-

Soil respiration is a metabolic function carried out by soil organisms including microorganisms, fauna, and plant roots, during which organic matter is decomposed and carbon dioxide (CO2) is released. This process plays a crucial role in the carbon cycle of soil ecosystems[1]. The soil carbon pool, as one of the largest carbon pools in terrestrial ecosystems, serves as the main pathway through which carbon moves from the soil sphere into the atmosphere. It is also the primary mechanism by which carbon returns from the land to the atmosphere within the global carbon cycle. Consequently, even minor changes in soil respiration can lead to fluctuations in atmospheric CO2 concentrations[2], thereby affecting the carbon cycle and carbon balance of terrestrial ecosystems[3].

The process of soil respiration is comprehensively regulated by multiple key factors, including the soil's physicochemical properties, enzyme activity, microbial biomass, and carbon fractions. Among these, soil pH, as a core indicator of the soil's physicochemical properties, can influence the efficiency of organic matter transformation, the microbial community's structure, and enzyme activity, there by altering soil respiration processes and affecting the content of soil organic carbon (SOC). The chemical composition and degradability of soil organic matter (SOM) are also important factors influencing the feedback between soil CO2 emissions and climate warming. Increasing the recalcitrance of organic matter during decomposition can suppress respiration rates[4−6]. Soil enzyme activity is highly sensitive to environmental changes and plays a vital role in nutrient cycling, as well as in the formation and degradation of organic matter by catalyzing biochemical reactions. Because soil respiration depends on the metabolic activity respiratory activities of soil microorganisms, and microbial respiration is essentially an enzyme-catalyzed biochemical reaction, there is a close relationship between soil enzyme activity and soil respiration[7−9].

The soil's microbial biomass contributes to nutrient transformation and cycling by influencing the dynamics of organic matter, thereby supplying nutrients for plant growth. Its key component, microbial biomass carbon (MBC), regulates the flow of carbon and nutrients within ecosystems and is also closely associated with SOC. MBC can serve as an important indicator of the size of the organic carbon pool and plays a significant role in SOM and nutrient cycling[10−13]. SOC is a critical factor regulating soil respiration, and variations in its content significantly affect carbon storage in the soil. Labile organic carbon directly participates in the soil's biochemical processes, and its accumulation indirectly affects soil respiration by altering the carbon pool's characteristics. Currently, there is no consensus on the relationship between SOC content and respiration intensity[14−17]. For example, some studies have reported a positive correlation between carbon components and soil respiration[18], whereas others have found a negative correlation between carbon components and soil respiration[19,20]. In addition, existing studies have indicated that the relationship between carbon fractions and soil respiration may be dependent on the stage[21].

Most existing research has focused on farmland or natural forests, with relatively few studies examining the seasonal variations of soil respiration and their driving factors in urban forests[22−24]. However, urban forests are easily affected by human activities[25,26], and it remains unclear whether their respiration regulation mechanisms follow those of natural forests. Therefore, this study used the Random Forest model and the partial least squares path model (PLSPM) to investigate the effects of the soil's physicochemical properties, enzyme activity, microbial biomass, and carbon composition on soil respiration at a seasonal scale. Specifically, this study aimed to address two key questions: (1) What are the seasonal variation patterns of soil respiration? and (2) What are the key factors influencing soil respiration?

By quantitatively analyzing the impacts of these factors, this research provides a scientific basis for soil management and enhancing carbon sequestration. The findings not only offer theoretical guidance for forestry management but also provide valuable data and insights for global carbon cycle research and the development of climate change mitigation strategies, thereby contributing positively to addressing global climate change.

-

This study selected six different forest types as the research objects: a bamboo forest (BF), a Metasequoia glyptostroboides forest (MG), a Cornus officinalis forest (CO), a mixed broadleaf shrub forest (MS), a mixed pine and cypress forest (PC), and a mixed broadleaf tree forest (MT). These stands are independent of one another in terms of tree species composition and exhibit high purity and representativeness. Soil samples were collected seasonally in 2023. In each forest type, three locations were randomly selected, and rhizosphere soil samples were collected from the 0–20 cm soil layer using a soil auger. Before mixing, all visible impurities, including fallen leaves, fine roots, and pebbles, were carefully removed. The homogenized samples were placed in sterile plastic bags, sealed, and transported in an icebox to the laboratory for subsequent analyses. The sieved soil samples were divided into two portions: one portion of fresh soil was stored at 4 °C for determining soil microbial biomass and enzyme activity, whereas the other portion was air-dried naturally and purified of remaining impurities for determining the soil's physicochemical properties and carbon fractions.

Determination the of soil's physicochemical properties and soil enzyme activity

-

Soil pH was measured using a pH meter (Sartorius PB-10, Göttingen, Germany), and electrical conductivity (EC) was determined with a conductivity meter (DDS-307A, Insea Scientific Instruments, Shanghai, China). Total nitrogen (TN) content was determined via the Kjeldahl digestion method following wet digestion with sulfuric acid[27]. Total phosphorus (TP) content was determined by the NaOH alkali fusion–molybdenum–antimony antispectrophotometric method. The hydrolyzable nitrogen (HN) content was measured via the hydrolysis diffusion method Available potassium (AK) content was determined by flame photometry after ammonium acetate extraction. Available phosphorus (AP) was determined via the combined sodium bicarbonate and ammonium fluoride–hydrochloric acid methods. SOM content was determined by the potassium dichromate volumetric method[28].

Catalase (SC) activity was determined by the potassium permanganate titration method, and cellulase (SCL) activity was measured via the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid colorimetric method[29]. Sucrase (SS) activity was determined by the 3,5-dinitrobenzene disodium colorimetric method. Alkaline phosphatase (SLP) activity was measured by the phenyl phosphate method, and urease (SU) activity was determined by the phenol sodium–hypochlorite colorimetric method.

Determination of soil microbial biomass and carbon components

-

The soil MBC, soil microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN), and soil microbial biomass phosphorus (MBP) contents were determined using the chloroform fumigation–extraction method[30,31]. For this, 10 g of fresh soil was divided into three subsamples and placed in a desiccator, together with a small beaker containing 50 mL of a NaOH solution and another containing approximately 50 mL of anhydrous chloroform. The air was evacuated using a vacuum pump until the chloroform began to boil, and the vacuum was maintained for at least 2 minutes. After evacuation, the samples were kept in the dark for 24 hours, after which, the residual chloroform was removed by repeated vacuuming. Subsequently, 50 mL of a 0.5 mol/L potassium sulfate solution was added to two of the samples for determining MBC and MBN, and 50 mL of a 0.5 mol/L sodium bicarbonate solution was added to the third for determining MBP. The samples were shaken for 30 minutes, allowed to settle, and then filtered. The filtrates were stored at −15 °C until analysis. C and N concentrations in the extracts were measured using a carbon–nitrogen analyzer (multiNC 2100S, Analytik Jena, Germany), whereas the P concentration was determined by the molybdenum–antimony resistance colorimetric method.

The dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in the samples was determined via deionized water extraction and a total organic carbon (TOC) analyzer (Japan Daojing TOC-LCPH)[32]. Particulate organic carbon (POC) was extracted with sodium hexametaphosphate and determined by the potassium dichromate method with external heating[33]. Total carbon (TC) was directly measured using a carbon and nitrogen analyzer (Jena multiNC 2100S, Germany). Labile organic matter (LOM) was determined using the potassium permanganate oxidation–ultraviolet spectrophotometry method. Humic fraction organic carbon (HFOC) and light fraction organic carbon (LFOC) were quantified using the potassium dichromate method with external heating[34].

Measurement of soil respiration

-

During soil sampling, soil respiration rates were measured using a soil respiration analyzer (PRI-8610, Beijing PuriYike). Prior to measurement, plant residues and fallen leaves were carefully removed from the soil's surface. The soil respiration measuring device was placed firmly on the soil's surface, and the probe was inserted into the soil to a depth of 5–10 cm. Continuous monitoring was conducted for 30 minutes per measurement. Measurements were taken once per season, with three replicates at each sampling site to ensure biological accuracy. The respiration analyzer was connected to an electronic tablet for real-time data acquisition and flux calculation, allowing for continuous monitoring and data logging throughout the sampling period.

Statistical analysis

-

The collected data on the soil's physicochemical properties, enzyme activity, microbial biomass, carbon fractions, and soil respiration were first entered into Microsoft Excel. The average value of each indicator was calculated to obtain representative results. The processed data were then imported into Graphpad Prism (version 8.0) for visualization. Using the software's built-in functions combined with analysis of variance (ANOVA), bar charts were generated to illustrate the trends and comparative differences among the soil parameters. Subsequently, a Random Forest model was constructed using the 'randomForest' package in R (version 4.3,2) to calculate the variables' importance, and the 'rfPermute' package was applied to assess the statistical significance of the importance rankings. The explanatory power of each model was extracted and visualized using bar charts to represent the model's performance. Additionally, a heatmap was generated, based on the correlation coefficients between environmental factors and target variables, combined with the significance levels of variable importance[35]. Meanwhile, a PLSPM was developed using the 'plspm' package in R to assess the relationships among the soil's physicochemical properties, enzyme activity, microbial biomass, carbon fractions, and soil respiration. During construction of the model, path coefficients and coefficients of determination (R2) were calculated to evaluate the strength and explanatory power of the relationships[36].

-

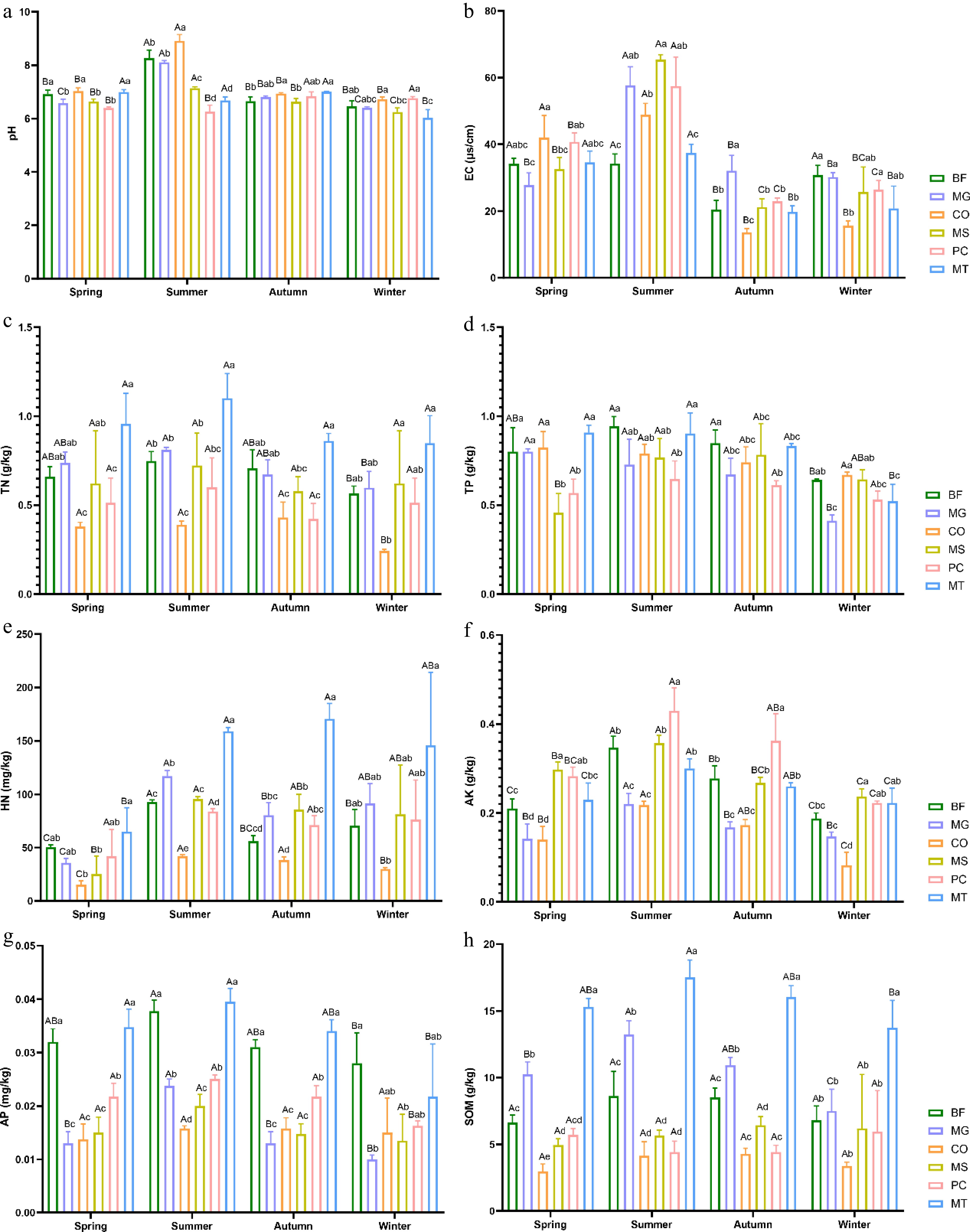

Multifactorial ANOVA was conducted to examine the seasonal variations in the soil's physicochemical factors and their differences among the six forest stands (Fig. 1a−h). The results showed that the soil pH values of all forest stands were greater than 6, indicating weak alkalinity. In spring, the MT forest stand exhibited the highest pH, TN, TP, HN, AP, and SOM content among the six forest stands. Notably, its TN, HN, and SOM contents were significantly higher than those of the other forest stands across all four seasons. In summer, the CO forest stand recorded the highest pH value, whereas the MS forest stand showed the highest EC. The BF forest stand had the highest TP content during both summer and autumn, and its EC value and AP content were the highest in winter.

