-

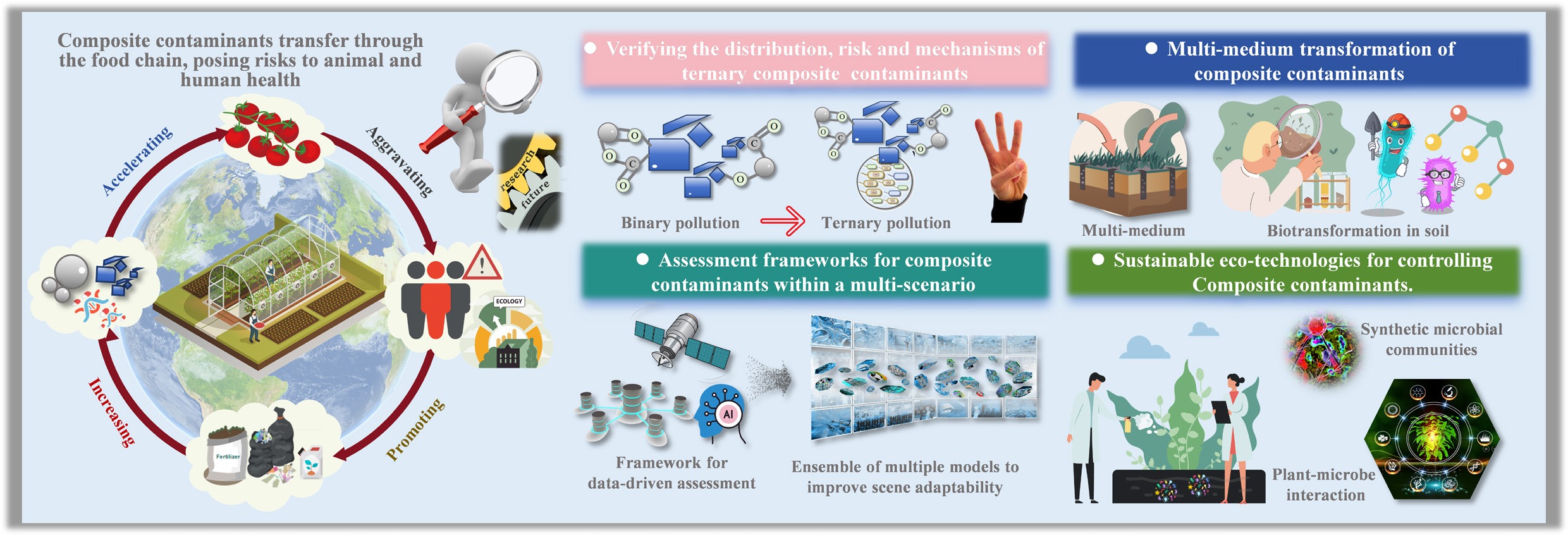

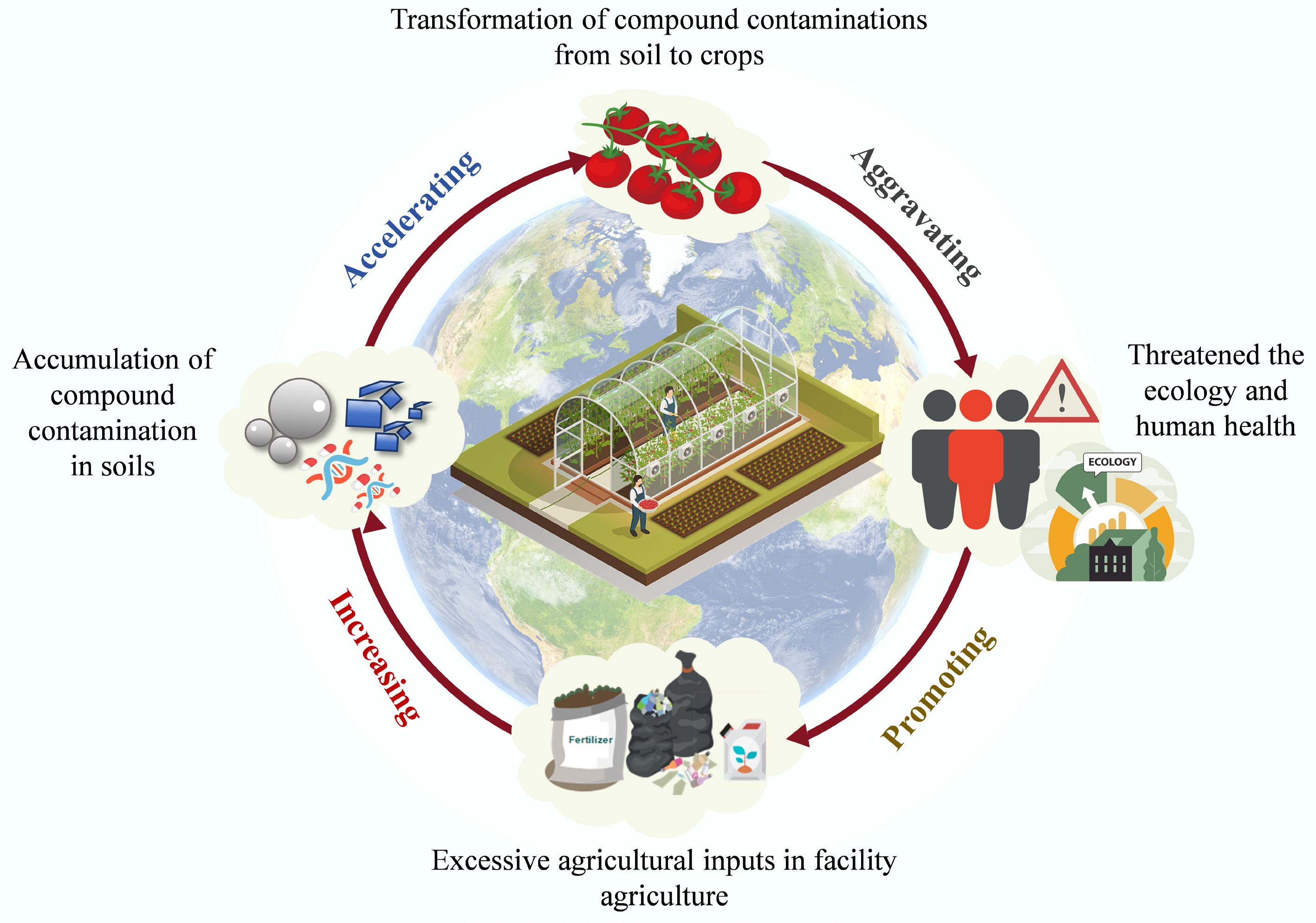

Facility agriculture is a modern agricultural method for the efficient production of plants and animals that employs engineering technologies under relatively controlled environmental conditions and plays a pivotal role in ensuring food supply and enhancing agricultural productivity[1,2]. However, compared to traditional agriculture, facility agriculture operates in a perennially enclosed environment with high planting frequency and intensive input of agricultural resources, leading to the accumulation of soil pollution. The excessive and improper use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and agricultural films has led to the accumulation of pollution, particularly HMs, MNPs, and ARGs. These contaminants, characterized by their high toxicity, persistence in the environment, and potential for bioaccumulation and transfer through the food chain, pose severe risks to both ecosystems and human health. Thus, investigating the pollution patterns of these substances in facility agricultural systems and formulating targeted mitigation strategies are essential to ensure the sustainable development of facility agriculture.

