-

Significant advancements have been made in the application of diverse transgenic technologies to crop species, encompassing large-scale commercialization[1]. Regardless of the prevailing trends in the evolution of transgenic technology, methodologies for genetic transformation should advance in the direction of simplicity, operational ease, and breeding convenience[2]. However, the majority of established techniques based on Agrobacterium-mediation and direct-DNA-transfer entail procedures that are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and costly[3]. These include extensive in vitro cultivation, the establishment of conditions necessary for the regeneration of protoplasts or explants, and use of expensive apparatus such as particle guns[4]. Pollen grains, which serve as excellent vehicles for the introduction of foreign genes into the germline, are abundant and readily manipulated[5,6]. However, the efficacy of employing pollen as a vector to produce transgenic plants is notably low, particularly for trees[7]. The lack of efficacy is primarily due to the formation of two distinct wall layers during pollen development[8,9], which hinders the integration of foreign genes into pollen[10], and presents the initial and most challenging phase of utilizing pollen as a vector for creating transgenic plants. Consequently, researchers have devised 12 distinct methods for inserting foreign genes into the pollen of crops[5]. Currently, only the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana can efficiently introduce foreign genes into pollen via the floral dip method[11]. Electroporation is used to transfer aquaporin genes into protoplasts of lily pollen for validating gene function[12]. By leveraging the large germination pores in lily (Lilium longiflorum) pollen, nanomagnetic technology is employed for pollen transgenesis[13]. Although Nicotiana tabacum, with its well-characterized genome, is commonly used as a transgenic model for gene function verification, its pollen-mediated genetic transformation is currently limited to electroporation approaches[14]. The development of transformation systems for tree species lags behind that for other crop species, and an efficient system for many tree species has not yet been established. In addition, the complexity and diversity inherent in tree genomes complicate the process of generating transgenic plants within arboreal species. The phenomenon is known as xenia and has also been observed in Rosaceae fruit trees[15]. It was recently shown that male parent-derived MdACO3-GFP mRNAs can move from seeds to apple flesh to promote fruit ripening. This observation explains the molecular mechanisms underlying xenia[16]. The development of a transgenic system for tree breeding is of utmost importance[7]. In this research, we identified the widely cultivated 'Wonhwang' pear variety from a vast array of pear cultivars, which facilitates the introduction of foreign genes into its pollen.

-

The pear blossoms were in full bloom, and their pollen was meticulously harvested. Subsequently, the collected pollen was preserved at a temperature of −20 °C.

Plasmid

-

We used two types of gene vectors. The 35S::GFP plasmid was a generous gift from the State Key Laboratory of Crop Genetics and Germplasm Enhancement at Nanjing Agricultural University (Nanjing, China). The second type of gene vector was the pLAT52::GFP plasmid. The pollen-specific LAT52 promoter was employed to substitute the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter within the original 35S::GFP plasmid.

Methods

Pollen germination—a test of pollen viability

-

Pollen grains were germinated in medium (BK) containing 0.55 mM Ca(NO3)2, 1.6 mM H3BO3, 1.6 mM MgSO4, 1 mM KNO3, 440 mM sucrose, and 5 mM 5,2-(N-morpholino) ethane sulfonic acid hydrate (MES), and the pH was adjusted to 6.0 with Tris.

Arabidopsis pollen tubes

-

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) plants were cultivated at light intensities ranging from 120−150 µmol/m2/s over a 12-h daily light period at a temperature of 22 ± 2 °C. Newly opened Arabidopsis thaliana flowers were picked, and pollen grains were dusted onto the medium. The pollen was cultured for 6 h at 25 °C on a medium supplemented with 18% (w/v) sucrose, 0.01% (w/v) H3BO3, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM Ca(NO3)2, and 1 mM MgSO4 at pH 7.0 (KOH).

Electron microscopy of pollen

-

The dried pollen grains were fixed onto a metal sample stand using a double-sided conductive adhesive, and subsequently, the samples underwent low vacuum sputtering for 90 s to be coated with gold. The pollen grains were observed under a scanning electron microscope (ZEISS Merlin Compact, Germany), the acceleration voltage was at 3.0 kV. ImageJ software was used to add pseudo color to pollen images.

Introducing genes into pollen through low-pressure infiltration

-

The stored pollen was removed from the −20 °C refrigerator and allowed to reach room temperature for 1 h. Subsequently, 0.05 g of pollen was weighed and transformed to a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube containing 0.5 mL of BK medium. An appropriate quantity of plasmid, harboring the target gene, was then introduced into the centrifuge tube (the optimal concentration being 10 ng/µL). The mixture was subsequently shaken and homogenized.

The centrifuge tube was placed on ice with the lid open, placed in a vacuum drying oven, and subjected to low pressure infiltration at −80 Pa for 4 min. The centrifuge tube was centrifuged at a low temperature (4 °C) for 5 min at 12,000 rpm to remove the supernatant.

After the above processes, the pollen was cultured in the dark at 28 °C for 2.5 h or pollinated.

Fluorescence detection

-

The transgenic pollen was cultured for 2.5 h, and the pollen tube was observed under a fluorescence microscope (EVOS Auto 2, Thermo Fisher, USA). Since the excitation light of Green Fluorescent Proteins (GFP) is 488 nm, the GFP light cube was selected. The leaves of transgenic seedlings were observed under stereo-fluorescence microscopy (SZX12, Olympus, USA).

