-

Before the advent of epigenetics, the concepts of genotype, phenotype, and 'gene' held distinctly different meanings from those later consolidated during the Modern Synthesis, which integrated Mendelian genetics with Darwinian evolution[1]. These three foundational terms were first articulated in the early 20th century by the Danish plant physiologist Wilhelm Johannsen[2]. His pioneering experiments in bean seed selection, coupled with his theoretical articulation of the genotype–phenotype distinction, played a pivotal role in establishing genetics as a formal scientific discipline.

Johannsen's holistic conception of the genotype served as a critical counterpoint to the increasingly DNA-centric interpretations of the chromosome theory of heredity that dominated mid-20th-century genetics. Although Johannsen acknowledged the groundbreaking achievements of the Drosophila research group, he remained steadfast in highlighting the theoretical limitations of the chromosome-centric view. The mapping of genes onto chromosomes, he argued, could account for only a portion of biological heredity and evolutionary dynamics.

In his seminal 1909 treatise, Johannsen described genes as 'passive influences'—a notion central to his philosophy of heredity. He posited that while genes establish the potential for specific traits, they do not act independently, nor do they autonomously drive developmental processes[3]. Instead, phenotypic traits emerge from dynamic interactions between genetic elements and environmental inputs, indicating that genes function not as isolated determinants but as components of broader regulatory networks[3,4].

This perspective—emphasizing the conditional and interdependent nature of gene function—asserted that genes provide the blueprint, but not the full instruction manual, for phenotypic realization. Moreover, Johannsen was the first to offer a clear conceptual distinction between genotype, defined as the organism's underlying genetic architecture, and phenotype, the observable characteristics shaped by both genetic and environmental influences[3,5]. This differentiation became a cornerstone of the gene–environment interaction paradigm, wherein phenotypic expression is understood not as a direct readout of genetic information, but as a context-dependent outcome modulated by extrinsic factors[3]. His portrayal of genes as developmentally 'non-autonomous' agents profoundly influenced subsequent theoretical frameworks, laying intellectual groundwork for the emergence of epigenetic thought—where gene expression can be regulated independently of changes in the DNA sequence itself[6].

Approximately three decades later, building upon Wilhelm Johannsen's foundational insights, Conrad Waddington introduced the concept of epigenetics in the 1940s—a term that has since undergone a profound evolution in both its definition and scientific significance[7]. Initially, Waddington employed the term to describe the developmental processes through which genes and their products give rise to observable traits, or phenotypes, invoking a metaphorical framework known as the epigenetic landscape.

Despite the dramatic expansion of biological knowledge in the ensuing decades, the term 'epigenetics' has endured, even as its conceptual boundaries have been redrawn. While modern interpretations have refined and diversified its scope, the nomenclature itself remains intact.

Today, epigenetics is primarily concerned with the molecular mechanisms that enable cells to commit to specific developmental trajectories and maintain these states across cellular or even generational divisions. This contemporary framework challenges the classical, gene-centric view of heredity, suggesting that heritable variation can also arise from regulatory modifications beyond the DNA sequence—thereby broadening our understanding of inheritance and offering fresh perspectives on evolutionary theory[8].

Far from being a recently established discipline, epigenetics has long existed as a conceptual domain, though only in recent years has it achieved recognition as a distinct and experimentally tractable field of research. Waddington originally coined the term to capture the intricate interplay between genes and the developmental processes that shape an organism's phenotype. At the time, the role of genes in development remained largely enigmatic, but Waddington presciently recognized that development was governed by interconnected networks of gene activity.

The epigenetic landscape, his enduring metaphor, conceptualized development as a ball rolling down a contoured slope, where valleys and ridges represented the potential cell fates a given lineage might follow[9]. In this analogy, genes were imagined as pegs anchoring 'guy ropes' that sculpted the topography of the landscape. Through this imagery, Waddington conveyed that development is not dictated by linear gene–trait relationships, but by dynamic, multigenic interactions. Mutations in a single gene could thereby reshape the entire developmental trajectory, emphasizing that phenotypic outcomes result from systemic perturbations rather than isolated genetic effects.

