-

The shallow subsurface is the important domain of Earth’s critical zone, supporting essential life-sustaining processes such as water cycling, substance transformation, and element cycling[1]. Among these processes, redox reactions are central processes to maintain water quality, ecosystem stability, and the global carbon (C) balance, which control the transformation and mobility of contaminants in the subsurface[2,3]. Fundamentally, redox reactions are driven by the flow of electrons, making electron transfer (ET) the key underlying mechanism. These redox reactions govern the energy available for microbial growth, which, in turn, controls the bioavailability of nutrients and pollutants, and drives the chemical weathering of rocks and minerals[4−6]. Therefore, ET is a core process governing energy flows and biogeochemical dynamics in the subsurface. A comprehensive understanding of the patterns and mechanisms of ET is thus essential for revealing the biogeochemical processes and guiding strategies in environmental prediction, management, and remediation in the subsurface.

ET typically occurs between redox couples at redox interfaces. In the subsurface, however, ET can span a wide range of spatial scales from molecular-level interactions to centimeter-scale processes, resulting from the presence of diverse redox interfaces. Generally, subsurface environments are under reducing conditions, in which the redox-active species such as iron (Fe), sulfur (S), and natural organic matter (NOM) predominantly exist in their reduced states. These reduced species act as reductants to release electrons, and some redox-active species (e.g., redox-active minerals and NOM) can function as ET mediators[3]. Natural processes and anthropogenic activities such as water table fluctuations, surface water–groundwater interactions, and groundwater extraction can introduce oxidants (e.g., O2, nitrate, or other chemical oxidants) into the subsurface[7−9], which, in turn, leads to the formation of redox interfaces across various spatial scales. At these redox interfaces, ET typically occurs between oxidants and reductants, either through direct ET or via ET mediators. At microscopic interfaces, ET is short-distance (nano- to microscale), nondirectional, and confined to redox microsites such as mineral–solution[10], microbe–solution[11,12], and microbe–mineral[13] interfaces. Centimeter-scale ET has been observed in marine sediments: (semi)conductive minerals such as pyrite can support ET over distances of 1 cm or more[14], and cable bacteria are capable of directly mediating centimeter-scale ET across distances exceeding 1.5 cm, linking surface oxygen (O2) reduction to deep sulfide oxidation[15]. Recently, electron hopping between reduced and oxidized NOM was documented to facilitate long-distance ET between microbes and Fe(III) minerals over a 2 cm distance in an agar-solidified system[16−18]. Further, a recent study has shown that a series of short-distance ETs could be directionally connected to form a long-distance ET chain along redox gradients, reaching a distance of up to 10 cm or more[19]. These findings expand the traditional view that ET is limited to short-distance redox interfaces, demonstrating that ET can occur over centimeter scales, extending beyond localized microsites to macroscopic and aquifer-relevant scales.

The above-mentioned studies revealed that ET in the subsurface occurs across different scales, which indicates that ET is far more dynamic and complex than previously recognized. However, a comprehensive understanding of how different scales of ET occur in the surface remains unclear. In this review, we aim to develop a theoretical framework of ET patterns and mechanisms across different scales in the subsurface. Beyond the traditionally emphasized nano- to microscale redox interfaces, we highlight the need to consider long-distance ET and its environmental implications. To address this, we systematically review (1) the key mediators involved in ET, (2) the formation and characteristics of redox interfaces, (3) the classification and mechanisms of ET processes from nanometer to meter scales, and (4) the environmental implications of ET in biogeochemical cycling and contaminant dynamics. Finally, we offer perspectives on the current knowledge gaps and future research directions, aiming to inform theoretical frameworks and practical strategies for subsurface environmental management.

-

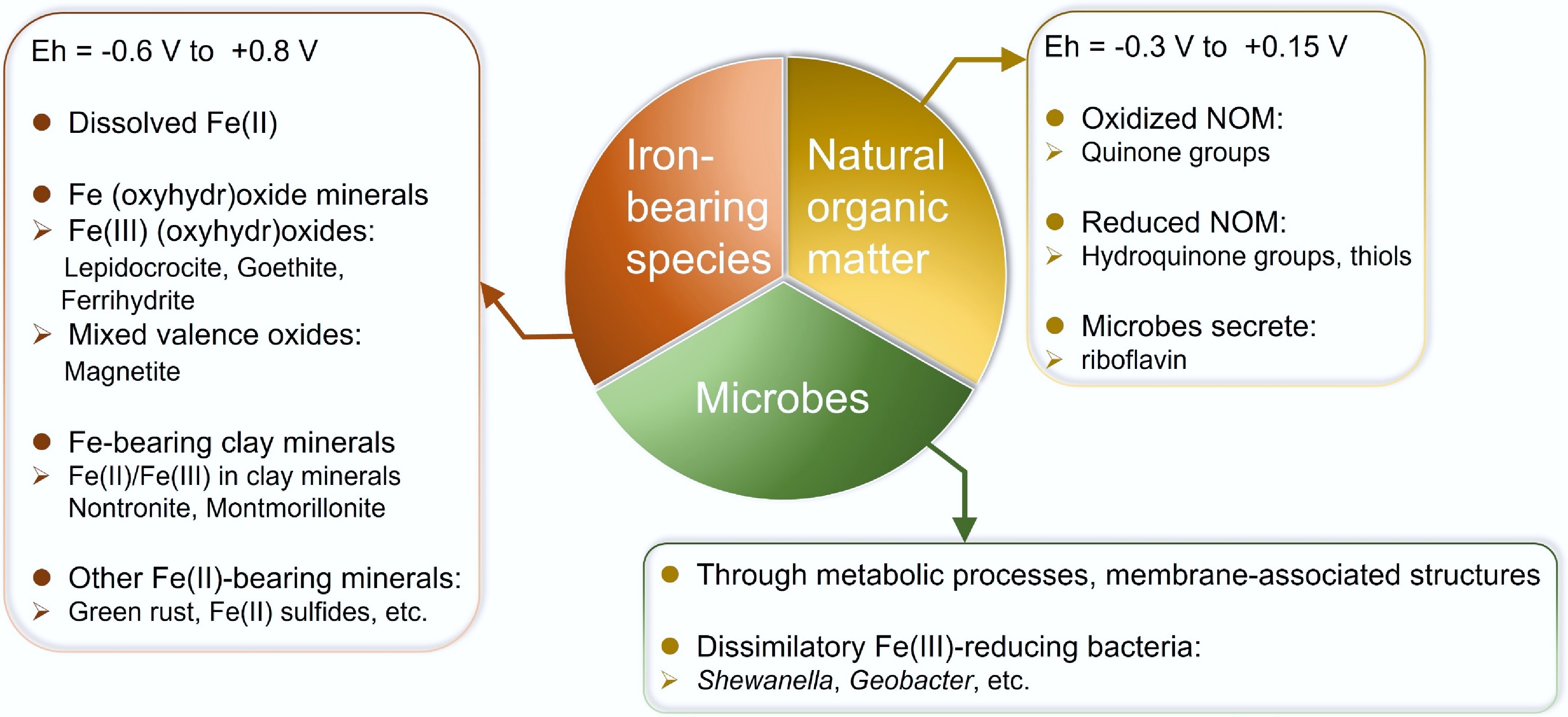

Redox-active species are key drivers of ET processes in the subsurface. They can function as various ET mediators such as electron donors by releasing electrons, or electron acceptors by accepting electrons, thereby participating in redox reactions[2]. During reactions, redox-active species typically undergo stoichiometric oxidation or reduction, yielding corresponding reaction products. In addition to functioning as electron donors and electron acceptors, some species can also function as electron carriers, shuttling electrons between separated redox couples and linking multiple redox reactions[20−22]. In the subsurface, common ET mediators include Fe-bearing compounds, NOM, and microbially derived molecules such as flavins and quinones (Fig. 1), all of which play important roles in facilitating ET and sustaining biogeochemical reactions[3,23−25].

Iron-bearing species

-

Redox-active Fe-bearing species in the subsurface include mainly dissolved Fe(II), Fe (oxyhydr)oxide minerals, Fe-bearing clay minerals, and other Fe(II)-bearing minerals (Fig. 1). Their Eh (reduction potential) refers to the tendency of a chemical species to gain or lose electrons. The typical Eh range is from −0.6 to +0.8 V versus a standard hydrogen electrode (SHE), depending on factors such as the ligand chemistry, mineral structure, Fe(II)/Fe(III) ratios, and particle sizes[26]. Dissolved Fe(II) participates in redox reactions at the interfaces and can donate electrons to O2 or anaerobic bacteria[24,27]. Common Fe (oxyhydr)oxide minerals include Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxides and mixed-valence oxides. Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxides like lepidocrocite, goethite, and ferrihydrite are widespread electron acceptors in the subsurface. They can serve as terminal electron acceptors for Fe(III)-reducing bacteria (FeRB)[28,29], thereby participating in extracellular ET processes[26]. Additionally, sorption on minerals can enhance the reactivity of Fe(II) and promote abiotic contaminant reduction[30]. Magnetite (Fe3O4) is a widely present mixed-valence oxide, which can act as both an electron donor and an acceptor[24,31]. For example, magnetite can alternately serve as an electron source for Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria or as an electron donor for FeRB, depending on environmental conditions such as light and acetate availability[32], or as an electron donor to facilitate the abiotic reduction of carbon tetrachloride and Cr(VI)[33,34].

