-

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is a nonprotein amino acid widely distributed across plants and animals[1,2]. In plants, GABA is integral to stress adaptation and metabolic control[3]. The GABA shunt—comprising glutamate decarboxylase (GAD), GABA transaminase (GABA-T), and succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase (SSADH)—serves as a bypass that channels glutamate to succinate, thereby coupling primary nitrogen metabolism with the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle[2,4]. Activation of this pathway contributes to redox homeostasis, osmotic balance, and energy production, particularly under abiotic stress and during senescence[5].

The application of exogenous GABA has been increasingly recognized as an effective strategy for alleviating postharvest deterioration in fruit and vegetables[4]. GABA treatment has been shown to delay chlorophyll degradation, inhibit lipid peroxidation, enhance antioxidant activity, and preserve the nutritional quality of various horticultural crops[6−8]. Beyond its role in maintaining visual and nutritional traits, GABA also exerts regulatory effects at the metabolic and transcriptional levels[9,10]. It promotes the buildup of amino acids (e.g., glutamate and proline) and phenolics, and boosts the activities of the antioxidant enzymes catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD). These changes collectively contribute to a more robust antioxidant defense system and effectively mitigate senescence-associated oxidative damage[11]. In addition, GABA is involved in the modulation of ethylene biosynthesis and hormone signaling pathways, further supporting its role in delaying postharvest senescence in crops such as apple[12]. However, despite increasing evidence from fruits, its regulatory functions in Brassica vegetables remain largely unexplored. Beyond its physiological functions, GABA is considered a safe and environmentally friendly compound. It is widely used as a food additive and functional ingredient in beverages, dietary supplements, and pharmaceuticals[13].

Baby mustard (Brassica juncea var. gemmifera) is a unique vegetable native to Southwest China which is rich in ascorbic acid, phenolics, and glucosinolates[14]. These bioactive compounds not only contribute to its nutritional value but also offer potential health benefits, such as antioxidant and anti-carcinogenic activities[15−17]. In Southwest China, the cultivated area of baby mustard exceeds 60,000 ha annually, with yields reaching 35–60 tons per hectare in normal years, which is higher than that of many traditional local vegetables[18]. As a specialty vegetable, it has relatively limited exports but is gaining increasing domestic popularity. Consequently, baby mustard provides considerable economic returns for growers and retailers, underscoring its commercial and nutritional importance. Because of the large size of baby mustard, the lateral buds are often separated for retail display and consumers' convenience. However, such segmentation causes mechanical damage, disrupting the tissue structure and compromising cellular integrity. This physical injury facilitates the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby accelerating quality loss and shortening shelf life[19]. Moreover, the lateral buds are prone to yellowing, dehydration, and shrinkage during postharvest storage, accompanied by significant declines in carotenoids, glucosinolates, and other nutrients within 1–2 days at 20 °C[20−23]. Several postharvest approaches have been applied to maintain the quality of baby mustard. Physical methods include low-temperature storage[20] and light exposure[14], while chemical treatments such as melatonin[21], sucrose[22], and calcium chloride[23] have also been reported to delay senescence and preserve nutritional quality. Therefore, novel, safe, and efficient strategies are needed to further extend its shelf life and improve postharvest quality.

Metabolomics has emerged as a powerful tool for elucidating the complex biochemical mechanisms underlying plants' physiological responses[24]. When integrated with transcriptomic analysis, it enables the characterization of transcriptional regulation and the elucidation of compound- and gene-level responses to exogenous treatments such as GABA. Although omics approaches have been widely applied in model species such as tomato[25], no omics-based studies have been conducted on baby mustard to date.

In this study, we investigated the effects of exogenous GABA treatment on postharvest senescence in the lateral buds of baby mustard. By integrating physiological measurements with quasi-targeted metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses, we aimed to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms by which GABA preserves visual and nutritional quality, modulates primary and secondary metabolism, and suppresses senescence-associated transcriptional networks during storage. This work not only provides novel insights into the role of GABA as a postharvest treatment for Brassica vegetables, but also represents the first omics-based exploration of senescence regulation in baby mustard.

-

Baby mustard (Brassica juncea var. gemmifera cv. Chuanbao-11) was harvested from a local farm in Chengdu City, China, and immediately transported to the laboratory. In total, 48 lateral buds were randomly divided into two treatment groups, each with four replicates (six lateral buds per replicate). The lateral buds were immersed in either distilled water (control) or a 5 mM GABA solution, determined in preliminary experiments to be optimal, for 10 min. Each replicate was subsequently stored at 20 °C under 75% relative humidity. Samples were collected at 0 days (control, C0), after 4 days of storage in the water-treated group (C4), and after 4 days of storage in the GABA-treated group (G4) for analysis. Portions of the samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80 °C for transcriptome sequencing. The remaining samples were lyophilized for subsequent analyses of bioactive compounds, antioxidant capacity, and quasi-targeted metabolomics.

Sensory quality evaluation

-

A trained panel scored the overall sensory quality on a five-tier scale adapted from our previous study[14], where 5 denoted excellent products with a freshly harvested appearance, 3 indicated acceptable quality, and 1 represented samples that are unsuitable for marketing. Evaluations were conducted under consistent lighting with a randomized sample order and blinded coding to minimize bias.

Chlorophyll and carotenoid content

-

Freeze-dried tissue was extracted with acetone, and pigments in the clarified extract were resolved by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Analyses were performed on an Agilent 1260 system equipped with a variable-wavelength detector (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, USA). An RP-C18 column (150 mm × 3.9 mm, 4 µm; Waters) operated at 30 °C was used with a binary program consisting of isopropanol (A) and 80% acetonitrile–water (B). The gradient progressed from 0% A to 100% A over 45 min at 0.5 mL min−1. Absorbance was monitored at 448 and 428 nm to capture the principal maxima of carotenoids and chlorophyll-derived species, respectively, following our previous study[14]. Quantities were calculated against external standards and reported as g kg−1 dry weight.

Antioxidant activities

-

Ascorbic acid and total phenolics (TP) were quantified according to our prior protocol[14] with minor adjustments to the extraction process: Ascorbic acid was extracted in 1.0% oxalic acid, whereas TP used 50% ethanol. Ascorbic acid was separated on a Spherisorb C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; Waters) at 30 °C with 0.1% oxalic acid as the mobile phase (1.0 mL min−1) and detected with a variable wavelength detector (VWD) at 243 nm. Total phenolics were determined spectrophotometrically (Folin–Ciocalteu reaction) at 760 nm using gallic acid for calibration. 2,2'-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) and ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assays were employed to estimate the antioxidant capacity: 300 µL of extract was reacted with ABTS+ or FRAP working solutions, and absorbance was recorded at 734 and 593 nm, respectively. All indices are expressed on a dry-weight basis.

Quasi-targeted metabolomics

-

Approximately 100 mg of powdered material was extracted with precooled 80% methanol. After centrifugation (15,000 g, 4 °C, 20 min), the supernatants were diluted with liquid chromatography−mass spectrometry (LC-MS)-grade water to ~53% methanol and clarified again. LC–MS/MS runs were acquired on an ExionLC™ AD coupled to a QTRAP® 6500+ (SCIEX, USA). Compounds were separated on an Xselect HSS T3 column (2.1 mm × 150 mm, 2.5 µm) with a 20-min linear gradient. Data were collected in both electrospray ionization (ESI) polarities using multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions. A pooled quality control (QC) sample (equal aliquots from all the samples) was injected periodically to monitor retention time and signal stability. Annotation combined an in-house library (retention time and Q1/Q3 ion pairs with optimized declustering potential [DP] and collision energy [CE]) with public resources (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes [KEGG], Human Metabolome Database [HMDB], LIPIDMaps). Data processing used metaX for normalization and multivariate modeling (principal component analysis [PCA], partial least squares with discriminant analysis [PLS-DA] with variable importance in projection [VIP] scores), alongside univariate tests (Student's t-test) and fold change (FC) calculations. Metabolites meeting VIP > 1, p < 0.05, and FC ≥ 1.2 or ≤ 0.83 were designated as differentially accumulated (see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2).

