-

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs), which are widely emitted by industrial processes, transportation, and other anthropogenic activities, pose significant environmental and public health risks due to their persistence and reactivity[1]. Among the aliphatic VOCs, propane stands out for its chemical inertness and structural stability, leading to prolonged atmospheric residence, diffusion, and participation in photochemical reactions that exacerbate air pollution. Propane, which is primarily sourced from petrochemical industries and vehicular exhaust, acts as a precursor to greenhouse gases, contributing to ozone formation and global climate change[2,3]. During atmospheric oxidation, propane can be partially converted to highly reactive propylene, which has a high photochemical ozone creation potential (POCP) and plays a critical role in the formation of tropospheric ozone and photochemical smog, thereby aggravating air quality degradation and health hazards[3]. Effective control of propane and other short-chain alkane emissions is thus imperative to mitigate photochemical smog and improve air quality.

Catalytic combustion has emerged as a promising technology for VOC abatement because of its energy efficiency and minimal secondary pollution. Catalyst selection is pivotal, with noble metals (e.g., Pt) demonstrating exceptional activity for short-chain alkane oxidation[4,5]. Recent studies have reported high catalytic efficiency for Pt/ZrO2 and Pd/NiO in the oxidation of small hydrocarbons[6,7]; however, their high cost, poor stability, and sintering susceptibility hinder their large-scale application[8,9]. Consequently, the development of high-performance non-noble metal catalysts is urgently needed.

Transition metal oxides (e.g., Ce, Mn, Co) have shown promising catalytic performance in VOC combustion[10]. Cobalt oxide (Co3O4) is particularly effective for catalytic combustion of propane[11]. In its spinel structure, Co2+ ions occupy tetrahedral sites, whereas Co3+ resides in octahedral positions. Although debates persist regarding the roles of Co2+ and Co3+, the consensus suggests that Co3+ serves as the primary active site for oxidation[12]. The reduction of Co3+ to Co2+ generates oxygen vacancies, facilitating the adsorption and activation of O2[13]. Enhanced catalytic activity is achieved by exposing the (220) facet, which promotes the formation of oxygen defects[14]. Morphological engineering (e.g., nanospheres, mesoporous structures) to maximize exposure of the (220) facet has become a key strategy[15,16]. Metal doping further modulates electronic and structural properties, as evidenced by improved activity and stability in bimetallic systems such as Co–Mn–O and Cu–Co–O[17]. Zirconia (ZrO2), renowned for its redox amphoterism and thermal stability, activates O2 via surface paramagnetic F-centers to generate OV[18]. Despite its wide use as a support for noble metals and transition metals (e.g., Pt/ZrO2 for methane oxidation[19] and ZnZrxOy for propane combustion[20]), its role as a dopant in low-carbon pollutant oxidation remains underexplored, necessitating further study of Zr-based synergistic effects.

Synchrotron vacuum ultraviolet photoionization mass spectrometry (SVUV-PIMS) has emerged as a pivotal analytical tool in combustion and catalytic research since its initial application to low-pressure laminar premixed flame studies at the Advanced Light Source – Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Its unique ability to resolve combustion processes and reaction mechanisms became evident through the precise detection of reactive intermediates. In 2003, the National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (NSRL) of the University of Science and Technology of China established the world's second SVUV-PIMS platform, enabling groundbreaking studies on hydrocarbon combustion[21], nitrogen-containing fuels[22], and biomass-derived systems[23]. By scanning photon energies to acquire photoionization efficiency (PIE) spectra, this technique accurately determines ionization thresholds, enabling isomer-specific identification. Near-threshold soft ionization preserves molecular ions' integrity by minimizing fragmentation, whereas supersonic molecular beam sampling suppresses collisional interference, allowing the capture of short-lived radicals and transient intermediates—a cornerstone for reconstructing complex reaction networks.

Traditional gas chromatography‒mass spectrometry (GC‒MS) primarily detects stable products in gas‒solid catalytic reactions but fails to identify short-lived intermediates. SVUV-PIMS overcomes this limitation by directly probing desorbed transient species from catalyst surfaces, often coupled with GC‒MS, to provide comprehensive mechanistic insights. Recent advancements have been particularly transformative in alkane oxidative dehydrogenation (ODH) systems. Huang et al.[24] pioneered the identification of methyl radicals in methane oxidative coupling (OCM), confirming their origin from surface methane dehydrogenation. Subsequent studies on Li-MgO-catalyzed OCM and ethane ODH (ODHE) further identified ethyl radicals, ketene, and peroxide intermediates via the PIE spectra, refining the reaction networks for both systems[25,26]. Zhang et al.[27] systematically investigated the ODH mechanisms of ethane and propane via this platform. In Fischer–Tropsch synthesis (FTS), Jiao et al.[25] elucidated the bifunctional mechanism of ZnCrOx-MSAPO catalysts, which was attributed to enhanced CO conversion (up to 17%) and C2–4 olefin selectivity (80%–94%) to ketene intermediates generated on ZnCrOx and subsequently converted to olefins on MSAPO. The ultrashort lifetime of ketene necessitated supersonic beam sampling, underscoring the critical role of SVUV-PIMS in pathway validation. With unparalleled sensitivity and isomer selectivity, SVUV-PIMS has become indispensable in combustion chemistry and is redefining catalysis research. Its real-time detection of transient intermediates visualizes traditionally elusive surface processes, offering atomic-level mechanistic evidence. Advancements in fourth-generation synchrotron sources and time-of-flight mass spectrometry now enable the measurement of interfacial processes beyond gas-phase reactions. Emerging applications in single-atom catalysis and biomass conversion are driving mechanism-guided catalyst design. Future integration with ultrafast spectroscopy and in situ microscopy promises transformative discoveries in energy catalysis and environmental remediation, laying molecular-scale foundations for green catalytic systems optimized for efficiency, selectivity, and stability.

Building on our prior research[28], this study employs SVUV-PIMS to dissect the propane catalytic combustion mechanism of CoxZry catalysts at the molecular level. By integrating in situ SVUV-PIMS with temperature-programmed surface reaction (TPSR) experiments and Chemkin simulations, we elucidated the dynamic interplay between surface intermediates and catalytic pathways.

-

A variety of Co‒Zr mixed oxide samples with different Co‒Zr molar ratios were prepared via the sol‒gel method. For example, 0.012 mol of Co(NO3)2·6H2O, 0.003 mol of Zr(NO3)4·5H2O, and 0.03 mol of citric acid were dissolved in 50 mL of deionized water. The solution was stirred at 80°C for 8 h to obtain a gel, dried at 100 °C for 24 h, and finally calcined in static air at 600 °C for 4 h. The obtained catalyst was called Co4Zr1. Other catalysts were synthesized in a similar manner and named CoxZry, where x/y is the nominal Co/Zr molar ratio in the catalyst. The pure cobalt oxide was called Co3O4.

Chemkin simulation

-

In this work, numerical simulations were performed by using Chemkin PRO software to compare heterogeneous (catalytic) and homogeneous (gas-phase) combustion mechanisms. The gas-phase combustion kinetics of propane were investigated under identical equivalence ratios, pressure conditions (atmospheric), and reactor geometries via the kinetic model developed by Curran's group[29]. The simulation employed a closed homogeneous reactor configuration with a volume of 39 cm3 and a vent area of 1 cm2. The gas flow velocity was set to 40 cm3/s under isothermal conditions at 500 K. Through an analysis of the simulation results, the detailed reaction pathways governing propane combustion were elucidated.

