-

Ischemic retinopathy primarily includes proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR), retinal vein occlusion, and retinopathy of prematurity[1,2]. Their common pathological process involves ischemia and hypoxia-induced disruption of the blood-retinal barrier and retinal vascular occlusion, which subsequently triggers pathological neovascularization accompanied by hemorrhagic, exudative, proliferative, and fibrotic changes, ultimately resulting in severe and irreversible visual impairment. Retinal ischemia induces the overexpression of pro-angiogenic factors, with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) playing a pivotal role in promoting vascular permeability and retinal neovascularization[3]. Although anti-VEGF therapies have shown significant efficacy in reducing retinal neovascularization, a substantial subset of patients remains unresponsive[4,5]. Therefore, further elucidation of the pathogenesis of ischemic retinopathy and identification of new therapeutic targets remain pressing issues.

Previous genetic study highlighted the potential role of cytoskeleton-associated protein 2 (CKAP2) in the pathogenesis of PDR. Whole exome sequencing revealed a significant enrichment of CKAP2 mutations in patients with PDR compared to diabetic patients without retinopathy[6]. CKAP2 expression was also demonstrated to be regulated by VEGF and p53 under high-glucose conditions[7]. Located on chromosome 13q14, CKAP2 has a critical role in mitotic progression and is highly expressed in various cancers[8−11]. Given its predominant expression in actively proliferating cells, researchers utilized an adenoviral vector encoding a human Ckap2-specific trans-splicing ribozyme for targeted therapy. This approach selectively induced cytotoxicity in tumor cells, suggesting that CKAP2 holds promise as a potential therapeutic target for anti-cancer strategies[12,13]. However, the mechanisms linking CKAP2 to retinal neovascularization still remain to be elucidated.

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) is a master regulator of cellular responses to hypoxia, as well as a key driver of VEGF expression under ischemic conditions[14]. Notably, HIF-1α activity is tightly regulated by various post-translational modifications and protein-protein interactions. In light of the overlapping roles of CKAP2 and HIF-1α in cellular proliferation and stress responses, CKAP2 was hypothesized to interact with HIF-1α-related pathways and promote the progression of PDR. To examine this hypothesis, expression of CKAP2 and HIF-1α was first investigated in retinal tissues from an oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) murine model and in human retinal microvascular endothelial cells (HRMECs) under hypoxic conditions. Regulatory interactions between CKAP2 and HIF-1α were subsequently explored in hypoxia-stimulated HRMECs to elucidate their potential roles in retinal neovascularization.

-

A published single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) dataset (GEO accession number: GSE174400) containing the transcriptomic profiles of retinal cells from an OIR murine model was re-analyzed to reproduce the clustering patterns observed in the original study[15]. The clustering analysis was conducted on retinal cell data collected on postnatal day 14 (P14) using an established R Markdown script. Initial steps involved demultiplexing and alignment of sequencing reads, followed by the generation of digital expression matrices for each sample. These matrices underwent rigorous quality control and normalization in line with previously described methods[16−18]. Additionally, batch effects were corrected to ensure consistency across samples. Principal component analysis was employed for dimensionality reduction, and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding was used to visualize the single-cell clusters in two-dimensional space based on the principal component scores[19]. To visualize gene expression, dot plots were generated for key genes, Ckap2 and Hif-1α. Further bioinformatics analysis and visualization were conducted using the Seurat package in R.

Cell culture

-

HRMECs were purchased from Bioesn Biotechnology (BES2536HC, Shanghai, China). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Procell, Wuhan, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 mg/dl of glucose, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S). Cultures were maintained in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. HRMECs were exposed to either normoxic (21% O2) or hypoxic (1% O2) conditions, depending on the experimental setup.

Construction of Ckap2 knockdown plasmid

-

The Ckap2 knockdown plasmid was obtained from HanYi BioSciences (Guangzhou, China). The full-length cDNA of Ckap2 (NM_018204.5) was cloned into the pCDH-CMV-mcs-3xflag-EF1a-copGFP-t2a-puro vector to construct a plasmid for RNA interference.

Cell transfection

-

The 293T cells were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% P/S in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. For transfection, cells were plated in six-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well and allowed to adhere overnight. Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine™ 3000 (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 2 μg of plasmid DNA was mixed with 125 μL of Opti-MEM™ Reduced Serum Medium (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) and 5 μL of Lipofectamine™ 3000 reagent. After incubation at room temperature for 10 to 15 min, the DNA-lipid complexes were added dropwise to the cells. Transfection was allowed to proceed for 6 h, after which the medium was replaced with fresh complete DMEM. Cells were harvested 24–48 h post-transfection for further analysis.

