-

As the most common and popular fruit, apples are consumed fresh or in diverse product formats all over the world. However, several issues restrict the high-quality and safe production of apple products. Before further processing, raw apples need to be washed, waxed, and cooled to reduce the agricultural debris, microbial load, and pesticides that either cause safety risks or food losses. However, it does not involve any 'kill step' that would sufficiently eliminate microorganisms of concern, especially for minimally processed apple products[1]. Therefore, residual microorganisms can still survive or grow on the fruit surface, posing high risks. For instance, statistics indicated that recalls of fresh-cut apples contaminated by Listeria monocytogenes occurred almost every year from 2012 to 2020[2]. The losses during post-harvest in developed countries reached as much as 25% of the total harvest. In developing countries, these losses were even more significant, ranging from 50 to 60%. Moreover, more than 90 species of fungi have been identified as the causative agents of apple rot during storage[3,4]. Apple postharvest losses are primarily caused by spoilage microorganisms, including Erwinia amylovora, Pseudomonas syringae, Botrytis cinerea, and Penicillium expansum. These pathogens induce diseases by latent infections[5]. Further, partial decay caused by either biotic or abiotic stressors may accelerate the rate of enzymatic browning of the apple skin or flesh, greatly reducing the overall acceptance by consumers[6]. The development of an advanced decontamination approach would be a suitable way to improve the safety and quality of fresh apples.

Although chemical disinfectants are commonly used to sanitize fresh produce, the frequently used chlorine-based sanitizers are prone to reacting with organic compounds, producing carcinogenic byproducts such as trihalomethanes[7]. Studies revealed that current sanitation measures may only achieve ~1 log CFU/apple reduction average against Listeria monocytogenes on apples[8]. In another study, treating fresh apples with 65 °C hot water reduced the natural flora on the apple surface by 2 to 3 log CFU/g, however, it is regarded as a permanent compromise, as higher water temperature would do undesired damage to apples[9]. Some researchers also studied ozone water for fresh-cut apple decontamination, treating apples with aqueous bubbling ozone water for 3 min at 25 °C reduces the count of E. coli O157:H7 by 3.7 log CFU/g.[10]. Yet, the strong oxidizing nature of ozone can degrade nutrients such as vitamin C. Additionally, various physical treatments such as UV light, ultrasound, cold plasma, etc., have also been employed to improve fresh produce sanitation.[11,12]

Micro-nanobubble (MNB) is a green technology that has been successfully adopted by water treatment, agricultural production, etc. MNBs are a mixture of MBs and NBs, with MBs referring to bubbles with diameters ranging from 1 to 100 μm and NBs for bubbles, with diameters of < 1 μm[13]. Compared to regular bubbles, micro-nanobubbles in water exhibit excellent anti-aggregation stability, high specific surface area, and increased gas solubility[14]. Increasing amounts of research have focused on the application of MNB in the food industry. Particularly, MNB may have the potential to remove microorganisms from the food surface during the washing process. When combined with 100 mg/L sodium hypochlorite, microbubble-assisted washing was carried out. It led to a reduction of 3.3 ± 0.1, 0.8 ± 0.5, and 1.0 ± 0.4 log CFU/g against E. coli O157:H7 on the surfaces of grape tomatoes, blueberries, and baby spinach, respectively[15]. For 5 min, when sweet basil and Thai mint were washed with MNB in combination with sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) and acidified electrolyzed oxidizer (AEO), it led to a significant reduction in the levels of Salmonella Typhimurium and Escherichia coli, achieving 2−3 log reductions for both of them[16]. Micro-nanobubbles may swap the bacterial cells through mechanic shear forces, facilitating bacterial inactivation by sanitizers. It has been reported that micro-nanobubbles may also generate free radicals at the moment of bubble rupture, promoting the degradation of organic matter[17]. Additionally, micro-nanobubbles can degrade pesticide residues, thereby reducing the impact of pesticide residues on human health during fruit and vegetable processing[18]. As reported by Ikeura et al.[19], washing persimmon leaves with bubbling ozone microbubbles for 15 min removed the residual fenitrothion by 60%, greatly reducing the chemical hazards. Epsilon-poly-lysine (ε-PL) is a natural polymer consisting of 25−30 lysines with peptide bonds between the α-carboxyl and ε-amino groups, which was usually produced by aerobic fermentation of Streptomyces albulus[20]. As a natural antimicrobial peptide, ε-PL was widely applied to inhibit the growth of yeast, fungi, and bacteria[21,22]. The usage of ε-PL as a food additive has been generally recognized as safe (GRAS) in the United States for cheese, rice, soft drinks, coffee, and so on[23], and has also been included in the list of food additives in China according to its national standard (GB 2760-2014).

In this research, we evaluate the effectiveness of MNB-assisted washing with additional ε-PL as a novel decontamination approach for fresh apples. As far as we know, no research has investigated the ability of MNB–assisted washing to decontaminate fresh apples. Especially research with the aid of macromolecules such as ε-PL. Decontaminations of representative pathogenic, spoilage microorganisms, and residual pesticides on apple surfaces were assessed using artificially inoculated models. The impact of treatment on apple quality deterioration during storage was also studied. Findings may advance the application of MNB technologies in the food industry, particularly for the postharvest sanitation of fresh produce.

-

Tryptic soy broth with yeast extract (TSBYE), yeast extract peptone dextrose medium (YPD), and WL nutrient medium (WLN) were purchased from Qingdao Hope Bio-Technology Co., Ltd. (Qingdao, China). Epsilon-poly-lysine (ε-PL) and plate count agar (PCA) were purchased from Shanghai Titan Scientific Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and trichlorfon, were from Shanghai Huxi Industrial Co., (Shanghai, China). The pesticide residue detection kit was purchased from Guangzhou Ruisen Biotechnology Co., (Guangzhou, China). Fresh Fuji apples with no defects were purchased from Wu Mart Supermarket in Beijing (China).

