-

Iron (Fe) is the fourth most abundant element in the Earth's crust, following oxygen, silicon, and aluminum. Further, Fe (oxyhydr)oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) are the most abundant natural NPs, being ubiquitous in soils, sediments, and natural aquatic systems, where they undergo continual chemical and microbial redox transformations owing to Fe's variable valence [Fe(II)/Fe(III)][1−4]. Owing to their large specific surface areas and high surface ligand densities, IONPs are highly reactive and constitute active biogeochemical agents that contribute substantially to element cycling, pollutant dynamics, and redox buffers[5−9]. Representative IONPs include poorly crystalline ferrihydrite, representing a metastable Fe(III) oxyhydroxide precipitate ubiquitous to soils, and related Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxide transformation products such as lepidocrocite (γ-Fe(III)O(OH)), goethite (α-Fe(III)O(OH)), hematite (α-Fe(III)2O3), and maghemite (γ-Fe(III)2O3), as well as the mixed-valence Fe oxide magnetite (Fe(II)Fe(III)2O4). The presence of both Fe(III) and Fe(II) within or among these minerals underlies their capacity to participate in diverse redox reactions, in contrast to other oxides such as SiO2 and Al2O3.

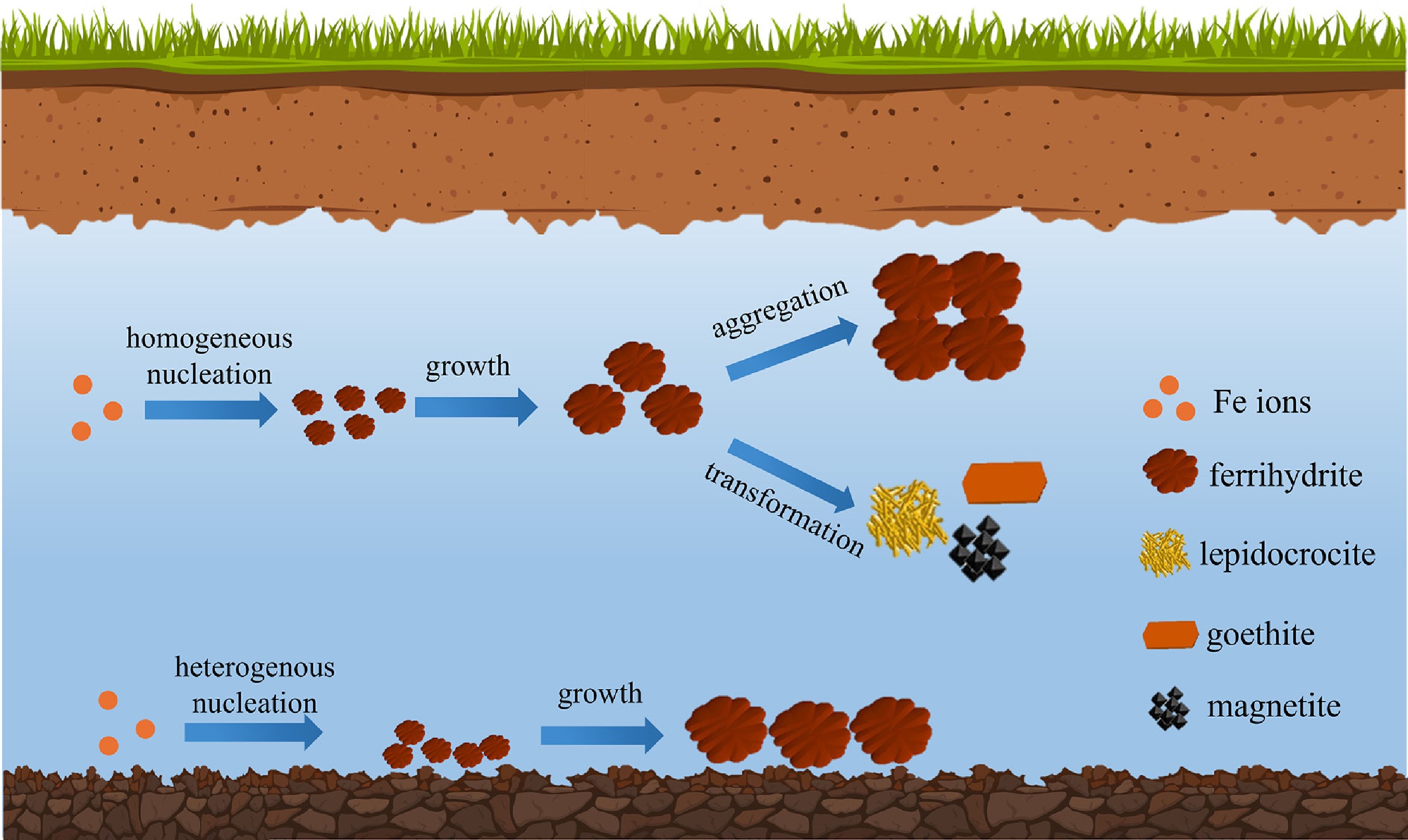

The formation pathways of IONPs are determined in part by biogeochemical conditions, such as the presence of metal ions, organic matter, and microbes. Conversely, the formation of IONPs can, in turn, control the cycling of associated (in)organic species. Thus, a sound mechanistic understanding of IONP formation is essential for predicting the environmental fate of IONPs and associated elements[10−12]. In natural environments, IONP formation is broadly associated with the oxidation of ferrous iron (Fe2+) to ferric iron (Fe3+), followed by Fe3+ hydrolysis (Fe(OH)x3−x) and the polymerization of hydrolyzed ferric species. Once the polymer size is larger than the critical nuclei size, stable nuclei form and subsequently grow through the addition of Fe3+ hydroxide monomers, oligomers, or particles. These processes can occur homogeneously in bulk solution or heterogeneously at solid–liquid interfaces, such as on the surfaces of minerals, organic colloids, or microbial exudates[13]. Most previous studies focused on homogeneous IONPs formation in bulk solution, whilst more recent studies focused on heterogeneous IONPs formation, thereby providing a more complete understanding of IONP formation pathways[14−20]. Environmental chemistry, such as pH, temperature, redox potential, and ionic strength, could affect IONP formation. Further, metal ions, natural organic matter (NOM), and microbes that are ubiquitous in natural aquatic and soil/sediment environments could strongly affect IONP nucleation and growth through controlling the aqueous speciation of Fe-bearing species, saturation states with respect to IONP phases, and Fe coordination environments both in solution and structurally in the solid phase[21]. In turn, these factors can control IONP particle size, crystallinity, and surface characteristics.

Metal cations commonly present in natural waters, such as Al3+, Cr3+, Mn2+, Zn2+, Pb2+, or Cu2+, can strongly interact with IONP surfaces (e.g., through chemisorption or physisorption) or be structurally incorporated into IONP crystal lattices during precipitation processes. In turn, these metal ions can affect IONP nucleation and growth kinetics[22,23]. Further, certain metal ions can inhibit crystallization by disrupting the Fe–O framework, while others can promote structural ordering. Further, metal ions could adsorb onto mineral surfaces present in soils or sediments, altering surface properties and thus controlling heterogeneous IONP formation[24,25].

Organic matter (OM) can also strongly influence IONP formation. Organic ligands rich in carboxyl groups, such as humic or fulvic acids or low-molecular-weight carboxylic acids, can complex with aqueous Fe species, thereby modifying saturation states with respect to IONP phases to control their precipitation. Further, specific NOM ligands can act as capping agents to stabilize nanoparticles during nucleation and growth[13]. As with metal ions, NOM coatings on soil or sediment mineral surfaces could also control heterogeneous IONP formation.

Microbial processes are also intimately involved in the formation of IONPs[26]. Iron-oxidizing bacteria (FeOB), such as Gallionella and Leptothrix, can catalyze Fe2+ oxidation and produce biogenic Fe(III) oxides often embedded within extracellular polymeric substances (EPS)[27]. These biologically formed IONPs exhibit distinct morphologies and surface characteristics compared to their abiotic counterparts[28].

