-

Disposal of processing wastes generated from the fruit juice processing industries and throwaway containers used in the packaging of fast-moving consumable goods is a serious environmental problem. Wild pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) grown between the territories of Iran and the Northen Himalayas of India is utilized for the preparation of anardana or juice extraction on a commercial basis[1,2]. Processing wastes such as wild pomegranate seed residues left after juice extraction from the arils are full of bioactive components and dietary fiber, comprising significant amounts of lignin, cellulose, sterols, tocopherols, conjugated fatty acids, and polyphenolic compounds[3,4]. Pomegranate seeds comprise around 12% of the whole fruit, with antioxidant activity ranging from 26% ± 6.14% to 54% ± 12.20% and total phenolics ranging from 72.4 ± 10.02 to 73 ± 13.35 mg gallic acid equivalent (GAE)/g[5,6]. Consumption of food enriched with pomegranate seeds may prevent DNA damage, reduce cancer risk, and also reduce menopause symptoms[4], and it can be use for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes[7]. Pomegranate seed powder has been utilized for preparation of fortified cupcakes[6] and gluten-free cake[4].

The staple grain wheat (Triticum aestivum), whose refined flour is used for the preparation of popular bakery foods, is low in bioactivity but high in nutrients and calories. Milling wheat crops results in removal of the bran layer, thus reducing flour's nutritional value[8]. The quantity and quality of protein and, more specifically, the structure of gluten, which is created when gliadin and glutenin combine with water, determine the rheological characteristics of wheat dough[9,10]. Barley (Hordeum vulgare) is utilized commercially for malt and beer production, but now its consumption is rapidly increasing as it is a rich source of antioxidants and carbohydrates, including a soluble fiber called beta-glucan, which may control blood glucose levels and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol[8]. Barley also shows anticancer effects through immune system regulation and inhibition of cancer cells' growth and dissemination[11]. Barley has been successfully used as a replacement for wheat in the preparation of nutritious multigrain chappati and biscuits, as wheat contains less than 1% β-glucan content[8]. Barley flour, rich in fibers, can crack and crumble because of deficient amounts of gluten, which ensures that the dough rises in the baking process and keeps its shape[12].

Jaggery is a highly nutritive, highly antioxidant, and medicinal product that is rich in protein, minerals, vitamins, carbohydrates, and phenolic acid, among other nutrients[13]. Jaggery, prepared from sugarcane juice, is known as the healthiest sugar in the world possessing an adequate number of minerals (potassium, 1,056 mg per 100 g; magnesium, 70–90 mg per 100 g; calcium, 40–100 mg per 100 g; phosphorus, 20–90 mg per 100 g; sodium, 19–30 mg per 100 g; iron, 10–13 mg per 100 g; zinc, 0.2–0.4 mg per 100 g, etc.), vitamins (A, 3.8 mg per 100 g; B1, 0.01 mg per 100 g; B2, 0.06 mg per 100 g; B5, 0.01 mg per 100 g; B6, 0.01 mg per 100 g; C, 7.00 mg per 100 g; D, 6.50 mg per 100 g; E, 111.30 mg per 100 g), and protein (280 mg per 100 g jaggery) all of which are necessary for the regular growth and function of human health[14,15].

Edible bowls has gained importance because of urbanization, busy lifestyle, and changes in eating patterns. Some encouraging studies have recently surfaced. For example, edible bowls made from Clitoria ternatea anthocyanins were incorporated into edible spoons made from kodo millet starch[16]. Other studies have used acorn, pumpkin seeds, poppy seeds, and wheat to make edible spoons[17]; ragi, wheat, and rice flours[18]; green composites of rice flour[19]; mosambi peel and sago powder for edible spoons[20]; wheat flour, finger millet, and rice flour-based bowls[21]; edible spoons fortified with Withania somnifera root powder[22]; pineapple core and pomegranate peel powder-based tableware[23], spent fortified brewer's grain-based edible bowls[24]; and grape, proso millet, wheat, xanthan and palm oil mixed to make edible spoons[25]. These have great potential to actively raise awareness of the environmental problems associated with single-use plastic bowls[26]. Eco-friendly bowls such as innovative edible and biodegradable tableware using bio-based materials or processing industry wastes can help manage the disposal of solid waste, which is a major source of environmental pollution. Therefore, to overcome the health and environmental problems caused by plastic bowls, the present study focused on the development of eco-friendly, bio-degradable, edible bowls from wild pomegranate seeds generated as a waste byproduct after juice extraction, combined in varying amounts with barley and wheat flour.