While Waddington's conceptualization of epigenetics focused on the interaction of genes in shaping developmental trajectories, his perspective diverged from what later emerged as the field of developmental genetics. Traditional developmental genetics has primarily emphasized the role of genetic mutations in influencing developmental processes. In contrast, Waddington and his contemporaries were more deeply invested in exploring how genetic and phenotypic variation are frequently decoupled—that is, genetic variation does not always result in observable phenotypic change, and conversely, phenotypic differences can arise in the absence of discernible genetic mutations.

To describe this buffering phenomenon, Waddington introduced the principle of 'canalization', referring to the capacity of developmental systems to produce stable phenotypic outcomes despite genetic or environmental perturbations. Counterbalancing this idea is the concept of plasticity, which denotes the potential of genetically identical cells or organisms to exhibit divergent phenotypes in response to environmental cues. Together, canalization and plasticity underscore the capacity of epigenetic mechanisms to dissociate genotype from phenotype, revealing that development is far more context-sensitive and environmentally responsive than previously assumed.

In contemporary biology, the conceptual boundaries between epigenetics and developmental genetics have increasingly converged. Today, developmental biologists widely acknowledge that gene expression and differentiation are governed by intricate regulatory networks and dynamic molecular interactions. Nonetheless, epigenetics persists as a critical interpretative framework for understanding how cellular identities are established, maintained, and occasionally reprogrammed.

Waddington and his contemporaries viewed epigenetics as integral not only to developmental biology but also to evolutionary theory. They were particularly interested in the evolutionary dynamics of developmental systems—how phenotypic transitions arise, and how natural selection may act to enhance or diminish canalization and plasticity over time. Among Waddington's most influential contributions was his experimental demonstration of 'genetic assimilation', wherein an environmentally induced trait in Drosophila became genetically encoded over successive generations—even in the absence of the original environmental stimulus[10]. This work provided compelling evidence that epigenetic responses to environmental factors could become fixed within the genome, thereby linking developmental plasticity with evolutionary change.

The foundation for understanding gene regulation was further advanced through the integration of Waddington's epigenetic theory with Chargaff's elucidation of the chemical structure of DNA. Waddington's framework emphasized that gene expression is modifiable by environmental conditions and cellular context, while Chargaff's work revealed the biochemical substrate upon which such regulation occurs. Together, their contributions catalyzed the emergence of molecular epigenetics, clarifying how genes may be selectively activated or silenced without changes to the DNA sequence itself[10].

For several decades following its introduction, the term epigenetics remained marginal within the broader scientific discourse, often used interchangeably with developmental biology. However, this changed dramatically in the 1980s and 1990s, as researchers increasingly turned their attention to the molecular underpinnings of gene regulation during development. During this period, epigenetics became firmly associated with studies of gene activation and repression—particularly in the context of cell differentiation—marking its transformation into a core field of molecular biology.

-

By the turn of the 21st century, epigenetics had emerged as a distinct subfield of biology, catalyzed by the elucidation of key molecular mechanisms that govern gene regulation—notably, histone modifications, DNA methylation, and non-coding RNAs. These discoveries have helped explain how cells preserve their identity over time and how certain traits influenced by environmental stimuli can be inherited, even in the absence of genetic mutations. As a result, epigenetic inheritance is now widely regarded as a critical driver of developmental biology, with profound implications for our understanding of evolutionary processes.

Yet, despite its growing prominence, the definition of epigenetics remains contested. Some scholars have criticized its conceptual sprawl, arguing that the term encompasses such a broad array of phenomena that it risks losing explanatory power. Joshua Lederberg, for instance, proposed abandoning the term altogether in favor of more granular classifications such as 'nucleic', 'epinucleic', and 'extranucleic' to denote different layers of regulatory complexity. Nonetheless, a strong conceptual thread continues to link Waddington's original formulation with modern epigenetics, as both emphasize the interplay between genetic activity and environmental modulation in shaping development and evolutionary outcomes[11].

Today, epigenetics encompasses a vast and rapidly growing body of research. This includes investigations into how regulatory networks confer phenotypic stability[12], how heritable chromatin modifications underlie specific developmental trajectories[13], and how DNA methylation signatures preserve cellular identity over time[14]. The implications of this research extend far beyond theoretical biology, touching critical domains such as medicine, agriculture, and environmental conservation[15].

