-

As research into the early stages of life continues, there has been growing evidence that fathers have a significant impact on fetal development[1], giving rise to the concept of Paternal Origins of Health and Disease (POHaD)[2]. The contribution of paternal genes is not limited to genomic information; it also includes the transfer of epigenetic markers to the fertilized egg via the sperm. These markers include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding small RNAs, which are inherited by subsequent generations via germ cells[3]. Research has shown that factors like paternal obesity, high-fat diets, and low-protein diets are linked to reduced sperm quality[4]. Consequently, this article examines paternal nutrition, dietary habits, age, and detrimental lifestyle choices, summarizing their impact on offspring health and disease susceptibility, while linking these elements to epigenetic mechanisms. It is expected that this evidence will provide new perspectives for future preventive work on reproductive health.

-

This process involves adding a methyl group to the fifth carbon of specific cytosine residues in DNA, leading to the creation of 5-methylcytosine (5mC)[5]. This vital epigenetic modification significantly influences gene regulation and the preservation of epigenetic memory, especially in processes such as genomic imprinting and transposon silencing[6,7]. CpG sites, the primary targets for DNA methylation, are scattered throughout the genome, particularly in CpG islands linked to the promoter regions of nearly half of all genes[8,9]. In mammals, around 70%−80% of CpG sites are typically methylated. Paternal epigenetic information can be passed to offspring through the methylation status of these CpG sites, affecting gene expression and developmental processes. The balance of DNA methylation is regulated by DNA methyltransferases, such as Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b, and demethylases from the Tet family[10]. During gametogenesis, primordial germ cells undergo significant demethylation and imprint reset, a process that recurs in the early embryo post-fertilization. These reprogramming mechanisms ensure accurate genetic information transmission, maintaining genomic integrity and stability.

Histone modifications

-

Histone modifications are covalent post-translational alterations of the N-terminal tails of histones, including methylation, acetylation, and phosphorylation. These modifications play a pivotal role in regulating gene expression and maintaining genomic integrity by modulating chromatin structure and transcriptional dynamics[11]. During spermatogenesis, while most canonical histones are replaced, certain specific regions retain histones, which may contribute to intergenerational inheritance[12]. Furthermore, paternal mutations in genes encoding chromatin regulatory factors can result in non-inheritable phenotypic variations in offspring[13]. Notably, paternal nutritional status can induce specific histone modifications in sperm, such as H3K27me3, H3K18ac, and H4K5ac[14−16]. These alterations highlight the potential for epigenetic errors to accumulate in sperm, thereby influencing developmental outcomes in the next generation.

Non-coding small RNAs

-

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are RNA molecules transcribed from the genome that do not code for proteins. Recently, they have gained considerable attention for their roles in epigenetic regulation and intergenerational transmission[17]. Beyond their functions at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels, they are vital in the epigenetic regulation of gene expression[18]. Small non-coding RNAs are epigenetic molecules sensitive to environmental factors in sperm. They are categorized into miRNA, siRNA, and tsRNA based on their origin, length, and function. The ncRNAs in sperm originate not only from the sperm cells but also from extracellular materials provided by epididymal vesicles[19]. These vesicles, derived from epididymal epithelial cells, transfer biomolecules, including proteins and RNA, to sperm during their passage through the epididymis. This mechanism allows genetic information to influence offspring gene regulation through small RNAs found in epididymal vesicles after fertilization[20]. Recent research has shown that a father's diet and lifestyle significantly affect ncRNA expression and thus the epigenetic traits of the offspring[21]. For example, a father's high-fat diet may modify the ncRNA expression profile in his sperm, impacting the metabolic health and behavioral traits of the progeny[22]. Initially regarded as residues of degradation after spermatogenesis, miRNAs, and tsRNAs are now recognized as a class of small regulatory RNAs capable of transmitting non-genetic information across generations.