-

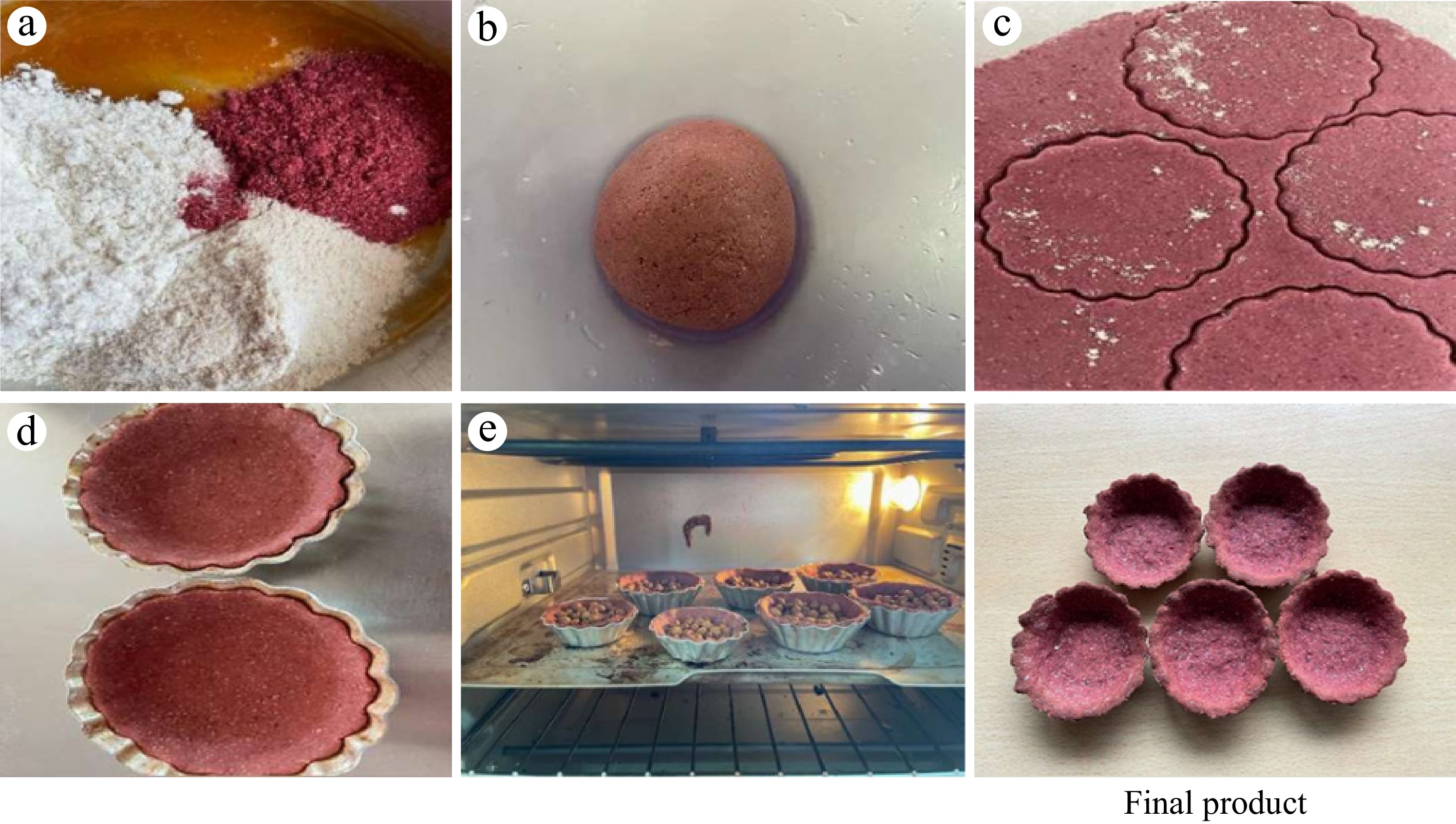

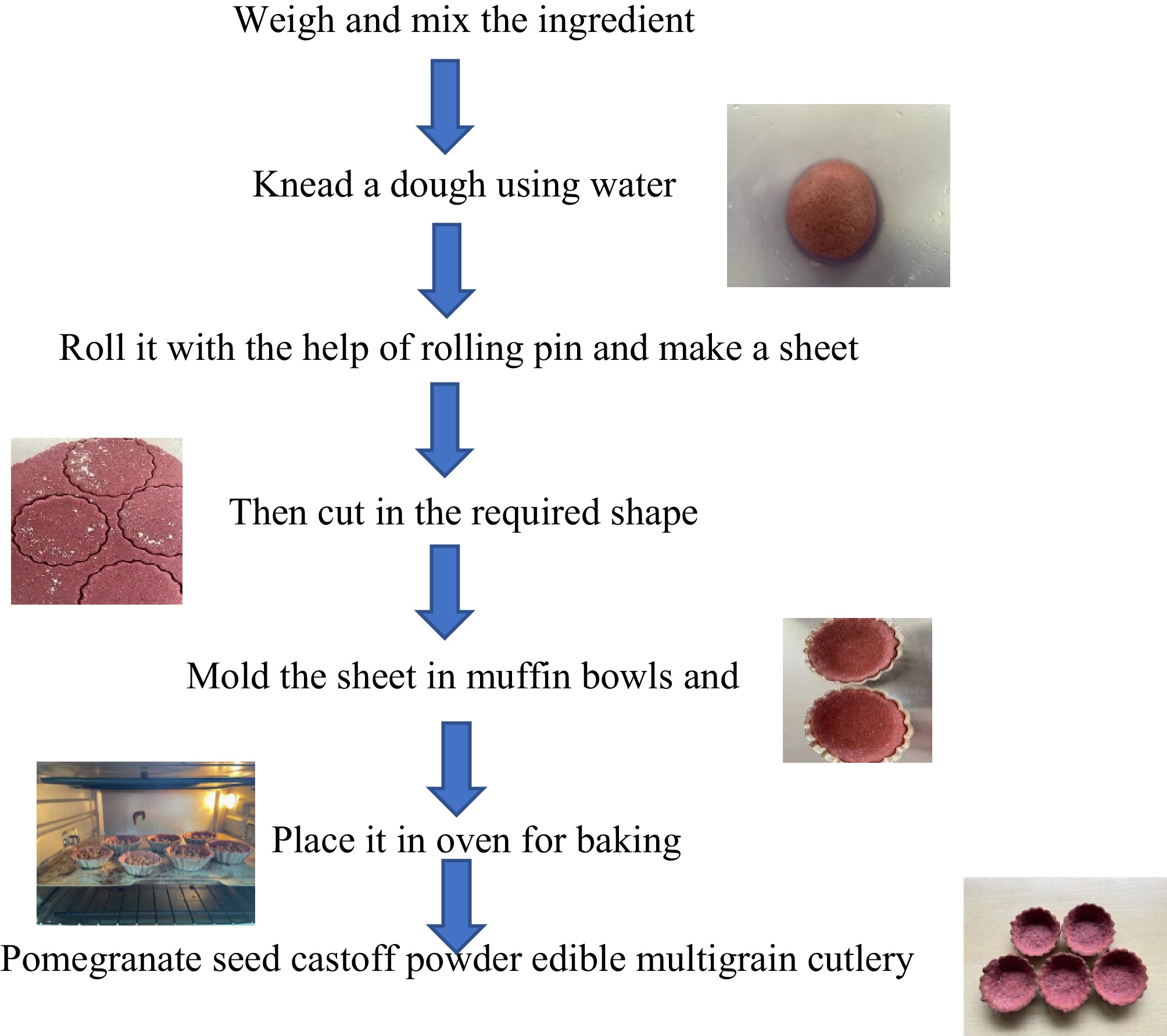

Wild pomegranate seeds left as processing waste after juice extraction were collected from a nearby juice shop, and wheat flour, barley flour, and jaggery were procured from the local market of Solan, Himachal Pradesh. Pomegranate seeds left after juice extraction were dried in a cabinet dehydrator at 60 °C then ground into a powder. Barley flour at 50% and wheat flour at 25% was used as a control treatment for edible bowls; in the other treatments, wheat flour was kept constant and barley flour was replaced with wild pomegranate seed powder at concentrations of 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20%, referred to as T1, T2, T3, and T4 respectively. Jaggery at the rate of 25% was also added to enhance the flavour and binder of edible bowls (Table 1). The flowchart is also added regarding the different steps for edible bowls preparation (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Composition of pomegranate seeds powder, wheat flour, barley flour, and jaggery used in different edible bowls treatments.

