-

Medicinal plants are the basis of both traditional medicine and modern pharmacology. They provide a rich source of bioactive compounds for traditional remedies and serve as indispensable resources in the development of contemporary pharmaceuticals[1,2]. Moreover, medicinal plants and their active compounds have substantial economic significance in a variety of aspects, including food, perfumery, and the chemical industry[1,3]. Genetic transformation is an important research method to promote molecular breeding and biosynthesis of active components of medicinal plants. However, achieving genetic transformation in medicinal plants is very difficult and time-consuming, and to date, only a small number of medicinal plants can be genetically modified. This seriously hinders the molecular biology study of medicinal plants[4,5]. The key to successfully establishing genetic transformation lies in delivering genes or gene-editing tools into plant cells. Typically, there are two methods of gene delivery, including Agrobacterium-mediated infection or particle bombardment. However, these conventional gene delivery techniques require tedious, costly tissue culture processes with low success rates, especially in medicinal plants and other less extensively studied species[6]. Therefore, efficient transformation methods are urgently needed in both basic and applied research on medicinal plants.

Genetic transformation through Agrobacterium is predominantly carried out by two strains: Agrobacterium rhizogenes, known for inducing hairy root (HR) formation, and Agrobacterium tumefaciens, responsible for crown gall development. Generally, the transformation efficiency of A. rhizogenes is higher than that of A. tumefaciens. A. tumefaciens induces callus formation in plants, whereas A. rhizogenes triggers the development of HRs under conditions that do not necessarily require sterility. HRs are adventitious roots induced by A. rhizogenes infection, characterized by vigorous growth, high metabolic activity, and enhanced secondary metabolite production. A. rhizogenes can effectively infect a wide range of plants, including many non-model species such as Lotus corniculatus[7], Corchorus capsularis[8], Phtheirospermum japonicum[9], Calendula officinalis[10] and Centella asiatica[11]. The recently reported CDB delivery system is mediated by A. rhizogenes[12]. Cao et al.[12,13] have utilized the CDB system to successfully execute genetic transformations and gene editing in a variety of medicinal plants. Nonetheless, the direct application of bacteria to wounds or the smearing method yields suboptimal transformation rates. For example, the reported transformation efficiencies of Salvia miltiorrhiza and Polygala tenuifolia were only 6.4% and 2.9%, respectively[13]. Therefore, the primary objectives of this research are to expand the range of medicinal plants that can be transformed and to enhance the efficiency of the transformation process.

Three different medicinal plants were selected—Cynanchi stauntonii, Artemisia argyi, and Chrysanthemum morifolium. These three species of medicinal plants are prevalent and widely utilized in China, particularly A. argyi, which has a broad germplasm distribution and is extensively cultivated[14]. However, research into straightforward and effective genetic transformation techniques for these plants remains limited. Preliminary studies successfully established tissue culture-based genetic transformation systems for C. stauntonii and A. argyi. The transformation efficiency of the RUBY gene in C. stauntonii could reach 56.4% mediated by A. rhizogenes[15], and the highest transformation efficiency of of the RUBY gene in A. argyi callus mediated by A. tumefaciens was up to 60.0%[16]. However, the reported genetic transformation of C. stauntonii. and A. argyi relies on tissue culture. For C. morifolium, Li et al. successfully obtained positive plants by vacuum infiltration of adventitious buds in ornamental C. morifolium[17]. However, there have been no reports on the tissue culture-free genetic transformation system for medicinal C. morifolium. Therefore, in this study, the most suitable A. rhizogenes strains were screened and the inoculation method was optimized to establish a rapid and convenient genetic transformation system for these three medicinal plants. It is anticipated that this tissue culture-free genetic transformation method will serve as a valuable tool for functional studies of medicinal plants.

-

C. stauntonii, A. argyi, and C. morifolium were collected from the Medicinal Botanical Garden of Hubei University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The three medicinal plants were cultivated in a growth chamber for 4−6 weeks at 25 °C with a photoperiod of 16 h light and 8 h darkness, after which tender shoot tips were excised as explants. Excess leaves were removed, except for the apical bud, for use in A. rhizogenes infection assays.

A. rhizogenes strains and HRs induction procedures

-

A. rhizogenes strains ATCC15834, Ar.A4, K599, and MSU440 harbouring vector 35s:RUBY[18]were used for HRs induction of C. stauntonii, A. argyi, and C. morifolium. Bacterial strains ATCC15834, Ar.A4, K599, MSU440 and C58C1 were shaken at 28 °C in TY liquid medium (Tryptone yeast extract medium, tryptone 5.0 g/L, yeast extract 3.0 g/L)[19]. The above strains were purchased from Shanghai Weidi Biotechnology Co., LTD (Shanghai, China). After 24 h, bacterial cultures were collected at 8,000 rpm for 5 min and resuspended in MS liquid medium, respectively. The suspensions were then shaken for 12 h at 28 °C in a rotary shaker at 140 rpm prior to inoculation.

