-

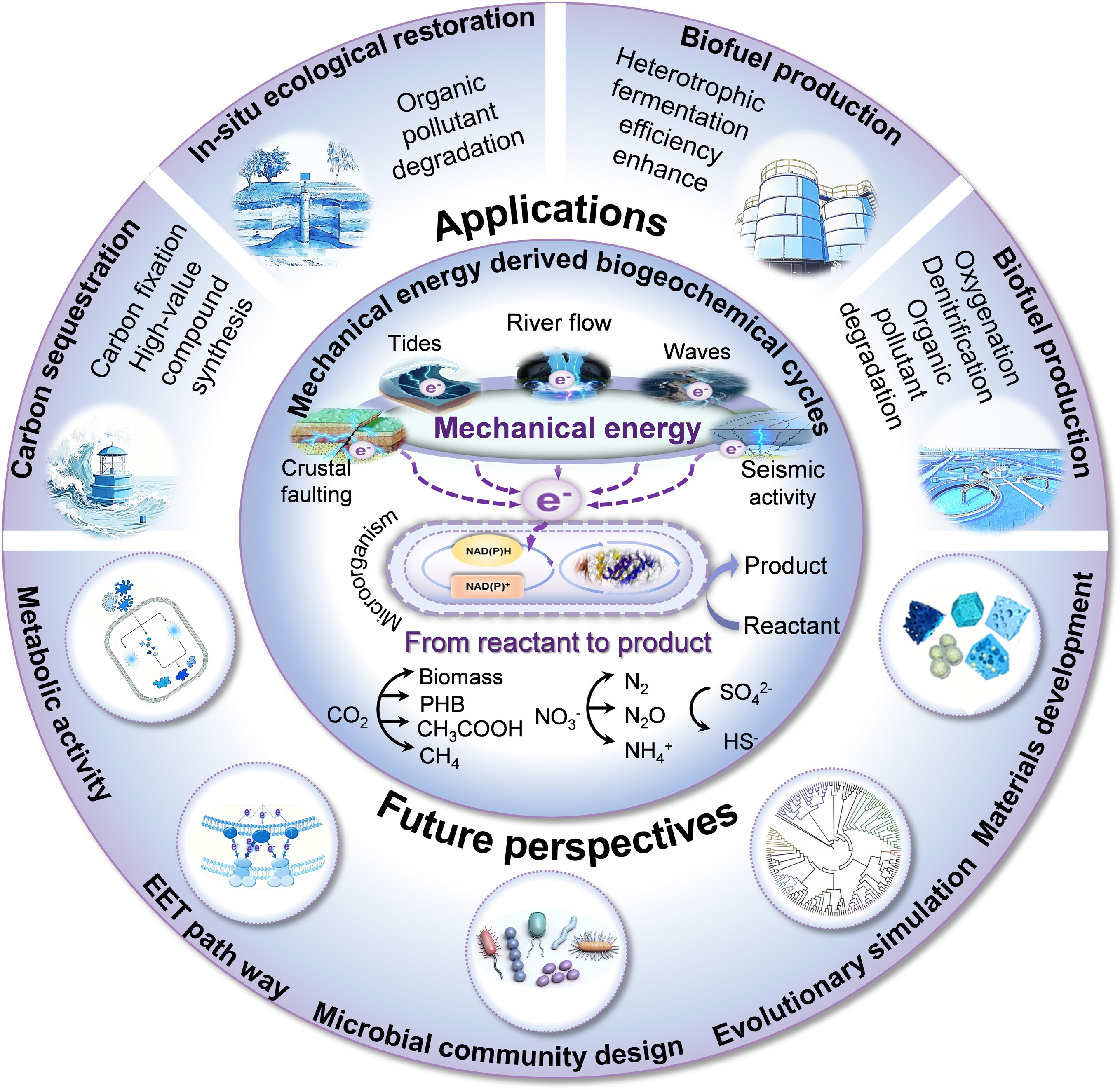

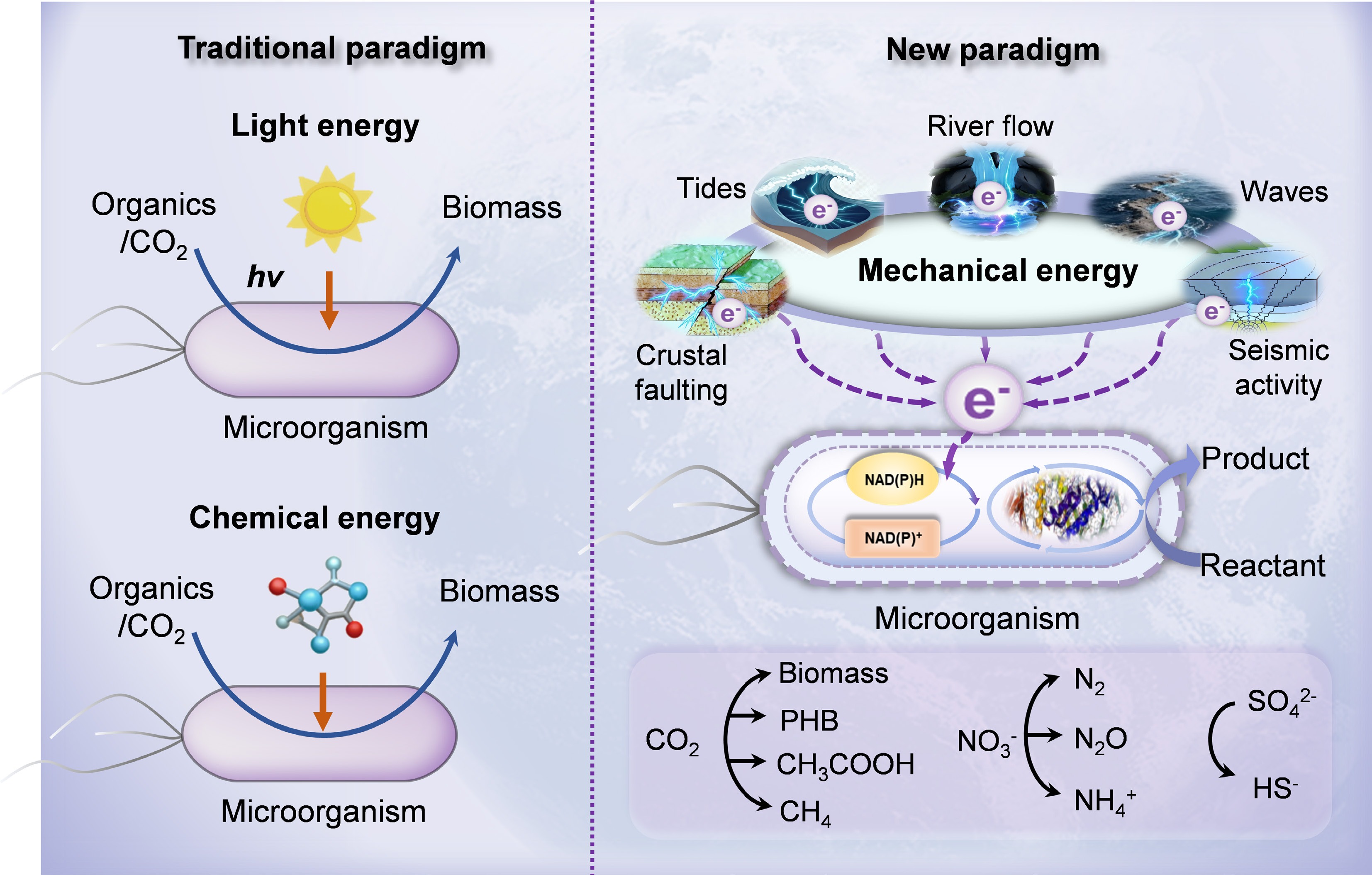

The foundational work of Sergei Winogradsky and Martinus Beijerinck established the theoretical basis for viewing biogeochemical cycles as processes driven by microbial energy acquisition[1]. For a long time, microorganisms harness energy either from light (phototrophy) or redox chemical potential gradients (chemotrophy), which are two classical energy paradigms[2,3] (Fig. 1). These two primary energy transduction pathways underpin the global-scale cycling of elements critical for life processes, including carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur[4,5]. However, while the traditional phototrophy-chemotrophy dichotomy provides a fundamental explanatory framework, it struggles to offer a comprehensive understanding of the full mechanisms underlying biogeochemical cycling. For instance, it fails to adequately explain how microbial communities maintain considerable biomass and metabolic activity within the dark, energy-impoverished deep biosphere[6,7]. This conceptual gap suggests the need to further examine the potential role of other widely available energy sources in driving biogeochemical cycles.

Figure 1.

Mechanical energy promotes the evolution of the conceptual paradigm for understanding biogeochemical cycles.

Mechanical forces are ubiquitous components of the Earth's dynamic system, which originate from persistent environmental processes ranging from surface actions (river flow and ocean waves) to internal forces (seismic activity and crustal faulting) (Fig. 1)[8]. Although geological and physical impacts have been relatively well studied, their potential to drive biogeochemical reactions has not yet been fully recognized[9,10]. Recent research has shown that microorganisms sense and respond to the various mechanical forces various mechanical cues, primarily generated by fluid flow and pressure, as well as by surface contact[11]. Coupling between these physical forces and biochemical reactions is potentially achieved through the piezoelectric effect, a phenomenon in which certain non-centrosymmetric materials generate an electric charge in response to an applied mechanical force[12−14]. However, early investigations have predominantly focused on the disruptive effects of mechanical forces on microbial cells, whereas their potential supportive role in microbial survival and growth through energy conversion has only recently received attention relatively recently[15]. Recent findings indicate that microorganisms can directly use the electricity generated from the conversion of mechanical energy, thereby establishing a novel energy transduction pathway from mechanical force to electrons, and ultimately to biochemical energy (Figs 1 and 2)[16−19]. In addition to serving as an alternative energy source, mechanistically driven biogeochemical processes may represent a hidden architecture throughout the Earth's environmental and evolutionary history. A plausible example is the pre-Great Oxidation Event terrestrial setting, where the fluvial transport and abrasion of quartz-rich rocks generated reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydrogen peroxide, via mechanochemical reactions[12,13]. These processes create transient oxygenated niches that could exert selective pressure on early microbial communities, favoring the emergence of antioxidant strategies prior to the global increase in oxygen levels. Such local ROS exposure likely served as a critical evolutionary training ground, priming life for the pervasive oxidative stress encountered during the Great Oxidation Event. In a complementary manner, crustal faulting and the associated rock deformation facilitates fluid migration and fracture networks that may sustain microbial ecosystems in deep sub-surface environments[20]. These systems potentially support metabolic processes, such as sulfate reduction or hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis, which not only allows life to persist in isolation from the surface but also modify the geochemistry of deep fluids, for instance, through mineral dissolution or carbon cycling[20]. Such biogeochemical alterations may subsequently affect diagenetic mineralization, rock rheology, and pore pressure distribution, thereby creating feedback that influences broader tectonic behavior over geological timescales. Together, these findings highlight the need to construct a mechanobiogeochemical framework to deepen the understanding of the complex interconnections between the Earth's internal dynamics, surface environments, and biological evolution[11,21].

