-

Water contamination represents a significant and persistent issue that has influenced human civilization throughout the ages. Unquestionably, it has a negative influence on the health and well-being of billions of people worldwide, contributing to the rise of several diseases like cancer, diarrhea, and cholera[1,2]. Organic dyes can hinder plant growth, enter the food chain, resist degradation, and accumulate in organisms, posing risks of toxicity, mutations, and cancer[1,2]. Furthermore, the contamination of water sources has been associated with detrimental impacts on essential organs, including the liver, kidneys, brain, lungs, and skin[1,2]. Wastewater contains many dangerous and infectious pollutants such as radioactive materials, insecticides, heavy metal ions, and dyes[3,4]. Wastewater pollution is predominantly attributed to organic dyes sourced from various sectors, including paint, coating, paper and pulp, leather, food, pharmaceuticals, and textiles[5,6]. The harmful effects of leftover dyes, especially from the textile industry, make them some of the most dangerous pollutants to ecosystems. High levels of these artificial dyes in water bodies affect their appearance, lower oxygen levels, and increase the need for oxygen in living organisms[6]. The adoption of economically sustainable and efficient strategies for removing toxic dyes from wastewater is imperative, given their profound impact on human health, and the safeguarding of aquatic habitats[7]. To successfully remove dyes from wastewater and aquatic solutions, different approaches have been widely employed, including chemical oxidation, oxidative degradation, ozonation, electrochemistry, microbial degradation, membrane separation, photo-catalysis, nano-filtration, micro-filtration, coagulation, and adsorption[8−17].

The WHO indicates that textile dyeing processes contribute to 17%–20% of industrial contaminants in the water. Roughly 80% of azo pigments find application in the coloration of textiles, while 10%–15% are discharged into wastewater without adhering to the fiber[18,19]. The suboptimal degradation efficacy of cationic dyes through traditional biochemical methods can be ascribed to the existence of aromatic rings in their molecular architecture[20]. Basic blue 3 (BB3) is a solid, crystalline, cationic dye. BB3 is frequently utilized in the textile sector for silk, acrylic blended fabric, dyeing wool, and direct printing on acrylic carpets[21,22]. Nevertheless, BB3 dye is linked to both environmental and human health concerns. Being exposed to the dye can result in cancer, genetic mutation, acute toxicity when inhaled, and eye and skin irritation[23]. Inadequate dyeing processes, low attachment, incomplete dye absorption, wastage, and inadequate hue fastness lead to the release of highly pigmented wastewater, causing severe pollution in aquatic ecosystems. Therefore, humanity as a whole has made the removal of persistent dyes like BB3 a top priority to safeguard the environment, and ensure the well-being of human health. The selection of BB3 as a test sample dye for the present adsorption investigations stems from its associated health risks and its structural composition, characterized by aromatic rings that render it resistant to degradation through conventional methods.

Activated carbon is extensively utilized as an adsorbent across multiple wastewater treatment applications. The material exhibits a significantly enhanced level of porosity, showcasing a substantial internal surface area and demonstrating commendable mechanical strength[24−26]. Even though it's extensive utilization across various industries, activated carbon continues to be a material of considerable cost. Hence, it becomes imperative to conduct an in-depth exploration and advancement of cost-efficient carbon materials that can be effectively utilized for the purpose of mitigating water pollution. A diverse range of cost-effective materials has been employed for the purpose of extracting BB3 from aquatic solutions. These materials encompass Hevea brasiliensis seed coat, silybum marianum stem, waste ash, persea americana nuts, cedar sawdust, carbon-silica composite, sugar cane bagasse, and macadamia seed husks[27−34]. Many researchers are interested in this low-cost adsorption approach because it doesn't require a sophisticated regeneration methodology. Euryale ferox is a plant that thrives in tropical and subtropical climates. It is a well-known agricultural by-product, commonly referred to as Makhana. This aquatic herb belongs to the water lily family (Nymphaeaceae). Although E. ferox originated in the East Indies, it has long been widely cultivated all over the world. Traditional medicine has widely used E. ferox to treat a variety of ailments, such as excessive leucorrhoea, chronic diarrhea, and kidney problems[35]. Despite the abundance of E. ferox, their shells have historically been utilized as fuel. A recent study has discovered a new use for E. ferox shells in the production of activated carbon. This involves utilizing ZnCl2, KOH, and H3PO4 as chemical activation agents[36−41].

Although numerous studies address the removal of BB3 from aqueous solutions, they exhibit constraints regarding adsorption capacity and pose considerable difficulties in the restoration process[27−34]. Furthermore, the unique combination of high porosity and superior surface chemistry positions this FNAC as a versatile and sustainable material for environmental remediation (dye removal). This study seeks to assess the efficacy of FNAC in removing the basic blue 3 (BB3) dye from wastewater. The investigation of FNAC properties involves the utilization of numerous analytical techniques, including FTIR, BET, and SEM. The investigation encompassed an examination of the impact of different operating parameters, including contact duration, initial BB3 concentration, FNAC dose, temperature, and pH of the solution. The investigation focused on studying adsorption isotherms, employing various adsorption models such as the Langmuir and the Freundlich. Additionally, kinetic approaches were employed to evaluate the experimental findings and enhance understanding of the adsorption dynamics of BB3 onto FNAC. By means of instrumental evaluations and adsorption studies, the most likely mechanistic pathway for the adsorptive elimination of BB3 utilizing FNAC is proposed. The investigation seeks to identify the optimal operating situations for the adsorptive removal of BB3 dye, aligning with the research on real-world wastewater treatment methodologies.

-

All experiments were carried out with analytical-grade reagents, and double-deionized water (DDW). BB3 (AR, Merck, India) was of utmost purity. A standard solution of 1,000 mg/L BB3 was produced in double-distilled water (DDW). NaOH (Fisher Scientific, India) and HCl (Merck, India) solutions were employed to modulate the pH employing a Systronics 361 pH meter. FT-IR spectrophotometer (IR Affinity, Shimadzu) was utilized to examine the functional groups in FNAC. Utilizing a scanning electron microscope (S4800, Hitachi, Japan), FNAC's surface morphology was observed, while the surface area of the lined-up FNAC was ascertained using the BET method.

Preparation of FNAC

-

The fox nutshell (FNS) was collected from the Hardoi district of Uttar Pradesh (India) in the month of February. After washing thoroughly with DDW, FNS was soaked in 0.4 M NaOH solution and left overnight to effectively eliminate any contaminants such as mud and ash that were present during the extracting and processing stages. Thereafter, it was thoroughly rinsed with distilled water until the pH of the rinsed solution approached approximately 7. Following a drying process at 110 °C for a duration of 20 h, the resultant residue was subjected to grinding and sieving to yield the fox nut shell powder (FNSP) of the desired particle size (100 μm). Approximately 50 g of NaOH were dissolved in 150 mL of distilled water, subsequently incorporating 20 g of FNSP at a temperature of 80 °C. The combination was permitted to rest for 24 h at ambient temperature, and was periodically stirred every 6 h. Following that, the soaked sample was dehydrated at 115 °C for 24 h in a hot oven. Carbonization of the obtained dried material was performed at 500 °C for 120 min in an electric tubular furnace tube in an N2 environment with a flow rate of 200 mL/min. Upon completion of the procedure, the carbonized material underwent an extensive rinsing process, utilizing hot deionized distilled water, followed by cold deionized distilled water, until the pH of the washing water reached neutrality. The moist substance was dehydrated in an oven for a duration of 24 h at a temperature of 110 °C, and was subsequently stored in sealed plastic bags.

BB3 adsorption experiments

-

Adsorption investigations with FNAC were carried out to discover the optimal conditions for BB3 adsorption on FNAC. For that, the calculated amount of FNAC (0.1 to 1.0 g) and 100 mL BB3 solution (100 to 500 mg/L) were carefully introduced into a 250 mL round-bottom flask. HCl or NaOH solution was deployed to maintain the pH of the reacting mixture before the addition of the adsorbent. The test solutions were agitated for 140 min at 150 rpm in a thermostatic rotator, ensuring a constant temperature of 298 K. Afterwards, the supernatant solutions obtained via centrifugation underwent filtration, and the quantification of BB3 content in each flask was accomplished utilizing a Spectronic 20D (Milton Roy Co.) visible spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 654 nm, which corresponds to the maximum absorbance (λmax) for BB3. The percentage elimination of BB3, along with the adsorption of BB3 at equilibrium and at any point of time, represented as qe (mg/g), and qt (mg/g), respectively, were determined employing Eqs (1) and (2). Each study was conducted in three separate runs.

$ {\text{%}}\;\mathrm{R}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{m}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{v}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}=\dfrac{\left({\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{o}}-{\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{e}}\right)\times \mathrm{ }100}{{\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{o}}} $ (1) $ {\mathrm{q}}_{\mathrm{e}}=\dfrac{\left({\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{o}}-{\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{e}}\right)\times \mathrm{ }\mathrm{V}}{\mathrm{m}}$ (2) The factors considered were the starting content of BB3 (Co), the quantity of BB3 at equilibrium (Ce), the volume of solution (V), and the mass of the adsorbent (m).

FNAC regeneration

-

The action of desorption, which is essentially the inverse of adsorption, involves the release of a substance that was formerly adhered to the outer layer of the adsorbent. This investigation encompassed five iterations of adsorption and desorption processes. Each cycle entailed the incorporation of 0.10 g of FNAC into a vessel that contained 100 mL of BB3 solution (500 mg/L), with the temperature meticulously regulated at 25 °C, agitation sustained at 150 rpm, and a precisely maintained pH of 6.5. The residual amounts of BB3 in the solution were evaluated following agitation. The remaining material was subjected to a thorough cleaning procedure using distilled water before being dried at 115 °C, thus permitting the next desorption investigations.