Synchrotron radiation vacuum ultraviolet ionization mass spectrometry

-

The SVUV-PIMS experiments in this work were performed at Beamline BL09U of the Hefei Light Source (HLS), a nationally recognized synchrotron radiation facility renowned for its high photon flux, tunable spectral range, and superior polarization properties. The HLS infrastructure comprises an 800 MeV linear accelerator and an electron storage ring, operating stably with 11 versatile beamlines to support multidisciplinary research. At Beamline BL09U, the electron beam is accelerated to relativistic speeds in the storage ring after initial boosting by the linear accelerator, generating high-brightness synchrotron radiation via an undulator. The photon beam is then conditioned through a precision optical system, including a monochromator chamber equipped with three interchangeable spherical gratings for continuous photon energy tuning (6–124 eV), a filtering chamber for harmonic suppression, and an experimental station for SVUV-PIMS analysis. This configuration enables high-resolution, isomer-selective detection of transient intermediates, leveraging HLS's advanced photon source capabilities to elucidate catalytic reaction mechanisms at the molecular level. Beamline BL09U integrates a flow tube reactor (FTR) coupled with SVUV-PIMS and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC/GC‒MS) as a unified experimental platform, which is specifically engineered for probing gas-phase reaction kinetics in combustion chemistry, atmospheric chemistry, and related disciplines. The system comprises a controlled evaporation and mixing (CEM) module for precise reactant vaporization and homogeneous gas-phase mixing, a temperature-programmable FTR housed within a tubular furnace for controlled thermal reactions, an SVUV-PIMS assembly for real-time detection of reactive intermediates via tunable photon energy ionization, and a downstream GC‒MS unit for complementary analysis of stable products. This multimodal configuration enables synchronized characterization of transient species and thermodynamically stable products across varying timescales, providing mechanistic insights into complex reaction networks.

-

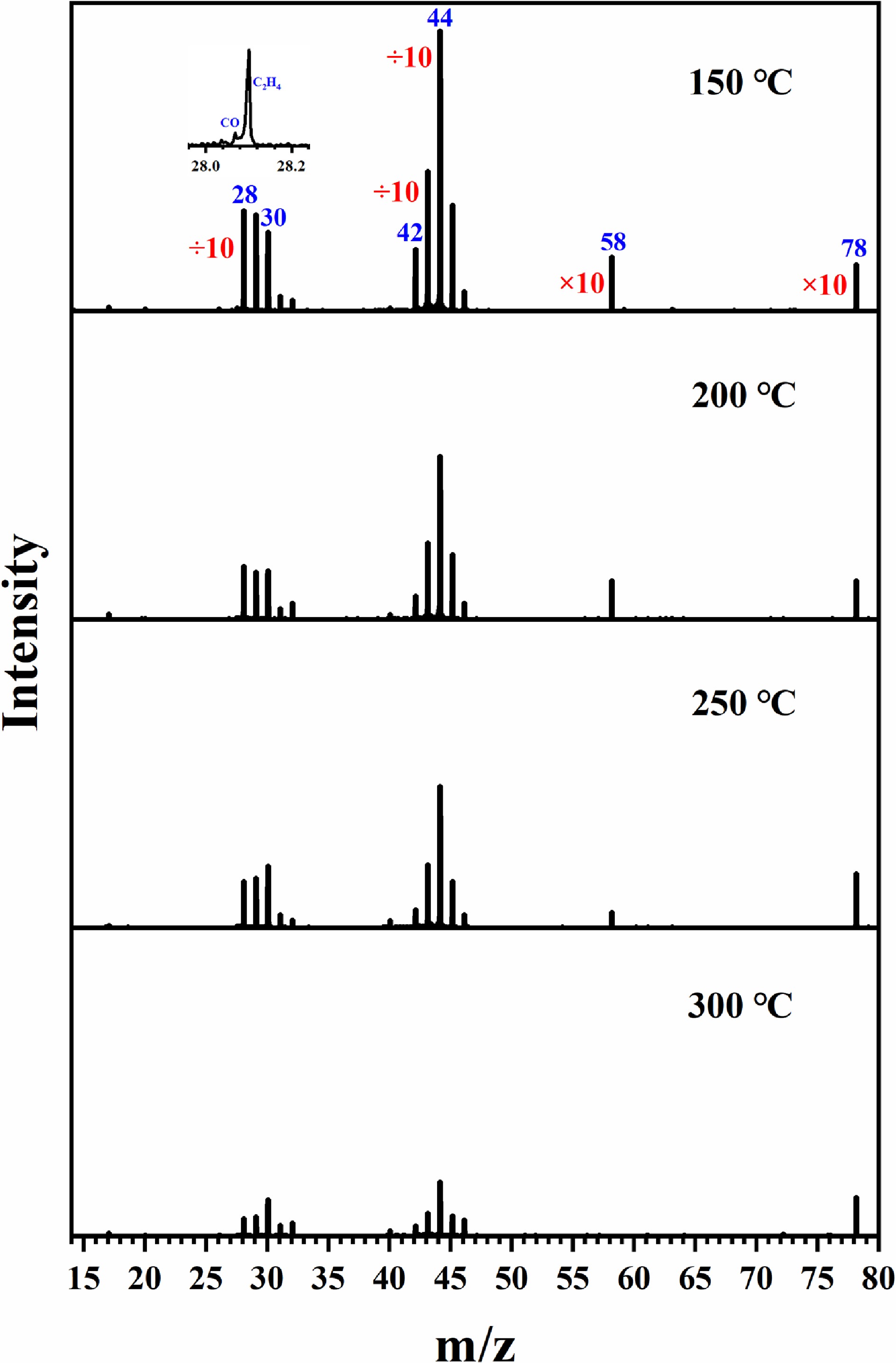

In a previous study[28], the analysis of stable products generated from propane over CoxZry catalysts was conducted via coupled chromatography‒mass spectrometry techniques. However, these methods have limitations in detecting unstable reaction intermediates. To address this constraint and gain deeper insights into the catalytic reaction mechanism, the present study implemented a synchrotron radiation photoionization mass spectrometry (SR-PIMS) platform. Catalytic experiments under atmospheric pressure were performed on both Co3O4 and Co4Zr1 catalysts under identical gas-phase conditions (total flow rate: 100 sccm; propane concentration: 0.2%; oxygen concentration: 5%). Figure 1 displays the mass spectra acquired by SVUV-PIMS for the Co4Zr1 catalyst at reaction temperatures of 150, 200, 250, and 300 °C with a 12 eV photon energy. A series of mass spectral peaks were detected at mass‒charge ratios (m/z) of 17, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 40, 42, 43, 45, 46, 58, and 78. Peaks with odd m/z values predominantly correspond to radical species or fragment ions. For example, the m/z 17 and 29 signals were assigned to fragments generated during the ionization process.

Figure 1.

For the catalytic oxidation of propane by Co4Zr1, mass spectra were collected at an energy of 12 eV at different temperatures.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, SVUV-PIMS successfully detected multiple intermediates in the catalytic combustion of propane over the Co4Zr1 catalyst, including carbon monoxide (m/z = 28), ethylene (m/z = 28), formaldehyde (m/z = 30), ketene (m/z = 42), acetaldehyde (m/z = 44), n-butane (m/z = 58), and benzene (m/z = 78). Notably, the detection of carbon monoxide at a photon energy of 12 eV is likely attributed to the presence of higher-order harmonics in the experimental setup. The observed peak at m/z = 46 was identified as a background signal originating from ethanol contamination in the mass spectrometer. A distinct attenuation trend in the corresponding mass spectral intensities was observed with increasing reaction temperatures, and detailed mechanistic interpretations are systematically discussed in subsequent sections.