This review proposes a conceptual framework for 'mechano-biogeochemistry', an interdisciplinary field that examines how mechanical forces drive biogeochemical cycles, which are driven by mechanical forces converted into electrons and used by microorganisms. This framework suggests that ubiquitous mechanical energy can serve as an alternative driver of the global biogeochemical cycle. This energy, derived from geophysical processes, is converted into bioavailable electrons via the piezoelectric effect in non-centrosymmetric minerals or synthetic materials, thereby establishing a novel transduction chain: mechanical force → electron → biochemical energy. Recent research has demonstrated that both natural (e.g., quartz and tourmaline), and synthetic piezoelectric materials (e.g., BaTiO3) can form biohybrid systems with electroactive microorganisms[11,16−19]. When subjected to mechanical forces, these materials generate electric charges that microorganisms harness to drive metabolic processes, including the fixation of CO2 into biomass and bioplastics[17,18], nitrate reduction to nitrogen gas or ammonium[16,19], and sulfate reduction[20]. Mechano-biogeochemistry is expected to expand the understanding of microbial survival strategies in energy-poor environments, such as energy sources for early life in the dark world[22]. It is important to clarify that 'mechano-biogeochemistry' does not seek to replace the traditional paradigms of phototrophic and chemotrophic theories, but rather to complement them, particularly in 'marginal environments' where conventional energy sources are limited. Currently, research in this field is predominantly focused on laboratory-scale model systems, with a focus on validating the fundamental feasibility[16−18].

This review systematically elaborates on the mechano-biogeochemical framework by synthesizing recent advances to answer the following key questions: (1) What are the environmental sources and material bases for piezoelectric energy transduction? (2) What are the molecular mechanisms underlying the microbial uptake and utilization of piezoelectrically generated electrons? (3) How do these mechano-driven processes influence key biogeochemical cycles? and (4) What are the geobiological implications and potential technological applications of this paradigm? By integrating interdisciplinary perspectives, this review aims to establish mechano-biogeochemistry as a complementary framework for understanding the Earth's element cycles.

-

The power of mechano-biogeochemistry lies in the constant and widespread input of mechanical energy from geophysical and anthropogenic sources (Fig. 1). Among these, ocean waves impart substantial energy on coastlines, with the highest power densities of approximately 2–3 kW·m−2, which has considerable potential but is highly intermittent[23]. River flow provides a continuous kinetic energy density of approximately 0.12 kW·m−2. Despite its low energy density, it is continuously available over vast areas, and its shear force directly influences sediment transport and mineral abrasion[24]. Particularly noteworthy are tidal energy and fluid flow within geothermal vent systems, which rank among the most persistent and energetically substantial mechanical energy sources in deep-sea and subsurface environments. In certain straits, tidal currents can attain power densities of up to 10 kW·m−2 and exert shear forces sufficient to deform submerged sediments[9,10]. These geochemical processes might drive piezoelectricity in minerals, such as quartz, generate oxidants (H2O2), or directly provide electrons to microbes attached to sand grains, thereby influencing carbon fixation and nitrogen cycling[12].