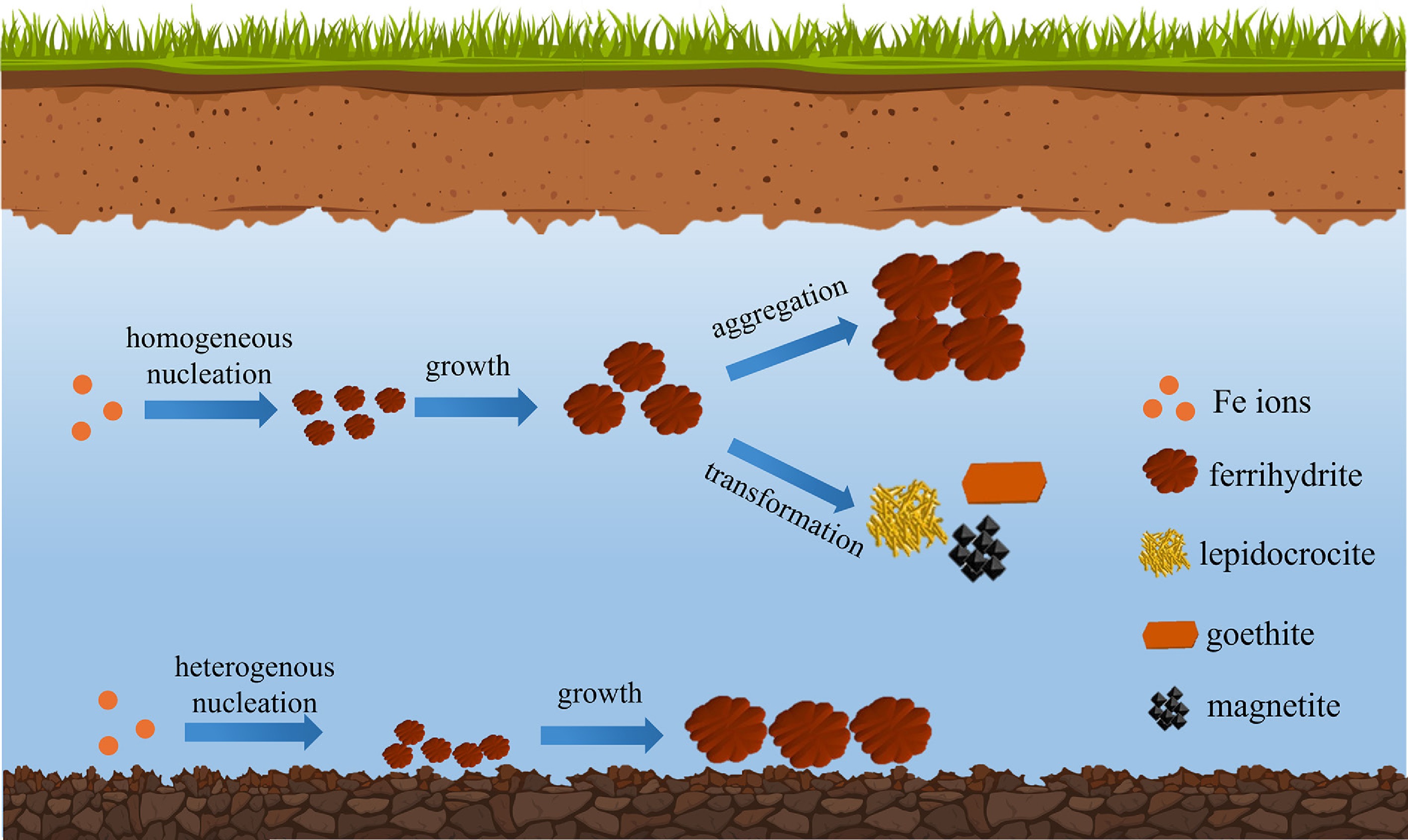

Once formed, IONPs undergo aggregation and phase transformation processes (Fig. 1), which control their long-term stability. Whether IONPs rapidly aggregate and subsequently deposit or remain as stable colloids over extended periods is essential for the fate and transport of IONPs and associated elements[29−33]. Metastable, poorly crystalline IONPs, such as ferrihydrite, are typically the first to form, and these phases then transform into more metastable phases gradually over time[24,25]. Whilst important processes, the review presented herein focuses on the initial formation of IONPs; the subsequent aggregation and transformation of IONPs will be reviewed in a future publication.

Figure 1.

The formation of IONPs through homogeneous and heterogeneous precipitation pathways, and their later growth, aggregation, and transformation.

While previous reviews have examined IONP formation, this review adopts an integrated perspective that emphasizes the coupling between the homogeneous and heterogeneous formation of IONPs (Fig. 1), with a focus on the synergistic roles of coexisting metal ions, organic matter, and microbes. By bridging multiple biogeochemical processes, this review provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the formation of IONPs. Such a holistic view is critical for advancing models of biogeochemical elemental cycling, improving predictions of contaminant transport and fate, and designing contaminant remediation strategies.

-

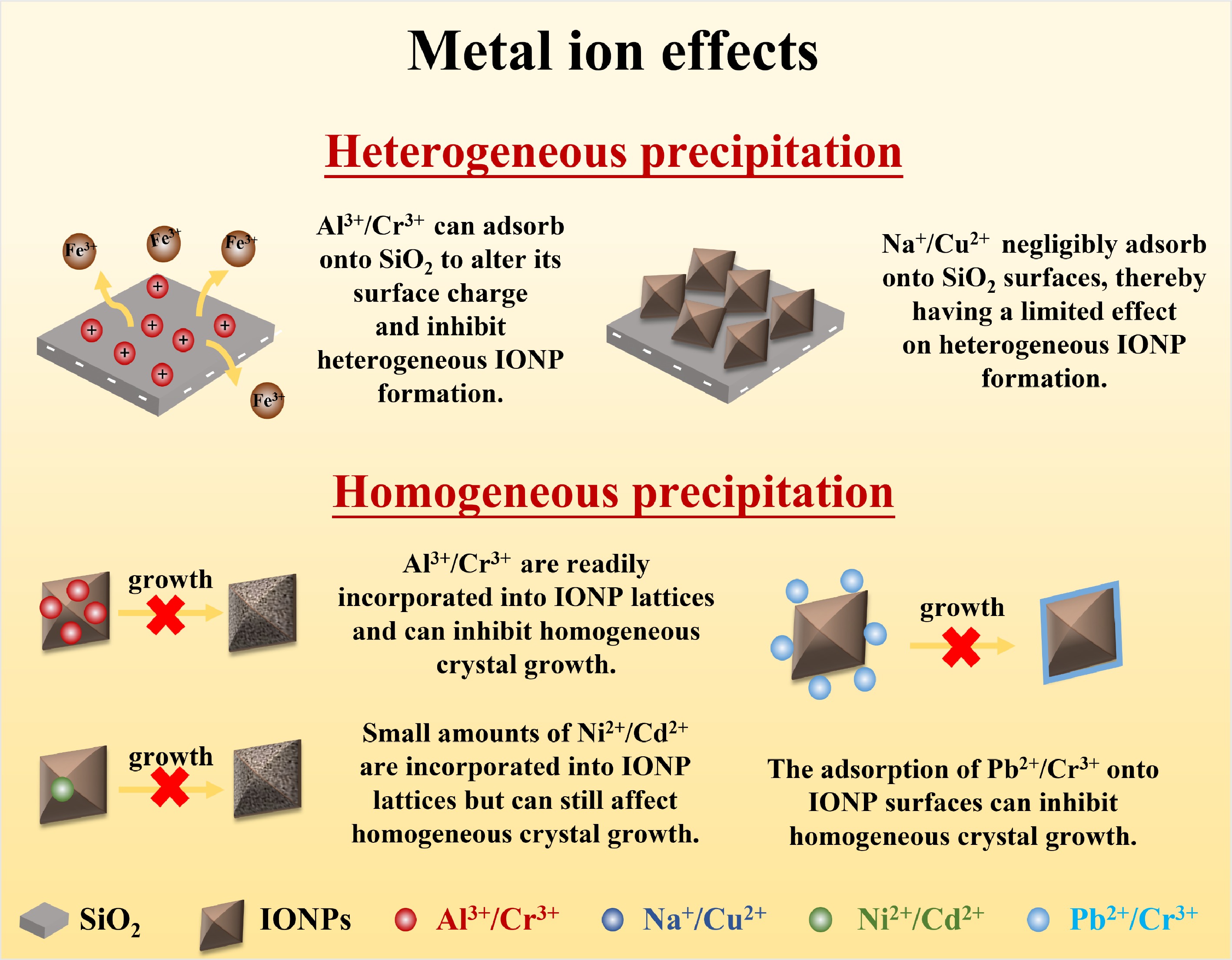

The precipitation of IONP at mineral surfaces (i.e., heterogeneous precipitation) is controlled by the properties of the surface, where surface functional groups (e.g., Al-hydroxyl groups) which affect surface charge and hydrophobicity, can strongly influence precipitate amounts, sizes, and compositions. These processes are further affected by solution chemistry, where the sorption of metal ions onto mineral surfaces can affect surface properties, to in turn further influence heterogeneous precipitation (e.g., through controlling local solution conditions and altering substrate surface charges). Additionally, metal ions can interact directly with IONPs: metal ion sorption onto IONP surfaces or structural incorporation via lattice substitution can affect homogeneous and heterogeneous growth rates and IONP reactivity (Fig. 2).

Metal ion-mineral interaction controls heterogeneous IONP formation

Effect of mineral surface properties on heterogeneous IONP formation through nucleation, growth, and deposition

-

Mineral surfaces in natural settings constitute solid–liquid interfaces that present favorable sites for the heterogeneous nucleation and growth as well as deposition of nanoparticles, such as IONPs[34,35]. Heterogeneous IONP precipitation can proceed via: (1) nucleation at the mineral surface through ion sorption to the surface or complexation with surface functional groups; and (2) subsequent growth through the attachment of aqueous Fe hydroxide monomers or oligomers; or (3) the direct deposition of IONPs homogeneously precipitated in the bulk solution[36]. All of these processes could be affected greatly by the physicochemical properties of the substrates (i.e., minerals).

