-

Fungal infections are on the rise in immunocompromised individuals. Conidia/spores from fungal species inhabit a range of environments, such as soil, air, and plants, and thus colonise foodstuffs or a suitable host[1]. Although the majority of fungal species are nonpathogenic, in immunocompromised individuals, they turn to opportunistic pathogens, causing severe infections[2]. Recently, there has been a rise in fungal infections because of the growing resistance to certain medications, particularly antifungals and antimicrobials, especially among individuals with weakened immune systems[3]. Aspergillus terreus (A. terreus) is recognised as an opportunistic pathogen, and there has been a significant rise in infections caused by opportunistic fungi in recent years[4,5]. A. terreus is particularly capable of causing infections in individuals with weakened immune systems and can cause both acute and chronic infections in humans[6]. The prevalence of immunocompromised individuals has risen in recent years because of factors such as cancer cases, organ transplants, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)[7,8]. As a result, opportunistic fungal pathogens have found it easier to infect these susceptible hosts. A. terreus is the leading pathogen responsible for invasive aspergillosis (IA), especially among cancer patients[9]. Additionally, the natural resistance of A. terreus to amphotericin B (AmB)[10], an antifungal agent that has been commonly used for more than four decades, and its acquired resistance to other antifungals such as azoles[11] complicates the formulation of an effective treatment strategy.

The coexistence of cancer and Aspergillus infection creates a challenging clinical scenario, characterised by the interaction between cancer-induced immunosuppression and opportunistic fungal infections[12,13]. Patients with cancer often have a weakened immune system, either as a direct result of the cancer itself or as a consequence of immunosuppressive therapies such as chemotherapy[14,15]. This compromised state creates an environment that is favourable to opportunistic infections and underscores the urgent need for the development of new therapeutic agents and the exploration of compounds with antifungal activity against Heat shock protein (Hsp) 90[16].

Hsps have become a significant area of research because they are ubiquitous in all living organisms, ranging from bacteria to human cells[17,18]. They function as molecular chaperones, assisting in the proper folding and refolding of client proteins to ensure their functional conformation. In fungal cells, Hsps are crucial for cell morphogenesis and are essential for the survival of these organisms[19]. Research indicates that the levels of Hsps are elevated in cancerous cells as well[20,21]. Therefore, targeting these proteins with various pharmacological agents and techniques may represent a promising strategy for combating fungal infections and inhibiting the proliferation of cancerous cells[22].

The dysfunction of Hsps can lead to the accumulation of improperly folded and damaged proteins, which may result in cell death or the onset of various diseases, including cancer in humans[23,24]. Consequently, inhibiting Hsps can enhance the susceptibility of Aspergillus species to stress and drugs, thereby reducing its pathogenesis[16,25,26]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that inhibitors of Hsp70 and Hsp90, like phytochemicals and natural compounds such as curcumin, resveratrol, and geldanamycin (GA), have been shown to inhibit Hsp activity[27,28]. Consequently, our investigation focused on the drug GA, which was first extracted from the culture of Streptomyces hygroscopicus in 1970, where it was recognised as a tyrosine kinase inhibitor[29]. Initially classified as an antibiotic with antifungal capabilities[30,31], it is now known as an inhibitor of Hsp90[32,33]. GA interacts with Hsp90, thereby interfering with its normal functions. Despite its broad-spectrum activity and therapeutic promise, the clinical use of GA has been limited because of its toxicity in mammalian systems. GA can induce hepatotoxicity and affect normal cellular processes in human cells, posing a challenge for systemic administration. Therefore, understanding its selectivity and exploring modified derivatives or targeted delivery systems are essential to mitigate its toxicity while retaining its antifungal efficacy[1,6].

In the present study, we examined whether GA-induced disruption of the Hsp90 heterocomplex could affect the expression of cellular proteins, leading to inhibition of growth in A. terreus. In addition, using in silico tools, GA's interaction with Hsp90 provided insight into the growth inhibition mechanism.

-

A clinical isolate of A. terreus NCCPF860035 provided by Prof. M. R. Shiva Prakash (PGIMR, Chandigarh) was utilised for the study. The culture of A. terreus was grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at a controlled temperature of 37 °C[28]. Following a growth period of four days, spores were harvested using phosphate-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST) and were subsequently rinsed twice with chilled phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The spore concentration was quantified using a hemocytometer (Rohem, India) under the microscope (Olympus, India), and a concentration of 1 × 104 cells/mL[34] of the conidial suspension was used as the inoculum for experiments.

Calculation of the 50% minimum inhibitory concentration of GA using MTT assay

-

The working concentrations of the GA were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), ranging from 2 to 16 μg/mL. Spores of A. terreus (1 × 104 spores/mL) were incubated in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (HIMEDIA, Mumbai, India) alone or in the presence of GA at a temperature of 37 °C for a duration of 24 h, utilizing 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plates. Each well contained a final volume of 200 μL, (inoculating 10 μL of conidial suspension into 190 μL of the diluted drug at various concentrations mixed with RPMI). Following the 24-h incubation, 10 μL (5 mg/mL) of MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] from HIMEDIA (Mumbai, India)[35,36] was added into each well, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for an additional 3–4 h. The conversion percentage of MTT to its formazan derivative in each well in comparison with the control (drug-free) was calculated at a wavelength of 570 nm using a Multiskan spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Noida, India). Each concentration was tested in four technical replicates, and the experiment was independently repeated twice. The percentage of growth inhibition was calculated by comparing the absorbance values of treated wells with the untreated controls using the formula:

$ {\rm {Growth\;Inhibition}}\;({\text{%}})=\dfrac{G_t -OD}{C_t} \times 100 $ Antifungal assay and mycelial growth inhibition analysis

-

The antifungal assay was conducted to evaluate the antifungal efficacy of GA (CAYMAN Chemical Company, US). A stock solution of GA was prepared at a concentration of 1 mg/mL in DMSO (Qualigens, Mumbai)[35]. Subsequently, various working concentrations were derived from this stock solution. Following the findings presented in the study[27] regarding the antifungal activity of GA, and using the 50% minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC50) value, GA was tested against A. terreus. PDA plates were supplemented with 11 µg of the drug, and a conidial suspension (1 × 104 spores/mL) was inoculated at the centre before incubation at 37 °C for 24 h. The resulting colony diameters were measured from plate images using ImageJ software (NIH, USA), with a defined scale based on the known plate diameter (90 mm). Measurements were performed for two replicates per group, and the mean colony diameter (in mm) was calculated[37]. Data are reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), and statistical significance was evaluated using an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test in (SPSS Statistics software). A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The percentage of growth inhibition was calculated using the following formula:

$ \begin{split} & \rm{Inhibition\; of\; mycelial\; growth}\; ({\text{%}})= \\ &\dfrac{\rm{Mycelial\; growth\; (control)\;−\;Mycelial\; growth\; (treatment)}}{\rm{Mycelial\; growth\; (control)}}\times 100 \end{split} $ Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis

-

Cultures of A. terreus, both GA-treated and untreated, were utilized for total RNA extraction via the TRIzol method (TRIzol reagent, Invitrogen, USA)[38]. The concentration of RNA was quantified using a Multiskan spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Noida, India). For cDNA synthesis, the Verso cDNA kit (Thermo Scientific, Lithuania) was employed, utilizing 1 μg of RNA. The quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis was conducted using a CFX96 polymerase chain reactaion machine (BIORAD, USA). Each reaction incorporated 100 ng of cDNA and utilized the SYBR green qPCR kit (Thermo Scientific, Lithuania). The thermal cycling protocol included an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 3 minutes, followed by 40 cycles consisting of 30 seconds at 94 °C, 10 seconds at 54 °C, and 30 seconds at 72 °C. Additionally, melting curve analysis was performed for each sample. The 40S ribosomal S1 subunit served as the reference gene. Its expression was validated by assessing the Ct values' consistency across all samples, namely 31.44 (control) and 30.73 (treated), showing less than 1 Ct variation[39]. In addition, its suitability as a stable internal control in A. terreus has been supported by prior literature[28]. All qRT-PCR reactions were performed in triplicate, and each experiment was repeated at least three times independently to ensure reproducibility. The primers used are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. The primers used in this study.