Seismic activity and crustal faulting are high-energy (approximately 13 MJ·m−2), episodic sources of mechanical energy[25]. Wu et al.[20] demonstrated that faults in deep sub-surfaces drive biological redox cycling. Their findings suggested that tectonic events may generate episodic energy pulses, thereby enabling their use by deep biosphere communities. Tectonic forces and faulting in the deep biosphere potentially drives metabolic processes, such as sulfate reduction and methanogenesis via piezoelectric and triboelectric effects[20]. The mechanical energy from raindrop impacts, with its instantaneous power reaching kilowatts per square meter, but a very low average flux, could play a role in the local microenvironmental chemistry. Anthropogenic activity is another significant factor. Ultrasonic irradiation is a laboratory staple for studying piezocatalysis, but its principles also apply to industrial processes and environmental remediation technologies[16,26]. Natural sources (e.g., seismic P/S waves, and underwater sound fields) and anthropogenic ultrasound can remotely transmit mechanical energy, potentially activating piezoelectric catalysts in water columns or sediments. Hydraulic kinetic energy from water flow in engineered systems has been demonstrated to have the potential to drive denitrification in wastewater treatment[16,19]. Even subtle mechanical energy from soil-air water exchange and root growth can generate measurable electrical fields[27−29]. Collectively, these diverse mechanical energy sources, ranging from the macroscopic force of tectonics to the microscopic energy of root growth forms a pervasive energetic continuum that bridges abiotic geophysical processes with the metabolic forces of the biosphere via mechano-biogeochemical pathways.

Fundamental principles of the piezoelectric effect

-

The piezoelectric effect, first demonstrated by Jacques and Pierre Curie in 1880, is a reversible phenomenon in which a mechanical force induces electrical polarization in certain crystalline materials lacking a center of symmetry[30]. The direct piezoelectric effect refers to the generation of electrical polarization within a crystal under a mechanical force, which produces a dipole moment and induces positive and negative charges on the crystal surfaces. This process establishes a transient yet substantial built-in electric field, the strength of which is determined by both the intrinsic piezoelectric coefficient of the material and external mechanical force[31]. Conversely, the inverse piezoelectric effect describes the material deformation in response to an external electrical field. This property is widely used in devices, such as sensors and actuators. Biogeochemical applications primarily focus on the conversion of mechanical energy into chemical energy, forming the foundation for mechano-biogeochemical energy transduction[14,26].

The efficiencies of charge generation and separation are central to the practical utility of the piezoelectric effect. Under ideal conditions, the mechanical force separates the positive and negative charge centers in the crystal lattice, thereby generating electron-hole (e−−h+) pairs[32]. The dynamic behavior of these charge carriers determines the catalytic outcome; if they recombine, energy is dissipated as heat. However, if electrons and holes are rapidly scavenged by appropriate electron acceptors and donors rapidly scavenge electrons and holes, respectively, they can drive redox reactions at the material surface[14,33]. The physical processes of charge generation, separation, and interfacial transfer constitute the core mechanism of piezocatalysis. The electron is then harnessed by electroactive microorganisms to drive metabolism. Thus, in contrast to tribochemistry, which focuses on interfacial reactions between solids, and mechanochemistry, which addresses direct force-induced chemical or microstructural transformations[34], the present paradigm is distinguished by a two-step energy transduction mechanism. The core does not involve direct mechanical activation of chemical bonds, but rather the conversion of mechanical force into an electron flow via piezoelectricity, followed by microbial electrophysiological utilization of these electrons to drive biochemistry.

Ubiquitous piezoelectric materials in natural environments

-

The Earth's crust serves as an extensive reservoir of piezoelectric minerals and provides a substantial material basis for this energy-harvesting mechanism. Among the various piezoelectric minerals, quartz (SiO2) holds a predominant position owing to its high natural abundance and significant environmental relevance[35]. Its widespread distribution within the continental crust, particularly in granites, sandstones, and clastic sediments, plays a critical role in environmental piezoelectric processes. Numerous settings, from mountain ranges to deep sandstone aquifers, can potentially become sites of piezoelectric activity when subjected to directed stress under conditions of low electrical conductivity. The durability and prevalence across the three major rock categories indicate that geological processes involving quartz deformation, such as tectonic grinding and riverbed abrasion, can generate piezoelectric activity[36]. Even under moderate rock friction, the local stress intensity at actual contact interfaces can reach the gigapascal range[37], providing deformational energy to the potential energy surface[38]. The resulting piezoelectric process generates lattice defects and surface-bound radicals via a mechanism analogous to gamma irradiation and thermal treatment[39]. These highly reactive surface-bound radicals then interact with the surrounding aqueous medium, driving the production of hydrogen (H2)[24], molecular oxygen (O2), and ROS[13,20]. The redox gradients established via these piezoelectric processes may substantially contribute to sustaining the deep biosphere[20]. In addition to quartz, several other naturally occurring minerals exhibit piezoelectric properties. Tourmaline, found in granitic pegmatites and metamorphic rocks, exhibits unique spontaneous polarization and piezoelectric properties[14]. This complex borosilicate mineral exhibits notable piezoelectric and pyroelectric properties, and experiments have confirmed its ability to effectively decompose organic dyes under vibrational excitation[14]. Sphalerite (ZnS) and gallium phosphate (GaPO4), which are common minerals in hydrothermal ore deposits, may facilitate localized redox processes in confined, reducing subsurface environments owing to their properties[28,29]. Clay minerals subjected to nanoconfinement within geological faults exhibit ion- and electron-transport properties, thereby promoting redox reactions[40]. The diversity of piezoelectric minerals suggests that the piezoelectric phenomenon is not exceptional but rather a widespread natural occurrence in geological contexts.

Specific biological structures exhibit piezoelectric characteristics. Bone (due to collagen), wood (due to cellulose), and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) in biofilms can generate electrical potential under mechanical force[21,28]. Chitin, a major component of fungal cell walls and arthropod exoskeletons, also exhibits excellent piezoelectric properties, suggesting that piezoelectricity may have broad biophysical significance across the eukaryotic domain as well[41]. Moreover, the piezoelectricity of EPS may not merely represent a passive trait but could also function as an active regulatory mechanism within microbial communities[8]. The micro-electric fields generated by EPS can influence cell-cell communication and spatial organization during biofilm development[11], and may even act as a primitive mechanism for sensing environmental mechanical forces. Therefore, such biologically derived piezoelectricity may contribute to the coupling of mechanical and redox processes at microbe-mineral interfaces.