Early work by Kretzschmar & Sticher on the transport of colloidal hematite (α-Fe2O3; positively charged at pH 5.7) in sandy soils as a function of aqueous calcium concentrations showed electrostatic interactions strongly controlled Fe oxide nanoparticle deposition rates[37]. Later, using synchrotron techniques with dilute Fe(NO3)3 solutions at pH 3.6, Jun et al. showed that Fe (hydr)oxide particles heterogeneously nucleated and grew on quartz surfaces, and that such heterogeneous precipitation did not solely depend upon a homogeneous particle deposition mechanism through substrate–homogeneous particle contact[38].

The above views were reconciled when Hu et al. showed that the heterogeneous growth of IONPs at pH 3.7 was suppressed on positively charged corundum relative to negatively charged mica and quartz, attributing this effect to repulsive electrostatic interactions between the substrate and Fe (hydr)oxide polymers, representing 'polymeric embryos'[19]. Therefore, electrostatic forces between substrates and homogeneous precipitates controlled their deposition onto substrates, while electrostatic forces between substrates and Fe (hydr)oxide polymers controlled heterogeneous growth rates.

Conversely, higher heterogeneous nucleation rates were observed on corundum, attributable to the high hydrophobicity of the corundum surface corresponding to a higher substrate-water interfacial energy, and hence a lower energy barrier for the IONP heterogeneous nucleation, than for quartz and mica, alongside a relatively suppressed growth rate[19]. Overall, such results highlighted a dependence of heterogeneous IONP formation on both electrostatic interactions, which controlled growth and deposition, and surface hydrophobicity, which controlled heterogeneous nucleation.

Besides surface charge and hydrophobicity, bond formation between functional groups at bare mineral surfaces and IONPs can also control IONP formation. For example, comparing mechanical mixtures of ferrihydrite and montmorillonite with ferrihydrite heterogeneously precipitated on montmorillonite in-situ, the latter ferrihydrite was more uniformly distributed across the montmorillonite surface. Further, ferrihydrite-montmorillonite contact was improved in the latter, and more Al-O-Fe bonding occurred through surface hydroxyl ligand exchange than in the former as mechanical mixtures[39]. Such bond formation with montmorillonite substrate was associated with a decreased reactivity for ferrihydrite during heat-catalyzed aging experiments relative to homogeneously precipitated ferrihydrite[40]. This reactivity effect was attributed to the formation of Si/Al-O-Fe bonds that stabilize the ferrihydrite structure against dissolution and in-situ reorganization[41], further work is however required to mechanistically understand and predict the role of substrate–IONP bonding in controlling IONP reactivity.

Metal-substrate interactions further influence heterogeneous IONP formation

-

As the deposition of homogeneous IONPs and attachment of Fe hydroxide monomers, dimers, and polymers during heterogeneous precipitation are strongly controlled by substrate surface-IONP electrostatic interactions, metal ion adsorption onto substrate surfaces, particularly for high oxidation state trivalent cations, can strongly influence substrate surface charges and thus affect heterogeneous IONP formation. For example, Dai & Hu showed that Cr3+ in solution adsorbs strongly onto quartz, flipping the surface charge of quartz at pH 3.7 from negative to positive[14]. In turn, the resulting electrostatic repulsion between quartz and positively charged Fe(OH)3 polymers and particles in solution virtually halted heterogeneous IONP precipitation on quartz. Later experiments under similar conditions in which the solution Fe3+/Cr3+ ratio was varied supported these results, showing decreased (Fe,Cr)(OH)3 heterogeneous precipitate total particle volumes (i.e., heterogeneous precipitation rates) at higher Cr3+ concentrations due to repulsive (Fe,Cr)(OH)3 polymer/particle–quartz surface electrostatic interactions through the above effect of Cr3+ hydrolysis product sorption on the surface charge of quartz[16].

A similar effect to Cr3+ was reported for Al3+ by Hu et al., who found that Al3+ co-precipitated with Fe3+ dramatically slowed heterogeneous IONP growth on quartz through Al3+ hydrolysis product sorption onto quartz, rendering its surface positive at pH 3.7[42], subsequently reducing the heterogeneous growth through the electrostatic repulsion between the positively charged quartz and Fe(OH)3 polymers/particles[19].

Quartz surfaces, with a low dielectric constant, were predicted to only adsorb hydrolyzed metal ions by the model reported by James & Healy[43]. Trivalent Al and Cr ions, which could form hydrolysis products under acidic pH conditions, could thus adsorb onto quartz surfaces. However, many monovalent and divalent metals (e.g., Na+, Ni2+, Pb2+, Mn2+, and Cu2+), which do not hydrolyze or weakly hydrolyze under acidic pH conditions, showed no measurable sorption onto quartz, and in turn negligibly affected the heterogeneous precipitation of IONPs at quartz surfaces through this electrostatic interaction mechanism. While for corundum substrates, which are associated with a high dielectric constant, cation sorption could proceed for both hydrolyzed and unhydrolyzed species. Therefore, many divalent cations (e.g., Pb2+, Mn2+, and Cu2+) strongly adsorbed onto Al2O3, rendering its surface more positively charged at acidic pH and thus inhibiting heterogeneous Fe hydroxide precipitation on Al2O3[15,44,45]. Overall, these results collectively highlight a pathway by which the heterogeneous nucleation and growth of IONPs are controlled by metal ion sorption onto substrate surfaces, altering surface charges to control substrate-Fe (oxyhydr)oxide polymer or particle electrostatic interactions. Further work is required to elucidate these processes for other environmentally relevant mineral surfaces beyond SiO2 and Al2O3, such as clay minerals as substrates.

Ionic strength can also affect nucleation and growth processes. For example, Jun et al. reported that increasing the ionic strength (1 to 100 mM NaNO3) for dilute Fe(NO3)3 solutions decreased the activity of aqueous Fe(OH)3 to result in diffusion-limited heterogeneous growth. This effect controlled not only IONP sizes but also the evolution of these particle sizes as a function of time[38].

Lattice incorporation of metal ions during IONP formation

-

A second mechanism by which metal ions can influence IONP formation is lattice incorporation (Fig. 2). Metal ions can be structurally incorporated through substitution into the growing IONP lattice, with such incorporation particularly favored for metal ions of similar valence and ionic radius to Fe3+, such that isovalent structural substitution results in a less distorted crystal structure.

Trivalent ions, with the same charge as Fe3+, were reported to be readily incorporated into the lattice of IONP through coprecipitation from solution. Cr3+, with a similar ionic radius (0.61 Å) as Fe3+ (0.64 Å)[46], can readily form (FexCr1−x)(OH)3 solid solutions; this substitution changes the solubility and particle size of the resulting hydroxide, often resulting in smaller particles with an increased number of defects. Lattice-incorporated Cr amounts were reported to be controlled by solution pH, with higher pH promoting more Cr incorporation[10,47], thereby indicating that hydrolyzed Cr species could be more readily incorporated into the lattice than unhydrolyzed ions. In the study by Xia et al of Fe/Cr coprecipitation[47], higher Cr incorporation in the coprecipitates was reported at higher pH. However, the mechanisms underpinning these results beyond a Cr3+ hydrolysis effect remain poorly understood. Indeed, the limited incorporation of these species at low pH could be attributed to the suppressed hydrolysis of cations under lower pH conditions: these unhydrolyzed cations predominantly remain in hydrated forms, and therefore lack structural compatibility with Fe(OH)3 polymers for lattice substitution. These findings with homogeneous Fe-Cr hydroxide coprecipitation were further corroborated by Zhang et al. with heterogeneous Fe-Cr hydroxide coprecipitation on alumina and silica powders as substrates under acidic pH conditions[48]. Compared with silica with lower pKa values, Zhang et al. reported that alumina surface hydroxyl group protonation raised the local pH near the substrate surface (pH ~3.7 to ~4.8). In turn, this increased pH favored Cr hydrolysis and subsequent heterogeneous Cr(OH)3 precipitation, thereby increasing the Cr/Fe ratios in the (Fe, Cr)(OH)3 coprecipitates[48]. Al3+, with the same valence as Fe3+ but with a smaller ionic radius (0.53 Å) and a smaller proportion of hydrolyzed ions at a given acidic pH, could substitute into the lattice but to a lower extent than Cr3+.

Such structural substitution of metal ions in Fe hydroxides caused lattice strains associated with their substitution. Buist et al. demonstrated that substituting a few percent of Fe with trivalent Al or Ga in ferrihydrite significantly changed particle morphology: Al or Ga incorporation inhibited growth on certain crystallographic planes, causing particles to change from roughly spherical to more cylindrical in shape[49]. These structural substitutions also modified the number of coordinated water molecules in the ferrihydrite structure and reduced crystallite size. Further, the structural substitution of metal ions could contribute to the much higher solubility of these metal hydroxides than that of pure Fe hydroxide.