Fe-bearing clay minerals are also notable for their mixed-valence (Fe(II)/Fe(III)) character and layered structure, allowing them to act as both electron donors and acceptors[24,35]. Structural Fe(II)/Fe(III) in clay minerals can participate in redox reactions with external oxidants or reductants, and enable ET between interlayer and surface Fe sites[24,36,37]. Specifically, structural Fe(III) can be reduced by microbes, edge surface Fe(II), or chemical reductants (e.g., dithionite), thereby generating reactive Fe(II) that can subsequently reduce organic and inorganic contaminants[38−41]. As a result, the structural Fe in clay minerals can sustainably accept, store, and donate electrons. Fe-bearing clay minerals also exhibit a wide Eh range (from −0.6 to +0.6 V vs. SHE)[42], enabling them to mediate the cycling of elements such as C, O, N, Fe, and S, and to drive the transformation of contaminants along redox gradients in the subsurface[36]. Therefore, both magnetite and Fe-bearing clay minerals can be referred to as "geobatteries", a term describing redox-active species that act as electron reservoirs, capable of reversibly donating, accepting, and storing electrons[43]. These properties make them important mediators of ET in subsurface redox processes.

Other Fe(II)-bearing minerals such as green rust and Fe sulfides also act as important electron donors, facilitating the abiotic reduction of contaminants like nitrate and hexavalent chromium[44,45].

Natural organic matter

-

NOM represents another major class of redox-active species in the subsurface. Traditionally, the components of NOM have been referred to as humic substances, including humic and fulvic acids[46]. The redox activity of NOM mainly derives from quinone/hydroquinone groups, which serve as important electron-accepting and electron-donating moieties and exhibit a wide range of Eh values under pH-neutral conditions (−0.3 to +0.15 V vs. SHE)[47−50]. The ET efficiency of NOM can be influenced by the molecular structure quinone/hydroquinone groups, including the density of redox-active sites, the number of aromatic rings, and the features of substituent groups. For example, quinone-bearing sulfonic acid groups and extended aromatic systems exhibit a significantly higher surface adsorption capacity and ET reversibility than simple benzoquinones. The high ET efficiency of these molecules is attributed to synergistic interactions between quinone moieties and surface oxygenated functional groups (e.g., C=O)[51]. Furthermore, structural features such as multiring aromaticity and cooperative functional groups like sulfonic acid adjacent to the hydroxyl groups create more active interaction points with mineral surfaces, enhancing interfacial ET[51].

These properties enable NOM to participate in diverse redox reactions involving both microbes and pollutants, and to facilitate microbially driven biogeochemical reactions[50]. Specifically, oxidized NOM can accept electrons from microbial respiration and subsequently transfer them to Fe(III)-bearing minerals[52−54]. They can also mediate abiotic ET from chemical reductants such as sulfide to pollutants like halogenated hydrocarbons and nitroaromatic compounds[55−57]. In contrast, reduced NOM may serve as an electron donor for anaerobic/aerobic respiration or react directly with O2[55,58,59].

In addition, some microbes can secrete soluble organic metabolites that further enhance ET. For instance, Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 releases riboflavin, which acts as an extracellular electron shuttle. The electron shuttle is a type of ET mediator composed of redox-active organic molecules that can be reversibly oxidized and reduced[60]. These organic molecules diffuse toward Fe(III) minerals and mediate ET for microbial Fe(III) reduction[61,62]. Similar to mixed-valence Fe-bearing minerals, NOM like humic substances can reversibly accept, store, and release electrons, acting as another type of geobattery in the subsurface.

Microbes

-

Beyond Fe-bearing species and NOM, microbes are indispensable redox-active components in the subsurface. Through metabolic processes, microbes exchange electrons with extracellular minerals and NOM, participating in redox reactions as either electron donors or acceptors. This extracellular ET is mainly achieved by membrane-associated structures[13]. For example, Gram-negative dissimilatory FeRB such as Shewanella and Geobacter have outer membranes and periplasmic spaces that host multiheme c-type cytochromes, facilitating ET from the inner membrane to external electron acceptors such as Fe(III)-bearing minerals[13,63]. More details about extracellular ET processes and pathways are described in Sections Short-distance electron transfer in microbe-associated interface and Extracellular electron electron transfer beyond direct interfacial contact.

-

Redox interfaces are widely recognized as key zones where ET occurs in the subsurface. These interfaces exist primarily through the contact between oxidants and reductants and the limited penetration of O2, which establishes spatial redox gradients with depth. The redox gradient delineates a sequence of redox zones, each supporting distinct ET processes[2]. In addition to the vertical distribution of oxidants and reductants, the inherent spatial heterogeneity of the subsurface can also contribute to the formation of redox interfaces. These redox interfaces are critical for controlling the mobility and transformation of redox-active species, and thus influence ET pathways in the subsurface.

Redox interfaces along a reduction potential gradient in the subsurface

-

In the subsurface, sequential redox zonation arises from a combination of biotic and abiotic redox reactions, which establish spatial gradients in reduction potential. The reduction potential gradient reflects the stepwise consumption of electron acceptors according to their thermodynamic favorability, starting with O2 and nitrate in the oxic near-surface, followed by manganese(IV), Fe(III), sulfate, and finally carbon dioxide in deeper anoxic zones[2,9,26]. The transitions between these redox zones, as well as the interfaces involved in individual redox zones where redox-active species coexist, constitute reactive redox interfaces (Fig. 2a). Along the reduction potential gradient, redox interfaces are formed between different redox couples or phases like mineral–solution[10], microbe–solution[12], and microbe–mineral[13] interfaces. These interfacial zones typically range from nano- to microscale, and they serve as biogeochemical hotspots that mediate rapid and localized ET processes. This makes them important for controlling the chemical speciation and bioavailability of elements (e.g., Fe, S, C, and N), and the toxicity and mobility of many redox-sensitive contaminants (e.g., As, U, and Cr) in the subsurface[2,26].

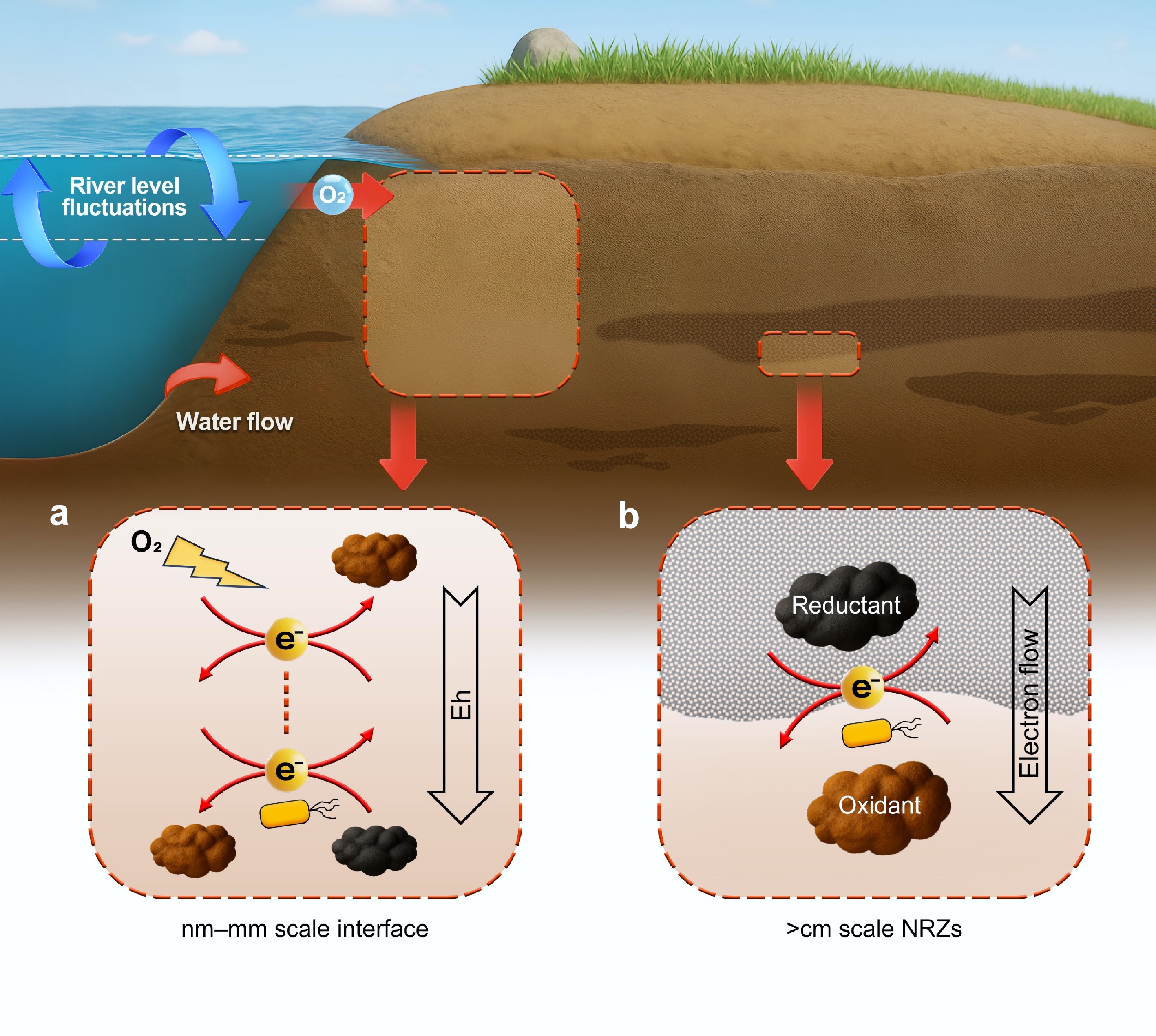

Figure 2.

