-

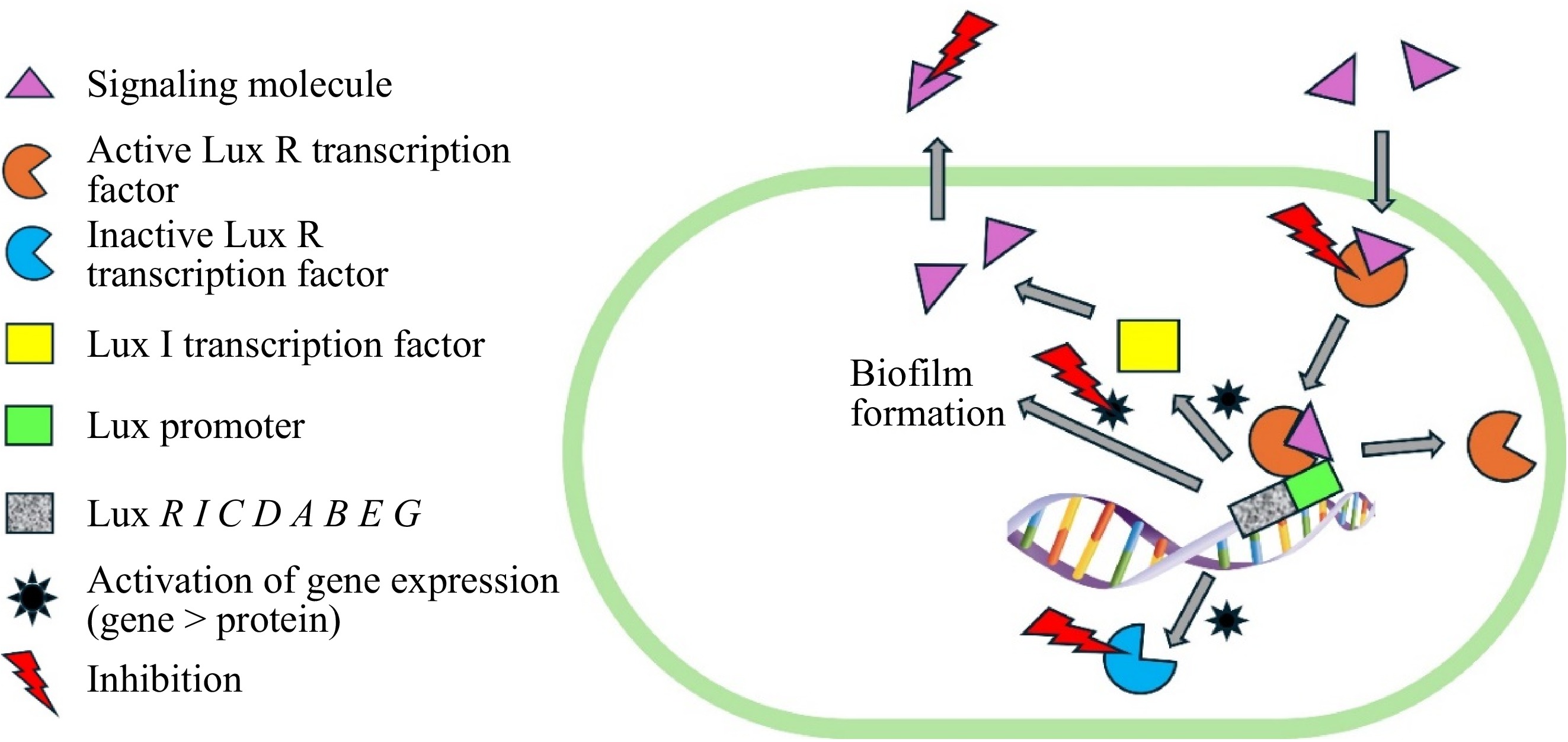

Microbial biofilms are structured communities of microorganisms encased in a self-produced extracellular matrix that adheres to both biotic and abiotic surfaces. The extracellular matrix of biofilms contains a diverse array of organic molecules including polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids, which contribute to the biofilm's structural integrity and functional properties[1−5]. These biofilms serve as a survival mechanism for microbes, resisting environmental stresses, including antimicrobial agents[6]. The presence of biofilms is associated with persistent infections such as those found in chronic wounds, medical implants, and respiratory systems. The resilient nature of biofilms poses a significant challenge in healthcare, as pathogens within these structures are up to 1,000 times more resistant to antibiotics than their planktonic counterparts[7]. The economic burden of biofilm-related infections is substantial, leading to increased hospital stays, more intensive treatments, and higher healthcare costs due to complications arising from these persistent infections. Biofilms can colonize various surfaces in hospitals, including catheters, surgical instruments, and other medical devices, increasing the risk of nosocomial (hospital-acquired) infections. Poor cleaning practices can exacerbate this issue. In food processing environments, biofilms can form on equipment such as pipes and tanks, leading to contamination of food products with pathogenic bacteria like Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella, and Escherichia coli. This poses serious health risks and can lead to foodborne illness outbreaks[8,9].

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are a group of Gram-positive, non-pathogenic bacteria commonly found in fermented foods. Recent research focuses on exploiting LAB as natural sources for enriching dairy foods with bioactive components, which may provide anti-hypertensive, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, and other health-promoting effects[10]. The growing consumer demand for natural, health-oriented foods has increased interest in utilizing LAB to develop functional dairy products. LAB play a pivotal role in shaping the gut microbiome, enhancing human health through their probiotic effects and bioactive metabolite production. LAB exhibit antimicrobial activity through mechanisms like bacteriocin production, organic acid secretion, and competitive exclusion which helps maintain gut microbiota diversity and balance, reducing dysbiosis[11,12]. The synergistic effects of LAB on gut health not only prevent infections but also boost immune responses and facilitate the production of essential nutrients. Additionally, LAB play a critical role in food preservation and safety[13]. Their fermentative activity inhibits spoilage microorganisms by lowering pH and producing antimicrobial compounds. This makes LAB crucial in extending the shelf life of fermented foods like yogurt, kimchi, and pickles. The specific mechanisms by which cell-free supernatant (CFS) of LAB disrupts biofilm architecture remain insufficiently understood. Therefore, this review aims to explore existing research on the antibiofilm efficacy of LAB, with a focus on the roles of CFS metabolites in preventing and disrupting biofilms.