Compared with trivalent ions, divalent cations exhibit limited hydrolysis in acidic solutions, and much smaller amounts are structurally incorporated into the ferrihydrite lattice under these low-pH conditions. However, these divalent metal ions can still profoundly affect IONP formation processes and properties, such as hindering the ripening and recrystallization of ferrihydrite. Dai et al. reported low Cu2+ contents in Fe (hydr)oxides coprecipitated at pH 3.7[14], which inhibited Ostwald ripening by affecting IONP dissolution[14]. Such a view is consistent with previous works, wherein Cu2+ decreased ferrihydrite reactivity and hindered transformation into more crystalline phases through inhibiting dissolution processes[50]. A similar inhibitory effect on ferrihydrite transformation through hindering dissolution was also reported for ferrihydrite coprecipitated with Ni2+, Co2+, and Zn2+[51], where Zn2+ either sorbs to the surface of ferrihydrite or forms a defective solid solution[52]. This effect of divalent cations on IONP reactivity likely occurs through 'pinning' the lattice to inhibit dissolution-reprecipitation processes[14]. Such results highlight that further work is required to understand how metal ions control the formation of IONPs and their reactivity.

Overall, the incorporation of exogenous cations into IONPs lattices is controlled by cation valence, ionic radius, and ion hydrolysis capabilities alongside the solubilities of the corresponding metal hydroxide endmembers. The incorporation of these species can cause lattice distortion, which generally inhibits perfect crystal growth and yields smaller, poorly ordered particles. Further, while qualitative trends suggest that lattice incorporation is favored for trivalent cations with ionic radii close to Fe3+ and high hydrolysis tendencies, a universal quantitative relationship between ionic radius, hydrolysis constant, and incorporation extent needs to be further established.

Metal ion surface adsorption controlling IONP growth processes

-

The adsorption of metal ions onto IONP surfaces presents a third mechanism for metal ions to control IONP formation (Fig. 2). Dai & Hu found that Pb2+ did not adsorb onto quartz surfaces but instead preferentially adsorbed onto or precipitated at the surface of IONPs to inhibit further crystal growth, attributable to the blockage of sites for Fe(OH)3 monomer or polymer attachment[14]. Meanwhile, Cr3+ could not only sorb onto quartz surfaces and substitute for Fe ions in the ferrihydrite lattice, but could also adsorb onto IONP surfaces to promote the precipitation of Cr hydroxides at the IONP surface[17]. Zerovalent Fe(ZVI) and Fe(II)-containing minerals are widely employed for the remediation of Cr contaminated sites, where the reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III) occurs together with the oxidation of Fe(II) to Fe(III) and subsequently results in Fe(III)-Cr(III) hydroxide coprecipitation. Surface adsorbed Cr or precipitated Cr hydroxides could be easily dissolved by dilute acid (pH ~3 HNO3), while structurally incorporated Cr doped in ferrihydrite lattices could not[16,17]. This dilute acid desorption approach has been commonly used in previous studies to differentiate binding mechanisms[16,17] and provides an effective distinction between surface association (i.e., adsorption or precipitation at the surface) and lattice substitution. This highlights differences in the efficacy of Cr immobilization over long timescales as a function of Cr uptake pathways for contaminated site remediation. Therefore, it is important to understand the specific incorporation mechanisms of metal ions for predicting their long-term fate in the environment[14].

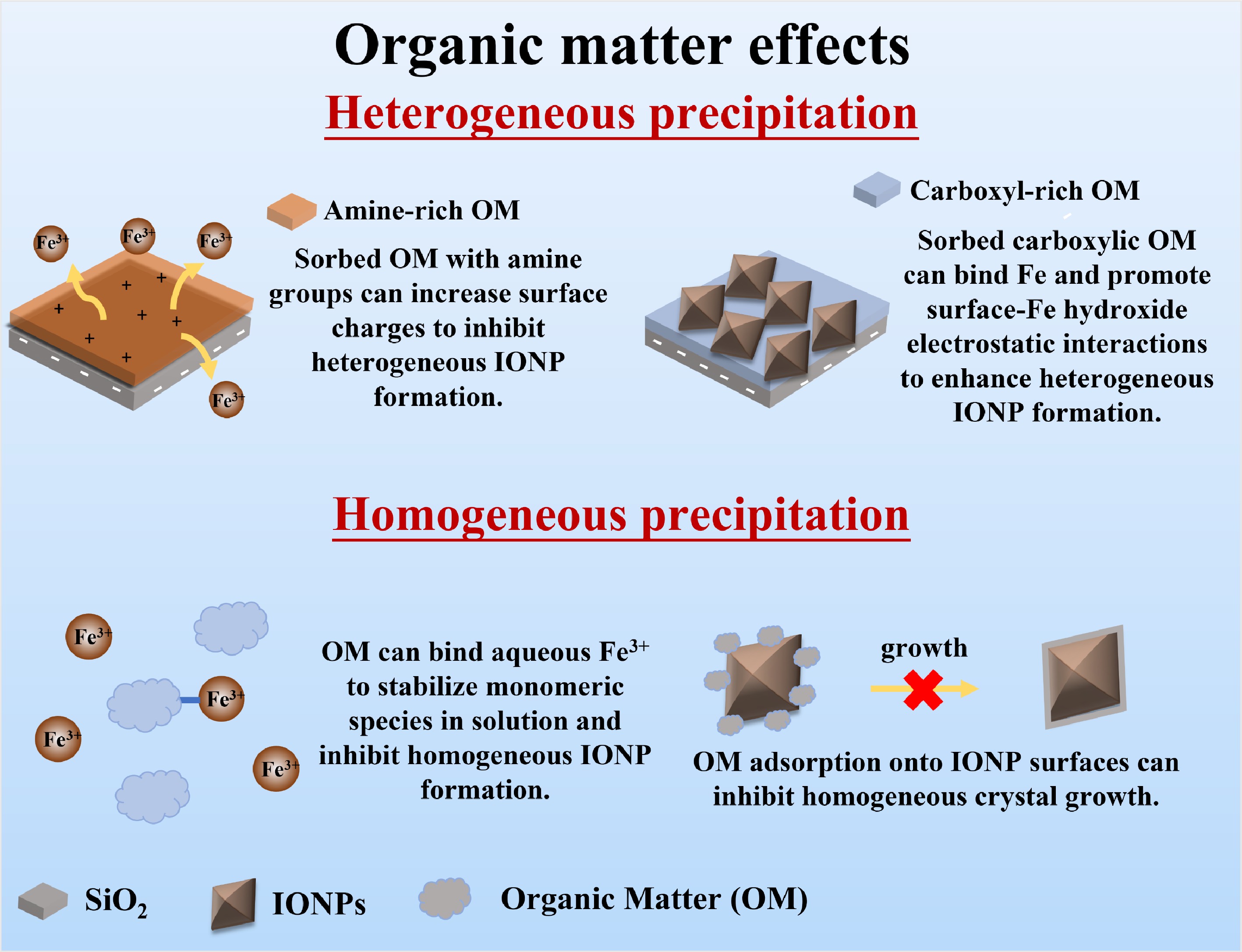

-

Organic ligands influence IONP formation mainly through three mechanisms: (1) surface adsorption of organics onto substrates as coatings, which can affect heterogeneous precipitation (especially via hydrophobic or electrostatic interactions); (2) complexation of dissolved organics with Fe(III) ions in solution, which inhibits homogeneous IONP precipitation; and (3) adsorption of organics onto IONP surfaces, which inhibits growth and affects its crystallinity, as strongly coordinating ligands prevent Fe-O-Fe bridging (Fig. 3). These three mechanisms are discussed in the following subsections.

Organic coatings on minerals affect heterogeneous IONPs formation

-

Organic coatings on mineral surfaces are ubiquitous in many natural settings, which constitute organic-liquid interfaces. These organic coatings can greatly alter the surface properties of minerals to promote or inhibit the heterogeneous precipitation of IONPs. Further, the physicochemical properties of the organic coatings could also affect the composition of the heterogeneous metal/Fe hydroxide coprecipitates.

Heterogeneous IONP precipitation can occur through nucleation, growth, and deposition, and organic coatings could affect these three processes to control heterogeneous precipitate amounts. On one hand, organic films generally alter the interfacial energy barrier for nucleation. Notably, the thermodynamic energy barrier to heterogeneous nucleation is a function of the interfacial free energy of the system, where higher substrate-fluid interfacial energies, as reported to be correlated with surface hydrophobicity[53], correspond to lower energy barriers to nucleation[54]. Meanwhile, bond formation between organics and IONPs, which lowers the substrate-precipitate interfacial energy, could also lower the energy barriers for heterogeneous nucleation. On the other hand, the adsorption of organics can alter the surface charges of mineral to control the heterogeneous growth through the attachment of charged Fe hydroxide dimers and polymers and the deposition of homogeneous IONPs, as both are dependent upon electrostatic interactions with the substrate[20]. Suwannee River natural OM (SRNOM)-treated Al2O3 was associated with a negative surface charge (relative to the positive surface charge of untreated Al2O3), and thus increased heterogeneous IONP precipitate amounts through favouring nanocrystal growth by monomer and polymer attachment and particle deposition[16,48]. Further, nanoparticle deposition rates on sandy soils for colloidal hematite increased after treatment with humic acid due to electrostatic effects[37]. With NOM coatings, heterogeneous IONP precipitate amounts increased with the presence of substrate surface carboxyl groups due to electrostatic interactions with negatively charged carboxylate groups and carboxyl-Fe complexation providing nucleation sites[18,20]. Conversely, amine groups imparted a positive surface charge to slow heterogeneous IONP growth[18].