For the infection protocol, plant material was used by immersing the lower portion of the stem segment in a prepared bacterial solution with an optical density (OD600) of 0.8−1.0. It is crucial to ensure that the wound is fully submerged in the bacterial solution. The soaking time was set to 30 min. Subsequently, the inoculated material was placed in a seedling tray filled with sterilized pure vermiculite. Additionally, 1 mL of the remaining bacterial solution was added at the base of the explants. After inoculation, the explants were placed in a growth chamber at 25 °C with a photoperiod of 16 h light and 8 h darkness. Initially, water was added to the culture medium. One week post-inoculation, nutrient solution was introduced. Positive hairy roots (HRs) could be observed after approximately 4 to 6 weeks. HRs induction efficiency refers to the success rate of inducing hairy roots in explants through A. rhizogenes infection, serving as a measure of efficiency in plant tissue culture or genetic transformation processes. Transformation rate is the proportion of explants or cells that successfully integrate foreign genes into their genome during plant genetic transformation, serving as an indicator of transformation efficiency. The efficiency was calculated as: HR induction efficiency = (Numbers of explants induced hairy root / Total numbers of explants) × 100%; Transformation rate = (Positive transgenic hairy root explants / Total induced hairy root explants) × 100%[20].

Comparison of different inoculation methods of A. rhizogenes

-

Four different inoculation methods including soaking, injection, shaking and mechanical damage, were used to investigate the effects of different infection methods on transformation efficiency. A total of 30 explants were used for each treatment, with each treatment replicated four times. The soaking procedure was performed as described previously. For the injection method, a 1 mL syringe was used to inject the A. rhizogenes solution into an area 1 cm below the lower end of the explant until the solution drained from the injection site. For the shaking method, explants were soaked in the A. rhizogenes solution and placed on a shaker at 28 °C and 150 rpm for 30 min. For the mechanical damage method, the outer epidermis of the lower 1 cm portion of the explants was gently scraped using a scalpel blade, followed by soaking in the A. rhizogenes solution for 30 min. Planting and statistical methods for positive materials were consistent with the protocols described previously.

RNA isolation and PCR analysis

-

RNAprep pure plant kit (Tiangen, China) and reverse transcription kit (Vazyme, China) were used for hairy root RNA extraction and reverse transcription. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using PrimeScript™ RT kit and gDNA Eraser (Takara, China). Extractive RNA (C. stauntonii, C. morifolium and A. argyi) and A. rhizogenes DNA (ATCC15834, Ar.A4, K599 and MSU440 harbouring vector 35s::RUBY) were used as negative and positive controls (Supplementary Tables S1−S3), respectively.

Genetic transformation efficiency of different A. argyi resources

-

Five A. argyi germplasm materials from different origins: S07 (Anguo, Baoding), S16 (Wuolong, Nanyang), S21 (Hong'an, Huanggang), S30 (Qichun, Huanggang), and S54 (Qixia, Nanjing)[21] were used to investigate the applicability of the established genetic transformation methods according to prior method.

Statistical analysis

-

The experiment was conducted using a single-factor experimental design method. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with SPSS version 21.0 software (IBM, New York, NY, USA) employed for the calculations. Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of the four independent biological replicates.

