-

Actinidia arguta, also known as soft jujube, is a large deciduous vine in the kiwifruit family[1]. Characterized by its smooth, hairless skin, and relatively small size, weighing approximately 5–10 g, it is considerably smaller than commercially available kiwifruit. Its skin transitions from bright to light green or pink upon maturation[2], enclosing aromatic and flavorful berries that are either spherical or ellipsoidal in shape[3]. Notably, these fruits can be consumed unpeeled[4]. Cultivated extensively across regions of Northeast Asia, Northern Europe, North America, and other high-latitude countries[5], Actinidia arguta has emerged as a commercially valuable berry, distinguished by its rich composition of multiple vitamins, amino acids, minerals, and bioactive substances[6]. It serves as an excellent source of dietary fiber, contributes to digestive health, and plays a vital role in the prevention of metabolic syndrome, gastrointestinal tumors, and cardiovascular diseases[7]. However, Actinidia arguta's climacteric nature results in limited post-harvest shelf life, with commercially ripe fruit rapidly softening within 5 d at 20 °C[2]. The susceptibility of these fruit to mechanical injuries and decay during harvesting, post-harvest handling, and transportation remarkably diminishes their market value.

Post-harvest water loss occurs naturally during fruit transpiration and it is a major challenge as it reduces fruit quality, shelf life, and market value[8]. The degree of water loss is related to the freshness of horticultural products, and excessive water loss can seriously affect the market value of products and consumer acceptance[9,10]. Excessive water loss can lead to the appearance of fruit and vegetable damage, while moderate water loss is beneficial for fruit and vegetable storage. In addition, fruit and vegetables in the post-harvest preservation process will occur in many mechanical injuries, improper handling will cause serious losses, such as impact damage, vibration damage, extrusion damage, friction damage, puncture damage, and reloading damage. Vibration damage is one of the forms of cumulative fatigue induced by cyclic dynamic vibration and is highly susceptible to internal damage of fruit. Soleimani & Ahmadi[11] found that mechanical damage suffered by fruit during transportation was related to the vibration acceleration of the vehicle. Also, the experimental results showed that the upper layer was damaged faster and more severely compared to the lower layer of storage. Shahbazi et al.[12] demonstrated that watermelon suffered the highest rate of damage at frequencies of 7 and 13 Hz by demonstrating this in an experiment. Limited data are available on the effect of storage humidity on fresh fruit damage. Low medium humidity affects the susceptibility of fruit to mechanical injury[8]. Appropriate post-harvest water loss increases the solubility of vesicular solutes and improves sensitivity to external mechanical forces. Studies reported that osmotically dehydrated strawberries were stable in vitamin C with little change in color after freezing. In addition to this, the extraction of flavonoids was rather increased in properly dehydrated grape seeds[13]. In a previous study, our laboratory demonstrated that post-harvest light water loss can prolong the storage longevity of Actinidia arguta while simultaneously decreasing its susceptibility to mechanical injury by accelerating fruit hardness[14]. Analogous findings in citrus fruit indicate that light water loss enhances stress resistance, thereby reducing losses attributed to mechanical injuries and diseases[15]. Fruit softening characterizes the degradation of cell wall structure, which includes a range of polysaccharide components, such as pectin and cellulose[16]. They play a crucial role in maintaining structural integrity and enhancing intercellular adhesion. Cell wall degradation affects the brittleness and hardness of fruit during ripening, and aging[17,18] and decreased the activities of PG, PME, PL, cellulase, and β-glu enzymes[19].

Despite the potential benefits of light water loss in prolonging storage life and mitigating post-harvest mechanical damage, research in this domain remains scarce. Therefore, it aims to elucidate the impact of light water loss on the cell wall metabolism of Actinidia arguta under simulated post-harvest mechanical stress. This provides a theoretical basis and reference value for the development of new storage and transport preservation technologies.

-

The study utilized 'Longcheng II' Actinidia arguta (the maturity index was based on average total harvest hardness of 8.5 ± 0.05 and fruit size of 20 ± 0.5 g), harvested from a well-managed orchard in Kuandian County, Dandong City, Liaoning Province, China. Fruit were harvested and immediately transported to the laboratory in foam boxes and ice packs. Fruit of uniform size and maturity, free from any diseases, pests, or physical damage were selected for the experiments.

Water loss treatment

-

A total of 240 Actinidia arguta fruits free of pests and diseases were selected for this experiment. These were evenly divided into two groups: the control group was stored in a sealed bag, whereas the other group was placed on a test bench covered with gauze to undergo 'water loss' treatment. A fan was activated to facilitate the process, with laboratory conditions maintained at approximately 25 °C and humidity between 72% and 78%. The treatment duration was determined based on achieving a 4% water loss rate within 3 h, a criterion established from preliminary experiments and references[20].

Simulated transport vibration treatment

-

Both treated and untreated fruit were further divided into four groups (day 0 is the fruit without treatment), each containing 60 fruit, and placed in plastic foam boxes measuring 280 mm × 220 mm × 120 mm. They were subjected to vibration using a simulated transport shaker to replicate transport conditions. Research has shown that the vibration frequency distribution of vehicles during transportation ranges between 2 and 5 Hz[21]. As such, we employed a vibration frequency of 120 r/min (2 Hz). Considering studies suggesting that strawberries experience increased damage and electrical conductivity[22] at vibration levels of 5 Hz for 150 s, vibration treatments of 5 and 10 min were selected. The treatment method is shown in Table 1. After the treatment, fruit were stored at a simulated room temperature of 25 ± 1 °C for 10 d, with phenotypic changes observed daily. Ten samples were selected from each group. The pulp of Actinidia arguta was rapidly frozen using liquid nitrogen and preserved at −80 °C for later analysis of quality and physiological parameters.

Table 1. Comparison table of treatment methods.

Processing code Control1 Control2 S1 S2 Treatment method Without losing water.

The simulated vibration

time is 5 minWithout losing water.

The simulated vibration

time is 10 minWater loss of 4%.

The simulated vibration

time is 5 minWater loss of 4%.

The simulated vibration

time is 10 minSensory quality

-

Appearance quality was assessed every 2 d using a photo box to capture and document changes. Fruit hardness was determined according to Yang et al.[23], employing a texture analyzer (Brookfield's CT3 10K mass spectrometer, USA) on the equatorial part of the fruit at two distinct points. The decay rate was calculated using a method slightly modified from Zhang et al.[24], categorizing fruit based on visible disease spots, swelling, and skin color changes into grades 0–4: Rot rate (%) = Σ Rot level × number of samples of this grade/Highest grade × Total number of samples × 100%.

Microstructural changes

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

-

For each treatment, fruit samples were taken, and the pulp was excised using a sterile scalpel to produce sections not exceeding 3 mm2. These sections were then fixed and stored at 4 °C before being dried using a vacuum freeze-dryer. Subsequently, using an ion-sputtering coater, the dry samples were labeled using a scanning electron microscope.

Transmission electron microscope (TEM)

-

Adapting the method by Taylor & Koohmaraie[25], Actinidia arguta fruit were divided into cuboids (1 mm × 1 mm × 3 mm) and rinsed in a phosphate buffer containing glutaraldehyde as a fixative, a process repeated three times. Following gradient elution and dehydration, the samples were embedded, sectioned at room temperature, and then analyzed using transmission electron microscopy.

