-

Hybridization can be categorized into ancient hybridization (occurring in historical evolutionary events) and hybridization among extant species (observed in currently living plant populations), defined as the outcrossing and gene flow between populations that differ in multiple heritable characters that affect fitness[1]. It is an important mechanism for the formation of new species and is one of the key reasons for species diversity[1−3]. Many important crops, such as wheat, cotton, and rapeseed, originated from ancient hybridization events among different species[4]. The genealogical relationships between parents and their self-incompatibility (SI) affect interspecific hybridization compatibility[5,6].

Studies have found that hybrid speciation is not evenly distributed on the plant phylogenetic tree but is clustered in certain plant groups, such as Orchidaceae, Lamiaceae, Asparagaceae, and Asteraceae, which have more hybrid species[5]. Approximately 40% of plant families and 16% of plant genera in North America, Australia, and Europe are involved in hybridization, and Orchidaceae has the highest tendency for hybridization among 25 large families[1,6]. In some plant groups, hybridization is not only common among phylogenetically closely related species but also among distantly related species, playing a significant role throughout the evolutionary history of the group, such as in tree ferns[7]. Furthermore, ancient hybridization events play a significant role in causing inconsistencies in phylogenetic relationships, in groups such as the Polygonaceae[8], Paphiopedilum[9], and Rosaceae[10]. In summary, current studies mainly focus on the distribution of ancient hybridization events and their impact on phylogenetic relationships, while the influence of reticulate evolutionary relationships on hybridization in extant species is lacking in reports. Additionally, in some plant groups, interspecific hybridization often follows the SI × self-compatibility (SC) rule[11]; that is, genetic crosses between species fail in one direction, but the reciprocal cross is compatible. Therefore, exploring genealogical relationships among parents, SI, and interspecific hybridization compatibility is valuable for studying the origin and diversification of new species, as well as for understanding the factors that influence hybridization compatibility among extant species.

The Orchidaceae family, comprising approximately 8% of all vascular plant species, represents one of the most taxonomically diverse lineages within angiosperms[12]. Within this family, SI systems are predominantly observed in the subfamily Epidendroideae—which encompasses nearly 80% of orchid species—where multiple SI mechanisms are hypothesized to coexist[13,14]. The genus Dendrobium serves as a particularly well-documented model for studying these complex SI systems. Furthermore, orchids demonstrate a pronounced propensity for interspecific hybridization, as evidenced by both natural occurrences and controlled breeding experiments[5,6]. This combination of reproductive strategies strongly suggests that the interplay between hybridization barriers and SI mechanisms may constitute fundamental drivers underlying the remarkable species diversification observed in Orchidaceae.

Dendrobium, one of the largest genera in Orchidaceae (approximately 750 genera and 27,000 species[12]), includes around 1,450 species[13] and is characterized by a high proportion of SI and hybridization compatibility[13,14]. This genus exhibits an exceptionally high level of species richness. Numerous ancient hybridization events were identified through phylogenetic analysis, suggesting that these events may play a significant role in the formation of species diversity in Dendrobium[15]. Additionally, the interspecific hybridization compatibility of some species has been reported in breeding studies of Dendrobium, such as D. polyanthum × D. nobile, and D. chrysotoxum × D. nobile[16,17]. However, the phylogenetic relationships and hybridization compatibility among extant species remains poorly understood. Furthermore, Dendrobium has a high proportion of SI species[13,14], and it has been found that interspecific hybridization among species follows the SI × SC rule[17], i.e., the number of capsules produced was significantly higher in crosses where SI species acted as pollen donor for SC species, in comparison with the converse situation. SI significantly impacts interspecific hybridization outcomes. However, the role of mixed SI/SC species (i.e., Dendrobium taxa exhibiting both self-incompatible and self-compatible traits within populations) in shaping hybridization compatibility remains poorly characterized. Specifically, these intermediate populations—potentially bridging the evolutionary gap between obligate SI and fully SC species—may hold critical insights into the mechanisms driving cross-species compatibility, yet their contributions remain under-explored.

This study investigates the influence of SI and reticulate evolution on interspecific hybridization compatibility among extant Dendrobium species. First, SI in Dendrobium species was assessed through artificial pollination experiments, and SI data across 124 taxa was systematically compiled and published within the genus to establish the prevalence and distribution of SI traits. The phylogenetic relationship and reticulate evolutionary relationship of Dendrobium were reconstructed to explore the distribution pattern of SI species. The hybridization results of Dendrobium species with known SI were collected and analyzed. Hybridization experiments and reticulate evolutionary relationship analyses were performed on 11 Dendrobium species with the most complex reticulate evolutionary relationships to validate the effects of SI and reticulate evolution on the interspecific compatibility of Dendrobium.

-

A total of 30 Dendrobium species (Table 1, species labeled M) were collected from Malipo, Yunnan, China, and were grown under simulated native environmental conditions in the greenhouse at East Campus of Hebei Agricultural University, Baoding City, Hebei Province, China. The quantity of healthy plants varied between two and 12 individuals, depending on the species. During the research, the flowering period was normal without any artificial interference. The self-pollination results from other reports and in this study are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Self-pollination results of 124 Dendrobium species.