miRNA

-

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) represent a category of small regulatory RNAs, approximately 22 nucleotides long, that influence the expression of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs) through complementary base pairing. The formation of miRNAs begins with the transcription of miRNA genes by RNA polymerase II, leading to primary miRNA transcripts. These transcripts undergo processing by the microprocessor complex, including Drosha and Pasha/DGCR8, resulting in precursor miRNAs. Subsequently, they are transported to the cytoplasm via Exportin 5[23]. In the cytoplasm, Dicer further processes precursor miRNAs to produce mature miRNAs, which associate with Argonaute (AGO) proteins to form the miRNA-induced silencing complex (miRISC). This complex regulates gene expression by binding to the 3' untranslated region of target mRNAs, thereby inhibiting their translation or facilitating their degradation[13]. In the context of paternal epigenetics, miRNAs are vital for sperm development and maturation. The miRNAs found in sperm play critical roles in early embryonic development. Research indicates that approximately 20% of sperm miRNAs transfer to the oocyte during fertilization, potentially influencing gene regulation in the offspring. Additionally, environmental and dietary factors significantly affect sperm miRNA profiles, suggesting that negative lifestyle choices of fathers may impact the health and development of their children by modifying miRNA expression[24].

tsRNA

-

The synthesis of tsRNA primarily occurs through the cleavage of the tRNA anticodon loop by angiogenin-type RNAase. Under stress conditions, these fragments increase in abundance, forming stress granules that protect transcribed RNA. They can be classified into two categories: one category includes approximately 35 nt fragments resulting from the cleavage of the anticodon loop, while the other consists of about 20 nt fragments derived from the cleavage of the D or T loop[19]. tsRNA not only performs gene silencing functions similar to miRNA but also directly influences translation by binding to ribosomes. In human mature sperm, the predominant type of tsRNA is 5′-tsRNA, constituting half of the 31−33 nucleotides of full-length tRNA. This tsRNA type is vital during the later stages of spermatogenesis and can significantly impact zygotic programming[25]. Fluctuations in tsRNA levels correlate closely with sperm quality, and its profile changes are influenced by environmental factors and diet, subsequently affecting embryonic development and phenotypic characteristics in offspring[26,27]. Paternal dietary stimuli can lead to the upregulation of 5′-tsRNA under certain conditions. In response to stress, cells produce 5′-tsRNA by cleaving mature tRNA to cope with environmental challenges. This upregulation hinders the translation of associated genes by binding to the 3′ UTR of mRNA, thereby affecting the expression of developmental and metabolic genes and raising health risks in offspring[28].