Cell wall components

-

The quantification of both insoluble and soluble pectin followed the methodology proposed by Tang et al.[26], utilizing carbazole colorimetry for pectin content determination. The analysis of cellulose and alcohol-insoluble substances (AIS) within the fruit cell walls was conducted using specific assay kits, with results reported in mg/g.

Pectin-degrading enzyme activity

-

PG activity was assessed following Shi et al.[27], with activity expressed as the conversion rate of polygalacturonic acid to galacturonic acid at 37 °C, expressed in μg/h/g. PME activity determination was guided by the method of Ren et al.[28], using a 10 g/L pectin solution as the substrate, and was expressed as the mass of pectin methyl ester released by PME at 37 °C per h per g of sample (U/g). Pectinlyase (PL) activity was measured using a kit, with results also expressed as U/g.

Cellulose-degrading enzyme activity

-

Cellulase activity was determined by following the approach of Cao et al.[29]with some modifications. It involved quantifying the production of reducing sugars catalyzed by cellulase using a 10 g/L sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) solution as the substrate. The corresponding glucose content was determined from a standard curve based on the difference in absorbance between the experimental and control groups. Cellulase activity was expressed as the mass of CMC catalytically hydrolyzed to reducing sugar at 37 °C per g of sample per h (μg/h/g). β-Gal activity was determined with a slight modification of the method described by Zhao et al.[30]. Using p-nitrobenzene-β-D-galactoside pyranopyranoside as a substrate, 1 nmol p-nitrophenol production per g of tissue per h was defined as an enzyme activity unit. To determine β-Glu activity, we referred to the method described by Ji et al.[31].

Data analysis

-

Each experimental procedure was replicated three times. Excel was used for data processing, whereas Duncan's multiple range test (p < 0.05) in SPSS 24.0 was used for statistical analysis. Pearson's correlation test was applied for correlation assessments, and Origin 2021 software facilitated graphical representations of the data.

-

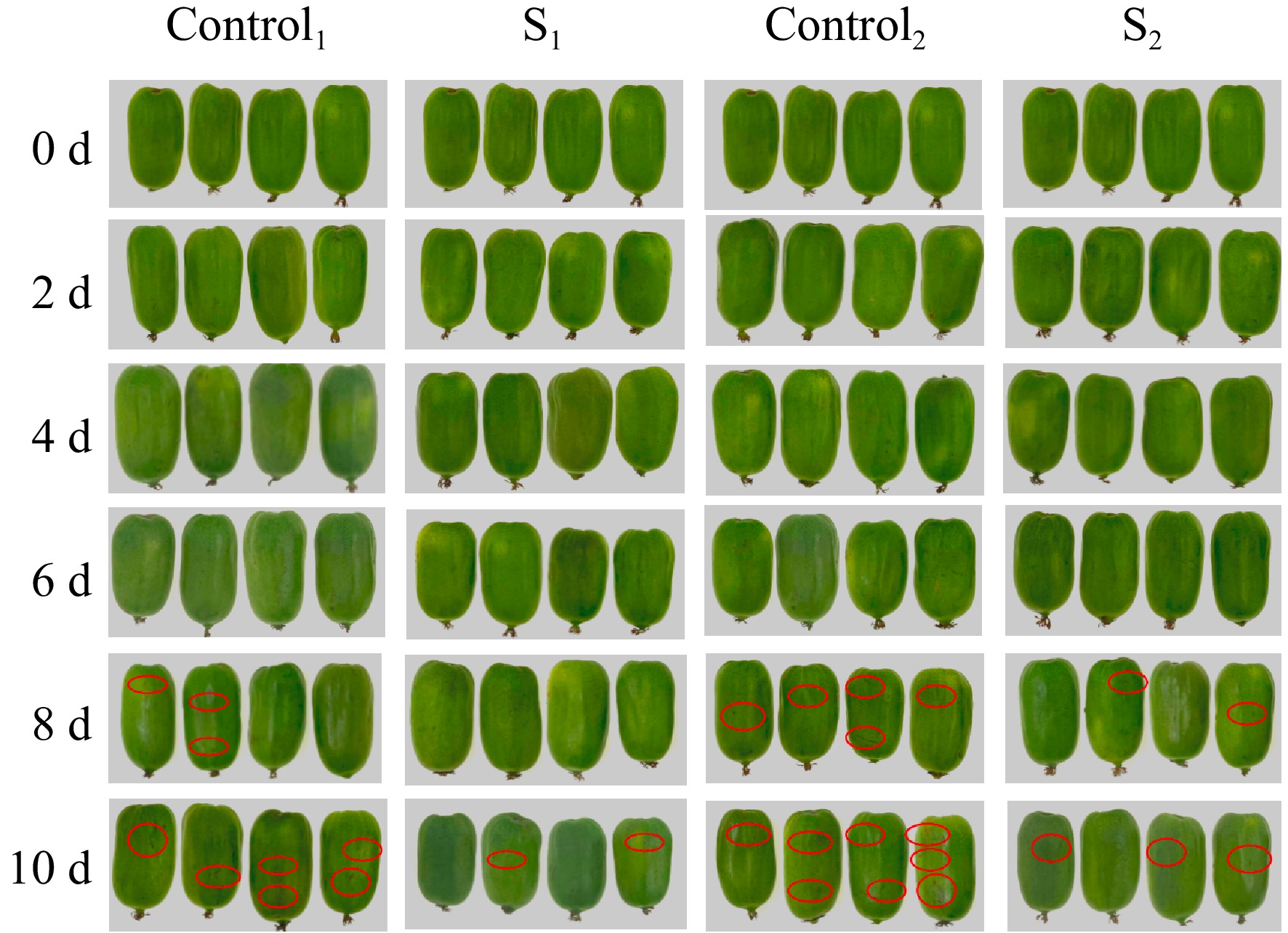

The effect of water loss on the sensory appearance of post-harvest Actinidia arguta is shown in Fig. 1. During storage, Actinidia arguta fruit from all treatments and the control showed no significant changes at first after vibration damage. Different degrees of browning were observed at 8–10 d. During the initial storage phase (2–4 d), no significant differences were observed in appearance across treatment groups. However, in the middle storage stage, Control1 and Control2 in the control group exhibited minor browning, which progressively intensified as storage duration increased, culminating in a complete loss of commercial value by day 10. Conversely, the appearance quality of Actinidia arguta in the treatment groups, S1 and S2, remained superior to that of Control1 and Control2 on day 10.

