-

Ophiocordyceps sinensis is a complex of larval bodies and stroma, also known as 'DongChongXiaCao'. O. sinensis has a long history of application in China and is often used to treat kidney-related diseases. It was first published in the eighth century AD in the Moon King Medical Manual, which recorded the effect of O. sinensis in the treatment of lung diseases. In 1757 AD, the New Compilation of Materia Medica provided a detailed description of the medicinal properties of O. sinensis, documenting its efficacy in lung protection, kidney nourishment, hemostasis, phlegm reduction, cough relief, and diaphragm treatment[1]. Modern research has confirmed that O. sinensis contains nucleosides, sterols, polysaccharides, peptides, and other metabolites[2], which have antioxidant, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, antibacterial, immunomodulatory, hypoglycemic, and other pharmacological effects[3]. Recognized as one of the 'three treasures of traditional Chinese medicine' alongside Panax ginseng and Cornu cervi pantotrichum, O. sinensis holds a prestigious status in both domestic and international herbal medicine.

Recent studies have increasingly focused on the chemical composition and pharmacological action of O. sinensis, and the biosynthetic pathways of some important compounds have been analyzed. The novel compounds and pharmacological mechanisms are still being discovered. Therefore, this paper systematically reviews the resources, bioactive constituents, biosynthetic pathways, and pharmacological activities of O. sinensis, aiming to provide a scientific foundation for its clinical application and future development.

-

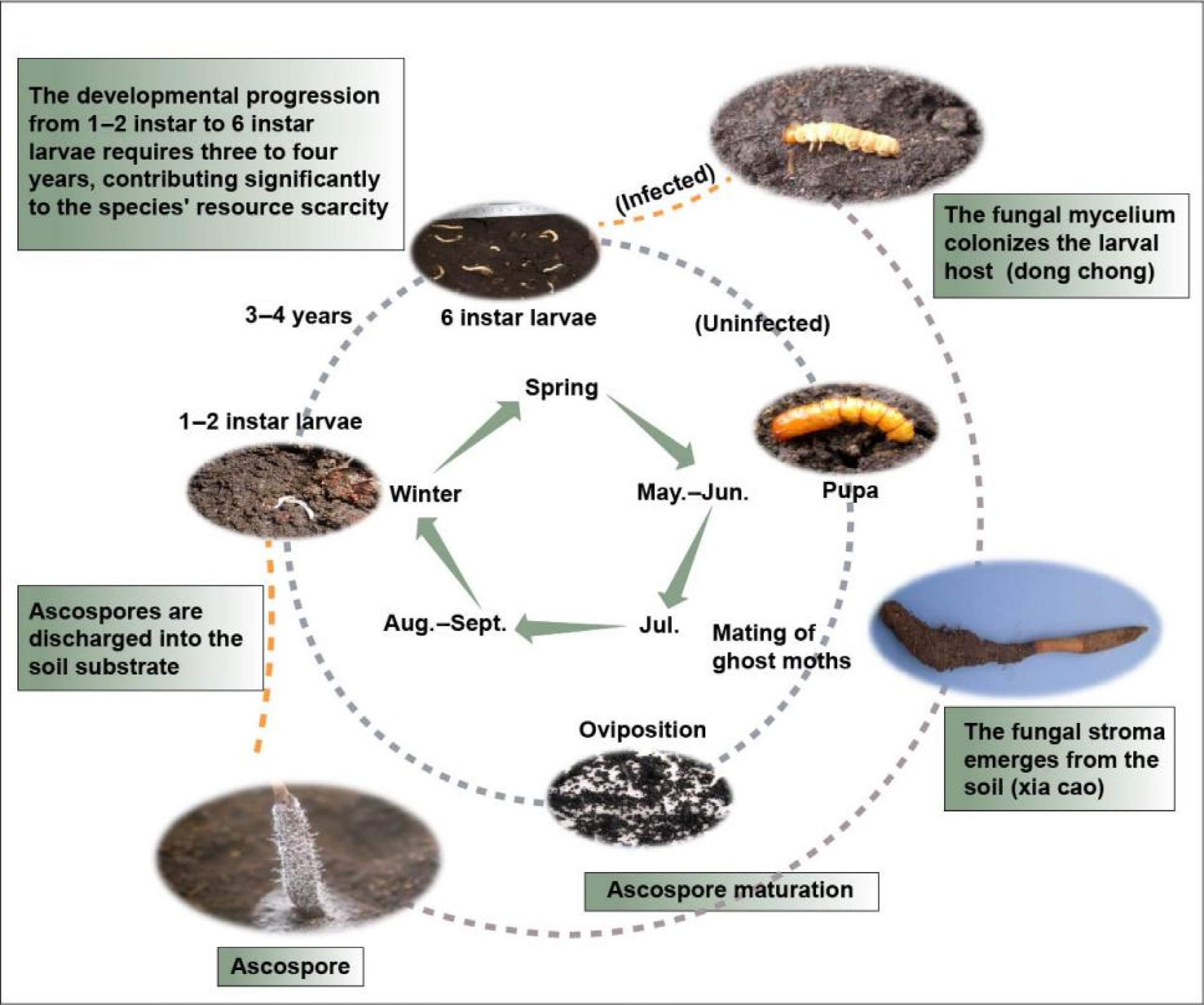

The remarkably slow growth rate of O. sinensis constitutes a primary limiting factor in its natural population replenishment, contributing significantly to current resource shortages. In summer, mature O. sinensis catapults ascospores into the soil, which infect the 1−2 instar larvae belonging to the Hepialidae. The uninfected larvae progress through six instar stages (typically requiring three to four years) before pupating and emerging as ghost moths to reproduce, while infected larvae undergo a distinct fate. As the fungal mycelium colonizes and consumes the host's nutrients, the larvae gradually become sclerotized. These infected larvae, referred to as 'DongChong' in traditional medicine, represent a critical developmental stage. By early summer, the fungal stroma emerges from the larval head, piercing through the soil surface to form the characteristic 'XiaCao' (summer grass) appearance[4] (Fig. 1).

O. sinensis exhibits an extremely limited global distribution, occurring naturally in only four countries: China (primarily in Xizang, Qinghai, and Sichuan provinces), Bhutan, India, and Nepal. China dominates production, accounting for over 90% of the global supply[5]. Renowned for its exceptional medicinal properties, O. sinensis has become a highly prized resource widely utilized in biomedical applications, nutraceuticals, and premium cosmetic formulations. However, O. sinensis exclusively inhabits high-altitude plateaus (3,000−5,000 m above sea level), where extreme environmental conditions severely constrain its natural productivity[6]. The combination of these ecological limitations with escalating global demand has driven a dramatic price surge over the past two decades. Currently commanding prices exceeding that of gold by weight, this prized medicinal species has earned the moniker 'soft gold' in commercial markets.

Facing mounting resource constraints and market demands, Chinese researchers successfully isolated the asexual stage of O. sinensis, achieving a breakthrough in its artificial cultivation[7]. After years of systematic optimization, scientists established reproducible and stable cultivation protocols. Notably, the mycelia of O. sinensis from different regions show obvious genetic differentiation. Various methods have been used to study their genetic diversity, such as randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD), inter-simple sequence repeat (ISSR), non-concerted ITS, etc.[8].

-

Given its exceptional medicinal properties, O. sinensis has been the focus of extensive phytochemical research for decades. In this process, various extraction methods and detection techniques have been employed to investigate the compounds within it. These species contain a multitude of nutrients, including polysaccharides, nucleosides, sterols, proteins, and peptides, as well as trace elements. These substances serve as the essential material basis for the therapeutic effects of O. sinensis.

