-

Recent findings have defined Selenicereus for pitaya species, rendering the use of Cereus megalanthus, Mediocactus megalanthus, and Hylocereus obsolete[1]. Consequently, this review builds upon and updates prior works that employed outdated classifications. In Brazil, 640 establishments are currently dedicated to pitaya (Selenicereus spp.) cultivation[2,3]. The country's Northeast region has shown particularly high potential for pitaya production due to its favorable environmental conditions, which include low humidity, intense solar exposure, and controlled protective systems, factors that collectively reduce pathogen incidence[4].

Owing to high market value and growing consumer demand, pitaya cultivation has rapidly expanded across Brazil, including into colder regions such as the South. Its exotic appearance and nutritional appeal have further driven international interest, particularly in Asian and European markets. Consequently, research efforts have increased in recent years, addressing aspects such as phenology, pollination biology, and fruit quality. However, despite expanding production, knowledge gaps persist in standardizing production practices and improving fruit quality under different climatic conditions. Given these trends, continued investigation into cultivation strategies and supporting technologies is essential to prolong shelf life and enhance both the sensory and nutritional quality of pitaya[5].

Before fruit development, the flowering stage is crucial in higher plants, marking the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth. Among the many factors that influence pitaya fruit set, photoperiod plays a pivotal role. Worldwide edaphoclimatic and seasonal variations lead to changes in day length; the 'critical photoperiod' is characterized by shorter days (< 12 h), resulting from decreased solar radiation hours that vary with latitude and season[6]. Temperature is another key factor: pitaya grows optimally between 25 and 35 °C[7], while growth is inhibited below 10 °C or above 38 °C. Although flowering is not typically observed during the critical photoperiod, plants entering the reproductive phase can experience photosynthetically induced flowering[8].

Under such conditions, nighttime light supplementation (LS) has emerged as a promising approach to induce or intensify pitaya flowering early in the reproductive phase by providing photosynthetically active radiation[6,9]. Investigations into floral induction in LS-treated pitaya showed that light-emitting diode (LED) illumination at night, particularly in winter, can interact with endogenous hormone signaling, especially cytokinin, which regulates flower formation, and gibberellic acid, which promotes flower development[7]. Therefore, this technology may modulate the production of plant hormones such as gibberellins, which are essential to flowering and subsequent pitaya development[10,11].

Although these physiological mechanisms are increasingly understood, there remains limited field-based evidence on the long-term effects of LS on fruit quality, particularly across different cultivars and growing seasons. Furthermore, most available studies do not integrate hormonal and biochemical responses with agronomic outcomes, leaving a gap in applied knowledge. Therefore, updating the literature with more comprehensive data is necessary to support the development of effective cultivation strategies.

Within this context, understanding the physiological and biochemical processes of pitaya development, combined with strategic light supplementation during flowering, may offer advanced insights for optimizing high-quality fruit production. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the influence of nighttime LS on the development and quality of different pitaya cultivars over multiple growing seasons, contributing to a more integrated understanding of its physiological, biochemical, and agronomic implications.

-

Pitaya plants are climbing cacti adapted to hot, humid climates, thriving in a variety of well-drained soils. Its flowers are large, fragrant, and predominantly white, reaching lengths of 20 to 30 cm. They are nocturnal and ephemeral, opening at dusk and wilting by sunrise. Flowering occurs in cycles and can be stimulated by a longer photoperiod. Pollination is mainly carried out by bees; however, some varieties are self-incompatible and require pollen from another plant to ensure proper fruit set. Cross-pollination enhances fruit set and improves characteristics such as weight, shape, and uniformity[11−13]. Harvest should take place once the peel displays a bright, uniform color, and the fruit must be consumed quickly due to its rapid progression toward senescence, resulting in pronounced losses in flavor and pulp texture[5,9,14].

The fruit has an oval or oblong shape, with yellow, pink, or red skin depending on the species and variety, covered by irregular scales. In Brazil, the interval between the formation of floral buds and the harvest of Selenicereus undatus fruits ranges from 50 to 66 d[15]. There are varieties with white and red pulp, contrasting with the numerous tiny, edible black seeds. Fruit formation occurs after pollination, with a growth period varying from 30 to 50 d, depending on the variety and environmental conditions. Harvesting occurs when the peel exhibits a bright, uniform color, and consumption should occur as soon as possible, as the fruit quickly reaches the senescent stage, resulting in significant losses in pulp flavor and texture[16]. Additionally, according to Magalhães et al.[17], from 40 d after anthesis, external quality deterioration of white pitaya S. undatus can be observed, manifested by wilting and discoloration of the peel.