Different types of redox interfaces in the subsurface. Part (a) conceptualizes the redox interfaces along reduction potential gradient and those induced by oxidant disturbances in the subsurface. Part (b) presents the redox interfaces formed as a result of the structural heterogeneity of the subsurface, especially in naturally reduced zones (NRZs). The yellow electron icons represent the positions of redox interfaces.

Redox interfaces induced by oxidant disturbances in the subsurface

-

Oxidant disturbances in the subsurface primarily originate from natural processes and anthropogenic activities. For example, groundwater level fluctuations can be caused by surface water–groundwater interactions, wet–dry cycles in ecosystems such as wetlands and estuaries, and the infiltration from precipitation into the subsurface[64−66]. These processes can introduce oxidants into the subsurface and induce the formation of redox interfaces across various spatial scales such as dynamic interfaces in riparian areas[67,68] and the sediment–water interface in floodplain environments[9] (Fig. 2a).

A typical mode of natural disturbances is the surface water–groundwater interaction, which involves alternating recharge between the oxygen-rich surface water and anoxic groundwater during low- and high-flow periods. The shifts in redox condition elevate the Eh value of the aquifer, leading to the formation of redox transition interfaces[8,67]. In plain regions like floodplains and wetlands, vertical changes in the groundwater level driven by wet–dry cycles can introduce oxidants (e.g., O2 and nitrate) from the unsaturated zone into the reducing subsurface, generating localized redox interfaces[9,69]. Rainfall events can also carry nitrates and other potential electron acceptors into the reducing subsurface, further establishing redox gradients[70]. Other mechanisms of external oxidant disturbances include O2 transfer between the surface and the subsurface. For example, plant roots can facilitate gas exchange with the atmosphere, allowing the penetration of O2 into the rhizosphere[71,72], while capillary fringes in porous aquifers can promote O2 transport into the subsurface[73]. These processes all contribute to the formation of redox interfaces by introducing oxidants into the reducing subsurface.

Anthropogenic disturbances also alter groundwater levels or directly introduce oxidants into the subsurface, including hydrological engineering, groundwater extraction, and in situ remediation activities. Hydrological engineering involving cycles of water storage and release can cause substantial groundwater level fluctuations[74]. Excessive groundwater pumping promotes the infiltration of oxic surface water into anoxic subsurface zones[75]. In situ chemical oxidation injects oxidants (e.g., hydrogen peroxide and persulfate) directly into the polluted subsurface[76,77].

Redox interfaces formed due to the structural heterogeneity of the subsurface

-

The physical and biogeochemical heterogeneity of the subsurface results in spatial differences in permeability, which can further lead to the development of redox interfaces between low- and high-permeability zones (Fig. 2b)[4,78,79]. Campbell et al. first reported that in the Upper Colorado River Basin, fine-grained clay-rich sediments exhibited strong sulfate-reducing conditions in the absence of anthropogenic activities[80]. These reducing zones, referred to as naturally reduced zones (NRZs), are typically surrounded by oxidized sediments and soils, thereby forming distinct redox interfaces[80]. Since 2016, the research group led by Fendorf has systematically investigated the structure and redox properties of NRZs, revealing that NRZs may occur as either low-permeability layers or blocky lenses surrounded by high-permeability sediments such as sands[79,81−84]. These fine-textured NRZs impede O2 diffusion, while the surrounding coarse-textured zones allow for more effective O2 penetration. This physical heterogeneity creates steep redox gradients across NRZs' boundaries[79,82].

Furthermore, NRZs often contain abundant NOM, reduced Fe and S species, and active microbial communities, which rapidly consume O2 and reinforce the reducing conditions[79,82−84]. NRZs are regarded as significant electron reservoirs in the subsurface because of their biogeochemical heterogeneity. The Eh differences between NRZs and the adjacent oxidized zones create a thermodynamic driver for electron flux, potentially leading to redox reactions in the surrounding environment. Studies have shown that microbes within NRZs can utilize organic carbon to drive sulfate reduction and release reduced S species, which subsequently promote the reductive immobilization of metal contaminants such as U, As, and Ni near the NRZs' boundaries[79,82,85]. The size and shape of NRZs can vary significantly, with the spatial scale of NRZs' boundaries and redox interfaces ranging from decimeters to meters[79]. Despite these findings, the mechanisms governing electron release and ET from NRZs, as well as their influence on the transport and transformation of contaminants, remain poorly understood. It is worth noting that recent studies have shown that redox interfaces are not confined to the boundaries of NRZs but can shift spatially in response to groundwater flow. Reduced species within NRZs can be transported into the surrounding high-permeability zones, where they also participate in redox reactions and influence geochemical processes outside the NRZs[82−84,86,87].

These findings suggest that dynamic redox interfaces exist between low- and high-permeability zones in the subsurface as a result of structural heterogeneity (Fig. 2b). However, the pathways and mechanisms of ET across these interfaces remain inadequately understood. Advancing this understanding is essential for accurately predicting solute transport, assessing contaminant transformation, and developing more effective strategies for groundwater remediation.

-

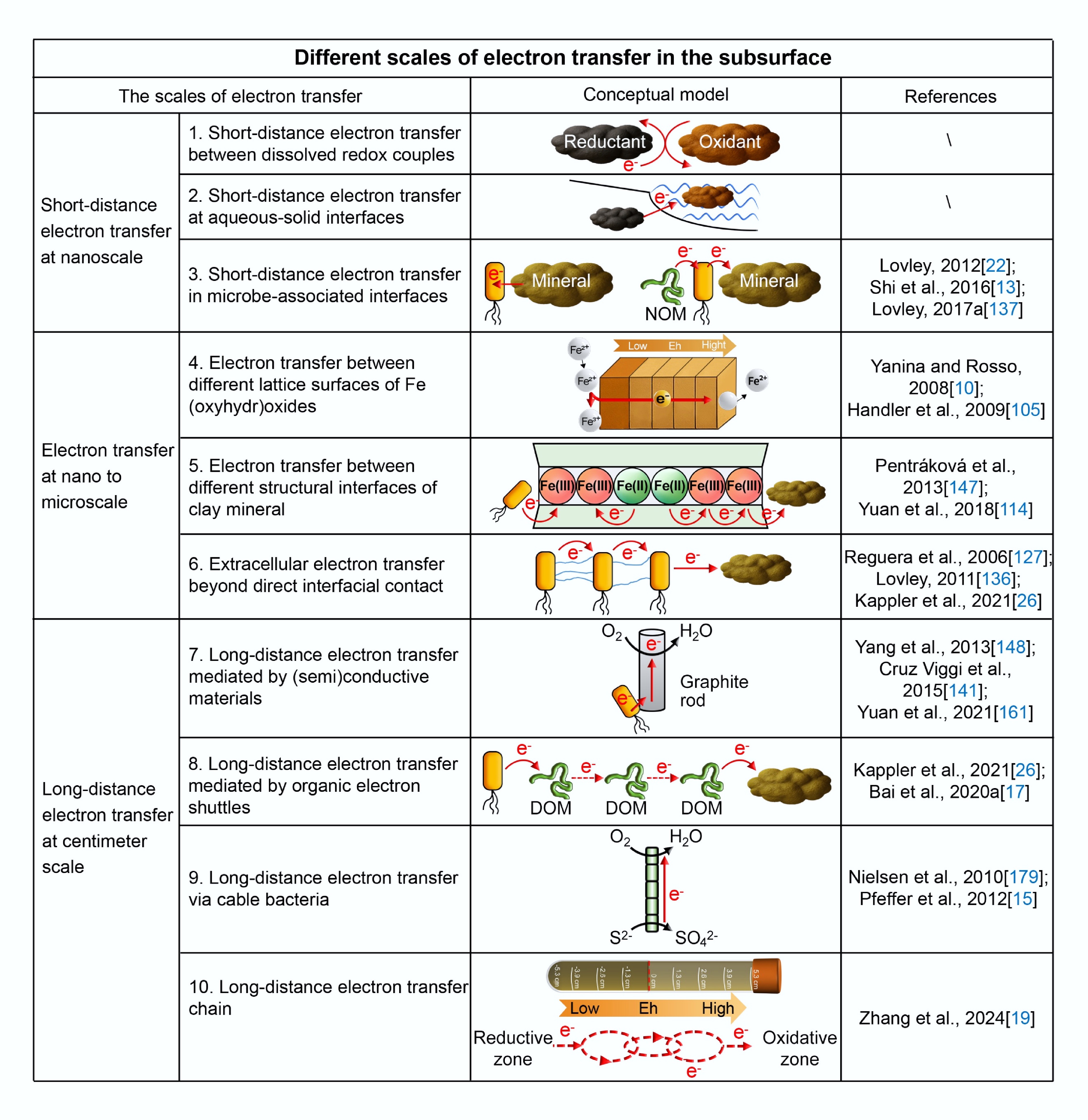

Previous studies on ET at redox interfaces in the subsurface have mostly focused on short-distance processes from the nano- to the microscale. These findings have primarily addressed ET between dissolved redox couples in aqueous solutions[59,67,88−90], at aqueous–solid interfaces[91−94], and in microbe-associated interfaces[13,25,26,95,96]. These interfacial ET processes normally present as electron exchange occurring across molecular distances, which are defined as short-distance ET at the nanoscale in this review. These short-distance ET processes and their underlying mechanisms provide critical theoretical foundations for understanding how electrons are released and transferred in the subsurface.