Species Self-incompatibility Dataset of origin Species Self-incompatibility Dataset of origin D. aciculare SI P D. jiaolingense SC H D. acinaciforme SI P D. keithii SI P D. aduncum SC H D. kingianum SI P D. aggregatum SI P D. lamellatum SI P D. albosanguineum SI P D. leonis SI H, P D. aloifolium SI P D. leptocladum SI P D. alterum SI P D. linawianum SI P D. aphyllum SI M, P D. lindleyi SI M, H, P D. arachnites SI P D. linguella SI P D. bellatulum SC H D. lituiflorum SI P D. bensoniae SI M D. loddigesii SC H, P D. bicameratum SI P D. longicornu SI M, H D. bicaudatum SI M D. macrophyllum SC P D. bigibbum SC P D. macrostachyum SC P D. bilobulatum SC/SI P D. mannii SI P D. blumei SI P D. monile SI P D. brevimentum SI P D. moniliforme SI M, H D. brymerianum SC, SI, SC M, H, P D. moschatum SI P D. bullenianum SI P D. mucronatum SI P D. capillipes SC, SI H, P D. nathanielis SI P D. cariniferum SC, SI H, P D. nobile SC H, P D. christyanum SC, SI M, H D. officinale SI, SC, SI M, H, P D. chrysanthum SI, SC M, H D. pachyglossum SI P D. chrysotoxum SI, SC, SI M, H, P D. pachyphyllum SI P D. compactum SI P D. panduriferum SI P D. crepidatum SI, SC, SC M, H, P D. parcum SI P D. crumenatum SI M, H, P D. parishii SI M, P D. crystallinum SC, SC, SI/SC M, H, P D. pendulum SC H, P D. cucullatum SI H D. phalaenopsis SI, SI/SC M, P D. dalbertsii SC P D. planibulbe SI P D. delacourii SC P D. podagraria SI P D. denneanum SI, SC M, H D. polyanthum SC H D. densiflorum SI, SC H, P D. porphyrochilum SI M, H D. denudans SI P D. primulinum SI P D. devonianum SI M, P D. pulchellum SI P D. disticum SI P D. salaccense SC H, P D. dixanthum SC P D. scoriarum SC H D. draconis SI, SI, SI/SC M, H, P D. secundum SI M, H, P D. ellipsophyllum SI P D. senile SI P D. erostelle SI P D. setifolium SI P D. exile SC P D. signatum SI M, H D. falconeri SI H, P D. sinense SI P D. farmeri SI P D. spatella SI M D. fimbriatum SC, SI H, P D. speciosum SI P D. findlayanum SC H D. spectabile SC P D. formosum SI M, P D. stratiotes SC P D. gibsonii SI P D. strebloceras SC P D. gouldii SC P D. strongylanthum SI M, H D. gratiosissimum SI H, P D. stuposum SC, SI, SC M, H, P D. griffithianum SI P D. subulatum SI P D. hainanense SC H D. sulcatum SC P D. hancockii SI, SC H, P D. terminale SC H D. harveyanum SI H D. tetrodon SC P D. hendersonii SI P D. thyrsiflorum SI, SC, SI M, H, P D. hercoglossum SC M, H, P D. tortile SC P D. heterocarpum SC H, P D. transparens SC H D. hildebrandii SC P D. trantuanii SC H D. huoshanense SI M D. trigonopus SC H D. indivisum SI P D. undulatum SC P D. infundibulum SC/SI P D. unicum SI H D. jenkinsii SC M, H, P D. virgineum SI P D. jiajiangense SC H D. wardianum SC H, P SI: Self-incompatibility species; SC: Self-compatibility species; SI/SC: Both. P: Dataset from Pinheiro et al.[17]; H: Dataset from Huang[21]; M: Dataset in this study. Artificial pollination

-

Flowers were selected after two or three days of blooming to perform hand-pollinations. The pollination was performed during 9:00–11:00 a.m. The lip was broken off by tweezers, the anther cap was removed, and then pollinium was moved to the stigma cavity. Separate tweezers were used for each pollination event. All the tools were sterilized. Finally, the time of capsule formation and abscission was recorded[13].

Distribution pattern of SI in the Dendrobium phylogenetic tree

-

To include as many pollinating species as possible, the chloroplast genome and nuclear ITS sequences were selected to reconstruct the phylogenetic relationship of Dendrobium. All 72 complete chloroplast genomes from NCBI (on March 17, 2024) were downloaded, including all 70 Dendrobium species and two outgroups (Supplementary Table S1). All sequences were first aligned using MAFFT v7[18]. Then, the best model, GTR + R, was determined by PhyML[19]. PhyML[19] and MrBayes v-3.2.7[20] were used to reconstruct the phylogenetic tree with default parameter settings. Ninety-four nuclear ITS sequences from NCBI (on March 29, 2024) were downloaded, including 92 Dendrobium species and two outgroups (Supplementary Table S2). All sequences were first aligned using MAFFT v7[18]. Then, the best model, GTR + R, was determined by PhyML[19]. PhyML[19] and MrBayes v-3.2.7[20] were used to reconstruct the phylogenetic tree with default parameter settings.

Data from Pinheiro et al.[17], Huang[21], and self-pollination experiments in this study were compiled to characterize the species as SC, SI, and SI/SC. These data were then mapped to the phylogenetic tree of Dendrobium for analyzing their distribution pattern. According to the method described by Zhang et al.[22], based on nuclear sequence information and chloroplast genome sequence information, SplitsTree[23], with default parameter settings, was used to reconstruct the reticulate evolutionary relationships of 94 species (nuclear sequence information) and 72 species (chloroplast genome), exploring the distribution pattern of SI, SC, and SI/SC species in the reticulate evolutionary relationships of Dendrobium.

Investigation for the interspecific compatibility pattern of Dendrobium

-

The interspecific compatibility results of Dendrobium species were collected based on published SI, SC, and SI/SC data (Supplementary Table S3), including those of Johansen[16], Pinheiro et al.[17], Wilfret[24], Pan et al.[25], Li et al.[26], Ren[27]. Furthermore, based on phylogenetic analyses conducted in this study, 11 Dendrobium species exhibiting the most intricate reticulate evolutionary histories were selected, and targeted hybridization experiments were carried out to assess their cross-compatibility patterns. According to the method by Zhang et al.[22], based on nuclear sequence information and chloroplast genome sequence information, reticulate evolutionary relationships of the 11 species were further specifically analyzed using SplitsTree[23] with default parameter settings.

-

A total of 124 Dendrobium species with SI data were analyzed in this study (Table 1). Among these, 69 species exhibited SI, 36 were SC, and 19 displayed mixed SI/SC traits (i.e., populations containing both SI and SC individuals). In the Dendrobium species compiled in this study, the proportion of SI species was 55.64%−70.96%. This proportion was slightly lower than Johansen's result (44 of 61 species were SI, accounting for 72%)[16] but was basically consistent with the results of Pinheiro et al. (43 of 63 species were SI, accounting for 68%)[17].