Engineering piezoelectric materials for enhanced biogeochemical applications

-

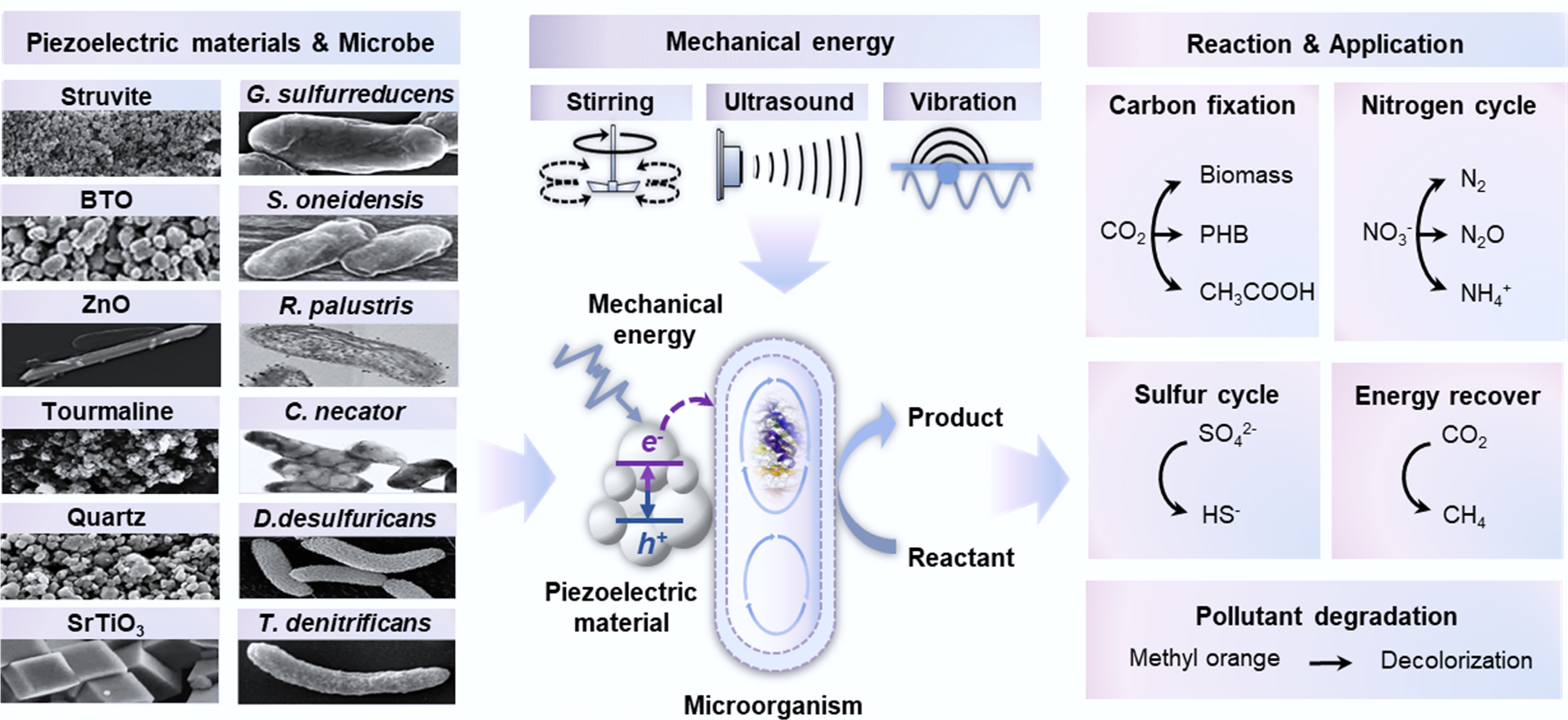

Although naturally occurring piezoelectric minerals, such as quartz, are geologically abundant, their relatively low piezoelectric coefficients and dielectric constants restrict their ability to efficiently convert mechanical energy into electrochemical potential[42]. To address this constraint, materials science researchers have developed a range of high-performance synthetic piezoelectric nanomaterials. Among these, barium titanate (BaTiO3), zinc oxide (ZnO), and lead zirconate titanate (PZT) have been the most extensively studied materials, exhibiting piezoelectric coefficients up to two orders of magnitude higher than those of natural minerals (Supplementary Fig. S1)[43]. Fabricating these materials into specific morphologies, such as nanoparticles, nanowires, or porous frameworks, effectively increases their active surface area and enhances their strain-responsive characteristics[17,18]. Current research efforts are increasingly focused on improving both the biocompatibility of these materials and the efficiency of the interfacial electron transfer.

Surface functionalization with hydrophilic groups or conductive polymers promotes microbial colonization and facilitates direct electron transfer between the material and microorganisms[44]. The overarching objective of these investigations is to construct robust 'biopiezocatalytic' systems that efficiently couple mechanical energy inputs with microbial metabolic processes, thereby expanding potential applications from CO2 fixation to pollutant degradation (Fig. 2)[17]. In addition to pursuing high piezoelectric coefficients, material designs for biogeochemical applications should also satisfy a series of 'environmental compatibility' criteria[45]. These considerations include:

(1) Band structure alignment: The conduction/valence band positions of the material must align with the redox potentials of the target microbial processes. For example, CO2 reduction requires a sufficiently negative conduction band energy level, whereas pollutant degradation requires a sufficiently positive valence band energy level. Precise tuning of the electronic structure can be achieved through elemental doping (e.g., N-doped BaTiO3), or constructing heterojunctions (e.g., ZnO/g-C3N4)[46].

(2) Chemical stability: Long-term stability under specific environmental conditions (e.g., seawater and acidic pore water) is crucial. Although ZnO tends to dissolve in acidic environments, BaTiO3 and PZT generally exhibit broader pH stability. However, the potential leaching of lead from PZT poses substantial environmental and health risks, affecting everything from soil microbial communities to wildlife populations and disrupting entire ecosystems[35−37]. Therefore, lead-free piezoelectric alternatives must be considered for sustainable applications. Materials, such as barium titanate (BaTiO3), potassium sodium niobate (KNN), and other bio-piezoelectric composites, are promising candidates, offering comparable piezoelectric performances without the associated toxicity. Moreover, despite the pH sensitivity of ZnO, it is partly motivated by its status as a non-toxic and environmentally benign material, aligning with the principle of designing eco-conscious bio-hybrid systems.

(3) Charge separation efficiency: As a key determinant of catalytic performance, efficient separation of photo- or piezo-generated charge carriers can be promoted by introducing built-in electric fields (e.g., via core-shell structures and polar facet engineering) and depositing co-catalysts (e.g., Au or Pt nanoparticles for electron extraction, and MnO2 for hole scavenging)[47].

The micro- and nano-scale design of materials substantially influences both their piezoelectric performance and their interactions with microorganisms. Low-dimensional nanostructures, such as one-dimensional nanowires/nanorods, and two-dimensional nanosheets, are considered ideal candidates owing to their high surface-to-volume ratio and superior strain tolerance, which enable the generation of higher piezoelectric potentials[48]. In contrast, hierarchical porous structures, including three-dimensional porous foams and aerogels, maximize the number of active sites while providing an optimal microenvironment for microbial colonization and nutrient mass transport, effectively mimicking natural porous sediments[38]. Furthermore, embedding piezoelectric nanomaterials (e.g., BaTiO3 nanowires) into flexible polymer matrices (e.g., polydimethylsiloxane, PDMS) creates composite 'energy fabrics' capable of effectively capturing low-frequency mechanical energy from ambient sources, such as waves and fluid flow[39].

Additionally, surface functionalization strategies are crucial for constructing a biocompatible interface that allows efficient 'biopiezocatalysis'. Modifying surfaces with polydopamine, alginate, or specific peptide molecules can simultaneously promote the adhesion of target microorganisms and create a 'bio-inspired interface' that enhances nutrient accessibility, metabolic function, and community organization[24]. Coating with conductive materials, such as poly (3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-poly (styrenesulfonate)-) or reduced graphene oxide, forms an electron 'superhighway'[49], significantly accelerating the transfer rate of electrons from the piezoelectric material to the microbial cell surface. Constructing 3D bio-hybrid structures is a promising approach. For example, using 3D printing technology to fabricate piezoelectric scaffolds with embedded microchannels can enable targeted microbial loading and efficient nutrient delivery[24].