Figure 1.

Seasonal variations in the soil's physicochemical factors across six forest types. (a) pH; (b) electrical conductivity (EC); (c) total nitrogen (TN); (d) total phosphorus (TP); (e) hydrolyzable nitrogen (HN); (f) available potassium (AK); (g) available phosphorus (AP); (h) soil organic matter (SOM). The six forest types are bamboo forest (BF), Metasequoia glyptostroboides forest (MG), Cornus officinalis forest (CO), mixed broadleaf shrub forest (MS), mixed pine and cypress forest (PC), and mixed broadleaf tree forest (MT) Lowercase letters indicate significant differences among different forest types within the same season (p < 0.05), whereas uppercase letters indicate significant differences among different seasons within the same forest type (p < 0.05).

Seasonal variations in the soil's physicochemical factors showed that the AK and AP in all six forest stands peaked in summer and then declined. The seasonal variation patterns of pH, TN, TP, and SOM in the BF and MG forest stands; pH and HN in the CO and MS forest stands; TP in the PC forest stand; and SOM in the MT forest stand were consistent with those observed for AK and AP. In autumn, the CO forest stand exhibited significantly higher TN and SOM contents than the other stands, whereas the MS forest stand showed significantly higher TP and SOM contents. The EC and TN content in the MS, PC, and MT forest stands followed a characteristic pattern of first increasing, then decreasing and subsequently increasing again.

Seasonal variations in soil enzyme activities

-

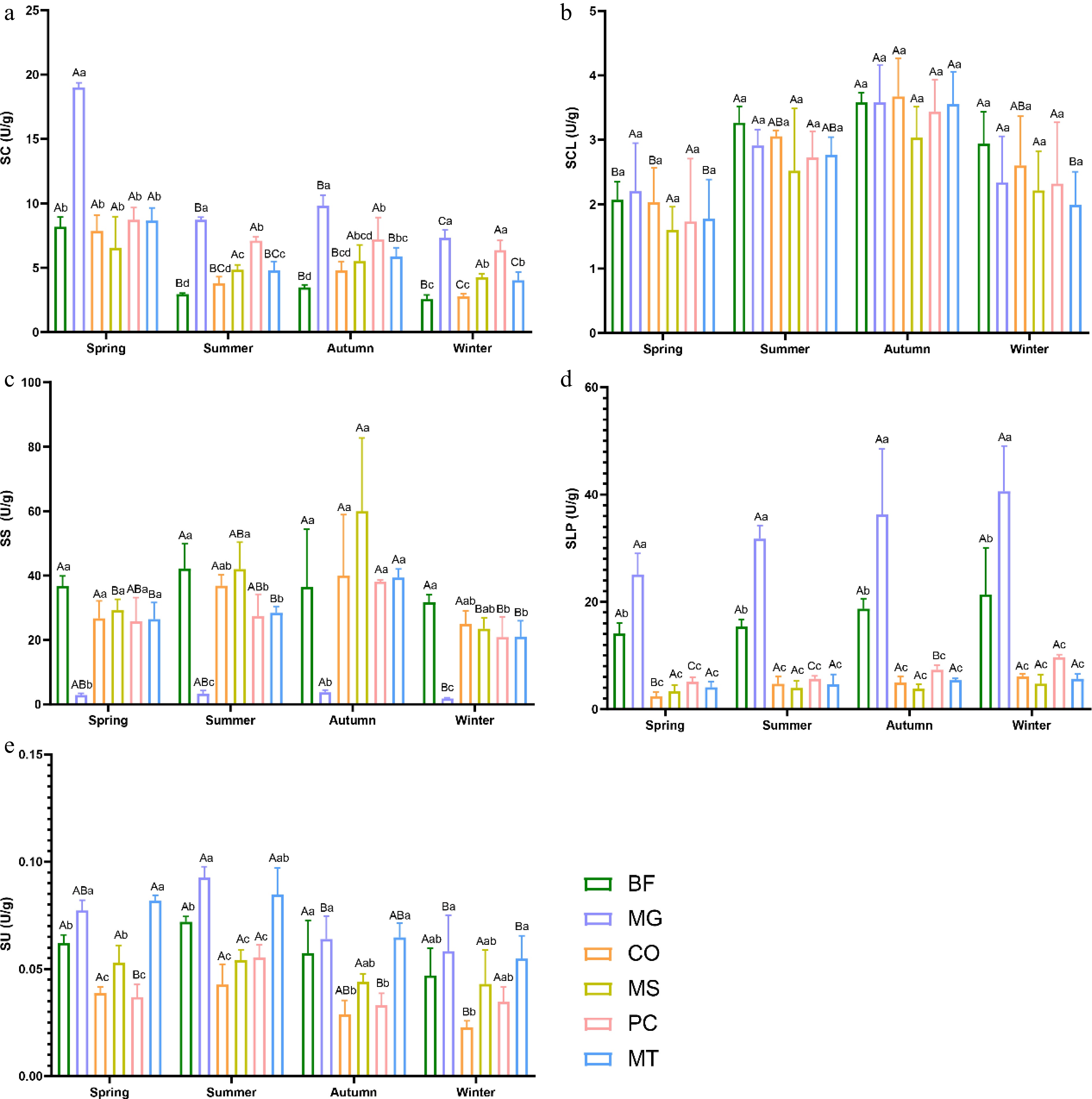

The multifactorial ANOVA revealed significant differences in soil enzyme activities among the different forest stands, and these activities were also significantly affected by seasons. The MG forest stand exhibited higher SC, SCL, and SLP activities, whereas the MS forest stand stood out in terms of SS activity. Across all forest stands and seasons, SU activity remained the lowest (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Seasonal variations in soil enzyme activity in six forest types. (a) Catalase (SC); (b) cellulase (SCL); (c) sucrase (SS); (d) alkaline phosphatase (SLP); (e) urease (SU). The six forest types are the same as in Fig. 1. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences among different forest types within the same season (p < 0.05); uppercase letters indicate significant differences among different seasons within the same forest type (p < 0.05).

