-

The combination of unsym-dimethylhydrazine (UDMH) and nitrogen tetroxide (NTO) is a widely adopted hypergolic bipropellant in liquid rocket propulsion systems, including spacecraft (e.g., launch vehicles and satellite propulsion systems) and missile technology[1]. This mixture ignites spontaneously upon contact, requiring no ignition system. This unique combustion behavior makes the study of its fundamental combustion characteristics particularly critical. However, the high toxicity and corrosiveness of UDMH strongly hinder the related experimental investigations on its combustion characteristics. Although some kinetic models for hydrazine-based fuel/NTO systems have been developed and analyzed[2−6] on the basis of previous theoretical calculations, the accuracy of the rate constants of elementary reactions still requires further refinement. Under this background, high-performance theoretical calculations using a quantum chemical method provide a safer alternative for understanding the chemical structure and the corresponding elementary reactions, which is of critical importance for understanding combustion characteristics and developing kinetic model.

To date, theoretical studies on hydrazine-based fuel/NTO bipropellant systems have primarily focused on thermal decomposition and H-abstraction reactions. Sun et al.[7,8] conducted systematic theoretical investigations on methylhydrazine (MMH), examining both thermal decomposition and H-abstraction pathways. Their results demonstrated that H-abstraction from the terminal amine site, where it forms the trans-HNN(H)CH3 radical, represents the predominant reaction channel among various possible abstraction routes. Tang et al.[9] employed BMC-CCSD//B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) level of theory to calculate rate constants for H-abstraction reactions between UDMH and OH. Wang et al.[10] and Kanno et al.[11] independently investigated H-abstraction reactions involving the H atom, utilizing different theoretical approaches. Specifically, Wang et al.[10] applied canonical variational transition state theory with small-curvature tunnelling correction (CVT/SCT) at the MCG3MPWPW91//MPW1K/6-311G(d,p) level, whereas Kanno et al.[11] employed CBS-QB3//DSD-BLYP-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVP in combination with transition state theory (TST), respectively. These investigations consistently revealed that, similar to MMH, H-abstraction from the terminal amine site of UDMH is thermodynamically favored over abstraction from the methyl site.

Regarding the successive decomposition reactions of fuel radicals, Kanno et al.[12] conducted computational studies on the reactions of NO2 with three MMH-derived radicals (HNN(H)CH3, H2NNCH3, and H2NN(H)CH2), using quantum chemical calculations and steady-state unimolecular master equation (ME) analysis based on Rice-Ramsperger-Kassel-Marcus (RRKM) theory. Their work yielded temperature- and pressure-dependent, product-specific rate coefficients for these reactions. The results demonstrated that the reactivity of these radicals with NO2 depends strongly on both the heights of the roaming transition-state barriers between RNO2 and RONO and the energy barriers for dissociation pathways. More recently, Bai et al.[13] extended this investigation to examine not only the initial H-abstraction reactions but also the subsequent H-abstraction processes involving NO2 and the primary radical product (HNNCH3). Computational methods, including the CCSD(T)/CBS//M06-2X/6-311++G(d,p) single-reference approach and the MRCI(7e,6o)/CBS//M06-2X/6-311++G(d,p) multi-reference method, were adopted. Using the RRKM/ME approach, they obtained temperature- and pressure-dependent rate constants. These investigations revealed that these reactions play a crucial role in enhancing the overall combustion reactivity of the MMH/NO2 system. It can be concluded that the successive decomposition reactions of fuel radicals in hydrazine-based fuels are of critical importance. However, existing theoretical calculations have primarily focused on MMH-derived radicals, with comparatively little research attention devoted to UDMH-derived radicals, despite UDMH's superior propellant characteristics, including its higher energy density. Furthermore, current studies have largely neglected other crucial decomposition pathways of these fuel radicals, such as isomerization reactions and β-scission reactions, which represent important decomposition mechanisms.

Prior computational studies[14] have demonstrated that although H-abstraction reactions can generate two distinct fuel radicals, HNN(CH3)2 and H2NN(CH3)CH2, the former represents the fuel-specific N-involved radical and is more preferentially formed. Consequently, this work systematically examines the decomposition pathways of HNN(CH3)2, including isomerization processes, β-scission reactions, and H-abstraction reactions with NO2 and NO oxidizers. The study employs high-level quantum chemical methods to characterize the complete potential energy surfaces and obtain temperature-dependent rate constants for these elementary reactions. A comprehensive comparative analysis is subsequently conducted to elucidate the dominant reaction mechanisms and their relative importance across different temperature regimes, with particular emphasis on the similarities and differences relative to MMH.

-

In this paper, the structure optimizations and frequency calculations for UDMH and its products were performed using the M06-2X method[15] combined with the def2-TZVP[16] basis set. The zero-point energy correction factor is 0.971[17], and the frequency correction factor is 0.984[17]. The intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) approach was utilized to ensure the accuracy of the transition state structures and to derive the corresponding reactant and product geometries. The low-frequency torsional modes with wave numbers below 300 cm-1 were identified as potential hindered rotors. For each identified torsional mode, a relaxed potential energy surface (PES) scan was performed by varying the corresponding dihedral angle in steps of 10° over a 360° range. All other geometric parameters were optimized at the M06-2X/def2-TZVP level of theory. Detailed results of electronic structure calculations are provided in the Supplementary File 1.

For high-precision single-point energy (SPE) calculations of stable molecules and transition states, coupled cluster methods combined with the cc-pVDZ and cc-pVTZ basis sets were used to obtain the energies, which were then extrapolated to the complete basis set energies using Eq. (1)[18]. In the previous theoretical work on the unimolecular decomposition and H-abstraction reaction of UDMH[14], the convergence of this level of theory was evaluated using larger basis sets (cc-pVQZ and cc-pVTZ). It was found that the calculated SPEs for the UDMH decomposition reactions at the CCSD(T)/CBS(T+Q) level were within 1 kcal/mol of those obtained at the CCSD(T)/CBS(D+T) level, indicating the feasibility of the originally chosen theoretical approach. As reported by Lee & Taylor[19], T1 diagnostic values were defined as the Frobenius norm of the single substitution amplitudes vector of the closed-shell CCSD wave function divided by the square root of the number of correlated electrons to address size consistency, and the recommended upper limits of T1 diagnostic values are ≤ 0.025 for reactant species, ≤ 0.035 for product radicals, and ≤ 0.044 for transition states. As shown in Supplementary Table S1, all T1 diagnostic values in this study met these requirements, which demonstrates that the single-reference method can reliably describe the wave function. All quantum chemical calculations for geometry optimization, frequency analysis, and rotational potential scans were performed using the Gaussian 09 program[20].

$\begin{split} \mathit{E} _{ \mathrm{CCSD(T)/CBS(D+T)}} =\;& \mathit{E} _{ \mathrm{CCSD(T)/cc-pVTZ}} +( \mathit{E} _{ \mathrm{CCSD(T)/cc-pVTZ}} \;-\\& \mathit{E} _{ \mathrm{CCSD(T)/cc-pVDZ}} \mathrm{)\times 3}^{ \mathrm{4}} \mathrm{/(4}^{ \mathrm{4}} \mathrm{-3}^{ \mathrm{4}} \mathrm{)} \end{split}$ (1) For the calculation of rate constants of reactions with tight transition state, such as the isomerization and β-scission reactions of HNN(CH3)2 radical, rate constants were determined using transition state theory (TST) based on the PES results. For the barrierless reactions of HNN(CH3)2 with NO2 and NO, variational transition state theory (VTST) combined with the multi-reference method was applied. The CASPT2[21] method with the cc-pVDZ basis set was used to calculate the minimum energy paths (MEPs) for the corresponding N-N bond dissociation processes in their products. An active space of (6e,5o) was selected[22]. Based on the optimized geometries at CASPT2, the multi-reference configuration interaction method (MRCI) with the cc-pVDZ and cc-pVTZ basis sets is used to calculate higher-level single point energies, which are extrapolated to the CBS level using Eq. (2)[23]:

$\begin{split} \mathit{E} _{ \mathrm{MRCI(6e,5o)/CBS}} =\;& \mathit{E} _{ \mathrm{MRCI(6e,5o)/cc-pVTZ}} +( \mathit{E} _{ \mathrm{MRCI(6e,5o)/cc-pVTZ}} \;-\\& \mathit{E} _{ \mathrm{MRCI(6e,5o)/cc-pVDZ}} \mathrm{)\times 2}^{ \mathrm{3}} \mathrm{/(3}^{ {3}} {-2}^{{3}} {)}\end{split} $ (2) Zero-point energy (ZPE) correction is included in the final energy of the optimized structures. Notably, the formation of pre- and post-reaction van der Waals complexes (i.e., reactant and product complexes) can influence reaction barriers and quantum tunneling effects. Therefore, it is common practice to account for them in rate constant calculations. In this work, phase space theory[24] was utilized to estimate the microcanonical rate constants, where the potentials along the reaction coordinate were estimated by V = 10/R6, and the factor ten has the dimension of Bohr6[25]. The RRKM theory combined with the ME method[26] was employed to compute the pressure-dependent rate constants. The partition functions of reactants and transition states were approximated using the rigid rotor harmonic oscillator (RRHO) model. The low-frequency torsional mode treated as a one-dimensional (1D) hindered rotor[27]. During rate constant calculation, the partition function of the identified hindered rotor mode replaced the original harmonic oscillator partition function and was subsequently used in the transition state theory calculations to obtain more accurate thermodynamic data and rate constants. Tunneling effects were accounted for using the 1D asymmetric Eckart model[28] in the rate constant calculations. The collisional energy transfer model was treated using the empirical formula: <∆E>down = 200(T/300)0.85[13]. The Lennard-Jones parameters σ = 5.65 Å and ε = 258.55 cm−1 were used for all intermediates[13]. The bath gas Ar was used in the present study, and ε = 78.88 cm−1 and σ = 3.47 Å were employed[29]. In this work, the RRKM/ME simulations were performed using the MESS kinetic code[30]. The pressure-dependent and high-pressure-limit (HPL) rate constants were fitted to a modified Arrhenius Eq. (3),

$ \mathit{k} \mathrm{(} \mathit{T} \mathrm{)} \mathit{=AT} ^{ \mathit{n} } \mathrm{exp(-} \mathit{E} _{ \mathit{a} } \mathit{/RT} \mathrm{)} $ (3) where, A, n, and Ea correspond to the pre-exponential factor, the temperature exponent, and the activation energy of the reaction, respectively. In addition, two-parameter fitting was adopted for reactions exhibiting non-Arrhenius behavior. The Arrhenius parameters of the relevant reactions of HNN(CH3)2 calculated in this work are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. List of the Arrhenius parameters for the rate constants of isomerization and β-scission reactions of UDMH radicals, as well as the H-abstraction reactions of the HNN(CH3)2 radical and subsequent decomposition reactions at HPL or 100 atm conditions.