Besides altering the precipitate amounts, organic coatings were also reported to greatly control the composition of heterogeneous Fe/Cr hydroxide coprecipitates. Organics could alter substrate surface charge and hydrophobicity, and thus can affect heterogeneous nucleation and growth rates, which control precipitate compositions to be distinct from those formed in bulk solution[36]. Our recent work showed that surfaces with adsorbed NOM become either hydrophobic or highly charged, depending on NOM ligands and composition. In this work, we demonstrated that at low NOM loading, aromatic moieties preferentially coated alumina surfaces, rendering them more hydrophobic and promoting heterogeneous Fe-Cr hydroxide nucleation. This yielding coprecipitates with high Cr/Fe ratios[20], since increased surface hydrophobicity can elevate the substrate–water interfacial energy (ΔGsl), thereby reducing the energy barrier for heterogeneous nucleation (ΔG*hetero)[19]. At higher NOM loadings, coating with NOMs containing high carboxylate group concentrations rendered substrate surfaces strongly negative, thereby promoting the electrostatic attraction of Fe(III) hydroxide monomers, oligomers, polymers, and particles onto substrates and greatly increasing the amount of (Fe, Cr)(OH)3 particle deposition[20] with a lower Cr/Fe ratio. In addition to altering surface hydrophobicity and charge, the formation of heterogeneous Fe/Cr hydroxides on organic-coated substrates has been reported to correlate with their functional group (de)protonation. For example, amine group protonation (R-NH2 to R-NH3+) was reported to be associated with an increased local pH that favored Cr hydrolysis and subsequently its incorporation into heterogeneous (Fex, Cr1−x)(OH)3 coprecipitates[18].

In summary, organic adsorption onto mineral surfaces can either inhibit or promote the heterogeneous precipitation of IONPs and affect IONP compositions, depending on the composition and properties of the organic coatings. Strongly bound or hydrophobic organic films tend to decrease thermodynamic energy barriers to promote nucleation, while certain NOM coatings can alter the surface charge to affect IONP growth and deposition. In addition, the surface (de)protonation of organics could affect the local solution pH and thus metal ion hydrolysis. These previous studies indicated the importance of physico-chemical properties of OM coatings on controlling the nucleation, growth, and deposition of IONP on organics, which control the amount and composition of heterogeneous Fe (oxyhydr)oxide formation on organic surfaces (Fig. 3).

Organic complexation with Fe(III) inhibits IONP formation, and its interactions with IONP affect its size and crystallinity

-

Organic ligands can profoundly alter IONP precipitation by complexing with aqueous Fe(III) ions. In solution, dissolved organics, especially those rich in carboxyl or phenolic groups, can complex with Fe(III) ions, sequestering these ions as stable monomeric or small oligomeric species. Such complexation suppresses Fe(III) hydrolysis and thus inhibits homogeneous nucleation. For example, Karlsson & Persson observed that aquatic NOM could form strong Fe-NOM complexes, which 'suppressed the hydrolysis and nucleation of Fe(III)'[55].

With large organic molecules, their complexation with Fe(III) ions can lead to the precipitation of 'insoluble Fe(III)-organic complexes' from solution, instead of forming Fe hydroxide mineral phases such as ferrihydrite. For example, Chen et al. found that coprecipitation with humic-rich dissolved organic matter yielded amorphous Fe–OM complexes with much higher organic content than Fe oxide alone, in some cases forming 'insoluble Fe(III)–organic complexes' at high C:Fe ratios rather than discrete mineral phases[56]. Likewise, fulvic and humic acids in natural waters can maintain Fe3+ in soluble complexes, often visible as yellow-brown 'organic iron' colloids in bogs and streams. Such Fe(III)-organic complexes could carry associated (in)organic pollutants over long distances through colloidal transport.

Besides forming 'insoluble Fe(III)–organic complexes' at high C:Fe ratios, organics could also lead to the formation of poorly crystalline Fe hydroxides. Eusterhues et al. showed that Fe(III) added to forest soil leachates precipitated as ultrafine two-line ferrihydrite intimately associated with the NOM, reflecting how organics can lock Fe into a poorly crystalline state[57]. Santana-Casiano et al. showed in marine water that the oxidation of Fe2+ in the presence of NOM was not only slower but also produced different Fe(III) precipitates than in ligand-free water[58]. Indeed, fulvic acid lowered the crystallinity of the Fe (oxyhydr)oxides, favoring nanocrystalline ferrihydrite or disordered lepidocrocite instead of well-formed crystals. These observations with NOM highlight that Fe3+ complexation by organics can divert Fe away from forming crystalline oxide lattices, instead favoring IONP nanoparticle products that are smaller, poorly ordered, and rich in organic functionality.

Not all organic ligands equally influence the behavior of Fe(III) species; however, ligand structure and binding functionality determine the extent of Fe(III) stabilization. Small monocarboxylate acids (e.g., acetate) form only weak complexes and thus have minimal effect on Fe precipitation, whereas multidentate or polycarboxylate ligands can strongly hinder nucleation. For example, in coprecipitation experiments with Fe(III)/Cr(III) hydroxides, acetic acid (a monodentate ligand) showed no significant effect on precipitation, while poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) and Suwannee River fulvic acid (a NOM reference material rich in carboxyl groups) dramatically inhibited Fe(III)/Cr(III) hydroxide formation[17]. PAA and fulvic acid formed strong complexes with Fe3+ to lead to suppressed IONP formation, where this incorporation of NOM also induced structural disorder with amorphous phases precipitating.

Besides NOM, specific low-MW organics with strong complexation capabilities with Fe(III) ions were also reported to affect IONP formation. Citrate, a tricarboxylic acid common in soils and organism exudates, binds Fe3+ ions strongly and dramatically modifies ferrihydrite formation. Even micromolar levels of citrate have been reported to impede the polymerization of Fe(O,OH)6 octahedra during ferrihydrite precipitation, resulting in much smaller particle sizes. Citrate effectively capped the growing Fe hydroxide oligomers, blocking edge- and corner-sharing linkages between octahedra and yielding nanocrystals only 2−3 nm across[59]. These findings align with other studies demonstrating that organic acids (like citrate or oxalate) can inhibit the nucleation and growth of IONPs by forming chelate complexes with Fe3+ or nascent Fe polymers.

Once nucleation begins and nascent IONPs form, organic ligands tend to adsorb onto the surfaces of those particles. The adsorption of organics, from simple acids to complex NOM mixtures, is a key mechanism by which particle growth is regulated. Generally, organic molecules can also act as growth capping agents, binding to nascent IONP nuclei and blocking certain crystallographic planes. This 'capping' effect inhibits crystal growth and leads to smaller, more disordered particles.

A number of studies have reported that organic adsorption halts the ripening and ordering of Fe (oxyhydr)oxide particles. For instance, citrate adsorbed onto ferrihydrite nuclei not only limited initial nucleation, as discussed above, but also inhibited subsequent particle growth by capping the surface. X-ray scattering analyses indicated that citrate-coated ferrihydrite aggregates consisted of small (2–3 nm) primary nanocrystals, whereas uncoated ferrihydrite could grow larger crystalline domains[59]. The adsorbed citrate anions adhere to Fe(III) polyhedral units, sterically and electrostatically hindering the addition of more Fe–OH units to the particle surface to 'freeze' the nanoparticle at a small size. Similarly, humic substances adsorbed on Fe oxyhydroxide surfaces can interfere with crystal growth and promote nanoscale, high-surface-area products. Chen & Thompson observed that when Suwannee River fulvic acid was present during Fe(II) oxidation, the resulting Fe(III) phases were markedly less crystalline, consisting of finely divided ferrihydrite or lepidocrocite instead of well-formed crystals[60]. The fulvics likely adsorbed onto the freshly formed Fe (oxyhydr)oxide particles, curbing crystal lattice development.

In another study, increasing concentrations of humic acid caused 'structural disruptions of ferrihydrite', observed as extensive structural disorder and smaller coherent domain sizes, due to the intimate association of humic functional groups with the mineral during formation. Spectroscopic evidence showed that polar acidic groups in humics bound strongly to ferrihydrite surfaces, leading to an integrated organic–mineral structure with substantial lattice disorder[61]. Additionally, Eusterhues et al. showed that coprecipitating ferrihydrite with soil-derived dissolved organic matter (DOM) produced particles with substantially reduced crystallinity and particle sizes, where even small amounts of DOM were noted to 'strongly interfere with crystal growth, leading to smaller ferrihydrite crystals, increased lattice spacings, and more distorted Fe(O,OH)6 octahedra'[62]. In practice, IONPs formed in the presence of humic or fulvic acids or other organics are often poorly crystalline nanoparticles with high specific surface areas. Indeed, the blocking of crystal planes by adsorbed organic ligands (e.g., –COOH or –OH ligands) can trap structural defects and prevent IONP growth.

In summary, organic matter generally reduces the size and crystallinity of IONPs and alters homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation kinetics. Under homogeneous precipitation conditions, organic ligands binding Fe(III) in solution or adsorption onto the newly formed IONP surfaces can inhibit hydrolysis and nucleation. Under heterogeneous precipitation conditions, organics adsorbed onto substrates can either promote or inhibit IONP formation on the surface and alter the composition of the heterogeneous precipitates (Fig. 3).