The BB3 desorption from the FNAC surface was examined using various solvents such as HCl, NaOH, methanol, and ethanol. The desorption process involved immersing the exhausted FNAC in 50 mL of various solvents, and stirring the resultant solution at 25 °C for a period of 2 h. The adsorbent underwent a cleaning procedure with distilled water to remove any remaining solvent, followed by a drying phase lasting 11 h at a temperature of 110 °C. The residual amount of BB3 was assessed subsequent to the conclusion of the desorption investigation. The effectiveness of desorption, as articulated by Eq. (3), signifies the ratio of contaminants that have been removed in relation to the initial quantity adsorbed, thus offering profound insights into the reusability and restorative potential of the activated carbon.

$ {\text{%}}\;\mathrm{D}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{p}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{n}=\dfrac{{\mathrm{M}}_{\mathrm{a}\mathrm{d}\mathrm{s}}}{{\mathrm{M}}_{\mathrm{d}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{s}}}\times 100 $ (3) The entire amount of BB3 that has been desorbed and adsorbed, measured in mg/L, is represented by Mdes and Mads, accordingly.

-

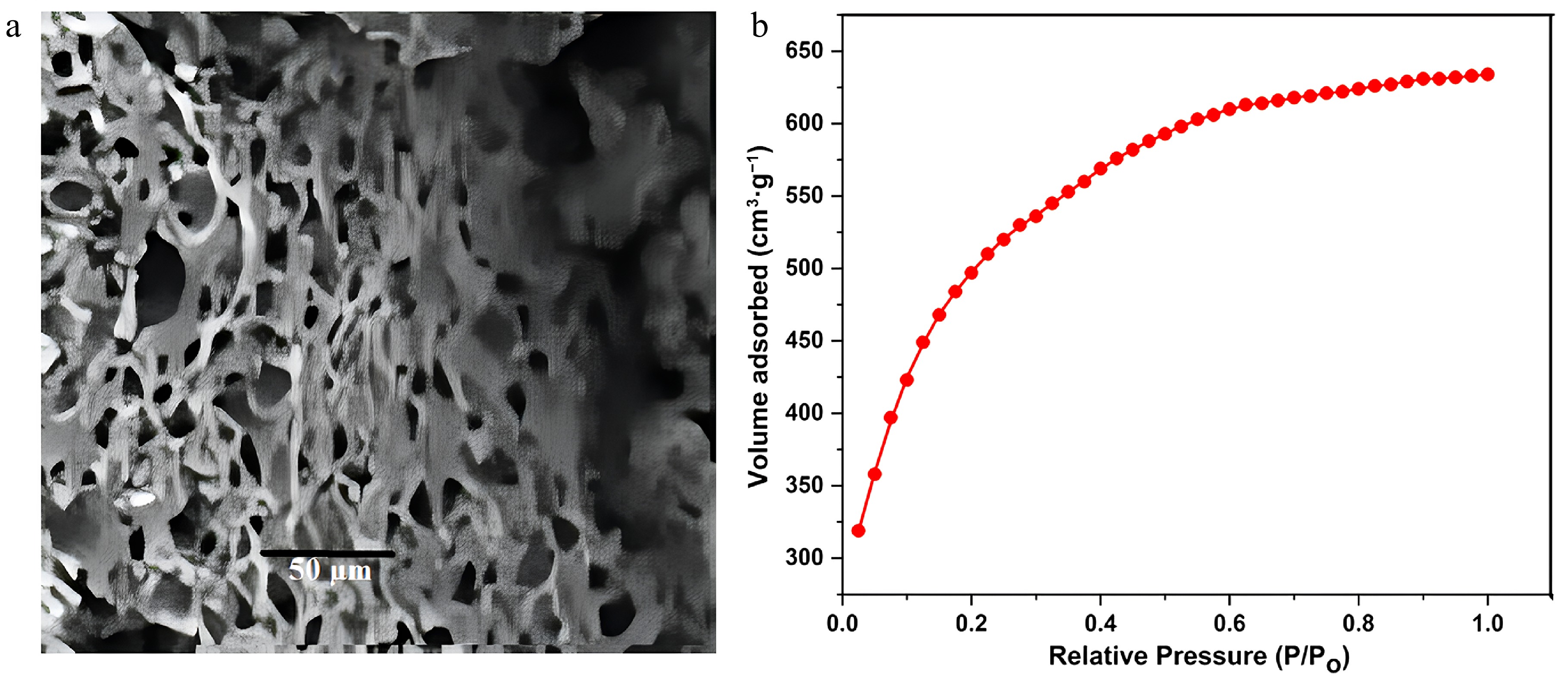

Figure 1a shows the SEM image of FNAC powder before adsorption. The image exhibits an asymmetric, rough, and porous structure. In addition, it has micro-sized active sites or cavities, indicating that FNAC powder shows great potential as an adsorbent for effectively capturing BB3. The surface area of adsorbents stands out as one of their most crucial attributes. Figure 1b represents the nitrogen adsorption isotherms for the prepared FNAC. It was discovered that FNAC had a surface area of 1,813.2 m2/g, which was comparatively large for the effective adsorption of dyes. The mean pore diameter of 2.16 nm suggests the mesoporous architecture of FNAC[36,37,42]. The average pore diameter (DP) was determined employing the formula DP = 4VT/SBET. The surface area (SBET) of the synthesized FNAC was determined using the BET method. The liquid quantities of N2 at relatively high pressure (P/Po ~0.99) were used to estimate the total pore volume (VT).

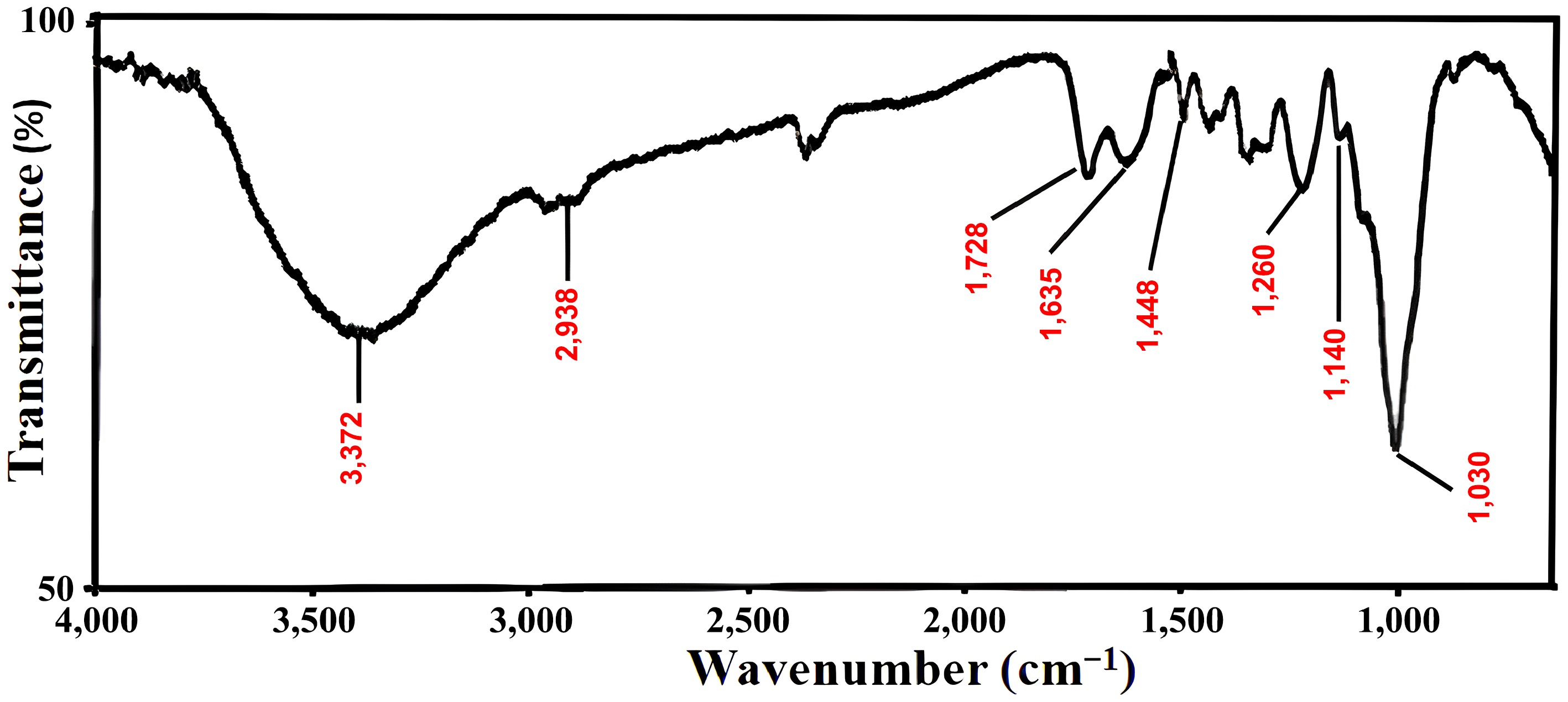

Using the KBr pellet method, the FT-IR spectra of FNAC have been scanned in the 4,000–700 cm−1 wavenumber region (Fig. 2). The FT-IR spectra of FNAC revealed that the absorbance bands had peaks at 3,372, 2,938, 1,728, 1,635, 1,448, 1,371, 1,241, 1,160, and 1,041 cm−1. Other researchers have documented the majority of these bands for various carbon compounds. A band between 3,500–3,300 cm−1 can be ascribed to -OH stretching[37,38]. A peak between 3,000–2,875 cm−1 corresponds to alkane C-H stretching. At 1,728 cm−1, the distinctive C=O stretching of the carboxylic acid group is observed[39]. Peaks at 1,635 and 1,448 cm−1 are indicative of sp2-hybrid carbon-carbon (C=C, stretching) and O–H bending, respectively[38]. A peak at 1,240, 1,160, and 1,030 cm−1 indicate C-O stretching and O-H bending vibrations of distinct functional groups (ethers, esters, and alcohols)[38]. The presence of the –COOH, C=C, C=O, and –OH functional groups indicates that there has been a considerable degree of interaction between the adsorbate and the adsorbent, which could help BB3 adsorb onto the FNAC's active sites.