-

LAB is well-known for their probiotic properties and antimicrobial activities, including their ability to inhibit biofilm formation by various pathogens. They can produce various substances that interfere with biofilm development, offering potential applications in food safety and medical settings. LAB produce a range of antimicrobial substances, such as bacteriocins, organic acids, and hydrogen peroxide. These compounds can inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria and disrupt biofilm formation. For example, bacteriocins produced by LAB can target specific pathogens by forming pores in their membranes, leading to cell lysis and preventing biofilm maturation[14]. LAB can outcompete pathogenic bacteria for adhesion sites on surfaces, thereby reducing the likelihood of biofilm formation. This competitive exclusion is crucial in environments like food processing facilities, where contamination risks are high. Furthermore, LAB can enhance the host's immune response, promoting the clearance of pathogens and their biofilms through the stimulation of immune cells and the production of signalling molecules that enhance phagocytosis[15]. Previous work demonstrating the antibiofilm efficacy of LAB are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Antibiofilm efficacy of LAB against pathogenic bacteria.

LAB species Antibiofilm activities Identified bioactive compounds Ref. Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus rhamnosus L. plantarum, L. rhamnosus and their CFS exhibit antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity against E. coli, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Proteus mirabilis. − [16] Lactobacillus plantarum and Bifidobacterium bifidum Strong inhibitory action against multi-drug resistant E. coli. Hydroxyacetone, 3-Hydroxybutyric acid, and Oxime-methoxy-phenyl [17] LAB strains isolated from the healthy human volunteers Inhibit the growth and biofilm formation by E. coli (ATCC 35218) and S. aureus (ATCC 25923) DL-3 phenyllactic acid, DL-p-hydroxyphenyllactic acid, and succinic acid [18] Lentilactobacillus kefiri LK1 and Enterococcus faecium EFM2 Exhibit anti-microbial and anti-biofilm activities by modulating hydrophobicity, auto-aggregation, and exopolysaccharide (EPS) production phenotypes and genotypes of bovine mastitis pathogens − [19] Lactococcus lactis NJ414 The cell-free supernatant (CFS) of the strain demonstrates effectiveness in inhibiting and eradicating biofilm formation by L. monocytogenes, with respective rates of 43.40% ± 0.58% and 38.90% ± 0.46%. − [20] Pediococcus pentosaceus and Enterococcus faecium All LAB develop biofilms to prevent biofilm formations of all tested pathogens through the co-aggregation process. Organic acids, diacetyl, hydrogen peroxide, ethanol, reuterin, and bacteriocins. [11] Lactobacillus helveticus CFS of Lactobacillus prevents the attachment between K. pneumoniae cells and reduced the cell viability of K. pneumoniae. − [21] Lactobacillus plantarum (7), Lactobacillus helveticus (3), Pediococcus acidilactici (1), and Enterococcus faecium (1) species Exhibit antibiofilm activities against S. aureus CMCC26003 and/or E. coli CVCC230. − [22] Pediococcus pentosaceus FB2 and Lactobacillus brevis FF2 Inhibit biofilm formation of B. cereus ATCC14579 (MBIC50 = 28.16%) and S. salivarius B468 (MBIC50 = 42.28%). − [23] L. plantarum strains MiLAB393 and MiLAB14 Antifungal activities against Pichia anomala, Penicillium roqueforti, and Aspergillus fumigatus are observed. But no antibiofilm activities are studied. 3-hydroxydecanoic acid, 2-hydroxy-4-methylpentanoic acid, benzoic acid, catechol, hydrocinnamic acid, salicylic acid, 3-phenyllactic acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, (trans, trans)-3,4-dihydroxycyclohexane-1-carboxylic acid, p-hydrocoumaric acid, vanillic acid, azelaic acid, hydroferulic acid, p-coumaric acid, hydrocaffeic acid, ferulic acid, and caffeic acid. [24] -