Distribution of SI in Dendrobium

-

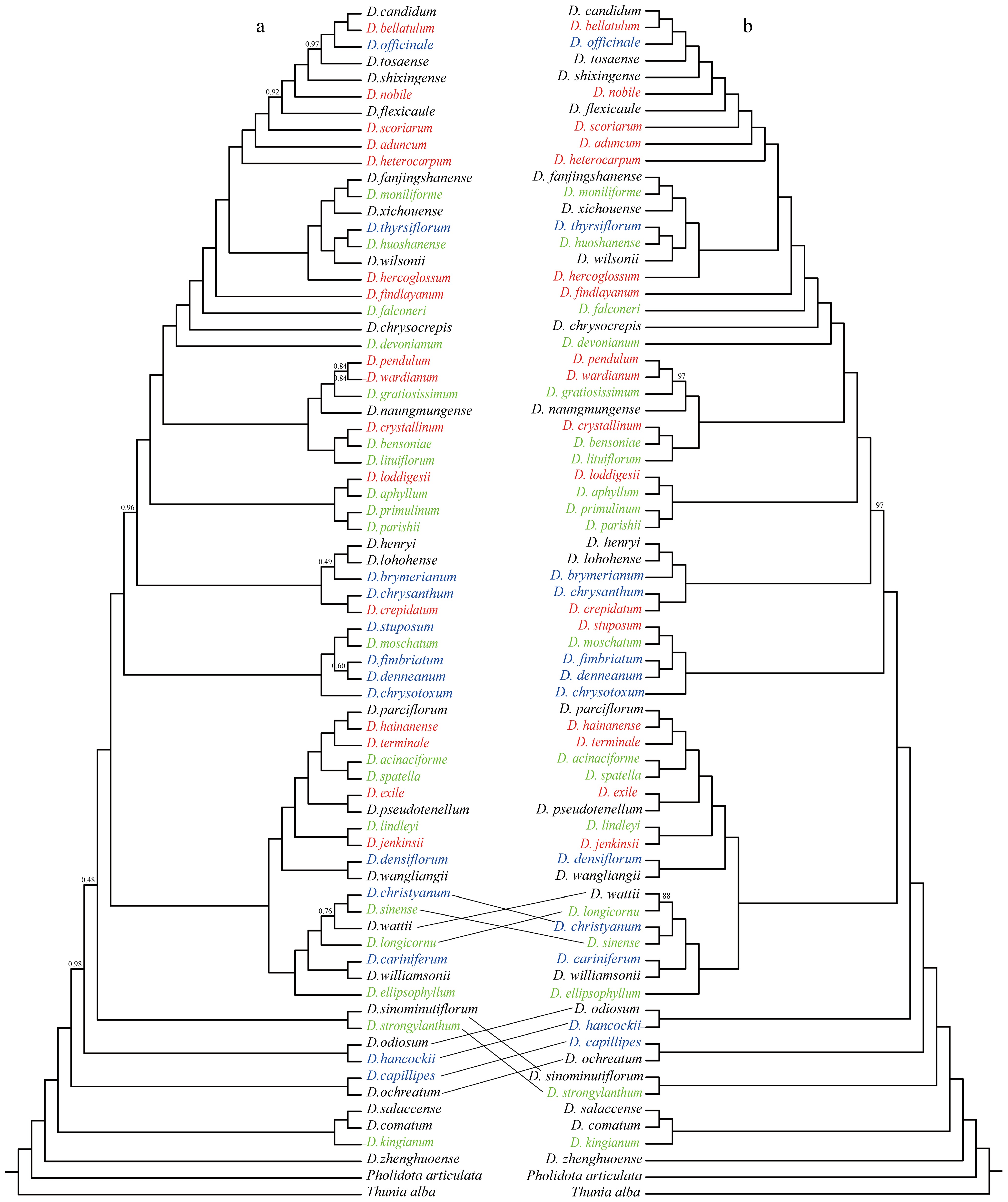

To explore the distribution of SI species in the Dendrobium phylogenetic tree, all 70 published Dendrobium complete chloroplast genome data were utilized to reconstruct the phylogenetic tree of Dendrobium, with Thunia alba and Pholidota articulata as outgroups, using Bayesian and maximum likelihood methods, respectively. In the maximum likelihood (ML) tree and the Bayesian (BI) tree (Fig. 1a & b), most of the sites had support rates of 1.00. There was a phylogenetic sites that received less than 90% support in both phylogenetic trees, which were D. wattii and D. christyanum−D. sinense in the ML tree and D. wattii and D. longicornu in BI tree. There were two conflicting sites between the maximum likelihood tree and the Bayesian tree. In the maximum likelihood tree, D. wattii and D. christyanum−D. sinense had a closer relationship but with a lower support rate (0.76), while in the Bayesian tree, D. wattii and D. longicornu were placed in a sister clade, with a support rate of 88%. Additionally, in the maximum likelihood tree, D. sinominutiflorum−D. strongylanthum and D. ellipsophyllum−D. candidum were placed in a sister clade, while in the Bayesian tree, D. sinominutiflorum−D. strongylanthum and D. ochreatum-D. candidum had a closer relationship (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of 70 Dendrobium species based on chloroplast whole-genome reconstruction, with T. alba and P. articulata as outgroups. (a) Maximum likelihood tree, with bootstrap support values (BS) on each branch, and BS of 1.00 not shown. (b) Bayesian tree, with posterior probability (PP) on each branch, and PP of 100% not shown. Green species names indicate SI species; red species names represent SC species; blue species names indicate SI/SC species.

Among 70 species of the genus Dendrobium, 48 species had SI data, which consisted of 18 SI species, 16 SC species, and 14 SI/SC species. To explore the distribution of these species in Dendrobium, the data of 48 species were fitted with the explicitly phylogenetic tree reconstructed in this study (Fig. 1). The results showed that SI species, SC species, and SI/SC species were widely distributed in the phylogenetic tree.

Based on the nuclear ITS, 94 species (including 92 Dendrobium species and two outgroups) were selected to reconstruct the phylogenetic relationship of Dendrobium. 48 of 92 species of the genus Dendrobium had SI data, which consisted of 20 SI species, 15 SC species, and 13 SI/SC species. The maximum likelihood tree and Bayesian tree showed that SI species, SC species, and SI/SC species were widely distributed in the phylogenetic tree (Supplementary Figs S1, S2).