The SC activity in all six forest stands reached its maximum in spring, with the MG forest stand showing markedly higher values than the other stands. Furthermore, the MG forest stand maintained the highest SC activity across all four seasons (Fig. 2a). In summer, except for the MG and CO forest stands, the SC activity decreased in all other stands. The SCL activity in all six forest stands peaked in autumn, with generally consistent levels among the five stands except MS. Overall, SCL activity in all stands showed an increasing trend from spring to autumn, followed by a decline from autumn to winter (Fig. 2b). Except for the BF and MG forest stands, SS activity in the other four stands reached its highest level in autumn. The MG forest stand consistently exhibited the lowest SS activity across all four seasons, whereas the BF stand showed relatively higher values in spring, summer, and winter. In autumn, however, the MS forest stand displayed the highest SS activity. In addition, SS activity in the PC and MT forest stands remained relatively stable across the seasons (Fig. 2c). Regardless of the season, SLP activity in the BF and MG forest stands was significantly higher than that in the other four forest stands, with MG ranking the highest and BF second. Moreover, both stands exhibited an overall increasing trend in SLP activity from spring to winter (Fig. 2d). SU activity across all six forest stands peaked in summer. For four stands, excluding MS and PC, SU activity increased from spring to summer and then declined from summer to winter (Fig. 2e).

Microbial biomass carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus

-

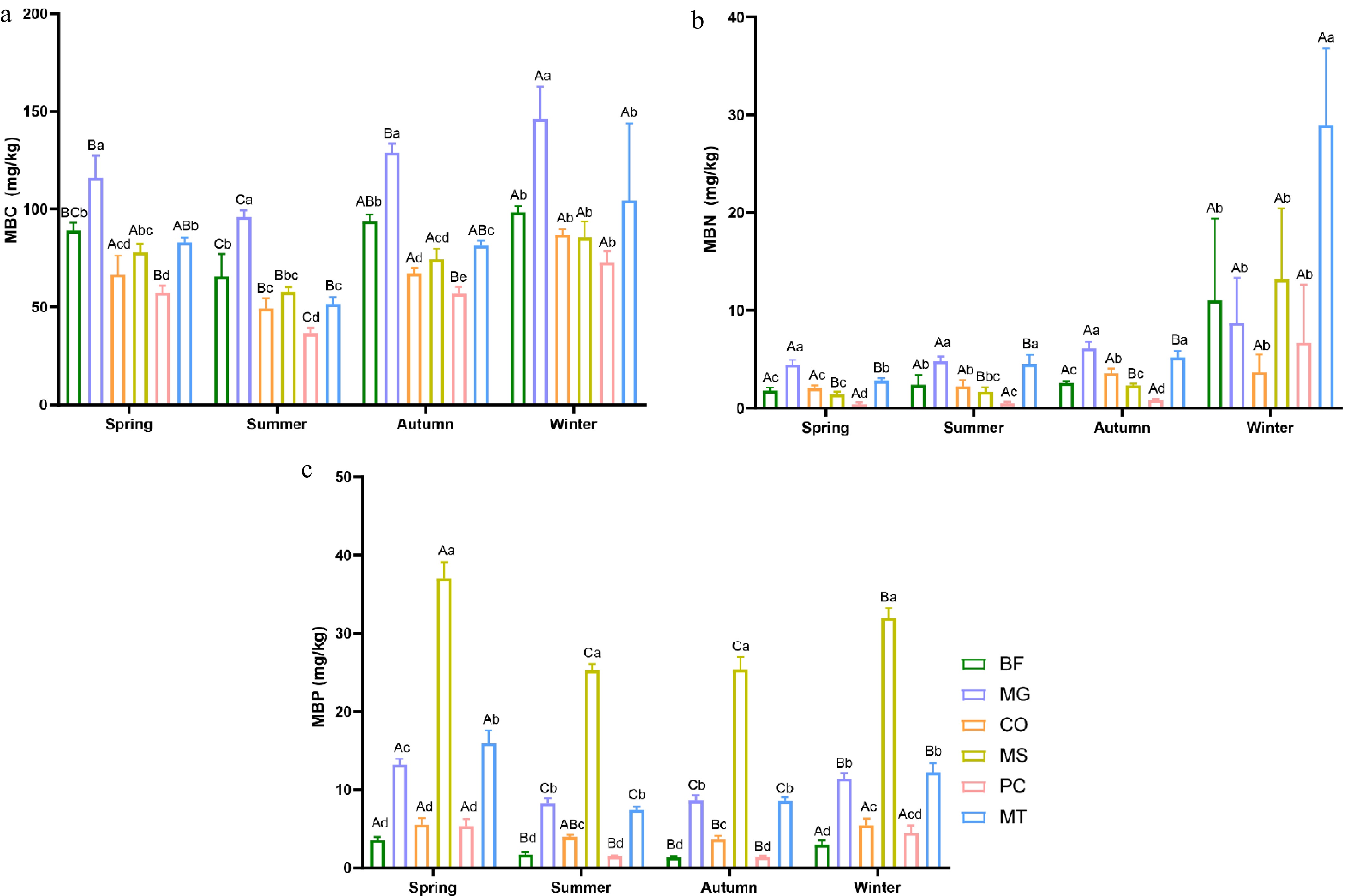

The analysis of soil MBC, MBN, and MBP revealed that seasonal variation exerts differential effects on these parameters. Overall, the transition from autumn to winter was characterized by notable increases in MBC, MBN, and MBP contents. Among these, MBC concentrations were significantly higher than those of MBN and MBP across all forest stands (Fig. 3). The MBC content in all six forest stands exhibited clear seasonal fluctuations, showing a decline from spring to summer and a subsequent increase from summer to winter, reaching its peak in winter. Notably, the MG forest stand consistently showed the highest MBC content across all four seasons, followed by BF, with PC exhibiting the lowest levels (Fig. 3a). Similarly, MBN content in all six forest stands peaked in winter. In contrast to MBC, MBN values showed minimal seasonal variation from spring to autumn, remaining below 10 across all stands. A significant increase occurred between autumn and winter, with the MT forest stand showing the most pronounced change, followed by MS (Fig. 3b). The MBP content in the MS forest stand was significantly higher than the other five forest stands across all four seasons, consistently exceeding 20 mg/kg, whereas the remaining stands exhibited values below 20 mg/kg. MBP content in all forest stands reached its maximum in spring and remained relatively stable during the summer and autumn (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3.