Polysaccharides

-

Polysaccharides represent a class of high-molecular-weight polymers composed of ten or more monosaccharide units linked by glycosidic bonds. In light of the escalating costs and declining availability of wild O. sinensis, scholars often extract polysaccharides from cultured mycelium, which has been proven that the pharmacological activity and chemical composition are similar to natural O. sinensis. To date, around 50 polysaccharides have been characterized, which were isolated from different sources of wild O. sinensis and mycelium (Table 1).

Table 1. The source, name, molecular weight, and monosaccharide composition of polysaccharides isolated from O. sinensis and mycelium.

No. Source Name M.W. (kDa) Monosaccharide composition Ref. 1 Natural P1 950.00 Glc, Gal, Man, GalA [13] 2 Natural P2 15.00 Glc, Gal, Man [13] 3 Natural P3 1,000.00 Glc, Gal, Man [13] 4 Cultured P4 28.00 Glc, Gal, Man, GalA, Ara [13] 5 Fermentation broth EPS-1A 40.00 Glc, Gal, Man [14] 6 Mycelium EPS2BW 50.00 Gal, Man [15] 7 Fermentation broth EPS N.A. Glc, Man [16] 8 Fermentation broth EPS1U 730.00 Glc, Gal, Man [17] 9 Mycelium PolyhexNAc 6.00 Glc, ManNAc [18] 10 Mycelium AEPS-1 36.00 Glc, Man [19] 11 Mycelium WIPS 1,180.00 Glc [11] 12 Mycelium AIPS 1,150.00 Glc [11] 13 Natural NCSP-50 976.00 Glc [20] 14 Mycelium CME-1 27.60 Gal, Man [21] 15 Cultured CPS-A 12.00 Glc, Man [22] 16 Mycelium UM01-S4 22.56 Glc, Gal, Man [23] 17 Natural UM01-PS 580.00 Glc, Gal, Man [24] 18 Cultured UST- 2000 82.00 Glc, Gal, Man [25] 19 Mycelium HSP-III 513.89 Glc, Gal, Man, Ara, Xly, Rha [26] 20 Mycelium CPS1 8.10 Glc, Gal, Man [27] 21 Cultured CSP1-2 27.00 Glc, Gal, Man [28] 22 Cultured CPS-2 43.90 Glc, Man [29] 23 Mycelium CS-Pp N.A. Glc, Gal, Man [30] 24 Cultured CS-PS 12.00 Glc, Gal, Man, Ara, Xly, Rha [31] 25 Mycelium OSP 27.97 Glc, Gal, Man, Ara, Xly, Rha, Fuc [32] 26 Mycelium HSWP-2a 870.70 Glc, Gal [33] 27 Mycelium CSPS-1 1.17 Glc, Gal, Man, Xyl, Rha [34] 28 Mycelium CS-F10 15.00 Glc, Gal, Man [35] 29 Mycelium CPs 7.70 Glc, Man [36] 30 Mycelium ICPS N.A. Glc [37] 31 Mycelium SCP-I N.A. Glc [38] 32 Mycelium P1/5 253,000.00 N.D. [12] 33 Mycelium P2/5 47,400.00 N.D. [12] 34 Mycelium P1 110.00 N.D. [12] 35 Mycelium P2 630.00 N.D. [12] 36 Mycelium P5 16.30 N.D. [12] 37 Cultured CCP 433.79 Glc [39] 38 Cultured EPS 104.00 Glc, Gal, Man [40] 39 Cultured PS-A 460.00 Glc, Gal, Man [41] 40 Mycelium EPS-LM-1 360.00 Glc, Gal, Man [42] 41 Mycelium CS-81002 43.00 Glc, Gal, Man [43] 42 Cultured EPSF N.A. N.D. [44] 43 Mycelium CAPS 27.00 Man, Rha, Glc, Gal, Xyl, Ara [45] 44 Cultured ISPS N.A. N.D. [46] 45 Mycelium CBHP N.A. Glc, Gal, Man [47] 46 Mycelium CT-4N 23.00 Gal, Man [48] 47 Mycelium PS 83.00 Glc, Gal, Man, Ara [49] M.W.: molecular weight; N.A.: not available; N.D.: not detected. Hot water extraction remains the most widely used method for isolating polysaccharides from O. sinensis mycelium. However, given the inherent time-consuming nature of conventional hot water extraction, researchers have developed several enhanced extraction techniques to improve efficiency, such as ultrasonic-assisted extraction[9], microwave-assisted extraction[10], and so on.

The isolation of extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) presents fewer technical challenges compared to intracellular polysaccharide extraction. The fermentation broth of the fungi was precipitated with ethanol to obtain crude extracellular polysaccharides. The crude polysaccharide can be further deproteinized and dialyzed. Subsequently, the processed crude polysaccharide is loaded onto ion-exchange chromatography and/or gel filtration column chromatography for gradient elution to provide homogeneous polysaccharides. Chromatography, mass spectrometry (MS), infrared spectroscopy (IR), and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) are used to analyze the structural characteristics of polysaccharides, including molecular weight, glycosidic bond configuration, monosaccharide composition, and chain conformation (Table 1). Comparative studies were conducted to evaluate structural differences in O. sinensis polysaccharides extracted using different solvent systems: (1) hot water, and (2) alkaline solution (1.25 mol/L NaOH containing 0.04% NaBH4). The results demonstrated that extraction media significantly influence polysaccharide structural characteristics, with alkaline conditions inducing substantial modifications in polymer conformation and composition[11]. The polysaccharides in a fermentation medium precipitated with different volumes of ethanol were also compared and the result proved that their molecular weight and activity were quite different[12].

Nucleosides

-

Nucleosides represent a class of glycosidic compounds formed through β-N-glycosidic bonds between pentose sugars and nitrogenous bases. These molecules serve as both bioactive constituents and key quality control markers for O. sinensis. To date, approximately 40 nucleoside derivatives have been characterized from O. sinensis, including ribonucleoside (adenosine, inosine), deoxyribonucleoside (deoxyuridine, deoxyadenosine), nucleotides (adenosine monophosphate, adenosine triphosphate) and so on (Table 2). Among these, adenosine and cordycepin have garnered particular research interest. Adenosine, specifically comprising adenine-N9 linked to D-ribose-C1 via a β-glycosidic bond, is officially recognized as a quality standard in the Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China, requiring a minimum content of 0.01%[50]. Cordycepin (3'-deoxyadenosine) holds historical significance as the first nucleoside isolated from fungal sources and continues to be a major focus of both domestic and international research due to its unique biosynthesis pathway and pharmacological potential.

Table 2. Reported active substance of O. sinensis.