Gene Primer Type Sequence (5’→3’) Hsp70 Forward GACCACGGAAATCGAGCAGA Reverse CATGGTGGGGTCGGAAATGA Hsp90 Forward CTCGCCAAGAGCCTCAAGAA Reverse GCTCCTTGATGATGGGGGAC 40S S1 Forward CATTGGCCGTGAGATCGAG Reverse CCCTTGTCATCGGTGGTAGA Cellular reactive oxygen species estimation

-

The impact of GA on intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in A. terreus was evaluated through a ROS assay. The assay utilized the fluorescent dye DCFDA (2,7-dichlorofluorescein diacetate) (LOBA Chemie Pvt. Ltd, Mumbai). DCFDA is widely used for quantifying ROS levels in cellular contexts[40]. ROS plays an important role in fungal development, including morphogenesis and apoptosis caused by an oxidative burst[41]. A suspension of A. terreus at a concentration of 1 × 104 cells/mL was prepared for both the control and GA-treated samples (MIC50 11 µg/mL). Following this, the samples were incubated at 37 ºC for 24h in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS), with continuous shaking. After incubation, the cells were harvested via centrifugation, suspended in PBS, and washed twice with PBS. Subsequently, the cells were treated with DCFDA at a concentration of 5 µg/mL and incubated at 37 ºC for 45 minutes with constant shaking. The fluorescence intensity of the 100-μL cell suspensions was examined under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus) using filters set for excitation at 485 nm and emission at 520 nm, ensuring consistent conditions. Quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity was performed using ImageJ software by selecting regions of interest (ROIs) for the control group and the treated group. Mean fluorescence intensity values were calculated and used for statistical analysis using an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test (SPSS Statistics software). A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant[37].

Molecular docking studies: Docking strategy

-

A primary objective in molecular docking is to estimate the scoring function and evaluate protein–ligand interactions to predict the binding affinity and activity of the ligand molecule[42]. The docking program AutoDockTools-1.5.7 version[43] was used to generate the bioactive binding positions of GA in the active site of protein Hsp90 and Hsp70 of A. terreus and Homo sapiens. Molecular docking is a computational technique used to predict the binding mode and affinity of a ligand (GA) to a target protein[44].

Protein preparation

-

The three-dimensional (3D) crystal structure of Hsp90 from A. terreus, which exhibits complete similarity (100%) to Hsp82 (UniProt ID: Q0CE88) and Hsp70 (UniProt ID: Q0D231) from the same organism, was obtained from the UniProt database. Additionally, the 3D crystal structures of Hsp90α (UniProt ID: P07900) and Hsp70 protein 6 (UniProt ID: P17066) of Homo sapiens were sourced from AlphaFold[45]. Subsequently, the protein preparation process involved the removal of water molecules, the incorporation of polar hydrogen atoms, and the addition of Kollman charges[46].

Ligand preparation

-

The 3D configurations of GA (CID5288382) were obtained from the NCBI PubChem database. The preparation involved the incorporation of polar hydrogen only, along with the addition of the computed Gasteiger charges[47].

Docking studies

-

Docking simulations were conducted using AutoDockTools 1.5.7, along with its ADT 4.2 graphical interface. A Lamarckian genetic algorithm (LGA) with 100 independent runs per ligand was used to obtain the best docking conformations. Each simulation was executed 100 times, resulting in 100 docked conformations to identify the optimal docking configurations[48]. The conformations with the lowest energy were considered to be the binding conformations between the ligands and the protein[49].

Statistical analysis

-

Each assay was performed with multiple biological and technical replicates. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or standard error of the mean (SEM), as indicated in the results. Statistical comparisons between GA-treated and untreated control groups were carried out using an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test in SPSS Statistics software (Version 24 SPSS Inc.). A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Graphs were created using Microsoft Excel (Version 2507).

-

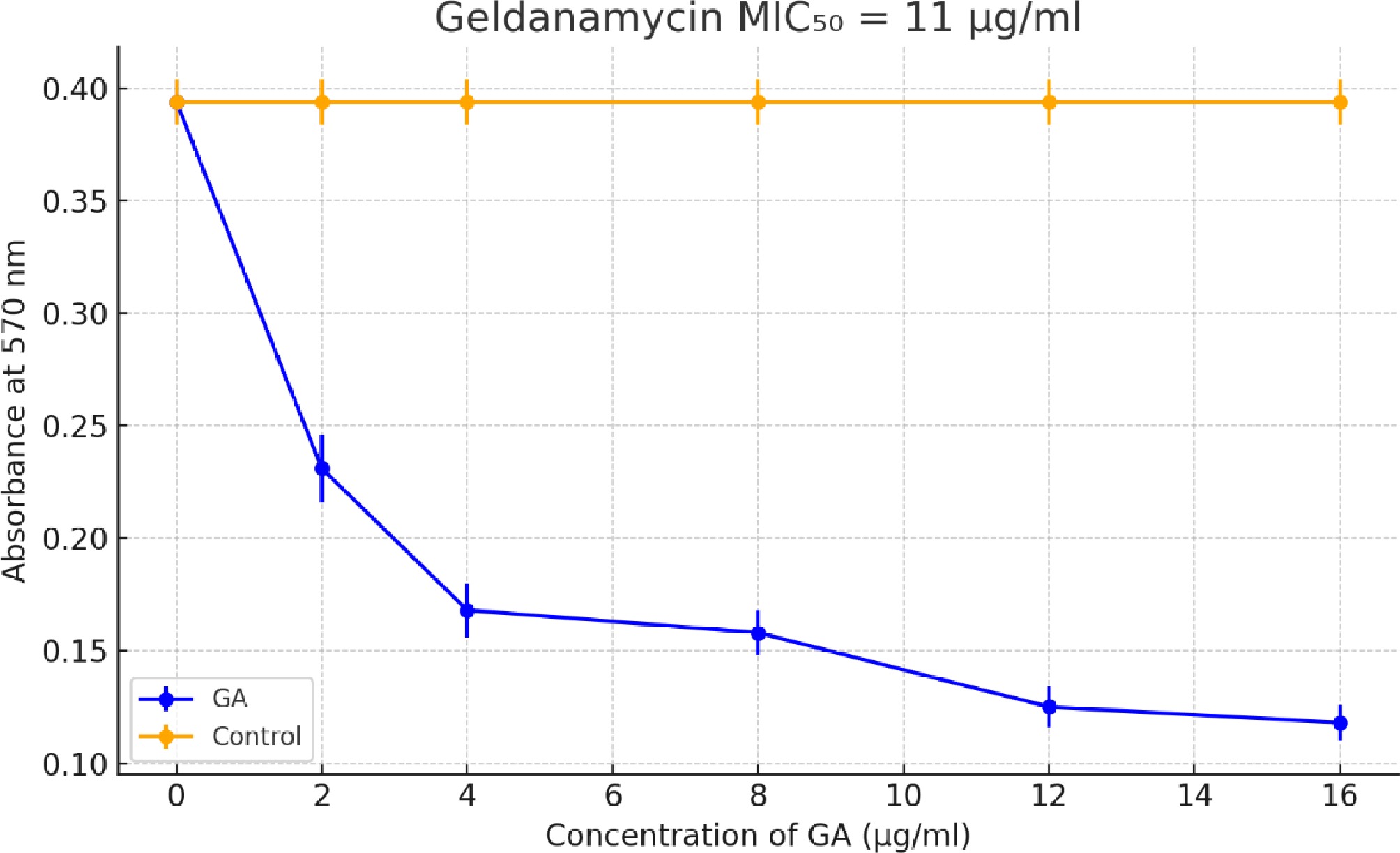

The MIC50 is the lowest concentration of the drug that inhibits the growth of 50% of the fungal cells. GA exhibited dose-dependent inhibition of fungal metabolic activity, with a calculated MIC50 of approximately 11 µg/mL[27,28] (Fig. 1). The assay was performed using four replicates per concentration and confirmed in two independent experiments. These results were used to select the working concentration of GA for subsequent assays, including the mycelial growth and gene expression analyses.

Figure 1.

Determination of MIC50 for GA against A. terreus using the MTT assay. The plot shows absorbance at 570 nm versus the GA concentration (2–16 µg/mL). Each concentration was tested in four replicates. GA treatment led to a dose-dependent reduction in metabolic activity. The MIC50 value was estimated to be ~11 µg/mL. Error bars represent the standard deviation (SD).