Measurement of the total anthocyanin content in the pollen tube and leaves

-

0.05 g of pear pollen tube or 0.5 g of pear leaf were taken, and then ground in liquid nitrogen, 1 mL of the extract from the anthocyanin detection kit ws then added (Article No. G0126F, Grace Biotechnology, Suzhou City, China), extracted by shaking at 75 °C for 25 min, and then centrifuged at room temperature for 12,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was then taken for detection by ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometer (Model: UV1810, Yoke Instrument, Shanghai City, China)[17].

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR to determine gene expression

-

To estimate mRNA expression levels, qRT‒PCR analysis was performed. Total RNA was extracted from pollen and styles with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, US), and first-strand cDNA was synthesized from 2 μg of total RNA using an Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen, Netherlands). The primers for MdGH3.1 were F: CTCGGATATGGCCAAACACG and R: AGAAGGCTTGCACATAGGGT. Gene expression data were normalized to actin gene levels and are expressed as ratios to the relevant control (assigned a value of 1).

Statistical analysis

-

The data are presented as means ± standard errors of the mean (SEMs) and analyzed employing GraphPad Prism version 7.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical differences between experimental groups were assessed using the Student's t-test.

-

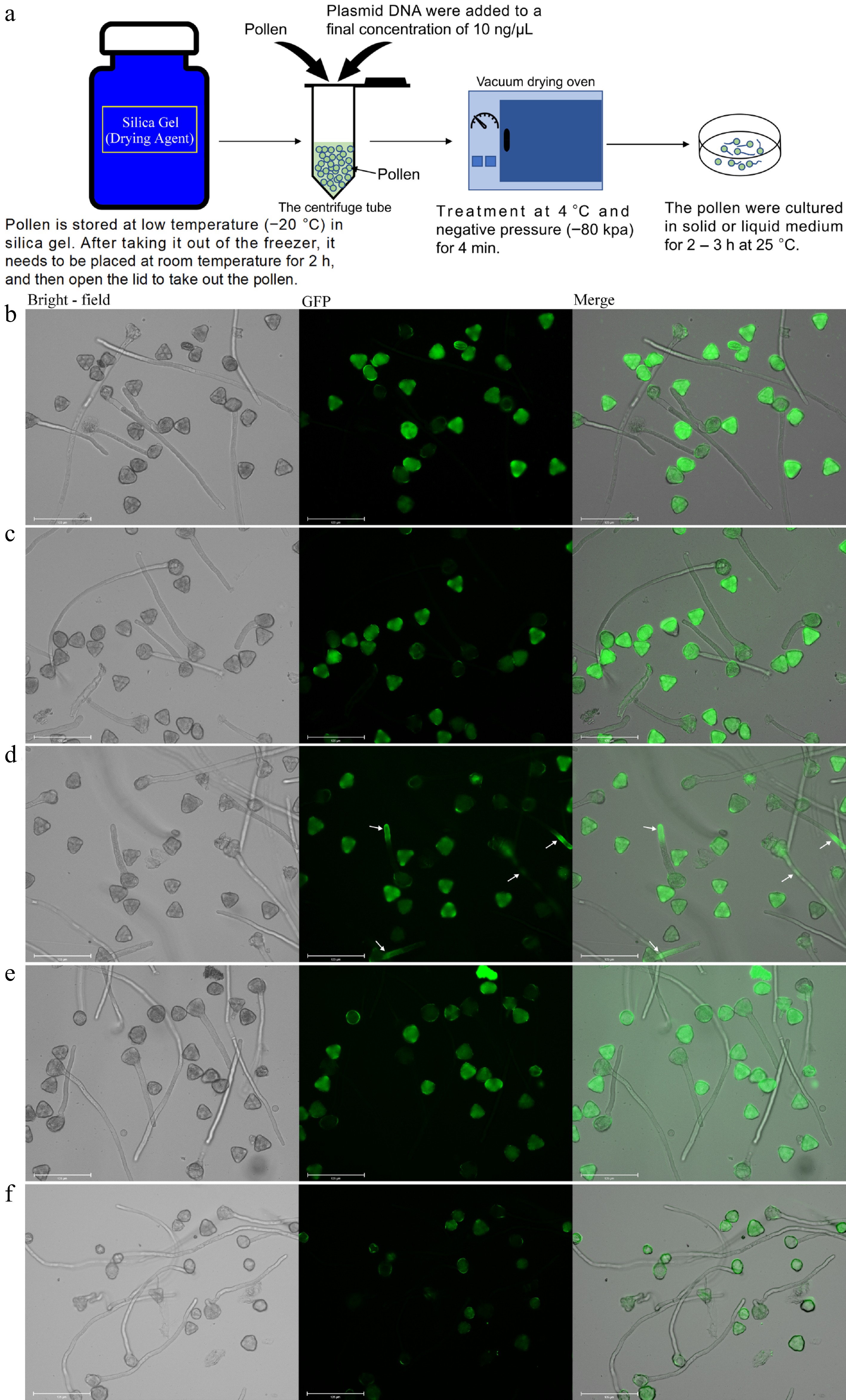

To ascertain whether foreign genes could be integrated into pollen, we employed a negative pressure infiltration technique for 4 min to introduce the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene into pollen grains. Subsequently, the pollen was cultured for 2–3 h, after which the expression of GFP in pollen tubes was evaluated (Fig. 1a). To serve as a control, the pollen tube of 'Wonhwang' pollen, which had been cultured under normal conditions, displayed no fluorescence. Only pollen grains emitted fluorescence (Fig. 1b), consistent with autofluorescence. Upon the introduction of the empty vector, the pollen tube continued to show no fluorescence (Fig. 1c). In contrast, pollen tubes transformed with GFP exhibited a distinct fluorescence (Fig. 1d). We also subjected another variety of pear, Pyrus pyrifolia 'Akitsuki', to the same treatment and observed no fluorescence in its pollen tube (Fig. 1e). Similarly, pollen tubes of Arabidopsis thaliana exhibited no fluorescence when subjected to the same treatments (Fig. 1f); and the application of negative pressure infiltration did not notably influence pollen tube growth or pollen germination rate (Supplementary Fig. S1a, b). Lat52 was used as the promoter (specific to pollen) and GFP was used as a marker gene to create a vector. This vector was subsequently introduced into 'Wonhwang' pollen. Both the pollen grains and tubes exhibited green fluorescence, whereas the control and empty vectors displayed autofluorescence only in the pollen grains but not in the tubes (Supplementary Fig. S2). These findings indicate that genes could be successfully introduced into 'Wonhwang' pollen via negative pressure infiltration and could be expressed within the pollen tube. The maximum gene introduction rate, as evidenced by the fluorescence in the pollen tubes, was 41.7% (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1.

Delivery of the GFP vector into pear pollen. Pollen culture was performed for 3 h at 25 °C. (a) The process of transforming genes into pollen by negative pressure infiltration. (b) Wild type 'Wonhwang' pollen (control). (c) The empty vector was transformed into 'Wonhwang' pollen. (d) The plasmid containing the GFP gene was transformed into 'Wonhwang' pollen. The white arrow points to where the fluorescent protein-encoding gene is expressed. (e) The plasmid containing the GFP gene was transformed into pollen of the pear cultivar 'Akitsuki'. (f) The plasmid containing the GFP gene was transformed into the pollen of Arabidopsis thaliana.