Short-distance electron transfer between dissolved redox couples

-

Subsurface environments are rich in redox-active species, including both oxidants and reductants, which together form diverse redox couples. The common redox couples in the dissolved phase include Fe(II)/Fe(III) and reduced/oxidized NOM[67,89,97]. At redox interfaces, connected redox couples facilitate ET at the molecular scale (Fig. 3). For example, oxygenation of dissolved Fe2+ and reduced dissolved organic matter (DOM) occur at the oxic–anoxic interface in soil porewater[88,90]. Redox reactions between dissolved redox couples represent a typical form of short-distance and molecule-to-molecule ET, which occurs across nanometer-scale redox interfaces in the subsurface.

Short-distance electron transfer at aqueous–solid interfaces

-

Short-distance ET at aqueous–solid interfaces primarily involves redox interactions between minerals and dissolved species (Fig. 3): (1) Fe(II)-bearing minerals and dissolved oxidants, (2) Fe(III)-bearing minerals and dissolved reductants, and (3) Fe-bearing minerals and dissolved NOM. Surface-sorbed Fe(II) can release electrons to molecular O2, promoting the oxidative transformation of adsorbed Fe(II) into Fe(III), which often leads to the formation of secondary Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxides[24,30,98]. Fe(II)-bearing minerals can be oxidized by high-valence metals such as U(VI), Cr(VI), or Tc(VII), which act as terminal electron acceptors at the aqueous–solid interface[99−101]. These redox reactions support the immobilization of toxic metals via reductive precipitation, in which the metals are reduced under reducing conditions and subsequently precipitate as solid phases such as UO2 or Cr2O3 in contaminated subsurface environments. At the interfaces between Fe(III)-bearing minerals and dissolved reductants such as Fe2+, the Eh difference between structural Fe(III) and dissolved Fe2+ can drive electron exchange[102−105]. This interfacial ET process is not a one-time event; instead, it often triggers a series of ET processes within the mineral structure such as surface adsorption and lattice/layer conduction.

As for the redox processes at the interfaces between Fe-bearing minerals and dissolved NOM, the quinone/hydroquinone groups of NOM participate in ET with Fe-bearing minerals. Hydroquinone moieties in humic substances can release electrons to poorly crystalline ferrihydrite[52,106], while reduced humic substances can release electrons to goethite and hematite[52]. Several types of NOM, such as humic acids[107], hydroquinone[108], and soluble lignin[109] , have been reported to release electrons to structural Fe(III) in Fe-bearing clay minerals. In addition, reduced anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate (AQDS)[110], a synthetic quinone-bearing organic compound, exhibits similar redox behavior.

Short-distance electron transfer in microbe-associated interfaces

-

In addition to abiotically driven short-distance ET, microbially driven ET represents another important short-distance ET process in the subsurface. These ET processes, known as microbial extracellular ET, occur at the interfaces between microbial cells and extracellular electron acceptors/donors such as redox-active minerals and NOM (Fig. 3). Taking microbe–mineral interfaces as an example, extracellular ET is generally facilitated by a network of redox-active proteins that can mediate ET from the cytoplasmic membrane to extracellular electron acceptors/donors[13]. During the intracellular oxidation of organic substrates, electrons are released and initially transferred via the quinone pool in the cytoplasmic membrane. These electrons are then transferred to various intracellular iron-containing c-type cytochromes. Subsequently, multiple functional proteins located in the periplasm transfer the electrons to various metal-reducing enzymes in the outer membrane and finally to extracellular Fe(III)[13,111,112].

-

In addition to the short-distance ET at single redox interfaces, there are more ET processes through multiple interfaces, which range from the nano- to the microscale in the subsurface. These ET processes are not limited to a single interface; instead they occur across multiple structural boundaries, such as different lattice surfaces of minerals[10,105,113], different structural interfaces of minerals[36,114,115], or extracellular structures of microbial cells[26,116]. Such ET is commonly facilitated through stepwise redox reactions involving multiple redox-active sites, thereby extending the localized interfacial ET beyond microsites.

Electron transfer between different lattice surfaces of Fe (hydr)oxides

-

Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxides are widely distributed redox-active minerals in the subsurface and are well known for their semiconducting properties[24,117]. These minerals consist of interconnected crystal lattices that form conductive bands capable of mediating internal ET processes. Electrons released from surface redox reactions can be transferred into the bulk lattice structure, facilitating multi-interface ET within a single mineral particle (Fig. 3). Taking goethite (α-FeOOH) as an example[105], the first step involves the adsorption of dissolved Fe2+ on the surface of minerals; then the adsorbed Fe(II) on the (001) basal plane releases electrons to the structural Fe(III) on the same or adjacent crystal surfaces, caused by the difference in Eh at the dynamically formed mineral–solution interface. This cycle leads to the continuous exposure of fresh Fe(III) at newly generated reactive interfaces, thereby initiating further ET processes[105]. In poorly crystalline Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxides such as ferrihydrite, ET across different lattice surfaces facilitates the reduction of structural Fe(III), thereby promoting the transformation of Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxides into more crystalline phases such as goethite and hematite[118].

Generally, the redox reactivity of Fe-bearing minerals is closely related to their crystallinity and surface reactivity. For example, Fe(II) adsorbed onto less crystalline Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxides like ferrihydrite and lepidocrocite has been shown to be more redox-reactive than that on more crystalline phases such as goethite and hematite[24]. The difference in reactivity can be explained by the redox potential values of Fe2+−Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxide couples, which have been calculated to be 0.768 V for goethite, 0.769 V for hematite, 0.846 V for lepidocrocite, and 0.937 V for ferrihydrite[119,120]. These Eh values reflect the thermodynamic driving force that governs interfacial ET between sorbed Fe(II) and Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxides. Since these redox interfaces are located within the mineral’s lattice framework, the associated ET distances typically range across the crystal scale, which is from the nanometer to micrometer scale[10,103,118,121].

Electron transfer between different structural interfaces of clay minerals

-

Clay minerals in the subsurface contain multiple structural interfaces, where ET can occur across the layered structure (Fig. 3). Taking Fe(III)-bearing clay minerals as an example, the first step involves the adsorption of dissolved Fe2+ on the minerals' surface, which determines the subsequent ET pathway. At pH > 7, dissolved Fe2+ can be sorbed on edge sites by forming inner-sphere complexes, or bind directly to the edge surface[122,123]. Subsequently, ET can proceed from the sorbed Fe(II) to structural Fe(III) via Fe(II)-O-Fe(III) linkages along the octahedral sheet, which is referred to as an interior ET process[123−125]. At pH < 6, dissolved Fe2+ preferentially adsorbs onto the basal surface of the tetrahedral sheet via cation exchange, from which electrons are transferred to structural Fe(III) within the octahedral layer[122,125].

In the case of Fe(II)-bearing clay minerals, ET can proceed in the opposite direction, from the internal structure to its surface. When exposed to external oxidants (e.g., O2), edge Fe(II) has a higher reactivity and is preferentially oxidized to Fe(III), creating an Eh gradient that increases from the interior to the edge[114,115]. This Eh gradient drives ET from structural Fe(II) to edge Fe(III) through Fe(II)-O-Fe(III) linkages, leading to the reduction of edge Fe(III) and the continuous regeneration of surface-reactive Fe(II).

Whether electrons are transferred inward into or outward from the clay mineral structure, the fundamental unit of ET is the Fe(II)-O-Fe(III) linkage, across which electron hopping occurs over a distance of approximately 0.3 nm[124]. When considering the total distance between structural Fe sites and the reactive surface, the effective ET distance across different structural interfaces of clay minerals can reach up to the micrometer scale (less than 0.5 μm)[104].

Extracellular electron transfer beyond direct interfacial contact

-

Microbes can exchange electrons with extracellular minerals at the cell–mineral interface. However, microbes also employ several alternative strategies to achieve extracellular ET beyond interfacial contact. For example, Fe(III)-reducing bacteria can use conductive nanowires formed by extensions of the outer membrane and pili, which can transfer electrons over micrometer-scale distances[126−129] (Fig. 3). These structures can form physical connections between microbes and solid-phase electron acceptors or even bridge the surrounding cells[130,131]. In addition, microbes can employ redox-active cofactors embedded in biofilms, secrete soluble and solid-phase electron conductors (e.g., riboflavin), or utilize organic ligands to mediate indirect ET[111,131,132]. Through these pathways, electrons can be transferred to high-valence minerals [e.g., Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxides], which can further serve as ET mediators to facilitate ET to other terminal electron acceptors such as heavy metals or nitrate[9,133,134]. The distance of these extracellular ET commonly ranges from the nano- to the microscale[26].

Extracellular ET also includes interspecies ET, which is commonly observed between syntrophic microbial communities in the subsurface. During interspecies ET processes, electrons are transferred from one microbial species to another, enabling cooperative energy metabolism[135,136]. Interspecies ET can occur either through direct cell-to-cell contact or via ET mediators[25,26,137]. In microbial aggregates, the distance for interspecies ET is primarily determined by the size of the aggregates and typically ranges from the nano- to the microscale[138].

