-

Diabetic retinopathy (DR), as one of the serious complications of diabetes, has been the main cause of vision loss in adults, which affects the quality of life in DR patients and wastes social, and medical resources seriously[1]. Most previous research regarded DR as a microvascular disease[2]. However, increasing evidence has identified that the inflammatory response induced by high glucose and retinal neurodegeneration caused by the local hypoxia environment has been found before the angiogenesis disorder, which has a vital effect on exacerbating retinal pathologic angiogenesis[3,4]. A majority of studies only focused on the stage of DR in which retinal structure has changed, while the recognition and treatment of the early stage of DR need to be improved[5,6]. Laboratory and clinical evidence showed that inflammation and neurodegeneration play a prominent role in early DR progression, and there are not only common initiating factors but also interactions between them[7]. Firstly, this study briefly reviews and compares the current research status, clinical detections, and treatment strategies of DR. Secondly, based on a large number of studies, it was found that early inflammation and neurodegeneration have become key mechanisms in promoting the progression of DR before the appearance of pathological neovascularization in the retina. It was further pointed out that a complex interaction exists between them. At last, the anti-inflammatory and anti-neurodegenerative therapies in DR were summarized, and it was indicated that early inflammation and neurodegeneration of patients with DR should be taken more seriously.

-

DR is a typical ocular microvascular complication of diabetes, accounting for almost one-third of people suffering from diabetes[2]. With the constant change of lifestyle, the prevalence of DR is positively correlated with the duration of diabetes. Some DR patients will develop diabetic macular edema (DME) characterized by exudation and edema existing in the macular area of the retina, or proliferative DR (PDR) accompanied by angiogenesis in the retina[8]. PDR is the main eye condition in people with type 1 diabetes, while DME is more common in type 2 diabetes[9]. The role of pathogenic factors such as advanced glycation end products (AGEs), activation of polyol pathways, hyperglycemia, and reactive oxygen species have been widely recognized[10]. Clinical identification of DR mostly comes from microangiopathy observed under a fundus microscope, such as spot-shaped bleeding, microaneurysm, exudation area, and so on, which represents a progressive stage of DR with retinal structural changes, and there is usually a decrease in therapeutic effectiveness[11]. Therefore, early identifications and treatments are needed to prevent visual loss caused by DR[10].

The stages of DR progression

-

Classification of DR is based on the presence or absence of neovascularization in the retina, divided into two major types: non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) and PDR. The disease progresses through a sequential natural course from the non-proliferative stage to the proliferative stage. Within the non-proliferative stage, lesions are further subclassified into mild, moderate, and severe grades according to severity, whereas the proliferative stage is divided into early and high-risk phases. Visual impairment is predominantly attributed to two advanced complications: DME and PDR. Macular edema is categorized into centrally involved and non-centrally involved types based on lesion location, with the former posing a greater visual threat due to the involvement of the macular foveal region[1,12].

Mechanisms of progression in DR

-

The cause of DR is combined with the effects of hyperglycemia, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, glycated hemoglobin, pregnancy, family history of DR, and other factors[11,13−18]. Various biochemical pathways are involved in the pathogenesis of DR. Current studies have identified the pathophysiological characteristics of DR as neovascularization, inflammatory response, and retinal neurodegeneration, which are based on oxidative stress theory[19−22].

Neovascularization is the most characteristic pathophysiological manifestation of DR in clinical practice[15]. Changes in the blood-retinal barrier function affect angiogenesis regulation, damage the neurovascular coupling, and promote the secretions of angiogenesis regulatory factors, such as VEGF, angiogenin (Ang), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and so on[23−25]. High glucose-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress result in localized retinal hypoxia. Under these hypoxic conditions, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α accumulates stably and upregulates VEGF and Ang-2, thereby driving pathological neovascularization and concurrently compromising the integrity of the blood-retinal barrier[26,27]. VEGF is a pivotal regulatory factor of retinal neovascularization in DR[28]. After binding to VEGFR, VEGF induces receptor phosphorylation, which activates mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways, resulting in increased mRNA expression of plasma preenzyme activator (PA) and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1)[29]. VEGF also regulates the permeability of retinal vascular through both classical and atypical protein kinase C pathways[30−32]. Through the classical protein kinase C pathway, VEGF acts on a tight junction complex mainly composed of occludin, claudins, and zonula occludin-1, inducing the breakdown of the tight junction. In addition, VEGF regulates the phosphorylation and internalization of the adherens junction protein VE-cadherin through the atypical protein kinase C pathway. The study further revealed that PIGF, as a member of the VEGF family, is significantly upregulated in non-proliferative DR. Moreover, PIGF sustains pathological angiogenesis by activating alternative pathways, such as Flt-1[33].

Inflammation plays an important role in the pathogenesis of DR. Chronic low-grade inflammation was detected in both experimental animal models and DR patients' eyes[8]. The activation of polyol pathway and accumulation of AGEs, induced by high glucose, lead to increased reactive oxygen species (ROS), which upregulates circulating inflammatory factors, adhesion molecules, chemokines and other mediators, promoting activation of leukocytes and forms chronic retinal inflammation[34]. Compared with non-DR patients, expressions of inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, IL-6, intercellular adhesion molecules (ICAM), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) were increased in the intraocular tissues of DR Patients, which were confirmed to be correlated with the accumulation of HIF-1α and the severity of DR[35,36]. The glial cells and photoreceptors inherent in the retina have also been confirmed to be the main sources of inflammation in DR and have an amplified effect on retinal inflammation[37−39]. Besides, long-term chronic low-grade inflammation also leads to retinal microvascular occlusion, leakage, and other related changes, revealing the correlation between inflammation and angiogenesis[40].

Retinal neurodegeneration is an early event in DR. Various degrees of retinal nerve cell apoptosis can be observed in the early diabetes animal models[41,42]. Before microvascular changes in animal models, the loss of ganglion cells and decreased retinal thickness were observed, suggesting that retinal neurodegeneration may be an independent pathophysiological mechanism of DR[43,44]. Research has demonstrated that high glucose-induced HIF-1α may exacerbate retinal ganglion cell apoptosis by inhibiting the activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes in neurons, which is directly associated with neurodegenerative processes[45,46]. Glial cell activation, reactive proliferation, and nerve cell apoptosis are the main characteristics of retinal neurodegeneration[47]. Mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress-induced retinal degeneration, neuronal apoptosis, imbalance of neuroprotective factors, and neuronal dysfunction due to glutamate excitotoxicity are widely acknowledged as critical mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of retinal neurodegenerative diseases[5,48−50]. Besides, retinal neurodegeneration, as an independent event of DR, has also been shown to contribute to the production of inflammatory responses and the disturbance of microcirculation[51]. For instance, studies have shown that hyperglycemia can suppress the neuroprotective effects of IGF-1, as evidenced by reduced BDNF synthesis, while simultaneously enhancing the pro-proliferative signaling of IGF-1R in vascular endothelial cells. This imbalance contributes to 'neuro-vascular decoupling'[52−54].