Construction of stable Ckap2 knockdown endothelial cells

-

Lentiviral particles encoding Ckap2-specific shRNA or control shRNA (non-targeting) were transferred into HRMECs. Briefly, 2 × 105 cells were plated in six-well plates and incubated overnight. The cells were then transduced with lentivirus at a multiplicity of infection of ten, in the presence of 8 μg/mL of polybrene (Biosharp, Anhui, China). After 24 h, the medium was replaced with fresh complete medium, and stable clones were selected by adding 1 μg/mL of puromycin for 48 h. Selection continued for one to two weeks until puromycin-resistant colonies were observed. The knockdown efficiency was confirmed via Western blot analysis.

OIR murine model

-

Male and female C57BL/6J mice were obtained from the Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center. The OIR model was established as previously described[20]. On postnatal day 7 (P7), the mice were exposed to 75% oxygen in a sealed chamber for 5 d. On P12, the mice were returned to normoxic conditions. On P12, P14, P17, and P22, the mice were sacrificed for retinal collection and analysis. During the entire experimental period, mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) animal facility under controlled environmental conditions (temperature 22 ± 2 °C, relative humidity 50%–60%, and a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle). Animals had free access to standard laboratory chow and sterile water ad libitum. All animal procedures were approved by the Guangdong Provincial People's Hospital Ethics Committee (Approval No. KY-Z-2021-571-01) and complied with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

Western blotting

-

Proteins were extracted from the cells and retinas using lysis buffer (89900, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and protein concentrations were determined using bicinchoninic acid assay (23227, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Equal amounts of protein were separated by SDS-PAGE using 7.5%, 10%, or 12.5% gels and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) via electroblotting. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1 h, followed by overnight incubation with primary antibodies at 4 °C. After washing, membranes were incubated with species-specific secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1–2 h. The antibodies used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic protein separation

-

Cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins were separated using the Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Kit (KGB5302, KeyGEN BioTECH, Jiangsu, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Western blot analysis was performed on both protein fractions to assess target protein localization.

Immunoprecipitation (IP)

-

Protein extraction from HRMECs was performed using IP lysis buffer (87787, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Proteins were incubated with target gene antibodies or isotype controls overnight at 4 °C, followed by precipitation using Protein A/G agarose beads. Protein complexes were eluted in SDS-PAGE loading buffer and subjected to western blot analysis.

Immunofluorescence

Retro-orbital injection and retinal isolectin B4 immunofluorescence staining

-

After mice were anesthetized, a retro-orbital injection of 100 µL of FITC (5 mg/mL) was administered. After fixation of the eyeballs in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15–30 min, retinas were dissected under a stereomicroscope, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min, and blocked with 5% goat serum for 30 min. Retinas were incubated overnight with isolectin B4 (IB4, I21413, Thermo Fisher Scientific). After the retinas were mounted, panoramic retinal images were captured using a confocal microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) with 'File' and 'Z-Stack' scanning.

Immunofluorescence staining in ocular paraffin-embedded sections

-

Eye sections were deparaffinized and subjected to antigen retrieval, followed by blocking with 5% goat serum and 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 30 min. The sections were incubated overnight with primary antibodies and subsequently with fluorescent secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1–2 h in the dark. After the sections were mounted with DAPI-containing mounting medium, they were visualized using a confocal fluorescence microscope.

Cellular immunofluorescence staining

-

HRMECs were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, followed by multiple PBS washes and blocking with 3% BSA in PBS for 30 min. After incubating with primary antibodies for 2 h, the cells were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. The cells were mounted with DAPI-containing mounting medium and imaged using a confocal fluorescence microscope.

Colocalization analysis of immunofluorescence staining

-

Colocalization analysis of CKAP2 with HIF-1α was quantified as the Pearson's coefficient using the JACoP plugin of the extended ImageJ version Fiji. Pearson's coefficient is a correlation coefficient representing the relationship between two variables (e.g., CKAP2 and HIF-1α signals in this study)[17]. As a control, the image with the HIF-1α signal was rotated 180° out of phase, and the same analysis was performed. Pearson's coefficients achieved with the original and rotated images were then compared with the estimated colocalization.