Transcriptome sequencing

-

Lateral buds from the C0, C4, and G4 groups were collected (three biological replicates each) for RNA-seq performed by Biomarker Technologies (Beijing, China). After adapter removal and quality filtering, paired-end reads were mapped to the Brassica juncea reference genome using HISAT2. Gene abundance was normalized as fragments per kilobase of transcript per million (FPKM). Differential expression was assessed with DESeq2 under a negative binomial framework, and multiple testing correction applied the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure. Genes with |log2FC| ≥ 1 and a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.01 were considered to be differentially expressed (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4). KEGG-based functional enrichment used a corrected p < 0.05 as the significance threshold. Selected genes were validated by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR); primer sequences and amplification conditions are provided in Supplementary Table S5 and Supplementary Fig. S1.

Weighted expression trend analysis

-

To evaluate the overall expression dynamics of genes with multiple copies, we applied a weighted log2FC strategy inspired by the weighted average difference (WAD) method proposed by Kadota et al.[26]. This approach gives greater influence to gene copies with higher expression levels in determining the overall transcriptional trends.

Determination of expression weights

-

The relative contribution of each gene copy i was determined by its mean FPKM value across the two conditions being compared:

$ {\text{w}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{(C0 vs C4)}}={\text{(FPKM}}_{\text{i}\text{,}\text{C0}}+{\text{FPKM}}_{\text{i}\text{,}\text{C4}}\text{)}/\text{2} $ $ {\text{w}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{(C4 vs G4)}}={\text{(FPKM}}_{\text{i}\text{,}\text{C4}}+{\text{FPKM}}_{\text{i}\text{,}\text{G4}}\text{)}/\text{2} $ Computation of weighted log2 fold change

-

The expression trend of a gene was calculated as the weighted average of log2FC values across all gene copies, with the weights derived as shown above.

$ {\text{Trend}}_{\text{gene}}^{\text{(C0 vs C4)}}=\Bigg({\sum }_{\text{i}=1}^{\text{n}}{\text{w}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{(C0 vs C4)}}\text{∙}{\text{log}}_{\text{2}}{\text{FC}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{(C0 vs C4)}}\Bigg)\Bigg/{\sum }_{\text{i}=1}^{\text{n}}{\text{w}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{(C0 vs C4)}} $ $ {\text{Trend}}_{\text{gene}}^{\text{(C}\text{4}\;\text{vs}\;\text{G}\text{4)}}=\Bigg({\sum }_{\text{i}=1}^{\text{n}}{\text{w}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{(C}\text{4}\;\text{vs}\;\text{G}\text{4)}}\text{∙}{\text{log}}_{\text{2}}{\text{FC}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{(C}\text{4}\;\text{vs}\;\text{G}\text{4)}}\Bigg)\Bigg/{\sum }_{\text{i}=1}^{\text{n}}{\text{w}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{(C}\text{4}\;\text{vs}\;\text{G}\text{4)}} $ A positive weighted log2FC indicates overall upregulation of the gene, whereas a negative value suggests overall downregulation. This weighted approach allows a nuanced comparison between the natural senescence process and GABA-induced changes, while accounting for copy number and expression levels.

Statistical analysis

-

Statistical analyses were carried out in SPSS 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Group differences were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Correlation networks were visualized with Cytoscape 3.5.1.

-

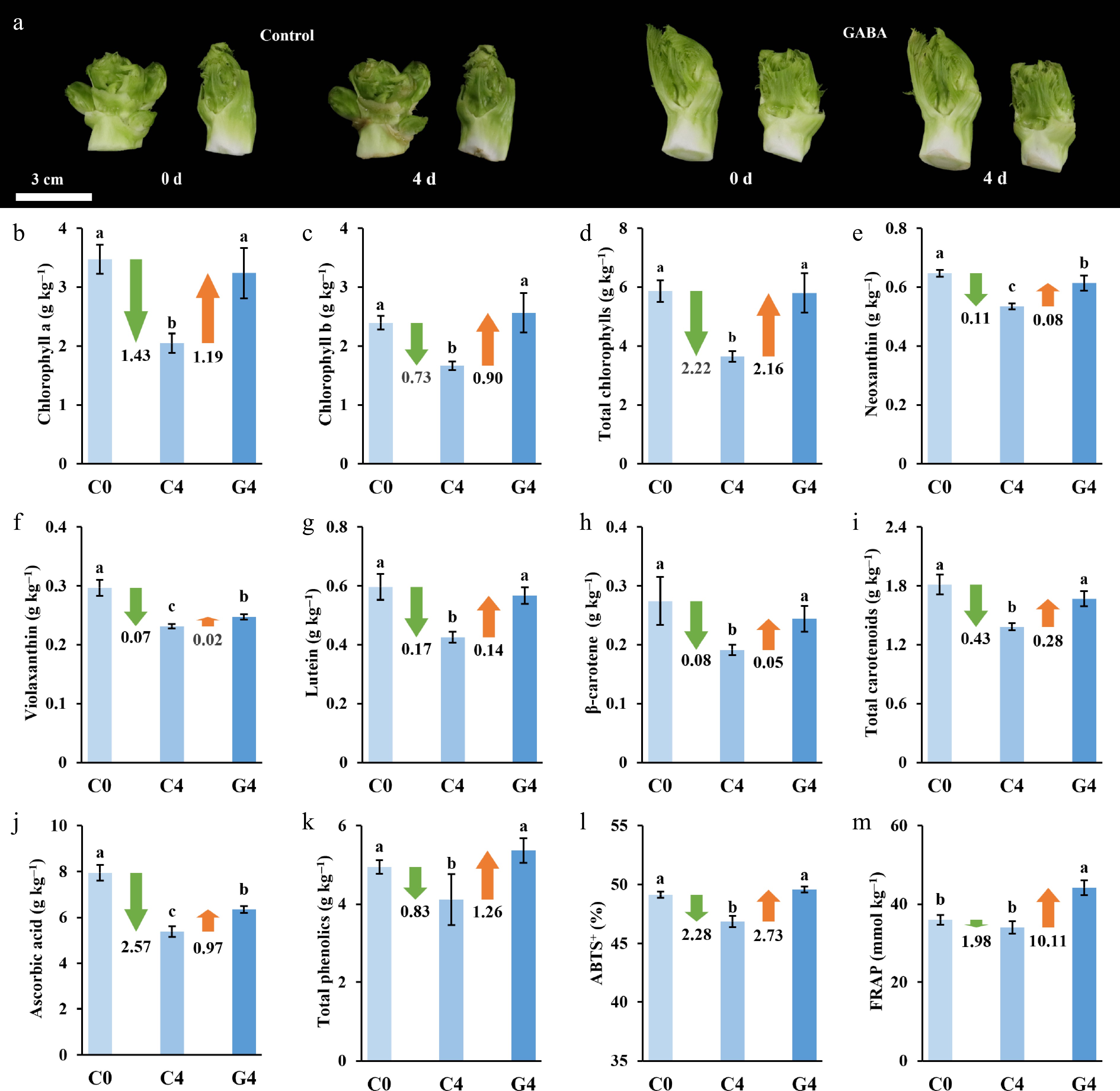

After 4 days of storage at 20 °C, the lateral buds in the control group exhibited pronounced wilting and visible browning at the cut surface. In contrast, GABA-treated samples showed less wilting and minimal browning, maintaining a fresher and greener appearance (Fig. 1a). Consistently, sensory evaluation confirmed these observations: The visual acceptability score of the control decreased from 5.0 on Day 0 to 2.5 on Day 4, whereas GABA-treated sprouts maintained a significantly higher score of 3.2 on Day 4, indicating improved appearance quality during storage (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Figure 1.