Current clinical strategies of DR

-

With the development of technology and equipment, different examination methods have been developed to meet the increasing demand for detection (Table 1). Fundus microscopy and fundus photography are the most common clinical tests for DR and are important means of disease diagnosis and staging. Dye-based fluorescein angiography, optical coherence tomography, and optical coherence tomography angiography show different advantages in the diagnosis of DR[55,56]. Early abnormalities of the neural retina can be detected by electroretinography (ERG) and multifocal electroretinography (mfERG)[57]. The specific selection of detection methods depends on the requirements of the clinician.

Table 1. Comparison of detection methods in DR.

Detection means Advantages Disadvantages Key findings in DR Fundus microscopy and fundus photography · Criteria for clinical diagnosis and staging · Two-dimensional image · Microaneurysm · Widely usage · Internal retinal hemorrhage · Non-invasive · Intraretinal microvascular abnormality · Optic nerve and retinal neovascularization Dye-based fluorescein angiograph · Gold standard for visualization of vascular systems · Invasive · Microaneurysm · Assess the degree of vascular leakage · Long inspection time · Vascular leakage · Find ischemic areas · The effectiveness of the dye is affected by the disease itself · Non-perfused area · The deep capillary network structure is not well shown · Optic nerve and retinal neovascularization · Allergic reactions to dyes Optical coherence tomography · Non-invasive method for obtaining cross-section images · Vascular changes can't be shown · Macular edema · Gold standard for diagnosing DME and monitoring response to treatment · Retina thinning · Vitreous macular adhesion · Intraretinal cyst · Disorder of the inner retina Optical coherence tomography angiography · Deep resolution capacity (3D visualization) · Can't display vascular leakage · Microaneurysm · Non-invasive · Not widely used · Abnormal micro-vessels in the retina · Assess and monitor DR repeatedly · Neovascularization · Quantitative analysis · Quantification of microvascular changes in the retinal capillary network · Observe the microvascular system of retinal capillary plexus and choroid capillary ERG or mfERG · Early signs of retinal dysfunction · Can't show structural changes in the retina · The amplitude and a delay in the latency of the oscillatory potentials · Predict the development of early microvascular abnormalities In practice, the identification and treatment of DR also depend on the detection of disease-related molecules in addition to imaging examination methods. With the continuous progress of molecular detection methods, new needs for more accurate identification of DR have been raised. Biomarkers are used to identify individuals at diverse stages of disease and to monitor the effectiveness of treatment. Specimens of DR patients are often derived from blood or local tissues; the latter can better reflect the specificity of organ tissues and the severity of the disease. Blood specimens are often used as a crude measure of DR because they generally reflect systemic conditions. Besides, the samples from the vitreous body, aqueous humor, and retina can reflect the pathological state of DR specifically, but they cannot be used for disease identification or routine monitoring due to the defects that the collection process often needs to be carried out at the same time as the ophthalmic surgery[58,59]. In recent years, compared with the previous methods of intraoperative methods of obtaining specimens, tear analysis can detect relatively specific biomarkers in a more non-invasive and time-saving way and is expected to become a large-scale screening method for high-risk DR groups. However, most existing molecular detection methods are still aimed at the advanced stage of DR[40,60,61]. New methods to monitor the progression of DR in a simple, non-invasive, accurate, and specific way and reliable biomarkers used to recognize early DR are needed[62]. A clinical test kit could be envisioned that can rapidly detect biomarkers of DR in both blood and tear samples for early screening and definitive diagnosis of DR.

Intensive treatments aiming at maintaining normal levels of blood glucose, blood pressure, and lipid concentration are essential to prevent or delay the progression of DR[63]. These metabolic control measures are also the basic treatment methods in the whole process of DR treatment[64]. Clinical research has demonstrated that the magnitude of reduction in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) during the initial six months of intensive therapy is a significant risk factor for early deterioration of DR. Specifically, a 10% decrease in HbA1c is associated with a 39% reduction in the risk of DR progression[7]. In addition, controlling systolic blood pressure below 130 mmHg can significantly delay the progression of DR and reduce the risk of vision loss[65]. Despite inconclusive evidence regarding the impact of statin use on the progression of DR, statins may contribute to preventing retinal arteriosclerosis and play a beneficial role in the comprehensive management of diabetes[1,66]. However, only when combined with intensive systemic control can specific local treatment measures play a much more effective therapeutic function[10,67,68]. Nowadays, treatment of DR is mainly targeted at advanced stages where structural changes have occurred, and the goal is to improve vision or avoid further vision loss. Therapeutic measures include retinal laser photocoagulation, intraocular drug injections, vitreous surgery, and gene therapy (Table 2)[8,69−80]. However, considering the current clinical efficacy, the most preferred method is intraocular drug therapy, especially the new anti-VEGF drugs.

Table 2. Comparison of current DR treatment methods.

Strategy Target New method Advantage Limitation Basic treatment Blood glucose, blood pressure, lipid concentration, and so on − Overall process The therapeutic effect is limited, and some patients still progress to PDR or DME Fundamental role Injection of medication VEGF New targeted drugs (such as Aflibercept and Faricimab) combined with PDEF, Ang, and other factors First-line therapy Applicable to late DR Delay the progression of DR Some patients have poor curative effect Improve visual acuity There is still a risk of cardiovascular complications Reduce the central retinal thickness Alleviate the resistance of monotherapy and vascular-related complications Inflammation Vitreous implants of sustained-release steroid drugs Activate glucocorticoid receptors to play a powerful anti-inflammatory effect It is suitable for DR Patients with poor anti-VEGF efficacy Reduce leukocyte stasis Second-line treatment Increased intraocular pressure, cataracts, and other adverse reactions Laser A thickened retina Pattern scanning lasers, micropulse techniques, and navigated laser system Improved accuracy Suitable for the late stage of DR, especially PDR Less collateral burn damage Risk of vision loss, and impaired night vision Gene therapy Pathogenic targets of DR, such as VEGF endostatin, angiostatin, HIF-1α, etc − Stable expression of treatment products Long-term treatment effects are still being studied Reduce complications from repeated injections Improve the structural parameters of the retina At present, the treatment of DR is mainly aimed at the stage of serious pathological changes, and the effect of anti-VEGF has not reached the expectations and even has long-term vision decline in a considerable part of the population[81]. So, the understanding and treatment of the early stages of DR needs to be improved[77,79,82−84].

-

A lot of attention worldwide has been paid to DME and PDR, which represent an aggravating stage of DR. Existing evidence has also fully elucidated the neurovascular mechanism or mechanism of microvascular disorder induced by inflammation in DR[40,51,85−93]. However, increasing research results have demonstrated that the earliest changes in retinal cellular structures and functions are consistent with hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and metabolic disorders in time. Before the microvascular changes in the retina, different degrees of early inflammation have already existed, leading to neuronal apoptosis, ganglion cell body loss, glial reactive hyperplasia, the reduction of inner retinal layer thickness and other injury manifestations, which partially affects the photoelectric conversion and signal conduction functions of the retina[94]. These changes suggest a potential link between localized retinal inflammation and neurodegenerative processes, and their occurrence is not secondary to the breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier[95].