Then, 124 species were fitted using the more comprehensive Dendrobium phylogenetic tree (based on nuclear ITS and seven chloroplast genes) from Xu[28]. Eighty-six species were mapped to the phylogenetic tree successfully, including 39 SI species, 29 SC species, and 18 SI/SC species. The distribution patterns of SI, SC, and SI/SC species were widely distributed in all branches of the phylogenetic tree, which is similar to the results from the phylogenetic tree based on the complete chloroplast genome and nuclear ITS sequence information (Supplementary Fig. S3).

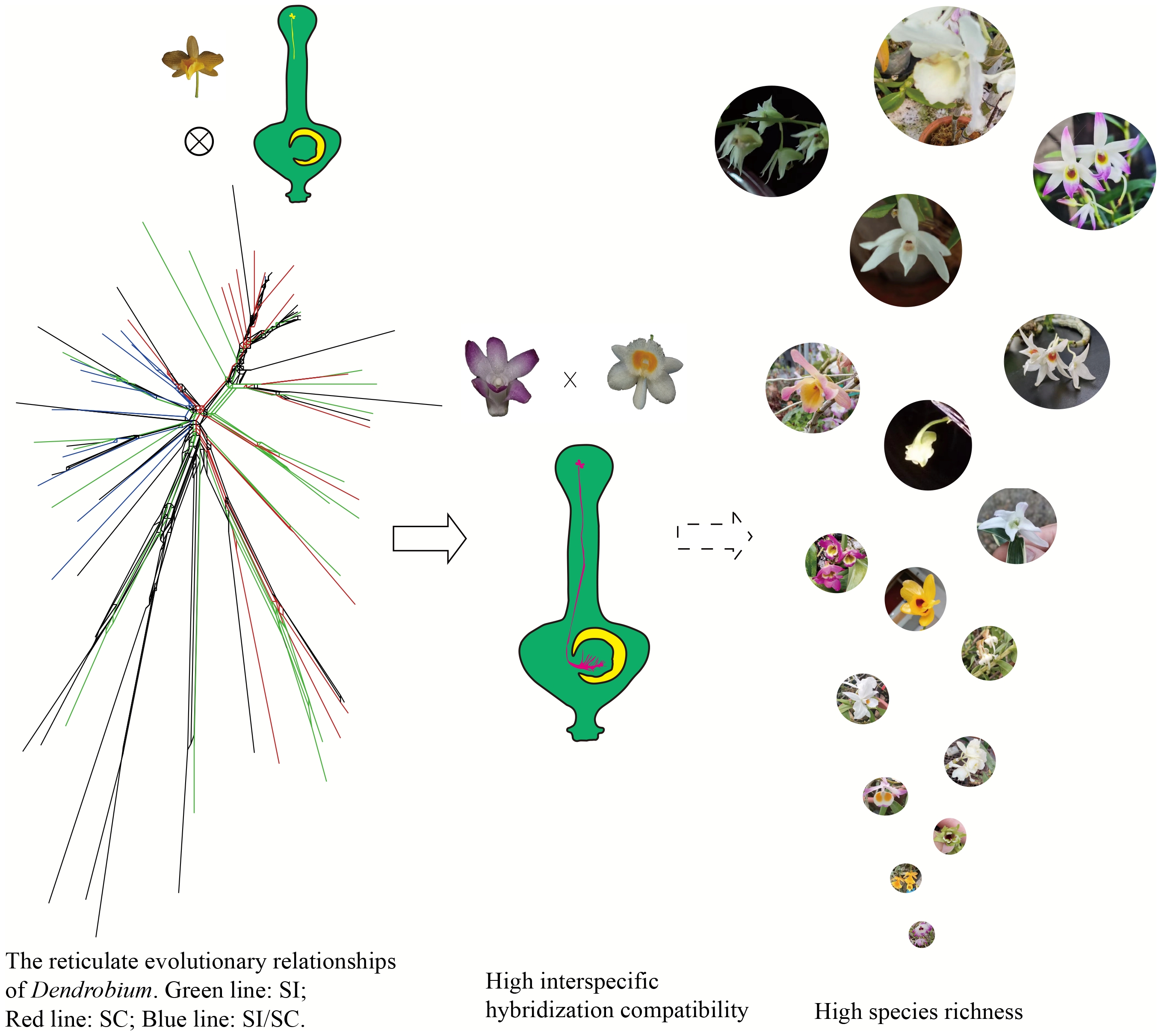

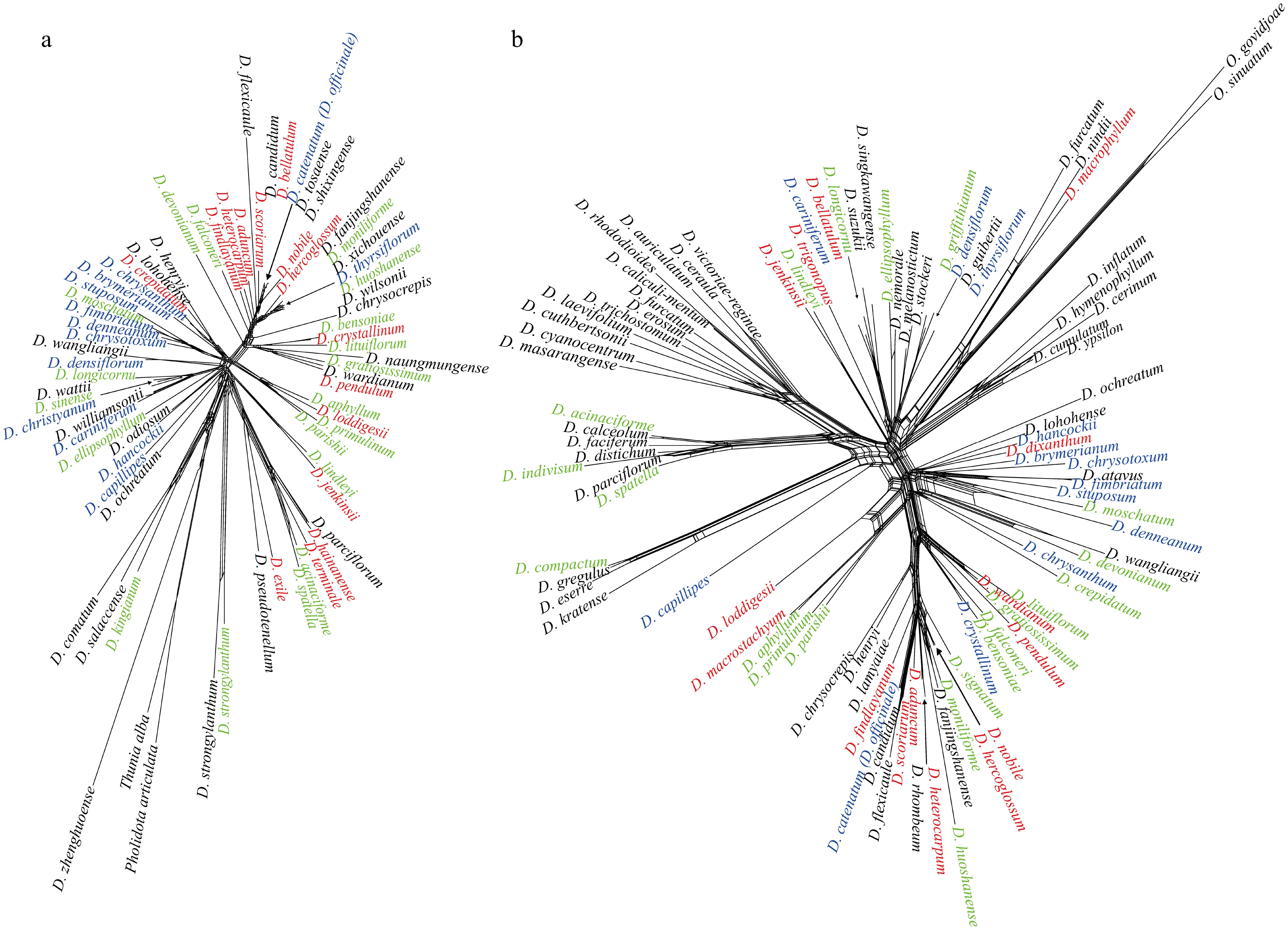

Further, based on nuclear sequence information and chloroplast genome, the reticulate evolutionary relationship was reconstructed, and the known SI species fitted into the reticulate evolutionary relationship (Fig. 2). Phylogenetic analysis revealed that SI, SC, and SI/SC species were broadly dispersed across the Dendrobium evolutionary tree. Importantly, results from all four analytical approaches consistently indicated a homogeneous distribution of these mating systems, with no observable clustering linked to specific evolutionary lineages.

Figure 2.

Reconstructs of the reticulate evolutionary relationships of Dendrobium. (a) Chloroplast genome data, with T. alba and P. articulata as outgroups. (b) Nuclear ITS sequences, with O. govidjoae and O. sinuatum as outgroups. Green species names indicate SI species; red species names represent SC species; blue species names indicate SI/SC species.

The interspecific hybridization of Dendrobium

-

Among the 124 species of Dendrobium collected, 64 species had hybridization results (including 38 SI species, 59.38%; 15 SC species, 23.44%; and 11 SI/SC species, 17.19%; Supplementary Table S4), with a total of 623 non-redundant hybridization combinations (Supplementary Table S3, 630 redundant hybridization