Mycelial growth inhibition

-

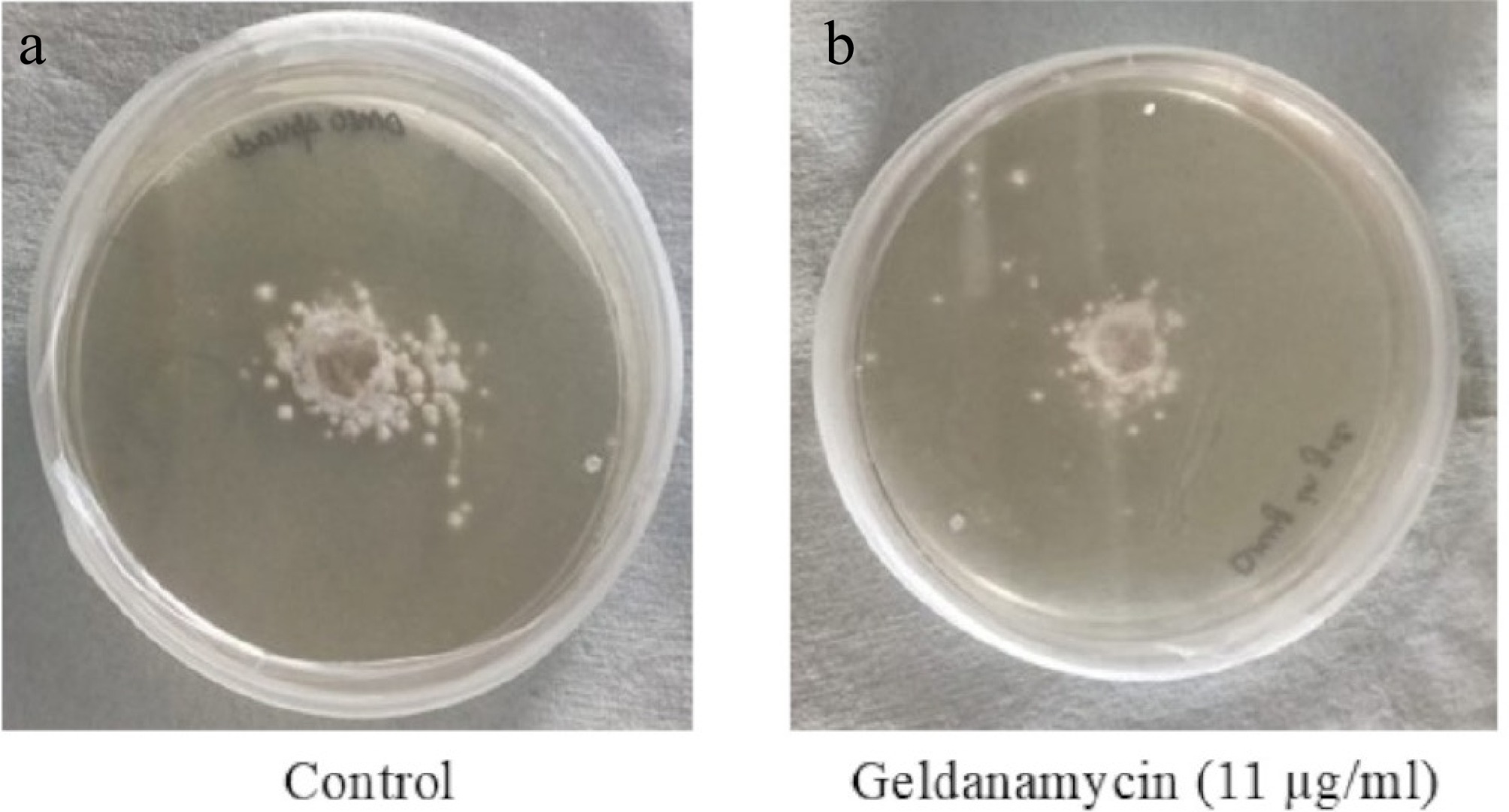

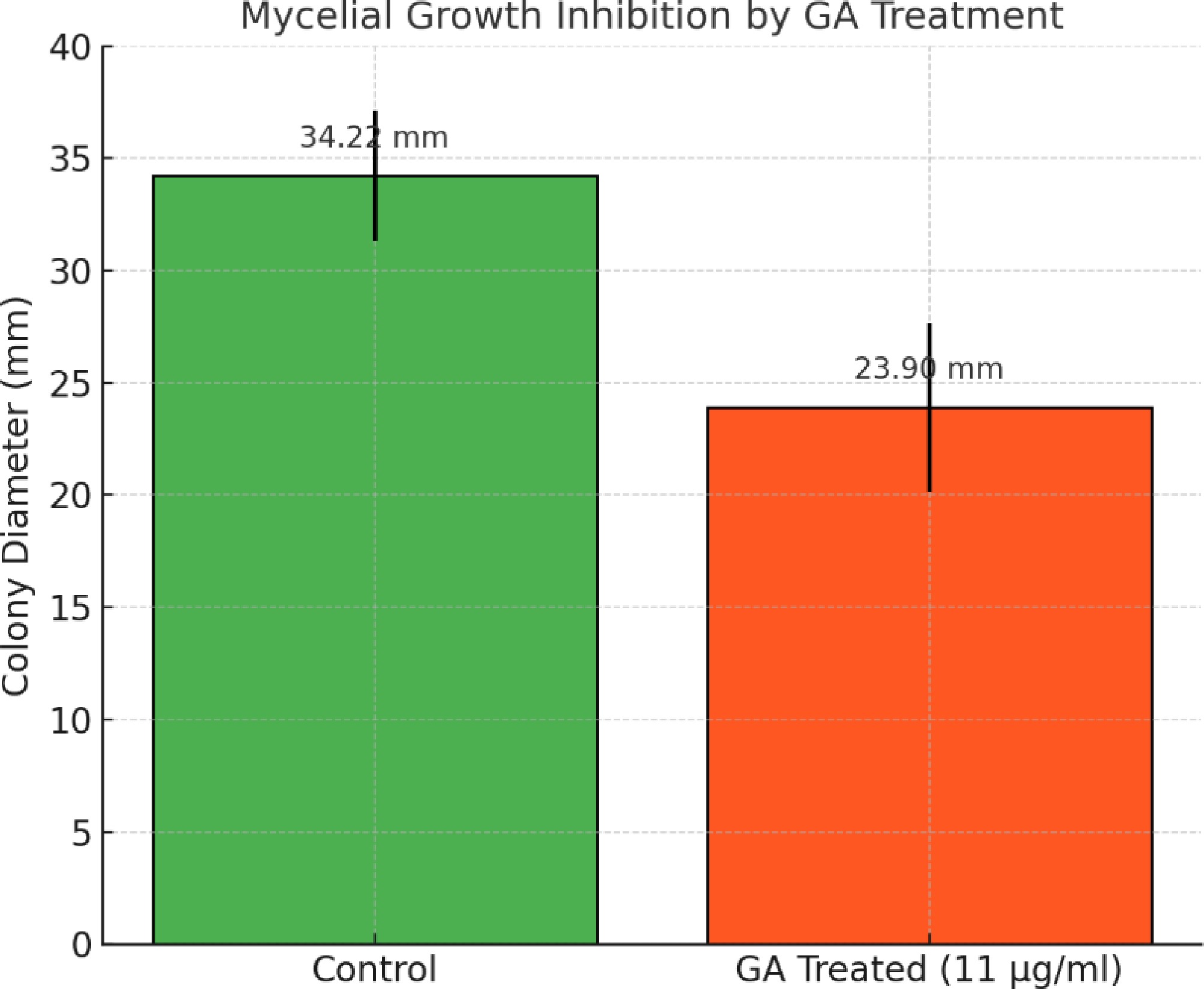

GA treatment significantly inhibited the radial mycelial growth of A. terreus (Fig. 2). The average colony diameter on GA-treated plates (11 µg/mL) was 23.90 ± 3.76 mm, whereas the untreated control colonies grew to 34.22 ± 2.89 mm. This represents a 30.14% inhibition of mycelial growth, which was statistically significant (p = 0.0048, Student's t-test) (Fig. 3). These findings corroborate the antifungal activity of GA observed in the MTT assay.

Figure 2.

Mycelial growth of A. terreus on PDA plates after 24 h of incubation. (a) Control (drug-free); (b) treated with GA (11 µg/mL). Images were analyzed using ImageJ to determine colony diameters. Treated cultures showed reduced radial growth compared with the untreated controls.