Ingredients Control T1 T2 T3 T4 Barley (g) 50 45 40 35 30 Wheat (g) 25 25 25 25 25 Jaggery (g) 25 25 25 25 25 Pomegranate seeds powder (g) − 5 10 15 20

Figure 1.

Flowchart of different operations for the preparation of multigrain edible bowls made from pomegranate seed powder.

Wild pomegranate seed powder, wheat flour, barley flour, and jaggery were measured and mixed in a bowl. The dough was kneaded with water and given 30 minutes to rest so that the water was fully absorbed and the dough became simpler to handle. Using a rolling pin, the dough was transformed into a sheet, which was then sliced into uniform-sized balls so that bowls could be made using moulds. The overall process of developing edible bowls is presented in Fig. 2.

-

In order to evaluate the efficiency of edible bowls, the following tests were performed.

Moisture content

-

Moisture analysis was performed by placing 2 g of each sample in a hot air oven at 110 °C for 1 h. After that, the sample was placed in a desiccator to cool down, then the final weight of the sample was taken[23].

$ {\rm Moisture\;{\text{%}}=\dfrac{Weight\;of\;sample\;before\;drying\,-\,Weight\;after\;drying}{Weight\;of\;sample}\times 100} $ (1) Ash content

-

To check the ash content, 1 g of the sample in a silica crucible was placed in a muffle furnace at a temperature of 600 °C for 1 h. After that, the inorganic residue was weighed[23].

$ \mathrm{Ash}\; \text{%}=\dfrac{\mathrm{Weight\; of\; ash}\; \left(\mathrm{g}\right)}{\mathrm{Weight\; of\; sample\; }\left(\mathrm{g}\right)}\times100 $ (2) Crude fiber

-

The crude fiber was determined using 0.5 g of the sample, to which 5 mL of 1.26% diluted H2SO4 was added and refluxed for 15 min. After filtering, 5 mL of a 1.26% NaOH solution was added to the filtrate, which was then refluxed for an additional 15 min. After the mixture was filtered once more, the filtrate was refluxed for 15 min and cleaned with ethanol. After further filtering, it was given 15 min to dry. The residue that was recovered was weighed to determine the fiber content[23].

Total phenolic content

-

The total phenolic content (TPC) was determined by the Folin–Ciocalteu method, and the absorbance was measured at 725 nm. TPC was expressed as GAE and the concentration of gallic acid[27].

Antioxidant activity analysis

-

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) is one of the common and simple colorimetric methods for assessing the antioxidant capabilities of pure compounds. It is frequently used to measure the ability of an antioxidant molecule to scavenge free radicals. A methanol extract (0.1 mL) was mixed with 3.9 mL of a solution containing 6 × 10−5 mol/L DPPH. Methanol was used as a blank, and the powder sample and DPPH was kept in the dark for around 30 min for incubation, then the absorbance was measured at 515 nm. Antioxidant activity was recorded as the percentage of discoloration[28].

$ \mathrm{Antioxidant\; \text{%}}=\mathrm{\dfrac{Absorbance\; of\; blank\, -\, Absorbance\; of\; sample}{Absorbance\; of\; blank}}\times100 $ (3) Water absorption test

-

The water absorption test was performed by filling 20 mL of water inside the bowls for 30 min. Afterwards excess water was removed from the surface. The final weight of the bowls was then noted and the percentage of total water absorbed by the bowls was calculated by using the formula[24]:

$ \begin{split} & {\text{%}}\; \mathrm{Water\; absorption}= \\ &{\mathrm{\dfrac{\mathrm{Weight\; after\; water\; absorption\, }-\, Weight\; before\; water\; absorption}{Weight\; before\; water\; absorption}}}\times 100 \end{split} $ Oil absorption test

-

The oil absorption of the bowls was determined by filling 10 mL of sunflower oil inside a sample for about 60 minutes. Then excess oil was removed from the surface by decanting the oil. The final weight of the bowl was then noted and the percentage of total oil absorbed by the bowls was calculated[24] by using the formula:

$ \begin{split} & {\text{%}}\; \mathrm{Oil\; absorption}= \\ &{\dfrac{\mathrm{Weight\; after\; oil\; absorption\, }-\, \mathrm{Weight\; before\; oil\; absorption}}{\mathrm{Weight\; before\; oil\; absorption}}}\times 100 \end{split} $ Texture analysis

-

The texture profile analysis (TPA) was done with a texture analyzer (Stable Microsystem, UK). To determine hardness, the sample was placed below the probe, and the force required to break the sample was noted. The hardness of each sample was measured in kgf[29].

Biodegradation test

-

The biodegradability test was done by burying the multigrain bowl sample in 1 kg of soil with pH 6.5, 78% relative humidity, and a moisture content of 36%. The initial weight of the multigrain bowl was recorded after drying it for 24 h at 40 °C in a drying oven until its weight becames constant, then the multigrain samples were buried in the soil for 15 days. They were then cleaned with distilled water and dried for 24 h at 40 °C in an oven. Before being weighed again, they were kept for 24 h in a desiccator until the final weight was constant[30].

$\begin{split}&\mathrm{W}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{g}\mathrm{h}\mathrm{t}\;\mathrm{l}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{s}\mathrm{s}\;\left({\text{%}}\right)=\\&\dfrac{\mathrm{W}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{g}\mathrm{h}\mathrm{t}\;\mathrm{b}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{f}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{e}\;\mathrm{b}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\;\mathrm{s}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{l}-\mathrm{W}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{g}\mathrm{h}\mathrm{t}\;\mathrm{a}\mathrm{f}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{r}\;\mathrm{b}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}\;\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\;\mathrm{s}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{l}}{\mathrm{W}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{g}\mathrm{h}\mathrm{t}\;\mathrm{a}\mathrm{f}\mathrm{t}\mathrm{e}\mathrm{r}\;\mathrm{b}\mathrm{u}\mathrm{r}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{a}\mathrm{l}\;\mathrm{i}\mathrm{n}\;\mathrm{s}\mathrm{o}\mathrm{i}\mathrm{l}}\times 100 \end{split}$ Fourier transform infrared

-

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) measurements were made with an IRSpirit (Shimadzu) spectrometer and then averaged after undergoing Fourier processing. Thermo Fisher Scientific's Grams/AI 8.0 software was used for process and analysis. FTIR spectroscopy was performed using a pinch of a powdered sample of each composition mixed with potassium bromide to form a pellet, then the sample was read to identify the chemical bonds present in a molecule via the infrared absorption spectrum[31].