combinations). Among these hybrid combinations, 152 exhibited successful compatibility (Supplementary Table S3), and the interspecific compatibility rate was 24.05% (Table 2). Among the 64 species, 42 species (23 SI species, 10 SC species, and nine SI/SC species) were evenly distributed on the Dendrobium phylogenetic tree (Supplementary Fig. S4) and had broad representation.

Table 2. The rate of interspecific compatibility of 64 Dendrobium species based on self-incompatibility.

Pollen receptor Pollen donor Number of interspecific hybridization combinations Number of fruit combinations produced The rate of interspecific compatibility SI SI 178 23 13.14% SC SC 80 38 47.50% SI/SC SI/SC 28 13 46.43% SI SC 69 6 8.70% SC SI 70 17 24.29% SI SI/SC 63 13 20.63% SI/SC SI 64 14 21.88% SC SI/SC 41 19 46.34% SI/SC SC 39 9 23.08% All All 632 152 24.05% SI: Self-incompatibility species; SC: Self-compatibility species; SI/SC: Both; all: SI, SC and SI/SC species. To explore the effect of SI on interspecific compatibility in Dendrobium species, the hybrid combinations were collected and sorted according to the SI within Dendrobium. The results (Table 2) showed that the interspecific hybridization of Dendrobium followed the SI × SC rule, i.e., the rate of interspecific compatibility was higher in crosses where SI species acted as pollen donors for SC species (24.29%), in comparison with the converse situation (8.70%). In addition, the rate of interspecific compatibility of SC × SC (47.50%) was much higher than that of SC × SI (24.29%), SI × SC (8.70%), and SI × SI (13.14%) combinations, conforming to the additional explanation of the SI × SC rule. Among all the hybrid combinations with different self-compatibilities, the compatibility rates of SC × SC (47.50%), SI/SC × SI/SC (46.43%), and SC × SI/SC (46.34%) combinations were much higher than the average level, approaching twice the average value (24.05%).