Worldwide, four main pitaya varieties dominate commercial markets: Selenicereus costaricensis (purple pitaya), distinguished by dark purple pulp and red peel; Selenicereus megalanthus (yellow pitaya), with white pulp and yellow peel; Selenicereus undatus (white pitaya), which is the most common variety, featuring white pulp and red peel; and the Israeli Golden cultivar, similar to S. undatus but with a yellow peel[18,19].

During fruit development, pitaya translocates metabolized photosynthates through the phloem. The notable increase in sweetness during ripening stems primarily from the accumulation of glucose, fructose, and sucrose, which provide energy through respiration[20]. In contrast, the acidity of the fruit is mainly determined by organic acids, with malic acid being predominant in red-skinned pitaya[21−25].

Fruit softening is a key parameter influencing consumer acceptance, postharvest shelf life, and commercial value[26]. Controlled breakdown of cell wall polysaccharides such as cellulose, hemicelluloses, and pectins plays a central role in loosening the wall matrix, resulting in a softer, more hydrated pulp[27]. Aroma also holds particular importance in fruit quality, encompassing a complex array of volatile compounds. For instance, baby pitaya from the Brazilian cerrado (Selenicereus setaceus Rizz.) exhibited 12 volatile compounds in its pulp during development, with esters being the most abundant, followed by aldehydes and alcohols[20].

Additionally, substantial intraspecific variability exists—i.e., genetic differences among accessions within each pitaya species. Such variability manifests in traits of agronomic significance, including phenology, productivity, adaptability, disease resistance, fruit quality attributes, self-compatibility, vigor, precocity, and photoperiod sensitivity[28].