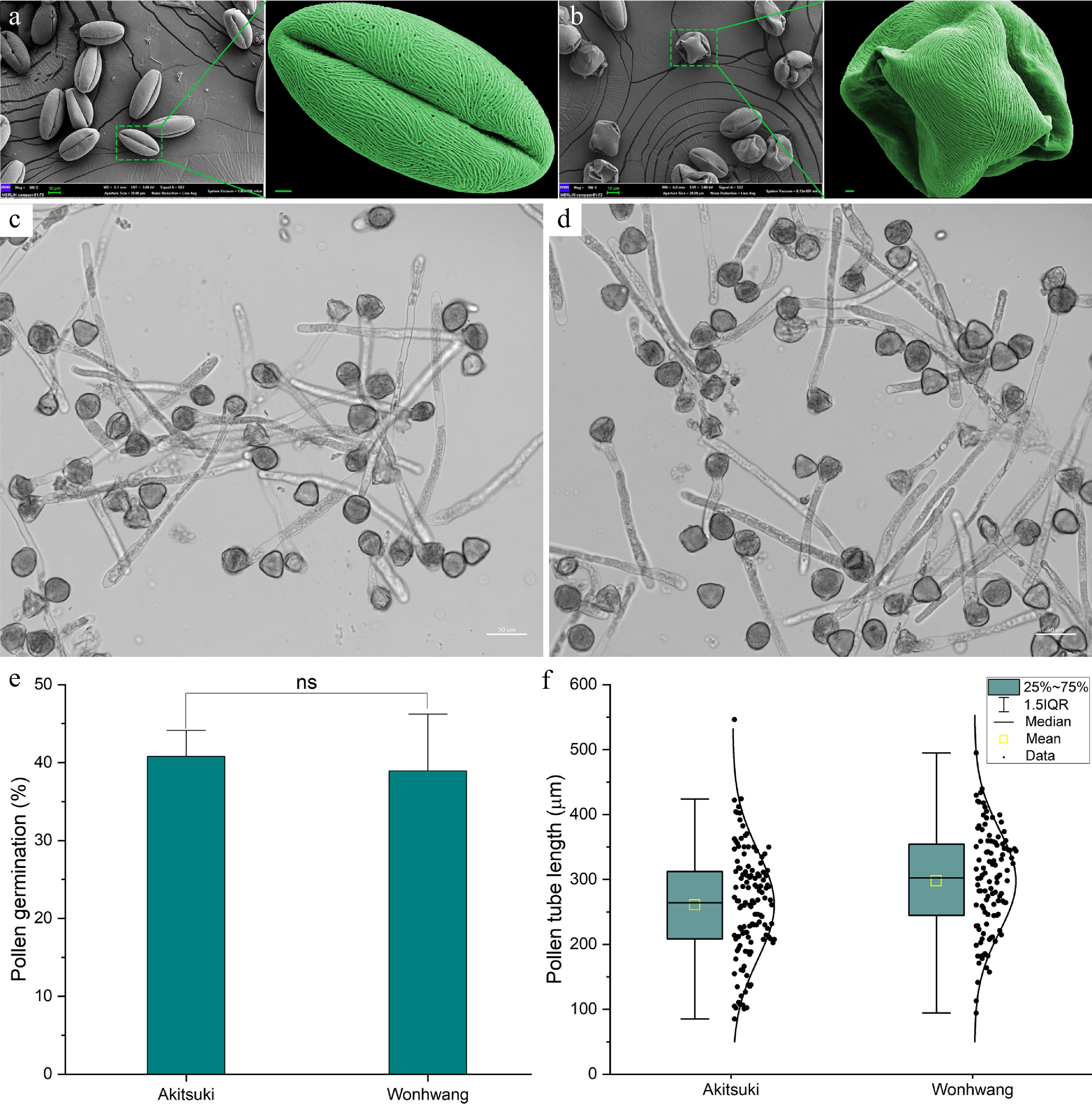

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to examine pear pollen. The normal dried pollen grains of 'Akitsuki' were observed to be prolate elliptic and tricolpate monads (Fig. 2a). The polar diameter ranged from 32 to 48 µm, while the equatorial diameter ranged from 14 to 25 µm (Supplementary Fig. S3). In contrast, the pollen of 'Wonhwang' differed significantly from that of 'Akitsuki', with numerous pollen grains displaying irregular morphologies (Fig. 2b). However, there were no notable differences in germination rate and length of the pollen tubes of 'Wonhwang' pollen compared to those of other varieties in vitro (Fig. 2c−f). In addition, we pollinated the stigma of 'Akitsuki' with pollen from 'Wonhwang'. After 72 h, we fixed the style of 'Akitsuki' and stained it with aniline blue. It was observed that Wonhwang's pollen tubes could grow in the style of 'Akitsuki' (Supplementary Fig. S4). These findings further indicate that the irregular morphology of 'Wonhwang' pollen does not compromise its viability.

Figure 2.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of pollen and in vivo pollination. (a) SEM images of dried pollen of the 'Akitsuki' cultivar. The scale bar is 2 µm. (b) SEM images of dried pollen of the 'Wonhwang' cultivar. (c) Growth of 'Akitsuki' pollen tubes. (d) Growth of 'Wonhwang' pollen tubes. (e) Comparison of pollen tube germination rates. (f) Comparison of pollen tube lengths. ns: Indicates no significant difference (p > 0.05).