A substantial body of literature has previously documented elevated levels of HMs, MNPs, and ARGs in facility agricultural soils[3−5], surpassing those observed in conventional agricultural systems[6]. For instance, the frequent use of plastic films in facility agriculture could result in MNP levels in soil that are 49.20%–81.27% higher than with plastic film mulching[7]. Moreover, the residual concentrations of HMs following intensive fertilizer and pesticide applications increased by 11.00% to 38.00%[8]. Moreover, the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and ARGs in facility agricultural soils was notably elevated, with abundance increasing by 14.05–364.10-fold compared to traditional farmlands[9]. It is important to note that these contaminants do not operate independently; rather, their synergistic effects significantly exacerbate soil ecological toxicity. These composite contamination scenarios not only jeopardize soil health and crop safety but also introduce significant risks to human health through the food chain. So, exploring the mechanisms of pollutant interactions and developing targeted technologies to address this issue is of paramount importance. However, most existing studies focus on a single pollutant, and the understanding of the migration and transformation laws of composite pollution and their superposition effects remains insufficient.

As previously demonstrated, the coexistence of HMs and ARGs can disrupt soil microbial communities and promote the horizontal transfer of ARGs among microorganisms, thereby leading to a significant rise in antibiotic-resistant bacterial populations[10]. Additionally, MNPs can adsorb heavy metal ions, forming composite pollutants that inhibit crop growth and destabilize ecosystems. Also, MNPs can serve as carriers for ARGs, further exacerbating their environmental dissemination[11,12]. Co-interactions among MNPs, heavy metals, and ARGs can lead to unpredictable pollution dynamics, posing significant challenges for risk assessment. Despite these concerns, comprehensive studies on the characteristics, risk assessment methodologies, and green control strategies for composite pollution in facility agriculture systems are still lacking. Addressing these issues requires a deeper understanding of the environmental behavior of composite contaminations under diverse conditions and the development of sustainable, targeted mitigation approaches.

In this regard, this review consolidates the characteristics of composite pollution, primarily involving HMs, MNPs, and ARGs, and provides an in-depth exploration of their sources, co-occurrence, migration, and ecological effects in facility agriculture environments. It also organizes the existing risk assessment methodologies for composite pollution and summarizes the application progress of key control technologies, including the advantages and limitations of physical, chemical, and biological remediation approaches. Furthermore, this paper discusses future research directions for composite pollutants in facility agriculture, focusing on mechanisms of pollutant interactions, the development of novel green remediation technologies, and precision control strategies. Most notably, the discussion extends beyond single- and binary-pollution to explore the mechanisms and challenges associated with ternary composite pollution in facility agriculture. This review offers a new perspective for in-depth understanding and governance of composite pollution to ensure sustainable agricultural practices in the face of increasing environmental pressures.

-

In facility agriculture, HMs, MNPs, and ARGs exhibit distinct spatial distribution patterns globally and regionally. Globally, Europe (particularly Denmark, Germany, and France) and Asia (especially China and South Korea) are identified as major hotspots for these contaminants[13,14]. Within China, these pollutants are predominantly concentrated in the North China, Northwest, and Eastern regions[9,15]. Specifically, the abundance of MNPs in facility soils averages 2,795.7 n/kg[16]. At the same time, heavy metal residues are primarily composed of As, Cu, and Cr, with concentrations reaching 13.6, 35.2, and 102.6 mg/kg, respectively[17,18]. Meanwhile, the abundance of ARGs ranges from 4.0 × 105 to 1.6 × 106 copies/g[19]. The implementation of agricultural practices such as plastic film cultivation, surface watering, and fertilization in greenhouse systems significantly alters the transport and transformation pathways of contaminants within the soil matrix. These practices not only facilitate the formation of composite pollution by promoting interactions between HMs, MNPs, and ARGs but also exacerbate the overall contamination levels, intensifying their ecological and health-related risks[20,21]. The specific pollution characteristics and impacts of composite contaminations are as follows.

Composite contaminations of heavy metals and micro/nanoplastics

-

The coexistence of HMs and MNPs is a prevalent phenomenon in soils used for facility agriculture. The use of plastic mulch in agricultural production plays a crucial role in effectively increasing soil temperature and retaining moisture, thereby enhancing crop yields[22]. However, the widespread use of plastic mulch has led to significant environmental issues, particularly micro- and nanoplastics pollution. It is estimated that the annual microplastic pollution caused by residual agricultural plastic film in China amounts to hundreds of thousands of tons. Due to their high specific surface area and strong adsorption capacity, MNPs can adsorb HMs in soil, forming "plastic-heavy metal" complexes. These composite contaminations lead to HM concentrations on MNPs reaching up to 126.77 mg/kg, with enrichment levels increasing over time[23]. For example, the work of Khoshmanesh et al. showed that the adsorption capacity of MNPs for cadmium, zinc, and lead can reach up to 1.8 mg/g[24], 2.42 mg/g, and 7.47 mg/g, respectively[25]. These complexes exhibit enhanced migration in soil, potentially promoting the co-transport of both contaminants to deeper soil strata or groundwater[26].

Furthermore, MNPs can alter soil physical-chemical properties (such as pH and organic matter content), thereby influencing the speciation and bioavailability of HMs, increasing their toxicity to plants[27−29]. For instance, composite contamination with cadmium and MNPs resulted in a 38% reduction in wheat root biomass and a 5.0% decrease in aboveground biomass compared with cadmium contamination alone[29,30]. This was further corroborated by Liu et al., who demonstrated that composite contaminations of MNPs and cadmium led to reductions of over 12.3% in fresh weight and over 29.1% in dry weight of sorghum, indicating a significant synergistic inhibitory effect[31]. Similarly, Song et al. reported that the interaction of MNPs and cadmium negatively impacted plant growth and development, threatening crop yield and quality[32]. Overall, the co-occurrence of HMs and MNPs can significantly exacerbate the negative consequences on soil ecosystems, enhancing the mobility and bioavailability of pollutants, thereby facilitating their transfer into crops and posing a broader risk across the food chain[33,34].

Composite contaminations of heavy metals and antibiotic resistance genes

-

ARGs, as emerging bio-contamination, are detected in high diversity and abundance in facility farmland soils, often at levels measured in 2.74 × 107 to 1.07 × 108 copies per gram (copies/g)[35]. Recently, these resistance genes have also been frequently identified within the endophytic environments of crops[36]. Moreover, heavy metal residues, such as copper and zinc, commonly used as feed additives to promote animal growth, would contribute to the proliferation of ARGs. Overuse results in the accumulation of heavy metals in livestock manure, which is later applied to farmland as organic fertilizer[37]. This selective pressure from heavy metals drives the production and spread of ARGs among soil microbial communities. As previously discovered, Cu2+ can increase the expression of ARGs in Escherichia coli by up to 8-fold, while Zn2+ enhances the transfer rate of ARGs in Bacillus subtilis by 4.62-fold[38]. The co-presence of heavy metals and antibiotics in livestock manure also amplified the risk of resistance gene transmission. The work of Fu et al. showed that combined cadmium and sulfadiazine application accelerated the dissemination of ARGs, with their abundance rising by 7.29-fold[39]. These composite contaminants can not only directly impact the ecosystem but also bioaccumulate through the food chain, ultimately increasing the likelihood of antibiotic-resistant infections and posing a critical challenge to public health.