-

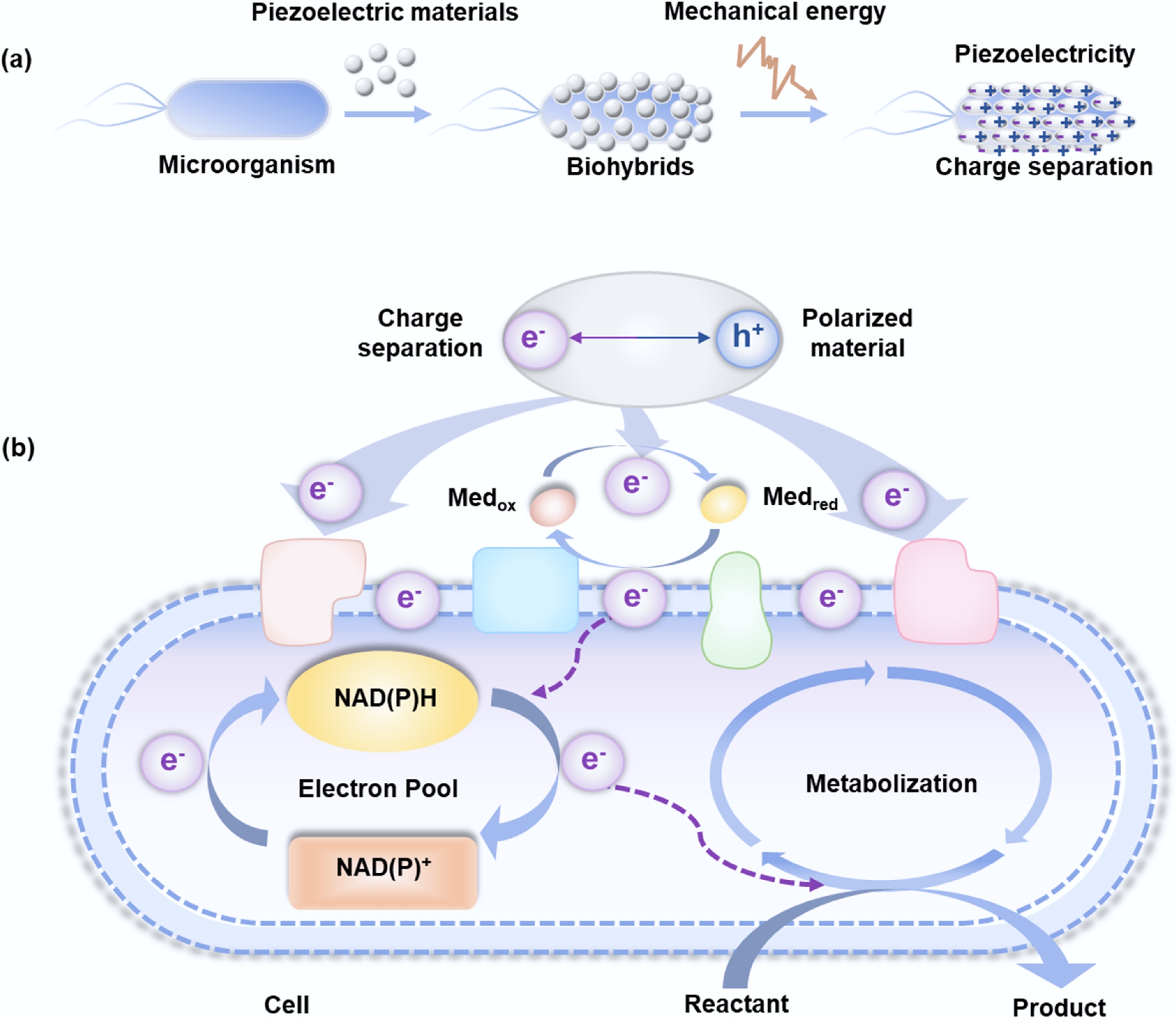

The core of mechano-biogeochemical processes lies in the functional interface formed between the piezoelectric materials and microorganisms. This interfacial contact is not a passive occurrence but is actively driven by microbial behavior and surface chemistry. Microorganisms achieve stable adhesion to piezoelectric surfaces through the secretion of EPS rich in high-molecular-weight polysaccharides, driven by electrostatic interactions, van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and specific chemical reactions (Fig. 3)[50]. Electroactive bacteria, such as Rhodopseudomonas palustris and Geobacter sulfurreducens, and archaea, such as Methanosarcina species, possess sophisticated mechanisms for surface colonization (Fig. 2)[17,18,51].

Figure 3.

Mechanism of the biohybrid piezoelectric system. (a) Construction and proposed principle of bio-piezoelectrical hybrid system. (b) Pathway diagram for proposed electron transfer in the biohybrid system.

The initial attachment is facilitated by bacterial appendages, such as pili and flagella[40]. Subsequently, the bacteria secrete a complex EPS matrix composed of polysaccharides, proteins, and nucleic acids, forming a dense and electrically conductive biofilm on the surface of the piezoelectric material[12]. This close interfacial contact is crucial for efficient electron transfer and minimization of energy loss. Within this biohybrid consortium, the abiotic piezoelectric material functions as a transducer, converting mechanical stimuli into electrical signals, whereas the microbial community harnesses these electrons to sustain redox metabolism and energy conversion processes[9,11]. Notably, typical non-electroactive microorganisms, such as E. coli and B. subtilis, are unable to form hybrid systems, highlighting the indispensable role of the microbial extracellular electron transfer capability in piezoelectric synergy[17,41].

The electron transduction pathway

-

Energy transfer within bio-piezoelectric hybrid systems is predicted to involve the following coordinated steps (Fig. 3):

(1) Charge separation: mechanical force (e.g., vibration and shear) applied to the piezoelectric material induces lattice strain, leading to the separation of electrons (e−) and holes (h+) pairs[52].

(2) Electron transfer to microorganisms: the electrons are transferred from the conduction band of the piezoelectric material to the microbial cells[42]. This process is potentially mediated by extracellular electron transfer (EET) mechanisms in electroactive microorganisms, including direct electron transfer (DET) and mediated electron transfer (MET). DET is achieved through physical contact between the material surface and the outer membrane c-type cytochromes (e.g., OmcS in Geobacter) or conductive microbial nanowires. MET is facilitated by endogenous (e.g., flavins secreted by Shewanella) or exogenous electron shuttles that diffuse between the material surface and the cell[16−18].

(3) Hole scavenging: to prevent energy loss from electron-hole recombination, holes must be promptly consumed via oxidation reactions, such as the oxidation of water molecules producing protons and oxygen or the degradation of organic pollutants in the medium[14,33]. This step is essential for sustaining continuous electron flow.

Although overall electron transfer is often described as occurring 'via EET pathways'[17,18], the microscopic mechanisms remain inadequately understood. The similarities and differences between the specific molecular components and regulatory mechanisms involved in piezoelectric EET (piezo-EET) and traditional extracellular respiration remain unclear. Current models predominantly assume that electrons transfer through known EET components, such as c-type cytochromes[17−19]. For instance, it was proposed that in the Shewanella oneidensis MR-1/ZnO biohybrid system driven by hydraulic kinetic energy, the piezo-electrons are transferred from the outer membrane c-type cytochromes (MtrC, MtrA, MtrB, and OmcA) to the inner membrane CymA[19]. This is supported by the upregulation of genes associated with the typical Mtr pathway (i.e., mtrC, mtrA, mtrB, and omcA) in the S. oneidensis MR-1/ZnO biohybrid system[19]. Extracellular electrons can be transferred into S. oneidensis MR-1 via the typical reverse EET chain through the outer membrane cytochrome c, including MtrC, MtrA, MtrB, and OmcA[43]. The electrons then enter the periplasmic space potentially via the menaquinone pool and a second CymA, ultimately reducing NO3− to NH4+ (with NO2− as an intermediate) through the dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) pathway[19]. Moreover, a fundamental shift in the electron source (e.g., from chemical to electrical energy) triggers metabolic network rewiring in microorganisms[44]. Given the pulsed nature and high potential characteristics of piezoelectric electron flows, a key question is whether they trigger the induction of a unique EET protein profile or a fundamentally novel electron shuttle mechanism, both of which require further study.