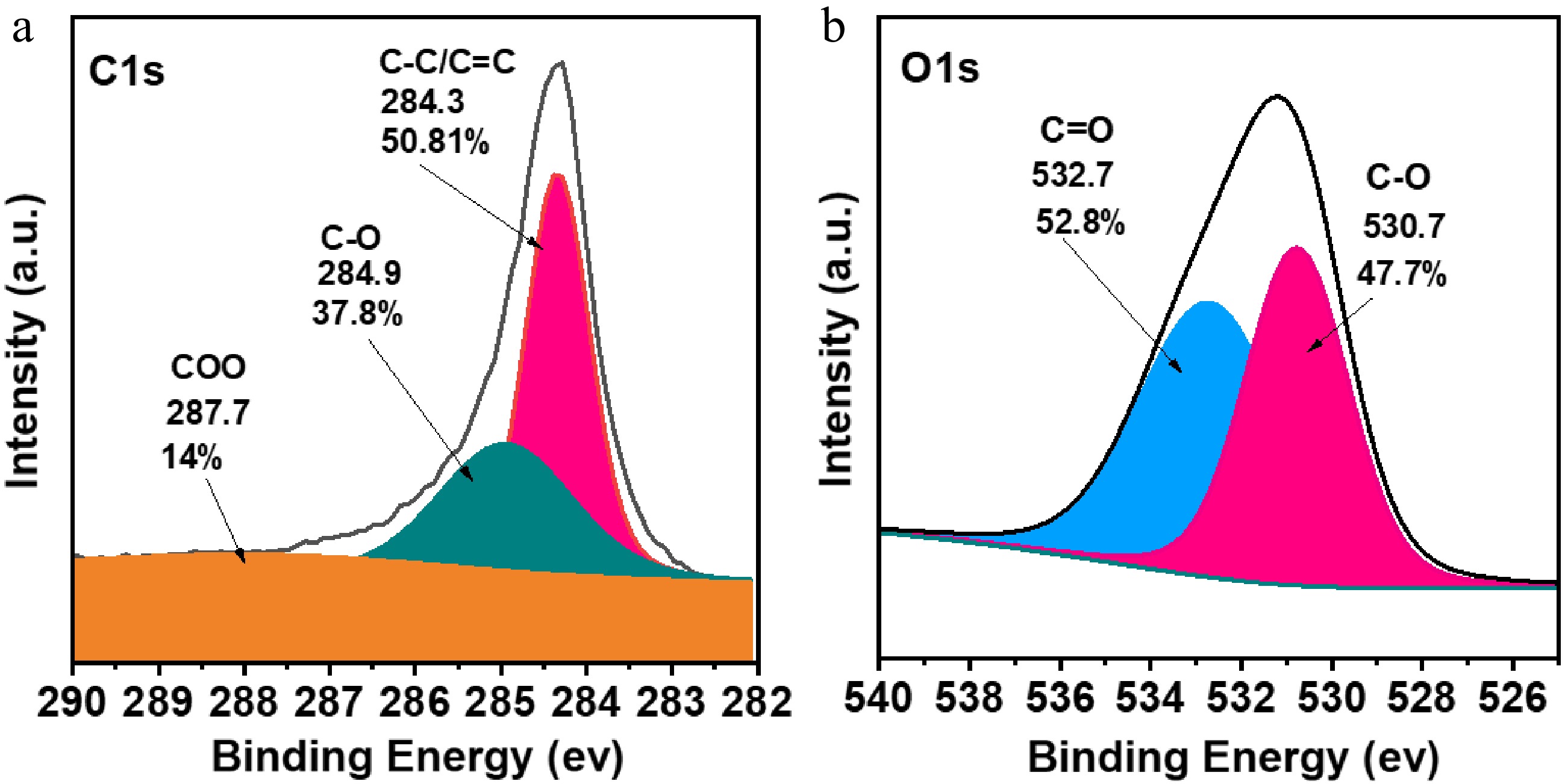

Furthermore, XPS measurement was carried out to identify the oxidation state of carbon and oxygen species in FNAC porous structures. The deconvolution of C 1s reveals three peaks corresponding to (287.7 eV; C(O)−O), (284.9 eV; C-O), and (284.3 eV; C=C, sp2/C−C, sp3) (Fig. 3a). The deconvoluted O 1s spectra (Fig. 3b) indicate the existence of C-O at 530.7 eV, and −C=O at 532.7 eV. The survey spectra validate the predominant percentages of carbon and oxygen elements in FNAC.

Influence of pH on the removal of BB3

-

Variations in pH exert a considerable influence on the procedure of adsorption, as they customize the adsorbent's surface charge via the deprotonation/protonation of the distinct functional groups present on its surface. This alteration subsequently influences the interactions between the adsorbate molecules and the surrounding solution[38]. The adsorption investigation was performed in the pH span of 2.0 to 9.0, as illustrated in Fig. 4. BB3 adsorption by FNAC was extremely pH sensitive; when the pH level rose from 2.0 to 6.5, the elimination efficacy increases swiftly from 48.3% to 98.1%. With further changes in pH values from 6.5 to 9.0, the percentage removal of BB3 decreased to 83.2%. Therefore, the subsequent experiments have been performed at pH 6.5. There are multiple factors contributing to the outcome of the solution's pH on the adsorption of BB3 on FNAC. Controlling electrostatic interactions between the FNAC and BB3 is a crucial factor to consider. The reduced removal percentage at lower pH reflects the protonation of BB3 in acidic conditions. As the pH increases, the dye becomes increasingly deprotonated. Furthermore, at lower pH levels, the reduced color removal may indicate the existence of a positive charge developing on the FNAC surface, which hinders the dye removal process. When the pH increases, the functional groups on the FNAC surface that contain oxygen get deprotonated, leading to a rise in the negative charge on the FNAC surface. Due to the enhanced electrostatic interaction between FNAC and BB3, the adsorption of BB3 was heightened[32,34].

Figure 4.

Influence of pH on % removal of BB3 at [BB3] = 100 mg/L, FNAC dose = 0.10 g/100 mL, temperature = 298 K, and contact time = 140 min.