Composite contaminations of micro/nanoplastic and antibiotic resistance genes

-

MNPs co-contaminated with ARGs have become a recent hot topic. In environments where MNPs and ARGs coexist, ARG abundance has been observed to increase by two to three times compared to surrounding areas[40]. The concentration of MNPs and ARGs was particularly high in the surface soil of regions with long-term use of plastic mulch films[41], where their enrichment is more pronounced. Both the roots and aboveground parts of crops can adsorb MNPs and ARGs, allowing them to enter the human body through the food chain. Additionally, the migratory properties of MNPs enable them to transport ARGs from contaminated areas to uncontaminated regions through soil pore migration, surface runoff, and wind dispersal. MNPs in soil can migrate through cracks and pores, potentially reaching human habitats via water and wind, posing direct health risks[42]. MNPs at a concentration of 80 particles/g-TS can increase the abundance of ARGs by 27.9%[43,44]. These findings demonstrated that MNP migration in soil can expand the spread of ARGs and enhance horizontal transfer risks.

Overall, the combined contamination of HMs, MNPs, and ARGs in facility agriculture exerts detrimental effects on soil ecosystems and crop growth (Fig. 1 & Table 1). Furthermore, these contaminations can bioaccumulate through the food chain, posing potential risks to animal, plant, and human health. Despite these concerns, the complex interactions and cumulative risks associated with triple or multiple composite contaminants remain poorly understood.

Table 1. Concentration of composite contaminations in facility agriculture

Contamination type Medium Concentration Ref. HMs-MNPs Soil ■ MNPs adsorb Cd:

425.65 mg/kg[24,65,112] ■ MNPs adsorb Pb: 476.6 mg/kg ■ MNPs absorb Cu: 29 mg/g ■ MNPs absorb Zn: 61.01−126.77 mg/kg HMs-ARGs ■ ARGs increased by 2.74 × 107−

1.07 × 108 copies/g[35,114] ■ ARGs increased by 0.20–

0.25 copies/bacterial cellMNPs-ARGs ■ ARGs detected in NPs:

0.05 copies/16S rRNA gene[24,41] ■ ARGs residual level in soil: 3.87–32.59 ppm -

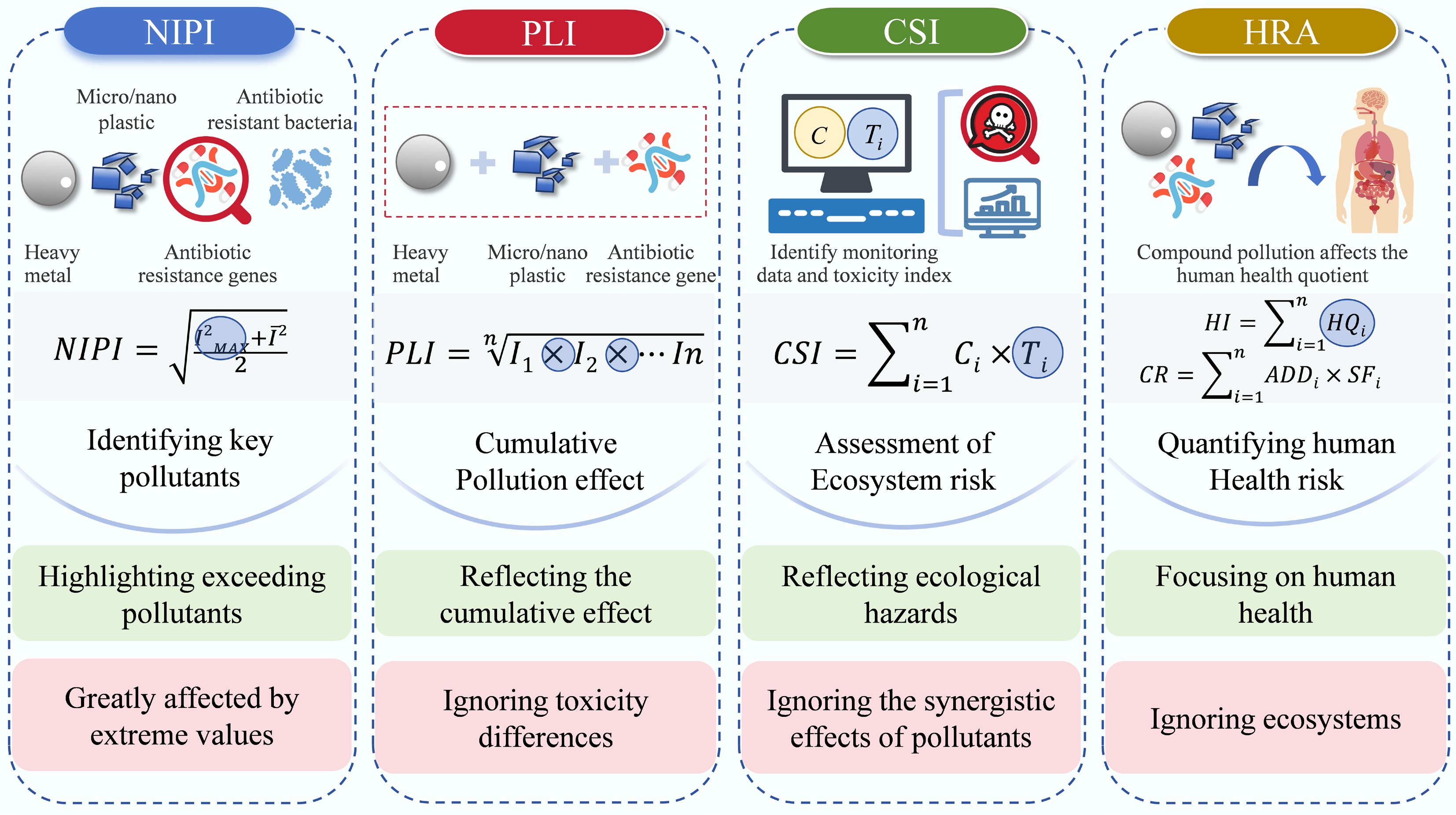

To quantitatively assess the environmental pollution risk posed by composite pollutants, a range of evaluation methods has been developed. The existing methods for assessing the risk of pollutants primarily include the nemerow pollution index (NIPI), contamination staging index (CSI), pollution load index (PLI), and health risk assessment models (HRA) (Fig. 2).