-

Interfacial and short-distance ET processes are generally nondirectional and restricted to microsites, ranging from the nano- to the microscale. However, the subsurface is a structurally complex and spatially heterogeneous system, extending across various depths and containing diverse structural features. These natural characteristics raise important questions. Can the redox-active species that are dispersed throughout the subsurface be linked via extended ET processes? Does long-distance ET connecting spatially isolated microscale redox reactions exist? These questions are particularly important for subsurface remediation when electron donors or acceptors are limited at the reaction site. These challenges indicated the potential importance of long-distance ET for overcoming spatial separation between redox-active species and biogeochemical processes.

In this review, ET at the centimeter scale is defined as both long-distance ET and long-distance ET chains. Long-distance ET refers to directional ET processes mediated by (semi)conductive materials, organic electron shuttles, or cable bacteria, with effective ET distances typically spanning from several millimeters up to a few centimeters[14−17]. In contrast, a long-distance ET chain is conceptualized as an ET pathway composed of serially connected short-distance ET units, which may include both nanoscale interfacial ET and spatially extended nano- to microscale ET across mineral or microbial structures[19]. Through successive redox interactions, these short-distance ET units can be linked into extended directional chains at distances of tens of centimeters or even up to the meter scale. Despite differences in their mechanisms, we categorize both long-distance ET and long-distance ET chains as centimeter-scale ET due to their comparable spatial extent and common role in coupling spatially isolated redox processes in the subsurface.

Long-distance electron transfer mediated by (semi)conductive materials

-

The phenomenon of long-distance ET mediated by (semi)conductive materials in the subsurface was first observed by Sato and Mooney[139], who observed natural electric potential differences and electric fields at varying depths in subsurface rocks. They hypothesized that these electric fields were generated by spatially separated redox reactions, where the oxidation of reductants in deeper anoxic zones and the reduction of O2 near the surface were connected by conductive Fe-bearing minerals. With the presence of Fe-bearing minerals as semiconductors, this process was later conceptualized as the "geobattery" pathway[139,140]. Since then, the concept of long-distance ET via (semi)conductive materials has been widely applied in bio-electrochemical remediation technologies. For example, microbial electrochemical snorkel (MES) systems utilize conductive carbon or metal materials (e.g., graphite or iron) fabricated into rod- or plate-shaped electrodes[141−143]. These snorkels typically range from a few centimeters to several tens of centimeters in length, and are embedded into anoxic sediments, where the snorkels capture electrons released by microbial metabolism. The snorkel provides a preferential pathway for long-distance ET, leading to an electron flow and acceptance by terminal electron acceptors such as O2 or nitrate at the oxidizing end[141−144] (Fig. 3).

The mechanisms of long-distance ET through (semi)conductive materials, such as pyrite (FeS2), involve the generation of electron–hole pairs when valence electrons from Fe and S atoms are excited to the conduction band[14]. The difference between the rate of electron movement and the rate of recombination (i.e., the recombination of electrons and holes) determines the ET's efficiency. A higher conductivity enhances the distance of ET[145]. So far, long-distance ET mediated by (semi)conductive materials has been demonstrated in the bioremediation of hydrocarbon-contaminated aquifers and the removal of nitrates from surface waters, highlighting its important environmental implications[141−144,146].

Long-distance electron transfer mediated by organic electron shuttles

-

The redox-active quinone/hydroquinone moieties allow NOM to act as an electron shuttle to expand ET beyond individual redox interfaces[17,149,150] (Fig. 3). A widely used model organic electron shuttle is AQDS, while other known electron shuttles include microbially secreted flavins, humic substances, biochar particles, and particulate organic matter[18,20,151−153]. As previous studies about the ET shuttling effect of NOM were performed in well-dispersed systems, it is intriguing whether ET can occur across a longer distance between spatially separated bacteria and Fe(III) minerals by redox cycling between reduced and oxidized NOM. In a series of recent work by Kappler's research group[16−18], Fe(III)-reducing bacteria and ferrihydrite were separated by a 2-cm agar-solidified matrix in which AQDS or NOM was contained. They found that ferrihydrite can be reduced by the electrons from Fe(III)-reducing bacteria at a 2-cm distance, and proposed that electron hopping between reduced and oxidized AQDS or NOM was mainly responsible for the long-distance ET. In very recent studies by Chu's research group[154−156], long-distance ET mediated by quinones was directly visualized. Photothermal imaging showed that AQDS can facilitate ET across 1.7 to 9.6 mm[154]. Quinones also shuttled electrons to oxygen, generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) (e.g., H2O2, •OH) centimeters away[155,156]. The ET distance and ROS production efficiency depended on the redox potential of quinone[155,156]. A diffusion-electron hopping model was proposed as the mechanism of the abovementioned long-distance ET. These studies illustrate that organic electron shuttles can mediate long-distance ET at around the centimeter scale, highlighting the ability of electron shuttles to bridge spatially separated electron donors and electron acceptors in the subsurface.

Long-distance electron transfer via cable bacteria

-

Cable bacteria are unique filamentous microorganisms recognized for their ability to mediate long-distance ET in sediments. The bacteria were first discovered to shuttle centimeter-scale ET in marine sediments from the deep sulfide-rich zone to the overlying oxic water. These filamentous microorganisms can grow to several centimeters in length and consist of a continuous chain of cells encased by highly conductive periplasmic fibers. These fibers contain electrically conductive protein structures, such as cytochromes, that facilitate long-distance ET along the entire filament[15,157]. When one end of a cable bacterium is located in the anoxic zone of sediment, it accepts the electrons released from electron donors such as hydrogen sulfide or iron sulfide. The electrons are then internally transported through the periplasmic network over centimeter-scale distances to the opposite end of the filament, which is in contact with the overlying water. The terminal electron acceptors such as dissolved oxygen or nitrate in the overlying water accept the electrons to finish this long-distance ET process[15,158,159] (Fig. 3). The filament length plays an important role in determining the efficiency and distance of long-distance ET[146,158,159]. These multicellular filaments act as biological conductors, extending over millimeters to centimeters[159,160]. Thus, this biologically mediated ET process typically ranges from 0.4 to 5 cm, with an average effective range of 1–2 cm[160]. However, increased filament lengths can reduce ET efficiency through enhanced internal resistance and decreased stability, making the filaments more susceptible to breakage under environmental disturbances[159]. So far, this type of microbial centimeter-scale ET has been observed in various sediment–water interfaces, including reduced sediments from marine, lacustrine, fluvial, and wetland systems[138,159,162−164].

Compared with (semi)conductive materials such as pyrite or graphite, which can mediate ET to longer distances —sometimes to several tens of centimeters—cable bacteria are generally limited by their biological constraints. The physical length of the conductive filaments of cable bacteria is constrained by cellular division and metabolic needs[161], thereby confining their effective ET range. This gap in ET distance highlights the need to consider not only individual mechanisms but also integrated or chain-like pathways to achieve long-distance ET.

Long-distance electron transfer chain

-

While previous studies have established various mechanisms of long-distance ET in the subsurface, these pathways only occur in the presence of (semi)conductive materials, organic shuttles, or cable bacteria. Moreover, the natural subsurface features directional Eh decreasing from the surface for the reduction of O2 (or nitrate) to different depths below the surface for reduction of Fe(III) (or other oxidants)[2,26], reaching distances of centimeters to meters or even longer. It is also elusive how such large-scale Eh gradients are sustained by microscale ET processes. A recent study proposed that an even longer distance of ET than previously discovered could be achieved through a directional series of short-distance ET chains, which functioned to connect reduced zones with oxidized zones along the reduction potential gradient[19]. By using variation in electron-donating capacity (EDC) as a proxy for ET, the ET distance was claimed to be able to extend to 10 cm along the redox gradient in sediment columns. The reduction potential gradient was the driving force along with physical contact between reducers and oxidizers through, for example redox-active substances and microorganisms, microbial activity, and solute diffusion, which are all favorable conditions for the occurrence and maintenance of long-distance ET[19] (Fig. 3).