Effects of GABA treatment on the visual appearance and physiological quality of baby mustard during postharvest storage. (a) Representative images of lateral buds at 0 days, and after 4 days of storage under the control and GABA treatment conditions. (b)–(m) Changes in physiological indicators, including (b) chlorophyll a, (c) chlorophyll b, (d) total chlorophylls, (e) neoxanthin, (f) violaxanthin, (g) lutein, (h) β-carotene, (i) total carotenoids, (j) ascorbic acid, (k) total phenolics, (l) ABTS, and (m) FRAP. Values are the means ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Total chlorophyll content in the control group decreased by 39.0%, whereas GABA treatment effectively preserved the initial level and resulted in a 1.6-fold higher chlorophyll content compared to the control on Day 4. Similarly, total carotenoid content decreased by 22.2% in the control, whereas the reduction was largely alleviated by the GABA treatment, maintaining a 1.2-fold higher level. Similar protective effects were observed for individual pigments such as chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, neoxanthin, violaxanthin, lutein, and β-carotene, all of which were better preserved under the GABA treatment (Fig. 1b–i).

Ascorbic acid and total phenolic contents in the control group decreased by 32.5% and 16.3%, respectively, whereas GABA-treated samples showed increased levels on Day 4, reaching 1.3-fold and 1.2-fold higher values than those in the control group, respectively (Fig. 1j, k). Antioxidant capacity measured by the ABTS and FRAP assays also exhibited similar trends. ABTS activity declined slightly in the control group but remained stable under the GABA treatment. FRAP activity in the GABA-treated group was 1.3-fold higher than in the control on Day 4 (Fig. 1l, m). These results demonstrate that GABA effectively delayed postharvest senescence by maintaining appearance quality and enhancing antioxidant potential. This protective effect may be associated with the transcriptional regulation of phenylpropanoid metabolism and antioxidant enzymes, as revealed by the omics analyses described below.

Global metabolic and transcriptional changes in response to GABA

-

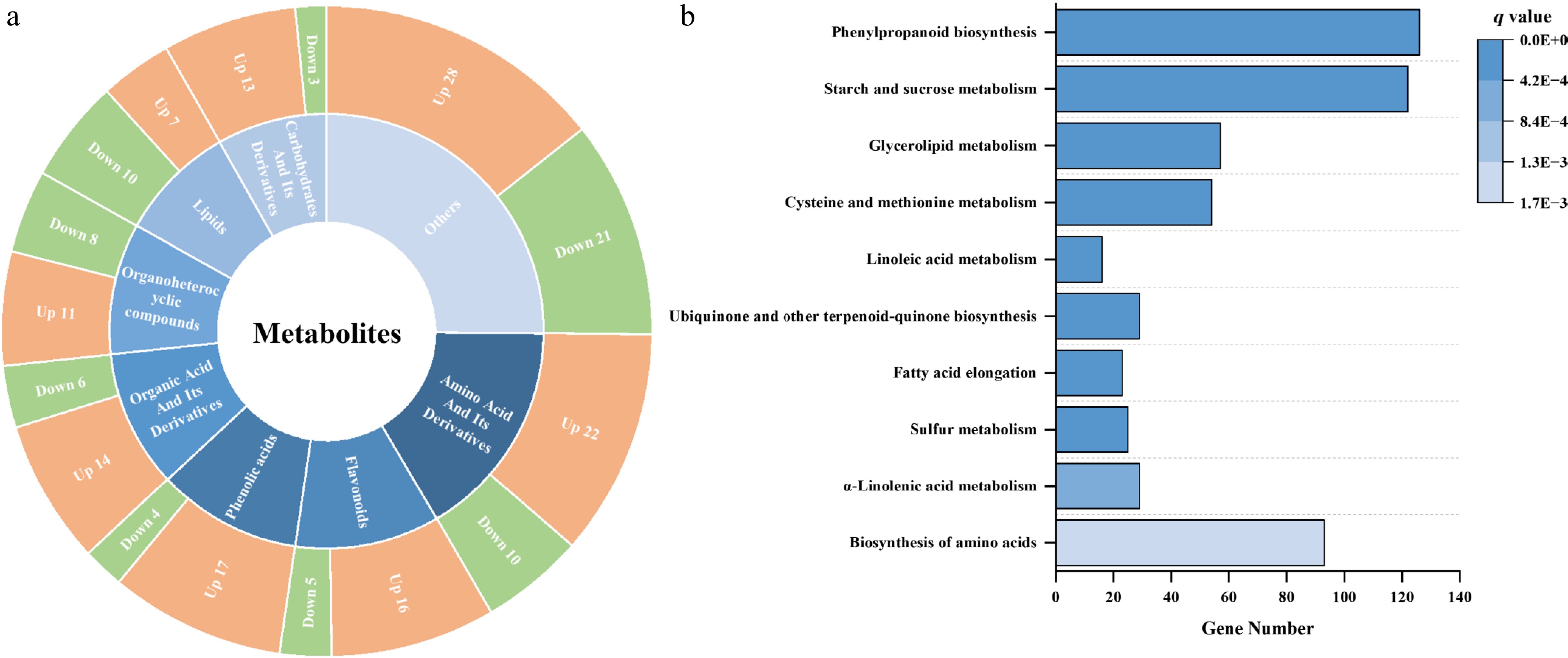

After 4 days of storage, 195 differentially accumulated metabolites (DAMs) were identified between the GABA-treated and control samples (Supplementary Table S2 and Fig. 2a). These metabolites covered a wide range of categories, mainly including amino acids and their derivatives (32), flavonoids (21), phenolic acids (21), organic acids and their derivatives (20), organoheterocyclic compounds (19), lipids (17), and carbohydrates and their derivatives (16). Among them, most amino acids (22/32), flavonoids (16/21), phenolic acids (17/21), and carbohydrates (13/16) were upregulated under the GABA treatment, suggesting enhanced nutritional and metabolic stability during postharvest storage.

Figure 2.

Overview of differentially accumulated metabolites (DAMs) and gene enrichment between the control and GABA-treated samples after 4 days of storage. (a) Pie chart summarizing the classification and number of upregulated and downregulated DAMs between control and GABA-treated baby mustard. (b) KEGG enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified between the control and GABA treatment groups after 4 days.

Transcriptomic analysis of the same comparison (C4 vs G4) identified 5,912 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (|log2FC| ≥ 1, FDR < 0.01) (Supplementary Table S4). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs revealed that among the top 10 enriched pathways, biosynthesis of amino acids, starch and sucrose metabolism, and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis contained the highest numbers of DEGs (Fig. 2b). These pathways also corresponded closely to the dominant classes of DAMs, strengthening the hypothesis that GABA coordinately regulates transcription and metabolism within these networks to maintain metabolic homeostasis during storage. The general upregulation of amino acids, phenolic acids, and flavonoids, together with the activation of related biosynthetic pathways, suggests that GABA helps maintain nutrient levels and antioxidant capacity, thereby stabilizing quality during storage. On the basis of these findings, we conducted integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses, focusing on these key metabolic pathways.