GFP gene-transformed 'Wonhwang' pollen pollinated the style of 'Akitsuki' pear

-

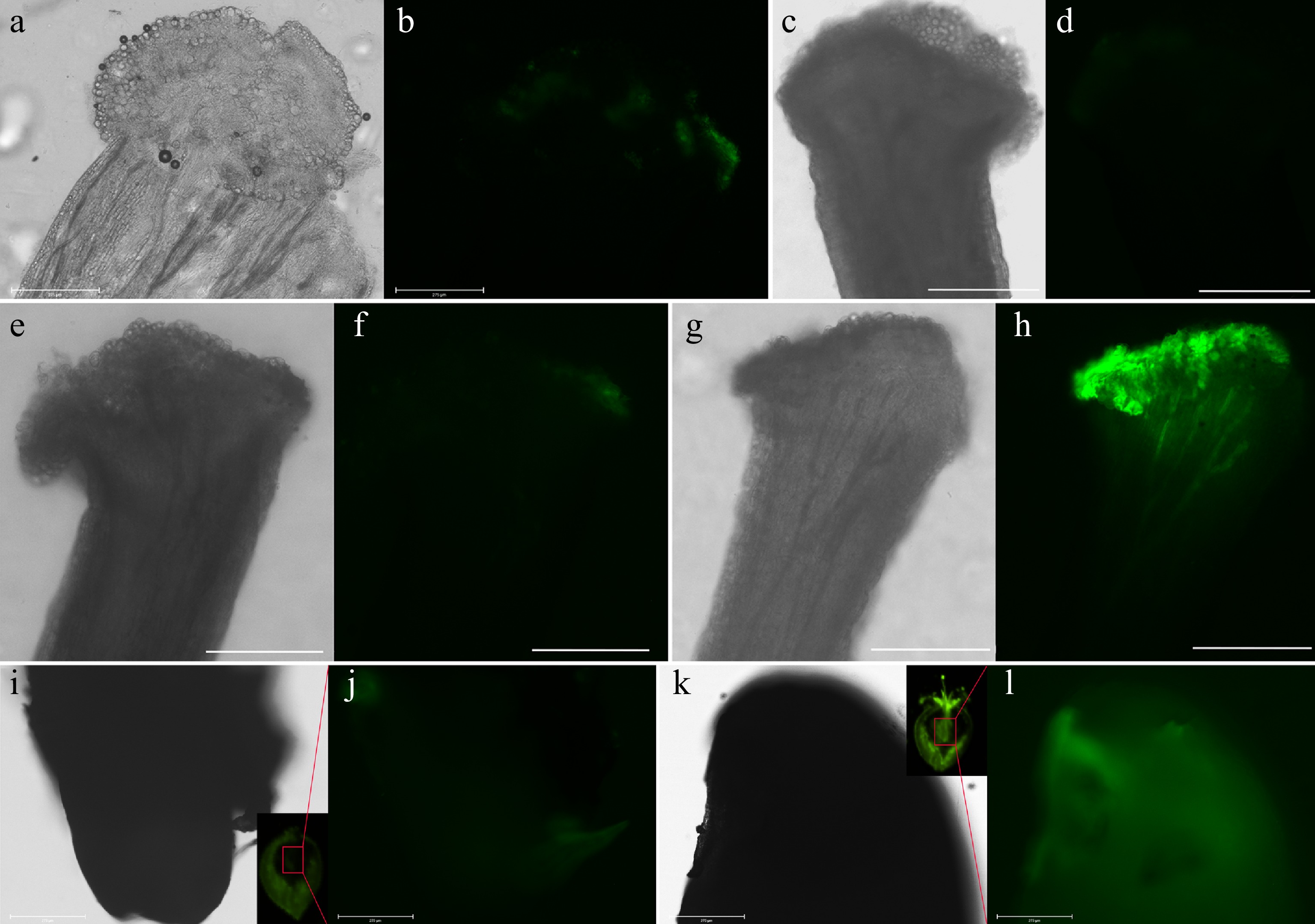

Unpollinated stigmas (Fig. 3a, b), stigmas with pollen not carrying the GFP gene (serving as controls) (Fig. 3c, d), and stigmas with pollen that had been transformed using an empty vector (Fig. 3e, f), did not display any fluorescence. Following pollination with pollen carrying the GFP gene, a distinct fluorescence was observed in the stigma (Fig. 3g, h). Fifteen days post-pollination, the young fruits were sectioned to examine the embryo. The control embryo displayed minimal fluorescence, which was attributed to autofluorescence (Fig. 3i, j), whereas the embryo that had been transformed with GFP exhibited a pronounced fluorescent signal (Fig. 3k, l). These results suggest that pollen carrying the GFP gene can complete pollination and fertilization.

Figure 3.

'Wonhwang' pollen transformed with the GFP gene pollinates the stigma of 'Akitsuki'. (a), (b) Stigma of 'Akitsuki' without pollination. (c), (d) Non-transgenic 'Wonhwang' pollen was used to pollinate a stigma of 'Akitsuki' for 30 h. The scale bar represents 275 μm. (e), (f) Wonhwang' pollen transformed with the empty vector was used to pollinate stigma of 'Akitsuki' for 30 h. The scale bar represents 275 μm. (g), (h) Stigma of 'Akitsuki' pear was pollinated with 'Wonhwang' pollen transformed with the GFP gene for 30 h. The scale bar represents 275 μm. (i), (j) Control: stigma of 'Akitsuki' pear were pollinated with 'Wonhwang' pollen without the GFP gene for 15 d. The inner image in (i) shows the cut young fruit, and the innermost seed cavity was observed by a stereo fluorescence microscope. (i) Bright field image obtained with a fluorescence microscope. (j) The GFP channel as observed with a fluorescence microscope. (k), (l) Stigma of 'Akitsuki' pear were pollinated with 'Wonhwang' pollen transformed with the GFP gene for 15 d. The inset image in (k) shows the cut young fruit, and the innermost seed cavity was observed by stereo fluorescence. (k) Bright field image obtained with a fluorescence microscope. (l) The GFP channel as observed with a fluorescence microscope.