Epigenetic interactions and collaborative functions

-

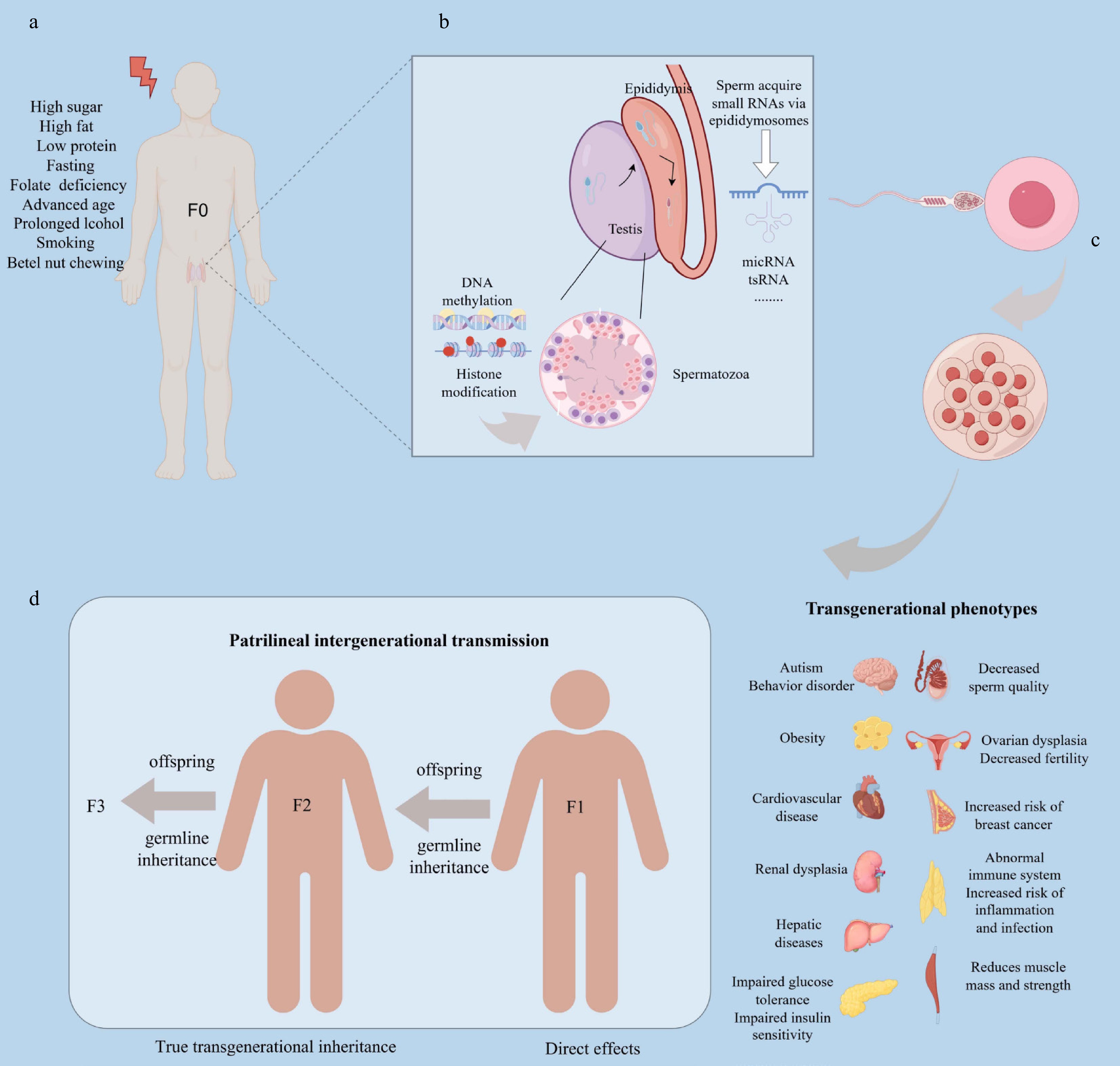

Scientific research typically focuses on a single mechanism as the starting point for exploration. However, within organisms, processes such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNAs do not function in isolation but rather operate through complex, interdependent networks that collectively regulate gene expression[29]. As illustrated in Fig. 1, paternal environmental exposures can induce epigenetic changes in sperm, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and alterations in small non-coding RNAs such as miRNAs and tsRNAs. These epigenetic modifications not only affect chromatin structure and gene accessibility but also interact with each other. For example, DNA methylation can alter histone modification states and change chromatin structure. Conversely, histone modifications can also dictate the distribution of DNA methylation. Additionally, non-coding small RNAs, including miRNAs and tsRNAs, influence both DNA methylation and histone modifications, indirectly affecting the stability of gene expression and the transmission of genetic information. For instance, miRNAs recruit histone deacetylases (HDACs), resulting in chromatin compaction and suppression of target gene expression[30]. This interaction not only ensures multi-layered gene expression regulation but also provides cells with the adaptability to respond to environmental shifts, driving complex regulatory mechanisms in development, differentiation, and disease progression[31].

Figure 1.

Mechanism of epigenetic influence on offspring health by paternal exposure. This process consists of four stages: (a) Environmental exposure phase: a father's nutritional status, dietary habits, age, and lifestyle choices influence spermatogenesis, primarily through epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation and histone modifications. (b) Epididymal and sperm maturation phase: during the epididymal phase, environmentally responsive small RNAs, including tsRNAs and miRNAs, are loaded into sperm via epididymosomes, enabling sperm to carry specific epigenetic information. (c) Fertilization process: sperm deliver this epigenetic information—comprising DNA methylation, histone modifications, and small RNAs—to the oocyte, altering early embryonic gene expression, which may predispose offspring to adult diseases. (d) Transgenerational effects: persistent epigenetic alterations in the germline can directly impact F1 offspring's health, while true transgenerational effects, such as increased cancer risk or metabolic dysfunction, emerge in subsequent generations (F2 and F3). Produced using Figdraw.