-

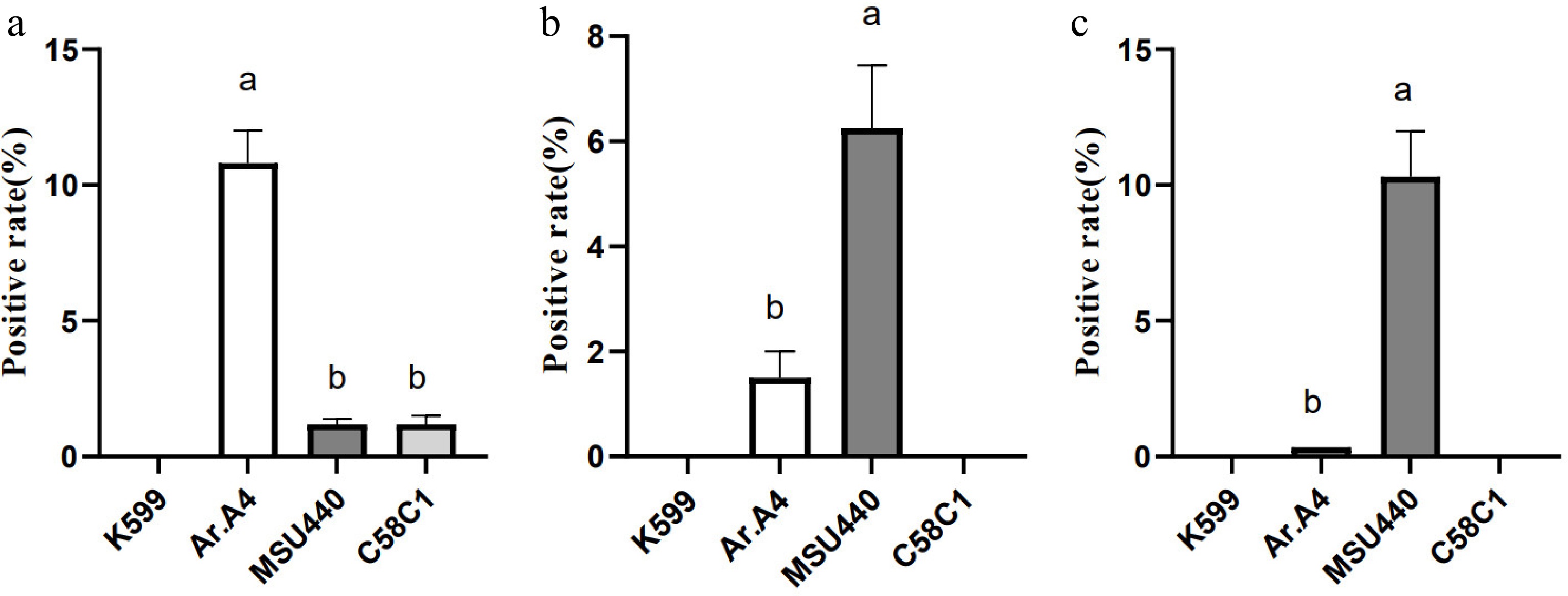

Referring to the previously published CDB method, hairy root (HR) induction was attempted in three medicinal plants (C. stauntonii, A. argyi, and C. morifolium) using the K599 strain without tissue culture. However, after multiple attempts, no positive HRs were obtained in any of the three plants. Therefore, it was hypothesized that the A. rhizogenes strain might affect the efficiency of hairy root transformation. To test this, hairy root induction experiments were conducted on C. stauntonii, A. argyi, and C. morifolium using four different strains: K599, Ar.A4, MSU440, and C58C1. Following the CDB method for infection, the Ar.A4 strain induced the highest hairy root formation efficiency in C. stauntonii, reaching 10.8% (Fig. 1a). MSU440 and C58C1 could also induce some HRs in C. stauntonii, but with lower efficiencies of only 1.2% each. For A. argyi, MSU440 showed the highest induction efficiency at 6.3% (Fig. 1b), followed by Ar.A4 at 1.5%, while C58C1 failed to induce HRs. Similarly, MSU440 had the highest induction efficiency for C. morifolium at 10.2%, followed by Ar.A4 at 0.35%, and C58C1 showed no effect (Fig. 1c). Notably, the K599 strain, as reported in the literature, was unable to induce HRs in any of the three medicinal plants.

Figure 1.

Effects of different Agrobacterium rhizogenes strains on infection efficiency in (a) Cynanchum stauntonii, (b) Artemisia argyi, and (c) Chrysanthemum morifolium. This result was obtained using one-way analysis of variance. Lower-case letters above the columns indicate statistically significant differences among the indicated groups (p < 0.05, Duncan's multiple-range test).