In the realm of medicine, epigenetics has become particularly salient for elucidating the mechanisms underlying complex diseases such as cancer. Aberrant DNA methylation in tumor cells, for example, can silence tumor suppressor genes and promote oncogenesis[16,17]. Given that epigenetic modifications are often reversible, considerable effort is now being directed toward developing therapeutic strategies that target these alterations—such as agents designed to reprogram methylation profiles or histone acetylation states[18].

Moreover, several hereditary disorders stem from defects in imprinted genes, where the epigenetic state is dependent on whether the gene is maternally or paternally inherited. Such epigenetic anomalies can manifest as disease phenotypes even in the absence of DNA sequence mutations[19,20]. This growing realization has prompted calls for a new disciplinary focus—'epigenetic epidemiology'—aimed at tracking how environmental exposures exert intergenerational effects on health[21]. Research has demonstrated, for instance, that maternal starvation or prenatal stress can induce epigenetic changes that persist into subsequent generations, shaping phenotypes in offspring and grandchildren alike[22,23].

Epigenetics has also assumed a pivotal role in agriculture, particularly regarding the stability and expression of transgenic traits. DNA methylation can lead to the unintended silencing of introduced genes in genetically modified crops, posing a challenge for sustained trait expression. To address this, researchers are exploring epigenetic engineering as a tool to enhance stress tolerance, yield consistency, and environmental adaptability.

In conservation biology and ecology, epigenetic mechanisms may help explain how species adapt to rapidly shifting environments. Environmentally induced epigenetic changes—capable of being transmitted across generations—suggest that conservation strategies must account not only for genetic diversity but also for epigenetic variability. Against this background, the most widely accepted contemporary definition states: Epigenetics is the study of heritable changes in gene expression that do not involve alterations to the DNA sequence—a change in phenotype without a change in genotype'. To further unravel the significance and delineate the scope of epigenetics, this review proposes its conceptualization through the lens of three interrelated frameworks:

Molecular structure

-

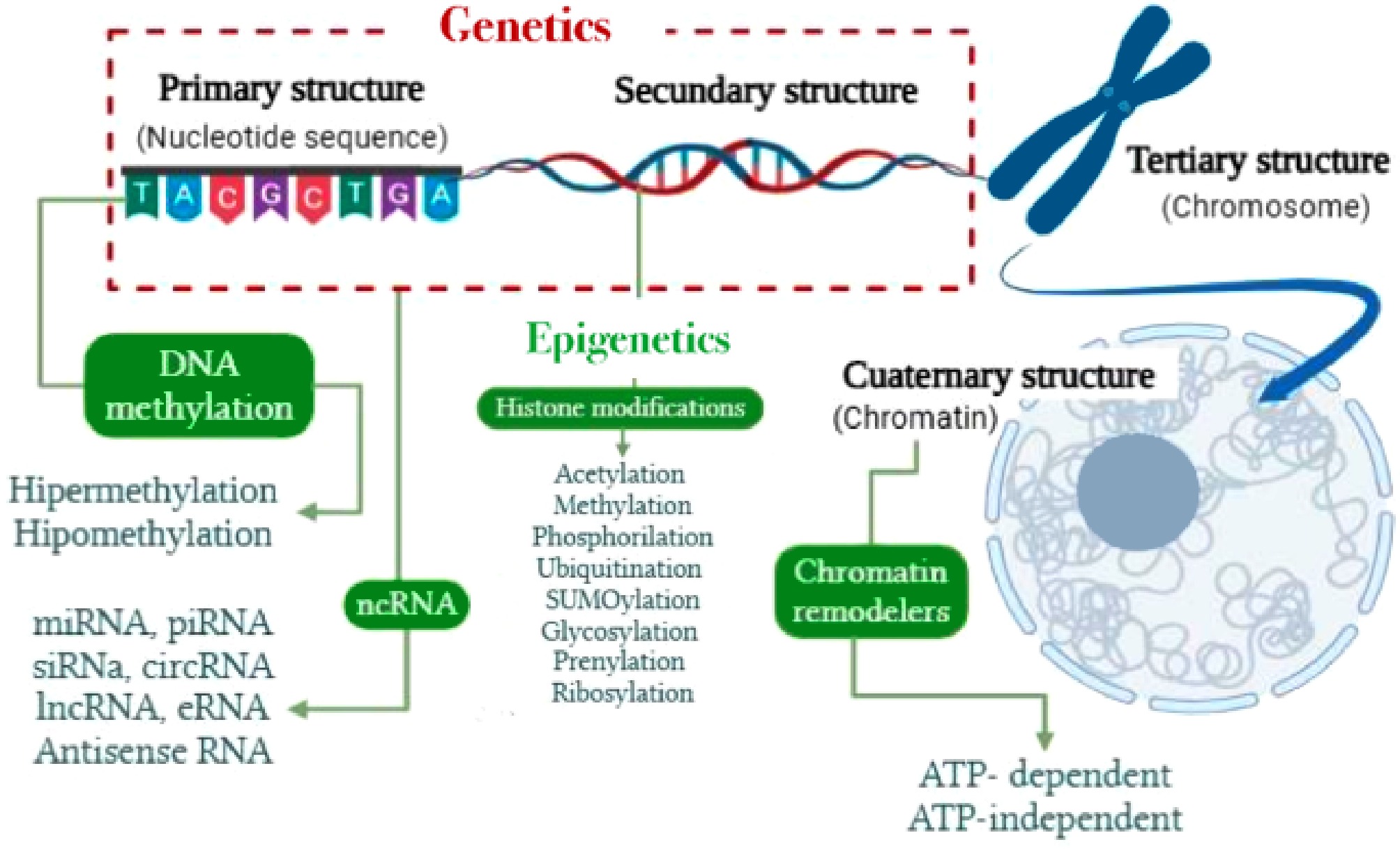

Starting with genetics as the outcome of DNA replication, the primary molecular structure—the linear sequence of nucleotides—encodes the essential blueprint for cellular architecture and function. This primary sequence dictates secondary structural conformations, including the iconic double helix, through base complementarity. These structures, in turn, support gene function and enable or restrict molecular interactions, thereby influencing gene expression dynamics (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Correlation between genetics and epigenetics from a molecular structural perspective, highlighting major existing epigenetic mechanisms. Adapted from Meza-Menchaca et al.[24].

Understanding these hierarchical structural levels illuminates key aspects of epigenetic regulation, as demonstrated by Meza-Menchaca et al.[24]. The folding and unfolding of tertiary and quaternary chromatin conformations align with modern epigenetic principles, serving as dynamic modulators of transcriptional activity. Structural alterations—such as nucleosome repositioning or histone variant exchange—regulate access to the genomic template, enabling the silencing or activation of genes without modifying the DNA sequence itself.

This inherent structural plasticity lies at the heart of epigenetic responsiveness, enabling context-specific gene regulation in response to environmental, developmental, or physiological cues. As such, structural adaptability forms the foundation for understanding gene–environment interactions and cellular identity.