Number Category Compound name Molecular formula Molecular weight (MW) Ref. 1 Nucleoside Uracil C4H4N2O2 112.09 [55, 64] 2 Nucleoside Guanosine C10H13N5O5 283.24 [55, 64] 3 Nucleoside Thymine C10H14N2O5 242.23 [64] 4 Nucleoside Inosine C10H12N4O5 268.23 [64] 5 Nucleoside Thymidine C5H6N2O2 126.11 [55, 64] 6 Nucleoside Cytosine C9H13N3O5 243.22 [64] 7 Nucleoside Adenine C5H5N5 135.13 [55, 64] 8 Nucleoside Cytidine C4H5N3O 111.10 [64] 9 Nucleoside Xanthine C5H4N4O2 152.11 [64] 10 Nucleoside Hypoxanthine C5H4N4O 136.11 [64] 11 Nucleoside 2'-deoxyuridine C10H13N5O4 267.24 [64] 12 Nucleoside Uridine C9H12N2O6 244.20 [55, 64] 13 Nucleoside Guanine C5H5N5O 151.13 [64] 14 Nucleoside Adenosine C10H13N5O4 267.24 [64] 15 Nucleoside Cordycepin C10H13N5O3 251.24 [55, 64] 16 Nucleoside 2'-Deoxyadenosine C10H13N5O2 235.24 [58] 17 Nucleoside 2'-Deoxycytidine monohydrate C9H15N3O4 227.22 [58] 18 Nucleoside 2'-Deoxyguanosine C10H13N5O4 367.24 [58] 19 Nucleoside N2,N2‐Dimethylguanosine C12H17N5O5 311.29 [65] 20 Nucleoside Adenosine monophosphate C10H14N5O7P 347.22 [58] 21 Nucleoside Adenosine diphosphate C10H15N5O10P2 427.20 [58] 22 Nucleoside Adenosine triphosphate C10H16N5O13P3 507.18 [58] 23 Nucleoside 2'-Deoxyadenylic acid C10H14N5O6P 331.22 [58] 24 Nucleoside Deoxyadenosine diphosphate C10H15N5O9P2 411.20 [58] 25 Nucleoside 5'-Guanylic acid C10H14N5O8P 363.22 [58] 26 Nucleoside Guanosine-5'-diphosphate C10H15N5O11P2 443.20 [58] 27 Nucleoside Guanosine triphosphate C10H16N5O14P3 523.18 [58] 28 Nucleoside Deoxyguanosine monophosphate C10H14N5O7P 347.22 [58] 29 Nucleoside Deoxyguanosine diphosphate C10H15N5O10P2 427.20 [58] 30 Nucleoside Cytidylic acid C9H14N3O8P 323.20 [58] 31 Nucleoside Cytidine diphosphate C9H15N3O11P2 403.18 [58] 32 Nucleoside Cytidine triphosphate C9H16N3O14P3 483.16 [58] 33 Nucleoside 2′-Deoxycytidine 5′-monophosphate C9H12N3O7P 305.18 [58] 34 Nucleoside Deoxycytidine diphosphate C9H15N3O10P2 387.18 [58] 35 Nucleoside Uridine monophosphate C9H13N2O9P 324.18 [58] 36 Nucleoside Uridine diphosphate C9H14N2O12P 404.16 [58] 37 Nucleoside Uridine triphosphate C9H15N2O15P3 484.14 [58] 38 Nucleoside Thymidine-5'-monophosphoric acid C10H15N2O8P 322.21 [58] 39 Sterol Ergosterol C28H44O 396.65 [58, 66] 40 Sterol Cholesterol C27H46O 386.65 [58] 41 Sterol Ergosteryl-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside C34H56O6 560.80 [67] 42 Sterol 22-dihydroergosteryl-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside C34H58O6 562.82 [67] 43 Sterol β-Sitosterol C29H50O 414.71 [68] 44 Sterol Stigmasterol C29H48O 412.69 [68] 45 Sterol Daucosterol C35H60O6 576.85 [68] 46 Sterol Campesterol C28H48O 400.61 [57] 47 Protein Alanine C3H7NO2 89.09 [58, 69] 48 Protein Arginine C6H14N4O2 174.20 [58, 69] 49 Protein Asparagine C4H8N2O3 132.12 [58, 69] 50 Protein Aspartic acid C4H7NO4 133.10 [58, 69] 51 Protein L(+)-Cysteine C3H7NO2S 121.16 [58] 52 Protein Glutamine C5H10N2O3 146.14 [58] 53 Protein Glutamic acid C5H9NO4 147.13 [58, 69] 54 Protein Glycine C2H5NO2 75.07 [58] 55 Protein Histidine C6H9N3O2 155.15 [58, 69] 56 Protein L-isoleucine C6H13NO2 131.17 [58, 69] 57 Protein Leucine C6H13NO2 131.17 [58, 69] 58 Protein Lysine C6H14N2O2 146.19 [58, 69] 59 Protein Methionine C5H11O2NS 149.21 [58] 60 Protein Phenylalanine C9H11NO2 165.19 [58, 69] 61 Protein Proline C5H9NO2 115.13 [58, 69] 62 Protein Serine C3H7NO3 105.09 [58, 69] 63 Protein L-Threonine C4H9NO3 119.12 [58, 69] 64 Protein Tryptophan C11H12N2O2 204.22 [58] 65 Protein Tyrosine C9H11NO3 181.19 [58, 69] 66 Protein Valine C5H11NO2 117.15 [58, 69] 67 Protein Pyroglutamic acid C5H7NO3 129.11 [65] 68 Protein Cyclo(Pro–Val) C10H16N2O2 196.25 [59] 69 Protein Cyclo(Leu–Ala) C9H16N2O2 184.23 [59] 70 Protein Cyclo(Phe–Ala) C12H14N2O2 218.25 [59] 71 Protein Cyclo(Leu–Pro) C11H18N2O2 210.27 [59] 72 Protein Cyclo(Phe–Pro) C14H16N2O2 244.29 [59] 73 Protein Cyclo(Leu–Val) C11H20N2O2 212.29 [59] 74 Protein Cyclo(Phe–Val) C14H18N2O2 246.30 [59] 75 Protein Cordycedipeptide A C10H17N3O3 227.26 [70] 76 Protein Cordyceamides A C27H28N2O5 460.52 [71] 77 Protein Cordyceamides B C27H28N2O6 476.52 [71] 78 Protein Cordymin − − [72] 79 Protein CSAP − − [60] 80 Protein CSDNase − − [60] 81 Protein CSP − − [62] 82 Protein IP4 − − [63] 83 Sugar alcohol D-mannitol C6H14O6 182.17 [73] Nucleosides, being highly polar molecules, are typically extracted using aqueous solvents (e.g., deionized water) or hydroalcoholic solutions (e.g., methanol-water mixtures). Advanced analytical techniques have been developed for the simultaneous quantification of multiple nucleosides, including HPLC-MS/MS[51], ion-pairing reversed-phase liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (IP-RP-LC-MS)[52], ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-ESI-MS/MS)[53], time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (TOF-SIMS)[2], time-of-flight mass spectrometry (QTOF-MS)[54]. These methods were used to compare the nucleoside content of O. sinensis from different origins and developmental periods. Studies have shown that the nucleoside content of wild O. sinensis in Qinghai and Tibet provinces is more dominant, and most of the nucleosides in artificially cultivated O. sinensis are higher than those in wild O. sinensis[55].

Sterols

-

Sterols are tetracyclic compounds characterized by a cyclopentane-perhydrophenanthrene ring system. Current research has identified less than ten distinct sterols in O. sinensis, including ergosterol, cholesterol, ergosteryl-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, 22-dihydroergosteryl-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, β-sitosterol, stigmasterol, daucosterol and campesterol (Table 2). Among these, ergosterol has attracted particular research interest as a fungal-specific sterol that serves as both a membrane component and the biosynthetic precursor to vitamin D2 through photochemical conversion.

Sterols, as lipophilic secondary metabolites, are typically extracted using methanol-assisted ultrasonication to enhance recovery efficiency. Analytical studies employing high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) have revealed stage-dependent variations in sterol content, with the highest concentrations observed in 4−6 cm ascostromata[56]. Comparative analyses using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) further demonstrated significant compositional differences between wild and cultivated O. sinensis specimens. The content of ergosterol in natural O. sinensis was found to be lower than that in artificially cultured O. sinensis[57].

Amino acids and peptides

-

Current proteomic analyses have identified over 30 distinct proteinaceous components in O. sinensis, encompassing free amino acids, dipeptides, and functional polypeptides (Table 2). The TOF-SIMS was used to analyze in situ chemical spectrometry and imaging spectrometry to identify 21 amino acids[58]. Several studies identified ten dipeptides in O. sinensis by UPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS/MS[59]. Polypeptides can only be obtained after purification, and these polypeptides belong to certain enzymes with unique functions, such as O. sinensis antibacterial protein (CSAP)[60], CSDNase[61], CSP[62], and IP4[63].