Influence of FNAC dose on BB3 removal

-

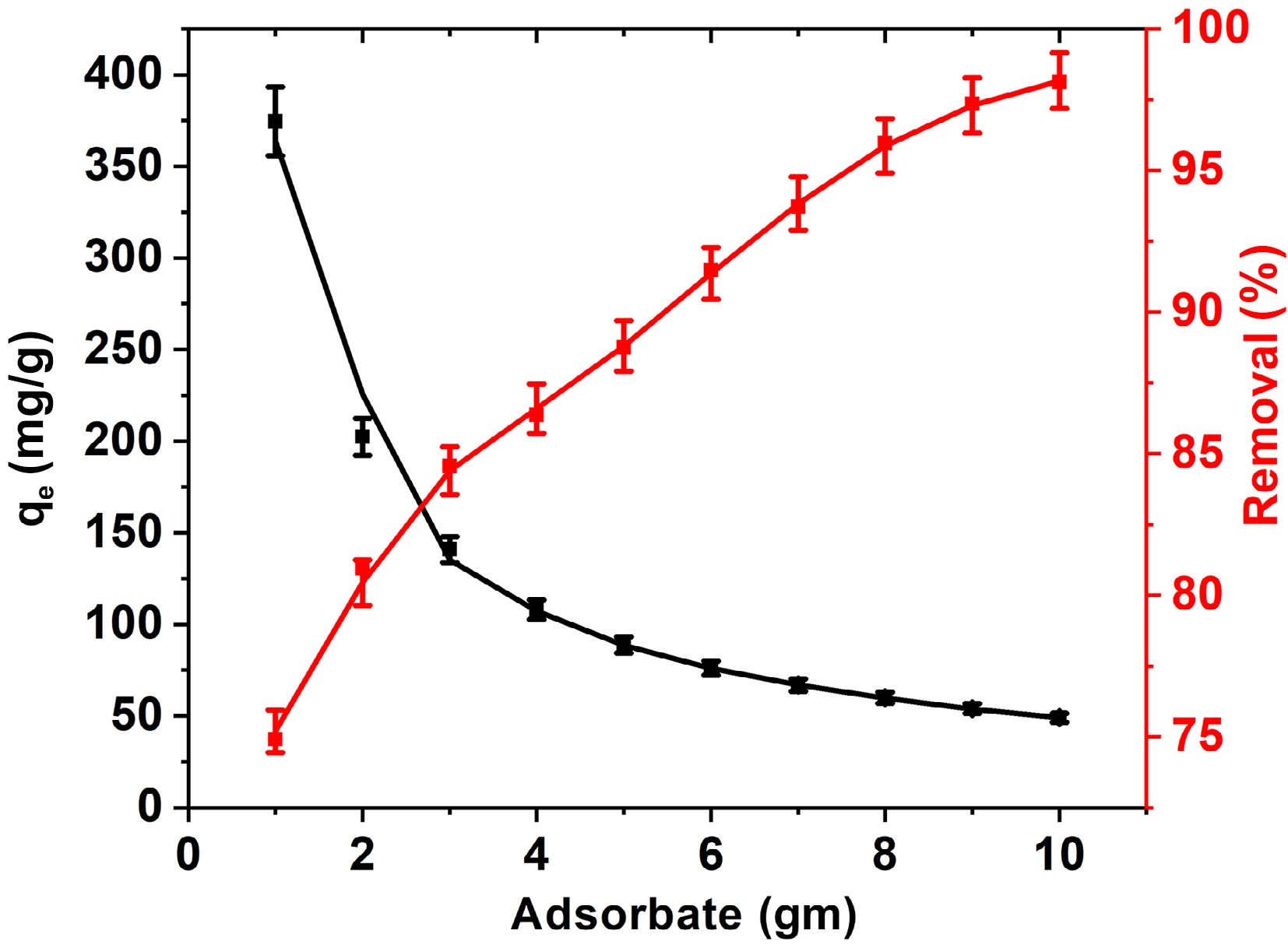

The amount of adsorbent utilized is the crucial factor influencing how well the adsorption process goes. Removal effectiveness usually increases with an increase in the adsorbent dosage. The FNAC dose was adjusted between 1.0 and 10.0 g/L in order to discover the optimal adsorbent value for BB3 removal. Figure 5 illustrates that the elimination of BB3 improves from 74.9% to 98.1%, in contrast, the adsorption effectiveness decreases from 374.6 to 49.1 mg/g as the FNAC dose is raised from 1.0 to 10.0 g/L. With an augmentation in adsorbent doses, the adsorbent's large surface area and more active adsorbing sites (more availability of functional groups) are responsible for the increase in adsorption effectiveness[43].

Figure 5.

Influence of FNAC dose on % removal and adsorption capacity of BB3 at [BB3] = 500 mg/L, pH = 6.5 ± 0.1, temperature = 298 K, and contact time = 140 min.

Impact of BB3 content, and contact duration on the removal of BB3

-

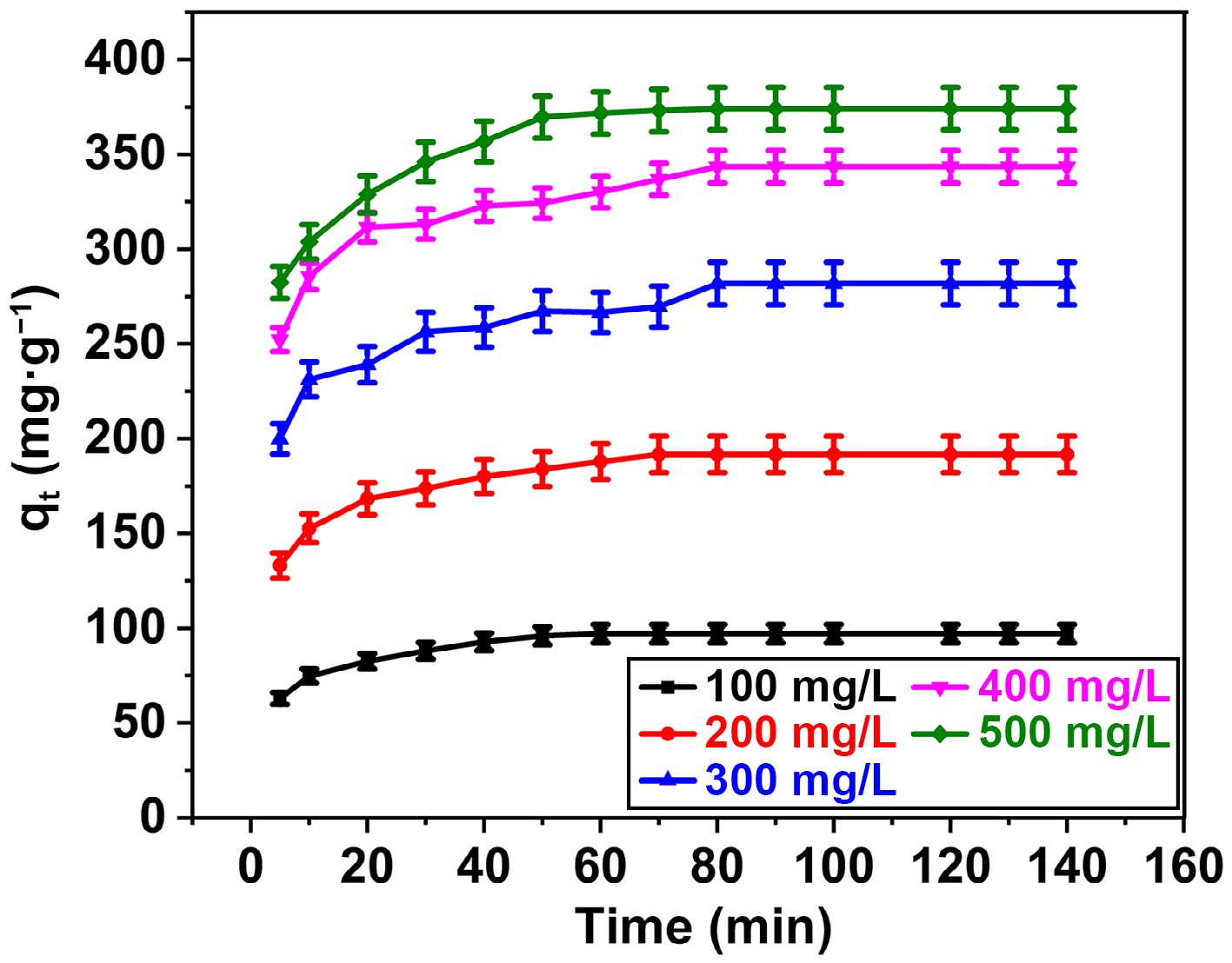

Adsorption, a time-dependent phenomenon, is critical in the design of innovative adsorption systems. The temporal interplay between dyes and adsorbents facilitates the elucidation of the kinetic propensity for binding and sequestration of dyes, alongside the identification of the optimal time range for achieving maximal removal efficiency. The observed trend in the adsorption capacity of BB3 on FNAC as an indicator of contact time at distinct BB3 concentrations (100–500 mg/L) is depicted in Fig. 6. It took 70 min for BB3 with concentrations of 100–200 mg/L to attain equilibrium. Nevertheless, when dealing with elevated concentrations of BB3 (300–500 mg/L), an extended equilibrium time of 90 min was observed. It has been observed that the adsorption rate exhibits a rapid increase during the initial time. Subsequently, the rate experiences a gradual increase until reaching 90 min, at which point it stabilizes, indicating the attainment of adsorption equilibrium. The initial swift adsorption can be assigned to the robust affinity between the BB3 and the FNAC active sites[31,32]. As the procedure advanced, the reduced adsorption rate is due to the gradual occupation of the FNAC active sites. The saturation of the FNAC's active sites is what causes the consistency in the adsorption rate.

Figure 6.

Influence of BB3 and contact time on % removal of BB3 at FNAC dose = 0.10 g/100 mL, pH = 6.5 ± 0.1, temperature = 298 K, and contact time = 140 min.

The starting dye concentration remains a critical parameter in establishing the adsorption rate for effective adsorption. The percentage removal of BB3 declines from 97.2% to 74.9%, while the adsorption capacity increases from 97.2 to 374.6 mg/g, as the BB3 concentration increases from 100 to 500 mg/L (Fig. 5). This is because the FNAC dosage was constant, which limited the total number of accessible active sites of FNCA and decreased the percentage of BB3 removal[32].

Adsorption isotherms

-

The choice of an appropriate isotherm model is essential for comprehension and enhancement of the mechanisms of adsorption. The adsorption outcomes of BB3 on FNAC at equilibrium were analyzed using various isotherm models, particularly the Freundlich and Langmuir. The multilayer adsorption phenomenon is elucidated by the Freundlich model, emphasizing the variety of affinities of adsorption visible on a heterogeneous surface. In contrast, the hypothesis put forth by Langmuir suggests that adsorption takes place within a single layer at a specific number of uniform sites, which are energetically identical, with barely any interactions among the adsorbed molecules.