-

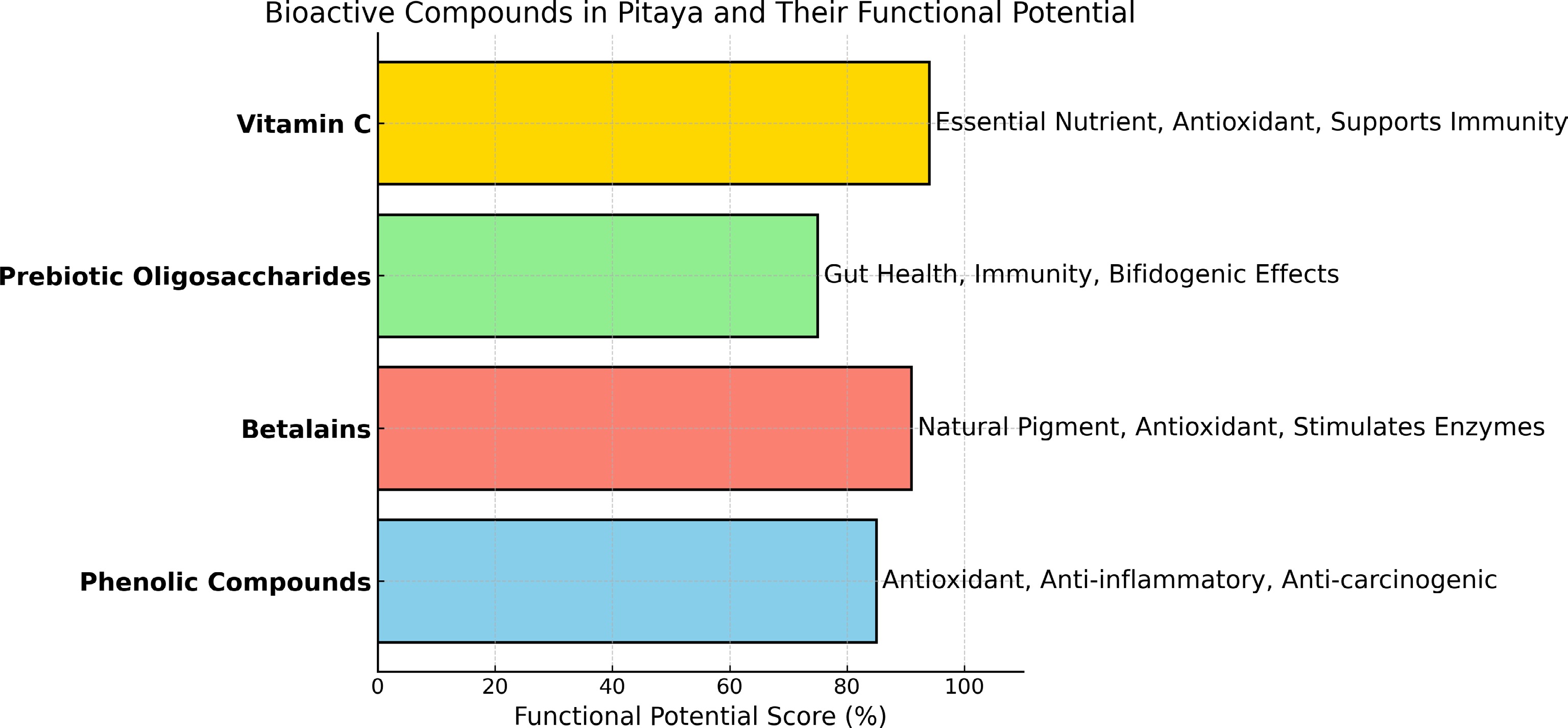

To construct the Functional Potential Score (Fig. 1), a semiquantitative evaluation system was employed based on three scientific criteria: (1) the number and relevance of reported biological functions (weighted at 40%); (2) the average content of each compound in pitaya as reported in the literature (30%); and (3) the extent of scientific evidence, considering both the number and quality of supporting studies (30%). Scores for each criterion were assigned on a scale proportional to their weight, and the final value was calculated as the weighted sum, expressed as a percentage. This approach is inspired by nutritional profiling frameworks and allows for a more integrated assessment of the functional relevance of bioactive compounds. Pitaya consumption offers various health benefits (Fig. 1), including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative, antitumor, anticancer, antimutagenic, and anti-atherogenic effects[12,20]. Among the phenolic compounds identified in different pitaya cultivars, gallic acid (CID: 370) stands out for its antioxidant, antimicrobial, and antimutagenic properties; ferulic acid (CID: 445858) exhibits antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity and contributes to cardiovascular protection; chlorogenic acid (CID: 1794427) is known for its role in regulating glucose metabolism and protecting liver function; and caffeic acid (CID: 689043) demonstrates antimicrobial and neuroprotective effects. Other relevant compounds include catechin (CID: 9064), which contributes to cardiovascular health and exhibits anti-obesity properties, and vanillin (CID: 1183), which has antimicrobial and antioxidant potential[11,12,22,29,30].

Figure 1.

Horizontal bar chart illustrating the bioactive compounds present in pitaya and their functional potential, based on published literature. Each bar represents a specific compound: phenolic compounds, betalains, prebiotic oligosaccharides, and vitamin C, along with their associated health benefits, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, gut health enhancement, and immunity support. The functional potential score is represented as a percentage, providing a comparative view of the importance of each compound.

In addition to phenolics, pitaya contains betalains—pigments such as betacyanins and betaxanthins—which are responsible for the red and purple hues of the fruit and possess strong antioxidant capacity. These compounds act by neutralizing reactive oxygen species and enhancing the activity of endogenous antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase and catalase[31]. Vitamin C (ascorbic acid, CID: 54670067) is another important bioactive present in pitaya pulp. As a water-soluble antioxidant essential to human health, vitamin C plays a critical role in immune function, collagen synthesis, and the reduction of oxidative damage and must be obtained through dietary sources due to the human inability to synthesize it[32−36]. Moreover, pitaya has shown potential in modulating gut health through the production of pectic oligosaccharides with prebiotic and bifidogenic properties. These compounds selectively stimulate beneficial intestinal microbiota and support digestive health[32]. Notably, pitaya-derived oligosaccharides have been associated with positive immunomodulatory effects, including increased serum immunoglobulin A (IgA) levels, an essential protein involved in mucosal immunity[33].

Recent studies have demonstrated that light supplementation can influence the biosynthesis of these bioactive compounds. Specifically, the use of LED lighting has been linked to enhanced accumulation of flavonoids, phenolics, and betalains, reinforcing the nutritional and functional profile of the fruit[7]. Furthermore, recent advances in varietal selection using multicriteria decision analysis have highlighted the potential of different genotypes for functional food development and adaptation to specific cultivation conditions[18].

Altogether, the presence and diversity of bioactive compounds in pitaya reinforce its value as a promising functional food ingredient with potential applications in health promotion and disease prevention. However, further studies are needed to deepen our understanding of the synergistic effects among these compounds and to standardize methods for their extraction and quantification.