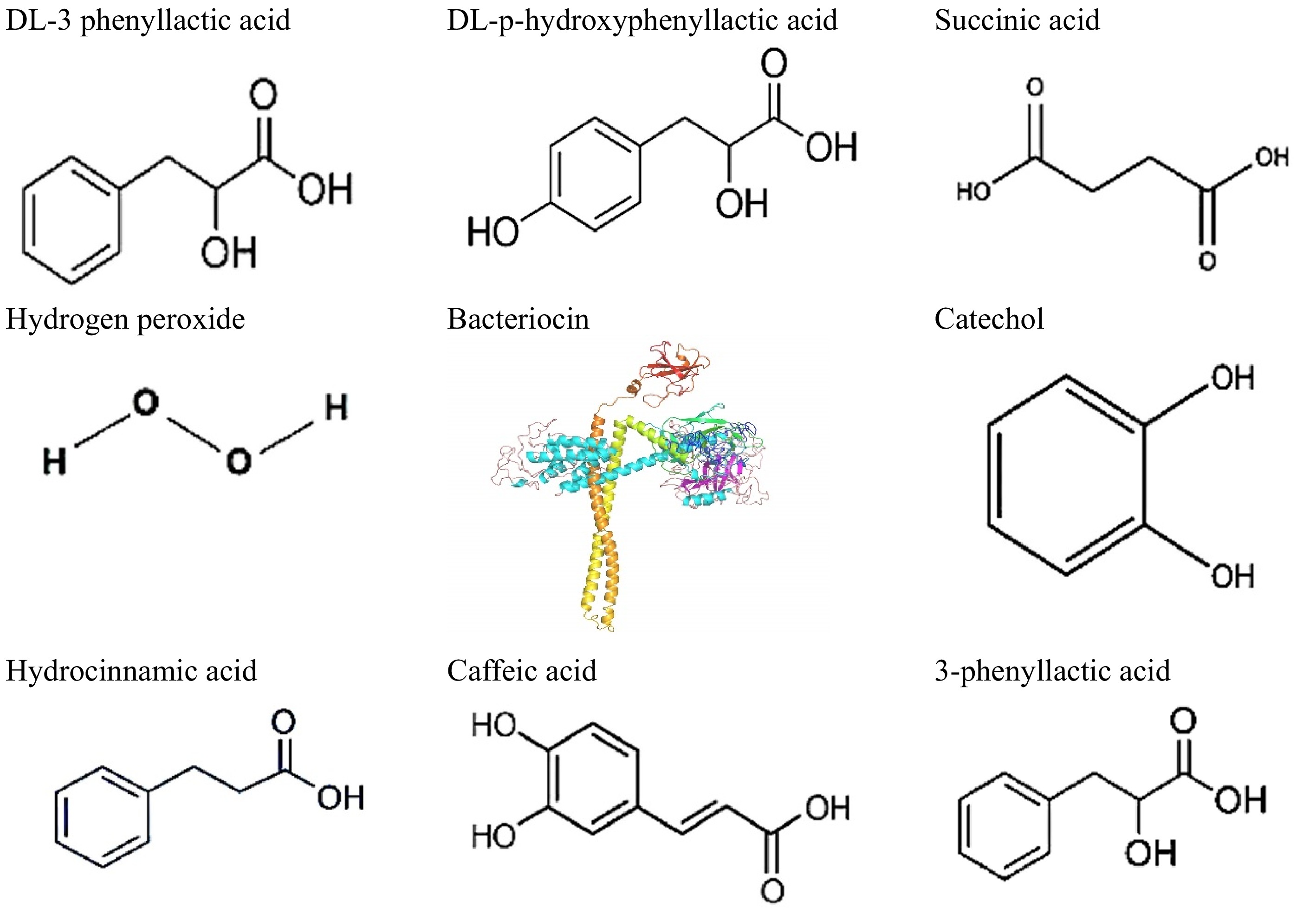

CFS are rich in various metabolites produced by microorganisms, including organic acids, proteins, and bioactive compounds, which can significantly influence plant growth and health. Several strategies can be employed to optimize the extraction of these metabolites from CFS. First, selecting the appropriate culture conditions, such as pH and incubation time, is crucial; for instance, supernatants produced at lower pH levels have shown enhanced effects on seed germination and growth due to higher concentrations of beneficial metabolites[25]. Additionally, employing efficient separation techniques like centrifugation at optimal speeds (e.g., 6,000 × g) ensure the removal of cellular debris while retaining soluble metabolites[26]. Further refinement can be achieved through liquid-liquid extraction methods that utilize solvents like methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), which offer improved separation characteristics compared to traditional solvents like chloroform[27]. Bioactive compounds produced by LAB are shown in Fig. 1.

The preparation of CFS from LAB involves cultivating LAB in a suitable growth medium, followed by centrifugation to remove bacterial cells, and subsequent filtration to ensure sterility. This process isolates bioactive metabolites which are responsible for their antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities. Multiple lines of work demonstrate that LAB-CFS effectively inhibits pathogenic biofilm, however, studies often lack standardization in LAB strains, culture conditions, and metabolite quantification, limiting reproducibility, and scalability. To address these gaps, future research should focus on optimizing culture parameters, validating bioactive components using advanced metabolomics, and conducting comprehensive in vivo studies to evaluate therapeutic and industrial applications.