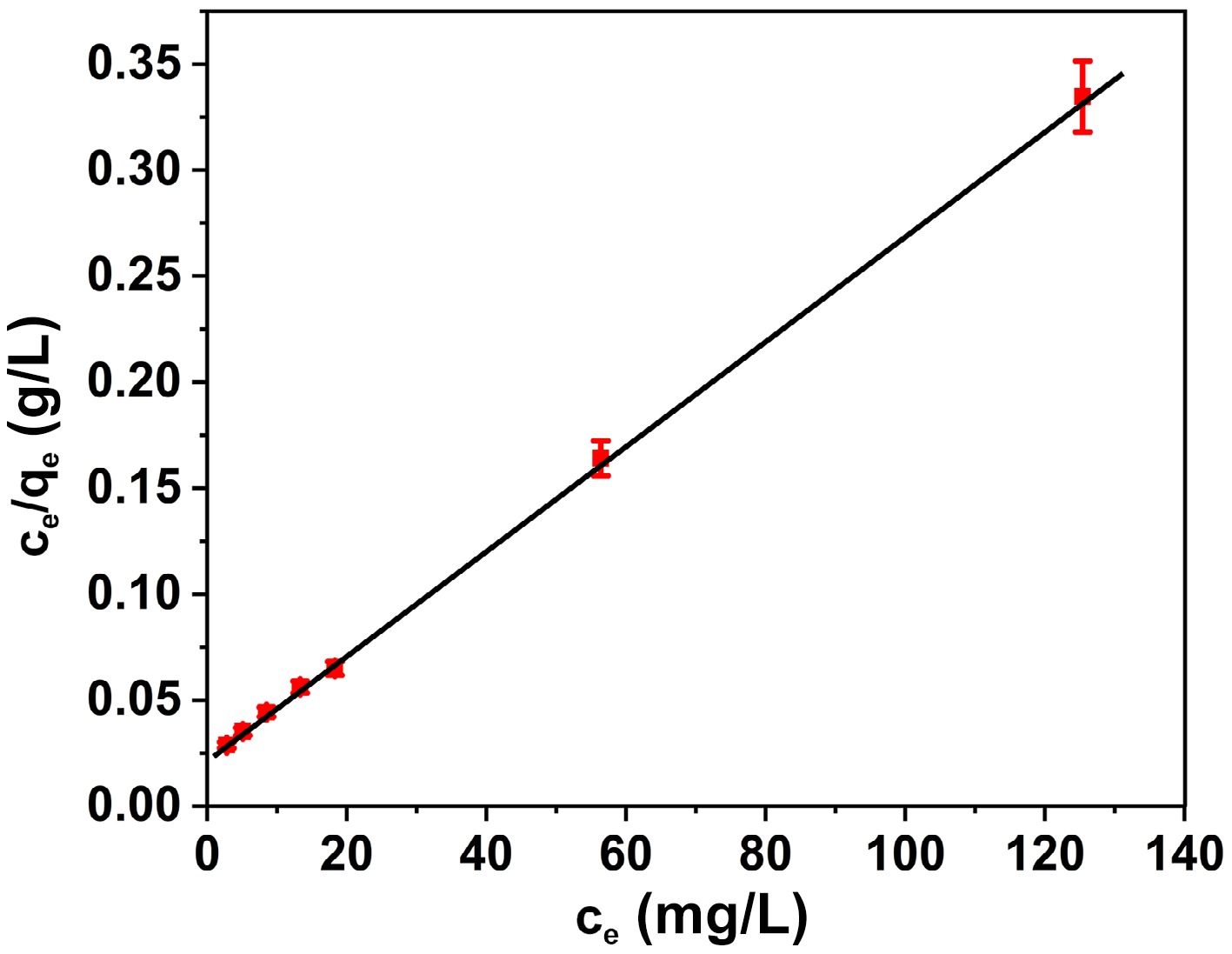

The correlation between a single layer of adsorbate adhering to the outside of an adsorbent with a restricted degree of active sites is described by Langmuir's adsorption formula, which will be expressed as follows[44]:

$ \dfrac{{\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{e}}}{{\mathrm{q}}_{\mathrm{e}}}=\dfrac{1}{{\mathrm{q}}_{\mathrm{m}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{x}}{\mathrm{K}}_{\mathrm{L}}}+\dfrac{{\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{e}}}{{\mathrm{q}}_{\mathrm{m}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{x}}} $ (4) In this context, Ce (mg/L) denotes the equilibrium levels of BB3, while qmax (mg/g) indicates the maximum adsorption capability of a monolayer. The Langmuir constant is represented by KL (l/mg), and the equilibrium quantity of BB3 adsorbed on FNAC is referred to as qe (mg/g). The Langmuir constant supplies a rationale for the free energy related to the adsorption process. Figure 7 illustrates a graph that delineates the connection between Ce and Ce/qe, showcasing a linear relationship. An analysis of the plot's intercept and slope can be used to calculate the values of KL and qmax (Table 1). The linear trend apparent in Fig. 7 provides compelling proof for the credibility of the Langmuir model. The findings of the investigation illustrated the unified characteristics of the FNAC surface and were compatible with the Langmuir model. The results also clarified the adhesion of a unique layer of BB3 molecules to FNAC's external surface. A similar finding has been documented regarding the BB3 dye adsorption onto activated carbon produced using various agricultural wastes[27−34]. The outcomes of the present investigation's calculation of the adsorption performance or capacity are superior to those of the previously published work[27−34]. Table 2 provides a comparison of the current work's adsorption capacity values with those found in the literature.

Table 1. Langmuir and Freundlich isotherm constants for the BB3 adsorption onto FNAC.

Isotherm Isotherm constant Constant values Langmuir qmax (mg/g) 389.1 R2 0.9986 RL 0.0169 Freundlich KF (mg/g) 84.63 1/n 0.3453 R2 0.8981 Table 2. Evaluative analyses of the adsorption capacity of BB3 across various adsorbent substrates.

Adsorbent Surface area (m2/g) qmax (mg/g)/

% removalRef. Heveabra siliensis seed coat 1,225 227.27 [27] Silybum marianum stem 122.56 36.8 [28] Waste ash 935 2.73 [29] Persea americana nuts 1,593 625 [30] Cedar sawdust 1.33 85.3 [31] Carbon-silica composite 297 1,295.9 [32] Sugar cane bagasse − 72.32% [33] Macadamia seed husks 99.0% [34] Fox nut shell 1,813.2 374.6 Current study The dimensionless equilibrium variable, RL, used to assess the preference of adsorption is defined by Eq. (5):

$ {\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{L}}=\dfrac{1}{1\mathrm{ }+{\mathrm{K}}_{\mathrm{L}}{\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{o}}} $ (5) Based on the RL value, isotherm classes are categorized as favorable (0 < RL< 1), unfavorable (RL = 0), irreversible (RL > 1), or linear (RL = 1)[45].

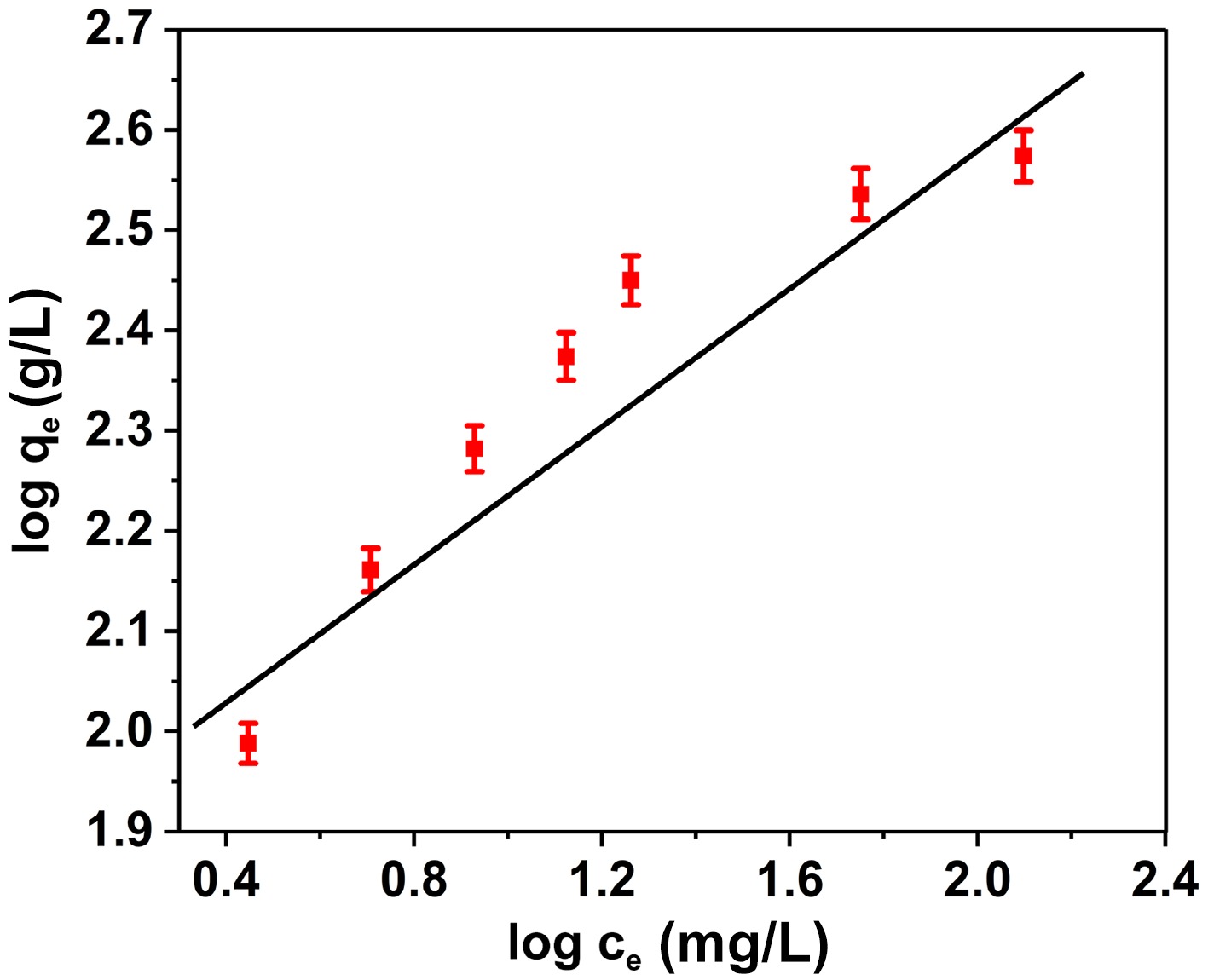

The Freundlich approach elucidates multi-layer adsorption rather than merely depicting a plateau-type saturation, rendering it more suitable for heterogeneous surfaces[46]. The statement can be expressed in terms of mathematics as follows:

$ \mathrm{l}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{g}{\mathrm{q}}_{\mathrm{e}}=\mathrm{ }\mathrm{l}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{g}{\mathrm{K}}_{\mathrm{F}}+\dfrac{1}{\mathrm{n}}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{g}{\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{e}} $ (6) In this context, the equilibrium quantity of BB3 is denoted as Ce (mg/L), while the amount of BB3 adsorbed on FNAC at equilibrium is represented by qe (mg/g). Furthermore, particular constants connected to the Freundlich model are indicated by KF and n. Figure 8 illustrates the straight-line correlation between lnCe and lnqe. The intercept (ln KF) and slope (1/n) of the plot were employed to derive the values of KF and n, as illustrated in Table 1. The value of n represents the adsorption selectivity. The adsorption of BB3 on FNAC conforms to a typical Langmuir isotherm, as indicated by the value of 1/n being less than 1[47].