Statistical analysis

-

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS and GraphPad Prism software. Unpaired t-tests were employed to conduct comparisons between two groups, and one-way analysis of variance to conduct comparisons among multiple groups. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

-

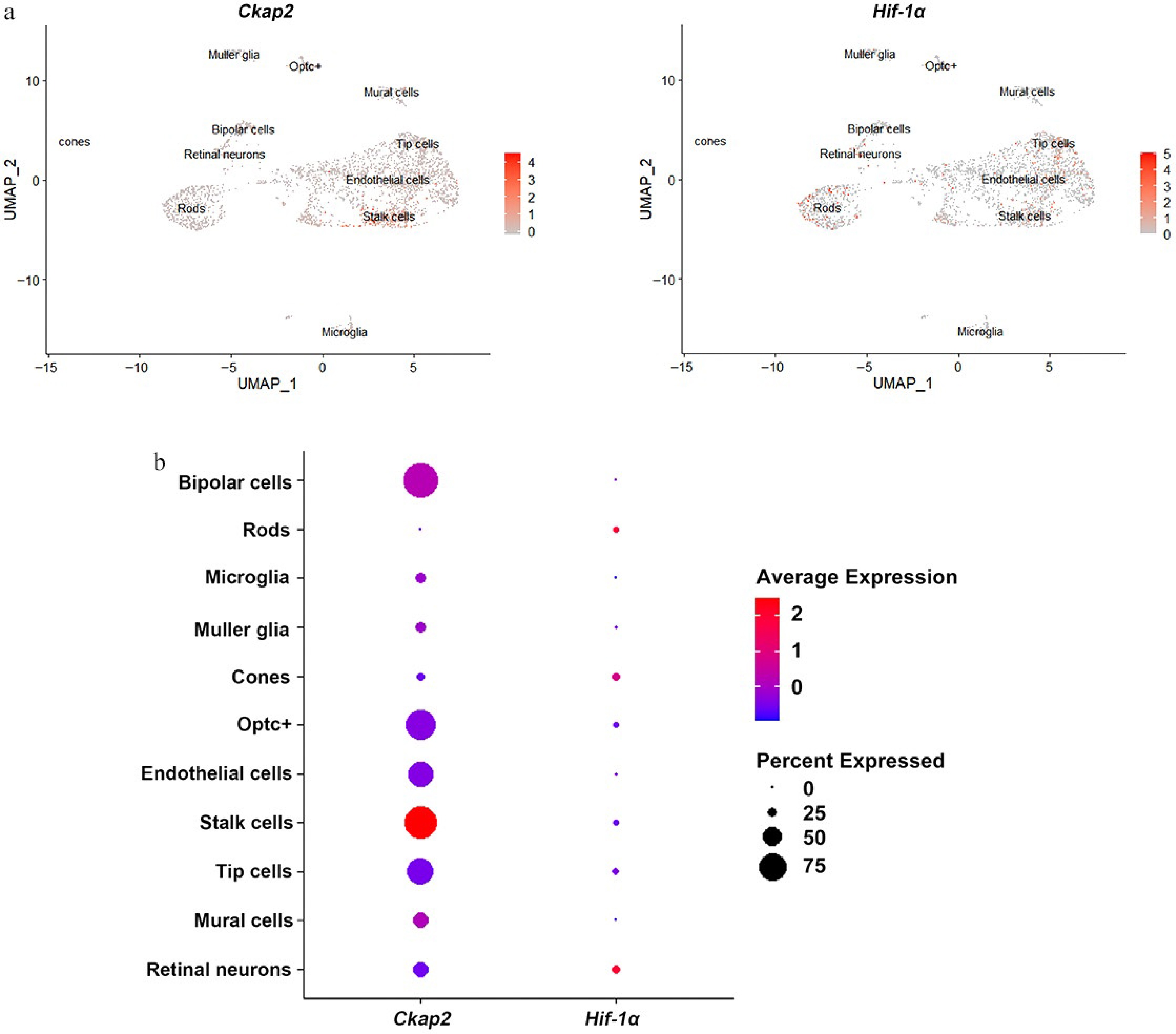

Reanalysis of the scRNA-seq dataset (GEO accession: GSE174400) revealed distinct transcriptional profiles across various retinal cell types in the OIR murine model (Fig. 1a). Dot plot analysis demonstrated substantial variability in the expression of Ckap2 and Hif-1α across different retinal cell clusters. Specifically, Ckap2 exhibited a pronounced expression pattern in endothelial cells, with higher levels observed in stalk cells, while Hif-1α showed a relatively high expression level in retinal neurons (Fig. 1b). These findings suggest that CKAP2 and HIF-1α exhibit distinct, cell-type-specific expression patterns in an OIR mouse model. Meanwhile, as key components of the neurovascular unit, both retinal vascular endothelial cells and neurons are involved in hypoxia-induced retinal neovascularization.

Figure 1.