-

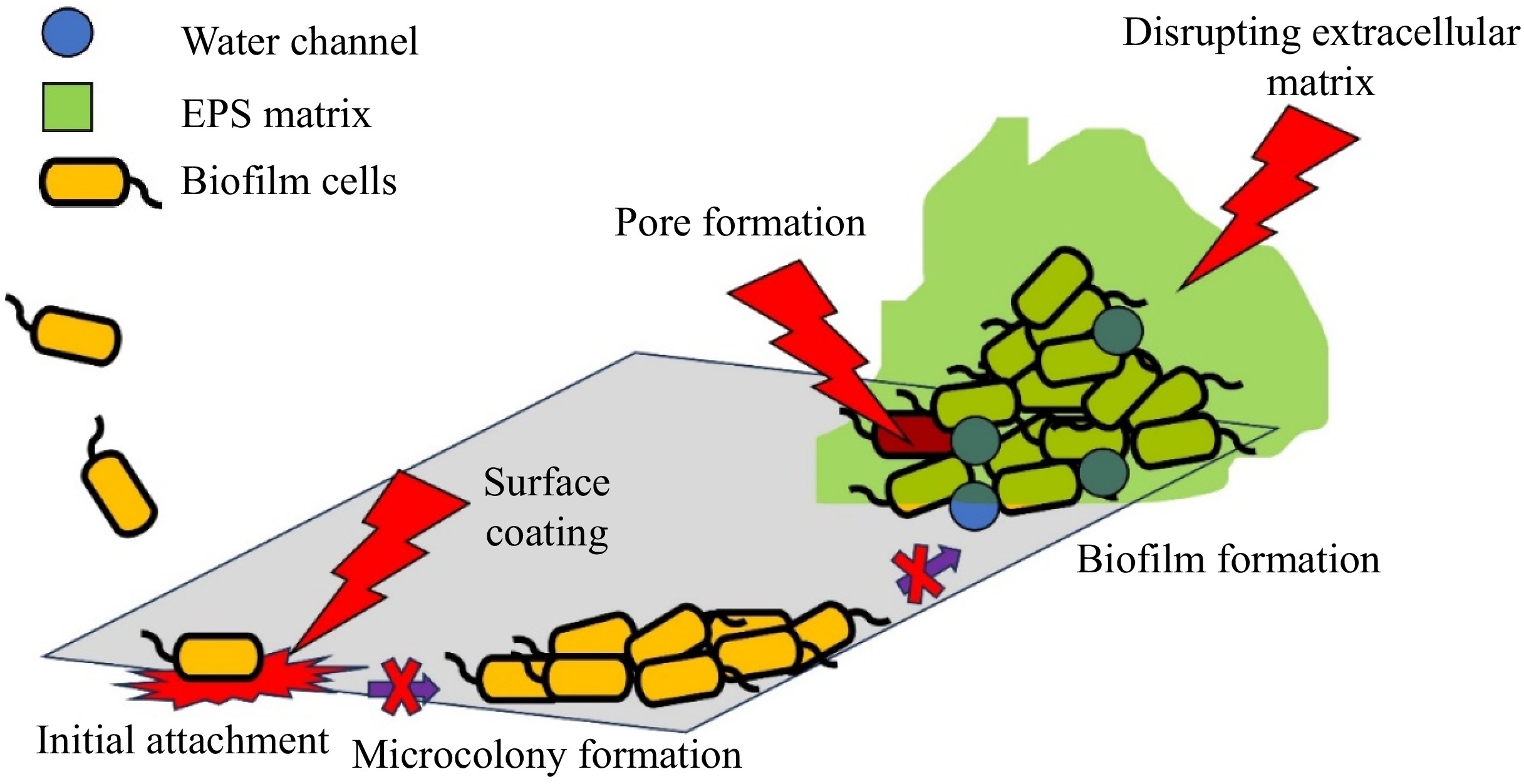

Experimental approaches such as proteomics, metabolomics, quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR), fluorescence microscopy, and field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) are instrumental in elucidating the antibiofilm mechanisms of LAB (Fig. 2). Each method provides unique insights into the molecular interactions and structural changes associated with biofilm inhibition.

Figure 2.

Experimental approaches commonly used to investigate antibiofilm mode of action of CFS of LAB.

Proteomics involves the large-scale study of proteins, particularly their functions and structures. In the context of LAB, proteomic analysis can identify specific proteins involved in the production of antibiofilm compounds, such as bacteriocins or enzymes that degrade biofilm matrices. By comparing the protein expression profiles of LAB-treated biofilm vs non-treated biofilm, researchers can pinpoint key proteins influenced by the antibiofilm activity of LAB. This information can help in understanding how LAB interacts with pathogenic bacteria at a molecular level, potentially leading to the development of targeted therapies against biofilms. In 2020, Wang et al.[28] demonstrated that treatment with Lactobacillus plantarum caused differential expression of proteins associated with chemotaxis, flagellar assembly, and two-component system in Bacillus licheniformis biofilm.

Metabolomics complements proteomic studies by focusing on the small molecules produced by LAB. This approach allows for the identification and quantification of metabolites such as organic acids, hydrogen peroxide, and phenolic compounds that exhibit antibiofilm properties. For instance, metabolomic profiling can reveal how variations in metabolite production correlate with changes in biofilm formation or disruption. Understanding these metabolic pathways can inform strategies to enhance the antibiofilm efficacy of LAB through fermentation optimization or genetic engineering. Based on metabolomic studies, Mao et al.[29] revealed that treatment with CFS of LAB isolated from the milk sample of bovine mastitis altered important metabolic pathways in S. aureus biofilm such as amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism.

RT-qPCR is a powerful tool for assessing gene expression levels related to biofilm formation and inhibition. By quantifying mRNA levels of genes associated with biofilm development in both LAB and target pathogens, researchers can determine how LAB influence the expression of virulence factors in biofilm-forming bacteria. This method provides insights into the regulatory mechanisms by which LAB exert their antibiofilm effects, allowing for a deeper understanding of the interaction dynamics between beneficial and pathogenic microorganisms. Based on RT-qPCR experiment, Mao et al.[29] demonstrated that the expression levels of clfA, fnbA, icaD, icaA, and clfB genes of S. aureus decreased after LAB-CFS treatment when compared with the control group.

Fluorescence microscopy enables visualization of bacterial cells and biofilms real-time. By employing fluorescent dyes that specifically stain live or dead cells, researchers can observe changes in biofilm structure and viability upon treatment with LAB metabolites. This technique is particularly useful for assessing how LAB affects biofilm architecture, such as altering cell density or disrupting extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrices. The ability to visualize these changes enhances our understanding of how LAB can effectively target established biofilms.

FESEM provides high-resolution images of biofilms, allowing researchers to examine their morphology and structural integrity at a nanoscale level. This imaging technique can reveal detailed information about how LAB disrupts biofilms, such as through physical degradation or changes to cell adhesion properties. By comparing untreated and LAB-treated biofilms, FESEM helps illustrate the effectiveness of LAB in reducing biofilm thickness and altering cell arrangement within the matrix. Structural deformation and loss of membrane integrity of biofilm cells following treatment with bacteriocin of LAB has been previously reported[30].

-

LAB produces diverse metabolites with significant antibiofilm activity, targeting microbial adhesion and biofilm formation. These metabolites synergistically enhance LAB's role as biopreservatives and therapeutic agents against biofilm-related infections.