A significant R2 value of 0.9986 established that the BB3 adsorption on FNAC was closely correlated with the Langmuir isotherm hypothesis. This notable relationship suggests an identical distribution of active adsorption sites across the FNAC surface. Moreover, the observed RL values for the Langmuir isotherm remained within the span of 0 to 1, while the Freundlich constant 1/n exhibited a value less than 1, thereby suggesting a process that is thermodynamically favourable[48]. Table 2 presents a comparative analysis of the adsorption capacity for BB3 in relation to various activated carbons derived from solid waste materials. The significant adsorption capacity exhibited by this paper elucidates the prospective utilization of FNAC as an attractive adsorbent for efficient BB3 elimination.

Adsorption kinetics

-

The adsorption kinetics were investigated by evaluations that took temporal variables into consideration. The investigation's temporal results were analyzed using the Lagergren's first-order model (Eq. [7]), Ho-McKay's second-order kinetic model (Eq. [8]), and the Intraparticle Diffusion (IPD) model (Eq. [9])[48−50]. Here, k1 (min−1), k2 (g−1 mg−1 min−1), and kp (mg−1 g−1 min−0.5] stands for the pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, and intraparticle diffusion rate constant, accordingly.

$ \mathrm{l}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{g}\left({\mathrm{q}}_{\mathrm{e}}-{\mathrm{q}}_{\mathrm{t}}\right)=\mathrm{ }\mathrm{l}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{g}{\mathrm{q}}_{\mathrm{e}}-\dfrac{{\mathrm{k}}_{1}}{2.303}\mathrm{t} $ (7) $ \dfrac{\mathrm{t}}{{\mathrm{q}}_{\mathrm{t}}}=\dfrac{1}{{\mathrm{k}}_{2}{\mathrm{q}}_{\mathrm{e}}^{2}}+\dfrac{\mathrm{t}}{{\mathrm{q}}_{\mathrm{e}}} $ (8) $ {\mathrm{q}}_{\mathrm{t}}={\mathrm{k}}_{\mathrm{p}}{\mathrm{t}}^{1/2}+\mathrm{ }\mathrm{C} $ (9) In this context, qt (mg/g) and qe (mg/g) denote the quantity of BB3 that was successfully adsorbed onto FNAC at a designated time t and at equilibrium, respectively. Furthermore, C denotes the intercept value, and kp specifies the constant related to intraparticle diffusion.

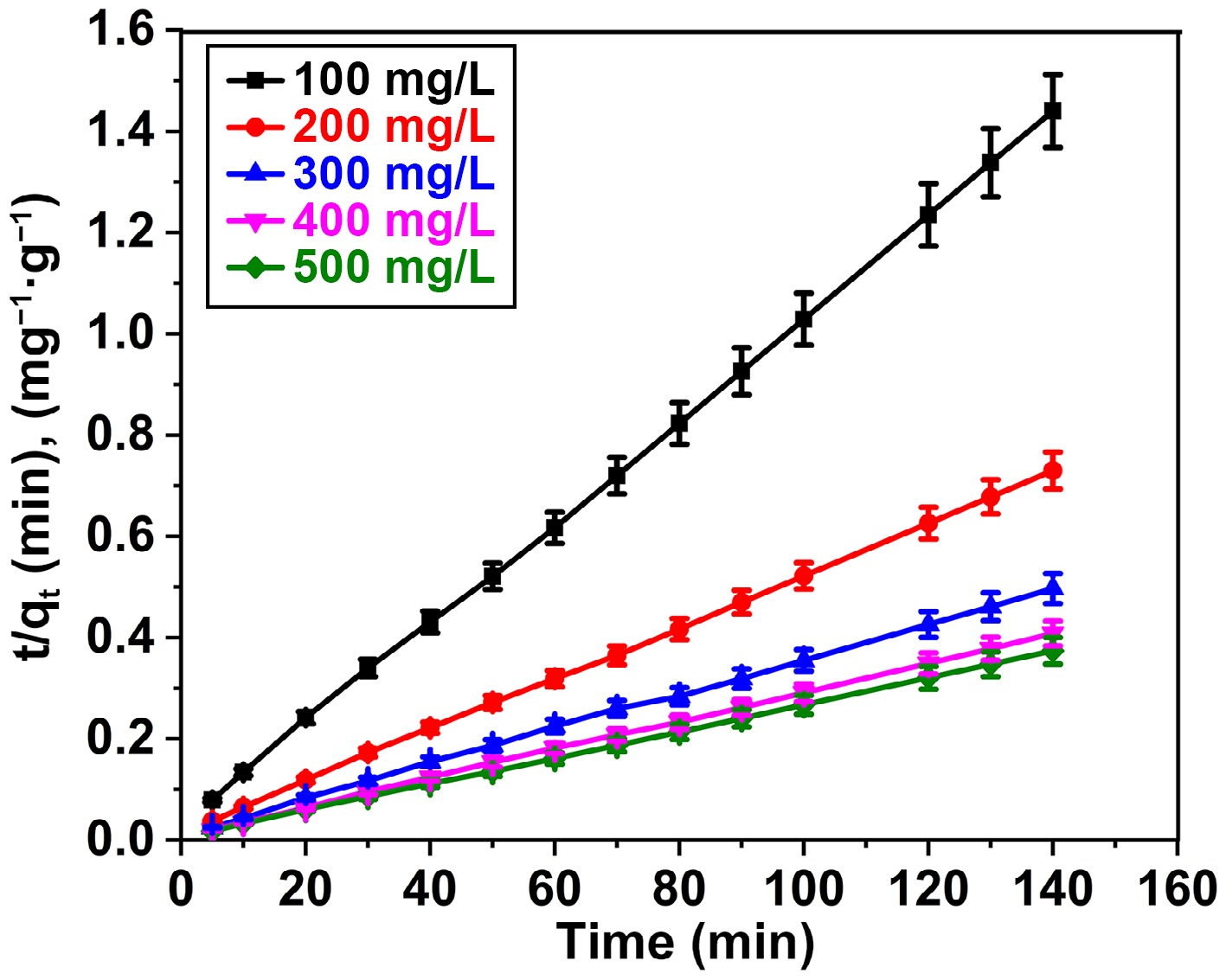

The exclusion of BB3 reveals a noteworthy correlation with the pseudo-second-order strategy, as evidenced by R2 values close to 1. The regression coefficient analysis indicates R2 values of 0.9994, 0.9982, 0.9953, 0.9992, and 0.9968 for BB3 concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 mg/L, respectively, within the framework of PSO kinetics investigation (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Pseudo-second order plot for adsorption of BB3 on FNAC at FNAC dose = 0.10 g/100 mL, pH = 6.5 ± 0.1, temperature = 298 K, and contact time = 140 min.