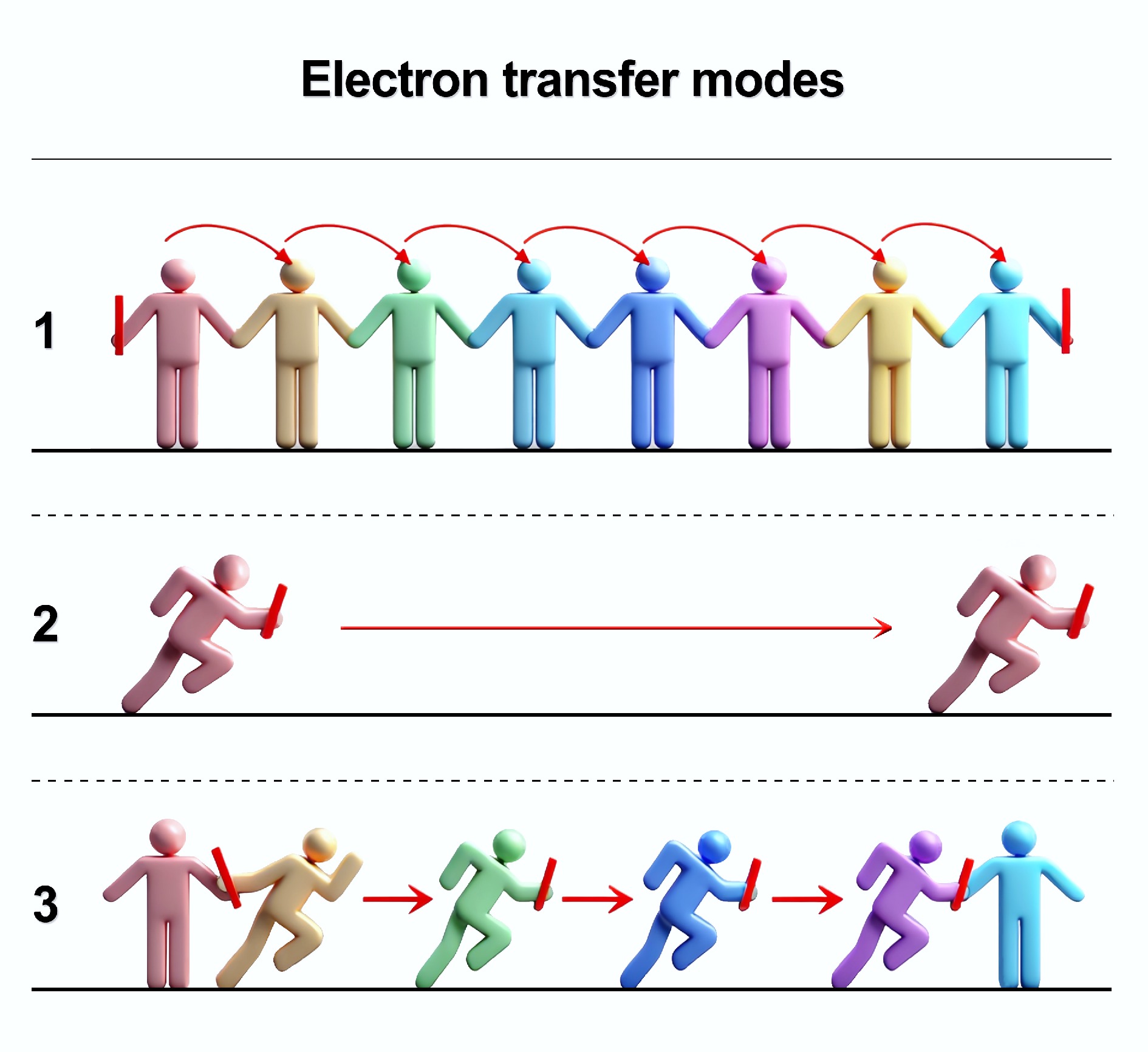

To better conceptualize how directional long-distance ET occurs in the subsurface, three modes were proposed (Fig. 4)[19]. Mode 1: electrons are transferred "hand by hand" by the ET mediators. This type of directional long-distance ET chain may predominate in low-permeability matrices (e.g., clay-rich sediments), where redox-active substances are abundant, and advection and diffusion are limited. This mode can be termed "hand-by-hand". Mode 2: electrons are carried and transferred by the redox-active species. This is the conventional mass transfer mode, which may predominate in high-permeability matrices (e.g., sandy habitats), where ET mediators are sparse and advection/diffusion is strong. Mode 3: electrons are transferred by a relay-like process. Both directional long-distance ET and mass transfer occur synergistically, which may predominate in moderately permeable matrices, where electron hopping and mass transfer are interconnected to form a relay transmission mode. This conceptual model provides a new framework for understanding how redox-active processes can couple spatially separated reduced and oxidized zones in the subsurface, integrating and extending traditional perspectives focused on interfacial ET, short-distance ET, and long-distance ET mediated by specific substances or microbes.

Figure 4.

Conceptualized modes for long-distance electron transfer chain. Mode 1: "hand-by-hand" mode; Mode 2: conventional mass transfer mode; Mode 3: "Relay-like" mode.

Although the term "long-distance ET chain" has only recently been used in the context of sediment systems, similar mechanisms have been proposed at the microstructural level. For example, Giese et al. summarized long-distance ET pathways primarily in cellular and biomolecular systems (up to ~100 μm), highlighting electron hopping and nanowire-mediated ET through cytochrome-rich networks[165]. While their focus was not on centimeter- to meter-scale ET, their conceptual framework on stepwise ET chains is analogous to the directional long-distance ET chains observed in subsurface environments.

The conceptual framework of the long-distance ET chain provides a new perspective for understanding how redox-active processes can couple spatially separated reduced and oxidized zones in the subsurface, integrating and extending traditional perspectives focused on interfacial ET, short-distance ET, and long-distance ET mediated by specific substances or microbes.

-

Redox reactions are fundamental drivers of biogeochemical processes in the subsurface, shaping the cycling of elements and governing the transformation, mobility, and persistence of contaminants. As the core mechanism of redox reactions, ET occurs across spatial scales from nanometers to centimeters or even longer, depending on the properties and distribution of redox-active species, the physical structure of the subsurface, and perturbation conditions. In addition to these spatial and structural factors, environmental conditions such as pH, temperature, moisture content, and the presence of organic matter also influence the occurrence and extent of ET. These factors affect the speciation and reactivity of reductants, oxidants, and mediators. For example, pH and temperature influence the activity of soil microbial communities and the redox properties of minerals[24,166,167]. Moisture content controls the diffusion of redox-active solutes. Therefore, understanding the environmental significance of ET requires a comprehensive evaluation of its effects at multiple spatial scales and under various environmental conditions. At the interfacial and short-distance scale (nano- to microscale), ET governs molecular-level reactions such as mineral dissolution, precipitation, and microbial respiration, which influence the transformation of nutrients and metals. At the centimeter scale, ET bridges spatially separated redox zones through (semi)conductive materials, electron shuttles, or microbial networks, coupling remote oxidation and reduction processes. At the larger scale, such as directional ET chains (centimeter- to meter-scale), ET may connect reducing zones to "remote" oxidizing zones, maintaining long-distance redox gradients over time. Accordingly, these multiscale ET processes shape various geochemical patterns in the subsurface.

Impact on elemental cycling

-

ET is closely related to subsurface elemental cycling, supporting the redox transformation of key elements, such as C, N, S, and Fe[2,168,169]. Interfacial ET processes are fundamental to environmental energy transformation and elemental cycling. In soils and sediments, microbial metabolism can accept electrons from carbon substrates and transfer them to terminal electron acceptors such as O2, nitrate, Fe(III), or sulfate[9,60,63]. For example, Fe(III)-reducing bacteria directly transfer electrons to Fe(III)-bearing minerals at the microbe–mineral interface, inducing reductive dissolution of minerals and oxidizing organic matter (OM), H2, CH4, or ammonium[21,35,60,63]. This coupling of Fe cycling with the turnover of C and greenhouse gas emissions further links interfacial redox processes to global biogeochemical cycles.

At the nano- to microscale, short-distance ET processes involving structural atoms in minerals and redox-active NOM play an important role in driving subsurface biogeochemical cycling[21,24,36]. Structural Fe in Fe-bearing minerals can participate in redox reactions with both biotic and abiotic electron donors or acceptors. Redox-active NOM can facilitate short-distance ET across multiple mineral–NOM and microbe–mineral interfaces by acting as an electron shuttle, conductor, or redox buffer[21,26,170]. These ET processes can induce minerals' transformation and broaden microbial respiration by enabling electron flow into minerals or indirect contact between microbes and substrates. In Fe-bearing clay minerals, ET between structural Fe and external reactants can alter minerals' physicochemical properties, such as cation exchange capacity and surface charge[36,171]. Such ET process may lead to ROS production, promoting the oxidation of NOM and influencing C cycling. As an electron shuttle, redox-active NOM plays a particularly important role in carbon-rich environments such as peatlands and wetlands[53,172,173]. NOM-mediated ET supports syntrophic microbial interactions and mineral-mediated electron shuttling, facilitating the decomposition of complex NOM and the regeneration of terminal electron acceptors such as Fe(III), sulfate, and CO2[21,174,175]. These processes not only enhance C turnover and enable a broader range of microbial Fe cycling, but also help shape redox gradients and regulate biogeochemical dynamics in subsurface ecosystems[26,176]. Therefore, the short-distance ET pathways induced by structural Fe and NOM provide a foundation for larger-scale redox transformations, elemental turnover, and energy flow in the subsurface.

For centimeter-scale long-distance ET, the presence of (semi)conductive materials or cable bacteria has been demonstrated to significantly influence the biogeochemical cycles of S, N, and so on[158,161,177]. (Semi)conductive materials, such as the Fe-bearing minerals of graphite snorkels, extend the distance of ET by creating artificial electron highways[14,150,178]. For example, Wei et al.[143] found that a layered microstructure of green rust and lepidocrocite in sediments enabled long-distance ET to facilitate efficient denitrification. Cable bacteria have been identified as mediating long-distance ET in sediments by coupling sulfide oxidation in anoxic zones with O2 or nitrate reduction in oxic layers[158,159,179]. This electrogenic sulfur oxidation (e-SOx) plays a critical role in shaping S and C cycling. For example, e-SOx stimulates sulfate-reducing bacteria and suppresses methanogenesis, potentially reducing methane emissions in systems like rice paddy soils[180]. Additionally, the metabolic activity of cable bacteria generates an electric field that drives ionic migration, altering the fluxes of key ions such as Ca2+, Fe2+, and Mn2+[181,182].