Others

-

In addition to its primary bioactive constituents, O. sinensis contains various metabolites, including alkenes, aromatic hydrocarbons, ketones, terpenes, and alkanes (Supplementary Table S1). Although these compounds are generally not regarded as pharmacologically active, their profiles have been characterized using advanced metabolomic techniques, such as olefins, aromatic hydrocarbons, ketones, terpenes, and alkanes. Information about these substances is often derived from metabolomic data, which are based on the technology of headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME), UPLC-ESI-Q-TOF-MS/MS, gas chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC-QTOF-MS), etc. Furthermore, environmental exposure introduces trace heavy metals into O. sinensis, such as arsenic (As), lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg), copper (Cu), silver (Ag), tin (Sn), and antimony (Sb). Due to their potential toxicity, these heavy metals are strictly regulated and serve as critical quality control markers in O. sinensis products.

Among the diverse array of bioactive compounds in O. sinensis, nucleosides are the most readily characterized components due to their relatively simple structures and the availability of established analytical methods. In contrast, polysaccharides and peptides—despite their high abundance and structural diversity—present significant analytical challenges owing to their macromolecular nature and structural complexity. Notably, these high-molecular-weight compounds demonstrate remarkable bioactivity and represent the fundamental pharmacodynamic basis for O. sinensis's therapeutic effects. However, limited by detection methods and the shortage of biological resources, the current research on this aspect is still very scarce, and new methods need to be found for breakthroughs.

-

Recent breakthroughs in multi-omics technologies have enabled comprehensive characterization of O. sinensis at molecular levels, including its transcriptome, proteome, and genome. A major milestone was achieved in 2017 with the first assembly of highly contiguous genome sequences for this species[74]. With the assistance of the genome information, the genes related to growth and development and secondary metabolism in O. sinensis were gradually excavated[74,75]. This species exhibits unique growth and developmental processes, the molecular mechanisms of which have attracted significant research interest. Comparative transcriptomic and proteomic analyses across distinct developmental stages of fruiting bodies have emerged as effective methodologies. Through these approaches, differentially expressed genes have been systematically screened and characterized, enabling researchers to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying these biological processes[4, 76–77]. These results suggest that genes associated with the cAMP signaling pathway, carbohydrate metabolism (including starch, sucrose, fructose, and mannose metabolism), energy metabolism, protein metabolism, cell remodeling, and lipid metabolism (linoleic acid degradation, fatty acid catabolism, glycerophospholipid metabolism) are upregulated during fruiting body development. This indicates heightened demand for protein synthesis and energy production to support this process. Transcriptome sequencing of infected larvae—categorized into proliferative, stationary, precourtship, and courtship phases—demonstrated the critical role of lipid accumulation and mobilization in filamentous growth[78]. Comparative analysis of gene expression profiles in hyphal bodies pre- and post-infection identified candidate genes potentially pivotal to larval infection[79].

However, research on secondary metabolite biosynthesis remains limited, with current findings primarily based on predictive models. The analysis of their metabolic pathways is conducive to the production of secondary metabolites in vitro by techniques of synthetic biology. At present, important compounds such as ginsenosides, flavonoids, and artemisinin have been efficiently synthesized using microorganisms[80,81]. Similarly, the same methods can be replicated in O. sinensis after the related genes have been identified.

Cordycepin

-

Since its discovery, cordycepin has garnered significant research interest. Elucidating its biosynthetic pathway has been a complex and evolving endeavor. Early hypotheses proposed that cordycepin is directly synthesized through the formation of a glycosidic bond between 3’-deoxyribose and adenine. Subsequent studies, however, demonstrated that exogenous supplementation with adenine or adenosine significantly enhances cordycepin production, indicating their role as potential precursors[82]. Advances in whole genome sequencing and bioinformatic analyses of Cordyceps species have progressively elucidated the biosynthetic pathway of cordycepin.