-

During plant development, the shift from the juvenile to the adult stage is evidenced by the first flowering, marking the onset of the reproductive phase. In pitaya, this transition generally occurs about two years after planting, when the plant begins its initial cycle of flowering, and fruiting, exhibiting three to five characteristic peaks. After roughly five years of cultivation, both flowering and fruiting reach a stable pattern. Pitaya flowers typically open at night between 7:00 p.m. and 9:00 p.m. and remain open until sunrise (7:00 a.m. to 9:00 a.m.), lasting about 9 to 14 h[37].

Off-season flowering and fruiting stages tend to extend by 1 to 4 d compared to the primary flowering season[38]. Low winter temperatures further prolong reproductive processes, as demonstrated by studies in Vietnam and Thailand[39,40]. According to Master[41], an evaluation of photoperiod data by latitude indicates that Brazil (spanning +5° to −33°) experiences seasonal variations in day length. In some periods, particularly at higher latitudes, photoperiods can drop below 12 h, influencing pitaya floral bud differentiation, a key factor for flowering and fruit set.

Time and date observations of the critical photoperiod on the 15th of each month reveal that major pitaya-producing countries face suboptimal day lengths (below 12 h) during specific intervals (2024): from October to January (minimum 11 h) in Vietnam (21.02° N); from October to March (minimum 9 h 45 min) in China (39.90° N), Israel (31.77° N), and the United States (47.61° N); and from October to February (minimum 11 h) in Thailand (13.75° N). Colombia (4.71° N) experiences slightly shorter days only between December and January (minimum 11 h 55 min). While Brazil is not among the largest global producers, significant production states São Paulo (23° S), Santa Catarina (27° S), Minas Gerais (18° S), and Paraná (25° S), generally do not produce off-season pitaya (April to August) because the photoperiod ranges critically between 10.9 and 11.6, 10.7 and 11.9, 11.1 and 11.7, and 11.2 and 11.7 h/d, respectively. Exceptions include the states of Pará (3° S), which maintains photoperiods between 12.1 and 12.7 h/d year-round, and Ceará (5° S), where day length drops below 12 h/d only from October to February (11.5–11.9).

These photoperiod fluctuations underscore the importance of artificial light strategies, particularly LED technology, to mitigate seasonal limitations. Artificially extending day length allows pitaya producers worldwide to induce off-season flowering. Off-season pitaya production can be achieved by providing at least four hours of nighttime light[42].