Expression patterns of Ckap2 and Hif-1α in retinal cells in the OIR model. (a) UMAP visualization of single-cell RNA sequencing data showing the expression distribution of Ckap2 (left) and Hif-1α (right) across various retinal cell populations in the OIR model on postnatal day 14. (b) Dot plot showing the relative expression levels (color intensity) and proportion of expressing cells (dot size) for Ckap2 and Hif-1α across retinal cell types. Data were reanalyzed from the published scRNA-seq dataset GSE174400; no additional statistical tests were performed for this descriptive analysis. UMAP, uniform manifold approximation and projection; OIR, oxygen-induced retinopathy; Ckap2, cytoskeleton-associated protein 2; Hif-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha.

Developmental stage-specific expression patterns of CKAP2 and HIF-1α

-

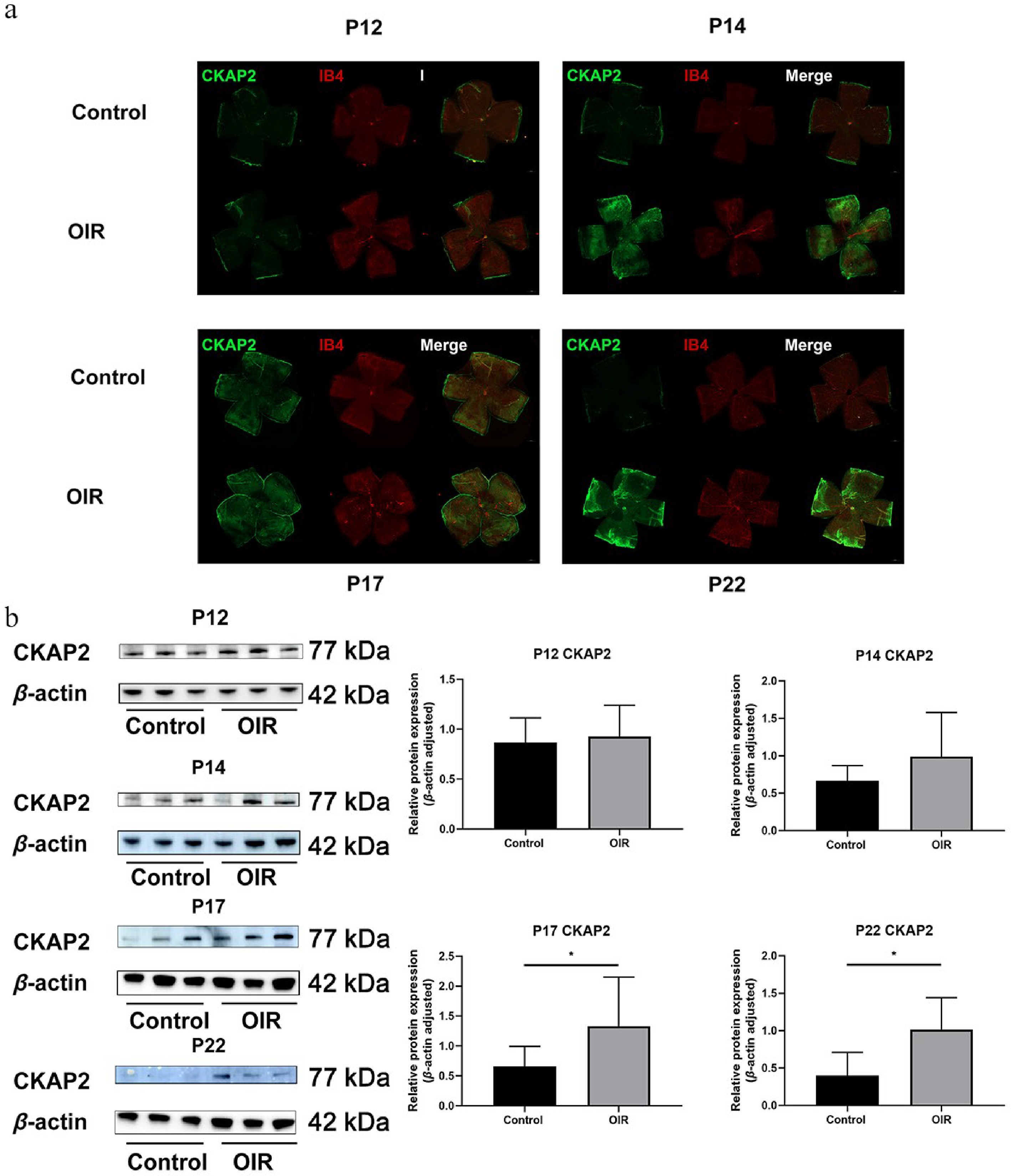

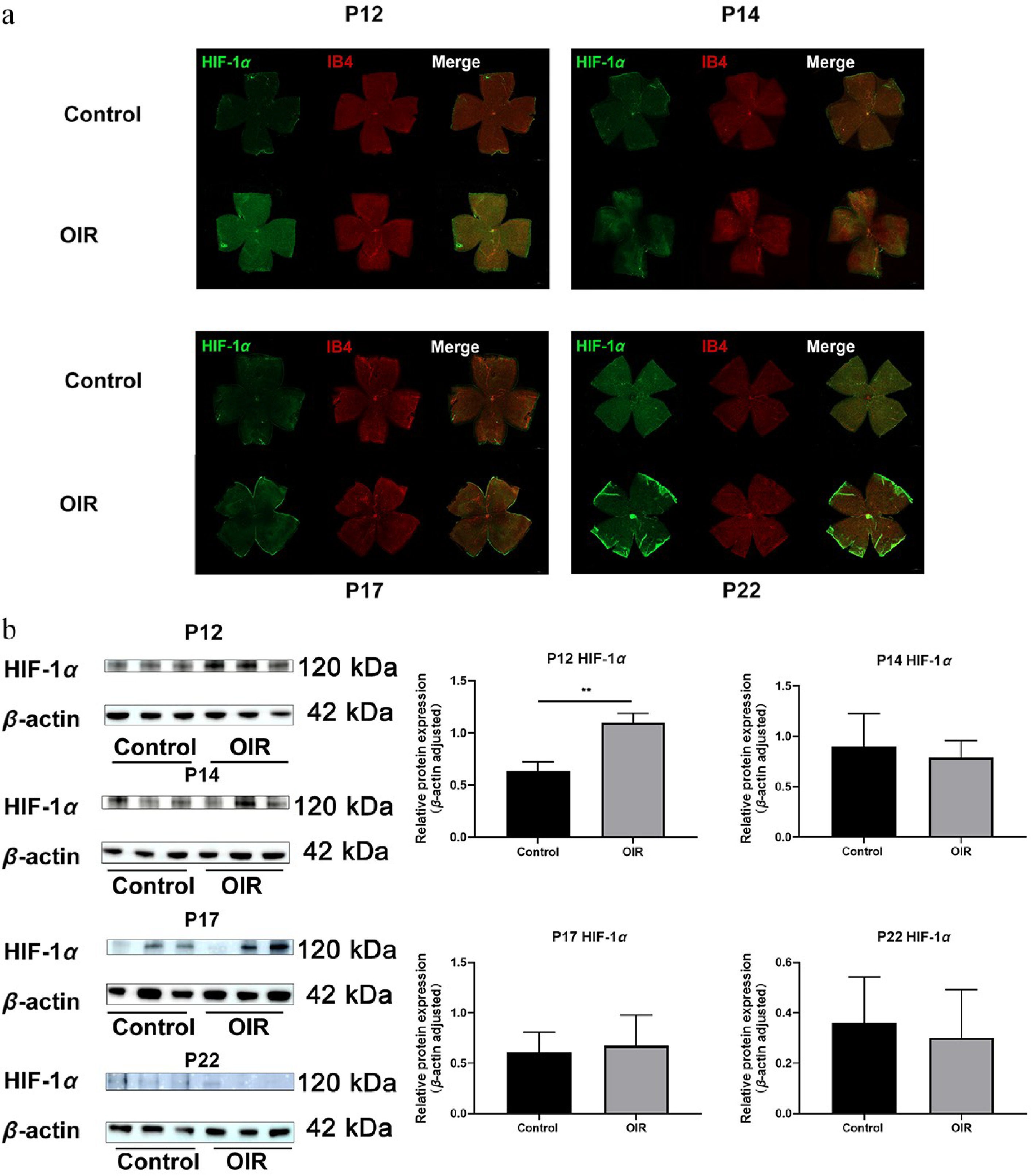

The protein expression levels of CKAP2 and HIF-1α were assessed across multiple developmental stages (P12, P14, P17, and P22) in OIR mice and controls (Supplementary Fig. S1). Immunofluorescence staining and western blot analysis revealed no significant differences in CKAP2 expression between the control and OIR groups on P12 (Fig. 2). Although immunofluorescence staining indicated higher CKAP2 expression levels on P14, this increase was not significantly different in western blot. On P17 and P22, a significant increase in CKAP2 expression was observed in the OIR group compared with the control group, with the highest expression level on P22. In contrast, HIF-1α expression was significantly higher on P12 in the OIR group, but was no significant differences between the OIR and control groups on P14, P17, and P22 (Fig. 3). These results suggest that CKAP2 and HIF-1α exhibit developmental stage-specific expression patterns in OIR models: CKAP2 shows significant upregulation at later stages (on P17 and P22), whereas HIF-1α is significantly elevated at the early stage (on P12), implicating their different roles in retinal vascular development and hypoxic responses.