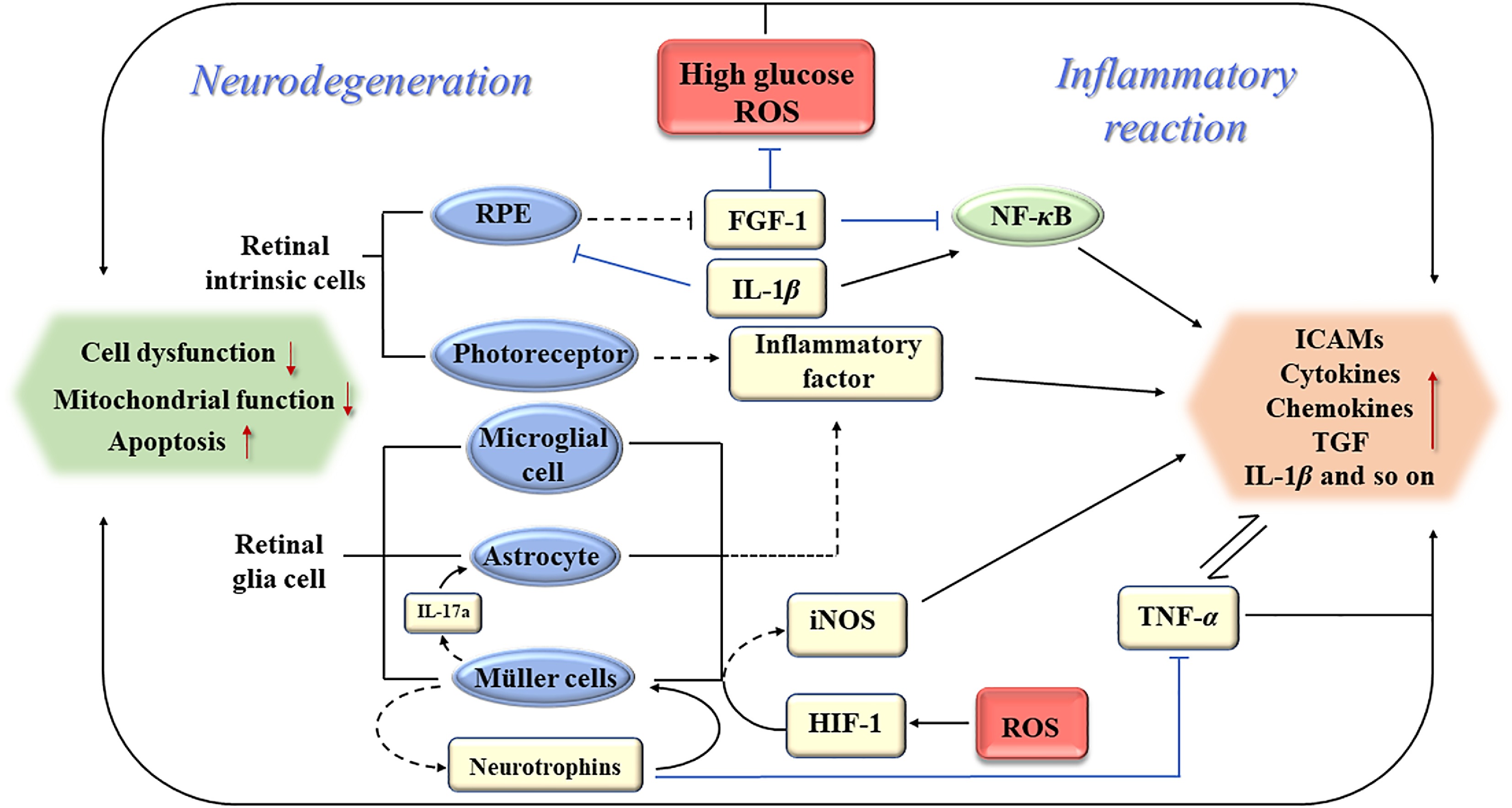

Retinal inflammation and neurodegeneration are two main pathogenic mechanisms in the early stage of DR. Sufficient attention to them will be of great significance to adjusting the treatment strategies, delaying the progression of DR and reducing the average treatment cost[77]. Nevertheless, inflammation and neurodegeneration in the retina are often regarded as two independent sections, and the treatment of early DR mainly focuses on nutritional nerve therapy or early anti-inflammatory therapy. Therefore, the outcomes of a mass of previous studies were summarized, and an interaction existing in early inflammation and neurodegeneration was found in DR (Fig. 1). The accurate comprehension of the intrinsic relationship between these two sections may be a novel direction for the integrated intervention of early DR.

Figure 1.

Schematic of association between early inflammation and neurodegeneration of DR. RPE: retinal pigment epitheliums; ROS: reactive oxygen species; FGF-1: fibroblast growth factor-1; NF-κB: translocated nuclear factor kappaB; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α; ICAMs: intercellular adhesion molecules; TGF: transforming growth factor; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase; HIF-1: hypoxia-inducible factor-1.

Co-initiating factors of retinal neurodegeneration and inflammation of DR

-

High glucose serves as the initiating factor for DR, inducing significant oxidative stress in retinal tissues via multiple metabolic pathways. Specifically, high glucose activates the polyol pathway, facilitates the accumulation of AGEs, and triggers the activation of protein kinase C (PKC), all of which contribute to an increase in ROS production[21]. The retina is a highly oxygen-consuming organ, of which pigment epithelium, photoreceptors. and other important constituent cells of the neural retina all rely on sufficient oxygen and energy to perform their biological functions. Inadequate oxygen supply was thought to be an important cause of inflammation in many organs and tissues. Many studies have confirmed that HIF-1 plays a prominent role in the inflammation of tissues and organs induced by hypoxia[96−98], which is an important hypoxic regulatory protein and is considered one of the most important biomarkers because of its high expression levels in the eyes of DR patients[99]. Hyperglycemia and hypoxia can upregulate the expression of HIF-1, and down-regulation of HIF-1 can inhibit inflammation in cell-level tests. In addition to hypoxic-induced activation of the translocated nuclear factor kappaB (NF-κB) signaling pathway promotes inflammation, the HIF-1α/JMJD1A signaling pathway has also been demonstrated to be involved in local inflammation and oxidative stress induced by hyperglycemia and hypoxia[100]. Oxidative stress, characterized by excessive ROS production, not only inflicts further damage on retinal tissue but also exacerbates the progression of retinal lesions[21].