Sensory analysis

-

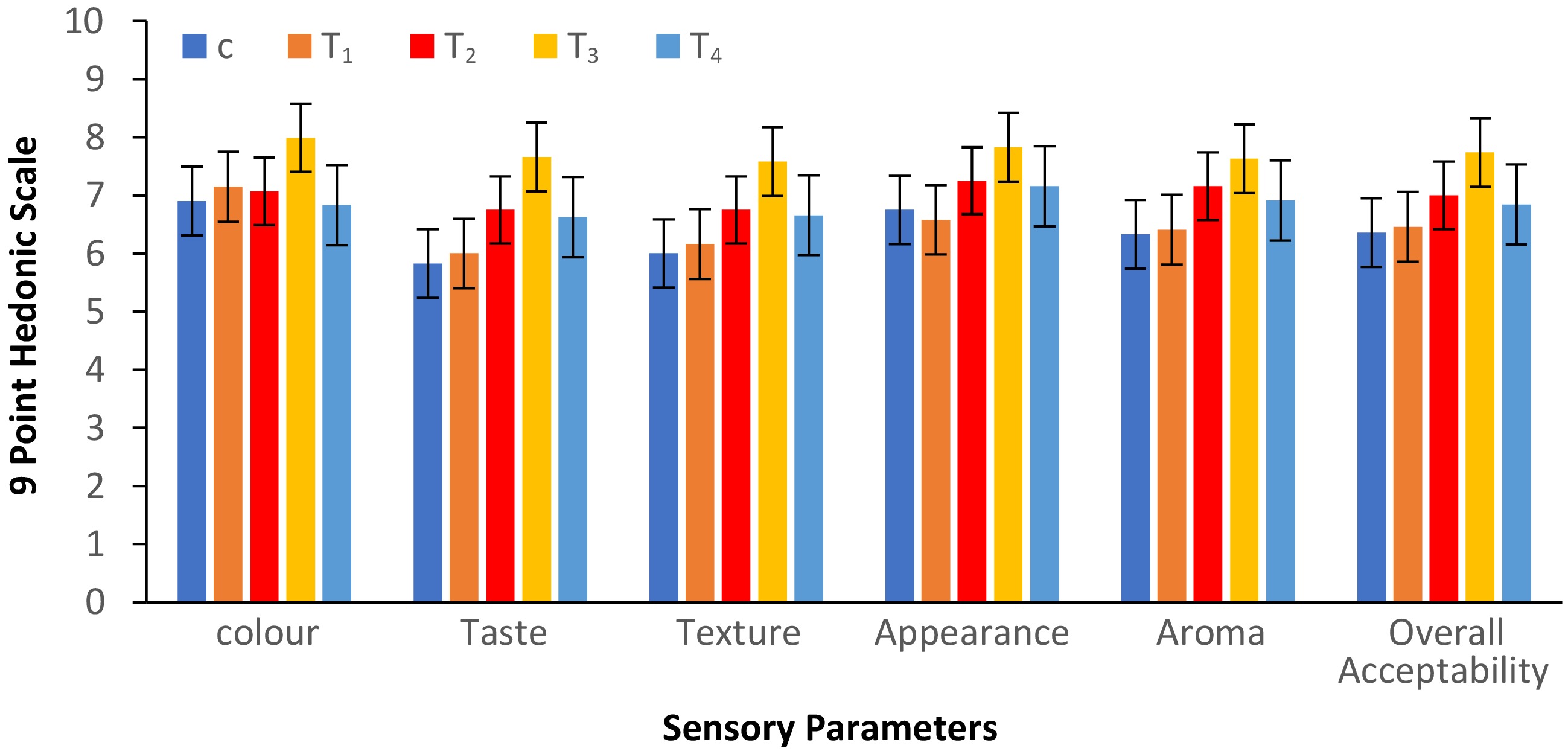

A nine-point hedonic scale was used for the sensory evaluation, in which 10 panelists from the School of Bioengineering and Food Technology, Shoolini University, were given samples of wild pomegranate powder-based multigrain bowls to determine the organoleptic score for each attribute[32].

-

The data in Table 2 revealed that the moisture content of pomegranate seeds was 4.45% ± 0.29%, TPC measured 1,380.55 ± 11.89 µg GAE/g dry weight, and antioxidant activity was 33.03% ± 1.17%. The antioxidant activity was 53.98% ± 2.39% for barley flour, 13.03% ± 0.31% for wheat flour, and 56.51% ± 2.07% for jaggery. In earlier studies, fiber was recorded as 1.33% ± 0.13% in wheat flour and 17.13% ± 1.6% in pomegranate seed powder[6]. The ash content in pomegranate seed powder was recorded as 1.49% ± 0.02%, and the moisture content was 6.87% ± 0.01%[33]. The TPC of wheat flour was 885 µg (GAE)/g[34], and the antioxidant activity of wheat and whole barley flours was recorded as 2.03% ± 0.83% and 41.5% ± 2.5% (dry weight basis), respectively[35].

Table 2. Physicochemical properties of wheat flour, barley flour, jaggery, and pomegranate seeds.

Parameters Barley flour Wheat flour Jaggery Pomegranate seeds powder Moisture content (%) 8.50 ± 0.33 9.56 ± 0.39 5.12 ± 0.28 4.45 ± 0.29 Ash content (%) 2.82 ± 0.38 0.70 ± 0.01 0.04 ± 0.01 1.70 ± 0.09 Crude fiber (%) 4.07 ± 0.16 1.33 ± 0.05 0.71 ± 0.03 21.33 ± 1.37 Total phenols (µg GAE/g dry wt) 365.47 ± 18.87 863.87 ± 24.13 3,834.98 ± 57.36 1,380.55 ± 11.89 Antioxidant activity (%) 53.98 ± 2.39 13.03 ± 0.31 56.51 ± 2.07 33.03 ± 1.17 Proximate analysis of pomegranate powder-based multigrain edible bowls

-

The control and pomegranate powder-based edible bowls were analyzed for different characteristics, and the results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Characterization of pomegranate powder-based multigrain edible bowls.