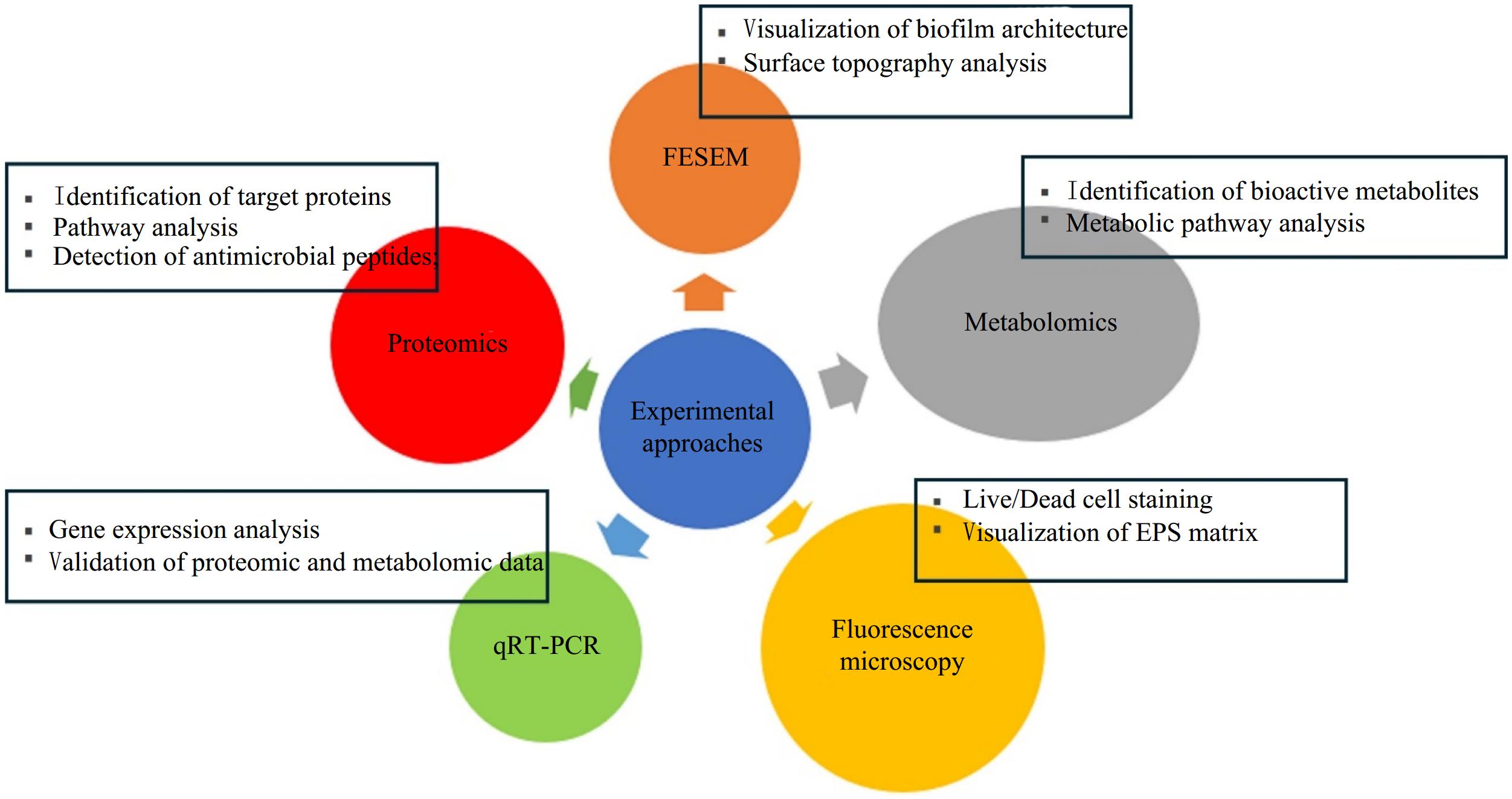

Lactic acid is an organic compound that consists of three carbon atoms, six hydrogen atoms, and three oxygen atoms, making it a hydroxycarboxylic acid. According to Kiymaci et al.[31], lactic acid had an inhibitory effect on short-chain HSL production and swarming-swimming-twitching motility, and biofilm production of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates that are regulated by the quorum sensing system. In general, quorum sensing is a cell-density-dependent communication mechanism that regulates gene expression in microbial populations, playing a pivotal role in biofilm formation. The inhibition of quorum sensing mechanisms is summarized in Fig. 3.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of biofilm formation in pathogenic bacteria via interference of quorum sensing mechanisms.

Bacteriocins are ribosomally synthesized antimicrobial peptides produced by LAB that target specific bacterial strains. They can inhibit the growth of closely related species and have shown effectiveness against biofilm-forming pathogens. Bacteriocins disrupt the integrity of bacterial membranes and can also interfere with the production of extracellular polysaccharides, which are essential components of the biofilm matrix[14]. This dual action not only prevents new biofilm formation but also aids in dispersing existing biofilms. The antibiofilm mode of action of bacteriocins is summarized in Fig. 4.

DL-3 phenyllactic acid is an organic acid produced by LAB that has been shown to possess antimicrobial properties. It interferes with bacterial cell membrane integrity, leading to cell lysis and reduced biofilm formation. Studies indicate that it can inhibit the growth of biofilm-forming pathogens such as S. aureus[32], making it a potent candidate for controlling biofilm-related infections.

Hydrogen peroxide is a well-known antimicrobial agent produced by some LAB strains. It exhibits strong oxidative properties that can damage cellular components of bacteria, leading to cell death. Its antimicrobial action is believed to involve the Fenton reaction, generating free radicals that oxidize DNA, proteins, and membrane lipids[33].

Catechol, a phenolic compound, has been recognized for its ability to inhibit biofilm formation by interfering with bacterial adhesion processes. Its structure allows it to bind to bacterial surfaces, thus preventing the initial attachment necessary for biofilm development. Vishakha et al.[34] reported that catechol impeded biofilm formation and virulence factors in Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae by inducing oxidative stress and targeting cell membranes.

Caffeic acid, another phenolic compound, exhibits both antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. It has been shown that caffeic acid and its derivatives exhibit could interfere with bacterial adhesion properties and inhibit α-hemolysin production in S. aureus[35]. Its antibiofilm mode of action also involves disrupting cell membrane stability and metabolic activity[35]. Other antibiofilm modes of action of LAB are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Antibiofilm mode of action of LAB species.