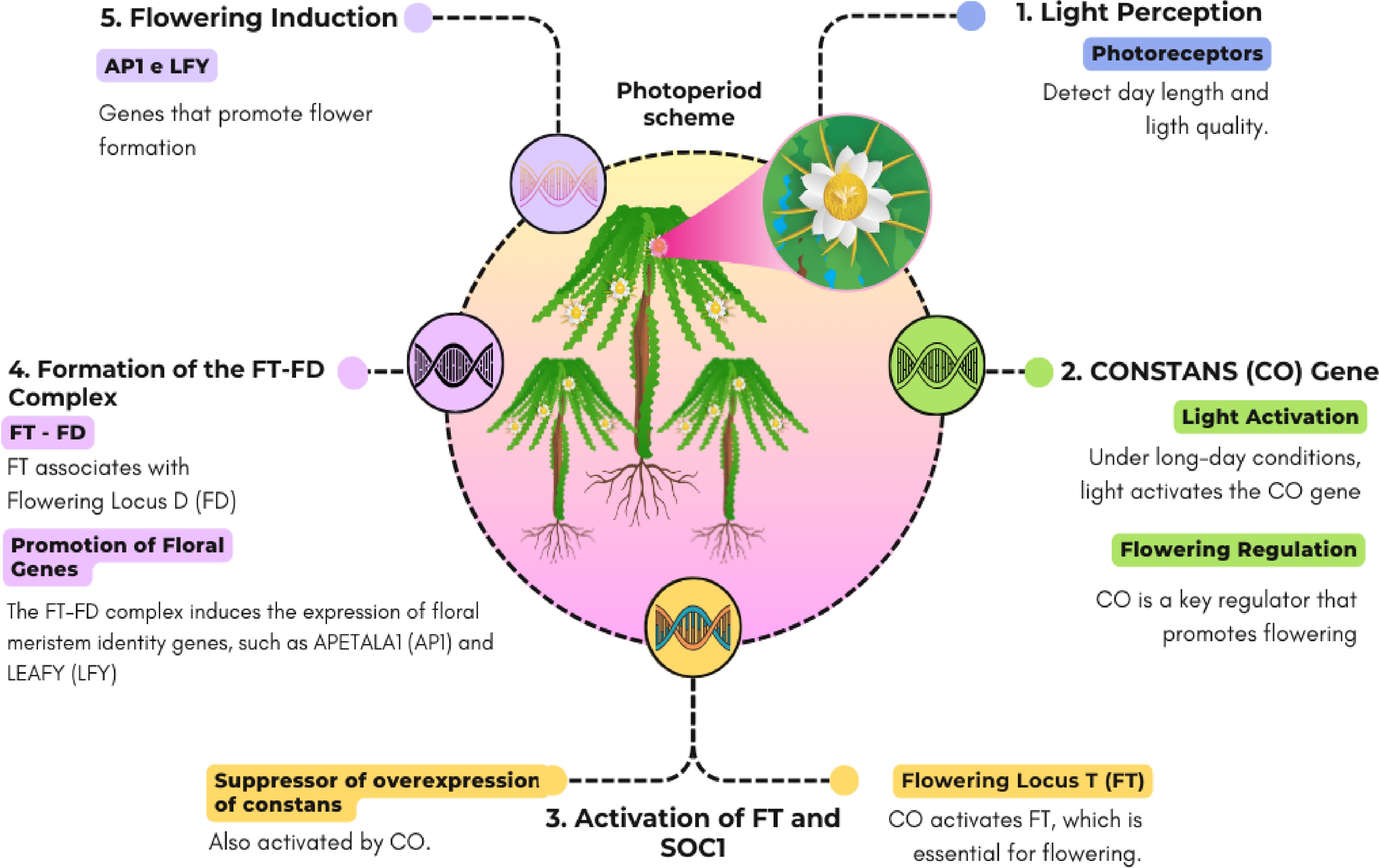

Flowering is governed by multiple biochemical and genetic pathways, such as those regulating photoperiod, vernalization, and gibberellic acid. Flower formation in plants encompasses three main stages: floral induction, floral evocation, and floral development[43]. These pathways respond to signals that regulate the timing of flowering, with the photoperiod pathway, in particular, responding to day length and light quality. Figure 2 illustrates a simplified model of the molecular mechanisms involved in this process. Under long-day conditions, the CONSTANS (CO) gene acts as a key regulator, activating FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) and SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CONSTANS 1 (SOC1). The FT protein subsequently forms a complex with FLOWERING LOCUS D (FD), which promotes the expression of floral meristem identity genes such as APETALA1 (AP1) and LEAFY (LFY), thereby inducing flowering[10].

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the photoperiod pathway regulating pitaya flowering. Photoreceptors perceive day length and light quality, initiating a molecular cascade involving CONSTANS (CO), which activates FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) and SUPPRESSOR OF OVEREXPRESSION OF CONSTANS 1 (SOC1). Once formed, the FT-FD complex promotes the expression of floral meristem identity genes, notably APETALA1 (AP1) and LEAFY (LFY), thereby inducing flower formation.

Nighttime flowering in pitaya can be stimulated and intensified through light supplementation, which provides photosynthetically active radiation[6]. This method has emerged as an attractive strategy for farmers to enhance main-season productivity and produce pitayas during the off-season[9]. Among the most promising approaches are light-emitting diodes (LEDs), which emit little to no heat, unlike conventional lamps[43]. According to Bourget[44], the light emitted by LEDs mainly depends on the semiconductor materials used, covering wavelengths from 250 nm to over 1,000 nm. Additionally, LEDs are more durable, compact, and cost-effective, offering both economic and environmental advantages over incandescent, fluorescent, and halogen lamps[45].

A technological approach involving artificial lighting during the off-season in southern Taiwan showed that red-fleshed pitaya responded better than white-fleshed pitaya, requiring extended illumination from 33 up to 48 d. This practice also led to increases in fruit mass and soluble solids content[38]. Wang et al.[7], noted that light supplementation triggered an initial rise in cytokinin levels, followed by a decline, while gibberellin, auxin, salicylic acid, and jasmonic acid levels increased during floral bud formation. After one week, there were further increments in gibberellin, ethylene, auxin, and abscisic acid in the floral buds. Regarding fruit development, nighttime lighting can directly influence photomorphogenesis by promoting higher biosynthesis of bioactive compounds such as anthocyanins, carotenoids, and other phytochemicals[46−49], which are crucial for the nutritional and sensory quality of the fruit.