Effects of different inoculation methods on genetic transformation efficiency

-

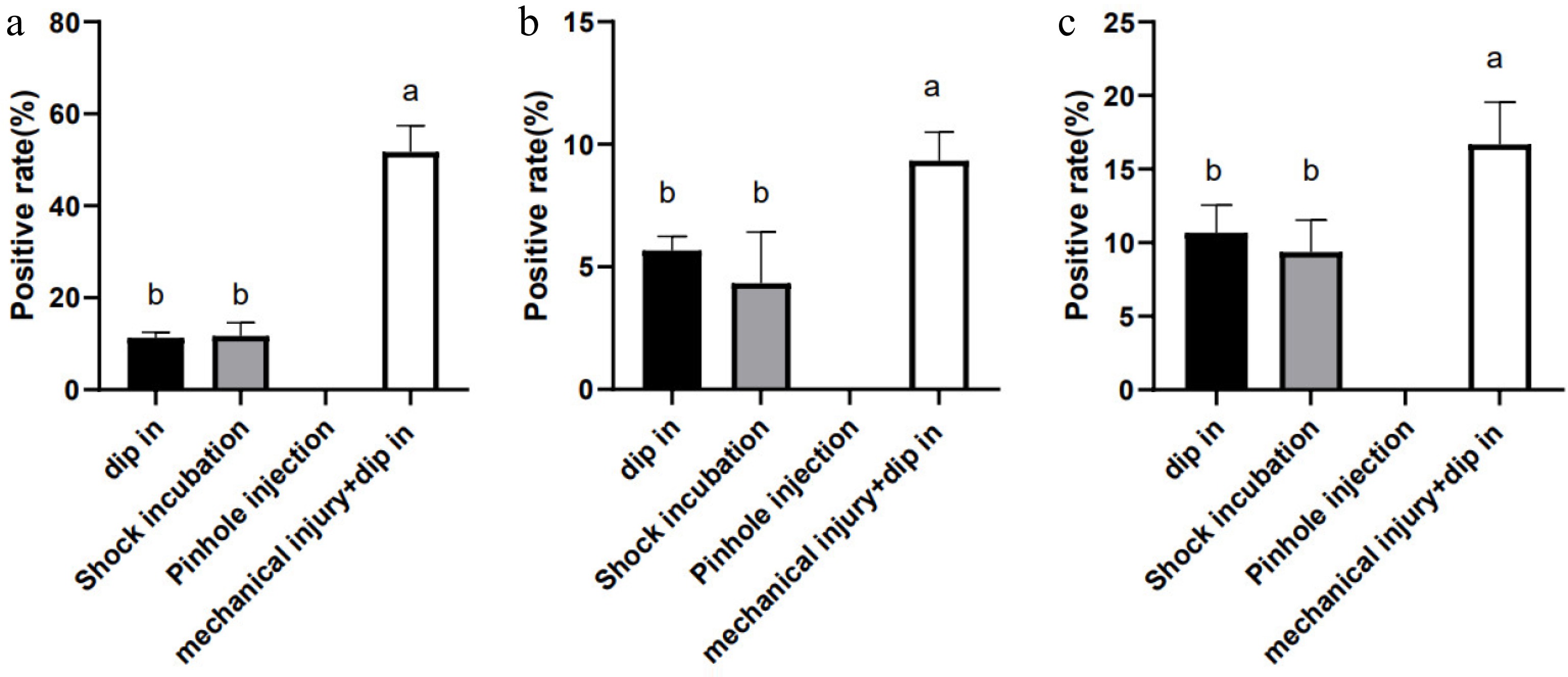

The inoculation process is also a critical factor affecting transformation efficiency. Investigating effective inoculation methods can better enhance the infection efficiency of A. rhizogenes. In the CDB method, the simplest approach of dipping the cut wound into bacterial suspension is commonly used, where the bacteria enter the plant through the wound to produce positive root systems. However, experiments revealed that merely using the cut wound dipping method was difficult to achieve optimal induction efficiency. Therefore, alternative strategies were explored to improve induction efficiency by using methods such as soaking in bacterial suspension, shaking co-cultivation in a shaker, and injection combined with mechanical injury.

The optimal strains identified (Ar.A4 strain for C. stauntonii and MSU440 strain for A. argyi and C. morifolium) were used to explore the best infection methods, aiming to achieve the highest HR induction efficiency. Four distinct methods—soaking, shaking incubation, injection and mechanical injury were used to enhance infection efficiency. Figure 2 illustrated that the genetic transformation efficiency of the three medicinal plants improved markedly following mechanical damage treatment, with the highest efficiencies recorded at 51.7%, 9.3%, and 16.7% (Fig. 2a−c) in C. stauntonii, A. argyi, and C. morifolium, respectively. In contrast, shaking incubation and static soaking methods did not yield significant improvements in genetic transformation efficiency, while the injection method failed to produce any successfully transformed root material. Through observation, it was noted that following mechanical damage, the material at the wound site began to develop callus during the infection process, in contrast to the non-infected material. Subsequently, a substantial number of HRs were successfully induced. The expansion of the wound area to a certain extent may enhance the efficiency of A. rhizogenes infection, thereby significantly increasing the infection rate.

Figure 2.

Effects of different inoculation methods on infection efficiency in (a) Cynanchum stauntonii, (b) Artemisia argyi, and (c) Chrysanthemum morifolium. This result was obtained using one-way analysis of variance. Lower-case letters above the columns indicate statistically significant differences among the indicated groups (p < 0.05, Duncan's multiple-range test).

Establishment of the highly efficient A. rhizogenes-mediated genetic transformation method bypassing tissue culture