No. Reactions P (atm) A n Ea (cal/mol) 1 HNN(CH3)2 = H2NN(CH3)CH2 HPL 1.2258E−15 8.1005 37,245 2 HNN(CH3)2 = cis-HNNCH3 + CH3 HPL 1.3900E+12 0.78176 41,951 3 HNN(CH3)2 = trans-HNNCH3 + CH3 HPL 2.1770E+12 0.72387 36,806 4 H2NN(CH3)CH2 = H2NNCH2 + CH3 HPL 8.4385E+12 0.43102 29,575 5 H2NN(CH3)CH2 = CH2NCH3 + NH2 HPL 1.6031E+13 0.18499 14,279 6 HNN(CH3)2 + NO2 = NN(CH3)2 + cis-HONO 100 7.3949E+20 −2.7812 1,607.6 4.2465E+04 1.8100 −4,564.2 7 HNN(CH3)2 + NO2 = CH2NCH3 + ON(NH)(OH) 100 2.3499E+02 2.0956 22,579 8 HNN(CH3)2 + NO2 = NN(CH3)2 + trans-HONO 100 1.0116E+45 −9.5853 39,906 5.7045E+10 0.19569 20,318 9 HNN(CH3)2 + NO2 = CH2NCH3 + NN(OH)2 100 3.9191E+03 1.6501 21,623 10 HNN(CH3)2 + NO = NN(CH3)2 + HNO 100 1.7593E+03 2.2232 15,951 11 HNN(CH3)2 + NO = HNN(CH3)CH2 + HNO 100 5.1298E+03 2.1753 24,033 12 HNN(CH3)2 + NO = NN(CH3)2 + NOH 100 2.7881E+02 2.6552 41,967 13 HNN(CH3)2 + NO = HNN(CH3)CH2 + NOH 100 2.4904E−01 3.3194 46,582 14 NN(CH3)2 = HNN(CH3)CH2 HPL 3.7076E+10 0.99227 48,700 15 NN(CH3)2 = N2 + C2H6 HPL 6.2976E+10 1.5546 36,030 16 HNN(CH3)CH2 = HNNCH2 + CH3 HPL 3.5255E+12 0.29155 53,875 The influences of tunneling and hindered rotor treatments on the rate constants were comprehensively evaluated. As depicted in Supplementary Figs. S1–S4, the effect of tunneling on the calculated rate constants is minor at high temperatures, while the effect on R1 becomes significant at low temperatures. Moreover, the hindered rotor treatments also have little effect, except in the cases of R6 and R12. Additionally, the uncertainty analyses of the energy barrier and collisional parameter were performed on the calculated rate constants for the decomposition of UDMH radical. Supplementary Fig. S5 indicates that a variation of ± 1 kcal/mol in the energy barriers introduces only minor errors for reactions R1 to R4, particularly at high temperatures. In contrast, the error for R5 is relatively higher at 300 K. Generally, the uncertainties are more significant at lower temperatures than at higher ones. Regarding the collisional parameter, Supplementary Fig. S6 shows that the influence of σ on the rate constants is negligible. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. S7, additionally, a comparison of the rate constants with and without consideration of the vdW complexes revealed negligible effects for reactions R7, R8, R11, and R12, and differences for reactions R9 and R10 at low temperatures.