Apart from the long-distance ET mediated by specific materials and microorganisms, directional long-distance ET chains also have important implications for elemental cycling. The ET flux rate was estimated to be 6.73 µmol e− cm−2·d−1 in column systems[19], which could possibly result in comparable rates of denitrification, Fe(III) reduction, sulfate reduction, and anaerobic methane oxidation. These findings suggest that macroscale long-distance ET can sustain spatially separated redox reactions, thereby expanding the active N, Fe, S, and C cycling.

Influence on pollutants' fate and subsurface remediation

-

Because of their impacts on elemental cycling, ET processes are widely used in the transformation of pollutants and subsurface remediation. The interfacial ET processes can determine the redox state, mobility, and toxicity of contaminants. For example, in situ chemical oxidation for groundwater remediation relies on redox reactions between reactive species (e.g., H2O2 and •OH) and contaminants[183,184]. The efficiency of contaminant degradation is often limited by direct contact between chemical the oxidants and contaminants. The short-distance ET involved in Fe-bearing minerals is another pathway that influences the fate of pollutants. For example, the ET between Fe(II)-bearing clay mineral and Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxide can promote surface-sorbed Fe(II) generation and Cr(VI) reduction[115]. Similar effects occur in the systems with biochar and Fe(III) (hydr)oxides, where ET through C-O-Fe bridges enable surface Cr(VI) reduction[185].

Long-distance ET expands the scale of subsurface remediation. Biochar amendment in paddy soils has been shown to induce the degradation of pentachlorophenol at distances of up to 20 cm from electrodes through the conductive networks of electroactive bacteria like Geobacter[178]. Long-distance ET mediated by cable bacteria was initially considered to be beneficial for removing organic contaminants in sediments, as the reoxidation of sulfide facilitated by cable bacteria could promote sulfate-dependent toluene degradation[162]. Cable bacteria-driven long-distance ET was combined with bio-electrochemical aeration tubes to treat petroleum hydrocarbons in marine sediments[144]. Overall, the applications of special material and microbes mediating long-distance ET have primarily focused on the biodegradation of organic pollutants in soils and marine sediments, and rely heavily on S cycling and the availability of O2[161].

The discovery of directional long-distance ET chains offers a new perspective for subsurface remediation[19]. The physical contact between pollutants and microbial or chemical oxidants is no longer a necessary requirement in the subsurface. Without direct contact, the directional redox gradients can support ET from electron donors to "remote" contaminants. For example, the introduction of strong oxidants (e.g., H2O2) in the shallow subsurface can facilitate long-distance ET chains across sediment matrices. This process enables "remote" remediation, which can be optimized by considering the subsurface's heterogeneity or regulating the content of redox-active species to improve the efficiency of ET. This strategy holds potential for enhancing remediation in zones that are otherwise difficult to access by direct injection or contact-based methods. The findings suggest that manipulating long-distance ET pathways and redox gradients has great potential for enhancing the effectiveness of contaminant remediation in complex subsurface systems.

Contributions in deep time

-

ET processes not only influence the redox dynamics of present-day Earth systems, but also have profound impacts over geological time scales. Interfacial and long-distance ET, particularly those involving minerals and microbes, have played essential roles in driving geochemical transformations that link the biosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere, and lithosphere[186]. A compelling example lies in the formation of banded iron formations (BIFs), which provide crucial geological records of early Earth environments. Microbial Fe(II) oxidation by anoxygenic photoferrotrophs probably contributed significantly to Fe, C, and S cycling[187,188]. In detail, photoferrotrophs oxidize Fe(II) to Fe(III) while fixing CO2, and the resulting Fe(III) is subsequently reduced by Fe(III)-reducing microorganisms. Magnetite, a conductive and abundant component in BIFs, may have facilitated long-distance ET across redox gradients. While direct evidence remains limited, such observations support that long-distance ET may have contributed to BIFs' diagenesis and mineral transformation. Moreover, paleoenvironmental and isotopic evidence from modern hydrothermal microbial mats at the Lucky Strike Vent Field (LSHF) indicate that the reduction of microbial Fe(III) leads to the formation of magnetite networks, and the magnetite networks exhibited similar δ13C and δ56Fe signatures to those found in ~2.5 Ga BIFs[189]. These magnetite-rich microbands are supposed to act as conductive pathways that facilitate ET.

Another similar example could be the widespread sulfide minerals such as pyrite, which can also mediate long-distance ET at different scales in different periods of space and Earth history. These ET process could be of significance in the geological period with redox fluctuations (e.g., the Great Oxidation Event, GOE), as well as on Earth. The redox-active species accompanied by the redox gradient created by these fluctuations potentially sustain long-distance ET and enable electron flow[190,191]. For example, in the Archean and Proterozoic eons when terrestrial life was rare, reactions between reduced species on the land surface [e.g., Fe(II) and S(-II)] and atmospheric O2 could have established long-lasting redox gradients across the land–atmosphere interface[192,193]. The reduced zones below the surface could be a large electron pool, in which electrons can be transferred to the surface for O2 consumption by (semi)conductive minerals or ET mediators, thereby contributing to the delayed rise in O2 content in the atmosphere. Moreover, some ecological models evaluate the relation between microbial ET and atmospheric oxygenation. Olejarz et al. showed that the GOE was initiated when decreased Fe2+ and phosphate inputs shifted the ecological balance from Fe(II)-oxidizing anoxygenic phototrophs to oxygenic cyanobacteria. In this model, microbial ET reactions related to Fe cycling regulated the production and consumption of O2, and thus potentially amplified redox gradients and favored long-distance ET[194].

-

As ET is increasingly recognized to occur across a broad range of spatial scales, from nanometers to meters, future research must address several unresolved challenges to fully understand its environmental impacts and applications. Current limitations include the lack of in situ measurement techniques for long-distance ET, the unclear understanding of biotic–abiotic interactions in ET chains, and insufficient rate constants for developing quantitative models to link ET dynamics to geochemical and ecological outcomes, and so on. Solving these barriers will improve our capacity to describe, predict, and utilize ET processes across diverse and dynamic subsurface environments.

Techniques for electron transfer measurement

-

Quantifying long-distance ET in the subsurface remains technically challenging because of the interference of mass transfer, as well as the lack of measurement techniques. Standardized protocols are currently not available for accurately identifying ET pathways, quantifying electron fluxes, or monitoring ET processes in natural subsurface environments. Recent studies have made progresses in laboratory and field-based techniques for ET dynamics. Various approaches have been developed to analyze ET processes. For the ET processes related to NOM and minerals, mediated electrochemical analysis has emerged as a common method to assess the EDC and electron-accepting capacity (EAC) of NOM and minerals[49,195,196]. The variation in EDC or EAC can be further applied to quantify ET flux[19]. However, the mediated electrochemical analysis is primarily effective in well-mixed systems and still faces limitations in heterogeneous media, where in situ measurement is challenging. Recent studies have introduced innovative in situ techniques. For example, Ma et al. developed a photothermal imaging method that visualizes ET distances from nanoscale zerovalent iron (nZVI) to Ag+ traps embedded in agarose gels[154]. Such methods provide promising pathways to characterize ET behavior in physically complex systems where electrochemical techniques are limited. Wet chemical extraction is a widely used and low-cost approach used to quantify Fe(II)/Fe ratios, which are quantified as an indicator of the extent of ET related to the interfaces of Fe-bearing minerals[18,115,123]. Spectroscopic techniques such as Mössbauer spectroscopy, Fe K-edge X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), and scanning transmission X-ray microscopy (STXM) provide deeper insights into the valence state, coordination environment, and structural distribution of Fe(II)/Fe(III) in Fe-bearing minerals, offering critical information on interior versus surface ET pathways[114,197−199]. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) complements bulk analyses by characterizing the near-surface redox states of Fe in minerals, while density functional theory (DFT) simulations offer atomistic insights into the reaction energetics and electron hopping rates, especially within octahedral Fe(II)–Fe(III) linkages in Fe-bearing minerals[102,115,125]. For microbial systems, fluorescence imaging has been employed to visualize extracellular ET. For example, fluorescent dyes and immunofluorescence were used to localize cytochromes in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 nanowires, revealing a multistep redox hopping mechanism.

For sediments containing cable bacteria, microsensor profiling and electric potential measurements have been widely adopted[162,178,200]. Microsensor measurements of pH, O2, H2S, and Fe help identify the characteristic geochemical fingerprints of long-distance ET such as sharp pH excursions and the formation of electroactive suboxic zones up to several centimeters thick[179,182,201−203]. Electric potential profiling reveals voltage gradients across sediments which can be linked to ionic drift and solute fluxes, thus providing current densities related to ET[181,204]. For long-distance ET processes in sediments without cable bacteria, variations in EDC are applied to quantify ET across different redox zones.

In summary, advancing in situ measurement techniques remains essential for directly and accurately capturing long-distance ET in the subsurface. Particularly for long-distance ET, mass transfer of redox-active species can apparently contribute to variation in EDC. Control experiments have been utilized for subtraction, but direct observation methods to distinguish the ET contributed by redox reactions and mass transfer are currently not available. In addition, it is also difficult to distinguish ET stemming from localized and "remote" redox reactions. It is therefore urgent to develop characterization and measurement techniques for quantifying redox-induced ET processes at different scales.