A significant correlation between improved fruit quality attributes and LS was also observed in pitaya cultivars and clones from Central America, Taiwan, and Vietnam. Studies indicate that this technique leads to notable increases in pulp yield and soluble solids content in varieties such as 'Orejona,' 'Lisa,' 'Rosa,' 'Jhubei 3,' 'D4,' 'D15,' 'D18,' and 'Pequeno Nick'[38]. Likewise, the 'Zimilong' cultivar showed significant elevations in soluble solids[48]. Jiang et al.[49] emphasize that nighttime interruption under temperatures above 15 °C does not cause floral abortion in winter, demonstrating that light supplementation is sufficient for fruit production; high-quality fruits were obtained when the percentage of floral buds remained below 50%. Nguyen et al.[50], testing low-power compact fluorescent lamps in six out of seven experiments (Selenicereus spp.), found improvements in quality indicators, fruit number per plant, and overall yield.

-

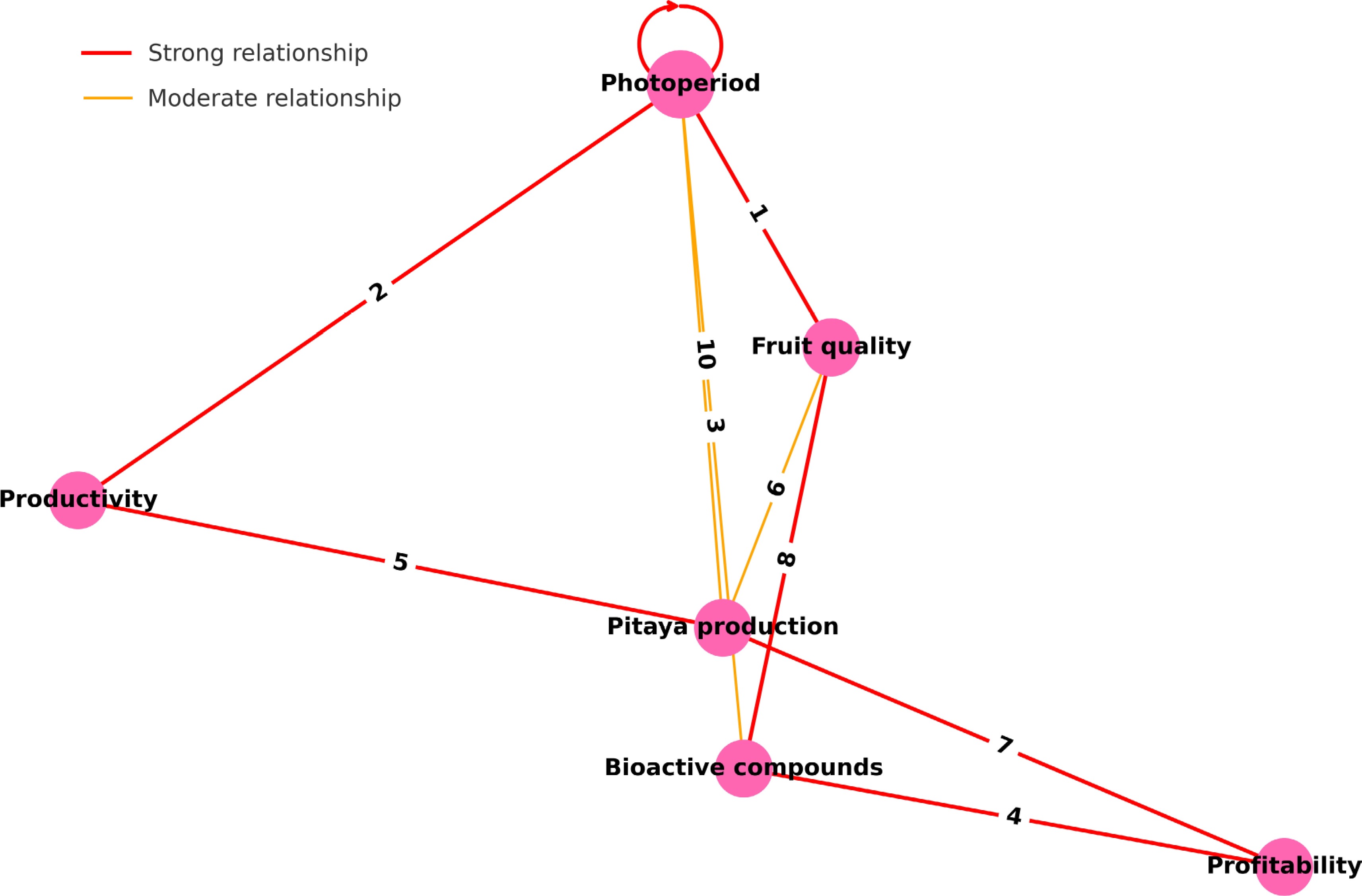

To synthesize the key interactions associated with light supplementation in pitaya (Selenecereus spp.) cultivation, a conceptual network diagram was developed (Fig. 3). This diagram was constructed based on a critical review of the literature, drawing from studies published between 2008 and 2024 that addressed the physiological, biochemical, and agronomic responses of pitaya to controlled photoperiods and supplementary lighting. Variables were selected for their frequent citation in light-related studies and included photoperiod, fruit quality, productivity, bioactive compounds, pitaya production, and profitability.

Figure 3.

Network representation of relationships among photoperiod, pitaya production, productivity, fruit quality, bioactive compounds, and profitability based on literature related to light supplementation in pitaya. Strong relationships are indicated by red edges, while moderate relationships are shown in orange. The numbered connections represent specific studies supporting each link: (1) the production gap for dragon fruit[39], (2) the induction of off-season flowering using light[40], (3) the effect of LED spectrum on in vitro pitaya plantlets[16], (4) the influence of light on bioactive compounds and their bioaccessibility[12], (5) the role of light in pitaya production and commercialization[4], (6) its effect on postharvest physiology and fruit quality[5], (7) the economic return of pitaya in 29 Brazilian cities[3], (8) antioxidant activity modulated during fruit development[15], (9) light-induced promotion of hormone biosynthesis[7], and (10) the application of LED lighting in off-season cultivation[41].

Directional relationships were established to reflect the influence of one variable over another, with interaction strength categorized as strong or moderate based on consistency and depth of evidence in the literature. Red arrows denote strong relationships, and orange arrows represent moderate ones. Numerical labels on the edges correspond to specific references provided in the legend below the figure, enhancing traceability and scientific rigor.