Amino acid metabolism

-

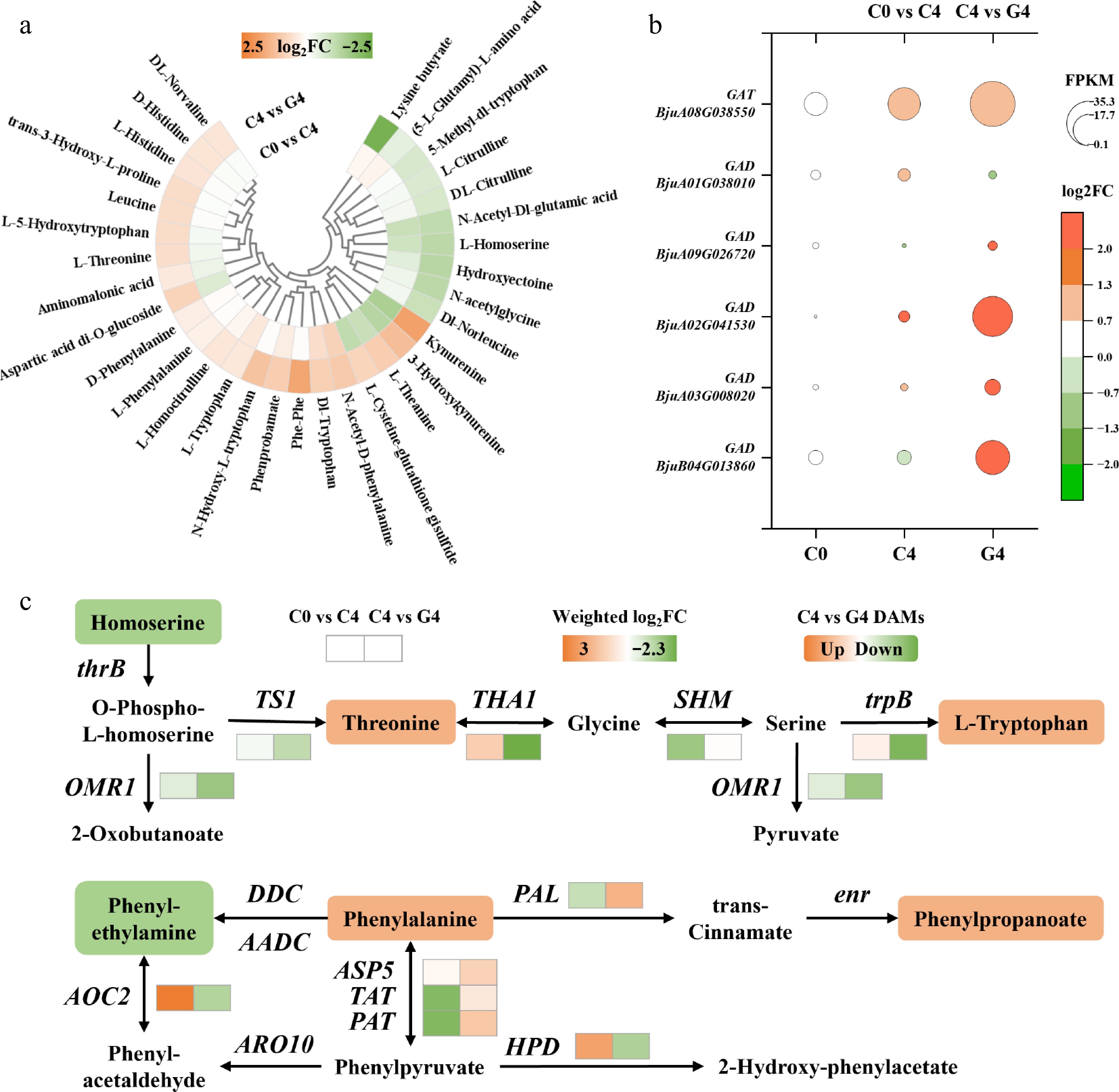

The GABA treatment markedly affected amino acid metabolism during postharvest storage. In total, 32 differentially accumulated amino acids and derivatives were detected, of which 22 were upregulated and 10 downregulated (Fig. 3a). Notably, several key amino acids and derivatives including L-tryptophan, L-phenylalanine, L-histidine, L-leucine, and L-threonine showed 1.2- to 1.8-fold increases under the GABA treatment. Multiple tryptophan-derived metabolites such as 5-hydroxytryptophan, N-hydroxy-L-tryptophan, and kynurenine were also greatly accumulated (1.6- to 3.5-fold), suggesting activation of the tryptophan catabolic branch.

Figure 3.

Effects of the GABA treatment on amino acid metabolism in baby mustard during postharvest storage. (a) Heatmap of differentially accumulated amino acids and their derivatives. (b) Expression levels (FPKM) of key genes involved in GABA biosynthesis and metabolism. (c) Heatmap of transcript changes in genes associated with amino acid metabolic pathways.

Metabolomic analysis detected changes in endogenous GABA levels. The content decreased significantly from C0 to C4 (p = 0.0008), whereas the GABA treatment partially alleviated this decline, resulting in a higher level at G4 compared with C4, although the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.08) (Supplementary Fig. S3). At the transcriptional level, several GAD genes were strongly upregulated under the GABA treatment, with fold changes ranging from 4.5 to 12.8. The expression of GAT also showed a 2.0-fold increase, suggesting that exogenous GABA may enhance biosynthetic and transport capacity of the GABA shunt pathway despite the modest metabolite change (Fig. 3b).

Weighted log2FC analysis of amino acid-related genes further revealed divergent transcriptional responses (Fig. 3c). Genes involved in phenylalanine metabolism, including phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL, 1.7) and bifunctional aspartate/prephenate aminotransferase (PAT, 1.3), were upregulated. Aspartate aminotransferase 5 (ASP5, 1.0) and tyrosine aminotransferase (TAT, 0.5) also showed positive responses. In contrast, genes associated with threonine biosynthesis and degradation, such as threonine aldolase (THA, –2.3), threonine synthase 1 (TS1, –1.0), and threonine dehydratase biosynthetic isozyme (OMR1, –1.6), were markedly suppressed. Tryptophan synthase beta chain (trpB) was also downregulated (weighted log2FC = –2.1), even though several downstream tryptophan metabolites accumulated.

These results suggest that GABA treatment coordinately modulated amino acid biosynthesis, favoring the accumulation of stress-responsive amino acids and activating its own biosynthetic and transport pathways at the transcriptional level.

Starch and sucrose metabolism

-

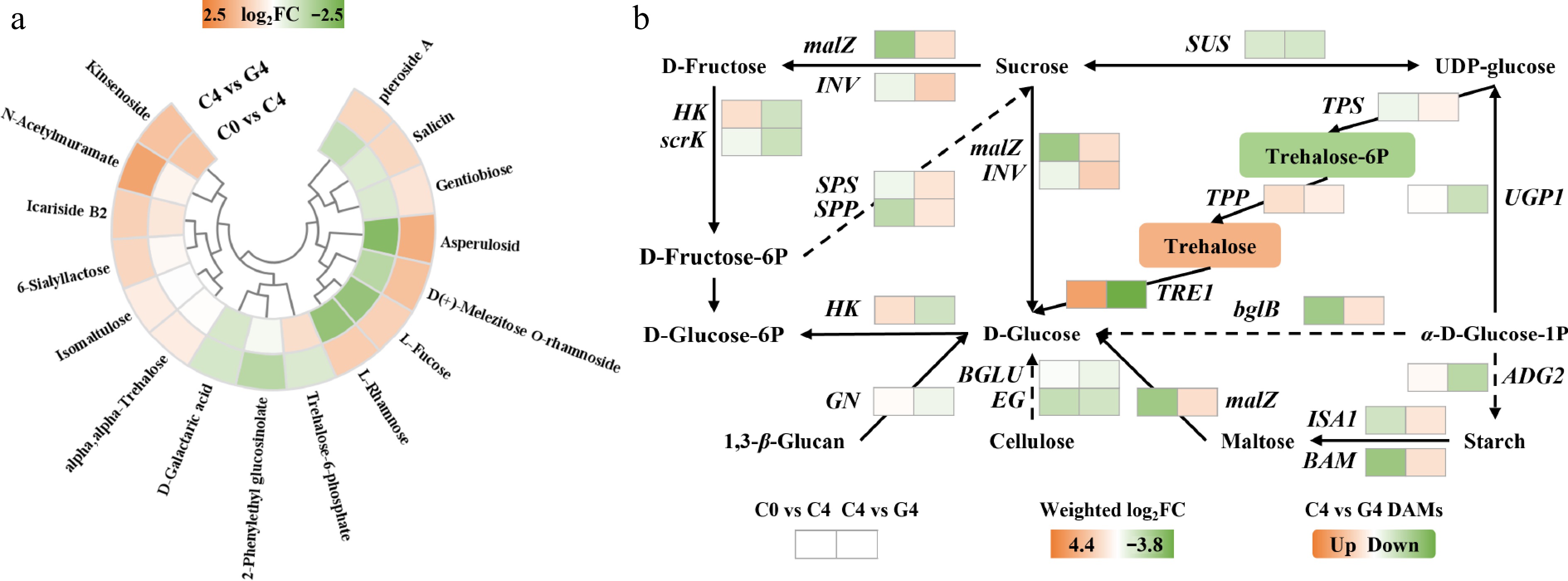

Carbohydrate metabolism was substantially modulated by the GABA treatment. Among the differentially accumulated carbohydrates, most showed upregulation (Fig. 4a). Representative sugars such as L-fucose (1.8-fold), melezitose (2.3-fold), isomaltulose (1.3-fold), gentiobiose (1.4-fold), and asperulosidic acid (2.9-fold) accumulated at higher levels in the GABA-treated samples, indicating improved carbohydrate retention during postharvest storage. Although trehalose-6-phosphate (T6P) showed a slight decrease (0.64-fold), the levels of its downstream product trehalose increased (1.3-fold). This pattern suggests that the accumulation of trehalose under the GABA treatment may be driven less by enhanced synthesis through the trehalose-phosphate synthase (TPS) and trehalose-phosphate phosphatase (TPP) pathway and more by reduced degradation, consistent with the observed strong downregulation of TRE1 (weighted log2FC = –3.8).