-

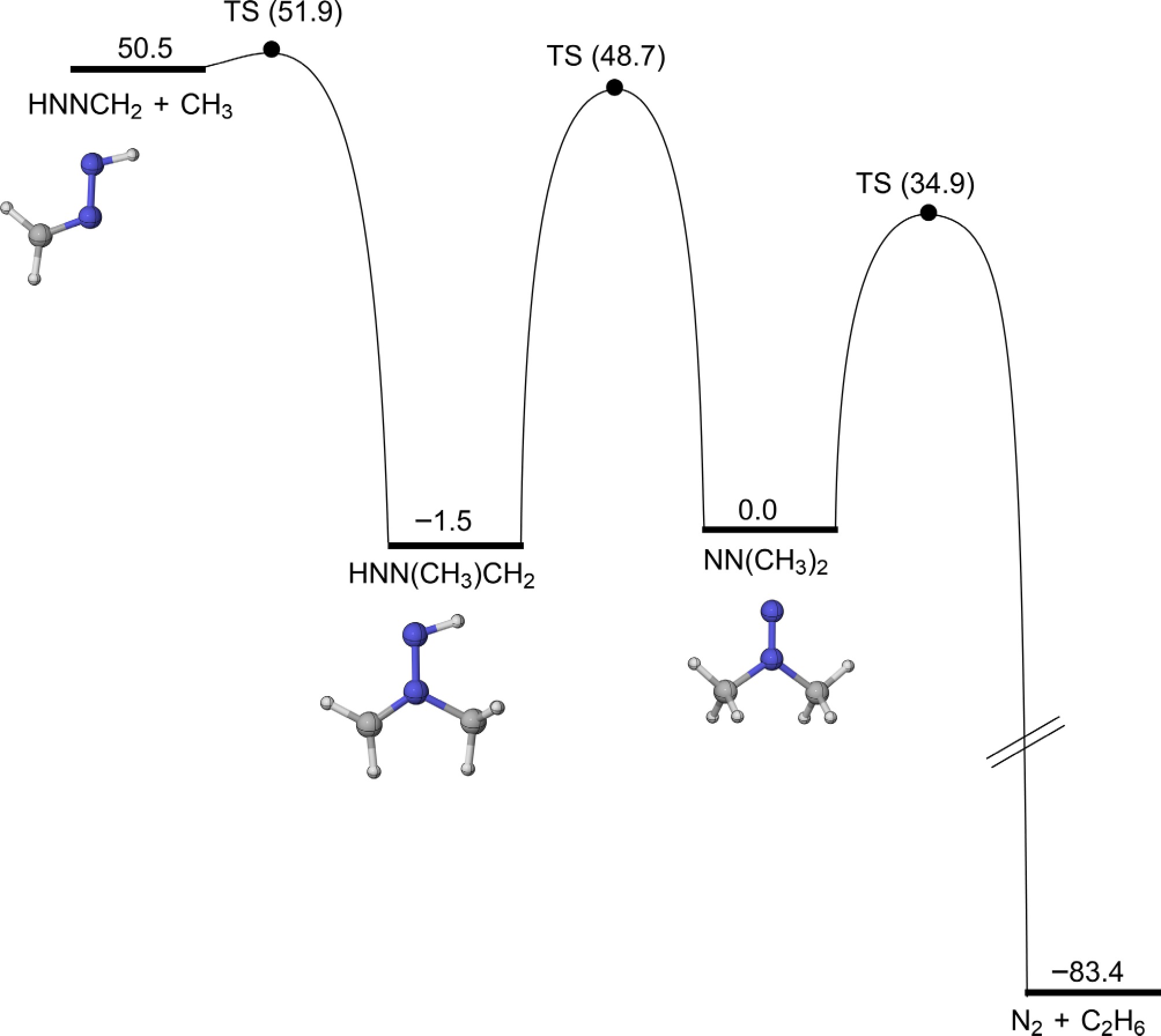

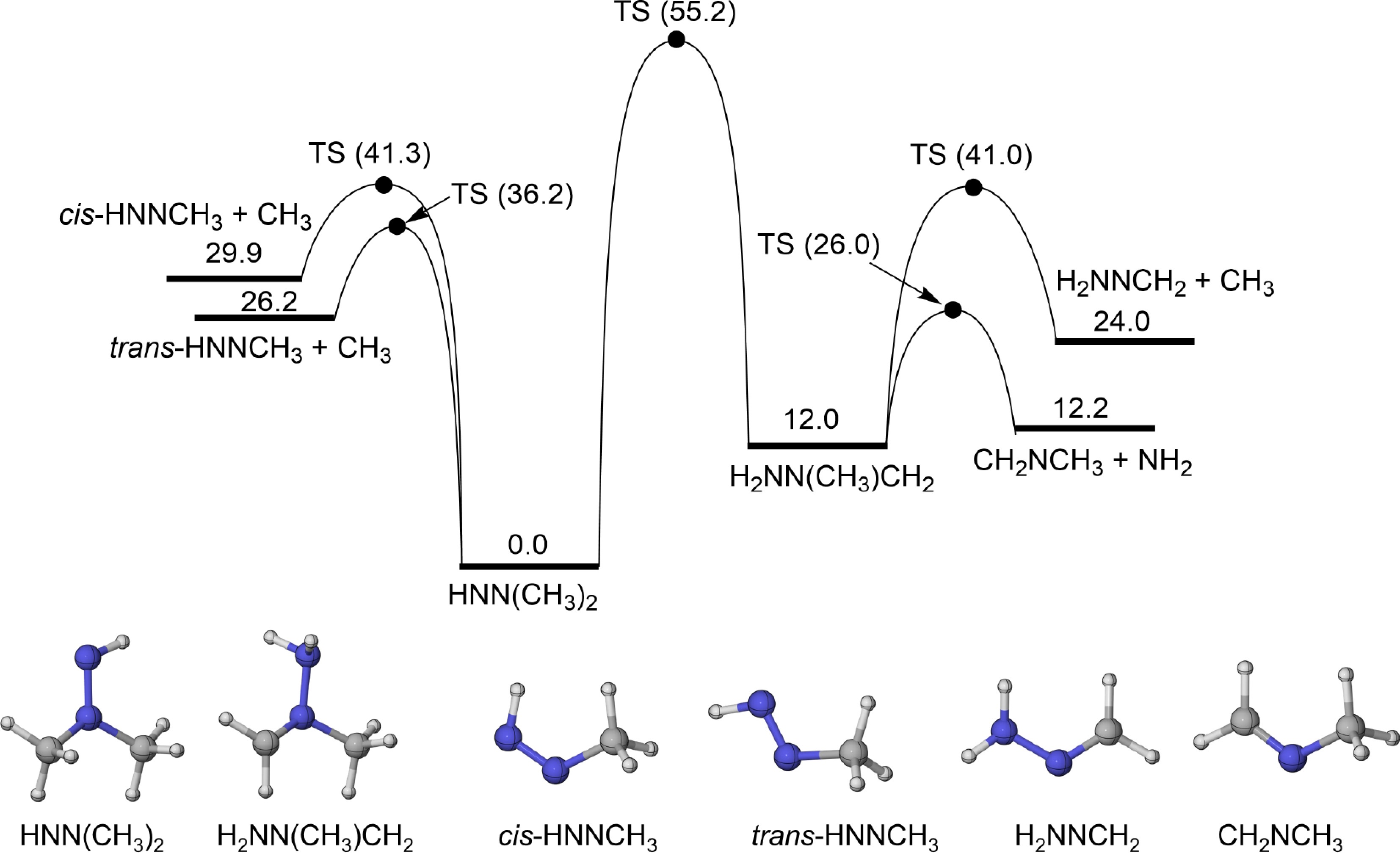

For the HNN(CH3)2 radical, the isomerization and β-scission reactions were investigated, with the PES results shown in Fig. 1. The H-migration isomerization reaction of HNN(CH3)2 (R1) has a relatively high energy barrier of 55.2 kcal/mol and the energy of the product H2NN(CH3)CH2 radical is 12.0 kcal/mol higher than the reactant. This radical can undergo β-scission reactions with energy barriers of 36.2 kcal/mol and 41.3 kcal/mol, producing cis-HNNCH3 (R2) and trans-HNNCH3 (R3), respectively. This indicates that the β-N-C bond energies in HNN(CH3)2 are not uniform. Two β-scission channels were identified for the formed H2NN(CH3)CH2: one corresponds to β-N-C bond dissociation, yielding H2NNCH2 and CH3 (R4), whereas the other involves β-N-N bond dissociation, producing CH2NCH3 and NH2 (R5). Their calculated energy barriers are 41.0 kcal/mol and 26.0 kcal/mol, respectively.

Figure 1.

PES for the isomerization and β-scission reactions of HNN(CH3)2 radical at CCSD(T)/CBS(D+T)//M06-2X/def2-TZVP level (unit: kcal/mol).

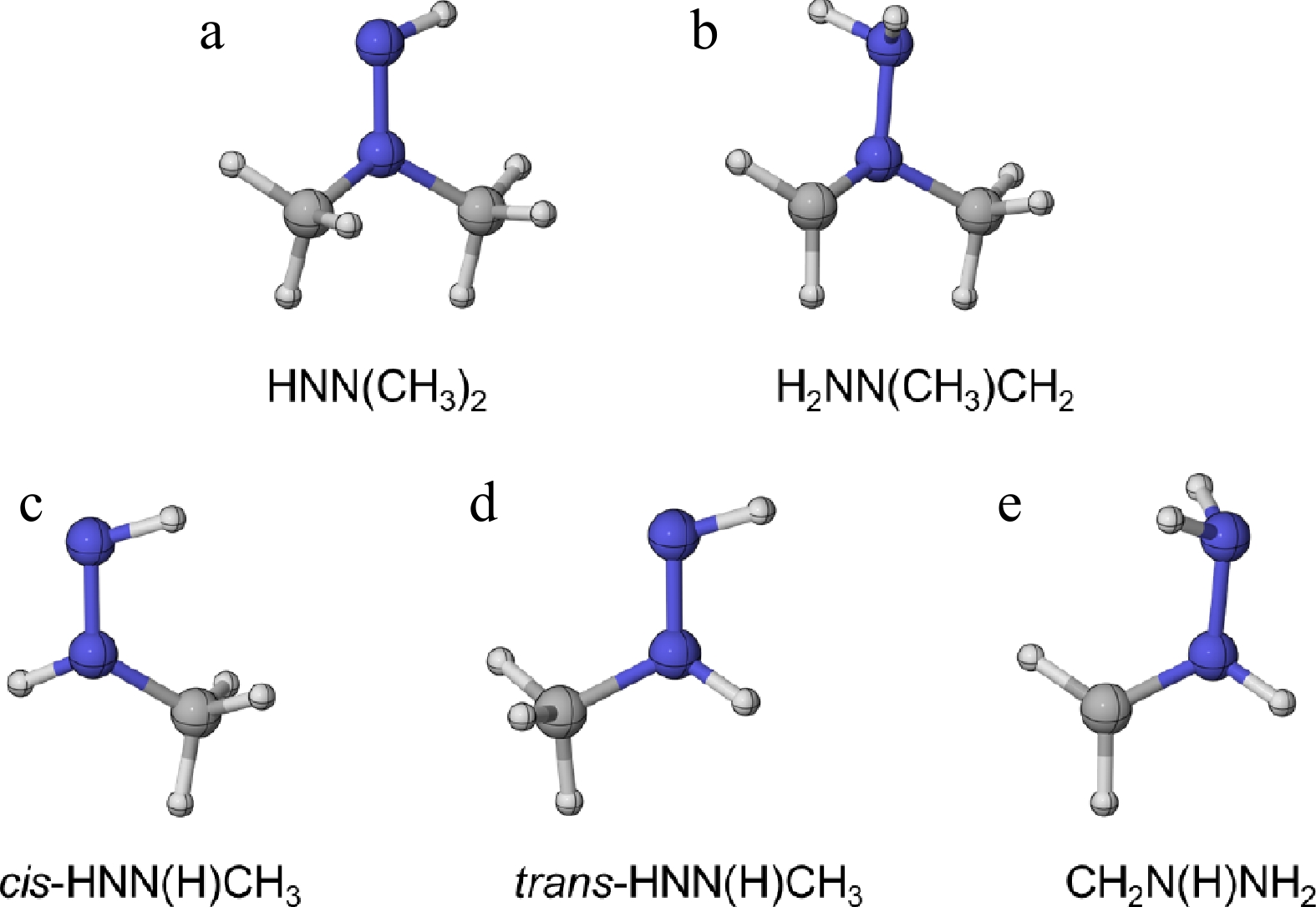

To illustrate the effects of increasing the number of CH3 groups (relative to MMH) on the decomposition trends of UDMH radicals, a comparison was carried out between the energy barriers of isomerization and β-scission reactions in UDMH radicals and those of MMH radicals with similar configurational characteristics (as shown in Fig. 2c−e). As shown in Table 2, the energy barrier for the isomerization reaction cis-HNN(H)CH3 = H2NN(H)CH2 is lower than that of R1 by 5.9 kcal/mol. For β-N-C scission reactions that form CH3 radical from the HNN(CH3)2 radical (R2 and R3), however, the calculated energy barriers are approximately 1 kcal/mol higher than those of trans-HNN(H)CH3 and cis-HNN(H)CH3. In addition, the energy barrier for the β-N-N scission reaction of the H2NN(CH3)CH2 radical (R5) is comparable to that of the H2NN(H)CH2 radical. These similarities suggest that the β-scission reactions of UDMH radicals exhibit chemical properties comparable to those of MMH radicals.

Figure 2.

The optimized molecular configurations of (a), (b) UDMH radicals at the M06-2X/def2-TZVP level of theory, and (c)–(e) MMH radicals at the CASPT2/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory[31].

Table 2. Comparison of the energy barrier for the isomerization and β-scission reactions of UDMH radicals with those of MMH radicals with similar configurational characteristics.