-

Animal studies indicate that a father's nutritional status during early life or preconception significantly influences offspring health[32,33]. Low-protein diets in fathers could alter sperm epigenetics, initiating a range of health complications that affect embryonic development and metabolic pathways. These complications included glucose intolerance, metabolic and cardiovascular dysfunction, impaired skeletal growth, and changes in bone mineral deposition[34−36]. Male offspring of fathers on low-protein diets tend to gain weight, while female offspring are usually lighter and have a higher risk of breast cancer[37]. This dietary pattern also affects gene expression in the placenta, resulting in higher levels of DNA methyltransferases Dnmt1 and Dnmt3L, alongside the upregulation of genes related to cholesterol and lipid synthesis. Furthermore, the expression of AMPK pathway-related genes in blastocysts is influenced[36]. Notably, in murine models, a low-protein diet in fathers has been shown to result in the transmission of histone H3K4me3 in sperm to embryos, which is correlated with diet-induced phenotypes in descendants[38]. Such dietary practices may transmit environmental stress effects across generations by silencing relevant genes in sperm and reshaping gene regulatory networks, thereby impacting multi-generational health outcomes. Research by Morgan et al.[39] demonstrates that a paternal low-protein diet significantly modifies the expression profiles of crucial epigenetic marks, including DNA methylation, histone modifications, and RNA methylation in the testes of adult F1 males, which further affects the renin-angiotensin system and cardiovascular function[19]. Additionally, through sperm and/or seminal plasma-specific programming, it alters growth and angiotensin-converting enzyme activity in F2 neonatal offspring, resulting in transgenerational programming effects on cardiovascular function[40].

Effects of paternal starvation or intermittent fasting on offspring

-

Paternal starvation diets or intermittent fasting can transmit stress signals to offspring through mechanisms like DNA methylation and tsRNA expression, which alter gene expression patterns. These alterations may result in metabolic regulation abnormalities, blood glucose level fluctuations, insulin sensitivity issues, and increased fat accumulation in the offspring. Consequently, this leads to lower birth weights and a heightened risk of chronic diseases[40,41].

Animal studies demonstrate that prolonged starvation or fasting in male rats can diminish offspring birth weight, impede growth, alter lipid profiles and blood pressure, increase obesity risk, and heighten the likelihood of type 2 diabetes in their progeny[41,42]. In humans, the Dutch famine (1944–1945) provides critical insights into the transgenerational effects of paternal starvation. Specifically, men who experience famine during their early life are found to have offspring with significantly higher weight and obesity levels in adulthood[43]. While maternal famine likely plays a direct role in shaping offspring health during this period, studies suggest that paternal famine exposure uniquely contributes to offspring outcomes through epigenetic modifications in sperm. These modifications may influence metabolic programming and respiratory health, as evidenced by the increased susceptibility to respiratory diseases and obstructive respiratory conditions in their offspring, and a higher incidence of metabolic diseases in their grandchildren. This underscores the potential for paternal starvation to induce long-lasting, transgenerational health effects independent of maternal influences[44−46].

Impact of paternal folate deficiency on offspring

-

Folic acid, a water-soluble B vitamin, serves as a vital component in numerous multivitamin formulations and grain fortifiers. It plays an essential role in amino acid metabolism and the synthesis of DNA and RNA. The demand for folic acid rises significantly during periods of rapid tissue growth, such as fetal development, where acquiring DNA methylation patterns is crucial[47]. This stage requires an adequate supply of methyl donors. Additionally, during postnatal spermatogenesis, DNA methylation patterns undergo further modifications[48].