NIPI: emphasizing the impact of the most significant contaminant

-

The NIPI algorithm is a method for comprehensively assessing the overall pollution level of multiple contaminants by integrating information on various pollutants and emphasizing the impact of the most significant one[45]. For example, Zhao et al. applied NIPI to assess heavy metal contamination levels in composite-polluted soil from abandoned farmland[46]. The results indicated an overall moderate pollution level, with arsenic (As) identified as severely contaminated and cadmium (Cd) as moderately contaminated. Similarly, Wu et al. applied the NIPI algorithm to assess MPs pollution on beaches, showcasing its adaptability in monitoring emerging contaminants[47]. Prieskarinda et al. utilized the NIPI to evaluate the composite pollution of MPs and nitrogen-phosphorus in the Progo River in Indonesia, further highlighting its potential in addressing composite pollution scenarios[48]. The NIPI algorithm integrates information from multiple pollutants and emphasizes the impact of the most significant contaminants, offering computational simplicity and applicability[49]. However, it is important to note that NIPI relies solely on pollutant concentrations and fails to account for the varying toxic effects of pollutants on agricultural ecosystems or crop health, which may lead to discrepancies between assessment results and actual ecological impacts[39].

PLI: balancing the influence of multiple contaminations

-

The pollution load index (PLI) is a widely used algorithm for evaluating the overall pollution level in composite pollution scenarios, particularly in contexts such as facility farmlands and urban soils[50]. By employing the geometric mean method, the PLI effectively balances the influence of different pollutant concentrations, thereby reducing the overestimation of pollution levels caused by a single pollutant at high concentrations[51]. Utilizing the PLI, Wang et al. clearly illustrated the spatial heterogeneity of microplastic pollution in the soil environment, highlighting its practical utility[42]. Nevertheless, the PLI cannot independently evaluate the specific ecological effects or contamination levels of individual pollutants[52]. For example, while Iranian researchers applied the PLI to classify overall agricultural soil pollution as moderate, it could not identify the precise concentrations of specific metals, such as cadmium and lead[53]. Like the NIPI, the PLI does not fully capture the ecological risks of composite pollution scenarios because it does not incorporate ecological toxicity data for pollutants[54]. Moreover, the geometric mean approach used in the PLI may underestimate contamination levels when pollutant concentrations are low[52].

CSI: integrating toxicity and ecological sensitivity for risk assessment

-

Unlike the PLI and NIPI, the CSI algorithm incorporates pollutant toxicity and ecological sensitivity into its calculation to assess pollutant risks and identify ecological risks associated with pollutants. For instance, Peng et al. applied the CSI model to assess soil pollution risk in Changchun, China, identifying polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons as the pollutants with the highest ecological risk[55]. Additionally, the calculations of the Contaminant Sensitivity Index (CSI) take into account pollutant toxicity thresholds, such as the Effects Range Low (ERL) and Effects Range Medium (ERM), as well as ecological sensitivity factors. As a result, the CSI demonstrates a heightened sensitivity to highly toxic pollutants[56]. However, the CSI was initially designed for aquatic environments. The application of soil pollution assessment requires adjustments to pollution grading standards, which may introduce uncertainty into evaluation results[56,57]. Moreover, some CSI parameters, such as toxicity weights, are inherently subjective and may compromise the impartiality of the evaluation outcomes. Additionally, the CSI is predominantly based on static data for ecological risk assessment, limiting its ability to capture dynamic changes in pollutant levels and ecological vulnerability[58].

HRA: linking pollutant exposure to human health risks

-

HRA is an approach that directly evaluates pollution risks to human health[59]. It excels at providing a holistic view of the potential health threats posed by pollutants through multi-pathway exposure evaluations (such as inhalation, ingestion, and skin contact), and it distinguishes between carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risks. Also, HRA applies to a wide range of pollutants, including HMs, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and MPs[60−62]. A recent study from Africa applied HRA to evaluate whether composite pollutants (such as arsenic, chromium, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) in facility soils posed health risks to residents through multiple exposure pathways (e.g., ingestion, dermal contact, inhalation, and dietary intake through the food chain). The results identified traffic emissions as the primary source of carcinogenic risks associated with PAHs[63]. While HRA primarily focuses on health risks rather than directly assessing ecological pollution. Furthermore, this method relies heavily on parameters such as pollutant reference doses, which are difficult to determine, and requires extensive research on pollutant migration and transformation. Its lack of dynamic assessment capability poses a significant challenge to the accuracy of HRA results[64].

Evidently, existing risk assessment methods are unable to simultaneously evaluate the contamination levels and ecological risks associated with composite contamination. Due to the specificity of each method for particular contaminations or scenarios, different methods yield divergent results. In the future, it is essential to integrate parameters from multiple models and establish a complementary validation framework to comprehensively assess the health risks posed by composite contamination. Additionally, an evaluation system that combines numerical calculations with real-world scenarios should be developed. By incorporating actual contexts into the assessment process, over-reliance on numerical judgments can be avoided. Furthermore, linking pollution indices to real-world effects (such as crop growth responses and changes in soil function) will provide a more robust scientific foundation for the precise management and control of composite contaminations.

-

The coexistence of environmental pollutants is far from a simple superposition. Instead, it involves complex physical, chemical, and biological interactions that significantly influence each other's migration and transformation pathways and overall ecotoxicity. Understanding the co-occurrence of these pollutants provides a foundational framework for identifying their sources, pathways, and sinks. However, to fully characterize their environmental behavior and ecological risks, it is essential to delve into the mechanisms governing their migration and transformation. Elucidating these underlying synergistic effects is crucial for overcoming the limitations of existing risk assessment methodologies and developing effective mitigation strategies.

Surface interactions of micro/nanoplastics with heavy metals

-

In facility agricultural soil, MNPs and HMs interact through surface complexation, electrostatic interactions, and precipitation, forming complex interfacial reaction networks[65] (Fig. 3a). Surface oxidation of MNPs generates oxygen-containing functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl and carboxyl groups), which provide coordination sites for stable complexation with HM ions[66]. This complexation alters HMs speciation, affecting their mobility and bioavailability in soil[67]. Complexation can markedly improve the transport rate of heavy metal ions. As MNPs age, they exhibit greater surface area, a higher likelihood of generating negative surface charges, and increased hydrophilicity, factors that collectively enhance their ability to complex and adsorb heavy metals. Notably, the interfacial interactions between MNPs and HMs are influenced by soil physicochemical characteristics and microbial communities[68−70]. For example, soil nitrogen limitation can stimulate microorganisms to excrete extracellular polymeric substances, thereby strengthening complexation and increasing HMs carrying capacity[71]. Electrostatic interactions drive adsorption balance via charge matching, thereby regulating HM adsorption onto MNPs. The slight negative charge on the surface of MNPs enables them to attract and adsorb positively charged heavy metal ions via electrostatic interactions. This process fills adsorption sites, forming a composite system of the two contaminants[72]. Furthermore, MNPs can co-precipitate with the hydroxides of metals such as iron and manganese. Notably, heavy metal hydroxides with high specific surface areas and numerous adsorption sites, such as Ni(OH)2 and Co(OH)2, are capable of efficiently accumulating nearby heavy metal ions[73]. The presence of MNPs leads to the formation of composite systems with metal hydroxides, thereby significantly enhancing the adsorption efficiency for HMs[34]. This co-precipitation process further amplifies the combined impacts of the two contaminants.