Molecular biogenesis

-

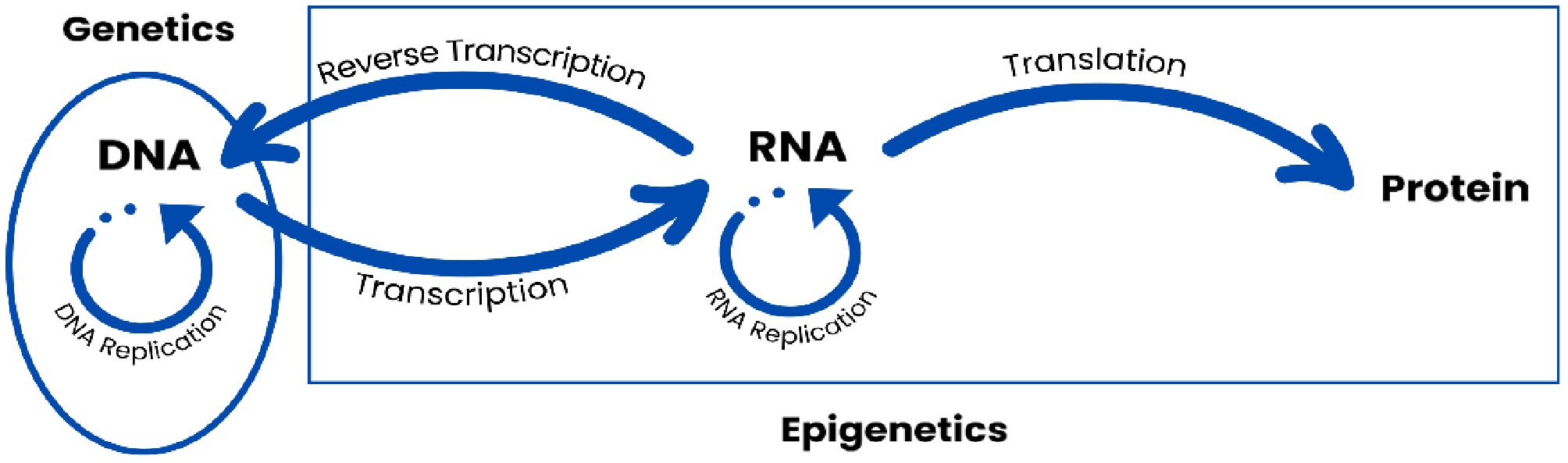

The central dogma of molecular biology—and its subsequent elaboration in the post-genomic era—provides a structured framework for distinguishing between genetic and epigenetic processes. Within this paradigm, the sequential processes of replication, transcription, and translation demarcate the respective domains of genomic fidelity and regulatory plasticity.

DNA replication, intrinsically tied to genetics, ensures the precise duplication and preservation of the genome—an immutable and highly conserved sequence of information. In contrast, transcription represents a pivotal shift, introducing molecular diversity and regulatory complexity through the production of structurally and functionally diverse RNA species (Fig. 2). This transcriptional phase is a major entry point for epigenetic modulation, encompassing mechanisms that extend far beyond static nucleotide sequences.

Figure 2.

Defining the conceptual boundaries between genetics and epigenetics through the lens of molecular biogenesis, highlighting key regulatory mechanisms that extend and reinterpret the central dogma of molecular biology.

Post-transcriptional modifications of mRNA and the regulatory actions of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) exemplify how gene expression can be fine-tuned without altering the genomic template. These processes, including RNA editing and the interaction of transcripts with epigenetic regulators, enable expression divergence from the original DNA code and introduce additional layers of phenotypic variability.

A prominent example of such epigenetic complexity is alternative splicing, a mechanism that likely emerged during the Neoproterozoic era[25]. Through selective exon rearrangement during RNA processing, a single gene can yield multiple transcript variants, giving rise to structurally distinct RNAs or proteins. This capacity for isoform generation reflects a profound level of regulatory sophistication, allowing for nuanced functional specialization across tissues, organs, and entire organ systems in multicellular organisms.

Thus, the epigenetic capacity to generate transcriptomic and proteomic isoforms is a defining feature of complex life, underpinning the emergence and maintenance of cellular diversity and functional integration in higher organisms.

Subcellular localization perspective (in situ)

-

The three-dimensional architecture of chromatin and nuclear topology plays a central role in regulating gene accessibility and transcriptional activity, governing the spatial orchestration of DNA within the nucleus. Emerging research has demonstrated how external cues—including diet, psychological stress, environmental toxins, and microbial interactions—can reconfigure the epigenome, thereby modulating biological responses at both cellular and systemic levels. Among the most functionally diverse epigenetic regulators are long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), whose subcellular distribution is often closely tied to their biological roles. While the majority of lncRNAs are active within the nucleus, a significant subset localizes to the cytoplasm, where they engage in distinct regulatory functions:

Nuclear localization: Many lncRNAs exert their activity within the nucleus, where they participate in transcriptional control, chromatin remodeling, and broader epigenetic modifications. They often act by interacting with transcription factors or chromatin-modifying complexes to modulate gene expression at specific loci[26].

Cytoplasmic localization: Some lncRNAs are exported to the cytoplasm, where their functions diverge considerably. Here, they may stabilize or destabilize mRNA transcripts, influence translational efficiency, or serve as molecular decoys—'sponging' microRNAs (miRNAs) to prevent their binding to target mRNAs[24].

Extracytosolic Influence via the Interactome: Beyond conventional subcellular compartments, the cellular interactome—the intricate network of protein, RNA, and DNA interactions—reveals yet another layer of epigenetic complexity. Mobile genetic elements such as transposons ('jumping genes') have emerged as unexpected yet pivotal contributors, embedding themselves into regulatory regions and reshaping chromatin landscapes[27]. These elements influence gene expression by mediating transcription factor recruitment and altering chromosomal architecture. Recent studies suggest that transposons can facilitate combinatorial interactions among transcription factors, thereby enhancing cellular adaptability and functional diversity[28].