Inadequate folic acid intake in fathers affects offspring. Studies show that chronic folic acid deficiency alters sperm epigenetics and raises the risk of embryonic developmental abnormalities, resulting in negative pregnancy outcomes. These outcomes may manifest as lower miscarriage rates, abnormal placental fusion, various craniofacial malformations, limb defects, and developmental delays in muscle and skeletal growth[47,49]. Research by Lambrot et al.[49] and Siklenka et al.[50] further highlights that paternal folate deficiency leads to decreased expression of methyltransferases in sperm, causing reduced methylation of key genes like tumor protein p53 (P53) and phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), both of which are implicated in cancer development in offspring. Furthermore, a father's folic acid status can influence folic acid transport to the placenta, DNA methylation, and mutations, thereby affecting insulin-like growth factor 2 (Igf-2) expression levels in the fetal brain[51]. These factors contribute to metabolic disorders and cardiovascular issues in offspring, particularly impacting female descendants. Additionally, paternal folic acid levels may also affect the offspring's neurological function, cognitive abilities, learning and memory, and increase the risks of depression and anxiety[52,53].

Impact of paternal high-sugar diets on offspring

-

High-sugar diets can induce endocrine disorders in descendants, such as insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, and may also disrupt lipid metabolism, raise blood pressure, cause hyperuricemia, and lead to obesity, thereby heightening the risk of cardiovascular diseases and altering gut microbiota[54,55]. High sugar intake can impair sperm quality and function, affecting epigenetic markers in germ cells, including DNA methylation and histone modifications, which in turn influence the development of fertilized eggs and embryos[56,57]. Research by Sertorio et al.[58,59] shows that paternal high-sugar consumption can transmit epigenomic changes in sperm to offspring, affects their behavior and neurodevelopment. If either parent consumes excessive glucose or fructose, offspring may display increased blood pressure and uric acid levels, reduced adiponectin concentrations, and elevated leptin levels, along with liver metabolic disturbances and increased reproductive fat[60].

Impact of paternal high-fat diets on offspring

Effects on the development of offspring embryos

-

A paternal high-fat diet impacts offspring through epigenetic mechanisms, including small RNAs such as miRNA and tsRNA, and DNA methylation[61−63]. In rodent models of obesity induced by high-fat diets, aberrant methylation of imprinted genes essential for placental and fetal development has been observed in sperm. These genes, including gonadotropin-releasing hormone, prolactin, estrogen, and vascular endothelial growth factor, play critical roles in supporting proper placental and fetal growth[64]. Moreover, hypermethylation of the Pomc (pro-opiomelanocortin) promoter in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus of offspring has been linked to paternal high-fat diet exposure, with 77 differentially methylated regions (DMRs) identified[10]. The adverse effects of paternal obesity on embryonic and fetal health manifest as impaired embryonic development, reduced blastocyst cell numbers, mitochondrial dysfunction, and altered chromatin marks, which collectively disrupt normal placental gene expression[65,66]. Furthermore, studies indicate that paternal obesity reduces fetal and placental weights, independent of maternal in utero high-fat diet exposure[67].

Effects on cardiovascular and metabolic diseases in offspring

-

A father's high-fat diet markedly elevates the risk of cardiovascular disease in offspring through modifications in non-coding RNA (ncRNA)[68]. These genetic changes might have corresponded to epigenetic alterations in the promoters of fat-related genes in offspring mice, including adiponectin and leptin, which can lead to metabolic disorders[69]. Adiponectin, a bioactive peptide secreted by adipocytes, enhances insulin sensitivity, thereby improving insulin resistance and mitigating atherosclerosis. Conversely, leptin, a hormone produced by adipose tissue, interacts with receptors in the central nervous system, influencing biological behavior and metabolism. Notably, during early development, leptin may program metabolism by shaping hypothalamic neural circuit development, resulting in enduring changes in dietary preferences and decreased energy expenditure[70]. Moreover, a father's high-fat diet modifies the tsRNA expression profile, impacting the regulation of genes associated with energy metabolism. This disruption leads to abnormal fat metabolism in offspring, culminating in diminished glucose tolerance, heightened insulin resistance, obesity, and metabolic syndrome. Additionally, pancreatic function undergoes alterations, marked by increased insulin secretion and reduced pancreatic cell volume[21,71,72].

-

Age significantly influenced epigenetic modifications in sperm. As paternal age increased, DNA methylation levels in sperm could change[73,74]. In older males, these levels might either have increased or decreased. Additionally, advancing paternal age affected non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) in sperm, leading to variations in the expression of miRNAs and piRNAs[75]. Abnormal changes in these epigenetic markers played a role in regulating gene expression and signaling pathways in fertilized eggs and embryos, thereby heightening the risk of autism[76−78].