Generation and characteristics of MNBs

-

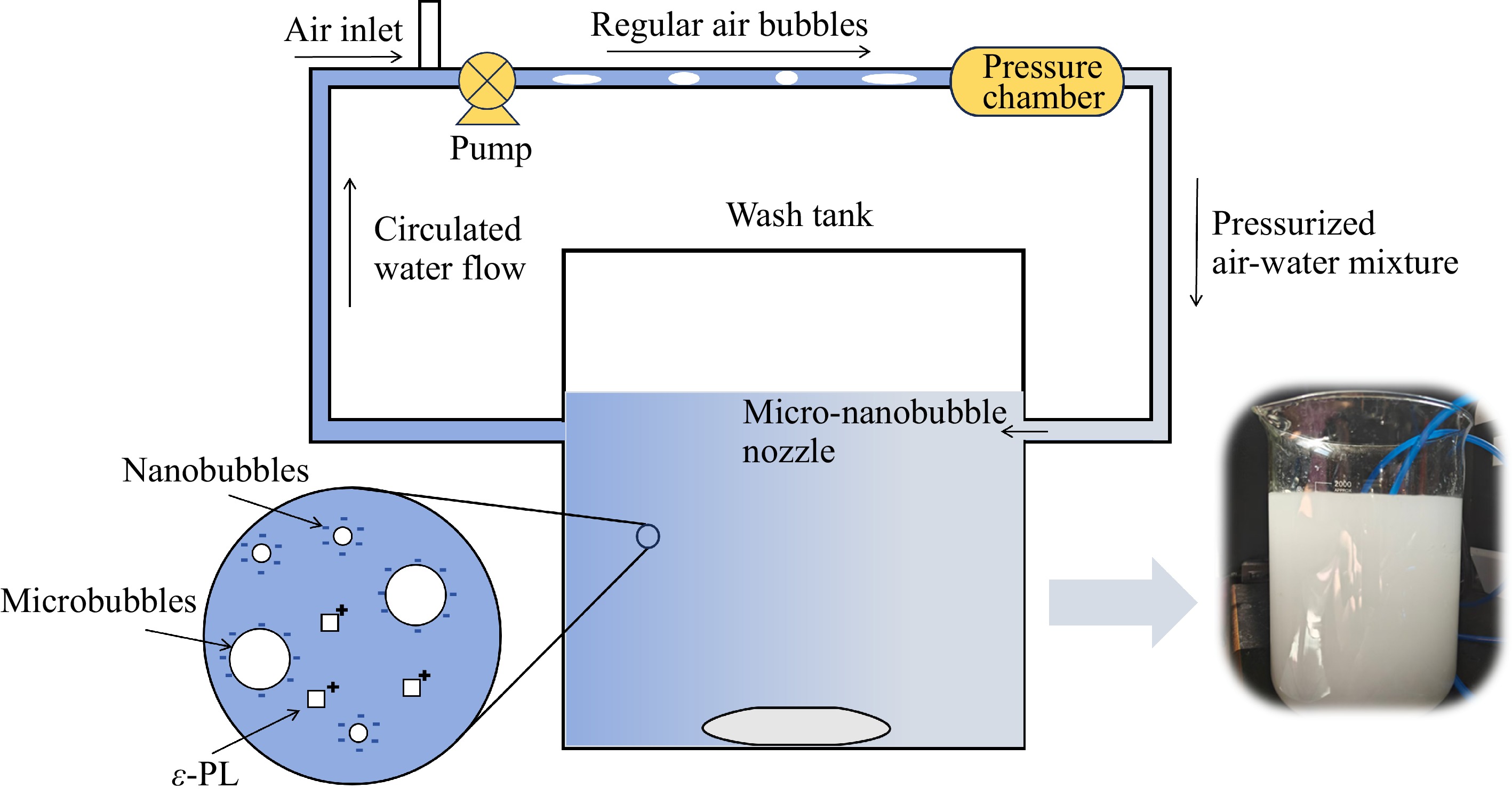

Air micro-nanobubbles were produced by compression-decompression method using an L-1500 micro-nanobubble generator (Xingheng Technology Co., Shanghai, China). During the testing, the air inlet was regulated to a flow rate of 30 mL/min, and the pressure was maintained at 0.5 MPa. Under these specified conditions, the micro-nanobubble generator was operated for at least 2 min to obtain a steady status milky circulating water before each test. The set-up for MNBs is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Micro-nanobubble recirculation fresh produce washing set-up along with the milky physical image of air micro-nanobubbles.

For the micro-nanobubble characterization, the particle size and distribution in the micro- or nano-range and the zeta potential were measured with different methods, with samples taken after 10 min continuous operation of the MNB generator. Microbubbles were real-time detected by a focused beam reflectance measurement (FBRM G400, Mettler Toledo, Switzerland) throughout the process[24]. The laser operates in a circular trajectory along the inner surface of the cylindrical probe at a velocity of 2 m/s, enabling it to accurately and promptly assess the real-time conditions of the bubbles.

For the nano-sized bubbles, each 1 mL sample was subjected to a Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer (NS300, Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Malvern, UK). Meanwhile, the sample was also subjected to the capillary electrode for measuring the zeta potential (ZP) using a Zetasizer (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern Panalytical Ltd., Malvern, UK). The Smoluchowski model was employed to analyze the zeta potential. The pH value of the sample was measured by a pH meter (FE28, Mettler Toledo Technology Co., China).

Decontamination of pathogenic and spoilage microorganisms on apple

Sample preparation

-

Prior to use, the apples were washed with tap water to reduce dust and soil debris. Apple peels with dimensions of 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm, and thickness of 1−2 mm were obtained by gently slicing using a stainless-steel razor. These peels were further rinsed with distilled water, sterilized under UVC light for 15 min to remove indigenous microorganisms, and then used as testing samples for decontamination experiments within a short time.

Microbial culturing and inoculation

-

A strain of Listeria monocytogenes (CICC 25021) was obtained from the China Center of Industrial Culture Collection (Beijing, China). The day before the experiment, the bacteria strain was inoculated in 5 mL TSBYE and cultured for 20 h at 37 °C overnight to reach a final population of ~109 CFU/mL. During the testing, the bacterial solution was centrifuged and re-suspended with PBS. Afterward, each 50 μL bacterial suspension was spot inoculated on the prepared samples, then air dried in a biosafety cabinet for 60 min before testing.

For Pichia kudriavzevii, a strain was obtained from Dr. Guoliang Yan's lab at China Agricultural University, originally isolated from fresh grapes. Pichia kudriavzevii was cultured in the YPD at 25 °C for 24 h. Similarly, the yeast suspension was obtained by centrifuging the culture and re-suspending it with PBS. Each 50 μL was spot inoculated on the prepared apple peel sample, then air-dried in a biosafety cabinet for 45 min before testing.