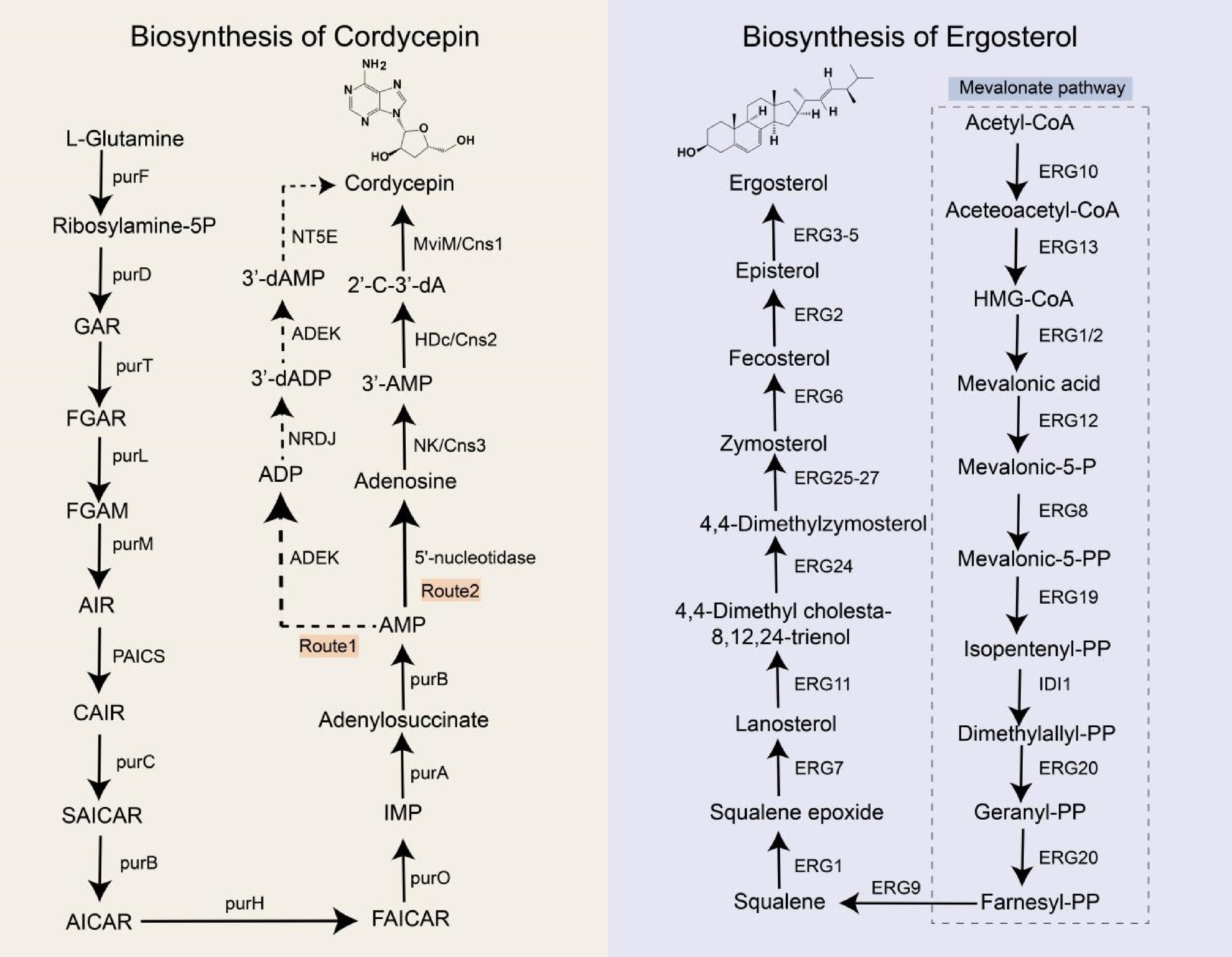

In 2011, the whole genome sequencing of Cordyceps militaris—a species taxonomically related to O. sinensis—was completed[83]. Genome annotation of C. militaris identified key genes involved in adenine and adenosine metabolism, enabling researchers to propose a biosynthetic pathway for cordycepin based on known enzymatic functions (Fig. 2). The pathway proceeds as follows (Route1): adenosine monophosphate (AMP) is phosphorylated to adenosine diphosphate (ADP) by adenylate kinase (ADEK). ADP is then reduced to 3'-deoxyadenosine-5'-diphosphate (3'-dADP) via ribonucleotide reductase (RNR). ADEK subsequently catalyzes the conversion of 3'-dADP to 3'-deoxyadenosine-5'-phosphate (3'-dAMP), which is dephosphorylated to cordycepin by 5'-nucleotidase (NT5E). Similar pathways were later hypothesized for O. sinensis and Hirsutella sinensis in 2014 and 2016[84,85]. However, experimental validation of this pathway remains lacking. Furthermore, heterologous expression of the RNR subunits CmR1 and CmR2 from C. militaris in Escherichia coli revealed that these enzymes catalyzed ADP conversion to 2'-deoxy-ADP (2'-dADP) but not 3'-dADP, suggesting alternative metabolic routes for cordycepin biosynthesis[86].

Figure 2.

Biosynthetic pathways of cordycepin and ergosterol. purF: glutamine phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate amidotransferase; purD: phosphoribosylglycinamide formyltransferase; purT: glycinamide ribonucleotide transformylase; purL: formylglycinamide ribonucleotide amidotransferase; purM: aminoimidazole ribonucleotide synthetase; PAICS: phosphoribosylaminoimidazole carboxylase; purC: phosphoribosylaminoimidazole-succinocarboxamide synthase purB: adenylosuccinate lyase; purH: hypoxanthine nucleotide dehydrogenase; purO: puromycin acetyltransferase; purA: adenylosuccinate synthetase; ADEK: adenylate kinase; NRDJ: ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase; NT5E: 5'-nucleotidase; ERG10: acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase; ERG13: 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase; ERG1: squalene monooxygenase; ERG2: lanosterol dehydrogenase; ERG12: mevalonate kinase; ERG8: phosphomevalonate kinase; ERG19: lanosterol synthase; IDI1: isopentenyl-diphosphate delta-isomerase 1; ERG20: farnesyl diphosphate synthase; ERG9: squalene synthase; ERG7: lanosterol synthase; ERG11: lanosterol 14α-demethylase; ERG24: C-14 sterol reductase; ERG25: sterol C-4 methyl oxidase; ERG26: 3β-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; ERG27: 3-ketosteroid reductase; ERG3: C-5 sterol desaturase; ERG4: C-24(28) sterol reductase; ERG5: sterol C-22 desaturase; GAR: glycinamide ribonucleotide; FGAR: formylglycinamide ribonucleotide; FGAM: formylglycinamide ribonucleotide amide; AIR: aminoimidazole ribonucleotide; CAIR: carboxyaminoimidazole ribonucleotide; SAICAR: N-Succinyl-5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide; AICAR: 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide; FAICAR: 5-formamidoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide; IMP: inosine monophosphate; AMP: adenosine monophosphate; ADP: adenosine diphosphate; 3’-dADP: 3'-deoxyadenosine diphosphate; 3'-dAMP: 3'-deoxyadenosine monophosphate; 2'-C-3'-dA: 2'-C-3'-dideoxyadenosine.

To elucidate the biosynthetic pathway of cordycepin in C. militaris, genes encoding adenine phosphoribosyltransferase (cmAPRT), 5'-nucleotidase (cmNT5E), and nucleoside triphosphate pyrophosphatase (cmNTP) were knocked out. Disruption of these genes did not affect cordycepin production. Given that Aspergillus nidulans also synthesize cordycepin, researchers hypothesized that C. militaris and A. nidulans share conserved genes critical for its biosynthesis[87]. Comparative genomic analysis revealed a cluster of closely arranged, highly homologous protein-coding genes (Cns1–Cns4) in both species. Functional characterization indicated that Cns1 encodes an oxidoreductase, Cns2 a metal-dependent phosphohydrolase, Cns3 an ATP-dependent phosphotransferase, and Cns4 an ABC-type transporter. Knockout and heterologous expression of Cns1–Cns4 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Metarhizium robertsii confirmed that Cns1 and Cns2 are essential for cordycepin biosynthesis, while Cns3 participates in pentostatin synthesis and Cns4 likely encodes a pentostatin transporter. The proposed pathway involves three enzymatic steps (Route 2): (1) Cns3 catalyzes the conversion of adenosine to 3'-AMP; (2) Cns2 reduces 3'-AMP to 2'-carbonyl-3'-deoxyadenosine (2'-C-3'-dA); and (3) Cns1 mediates dephosphorylation of 2'-C-3'-dA to yield cordycepin. Homologous pathways have been identified in Cordyceps kyushuensis Kob and C. cicadae[88,89]. Notably, some scholars think that O. sinensis does not naturally have cordycepin-associated biosynthetic genes, so it is impossible to contain cordycepin[87]. However, even with congeneric relationships, certain species may have evolved unique branching pathways to produce secondary metabolites. Therefore, this view needs further confirmation.

Ergosterol

-

Ergosterol serves as the primary sterol component in fungal cell membranes. Fungicides targeting ergosterol biosynthesis enzymes are extensively employed in agricultural and clinical settings, leading to widespread resistance in fungal species[90]. To address this, the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway has been systematically characterized in the model organism Saccharomyces cerevisiae[91] (Fig. 2).

Ergosterol synthesis is a multi-step enzymatic process requiring energy, oxygen, and heme as cofactors. The pathway initiates with acetyl-CoA and proceeds through two phases: (1) the mevalonate (MVA) pathway, culminating in farnesyl pyrophosphate synthesis, and (2) the post-squalene pathway, beginning with squalene. The MVA pathway is tightly regulated and evolutionarily conserved across mammals, plants, and fungi. Gene knockout studies demonstrate that MVA pathway genes are essential for fungal viability, as their disruption results in lethality[92], rendering them promising antifungal targets. In contrast, the post-squalene pathway exhibits lower conservation, and its associated genes are non-essential for growth.

Current research predominantly focuses on ergosterol biosynthesis in human and plant pathogens, with extensive mutagenesis and gene knockout studies. However, this pathway remains poorly characterized in medicinal fungi, highlighting a critical knowledge gap.