-

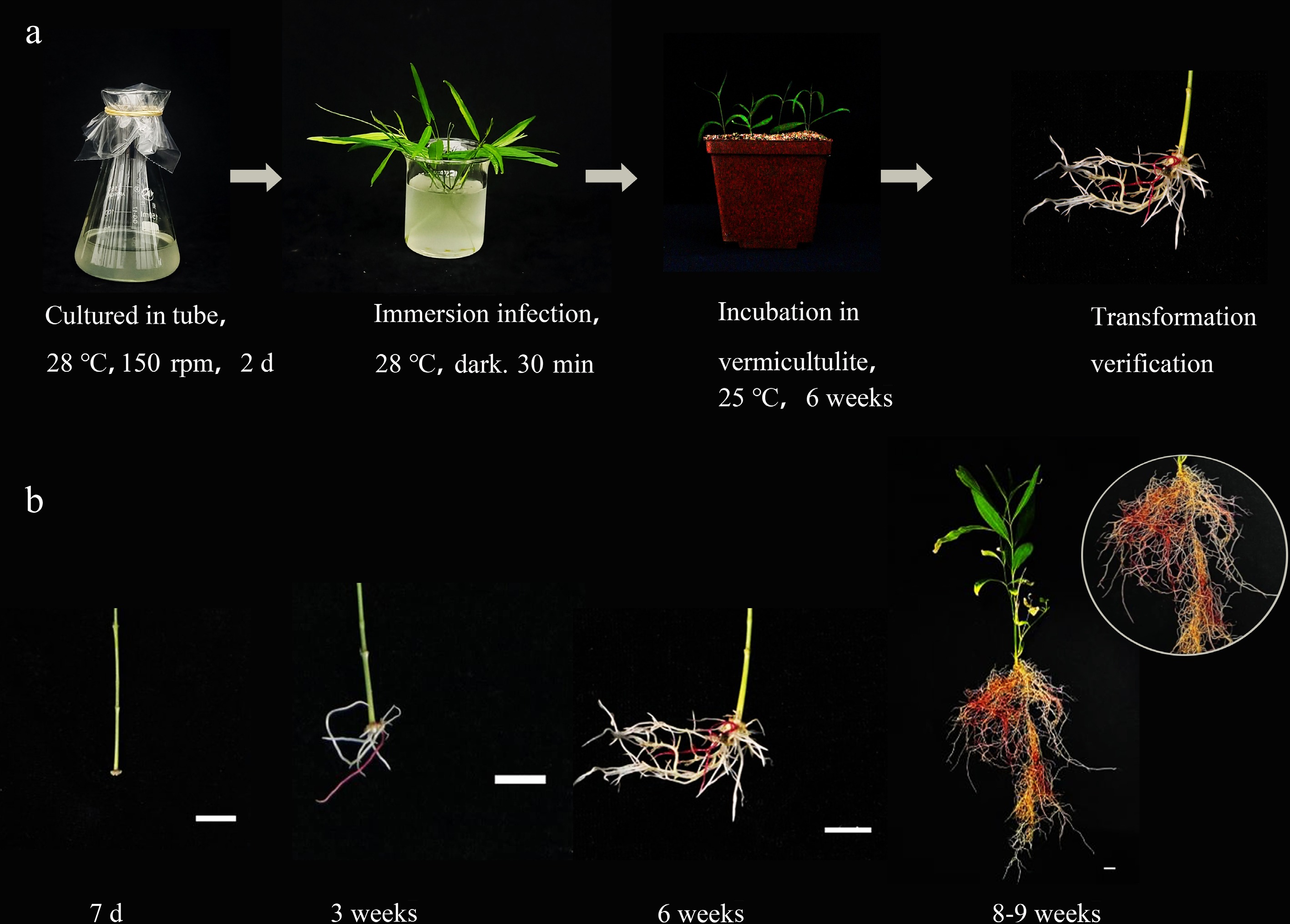

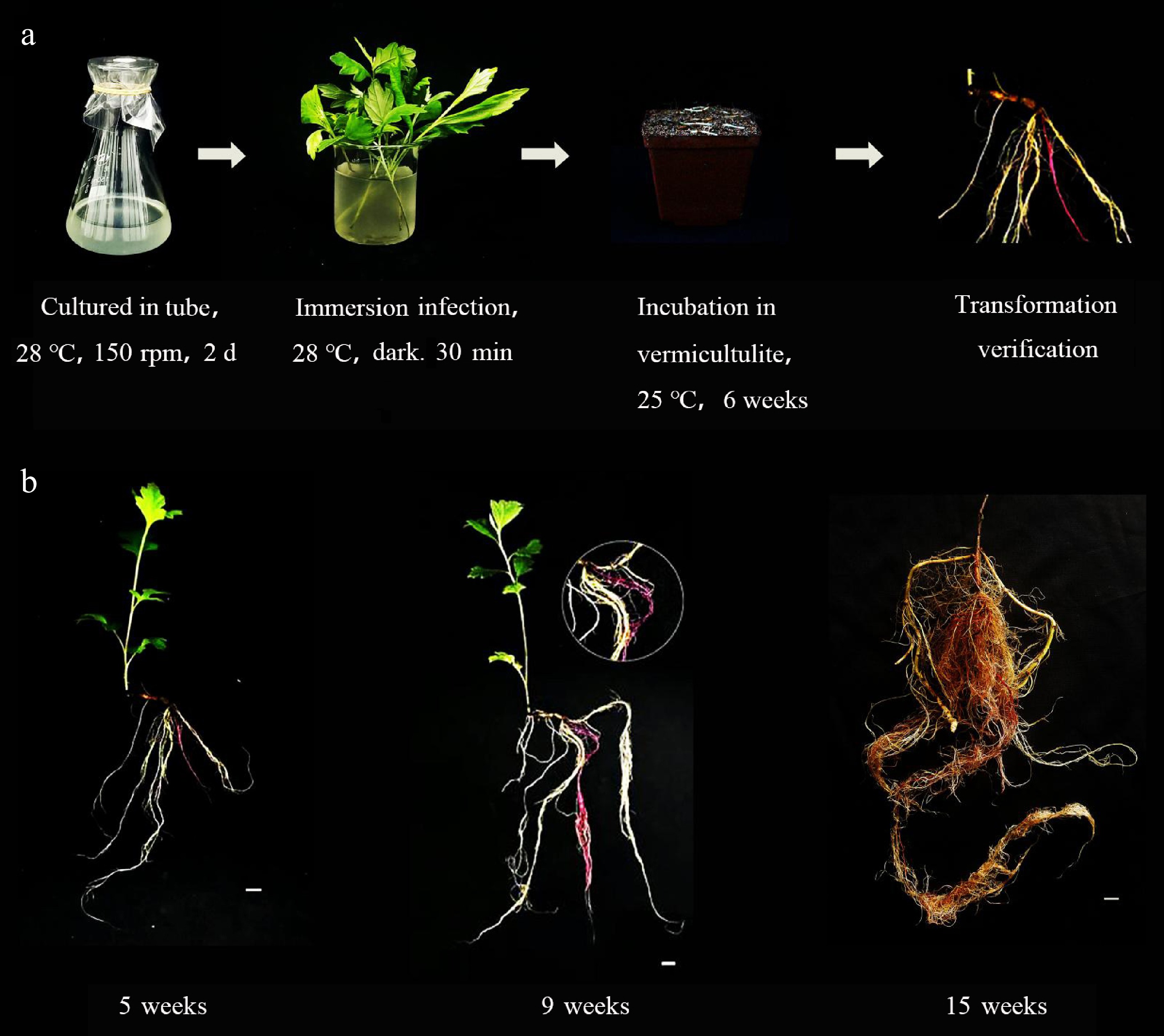

By optimizing the bacterial strains and inoculation methods, genetic transformation methods were established for C. stauntonii, A. argyi, and C. morifolium without the need for tissue culture, using RUBY as the reporter gene. As shown in Table 1, C. stauntonii, mechanically damaged stem segments were infected with the A4 strain carrying the RUBY plasmid. The wounds of the stem segments were soaked in bacterial suspension cultured at 28 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, the soaked explants were planted in vermiculite and cultured under a 16 h light/8 h dark regime for 2 d (Fig. 3a). During the initial 7 d, swelling at the wound site was observed, and root emergence began to be visible after 3 weeks. By 6 weeks, the roots showed significant branching and proliferation, and by 8−9 weeks, a large number of plants with positive roots were obtained (Fig. 3b). The final transformation rate for C.stauntonii was 39.3%.

Table 1. Genetic transformation efficiencies of three medicinal plants.

Medicinal plants Number of explants Positive number Positive rate C. stauntonii 135 53 39.3% A. argyi 142 11 7.7% C. morifolium 160 21 13.1%

Figure 3.

Acquisition of positive materials in Cynanchum stauntonii via a tissue-free inoculation method. (a) The inoculation process of Cynanchum stauntonii without tissue culture. (b) Growth status of positive materials at different stages in Cynanchum stauntonii explants.