Parameters Treatments Control T1 T2 T3 T4 Moisture content (%) 9.69 ± 0.51 10.09 ± 0.70 12.47 ± 0.95 13.11 ± 0.50 13.50 ± 0.46 Ash content ( %) 0.71 ± 0.04 1.02 ± 0.06 1.11 ± 0.05 1.17 ± 0.07 1.21 ± 0.08 Crude fiber (%) 0.64 ± 0.05 1.85 ± 0.11 2.98 ± 0.14 4.73 ± 0.20 6.29 ± 0.24 Total phenolic content (µg GAE/g dry wt) 1,151.04 ± 11.04 1,397.64 ± 15.54 1,439.17 ± 17.39 1,502.22 ± 21.02 1,552.62 ± 21.67 Antioxidant activity (%) 32.80 ± 1.04 38.22 ± 1.82 42.63 ± 2.06 46.84 ± 2.19 49.21 ± 2.36 Water absorption capacity (%) 15.12 ± 0.32 11.16 ± 0.44 10.02 ± 0.40 9.77 ± 0.60 7.64 ± 0.43 Oil absorption capacity (%) 15.67 ± 0.65 13.39 ± 0.35 10.24 ± 0.21 8.83 ± 0.16 5.73 ± 0.13 Hardness (Kgf) 1.41 ± 0.17 2.75 ± 0.23 3.91 ± 0.24 4.69 ± 0.28 2.33 ± 0.23 Biodegradability (%) 26.76 ± 1.03 29.72 ± 1.18 34.68 ± 1.25 37.53 ± 1.29 40.46 ± 1.69 Moisture content

-

The moisture content of pomegranate seed powder-enriched multigrain bowls was in the range of 9.69% ± 0.51% to 13.50% ± 0.46%, with that of the T4 treatment being 13.50% ± 0.46%, which was substantially higher than that of the T1 treatment (10.09% ± 0.70%) and the control (9.69% ± 0.51%). However, the increased moisture content of the edible bowls might be caused by the increased absorption of water by the crude fiber present in pomegranate seed powder, affecting its general functionality, durability, and texture. A similar increase in moisture content was recorded in earlier studies on pomegranate seed powder and defatted soybean flour cookies[36], showing significant variation (e.g., V3 had a higher moisture content of 7% ± 0.01% compared with V1 1.25% ± 0.02%)[23]. In the case of edible bowls, spoons fortified with Withania somnifera root powder showed the lowest moisture content of 3.70% in Sample 0, whereas Samples 3 and sample 4 had higher and similar moisture levels of 4.40% and 4.30%, respectively[22].

Ash content

-

The ash content of the treatments, including the control and pomegranate seedtreatments was in the range of 0.71% ± 0.04% to 1.21% ± 0.08%. In comparison with the pomegranate seed-supplemented samples, the control treatment had the lowest ash concentration (0.71% ± 0.04%), indicating a lower mineral content. The other treatments revealed varying amounts of ash content: T1 had 1.02% ± 0.06%, T2 had 1.11% ± 0.05%, T3 had 1.17% ± 0.07 %, and T4 had the greatest amount at 1.21% ± 0.08%. This could be ascribed to the greater quantity of minerals in the pomegranate seed powder. These findings show that adding barley flour and pomegranate seed powder for fortification raises the edible bowls' mineral content, potentially increasing their nutritional value. Edible bowls made by using fruit wastes showed a greater ash content than that in the present study[23]. Similar results were found for edible bowls[21], with S3 having a higher ash content of 1.97% compared with S1 with an ash content of 0.83%.

Crude fiber

-

Along the same lines, an increase in pomegranate seed powder resulted in an elevation in the crude fiber content of the edible bowls, namely 0.64% ± 0.05% in control followed by 1.85% ± 0.11%, 2.98% ± 0.14%, 4.73% ± 0.20%, and 6.29% ± 0.24% in multigrain edible bowls made with 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% waste pomegranate seed powder, respectively. This may be caused by the addition of waste pomegranate seed powder, which is a rich source of fiber. A similar increase in fiber content was recorded in cookies containing pomegranate seed powder and defatted soybean flour[35]. The increase in fiber content was also recorded after the enrichment of gluten-free cake with pomegranate seed powder with optimized treatment showing 4.14% ± 0.02% compared with the control (3.26% ± 0.09%)[7].

Total phenolic content

-

The TPC in edible bowls (Table 3) was recorded in the range of 1,151.04 ± 11.04 to 1,552.62 ± 21.67 µg GAE/g dry weight. The increase in the concentration of pomegranate seed powder in the multigrain edible bowls resulted in a gradual increase in TPC: T1 = 1,397.64 ± 15.54 µg GAE/g dry weight, T2 = 1,439.17 ± 17.39 µg GAE/g dry weight, T3 = 1,502.22 ± 21.02 µg GAE/g dry weight, and T4 = 1,552.62 ± 21.67 µg GAE/g dry weight. This increase in concentration was caused by the addition of pomegranate seed powder, but this was low compared with the individual total phenolic content of the raw ingredients, as phenolic compounds are thermally sensitive, and heating them above 150 °C results in their thermal degradation[37]. A similar increase in TPC was recorded in a study incorporating acorn, pumpkin, and poppy seed flour for the preparation of spoons, with the TPC ranging from 0.67 ± 0.04 to 14.04 ± 0.25 mg GAE/g among the different spoons[17].

Antioxidant activity

-

The findings showed that, depending on the treatment, antioxidant activity varied from 32.80% ± 1.04% to 49.21% ± 2.36%. The antioxidant activity of the control treatment was 32.80% ± 1.04%; however, the treatments with increased waste pomegranate seed powder revealed greater activities: T1 = 38.22% ± 1.82%, T2 = 42.63% ± 2.06%, T3 = 46.84% ± 2.19%, and T4 = 49.21% ± 2.36%. These changes can be linked to the presence of foods with a high antioxidant content such as barley, jaggery, and wild pomegranate seed powder. Similarly, edible spoons fortified with Indian ginseng roots showed similar results; e.g., Sample 4 had the highest antioxidant activity compared with the control[22]. Similar concentration-dependent increases in antioxidant activity have been recorded in spoons prepared by the addition of pumpkin seed, poppy seed and acorn flours, determined via a ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) assay with values ranging between 0.55 ± 0.00 and 127.30 ± 2.31 µmol TE/g[17].