Figure 3.

Mechanism of synergistic pollution for composite contaminations. (a) Surface interactions of micro/nanoplastics with heavy metals. (b) Co-selection of heavy metals and ARGs drives antibiotic resistance evolution. (c) MNPs enhance ARGs spread via vectoring, biofilm protection, and microbial shift.

Co-selection of heavy metals and ARGs drives antibiotic resistance evolution

-

HMs can promote the emergence and proliferation of ARGs. As demonstrated by prior studies, heavy metal resistance genes and ARGs frequently co-localize on identical genetic elements, allowing for the selection and co-regulated expression of ARGs under heavy metal stress[74] (Fig. 3b). Additionally, the interplay between ARGs and HMs is modulated by soil physical-chemical characteristics, especially pH, which governs the speciation of HMs. In acidic environments, the solubility of HMs such as As and Cd is elevated, leading to damage to bacterial cell membranes[72,75]. Xu et al. reported that Cu2+ concentration of 4 mg/L markedly increased the permeability of Escherichia coli cell membranes, thereby promoting the horizontal gene transfer of mobile genetic elements carrying ARGs[76]. Prolonged use of heavy metal-laden fertilizers in facility vegetable fields has fostered the survival and enrichment of "dual-resistant" microorganisms that carry both ARGs and heavy metal resistance genes. Compared to untreated fields, the proportion of these microorganisms increased by two to three times, with their abundance growing exponentially as HMs concentrations rose[77]. This co-selection mechanism enables HMs to indirectly facilitate the accumulation of resistance genes in soil, even in the absence of direct antibiotic exposure.

MNPs enhance ARGs spread via vectoring, biofilm protection, and microbial shift

-

The synergistic mechanisms between MNPs and ARGs in facility agricultural soils are mainly manifested in three aspects: (1) MNPs act as vectors, accelerating the horizontal transfer of ARGs; (2) MNPs biofilms serve as a survival barrier for ARGs hosts; (3) Exposure to MNPs alters microbial community structure, which in turn leads to the enrichment of ARGs hosts and promotes the spread and dissemination of ARGs (Fig. 3c). For example, Tavşanoğlu et al. revealed that the hydrophobic nature and extensive surface area of MNPs provide a favorable colonization habitat for antibiotic-resistant bacteria and ARGs, acting as vectors for ARGs transmission[78]. This collaboration establishes a "detrimental alliance" driving the proliferation and dissemination of ARGs. Additionally, biofilms that form on MNP surfaces can act as a protective shield for ARG hosts, enabling their survival and helping them evade the inactivating pressures of various environmental stressors, including antibiotics and HMs[79]. This was attributed to the abundant functional groups and active sites on the surface of MNPs[80], which provide physical protection for internal microorganisms[81] and promote the generation of antimicrobial resistance through the formation of dense biofilms. By comparing ARG abundance in plastisphere biofilms and quartz stone biofilms, Wang et al. confirmed that biofilms on the surface of MNPs are more suitable for ARG host colonization and proliferation[82].

Additionally, MNPs in soil interfere with the formation of soil aggregates and pore structures, creating new "microenvironments" that reshape microbial community structure[83]. Due to their hydrophobic nature and functional groups on their surfaces, MNPs efficiently enrich soil organic pollutants and heavy metal ions, exerting selective pressure that consequently leads to the enrichment of ARGs-host bacteria[84]. Meanwhile, these "microenvironments" can enhance the ecological niche of ARGs hosts[81]. Malla et al. demonstrated that ARGs are hosted by bacteria, including Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas, which are enriched on the surface of MNPs, as evidenced by metagenomic analysis. This enrichment led to an increase in the abundance of ARGs, such as tetA and sul1[85]. Hu et al. also found that adding MNPs to soil enriched host bacteria for ARGs, such as Nocardia and Amycolatopsis[86]. The "ecological succession of competition" between ARGs hosts and environmental bacteria exacerbates the spread and dissemination of ARGs in the environment.

While polystyrene MNPs at the nanometer scale (nanoplastics, NPs) significantly enhance HGT in Escherichia coli, with a much greater effect than microplastics (MPs)[87]. This may be attributed to the fact that, unlike MPs, NPs do not act as carriers that facilitate the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) to hosts. Instead, NPs exert their influence on ARGs hosts primarily at the molecular level. Li et al. demonstrated that NPs can significantly enhance bacterial antibiotic resistance through dual mechanisms: induction of oxidative stress and activation of efflux pumps, while also promoting the vertical inheritance and horizontal transfer of resistance genes[88]. Still, there remains a gap in comprehensive research regarding the influence of NPs surface properties, particle size effects, compositional characteristics, and environmental variations on their regulation of antibiotic resistance.

Overall, while the formation mechanisms of binary composite contaminations are generally well understood, further investigation is still needed to understand the differences in composite pollution arising from dynamic changes. Significantly, existing studies have mainly overlooked complex ternary composite contaminations, and their synergistic effects and underlying mechanisms demand systematic investigation and elucidation.

Potential mechanisms of ternary synergies

-

Ternary composite pollution, involving the synergistic interactions among HMs, MPs, and ARGs, poses a complex and emerging environmental challenge. While the coexistence of these pollutants is increasingly recognized, research on their synergistic effects remains limited, and the underlying mechanisms are largely unexplored. Based on the interaction mechanisms of binary pollutants, three potential mechanisms are proposed to drive the ternary synergistic effect: (1) Co-sorption: when HMs, MPs, and ARGs are simultaneously adsorbed onto the same surface through mechanisms such as surface site sharing, competitive coordination, and ion bridging, their bioavailability and mobility may be enhanced. (2) Biofilm-mediated Transfer: biofilms act as microhabitats, providing an ideal environment for the aggregation and co-transport of HMs, MPs, and ARGs, thereby facilitating their spread and persistence. (3) Redox Cycling: HMs can catalyze redox reactions that may alter the integrity of MPs or microbial activity, creating favorable conditions for the proliferation and transfer of ARGs. Overall, the ecological risks of ternary composite pollution in agricultural soils might far exceed the simple superposition of single-pollution effects.