Figure 3.

Quantitative analysis of mycelial growth inhibition in A. terreus upon treatment with GA. Average colony diameters were measured after 24 h of incubation on GA-treated (11 µg/mL) and control PDA plates. Error bars represent the standard deviation (n = 4). GA treatment significantly reduced mycelial growth (p = 0.0048, Student's t-test).

qRT-PCR analyses

-

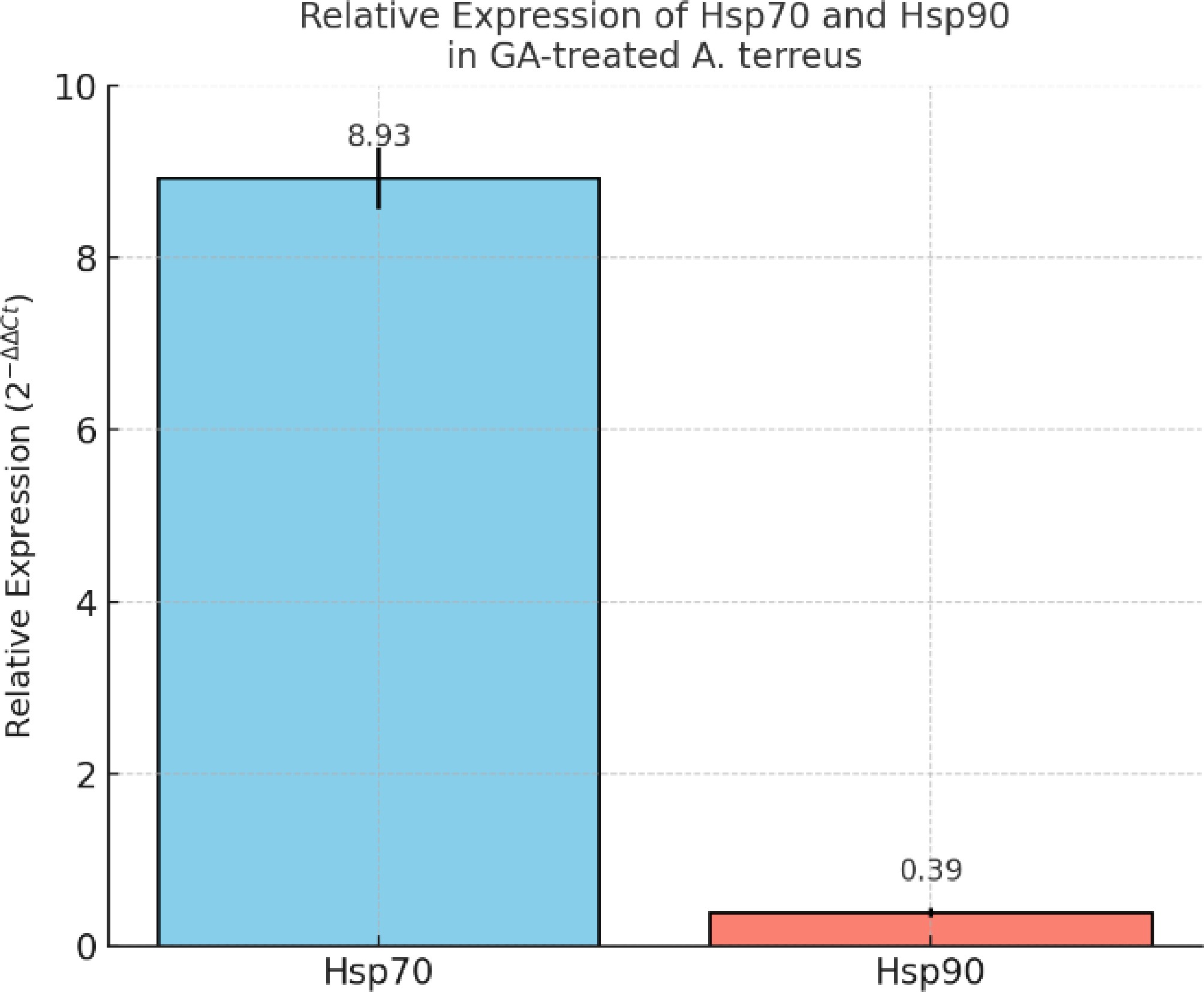

According to our proteomic analysis, key genes encoding Hsp70 and Hsp90 were selected to validate their expression profiles under GA treatment in A. terreus. The qRT-PCR assay revealed that the transcript level of Hsp70 was significantly upregulated (~8.93 ± 0.36-fold), whereas Hsp90 was markedly downregulated (~0.39 ± 0.05-fold) compared with the untreated controls (Fig. 4). These results were calculated using the 2–ΔΔCt method and normalized to the stable expression of the 40S ribosomal S1 reference gene (Ct variation < 1). These findings suggest that GA disrupts the fungal Hsp network by enhancing Hsp70's expression while repressing Hsp90, thereby contributing to dysregulation of the stress response and potential antifungal activity[50].

Figure 4.

Relative expression of Hsp70 and Hsp90 genes in GA-treated A. terreus as determined by qRT-PCR. The data were normalized to the 40S ribosomal S1 gene using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method. Expression of Hsp70 was significantly upregulated (~8.93 ± 0.36), whereas Hsp90 was downregulated (~0.39 ± 0.05) in response to the GA treatment. Bars represent the mean ± standard deviation from three biological replicates.