Water absorption test

-

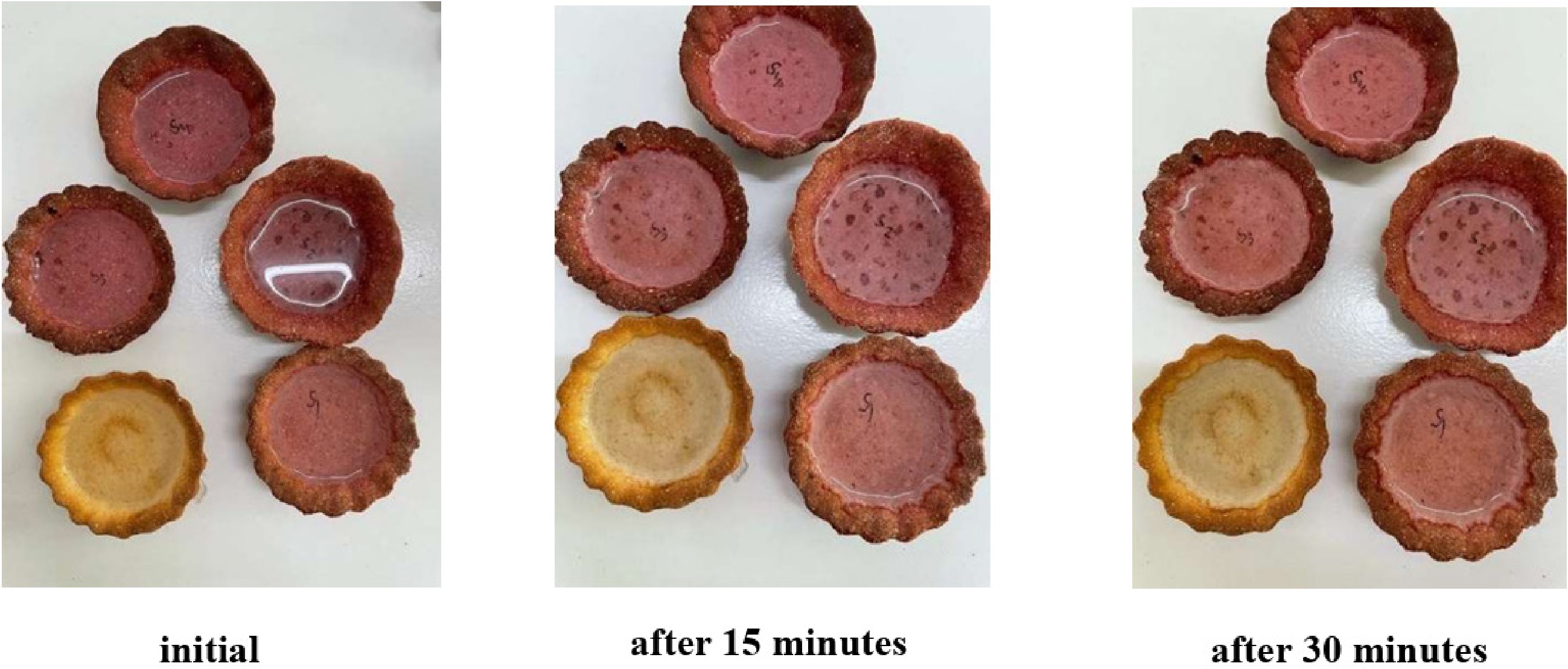

The water absorption test (Fig. 3) was performed to determine the strength of the bowls by observing how much time it took for one bowl to absorb water and start dissolving, because the longer the bowls take to dissolve, the longer they last. This revealed important information about their water resistance. The water absorption rate of the T4 sample was 7.64% ± 0.43%, which was substantially lower than that of the T1 treatment (11.16% ± 0.44%) and the control (15.12% ± 0.32%). The T4 treatment with an increased concentration of waste pomegranate seed powder was proposed as the cause of this decrease in water absorption, as pomegranate seeds are rich in fiber. Therefore, replacement of the starch by fiber components resulted from an increased amount of waste pomegranate seed powder in the mixture for the preparation of multigrain bowls, which reduced the availability of the starch granules for gelatinization. Furthermore, multigrain (little, kodo, and barnyard millet) edible bowls exhibited a twofold decrease in water absorption properties in comparison with the control[38]. A similar decrease in water absorption in edible bowls was observed in earlier research that used Brewer's Spent Grain (BSG), ragi flour, and refined wheat flour[24]. In edible and biodegradable bowls from morning glory (Ipomoea aquatica), glycerol, and soy protein isolate, the water absorption capacity decreased from 26.9% to 18.3% compared with the control[39]. Similarly, it was observed in the case of edible bowls made from rice flour, millet flour, wheat flour, and banana blossom paste, the water absorption decreased from 31.59% to 27.11%[21].

Oil absorption test

-

The results revealed that the oil absorption capacity decreased from the control treatment (15.67% ± 0.65%) to the waste pomegranate seed-fortified samples, with the T4 treatment showing the lowest value at 5.73% ± 0.13%. This pattern implied that a decrease in the samples' ability to absorb oil was the outcome of an increase in the concentration of waste pomegranate seed powder, because the enriched samples had a higher fiber content. In the case of edible bowls fortified with spent brewer's grain, the inclusion of spent brewer's grain reduced the oil absorption[24]. The studies conducted on edible bowls made from little, kodo, and barnyard millet also showed less oil absorption, about three times lower than the control[38].

