy but succumbed to overall ill-health a fortnight later.

-

Key words:

- Neuroendocrine carcinoma /

- Chromogranin A /

- Case report /

- Tumour perforation /

- Small cell tumour