ROS assay

-

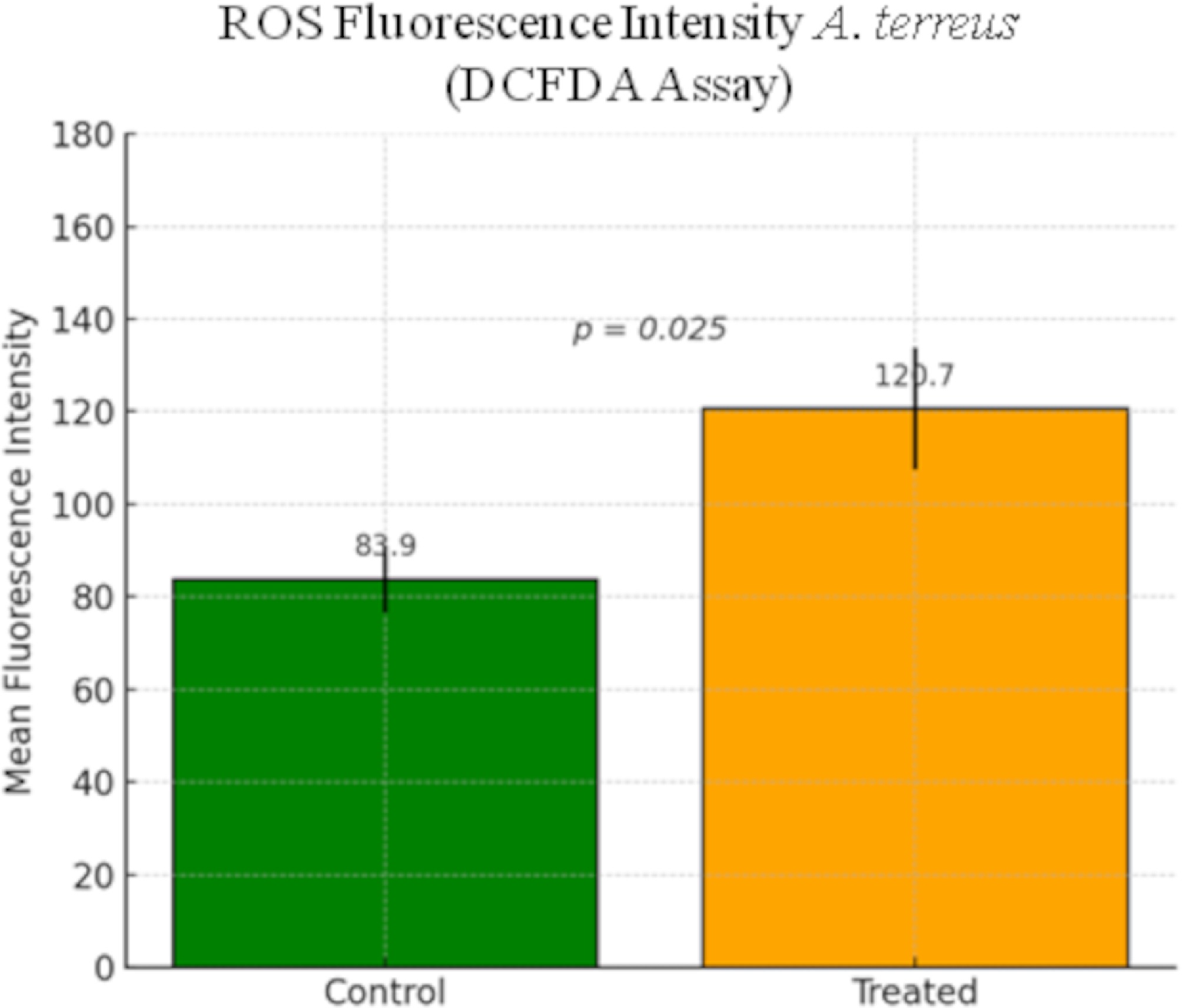

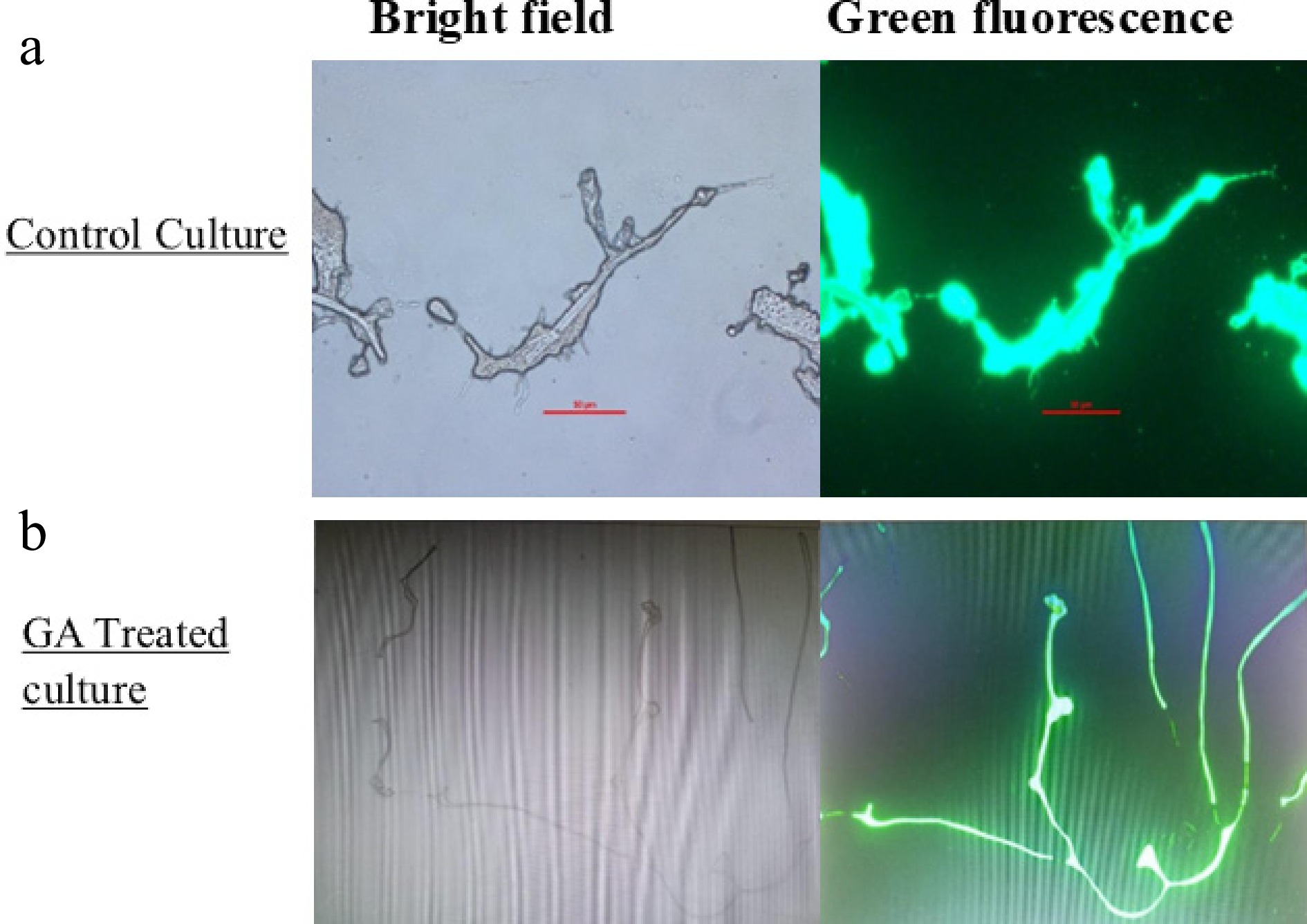

Intracellular ROS levels in A. terreus were quantitatively assessed after the GA treatment. ImageJ analysis revealed a significant increase in mean fluorescence intensity in the GA-treated group (120.67 ± SEM) compared with the control group (83.94 ± SEM) (Fig. 5). This difference was statistically significant (p = 0.025), indicating that GA induces oxidative stress in A. terreus, contributing to its antifungal activity. Figure 6a, b displays representative fluorescence and bright-field images of the control and treated cultures. These findings confirm ROS accumulation as a possible mechanism of action of GA in fungal inhibition[28].

Figure 5.

Quantification of intracellular ROS levels in A. terreus after GA treatment using the DCFDA assay. Mean fluorescence intensity was measured using ImageJ software in the control and treated regions of interest (ROIs). Bars represent the mean ± SEM. ROS levels were significantly elevated in GA-treated cells compared with the untreated controls (p = 0.025).

Figure 6.

Bright-field and green fluorescence images depicting intracellular ROS accumulation using the DCFDA assay in A. terreus. (a) Control; (b) treated with GA for 24 h.

Molecular docking

-

LGA with 100 independent runs for ligands was used to get the best docking conformations[51]. For each receptor–ligand complex, the conformation with the lowest binding energy and a favorable cluster population was selected as the best position[42,48]. Each docking simulation resulted in 100 conformations and was clustered with a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 2.0 Å. The ligands were embedded within the active site of the corresponding target protein. The formation of hydrogen bonds was observed in order to analyse the establishment of the active site of the target protein[52,53]. All four compounds tested in this study formed hydrogen bonds between the ligand atoms and amino acid residues of the target binding site (Table 2).

Table 2. Summary of molecular docking parameters for GA with Hsp proteins.

No. Energies Hsp70 Protein 6 Homo sapiens Hsp70

A. terreusHsp90α Homo sapiens Hsp90

A. terreus1 Lowest binding energy (kcal/mol) −6.75 −6.83 −7.37 −7.17 2 Estimated Ki (µM) ~11.9 ~9.90 ~3.84 ~5.43 3 Most populated cluster Cluster 9 (13) Cluster 2 (68) Cluster 23 (18) Cluster 5 (21) 4 Mean binding energy of best cluster –5.74 –6.43 –6.81 –6.64 5 Ligand efficiency −0.17 −0.17 −0.18 −0.18 6 Inter mol energy −8.54 −8.62 −9.16 −8.96 7 Torsional energy 1.79 1.79 1.79 1.79 8 RMSD to reference position (Å) ~0.20–1.4 ~0.24–1.3 ~0.26–1.1 ~0.27–1.2 In addition to the binding energy, ligand efficiency, torsional energy, intermolecular energy, RMSD, cluster occupancy, and predicted inhibition constant (Ki) were considered to evaluate the binding performance of GA across all targets.