-

Understanding the co-occurrence and migration-transformation mechanisms of composite pollutants is fundamental to addressing their environmental risks. However, these insights alone are insufficient without translating them into actionable pollution control strategies. Based on the comprehensive review of characteristics, migration and transformation patterns, and synergistic effects, it becomes clear that effective environmental risk management requires targeted interventions at critical nodes. The existing key control methods are as follows:

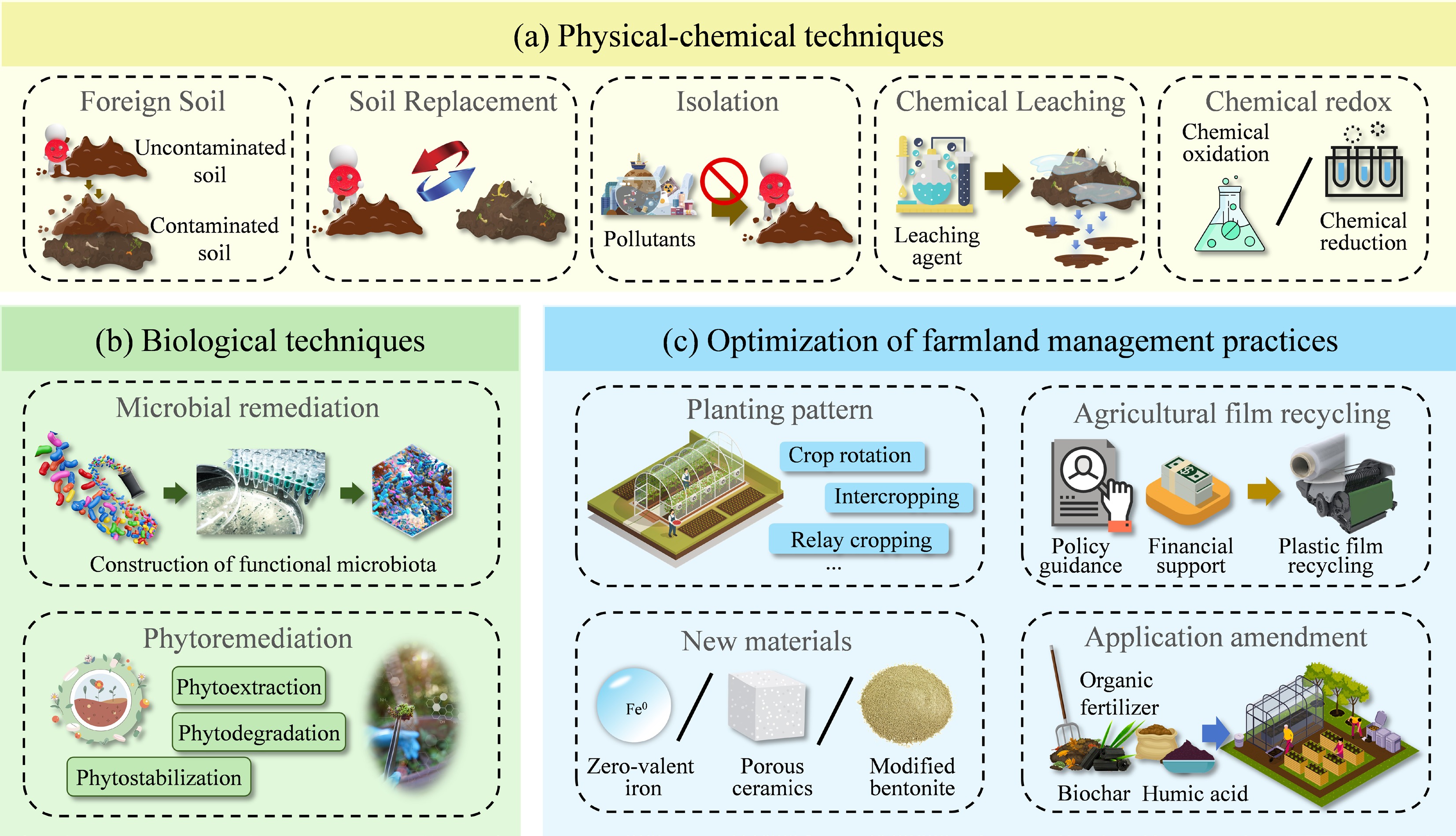

Physical-chemical techniques

-

Physical-chemical techniques play a pivotal role in pollution emergency response and process control due to their rapid response characteristics and effective intervention potential (Fig. 4a). The core of these technologies lies in using physical isolation, material replacement, or chemical transformation to block pollutant migration pathways or reduce their bioavailability. Currently, the mature physical barrier techniques include topsoil replacement, soil replacement, and barrier methods. Topsoil replacement primarily reduces exposure risk from surface contaminants by covering the contaminated area with uncontaminated soil. The soil replacement involves directly removing and replacing contaminated soil to achieve complete pollutant removal. The barrier method utilizes impermeable membranes, solidifying materials, and other barriers to prevent the migration of pollutants to deeper soil layers or groundwater[89]. Although these techniques are highly effective in heavily polluted areas, their high costs, the damage they cause to the original soil structure and ecological functions, and their limited applicability in large-scale remediation scenarios restrict their widespread use. It should also be noted that the soil replacement process may fail to restore the original soil microbial community and disrupt the original soil structure, thereby affecting the growth environment of crops.

Figure 4.

Mitigation strategies for composite contaminations in facility agriculture. (a) Physical-chemical techniques. (b) Biological techniques. (c) Optimization of farmland management practices.

Unlike physical barrier techniques, chemical barrier techniques focus on altering the chemical forms of pollutants, using methods such as chemical leaching and oxidation-reduction for effective remediation. These methods alter the chemical forms of pollutants through oxidation-reduction reactions, thereby reducing their mobility and toxicity. Like, NaClO treatment system can increase the dissolution rate of Zn and Ni to 75%–83%[90]. Faisal et al. Also showed that the removal efficiency of tetracycline by chemical adsorption was as high as 90%[91]. Although chemical techniques are highly effective at addressing large-scale composite soil contamination, they entail substantial risks of secondary pollution[92]. In general, physicochemical technologies remain the cornerstone of emergency response efforts, and their implementation requires thorough assessment and selection tailored to the unique characteristics of the contamination. Future directions should prioritize the development of integrated optimization approaches that combine physicochemical technologies with other remediation methods to attain efficient, safe, and sustainable pollution management objectives.

Biological techniques

-

Biological techniques primarily include microbial remediation and phytoremediation[93] (Fig. 4b). Microbial remediation degrades complex pollutants through the metabolic activities of functional strains. In earlier research, Kong et al. isolated a multifunctional bacterial strain, Mycobacterium sp. M-PE, from heavy metal-contaminated river sediments. This strain simultaneously carries laccase (a plastic-degrading gene) and arsC (an arsenic-detoxifying gene), allowing it to simultaneously mineralize polyethylene microplastics and detoxify arsenic (reducing As V to As III)[87]. This discovery provides a novel bioremediation strategy for addressing composite contaminations. However, individual strains exhibit limited environmental adaptability and functional stability, making it difficult for them to cope with the complex environment in which multiple pollutants coexist in facility agriculture. Although microbial communities exhibit functional diversity and a strong capacity to modulate host physiology, they are constrained by their inherent complexity and lack of controllability. Consequently, the design and construction of synthetic microbial communities (SynComs) have emerged as a prominent research focus for the biotechnological management of complex pollutants. SynComs achieve targeted modification of soil microbial communities by introducing specific pollutant-degrading bacteria, thereby enhancing pollutant degradation rates. For instance, Ruan et al.[94] engineered a consortium of three heavy metal-resistant bacteria, achieving a significant reduction of 4.5%–10.3% in bioavailable HMs in the soil. Nevertheless, microbial remediation technology faces practical limitations, including short-term efficacy and low treatment efficiency for recalcitrant pollutants[95].