Changes in skin hardness and decay rate

-

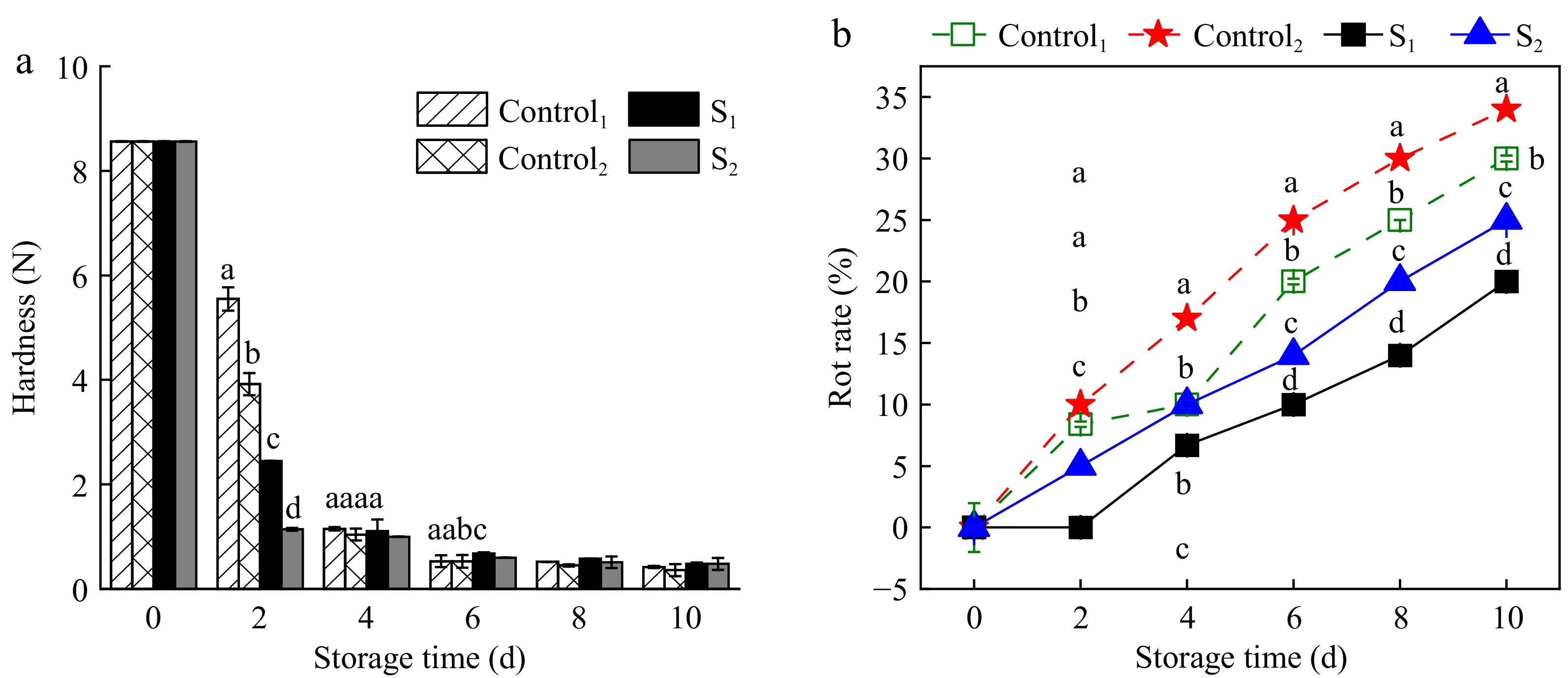

Figure 2a shows the effect of water loss treatment on the hardness of the skin during post-harvest storage, revealing a gradual decrease in hardness and subsequent softening over time. Figure 2b shows that the fruit decay rate increased gradually with prolonged storage (p < 0.05). After 2 d, Actinidia arguta in S1 of the treatment group did not rot, whereas initial signs of rot were evident in Control1, Control2, and S2. By day 10, the decay rates for Control1 and Control2 were 30% and 34%, in contrast to 20% and 25% for S1 and S2 within the treatment groups. The results showed that the water loss treatment was effective in delaying the increase in rotting rate due to soft vibration damage during storage compared to the control.

Figure 2.

Effect of water loss treatment on (a) hardness and (b) decay rate of Actinidia arguta. The mean values were compared using Duncan's multiple range test at a significance of p < 0.05.

Microstructure changes

SEM

-

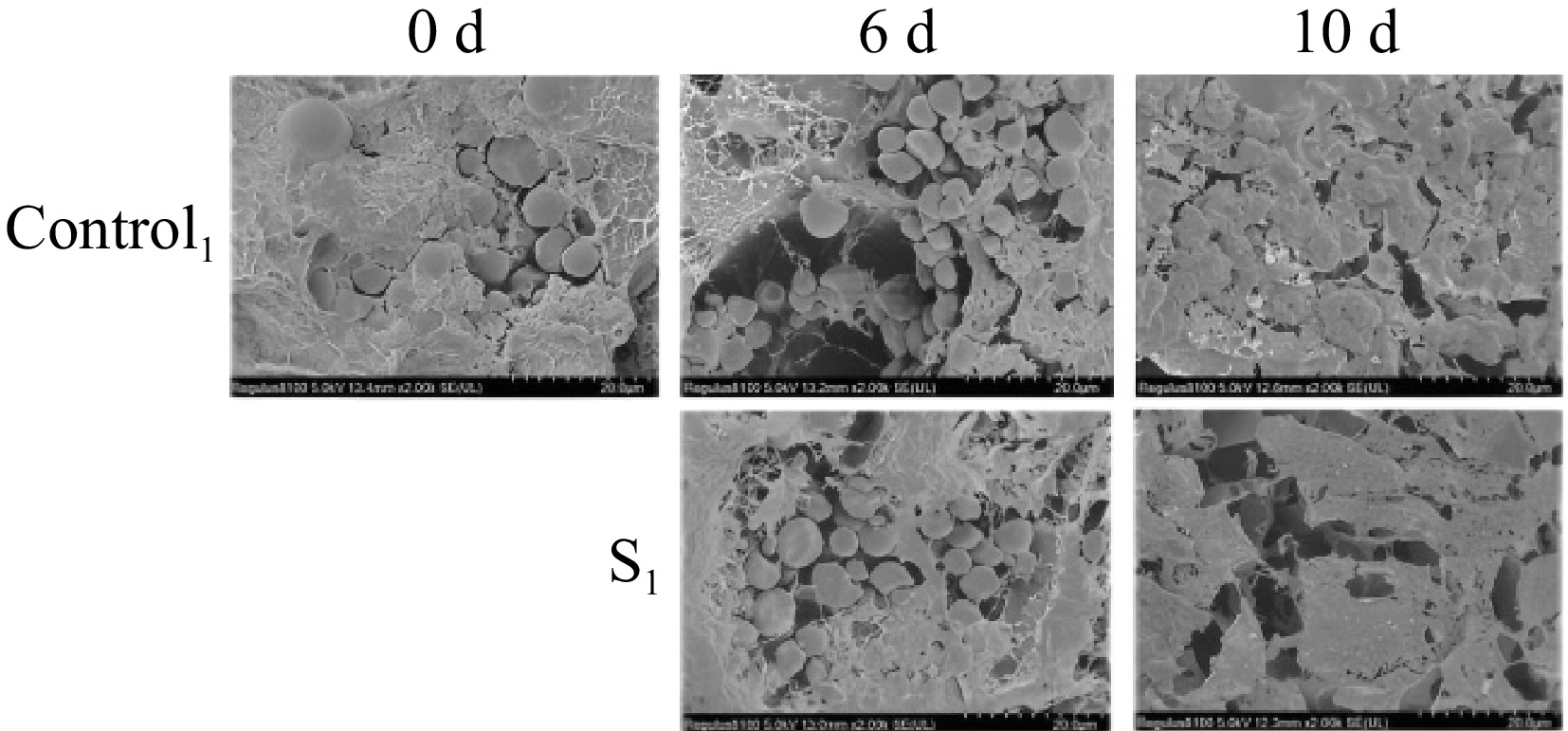

SEM imagery reveals the changes in fruit structure and morphology at 0, 6, and 10 d under control and light water loss conditions (Fig. 3). The evaluation of the SEM images of the Actinidia arguta fruit surface demonstrated the presence of the structure and morphology of water loss treated fruit were more intact than the control. The 0 d untreated Actinidia arguta fruit were smooth and flat, with normal cellular morphology and structure, clear distribution, and more starch grains. At 6 d of storage, the degradation of starch granules in the fruit began to digest and fragment, and hardness decreased. The tissue contour texture of the treated group was clearer and more densely distributed. On the contrary, the cell structure of the control group was collapsed and loose, with some degree of damage and severe softening. At 10 d of storage, the starch grains of the treatment group disappeared, became loose and porous, and the softening was more serious, while the cell deformation of the control group was completely destroyed and could not carry out metabolic activities. These observations indicate that light water loss can mitigate cell wall degradation rates, thus delaying the senescence and softening of Actinidia arguta fruit.