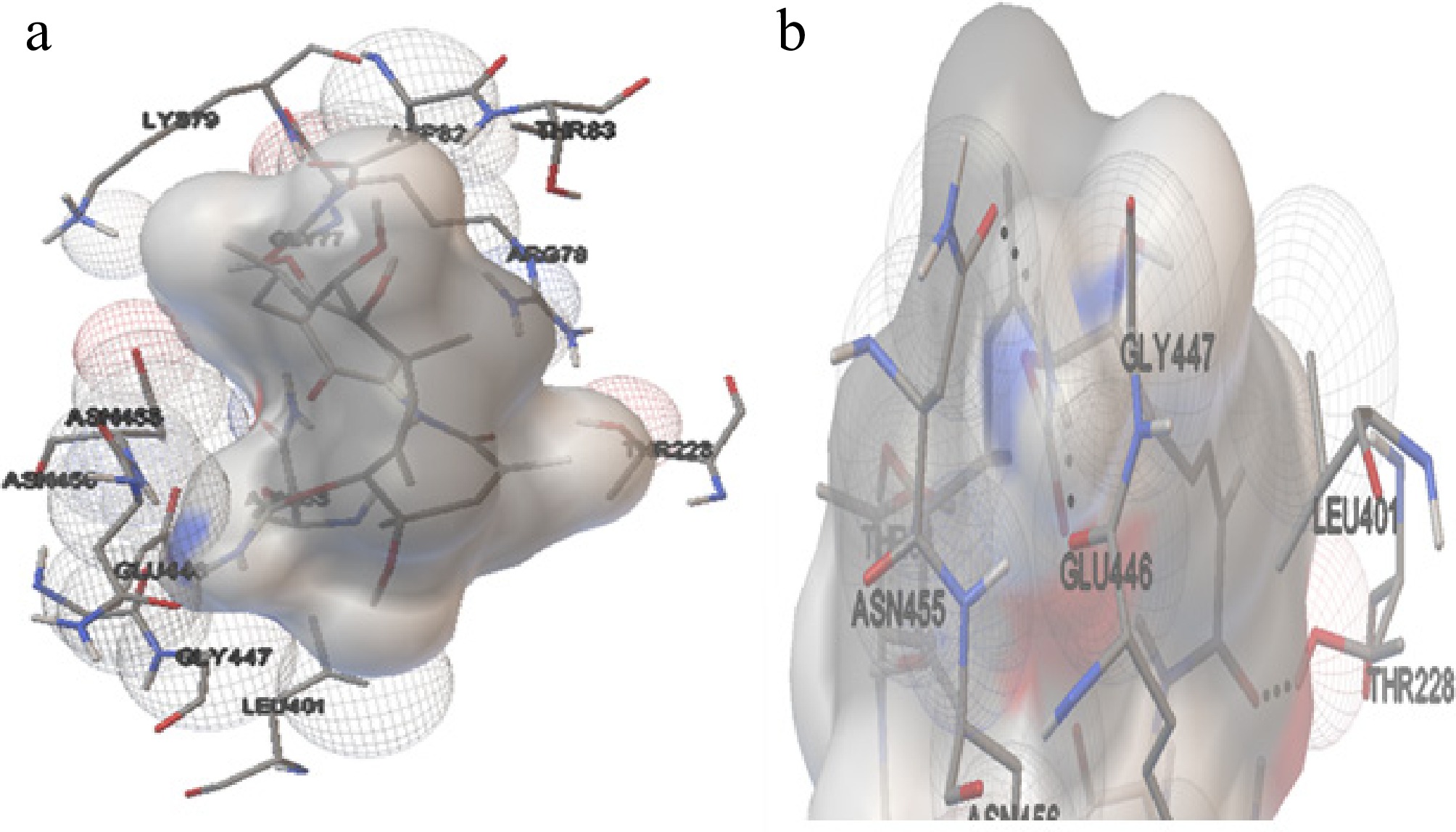

The molecular docking position of GA with Hsp70 (Homo sapiens) (Cluster 9, Run 80) in Fig. 7 revealed the formation of three hydrogen bonds. These bonds were observed at distances of 2.211, 1.8, and 2.17 Å, involving the ligand atoms H79 and H80, as well as the protein atom HG1 of Thr228. The amino acids from the protein involved in these interactions include Gly77, Arg78, Lys79, Asp82, Thr83, Asn153, The228, Leu401, Glu446, Gly447, Asn455, and Asn456. These residues likely contribute to the stabilisation of the ligand within the binding site of Hsp70[54].

Figure 7.

The interaction of Hsp70 with GA. (a) The amino acids interacting with the ligand molecule (GA) and Hsp70 of H. sapiens. (b) The dashed black line represents the three hydrogen bonds during the interaction.

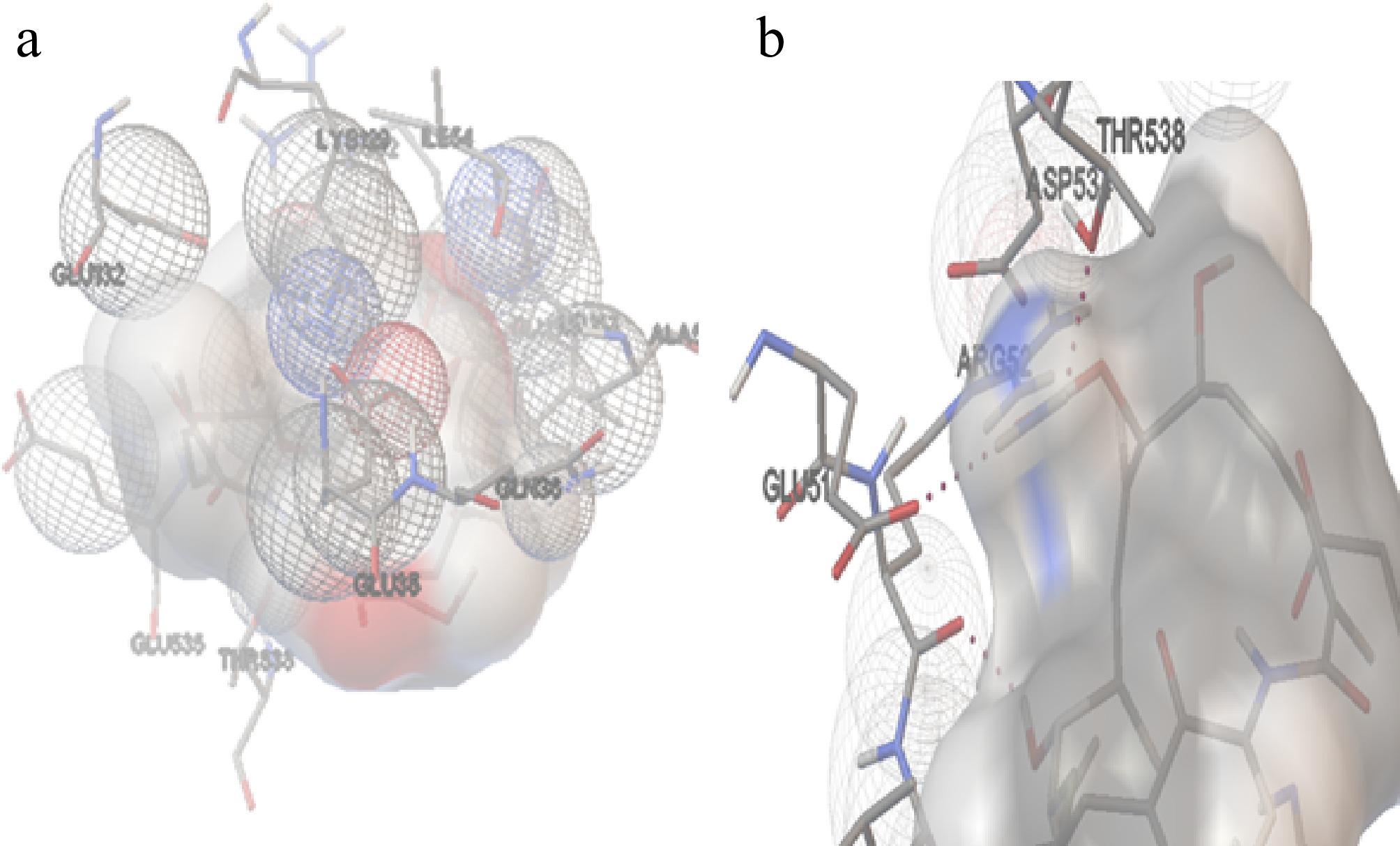

The molecular docking position of GA with Hsp70 (A. terreus) (Cluster 2, Run 42) in Fig. 8 revealed the formation of three hydrogen bonds. The hydrogen bond interactions were observed at distances of 2.101, 2.12, and 1.803 Å, involving ligand atoms H79, H80, and H56, respectively. The amino acids from the protein involved in these interactions include Glu35, Gln36, Glu51, Arg52, Leu53, Ile54, Ala57, Lys129, Glu132, Asp534, Glu535, and Thr538. These residues likely contribute to the stabilisation of the ligand within the binding site of Hsp70.