Also, phytoremediation mainly relies on hyperaccumulators or tolerant plants to absorb, accumulate, and transform pollutants, such as Bidens pilosa L., Crassocephalum crepidioides, Rotala rotundifolia, and Myriophyllum aquaticum[96,97]. Cui et al. utilized the enrichment and adsorption of HMs and antibiotics by ryegrass and Indian mustard. They combined the two plants through intercropping to increase their antibiotic and HM accumulation[98]. The total accumulation of antibiotics increased by 27.37%–267.65%, thereby achieving the purpose of effectively reducing HMs and inhibiting the spread of bacterial resistance. However, improper disposal of these functionally absorbed plants after pollutant accumulation may lead to them becoming secondary pollution sources, with the potential to spread contaminants via the food chain and eventually endanger human health[99]. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the ecological risk assessment of introduced exogenous organisms is a critical component in the application of pollution remediation technologies. In agricultural systems, the introduction of exogenous functional plants or microbial strains without proper ecological adaptability evaluation may trigger biological invasions, leading to severe consequences such as declines in local diversity and degradation of ecosystem functions[100]. To balance remediation efficiency and ecological safety, recent advancements in genetic engineering and synthetic biology have focused on modifying strains and plants to enhance their ecological suitability and pollution remediation capabilities.

Optimization of farmland management practices

-

Currently, optimizing farmland management practices (Fig. 4c), such as planting pattern optimization and fertilization regime improvement, is considered a cost-effective and sustainable approach to mitigating composite contamination in facility agriculture. The scientific management of agricultural films and waste in facility vegetable fields is crucial for reducing composite contaminations from the source. Estimates indicate that over 70% of MNPs in agricultural lands originate from the improper use of agricultural films[101,102]. Promoting biodegradable agricultural films and enhancing the recycling of traditional plastic films can reduce MNPs residual by more than 80% at the source[103], while also mitigating the risks of HMs and bacterial antibiotic contamination associated with plastics. In recent years, with the rise of artificial intelligence, AI digital monitoring systems based on infrared sensors, the Internet of Things (IoT), remote sensing technologies, and machine learning algorithms have emerged as pivotal tools for the precise identification of composite pollution in facility agriculture. It aims to clarify pollution control targets and enable timely, or even preemptive, source-level risk management. For instance, Zhong et al.[104] used hyperspectral imaging, spectral inversion, and artificial neural networks to achieve large-scale remote sensing monitoring of heavy metal pollution in soil-crop systems. This approach facilitated the rapid diagnosis of ecologically critical areas, thereby enabling precise control of pollution risks.

Additionally, agricultural wastes (e.g., straw, livestock, and poultry manure) may contain HMs, ARGs, MPs, and other contaminants[105,106]. Directly returning these wastes to the field or leaving them exposed can lead to the accumulation of composite pollutants in the soil. Converting agricultural waste into organic fertilizer through composting, biogas fermentation, and other techniques can effectively reduce pollutants while improving soil organic matter. Studies have shown that composting not only reduces composite pollution but also enhances soil structure and increases organic matter content[107]. Although these measures can effectively reduce the input of exogenous contaminants, persistent contaminants in farmland, which are challenging to remove entirely, necessitate additional remediation efforts.

To address this, some scholars have proposed optimizing planting patterns to regulate soil structure and microbial communities, thereby blocking the migration and transformation pathways of exogenous pollutants. Common planting patterns include crop rotation, intercropping, and relay cropping. For example, paddy–upland rotation can promote the precipitation and transformation of heavy metals by altering soil redox conditions[108], while intercropping and relay cropping are considered effective in improving farmland biodiversity and microbial activity, thereby inhibiting the spread of composite pollutants[109]. Optimized cultivation management has significant potential to reduce composite contamination in facility farmlands by precisely regulating microbial community structure[110]. However, the regional adaptability of this technology faces critical challenges: due to significant differences in soil types, climatic conditions, and other regional factors, systematic research on optimized crop rotation and intercropping patterns for different regions remains insufficient, resulting in a lack of targeted application in practice.

Furthermore, optimizing fertilization strategies by scientifically adjusting the types, amounts, and methods of fertilization is an effective way to control composite contamination while improving soil fertility. For example, Zhang et al.[111] prepared alkylated sulfide nano-zero-valent iron (AS-nZVI) for fertilizer application, using electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions to rapidly enrich MNPs, achieving removal efficiencies of 99.6% and 98.2% for 2 and 10 μm MPs, respectively. Additionally, the reducing properties of zero-valent iron altered the morphology of HMs adsorbed on the surface of MNPs, efficiently detoxifying soil Pb2+ (undetected) and thereby enabling the synergistic treatment of composite pollution[111]. Moreover, struvite-loaded zeolite is effective at eliminating composite pollution in soil[112]. Soil amendments such as biochar and biological substrates are often used in conjunction with organic fertilizers to enhance pollution remediation. The combined application of organic fertilizer and biochar also resulted in a marked 61.54% reduction in ARGs compared to the sole use of chemical fertilizers[113]. Further research indicates that the combined use of apatite, biochar, and organic fertilizer not only improves soil physicochemical properties but also regulates microbial community structure, significantly reducing the accumulation and translocation of heavy metals in crops, thereby achieving effective remediation of heavy metal-contaminated soils. These technologies offer diverse solutions for composite pollution management and have significant application value (Table 2).

Table 2. Main measures to reduce composite pollution in farmland systems

Categories Technologies Main functions Advantages Disadvantages Ref. Physical-chemical technique √ Foreign soil method ● Replacing or physically isolating contaminated soil

● Blocking pollutant exposure pathways◆ Technological simplicity

◆ Rapid remediation● High cost

● Inadequate degradation[75] √ Soil replacement Method ◆ Complete remediation

◆ Rapid remediation● Extremely high costs

● Significant environmental risks√ Isolation method ◆ Low cost

◆ Significant ecological risk reduction● Inadequate degradation

● Restrictions on land reuse√ Chemical leaching Method ● Eluting pollutants with solvents ◆ Rapid remediation ● Destruction of soil ecosystems

● Risk of secondary pollution[76,77] √ Chemical redox ● Altering pollutant speciation via chemical reactions ◆ Minimal disturbance to soil structure ● Susceptible to soil interference

● Formation of toxic

by-productsBiological technique √ Microbial remediation ● Degrading pollutants through microbial metabolism ◆ Environmentally benign

◆ low cost● Long remediation cycle

● Susceptible to environmental conditions[80] √ Phytoremediation ● Utilizing hyperaccumulator or tolerant plants to absorb, accumulate, and transform pollutants ◆ Environmentally benign

◆ High public acceptance● Protracted remediation period [91,92] Optimization of farmland management measures √ Promotion of degradable agricultural film ● Reducing micro/nanoplastic pollution from agricultural film degradation ◆ Technological simplicity

◆ Recyclable● High cost

● Technical immaturity[98] √ Changing the planting pattern ● Ameliorate soil physicochemical properties and microbial diversity, and synergistically degrade and absorb pollutants ◆ Emphasizes source prevention