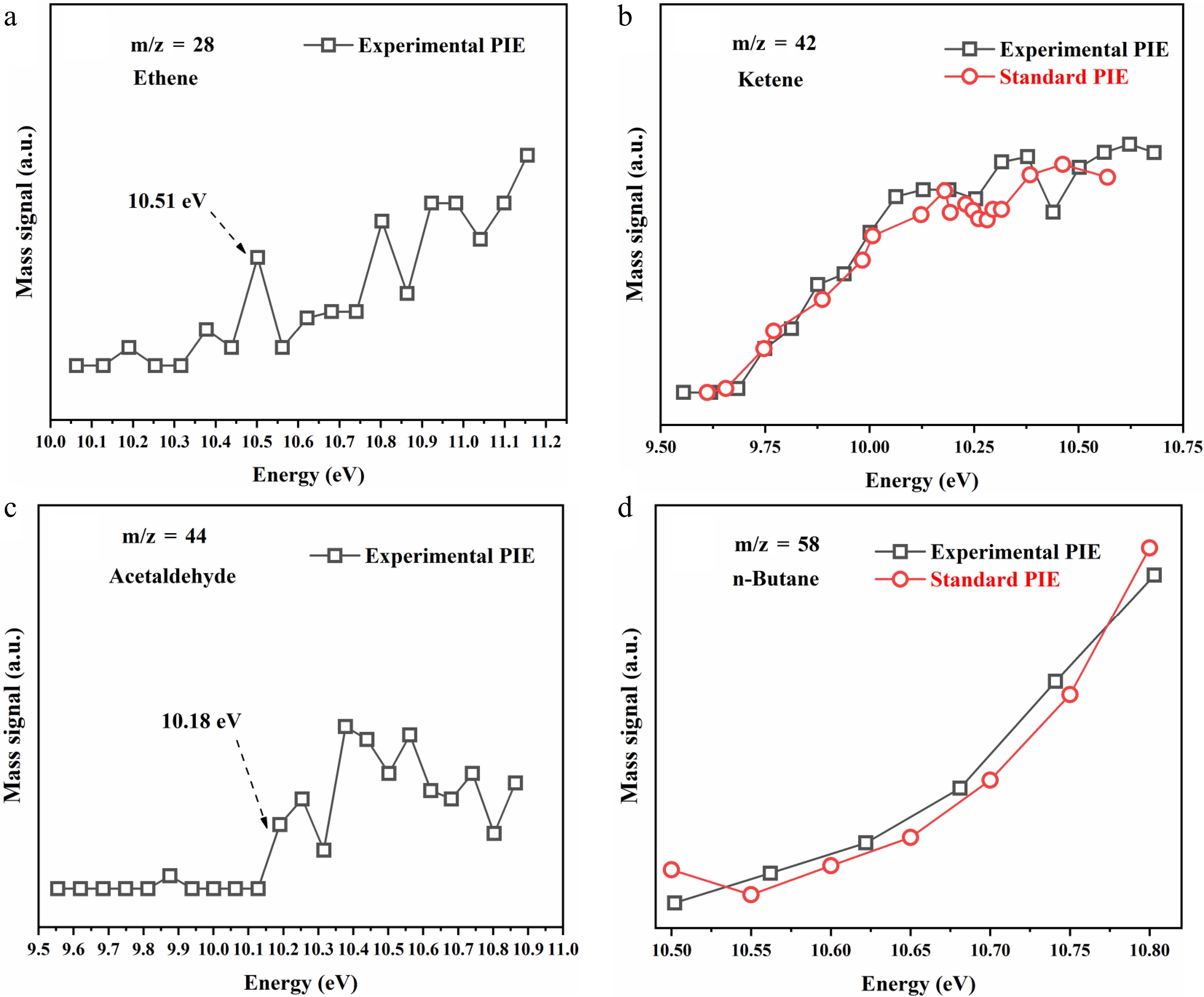

Figure 2 presents the photoionization efficiency (PIE) curves and identification results for key products in catalytic combustion of propane at 150 °C. The measured ionization energies of C2H4 (10.51 eV) and C2H4O (10.18 eV) closely align with the literature values for ethylene (10.52 eV)[30] and acetaldehyde (10.20 eV)[31], respectively. Furthermore, the observed PIE profiles of C2H2O and C4H10 match well with the reference spectra of ketene[30] and n-butane[32], confirming their identities. These identified intermediates collectively demonstrate the coexistence of multiple parallel and competitive reaction pathways during propane oxidation over the Co4Zr1 catalyst.

Figure 2.

Species identification of the main products in the Co4Zr1-based catalytic oxidation of propane, showing the PIE spectra and identification results of (a) m/z = 28 (C2H4), (b) m/z = 42 (C2H2O), (c) m/z = 44 (C2H4O), and (d) m/z = 58 (C4H10) during the catalytic combustion process of propane.

The detection of ethylene suggests initial C‒H bond dehydrogenation of propane on the catalyst surface, generating propyl radicals that subsequently undergo cleavage. This implies that the catalyst provides sufficient active oxygen species or oxygen vacancies to promote both primary dehydrogenation and bond scission of alkanes. The presence of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde indicates partial oxidation pathways, where surface-active oxygen preferentially oxidizes propane or its cleavage products to form oxygenated intermediates (e.g., alcohols or aldehydes), which are subsequently converted into smaller oxygenates.

The identification of ketene further substantiates complex oxidative routes, potentially involving either deep oxidation of ethylene or radical-mediated oxidative processes. Ketene formation typically correlates with oxidative dehydrogenation of ethylene, highlighting a gradual transformation pathway from hydrocarbons to oxygenated intermediates. Notably, the concurrent detection of n-butane and benzene revealed the coexistence of carbon-chain growth (coupling) and aromatization mechanisms. n-Butane likely originates from propyl radical coupling or alkyl fragment recombination, whereas the formation of benzene suggests cyclization or polymerization pathways of olefinic/alkyl intermediates at active catalytic sites. The complexity of this product spectrum underscores the simultaneous operation of multiple selective oxidation and olefin coupling channels in the catalytic system. These findings provide critical mechanistic insights for elucidating propane's oxidation pathways and optimizing catalytic performance through controlled manipulation of the competing reaction channels.