The photoperiod variable occupies a central and elevated position in the network due to its foundational role in initiating and regulating physiological events in pitaya. Its strong connections with fruit quality[39], productivity[40], and moderate influence on bioactive compounds[16] are supported by several controlled studies using LED lighting under off-season or short-day conditions (e.g.,[7,16,39−41]). These studies report not only increased flowering and yield[40,41] but also enhanced accumulation of phenolics and betalains under specific light spectra[3].

A particularly robust relationship was observed between bioactive compounds and profitability[12], indicating that enhanced nutritional quality can increase market value and consumer appeal. Likewise, productivity and fruit quality contributed to overall pitaya production[4,5], both conceptually and empirically, highlighting the need for practices that balance yield and quality. The final connection from pitaya production to profitability[3] completes the economic cycle initiated by light-based management.

Additionally, strong links were observed between bioactive compounds and fruit quality[15], reinforcing the multifactorial benefits of photoperiod optimization. Recent findings also emphasize the role of light in modulating endogenous hormone levels[7], supporting flowering even in suboptimal climatic conditions, and LED systems have been proposed as effective tools to stimulate off-season flowering in tropical regions[41].

In summary, the network model offers a visual synthesis of how light supplementation acts as a strategic driver of productivity, nutritional enhancement, and economic return in pitaya cultivation. These conceptual relationships are not only grounded in empirical evidence but also highlight potential avenues for future research and technological application in tropical fruit production systems. These findings are critical for guiding agricultural strategies, demonstrating that photoperiod manipulation can be an effective tool to optimize both the production and quality of pitaya, with economic and nutritional benefits. These results highlight the importance of LS not only for fruit quality but also for productivity under reduced photoperiod conditions. Utilizing light supplementation technology boosts plant growth and development and can be a decisive factor in the economic competitiveness of pitaya cultivation. In an agricultural setting marked by a steadily growing demand for high-quality fruit, LS emerges as a viable and innovative strategy for producers seeking to maximize profits, particularly during winter.

Hence, the development and implementation of techniques such as light supplementation not only enhance pitaya quality but also represent a significant advance in modern agriculture. This integrated approach merges productivity, sustainability, and quality into a single cultivation model—a crucial factor for strengthening the sector, ensuring food security, and sustaining the economic viability of tropical fruit crops.