MNB assisted washing

-

The decontamination experiment was designed to use four different treatments, i.e., water wash (Water), air MNB wash (MNB), ε-PL wash (ε-PL), and air MNB wash combined with ε-PL (MNB/ε-PL). Two levels of ε-PL concentrations at 10 and 250 mg/L were selected for testing. Samples without treatment were used as control (Control). In each experiment, three pieces of apple peels were washed inside a beaker with 1.4 L circulated MNB water, samples floated and moved freely while generally immersed in the wash water. The duration of the treatment was fixed to 5 min, after which samples were immediately transferred by sterilized tweezers into sealed polyethylene (PE) bags with 10 mL PBS buffer, with three pieces per bag. Following that, samples were homogenized by a stomacher (HX-4, Huxi Industry Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) for 2 min to disperse the microorganism cells. Finally, each 1 mL of supernatant was serially diluted with PBS for enumeration. For Listeria, medium plates were cultured at 37 °C for 48 h; Pichia kudriavzevii were cultured at 25 °C for 3 d, before the enumeration.

Decontamination of trichlorfon on apple

-

For the decontamination of trichlorfon, each 20 μL trichlorfon solution (4 ng/L) was spot inoculated on the surface of apple peel samples obtained in the same method as the previous section. Afterward, samples were air-dried for 1 h until there was no visible liquid on the surface. The decontamination of trichlorfon was performed with the same treatments as the microbial experiment, except only 10 mg/L ε-PL was used. All the groups were washed for 5 min and then homogenized in a sterile bag with 5 mL PBS for 150 s, the supernatant was obtained for analyzing residual trichlorfon content.

The determination of trichlorfon was performed by the enzyme inhibition method, which is based on the relationship between the inhibition rate (Eq. [1]) and the absolute concentration of phosphorous pesticides[25]. The organic phosphate in pesticides can inhibit cholinesterase, preventing its catalysis of neurotransmitter metabolite analogs and generating products reacting with color-developing agents, resulting in a fluorescence change[26]. Before the sample measurements, a standard curve was obtained with the trichlorfon concentration range of 0.5 to 5 ng/L. During the testing, each 2.5 mL supernatant from the homogenized apple peel solution, 100 μL of enzyme solution, and 100 μL of color-developing agent were added into a cuvette and incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. Afterward, an additional 100 μL of substrate solution was added to initialize the reaction. The initial absorbance and the absorbance, after 3 min were measured at 412 nm using the UV-visible spectrophotometer (Shanghai Metash Instruments Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China) for calculating the pesticide removal rate, was calculated based on Eq. (2).

$ \rm The\;inhibition\;rate=\dfrac{[(cf-ci)-(sf-si)]}{(cf-ci)}\times 100{\text{%}} $ (1) where, cf represents the final absorbance of the control group; ci represents the initial absorbance of the control group; sf represents the final absorbance of the sample group; si represents the initial absorbance of the sample group.

${\begin{split}&\rm The\; pesticide\; removal =\\& \rm \dfrac{Concentration \;of\; the\; pesticide \;controlled - Concentration \;of \;the \;pesticide\; sample}{ Concentration\; of\; the \;pesticide\; controlled}\end{split}}$ (2) Quality changes in apples following decontaminations

MNB washing and sampling method

-

For quality assessment, Fuji apples of approximately the same size, without defects were selected to use. To simulate the real scenario, whole apples were disinfected by being completely submerged in 5 L wash water, all other parameters for micro-nanobubbles generation remained consistent as per the previous section. Samples treated by Water, MNB, ε-PL, and MNB/ε-PL were compared with the control, the concentration of ε-PL used in this part of the experiment was 10 mg/L. After washing, apples were air-dried for 60 min and stored at room temperature in a food-grade lab environment. Quality indicators were analyzed on day 0, day 10, and day 20.

Indigenous microbial count

-

Treated apple samples were initially placed in sterile sample bags containing 20 mL of sterilized PBS. The samples were gently and thoroughly hand-swabbed for 5 min to recover the attached microorganisms on the surface. Afterward, 100 μL of the obtained microbial suspension was serially diluted by PBS, spread on PCA, and incubated at 37 °C for 2 d for microbial enumeration.

Color

-

The color of apple samples was measured by a NR60CP colorimeter (Guangdong Threenh Technology Co., Guangdong, China). Measurements were conducted on two random spots consistently from the equatorial plane region of each apple. The color parameters, L*, a*, and b*, were recorded and the Browning Index was calculated following Eqs (3) and (4) below.

$ \mathrm{B}\mathrm{I}=\frac{100\left(\mathrm{x}-0.31\right)}{0.172} $ (3) where:

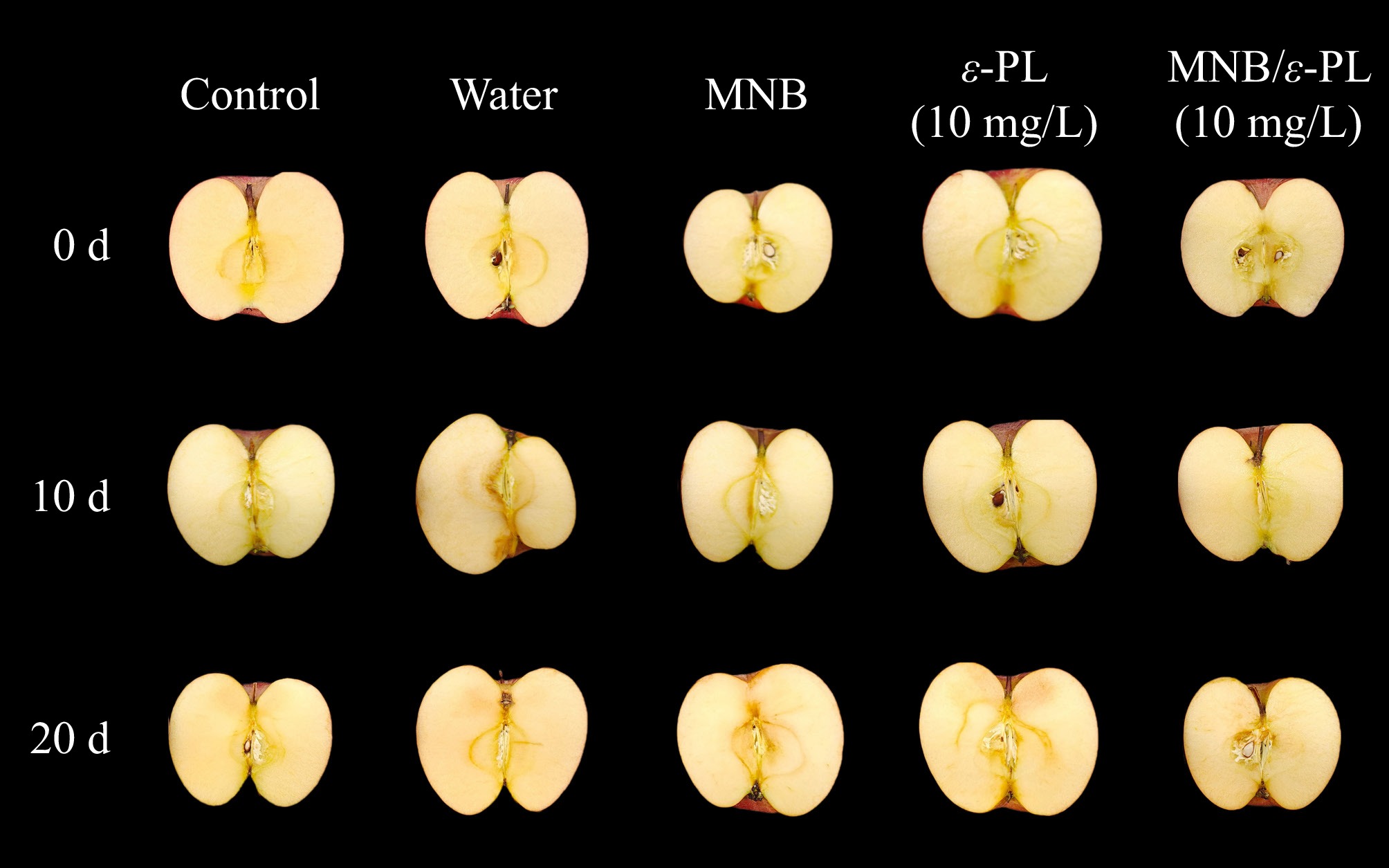

$ \mathrm{x}=\frac{\left(\mathrm{a}\mathrm{*}+1.75\mathrm{L}\mathrm{*}\right)}{(5.646\mathrm{L}\mathrm{*}+\mathrm{a}\mathrm{*}-3.012\mathrm{b}\mathrm{*})} $ (4) Meanwhile, the color changes of apple flesh were also evaluated by visual observation of the cut halves, which were recorded by a digital camera with a constant setting.

Hardness

-

The hardness of the treated apples was measured by a GYJ hardness tester (Weidu Electronics Co., Zhejiang, China) using a fruit testing probe with a diameter of 11 mm. The treated apples were placed horizontally under the probe and were penetrated at two random spots from the equatorial plane until a distance of 7 mm. For each group, triplicated samples were measured, and the hardness of the apple was expressed using the average of peak force values (N).

Statistical analysis

-

All experiments were repeated at least three times and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Differences between groups were analyzed using one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan's post hoc test for multiple comparisons in SPSS Statistics 26.0 (IBM Corporation, NY, USA), with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

-

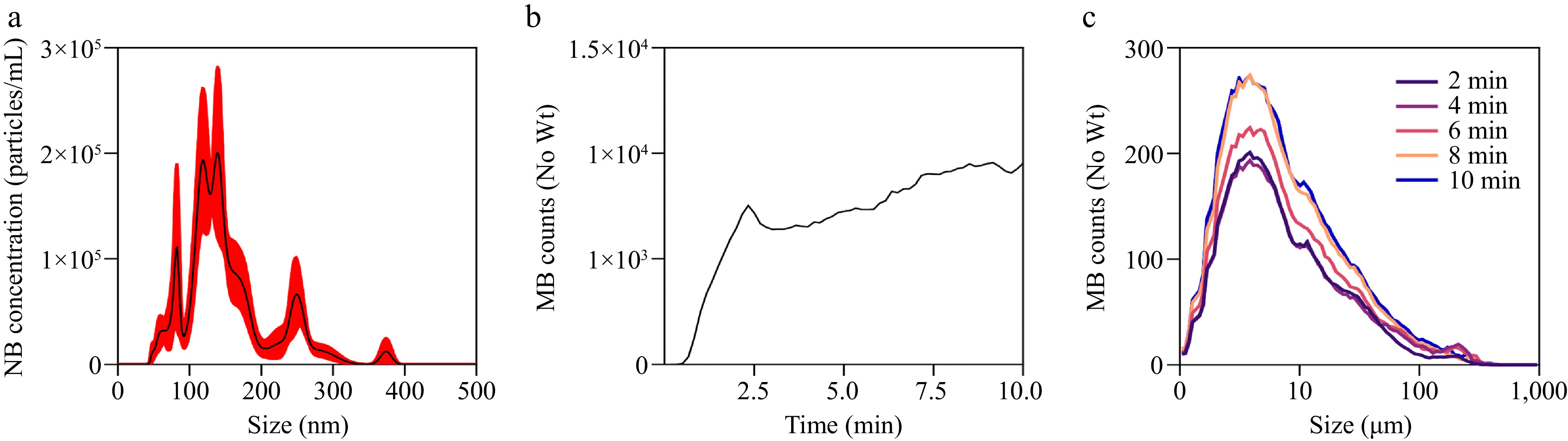

Results from NTA revealed (Fig. 2a) that the particle size of the air nanobubbles predominantly fell within the range of 100−200 nm, with an average particle size of 157.8 ± 3.8 nm. The concentration of nanobubbles reached 1.66 × 107 particles/mL. Comparable results were reported by Ma et al.[26], in which an average particle size of 146.9 ± 19.7 nm and a particle concentration of 5.31 × 107 particles/mL for air nanobubble were observed following a 60-min bubble generation. As shown in Fig. 2b, c, microbubble size measured at two-minute intervals from 2 to 10 min, generally fell into the range of 1−10 μm, which also aligns with the previous reports[25]. The research employed a similar compression-decompression method for micro-nanobubbles generation and demonstrated that the number of bubbles increased rapidly within the initial 2.5 min, reaching an equilibrium state. This observation is corroborated by visual assessments of the bubble generation with the development of milky and turbid wash water. Although the percentage of microbubbles below 10 μm increases over time, the overall number of bubbles remains relatively stable during the equilibrium stage.

Figure 2.

Characteristics of air micro-nanobubble. (a) Nanobubble number-size of air MNB. (b) Microbubble number of air MNB affected by time. (c) Microbubble number-size curves of air MNB affected by time ( 'No Wt' means that the counts of bubbles did not consider the weight).