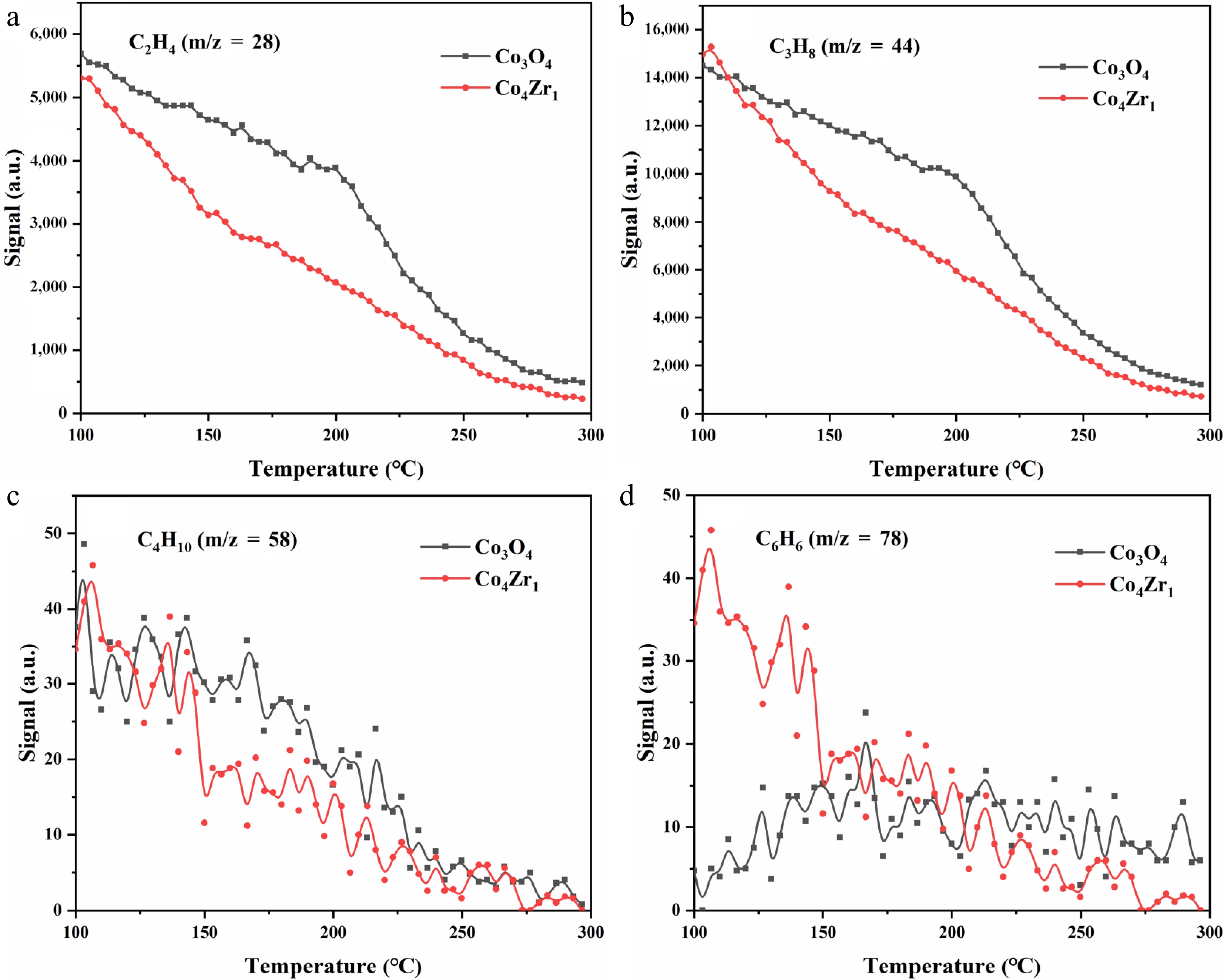

Figure 3 displays the temperature-programmed surface reaction (TPSR) profiles monitoring the evolution/consumption of hydrocarbon species (C2H4 [m/z = 28], C3H8 [m/z = 44], C4H10 [m/z = 58], and C6H6 [m/z = 78]) over Co3O4 and Co4Zr1 catalysts in the 100–300 °C range. All hydrocarbon signals exhibit progressive attenuation with increasing temperature, indicative of oxidative consumption at the catalysts' surfaces. Comparative analysis reveals accelerated signal decay rates for hydrocarbon species over Zr-doped Co4Zr1 compared with pristine Co3O4 (particularly evident in Fig. 3a, b). This demonstrates enhanced oxidation activity through the incorporation of Zr, exemplified by lower temperature thresholds for the conversion of ethylene and propane over Co4Zr1. For butane and benzene (Fig. 3c, d), despite signal fluctuations, Co4Zr1 maintains superior oxidative performance: butane oxidation diverges significantly above 200 °C, whereas benzene conversion shows marked differences below 150 °C. Notably, the substantially lower signal intensities of butane (C4H10) and benzene (C6H6) compared with those of ethylene and propane suggest their limited formation as minor byproducts rather than primary intermediates. This implies that higher-carbon species (C ≥ 4) represent secondary pathways with negligible contributions to the dominant reaction network and product distribution. The systematic increase in hydrocarbon oxidation performance across all monitored species confirms that Zr doping effectively optimizes the redox functionality of Co-based catalysts, likely through improved oxygen mobility and stabilized active sites.

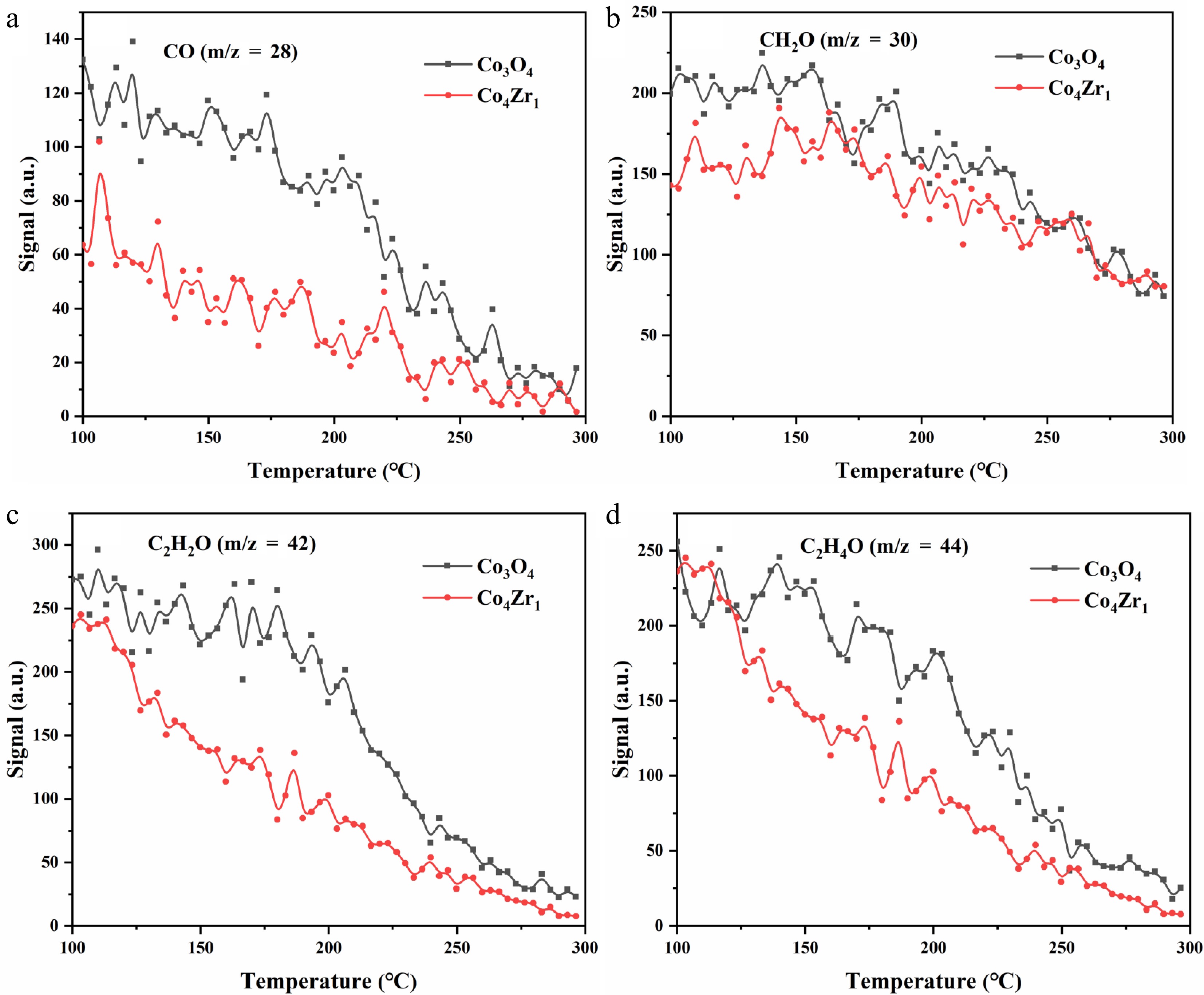

Figure 4 presents the TPSR profiles of oxygenated intermediates over Co3O4 and Co4Zr1 catalysts, including carbon monoxide (CO, m/z = 28; Fig. 4a), formaldehyde (CH2O, m/z = 30; Fig. 4b), ketene (C2H2O, m/z = 42; Fig. 4c), and acetaldehyde (C2H4O, m/z = 44; Fig. 4d). These oxygenated species represent critical intermediates in catalytic combustion of propane, and their oxidative transformation characteristics provide mechanistic insights into their reaction pathways and catalytic performance. The experimental results revealed progressive signal attenuation for all the oxygenated intermediates with increasing temperature (100–300 °C), demonstrating their sequential oxidative consumption on the catalysts' surfaces. Notably, compared with pristine Co3O4, Zr-doped Co4Zr1 exhibited superior oxidative activity across all the monitored species. Pronounced disparities emerge in the converstion of CO ( Fig. 4a) and acetaldehyde ( Fig. 4d), where Zr modification markedly accelerates their transformation to terminal oxidation products (CO2 and H2O). For ketene ( Fig. 4c), despite inherently weaker signals, Co4Zr1 maintains a distinct activity advantage above 150 °C, whereas acetaldehyde oxidation (Fig. 4d) shows consistently increased performance over the entire temperature range.