Figure 2.

Spatial expression and colocalization of CKAP2 with IB4 in the retinas of OIR and control mice at different developmental stages. (a) Immunofluorescence staining of CKAP2 (green) and IB4 (red) in retinal flat mounts from control and OIR mice on postnatal days (P) 12, 14, 17, and 22. Scale bar: 500 µm. Representative images were obtained from n = 3 mice per group at each time point. (b) Western blot analysis of CKAP2 protein expression in retinal tissues from control and OIR mice at different developmental stages (on P12, P14, P17, and P22. n = 3 per group). Quantification of CKAP2 expression is normalized to β-actin. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 mice per group); comparisons between control and OIR groups at each time point were performed using unpaired two-tailed t-tests. * p < 0.05. CKAP2, cytoskeleton-associated protein 2; HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha; IB4, isolectin B4; OIR, oxygen-induced retinopathy.

Figure 3.

Spatial expression and colocalization of HIF-1α with IB4 in the retinas of OIR and control mice at different developmental stages. (a) Immunofluorescence staining of HIF-1α (green) and IB4 (red) in the same retinal flat mounts from control and OIR mice on post-natal days (P) 12, 14, 17, and 22. Scale bar: 500 µm. Representative images were obtained from n = 3 mice per group at each time point. (b) Western blot analysis of HIF-1α protein expression at different developmental stages (on P12, P14, P17, and P22. n = 3 per group). Quantification of HIF-1α expression is normalized to β-actin. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3 mice per group); comparisons between control and OIR groups at each time point were performed using unpaired two-tailed t-tests. ** p < 0.01. CKAP2, cytoskeleton-associated protein 2; HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha; IB4, isolectin B4; OIR, oxygen-induced retinopathy.