Table 1 shows that air MNB (pH 7.29 ± 0.13) exhibited a negative zeta potential value, approximately −17 mV, which aligns with findings from others[27,28]. Comparatively, ZP values of ε-PL were positive and increased with concentration[29]. The incorporation of ε-PL into the MNB system results in a reversal of the bubble system's zeta potential, with values of approximately 20 mV. Additionally, the pH is maintained at a consistent value of around 5. It was well recognized that microbubbles are negatively charged, similar research found that adding positively charged metal ions, such as aluminum ions, results in a reversal in the zeta potential of the bubbles from a negative to a positive value[30]. It is particularly noteworthy that the addition of 10 mg/L ε-PL resulted in a higher zeta potential value exceeding ε-PL or the air MNB alone. These observations suggested that the developed MNB-assisted washing system is generally stable, with positive surface charges that are opposite to the common bacteria or yeast[31].

Table 1. The ZP and pH of different treatment groups.

Treatment MNB ε-PL (10 mg/L) MNB/ε-PL (10 mg/L) ε-PL (250 mg/L) MNB/ε-PL (250 mg/L) Zeta potential (mV) −17.53 ±1.68 13.38 ± 3.80 22.50 ± 5.50 26.27 ± 3.29 20.27 ± 1.62 pH 7.29 ± 0.13 6.13 ± 0.16 4.93 ± 0.03 6.57 ± 0.14 5.09 ± 0.04 Effect of micro-nanobubbles combined with ε-PL on microbial reduction

-

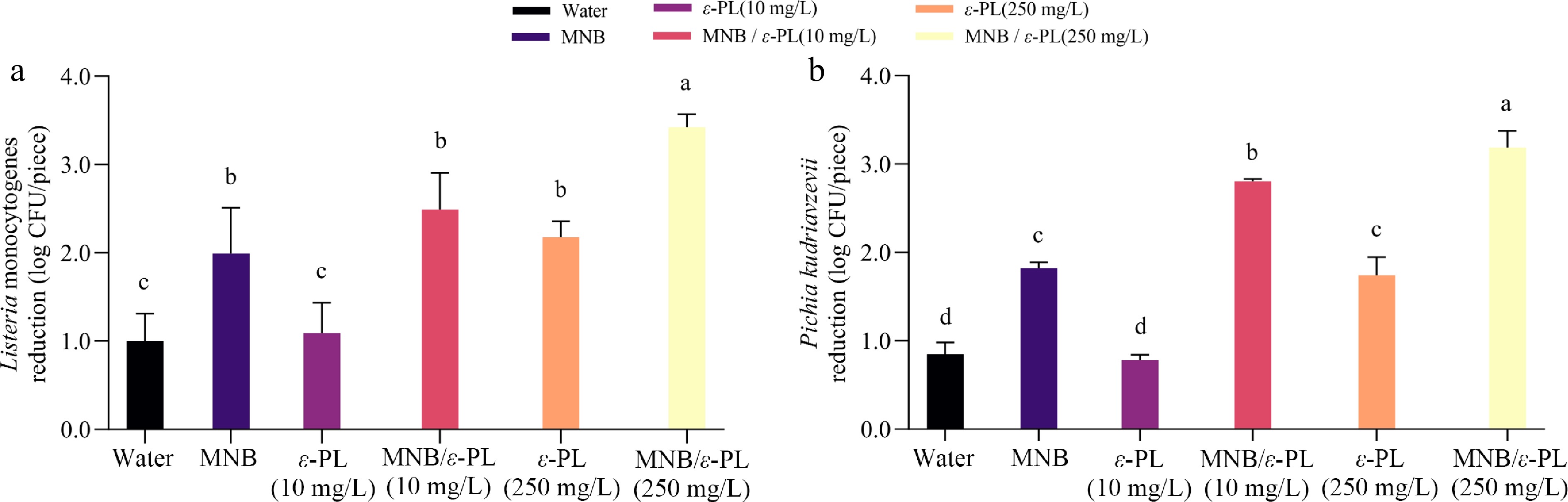

As shown in Fig. 3, the initial counts of Listeria monocytogenes and Pichia kudriavzevii on apples were 5.83 and 4.58 log CFU/piece respectively. Air MNB significantly reduced Listeria monocytogenes from the apples' surface. In agreement with this result, Singh et al. observed a 2.2 log reduction in Listeria monocytogenes after immersing the inoculated apple in air MNB solution for 2 min[32]. For ε-PL, at 10 mg/L, it posed a comparable effect as water wash. The 250 mg/L ε-PL, however, resulted in significantly higher (p < 0.05) removal of Listeria monocytogenes possibly due to the improved antimicrobial ability of ε-PL itself, and also the neutralization of negative charges on the surface of Listeria cells, thereby quickly disrupting the cell membrane[27]. In terms of combined treatment, MNB/ε-PL (10 mg/L) reduced the number of Listeria by 2.49 log, while MNB/ε-PL (250 mg/L) reduced the number by as much as 3.43 log (Fig. 3a). Compared to water or ε-PL alone, MNB-assisted washing significantly increased (p < 0.05) the bacterial reductions by 1–1.5 log. Previous studies found that microbubble-assisted washing with 100 mg/L sodium hypochlorite had no improvement on E. coli O157:H7 detachment from grape tomatoes, blueberries, and baby spinach[15]. The discrepancy in results in the present work compared to previous reports might be tied to the different surface properties of apples, allowing weak adhesion of microorganisms[33]. It is also possible that the overall positively charged MNB wash water tends to easily bind to negatively charged bacterial cells, expelling them from the produce surface[34].

Figure 3.

Effect of MNB-assisted washing with ε-PL on microbial reduction against (a) Listeria monocytogenes, and (b) Pichia kudriavzevii. Difference analysis p < 0.05.