Figure 3.

Morphological observation and comparison of postharvest Actinidia arguta by water loss treatment under SEM in 0, 6, and 10 d control group and treatment group S1.

TEM

-

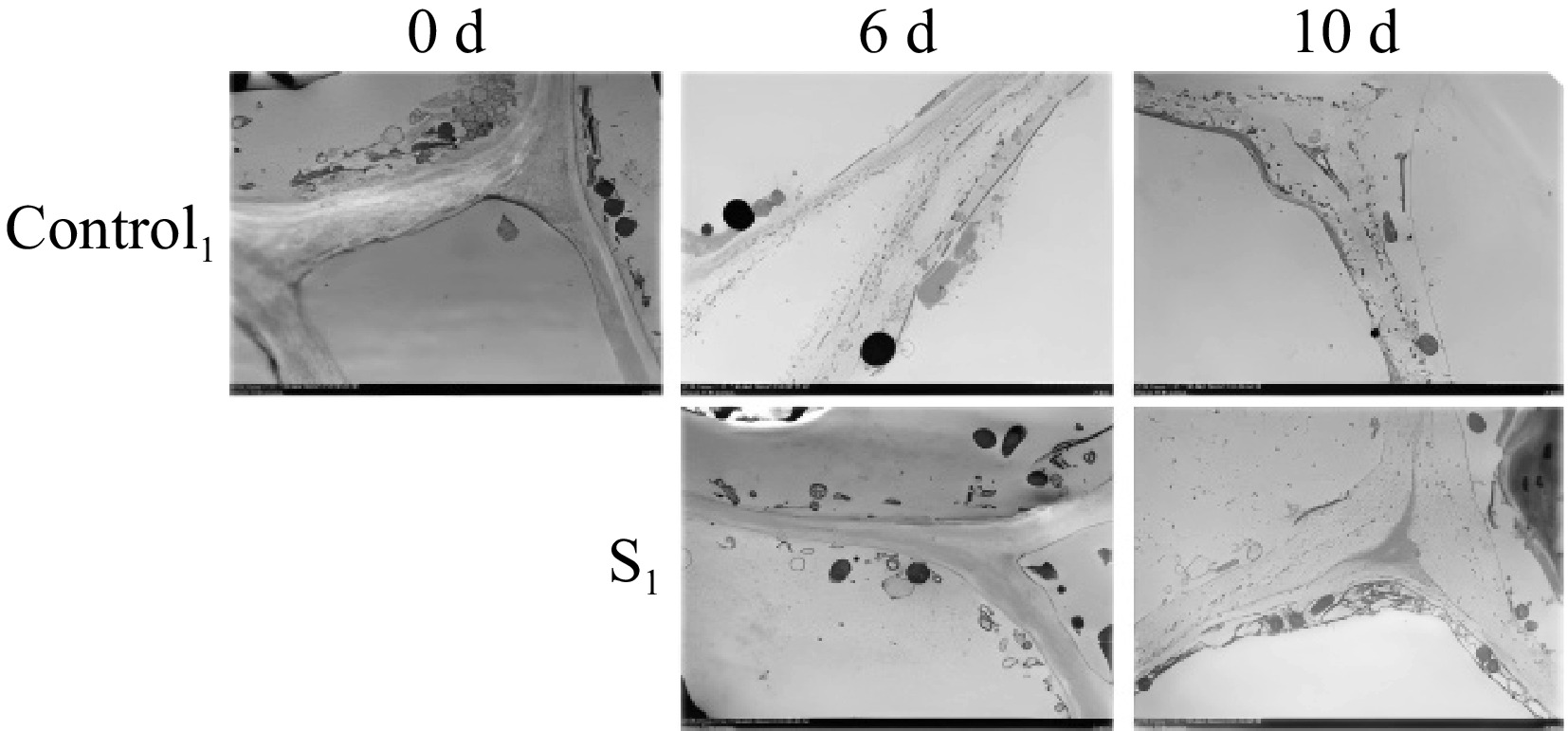

TEM observations of Actinidia arguta throughout storage periods are shown in Fig. 4. The evaluation of the TEM images of the Actinidia arguta fruit surface demonstrated the presence of fruit after vibration damage were more effectively relieved in the treatment group than in the control group. At 0 d, the cell wall and plasma membrane are intact and tightly bound. Starch granules were observed near the cell wall, mitochondria were intact and the triple junction region between cells was well defined. At 6 d of storage, the starch granules were degraded, the intercellular triangle liquefied, and the gaps became larger. The cell walls and cell membranes of the treated fruit were structurally intact, with organelles still present and cell membrane permeability reduced. In contrast, the mesocosm and cell wall of the control group cells were degraded, with a loose structure and irregular edges. After 10 d of storage, the cells were severely cavitated and structurally incomplete. The structure of the treated group was loose and the organelles disappeared. The intercellular layer and fiber filaments disappeared in the control group and the cell wall was severely damaged. The control group, however, experienced the disappearance of intercellular layers and filaments, along with considerable cell wall damage. These TEM findings suggest that light water loss can alleviate mechanical damage and maintain fruit quality.

Figure 4.

Observation and comparison of postharvest morphology of Actinidia arguta fruit under TEM after water loss treatment in 0, 6, and 10 d control group and treatment group S1.