Figure 8.

The interaction of Hsp70 with GA. (a) The amino acids interacting with the ligand molecule (GA) and Hsp70 of A. terreus. (b) The dashed black line represents the three hydrogen bonds during the interactions.

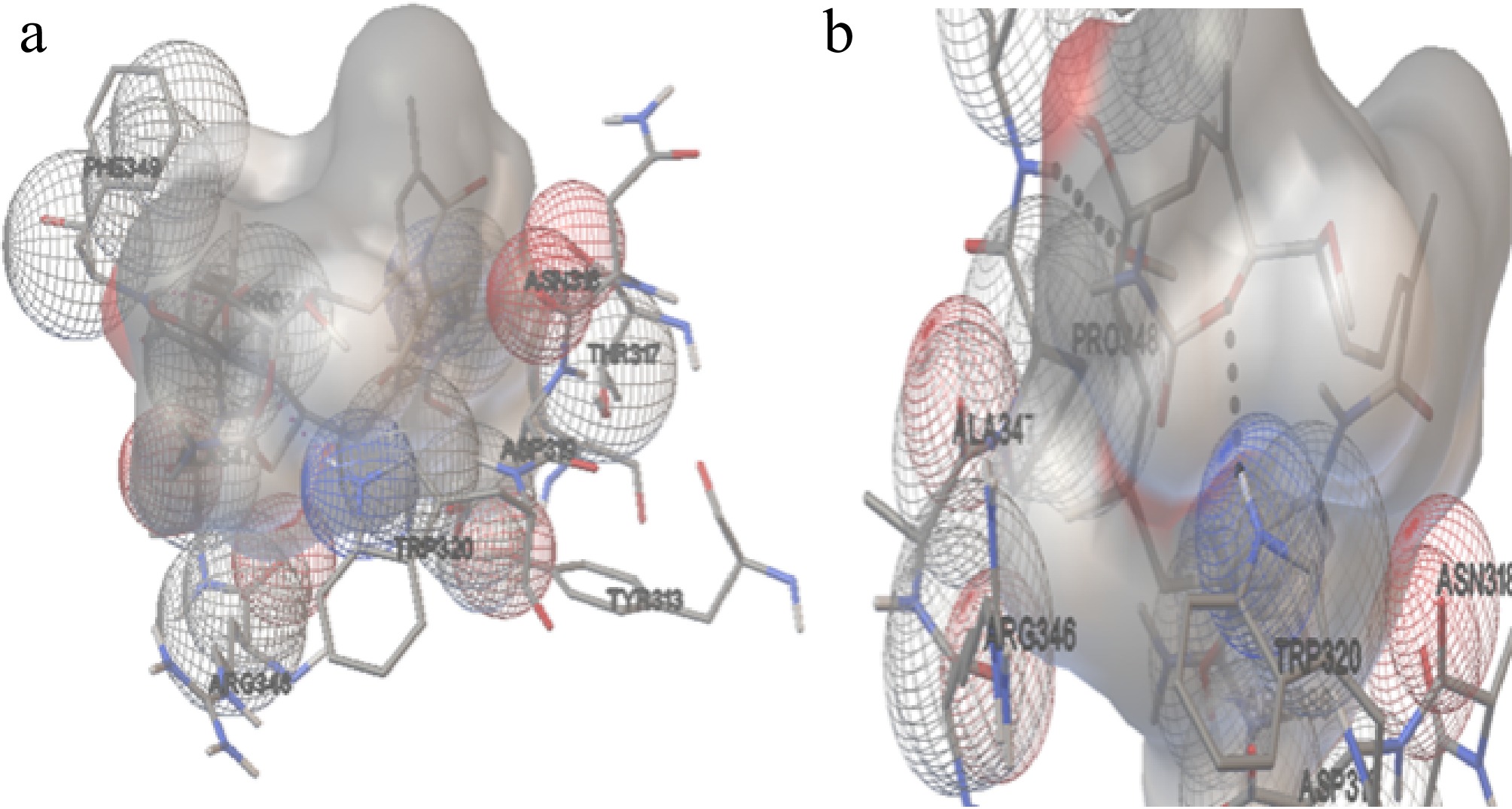

The molecular docking position of GA with Hsp90α (H. sapiens) (Cluster 1, Run 78) in Fig. 9 revealed the formation of two hydrogen bonds. These bonds were observed at distances of 2.094 and 2.12 Å, involving the protein atoms HE1 of Trp320 and HN1 of Phe349, respectively. The amino acids involved in additional interactions with the ligand include Tyr313, Thr317, Asn318, Asp319, Trp320, Arg346, Ala347, Pro348, Phe349, and Arg396. These residues likely contribute to the stabilisation of the ligand within the binding site of Hsp90.

Figure 9.

The interaction of Hsp90 with GA. (a) The amino acids interacting with the ligand molecule (GA) and Hsp90 of H. sapiens. (b) The dashed black line represents the two hydrogen bonds during theinteractions.

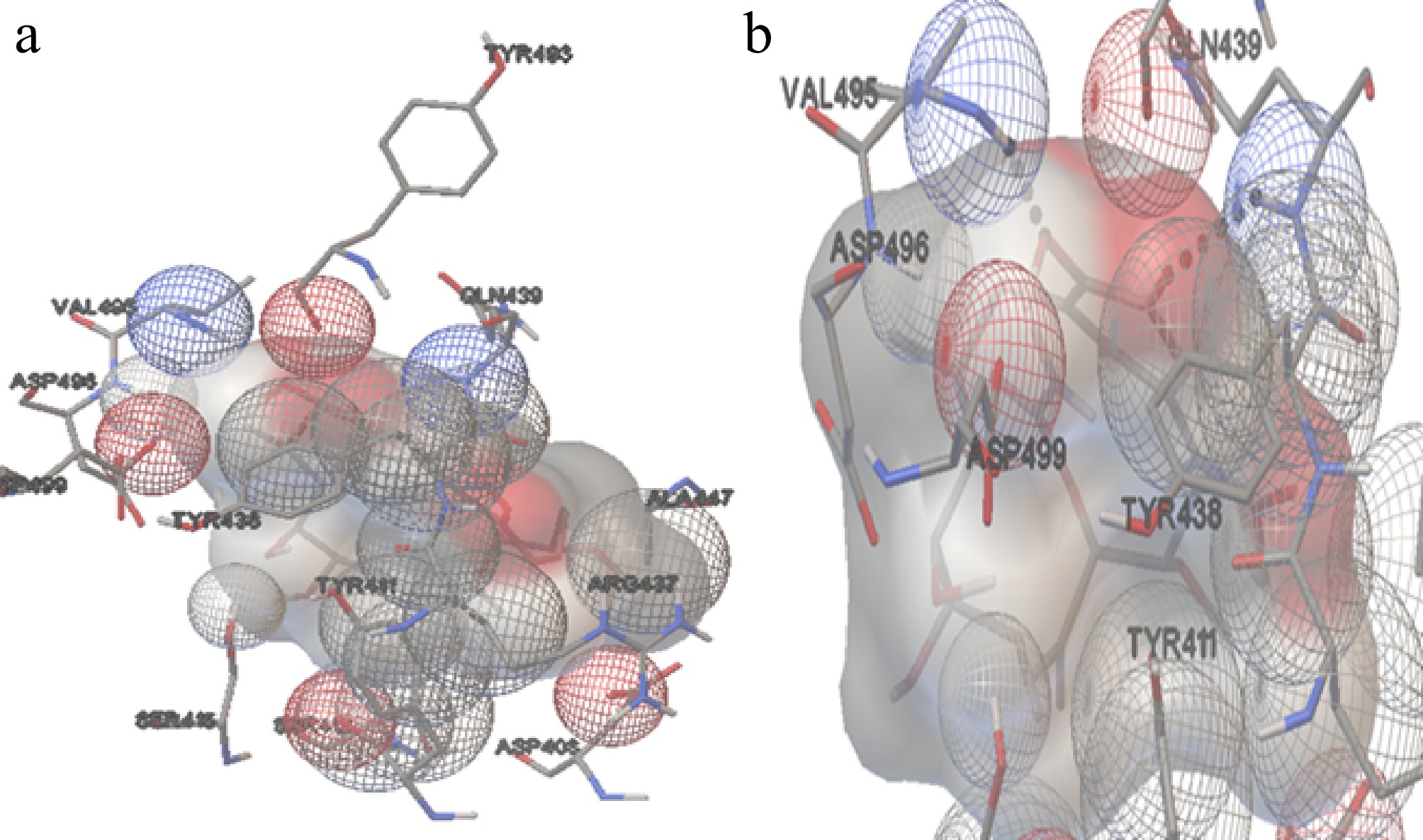

The molecular docking position of GA with Hsp90 (A. terreus) (Cluster 1, Run 65) in Fig. 10 revealed the formation of two hydrogen bonds. The hydrogen bond interactions were observed at distances of 2.193 and 1.986 Å, involving theligand atoms HN of Gln439 and HN of Val495, respectively. The amino acids from the protein involved in these interactions include Asp408, Tyr411, Ser413, Ser415, Arg437, Tyr438, Gln439, Ala477, Tyr493, Val495, Asp496, and Asp499. These residues likely contribute to the stabilisation of the ligand within the binding site of Hsp90.