For A. argyi, MSU440 was inoculated into shoot tip explants (Fig. 4a), which were then placed in vermiculite. Similar to C. stauntonii, the positive root system of A. argyi was observed around 5 weeks (Fig. 4b). Over a period of 15 weeks, the positive root system expressing RUBY gradually expanded and grew and became increasingly thickened. The statistical results indicate that the transformation rate of A. argyi was 7.7%.

Figure 4.

Acquisition of positive materials in Artemisia argyi via a tissue-free inoculation method. (a) The inoculation process of Artemisia argyi without tissue culture. (b) Growth status of positive materials at different stages in Artemisia argyi explants.

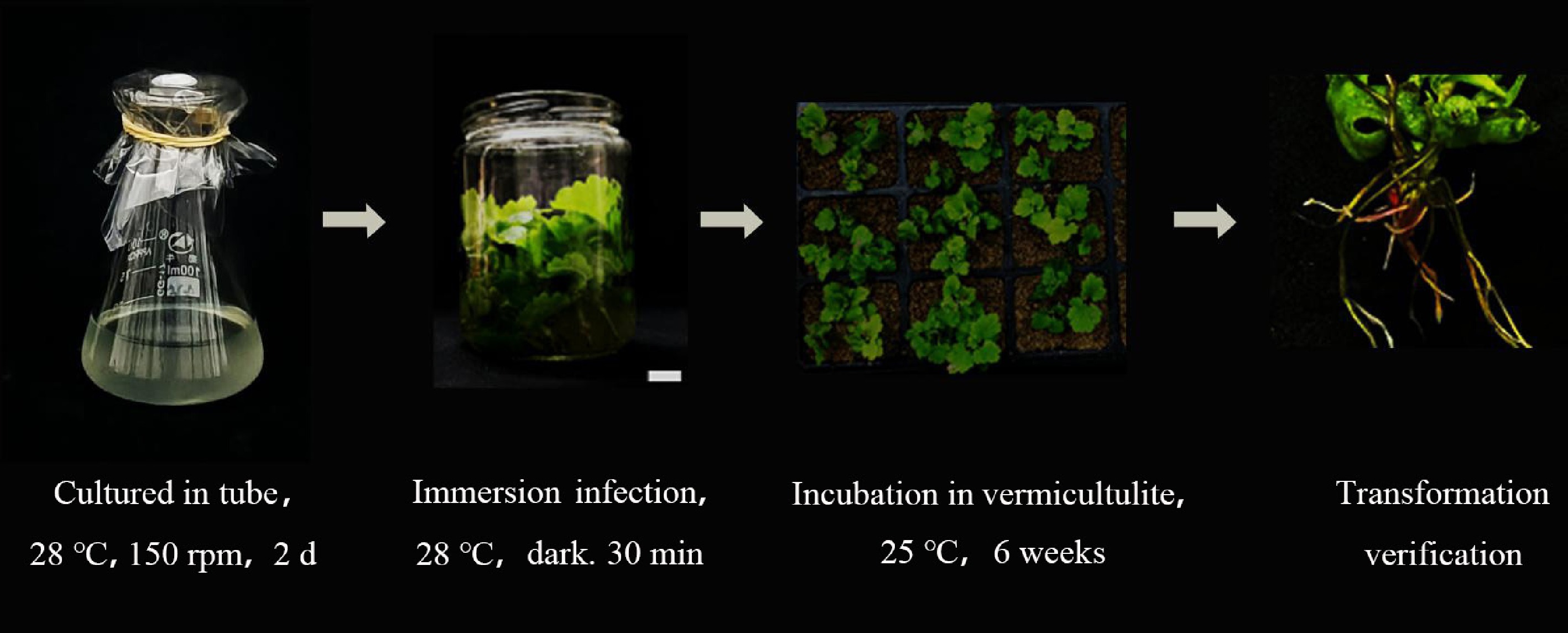

For C. morifolium, young stems from 20−40 day-old seedlings, each retaining 2−3 leaves, were immersed in the MSU440 bacterial solution for transformation (Fig. 5). After approximately 4 weeks, a large number of plants with positive roots were obtained. The statistical results showed that the transformation rate of C. morifolium was 13.1%. PCR identification of RUBY tandem genes CYP76AD1, DODA and GT was performed. The results showed that all three tandem genes could be detected in the experimental group (Supplementary Fig. S1), which proved that the genetic transformation system for three medicinal plants without tissue culture was successfully constructed.