Verification of gene overexpression

-

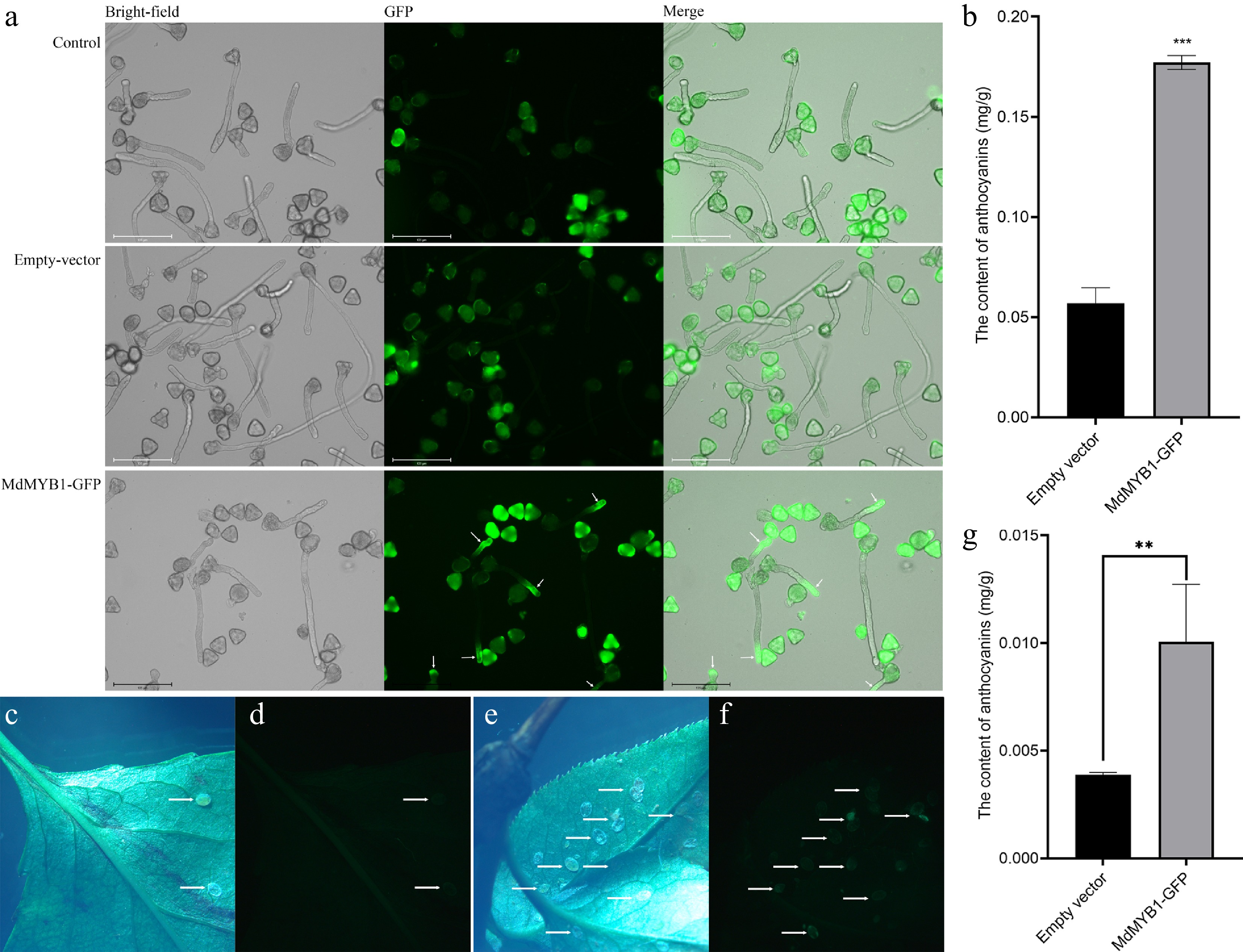

The transcription factor MdMYB1 can directly control the accumulation of anthocyanins in apples (Malus domestica) fruit[18]. This gene is localized in the nucleus at the subcellular level (Supplementary Fig. S5). We introduced a plasmid, which harbors the MdMYB1 gene coupled with a reporter gene that was also expressed in pollen tubes, into 'Wonhwang' pollen using negative pressure infiltration (Fig. 4a). Following a 3-h cultivation period, anthocyanin in the transgenic pollen was significantly increased (Fig. 4b). In the field, genetically-modified pear pollen was used for pollination of the stigma, and pear seeds were harvested at maturity. Seeds were then stratified before sowing. When seedlings had four leaves, they were collected for observation. Transgenic leaves did not fluoresce under a stereo fluorescence microscope. However, whitefly larvae were attached to the leaves. The fluorescence of larvae on MdMYB1 transgenic leaves was significantly higher than that of larvae on empty vector leaves (Fig. 4c–f). Whitefly larvae consume a substantial amount of sap from leaves[19] and accumulate it within their bodies[20], thereby increasing the concentration of fluorescent proteins[21]. Leaf anthocyanin levels were assessed during the seedling stage of pear trees. The transgenic leaves exhibited substantially higher anthocyanin content than the empty vector control leaves (Fig. 4g).

Figure 4.

The MdMYB1-GFP gene was transformed into 'Wonhwang' pollen, which was subsequently cultured on solid medium for 3 h. (a) No transgenic 'Wonhwang' pollen (control). The empty vector was transformed into 'Wonhwang' pollen (empty vector). The plasmid containing the MdMYB1-GFP gene was then transformed into 'Wonhwang' pollen (MdMYB1-GFP). The white arrow points to where the fluorescent protein-encoding gene is expressed. (b) The content of anthocyanins in pollen tubes. *** indicates significant differences at p < 0.001. The data are presented as the means ± standard errors. (c) Bright field photo of pear seedling leaves with an empty carrier, and (d) is a fluorescence photo of the same leaf. The arrow points to the larvae of the whitefly. (e) Bright field photo of transgenic pear seedling leaves, and (f) is a fluorescence photo of the same leaf. The arrow points to the larvae of the whitefly. (g) Anthocyanin content in leaves. ** indicates significant differences at p < 0.01. The data are presented as mean ± standard error.