Seasonal variations in soil microbial biomass in six forest types. (a) Soil microbial biomass carbon (MBC); (b) soil microbial biomass nitrogen (MBN); (c) soil microbial biomass phosphorus (MBP). The six forest types are the same as those in Fig. 1. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences among different forest types within the same season (p < 0.05); uppercase letters indicate significant differences among different seasons within the same forest type (p < 0.05).

Organic carbon components and soil respiration

-

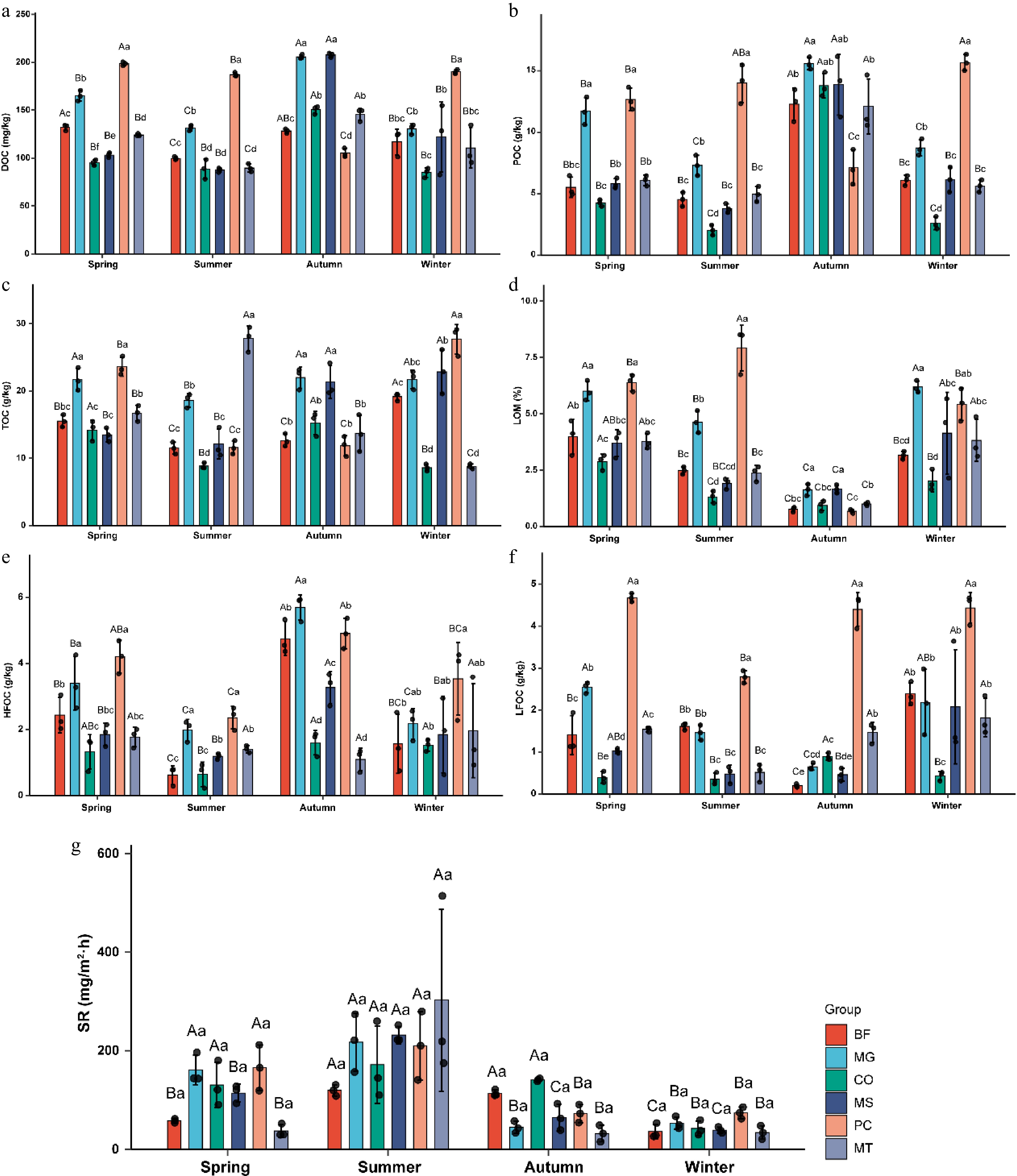

Six organic carbon components, DOC, POC, TC, LOM, HFOC, and LFOC, were analyzed. The results showed that DOC content was significantly higher than that of other carbon components across all seasons and forest stands (Fig. 4). DOC and POC exhibited similar variation patterns. In all stands except PC, both DOC and POC values reached their highest in autumn, decreased from spring to summer and from autumn to winter, and increased from summer to autumn. Notably, in the PC forest stand, DOC and POC contents ranked first in spring, summer, and winter (Fig. 4a, b). TC content reached its minimum in summer in five forest stands (BF, MG, CO, MS, and PC), whereas the MT forest stand recorded its lowest TC value in winter. Seasonal variation had a particularly pronounced effect on TC in MT, with considerable differences across all four seasons (Fig. 4c). LOM values were lowest in autumn across all forest stands. Except for PC, the LOM content in the other five stands decreased from spring to autumn and increased from autumn to winter (Fig. 4d). HFOC in the MT forest stand reached its minimum in autumn, whereas in the other five forest stands, HFOC peaked in autumn. Across all stands, HFOC showed a general trend of declining from spring to summer and from autumn to winter, with an increase from summer to autumn. Additionally, the CO and MT forest stands maintained HFOC values below 2 g/kg throughout the year (Fig. 4e). The LFOC content in the PC stand was significantly higher than in the other stands across all seasons and remained relatively stable in the spring, autumn, and winter. PC was the only stand with LFOC values exceeding 3, whereas CO was the only stand with values below 1 g/kg across all seasons. Furthermore, the LFOC content in BF was notably lower in autumn than in the other three seasons (Fig. 4f).

Figure 4.

Seasonal variations of carbon composition and soil respiration in six forest types. (a) Dissolved organic carbon (DOC); (b) particulate organic carbon (POC); (c) total carbon (TC); (d) labile organic matter (LOM); (e) heavy fraction organic carbon (HFOC); (f) light fraction organic carbon (LFOC); (g) soil respiration (SR). The six forest types are the same as in Fig. 1. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences among different forest types within the same season (p < 0.05); uppercase letters indicate significant differences among different seasons within the same forest type (p < 0.05).