Figure 5.

Acquisition of positive materials in Chrysanthemum morifolium via a tissue-free inoculation method. (a) The inoculation process of Chrysanthemum morifolium without tissue culture. (b) Growth status of positive materials at different stages in Chrysanthemum morifolium explants.

The genetic transformation mediated by A. rhizogenes is suitable for different germplasm resources and different explants of A. argyi

-

The genetic transformation system for medicinal plants is constrained by factors such as genotype. To investigate the potential for genetic transformation across multiple genotypes, infection experiments was conducted on five previously collected germplasm resources of A. argyi. The results demonstrated that, under infection conditions optimized for mechanical damage, positive root systems were induced in all five materials. However, there were notable differences in efficiency among the materials. Specifically, S07 exhibited the highest induction efficiency at 10.9%, while S21 showed an infection efficiency of 5.9% (Table 2). The lowest infection efficiency was observed in S16, which recorded only 2.1%. This method utilizes young shoots and above-ground rhizomes as explants for infection induction, which can reach 10.4% and 8.3% Transformation rate, respectively (Table 3).

Table 2. Comparative analysis of genetic transformation efficiency in different A. argyi varieties.

A. argyi variety Number of explants Positive number Positive rate S07 110 12 10.9% S16 96 2 2.1% S21 102 6 5.9% S30 86 3 3.5% S54 122 4 3.3% Table 3. Comparative analysis of genetic transformation efficiency in different explants of A. argyi.

Explant Number of explants Positive number Positive rate Branches 96 10 10.4% Rhizomes 96 8 8.3% -

Medicinal plants are of considerable importance due to their medical, economic, ecological, and botanical value[22]. These plants are rich sources of specialized secondary metabolites[23]. However, significant challenges remain in the exploration and utilization of key genes responsible for the production of bioactive compounds[24,25]. The introduction of genetic improvement tools into plant cells poses a considerable obstacle to gene editing and directed plant breeding. Among the thousands of higher plant species worldwide, only a limited number, approximately a few dozen, are amenable to genetic modification. Currently, gene editing is feasible in only a select few plant species, primarily through tissue culture-based genetic transformation, which is often characterized by low transformation efficiencies[13, 26]. The establishment of a tissue culture system, the long-term cultivation of sterile materials and the development of an efficient genetic transformation system have significantly hindered the advancement of gene research in medicinal plants. Consequently, there is a pressing need to identify more convenient and expedited methods for establishing genetic transformation systems in these plants[27].

In this study, an efficient and convenient tissue culture-free genetic transformation system for three medicinal plants has been established. The materials selected for this research are young branches or rhizomes, which are easy to collect. Consequently, a sufficient quantity of positive HRs can be obtained by gathering an adequate number of explants. This process can be completed more efficiently through mechanical damage and immersion infection. A previous study reported a C. morifolium hairy root induction system capable of rapidly producing large amounts of pyrethrins[28]. However, this method necessitates the use of sterile leaves that have been pre-cultured and the addition of antibiotics to the culture medium for screening and decontamination. In this study, it was observed that different medicinal plants exhibit varying susceptibility to A. rhizogenes. Specifically, Ar.A4 demonstrated the highest infection efficiency in C. stauntonii, while MSU440 showed the highest positive infection rate in A. argyi and C. morifolium. The suitable of the same bacterial strain for A. argyi and C. morifolium may be related to the fact that both materials belong to the Asteraceae family. In contrast, the commonly used strain K599 has been reported previously to have low infection efficiency with these three medicinal plants. This indicates that bacterial strains are one of the crucial determinants of infection efficiency[29−32]. Consequently, the genetic transformation protocol established is both simple and cost-effective, as it eliminates the need for tissue culture and antibiotic screening.

Genetic transformation efficiency was significantly enhanced through mechanical damage. Many studies utilized the vacuum infiltration method to infect explants, which effectively improves the explant infection process[33,34]. However, this method is not conducive to field operations. Observations revealed that HRs typically emerge at the edges of wounds. Therefore, wound expansion at the edges of the inoculation sites was performed to enhance induction. The mechanism by which mechanical damage enhances transformation efficiency may be analogous to the leaf disc method, as it facilitates better integration of the Rol gene from A.rhizogenes into the wound, thereby substantially increasing transformation efficiency. The findings indicated that mechanical damage elevated the genetic transformation efficiency of C. stauntonii by fivefold. In comparison to simple infiltration, the genetic transformation efficiency of A. argyi was approximately doubled, while that of C. morifolium was increased by 1.5 times. This characteristic can be leveraged to conduct extensive studies on genetic transformation methods for medicinal plants.