Microbial metabolic and genomic responses

-

The influx of piezoelectric electrons influences microbial physiology, shifting cellular metabolism toward more reductive states (Fig. 3). The primary effect is an increase in the intracellular reducing equivalents. For example, the piezoelectric electron supply leads to a marked increase in the NADPH/NADP+ ratio in bacteria, such as Cupriavidus necator, when provided with piezoelectric electrons[17,18]. The enhanced reducing power subsequently drives various anabolic processes, including the Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) cycle for autotrophic CO2 fixation, the DNRA pathway for NO3− reduction, and the assimilatory sulfate reduction pathway for SO42− reduction. Furthermore, transcriptomic analyses have provided direct evidence of metabolic shifts. In a biohybrid system of R. palustris and BaTiO3 nanoparticles under vibration, genes encoding c-type cytochromes (key EET components), key enzymes of the CBB cycle, and denitrification pathway enzymes (e.g., nitrate and nitrite reductases) were significantly upregulated[16,17].

-

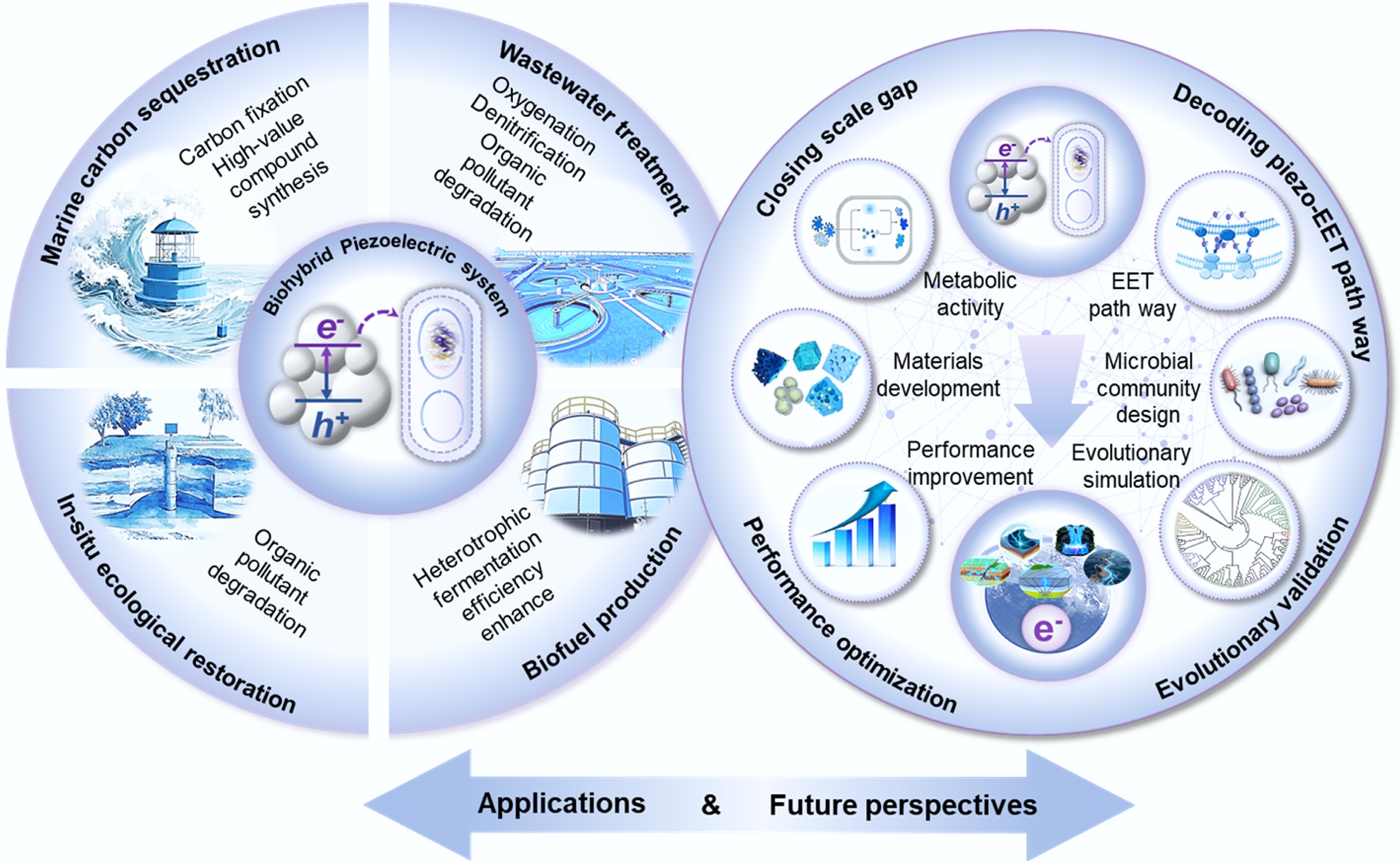

The scientific implications of mechano-driven carbon cycling lie in its capacity to expand novel microbial niches into traditional energy-limited environments. Deep subsurface and abyssal sediments, historically mainly considered largely inactive due to the absence of light and pronounced chemical gradients, are now being re-evaluated[6,45,46]. The mechano-biogeochemistry framework proposes that subtle yet persistent mechanical energy derived from crustal forces, tidal friction, and wave action may serve as primordial drivers of 'dark carbon fixation' and 'dark methanogenesis' in these realms[20,22].

Tremblay et al.[18], and Ren et al.[17] demonstrated that in a biohybrid system composed of microorganisms and BaTiO3, mechanical energy drives R. palustris and C. necator to assimilate CO2 into cellular biomass or convert it into bioplastic polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB). Furthermore, the rock fracturing liberates electrons from pervasive Si-O bonds and produces high-energy compounds, such as H2 and H2O2. The H2 may subsequently act as an electron donor for methanogenesis[20,53]. The electroactive methanogen, Methanosarcina barkeri, and the electroactive acetogen, Moorela thermoacetica, were successfully used to drive CO2-to-CH4 and CO2-to-acetate conversion with BTO, respectively, under mechanical stirring[17]. This finding provides evidence of electron exchange between methanogens and piezoelectric materials.

Moreover, the holes generated during piezocatalysis exhibit a strong oxidative potential. Wang et al.[14] revealed that tourmaline minerals subjected to vibration can decompose organic dyes, such as methyl orange. This abiotic degradation process can be coupled with microbial metabolism, wherein piezocatalysis partially oxidizes recalcitrant organic compounds, thereby enhancing their bioavailability for subsequent microbial mineralization. Such piezocatalytic oxidation[14], coupled with subsequent microbial processes, such as methanogenesis driven by mechanical energy[20], may establish a synergistic mechano-driven carbon degradation cascade in the deep biosphere.

Diverse transformation pathways for the nitrogen cycle

-

Nitrogen cycling processes, particularly denitrification, are energy-intensive, and mechano-biogeochemistry offers a novel energy input. Ye et al.[16] demonstrated that a struvite-based piezoelectric system under mechanical vibration can drive Thiobacillus denitrificans to completely reduce nitrate (NO3−) to nitrous oxide (N2O) and dinitrogen (N2). Similarly, Guo et al.[19] reported a bacteria-piezocatalyst system that uses hydraulic kinetic energy to fully reduce NO3− to ammonium (NH4+). The divergent endpoints of these nitrogen transformations underscore the marked metabolic plasticity of piezoelectric microbial systems. This partitioning of the reduction pathways is governed by a combination of physicochemical and biological determinants. The band structure of piezoelectric materials can influence the initial reduction product by determining the energy of the injected electrons[47]. The composition of a microbial consortium is an important factor. Consortia harboring a complete denitrification genetic repertoire (e.g., nirS and nosZ) facilitate the full reduction of N2O to N2. In contrast, communities lacking nitrous oxide reductase (encoded by nosZ) accumulate N2O as the terminal product[37]. Furthermore, environmental parameters, such as pH and organic carbon content, further modulate electron flow by affecting the cell surface charge and the activity of endogenous electron shuttles, thereby steering the metabolic outcome[48].