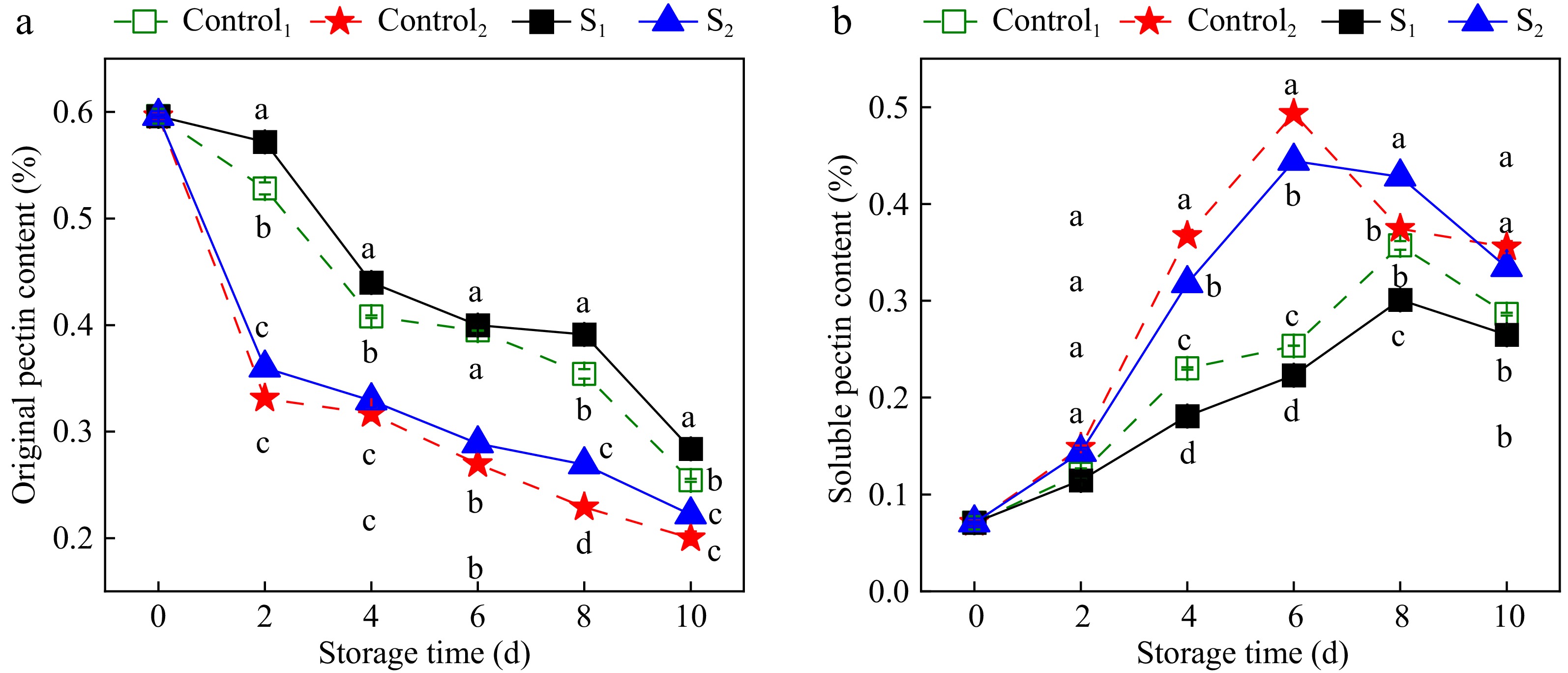

Changes in insoluble pectin and soluble pectin

-

The effect of water loss treatment on the pectin content of Actinidia arguta is shown in Fig. 5. With the prolongation of storage time, the original pectin content gradually decreased. The pectin content is gradually converted from original pectin to soluble pectin, so the original pectin is decreasing and the soluble pectin is increasing. Dehydration effectively slowed the conversion to soluble pectin within Actinidia arguta. The insoluble pectin gradually decreased during storage. 0.45% and 0.33% were found in the S1 and S2 groups at day 4, which were 1.13 and 1.06 times higher than the control group during the same period. Initially, from 0 to 2 d, soluble pectin levels between the treatment and control groups exhibited no remarkable divergence. However, the water loss treatment significantly inhibited the increase in soluble pectin content. It was 18.1% and 22.3% in the S1 group at day 4 and 6, which was 21.3% and 12% less compared to Control1. Meanwhile, the soluble pectin content of S2 was 31.8% and 44.4%, compared with 36.7% and 49.3% for Control2. Therefore, light dehydration treatment notably impedes pectin conversion and delays senescence in Actinidia arguta.

Figure 5.

Effect of water loss treatment on insouble pectin and soluble pectin of Actinidia arguta. The mean values were compared using Duncan's multiple range test at a significance of p < 0.05.

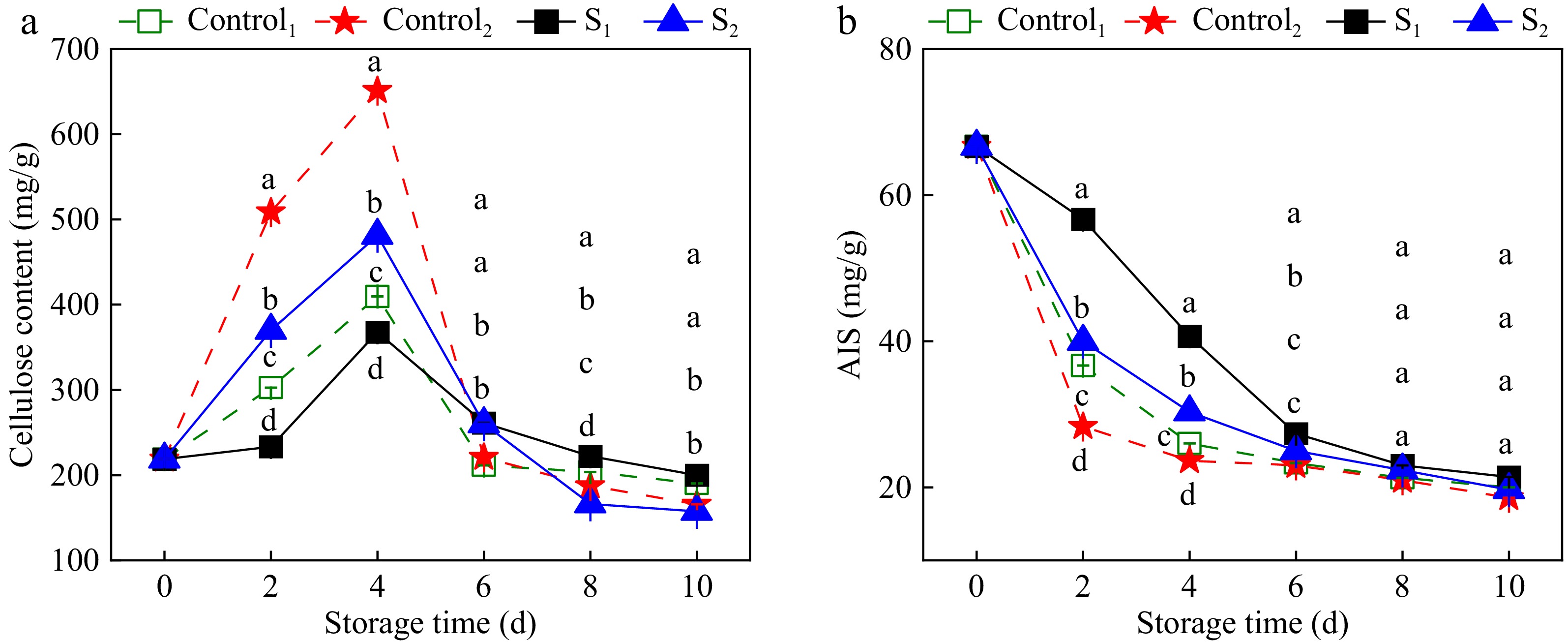

Alterations in cellulose and AIS

-

Figure 6 shows the effects of water loss on cellulose and AIS levels in Actinidia arguta. During storage, an initial increase followed by a decrease in cellulose was observed. Compared with the control group, the increase in cellulose content in the water loss treatment group was significantly inhibited. At 4 days of storage, the cellulose content in S1 and S2 was 367.91 and 481.4 mg/g, which was 10.2% and 26.1% less compared to Control1 and Control2. AIS, a critical cell wall component, mirrors the cell wall degradation and fruit softening processes. A declining trend in AIS was noted during storage. Nevertheless, the levels in the treatment group consistently exceeded those in the control group, indicating that water loss delayed the decline in AIS content. These results indicate that light water loss treatment curtails the degradation of cell wall components in Actinidia arguta fruit.