Texture profile analysis

-

The TPA technique was used for assessing the hardness of the samples, expressed in Kgf, by putting the sample under a probe and measuring the force needed to break it. The procedure provides an objective assessment of the textural properties of the sample. The findings of this study's texture analysis showed significant variations between the different treatments, with the control showing 1.41 ± 0.17 Kgf, T1 with 2.75 ± 0.23 Kgf, T2 with 3.91 ± 0.24 Kgf, and T3 4.69 ± 0.28 Kgf; T4 was somewhat lower at 2.33 ± 0.23 Kgf. The addition of wild pomegranate seed powder up to 15% improved the structural hardness of baked wild pomegranate seed-based multigrain bowls, making it suitable for crunchy or firm-textured items containing dietary fiber and the seeds' microstructure, which reinforces the baked matrix. A further increase to 20% wild pomegranate seed powder may interrupt the formation of the gluten or starch matrix, resulting in brittleness and thus reducing hardness, potentially because of matrix disruption. The study conducted on the addition of acorn, pumpkin, and poppy seed flour to make spoons yielded numerically higher hardness values relative to the control sample, with hardness ranging between 1,134.6 ± 623.5 and 10,330.4 ± 1,808.7 Kgf[17]. The results of the previous study[7] showed increased hardness in optimized pomegranate seed powder-enriched gluten-free cake (3.25 ± 0.75 Kgf) compared with the control (2.30 ± 0.82 Kgf) The increased hardness of the BSG-fortified edible bowls also showed the relationship between objective textural metrics[24].

Biodegradation test

-

Burying edible bowls in soil and tracking the weight loss at intervals of 15 d made it possible to evaluate the bowls' biodegradability over time. The study's findings show the breakdown of the edible bowls' structure during the biodegradation process. In particular, the study discovered that the biodegradability of the T4 sample was 40.46% ± 1.69% in just 15 d, indicating that it would quickly decompose. The biodegradability of the control treatment was 26.76% ± 1.03%; however, the biodegradability of T1, T2, T3, and T4 showed an increasing trend of 29.72% ± 1.18%, 34.68% ± 1.25%, 37.53% ± 1.29%, and 40.46% ± 1.69%, respectively. These results are remarkable because they show that the edible bowls' constituents are all biodegradable and environmentally friendly, offering a viable substitute for plastic utensils, which do not biodegrade during the same time period. An earlier study found similar biodegradability in a Moringa oliefera pod husk spoons in 3 weeks[40]. In an earlier study on BSG-fortified edible bowls, biodegradation was observed to be 30% in 10 weeks, also using the soil burial method[24].