Research on rodents revealed a substantial overlap between genes affected by age-related differentially methylated regions and those influenced by small non-coding RNAs (sncRNAs). Both epigenetic mechanisms targeted gene networks involved in embryonic development, neurodevelopment, growth, and metabolic processes[79]. Consequently, age-related changes in the sperm epigenome were not random accumulations of epimutations and might have been linked to autism spectrum disorders[9]. By analyzing data from the Swiss National Autism Registry, researchers identified 883 autism cases among 1,075,588 infants born over a decade. Their meta-analysis revealed that after controlling for factors like advanced maternal age, the incidence of autism positively correlated with older paternal age. Offspring of fathers aged > 50 years have a 2.7-fold increased risk of autism, which is also 2.2 times higher than the autism prevalence in offspring of fathers aged < 29 years. Therefore, advanced paternal age is closely associated with an increased risk of autism in offspring[74].

A study conducted in Denmark revealed that fathers over the age of 45 posed a higher risk of their partners experiencing gestational hypertension, placental abruption, and placenta previa. Additionally, older fathers correlated with increased rates of stillbirth and preterm birth, indicating a link between paternal age and fetal development[80,81]. Further research showed that advanced paternal age elevated the likelihood of offspring developing physical and genetic disorders, including cancer, congenital achondroplasia, Apert syndrome, and Marfan syndrome[82−84]. Thus, advanced paternal age might negatively impact embryo and offspring development[85,86].

Influence of prolonged alcohol consumption by fathers on offspring

-

Paternal alcohol exposure significantly impacts the learning, memory, and motor skills of offspring[87,88]. The progeny displayed deficits in inhibition, active avoidance, and working memory[89]. Research showed that extended paternal drinking correlated with symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in offspring during adolescence or adulthood, marked by hyperactivity, diminished activity, and stable activity levels[90]. Additionally, paternal alcohol exposure altered baseline and alcohol-induced emotional behaviors, sometimes in a species-specific manner[91]. Offspring of C57/BL6J mice subjected to alcohol exhibited more pronounced depressive-like behaviors[92].

Long-term alcohol consumption by fathers led to various developmental anomalies in offspring, including alterations in organ weight, sex hormone levels, neurotransmitter activity, stress response systems, and neurotrophic factors. The brains, thymuses, and adrenal glands of offspring weighed more, while spleen weight decreased[93]. Alcohol exposure reduced sperm count, circulating testosterone levels, and overall fertility in rodent models[94]. Male offspring from alcohol-exposed animals showed heightened expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the ventral tegmental area, whereas protein levels in the prefrontal cortex and olfactory bulb were diminished, along with nerve growth factor (NGF) protein levels. These alterations persisted in the cerebral cortex and ventral tegmental area of the offspring, correlating with reduced sensitivity to alcohol-induced anxiolytic effects and lower alcohol consumption. During acute restraint stress, cortisol levels in the cortex of alcoholic males were either lower or showed no significant change. Paternal alcohol consumption increases the vulnerability of offspring to hearing loss and ocular infections, while also modifying DNA methylation and non-coding RNA levels of paternally imprinted and neurotrophic factor genes[95−97]. Consequently, in certain instances, alcohol-induced epigenomic alterations in sperm could yield enduring functional repercussions for male offspring[98].

Impact of detrimental habits such as smoking and betel nut chewing by fathers on their offspring

-

In addition to these unhealthy lifestyle choices, other detrimental habits exhibited by fathers are also compromising the health of their children. Yen et al.[99] highlighted that paternal betel quid chewing has a transgenerational effect on the likelihood of metabolic syndrome (MetS) in their descendants, rendering them more vulnerable to obesity and diabetes. Similarly, Northstone et al.[100] showed that males who engaged in smoking before puberty were more prone to fathering male offspring with an elevated body mass index (BMI). The sperm-mediated genetic or epigenetic mechanisms might have only affected testosterone-sensitive pathways, which could explain the gender limitation observed in the intergenerational link between fathers who smoked and their sons[101].