The reduction in Pichia kudriavzevii after treatments followed quite a similar pattern (Fig. 3b). Air MNB significantly reduced the yeast cells compared to the control (p < 0.05). ε-PL of 250 mg/L reduced yeast, which aligns with existing research findings that 600 mg/L of ε-PL could effectively inhibit the mycelial growth of P. expansum in apples[35], with that treatment apples showing much lower decay incidence and lesion diameter. Although no effect was found for 10 mg/L ε-PL, again, the infusion of MNB significantly enhanced the individual treatments. In one study, it was observed that significant mold and yeast reduction on Roselle microgreens seeds were induced when applying microbubbles together with 5% H2O2, reaching ~2 log CFU/g reduction[36]. Our results demonstrated that MNB/ε-PL (250 mg/L) led to the highest removal rate of Pichia kudriavzevii of 3.19 log reduction. The decontamination results of both Listeria monocytogenes and Pichia kudriavzevii are demonstrated good compatibility between MNB and ε-PL, although only additive effects were observed. The advantages of combined treatment could be ascribed to the high specific volume area of MNB, thus increasing the interaction between ε-PL and microorganism[14]. Another possible reason might be the alternation of stability of MNB by ε-PL's positive charge. A study by Chang et al.[37] revealed that high-concentration electrolyte solutions promote the dissolution of surface nanobubbles, which may release more energy during accelerated collapse, improving the cell removal rates. In additional, MNB may provide high attachment force and accelerate the removal of microbial cells[38]. Indeed, although the interactions between MNB and ε-PL should have occurred as showed by the zeta potential variations, their cumulative effects on microbial reductions seemed limited and thus still need further investigations. Comparatively, the combination of aerosolized/spray-formulated curcumin with UV-A irradiation reduced initial loads of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Listeria innocua from 6 log CFU/cm² to approximately 3 log CFU/cm² on spinach, lettuce, and tomato surfaces[11]. As reported in a comparative study, 3-min ozonation at bubbling ozone water reduced E. coli O157:H7 contamination on fresh apples by 3.7 log CFU/g[10]. There are also cold plasma treatments on fresh-cut apples, with optimal power (40–80 W, 10 min) and treatment time (5–20 min, 50 W), but only with 1.27 log CFU/g reduction of total aerobic microbial bacteria[39]. In this case, our results demonstrated generally comparable antimicrobial capacity as other non-thermal processing.

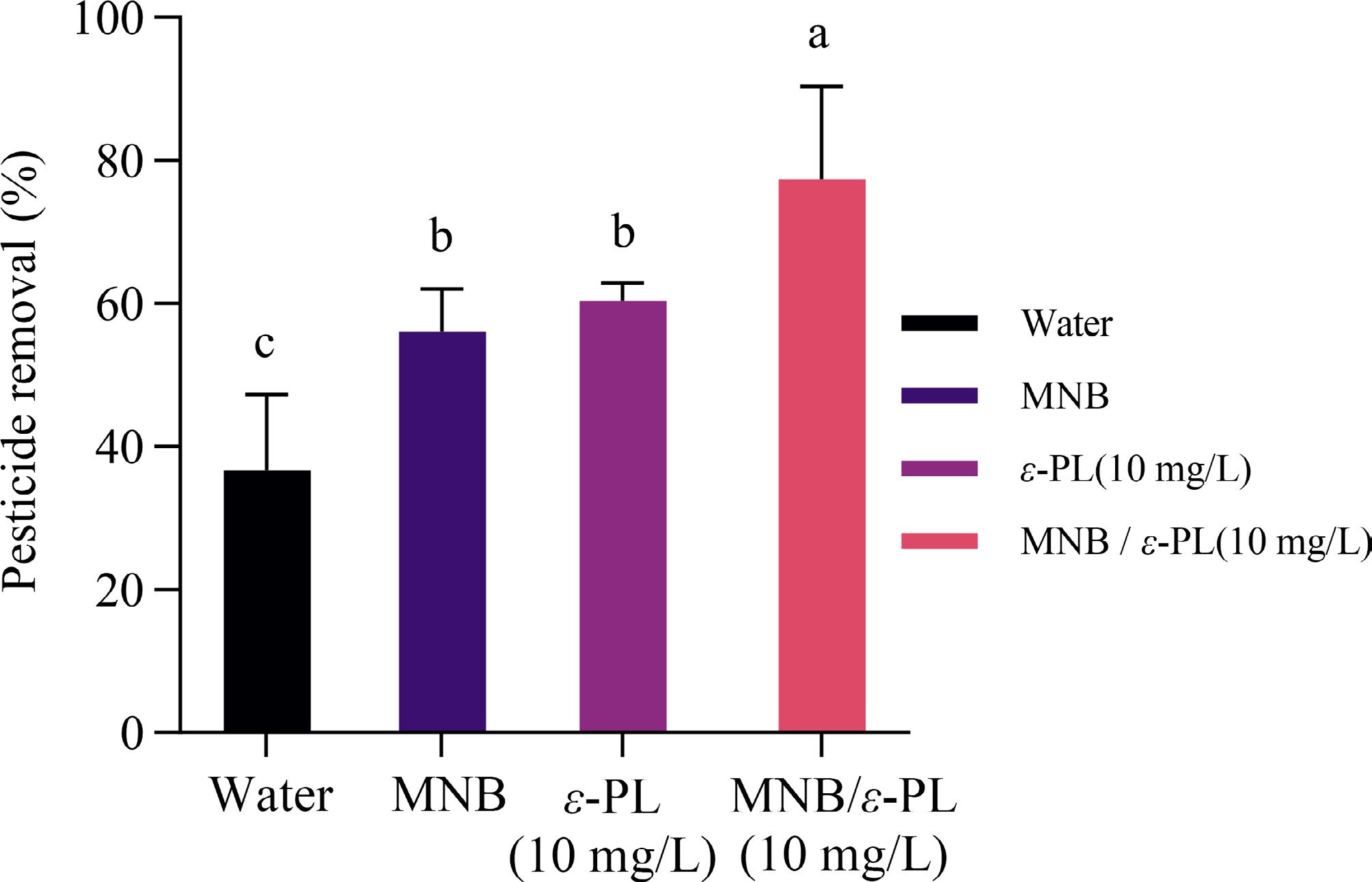

Effect of micro-nanobubbles combined with ε-PL on the removal rate of trichlorfon residues

-

The efficiency of MNB treatments for trichlorfon removal from apples is shown in Fig. 4, with the removal rates ranging from 38 to 78%. MNB and ε-PL alone significantly (p < 0.05) remove trichlorfon by 20% compared to the water wash. These facts indicated that both ε-PL and micro-nanobubbles disrupted the adhesion between trichlorfons and apple skin. Previous studies found that ε-PL demonstrated emulsifying and encapsulating action when mixing with trichlorfon hence the improvement by ε-PL for pesticide removal action may ascribe to the similar interactions between ε-PL and trichlorfons. Comparatively, MNB/ε-PL (10 mg/L) exhibited the highest level of pesticide removal rate (77.3%), significantly increased (p < 0.05) than any other treatments. A few studies have explored the ability of MNB to remove trichlorfon from fresh produce. Ikeura et al., immersed cherry tomatoes and lettuce in 2 ppm bubbling ozone MNB water for 10 min, which reduces trichlorfon as much as 35% and 55%, respectively[40]. Our treatment achieved a higher removal rate, partly due to the smooth skin of apples with relatively lower surface tension. However, there are also researchers observing a significant (p < 0.05) higher removal rate (98%−100%) of trichlorifon and carbosulfan after treating fresh apples with ozone MNB solution at a 0.33 L/s flowing rate for 5 min, compared to tap water, partly due to the high oxidability of ozone with a much higher concentration[41]. Thermal treatments have also been studied to remove pesticides on apple, aiming to reduce pesticides with strobilurin and triazole groups. Whereas baking apple peels for 20 min at 210 °C could only reach a 49% reduction, with a high level of nutrition and water loss of apples[42]. Over all, we observed that MNB/ε-PL (10 mg/L) achieved improved pesticide removal effectiveness, whereas no synergistic or additive effect was revealed.