It should be noted that the physicochemical properties of NOM are highly complex. Numerous studies have investigated this aspect using various types of NOM and model OM (MOM), aiming to elucidate the roles of different factors, such as aromaticity, hydrophobicity, molecular weight, and functional group composition, as summarized below:

● Aromaticity and hydrophobicity of NOM: Organics rich in aromatic rings, such as high-aromatic NOM fractions or polyphenols, tend to adsorb via hydrophobic interactions. When such aromatic moieties coat a surface, they can render it more hydrophobic, which in some cases promotes heterogeneous nucleation by lowering the thermodynamic energy barrier to heterogeneous nucleation[20].

● Carboxyl content of NOM: Carboxyl-rich organics (e.g., fulvic acids, polyacrylic acid) impart a negative charge under conditions where carboxyl groups are deprotonated, which have different effects on homogeneous or heterogeneous nucleation. Hu et al. showed that -COOH-coated surfaces 'attracted more Fe ions and oligomers of hydrolyzed Fe species and subsequently promoted heterogeneous precipitation'[18]. Such acidic groups can also bind to nuclei, slowing homogeneous growth, and nucleation has been shown to be inhibited by carboxyl-rich NOM or PAA, which form complexes with aqueous Fe ions[17].

● Molecular weight of NOM: High-molecular-weight NOM fractions (e.g., humic acids) tend to adsorb preferentially at interfaces, forming thick coatings on mineral surfaces. In contrast, low-molecular-weight organics (e.g., fulvic or small acids) preferentially remain in solution to a larger extent. Zhang et al. found that although higher molecular weight NOM preferentially coated alumina, the molecular weight itself did not significantly change the amount or Cr/Fe composition of heterogeneous (Fe,Cr)(OH)3 precipitates on NOM coatings. This suggests that NOM functionality (acidity, aromaticity) is more important than molecular weight[20] in controlling heterogeneous IONP formation on organics.

● MOMs: In addition to NOM, many MOMs (e.g., phenolic acids, oxalate, citrate, amino acids, or synthetic polymers) have also been reported to influence IONP formation. For example, small polycarboxylates, such as oxalate or citrate, can strongly complex with Fe and inhibit nucleation (e.g., requiring higher Fe concentrations for nucleation to occur)[63]. Indeed, synthetic ligands such as polyaspartate were shown to facilitate Fe-O-Fe oxolation within prenucleation clusters but also to incorporate Fe into an organic matrix, forming Fe-OM composite particles[64].

-

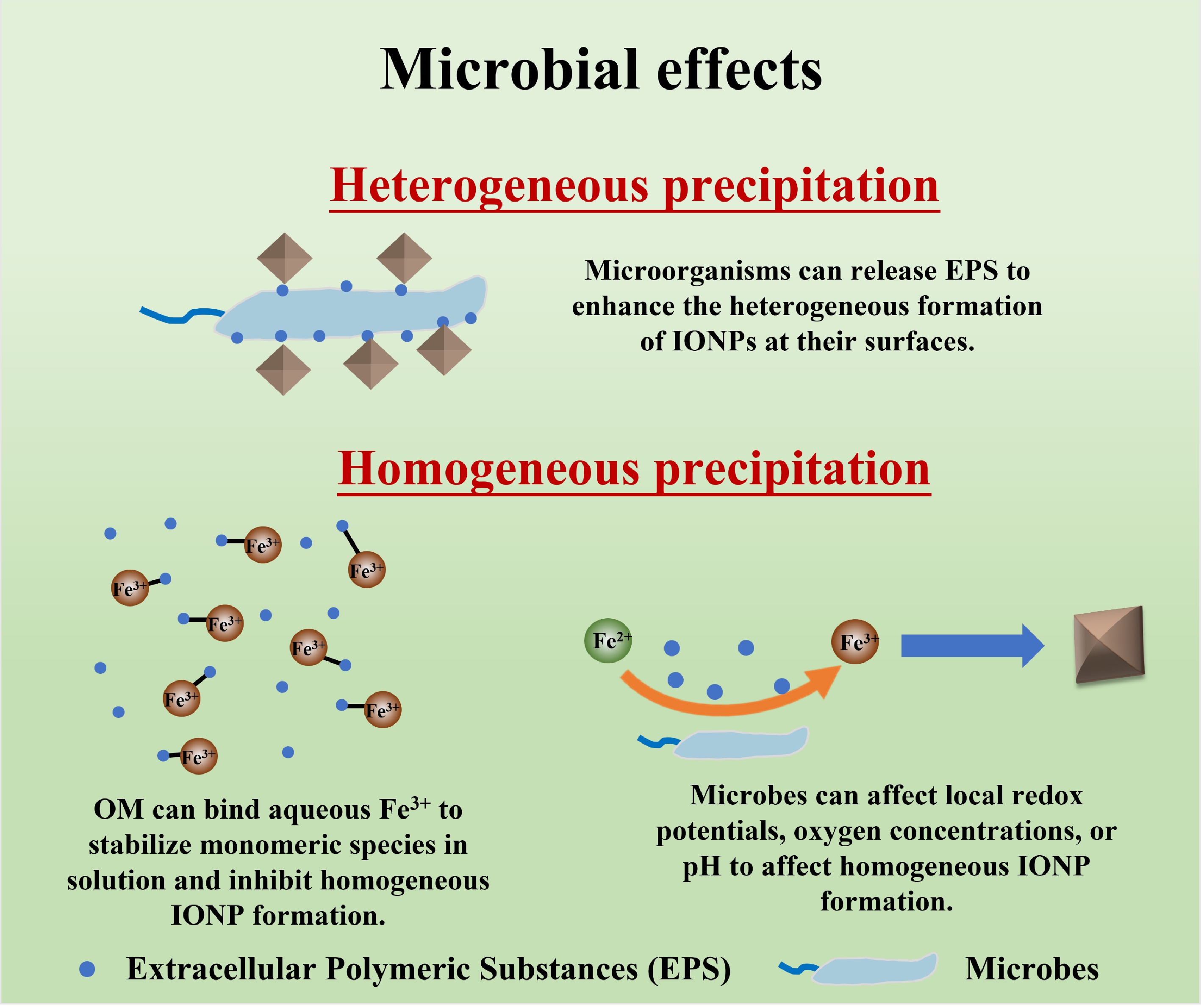

Microbial mediation introduces a level of biochemical and spatial specificity to IONP nucleation that is rarely observed in abiotic systems. In general, microbes affect IONP formation through redox metabolism and EPS secretion. Microbial influences on IONP formation can be categorized into: (1) heterogeneous nucleation on microbial surfaces (cells and biofilms acting as scaffolds); (2) Fe(III) complexation by microbial extracellular polymeric substances (EPS); and (3) redox mediation by microbial activity [the biotic cycling between Fe(II) and Fe(III)]. Understanding these microbially influenced processes is essential for predicting Fe cycling and mineral evolution in soils and sediments (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the mechanisms by which microbial activity can influence IONP nucleation and growth.

Heterogeneous IONP formation on microbial surfaces

-

Living cells and biofilms often serve as nucleation hotspots for Fe mineral formation. The surfaces of bacteria, algae, and fungi are typically rich in functional groups (e.g., carboxyl, phosphate, or hydroxyl groups) that can bind Fe3+ or Fe2+, concentrating Fe at the cell interface and inducing mineral precipitation. In many natural settings, IONPs precipitate directly onto microbial cell walls, sheaths, or biofilm matrices, rather than homogeneously in bulk solution[65,66]. This microbially mediated nucleation is especially prominent in environments where Fe2+ is biologically oxidized to Fe3+, such as in wetland soils, groundwater seeps, and hydrothermal systems. The freshly produced Fe3+ often hydrolyzes and nucleates on the nearest available surfaces, which are frequently the cells or extracellular structures of the Fe-oxidizing microbes themselves[67].

An important example is the precipitation of Fe coatings on Fe-oxidizing bacteria (FeOB) like Gallionella and Leptothrix in freshwater and Mariprofundus in marine systems. These neutrophilic FeOB use Fe2+ as an electron donor and promote localized Fe3+ production at the cell surface or extracellular sheath, which leads to supersaturation and triggers IONP nucleation (Fig. 4). In many cases, these processes result in the precipitation of poorly crystalline IONPs, such as ferrihydrite or lepidocrocite, often forming stalks or twisted filaments as mineralized structures closely associated with bacterial cells[65,66]. Previous works have shown that Gallionella ferruginea cells can become entangled in twisted stalks composed of IONPs embedded in EPS. That is, the bacterium produces an organic stalk, and the Fe(III)-bearing phase precipitates onto it, thereby yielding an Fe-encrusted biofilm. In this view, the biofilm provides nucleation sites that localize Fe precipitation to the microbial microenvironment. For example, Gallionella ferruginea generated twisted stalks comprising an organic polymer core (exopolymers) encrusted with IONPs[68]. Similarly, Chan et al. described how microbes in a flowing groundwater formed Fe-encrusted filamentous matrices: the bacteria 'create polymers that localize mineral precipitation', causing Fe oxyhydroxide to form on extracellular strands[67]. As these cells are in low-O2 niches, purely abiotic Fe oxidation is slow, but the microbes both catalyze the oxidation and immediately nucleate the resulting minerals on their surfaces. Overall, this results in a biogenic Fe (oxyhydr)oxide coating intimately associated with the cells and biofilm architecture.