-

Research on human and animal subjects suggests that paternal lifestyle significantly impacts offspring health. Unhealthy paternal behaviors, including poor dietary practices and detrimental lifestyle choices, have been linked to alterations in children's metabolic health and increased susceptibility to disease through biological and epigenetic pathways. This article emphasizes the pivotal role of paternal behaviors and environmental exposures before conception in shaping the health of future generations. Enhancing paternal health and lifestyle not only improves fertility and pregnancy outcomes but also reduces complications during childbirth and significantly enhances offspring survival and long-term health prospects. Furthermore, these improvements may encourage more couples to pursue parenthood, potentially alleviating the current decline in birth rates. Therefore, based on existing research findings, it is recommended to implement intervention programs focusing on promoting paternal health and reducing harmful lifestyle practices to safeguard the health of future generations and support sustainable societal development.

Current research on paternal epigenetics faces several critical challenges that demand further investigation. These include uncovering the precise mechanisms through which paternal factors influence offspring health, examining the multi-generational transmission of epigenetic modifications, assessing the stability and longevity of these markers throughout the lifespan, and exploring sex-specific differences in their manifestation. While existing studies suggest that paternal nutrition, lifestyle choices, and environmental exposures can significantly impact offspring health by altering sperm epigenetic profiles, the underlying biological pathways remain inadequately understood. Furthermore, although most research has been conducted using animal models, the translation of these findings to human health and the mechanisms underlying observed sex-specific differences require more comprehensive exploration.

Additionally, the majority of studies focus on animal models, resulting in a lack of extensive population studies to confirm these findings. Translating epigenetic research outcomes into clinical practice and developing analytical methodologies to address the complexities posed by high-throughput sequencing represent critical areas of contemporary research. Addressing these challenges will enhance our understanding of the father's influence within the nexus of genetics and environment, illuminating its potential ramifications for the health and development of future generations. This progress will generate important evidence to inform and guide public health initiatives, ultimately contributing to improvements in paternal health and the well-being of the next generation.

This study was partially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant No. 2024JJ5286) and the Key Support Area Project of the National College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (Grant No. 202312652001).

-

The data used in this study were provided by public source and collected from previously published sources. Therefore, no ethics committee approval was required for this study.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Tian M, Li J; literatures collection: Zhang B, Xie Z, Yuan Y, Li X, He Y, Lin J, Chen Y, Dai J; draft manuscript preparation: Tian Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study. All data discussed are available in the referenced literature.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Zhihong Tian, Benjie Zhang

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Tian Z, Zhang B, Xie Z, Yuan Y, Li X, et al. 2025. From fathers to offspring: epigenetic impacts of diet and lifestyle on fetal development. Epigenetics Insights 18: e005 doi: 10.48130/epi-0025-0004

From fathers to offspring: epigenetic impacts of diet and lifestyle on fetal development

- Received: 06 November 2024

- Revised: 08 March 2025

- Accepted: 11 March 2025

- Published online: 30 April 2025

Abstract: Recent research highlights that adverse parental factors can profoundly affect fetal development and long-term health through epigenetic regulation. The concept of 'Paternal Origins of Health and Disease' (POHaD) shifts the focus toward the significance of paternal health in embryonic development, pregnancy, and offspring growth. Specifically, a father's lifestyle and dietary choices before conception can alter the epigenetic marks of sperm, thereby influencing gene expression in the child. Evidence from preclinical studies, particularly in animal models, demonstrates that paternal dietary patterns such as fasting, low-protein diets, and excessive intake of fats, sugars, and oils can impact pregnancy outcomes and metabolic processes in offspring. These alterations, mediated by epigenetic mechanisms, are associated with an increased risk of chronic diseases. This article comprehensively reviews findings from both preclinical and limited clinical studies, analyzing how paternal dietary and lifestyle factors shape epigenetic regulatory mechanisms and contribute to transgenerational health impacts. These insights underscore the need to optimize fathers' diets and lifestyles and provide important scientific evidence for the prevention and treatment of diseases originating from paternal influences on fetal health.

-

Key words:

- Paternal lifestyle /

- Epigenetics /

- Offspring health /

- Intergenerational inheritance