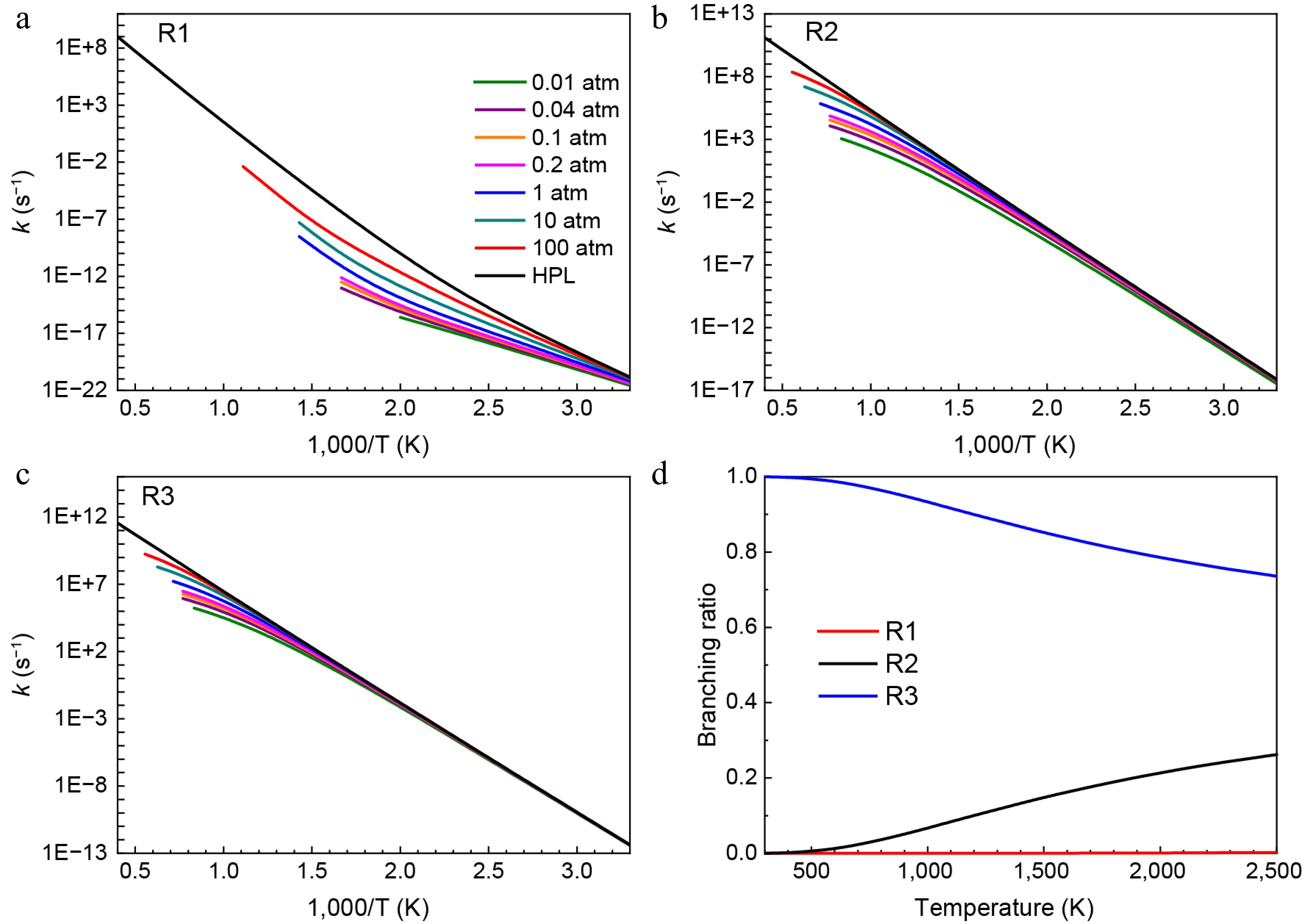

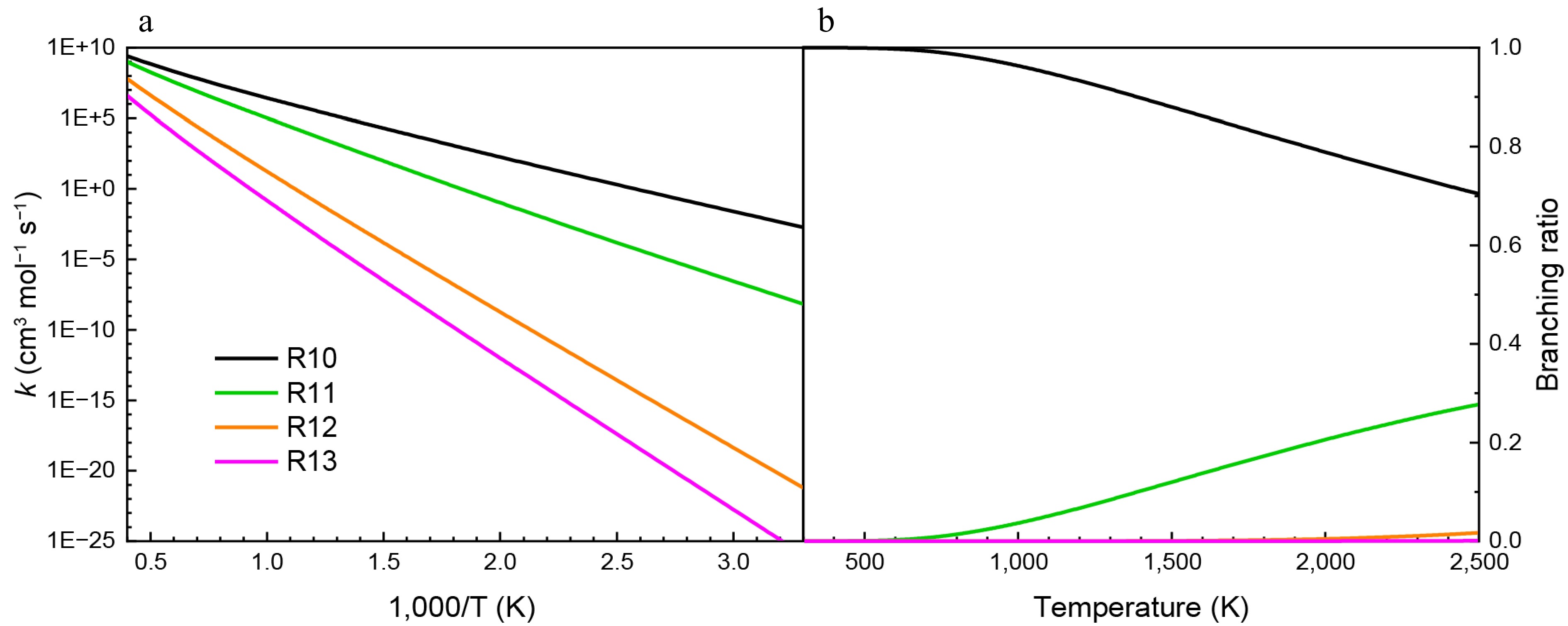

Reactions Energy barrier (kcal/mol) Ref. trans-HNN(H)CH3 = H2NN(H)CH2 49.3 (52.98) This work ([31]a) HNN(CH3)2 = H2NN(CH3)CH2 (R1) 55.2 This work trans-HNN(H)CH3 = cis-HNNH + CH3 42.2 (39.84) This work ([31]a) HNN(CH3)2 = cis-HNNCH3 + CH3 (R2) 41.3 This work cis-HNN(H)CH3 = trans-HNNH + CH3 37.2 (35.19) This work ([31]a) HNN(CH3)2 = trans-HNNCH3 + CH3 (R3) 36.2 This work H2NN(H)CH2 = CH2NH + NH2 13.5 (13.75) This work ([31]b) H2NN(CH3)CH2 = CH2NCH3 + NH2 (R5) 14.0 This work a Results were obtained at the theory level of QCISD(T)/cc-pV∞Z//B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p); b Results were obtained at the theory level of QCISD(T)/cc-pV∞Z//CASPT2/aug-cc-pVTZ. Figures 3 and 4 show the rate constants and branching ratios for the consumption pathways of HNN(CH3)2 and H2NN(CH3)CH2 radicals, respectively. From Fig. 3a–c, it is noticeable that as the pressures increase, the rate constants of the reactions R1, R2, and R3 all represent increasing trends. By comparison, the H-migration isomerization reaction of HNN(CH3)2 radical (R1) exhibits a much lower rate constants than the other two β-scission reactions (R2 and R3), due to its much higher energy barrier. Similarly, consistent with the trend in transition energy barriers, Fig. 3d depicts that despite the branching ratio of R3 decreasing with temperature, it still contributes up to 75% of HNN(CH3)2 decomposition at a temperature of 2,500 K. In addition, the contribution of another β-scission reaction (R2) increases with temperature and reaches 25%, implying that HNN(CH3)2 radical is predominantly decomposed through β-scission reactions. As shown in Fig. 4a–c, the rate constants of R1-R (the reverse reaction of R1), R4, and R5 also increase as the pressure rises. Furthermore, the H2NN(CH3)CH2 radical shows a higher rate constant and branching ratio (> 85%) for β-N-N scission reaction to produce CH2NCH3 and NH2 (R5). This is attributed to its relatively low energy barrier.

Figure 3.

Pressure-dependent rate constants for (a) R1, (b) R2, and (c) R3. (d) Branching ratios of all consumption reactions of HNN(CH3)2 radical at HPL.

Figure 4.

Pressure-dependent rate constants for (a) R1-R, (b) R4, and (c) R5. (d) Branching ratios of all consumption reactions of H2NN(CH3)CH2 radical at HPL.