Polysaccharide

-

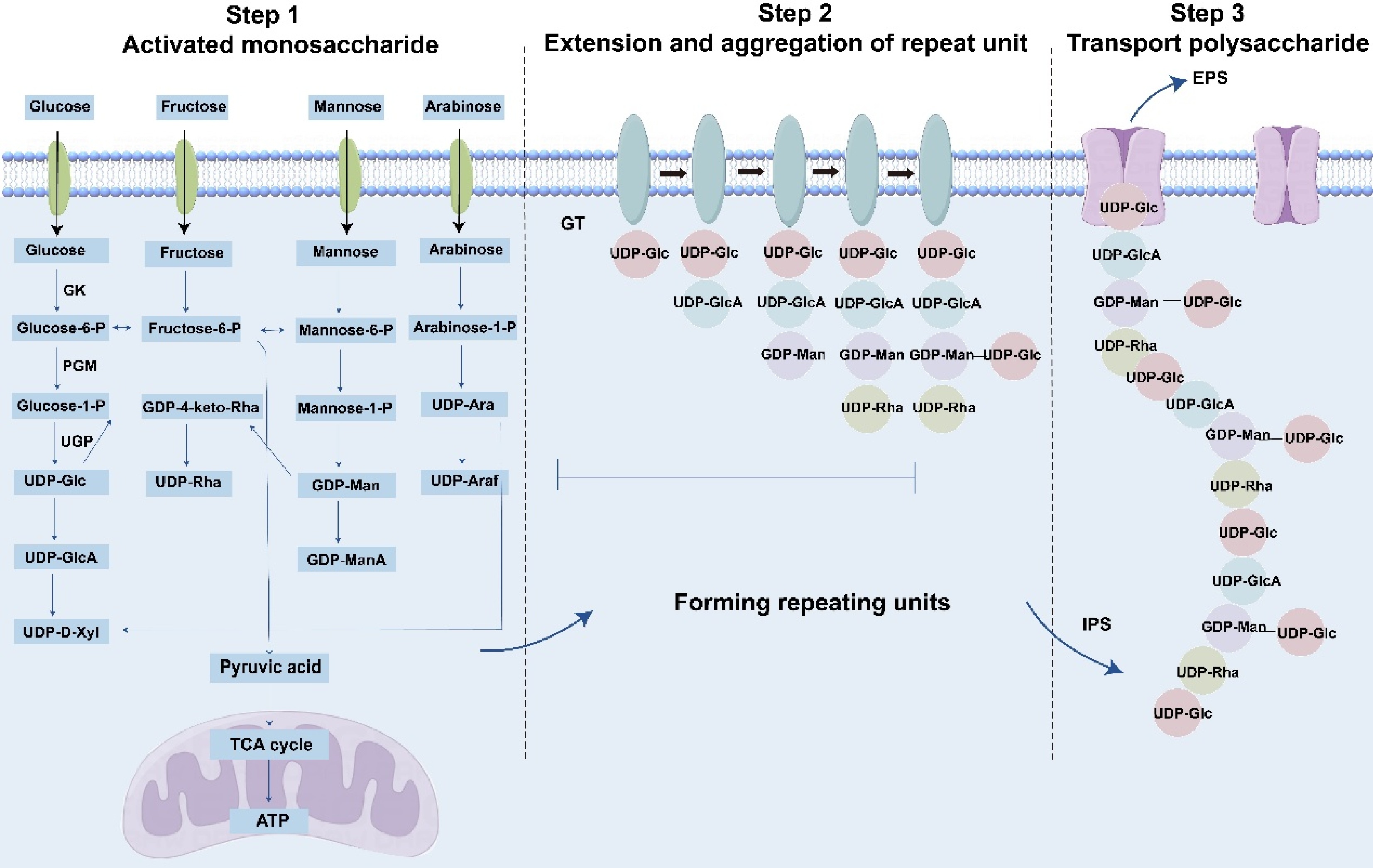

Polysaccharides are critical macromolecules in O. sinensis. Owing to their structural complexity, limited foundational research exists on their biosynthesis. Within the Cordyceps genus, polysaccharide biosynthesis remains largely uncharacterized. However, as numerous fungal species synthesize polysaccharides through evolutiona-rily conserved biosynthetic and transport mechanisms, insights from these species may inform research on O. sinensis[93]. Fungal polysaccharides are categorized into three classes: extracellular, intracellular, and cell wall polysaccharides. The latter includes O-antigen polysaccharides, a structurally distinct subgroup. Biosynthesis involves four key steps: (1) synthesis of nucleotide-activated sugar precursors, (2) initiation of glycan assembly, (3) elongation, modification, and polymerization of oligosaccharide repeat units, and (4) translocation of mature polysaccharides (Fig. 3)[94].

Figure 3.

Biosynthesis of polysaccharides. The monosaccharides depicted in the figure represent a subset and do not encompass the full diversity of known structures. GK: glucokinase; PGM: phosphoglucose-mutase; UGP: uridylyltransferase; GT: glycosyl transferase; IPS: Intercellular Polysaccharide; EPS: exopolysaccharides.

Natural monosaccharides lack reactive sites for polymerization. Upon entering the mycelium, they undergo activation to form nucleotide-activated sugar donors essential for polysaccharide biosynthesis. Using glucose as a model substrate: (1) glucose is phosphorylated to glucose-6-phosphate by glucokinase (GK), (2) α-phosphoglucose mutase (PGM) isomerizes glucose-6-phosphate to glucose-1-phosphate, and (3) uridylyltransferase (UGP) catalyzes the synthesis of UDP-glucose. UDP-glucose serves as a precursor for derivatives such as UDP-glucuronic acid, UDP-xylose, TDP-glucose, TDP-rhamnose, and GDP-mannose. Concurrently, fructose-6-phosphate generated during glycolysis is metabolized via pyruvate to either lactate (via anaerobic fermentation) or ATP (via the citric acid cycle), the latter directly fueling polysaccharide synthesis[95]. Similar activation mechanisms apply to fructose, galactose, mannose, and arabinose. Microorganisms accumulate nucleotide-activated sugars but require enzymatic catalysis for polymerization. Polysaccharide biosynthesis typically involves glycosyltransferases (GTs) that assemble monosaccharides onto lipid carriers to form repeating units, which may be homogeneous or branched[96]. These units are subsequently polymerized into intracellular polysaccharides (IPS) via three pathways: Wzy-dependent, ABC transporter-dependent, or synthase-dependent mechanisms[97]. Extracellular polysaccharide (EPS) translocation may occur at any biosynthetic stage[98].

Polysaccharide biosynthetic genes often cluster within genomes, encoding enzymes for monosaccharide activation, glycan assembly, structural modification, and transport[99]. Researchers enhance polysaccharide yields by overexpressing repeat unit synthesis genes or supplementing monosaccharide donors[100]. Despite these advances, the biosynthetic pathways in O. sinensis remain poorly characterized, with limited mechanistic insights into its polysaccharide diversity. Identifying key enzymes will elucidate structural variability and advance targeted biosynthesis.

The enzymatic machinery underlying bioactive compound biosynthesis in O. sinensis remains largely uncharacterized, with existing insights primarily confined to related species such as C. militaris. Advances in genome sequencing and assembly have enabled the prediction and functional validation of candidate biosynthetic enzymes through heterologous expression in model systems (e.g., yeast or tobacco). Elucidating these enzymatic roles is critical for optimizing the production, bioactivity, and commercial viability of O. sinensis-derived metabolites.

-

O. sinensis exhibits prominent pharmacological properties, including immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antitumor activities. Clinically, it is employed in managing diabetes and renal disorders, as well as a nutraceutical adjuvant. Although multiple bioactive compounds have been isolated from this species, systematic investigations into their mechanisms of action remain incomplete, necessitating further mechanistic and translational studies.

Immunomodulatory

-

The primary class of immunomodulatory components in O. sinensis comprises polysaccharides (Supplementary Table S2, Fig. 4). Cellular experiments demonstrated that these polysaccharides enhance immune activity by stimulating macrophages, promoting nitric oxide (NO) production, upregulating cytokine secretion, and activating signaling pathways (p38, JNK, and NF-κB). To compare antitumor and immunostimulatory effects, water-insoluble polysaccharides (WIPS) and alkali-insoluble polysaccharides (AIPS) were isolated and purified from hot water and alkaline extracts of O. sinensis mycelia, respectively. Results indicated that AIPS exhibited the highest efficacy[11]. Further studies revealed that exopolysaccharides from cultivated O. sinensis enhanced lymphocyte proliferation in the Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) mice by inducing tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) expression[40]. In γ-irradiated mice, aqueous extracts of O. sinensis mitigated irradiation-induced immunosuppression by upregulating B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) and downregulating BCL2-associated X (Bax) and cleaved caspase-3 in splenic tissue[101]. Sphingolipid fractions from O. sinensis mycelia demonstrated immunosuppressive activity by inhibiting B-cell and T-cell proliferation and reducing interleukin-2 (IL-2), interleukin-10 (IL-10), and TNF-α production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)[102].