These observations collectively confirm that the incorporation of Zr significantly improves the catalytic combustion efficiency of Co-based catalysts toward oxygenated intermediates. This enhancement mitigates the accumulation of partial oxidation products and promotes their rapid conversion to fully oxidized species, thereby improving the overall oxidation efficiency.

Analysis of the mechanism of the catalytic reactions

-

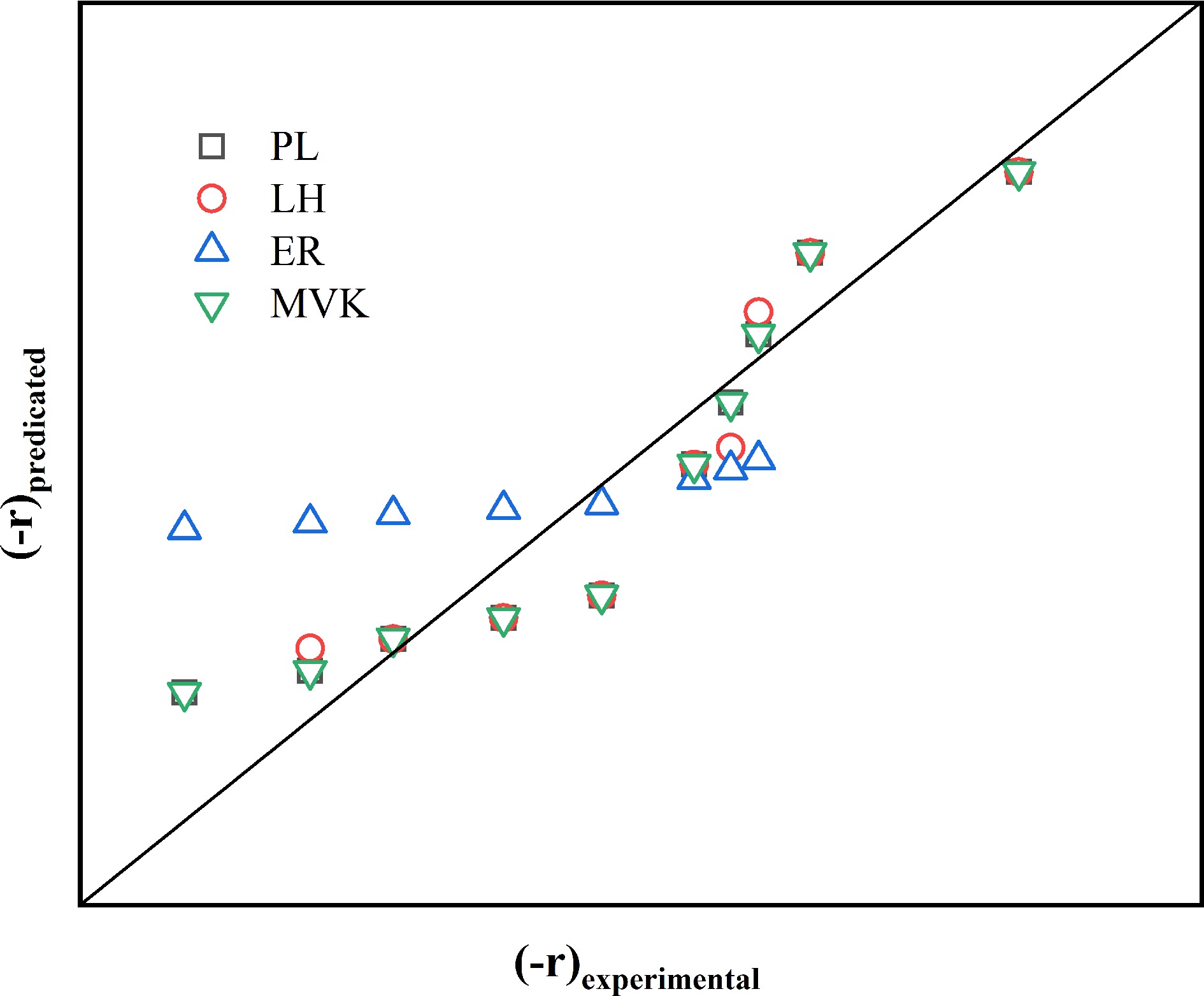

Figure 5 compares the experimental catalytic combustion rates of propane over the Co4Zr1 catalyst with predictions yielded by four classical kinetic models: the power law (PL) and the Langmuir–Hinshelwood (LH), Eley–Rideal (ER), and Mars–van Krevelen (MvK) models. The MvK model demonstrates better alignment with the experimental data across the tested conditions, effectively capturing key mechanistic steps, including surface adsorption, activation, and reaction pathways. In contrast, the ER model results in significant overestimations within specific conversion ranges or temperature regimes, whereas the LH model deviates at elevated temperatures (> 250 °C) and high conversion levels (> 70%). The PL model, which relies on oversimplified reaction order assumptions, shows limited accuracy throughout the investigated parameter space. This hierarchy of model performance aligns with theoretical calculations revealing that oxygen vacancy-containing facets exhibit the highest adsorption energies, which is consistent with the predominance of the MvK mechanism involving the participation of lattice oxygen in catalytic cycles.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the predicted and experimental values of the catalytic combustion reaction rate model of propane on Co4Zr1.