This dynamic behavior is mirrored in large-scale protein–protein interactome maps, which show that transposons may be integrated into broader regulatory networks, influencing processes such as cellular differentiation, immune response, and intracellular signaling[29]. Indeed, transposons have been implicated in the evolution of immune-regulatory genes, where their modulation of transcription factor binding sites has increased the flexibility and responsiveness of immune pathways[27,28].

Furthermore, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs)—particularly in the cytoplasmic compartment—are increasingly recognized for their roles in environmental toxicology. Cytoplasmic ncRNAs, including microRNAs, lncRNAs, and circular RNAs (circRNAs), orchestrate stress responses and modulate gene expression in response to toxins or cellular injury[30]. Their functional diversity renders them essential mediators of environmental and xenobiotic responses[31].

Although the precise mechanisms enabling lncRNAs to shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm remain under investigation, this bidirectional mobility underscores the multifunctional capacity of ncRNAs, as they integrate signals across cellular compartments to orchestrate complex regulatory outcomes.

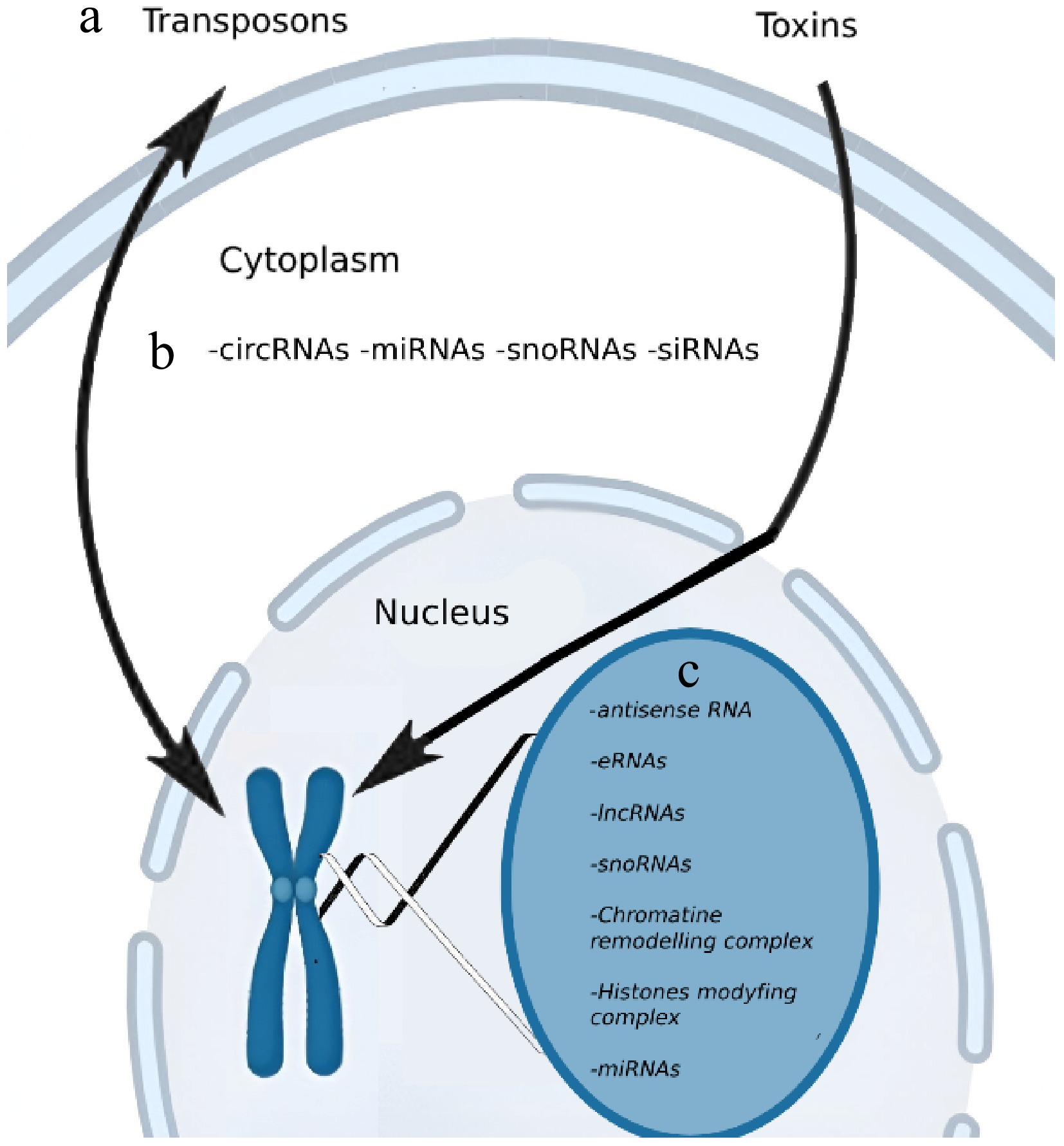

During the 1990s, a more restrictive definition of epigenetics gained prominence, emphasizing 'heritable changes in gene function that cannot be explained by changes in DNA sequence.' This conceptual narrowing was catalyzed by pivotal discoveries regarding DNA methylation, a central mechanism by which cells retain regulatory memory across divisions. The contributions of researchers such as John Holliday, who investigated the persistence of cellular identity through epigenetic marks, were instrumental in formulating the modern notion of epigenetic inheritance—whereby regulatory states can be transmitted across generations independent of any underlying genetic mutation (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic overview of subcellularly localized epigenetic regulators. These include: (a) Transposons that interact bidirectionally with the genome, as well as toxins that influence the genome through a unidirectional pathway. (b) Four specific non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) present in the cytoplasm, which can interact with me messenger RNAs (mRNAs). (c) Five distinct ncRNAs that act within the nucleus and chromatin-modifying complexes.

-