Antioxidant

-

Pharmacological studies have shown that the antioxidant of O. sinensis is attributable to its polysaccharides and peptides (Supplementary Table S2, Fig. 4). The antioxidant ability of water extracts of natural O. sinensis and cultured O. sinensis mycelia were analyzed by three different assay methods. The result showed that the cultured mycelia had equally strong anti-oxidation activity as compared to the natural O. sinensis[103]. In addition, the in vitro antioxidant activities of polysaccharides from wild and cultivated O. sinensis were similar[13]. The polysaccharide from nature O. sinensis was proven to increase the total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) and increase the activities of superoxidase dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), and catalase (CAT) in the liver significantly in intestinal immunosuppressed mice[104]. Cordymin, a peptide purified from O. sinensis, could increase antioxidant activity related to lesion pathogenesis, further generating the neuroprotective effect in the ischemic brain[105]. Studies have also shown that adding cellulase to the fermentation products of O. sinensis can improve its antioxidant activity[106]. H22-bearing mice experiment revealed that the polysaccharide significantly enhanced the SOD activity of the liver, brain, and serum as well as GSH-Px activity of the liver and brain in tumor-bearing mice[107].

Anti-inflammatory

-

The anti-inflammatory effects of O. sinensis are mediated by diverse classes of bioactive compounds, including peptides, nucleosides, and polysaccharides (Supplementary Table S2, Fig. 4). In a study investigating O. sinensis in a right middle cerebral artery occlusion model cordymin significantly inhibited polymorphonuclear cell infiltration and attenuated ischemia-reperfusion (IR)-induced upregulation of brain C3 protein levels[105]. Mechanistic studies on CPS-F, a polysaccharide from O. sinensis, revealed its dual anti-inflammatory action: it suppresses platelet-derived growth factor BB (PDGF-BB)-induced intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and downregulates tumor necrosis factor (TNF), TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1), and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1). Furthermore, CPS-F acts synergistically with the MAPK/ERK inhibitor U0126 and PI3K/Akt inhibitor LY294002[108]. In vivo and in vitro experiments demonstrated that O. sinensis extract attenuates extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) signaling, thereby suppressing nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activity in lung cells and cultured airway smooth muscle cells, which reduces airway inflammation in ovalbumin-induced allergic mice[109]. Cordycepin, another key component, exhibits protective effects against inflammatory injury in pathologies such as acute lung injury (ALI), asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, Parkinson's disease (PD), hepatitis, atherosclerosis, and atopic dermatitis. This compound modulates multiple signaling pathways, including NF-κB, receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 2/caspase-1 (RIP2/Caspase-1), Akt/GSK-3β/p70S6K, TGF-β/Smads, and Nrf2/HO-1[110]. Additionally, a study evaluating bifidobacterial fermentation of EPS-LM (a polysaccharide) found that partially degraded high-molecular-weight (MW) fractions exhibited stronger inhibitory activity than native EPS-LM on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced pro-inflammatory responses in THP-1 monocytes, including NF-κB activation and nitric oxide (NO), TNF-α, and interleukin-8 (IL-8) release[3].

Antineoplastic

-

O. sinensis exhibits demonstrable antineoplastic activity (Fig. 4). Researchers compared antitumor efficacy among solvent-based extracts of O. sinensis mycelia using cultured cancer cell lines and B16 melanoma-bearing C57BL/6 mice. Ethyl acetate extract displayed the most potent activity, suppressing proliferation across all four cancer cell lines and reducing tumor volume by approximately 60% in mice over 27 d[111]. Polysaccharides extracted from aqueous and alkaline aqueous solvents were evaluated for antitumor and immunostimulatory effects, with alkaline-derived polysaccharides demonstrating superior efficacy in animal models[11]. Two novel sterols, 5α,8α-epidioxy-24(R)-methylcholesta-6,22-dien-3β-D-glucopyranoside and 5,6-epoxy-24(R)-methylcholesta-7,22-dien-3β-ol, isolated from O. sinensis methanol extract, exhibited potent inhibition of proliferation in K562, WM-1341, HL-60, and RPMI-8226 tumor cell lines[67]. Mechanistic studies on O. sinensis polysaccharides revealed their ability to suppress human colon cancer cell proliferation by enhancing autophagy and apoptosis. These effects correlate with reduced expression of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), alongside decreased phosphorylation of protein kinase B (AKT) and mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR). Concurrently, polysaccharides upregulated AMP-activated protein kinase alpha (AMPKα) and phosphorylation of Unc-51-like autophagy-activating kinase 1 (ULK1)[34].

Others

-

Pharmacological studies have demonstrated that O. sinensis exhibits diverse biological activities, including antibacterial, anti-aging, antihypertensive, and antidiabetic effects, as well as inhibition of human platelet activation and regulation of sex hormone secretion (Supplementary Table S2). In an antimicrobial assay, CSAP, a protein purified from O. sinensis, was observed to exhibit bacteriostatic rather than bactericidal activity[60]. Cultured O. sinensis extracts were found to suppress the ROS/PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and reduce cigarette smoke extract (CSE)-induced cellular senescence[112]. To investigate the antihypertensive mechanism of a polysaccharide fraction (CSP1) from O. sinensis, hypertensive rats were utilized as an animal model. Pharmacological analyses revealed that CSP1 lowers blood pressure by stimulating vasodilator nitric oxide (NO) secretion, reducing levels of endothelin-1 (ET-1), epinephrine, noradrenaline, and angiotensin II, suppressing transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) upregulation, and decreasing the inflammatory mediator C-reactive protein (CRP)[28]. A rodent study demonstrated that the Bailing Capsule attenuates renal triglyceride accumulation in diabetic rats by modulating the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) pathway[113]. To investigate the therapeutic effects of cultivated O. sinensis (ACOS), a rat model of diabetic nephropathy (DN) was utilized. Results revealed that ACOS inhibits the overexpression of the purinergic 2X7 receptor (P2X7R) and suppresses activation of the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome, key mediators of DN pathogenesis, suggesting a mechanism underlying its efficacy[114]. In a separate study, immunoblotting, flow cytometry, and platelet functional analyses were employed to evaluate the antiplatelet activity of CME-1, a purified polysaccharide. CME-1 exhibited potent antithrombotic effects, likely mediated by adenylate cyclase/cyclic AMP activation and downstream inhibition of intracellular signaling pathways[115]. Additionally, O. sinensis extracts stimulate testosterone production in both in vivo and in vitro models[116]. Cell-based experiments further indicate that the protective effects of O. sinensis may be attributed to its bioactive polysaccharides and cordycepin derivatives[117−119].

In summary, O. sinensis, a prized Chinese medicinal material with considerable scientific interest and commercial demand, exhibits diverse pharmacological properties that have been partially characterized. Despite progress, significant potential remains for elucidating its mechanisms of action and bioactive constituents. Further mechanistic studies and rigorous identification of its active compounds are essential for enhancing its therapeutic value, securing its commercial viability, and developing high-efficacy health products.

-

O. sinensis, a historically significant and pharmacologically valuable traditional Chinese medicine, has garnered substantial scientific and commercial interest. Its primary bioactive constituents include polysaccharides, nucleosides, sterols, amino acids, and peptides. Pharmacological studies highlight its immunomodulatory, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antineoplastic properties. Numerous commercial formulations containing O. sinensis are available, reflecting its substantial market demand. This review synthesizes current research on O. sinensis, focusing on its biological activities, chemical constituents, and key biosynthetic pathways. Nevertheless, critical gaps persist in understanding its molecular mechanisms and metabolic networks, warranting further investigation to optimize its therapeutic applications.