LAB species Antibiofilm mode of action Ref. LAB isolated from the milk sample of bovine mastitis. Inhibits the physiological traits of the S. aureus biofilm, including hydrophobicity, motility, eDNA, and PIA associated to the biofilm. Important metabolic pathways such amino acids and carbohydrates metabolism are among the most noticeably altered metabolic pathways.The expression levels of biofilm-related genes clfA, fnbA, icaD, icaA, and clfB of S. aureus biofilm decreases after LAB-CFS treatment when compared with the control group. [29] Lactococcus lactis strain CH3 SEM shows evidence of structural deformation and loss of membrane integrity of bacterial cells treated with bacteriocin. [36] Lactobacullus paracasei L2 and L20 strains LAB has anti-QS activities in different concentrations. [37] Lactobacillus brevis L. brevis KCCM 202399 CFS inhibits the bacterial adhesion of S. mutans KCTC 5458 by decreasing auto-aggregation, cell surface hydrophobicity, and EPS production (45.91%, 40.51%, and 67.44%, respectively). [32] Pediococcus pentosaceus and Enterococcus faecium All LAB could develop biofilms to prevent biofilm formations of all tested pathogens through the co-aggregation process. [11] Lactobacillus rhamnosus and

L. paracaseiBoth live and heat-killed LAB strains, particularly L. rhamnosus and L. paracasei, demonstrate the ability to interfere with S. mutans and S. oralis biofilm development through competition and displacement mechanisms. [38] Overall, the antibiofilm mechanism of CFS from LAB involves the secretion of various bioactive metabolites that disrupt biofilm formation and maturation. These compounds inhibit bacterial adhesion, quorum sensing, and extracellular polymeric substance production. Research has demonstrated significant antibiofilm activity of LAB-CFS against various biofilm-forming pathogens, however, much of the research is constrained to in vitro studies, with limited exploration of the underlying molecular pathways, variations in efficacy among different LAB strains, and the impact of environmental factors. To address these gaps, future studies should prioritize in vivo experiments, molecular-level investigations of antibiofilm activity, and strain-specific standardization of CFS production for therapeutic and industrial applications.

-

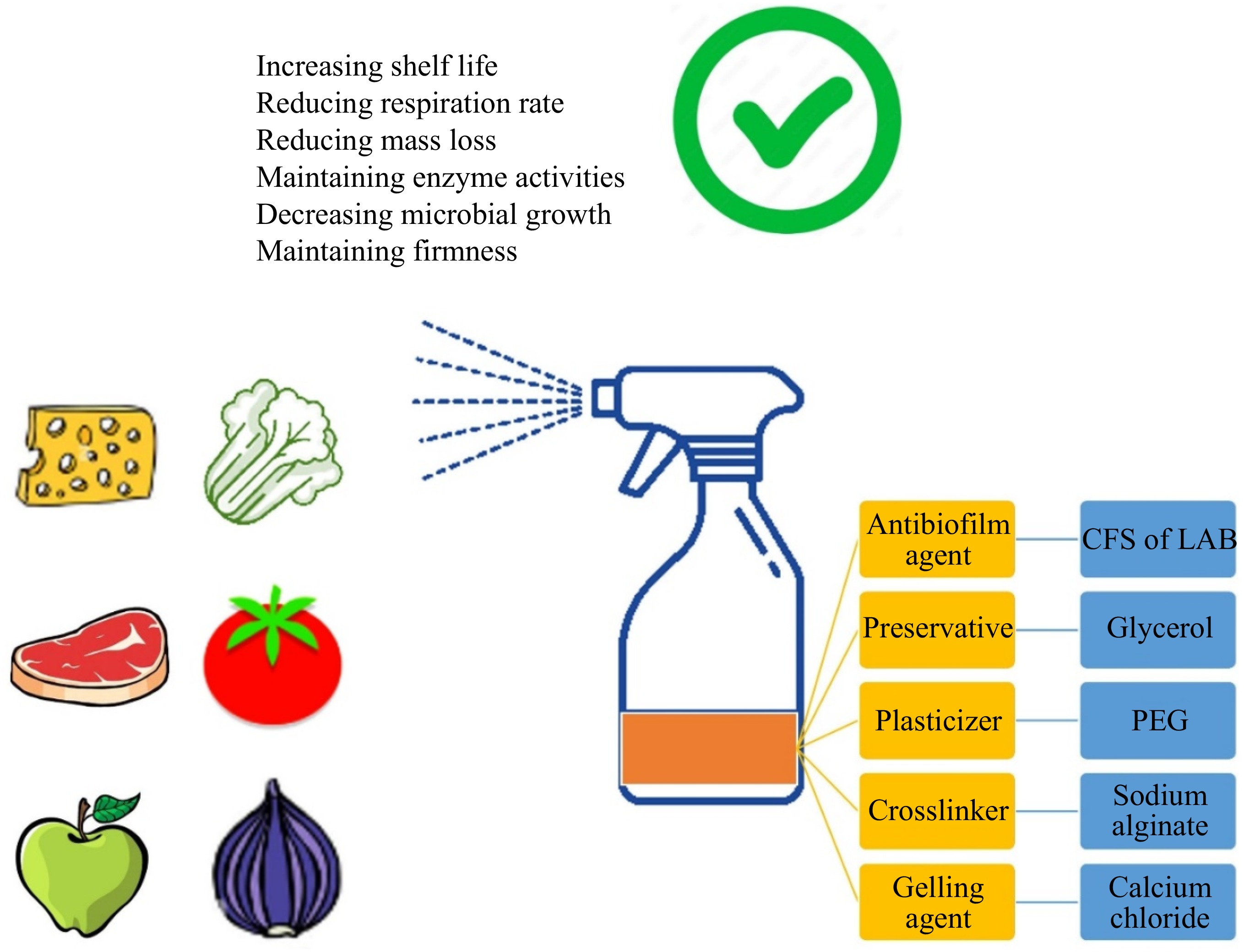

Edible coatings are thin layers applied directly to the surfaces of food products, particularly fruits (such as apples, oranges, lemons, strawberries, grapes, tomatoes, and mangoes) and vegetables (such as cucumbers, carrots, broccoli, and lettuce), to enhance their quality and extend shelf life (Fig. 5). These coatings serve as semipermeable barriers that regulate gas and moisture exchange, thereby reducing spoilage and degradation. They are made from natural, biodegradable materials, making them an environmentally friendly alternative to synthetic packaging.