From an evolutionary standpoint, epigenetics introduces novel questions and significant challenges to the classical neo-Darwinian framework. While most evolutionary biologists contend that epigenetic inheritance can be reconciled within the current evolutionary paradigm, its mechanisms also evoke the possibility of Lamarckian inheritance—where traits acquired through environmental exposure may be transmitted across generations. Though controversial, this notion suggests that evolutionary change may not be solely governed by alterations in DNA sequence, but also by heritable modifications in how genes are regulated and expressed in response to environmental conditions.

Cancer biology, too, has been increasingly illuminated through the lens of epigenetics—a field concerned with regulatory changes in gene expression that occur independently of DNA sequence mutations. Epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA-mediated interference orchestrate gene activity, influencing crucial cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. In many malignancies, aberrant epigenetic alterations result in the silencing of tumor-suppressor genes or the activation of oncogenes, thereby driving uncontrolled cell division[32]. Aberrant methylation patterns have been identified across diverse cancer types, leading to the epigenetic inactivation of genes that would otherwise suppress tumor formation[33].

Unlike genetic mutations, epigenetic changes are potentially reversible, rendering them attractive targets for therapeutic intervention. Current strategies include DNA methylation inhibitors and histone deacetylase inhibitors, which aim to reactivate silenced tumor-suppressor genes and attenuate tumor growth[34]. These therapeutic approaches demonstrate how reprogramming epigenetic states may offer clinical benefit without the need to modify the genetic sequence itself.

Moreover, epigenetic alterations not only influence cancer initiation but also modulate therapeutic response. Tumor cells may acquire resistance to chemotherapy or radiation via epigenetic reconfiguration of drug targets or DNA repair pathways[35]. A detailed understanding of a tumor's epigenetic landscape could therefore guide more personalized and adaptive treatment strategies, potentially improving clinical outcomes.

Epigenetic biomarkers are also emerging as powerful tools in oncology, offering promise for early detection, prognosis, and monitoring of therapeutic response. Distinct DNA methylation signatures or histone modification profiles in blood or tissue samples may serve as indicators of cancer onset or progression[36]. This expanding field underscores the idea that cancer is not exclusively a genetic disorder but rather one shaped by the intricate interplay between genetic mutations and epigenetic regulation. As the understanding of cancer epigenetics deepens, the development of novel therapies that target both mutational drivers and regulatory pathways may redefine oncological treatment paradigms—ushering in an era of more precise, effective, and adaptable treatments[37].