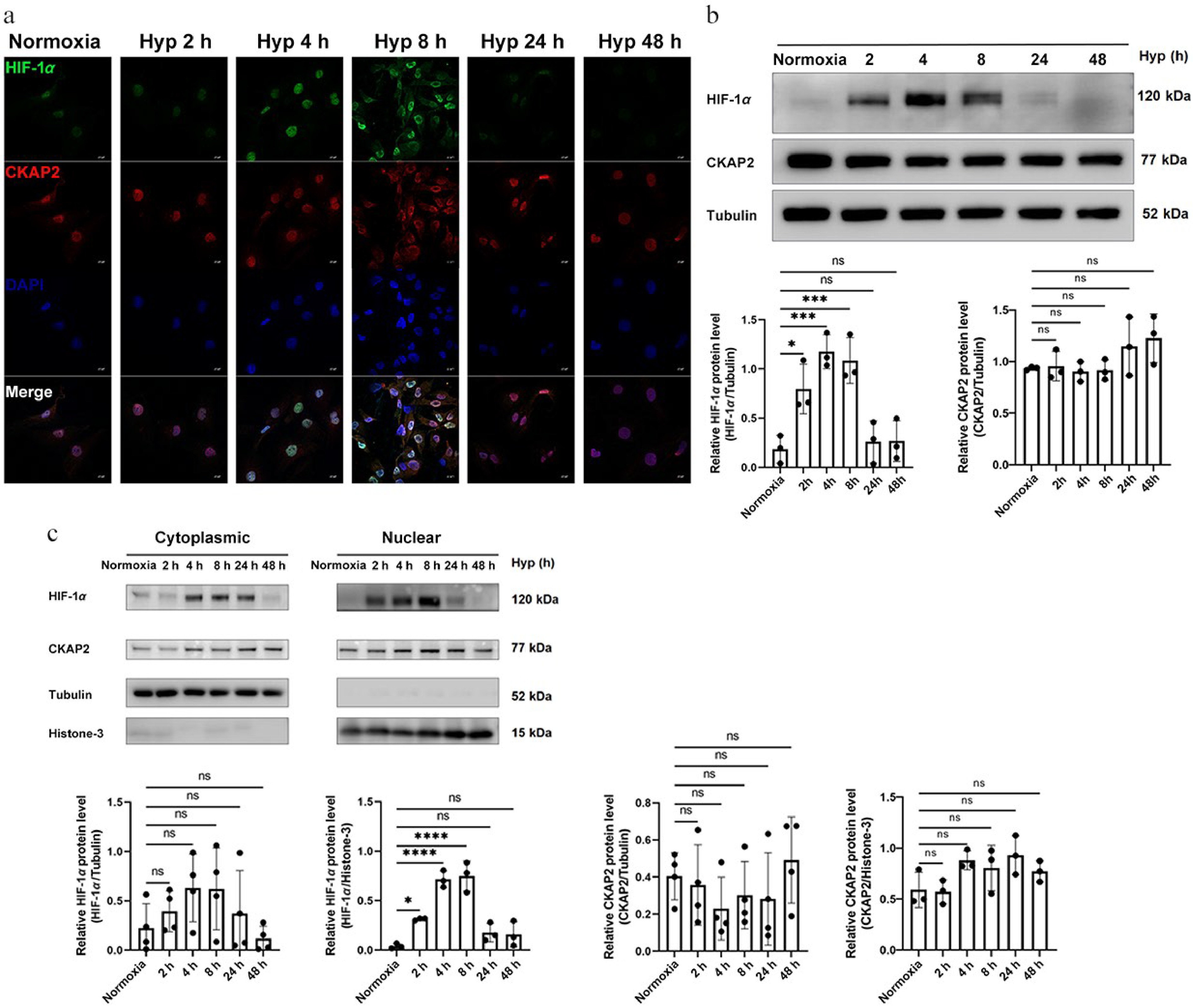

Dynamic expression of HIF-1α and CKAP2 in HRMECs exposed to hypoxic conditions

-

Next, the dynamic expression of HIF-1α and CKAP2 in HRMECs exposed to hypoxic conditions was investigated. Immunofluorescence staining revealed that HIF-1α expression was significantly upregulated at 2, 4, and 8 h under hypoxic conditions compared with controls, with the highest levels at 4 h. At the same time, it remained unchanged in morphology (Supplementary Fig. S2). In contrast, CKAP2 expression remained consistent across all time points (at 2, 4, 8, 24, and 48 h) under both control and hypoxic conditions (Fig. 4a). The Pearson's coefficient is used to estimate the correlation of green (HIF-1α) and red (CKAP2) signals. As a control, the red signal was rotated 180° out of phase, and then the same analysis was performed. Pearson's coefficient dropped significantly from 0.915 to 0.297 after the rotation, which confirms the colocalization of HIF-1α and CKAP2 in hypoxia-stimulated HRMECs. These observations were further supported by western blot analysis in total and nuclear-cytoplasmic fractionated proteins (Fig. 4b, c). These results revealed the differential regulation of HIF-1α and CKAP2 under hypoxia, with HIF-1α exhibiting dynamic upregulation in response to the early hypoxic stress, while CKAP2 levels remained stable. Furthermore, both proteins were observed to colocalize in HRMECs under hypoxic conditions, suggesting a potential interaction between HIF-1α and CKAP2 despite the lack of significant changes in CKAP2 expression.

Figure 4.

Time-dependent expression and localization of HIF-1α and CKAP2 under hypoxic conditions in HRMECs. (a) Representative immunofluorescence images showing the localization of HIF-1α (green) and CKAP2 (red) in HRMECs exposed to normoxia (control) or hypoxia for 2, 4, 8, 24, and 48 h. DAPI (blue) was used for nuclear staining. Scale bars: 20 µm. Images are representative of n = 3 independent experiments. (b) Western blot analysis of HIF-1α and CKAP2 protein levels in HRMECs exposed to hypoxia for 2, 4, 8, 24, and 48 h (n = 3). Quantitative analysis normalized to tubulin is shown below the blot. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3); comparisons among multiple time points were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by appropriate post hoc multiple-comparison tests (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; ns: not significant). (c) Subcellular localization of HIF-1α and CKAP2 proteins under hypoxia was assessed by western blot analysis of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions. Quantification is shown with normalization to tubulin (cytoplasmic fraction) and histone H3 (nuclear fraction). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3); comparisons between normoxia and hypoxia within each subcellular fraction were performed using unpaired two-tailed t-tests (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01). HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha; CKAP2, cytoskeleton-associated protein 2; HRMEC, human retinal microvascular endothelial cell; Hyp, hypoxia.