Sulfur, iron cycles, and their interconnection

-

Piezoelectric-driven sulfur cycling has been confirmed. Wu et al.[20] proposed a link between crustal faulting and biological redox cycling in the deep subsurface that likely involves sulfur-transforming microorganisms. Mechanical energy from faulting can power sulfate-reducing bacteria (e.g., Desulfovibrio), which are known to be electroactive. Nonetheless, the current evidence for mechano-driven sulfur cycling remains preliminary and requires a more concrete hypothetical framework based on field observations[20]. Furthermore, mechanochemical processes can regulate iron-sulfur (Fe-S) mineral formation by providing non-biological energy to drive abiotic synthesis under ambient conditions. Mechanical stress can induce the formation of structurally defective, nanoscale Fe-S minerals (e.g., mackinawite and pyrite) that exhibit enhanced electrochemical activity owing to their high surface energy and exposed unsaturated sites[20]. These reactive surfaces facilitate the adsorption and activation of small molecules (e.g., CO2 and N2), catalyzing key prebiotic reactions, such as carbon and nitrogen fixation. Consequently, mechanochemically formed Fe-S minerals potentially serve as primitive metabolic interfaces, functioning as mineral prototypes for modern iron-sulfur proteins and laying the foundation for early prebiotic metabolic networks. This perspective offers novel insights into the origin and evolution of metabolic systems in early life.

-

The proposed mechano-biogeochemical paradigm offers a new perspective on the evolution of early metabolic pathways and biogeochemical cycles. In an anoxic Archean environment, the evolution of oxygen-utilizing enzymes required transient exposure to oxidants, which is a prerequisite for photosynthesis. A plausible mechanism involves the mechanical grinding of quartz-rich sediments in fluvial and coastal settings, which generates ROS, such as H2O2 and O2[12]. This process creates transient, localized oxic niches that may serve as 'training grounds' for the development of antioxidant systems and oxygen-utilizing enzymes in microorganisms, such as methanotrophic archaea. Concurrently, the mechanical energy derived from tidal forces, wave action, and seismic activity is now recognized as a pervasive energy source. This mechanical energy could have driven piezoelectric catalysis in the extensive subaerial and shallow-marine sediments. Therefore, it potentially contributes to a multitiered energy network for early chemotrophic life, significantly expanding the range of potential habitats and metabolic possibilities.

The implications of this framework also extend to the modern deep biosphere, which is a vast yet energy-limited habitat. Here, the mechanical energy from crustal faulting and earthquakes is posited to be more than a mere survival subsidy and may act as a potential architect of deep ecosystems. The fracturing of piezoelectric minerals during tectonic events generates transient electric fields that can stimulate microbial metabolism, such as sulfate reduction and methanogenesis[54]. This coupling implies that tectonically active regions can support greater microbial biomass and diversity than geologically quiescent areas, directly influencing the deep subsurface ecology and geochemistry. Quantifying the contributions of mechano-driven processes to global biogeochemical cycles represents a significant research frontier. Despite advances in laboratory demonstrations, achieving accurate in-situ quantification remains a major challenge. Precise assessment of this 'hidden hand' is crucial for understanding its actual impact on planetary-scale element cycling.

Future perspectives and challenges

-

The performance metrics and limitations of the key bio-piezoelectric systems are summarized in Table 1. The principles of mechano-biogeochemistry offer promising avenues for sustainable technology (Fig. 4). However, their practical implementation faces substantial challenges regarding feasibility, cost, and ecological risks. For instance, while autotrophic biomanufacturing can harness mechanical energy for CO2 conversion, the economic viability and scalability of wave-powered coastal bioreactors for producing compounds (e.g., PHB[18]) require rigorous assessment. Similarly, the in situ remediation of aquifers using piezoelectric nanoparticles activated by acoustic waves must address critical concerns, including the high cost of nanomaterial synthesis, potential ecotoxicity, and challenges of monitoring and retrieval in subsurface environments. Furthermore, while piezocatalysis shows potential to augment fermentative biofuel production by generating in-situ electron donors, the energy input required for 'process mixing' must be justified by a net gain in energy output. Moreover, incorporating piezoelectric materials into the water treatment infrastructure can facilitate denitrification, thereby reducing the high energy consumption associated with aeration tanks for mixing in conventional processes[16]. This approach exemplifies metabolic pathway engineering, where adjusting key system parameters can optimize the process for either complete nitrogen removal or the recovery of valuable nutrients. More importantly, under mechano-driving conditions, nitrogen transformation can be divided into two distinct pathways: complete denitrification to N2[16], or dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium[19], which is determined by the structure of the microbial community, electronic properties (e.g., band structure) of the piezoelectric material, and localized chemical microenvironment. Conversely, the genetic makeup of a microbial community ultimately dictates the metabolic outcomes. Only consortia possessing the full suite of denitrification genes (e.g., nirS and nosZ) can complete the reduction to N2[37], whereas those equipped with DNRA enzymes (e.g., nrfA) will channel electrons toward NH4+ production. However, the role of the material band structure in microbial genetics should be clearly delineated in future studies.

Table 1. Comparison of key bio-piezoelectric systems

System function System composition Performance metrics Main limitations Ref. Piezoelectric material Microorganism Denitrification system Struvite Thiobacillus denitrificans 1. Achieved near 100% NO2− reduction in synthetic wastewater.

2. Enhanced nitrate removal rate by up to 117% in real wastewater treatment.

3. Mechanical to electrical energy conversion efficiency of 0.4%.1. The main product is N2O (~64.5%), a potent greenhouse gas, due to ROS inhibition of N2O reductase.

2. Relatively long reaction time (hours to days).[16] Multi-functional metabolic system Barium titanate (BaTiO3) Rhodopseudomonas palustris and other electroactive microorganisms 1. Drove carbon fixation, increasing biomass ~10 fold.

2. Achieved highly efficient NO3− reduction (near complete).

3. Successfully applied to various metabolic processes including CH4 production, SO42− reduction, and pollutant degradation.1. Broad but limited applicability: The process relies on the microorganism's ability for extracellular electron uptake and is ineffective for non-electroactive microbes (e.g., E. coli).

2. Alkaline conditions generated during piezoelectric transduction may create potential oxidative stress for cells.[18] Nitrate reduction to ammonia system ZnO Nanorods Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 1. NO3−removal efficiency: 97.97%.

2. NH4+ production rate: 40.2 μmol·L−1·h−1.

3. Stability: Maintained 93.4% activity after three cycles.1. Requires optimization of water flow rate (optimal 0.5 m·s−1).

2. High flow rates may cause separation of materials from cells.

3. Not yet validated in real wastewater.[19] Bioplastic synthesis system ZnO nanosheets Cupriavidus necator 1. Autotrophic culture: PHB production increased over 3-fold (reaching 1,093.5 mg·L−1), efficiency 2.4%.

2. Heterotrophic culture: PHB production doubled (reaching 8.2 g·L−1), efficiency 6.2%.

3. Significantly increased intracellular NADPH/NADP+ ratio.1. Ultrasound may cause physical damage to cells at high intensities or prolonged exposure.