Figure 4.

Effect of micro-nanobubbles combined with ε-PL on the removal rate of trichlorfon residues. Difference analysis p < 0.05.

Effect of micro-nanobubbles combined with ε-PL on the storage quality of apples

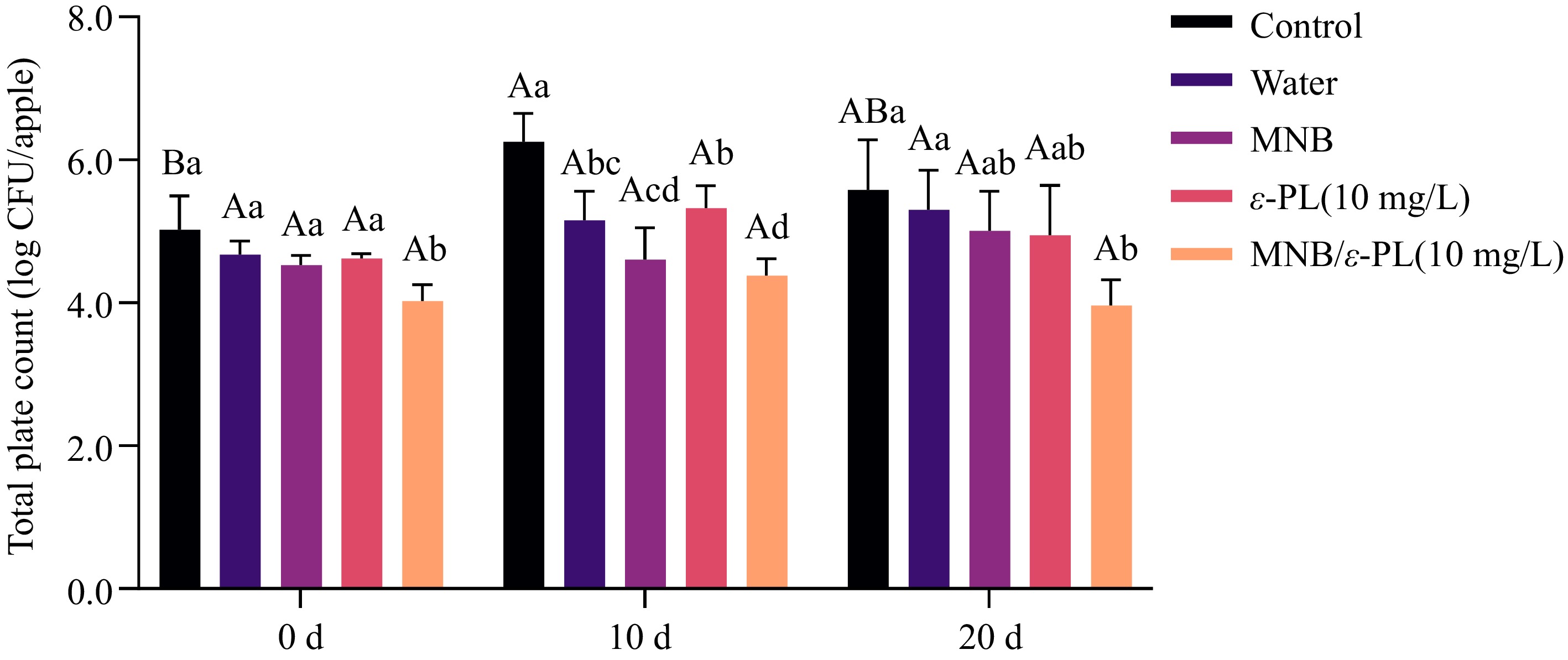

Indigenous microbial load on apples

-

Changes in the total number of colonies of apples during storage are shown in Fig. 5. At day 0, the total plate counts on fresh apples remained comparable to the control, except that MNB/ε-PL (10 mg/L) significantly decreased the TPC. During the storage, TPC for all treated samples did not show significant changes (p < 0.05) comparing day 20 to day 0. However, washed apples treated by MNB indicated a relatively lower level of TPC. Specifically, MNB/ε-PL (10 mg/L) resulted in lower TPC (p < 0.05) than water or MNB wash alone at day 10, as well as water wash at day 20. As reported by Lee et al., the aerobic bacteria, mold, and yeast counts of chestnuts were significantly lower after treatment with 10 min ozone MNB, and stored in LDPE film at 4 °C and 90% RH% for 16 weeks[43]. Results coincided with previous reports that MNB-assisted washing may be able to control the growth of spoilage microorganisms, under the circumstances in this study.

Figure 5.

Total plate count of whole apples during storage. Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between storage periods within the same treatment group, and different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatment groups within the same storage period (p < 0.05).

Color

-

During the storage, no significant differences between treatments and sampling days were observed for L and b values (Table 2). As for a value, control and ε-PL groups possessed reduced values (p < 0.05) at day 10 and day 20. To better describe the browning of apples, the browning index (BI) was calculated, and results demonstrated increments of BI in all groups during storage, except for water-washed samples. However, there was a trend that MNB-assisted washes delayed browning development, but no significant differences were observed for groups on the 20th d. Nevertheless, no significant differences were identified based on visual observations of the apples. One study found that 4 mg/L ozone microbubble delayed the loss of chlorophyll, thus helping to retain the original color of spinach[44]. Whereas we did not observe an obvious effect on color pigment retention in apples.

Table 2. Effect of micro-nanobubbles and ε-PL on apple quality and colony size.