-

The emergence of A. terreus as a clinically relevant opportunistic pathogen, particularly in immunocompromised individuals, presents a major therapeutic challenge because of its inherent resistance to amphotericin B and increasing resistance to other antifungal classes. In this study, we examined the antifungal potential of GA, a known Hsp90 inhibitor, and investigated its molecular mechanism of action against A. terreus through a combination of in vitro, molecular, and in silico approaches. Our findings demonstrate that GA exhibits significant antifungal activity, with an MIC50 of approximately 11 µg/mL, as determined via an MTT assay with four technical replicates per concentration and two independent experiments. The growth inhibition was dose-dependent, with consistent suppression of fungal viability across increasing drug concentrations. These data informed subsequent mycelial inhibition experiments and gene expression studies, indicating its effectiveness in inhibiting the growth of A. terreus. The mycelial growth assay showed a statistically significant reduction in colony diameter following the GA treatment. Plates supplemented with 11 µg/mL GA exhibited a 30.14% reduction in radial mycelial growth compared with the untreated controls (p = 0.0048), measured using ImageJ. These results strongly support the antifungal potential of GA and align with the metabolic inhibition observed in the MTT assay.

To understand the molecular response of A. terreus to GA, we assessed the expression of key Hsps using qRT-PCR. Clear transcriptional dysregulation was observed. Hsp90 was significantly downregulated (~0.39-fold), whereas Hsp70 expression was markedly upregulated (~8.93-fold). This differential expression suggests a stress-induced compensatory mechanism, with the induction of Hsp70 possibly attempting to counterbalance Hsp90's loss of function. These findings provide further evidence that GA disrupts the fungal Hsp network, a critical system for protein homeostasis and stress tolerance in pathogens. Oxidative stress, a hallmark of cellular dysfunction, was evaluated through DCFDA-based ROS quantification. GA treatment resulted in significantly elevated ROS levels (p = 0.025), as visualised and quantified through fluorescence microscopy and ImageJ analysis. This ROS accumulation may contribute to fungal cell death by inducing oxidative damage, supporting GA's antifungal efficacy beyond its chaperone inhibition[28].

Molecular docking studies further supported the antifungal mechanism by demonstrating the strong and stable binding of GA with Hsp70 and Hsp90 of both A. terreus and H. sapiens. The lowest binding energies were observed for the Hsp90α of H. sapiens (–7.37 kcal/mol) and Hsp90 of A. terreus (–7.17 kcal/mol), indicating the favorable thermodynamics of the interactions. Hydrogen bond analyses revealed specific residues involved in stabilising GA within the active sites, including Trp320 and Phe349 in human Hsp90 and Gln439, and Val495 in fungal Hsp90. Additionally, most populated clusters, such as Cluster 23 (18 members) for human Hsp90 and Cluster 5 (21 members) for fungal Hsp90, confirmed the convergence of the docking positions, strengthening confidence in the predicted interactions. Information entropy (0.64) and RMSD values within the clusters also indicated structural consistency. Collectively, these findings suggest that GA has a strong affinity toward fungal Hsp targets, reinforcing its proposed mechanism of action. These antifungal effects are further complemented by GA's well documented anticancer activity, as shown in previous studies involving non-small-cell lung cancer and breast cancer[55,56]. The inhibition of oncogenic pathways (e.g., EGFR [epidermal growth factor receptor], AKT [AKT serine-threonine protein kinase family], HER2 [human epidermal growth factor receptor 2])[57,58] and destabilisation of signaling proteins through Hsp90 blockade positions GA as a dual-action therapeutic agent. Moreover, in the context of fungal infections like invasive aspergillosis, where traditional therapies may fail, GA offers a promising alternative with both antifungal and anticancer capabilities. Taken together, our study highlights the therapeutic relevance of targeting Hsps in A. terreus, especially in immunocompromised patients who may simultaneously face fungal infections and malignancies[59]. However, the known cytotoxicity of GA in mammalian systems must be addressed in future studies through structural modifications or delivery optimisations to improve its therapeutic index.

-

This study establishes GA as a potent antifungal agent against A. terreus, demonstrating an MIC50 of 11 µg/mL, significant inhibition of mycelial growth, ROS induction, and transcriptional downregulation of Hsp90. The combined in vitro and molecular docking analyses confirm GA's strong interaction with Hsps, thereby supporting its mechanism of action. Given its dual antifungal and anticancer properties, GA represents a promising candidate for therapeutic development, particularly for immunocompromised individuals with concurrent fungal and oncologic conditions. However, further research is warranted to explore the safety profile of GA, its pharmacodynamics, and the potential for synergistic drug combinations. Targeting the machinery of Hsps may pave the way for more effective strategies against resistant fungal pathogens like A. terreus.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Neha, Shankar J; study conduction: Neha; materials or analytical tools collection, supervision: Shankar J; draft manuscript preparation: Neha, Shishodia SK, Shankar J. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

We are thankful to the Department of Biotechnology & Bioinformatics, Jaypee University of Information Technology, Solan, HP, for providing facilities and to Department of DBT Gol (Biotechnology, Government of India) for the financial assistance provided to Neha.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Neha, Shishodia SK, Shankar J. 2025. Efficacy of the Heat shock protein-90 inhibitor geldanamycin against Aspergillus terreus. Studies in Fungi 10: e028 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0029

Efficacy of the Heat shock protein-90 inhibitor geldanamycin against Aspergillus terreus

- Received: 20 February 2025

- Revised: 24 August 2025

- Accepted: 05 October 2025

- Published online: 10 December 2025

Abstract: Aspergillus terreus is increasingly recognised as a pathogen in individuals with compromised immune systems. Given its inherent resistance to amphotericin B and development of resistance to azoles, echinocandins, and other antifungal treatments, the current study investigates the efficacy of geldanamycin (GA), a Heat shock protein (Hsp) 90 inhibitor, against A. terreus, highlighting its potential as a dual-action therapeutic agent for both fungal infections and cancer. Using the [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] (MTT) and food poison technique, the 50% minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC50) of GA was calculated and its antifungal properties were assessed against A. terreus. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was used to study the expression profile of Hsp90 and Hsp70 during the treatment, whereas reactive oxygen species were estimated using the fluorescent probe dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFDA). Molecular docking using AutoDockTools was carried to assess GA's interaction with Hsp70 and Hsp90 proteins. GA exhibited potent antifungal activity with an MIC50 of 11 µg/mL. A 30.14% reduction in mycelial growth was observed in GA-treated plates compared with the untreated controls. The qRT-PCR analysis revealed significant downregulation of Hsp90 (~0.39-fold) and upregulation of Hsp70 (~8.93-fold) in response to treatment. GA also induced a notable increase in intracellular ROS levels. Molecular docking confirmed stable binding of GA to both Hsp90 and Hsp70, with multiple hydrogen bonds contributing to its high affinity and specificity. These findings highlight the promising antifungal potential of GA against A. terreus, likely mediated through Hsp disruption and oxidative stress induction. Given its established anticancer properties, GA represents a candidate for dual-action therapy. However, its known cytotoxicity warrants further studies to optimize its safety and therapeutic efficacy.

-

Key words:

- Aspergillus terreus /

- Geldanamycin /

- Heat shock proteins /

- Resistance /

- Minimal inhibitory concentration /

- qRT-PCR /

- Molecular docking