Interestingly, microbes have evolved strategies to manage where Fe precipitates, preventing microbes from being effectively entombed during mineral precipitation. Many Fe(II)-oxidizing bacteria appear to promote Fe-bearing phase precipitation on extracellular appendages or polymeric slime, rather than the cell itself. For instance, a study on the marine photoferrotroph Rhodovulum iodosum (an anoxygenic Fe2+-oxidizer) found that during Fe(II) oxidation, 'cell surfaces were largely free of minerals; instead, the minerals were co-localized with EPS', indicating that EPS diverted Fe precipitation away from the cell envelope[69]. In this view, the EPS acted as a protective buffer: through rapidly binding Fe3+, nuclei formed on the EPS matrix outside of the cell, thus preventing cell encrustation. Such results highlight how microbial surfaces, which can broadly include the secreted biofilm matrix, can serve as nucleation substrates, with microbes promoting Fe mineral precipitation on otherwise inert parts of their anatomy.

Microbial surface-driven nucleation also has important implications for element cycling and contaminant dynamics. The Fe nanoparticles that form on cell surfaces often incorporate trace nutrients or toxins from the surrounding water. For example, bacteriogenic ferrihydrite precipitates can scavenge metals, such as As, Pb, or Zn, either through coprecipitation during formation or sorption processes onto the high specific surface area of the nanocrystals[70,71]. In wetland soils, rice paddies, and marshes, plant root surfaces similarly accumulate Fe (oxyhydr)oxide 'plaque' that harbors microbial communities. These roots leak oxygen, facilitating microbial Fe(II) oxidation and subsequent Fe(III)-(oxyhydr)oxide nucleation on the root epidermis[72]. The resulting root Fe (oxyhydr)oxide plaque comprises nanoparticulate ferric oxides entangled with microbial extracellular matter, and it can sequester phosphate or heavy metals from porewater. In coastal marine sediments, FeOB colonizing bioturbation tunnels or algal filaments likewise precipitate Fe(III) nanoparticles along those surfaces, in turn affecting Fe fluxes to the ocean[70]. Thus, by providing nucleation templates, microbial surfaces help control the size, distribution, and reactivity of IONPs in natural systems. This mechanism is a key component of microbially driven biomineralization, linking biological activity with inorganic mineral formation in the environment.

Microbial EPS influence homogeneous IONPs formation

-

Beyond serving as physical nucleation sites, microorganisms can mediate Fe mineralization through their EPS, which can profoundly influence Fe speciation and IONP formation. EPS are high-molecular-weight biopolymers (e.g., polysaccharides, proteins, lipids, nucleic acids) that microbes secrete into their surroundings, forming a gelatinous matrix in biofilms and sediments. The complexation of Fe3+ by EPS can stabilize Fe in solution or as colloidal complexes, altering the pathway and products of IONP precipitation[67]. For instance, microbial exopolysaccharides have been shown to strongly chelate Fe3+, preventing its rapid hydrolysis into large aggregates and instead yielding ultra-fine IONPs or stable organo-Fe colloids[73]. This means EPS can delay or modulate IONPs nucleation by maintaining Fe3+ in a complexed, more soluble form until critical saturation or other triggers induce precipitation (Fig. 4). The presence of EPS thus often leads to the formation of smaller, more dispersed IONPs compared to abiotic systems without organic ligands.

EPS can also catalyze Fe(II) oxidation and subsequent Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxide precipitation. Previous works have suggested that exopolymers from bacteria and algae may accelerate the oxidation of Fe3+ by oxygen by binding Fe2+ and facilitating electron transfer to oxidants[67]. In turn, EPS not only sequesters Fe3+ but can actively promote the generation of Fe3+ from Fe2+, effectively acting as a biomolecular catalyst for IONP formation. The Fe3+ produced can be immediately captured by nearby polymer sites, leading to the nucleation of minerals directly within or upon the EPS matrix. Chan et al. observed that neutrophilic Fe-oxidizing bacteria produce extracellular polysaccharides, which quickly mineralize with nanocrystalline hydrous ferric oxide when Fe2+ was available[67]. These mineralized EPS filaments form the backbone of Fe mats in environments like groundwater seeps, indicating that EPS provides both the chemical complexation and physical template for nanoparticle assembly[74].

Spectroscopic analyses (FTIR, XANES) can be used to confirm that Fe3+ binds to carboxylate and hydroxyl sites on EPS molecules, and these organo-Fe bonds can persist even as inorganic Fe–O–Fe networks polymerize. One study reported that Bacillus strains with abundant EPS yielded Fe (oxyhydr)oxide nanoparticles with different hydration and stoichiometry compared to an EPS-free control strain[73]. Specifically, EPS-associated ferrihydrite retained more structural water and had a lower Fe/O ratio, attributable to organic matter entwined with the mineral structure. The bound EPS can thus modify IONP properties such as crystallinity, charge, and reactivity. Moreover, when EPS is present, Fe (oxyhydr)oxide precipitates may form gel-like networks or coatings rather than discrete crystals[75], affecting how they interact with contaminants. For example, arsenate and other anions can be co-adsorbed by the positively charged Fe-EPS complexes during precipitation, enhancing immobilization in the environment[67,71].

The specific chemistry of EPS functional groups can also shape the IONP structure. Carboxyl-rich polysaccharides are often present in FeOB stalks and sheaths: Mariprofundus stalks are composed primarily of carboxylated polysaccharide fibrils[76], and Leptothrix sheaths contain acidic polysaccharides bearing –COOH groups[77]. These carboxylates can strongly bind Fe(III), templating oxyhydroxide nucleation but inhibiting dense crystal packing[76]. Similarly, amino groups (e.g., terminal –NH2 on glucosamine in Leptothrix EPS) can chelate Fe and direct mineral deposition[77]. In effect, EPS functional groups create a hybrid organic–inorganic scaffold: Fe–O complexes nucleate on polymers and yield highly hydrated, nanocrystalline (oxyhydr)oxides.

Indirect microbial mechanisms regulating IONP formation

-

Microorganisms can also influence IONPs formation indirectly by changing the geochemical environment: metabolic activities can produce gradients in oxygen concentrations, redox potentials, and pH to control the locations and pathways of IONP precipitation. For example, oxygenic phototrophs and nitrifying bacteria release oxygen, which raises local redox potentials and drives rapid abiotic Fe(II) oxidation in the vicinity of cells. Cyanobacterial blooms or photosynthetic mats can therefore precipitate Fe(III) oxyhydroxides purely by generating oxygen and increasing pH in the photic zone (Fig. 4). Conversely, nitrate reduction (denitrification) consumes protons and produces alkalinity, which can trigger Fe(II)-bearing phase precipitation and generate nitrite that can abiotically oxidize Fe(II). As shown for Acidovorax sp., biologically produced nitrite can oxidize Fe(II) chemically, but this effect is often secondary to enzymatic oxidation at ambient temperature[78]. However, nitrite-driven IONP precipitation can occur, especially when biological activity slows. Notably, both direct enzymatic oxidation and indirect oxidation via microbial metabolites (e.g., nitrite or oxygen) have been proposed in prior studies. While some works used genetic or chemical controls to distinguish these mechanisms, this review summarizes both pathways based on published findings without aiming to differentiate them experimentally.

Some bacteria are also known to mediate IONP formation by indirect means, such as through the release of siderophores (low molecular weight, high-affinity Fe(III)-binding compounds). While siderophores generally solubilize Fe(III), their Fe-complexes can undergo hydrolysis and nucleation under favorable conditions. In some cases, siderophore-Fe complexes can precipitate as mixed organic-inorganic phases, which may act as precursors to more crystalline IONPs[79]. For instance, catecholate-type siderophores can strongly bind Fe(III), thereby preventing immediate (oxyhydr)oxide precipitation. However, if this complex is oxidatively degraded or encounters a high degree of supersaturation, Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxide nucleation can occur, often associated with residual organic ligands[79]. Siderophore-mediated precipitation tends to produce extremely fine-grained or amorphous Fe–organic solids, given the controlled coordination environment, and these can later transform into crystalline oxides once the organic is removed or Fe(III) polymerizes beyond the complex capacity. Such a formation mechanism comprises both biotic and abiotic contributions, as the initial sequestration is biotic, but subsequent nucleation may be abiotic following a change in conditions.

Fungal organisms can also contribute to IONP formation, particularly in terrestrial environments. Fungi release various organic acids and chelators (e.g., oxalate, citrate), which solubilize Fe and subsequently participate in redox cycling or co-precipitation with IONPs[80]. The hyphal network may act as a physical scaffold for nucleation and growth, and fungal EPS can similarly affect particle size and morphology[81]. For example, fungi in acid soils can oxidize Fe2+ via Fenton-like reactions facilitated by organic metabolites, leading to ferrihydrite precipitates along fungal hyphae[79]. The biogenic ferrihydrite formed in fungal biofilms often shows poor crystallinity and intimate association with the organic matrix, akin to bacterial EPS-mediated products. However, the relative contribution of fungi versus bacteria to IONP genesis varies depending on the ecological setting and nutrient availability. In organic-rich litter or acidic forest soils, fungi may dominate Fe cycling, whereas in aquifers or rhizospheres, bacterial processes might be more influential.