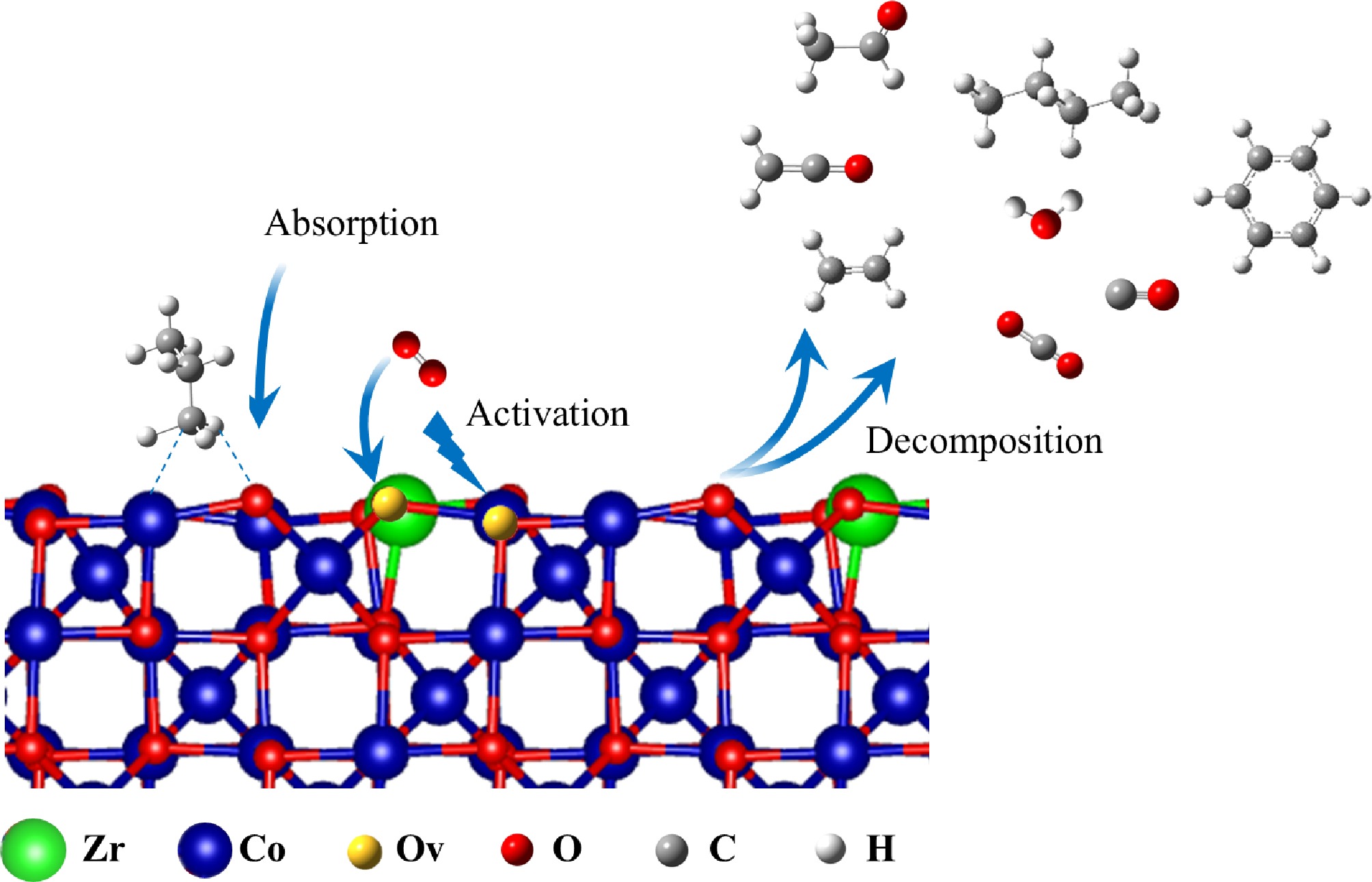

According to the experimental results from GC-MS and SVUV-PIMS, the reaction process for the catalytic combustion of propane on a Co4Zr1 catalyst is approximately as follows: Propane molecules adsorb on the catalyst's surface, where C-H bonds are activated and undergo initial cleavage or partial oxidation to form a CH2CH2CH3 (ads) intermediate (R3.1). This CH2CH2CH3 (ads) intermediate then reacts with the adjacent lattice oxygen (O2−) to produce CH2CHCH3 (ads), creating an oxygen vacancy (OV) in the process (R3.2). At higher temperatures, the resulting CH2CHCH3 (ads) is further and completely oxidized to carbon dioxide and water by highly active oxygen species on the catalyst's surface (such as oxygen adsorbed at the vacancies), followed by desorption of the products (R3.3). Subsequently, gas-phase O2 adsorbs onto the oxygen vacancies, dissociates to replenish the lattice oxygen, and simultaneously re-oxidizes the catalyst (R3.4).

$ {\mathrm{H}}_{3}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{g}\right)={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)+\mathrm{ }\mathrm{H}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)$ (R3.1) $ {\mathrm{CH}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)+{\mathrm{O}}^{2-}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)+\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)+{\rm O}_{\rm v} $ (R3.2) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)+\mathrm{ }9{\mathrm{O}}^{2-}=3{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{O}}_{2}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)+{3\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O} $ (R3.3) $\rm {\mathrm{O}}_{2}+{2O}_{v}={2\mathrm{O}}^{2-}$ (R3.4) Notably, the presence of propene was not detected in the SVUV-PIMS analysis. This is likely because propene remains adsorbed on the catalyst's surface and is rapidly oxidized. The primary pathway for the catalytic combustion of propane follows the MvK mechanism, involving adsorption on the CoxZry catalyst's surface and oxidation to carbon dioxide and water. However, as shown in Fig. 6, small amounts of intermediate products (including formaldehyde, ethylene, ketene, acetaldehyde, n-butane, and benzene) were still detected during the catalytic combustion process. This indicates the existence of multiple parallel reaction pathways within the system.