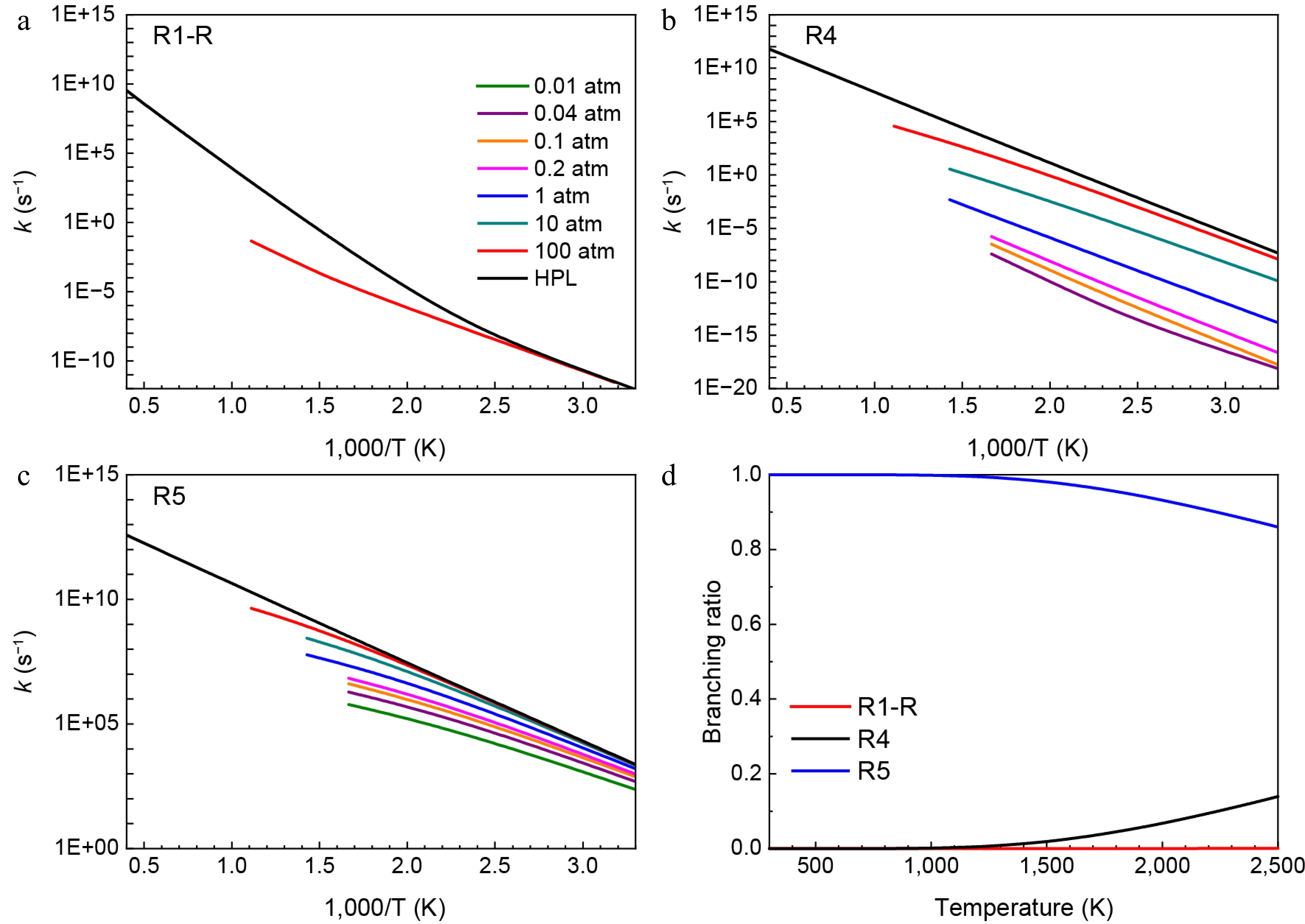

Sun et al.[31] comprehensively investigated the isomerization and β-scission reactions of MMH radicals (H2NNCH3, trans-HNN(H)CH3, cis-HNN(H)CH3, and H2NN(H)CH2). They found that trans-HNN(H)CH3 and its cis isomer cis-HNN(H)CH3 exhibited distinct behavior in their decomposition. In addition, the β-scission of the NH2 group in H2NN(H)CH2 to form methyleneimine is the principal channel for this radical's decomposition. Here, to gain further insight into the differences between the UDMH and MMH radicals, the rate constants for their β-scission reactions with similar configurational characteristics were compared. As shown in Fig. 5a, b, the β-N-C scission reactions forming CH3 radicals from HNN(CH3)2 and HNN(H)CH3 exhibit comparable rate constants. Specifically, the differences between the rate constants for R2 and the reaction trans-HNN(H)CH3 = cis-HNNH + CH3[31] are within a factor of two at temperatures above 800 K. Moreover, R3 and its counterpart reaction, cis-HNN(H)CH3 = trans-HNNH + CH3[31], show an even smaller difference in rate constants. This demonstrates that methyl substitution on the central nitrogen atom of the UDMH radical has a subtle influence on the kinetics of β-N-C scission reactions, suggesting that an analogous strategy may be applicable when developing kinetic models for UDMH combustion.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the rate constants for the β-scission reactions of (a), (b) HNN(CH3)2, and (c) H2NN(CH3)CH2 radicals with those of MMH radicals with similar configurational characteristics[31].

For β-N-N scission reactions forming NH2 radicals (Fig. 5c), the rate constants of R5 and H2NN(H)CH2 = CH2NH + NH2[31] differ by approximately a factor of two within the temperature range of 800–2,500 K. However, this discrepancy increases significantly as the temperature decreases, reaching a factor of 63 at 300 K − a behavior distinct from that of β-N-C scission. This difference may arise from variations in the selected theoretical levels or inherent molecular properties. In summary, under the high-temperature conditions relevant to combustion, the kinetic properties of β-scission reactions in the UDMH radical are relatively similar to those of the MMH radical.

Addition-dissociation reactions of HNN(CH3)2 radical

NO2 attacking

-

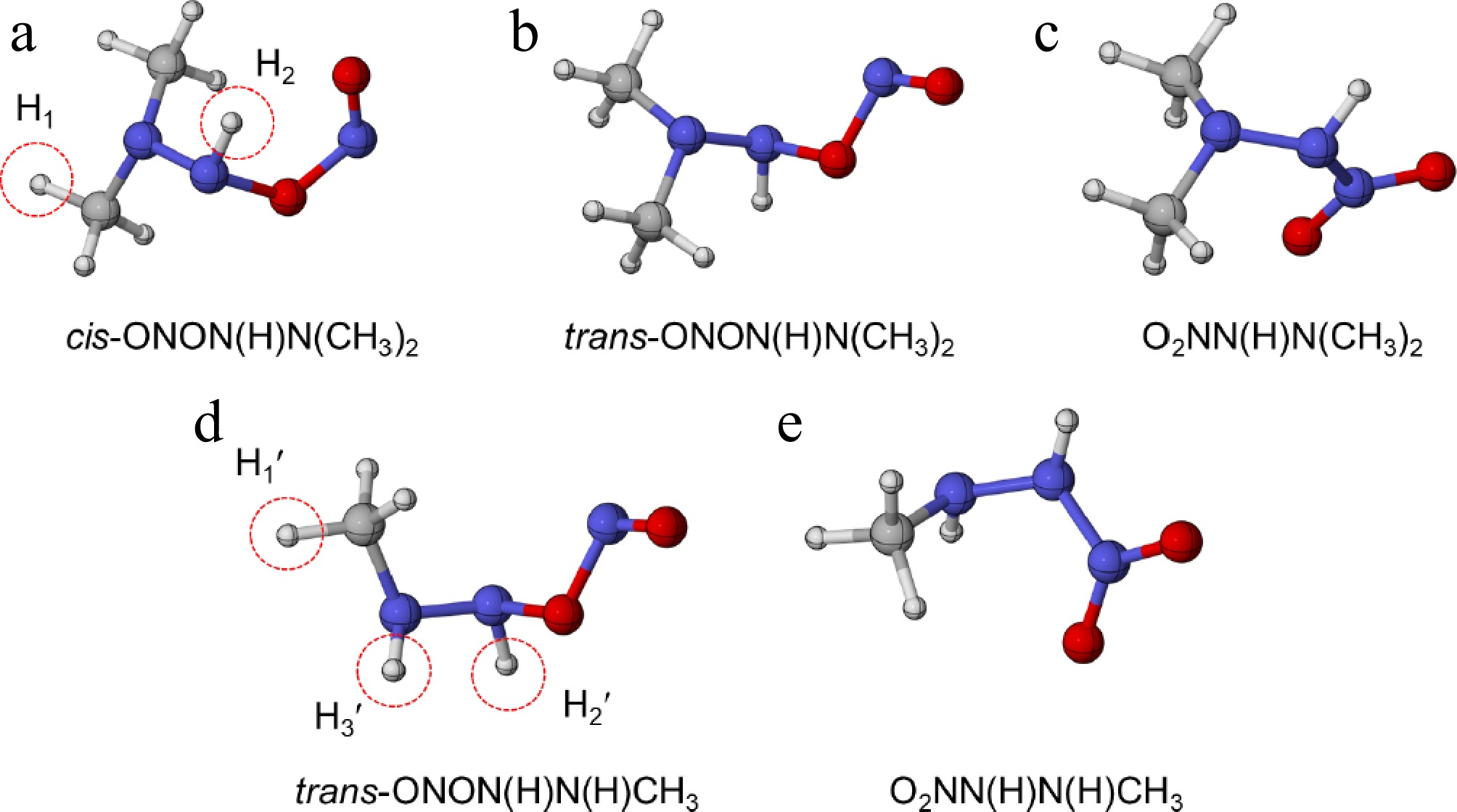

Considering the vital role of second H-abstraction reactions in the MMH/N2O4 combustion[13], the H-abstraction reactions of HNN(CH3)2 with NO2 and NO were investigated in this work. As depicted in Fig. 6a–c, the reaction of HNN(CH3)2 with NO2 yields three stable configurations, i.e., cis-ONON(H)N(CH3)2, trans-ONON(H)N(CH3)2, and O2NN(H)N(CH3)2. Table 3 shows that the formation of cis-ONON(H)N(CH3)2 and trans-ONON(H)N(CH3)2 releases 17.2 and 13.5 kcal/mol, respectively. In contrast, the analogous reaction NHN(H)CH3 + NO2 = trans-ONON(H)N(H)CH3 release 17.99 kcal/mol[12], which is higher than that of trans-ONON(H)N(CH3)2, despite their similar configurations. For N-N bond formation reactions, the energy released from HNN(CH3)2 + NO2 (31.7 kcal/mol) is slightly lower than that from NHN(H)CH3 + NO2 (33.84 kcal/mol)[12]. However, no stable transition state was found for the subsequent reactions of trans-ONON(H)N(CH3)2, differing from the reaction characteristics observed for NHN(H)CH3 + NO2[12,13]. Consequently, the following PES analysis and rate constant calculations focus exclusively on the subsequent reactions of cis-ONON(H)N(CH3)2 and O2NN(H)N(CH3)2.

Figure 6.

The optimized molecular configurations of (a)–(c) HNN(CH3)2 + NO2 at the M06-2X/def2-TZVP level of theory, and (d) NHN(H)CH3 + NO2 at the ωB97X-D/6-311++G(d,p) level of theory[12].

Table 3. Relative energies of HNN(CH3)2 + NO2 at the CCSD(T)/CBS(D+T)//M062X/def2-TZVP level of theory and NHNHCH3 + NO2 at the RHF-UCCSD(T)-F12//ωB97X-D/6-311++G(d,p) level of theory[12].

In the HNN(H)CH3 radical, there are three types of hydrogen atoms: those at the primary carbon sites (H1′), and those bonded to nitrogen (H2′ and H3′). In contrast, the HNN(CH3)2 radical lacks H3′ due to substitution of the H atom by a CH3 group, retaining only H1′ and H2′. Bai et al.[13] and Kanno et al.[12] found that reactions of HNN(H)CH3 with NO2 primarily produce HNNCH3 via abstraction of the H atom at H3′. However, the formation reaction pathways of the related NN(H)CH3 radical remain unexplored. In HNN(CH3)2, this reaction behavior is altered due to the absence of H3′.