Figure 6.

Effect of water loss treatment on cellulose and AIS in Actinidia arguta. The mean values were compared using Duncan's multiple range test at a significance of p < 0.05.

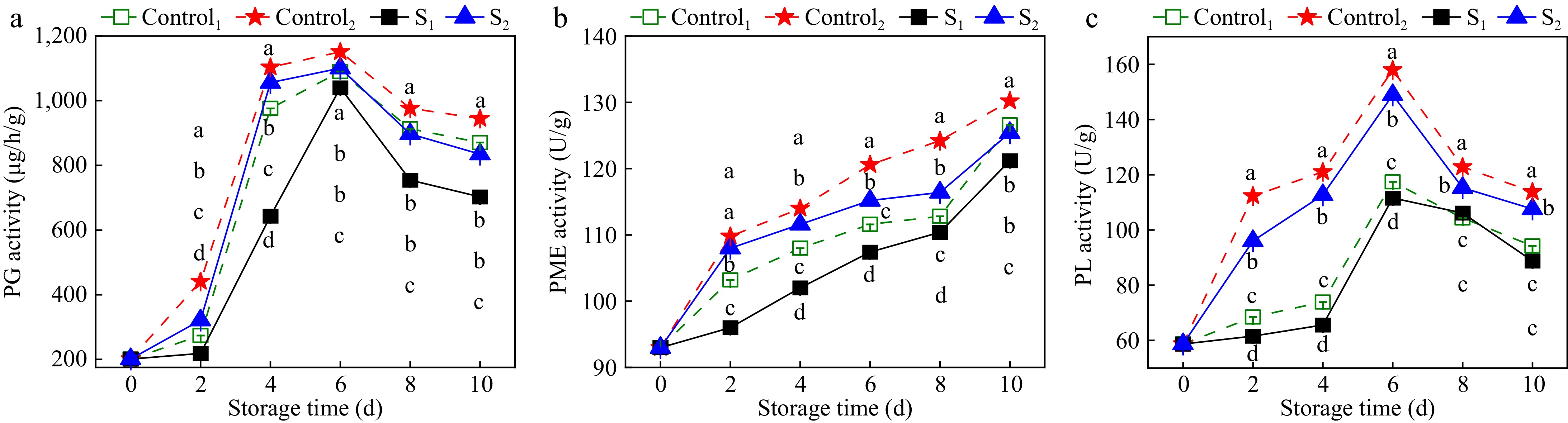

Variations in pectin-degrading enzyme activity

-

PG activity catalyzes polygalacturonic acid to galacturonic acid, thereby destabilizing cell components and facilitating fruit softening[32], is shown in Fig. 7a. The PG activity in Actinidia arguta initially increased, then decreased over the storage duration. Notably, PG activity in the dehydration-treated samples remained lower than that in the control group throughout the storage period. The peak PG activity in the control group was observed on the sixth day, reaching levels of 1.05 and 1.10 times higher than those in the S1 and S2 groups, respectively. These results suggest that light water loss treatment significantly attenuated PG activity in Actinidia arguta (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Effects of water loss treatment on the activities of (a) PG, (b) PME, and (c) PL enzymes in Actinidia arguta. The mean values were compared using Duncan's multiple range test at a significance of p < 0.05.

As shown in Fig. 7b, PME activity in Actinidia arguta increased with prolonged storage. After 6 d of storage, the PME activities of S1 and S2 were 107.4 and 115.2 U/g, which were 4% and 5% lower than those of Control1 and Control2. Light treatment significantly inhibited the increase in PME activity (p < 0.05), suggesting that the degradation of PME can be delayed by reducing the PME activity of Actinidia arguta.

Figure 7c shows the effect of light water loss treatment on PL activity in Actinidia arguta. The PL activity exhibited an initial increase followed by a decrease. Furthermore, PL activity in the treatment samples was lower than in the control group. The PL enzyme activities of Control1 and Control2 in the control group and S1 and S2 in the treatment group peaked on the sixth day of storage. The enzyme activities of S1 and S2 in the treatment group were 111.59 and 148.91 U/g lower than the control group by 5.2% and 6.8%, respectively. These results affirm that light water loss treatment significantly reduces PL enzyme activity in Actinidia arguta (p < 0.05).

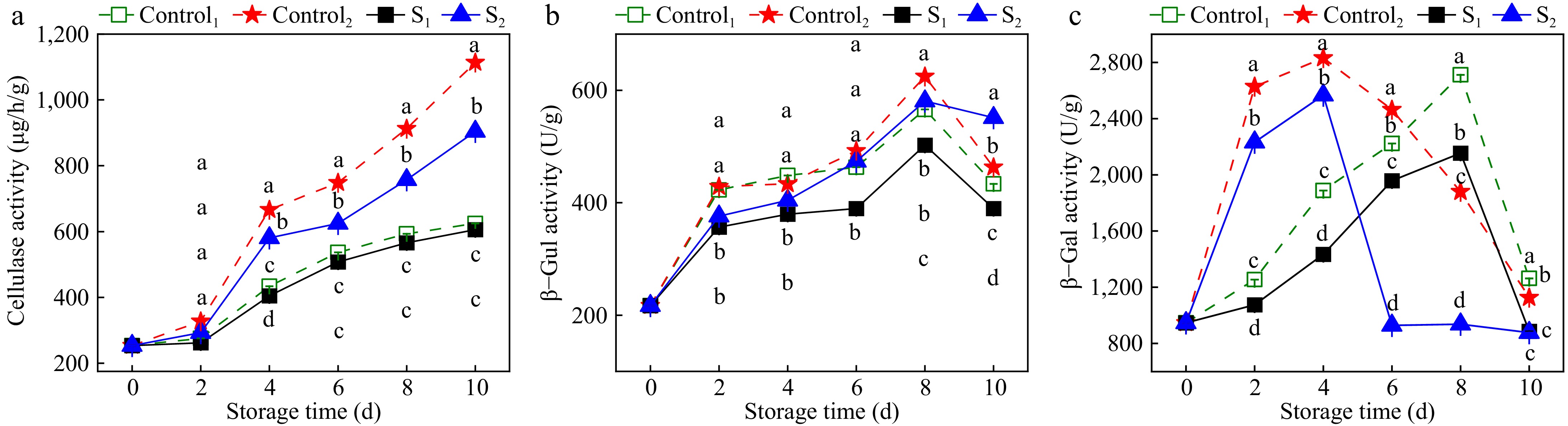

Changes in vitamin-degrading enzyme activity

-

Cellulase can promote cellulose degradation and regulate fruit ripening and senescence. The effect of light water loss treatment on the cellulase activity of Actinidia arguta is shown in Fig. 8a. The cellulase activity of the control group was significantly higher than the treatment group (p < 0.05). At 4 d of storage, the cellulase activities of Control1 and Control2 were 433.74 and 481.4 U/g, which made the cellulase activities of Control1 1.1 times higher than that of S1 and those of Control2 1.45 times higher than that of S2. As shown in Fig. 8b, the β-Gul activity of Actinidia arguta increased initially and then decreased with increasing storage time. The β-Gul activity of Actinidia arguta samples after water loss treatment was lower than the control group. β-Gul activities of S1 and S2 in the treatment group were 502.5 and 580.8 U/g, which were 11.2% and 7.1% lower than the Control1 and Control2 in the control group, respectively.