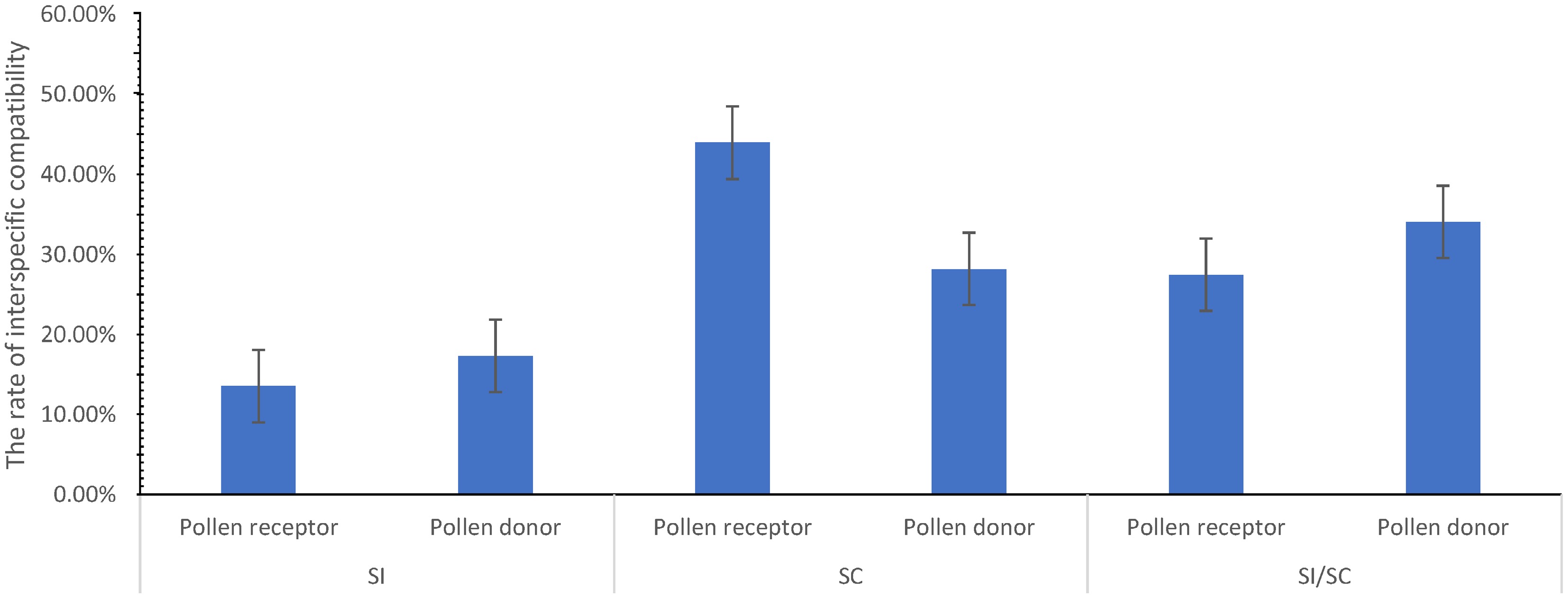

Then, the hybridization results of Dendrobium species were collected according to the parental SI to explore the difference in the rate of interspecific compatibility between different hybridization parents. The results (Fig. 3) showed that the rate of interspecific compatibility of SI species and SI/SC species as pollen donors (SI species, 17.31%; SI/SC species, 34.09%) was higher than those as pollen receptors (SI species, 13.55%; SI/SC species, 27.48%), while the rate of interspecific compatibility of SC species as a pollen receptor (43.98%) was higher than that as a pollen donor (28.19%). Moreover, the rate of interspecific compatibility of SC and SI/SC species as hybridization parents was higher than the rate of the average interspecific compatibility (24.05%).

The interspecific compatibility between groups with complex reticulate evolutionary relationships

-

Based on the results of the reticulate evolutionary relationship (Fig. 2), 11 Dendrobium species with known SI for hybridization experiments were selected, including four SI species, three SC species, and four SI/SC species, which have complex reticulate evolutionary relationships. The hybridization experiments (Table 3) showed that there were a total of 21 compatible hybridization combinations: D. aphyllum × D. chrysotoxum (12.5 %, M), D. bensoniae × D. crystallinum (42.86 %, M), D. chrysotoxum × D. hercoglossum (25 %, M), D. chrysotoxum × D. moniliforme (50 %, Pan), D. crystallinum × D. bensoniae (25 %, M), D. denneanum × D. officinale (50 %, M), D. hercoglossum × D. officinale (15.38 %, M), D. moniliforme × D. hercoglossum (100 %, M), D. moniliforme × D. officinale (100 %, M), D. moniliforme × D. chrysotoxum (42.86 %, M), D. nobile × D. officinale (100 %, M), D. nobile × D. moniliforme (40 %, Pan), D. officinale × D. denneanum (100 %, M), D. officinale × D. moniliforme (80 %, M), D. officinale × D. bensoniae (60.71 %, M), D. officinale × D. crystallinum (55.56 %, M), D. officinale × D. chrysotoxum (90 %, M), D. officinale × D. hercoglossum (75 %, M), D. officinale × D. nobile (37.5 %, M), D. officinale × D. huoshanense (66.67 %, M), D. officinale × D. aphyllum (30 %, R), D. officinale × D. nobile (33.33 %, L), D. officinale × D. chrysotoxum (86.7 %, L). These compatible combinations accounted for 52.50% of the 40 non-redundant hybridization combinations tested.

Table 3. The rate of interspecific compatibility of 11 Dendrobium species.

Pollen receptor Pollen donor Flower Capsule set The rate of capsule set (%) Dataset

of originD. aphyllum D. officinale 2 0 0 M D. bensoniae D. officinale 27 0 0 M D. bensoniae D. crystallinum 7 3 42.86 M D. bensoniae D. chrysotoxum 2 0 0 M D. chrysotoxum D. officinale 3 0 0 M D. chrysotoxum D. crystallinum 2 0 0 M D. chrysotoxum D. bensoniae 2 0 0 M D. chrysotoxum D. hercoglossum 4 1 25 M D. crystallinum D. officinale 15 0 0 M D. crystallinum D. bensoniae 8 2 25 M D. crystallinum D. chrysotoxum 2 0 0 M D. denneanum D. officinale 2 1 50 M D. hercoglossum D. officinale 13 2 15.38 M D. hercoglossum D. chrysotoxum 8 0 0 M D. hercoglossum D. bensoniae 3 0 0 M D. hercoglossum D. crystallinum 3 0 0 M D. moniliforme D. bensoniae 2 0 0 M D. moniliforme D. crystallinum 2 0 0 M D. moniliforme D. hercoglossum 3 3 100 M D. moniliforme D. officinale 20 20 100 M D. moniliforme D. chrysotoxum 14 6 42.86 M D. nobile D. officinale 3 3 100 M D. officinale D. denneanum 7 7 100 M D. officinale D. moniliforme 10 8 80 M D. officinale D. bensoniae 28 17 60.71 M D. officinale D. crystallinum 9 5 55.56 M D. officinale D. chrysotoxum 20 18 90 M D. officinale D. hercoglossum 12 9 75 M D. officinale D. nobile 8 3 37.5 M D. officinale D. stuposum 3 0 0 M D. stuposum D. officinale 4 0 0 M D. aphyllum D. huoshanense 14 0 0 M D. aphyllum D. chrysotoxum 8 1 12.5 M D. chrysotoxum D. aphyllum 12 12 0 M D. officinale D. huoshanense 6 4 66.67 M D. chrysotoxum D. moniliforme 1 0 0 WP D. moniliforme D. chrysotoxum 1 0 0 WP D. officinale D. aphyllum 10 3 30 R D. chrysotoxum D. moniliforme 8 4 50 Pan D. nobile D. moniliforme 10 4 40 Pan D. officinale D. nobile 15 5 33.33 L D. officinale D. chrysotoxum 15 13 86.7 L D. nobile D. officinale 15 0 0 L D. nobile D. chrysotoxum 15 0 0 L D. chrysotoxum D. officinale 15 0 0 L D. chrysotoxum D. nobile 15 0 0 L P: Dataset from Pinheiro et al.[17]; J: Dataset from Johansen[16]; W: Dataset from Wilfret[24]; Pan: Dataset from Pan et al.[25]; L: Dataset from Li et al.[26]; R: Dataset from Ren[27]; M: Dataset in this study. The hybridization results of 11 species with complex reticulate evolutionary relationships were compared to those of 64 species (all hybridization combinations). The hybridization results showed (Fig. 4) that the interspecific compatibility (52.50%) of species with complex reticulate evolutionary relationships was higher than that of all hybridization combinations (24.05%). Among 16 comparison results, nine comparison results (SI × SI/SC; SI as pollen donor; SI as pollen receptor; SC as pollen donor; SI/SC × SI; SI/SC × SC; SI/SC as pollen donor; SI/SC as pollen receptor; mean value) showed that the rate of interspecific compatibility between the 11 species was higher than that of the 64 species; three comparison results (SC × SI/SC; SI/SC × SI/SC; SC as pollen receptor) showed that the rate of interspecific compatibility of the 64 species was higher than that of the 11 species; and four comparison results (SI × SI; SI × SC; SC × SC; SC × SI) could not be compared due to the lack of data on hybridization combinations of the 11 species.