Figure 5.

LAB-based edible coating for biofilm control. CFS: cell-free supernatant; LAB: lactic acid bacteria; PEG: polyethylene glycol.

Edible coatings can be categorized based on their composition[39]. Polysaccharide-based coatings include materials like alginate, pectin, and starch. They are effective in reducing respiration rates and moisture loss in fruits and vegetables. Protein-based coatings are derived from sources like whey, soy, and gelatin, these coatings provide good gas barrier properties but may have limitations in moisture retention. Lipid-based coatings comprise substances such as beeswax and carnauba wax, lipid coatings are effective at preventing moisture loss but may not offer significant barrier properties against gases. Edible coatings significantly prolong the shelf life of fresh produce by slowing down respiration and delaying ripening processes[40]. Some coatings can be enriched with bioactive compounds such as vitamins and antioxidants, contributing to the nutritional value of the coated food[41].

The application of edible coatings can be performed through various methods. In immersion processes, the food is submerged in a coating solution, allowing for even coverage[42]. This method is cost-effective and commonly used in commercial settings. On the other hand, spraying and brushing are often used for smaller batches or specific applications where precision is needed[42]. Immersion, or dipping, involves submerging food products in a coating solution to achieve even and thorough coverage. This method is highly cost-effective and scalable, making it ideal for commercial applications involving large volumes of products. The simplicity of the process ensures consistent coating, even on irregularly shaped items like fruits and vegetables. However, immersion can lead to higher material wastage due to solution carryover and contamination risks in shared baths. Moreover, the method may not be suitable for products with fragile surfaces as prolonged exposure can cause damage. Spraying offers precision and control, making it suitable for small batches or specialized applications. It minimizes material wastage compared to immersion and is often used for delicate or pre-packaged products. The process can also be automated for efficiency. However, the method requires specialized equipment and is less effective in achieving uniform coverage on highly irregular surfaces. Additionally, the fine mist generated during spraying may pose inhalation risks to operators without proper precautions. Brushing allows for highly controlled application, making it suitable for artisan or small-scale production. This method ensures minimal material wastage and can be applied to targeted areas. However, brushing is labour-intensive and impractical for large-scale operations. It may also result in uneven coating, especially for irregularly shaped or textured products. Overall, immersion is preferred for large-scale operations, while spraying and brushing are better suited for precision and small-scale applications.

-

To formulate edible coatings as a spray liquid, the coating material, typically a biopolymer such as polysaccharides, proteins, or lipids, is dissolved or dispersed in a solvent[43], often water, with the addition of emulsifiers or plasticizers like glycerol for stability and flexibility. The formulation should be adjusted to a low viscosity[44], ensuring uniform application via a spraying mechanism. For thin films, the coating solution is cast onto a flat surface and dried under controlled conditions to form a cohesive layer. Essential additives like antimicrobial agents or antioxidants can enhance functionality. The oil-in-water (O/W) emulsion systems are commonly preferred for both methods due to their thermodynamic stability and ability to incorporate hydrophobic compounds effectively. O/W emulsions as edible coatings have been shown to reduce weight loss, maintain firmness, and slow down decay in fruits like tomatoes[45]. The formulation of edible coatings using CFS of LAB is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Edible coatings formulated with CFS of LAB.

LAB species Coating material Efficacy Ref. Pediococcus pentosaceus 147 Chitosan Chitosan coatings plus CFS (5.72 ug/ml) of P. pentosaceus 147 inhibit the growth of L. monocytogenes during the storage of cheese contaminated after production. [46] Lacticaseibacillus paracasei TEP8, Lactiplantibacillus pentosus TEJ4 and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum TEP15 Chitosan The films with 75%, 50% and 25% CFS from the three strains exceed 50% inhibition. L. pentosus TEJ4 and L. plantarum TEP15 maintain high inhibition levels (> 79%) at low CFS concentrations. [47] Lactobacillus rhamnosus NRRL B-442 Whey protein Noticeable antimicrobial activity (about 3 mm) is observed against E. coli, L. monocytogenes, S. aureus, or S. typhimurium when 18 mg/ml of cell-free supernatant are added. [48] Lactobacillus paracasei Glycerol and starch as well as gelatin Edible coatings give better results than untreated fruits such as diminishing weight loss, decay percentage, higher ascorbic acid, lycopene, titratable acidity, total sugars and total soluble phenols concentration as well as lower bacterial load, T.S.S./T.A. than uncoated fruits. [49] Lactiplantibacillus plantarum A6 Exo-polysaccharide L. plantarum A6 remain viable both in the solution and on the surface of the fruit after coating, protecting the fruit against two of the three evaluated fungi (Fusarium sp. and Rhizopus stolonifer). The edible coating controls weight loss, maintained firmness, and slowed the respiration rate of cherry tomato; the other physicochemical properties and the appearance of the fruit are not negatively affected. [50] Lactococcus lactis L3A21M1 and Lc. garvieae SJM17 Alginate, maltodextrin and glycerol The application of coating with immobilized Lactococcus cells on cheeses reduces significantly (p < 0.05) the contamination by L. monocytogenes on surface and prevents the growth of mesophilic bacteria by the 6th and 8th day of storage at 4 °C. [51] Lacticaseibacillus paracasei ALAC-4 Chitosan CS-CFS films exhibit strong antifungal activities against molds and yeasts, especially C. albicans, and also have excellent mechanical properties. Additionally, FTIR spectroscopy indicates that hydrogen bonds between the CFS and CS formed, and there is a smooth surface, compact cross-section observed in SEM morphologies of CS-CFS films. [52] Lactobacillus gasseri Pea protein isolates and psyllium mucilage Cell-free supernatants (CFS, so-called postbiotics) and whole-cell postbiotics (WCP) of probiotics exhibit antioxidant and antibacterial activities and are significant sources of phenolic compounds. [53] Edible coatings formulated with CFS of LAB represent an innovative approach in food preservation, leveraging the antimicrobial properties of LAB-derived metabolites to inhibit spoilage and pathogenic microorganisms. Such coatings can create a physical barrier around fresh produce while actively protecting it through antimicrobial activity. Most research is limited to laboratory-scale applications, with challenges in scalability, standardization of CFS content, and long-term stability. Future studies should focus on optimizing production methods, conducting field trials, and assessing consumer acceptance to establish practical and commercially viable solutions for food preservation. This will bridge the gap between innovation and industrial application, ensuring sustainable and effective alternatives to synthetic preservatives.