Soil respiration was also significantly influenced by both season and forest stand type. Across all six forest stands, soil respiration peaked in summer, showing an overall upward trend from spring to summer (Fig. 4g). In the BF stand, respiration in autumn was slightly lower than in summer. In MG, respiration levels in autumn and winter were comparable and significantly lower than those in spring and summer. The CO stand followed the pattern summer > autumn > spring > winter, with the winter value being markedly lower than in other seasons. In MS, the order was summer > spring > autumn > winter. For PC, soil respiration was similar in autumn and winter, which had values significantly lower than those in spring and summer. In MT, the respiration values in spring, autumn, and winter were all below 100, but reached nearly 300 in summer, which was significantly higher than in the other three seasons. The average values of soil respiration in the six forest stands were 111.16, 208.91, 78.18, and 46.49 mg/m2·h in spring, summer, autumn, and winter, respectively, showing an overall trend of first increasing and then decreasing.

Random Forest analysis

-

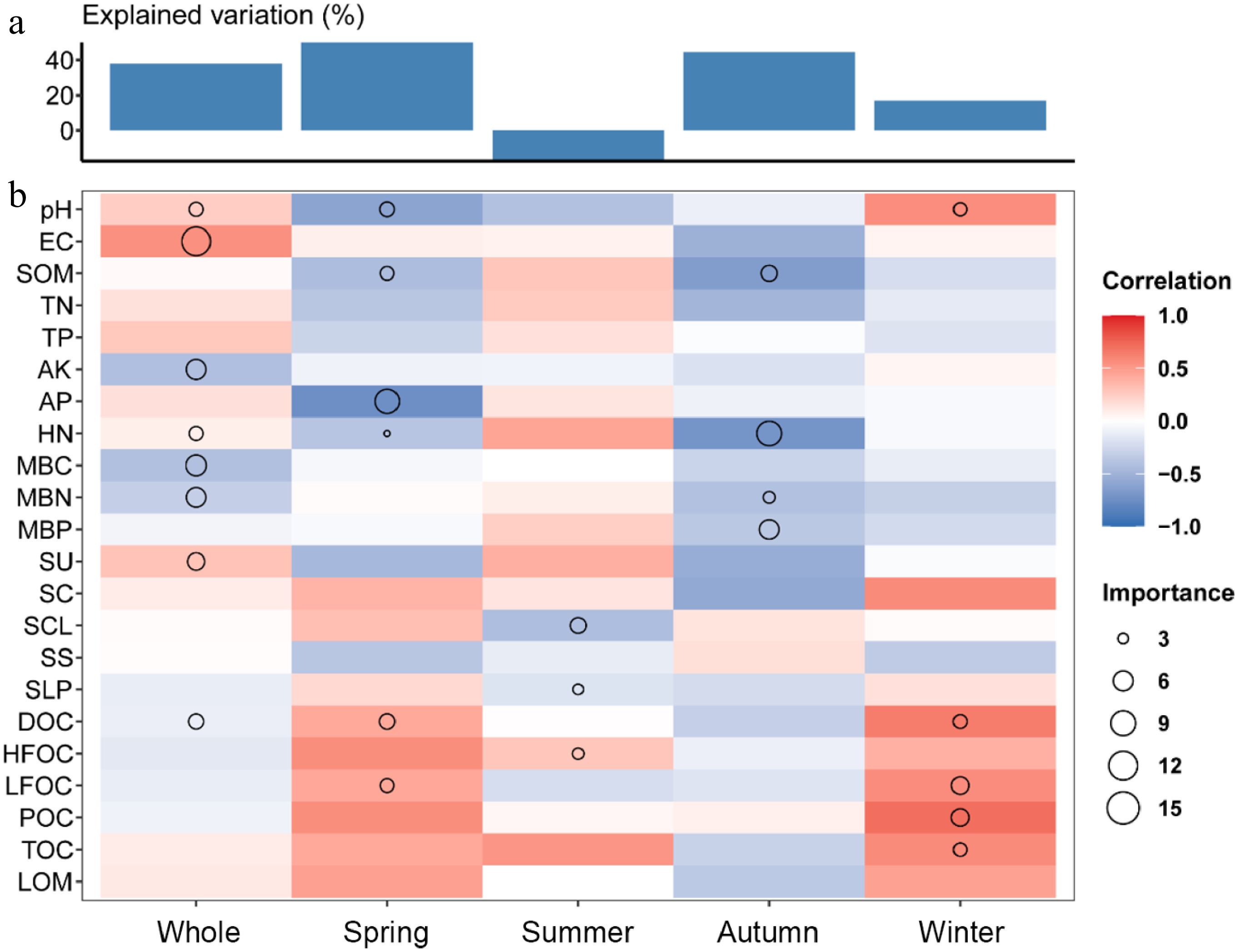

We constructed a Random Forest model using all six forest stands as a combined dataset to identify the primary environmental factors influencing soil respiration. The results showed that the total explanatory variable was 37.85%, with the explanatory variable being 49.86% in spring, −17.3% in summer, 44.57% in autumn, and 17.04% in winter (Fig. 5a). Overall, pH, EC, AK, HN, MBC, MBN, SU, and DOC exhibited high importance in determining soil respiration. Among these, pH, EC, HN, and SU were positively correlated with soil respiration, whereas AK, MBC, MBN, and DOC showed negative correlations. Seasonal differences were also evident. In spring, AP and LFOC displayed relatively high importance; in summer, only SCL, SLP, and HFOC showed a significant influence; in autumn, SOM, HN, MBN, and MBP had relatively high importance and were negatively correlated with soil respiration. However, in winter, the indicators with high importance, pH, DOC, LFOC, POC, and TC, were all positively correlated with soil respiration (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Random Forest analysis of explanatory variables for soil respiration. (a) Explanation and analysis of environmental factors. (b) Importance scores and correlation coefficients of each environmental factor to soil respiration.