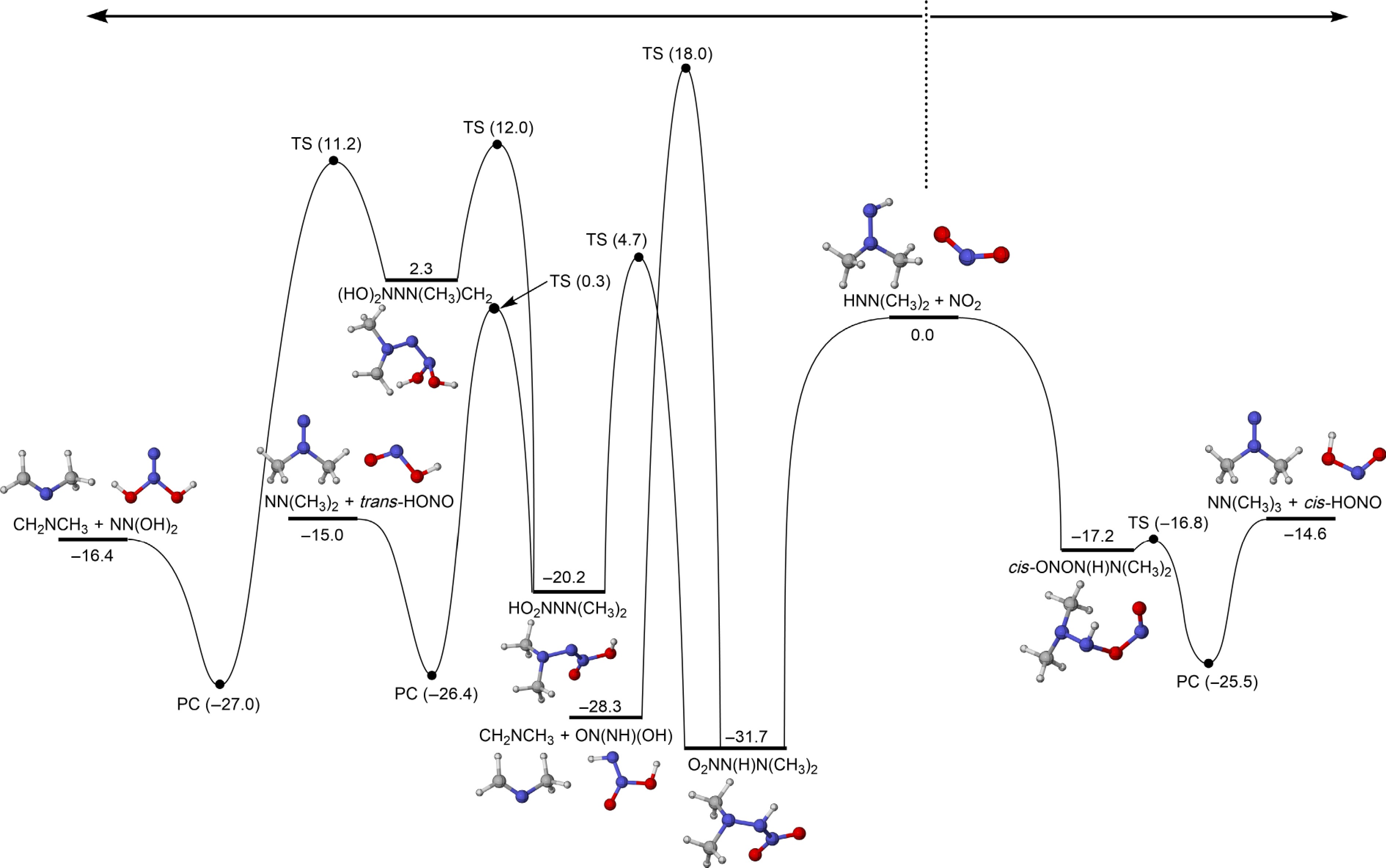

As depicted in Fig. 7, cis-ONON(H)N(CH3)2 undergoes a reaction with a low energy barrier of 0.4 kcal/mol, leading to the formation of a product complex (PC) via the abstraction of the H2′ atom. This product complex ultimately dissociates to generate NN(CH3)2 and cis-HONO (R6). In contrast, the decomposition of O2NN(H)N(CH3)2 proceeds via more complex reaction channels. The first pathway requires a relatively high energy barrier of 49.7 kcal/mol to pass through a transition state involving intramolecular H-immigration from the primary carbon site to the O atom of the NO2 molecule, subsequently generating CH2NCH3 and ON(NH)(OH) (R7). In addition, HO2NNN(CH3)2 can be formed from O2NN(H)N(CH3)2 via a relatively low energy barrier of 36.4 kcal/mol. Subsequently, this product decomposes into NN(CH3)2 and trans-HONO via a transition state with an energy barrier of 20.5 kcal/mol. Additionally, HO2NNN(CH3)2 undergoes a multi-well reaction pathway, ultimately leading to the formation of CH2NCH3 and NN(OH)2.

Figure 7.

PESs for the addition-dissociation reactions of HNN(CH3)2 with NO2 at CCSD(T)/CBS(D+T)//M06-2X/def2-TZVP level of theory (unit: kcal/mol).