Insights into biotic–abiotic interactions in electron transfer processes

-

The biotic–abiotic interactions commonly have an important influence on ET processes. For short-distance ET processes, a common synergistic effect occurs through the biogeochemical cycling of iron. For example, in microbial nitrate-dependent Fe(III) oxidation by Acidovorax sp. BoFeN1, Fe(II) is not oxidized directly by the microorganisms but is abiotically oxidized by denitrification intermediates such as NO2− and NO[205]. This process forms a biotic–abiotic ET pathway involved in N and Fe cycling.

For long-distance ET processes, Shewanella oneidensis has been shown to interact synergistically with both DOM and organo-mineral associations (OMAs). As demonstrated by Bai et al., centimeter-scale Fe(III) reduction occurred when Shewanella oneidensis, DOM, and OMAs coexisted[18]. In detail, the electrons released via microbial metabolism were transferred through a redox-cycling network formed by DOM and OMAs. DOM acted as a diffusive electron shuttle, while OMAs served as a redox-active phase to enable electron hopping. Based on the diffusion–electron hopping mechanism[16,17], the apparent ET distance via DOM is shortened through rapid electron exchange, with OMAs acting as redox-active mediators. As a result, the overall ET efficiency between Shewanella oneidensis and Fe(III)-bearing minerals was significantly enhanced.

However, for the recently discovered long-distance ET chains, the respective roles and interactions of biotic and abiotic pathways still remain a fundamental research frontier. The specific roles of microbial communities in forming and sustaining the ET networks remain poorly understood. Variations in microbial diversity, community composition, and metabolic strategies may significantly influence the efficiency, directionality, and stability of long-distance ET. Therefore, future studies need to characterize the structure, function, and spatial organization of microorganisms to evaluate their influence on ET over extended distances. In addition, the quantitative assessment of biotic–abiotic interactions under varying geochemical and hydrological conditions is essential for advancing a mechanistic understanding. Coupling microbiological, geochemical, and transport modeling will be key to figuring out how long-distance ET proceeds across centimeter to meter scales. Such integrative approaches will help clarify the behavior of electron flow in redox-heterogeneous subsurface environments.

Models to quantify electron transfer processes and their associated impact

-

Reactive transport models offer a tool to quantitatively describe ET processes and predict their impact on elemental cycling in the subsurface. However, difficulties exist in model development. First, the reaction networks for different scales of ET process are still not clear, as so many chemical and biological reactions contribute to ET. Second, parameters are lacking for the reactive transport model. One suite of important parameters are the initial conditions, such as the concentrations of electron acceptors/donors and mediators, which are difficult to obtain, as they exist in different phases and species. Another suite of important parameters is the reaction rate constants for all these redox reactions involved in ET processes at different scales, as they occur in different phases and probably interact with each other. Due to these difficulties, it is essential to simplify the modeling processes. An alternative strategy is to use EDC and EAC to represent all the electron donors and acceptors, respectively. Due to the rapid development of big data and machine learning methods in recent years, it is also likely that we will develop data-based models to describe ET processes and their associated impact.

Database for the rates of electron transfer at different scales

-

Quantifying rates of ET across spatial scales is critical for understanding redox-driven processes in the subsurface, yet current data remain fragmented and context-specific. At the microscale, ET within Fe-bearing clay minerals occurs over micrometer distances through electron hopping within the octahedral Fe layers, with the estimated hopping rates enabling electron migration across a 0.5-μm particle in roughly 4 min[104]. At the centimeter scale, microbial Fe(III) reduction can be sustained over 2 cm in agar-solidified systems using the electron shuttle AQDS, and the ET process was driven by a combination of AQDS diffusion and a redox hopping rate of ~108 L·mol−1·s−1 between oxidized and reduced AQDS molecules. An average ET flux rate of 6.73 μmol e− cm−2·d−1 and an ET distance rate of 0.34 cm per day were estimated for directional long-distance ET under a ~700 mV redox potential gradient in sediments.

Despite these advancements, a complete database of ET rates for different redox reactions under diverse environmental conditions is needed. Such a database should include kinetic parameters for both interfacial and long-distance ET across various media (e.g., sediments, soils, aquifers), and under different temperature, pressure, and geochemical gradients. Standardizing measurement protocols and linking rate data with other conditions, such as porosity, organic matter content, and microbial community composition will be useful. Emerging machine learning approaches could further assist in integrating these multivariate datasets and predicting ET rates under complex environmental scenarios, especially in heterogeneous subsurface environments. This could enhance the comparability of studies, support model development, and deepen our understanding of the dynamics of ET processes at different scales.

Engineered electron transfer applications in environmental remediation

-

Engineered applications of ET at different scales offer promising strategies for enhancing contaminant remediation in the subsurface. At the microscale, the structural Fe in Fe-bearing clay minerals plays a role in pollutant transformation, making them ideal candidates for redox-based remediation approaches. In particular, their redox-active surfaces and internal layers can facilitate the reduction of organic pollutants and heavy metals through both direct and indirect ET processes[36]. At larger spatial scales, the long-distance ET mediated by cable bacteria or (semi)conductive materials enables redox reactions between separated zones, which is especially advantageous in low-permeability media, where mass transport is a limiting factor. Thus, cable bacteria or (semi)conductive materials mediating long-distance ET have been shown to overcome the deficiencies of a deficiency of suitable electron acceptors or slow mass transportation at contaminated sites, coupling distant oxidation and reduction reactions for contaminant degradation[161]. Maintaining stable redox gradients can enable directional long-distance ET chains, supporting "remote" contaminant transformation without the need for direct injection of chemicals or microbes into contaminated zones.

However, remediation of low-permeability matrices still remains challenging because of the limited penetration of injected reagents or microorganisms. In such media, an unresolved question is the interaction between mass transfer (e.g., the diffusion of redox-active solutes) and electron hopping. Understanding this interaction is important to evaluate how the sediment's heterogeneity influences the spatial extent and kinetics of ET-based transformations. Moreover, there are still some limitations of the current ET measurement technologies in low-permeability matrices. Most existing techniques, such as solution-phase electrochemical sensors or redox probes, face significant challenges in low-permeability matrices, including signal attenuation, poor spatial resolution, and uncertainty about the directionality of ET. To overcome these limitations, future research should prioritize the development of in situ monitoring techniques that are both spatially precise and compatible with low-permeability media. Addressing these mechanistic and technical gaps is not only essential for a deeper understanding of long-distance ET but also provides a foundation for unlocking its full potential in practical applications.

The above-mentioned ET processes at different scales offer practical relevance in environmental remediation, such as for optimizing biotic–abiotic interaction and developing biosynthetic or geochemical methods to generate in situ conductive media. These innovations can help establish stable redox gradients and sustained electron flow pathways in the subsurface. The unique redox-buffering capacity and spatial persistence of low-permeability matrices, such as clay-rich lenses, make them ideal platforms for long-distance ET-driven contaminant transformation. By leveraging naturally occurring or engineered long-distance ET processes, contaminant degradation could be extended to zones previously considered to be inaccessible. With a deep understanding of long-distance ET mechanisms, their function into field-scale applications will offer new, passive, and energy-efficient solutions for subsurface remediation.

We thank the reviewers whose input greatly improved the manuscript.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: review conception and design, analysis of studies: Zhang Y, Yuan S; research collection: Zhang Y; draft manuscript preparation: Zhang Y, Tong M, Zhang P, Yuan S, Kappler A. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 42025703 and 42277072).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Conceptual framework for electron transfer (ET) in the subsurface, ranging from nano-scale interfacial reactions to centimeter- and meter-scale chains.

Systematic classification of key electron transfer mediators and redox interfaces that govern electron transfer across spatial scales.

Critical review of electron transfer mechanisms at different scales and their roles in biogeochemical cycling and contaminant transformation.

Emphasis on the environmental implications of long-distance electron transfer, particularly in low-permeability or redox-stratified systems.

Outlook on future challenges and opportunities in ET research.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang Y, Tong M, Zhang P, Kappler A, Yuan S. 2025. Different scales of electron transfer processes in the subsurface. Environmental and Biogeochemical Processes 1: e002 doi: 10.48130/ebp-0025-0003

Different scales of electron transfer processes in the subsurface

- Received: 02 July 2025

- Revised: 02 August 2025

- Accepted: 21 August 2025

- Published online: 12 September 2025

Abstract: Electron transfer (ET) processes in the subsurface are fundamental to redox reactions that regulate elemental cycling and contaminant transformation. Due to the structural heterogeneity and the resulting redox heterogeneity in the subsurface, ET occurs across different spatial scales. This review summarizes ET pathways ranging from nanoscale interfacial reactions to centimeter-scale long-distance ET and meter-scale long-distance ET chains. At the nanoscale interface, direct redox interactions between redox-active species drive localized reactions. At the nano- to microscale, short-distance ET involves structural Fe in minerals and microbial extracellular ET. At larger scales (~cm), (semi)conductive minerals, electron shuttles, and microbial networks such as cable bacteria facilitate centimeter-scale ET across physically separated redox zones. These short-distance ET units can be further connected to form directional long-distance ET chains (> cm to even ~m). We highlight the role of long-distance ET in pollutant transformation and its potential for "remote" remediation, particularly in low-permeability subsurface environments. We further outline current advances and future directions in ET research, including measurement techniques, modeling approaches, and rate quantification across scales. Integrating multiscale ET processes into environmental frameworks is critical for improving our understanding of redox dynamics and supporting sustainable subsurface remediation.