PLSPM analysis

-

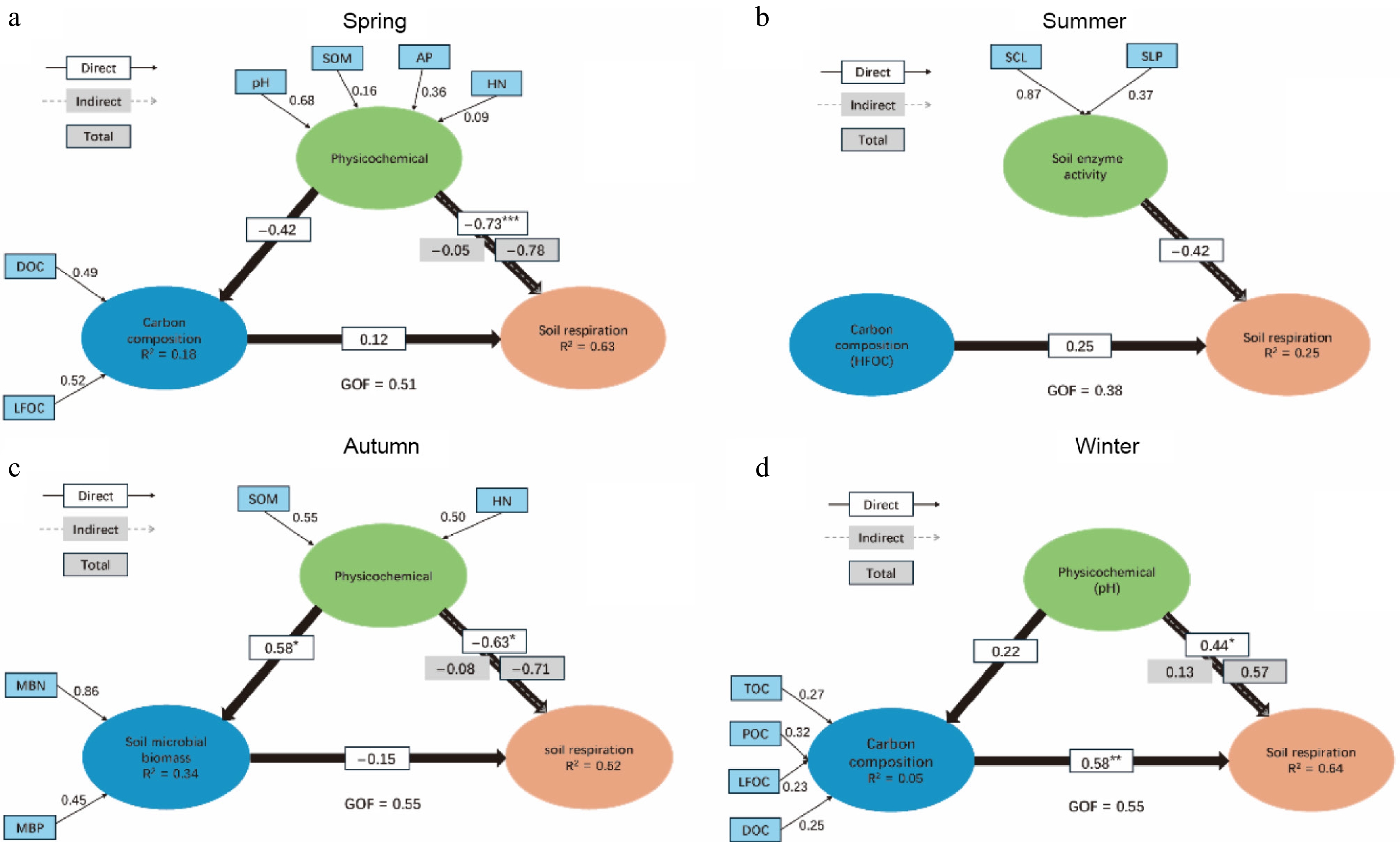

Building upon the Random Forest results, a PLSPM was developed to reveal the relationships among the soil's physicochemical properties, enzyme activities, microbial biomass, carbon fractions, and soil respiration. In spring, the soil's physicochemical properties exhibited a direct negative effect on soil respiration, contrasting with the positive role of carbon fractions (Fig. 6a). In summer, neither soil enzyme activities nor soil carbon fractions showed a noticeable influence on soil respiration (Fig. 6b). In autumn, the soil's physicochemical properties significantly promoted microbial biomass but negatively affected soil respiration, whereas microbial biomass itself had only a limited impact on respiration (Fig. 6c). In winter, the soil's physicochemical properties significantly enhanced soil respiration, and carbon fractions exerted an even stronger positive effect (Fig. 6d).

Figure 6.

PLSPM analysis of the effects of different factors on soil respiration in various seasons: (a) Spring; (b) summer; (c) autumn; (d) winter. The numbers on the arrows represent path coefficients. "Direct" stands for direct effects, "Indirect" denotes indirect effects, and "Total" represents total effects. Significance levels: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * and p < 0.05. The goodness of fit (GOF) index was used to assess model performance.

-

This study demonstrates that soil respiration exhibits pronounced seasonal fluctuations. Similar seasonal patterns have also been reported by Tomar and Baishya, who observed that soil respiration peaks in spring and winter[37]. However, our results differ in that, across all six different forest types, the highest soil respiration consistently occurred in summer, with a clear increasing trend from spring to summer. Numerous studies worldwide agree that soil enzyme activity, MBC, and organic carbon content are the primary regulators of soil respiration[37−40].

Seasonal dynamics also exert significant influences on the soil's physicochemical properties and enzyme activities. Our findings showed that most physicochemical parameters peaked during summer and autumn, likely reflecting the warm and humid conditions characteristic of these seasons. Existing research has pointed out that such environments promote microbial physiological activity[41], which subsequently alters the soil's physicochemical properties. Prior research has suggested that elevated soil pH strongly stimulates microbial respiration and the solubility of organic carbon[42]. Consistently, it was observed in our study that elevated soil respiration intensity often coincides with increased pH. Although both our results and those of Lai et al. indicated a strong relationship between EC and soil respiration, our analysis revealed a positive correlation, contrasting with their findings[43]. Nitrogen, a crucial component of amino acids, proteins, and coenzymes, enhances the activity of soil microorganisms and enzymes by promoting the accumulation of carbon and nitrogen, thereby affecting soil respiration[44]. SOM, a fundamental indicator of the soil's physicochemical status, largely determines the soil’s structural and biological characteristics. Previous studies have identified SOM as a key factor mediating the responses of soil respiration to warming[45]. In our study, SOM was likewise confirmed as an important factor affecting soil respiration. In particular, the SOM content in the MG and MT forest stands exhibited significantly higher SOM contents than the other four forest types, suggesting that Metasequoia and mixed broadleaf forests possess superior organic matter storage capacity. As the principal reservoir of SOC, SOM has a direct impact on soil respiration. The decomposition rate of SOM and microbial activity together determine the intensity of soil respiration[6]. Generally, soils with a higher SOM content sustain higher respiration rates, as they provide more abundant carbon sources for microbial metabolism.