-

No robust evidence exists concerning a more rigorous evaluation of pitaya fruit quality produced under light supplementation during flowering beyond observed increases in productivity, yield, fruit mass, and soluble solids content. Light supplementation, particularly using LEDs, mitigates issues related to pitaya's critical photoperiod, thereby enhancing off-season productivity. While preliminary results indicate positive effects on fruit development and overall quality, further research is needed to elucidate the phytochemical and nutritional composition of these fruits, which is likely to increase proportionally with fruit mass. A deeper understanding of how artificial lighting influences internal fruit quality parameters would contribute significantly to optimizing production strategies, supporting both market value and functional appeal.

Given the growing global demand for high-quality and health-promoting fruits, the integration of light supplementation technologies into pitaya cultivation systems holds great promise. It can extend harvest windows, improve sensory and nutritional profiles, and increase market value and profitability. To optimize these benefits, it is essential to standardize experimental parameters, such as light spectrum, intensity, duration, and cultivar-specific responses, ensuring both efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

Future research should also address the postharvest behavior of light-treated fruits, possible interactions among light-induced metabolites, and the long-term physiological effects of artificial lighting. Integrative studies that combine transcriptomic, metabolomic, and agronomic data are especially needed to elucidate the mechanisms underlying photoperiod manipulation and its influence on pitaya quality.

Ultimately, light supplementation represents a sustainable and innovative tool to improve the efficiency, resilience, and competitiveness of tropical fruit production. Its thoughtful application can not only support food security and functional nutrition but also strengthen the economic viability of small- and medium-scale producers, particularly in regions constrained by seasonal limitations.

This study was partially financed by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

-

The authors confirm their contribution to the article as follows: conception and design of the study: da Silva LGM, da Costa CAR; Data collection: da Silva LGM, da Costa CAR; Batista GA; Amorim KA; analysis and interpretation of results: da Silva LGM; preparation of draft manuscript: da Silva LGM, da Costa CAR, Amorim KA, Batista GA; formal analysis: da Silva LGM, Aparecida Salles Pio L, de Abreu DJM, José Rodrigues L, de Barros Vilas Boas EV, Elena Nunes Carvalho E; data curation: da Silva LGM, da Costa CAR; supervision: Aparecida Salles Pio L, de Abreu DJM, de Barros Vilas Boas EV, Elena Nunes Carvalho E; project administration: Elena Nunes Carvalho E. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

da Silva LGM, da Costa CAR, Batista GA, Amorim KA, de Abreu DJM, et al. 2025. Effect of light supplementation on pitaya productivity and quality during the off-season. Technology in Horticulture 5: e022 doi: 10.48130/tihort-0025-0018

Effect of light supplementation on pitaya productivity and quality during the off-season

- Received: 18 February 2025

- Revised: 11 April 2025

- Accepted: 15 April 2025

- Published online: 10 June 2025

Abstract: Recent taxonomic updates confirm Selenicereus as a valid genus, replacing older nomenclature such as Cereus megalanthus, Mediocactus megalanthus, and Hylocereus. Despite pitaya's adaptability to hot and humid climates, flowering and fruit development are strongly influenced by environmental factors such as photoperiod and temperature. Critical photoperiods, especially those falling below 12 h of daylight in higher latitudes, can inhibit flowering. Nighttime light supplementation (LS) has emerged as a key approach to overcoming these limitations, demonstrating considerable potential for inducing or enhancing flowering during off-season periods. Studies show that LS using LEDs substantially increases fruit yield by up to 44%, pulp mass by 35%, and soluble solid content by 18% in certain cultivars. Hormonal changes—including elevated cytokinin, gibberellin, auxin, and other phytohormones—have been observed, correlating with improved floral bud formation and subsequent fruit quality. Furthermore, LS has been associated with increases of up to 25% in total phenolics and 30% in carotenoids, reinforcing the nutritional and sensory attributes of pitaya. Pitaya's intraspecific variability also underlines the importance of investigating genetic, agronomic, and biochemical factors to optimize production and meet the growing consumer demand for high-quality fruit. Although the current body of research highlights LS as a promising means to boost yields and quality, comprehensive evaluations of the phytochemical and nutritional profiles of LS-treated pitayas remain limited. Future studies should elucidate how increased fruit mass under LS conditions translates to proportional gains in bioactive compounds, providing valuable insights for producers and researchers aiming to refine pitaya production practices.

-

Key words:

- Selenicereus /

- Light supplementation /

- Photoperiod and flowering /

- Quality