The quality control of O. sinensis should be improved

-

The surge in market demand for O. sinensis has led to the overexploitation of wild populations, necessitating sustainable alternatives to address conservation challenges. Consequently, cultivated O. sinensis and its mycelium have emerged as commercially viable substitutes. However, cultivated and wild O. sinensis occupy distinct ecological niches, resulting in variability in medicinal quality. Furthermore, wild O. sinensis hosts diverse fungal communities, with significant heterogeneity in secondary metabolite profiles among these symbiotic species, posing challenges in standardizing bioactive compounds. Current pharmacopeial standards, which focus on limited chemical markers, are inadequate to comprehensively assess the medicinal value of O. sinensis. Revising pharmacopeial benchmarks to incorporate multifactorial quality indicators is imperative. Establishing such biomarkers will be critical for ensuring product consistency, ecological sustainability, and therapeutic efficacy.

The structure and activity of the macromolecular substance of O. sinensis need to be further clarified

-

Elucidating the bioactive constituents of O. sinensis remains a critical scientific challenge. Recent comparative analyses of O. sinensis and related species, such as C. militaris, have revealed notable differences in their chemical and pharmacological profiles. Specifically, C. militaris exhibits higher concentrations of bioactive monomers, including cordycepin and adenosine—compounds traditionally associated with therapeutic efficacy. Despite these findings, O. sinensis retains its historical distinction as one of the 'three treasures of traditional Chinese medicine', a status not conferred upon C. militaris. This discrepancy raises questions about whether the unique value of O. sinensis may derive from understudied macromolecular complexes or trace compounds rather than monomeric constituents. Current limitations in characterizing high-molecular-weight metabolites and synergistic interactions hinder a comprehensive understanding of their pharmacological mechanisms. Resolving these ambiguities will require advanced analytical methodologies to decode the intricate chemistry of O. sinensis.

The chemical structure of polysaccharides exhibits considerable diversity and complexity. While numerous studies have successfully isolated homogeneous polysaccharides and characterized their structures, significant discrepancies exist among the structures reported by different research groups using distinct fungal strains[120]. This variability likely stems from multiple factors, including strain-specific genetic differences, variations in culture media, divergent isolation methodologies, and experimental protocols. A critical breakthrough in this field would involve elucidating the genetic mechanisms underlying these strain-dependent differences in polysaccharide production. Furthermore, the structure-activity relationship of polysaccharides remains unclear. Current research on polysaccharide biosynthesis and structure-efficacy correlations remains limited, likely constrained by existing analytical methodologies for polysaccharide detection and characterization.

Polypeptides represent a prominent focus in contemporary drug development. Currently, only a limited number of peptides have been isolated from O. sinensis, likely due to challenges in extraction efficiency and the substantial cultivation costs associated with this species. Emerging technologies such as microbial fermentation and multi-omics approaches offer promising solutions to these limitations. These methods enable the heterologous expression of specific peptides in microbial systems, facilitating cost-effective, high-yield production similar to established biotechnological processes like insulin manufacturing[121]. Despite these technological advances, research on O. sinensis-derived peptides remains underdeveloped compared to other bioactive compounds.

The interaction mechanism between O. sinensis and the environment needs to be further demonstrated

-

Unlike C. militaris, which exhibits a global distribution, O. sinensis is endemic to China, and restricted to low-temperature, high-altitude regions such as Tibet, Sichuan, and Qinghai. The life cycle of O. sinensis is closely linked to its habitat, with critical distributional drivers including altitude, oxygen availability, climate, terrain, soil composition, and vegetation[122,123]. Molecular mechanisms underlying plant responses to environmental factors have been extensively studied. For instance, cold-resistance proteins and transcription factors in Arabidopsis thaliana have been well-characterized[124], and genes involved in arsenic hyperaccumulation in Pteris vittata have been identified[125]. However, research on the molecular mechanisms of O. sinensis remains largely unexplored. The identification of the interaction mechanism between O. sinensis and the strict environment could optimize artificial cultivation protocols, alleviating resource scarcity and ensuring long-term sustainability.

Artificial cultivation of O. sinensis and cultivated mycelium greatly alleviated the resource pressure

-

Wild O. sinensis exhibits a prolonged growth cycle and stringent environmental requirements, rendering artificial cultivation the only feasible method for large-scale production. Chinese researchers have isolated multiple low-temperature-adapted O. sinensis strains through tissue culture and ascospore separation techniques[126]. Leveraging advanced fermentation technologies, functionally diverse strains can be systematically screened to produce bioactive compounds. Notably, mycelia—characterized by rapid growth cycles—synthesize metabolites analogous to those in wild O. sinensis. Industrial-scale fermentation enables efficient, short-term production of these bioactive substances, which are commercially formulated into powdered supplements (e.g., Bailing capsules, Jinshuibao capsules)[127,128].

The isolation of mycelial cultures established the foundation for subsequent artificial cultivation of O. sinensis. Chinese researchers have successfully cultivated O. sinensis—the fungus that parasitizes bat moth larvae—in low-altitude regions, thereby reducing pressure on both natural resources and the environment. Cultivated O. sinensis exhibits comparable chemical composition to wild specimens, enabling partial market substitution[129]. Further elucidation of O. sinensis growth mechanisms and biochemical profiles will facilitate the development of cultivated strains that more closely resemble wild varieties.

This study was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (Grant No. 2024YFD2100701), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82474038), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central public welfare research institutes (Grant No. ZXKT21034).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceived the project and supervised the study: Xiang L; collected the literature and drew the figures: Wang W; wrote the first draft: Wang W, Gao R; collected a part of the literatures: Cheng C, Wu H; summarized the tables, modified the figures, and provided research guidance: Shi Y, Wu L, Yin Q, Wang M; reviewed, edited, and finalized the manuscript: Liu Y, Yuan L, Xiang L, Gao R. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Reported compounds of Ophiocordyceps sinensis.

- Supplementary Table S2 Pharmacological study of Ophiocordyceps sinensis.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang W, Cheng B, Wu H, Shi Y, Wu L, et al. 2025. Composition, biosynthesis and pharmacological activities of chemical constituents of Ophiocordyceps sinensis: a review. Medicinal Plant Biology 4: e026 doi: 10.48130/mpb-0025-0024

Composition, biosynthesis and pharmacological activities of chemical constituents of Ophiocordyceps sinensis: a review

- Received: 14 February 2025

- Revised: 22 April 2025

- Accepted: 20 May 2025

- Published online: 25 July 2025

Abstract: Ophiocordyceps sinensis (syn. DongChongXiaCao), a rare and endemic medicinal fungus native to China, possesses significant pharmacological and commercial value. However, the chemical composition, pharmacological mechanisms, and biosynthetic pathways of secondary metabolites in O. sinensis remain largely uncharacterized, hindering efforts to enhance its quality and develop derived products. This review summarizes the resource status, chemical constituents, and pharmacological properties of O. sinensis, with a focus on the omics research progress and the biosynthetic pathways of key secondary metabolites such as cordycepin, ergosterol, and polysaccharides. Modern pharmacological studies reveal that O. sinensis exhibits immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, anti-aging, antihypertensive, and antioxidant activities, primarily attributed to its polysaccharides, nucleosides, sterols, and peptides. Despite advancements in omics technologies for studying its unique developmental mechanisms and secondary metabolite biosynthesis, knowledge in this field remains limited, especially compared with congeneric species. Finally, future research directions, including the development of quality biomarkers, exploration of complex macromolecules, investigation of O. sinensis-environment interactions, and artificial cultivation techniques, are proposed to alleviate resource scarcity. This review highlights current research gaps and provides actionable solutions, laying a foundation for the subsequent development of related products and the sustainable utilization of O. sinensis.

-

Key words:

- Ophiocordyceps sinensis /

- Bioactive substance /

- Pharmacological activity /

- Biosynthesis