◆ Low cost

◆ Significant ecological benefits● Nutrient supply not synchronized with crop demand

● Protracted remediation period[102,103,105] √ New materials application ● Application of new materials to absorb or change the form of pollutants ◆ Environmentally benign

◆ Universally applicable● High cost

● Low technological maturity[106] √ Application of organic fertilizer with different amendments ● Ameliorate soil properties, alter bacterial communities, and reduce pollutant accumulation ◆ Environmentally benign

◆ Persistent efficacy● Vulnerable to environmental interference

● Lacking specificity[104,107] -

The present review provides a comprehensive overview of the contamination features, risk evaluation approaches, synergistic pollution mechanisms, and remediation strategies for composite contaminations (HMs, ARGs, and MNPs) in facility agriculture. Despite significant attention to binary composite contaminants, research on the effects and underlying mechanisms of ternary pollution remains scarce. Significant progress has been achieved in understanding the mechanisms underlying binary composite pollution. The behavior and forms of pollutants are influenced by a range of environmental factors. However, existing risk assessment methods often struggle to address both pollution effects and ecological risks simultaneously. Furthermore, these methods are often limited by technical constraints, including numerical dependence and static evaluation. In terms of control technologies, most efforts focus on single contaminants, with limited solutions for the synergistic management of composite contaminations, and challenges such as limited applicability, short-term effectiveness, and environmental compatibility remain unresolved. Future research for the control of composite contaminations in facility vegetable fields is proposed as follows:

(1) Verifying the co-occurrence, risk, and mechanisms of ternary composite pollutions. To comprehensively address ternary composite pollution, it is essential to first quantify the co-occurrence of HMs, MNPs, and ARGs across various environmental media. This foundational step will provide critical insights into the spatial and temporal patterns of ternary pollution and the factors driving their co-occurrence. Moreover, the complex interactions (synergistic or antagonistic) among HMs, MPs, and ARGs remain poorly understood. Additionally, practical and feasible methods for assessing the ecological risks of ternary composite pollution are lacking, particularly in dynamic and heterogeneous environments. Importantly, existing pollution treatment technologies are insufficient to effectively block the migration and transmission chains of this composite pollution. By quantifying co-occurrence patterns, a better understanding of the sources, pathways, and sinks of ternary pollution can ultimately inform more targeted risk assessment and mitigation efforts.

(2) Exploring the mechanisms and patterns of multi-medium migration and transformation of composite contaminations. The mechanisms of migration and transformation of composite contaminants across diverse environmental media, such as soil, water bodies, and the atmosphere, should be clearly articulated. Additionally, the interactions between contaminants across different media must be investigated to uncover the fundamental principles underlying the formation and evolution of composite contaminants. This understanding is essential for developing effective source control and comprehensive management strategies.

(3) Constructing risk assessment methods for composite contaminations within a multi-scenario framework. It is imperative to integrate multi-source data to develop sophisticated risk assessment methodologies for composite contaminations and to establish a comprehensive multidimensional evaluation index system. Furthermore, incorporating time-series forecasting models is necessary to dynamically assess the spatiotemporal evolution of pollutant concentrations, enabling accurate, timely risk early warning.

(4) Developing sustainable bio-ecological technologies for controlling composite contaminations. Priority should be given to screening and engineering microbial consortia with high efficiency in degrading specific contaminants to address composite pollution. A thorough investigation into the synergistic mechanisms between plants and microorganisms in pollutant interception is essential to provide theoretical support for the development of plant–microbe combined remediation technologies. The advancement of novel green materials (e.g., biochar, nanomaterials) should be promoted, and their integration with improved agricultural practices (e.g., crop rotation, cover crops) should be explored to construct composite pollution interception systems. Moreover, the development of novel green materials (e.g., biochar, nanomaterials) and the improvement of agricultural practices (e.g., crop rotation, cover crops) should be pursued to intercept composite contaminations. Integrating biological methods with physicochemical technologies, such as combining microbial remediation with nanomaterial adsorption, could enhance the overall effectiveness of composite pollution control.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: the first draft of the manuscript was written by Zhengzhe Fan, Ruolan Li; visualization and validation were performed by Yinuo Ding, Qifan Yang; writing-review & editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, and conceptualization were performed by Wei Liu, Houyu Li, Yan Xu. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study. All data cited in this review are derived from publicly available sources and are fully referenced in the manuscript.

-

This work was financially supported by the Open Fund of the Key Laboratory of JiangHuai Arable Land Resources Protection and Eco-Restoration (Grant No. ARPR-2024-KF04), the Young Scientists Fund (Category C) of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42507534), Youth innovation Program of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Grant No. Y2023QC32), and the Postdoctoral Fellowship Program (Grade C) of China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. GZC20241952).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Co-occurrence, risks, mechanisms, and control technologies of co-contamination are reviewed.

The synergistic effects of ternary composites remain poorly explored.

Risk assessment methods should evaluate co-contamination levels and ecological risks concurrently.

Sustainable bio-ecological technologies for composite pollution control should be developed.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Zhengzhe Fan, Ruolan Li

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Fan Z, Li R, Ding Y, Yang Q, Liu W, et al. 2025. Composite contaminations dilemma in facility agriculture: pollution characteristics, risk assessment, and sustainable control strategies. Biocontaminant 1: e023 doi: 10.48130/biocontam-0025-0024

Composite contaminations dilemma in facility agriculture: pollution characteristics, risk assessment, and sustainable control strategies

- Received: 21 October 2025

- Revised: 13 November 2025

- Accepted: 23 November 2025

- Published online: 18 December 2025

Abstract: Facility agriculture, as a cornerstone of modern high-efficiency agricultural production, is crucial for sustainable development. However, the irrational use of agricultural inputs (including fertilizers, pesticides, and plastic films), coupled with their characteristics of multiple cropping and enclosed environments, has led to the increasingly severe co-accumulation of contaminants, with the most prominent examples being heavy metals (HMs), antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), and micro/nanoplastics (MNPs). Their interactions and additive polluted effects present significant obstacles to the sustainability of facility agriculture. Targeting the co-occurrence of HMs, MNPs, and ARGs in facility farmlands, this study comprehensively investigates their co-occurrence, evaluates methodologies for assessing composite pollution risks, examines potential mechanisms, and reviews existing technologies for mitigating composite contamination. The combined effects of these pollutants enhance their individual effects and threaten human health through bioaccumulation in the food chain. While binary composite contamination mechanisms are well understood, the dynamic changes and synergistic effects of ternary composites remain poorly explored. Furthermore, existing risk assessment methods struggle to simultaneously evaluate contamination levels and ecological risks of multiple pollutants across diverse scenarios. Although physical-chemical-biological technologies have proven effective in controlling single pollutants, the synergistic control of composite pollution remains a technical bottleneck. To address these challenges, priority should be given to exploring multi-medium migration mechanisms, developing multi-scenario risk assessment methods, and advancing sustainable bio-ecological technologies for composite pollution control. This review offers both theoretical insights and practical guidance to advance the green, sustainable transformation of facility agriculture within the "One Health" framework.