The three medicinal plants demonstrated varying efficiencies in response to different A. rhizogenes strains and infection methods. After optimization, C. stauntonii showed a significantly higher infection efficiency than A. argyi and C. morifolium. Moreover, after mechanical damage, the infection efficiencies of the three medicinal plants can reach 51.7%, 9.3%, and 16.7%, respectively. These differences in transformation efficiency may be attributed to the differences in oncoplasmids or virulence genes used for T-DNA delivery, although the detailed mechanisms leading to the differences in transformation efficiency remain to be explored[35]. For example, the A. rhizogenes strain K599 has shown high efficiency in CDB method-based genetic transformation. This may be because specific genes (such as Vir genes) of this strain have higher transcriptional activity and efficiency during the infection process. The proteins encoded by these genes can effectively identify and bind to receptors on plant cell walls, thereby promoting the transfer of exogenous genes into plant cells[36]. In addition, the infection ability of Agrobacterium is closely related to the expression level of virulence factors. Some strains may have a higher expression of virulence factors, enabling them to more effectively break through the defense mechanisms of plant cells, transfer the Ti or Ri plasmid carrying the target gene into plant cells more efficiently, and promote its integration into the plant genome[37].

Three medicinal plants—C. stauntonii, A. argyi, and C. morifolium—were selected, each possessing underground rhizomes with regenerative properties. Consequently, an alternative approach was explored to circumvent traditional tissue culture methods. By harnessing the attributes of A. rhizogenes, the objective was to introduce target genes directly into these plants, thereby inducing the formation of rhizomatous stems. However, regenerated plants were not obtained from any of the three medicinal plants following inoculation with A.rhizogenes. Through experimental observations and in conjunction with the literature on CDB and related regeneration, roots with regenerative buds or dormant buds are more conducive to regeneration. While the three tested species produced positive root systems, it is difficult to further induce bud formation on these positive roots to form positive plants. This also provides insight for future research on CDB regeneration, highlighting the importance of material selection.

-

In this study, a rapid and efficient genetic transformation system was established for three medicinal plants (C. stauntonii, A. argyi and C. morifolium) by using A. rhizogene mediated HRs induction, enabling the acquisition of positive materials without the need for tissue culture or antibiotics. Furthermore, the methodology was optimized to identify bacterial strains that enhance the induction efficiency for each plant. Notably, mechanical damage was employed to significantly improve infection efficiency, resulting in a fivefold increase in the infection efficiency of C. stauntonii. Additionally, the method is applicable to various germplasms, facilitating easy material selection and collection. Collectively, the method developed in this study provides a foundation for future genetic improvement and functional genomics studies of medicinal plants.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(Grant No. 82304660); the HuBei Provincial Natural Science Foundation Innovative Group Project (Grant No. 2023AFA032); the Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation and Traditional Chinese Medicine Innovation and Development Joint Foundation of China (Grant No. 2024AFD228); the Hubei University of Chinese Medicine 2024 Scientific and Technological Innovation Project (Grant No. 2024KJCX005); and the Hubei Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 2024AFB371).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Miao Y; performed experiment: Zhang J, Huang B, Nan P, Zhang Q, Li J; writing preparation: Zhang J, Miao Y; supervision, funding acquisition: Liu D, Miao Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Identified by PCR of the target gene system.

- Supplementary Table S2 Taq enzyme PCR amplification cycle reaction.

- Supplementary Table S3 PCR primers identified by RUBY tandem genes.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 PCR identification of three tandem genes CYP76AD1, DODA and GT in RUBY-genetic transformd hairy roots. Positive control: 35S::RUBY plasmid; experimental group: RUBY-genetic transformed hairy roots; negative control: empty vector-transformed hairy roots.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang J, Huang B, Peng S, Zhang Q, Li J, et al. 2025. Establish methods to improve the efficiency of tissue-free genetic transformation of medicinal plants through mechanical damage. Medicinal Plant Biology 4: e025 doi: 10.48130/mpb-0025-0023

Establish methods to improve the efficiency of tissue-free genetic transformation of medicinal plants through mechanical damage

- Received: 13 February 2025

- Revised: 19 May 2025

- Accepted: 20 May 2025

- Published online: 25 July 2025

Abstract: Medicinal plants are widely used in various fields, such as medicine, fragrance production, cosmetics and food. However, only a small number of medicinal plants can be genetically modified, making it difficult to improve these plants through genetic engineering. A tissue culture-free method was established to transform three medicinal plants: Cynanchi stauntonii, Artemisia argyi, and Chrysanthemum morifolium. In this method, mechanical damage and Agrobacterium rhizogenes species were found to significantly enhance infection efficiency. The results showed that A. rhizogenes strain A4 achieved the highest induction rates in C. stauntonii, while strain MSU440 demonstrated superior transformation efficiency in both A. argyi and C. morifolium. Additionally, scraping off the basal epidermis with a blade to create mechanical damage significantly enhanced infection efficiency in the three medicinal plants. Through A. rhizogenes strain selection and infection method optimization, C. stauntonii, A. argyi, and C. morifolium achieved the highest transformation efficiencies of 51.7%, 9.3%, and 16.7%, respectively. This gene transformation technology overcomes the technical problems of low efficiency, long experiment period and high cost, and provides a valuable tool for genetic research and precise breeding of medicinal plants.