Figure 4.

Effects of GABA treatment on carbohydrate metabolism in baby mustard during postharvest storage. (a) Heatmap of differentially accumulated carbohydrate metabolites. (b) Heatmap of transcript changes in genes involved in starch and sucrose metabolism pathway.

Transcriptomic analysis revealed that multiple genes involved in starch and sucrose metabolism were differentially expressed under the GABA treatment (Fig. 4b). Sucrose synthase (SUS) and fructokinase (scrK) were downregulated (weighted log2FC = −1.1 and −1.4), whereas sucrose-phosphate synthase 1 (SPS1, 1.2) and sucrose-phosphatase 2 (SPP2, 1.1) were upregulated, indicating a shift toward sucrose biosynthesis. Similarly, beta-fructofuranosidase (INV, 2.2) and alpha-glucosidase (malZ, 1.5) were upregulated, potentially enhancing sucrose cleavage and the availability of glucose. The trehalose metabolism pathway also exhibited transcriptional changes. TPS and TPP were upregulated (weighted log2FC = 0.6 and 0.8, respectively), whereas trehalase (TRE1) was strongly downregulated (–3.8), which may contribute to the net accumulation of trehalose. Additionally, beta-amylase (BAM, 1.4) and isoamylase (ISA1, 1.2) were upregulated, indicating enhanced starch breakdown to support soluble sugar levels.

These results suggest that GABA treatment maintains carbohydrate homeostasis by promoting the accumulation of sucrose and trehalose, likely contributing to osmotic regulation and energy supply during postharvest senescence.

Phenylpropanoid metabolism

-

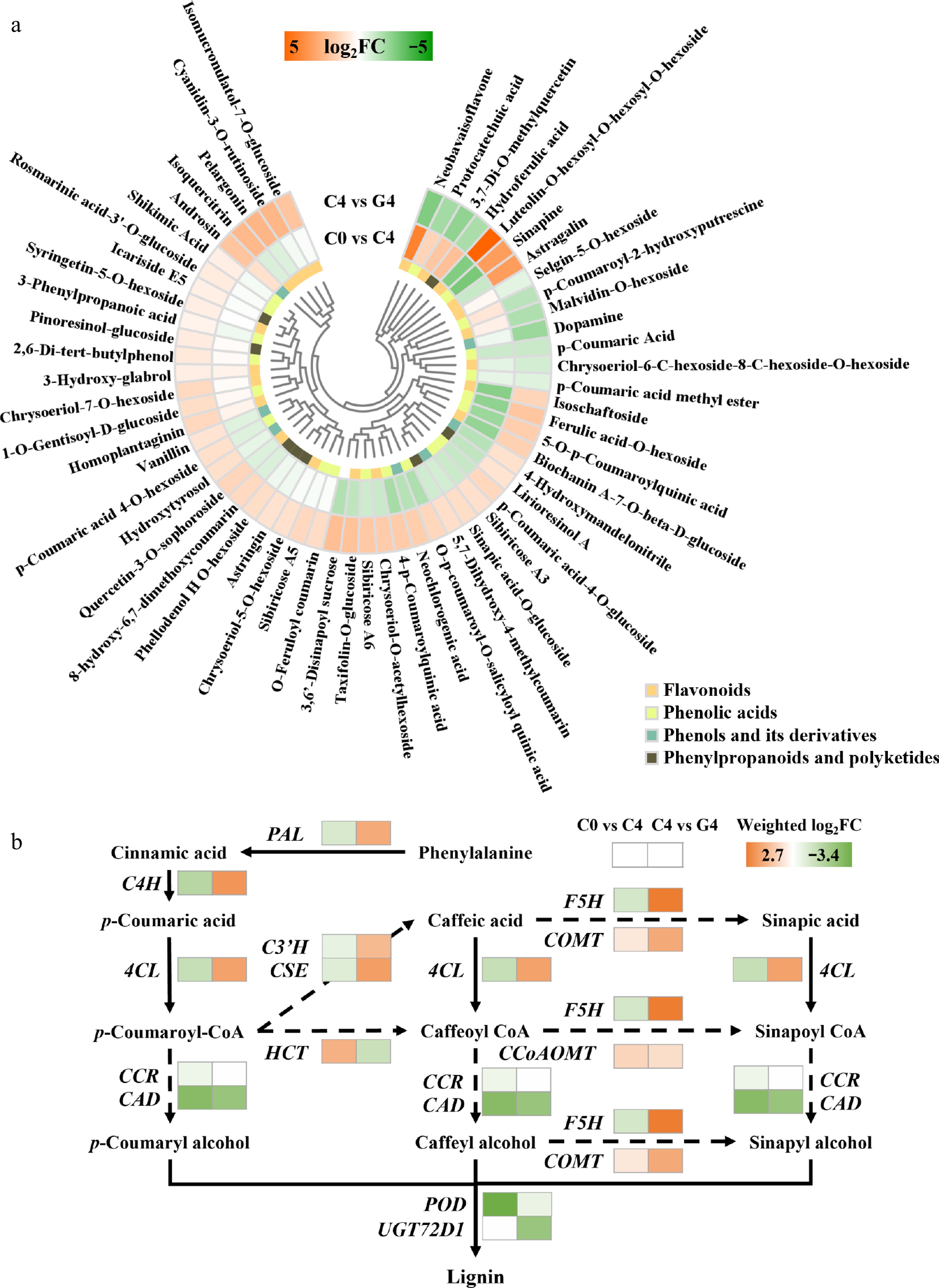

The GABA treatment strongly promoted the accumulation of phenylpropanoid metabolites, which are critical for antioxidant defense and maintaining postharvest quality (Fig. 5a). Among the DAMs, a majority of the flavonoids, phenolic acids, and coumarin derivatives were upregulated. For instance, luteolin-O-hexosyl-O-hexosyl-O-hexoside showed a dramatic 33.5-fold increase, whereas other compounds such as sinapine (9.0-fold), astragalin (9.2-fold), chrysoeriol derivatives (2.3–3.1-fold), isoquercitrin (4.8-fold), cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside (5.1-fold), and pelargonin (5.2-fold) were also substantially upregulated. These results suggest enhanced flavonoid biosynthesis and antioxidant capacity under GABA treatment.

Figure 5.

Effects of GABA treatment on phenylpropanoid metabolism in baby mustard during postharvest storage. (a) Heatmap of differentially accumulated phenylpropanoid-related metabolites. (b) Heatmap of transcript changes in genes involved in the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway.

Transcriptomic analysis revealed that GABA upregulated key genes in the phenylpropanoid pathway (Fig. 5b). Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL), 4-coumarate–CoA ligase (4CL), and trans-cinnamate 4-monooxygenase (C4H) were upregulated with weighted log2FC values of 1.7, 1.9, and 2.2, respectively, indicating activation of the core phenylpropanoid backbone. Downstream genes involved in lignin and flavonoid biosynthesis, such as caffeoylshikimate esterase (CSE, 2.0), ferulate-5-hydroxylase (F5H, 2.7), and caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase (COMT, 1.8), were also strongly induced. Moreover, 5-O-(4-coumaroyl)-D-quinate 3'-monooxygenase (C3'H) was upregulated (1.4), enhancing caffeic acid derivatives.