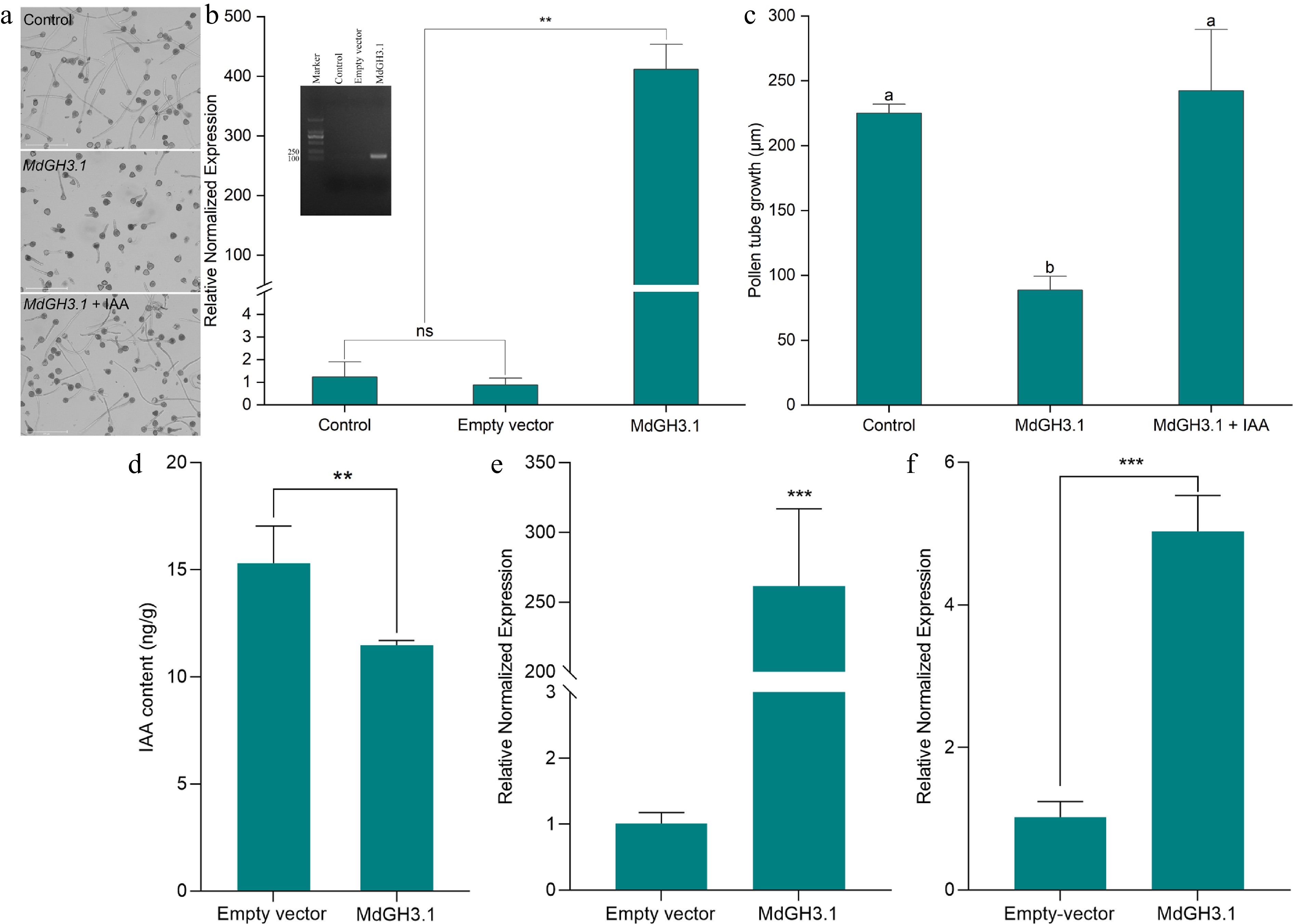

We have shown marked overexpression of the auxin response gene MdGH3.1 to be the locus of metabolic physiological disorders in apple trees[22]. This gene can suppress auxin synthesis, potentially leading to stunted plant growth[23,24]. To further explore its function, we introduced this apple gene into the pollen of 'Wonhwang' variety using negative pressure infiltration. The gene exhibited robust expression within the pollen tubes of 'Wonhwang' (Fig. 5a), and correspondingly, it arrested the growth of these pollen tubes (Fig. 5b). Growth of the pollen tube was successfully restored by the addition of auxin to the culture medium (Fig. 5c). Further studies on auxin levels within pollen tubes revealed that auxin concentration was significantly lower in transgenic pollen tubes than in the control (empty vector) (Fig. 5d). Seeds and pear seedlings from transgenic plants (MdGH3.1) were generated using pollen, and the expression of MdGH3.1, as determined by quantitative PCR, in the seeds and leaves, was significantly higher than in the control (empty vector) (Fig. 5e, f). These findings suggest that 'Wonhwang' pollen could serve as an effective vector for gene transfer and a valuable tool for verifying gene function.

Figure 5.

The MdGH3.1 gene of apple was transformed into 'Wonhwang' pollen for functional verification. (a) Pollen culture in vitro for 3 h. Pollen that was not transformed was used as a control. The MdGH3.1 gene was transformed into 'Wonhwang' pollen via negative pressure infiltration, after which the pollen was cultured on medium (GH3.1). 'Wonhwang' pollen was cultured on medium supplemented with 6 µmol/L IAA after the pollen was transformed with the MdGH3.1 gene (GH3.1 + IAA). (b) Quantitative measurement of MdGH3.1 expression in pollen tubes. The inner image shows the DNA gel electrophoresis bands after quantitative PCR. ns: No significant difference. ** p < 0.01. (c) Statistical analysis of pollen tube length. The data are presented as mean ± standard error. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). (d) Statistical analysis of IAA content in pollen tube. The data are presented as mean ± standard error. ** p < 0.01. (e) Quantitative measurement of MdGH3.1 expression in seeds. *** p < 0.001. (f) Quantitative measurement of MdGH3.1 expression in leaves. *** p < 0.001.

-