The impairment of retinal nerve function in the early stage is mainly manifested by impaired visual acuity and chromatic acuity, and it is often ignored due to its slight appearance[101]. Current research confirms that high glucose and oxidative stress are critical factors driving neurodegeneration in DR. Hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress compromises mitochondrial function, leading to retinal neuron apoptosis and structural damage[102]. Several studies have proved neurodegeneration was an early event in DR[3,103,104]. The results of an experiment based on type 2 diabetic mouse models induced by streptozotocin presented the progressive thinning of the retina, while the results of the immunohistochemical examination on retinas of type 1 diabetic mice showed a significant absence of ganglion cells, which further supported that neurodegeneration played an indispensable role in the pathogenesis of DR[43]. In addition, Carpineto et al. revealed that the inner retinal layer was selectively thinner in patients with minimal DR than those without DR by comparing retinal structures via adopting OCT between patients without DR and patients in the very early stage of DR[105]. It especially occurred in the retinal nerve fiber layer, ganglion cell layer, and inner plexiform layer in the macula[106,107]. ERG studies demonstrate that antioxidants, such as lutein, significantly enhance visual function and mitigate neuronal pathology, underscoring the pivotal role of oxidative stress in neurodegeneration. Furthermore, oxidative stress activates the NF-κB pathway, exacerbating inflammation and causing additional damage to neurons and glial cells, thereby establishing a vicious cycle[102]. High levels of glucose and the accumulation of ROS can directly reduce retinal cell viability and affect intracellular mitochondrial activity, which may be common damage in retinal nerve function cells, because it was also observed that hyperglycemia-induced apoptosis of retinal cells in vitro, such as photoreceptors and bipolar cells[108,109]. With the morphological and functional tests in vitro, it was found that Müller cells of mouse model cultured under high glucose environment showed a higher mitochondrial rupture rate and a decrease in cell oxygen consumption, as well as a significant increase in cell apoptosis. This process may be related to thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) expression, oxidative stress injury, and mitotic dysfunction in Müller cells[110,111]. Moreover, Müller cells play a role in regulating glutamate levels in and out of cells under physiological conditions[3]. However, under pathological conditions, a large increase in glutamate leads to the internalization of Müller cells, and the increased concentration of glutamate can activate the receptors in sodium-calcium neurons and induce cell apoptosis[112]. However, the mechanism of neurodegeneration in the retina during the early stage of DR without microvascular dysfunction and whether neurodegeneration is related to other pathogenic mechanisms have not been fully elucidated.

Chronic low-grade inflammation caused by hyperglycemia and oxidative stress also plays an important role in the pathogenesis of DR, which exists in different stages of DR. In addition to the hyperosmotic environment induced by different concentrations of glucose, high levels of glucose itself have pro-inflammatory effects[113,114]. Hyperglycemia and metabolic disorders upregulate AGEs, activate the polyol pathway, and generate excessive ROS, which in turn activate inflammatory signaling pathways. This cascade leads to increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules, resulting in leukocyte adhesion and vascular leakage. Concentrations of these molecules are often in parallel with the onset of diabetes, and the researchers suggested that the increase in adhesion molecules was more likely to be a symptom of dysregulation of cellular metabolism caused by high glucose[77,113]. The increase of pro-inflammatory molecules induced leukocyte activation, migration, and stagnation, leading to blockage of the capillaries and damage to cells, which affects the structure and function of the blood-retinal barrier and amplifies the whole inflammatory process. Clinical studies have also demonstrated that the levels of inflammatory factors in the vitreous humor of diabetic patients are significantly correlated with the severity of DR. Oxidative stress can disrupt the blood-retinal barrier, facilitating the entry of inflammatory mediators into retinal tissue and thereby exacerbating local inflammatory responses. Antioxidants, such as DHA and ω-3 fatty acids, can mitigate inflammatory responses by inhibiting the expression of VEGF and IL-6, thereby improving retinal structure and function[102]. Low-grade retinal inflammation in the early stage of DR affected the function of retinal nerve cells, and this early change was also involved in the subsequent microcirculation disturbance[115].

Based on prior research findings, inflammation represents one of the key pathophysiological processes in the early stages of DR and shares a common pathogenic microenvironment with neurodegeneration. In light of existing research, both neurodegeneration and early inflammation have played critical pathogenic roles in the early stages of DR. Furthermore, the inflammatory mediators released during early inflammation and the retinal functional impairments and microenvironmental alterations caused by neurodegeneration can mutually interact and reinforce each other, significantly contributing to the early progression of DR. Consequently, it is plausible to hypothesize that a mutually reinforcing cross-talk exists between these two processes.