Figure 8.

Effects of water loss treatment on (a) CX, (b) β-Gul, and (c) β-Gal enzyme activities in Actinidia arguta. The mean values were compared using Duncan's multiple range test at a significance of p < 0.05.

The effects of water loss treatment on the β-Gal activity of Actinidia arguta are shown in Fig. 8c. With the extension of storage time, β-Gal activity initially increased and then decreased. Enzymatic activity within the treatment group was lower than the control group. Specifically, β-Gal activity reached a maximum on the fourth day of storage for both Control2 in the control group and S2 in the treatment group. The β-Gal activity for S2 in the treatment group was significantly lower than that of Control2 in the control group, with enzyme activities of 2,832 and 2,566.3 U/g, respectively. On the eighth day, peak β-Gal activity of Control1 in the control group and S1 in the treatment group was 2,712 and 2,154.9 U/g, with Control1 in the control group significantly surpassing that of S1 in the treatment group. These results indicate that light water loss during storage inhibits the activity of the cellulose-degrading enzyme.

Correlation analysis

-

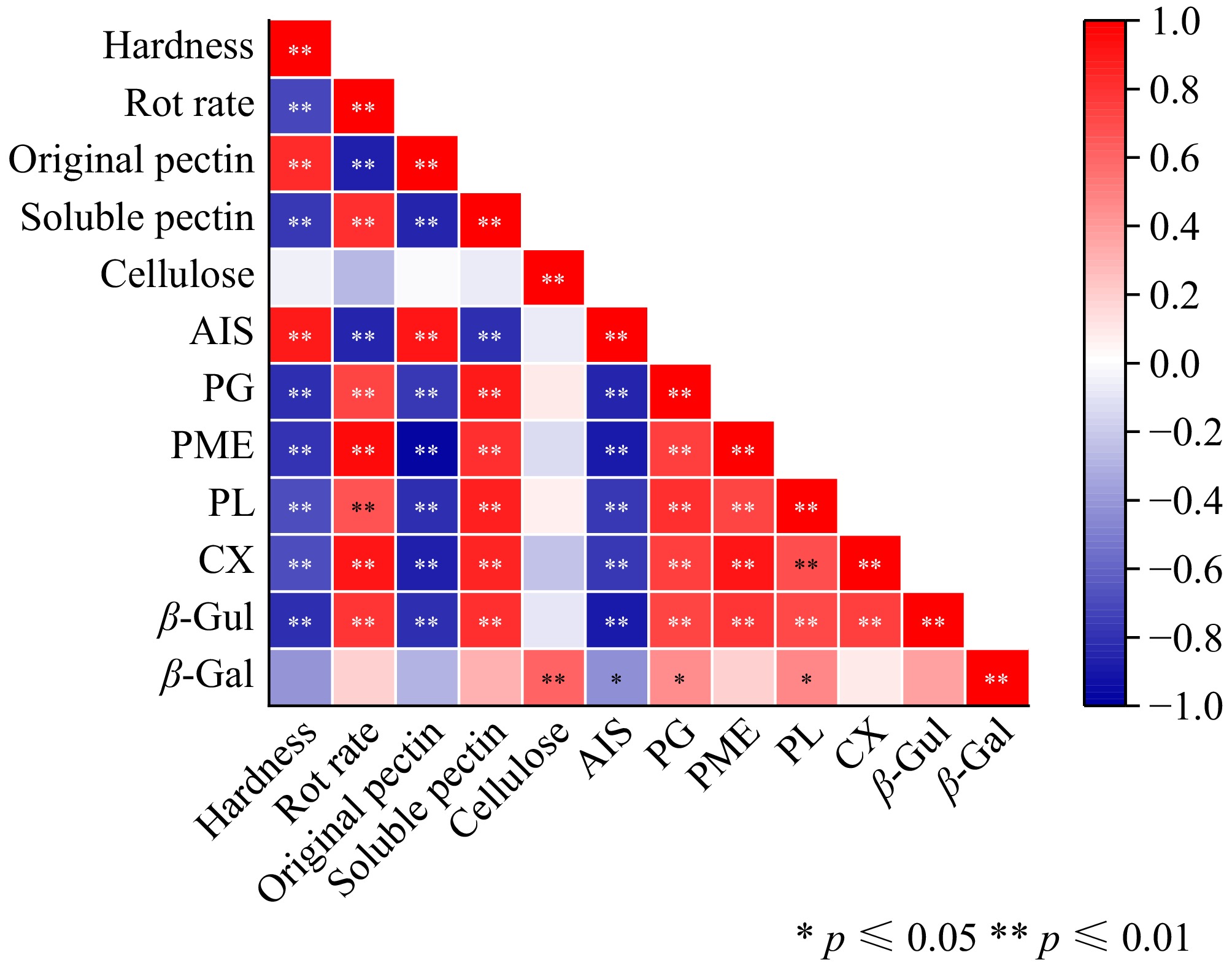

The correlation analysis results of fruit appearance quality, cell wall components, and cell wall-related enzyme activities are shown in Fig. 9. Fruit hardness was positively correlated with insoluble pectin and AIS content and negatively correlated with rot rate, soluble pectin, pectinase (PG, PME, and PL), cellulase, and β-Gul enzyme activities. The decay rate was positively correlated with the activities of soluble pectin, pectinase (PG, PME, PL), cellulase, and β-Gul and negatively correlated with the contents of insoluble pectin and AIS. Insoluble pectin was positively correlated with AIS content and negatively correlated with soluble pectin, pectinase (PG, PME, and PL), cellulase, and β-Gul enzyme activities. The activities of soluble pectin pectinase (PG, PME, and PL), cellulase, and β-Gul were positively correlated with AIS and negatively correlated with AIS. There was a significant positive correlation between cellulose and β-Gal enzyme activity. AIS was significantly negatively correlated with pectinase (PG, PME, and PL), cellulase, β-Gul, and β-Gal activity. PG was positively correlated with PME, PL, cellulase, and β-Gal enzyme activities. PME was positively correlated with PL, cellulase, and β-Gul enzyme activities. PL was positively correlated with cellulase and β-Gul enzyme activities. There was a significant positive correlation between cellulase and β-Gul activity.

Figure 9.

Pearson's correlation analysis. * represent significant correlations at p ≤ 0.05, and ** represent significant correlations at p ≤ 0.01. Shades of red represent various degrees of positive correlations and shades of blue indicate various degrees of negative correlations as indicated in the scale bar on the right of the heat map.

-

Post-harvest, fruit, and vegetables undergo various physiological activities to maintain normal metabolic functions. It is widely recognized that fruit ripening and softening entail complex processes characterized by cell wall degradation and alterations in cellular inclusions.