The current technique of incorporating foreign genes into pollen, which is the initial phase of creating transgenic plants using pollen as a vector, is inappropriate for fruit trees belonging to the Rosaceae family. Vacuum infiltration requires the use of fresh buds to facilitate the entry of foreign genes into pollen. However, at this stage, the pollen is not fully developed and the entire plant must be subjected to vacuum conditions throughout the process[25]. The introduction of foreign genes using ultrasonic techniques requires fresh pollen, which can reduce pollen viability. Following pollination, maize pollen treated with ultrasonication typically yields only 0.5 to 2 seeds per ear[26]. Nanomagnetic technology offers a possible alternative approach for introducing foreign genes into fresh maize[26], and cotton pollen[10], although the approach is debated for this use[27]. While Agrobacterium-mediated transformation is one of the most frequently employed techniques for gene transfer, its efficacy is low, particularly with respect to pollen transformation in fruit trees. Another method, particle gun bombardment, requires fresh pollen and costly equipment. In the case of Rosaceae fruit trees such as temperate varieties of apples and pears, the annual flowering period spans approximately seven days. Consequently, the practical application of these methods for introducing foreign genes into pollen is challenging. This study demonstrated that the pear cultivar 'Wonhwang', possesses pollen that can introduce exogenous genes and express them within the pollen tube under conditions of negative pressure (−80 kPa). Transgenic fluorescent labeling has been used to visually confirm the introduction and expression of these genes in the pollen tube[28]. Using fluorescence microscopy, we demonstrated that control and transgenic pollen grains displayed fluorescence; however, fluorescence was only observed in the transgenic pollen tubes. Fluorescence in pollen grains is likely due to autofluorescence, primarily resulting from proteins, phenolic compounds, and flavonoids present in the spore wall (encompassing both the inner and outer layers)[29]. By exploiting the unique fluorescence properties of different species of pollen grains at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and integrating multidisciplinary technologies such as flow cytometry, fluorescence microscopy, and deep learning, rapid identification of pollen species can be accomplished[29]. For example, the introduction of the Lat52:STIG1-mRFP gene into tomatoes resulted in fluorescence in pollen tubes and pollen grains, whereas in the wild type, fluorescence was limited to the pollen grains, thus verifying successful gene transfer into tomato pollen[29]. The fluorescence in the pollen tubes was a result of mRFP expression, not autofluorescence. Similarly, the transient introduction of the GFP gene into tobacco pollen tubes using the gene gun method resulted in green fluorescence in pollen tubes and pollen grains[30]. Our study adds to this body of research, successfully demonstrating the introduction and expression of exogenous genes in 'Wonhwang' pollen tubes using the negative pressure method.