Neurodegeneration is involved in the early inflammation of DR

-

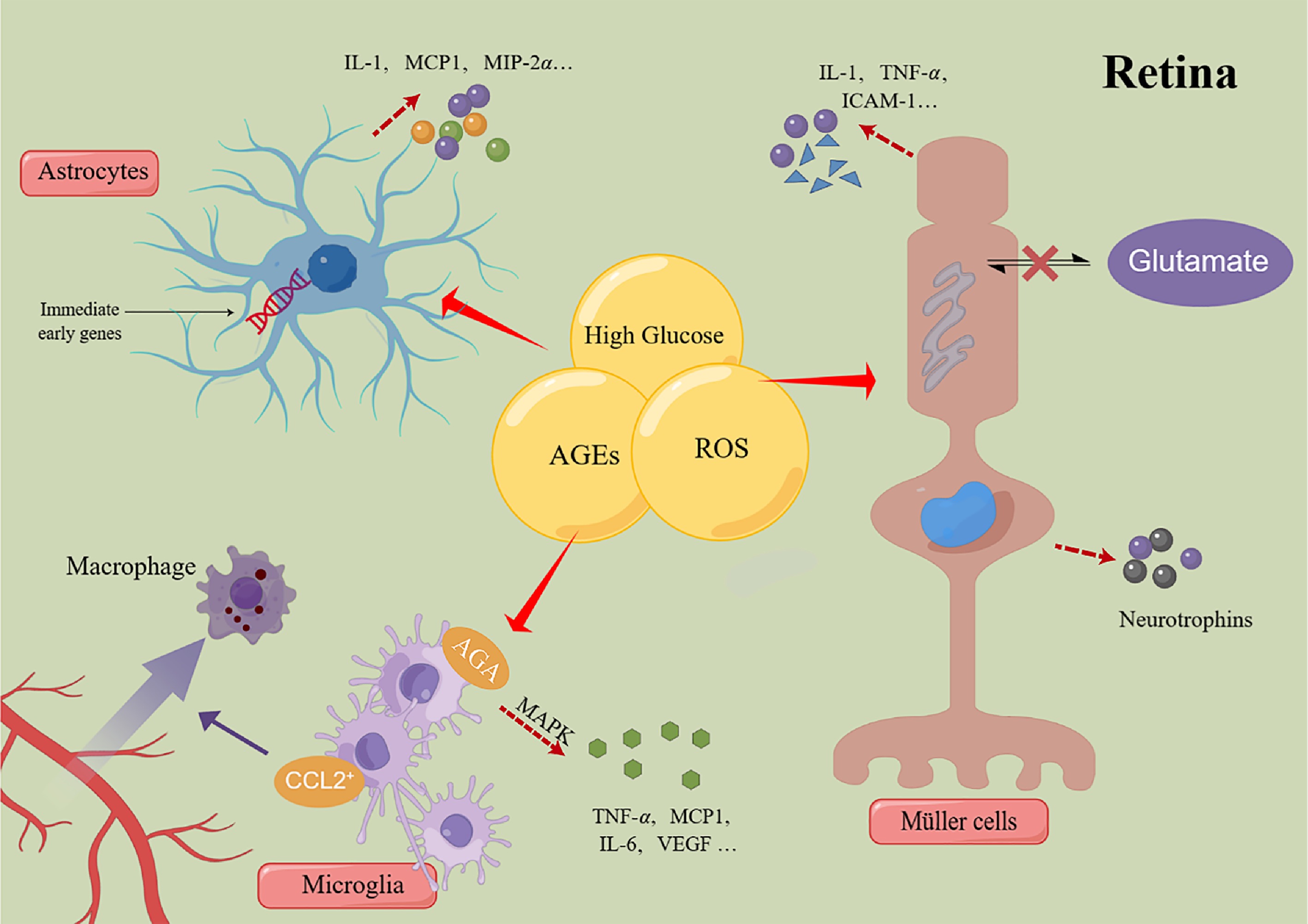

Degeneration of retinal nerve function has been shown to occur in the retinas of patients without clinical manifestations of DR via applying mode electroretinography and optical coherence tomography angiography[116]. Retinal macroglia and microglia were important sources of many pro-inflammatory factors, and retinal neurons were also involved in early local inflammation (Fig. 2), which suggested that changes in the function of the neuroretina may contribute to the early stages of retinal inflammation[116].

Figure 2.

Schematic of the mechanism of retinal glial cells regulating inflammatory response. MCP-1: monocyte chemotactic protein-1; MIP-2α: monocyte chemotactic protein-2α; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α; ICAMs: intercellular adhesion molecules; CCL2: chemokine ligand-2; AGA: amadori-glycated albumin; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; AGEs: advanced glycation end products; ROS: reactive oxygen species.

Microglia proliferated significantly in the plexiform layer in NPDR patients[117]. Under normal circumstances, microglia act as perivascular macrophages to regulate immune responses and partly perform nerve cell functions. Microglia cells are very sensitive to early damage and can produce inflammatory mediators at activation[118]. In a state of low inflammation induced by hyperglycemia, overactivated microglia cells express chemokine ligand-2 (CCL2) to induce macrophages to converge to the retina, and microglia cells can promote the secretion of TNF-α, IL-6, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and VEGF, leading to neuronal cell death, leukocyte stasis and exosmosis of inflammatory macrophages[8,119]. In addition, scholars have found that in the glial cells of the diabetic retina, there is amadori-glycated albumin (AGA)-like epitopes in the distribution area of the microglial cell. These proteins promote inflammatory response and cascade activation of MAPK and activate extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) and P38 subsequently, which leads to microglia activation and secretion of TNF-α[120]. The inflammatory mediators released by microglia stimulate the activation of adjacent Müller cells and astrocytes, thereby promoting the propagation of inflammation and exacerbating the progression of neurodegeneration.

Müller cells, as the highest proportion of glial cells in the mammalian retina, not only serve as the structural basis supporting the whole neuroretina but also establish functional and structural connections with vascular endothelial cells and retinal pigment epithelial cells. It possesses the ability to transport glucose to the retina for the production of ATP and the function of transporting energy metabolites of neurons back to the body fluid; it can also supply intermediates such as lactic acid to the retinal neurons[119]. Therefore, the functional impairment of Müller cells greatly affected the normal function of the retina and its neurons. Müller cells are the main source of inflammatory factors[121]. In addition to expressing glial cellulose acid proteins, Müller cells can secrete numerous inflammatory and growth factors when stimulated by stress including hyperglycemia, such as IL-6, and TNF-α, then induces IL-8 to cause cell death[118,122,123]. About 1/3 of the expression products of Müller cells' gene expression profile are inflammatory factors, and some of them have the effect of promoting the amplification of inflammation in themselves[123]. In addition to playing a pro-inflammatory role, glial cells, mainly Müller cells, can secrete neurotrophins in the early stimulation of inflammation, which can provide feedback to neuronal cells in the retina and, in turn, exert neuroprotective effect and reduce the expression of TNF-α to inhibit the inflammatory response of DR at the same time[124]. However, as the target of regulating DR, the effective concentration of neurotrophins to play a neuroprotective role is a difficulty at present.

Most of the astrocytes are located in the layer of nerve fibers and ganglion cells. In early diabetes, they can be reactivated by metabolic disorders and anoxic environments, amplifying the inflammatory response by activating the NF-κB signaling pathway to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and reduced astrocytes migration is observed from morphological studies[119,125,126]. Recent studies have shown that retinal astrocytes can significantly express immediate early genes after high glucose induction. The role of the latter in regulating the growth of vascular endothelial cells, signal transduction, and affecting the function of retinal nerve cells remains to be further studied[127]. Moreover, it facilitates signal exchange with neurons and microglia via gap junctions, thereby propagating the inflammatory response across cellular networks.

It is generally believed that ganglion cells and photoreceptors are highly sensitive to acute, transient, and mild hypoxic stress since they're hypermetabolic cells. Recent studies suggested that they may be an important source of oxidative stress in DR[38]. They can also produce ICAM, COX-2, and other cytokines to participate in the inflammatory process and stimulate leukocyte and endothelial cells to secrete TNF-α to regulate inflammatory response and induce nerve cell apoptosis and death in vitro[128,129]. Moreover, ROS promotes the increased production of HIF-1 in the retina, which activates the production of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in retinal glial cells. Researchers have shown that iNOS induces leukocyte adhesion and inflammation by increasing the production of nitric oxide to increase ICAM[130,131].

In addition to elevating pro-inflammatory molecules, the structural components of the neural retina also play a role in the regulation of inflammation. Fibroblast growth factor-1 (FGF-1), produced by the retinal pigment epithelium, has been confirmed to participate in blood glucose regulation and play antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects during the occurrence and development of DR. A decrease in FGF-1 was also observed in the aqueous humor of DR patients. Through the treatment aimed at FGF-1, it has been shown that the expression of ICAM-1, MCP1, and IL-1 in the retina of diabetic rats reduced significantly. It was also demonstrated at the cellular level that FGF-1 reversed the levels of peroxide products in ARPE-19 cells (a human retinal pigment epithelial cell line) induced by high glucose levels. FGF-1 also inhibited the activation of NF-κB and reduced the cascade of oxidative stress and inflammation signals in retinal tissue[114]. FGF-1 was previously reported to expand retinal blood vessels through NO pathway, but the level of FGF-1 measured in the aqueous humor of DR patients was lower than the normal condition, which may be related to the hemodynamic disorder of the retina in the early stage of DR[132]. The PIGF secreted by RPE leads to the release of inflammatory factors and drives retinal inflammation independently of VEGF[133]. These mechanisms may partly account for the limited efficacy of anti-VEGF treatments.