Light water loss may be due to the promotion of an early decline in fruit firmness, making the fruit resilient. S1 and S2 of hardness after light water loss were 11.53% and 13.3% lower than the CK group for the same period. Inconsistent with the fact that small amounts of water loss can also alter their physical properties, leading to wilting, shrinkage, and reduced hardness[33,34]. This may be due to the fact that light water loss leads to wrinkling of the pericarp and an increase in viscoelasticity, which in turn reduces mechanical damage. Stimulation of internal protective mechanisms in Actinidia arguta fruit enhances adaptation, thereby increasing the tolerance of the cell wall to mechanical damage during transportation and storage. In this study, the 4% water loss treatment maintained the cell wall composition, and the cellulase activities of S1 and S2 were 1.03 and 1.23 times lower than those of the CK group for the same period. Inhibition of pectinase and cellulase activities reduced the effect of mechanical damage on the cell wall through light water loss and retarded senescence of actinomycetes.

The cell wall is mainly composed of pectin and cellulose, and in immature fruit, pectin substances are combined with cellulose in the form of protopectin. The insoluble pectin is a type of non-water-soluble substance that makes the fruit appear solid, brittle, and hard. With maturation, pectin detaches from cellulose, transforming into water-soluble pectin, which leads to the softening and relaxation of fruit tissue and a reduction in hardness. Cellulose, a crucial dietary fiber, remarkably influences the quality and storage of fruit and vegetables and is essential for their mechanical damage resistance, disease prevention, and pest resistance. In this experiment, the analysis of cell wall degradation in Actinidia arguta fruit revealed a decline in insoluble pectin and AIS levels, an increase in soluble pectin, and an initial rise followed by a decrease in cellulose content. However, the slightly Actinidia arguta fruit contained higher contents of insoluble pectin and AIS and lower contents of soluble pectin and cellulose than those in the control group, aligning with findings from previous studies[35,36]. These findings are not entirely consistent with the findings of more rapid loss of vitamins A and C, more severe loss of flavor, and mechanical damage leading to discoloration in fruit with a light water loss of 4%[37]. This may be because when Actinidia arguta are respiratory leapfrog fruit, light water loss reduces the rate of respiration, slowing nutrient loss, and vitamin C declines.

During fruit ripening, enzymatic actions lead to cell wall lysis and transformation, resulting in cell wall thinning, loosening of cells, and subsequent softening[38,39]. PG, cellulase, and β-Gal are the main cell wall degrading enzymes, which play different roles in different stages of fruit softening[40].

S1 and S2 of PG and β-Gal enzymes were 1.24, 1.13, 1.43, and 1.28 times lower than those of the CK group in the same period. This study has demonstrated that water loss treatment decelerates the degradation rate of cell wall components, inhibits related enzyme activities, maintains cell firmness, and enhances the fresh-keeping effect.

Pectinase encompasses a group of complex enzymes responsible for the decomposition of pectin, primarily including PG, PME, and PL. PG is one of the pectin-degrading enzymes and is considered crucial for controlling the increase in water-soluble pectin content and facilitating fruit softening. PG activity, pivotal for pectin degradation, varies with the ripening stages, intensifying during the mid-phase of ripening. PME plays a vital role by demethylating pectin, thereby catalyzing its conversion to pectic acid and facilitating PG's action in fruit softening. PL is a pectin enzyme that lyses pectin polymers by trans-elimination. In this study, with fruit ripening and senescence, the activity of pectinase (PG and PL) increased first and then decreased, whereas the activity of PME increased consistently. The results indicated that light water loss treatment inhibited the increase in pectinase activity, thus slowing down the degradation of pectin and delaying the softening process of fruit. This is consistent with the results of Wang et al.[41].

Cellulose undergoes gradual hydrolysis to yield glucose. β-glucosidase, a vital cellulase component, influences cell wall dynamics during plant cell growth and development. The β-Gul enzyme, besides its role in cellulose glycosylation, is intricately linked to the metabolism of various substances in fruits and vegetables. β-galactosidase contributes to cell wall disintegration and catalyzes fruit softening. This study found that during the storage of Actinidia arguta fruit, cellulase activity, along with β-Gul and β-Gal activities, initially increased first and then decreased, with light water loss mitigating the rise in cellulase activity[42]. This result was also confirmed by the study. These findings suggest that light water loss hampers the senescence of the fruit cell wall during storage, preserving cell wall integrity and maintaining the cellular microenvironment and normal physiological metabolism.

Water loss can have a negative effect on fruits and vegetables, affecting sensory quality. However, suitable light water loss can alleviate mechanical damage in Actinidia arguta. Therefore, post-harvest light water loss combined with pre-cooling has the potential to alleviate mechanical damage during transportation, providing a reference and theoretical basis for alleviating post-harvest mechanical damage.

-

This paper investigated the combined effects of light water loss on the inhibition of cell wall metabolism to mitigate damage in Actinidia arguta during simulated mechanical vibration damage. The results showed that light water loss can alleviate the effects of post-harvest mechanical injury on the storage quality of Actinidia arguta by facilitating a reduction in hardness and decreasing susceptibility to mechanical stress. Furthermore, it conserves cell wall integrity, prolongs the fruit's aging process, and sustains marketability. In this paper, light water loss has a certain inhibitory effect on the cell wall metabolism of pericarp, and the specific inhibitory mechanism needs to be explored in further research (at the metabolic level).

This work was supported by the Liaoning Provincial Department of Education Scientific Research Funding Project (LSNJC202010), the First Batch of Liaoning 'Unveiling Leader' Scientific and Technological Projects (2021JH1/10400036), and the Liaoning Economic Forest Research Institute Joint Innovation Project (2023023).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Liu X, Cheng S; data collection: Wu Y; analysis and interpretation of results: Liu X, Yu X, Wu Y, Wei B, Zhou Q, Cheng S, Sun Y; draft manuscript preparation: Liu X, Yu X, Wu Y, Wei B, Zhou Q, Cheng S, Sun Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu X, Yu X, Wu Y, Wei B, Zhou Q, et al. 2025. Light water loss delays simulation of mechanical injuries from transportation vibration of Actinidia arguta by inhibiting cell wall metabolism. Technology in Horticulture 5: e023 doi: 10.48130/tihort-0025-0016

Light water loss delays simulation of mechanical injuries from transportation vibration of Actinidia arguta by inhibiting cell wall metabolism

- Received: 18 December 2024

- Revised: 17 March 2025

- Accepted: 27 March 2025

- Published online: 24 June 2025

Abstract: This study aimed to investigate the effect of light water loss on the mechanical injury of Actinidia arguta fruit by regulating cell wall metabolism. By comparing the effect of water loss on mechanical injury of Actinidia arguta fruit after simulated transport vibration, the changes in sensory quality and cell wall metabolism during storage were measured, compared with non-water-loss simulated transport vibration as the control. S1 and S2 of hardness after light water loss were 11.53% and 13.3% lower than the CK group for the same period, and the decay rate was 1.5 and 1.36 times higher than the CK group. Light water loss slowed the growth rate of pectin and cellulose and decreased the activities of polygalacturonase (PG), pectin methylesterase (PME), pectinlyase (PL), cellulase, β-glucosidase (β-Glu), and β-galactosidase (β-Gal). Electron and transmission microscopy imaging show that light water loss helps maintain cell wall structure and slows down cell wall degradation. The results indicate that light water loss alleviates post-harvest mechanical injury in Actinidia arguta by regulating cell wall metabolism and inhibiting cell wall degradation, thereby contributing to the maintenance of cell structural integrity to maintain fruit quality.

-

Key words:

- Actinidia arguta /

- Water loss /

- Mechanical injury /

- Cell wall metabolism