Currently, verification of gene function in fruit trees entails the introduction of genes into herbaceous plants, including Arabidopsis, tobacco, and tomatoes. These plants differ significantly from Rosaceae fruit trees in terms of their biological traits and they have a longer life cycle. We showed that pollen tubes of pear trees proliferate rapidly, initiating germination within 30 min. Pollen from the 'Wonhwang' cultivar can be harnessed using the transgenic technique outlined in this study, for the expedited validation of gene function in fruit trees.

Given that the most valued pear varieties exhibit high levels of heterozygosity and that crossbreeding results in significant offspring variation, employing the conventional method to select new genotypes is time-consuming and costly[31]. Thus, the method used in our study holds promise for enhancing fruit tree breeding. The 'Wonhwang' cultivar possesses an S genotype denoted as S3S12, which allows for cross-pollination with any pear variety lacking both S3 and S12 genotypes. Pollen from 'Wonhwang' can efficiently transmit the desired gene to pear seeds, potentially overcoming certain constraints inherent in conventional breeding methods and enhancing efficacy of the selection processes.

-

The negative pressure infiltration technique enables rapid transformation of foreign genes into 'Wonhwang' pollen (within 4 min) and their subsequent expression. This method eliminates the need for plasmid transfer to Agrobacterium and subsequent plant infection by Agrobacterium, which requires only the plasmid. This approach reduces the duration and streamlines the process of preparing Agrobacterium. Introducing exogenous genes into the pollen of this pear variety can be achieved without the need for costly equipment, instead relying on affordable vacuum instruments. The technique does not require fresh pollen; instead, it allows the use of pollen preserved at low temperatures and dried over extended periods. This makes it an especially suitable method for fruit trees, which only produce their fruit annually. Furthermore, this variety of pear is currently the most widely cultivated worldwide, making pollen readily available. Additionally, the plasmid penetrated the pollen of this variety without the need for negative pressure infiltration, although the level of gene expression was lower than that achieved with negative pressure infiltration (Supplementary Fig. S6). Given that variations within one species can often predict similar variabilities in closely-related species[32], it is reasonable to anticipate that pollen capable of easily transforming genes may also be found in other members of the Rosaceae family.

Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Project (CXGC2024B09), and Taishan Scholar Foundation of Shandong Province (tstp20221134). We thank Professor Juyou Wu of Nanjing Agricultural University for providing the GFP plasmid, Professor Xiaofei Wang of Shandong Agricultural University for providing the MdMYB1-GFP plasmid, and Wailiang Liu of the Laiyang Agricultural Technology Extension Center for providing pollen and for pollination.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Qu H, Liu W; performing the experiments: Song Q, Wang L, Zhang Y; data analysis: Qu H; writing the manuscript and figures preparation: Qu H. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Count the number of genes introduced into pollen tubes.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 The effect of negative pressure infiltration on pollen tube growth and germination rate.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 The Lat52:: MVenus gene was transformed into 'Wonhwang' pollen, which was subsequently cultured on solid medium for 3 h.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Scanning electron microscopy was used for pollen observation.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Pollinated style stained with aniline blue.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 Subcellular localization of the MdMYB1 transcription factor in Nicotiana benthamiana epidermal cells.

- Supplementary Fig. S6 A plasmid containing Gene8941 was transformed into 'Wonhuwang' pollen without negative pressure infiltration.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published byMaximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This articleis an open access article distributed under Creative CommonsAttribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Song Q, Wang L, Zhang Y, Liu W, Qu H. 2025. A highly efficient transform system for pear (Pyrus pyrifolia) through gene delivery to pollen. Fruit Research 5: e026 doi: 10.48130/frures-0025-0018

A highly efficient transform system for pear (Pyrus pyrifolia) through gene delivery to pollen

- Received: 05 January 2025

- Revised: 17 March 2025

- Accepted: 02 April 2025

- Published online: 03 July 2025

Abstract: Utilizing pollen as a transgenic vector in agriculture has been markedly unsuccessful, particularly for fruit trees of the Rosaceae family. We chose a widely cultivated pear variety, 'Wonhwang' (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai. cv. Wonhwang), which has been successfully used to transfer genes into mature pollen within just 4 min under negative pressure (−80 kPa). Despite irregular pollen morphology, the viability of this pear variety remained unaffected. Pollen carrying the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene can complete pollination and fertilization, and the GFP gene was expressed in embryos. Furthermore, apple genes transformed into pollen can be expressed in the pollen tube, allowing verification of gene function. Transformed genes can also be expressed in seeds and seedlings. The most significant advantage of this method is that it does not require fresh pollen. This technique is the simplest and fastest reported transgenic method for transforming genes into pollen.

-

Key words:

- Green fluorescent protein /

- Pear /

- Pollen /

- Transgenic vector