FTIR spectroscopy

-

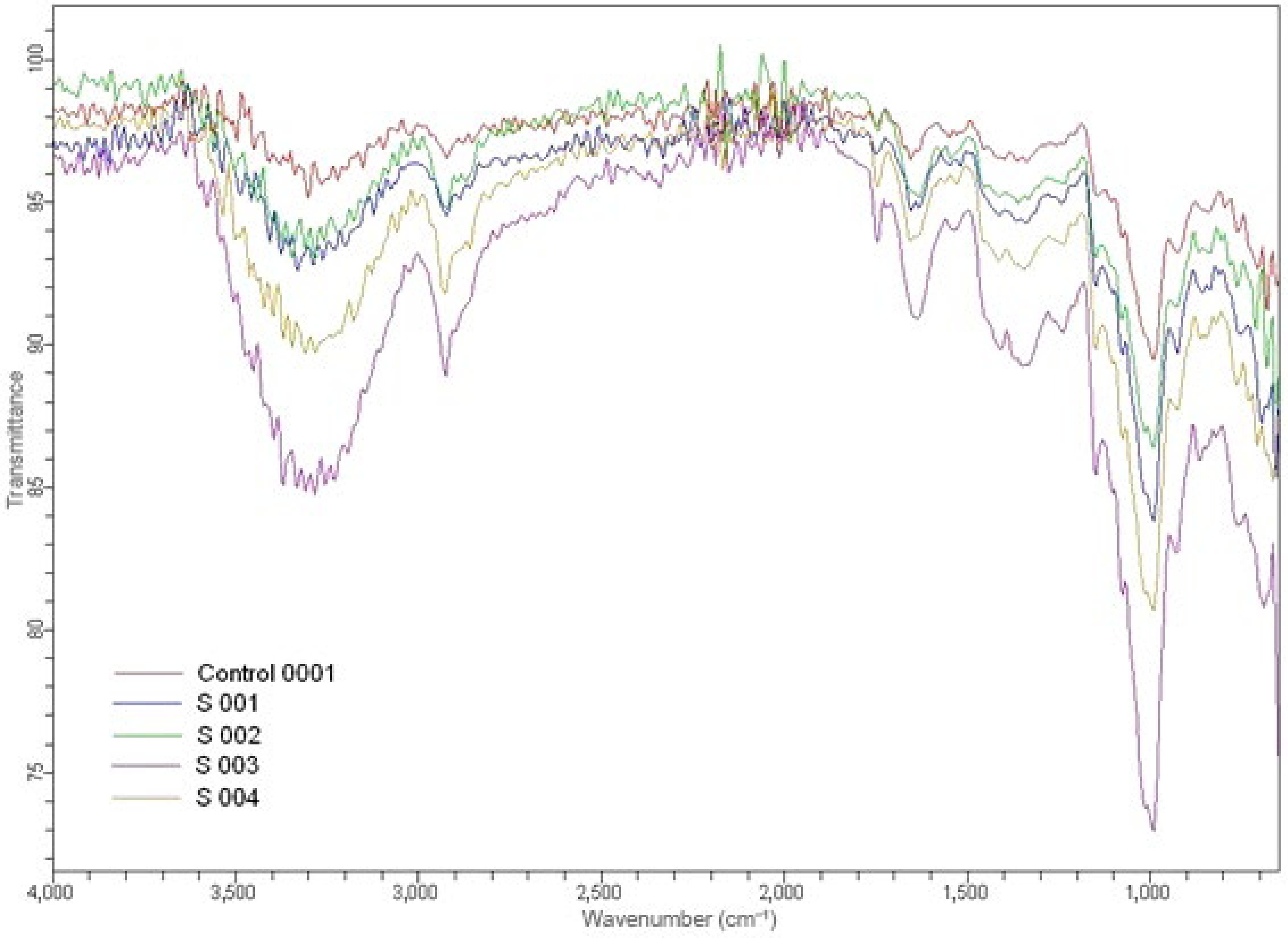

FTIR spectroscopy is utilized to analyse the chemical makeup of food products, identify contaminants and identify functional groups. The FTIR spectrum of the control sample (Control 0001 in Fig. 4) with 0% pomegranate seed powder showed a baseline with the lowest O–H, C=O, and fingerprint peak intensities. S 001 from T1 with 5% wild pomegranate seed powder showed a slight increase in the O–H and C=O bands. S 002 from T2 with 10% wild pomegranate seed powder showed a noticeable increase in the fingerprint region's complexity. S 003 from T3 with 15% wild pomegranate seed powder showed a clear increase in aromatic and carbonyl peaks, and S 004 from T4 with 20% wild pomegranate seed powder showed the strongest absorption in the O–H, C=O, aromatic, and fingerprint regions, revealing the highest polyphenolic and fiber content. Earlier FTIR studies of pomegranate seed powder demonstrated vibrational bands of O–H and C–H stretching (3,800–2,600 cm−1), C=O stretching of lipids (1,740 cm−1), C=C and Amide I (1,650–1,600 cm−1), CH2/CH3 bending (1,450–1,370 cm−1), and C–O and C–O–H vibrations (1,100–1,000 cm−1)[41].

Figure 4.

FTIR peaks of multigrain pomegranate seed powder-enriched bowls. Control 0001, control; S 001, T1; S 002, T2; S 003, T3; S 004, T4 (0%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% wild pomegranate seed powder, respectively).

Sensory evaluation of edible bowls

-

In order to assure the acceptability of the edible bowls, sensory analysis was essential for product evaluation. Among the control and the four treatments, T3 was the most preferred, with the highest overall acceptability score of 7.73 ± 0.68, whereas T1 scored 6.46 ± 0.56, T2 scored 7.00 ± 0.58, and T4 scored 6.84 ± 0.67; the control had an overall acceptability score of 6.35 ± 0.67 (Fig. 5). According to the findings of the sensory evaluation, for T3, with 15% wild pomegranate seed powder, the scores were as follows: color, 8.00 ± 0.71; taste, 7.66 ± 0.75; texture, 7.58 ± 0.54; appearance of the bowls' shape, 7.83 ± 0.51; aroma, 7.63 ± 0.59. These scores were recorded on a hedonic scale out of a possible 9. These findings demonstrate that in comparison with the control and other treatments, the adjustments made to T3 resulted in appreciable gains in sensory qualities. Further incorporation of pomegranate seed powder decreased the sensory score drastically and the edible bowls were unacceptable because of the irregular shape, the coarse mouthfeel, and being more prone to breakage. Previous studies also showed a similarity to the current research, in which the incorporation of pomegranate seed powder to gluten-free cake demonstrated that the acceptability increased to 4.02 ± 0.43 in comparison with the control (3.52 ± 0.71)[7]. In another earlier study, edible bowls prepared from 75% rice flour and 25% defatted rice bran showed the highest overall preference (6.46 ± 1.75)[19]. The overall acceptability of biodegradable bowls with 0% dried banana blossom powder was found to be as high as 7.45 compared with the other treatments with 5% powder (7.27) and 10% powder (7.09)[21]. The overall acceptability was recorded in the range of 5.33 ± 1.63 to 7.33 ± 1.63 in research on the development of edible spoons utilizing acorn, pumpkin, and poppy seed flours[17].

-

The present study concludes that edible multigrain bowls prepared by adding castoff waste byproducts from fruit juice, namely pomegranate seed powder, is a viable sustainable approach for valorization of solid waste within the fruit processing industrt. The addition up to 15% pomegranate seed powder into the multigrain bowls' formulation not only enhanced the nutritional value by enriching it with dietary fiber, antioxidants, and bioactive compounds, along with improved texture and sensory appeal, but these bowls also had good biodegradability of 40.46% ± 1.69% over 15 d. Additionally, using processing byproducts like pomegranate seeds promotes a circular economy and holds promise for long-term environmental responsibility, making it a promising alternative to conventional throwaway plastic utensils, thus reducing waste. In the future, research on enhancing the moisture resistance, durability for hot and cold foods, and the application of coatings of natural edible films to edible bowls and flatware could be conducted to further enhance their utility and consumer acceptance for commercialization.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conducting the research, data collection, investigation, and preparation of the initial draft of the manuscript: Yadav P; assisted in experimental work, data compilation, and the literature review: Bains R; reviewed and refined the manuscript, gave critical inputs to improve clarity and quality: Biswas D; conceptualization, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, and editing: Chandel V; validation, visualization, supervision, and editing: Roy S. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the published article and further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

-

No funding received in this work.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yadav P, Bains R, Biswas D, Chandel V, Roy S. 2025. Development of edible multigrain bowls by processing castoff wild pomegranate seed powder. Food Materials Research 5: e022 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0025-0023

Development of edible multigrain bowls by processing castoff wild pomegranate seed powder

- Received: 10 October 2025

- Revised: 10 November 2025

- Accepted: 23 November 2025

- Published online: 29 December 2025

Abstract: Wild pomegranate seeds, commonly left as processing waste, were utilized for the preparation of multigrain edible bowls by converting them into powder and mixing the powder with wheat and barley flour and jaggery as a replacement to throwaway plastic bowls. Wild pomegranate seed powder was added in different ratios from 5% to 20% in multigrain edible bowls, which increased enhanced the total phenolic content from 1,397.64 ± 15.54 to 1,552.62 ± 21.67 µg gallic acid equivalent (GAE)/100 g dry weight and antioxidant activity from 38.22% ± 1.82% to 49.21% ± 2.36%, demonstrating possible functional health advantages. Multigrain bowls with 20% pomegranate seed powder exhibited the lowest levels of oil absorption (5.73% ± 0.13%) and water absorption (7.64% ± 0.43%). The moisture content ranged from 9.69% ± 0.51% for the control to 13.50% ± 0.46% for multigrain bowls made from 20% pomegranate seed powder. Decomposition also increased from 26.76% ± 1.03% for the control multigrain treatment to 40.46% ± 1.69% biodegradability for the 20% pomegranate seed treatment after 15 days, indicating a notable environmental benefit over traditional plastic flatware. The 15% pomegranate seed treatment was found to have the best textural qualities by texture profile analysis, with a hardness of 4.69 ± 0.28 Kgf and superior sensory traits with the highest overall acceptance scores of 7.73 out of 9 according to a sensory evaluation. Wild pomegranate seed powder-based multigrain edible bowls' functional, nutritional, and sensory aspects may make them a sustainable alternative to traditional throwaway plastic tableware.