Overall, microbial activity can strongly control nucleation processes: spatial localization (on cell surfaces or matrices), selective binding through biomolecules, and redox microenvironments can define the times and locations of IONP formation. These microbial factors result in IONPs in natural settings often being smaller, morphologically distinctive (e.g., stalks, sheaths, aggregates), or compositionally modified (with organic or heteroatom inclusion) compared to abiotically-formed IONPs.

-

This review highlights that the formation of IONPs in the environment is strongly influenced by the effects of metal ions, organic ligands, and microbial processes. IONPs form via complex sequences of nucleation and growth processes that are in turn controlled by solution chemistry and interfacial processes. In natural aquatic and soil/sediment systems, Fe2+ released during mineral weathering or produced through microbial reduction processes can be oxidized to Fe3+, with Fe3+ hydrolysis leading to solution supersaturation with respect to IONPs and the nucleation of Fe(III) (oxyhydr)oxide nanoparticles. This process can proceed homogeneously in bulk solutions or heterogeneously at solid-liquid interfaces, such as the surfaces of minerals, particulate organic colloids, or microbial extracellular matrices[82,83]. Both homogeneous and heterogeneous nucleation pathways contribute significantly to IONP formation. Homogeneously formed IONPs remain suspended in solution and facilitate the long-range transport of associated contaminants, whereas heterogeneously precipitated IONPs promote the retention of contaminant species on substrate surfaces. In turn, the distribution of IONPs as homogeneous and heterogeneous precipitates affects their environmental mobility and the fate of associated contaminants.

Following nucleation, growth occurs through Fe hydroxide monomer, oligomer, polymer, or particle additions onto nuclei as well as Ostwald ripening, where the latter proceeds with the growth of larger particles facilitated by the dissolution of smaller particles to gradually increase overall particle size and crystallinity[84]. Throughout these processes, metal cations, organic ligands, and microbes interact with nascent nuclei and growing surfaces, controlling crystallization to define particle size distributions, resulting crystallographic phases, and surface reactivity. Understanding these formation conditions is essential for predicting the environmental roles of IONPs in trace-metal sequestration, nutrient cycling and contaminant transport, and immobilization.

Metal cations can strongly influence IONP formation. Adsorbed multivalent ions can modify the surface charge or hydrophobicity of substrates to affect heterogeneous IONPs precipitation on substrates. Additionally, the lattice incorporation and surface adsorption of metal ions onto IONPs often inhibits homogeneous growth processes and yields smaller, poorly ordered particles.

NOM can also modulate IONP formation behavior. Organic adsorption onto substrates could affect surface properties and therefore control the heterogeneous formation of IONPs. Organics adsorbed onto IONPs can act as capping agents that block Fe–O–Fe polymerization to produce smaller, less crystalline IONPs. Additionally, dissolved organics could also hinder homogeneous IONP precipitation by strongly complexing with Fe3+ species.

Microorganisms can mediate IONP formation through several processes. FeOB oxidizes Fe2+ to Fe3+, precipitating IONPs on cell surfaces and within secreted EPS. The EPS provides nucleation sites but restricts crystal growth, yielding ultra-fine, poorly crystalline IONPs. These biotic redox processes strongly affect the long-term behavior and preservation of IONPs to affect the fate of associated contaminants.

Outlook

-

Advancing our understanding of IONPs in environmental systems will require both deeper mechanistic insights and broader, more integrative studies. Notably, forming a molecular-level mechanistic understanding of IONP formation and associated interfacial processes constitutes an important area for future research. Existing instrumentation employed in the current literature that can facilitate the investigation of IONP formation is summarized in Table 1. For example, time-resolved synchrotron X-ray spectroscopy and scattering and high-resolution in-situ liquid transmission electron microscopy under reaction conditions can capture the dynamic steps of nanoparticle formation in real time. These methods, coupled with isotopic tracing and advanced surface analyses, now make it possible to directly characterize the speciation of metals and ligands at nanoparticle surfaces. Applying these tools to follow in situ Fe (oxyhydr)oxide nucleation will provide invaluable atomic-level insight.

Table 1. Analytical techniques currently employed in the literature for characterizing IONP formation and stability

Technique Application Strengths Limitations TEM/HRTEM Particle size, morphology, crystallinity High-resolution imaging Limited statistics, vacuum conditions XRD Crystalline phase identification Phase identification, crystallinity Poor sensitivity for amorphous or very trace crystalline phases Mössbauer spectroscopy Fe speciation, oxidation state Sensitive to Fe valence and coordination Requires specialized expertise and, in some cases, isotopic enrichment FTIR/ATR-FTIR Organic functional group interaction Identifies surface ligands and bonding Limited structural detail XPS Surface elemental composition and chemical bonding states Highly surface sensitive Shallow probing depth, vacuum conditions ICP-MS/SP-ICP-MS Elemental quantification / particle sizing High sensitivity / nanoparticle detection Requires careful calibration DLS/ζ-potential Colloidal size and surface charge Quick, aqueous-phase measurements Affected by polydispersity AFM Nucleation behavior on surfaces In situ, nanoscale resolution Limited to flat surfaces Synchrotron XAS (XANES/EXAFS) Oxidation state, local atomic structure Element-specific, coordination environment Requires beamtime access, long analysis times. Cryo-TEM Imaging particles in native hydrated state Preserves original morphology Technically demanding In situ SAXS/WAXS Real-time nanoparticle nucleation/growth kinetics Time-resolved, non-destructive Requires synchrotron or advanced lab setup In-situ liquid-TEM Real-time imaging of nucleation, aggregation Direct observation in liquid; dynamic tracking Beam damage risk; low throughput High-energy X-ray scattering Amorphous or short-range ordered structure analysis Suitable for disordered materials Needs synchrotron access There is a need to more fully incorporate highly complementary atomistic modeling. Continued development of accurate force fields for Fe–organic–water systems and increased computational power mean that simulations can now address larger, more realistic nanoparticle-interface systems. By combining experiments with atomistic simulations, molecular mechanisms can be validated with unprecedented detail. Such an approach will move the current approach beyond empirical correlations and toward a predictive understanding of IONP behavior under varying environmental conditions.

It is increasingly important to examine how climate change and environmental perturbations may alter IONP cycling and to incorporate these considerations into future research. Climate-driven shifts in temperature, precipitation patterns, and chemistry will likely modify the factors that govern IONP's formation. For example, pH shifts, such as through the potential acidification of surface waters by the increased atmospheric CO2 concentrations, will influence the solubility and surface charge of IONPs to affect their formation. Further studies of such changes in environmental conditions will provide an improved understanding of their potential impacts on water quality, nutrient cycling, and contaminant mobility that could arise from associated changes in IONP formation behavior.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Li Z, Goût TL, Hu Y; visualization, writing − original draft: Li Z; writing − review and editing: Goût TL, Hu Y; resources, supervision: Hu Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this acrticle as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 42177193 and 42107265), and Yunnan Provincial Science and Technology Project at Southwest United Graduate School (202302AP370002).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

This review integrates the environmental metal-organic-mineral-microbial interactions that shape IONP formation.

Metal ions modulate IONP formation mainly via lattice doping and adsorption onto IONP and substrates surfaces.

Organic adsorption and complexation with IONPs and substrates control their homogeneous and heterogeneous precipitation.

Microbials alter IONPs by EPS release and redox alteration.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Zhixiong Li, Thomas L. Goût

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li Z, Goût TL, Hu Y. 2025. Review on formation of iron (oxyhydr)oxide nanoparticles in the environment: interactions with metals, organics and microbes. Environmental and Biogeochemical Processes 1: e003 doi: 10.48130/ebp-0025-0005

Review on formation of iron (oxyhydr)oxide nanoparticles in the environment: interactions with metals, organics and microbes

- Received: 02 July 2025

- Revised: 06 August 2025

- Accepted: 21 August 2025

- Published online: 15 September 2025

Abstract: Iron (oxyhydr)oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) are formed in many aquatic and soil systems through nucleation and growth in solution (homogeneous precipitation), and at soil-water interfaces (heterogeneous precipitation). This review summarizes the roles of metal ions, organics, and microbes in the nucleation and growth of IONPs in natural settings. Metal ions can adsorb onto mineral surfaces that act as substrates to modify heterogeneous precipitation processes at soil (mineral/organic)–water interfaces. Further, metal ions could also affect homogeneous precipitation through lattice substitution or surface adsorption onto IONPs. Similarly, organic matter can interfere with heterogeneous IONP formation through adsorbing onto mineral surfaces, and can affect homogeneous IONP formation by complexing with iron ions and adsorbing onto IONP surfaces. Indeed, the physicochemical diversity of mineral surfaces and organic matter properties, especially regarding organic functional groups which have varied complexation and (de)protonation capabilities, can profoundly affect these processes. Microbial influences arise through the production of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and the redox modulation of the surrounding environment, which alter electron transfer dynamics and surface reactivity to affect the formation of IONPs. This review provides an integrated view of the roles of metals, organics and microbes in IONP formation, which can not only help in the understanding of the iron cycle, but also the biogeochemical fate of contaminants.