In contrast, several genes associated with glycosylation and downstream conversion, including uridine diphosphate (UDP)-glycosyltransferase UGT72D1 (−2.4) and shikimate O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase (HCT, −1.3), were suppressed. The downregulation of cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD, −2.4) and peroxidase (POD, −0.5) suggested the possible inhibition of lignin polymerization, potentially shifting carbon flux toward soluble phenolics.

Together, these results indicate that GABA treatment enhances phenylpropanoid biosynthesis by transcriptionally activating structural genes and promoting the accumulation of antioxidant flavonoids and phenolic acids, contributing to delayed senescence and improved postharvest quality.

Regulation of antioxidant enzymes and ethylene signaling

-

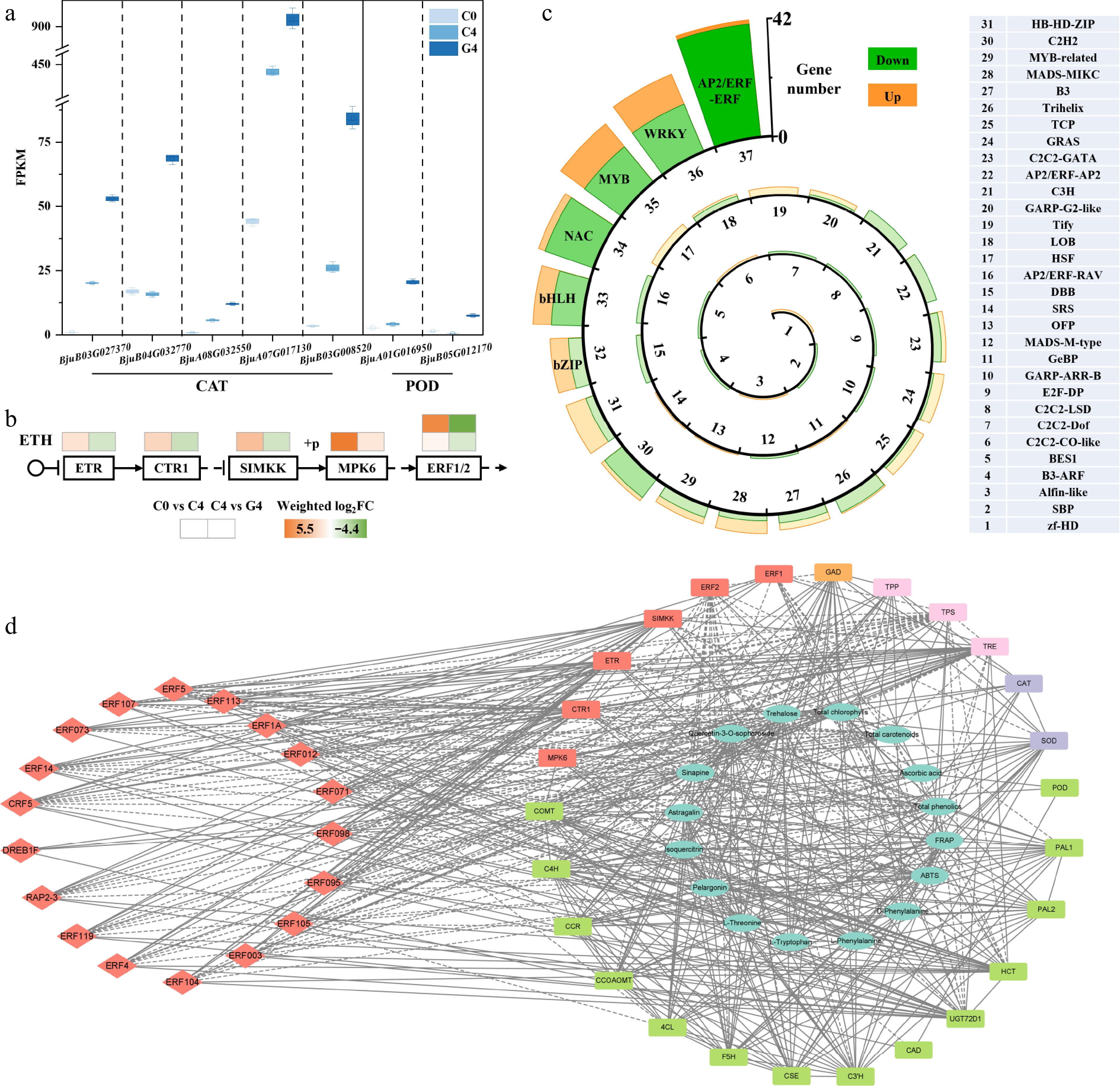

At the transcriptional level, several antioxidant enzyme genes were upregulated (Fig. 6a). Specifically, five copies of CAT showed 2.1- to 4.4-fold increases, and two copies of SOD were markedly upregulated by 4.9- and 12.4-fold. These results align with the physiological observations of enhanced antioxidant capacity (ABTS and FRAP) and maintained ascorbic acid content under the GABA treatment.

Figure 6.

Effect of GABA treatment on transcriptional regulation related to antioxidant defense and ethylene signaling in baby mustard. (a) FPKM values of differentially expressed catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) genes. (b) Heatmap of transcript changes in genes involved in the ethylene signaling pathway. (c) Classification and number of differentially expressed transcription factors with opposite trends between C0 and C4 and between C4 and G4. (d) Correlation network illustrating the relationships among physiological traits, metabolites, key genes, and transcription factors. The dashed lines between indices represent negative correlations, whereas solid lines represent positive correlations. All correlations in the figure reflect Pearson correlation coefficient values above the threshold (|ρ| > 0.9).

In addition, key genes in the ethylene signaling pathway were downregulated (Fig. 6b). Expression of ethylene receptor (ETR), constitutive triple response 1 (CTR1), and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (SIMKK) decreased by weighted log2FC values of –1.3, –1.6, and –1.4, respectively, suggesting suppression of early signal transduction. Furthermore, the ethylene-responsive transcription factors ERF1 and ERF2 were notably repressed (–4.4 and –1.2, respectively), indicating that GABA may delay senescence by inhibiting downstream ethylene signaling cascades.

Analysis of the differentially expressed transcription factors (TFs) revealed widespread transcriptional suppression (Fig. 6c). Among six major TF families, AP2/ERF-ERF showed the most substantial repression, with 40 out of 42 differentially expressed ERF members being downregulated. Other families such as WRKY (12 upregulated and 18 downregulated), MYB (11 upregulated and 16 downregulated), and NAC (3 upregulated and 18 downregulated) also showed a predominance of downregulation. This pattern suggests a broad-scale transcriptional reprogramming under GABA treatment, potentially contributing to delayed postharvest senescence.

Integrated correlation network under GABA-alleviated postharvest senescence

-

A correlation network was constructed based on selected quality indicators, key differential metabolites, representative pathway genes, and transcription factors (Fig. 6d). Central physiological traits such as total chlorophylls, total phenolics, and antioxidant capacity were positively associated with amino acids (L-threonine, phenylalanine), carbohydrates (trehalose), and flavonoids (astragalin, isoquercitrin), indicating their roles in maintaining quality. Genes involved in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis (PAL, 4CL, CSE), antioxidant enzymes (CAT, SOD), and GABA metabolism (GAD) showed strong positive correlations with these metabolites and traits. In contrast, many ERF transcription factors (ERF1, ERF2, etc.) and ethylene-related genes (ETR, CTR1) were negatively correlated with quality indicators and stress-related genes, suggesting that GABA may alleviate senescence by suppressing ethylene signaling and ERF expression.