In summary, early neuroinflammation in DR represents a dynamic process that is initiated by neuronal damage, amplified through glial cell activation, and sustained by the cross-talk of inflammatory mediators. Potential early intervention strategies could involve inhibiting microglial activation (e.g., NLRP3 blockade)[134], restoring the neuroprotective function of Müller cells (e.g., enhancing glutamate transporters), and targeting key inflammatory factors (e.g., anti-TNF-α therapy). These approaches may help disrupt the pathological feedback loop and attenuate the progression of DR.

Inflammation mediates the progression of retinal neurodegeneration in DR

-

As one of the common complications of diabetes mellitus, diabetic neuropathy is a complex disease secondary to a variety of metabolic disorders and inflammatory damage, in which activation of the inhibitor of kappa B kinase-β/nuclear factor kappa-B (IKKβ/NF-κB) axis plays a central role[94]. Retina, an important tissue structure that plays a role the nerve function, is inevitably damaged by inflammation under DR conditions. Joseph et al. pointed out that the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8 and TNF-α was higher in NPDR patients than in PDR patients, the expression levels of nerve growth factor, brain-derived neurotrophic factor, neurotrophic factor-3, neurotrophic factor-4, ciliary neurotrophic factor and glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor in the eyes of NPDR patients were also higher than those of PDR, further research also confirmed inflammatory cytokines can promote the secretion of neuroprotective factors by stimulating glial cell[124]. This might be an early compensatory response of glial cells stimulated by inflammation. Therefore, it can be concluded that early inflammation may be closely related to early retinal neurodegeneration.

Numerous pieces of evidence have identified that inflammatory mediators can increase vascular permeability; the accumulation of glucose, AGEs, and ROS in the retinal blood vessels of DR patients has also been confirmed to have direct toxic effects on cells[9]. Therefore, after passing through the blood vessel wall, these substances may directly damage the retinal glial cells surrounding the blood vessels and the pigment epithelial cells in the outer layer of the blood-retinal barrier, and the dysfunction of retinal pigment epitheliums (RPE) may also lead to photoreceptor damage and death[31,108].

Activated pro-inflammatory leukocytes in the retinal microcirculation can secrete IL-1β, a key pro-inflammatory molecule in the formation mechanism of DR. It can directly act on the retinal pigment epithelial cells to induce their apoptosis. Secondly, it can also activate the NF-κB pathway to promote the secretion of IL-8, monocyte chemotaxis protein-1, and TNF-α. The function of Müller cells can also be regulated by p38 MAPK/NF-κB pathway through IL-1β[86,135,136].

TNF-α also plays an important role in neurodegeneration. High expression of tumor necrosis factor receptor1 (TNFR1) was also observed in retinal neurons. Studies have shown that blocking the TNF-α pathway by using TNF-α receptor antibodies or inhibiting the activation of TNFR1 not only affected the progression of vascular lesions in DR but also prevented the death of retinal neurons caused by hyperglycemia[137]. On the one hand, TNF-α, secreted by macrophages, can enhance the adhesion of leukocytes, reduce the secretion and production of PDGF by endothelial cells, leading to the increase of ICAM-1, and further aggravate the inflammatory reaction. On the other hand, TNF-α also has a direct neurotoxic effect. In addition to the TNF-α secreted by microglia, TNF-α in inflammatory response can also activate microglia to upregulate the expression of miR-342, which can promote the effect of NF-κB by inhibiting BAG-1, then further promote the secretion of TNF-α and IL-1β, and the overexpression of miR-342 can also induce neuronal cell death[138]. TNF-α can also play a pro-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic role by acting on TNFR-1. Through in vitro cell models, scholars demonstrated that blocking TNFR-1 could not only reduce the percentage of apoptotic cells induced by high glucose but also reduce the activation rate of Caspase-3 to promote cell survival, further confirming the possibility that inflammation-mediated apoptosis and death of retinal nerve cells[137].

In DR, IL-17a can be upregulated by Müller cells in hypoxic conditions. Studies have shown that it can cause the hyperexcitability of neurons, promote the expression of chemokines and cytokines in astrocytes, and also have a synergistic effect with TNF-α to activate the inflammatory signaling pathway and induce the apoptosis of nerve cells[127,139]. IL-17a has been shown to promote neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in the central nervous system. Combined with the mechanisms above, it is reasonable to suspect that IL-17a plays a role in the early inflammation and neurodegeneration of DR. Inflammatory responses also activate pericytes to secrete IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, ROS, nitric oxide, and low-density lipoprotein receptor-associated protein-1 to chemotactic immune cells to the site of inflammation, and activate microglia and astrocytes through the secretion of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP2 and MMP9)[6,25]. IL-6 can also promote the activation of granulocytes and induce the inflammatory response of fibroblasts and endothelial cells[140].

In addition, stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), soluble vascular adhesion protein-1 (sVAP-1), IL-12, INF-γ, and other inflammatory factors were significantly upregulated in the eyes of patients with diabetes, and their expression levels may be related to the severity of DR[141−143]. It is noteworthy that existing studies have demonstrated that hypoxia-induced elevation of HIF-1α can upregulate the expression of SDF-1[144]. The activation of the SDF-1α/CXCR4 signaling pathway enhances the release of glutamate and increases the excitatory activity of microglia and astrocytes, thereby exacerbating excitotoxic neuronal death. Furthermore, this process induces neuronal apoptosis through mutual regulation with Kv2.1 channels[144]. Additionally, research has indicated that inhibiting SDF-1 can potentiate the efficacy of anti-VEGF therapy, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic target applicable across all stages of DR, from early to advanced[142,145]. sVAP-1 recruits white blood cells to the site of retinal inflammation, exacerbates oxidative stress through the activation of NF-κB-dependent chemokines and hydrogen peroxide production, and consequently amplifies retinal damage in DR[143,146]. All these inflammatory factors have shown potential as targets for mitigating early inflammatory damage and retinal neural deformation in DR.

-

Nowadays, the anti-VEGF strategy is recognized as the first-line treatment for DR, but laser photocoagulation therapy is also a good complementary means. However, there are still great challenges on how to conduct intervention therapy in the early stage of DR. Combined with laboratory results, it has been proved that inflammation and retinal neurodegeneration are important mechanisms leading to early retinal injury in DR and it has previously been proposed that there is an interactive relationship between the two mechanisms, but the current treatment strategies have not proposed a plan for this mutual interference mechanism. Therefore, the existing approaches to inflammation and neurodegeneration are summarized, with the hope of getting some new ideas from them to treat early DR.