-

Food quality encompasses the attributes that influence food safety, nutrition, taste, and shelf life. It plays a crucial role in food security by ensuring access to safe and nutritious food. Research highlights the potential of CFS of LAB in controlling foodborne pathogens[54−57]. However, current studies overlook real-world challenges like regulatory compliance, scalability, and consumer acceptance. Additionally, the variability in LAB strains and their bioactive metabolite profiles affects consistency and efficacy. To advance the application of LAB-CFS for food security, research should prioritize standardization of production processes, comprehensive field trials, and integration into sustainable food systems. Other challenges that remain in commercializing CFS products include optimizing growth media compatible with food sensory properties, ensuring CFS stability during storage, and addressing potential cytotoxicity concerns. Additionally, the fastidious nutritional requirements of LAB and strain-specific variations complicate the development of standardized production methods[58]. Further research is needed to overcome these limitations and fully realize the potential of CFS as a natural food preservative.

According to Elsser-Gravesen & Elsser-Gravesen[59], biopreservatives, including bacteriocins, fermentates, and bacteriophages, offers promising solutions for food producers facing challenges in developing stable products with minimal processing and reduced additives. Policy frameworks that promote the use of biopreservatives and education to build consumer trust are critical. For example, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) classifies many LAB strains as Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS), allowing their use in food products without extensive pre-market approval[60]. This facilitates the incorporation of LAB-based biopreservatives in various foods. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) maintains a Qualified Presumption of Safety (QPS) list, which includes several LAB strains[61]. Inclusion in this list simplifies the approval process for using these bacteria in food preservation. The Codex Alimentarius, developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO), endorses the use of beneficial microbes like LAB in food preservation, influencing national policies to adopt similar standards[62]. While many bacteriocins exhibit promising antibiofilm properties[63−67], pediocin PA-1/AcH from Pediococcus acidilactici remains the most commercially utilized in the food industry[66]. The other bacteriocins such as lacticin 3147, macedovicin, curvacin A, and reuterin, are still under research and have limited or no direct commercial applications currently[68−73].

-

Understanding the antibiofilm mechanism of bioactive compounds produced by LAB is crucial due to its broad applications in food preservation and safety. LAB-derived bioactive compounds, such as organic acids, bacteriocins, and exopolysaccharides, effectively inhibit biofilm formation by targeting multiple stages of biofilm development. These compounds disrupt bacterial adhesion, impair matrix production, and degrade established biofilms, ensuring the microbial integrity of food products is maintained. Utilizing CFS of LAB to formulate edible coatings offers a natural and sustainable method to prolong the shelf life of foods by inhibiting spoilage microbes and pathogens. Additionally, these coatings enhance food quality, maintain freshness, and reduce the reliance on synthetic preservatives. Such innovations in food technology aligns with consumer demand for safer and eco-friendly packaging solutions while supporting sustainability in food systems.

The authors would like to thank Universiti Teknologi MARA, Malaysia for providing research facilities.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, original draft preparation: Yahya MFZR; review and editing: Aazmi MS, Ismail MF. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this review as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yahya MFZR, Aazmi MS, Ismail MF. 2025. Antibiofilm potential of lactic acid bacteria: mechanism of cell-free supernatant, metabolite insights, and prospects for edible coating applications in food quality control. Food Materials Research 5: e006 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0025-0004

Antibiofilm potential of lactic acid bacteria: mechanism of cell-free supernatant, metabolite insights, and prospects for edible coating applications in food quality control

- Received: 04 December 2024

- Revised: 07 March 2025

- Accepted: 09 April 2025

- Published online: 22 May 2025

Abstract: Biofilms present significant challenges across health, industry, and food safety due to their resistance to conventional antimicrobial strategies. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) from the gut microbiome exhibit considerable potential as natural antibiofilm agents, largely through the bioactive compounds present in their cell-free supernatant (CFS). LAB CFS contains a diverse array of metabolites, such as organic acids, bacteriocins, and biosurfactants, which demonstrate bacteriostatic and bactericidal effects against various biofilm-forming pathogens. However, the specific mechanisms by which LAB CFS disrupts biofilm architecture remain insufficiently understood. This review aims to explore existing research on the antibiofilm efficacy of LAB, with a focus on the roles of CFS metabolites in preventing and disrupting biofilms. Current evidence suggests that LAB metabolites interfere with biofilm formation by targeting bacterial quorum sensing, modifying surface hydrophobicity, and degrading extracellular polymeric substances; further investigation is needed to fully elucidate these pathways. The mechanisms through which LAB-derived compounds impact biofilm integrity, structure, and function are particularly relevant in food preservation and safety. Emerging directions in LAB research also include the development of edible coatings that incorporate LAB CFS for enhanced food quality control. Such edible coatings show the potential to inhibit biofilm-associated spoilage organisms on food surfaces, extending shelf life, and enhancing safety. This work contributes to the field by providing a comprehensive overview of LAB's antibiofilm properties, clarifying metabolite-specific mechanisms, and proposing innovative applications for food industry challenges. It also supports the development of sustainable, natural antimicrobial solutions that align with consumer demand and contribute to food security initiatives.

-

Key words:

- Antibiofilm /

- Lactic acid bacteria /

- Cell-free supernatant /

- Edible coating /

- Food quality