-

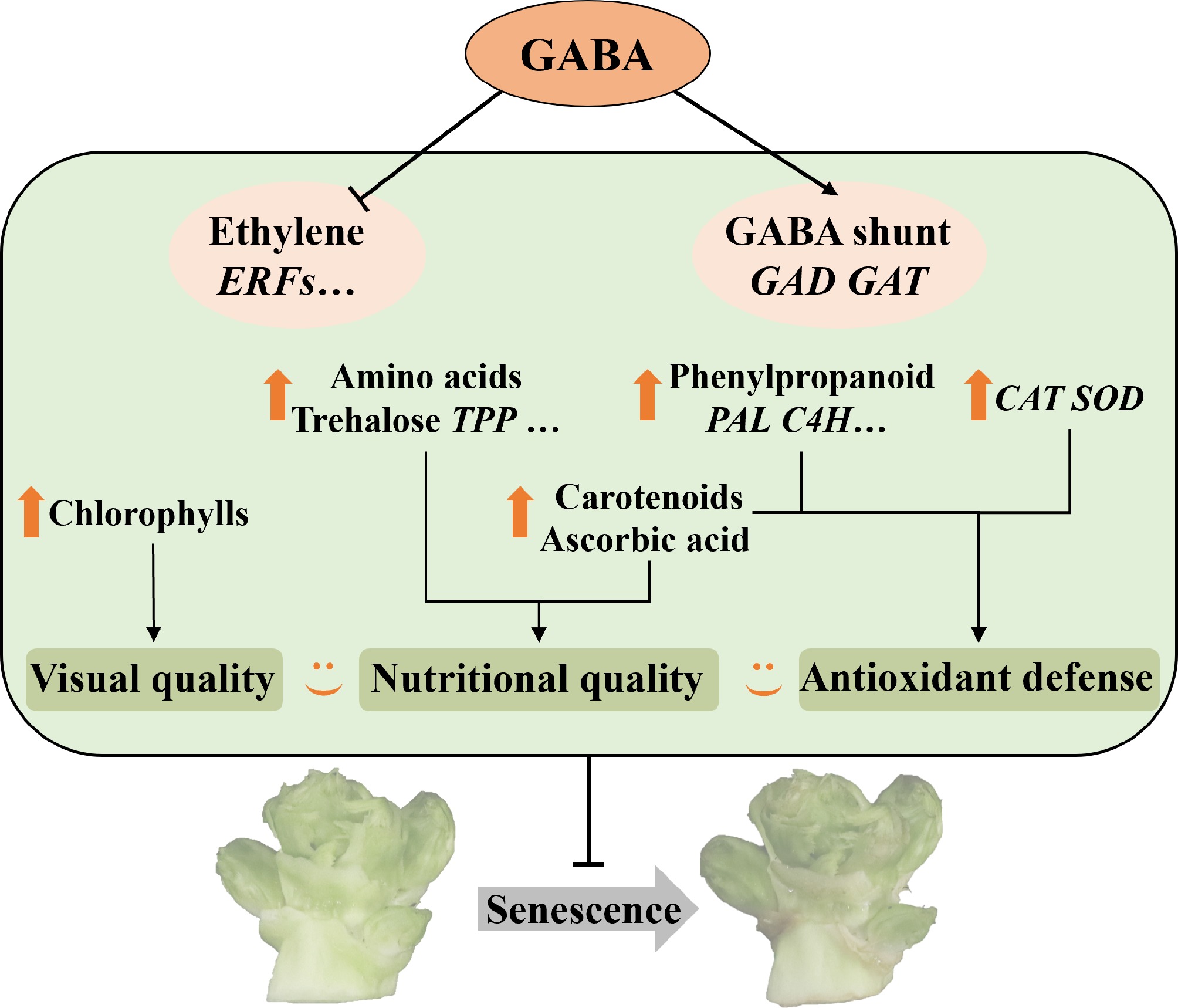

Postharvest deterioration is a major factor limiting the shelf life and marketability of baby mustard, particularly caused by mechanical damage incurred during trimming and handling. Although GABA has been shown to delay senescence in various horticultural crops, its role in Brassica vegetables, including baby mustard, remains poorly understood. In this study, we explored the physiological and molecular responses of GABA-treated lateral buds during storage and identified multiple mechanisms underlying quality preservation. On the basis of combined metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses, we discuss how GABA mitigates senescence by preserving visual and nutritional traits, modulating amino acid and sugar metabolism, enhancing phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, and suppressing ethylene signaling and ERF transcription factors (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Proposed model for maintaining quality and the regulation mechanism induced by GABA in baby mustard after harvest.

GABA treatment preserved the visual and nutritional quality in postharvest baby mustard

-

GABA treatment effectively delayed senescence by preserving external quality and maintaining key physiological traits. Compared with the control, GABA-treated lateral buds exhibited reduced wilting and browning, retained a greener appearance, and had higher levels of total chlorophylls and carotenoids after 4 days of storage. These results are consistent with findings in Euryale ferox, where GABA treatment alleviated discoloration and suppressed chlorophyll degradation during cold storage[27]. A similar outcome was observed in Mesembryanthemum crystallinum (ice plant)[6], where exogenous GABA maintained chlorophyll content and mitigated visual deterioration by enhancing membrane integrity and reducing oxidative stress.

Our results also showed that GABA-treated samples retained higher levels of ascorbic acid compared with the control, indicating delayed oxidative degradation. Similar effects have been reported in loquat[8] and kiwifruit[28], where GABA maintained ascorbic acid by regulating biosynthesis and catabolism. Moreover, the total phenolic content in baby mustard remained stable or even increased following GABA treatment, likely contributing to enhanced antioxidant capacity. This trend is consistent with previous observations in loquat[8] and ice plant[6], where GABA promoted phenolic accumulation and free radical scavenging, thereby delaying senescence-associated quality loss.

GABA modulated the primary metabolism to support nutritional stability in postharvest baby mustard

-

Postharvest senescence is closely linked to disruptions in primary metabolic pathways, particularly those involving amino acids and sugars[29,30]. In this study, the GABA treatment modulated these pathways, contributing to the preservation of nutritional quality during storage. Among the 32 differentially accumulated amino acid-related metabolites identified, 22 were upregulated following the GABA treatment, including L-threonine, L-tryptophan, and L-phenylalanine. Although endogenous GABA levels remained unchanged, the upregulation of multiple GAD and GAT genes indicated activation of the GABA shunt. This aligns with previous findings in pumpkin, where GABA enhanced GAD activity and mitigated oxidative stress[31]. Similarly, in fresh-cut carrots, glutamate treatment activated the GABA shunt by increasing GAD and GABA-T activities, reducing tissue whitening[19].

Carbohydrate metabolism also responded positively to GABA. Although sugar levels declined in control samples, GABA treatment maintained higher levels of trehalose, L-rhamnose, and other soluble carbohydrates. Expression levels of sugar metabolism genes such as SPS, INV, and BAM were upregulated. These enzymes play central roles in the synthesis and mobilization of sugar, supporting osmotic regulation, membrane stability, and energy supply during storage[7]. Similar preservation of soluble sugars under GABA treatment has been observed in strawberry[32] and grape[33]. Although the role of sugars in senescence varies across species[34], our results are consistent with evidence in cabbage that sustained sugar levels contribute to delayed leaf senescence. Notably, trehalose is known to stabilize membranes and enhance ROS scavenging, which may help explain the reduced wilting and maintenance of antioxidant capacity observed in GABA-treated baby mustard[35].

Furthermore, correlation analysis revealed strong positive associations among trehalose, amino acids, and antioxidant indicators, suggesting that GABA-mediated metabolic stability may support antioxidant defense and delay senescence in baby mustard.

GABA treatment enhanced phenylpropanoid metabolism and antioxidant defense in postharvest baby mustard

-

GABA treatment enhanced the accumulation of phenylpropanoid-derived secondary metabolites, including sinapine, astragalin, isoquercitrin, and pelargonin, with fold changes ranging from 4.8 to 9.2. These compounds are recognized for their antioxidant properties, as reflected in the increased FRAP and ABTS activities observed in GABA-treated samples. In ice plant, similar increases in phenolics and antioxidant enzyme activities under GABA treatment delayed senescence and improved stress tolerance during storage[6].