2. H2 produced by piezoelectric materials is insufficient to explain all metabolic enhancement; the process relies on electron shuttles secreted by microorganisms.[51] A key consideration is the production and consumption of N2O, a potent greenhouse gas and an intermediate in denitrification. Whether piezoelectric flow in biohybrid systems efficiently reduces N2O to N2 or results in transient accumulation and emission remains unclear. To mitigate this risk, future work should establish experimental verification paths, such as tracking isotopic labels in 15N2O to quantify reduction kinetics and coupling this with metatranscriptomic analyses of the nosZ gene (encoding N2O reductase) expression to precisely decipher N2O transformation pathways and corresponding microbial responses. Additionally, targeted control strategies should be formulated, including the selective enrichment of N2O-reducing microorganisms via biocathode conditioning or bio-engineering of microbial consortia with high nosZ activity, rational design of piezoelectric materials with band structures that promote deeper reduction steps, and optimization of operational parameters, such as mechanical force frequency and C/N ratio.

Specifically, control strategies can explore the selective enrichment of N2O-reducing microbes via biocathode conditioning, the rational design of piezoelectric materials with band structures that favor deeper reduction steps, and the optimization of operational parameters (e.g., mechanical force frequency and C/N ratio) to minimize N2O accumulation. Concurrently, control strategies should be investigated, including material-level heterojunction design of heterojunctions to modulate electron flux and bio-level engineering of microbial consortia with high nosZ activity. Resolving the fate of N2O is paramount for conducting life-cycle assessments and de-risking the environmental applications of this technology, representing a critical frontier for future research[16].

The conceptual possibilities of mechano-biogeochemistry are explained based on current evidence; however, there are several challenges in transitioning from laboratory demonstrations to a quantitatively robust component of Earth system science. Future progress will require systematic, interdisciplinary efforts to address the following key challenges (Fig. 4):

(1) Closing the gap from mechanistic evidence to ecosystem fluxes. A central challenge is quantifying the in-situ contribution of mechano-driven processes to natural biogeochemical cycles, such as through mesocosm experiments that simulate realistic environmental dynamics (e.g., tidal cycles and shear forces). This should be coupled with the development of sensing systems capable of detecting transient redox potentials and metabolic activity in situ at mineral-microbe interfaces. The ultimate goal is to generate quantitative process rates that can be integrated into Earth System Models (e.g., CESM)[55].

(2) Decoding the molecular black box of piezo-EET. However, the molecular and regulatory mechanisms underlying microbial electron uptake from transient piezoelectric potentials remains largely unknown. The key questions include whether piezo-EET uses the same constitutive pathways as electrotrophy with constant potentials or induces a unique metabolic and gene expression state. Further studies should combine multi-omics (proteomics and transcriptomics) and genetic knockout approaches to identify the specific c-type cytochromes, electron shuttles, and regulatory networks involved.

(3) Performance optimization via intelligent materials and community design. Future advancements will depend on moving from proof-of-concept materials to intelligently designed, environmentally compatible 'biopiezocatalytic' systems. Machine learning can be used to predict and screen piezoelectric materials with optimal band structures aligned with the target microbial redox potentials (e.g., for CO2 reduction or denitrification), high piezoelectric coefficients, and robust environmental stability. Simultaneously, engineering or harnessing synthetic microbial communities with complementary metabolic functions can enhance the system stability and functionality.

(4) Assessing the evolutionary feasibility. The hypothesis that mechanical energy sources, such as those generated via piezoelectric effects, can serve as both an energy source and selective pressure for the evolution of early redox mechanisms requires experimental testing. This may involve the cultivation of simple, ancient prokaryotes or engineered systems containing reconstructed early enzyme homologs under simulated early Earth conditions. The key to this simulation is the application of controlled mechanical forcing (e.g., agitation of piezoelectric minerals, such as quartz, within anoxic chambers) to replicate putative mechanochemical environments.

-

The mechano-biogeochemistry paradigm broadens our understanding of the forces that drive Earth's cycles. By revealing how ubiquitous mechanical force, transduced via the piezoelectric effect, can directly drive microbial metabolism, we have identified a previously 'hidden energetic hand' that may have shaped life from inception. This framework explains survival in energy-poor environments and offers new insights into Earth's early history and sustainable technologies. As we begin to establish its global significance and harness its potential, mechano-biogeochemistry stands to become an integral part of a unified theory of planetary functioning, which may extend beyond Earth. The next major challenge is to evaluate the actual contributions of these microscopic mechanisms to global macroscopic element fluxes. Bridging this 'scale gap' will be pivotal for advancing this research area from a conceptual innovation to an indispensable component of Earth-system science.

-

Accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/ebp-0025-0020.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Lingyu Meng: conceptualization, formal analysis, data curation, writing − original draft, funding acquisition. Li Xie: formal analysis, writing − original draft, writing − review and editing, funding acquisition. Yong Yuan: writing − review and editing, supervision. Shungui Zhou: conceptualization, resources, writing − review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

This work was supported by the Continuation Funding for the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (Grant No. 42525702), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 42577527 and 42507128), and the 'One-hundred-person project' of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. 552023000159).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

A novel mechano-biogeochemical framework is proposed in which ubiquitous mechanical force drives global biogeochemical cycles.

The piezoelectric effect converts environmental mechanical forces from the environment into electrons that drive microbial metabolism in biohybrid systems.

Mechano-driven processes may contribute to biogeochemical pathways in energy-scarce settings, such as in the deep biosphere.

The mechano-biogeochemical approach provides a possible explanation for early metabolic evolution.

The mechano-biogeochemical approach is expected to contribute to sustainable bioremediation and energy-efficient bioproduction.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Lingyu Meng, Li Xie

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Meng L, Xie L, Yuan Y, Zhou S. 2026. The hidden mechanistic hand: the mechanical force that drives global biogeochemical cycles. Environmental and Biogeochemical Processes 2: e003 doi: 10.48130/ebp-0025-0020

The hidden mechanistic hand: the mechanical force that drives global biogeochemical cycles

- Received: 21 October 2025

- Revised: 02 December 2025

- Accepted: 24 December 2025

- Published online: 20 January 2026

Abstract: Microbial life has traditionally been understood to be driven by phototrophic and chemotrophic energy sources. However, recent discoveries have revealed the previously overlooked potential role of ubiquitous mechanical energy to drive biogeochemical cycles. This review presents recent advances in mechanically driven biogeochemistry and proposes a novel paradigm in which the piezoelectric effect converts mechanical forces from environmental processes (e.g., river flow, tides, and seismic activity) into electrons that drive microbial metabolism. This review uniquely consolidates these dispersed insights into a coherent 'mechano-biogeochemistry' framework, explicitly distinguishing it from proximate fields like tribochemistry, and mechanochemistry by its focus on a microbially mediated, two-step energy transduction pathway (mechanical force → electron → biochemical energy). This study investigates the mechanisms by which biohybrid piezoelectric systems, composed of piezoelectric materials such as BaTiO3, ZnO, and quartz, in conjunction with electroactive microorganisms, facilitate processes including autotrophic carbon fixation, denitrification, sulfate reduction, and methanogenesis in the absence of light or conventional chemical electron donors. Elucidating this mechanism not only provides an alternative and potential theoretical basis for understanding microbial survival strategies in energy-limited environments, such as the deep biosphere, but also potentially offers new perspectives for exploring the evolution of early metabolic pathways and global element cycling patterns. By integrating principles from materials science, geophysics, and microbiology, this review proposes 'mechano-biogeochemistry' as a significant complementary framework for understanding Earth's element cycles, with profound implications for environmental engineering and sustainable bioproduction.