Waddington's original theory of epigenetics was remarkably prescient, as it anticipated the dynamic interplay between genes and environmental factors in shaping development. Today, epigenetics has evolved into a mature field, focused on the molecular mechanisms that regulate gene activity independently of alterations in the DNA sequence. Waddington's metaphorical epigenetic landscape is now grounded in concrete biological mechanisms—such as DNA methylation, histone modification, and non-coding RNA regulation—and the scope of the field has broadened substantially to encompass patterns of inheritance, the molecular basis of disease, and environmental responsiveness.

Epigenetics has fundamentally expanded the conceptualization of heredity and evolution, offering a framework that transcends the traditional gene-centric paradigm. It demonstrates that inheritance involves more than just the transmission of DNA; it also includes the modulation of gene expression by extrinsic factors, which can influence phenotypic outcomes across generations. By integrating epigenetic mechanisms into evolutionary biology, researchers move toward a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of how organisms adapt and evolve, with far-reaching implications for biomedicine, agriculture, livestock, and ecological conservation.

Yet, despite its growing empirical foundation, no universally accepted definition of epigenetics has been established, and the boundary between epigenetics and classical genetics remains blurred. This conceptual ambiguity invites a reevaluation of epigenetics, which may be constructively reframed through three complementary scopes: structural, molecular biogenesis, and morphological. These perspectives may help delineate the field more precisely, allowing for clearer theoretical distinctions and methodological frameworks.

Crucially, any future redefinition of epigenetics must be anchored in rigorous experimental validation, with special emphasis on environmental modulation, whether occurring at the tissue-specific level or across ecological systems. Such efforts will be essential to establish a cohesive theoretical and experimental foundation, enabling the field to continue advancing its contributions to the life sciences.

-

The study did not involve human participants or animal subjects, so no ethical approval was required.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Meza-Menchaca T; conceptualization, topic design, writing, managing financial resources: Giancarlo VM; writing, visualization: Melgar-Lalanne G; visualization and design: Meza-Menchaca T, Giancarlo VM; interpretation of discussion and development and managing of the manuscript: Ricaño-Rodríguez J, Aguirre-von-Wobeser E. All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception, design, and writing of the manuscript, and approve the final version for publication.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

We would like to express our gratitude to Universidad Veracruzana (Faculty of Medicine PROMEJORAS committee) for financial support, and also Ms. Claudia Ronzón-Portilla for her help on checking the manuscript.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Meza-Menchaca T, Giancarlo VM, Melgar-Lalanne G, Ricaño-Rodríguez J, Aguirre-von-Wobeser E. 2025. Reframing epigenetics: three dimensions in the post-genomic era. Epigenetics Insights 18: e014 doi: 10.48130/epi-0025-0012

Reframing epigenetics: three dimensions in the post-genomic era

- Received: 12 December 2024

- Revised: 07 August 2025

- Accepted: 01 September 2025

- Published online: 03 November 2025

Abstract: In the current century, the rapid advancements in epigenetics offer an exceptional opportunity to reexamine its scope, definitions, methodological approaches, and achievements, while critically addressing its conceptual underpinnings and prevailing epistemological limitations. The term, originally introduced by Conrad Waddington in the 1940s, refers to heritable changes in gene expression that occur independently of alterations in the DNA sequence. Epigenetics thus serves as a conceptual bridge linking genetics, developmental biology, and environmental interactions, emphasizing the dynamic modulation of phenotypic outcomes. Rooted in early theoretical insights from Johannsen and Waddington, the field has since undergone profound evolution, with contemporary research centering on mechanisms such as DNA–chromatin remodeling and the regulatory roles of non-coding RNAs. These processes underscore the plasticity of gene regulation in response to environmental cues, facilitating both developmental versatility and evolutionary responsiveness. In the post-genomic era, epigenetics has markedly extended its conceptual and functional boundaries, highlighting its role in maintaining cellular identity, orchestrating environmental adaptability, and contributing to both complex pathologies and physiological homeostasis. Accordingly, three distinct conceptual scopes that may aid in clarifying definitional boundaries and reinterpreting epigenetic phenomena were proposed. This concise review advocates for more rigorous definitions and empirical validations, offering a novel analytical framework for distinguishing epigenetics from classical genetics and advancing interdisciplinary insights across biological and applied sciences.

-

Key words:

- Epigenetics /

- Post-genomic /

- Molecular biology