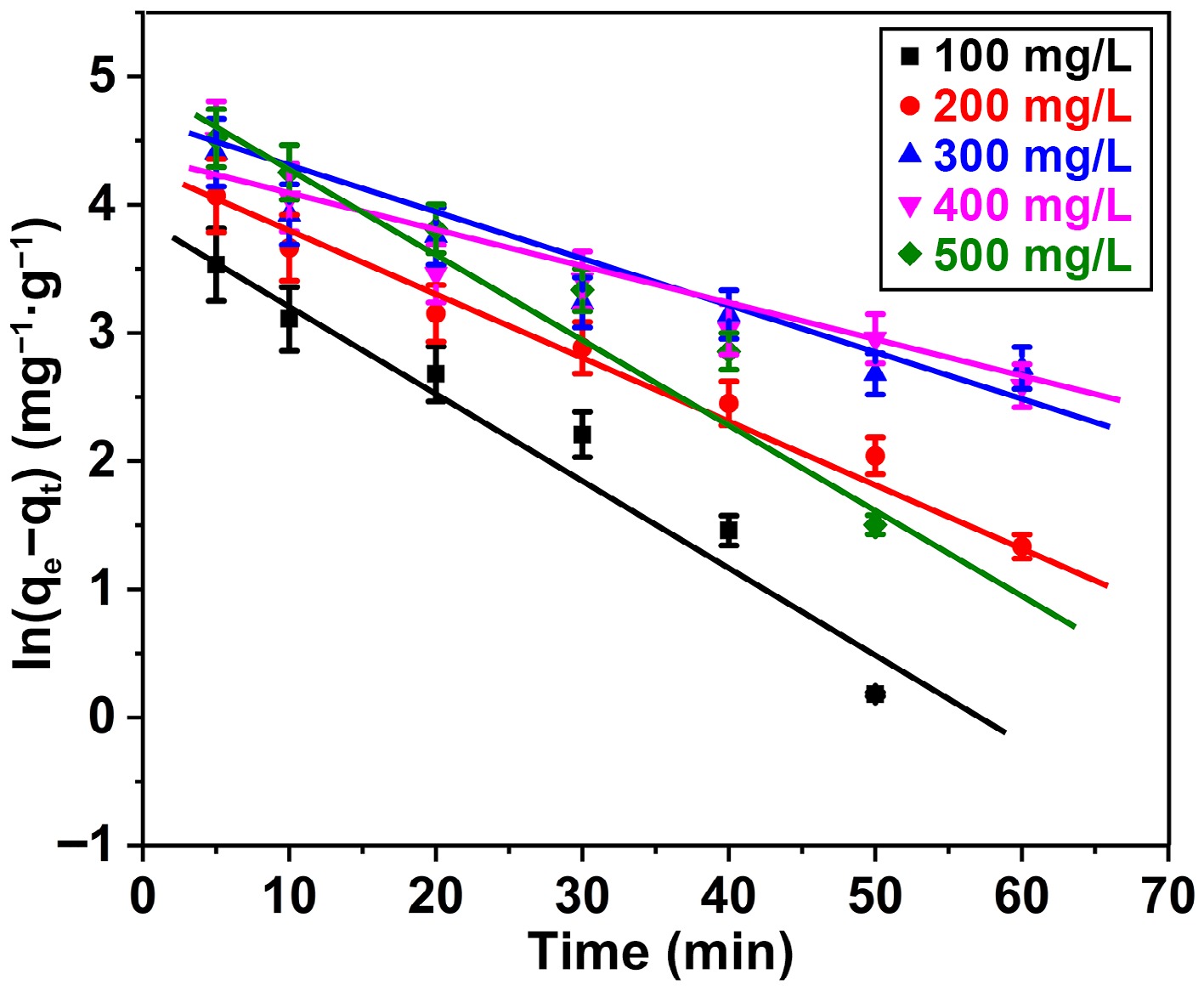

Conversely, upon the application of the PFO approach, the R2 value was ascertained to be 0.9575, 0.9861, 0.9357, 0.9447, and 0.9613 for BB3 concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 mg/L, respectively (Fig. 10). The conclusions of the investigation (374.6 mg/g) closely match the capacity of adsorption calculated using the PSO model (384.6 mg/g), especially when compared to the PFO approach (155.9 mg/g). The results demonstrate that the BB3 adsorption kinetics on FNAC comply ith the fundamentals of second-order. A thorough description of the variables determined for the PFO and PSO models is presented in Table 3.

Figure 10.

Pseudo-first order plot for adsorption of BB3 ions on FNAC at FNAC dose = 0.10 g/100 mL, pH = 6.5 ± 0.1, temperature = 298 K, and contact time = 140 min.

Table 3. Variables computed from the PFO and PSO kinetic model.

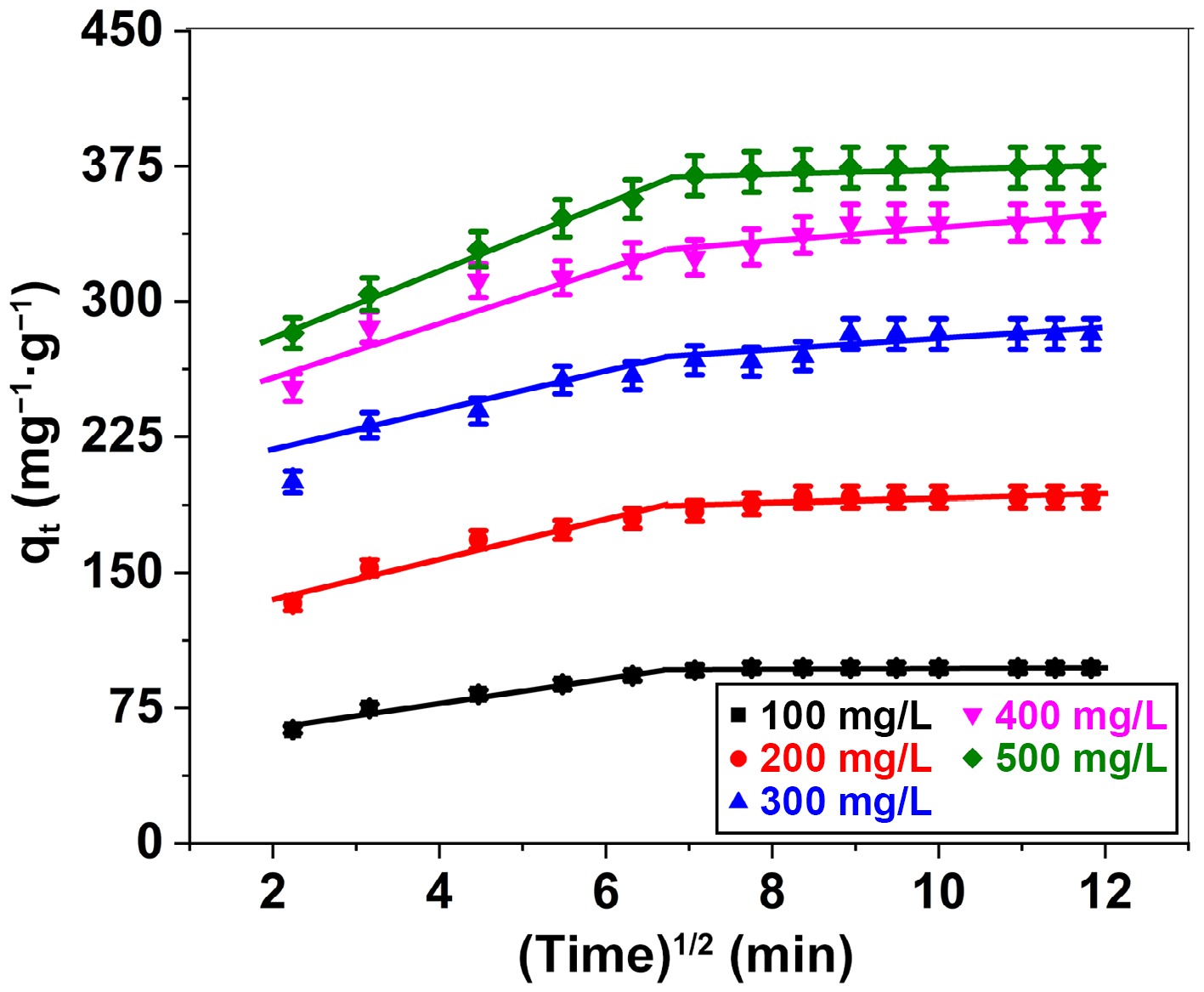

Kinetic models Parameters Initial dye concentration (mg/L) 100 200 300 400 500 Pseudo-first order kinetic qe (mg/g) 52.71 66.91 72.85 85.72 155.94 k1 (min−1) 0.0685 0.0457 0.0278 0.0340 0.0660 R2 0.9575 0.9861 0.9357 0.9447 0.9613 Pseudo-second order kinetic qe (mg/g) 100.5 196.08 285.71 357.14 384.61 k2 [/g(mg·min)] 0.00337 0.00171 0.0010 0.0009 0.00112 R2 0.9994 0.9982 0.9953 0.9992 0.9968 qe (mg/g) [experimental] 97.2 191.5 281.7 343.6 374.6 The process of BB3 adsorption onto FNAC was elucidated through the utilization of the IPD hypothesis, derived from the graphical representation of qt against t1/2. As demonstrated in (Fig. 11), the adsorption procedure unfolds through two distinct linear paths. The initial linear segment illustrates the predominance of mass transfer, wherein BB3 molecules transpire from the bulk solution onto the surface of the adsorbent. The second linear section reflects diffusion control, indicating the movement of BB3 molecules from the surface into the inner pores of the adsorbent. Nonetheless, it seems that IPD may not constitute the principal factor influencing the adhesion of BB3 onto the FNAC surface, given that the linear illustrations do not converge at the origin.

Figure 11.

Intraparticle diffusion plot for adsorption of BB3 ions on FNAC at FNAC dose = 0.10 g/100 mL, pH = 6.5 ± 0.1, temperature = 298 K, and contact time = 140 min.

Thermodynamic studies

-

Thermodynamic parameters are essential for establishing the characteristics and feasibility of the adsorption process. The proportion of BB3 elimination and the adsorption capacity onto FNAC demonstrate a significant decline with increasing temperature. The evaluation of thermodynamic parameters pertaining to the adsorption of BB3 on FNAC was conducted using Eqs (10)–(12), under a temperature band of 298 to 308 K.

The correlation between the entropy (ΔS°), and enthalpy (ΔH°) of adsorption with respect to ΔG° is demonstrated in Eq. (10). On the other hand, the KD interpretation is displayed in Eq. (11). Equation (12) provides the equilibrium constant (KD), and Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°) at a specific temperature (T).

$ \mathrm{l}\mathrm{n}{\mathrm{K}}_{\mathrm{D}}=-\left(\dfrac{{\Delta \mathrm{G}}^{\mathrm{o}}}{\mathrm{R}\mathrm{T}}\right)\mathrm{ }=-\left(\dfrac{{\Delta \mathrm{H}}^{\mathrm{o}}}{\mathrm{R}\mathrm{T}}\right)\mathrm{ }+\mathrm{ }\left(\dfrac{{\Delta \mathrm{S}}^{\mathrm{o}}}{\mathrm{R}}\right)$ (10) $ {\mathrm{K}}_{\mathrm{D}}=\dfrac{{\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{A}\mathrm{e}}}{{\mathrm{C}}_{\mathrm{e}}} $ (11) $ \Delta \mathrm{G}{\text°}=-\mathrm{R}\mathrm{T}\mathrm{ }\,\mathrm{l}\mathrm{n}\,{\mathrm{K}}_{\mathrm{D}} $ (12) The equilibrium amount of BB3 is designated as Ce, whereas the equilibrium quantity of BB3 adsorbed onto FNAC is designated as CAe. The values for ΔS° and ΔH° were obtained from the slope and intercept of the lnKD against 1/T plot. The results of the calculation of the various parameters have been consolidated in Table 4. BB3 adsorbs onto the surface of FNAC exothermically, as indicated by the negative ΔH° value. Moreover, the negative ΔG° reinforces the concept that the adsorption of BB3 onto FNAC takes place spontaneously. The decreasing ΔG° figures show that the adsorption is becoming less efficient with the rise in temperature. In the process of adsorption, the interface of the solid-solution exhibits a discernible reduction in randomness, as evidenced by the negative ΔS° value[51].