Figure 4.

Interspecific compatibility comparison of 11 Dendrobium species and 64 Dendrobium species. The blue column represents the rate of interspecific compatibility of 11 Dendrobium species, and the orange column represents the rate of interspecific compatibility of 64 Dendrobium species.

To further explore the relationship between phylogenetic relationship and interspecific compatibility, based on nuclear sequence information and chloroplast genome sequence information, the reticulate evolutionary relationship of 11 Dendrobium species was reconstructed. The results of nuclear ITS and chloroplast genome (Fig. 5) showed that there were complex reticulate evolutionary relationships among the 11 Dendrobium species: D. bensoniae and D. crystallinum were clustered together, with a reticulate evolutionary relationship between species, and the hybridization results showed that both reciprocal crosses were compatible; D. moniliforme, D. huoshanense, D. hercoglossum, D. officinale, and D. nobile were clustered on one branch, with a complex evolutionary relationship, and the hybridization results showed that D. officinale was compatible with D. moniliforme, D. huoshanense, D. hercoglossum, and D. nobile; while D. crystallinum and D. bensoniae were far apart from D. officinale, and the hybridization results showed incompatibility.

-

This experiment compiled 623 hybrid combinations of 64 species of Dendrobium, including 1763 hybrid experimental data, and calculated that the rate of interspecific compatibility of Dendrobium was 24.05%. This result represents the largest and most detailed hybridization experiment result in Dendrobium to date, with the parents covering various phylogenetic branches of the genus, making it highly representative. Additionally, the proportion of SI parents in hybridization parents (SI: 59.38%; SC: 23.44%; SI/SC: 17.19%) is also similar to the SI proportion in Dendrobium (SI: 55.64%; SC: 29.03%; SI/SC: 15.32%), thus adequately representing the hybrid compatibility situation in the Dendrobium.

The unique SI ratio and reticulate evolution relationship in Dendrobium contribute to the interspecific compatibility of extant species

-

Consistent with the results of Pinheiro et al.[17], our results also show that Dendrobium has a high proportion of SI species and a certain proportion of SI/SC species. Interspecific compatibility in Dendrobium follows the SI × SC rule, with the rate of interspecific compatibility between SC species higher than that of SI species. By summarizing more detailed and extensive research on SI in Dendrobium, it was found that the proportion of SI/SC species is 15.32%, higher than the results of Pinheiro et al.[17] (7.9%). SI/SC and SC species have a similar impact on hybridization in the Dendrobium, with both having a higher rate of interspecific compatibility than SI species when used as hybrid parents. Furthermore, Dendrobium exhibits multiple SI phenotypes, indicating the possible existence of multiple SI molecular mechanisms[13,14]. These different molecular mechanisms might be similar to known SI mechanisms[29−32]. Furthermore, based on the molecular understanding of SI and interspecific compatibility[33], is it possible that species with different SI molecular mechanisms may have varying effects on interspecific compatibility, and further studies are needed?

Wang et al.[15] discovered many ancient hybridization events within Dendrobium based on phylogenetic studies, which is a significant factor contributing to the reticulate evolution relationship. However, the impact of the reticulate evolution relationship in Dendrobium on the hybridization of extant species remains poorly understood. The results show that the rate of interspecific compatibility (52.50%) among species with complex reticulate evolution relationships in Dendrobium is higher than the rate of all interspecific compatibility (24.05%). Previous studies have mainly focused on confirming the reticulate evolution relationship among extant species caused by ancient hybridization events. In this study, it was further found that within the confirmed groups of reticulate evolution relationships, the rate of interspecific compatibility is higher, indicating the potential for the evolution of new species through recurrent hybridization. This is achieved by the inference of the reticulate evolution relationships of extant species caused by ancient hybridization events, ultimately leading to the deduction of the high rate of interspecific compatibility of extant species.