Quality indicators Storage time (d) Control Water MNB ε-PL (10 mg/L) MNB/ε-PL (10 mg/L) L* 0 39.6 ± 4.3Aa 38.9 ± 5.2Aa 38.0 ± 4.3Aa 38.3 ± 6.7Aa 40.6 ± 8.8Aa 10 40.0 ± 4.3Aa 42.4 ± 5.3Aa 42.4 ± 4.3Aa 40.9 ± 6.7Aa 42.7 ± 8.8Aa 20 35.7 ± 2.2Aa 39.6 ± 5.5Aa 38.0 ± 2.8Aa 42.3 ± 4.0Aa 40.1 ± 2.5Aa a* 0 19.7 ± 2.2Aa 17.6 ± 2.8Aa 19.5 ± 1.2Aa 17.6 ± 0.8Aa 15.4 ± 4.6Aa 10 16.4 ± 2.2Ba 15.1 ± 2.8Aa 14.3 ± 1.2Aa 12.8 ± 0.1Ba 11.6 ± 4.6Aa 20 15.1 ± 0.4Ba 13.2 ± 2.2Aa 14.8 ± 1.6Aa 12.3 ± 0.9Ba 12.9 ± 2.6Aa b* 0 13.5 ± 2.2Aa 13.5 ± 4.0Aa 12.4 ± 1.7Aa 14.7 ± 1.9Aa 13.1 ± 4.2Aa 10 17.3 ± 2.2Aa 18.0 ± 4.0Aa 18.0 ± 1.7Aa 19.7 ± 1.9Aa 19.9 ± 4.2Aa 20 16.2 ± 2.1Aa 14.5 ± 4.1Aa 16.6 ± 3.2Aa 16.8 ± 5.3Aa 16.0 ± 5.4Aa BI 0 75.1 ± 3.4Ba 73.7 ± 7.4Aa 74.1 ± 7.2Ba 69.3 ± 6.8Ba 65.5 ± 8.8Ba 10 83.8 ± 4.1Aa 79.3 ± 6.5Aa 78.2 ± 8.4Aba 87.8 ± 6.5Aa 80.0 ± 11.5ABa 20 88.3 ± 4.1Aa 85.4 ± 6.9Aa 91.7 ± 8.4Aa 88.6 ± 6.5Aa 96.5 ± 11.5Aa Hardness (N) 0 73.4 ± 8.0ABab 78.3 ± 7.4Aa 69.6 ± 6.6Aab 63.7 ± 10.7Bb 79.7 ± 13.4Aa 10 80.1 ± 9.6Aa 75 ± 11.5Aba 74.4 ± 13.6Aa 83.3 ± 5.0Aa 75.3 ± 12.3Aa 20 64.9 ± 10.7Ba 65.6 ± 8.5Ba 77.8 ± 6.6Aa 72.6 ± 12.7Ba 68.1 ± 7.8Aa Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between storage periods within the same treatment group, and different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between treatment groups within the same storage period (p < 0.05). Browning of apple flesh was also investigated by visual observation (Fig. 6). After 20 d of storage, the color of the internal flesh became slightly darker for all samples. Additionally, a few browning spots close to the apple skin and stem were found for water washed sample on day 10 and ε-PL treated sample on day 20. These changes were suspected to be randomly mechanical damages during transportations or washing processes, disrupting fruit cells and causing the release of intracellular enzymatic browning reaction-relevant substances, such as polyphenol oxidase (PPO)[45].

Hardness

-

The hardness of apple post-decontamination treatments either decreased or experienced variance. The significant reduction in the hardness of apples compared to day 0 by the end of storage has been reported by similar works where the hardness of apples was reduced by nearly half after 30 d of storage[46]. On the other hand, the hardness of apples increased at day 10 and then decreased after day 20 post-control and ε-PL treatment, this was probably due to a gradual water loss in the initial part of storage according to Ullah et al.[47]. Afterward, the flesh cells started severe degradation with changes in cell wall components, thus leading to a significant reduction. Overall, we did not find any negative impact on apple texture (hardness) caused by MNB-assisted decontamination during the following storage.

-

This study investigated the efficacy of air micro-nanobubbles (MNB) combining polylysine (ε-PL) for decontaminating fresh apples. Results demonstrated that the air MNB + 250 mg/L polylysine significantly improved the microbial decontamination, reaching 3.43 and 3.19 log CFU/piece, for Listeria monocytogenes and Pichia kudriavzevii, respectively. MNB-assisted washing also removed trichlorfon with the highest rate of 77.3%. The developed decontamination method did not show an apparent negative impact on apples during storage. The findings suggest that air MNB-assisted washing with ε-PL is a promising approach for enhancing the safety and quality of fresh apples, offering a green and effective alternative to traditional decontamination methods.

Authors acknowledge the support of the CAU-Cornell Dual-degree Program. The authors also appreciate the support from the 2115 Talent Development Program of China Agricultural University.

-

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Lu H, Shi Z, Zhang H; data collection: Lu H, Tan S, Wang J, Shi Z; analysis and interpretation of results: Lu H, Shi Z, Zhang H; draft manuscript preparation: Lu H, Shi Z; editing and manuscript revision: Lu H, Tan J, Zhang H, Shi Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Haozhe Lu, Zhiling Shi

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Lu H, Shi Z, Tan S, Wang J, Tan J, et al. 2025. Decontamination of fresh apples using air micro-nanobubbles with epsilon-poly-lysine. Food Innovation and Advances 4(4): 446−453 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0038

Decontamination of fresh apples using air micro-nanobubbles with epsilon-poly-lysine

- Received: 23 December 2024

- Revised: 26 April 2025

- Accepted: 28 April 2025

- Published online: 29 October 2025

Abstract: Fresh and minimally processed apples demand high-efficiency decontamination approach to ensure their safety and quality. This research investigated air micro-nanobubbles (MNB) assisted washing as an innovative decontamination method for fresh apples, to improve the overall efficiency, a food-grade antimicrobial agent epsilon-poly-lysine (ε-PL) was simultaneously used during the examinations for removing representative pathogen, spoilage yeast, and pesticides from the fruit surface. The findings revealed that the combined ε-PL (250 mg/L) and MNB treatment substantially decreased the microbial load on apple surfaces, achieving beyond 3-log reductions for both Listeria monocytogenes and Pichia kudriavzevii. The pesticide removal rate of trichlorfon by MNB and ε-PL reached 77.3%, significantly (p < 0.05) higher than individual treatments. Additionally, apple quality post-MNB-assisted decontaminations did not show significant differences compared to other treatments after 20 d of storage. MNB-assisted washing with ε-PL is a promising technology for fresh produce decontamination.