The importance of anti-inflammatory therapy in the treatment of DR is gradually being emphasized. Especially in DME patients with poor response to anti-VEGF drugs, anti-inflammatory therapy can reduce leukocyte stasis and intracellular adhesion molecule-1 and also activate glucocorticoid receptors to play an anti-apoptotic role and protect the function of retinal photoreceptors[76−78]. The current clinical use of anti-inflammatory drugs is divided into vitreous steroid drugs and non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs. Vitreous steroid drugs mainly include off-label use of triamcinolone and dexamethasone vitreous implants and fluocinolone acetonide (FA) implants approved by the FDA. All three drugs showed advantages of improving BCVA and reducing the frequency of therapeutic injection in DME patients in clinical application. However, the side effects of increased intraocular pressure and cataracts gradually gained attention, especially those treated with triamcinolone[8]. Meanwhile, slow-release implants, such as the biodegradable dexamethasone (DEX) 0.7 mg sustained-release intravitreal implant and a nonabsorbable implant containing 190 μg FA, reduce the frequency of intravitreal injection and the cost of treatment and improves curative effect comparable to that of anti-VEGF drugs[147]. However, combined with the clinical data, intravitreal corticosteroid injection has relatively serious side effects compared with anti-VEGF and laser photocoagulation, which is generally considered the second-line drug[148]. In addition, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs targeting cytokines are undergoing early clinical trials. Cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 are considered to be important factors in exacerbating the inflammatory response in DR Patients and are expected to be future therapeutic targets[34,115]. Compared with steroid drugs, cytokine blockers may be more suitable for long-term anti-inflammatory therapy in patients with DR due to their high selectivity and safety[149−152].

The treatment of retinal neurodegeneration has been gradually studied in depth. Laboratory data proved that glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) is involved in the proliferation and apoptosis of retinal glial cells in DR, dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inhibitors increased GLP-1 and prevented the reduction of glutamate transporter GLAST in diabetic mice, thereby preventing diabetic electroretinography abnormalities and vascular leakage through local treatment[153]. Soluble CD59 can be continuously expressed in the eye through the gene expression vector; compared with the control animal model of DR, it can protect the retina by reducing the apoptosis of retinal ganglion cells, and sCD59 can activate Müller cells to promote the secretion of neurotrophic factors and regulate the tight connection of retinal endothelial cells[154]. Brimonidine and somatostatin did not improve existing neuronal damage, but they were able to prevent further deterioration of retinal neurons in diabetic patients[3]. There are also GSK-3β inhibitors, glial cell activation inhibitors, glutamate excitotoxicity inhibitors, and other pharmacotherapy that target neurodegeneration and have the potential for treating early DR[3]. Exogenous neurotrophic factor supplements, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor, nerve growth factor, ciliary neurotrophic factor, and others have also been proven to be able to reduce the apoptosis of retinal glial cells and own the ability to treat the amplitude deficits in ERG and retinal atrophy[104].

It is important to highlight the interplay between early inflammation and neurodegeneration, which also manifests in certain novel therapeutic strategies (Table 3)[155−159]. In recent years, several innovative treatment strategies for DR, distinct from conventional anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective therapies, have emerged, capturing the attention of researchers. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) serve as crucial regulators of gene expression and have garnered increasing attention in the context of DR research in recent years. In their review, Luo & Li highlighted the pivotal role of miRNAs in DR pathogenesis, underscoring their involvement in pathological processes such as inflammation, oxidative stress, and neurodegeneration[160]. The regulation of specific miRNAs can influence cellular processes such as growth, differentiation, and apoptosis, thereby offering novel therapeutic strategies for the treatment of DR. Current research suggests that particular miRNAs, including miR-146a and miR-21, may ameliorate the pathological conditions associated with DR by modulating inflammatory responses and cell survival pathways. Wang et al. further indicate that miRNA-targeted therapies exhibit significant potential in modulating signaling pathways associated with DR, thereby offering promising avenues for future clinical applications[161]. miRNA-based therapeutic strategies have the potential to simultaneously target multiple pathogenic pathways involved in DR, offering potentially greater efficacy compared to single-target drugs. However, naked miRNAs are highly susceptible to degradation, necessitating the development of stable delivery carriers such as lipid nanoparticles or exosomes. Furthermore, the design of retina-specific delivery systems, including ligand modifications targeting retinal neurons or inflammatory cells, is critical for minimizing off-target effects associated with systemic administration. Additionally, miRNA-targeted therapies may carry the risk of disrupting normal gene regulatory networks, highlighting the need for ongoing research to optimize dosing regimens and administration frequencies. In summary, the integration of miRNA applications with other therapeutic modalities can establish a comprehensive treatment strategy, thereby augmenting the overall therapeutic efficacy. Moreover, Lv et al. utilized single-cell sequencing technology to reveal that activated microglia serve as the primary source of IL-1β in STZ-induced DR models, with alterations in cellular metabolic reprogramming during the early stages of DR being closely associated with neuroinflammatory responses[162]. Consequently, the metabolic reprogramming of these cells may represent a novel therapeutic intervention point. Additionally, investigations into the polarization of macrophages and microglia have demonstrated their potential for therapeutic applications in DR. Yao et al. investigated the role of macrophage/microglial polarization in inflammation and neurodegeneration[163]. In the early stages of DR, hyperglycemia prompts microglia to polarize towards the M2 (anti-inflammatory) phenotype. However, with prolonged exposure to high blood sugar, a decline in M2 microglia results in an increased M1 (pro-inflammatory)/M2 polarization ratio, leading to the secretion of inflammatory mediators and abnormal phagocytosis of surrounding normal retinal neural cells. Moreover, a reciprocal activation may occur between M1 microglia and Müller cells, further exacerbating neuroinflammation. Modulating the signaling pathways of M2 microglia or employing stem cell-based therapies to regulate the polarization of retinal glial cells may potentially mitigate early inflammatory responses and slow the progression of neurodegeneration in DR. However, excessive M2 polarization, while reducing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, can lead to increased expression of VEGF, thereby heightening the risk of pathological retinal neovascularization. Therefore, achieving a balanced regulation of M1/M2 polarization in retinal glial cells is crucial for developing effective therapeutic strategies. Such an approach holds promise for the treatment and prevention of early inflammation and neurodegeneration in DR. Finally, recent studies have investigated the application of small extracellular vesicles as therapeutic carriers. Fan et al. demonstrated that small extracellular vesicles loaded with pigment epithelium-derived factors exhibited superior efficacy in inhibiting retinal neovascularization, inflammation, and neurodegenerative changes compared to anti-VEGF therapies[164]. The advancements in these emerging therapeutic strategies offer novel insights for the treatment of DR and hold promise for providing improved treatment options for patients in the future.

Table 3. Therapeutic drugs for DR have overlapping mechanisms in anti-inflammation and improving neurodegeneration.