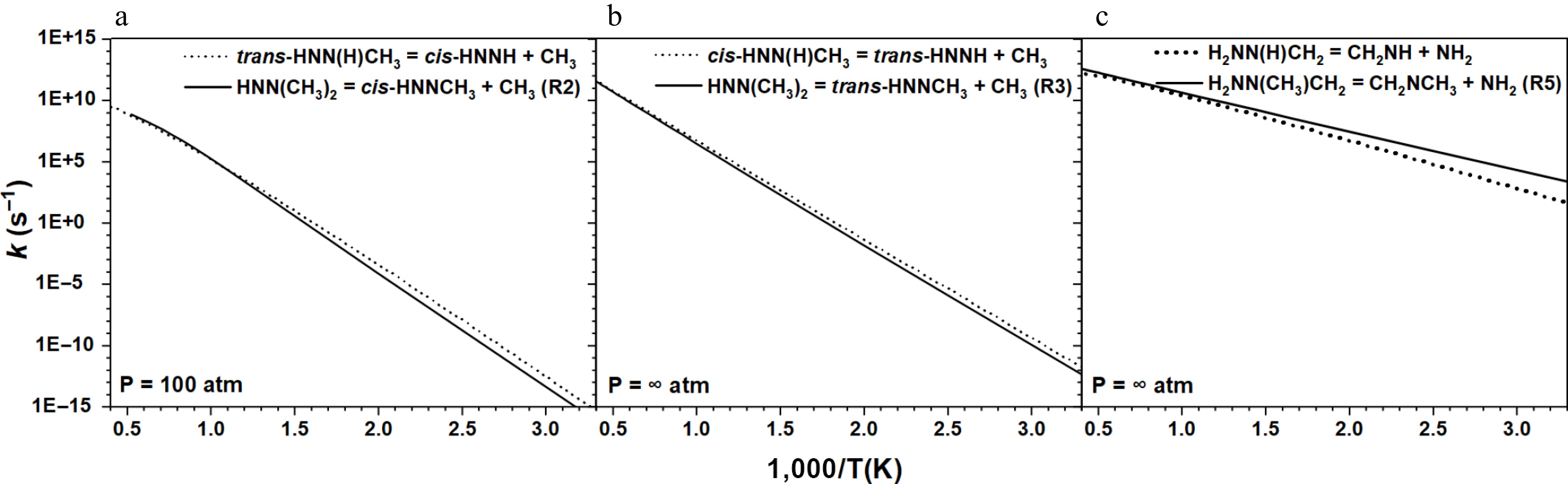

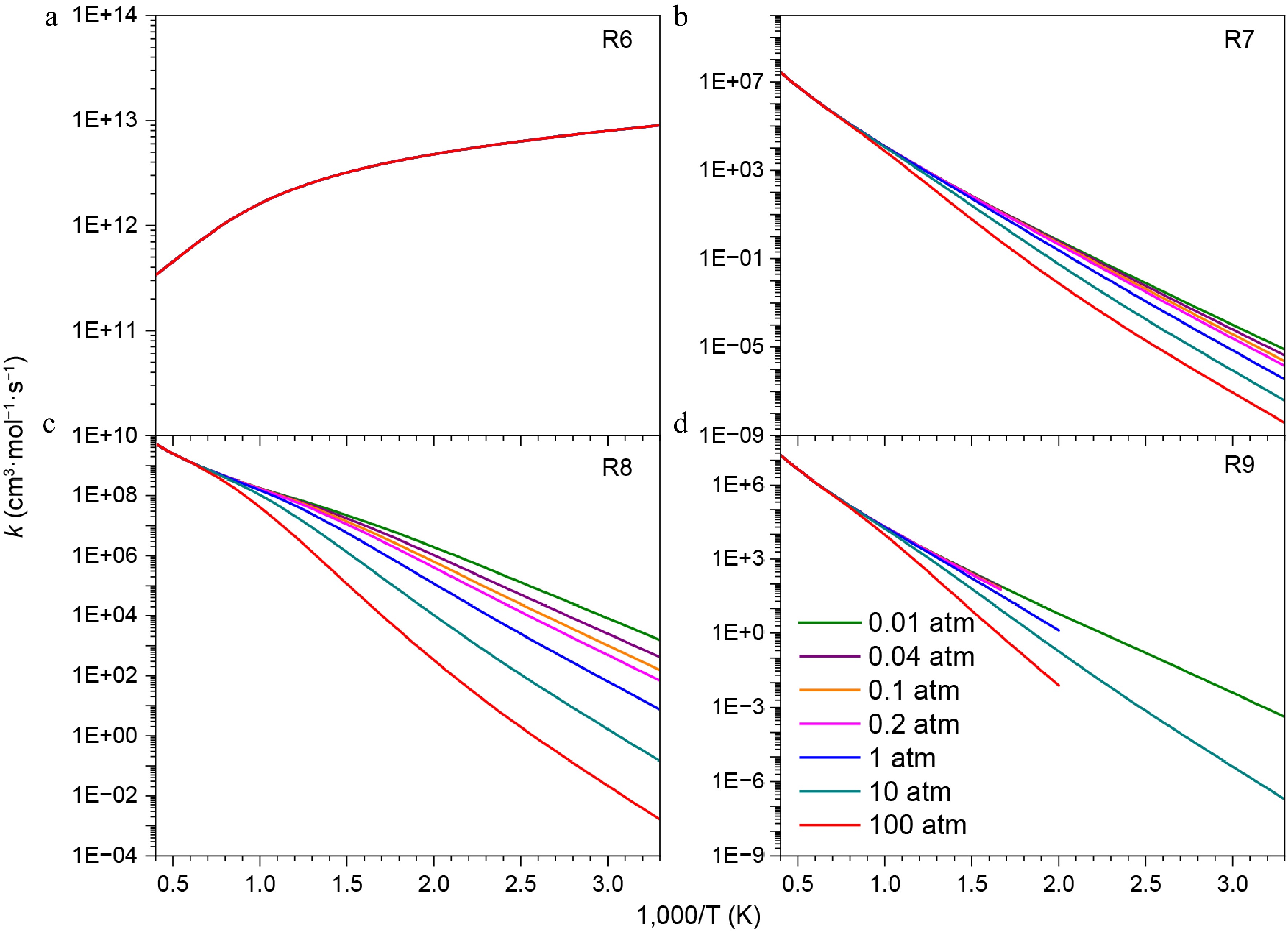

Figure 8 shows the rate constants of addition-dissociation reactions of the HNN(CH3)2 radical with NO2 at different pressure conditions. It is evident that the rate constants of reactions R6–R9 decrease with increasing pressure. Particularly, when the temperature is low (300 K), the rate constants of R8 at 0.01 atm and 100 atm differ by as much as six orders of magnitude. In addition, the rate constant of R6 exceeds 1 × 1011 cm3 mol−1 s−1, which is significantly higher than those of the other reactions due to a negative energy barrier. Based on the PES and rate constants, it can be inferred that NN(CH3)2 is favorably formed in the addition-dissociation reaction of the HNN(CH3)2 radical with NO2. Vaghjiani et al.[32] calculated the potential energy surface of the N2H3 + NO2 system, which is more complex compared to the reaction involving HNN(CH3)2 and NO2. For the N2H3 + NO2 system, at low temperatures, the channel leading to the formation of trans-N2H2 and trans-HONO is dominant. In contrast, the channel which produces NN(CH3)2 + cis-HONO has the most important contribution within the entire temperature range investigated in this work.

Figure 8.

Pressure-dependent rate constants for the addition-dissociation reactions of HNN(CH3)2 radical with NO2.

NO attacking

-

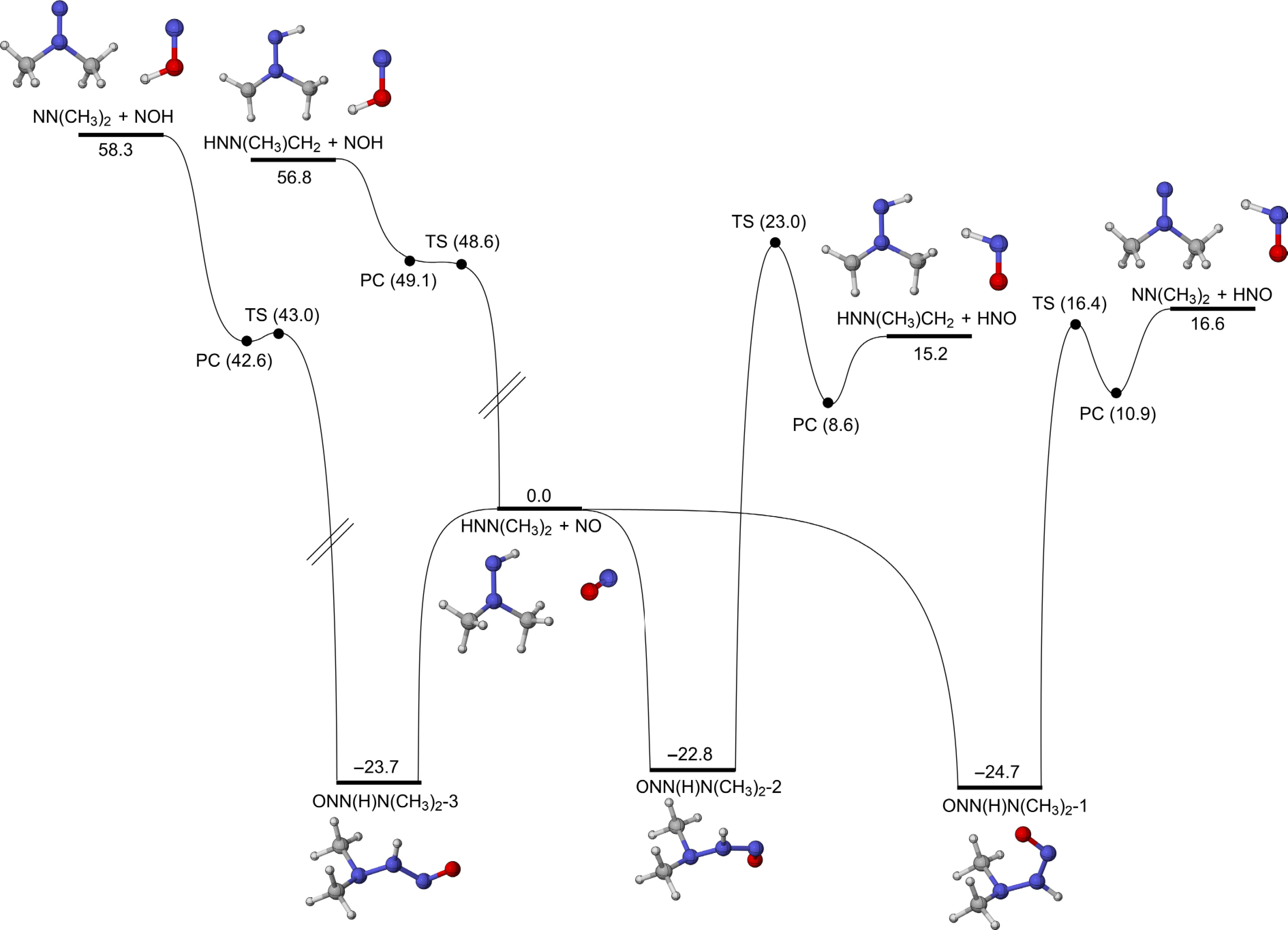

Figure 9 presents the PESs for the addition-dissociation reactions of the HNN(CH3)2 radical with the NO molecule. Four reaction pathways are identified based on the resulting products (HNO and NOH). Three intermediates, i.e., ONN(H)N(CH3)2-1, ONN(H)N(CH3)2-2, and ONN(H)N(CH3)2-3, are formed when HNN(CH3)2 reacts with NO, releasing 24.7, 22.8, and 23.7 kcal/mol of energy, respectively. For the formation of HNO, there are two main reaction channels. In the first pathway, ONN(H)N(CH3)2-1 overcomes an energy barrier of 41.1 kcal/mol, then the formed product complex decomposes into NN(CH3)2 and HNO (R10). The second pathway requires a relatively higher energy barrier of 45.8 kcal/mol and leads to the transformation of ONN(H)N(CH3)2-1 into HNN(CH3)CH2 and HNO (R11). For NOH formation, ONN(H)N(CH3)2-3 proceeds through a three-membered transition state with an energy barrier of 66.7 kcal/mol to form NN(CH3)2 and NOH (R12). The entire process requires a total energy input of 82.0 kcal/mol, which is higher than that of the other three reactions. When the O atom of NO attacks the H atom at the primary carbon (R14) directly, the energy barrier of the H-abstraction reaction is 48.6 kcal/mol, and the overall energy required to form HNN(CH3)CH2 and NOH (R13) is 56.8 kcal/mol.

Figure 9.

PESs for the addition-dissociation reactions of HNN(CH3)2 with NO at CCSD(T)/CBS(D+T)//M06-2X/def2-TZVP level of theory (unit: kcal/mol).

Figure 10 shows the rate constants for the addition-dissociation reactions of HNN(CH3)2 with the NO molecule based on the PES results. It is evident that reactions R12 and R13 exhibit lower rate constants due to their higher energy barriers. R10 has the lowest barrier among the four reactions, demonstrating the highest reaction rate. As the reaction temperature increases, the differences in rate constants among the four reactions gradually decrease. As depicted in Fig. 10b, the branching ratio of R10 decreases with increasing temperature and reaches 70% at 2,500 K. Another HNO formation reaction (R11) plays a secondary role in the addition-dissociation reactions of HNN(CH3)2 with NO. In addition, the NOH formation reactions make smaller contributions. According to the calculated results for the addition-dissociation reactions of HNN(CH3)2 with NO2 and NO, it can be concluded that NN(CH3)2 is readily formed.

Figure 10.

(a) Rate constants, and (b) branching ratios for the addition-dissociation reactions of HNN(CH3)2 with NO at HPL.