Hybridization may promote the high species richness of Dendrobium, even in all orchids

-

The pattern of hybridization promoting species richness in Dendrobium may be common among orchids. Firstly, Dendrobium has a high proportion of SI species, which require outcrossing to reproduce. There is a positive correlation between outcrossing and high levels of hybridization in vascular plants[5]. Hence, it is hypothesized that the high proportion of SI species in Dendrobium may be one of the key reasons for its high rate of interspecific compatibility. Similar to Dendrobium, genera with SI phenotypes are concentrated in the subfamily Epidendroideae[14], comprising approximately 80% of Orchidaceae species[34,35], and they are among the groups with the highest species richness in the family, such as Dendrobiinae (i.e., Dendrobium)[16], Pleurothallidinae[36], Oncidiinae[37,38], Malaxidinae[39,40] , Laeliinae[37,41], Aeridinae[42], Angraecinae[42], and Neottieae (i.e., Epipactis)[37], indicating that SI plays a role in promoting species richness in Orchidaceae. Furthermore, the perennial characteristic of Dendrobium may also provide some support for hybridization. Hybridization may result in individuals with reduced reproductive fitness, but long lifespans (perennial) may allow hybrid individuals with partial sterility to still have high levels of lifetime fitness, as a small number of viable seeds produced over multiple seasons can result in many offspring over time[43]. Most Orchidaceae species are perennial plants[44], which may be one of the reasons that Orchidaceae has a high tendency for hybridization[6]. Finally, numerous ancient hybridization events have been discovered in Dendrobium, leading to complex reticulate evolutionary relationships[15], and Orchidaceae is the family with the highest tendency for ancient hybridization[6], suggesting that complex reticulate evolutionary relationships may be common within the family. For example, Paphiopedilum, one of the large genera in Orchidaceae, has been reported to have hybrid species and reticulate evolutionary relationships[1], indicating that hybridization plays an important role in the formation of orchid species. In conclusion, hybridization may be one of the key factors driving the high species richness in Orchidaceae.

-

This study elucidated the distribution patterns of SI in Dendrobium species and revealed their intricate relationships with phylogenetic divergence and interspecific compatibility. The findings demonstrate distinct distribution trends among widely dispersed SI, SC, and SI/SC species. Furthermore, it was found that reticulate evolutionary networks significantly enhance interspecific compatibility within this genus. These insights advance our understanding of phylogenetic relationships and diversification mechanisms in Dendrobium while providing critical information about hybridization potentials and evolutionary trajectories. The obtained knowledge holds significant implications for strategic crossbreeding programs in Dendrobium and other orchid taxa, as well as for formulating effective conservation strategies to preserve orchid biodiversity.

We thank Yi-Bo Luo (State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, China) for providing valuable opinions and suggestions for this study. This work was supported by the Young Talent Project of the Hebei Agricultural University Foundation (Grant No. YJ201848), the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (Grant No. C2022204214), the Science Research Project of the Hebei Education Department (Grant No. QN2024240), and the Yunnan Seed Laboratory Project, Rapid propagation and Quality Control Technology of Healthy Seed (Grant No. 202205AR070001).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Niu SC, Xiang DY; data collection: Niu SC, Huang WQ, Zheng KY, Li XR, Su X, Hao LH, Zhang YP; analysis and interpretation of results: Duan SD, Huang WQ, Zheng KY, Li XR, Liu Y, Chen DF; draft manuscript preparation: Duan SD, Huang WQ, Rashid MAR, Niu SC, Xiang DY. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

accompanies this paper at (https://www.maxapress.com/article/doi/10.48130/tp-0025-0019)

-

Received 11 December 2024; Accepted 28 May 2025; Published online 30 June 2025

-

The self-incompatibility rate in Dendrobium ranged from 55.64% to 70.96%.

SI, SC, and SI/SC species were widely distributed in the Dendrobium phylogenetic tree.

Interspecific hybridization of Dendrobium species followed the SI x SC rule, and the rate of interspecific compatibility with self-compatible (SC) and SI/SC species as parents, was higher than the results with the SI species as parents.

Interspecific compatibility was higher between species with reticulate evolutionary relationships.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Shan-De Duan, Wang-Qi Huang

- Supplementary Table S1 Chloroplast genome GenBank number in phylogenetic tree.

- Supplementary Table S2 Nuclear ITS GenBank number in phylogenetic tree.

- Supplementary Table S3 Summary of interspecific compatibility results of 64 species in Dendrobium.

- Supplementary Table S4 The self-incompatibility of parents of Dendrobium hybrid combinations.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Based on nuclear ITS, the phylogenetic tree of 92 Dendrobium species was reconstructed by maximum likelihood method, with O. govidjoae and O. sinuatum as outgroups.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Based on nuclear ITS, the phylogenetic tree of 92 Dendrobium species was reconstructed by Bayesian method, with O. govidjoae and O. sinuatum as outgroups.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 The distribution of self-incompatibility of Dendrobium species in phylogenetic tree.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 The distribution of self-incompatibility of interspecific hybrid parents in the phylogenetic tree.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Duan SD, Huang WQ, Zheng KY, Li XR, Zhang YP, et al. 2025. Self-incompatibility and reticulate evolution contribute to interspecific compatibility of Dendrobium, a possible mechanism for promoting species diversity. Tropical Plants 4: e023 doi: 10.48130/tp-0025-0019

Self-incompatibility and reticulate evolution contribute to interspecific compatibility of Dendrobium, a possible mechanism for promoting species diversity

- Received: 11 December 2024

- Revised: 14 May 2025

- Accepted: 28 May 2025

- Published online: 30 June 2025

Abstract: Hybridization plays a crucial role not only in the origin and evolution of species but also in the formation of species diversity. Dendrobium is one of the largest genera in the Orchidaceae, exhibiting both a high rate of self-incompatibility (SI) and interspecific compatibility. However, there have been few reports on the distribution pattern of the SI and interspecific compatibility in Dendrobium and their relationship to the reticular evolution of Dendrobium. In this study, self- and cross-pollination experiments were conducted on selected Dendrobium species, and all previously reported data were integrated. The phylogenetic relationships of Dendrobium species were analyzed by using nuclear ITS sequence information and all published complete chloroplast genome data. SI and reticulate evolution were also studied for verification of their relationship to interspecific compatibility. The results showed that the SI rate in Dendrobium ranged from 55.64% to 70.96%, and species with self-incompatibility were widely distributed within the genus. Dendrobium species followed the SI × self-compatibility (SC) rule, suggesting SI affected the interspecific compatibility in Dendrobium. Further, when SC and SI/SC species served as parents, the rate of interspecific compatibility was higher than that with SI species as parents. The rate of interspecific compatibility (52.50%) between species or groups with closer reticulate evolutionary relationships was higher than that of all hybridization combinations (24.05%). Overall, this study provides new insights into the formation of high species diversity in Dendrobium and offers theoretical guidance for further hybridization breeding.