Soil enzymes, as core mediators of the soil environment, exert a decisive influence on the decomposition of organic matter, nutrient cycling, and energy transfer within the soil environment[13]. Research by Baldrian et al. also confirmed the presence of seasonal variation in soil enzyme activities[46]. However, soil enzyme activity is influenced by a combination of factors[47−49] and thus exhibits distinct seasonal patterns, depending on the enzyme type. In this study, the activities of SCL, SS, and SLP reached their highest levels in autumn, whereas SC peaked in spring, and SU in summer. SC, as an important redox enzyme, mitigates the toxic effects of hydrogen peroxide in the soil. SU enzyme activity is closely related to plant roots, soil nitrogen, and pH[50], and it directly participates in the transformation of nitrogen-containing organic compounds. Furthermore, studies have shown that there is a close relationship between SS enzyme activity and the mineralization rate of SOC[51], which constitutes a key component of soil respiration[52]. This finding suggests that SS activity influences soil respiration indirectly by modulating the mineralization of SOC.

This study also examined the characteristics of seasonal variation in the soil's microbial biomass and carbon components across six forest stands. Significant differences in microbial biomass were observed among the forest types across seasons, largely attributed to the complex interactions among the soil's biochemical processes[53,54]. Existing research generally classifies the seasonal dynamics of soil microbial biomass into three types: High in summer and low in winter; high in winter and low in summer; and fluctuating with alternating wet and dry seasons. Although numerous studies have reported a positive correlation between MBC and soil respiration[55], the Random Forest analysis in this study revealed a negative relationship between the two, in contrast to previous findings. We hypothesize that this discrepancy may arise from the specific environmental conditions and forest stand characteristics of the study area. High summer temperatures may inhibit certain microbial activities; thus, although MBC levels are relatively low in summer, the accelerated decomposition rate of SOM and enhanced plant root respiration collectively result in elevated soil respiration rates. Conversely, in winter, despite higher MBC levels, low temperatures significantly suppress microbial metabolic activity, leading to lower soil respiration rates. This seasonal inversion may therefore explain the observed negative correlation between MBC and soil respiration.

In addition, differences in the litter input characteristics and decomposition efficiency among forest stands may also contribute to the observed variations in soil respiration. For instance, although the MG forest exhibited relatively high MBC content, its litter decomposes slowly, providing less readily available organic carbon for microbial utilization. In contrast, MT experiences rapid litter decomposition during summer, releasing substantial amounts of labile carbon. This process, despite the lower MBC levels, promotes elevated soil respiration through accelerated carbon turnover[56]. This provides offers new insights into the dynamic relationship between microbial biomass and soil respiration under varying environmental conditions. Future research should incorporate longer-term observational data and microbial community structure analyses to verify the stability and reveal the mechanisms underlying this negative correlation.

The content and composition of SOC form the foundation of soil carbon cycle studies, directly influencing microbial and root activity[57,58]. Microorganisms preferentially utilize labile carbon components, which helps to enhance respiration[59,60]. Unstable carbon fractions such as MBC and DOC accelerate soil respiration by increasing the organic carbon turnover rates[60,61]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that within an optimal range, rising temperatures enhance enzyme and microbial activity, consequently increasing the soil respiration rates[62,63]. Similarly, appropriate soil moisture supplies the water necessary for microbial metabolism, promotes substrate dissolution and diffusion, and thus enhances the intensity of soil respiration[64]. However, other studies have reported a negative correlation between soil moisture and soil respiration[65], suggesting that excessive water content may limit gas diffusion and oxygen availability. Therefore, future research should incorporate simultaneous, long-term monitoring of temperature and soil moisture, in addition to the original indicators, to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of the environmental drivers of soil respiration.

-

This study revealed distinct seasonal variation characteristics of soil respiration in the forests of Zhuyu Bay, with soil respiration intensity in summer being significantly higher than in other seasons and reaching the annual peak. Overall, soil respiration across the four seasons is strongly regulated by the soil's physicochemical properties, among which, pH, EC, AK, and HN play a crucial role. Meanwhile, MBC, MBN, SU, and DOC are key biotic factors driving fluctuations in soil respiration. The aforementioned abiotic and biotic factors jointly determine the intensity and temporal dynamic patterns of soil respiration through synergistic interactions. The results of this study clarify the fundamental characteristics and driving mechanisms of soil respiration in the forests of Zhuyu Bay, providing theoretical support for an in-depth analysis of carbon cycling processes in forest ecosystems and offering an important scientific basis for formulating forest management and soil conservation strategies aimed at maintaining ecosystem stability and mitigating carbon emissions. However, this study still has several limitations. The study only set a 1-year observation period, making it difficult to reflect the long-term patterns of dynamic variation of soil respiration; additionally, the lack of an analysis of the microbial community structure limits a thorough interpretation of the interaction mechanisms between microorganisms and soil respiration. Future studies should incorporate more environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and anthropogenic disturbances to more comprehensively reveal the regulatory mechanisms of soil respiration.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conception and design of the research, revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Xing W, Yuan Y; acquisition of data: Li L; analysis and interpretation of data: Zhou R; statistical analysis: He D; drafting the manuscript: Xing W. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Xing W, Li L, Zhou R, He D, Yuan Y. 2026. Seasonal variations of soil respiration in Yangzhou's urban forests. Forestry Research Advances 1: e002 doi: 10.48130/fra-0025-0002

Seasonal variations of soil respiration in Yangzhou's urban forests

- Received: 16 September 2025

- Revised: 04 December 2025

- Accepted: 09 December 2025

- Published online: 20 January 2026

Abstract: Soil respiration is an indispensable component of soil ecosystems and plays a crucial role in the soil carbon cycle. Understanding the factors that influence soil respiration is of great significance for forestry management. This study monitored six forest types in the Zhuyu Bay Forest of Yangzhou City, Jiangsu Province, China, to investigate the seasonal dynamics of soil respiration across different forest patterns. The key factors influencing soil respiration were identified using a combination of the Random Forest model and the partial least squares path model. The results showed that soil respiration exhibits obvious seasonal variations, as the average soil respiration of the six forest stands peaks at 208.91 mg/m2·h in summer and reaches the lowest point at 46.49 mg/m2·h in winter. Soil respiration primarily is regulated by physicochemical properties. In addition, microbial biomass carbon, microbial biomass nitrogen, sucrase, and dissolved organic carbon were identified as important factors affecting soil respiration, with importance values of 8.13, 7.49, 5.89, and 4.86, respectively. These findings contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the complex mechanisms underlying the soil carbon cycle and provide a scientific basis for optimizing forest management practices, thus enhancing carbon sequestration and promoting the sustainable development of forest ecosystems.

-

Key words:

- Carbon composition /

- Enzyme activity /

- Microbial biomass /

- Physicochemical properties /

- Soil respiration