Subsequent decomposition reactions of NN(CH3)2

-

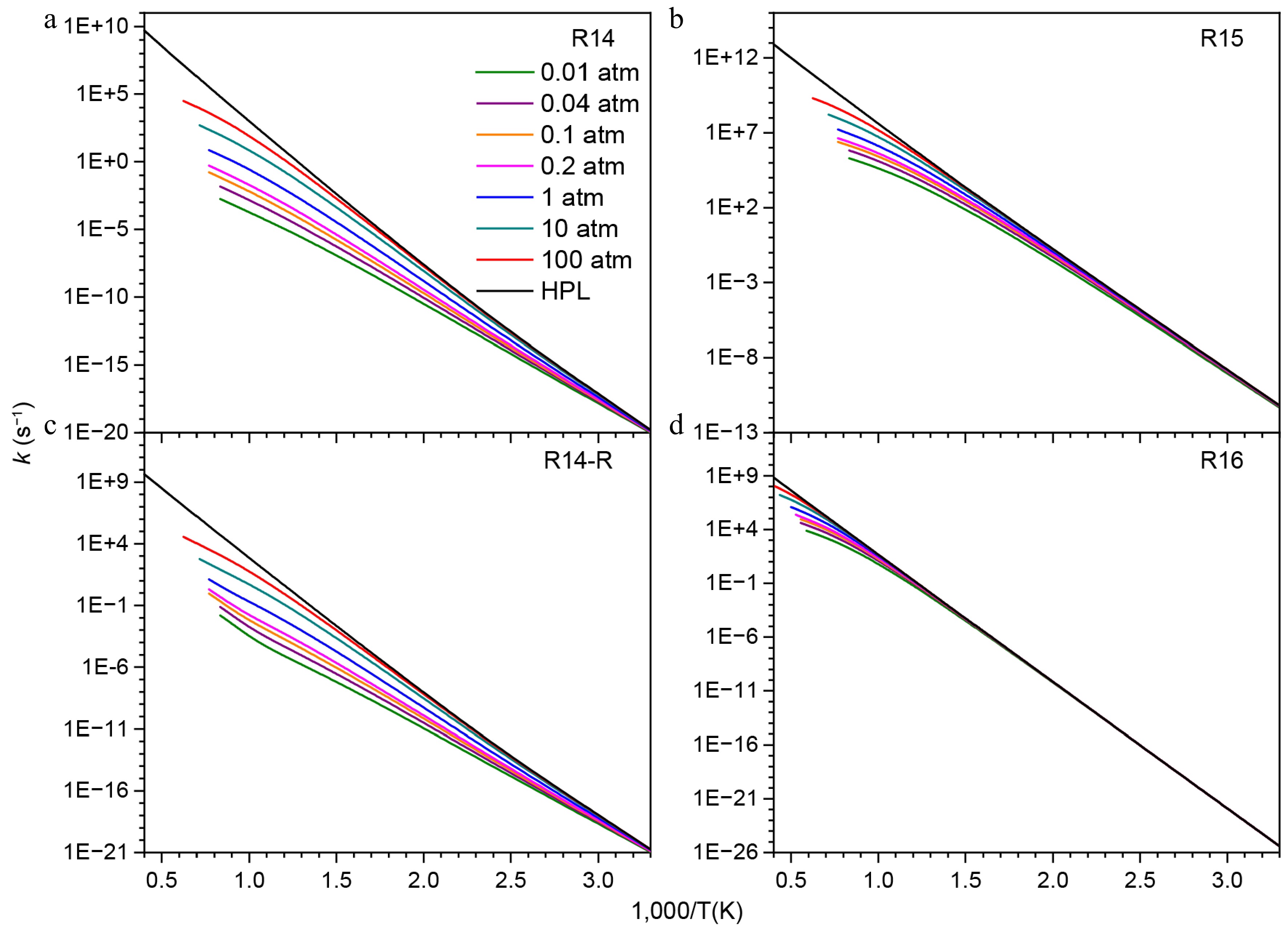

Considering that NN(CH3)2 is easy to form, its subsequent consumption reactions were studied. As shown in Fig. 11, the H-migration isomerization reaction (R14) of NN(CH3)2 to generate the HNN(CH3)CH2 radical has an energy barrier of 48.7 kcal/mol. The calculations also indicate that NN(CH3)2 can dissociate to produce N2 and C2H6 (R15), with an energy barrier of 34.9 kcal/mol and releasing 83.4 kcal/mol of energy. This barrier is 13.8 kcal/mol lower than that of the H-migration isomerization reaction, making R15 the more favorable pathway. In addition, the β-N-C scission of the HNN(CH3)CH2 radical to form HNNCH2 and CH3 (R16) has a higher energy barrier of 53.4 kcal/mol. Rate constant calculations under varying pressures, as presented in Fig. 12, further demonstrate that R15 has a higher rate constant, as a result of its relatively lower energy barrier. Furthermore, the rate constants of R14 and its reverse reaction (R14-R) exhibit strong pressure dependence, particularly at high temperatures, whereas the pressure effects on R15 and R16 are comparatively weaker, especially at lower temperatures.

-

In this work, the decomposition reactions of HNN(CH3)2 radical, including the isomerization, β-scission, and H-abstraction reactions, were theoretically investigated at the CCSD(T)/CBS(D+T)//M06-2X/def2-TZVP level of theory. Pressure-dependent rate constants of isomerization and β-scission reactions of HNN(CH3)2 were determined by solving the RRKM/ME equations. Additionally, the subsequent decomposition reactions of NN(CH3)2 were also studied. Comparative analyses with MMH radicals were conducted to elucidate the effects of CH3 group substitution on the kinetic characteristics of UDMH radical decomposition. The key findings can be summarized as follows:

(1) For the isomerization and β-scission reactions of UDMH radicals, HNN(CH3)2 undergoes β-scission (forming HNNCH3) more readily than H-migration isomerization. For the H2NN(CH3)CH2 radical, the β-N-N scission reaction that produces CH2NCH3 and NH2 is characterized by a relatively lower energy barrier and a higher rate constant.

(2) For the H-abstraction reactions of HNN(CH3)2 by NO2, the pathway forming NN(CH3)2 and cis-HONO via the decomposition of cis-ONON(H)N(CH3)2 has the lowest energy barrier and the highest rate constants. Similarly, H-abstraction by NO also readily yields NN(CH3)2. Subsequently, NN(CH3)2 dissociates into N2 and C2H6 through a pathway with a relatively low energy barrier.

(3) Based on the comparison, the kinetic properties of β-scission reactions in UDMH radicals are similar to those in MMH radicals. However, the H-abstraction of HNN(CH3)2 by NO2 differs significantly from that of the MMH radical (HNN(H)CH3). HNN(CH3)2 primarily undergoes H-abstraction at the terminal nitrogen site to form NN(CH3)2, whereas HNN(H)CH3 favors H-abstraction from the central nitrogen atom. The obtained fundamental kinetic parameters provide critical inputs for refining detailed chemical kinetic models of hydrazine-based propellant combustion.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Li Y; investigation: Zhang Y, Fang Q, Fang J; formal analysis: Zhang Y, Fang Q; data analysis: Li W; draft manuscript preparation: Li W, Zhang Y, Fang Q; manuscript revision: Li W, Fang Q, Li Y. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The theoretically calculated and analytical data obtained in this work are included in this published article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Wei Li, Yi Zhang

- Supplementary File 1 Geometries and frequencies (without correction) of reactants and transition states (TSs).

- Supplementary Table S1 T1 diagnostic values of key species at the CCSD(T)/cc-pVTZ level.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Effects of tunnelling treatment and hindered rotor treatment treatment on the rate constants of R1-R5 and R1-R.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Effects of tunnelling treatment and hindered rotor treatment on the rate constants of R6-R9.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Effects of tunnelling treatment and hindered rotor treatment on the rate constants of R10-R13.

- Supplementary Fig. S4 Effects of tunnelling treatment and hindered rotor treatment on the rate constants of R14-R16 and R14-R.

- Supplementary Fig. S5 The influence of energy barrier changing on the rate constants of R1-R5 at 300-2500 K and 100 atm. The energy barriers were changed by 1 kcal/mol for the uncertainty analysis.

- Supplementary Fig. S6 The influence of collisional parameters changing on the rate constants of R1-R5 at 300-2500 K and 100 atm. σ was changed by 10% for the uncertainty analysis.

- Supplementary Fig. S7 The influence of vdW complex treatment on the rate constants of R7-R12 at 300-2500 K and 100 atm.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Li W, Zhang Y, Fang Q, Fang J, Li Y. 2026. Ab initio kinetic study of decomposition reactions of the unsym-dimethylhydrazine radical HNN(CH3)2. Progress in Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism 51: e001 doi: 10.48130/prkm-0025-0028

Ab initio kinetic study of decomposition reactions of the unsym-dimethylhydrazine radical HNN(CH3)2

- Received: 08 August 2025

- Revised: 04 November 2025

- Accepted: 12 November 2025

- Published online: 09 January 2026

Abstract: Unsym-dimethylhydrazine (UDMH) is an important nitrogen-containing liquid propellant fuel commonly combined with nitrogen tetroxide (NTO) in hypergolic systems. In this work, theoretical calculations were performed on the decomposition reactions of critical UDMH radical, HNN(CH3)2 to get insight into its combustion chemical kinetics. Specifically, reactions of its isomerization, β-scission, and H-abstraction reactions attacked by NO2 and NO, as well as the subsequent decomposition reactions of formed NN(CH3)2 were investigated. Potential energy surfaces (PESs) for these reactions were obtained by employing the CCSD(T)/CBS(D+T)//M06-2X/def2-TZVP method. The RRKM/Master Equation approach was used to calculate the temperature- and pressure-dependent rate constants. Comparisons with monomethylhydrazine (MMH) radicals were made to elucidate the effect of CH3-group substitution on the kinetic characteristics of UDMH-radical decomposition. For isomerization and β-scission reactions of HNN(CH3)2, it undergoes β-N-C scission reaction more readily than H-migration isomerization to H2NN(CH3)CH2. Additionally, the rate constants for β-scission reactions of UDMH radicals are close to those of MMH radicals. For the H-abstraction reactions of HNN(CH3)2 by NO2, the reaction forming NN(CH3)2 and cis-HONO from the decomposition of cis-ONON(H)N(CH3)2 has the highest rate constants, which differ significantly from the H-abstraction of MMH radical (HNN[H]CH3). HNN(CH3)2 primarily undergoes H-abstraction at the terminal nitrogen site, forming NN(CH3)2, whereas HNN(H)CH3 prefers H-abstraction from the central nitrogen atom. The H-abstraction reaction of HNN(CH3)2 by NO also easily produces NN(CH3)2. Subsequently, NN(CH3)2 dissociates via a low-barrier pathway to produce N2 and C2H6. The calculated rate constants provide important parameters for the kinetic modeling development of UDMH/NTO combustion.