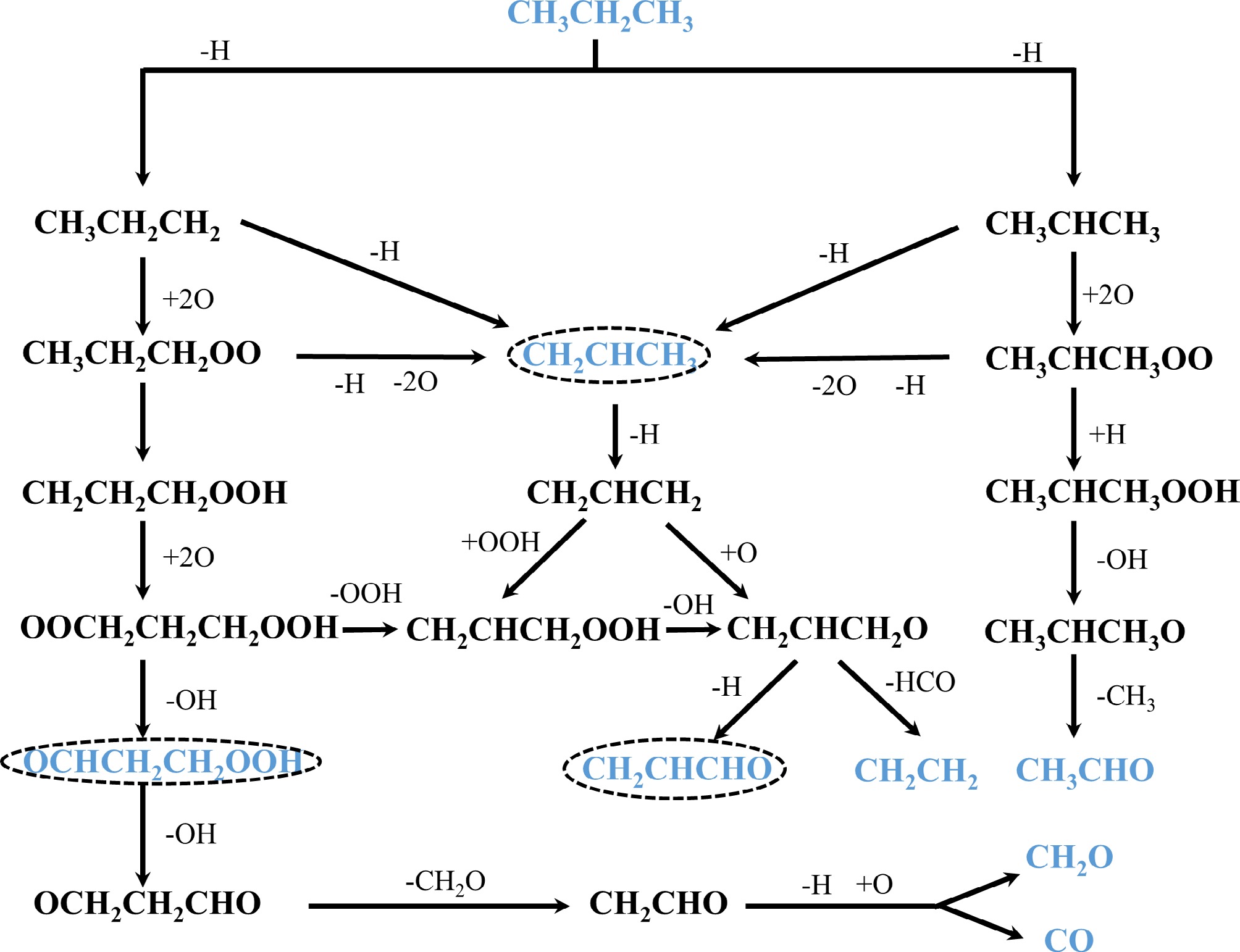

According to the Chemkin simulation of gas-phase combustion of propane under equivalent atmospheric conditions, the main pathway for low-temperature oxidation, as illustrated in Fig. 7, begins with propane undergoing a dehydrogenation reaction (-H) to lose a hydrogen atom, forming two types of propyl radicals: n-propyl (CH3CH2CH2) and isopropyl (CH3CHCH3) (R3.5 and R3.6). Concurrently, both propyl radicals can undergo further dehydrogenation to generate propene (R3.7 and R3.8). Following oxidation, the n-propyl and isopropyl radicals, respectively, form n-propylperoxy (CH3CH2CH2OO) and isopropylperoxy (CH3CHCH3OO) radicals (R3.9 and R3.10). Subsequently, these peroxy radicals can eliminate a hydroperoxyl radical to regenerate propene (R3.11 and R3.12). From here, the reaction pathways diverge. The CH3CH2CH2OO radical can isomerize into a CH2CH2CH2OOH radical (R3.13), which is then oxidized to an OOCH2CH2CH2OOH radical (R3.17). This species can then either lose a hydroxyl radical to form OCHCH2CH2OOH (R3.18) or lose a hydroperoxyl radical (OOH) to create a CH2CHCH2OOH radical (R3.19). The OCHCH2CH2OOH radical proceeds to lose another hydroxyl radical, forming an OCH2CH2CHO radical (R3.20), which is followed by the loss of a formaldehyde (CH2O) molecule to produce a CH2CHO radical (R3.21). This final radical undergoes oxidative dehydrogenation to yield formaldehyde and carbon monoxide (R3.22). In a parallel path, the CH3CHCH3OO radical, upon hydrogenation, forms a CH3CHCH3OOH radical (R3.14), which then produces acetaldehyde by losing a hydroxyl and a methyl radical (R3.15 and R3.16). On another pathway, propene itself can be dehydrogenated to an allyl radical (CH2CHCH2) (R3.23), which subsequently reacts with OOH to produce a CH2CH2CH2OOH radical (R3.24). This radical can then be oxidized (R3.25) or lose a hydroxyl radical (R3.26) to form a CH2CH2CH2O radical. Finally, this CH2CH2CH2O radical can either lose a hydrogen atom to form acrolein (CH2CHCHO) (R3.27) or lose a formyl radical (HCO) to form ethylene (R3.28).

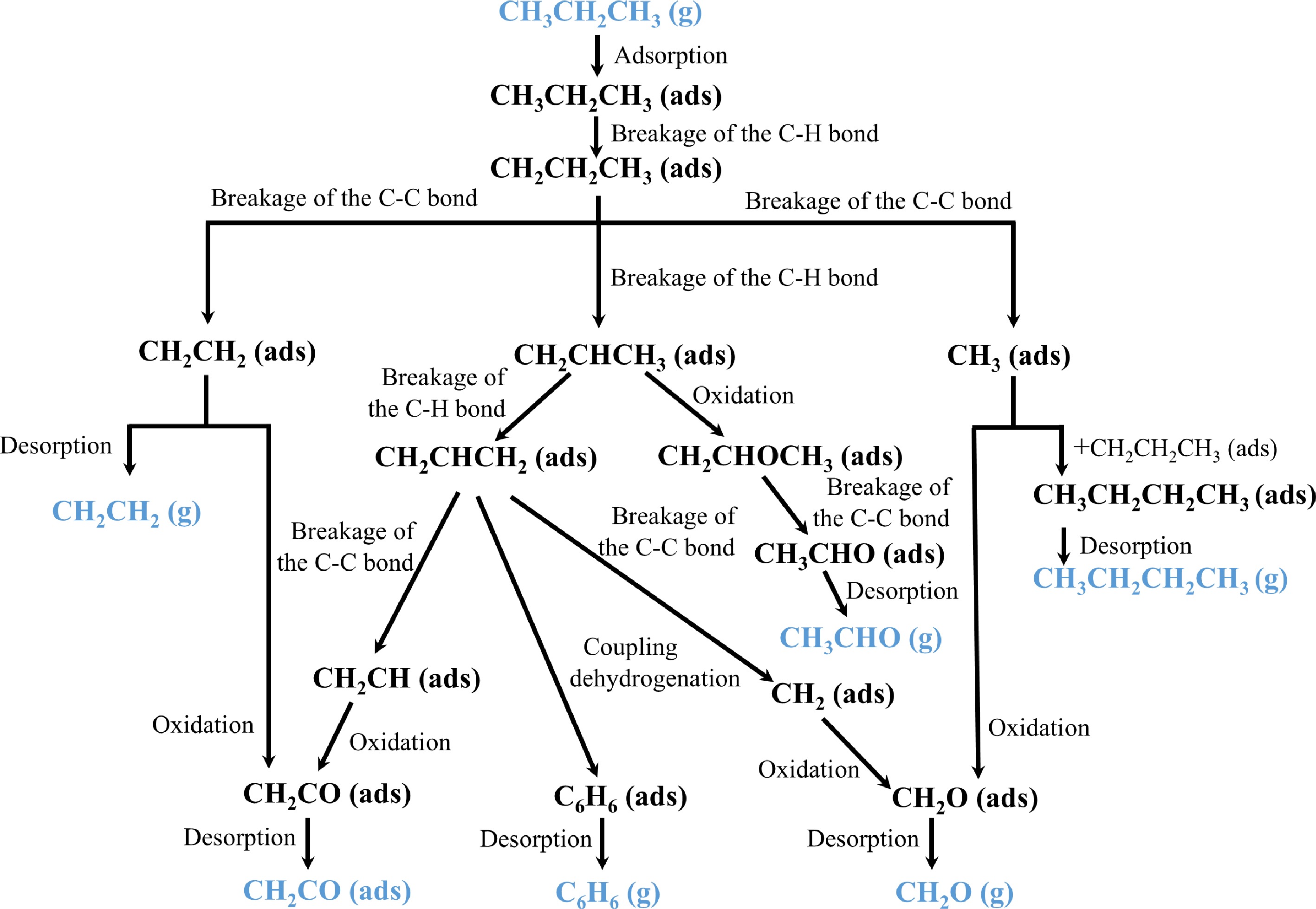

$ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}+\mathrm{H}/\mathrm{O}/\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}+{\mathrm{H}}_{2}/\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}/{\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}$ (R3.5) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}+\mathrm{H}/\mathrm{O}/\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}+{\mathrm{H}}_{2}/\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}/{\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O} $ (R3.6) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}+\mathrm{H} $ (R3.7) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}+\mathrm{H} $ (R3.8) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}+\mathrm{ }2\mathrm{O}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O} $ (R3.9) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}+\mathrm{ }2\mathrm{O}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O} $ (R3.10) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}+\mathrm{H}+2\mathrm{O} $ (R3.11) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}+\mathrm{H}+2\mathrm{O} $ (R3.12) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}$ (R3.13) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }+\mathrm{ }\mathrm{H}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H} $ (R3.14) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{O}+\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H} $ (R3.15) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{O}+{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3} $ (R3.16) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{ }+\mathrm{ }2\mathrm{O}=\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H} $ (R3.17) $ \mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}=\mathrm{O}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{ }+\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}$ (R3.18) $ \mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{ }+\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H} $ (R3.19) $ \mathrm{O}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}=\mathrm{O}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }+\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H} $ (R3.20) $ \mathrm{O}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{O}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }+{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O} $ (R3.21) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }+\mathrm{O}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }+\mathrm{C}\mathrm{O}+\mathrm{H} $ (R3.22) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}+\mathrm{H}$ (R3.23) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}+\mathrm{ }\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H} $ (R3.24) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}+\mathrm{ }\mathrm{O}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O} $ (R3.25) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }+\mathrm{O}\mathrm{H} $ (R3.26) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }+\mathrm{H} $ (R3.27) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}+\mathrm{H}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{O} $ (R3.28) Since the actual catalytic reaction temperature is below 300 °C, a condition under whichit is difficult for gas-phase combustion reactions to occur, and considering that numerous gas-phase intermediates were not detected in the SVUV-PIMS experiments, it can be inferred that these intermediate products are more likely generated during the conversion of propane on the catalyst's surface. A possible reaction pathway for this surface-mediated process is illustrated in Fig. 8. The mechanism begins with the adsorption of CH3CH2CH3 on the catalyst (R3.29). Serving as strong Lewis acid sites, Co3+ ions promote the heterolytic cleavage of a C-H bond in propane to form CH2CH2CH3 (ads) (R3.30). This adsorbed propyl species can then undergo C-C bond scission to yield CH2CH2 (ads) and CH3 (ads) (R3.31), with the resulting CH2CH2 (ads) desorbing to produce ethylene (R3.33). Concurrently, CH2CH2CH3 (ads) may undergo C-H bond cleavage to form CH2CHCH3 (ads) (R3.32), which can then undergo another C-H bond cleavage to form CH2CHCH2 (ads) (R3.34). The CH2CHCH3 (ads) species reacts with active oxygen in the catalyst to form CH2CHOCH3 (ads) (R3.35), which subsequently undergoes C-C bond cleavage to form CH3CHO (ads) before desorbing into the gas phase as acetaldehyde (R3.36, R3.37). In another pathway, the CH2CHCH2 (ads) species undergoes C-C bond scission to yield CH2CH (ads) and CH2 (ads) (R3.38). The CH2CH (ads) species reacts with active oxygen to form CH2CO (ads) (R3.39); alternatively, CH2CH2 (ads) can also be oxidized on the surface to form CH2CO (ads) (R3.40), which desorbs as ketene (R3.41). Similarly, CH2 (ads) and CH3 (ads) are further oxidized on the catalyst's surface to CH2O (ads) (R3.42, R3.43), which then desorbs into the gas phase as formaldehyde (R3.44). Notably, n-butane is formed through an addition reaction between a CH3 (ads) species and a CH2CH2CH3 (ads) species, producing CH3CH2CH2CH3 (ads), which then desorbs from the surface (R3.45, R3.46). Finally, the formation of benzene is attributed to the coupling and cyclization of CH2CHCH2 (ads) species, followed by successive C-H bond cleavages (R3.47, R3.48).