Transcriptomic analysis revealed that this metabolic response was accompanied by transcriptional upregulation of key phenylpropanoid biosynthesis genes, including PAL, 4CL, CSE, COMT, and F5H. These genes are central to the synthesis of flavonoids and phenolic acids and serve as markers of stress-induced secondary metabolism[36]. Similarly, in loquat, GABA upregulated PAL expression and increased flavonoid levels, improving oxidative stability and reducing membrane damage[8].

GABA also promoted the expression of antioxidant enzyme genes such as CAT and SOD in baby mustard. These enzymes work synergistically with phenolics to scavenge ROS and prevent oxidative damage[37]. Comparable effects have been reported in sweet cherry[38], where GABA treatment elevated phenolic and anthocyanin levels while enhancing CAT and POD activities, thereby extending shelf life.

Although our quasi-targeted metabolomic analysis is supported by MS/MS-level identifications and stable QC metrics, this study did not include independent absolute quantification for selected metabolite classes (e.g., amino acids, trehalose). This constitutes a limitation. In future work, we will prioritize targeted LC-MS/MS assays for sentinel metabolites to corroborate the observed trends at an absolute concentration level.

GABA treatment suppressed ethylene signaling and modulated transcriptional regulation in postharvest baby mustard

-

Although baby mustard is a nonclimacteric vegetable, ethylene signaling still plays an important role in the postharvest senescence of Brassica crops. In broccoli, hydrogen-rich water, controlled atmosphere, and 1-methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) treatments delayed yellowing and quality loss by suppressing ethylene activity, whereas ethylene exposure accelerated deterioration[39−41]. Similarly, in nonheading Chinese cabbage, ethylene signaling was shown to antagonize DNA methylation, with EIN3A repressing the methylation maintenance enzyme CMT2 and activating senescence-associated genes, thereby accelerating leaf senescence[42]. These studies highlight ethylene as a key accelerator of senescence in Brassica vegetables. Consistent with this, transcriptomic data indicated that GABA treatment suppressed ethylene signal transduction in baby mustard by downregulating key signaling components, including ETR and CTR1. This repression extended to SIMKK, a MAPK cascade member associated with ethylene-mediated senescence signaling[43]. Notably, 40 out of 42 ERF transcription factors were downregulated, suggesting that GABA broadly suppresses ethylene-responsive transcription.

As downstream regulators of ethylene signaling, ERFs activate genes involved in chlorophyll degradation, ROS accumulation, and cell wall remodeling, all of which promote senescence[44]. The downregulation of ERFs under GABA treatment may therefore delay senescence-related physiological changes. This is consistent with findings in tomato, where GABA treatment improved resistance to Botrytis cinerea by modulating ethylene pathways[10]. In peach, PpERF17 promoted the accumulation of GABA and jasmonic acid through a feedback mechanism, alleviating chilling injury and enhancing hormonal coordination[45].

Moreover, GABA also affected other transcription factor families. Most differentially expressed members of the WRKY, MYB, NAC, bZIP, and bHLH families were downregulated, reflecting broad suppression of stress-related transcriptional responses. Network analysis revealed strong negative correlations between ERFs and several quality-related parameters, including total chlorophylls, ascorbic acid, and phenolic content. These correlations further support the idea that ERFs contribute to postharvest deterioration and that GABA mitigates senescence by repressing their expression.

-

Exogenous GABA treatment effectively delayed postharvest senescence in baby mustard by preserving its appearance and nutritional quality. GABA maintained chlorophyll, carotenoids, ascorbic acid, and phenolics, and enhanced antioxidant capacity. Metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses revealed that GABA promoted amino acid, sugar, and phenylpropanoid metabolism; upregulated antioxidant-related genes; and suppressed ethylene signaling as well as ERF transcription factors. These findings highlight GABA as a promising and safe strategy for improving postharvest shelf life in Brassica vegetables.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32372732, 32372683, 32460750), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2025ZNSFSC1112, 2024NSFSC0404, 2023ZYD0090), Chongqing Science and Technology Program (CSTB2024TIAD-CYKJCXX0025), Sichuan Innovation Team of National Modern Agricultural Industry Technology System (SCCXTD-2024-05), Joint Research on Mustard Breeding in Sichuan Province (2025YZ002), the Science and Technology Research Project of Guizhou Provincial Department of Education (Qian JiaoJi [2024]016), Chengdu Science and Technology Program (2024-YF05-02375-SN), the Expert Workstation Program in Cuiping District, Yibin City (SYZJ202401), and the Yibin Science and Technology Program (2024NY007).

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: writing – original draft preparation: Di H; investigation: Di H, Escalona VH, Zhang X, Zhou Y, Zhong L, Yu X, Huang Z, Li H; data curation: Chen Z, Yang S, Liu D, Li Y, Zhang H, Liang K, Tang Y; funding acquisition: Chen Z, Yu X, Huang Z, Zhang F, Sun B; writing – review and editing: Zhang F, Sun B; conceptualization: Sun B. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Differentially accumulated metabolites (DAMs) from C0 vs C4 based on VIP > 1, fold change ≥ 1.2 or ≤ 0.83, and p < 0.05.

- Supplementary Table S2 Differentially accumulated metabolites (DAMs) from C4 vs G4 based on VIP > 1, fold change ≥ 1.2 or ≤ 0.83, and p < 0.05.

- Supplementary Table S3 A dataset of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in comparison pair C0 vs C4.

- Supplementary Table S4 A dataset of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in comparison pair C4 vs G4.

- Supplementary Table S5 Primer sequences used in this study for qRT-PCR

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Expression pattern of selected DEGs obtained by RNA-Seq and qRT-PCR.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Effects of GABA treatment on sensory parameter-acceptance of baby mustard during postharvest storage.

- Supplementary Fig. S3 Effects of GABA treatment on γ-aminobutyric acid of baby mustard during postharvest storage.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Di H, Chen Z, Escalona VH, Yang S, Zhang X, et al. 2026. Multi-omics analysis reveals the role of γ-aminobutyric acid in maintaining the postharvest quality of baby mustard (Brassica juncea var. gemmifera). Vegetable Research 6: e002 doi: 10.48130/vegres-0025-0041

Multi-omics analysis reveals the role of γ-aminobutyric acid in maintaining the postharvest quality of baby mustard (Brassica juncea var. gemmifera)

- Received: 29 June 2025

- Revised: 26 September 2025

- Accepted: 16 October 2025

- Published online: 13 January 2026

Abstract: γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is a nonprotein amino acid involved in plant stress responses and metabolic regulation. In this study, we investigated the effects of exogenous GABA on postharvest senescence in baby mustard stored at 20 °C. GABA treatment preserved external quality and delayed the loss of chlorophylls, ascorbic acid, and phenolics. Quasi-targeted metabolomics identified 195 differentially accumulated metabolites (DAMs) in the comparison between untreated and GABA-treated samples, including amino acids (e.g., threonine, phenylalanine), soluble sugars (e.g., trehalose), and phenylpropanoids (e.g., sinapine, astragalin). Transcriptomic profiling of the same comparison revealed 5,912 differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Many of these DEGs were enriched in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and antioxidant pathways, with GABA upregulating antioxidant enzyme genes and contributing to redox stability. Moreover, GABA treatment suppressed ethylene signaling by downregulating ETR, CTR1, and 40 out of 42 ethylene-responsive (ERF) transcription factors, thereby repressing ethylene-responsive transcription. These integrated responses delayed oxidative damage and maintained nutritional stability. This study provides the first omics-based evidence of GABA-mediated alleviation of senescence in baby mustard, highlighting its potential as a postharvest preservation strategy for Brassica vegetables.

-

Key words:

- γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) /

- Baby mustard /

- Metabolomics /

- Transcriptomics /

- Phenylpropanoid /

- Ethylene signaling