Drug category Anti-inflammatory effect Protective mechanisms related to retinal neurodegeneration Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 Regulate the expression of NF-κB and cyclooxygenase-2 Regulate the intracellular mitochondrial homeostasis Epigallocatechin-3-gallate Regulation of oxidative stress by down-regulation of the activity of ROS/thioredoxin Interaction protein/NOD-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome axis Reduce the reactive gliosis of Müller cells Resveratrol Diminish the accumulation of AGEs and attenuate the secretion of inflammatory mediators, including IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and VEGF Inhibition of MicroRNA- 29b/specific protein 1 pathway to reduce Müller cell apoptosis Luteolin It primarily mitigates oxidative stress responses and the production of inflammatory mediators in retinal pigment epithelial cells via the SIRT1/P53 signaling pathway Inhibition of apoptosis of retinal ganglion cells and pigment epithelial cells Aldehyde reductase inhibitors Suppress the phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 as well as the expression of NF-κB and VEGF Alleviate the injury of retinal ganglion cells, yet there is a deficiency of specific preparations. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors Enhance the management of retinal oxidative stress and attenuate the levels of inflammatory factors Mitigate cellular edema and loss in the vicinity of the optic nerve head -

As an important cause of vision loss in adults, DR was considered to be a microvascular dysfunction disease previously, but more and more studies have shown that the role of inflammation and neurodegeneration of DR cannot be ignored in early pathogenesis. Although current anti-angiogenic factor therapy strategies are still the mainstream treatment for DR, they may have little effect on improvement in vision if retinal nerve cell function has been lost.

Traditionally, DR has been regarded as a disease primarily characterized by microvascular dysfunction[165]. However, recent studies have demonstrated that early neurodegeneration (including neuronal apoptosis and glial cell activation) and early inflammation (marked by Müller cell activation and the release of pro-inflammatory factors) interact through a complex signaling network, forming a mutually reinforcing cycle that constitutes the core pathological foundation of early DR. This 'neuro-inflammation-vascular unit' synergistic injury model not only elucidates why ERG abnormalities precede vascular lesions in clinical settings but also provides a scientific rationale for shifting therapeutic strategies from vascular repair to early inflammation control and neuroprotection[166]. Therefore, early intervention with anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective treatments is crucial for delaying the progression of DR. Nowadays, whether targeting inflammation to control neurodegeneration or using neurotrophic cell therapy to delay early inflammation, both strategies have demonstrated promising early intervention effects. However, their safety and mechanisms of action require systematic preclinical validation, particularly through in-depth evaluations of pharmacokinetic profiles and dose-dependent adverse reactions. In this process, establishing an integrated approach to early anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective treatment may produce a synergistic effect on therapeutic outcomes.

Based on current research trends, it is proposed that future therapeutic strategies for early-stage inflammation and neurodegeneration in DR should focus on the following key areas: First, further exploration of DR-related miRNAs is warranted, along with the development of specific inhibitors or agonists targeting these miRNAs[167]. Additionally, it is essential to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety profiles of miRNA-based therapies. Systematic investigation into the roles and mechanisms of miRNAs in DR will provide a robust foundation for developing novel therapeutic approaches. Second, innovative drug delivery systems, such as small extracellular vesicle drug delivery systems and nanoparticles, should be considered for early DR treatment[161]. These emerging therapies have the potential to enhance drug stability and permeability, thereby improving therapeutic outcomes[168]. Third, modulating the activation state or polarization direction of neuroimmune cells within the retina may help delay the progression of early-stage inflammation and neurodegeneration associated with DR. Fourth; clinical guidelines should incorporate neurofunctional assessment indicators to facilitate the development of stratified treatment strategies. Therefore, future research should integrate molecular biology, pharmacology, and clinical trials to further investigate the practical applications of inflammation-targeted therapies in DR.

Therefore, accurately understanding the pathogenesis of early inflammation and neurodegeneration in DR, elucidating their intrinsic relationship, and constructing a comprehensive molecular signaling pathway network are essential prerequisites for alleviating the public health burden associated with DR[169]. This study proposes that early inflammation and neurodegeneration may interact and mutually reinforce each other during the early stages of DR, potentially offering new insights into its early treatment and providing cross-disease implications for neurodegenerative eye diseases such as glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration. By modulating key biomarkers within this interaction mechanism, it may be possible to facilitate the transition from anti-VEGF therapy to early multi-target combination therapies. However, there remains a paucity of laboratory data supporting this interaction mechanism. At present, through the deep integration of multi-omics technologies, organoid models, and artificial intelligence, it is anticipated that significant advancements can be achieved in transitioning from mechanistic analysis to clinical application for the precise prevention and control of DR. Furthermore, during the stage of non-structural retinal changes and abnormal electroretinogram ERG findings, establishing appropriate medication indications and standardizing clinical treatment protocols to benefit DR patients will pose important challenges and requirements for future research.

-

In summary, in addition to angiogenesis, the critical roles of inflammation and neurodegeneration in the onset and progression of DR cannot be overlooked. Besides independently driving DR progression, inflammation, and neurodegeneration exhibit significant interactions that contribute to subsequent retinal microcirculation disorders, thereby influencing the prognosis of DR patients and leading to vision loss symptoms. Early identification of these interactions may provide opportunities for intervention, potentially inhibiting DR progression from a stage with no retinal structural changes to stages characterized by retinal proliferation or macular edema. However, the signaling pathways underlying these interactions remain incompletely understood. Therefore, greater attention should be directed toward research on immune microenvironment regulation, metabolic modulation, and efficient drug delivery systems to effectively manage early DR progression.

-

Not applicable.

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82471089), the Clinical Research Program of The Fourth Military Medical University (Grant No. 2022LC2227), and Xi'an Science and Technology Plan Projects (Grant No. 2024JH-YLYB-0324). We thank the Home for Researchers for the figure editing service.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: writing – original draft preparation: Liu S, Chen C; writing – review and editing: Han J, Yan X; conception: Han J, Liu S, Chen C; graphical design: Liu S, Chen C, Ning J, Ding P; tables design: Liu S, Chen Y, Xie T, Yang H. All authors reviewed the contents and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data presented in this study are included in this published article and related references.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Sida Liu, Chengming Chen

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu S, Chen C, Ning J, Ding P, Chen Y, et al. 2025. Association between early inflammation and neurodegeneration in diabetic retinopathy: a narrative review. Visual Neuroscience 42: e012 doi: 10.48130/vns-0025-0012

Association between early inflammation and neurodegeneration in diabetic retinopathy: a narrative review

- Received: 10 January 2025

- Revised: 23 April 2025

- Accepted: 25 April 2025

- Published online: 07 July 2025

Abstract: Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a severe complication of diabetes that leads to vision loss. Neovascularization, inflammation, and neurodegeneration have been recognized as its primary pathogenic mechanisms. Over the past decades, with the emergence of novel technologies and drugs, the treatment of DR has advanced rapidly, particularly anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) therapy, which has demonstrated unique efficacy. However, current treatments for DR predominantly focus on the progressive stages of the disease. Timely intervention during the early stages of DR to prevent vision loss remains an urgent unmet need. This paper reviews recent literature on the early pathogenic processes of DR and reveals that early inflammation can impair the structure and function of the neural retina, while neurodegeneration exacerbates inflammatory progression to some extent. Moreover, both share common initiating factors. Therefore, this study proposes that an interaction between inflammation and neurodegeneration exists in the early stages of DR, forming a pathological loop. Understanding this interaction could significantly enhance our comprehension of DR pathogenesis and facilitate the identification of more effective therapeutic targets, ultimately improving the prognosis of DR.

-

Key words:

- Diabetes retinopathy /

- Inflammation /

- Neurodegeneration /

- Interactive mechanism