Figure 8.

The generation pathways of the main products of catalytic combustion of propane on the CoxZry catalyst.

$ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{g}\right)\mathrm{ }={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (R3.29) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)+\mathrm{H}\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (R3.30) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)+{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (R3.31) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)+\mathrm{H}\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (R3.32) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\left(\mathrm{g}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (R3.33) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)+\mathrm{H}\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (R3.34) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }+{\mathrm{O}}^{2-}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{O}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (R3.35) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{O}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }+{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (R3.36) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{g}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (R3.37) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }+{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (R3.38) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }+{\mathrm{O}}^{2-}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }+\mathrm{H}\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (R3.39) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }+{\mathrm{O}}^{2-}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }+2\mathrm{H}\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (R3.40) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{g}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (R3.41) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }+{\mathrm{O}}^{2-}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }$ (R3.42) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }+{\mathrm{O}}^{2-}={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }+\mathrm{H}\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (R3.43) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{O}\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{g}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }$ (R3.44) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }+{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }$ (R3.45) $ {\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }={\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{3}\left(\mathrm{g}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (R3.46) $ 2{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}{\mathrm{C}\mathrm{H}}_{2}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }={\mathrm{C}}_{6}{\mathrm{H}}_{6}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }+4\mathrm{H}\mathrm{ }\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (R3.47) $ {\mathrm{C}}_{6}{\mathrm{H}}_{6}\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}\right)\mathrm{ }={\mathrm{C}}_{6}{\mathrm{H}}_{6}\left(\mathrm{g}\right)\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ }\mathrm{ } $ (R3.48) The experimental and theoretical simulation results indicate that the catalytic combustion of propane on the Co4Zr1 catalyst primarily follows the MvK mechanism. This process involves the adsorption of propane and activation of its C-H bonds at the active sites of Co (Co3+), followed by progressive oxidation to CO2 and H2O through a reaction with lattice oxygen, while the resulting oxygen vacancies (OV) are replenished and regenerated by gas-phase O2. Although trace amounts of intermediate products (such as formaldehyde, ethylene, ketene, acetaldehyde, butane, and benzene) were detected during the reaction, their concentrations were extremely low, and no accumulation of propene was observed, indicating that these intermediates exist only transiently on the surface and are rapidly oxidized further. The origin of these trace intermediates is likely attributable mainly to surface reaction processes, where adsorbed species like CH2CH2CH3 (ads), CH2CH2 (ads), or CH3 (ads) undergo oxidation or addition reactions on the catalyst's surface before desorbing. While gas-phase radical side reactions could also contribute to the production of these intermediates, their contribution is considered minimal due to the low catalytic combustion temperature (below 300 °C) and the very low detected concentrations of the byproducts. In summary, the Co4Zr1 catalyst demonstrates extremely high efficiency for propane oxidation. The primary reaction pathway is dominated by the surface MvK mechanism, and the presence of trace intermediates merely reflects minor competitive pathways that do not compromise the overall high selectivity towards deep oxidation.

-

In this study, zirconium-doped cobalt-based catalysts (CoxZry) were successfully synthesized and shown to have superior performance in propane combustion compared with pure Co3O4, with the Co4Zr1 composition being particularly effective. The incorporation of Zr was found to enhance the formation of oxygen vacancies and improve the catalyst's redox capacity, which promotes the efficient mobility of lattice oxygen and facilitates redox cycling consistent with the MvK mechanism. A key contribution of this work was the use of SVUV-PIMS, which enabled the real-time detection of critical transient intermediates, including ethylene, formaldehyde, ketene, and acetaldehyde. These insights confirmed that while the dominant reaction pathway involves the deep oxidation of propane to CO2 and H2O on Co3+ active sites, multiple parallel pathways exist that generate trace amounts of byproducts. However, these intermediates exist only transiently and are rapidly oxidized, without affecting the high overall selectivity of the process. The contribution of gas-phase reactions was determined to be minimal under the low-temperature conditions investigated. Ultimately, these findings underscore the potential of Zr–Co bimetallic oxides as cost-effective non-noble metal catalysts for low-temperature VOC abatement and provide a deeper mechanistic understanding to guide the future design of highly efficient catalytic converters.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52476133), Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. 2308085J20), and the Students' Innovation and Entrepreneurship Foundation of University of Science and Technology of China (No. XY2024C004).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: investigation: He C, Lou H, Sun L, Xu W, Zhang L; writing - original draft, data curation, methodology: He C; formal analysis: Lou H; resources, writing - review & editing, funding acquisition: Zhang L. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

He C, Lou H, Sun L, Xu W, Zhang L. 2025. Study of the catalytic combustion of propane on zirconium-doped Co3O4 catalyst based on synchrotron radiation. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 50: e016 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0016

Study of the catalytic combustion of propane on zirconium-doped Co3O4 catalyst based on synchrotron radiation

- Received: 17 April 2025

- Revised: 12 June 2025

- Accepted: 17 July 2025

- Published online: 28 September 2025

Abstract: Catalytic combustion is a key technology for mitigating harmful volatile organic compounds (VOCs) like propane, but the high cost of noble metal catalysts necessitates the development of effective non-noble metal alternatives. This study investigates zirconium (Zr)-doped cobalt oxide (CoxZry) catalysts, synthesized via a sol–gel method, for propane combustion. By employing advanced analytical techniques, including in situ synchrotron radiation vacuum ultraviolet photoionization mass spectrometry (SVUV-PIMS) and temperature-programmed surface reaction (TPSR) experiments, the study provides a molecular-level dissection of the reaction mechanism. Real-time detection identified critical transient intermediates such as ethylene, formaldehyde, ketene, and acetaldehyde. The results demonstrate that Zr doping significantly enhances the catalyst's redox capacity and the density of oxygen vacancies, leading to superior oxidative activity in the Co4Zr1 catalyst compared with pure Co3O4. Kinetic analysis and experimental data confirm that the reaction primarily follows the Mars–van Krevelen (MvK) mechanism, where lattice oxygen participates in oxidation and gaseous O2 regenerates the active sites. The findings highlight that Zr-doped cobalt oxides are promising, cost-effective catalysts for efficient VOC abatement and provide theoretical insights for the rational design of advanced non-noble metal catalysts.