Table 4. Thermodynamic parameters concerning the adsorptive elimination of BB3 by FNAC.

Temp (K) ∆S° [J(K·mol)] ∆H° (kJ/mol) ∆G° (kJ/mol) 298 −123.72 ± 5.19 −43.62 ± 2.07 −6.751 ± 0.39 303 −6.133 ± 0.42 308 −5.514 ± 0.33 Mechanism of adsorption

-

The elimination of BB3 dye from the aquatic solution utilizing FNAC depends extensively on the different functional groups (aromatic, carbonyl, phenol, hydroxyl, etc) present on the surface of FNAC. This was validated by the FTIR spectral analysis shown in Fig. 2. FNAC functional group's surface can be neutral or charged (positive and negative) depending on deprotonation and protonation. Functional groups, viz –OH, O-, C=O, C=C, and –COOH, present on the surface of FNAC will be responsible for the adsorption of BB3 dye via different types of interaction, including π–π interactions, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic attractions. Figure 12 summarizes the potential adsorption pathway of BB3 dye on the FNAC surface. A similar discovery was made about the BB3 adsorption on activated carbon developed from sugar cane bagasse, Persea americana nuts, and Silybum marianum stem that had been chemically modified[29−31].

Rejuvenation and reusability

-

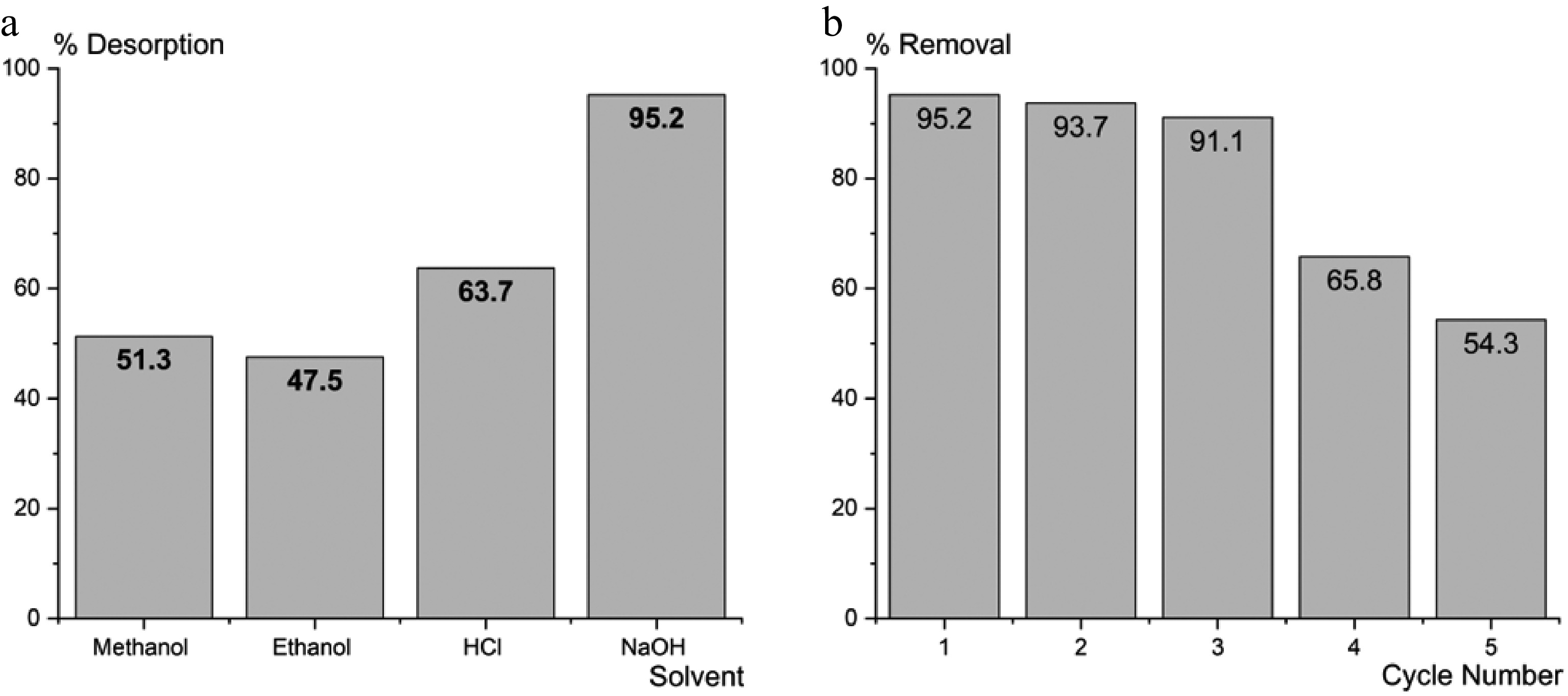

The durability and adaptability of adsorbents are essential for applications in industries. The desorption of BB3 from the surface of FNAC was checked with different solvents, including ethanol (90%), methanol (90%), HCl (0.5 M), and NaOH (0.5 M). Results showed that NaOH is the best solvent for removing BB3 from FNAC (Fig. 13a).

Adsorption-desorption investigations were carried out over five successive cycles to evaluate the regeneration capability of FNAC. The eluent employed was a 0.5 M NaOH solution. Following the achievement of optimal BB3 adsorption, 0.10 g of FNAC was introduced into 50 mL of NaOH and agitated until BB3 became undetectable. The revitalized FNAC was subsequently employed in additional cycles. Figure 13b demonstrates a decrease in the percentage elimination of BB3, which fell from 95.2% to 91% following three successive cycles. Whereas, after the third cycle, the efficiency of FNAC was drastically reduced. This demonstrates that FNAC can be effectively re-used up to three times, with minimal performance decline.

-

The elimination of BB3 dye has been documented through the utilization of various activated carbons derived from solid waste substances; nonetheless, these substances exhibit markedly low adsorption abilities. The manufactured FNAC demonstrates an adsorption capability of 374.6 mg/g at 25 °C, attributed to its porous structure, which features a surface area of 1,813.2 m2/g. The current study demonstrates that FNAC works as a strong adsorbent for facilitating the removal of BB3 from aqueous solutions. The factors that especially influenced the adsorption process include pH, the initial content of BB3, the quantity of FNAC utilized, and the time of contact between the BB3 and FNAC. It has been determined that BB3 adsorption functions optimally at a pH of 6.5. Electrostatic adsorption induced by protonation is the primary mechanism by which FNAC removes BB3. The analysis of isotherms revealed that the Langmuir simulation offered the most accurate depiction of the equilibrium outcomes for BB3 removal. The evidence suggests that the adsorption procedure of BB3 may be effectively characterized by a pseudo-second-order kinetic approach. Negative ΔH° and ΔG° demonstrate that BB3 spontaneously adsorbs onto FNAC and that this adsorption diminishes with temperature. Overall, the produced FNAC demonstrates significant efficacy in the elimination of various dyes and heavy metal contaminants from wastewater, attributable to its expansive surface area and the abundance of functional groups present on its surface.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: statistical analysis: Srivastava A; investigation: Srivastava A, Goswami MK, Pandey PK; methodology, experimental and graphical work: Goswami MK; formal analysis: Pandey PK, Srivastava N; supervision: Srivastava N; writing − original draft: Srivastava A, Pandey PK, Srivastava N. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The supporting datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors express profound gratitude to GLA University for providing laboratory facilities and necessary chemicals for the experimental study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Srivastava A, Goswami MK, Pandey PK, Srivastava N. 2025. Kinetic, adsorption, and thermodynamic evaluation of basic blue 3 removal by activated carbon derived from fox nutshell. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 50: e025 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0025

Kinetic, adsorption, and thermodynamic evaluation of basic blue 3 removal by activated carbon derived from fox nutshell

- Received: 04 May 2025

- Revised: 08 September 2025

- Accepted: 24 September 2025

- Published online: 16 December 2025

Abstract: Over the past few years, environmental concerns regarding dye contamination have grown. Removing dye from industrial wastewater is crucial for environmental sustainability. The removal of basic blue 3 (BB3) dye has been documented through the utilization of various activated carbons derived from solid waste items; nevertheless, these substances exhibit significantly low adsorption capacities. Fox nutshell, an agricultural by-product, is widely available in India. Its fibrous texture and high cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin content make it ideal for dye adsorption. By sodium hydroxide activation followed by carbonization at 500 °C, the fox nutshell was converted into low-cost fox nutshell activated carbon (FNAC). The elimination of the BB3 dye was accomplished via its adsorption onto FNAC. A porous framework with 1,813.2 m2/g surface area, and 2.16 nm average pore diameter was discovered in the FNAC using SEM and BET investigations. FTIR analysis shows the presence of the –COOH, C=C, C=O, and –OH functional groups on the surface of FNAC. The equilibrium time was found to be 90 min, and a pseudo-second-order kinetic approach is consistent with the adsorption trend. The Langmuir approach provided a precise illustration of the adsorption isotherms. The optimal pH for BB3 (500 mg/L) adsorption onto FNAC (0.10 g/100 mL) was 6.5, with an adsorption capability of 374.6 mg/g. The adsorption of BB3 onto FNAC occurs spontaneously, as evidenced by a negative ΔG°, while the noted decrease in adsorption with increasing temperature aligns with a negative ΔH°. The findings demonstrate that the FNAC operates as a particularly effective adsorbent, revealing significant potential for application in the remediation of wastewater tainted with BB3 dye.

-

Key words:

- Basic blue 3 /

- Fox nutshell /

- Activated carbon /

- Langmuir adsorption isotherm /

- Kinetic modeling /

- pH /

- Equilibrium time