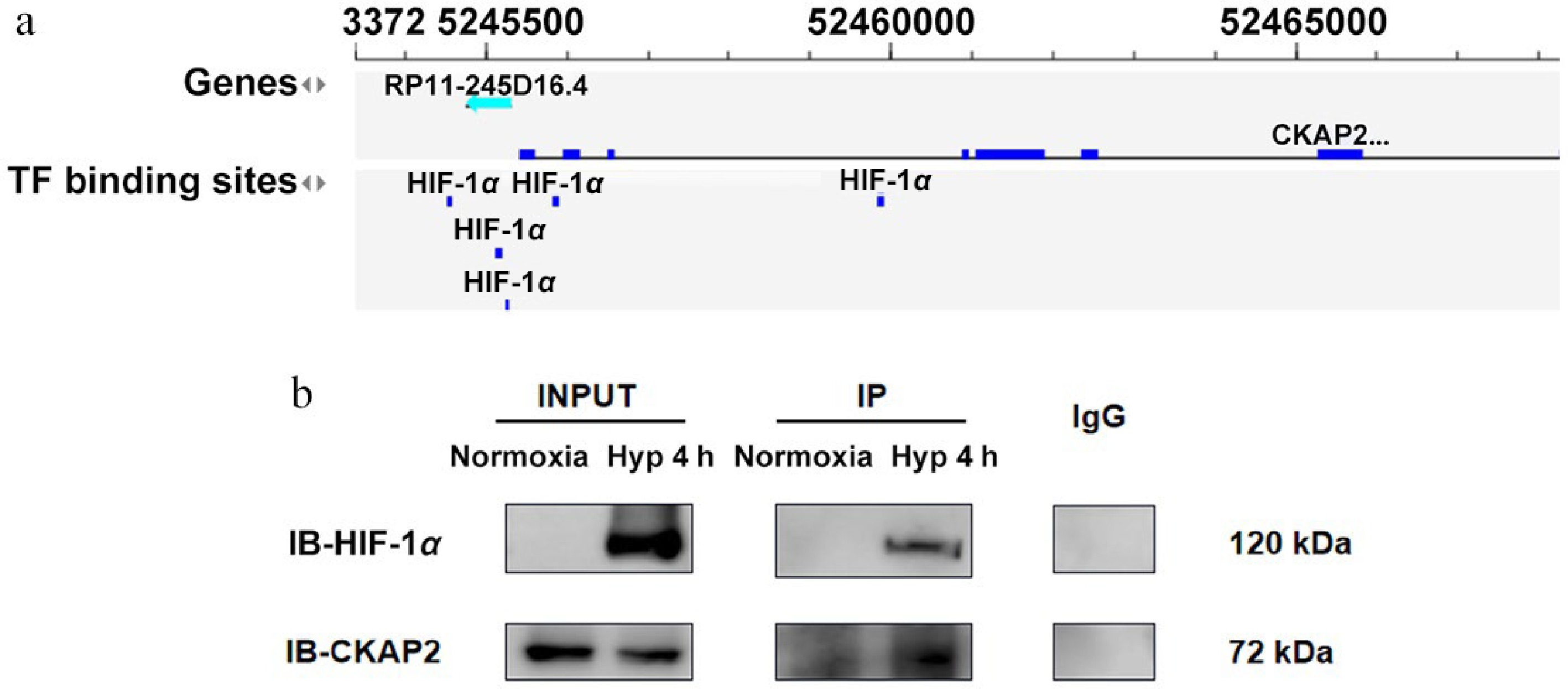

Association between HIF-1α and CKAP2 in HRMECs under control and hypoxic conditions

-

Bioinformatics analysis revealed that HIF-1α could bind within the CKAP2 gene locus (Fig. 5a), suggesting a possible association between HIF-1α and CKAP2. An IP assay was performed to explore this potential connection, and showed that HIF-1α and CKAP2 physically interacted under hypoxic conditions, as indicated by the detection of CKAP2 in the HIF-1α IP at 4 h (Fig. 5b). These results suggest that HIF-1α and CKAP2 interact under hypoxic conditions, supporting the hypothesis that CKAP2 is involved in the HIF-1α-mediated cellular response to hypoxia. This potential interaction may play a role in the regulation of HIF-1α expression or its function in HRMECs during hypoxic stress.

Figure 5.

Identification of CKAP2 and HIF-1α interaction under hypoxic conditions in HRMECs. (a) Bioinformatics analysis indicating TF binding sites for HIF-1α in the CKAP2 genomic locus. (b) Co-immunoprecipitation analysis showing the interaction between HIF-1α and CKAP2 in HRMECs under normoxic and hypoxic conditions (at 4 h). Blots are representative of n = 3 independent experiments; no formal statistical tests were performed. HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha; CKAP2, cytoskeleton-associated protein 2; TF, transcription factor; HRMEC, human retinal microvascular endothelial cell; IB, immunoblot.

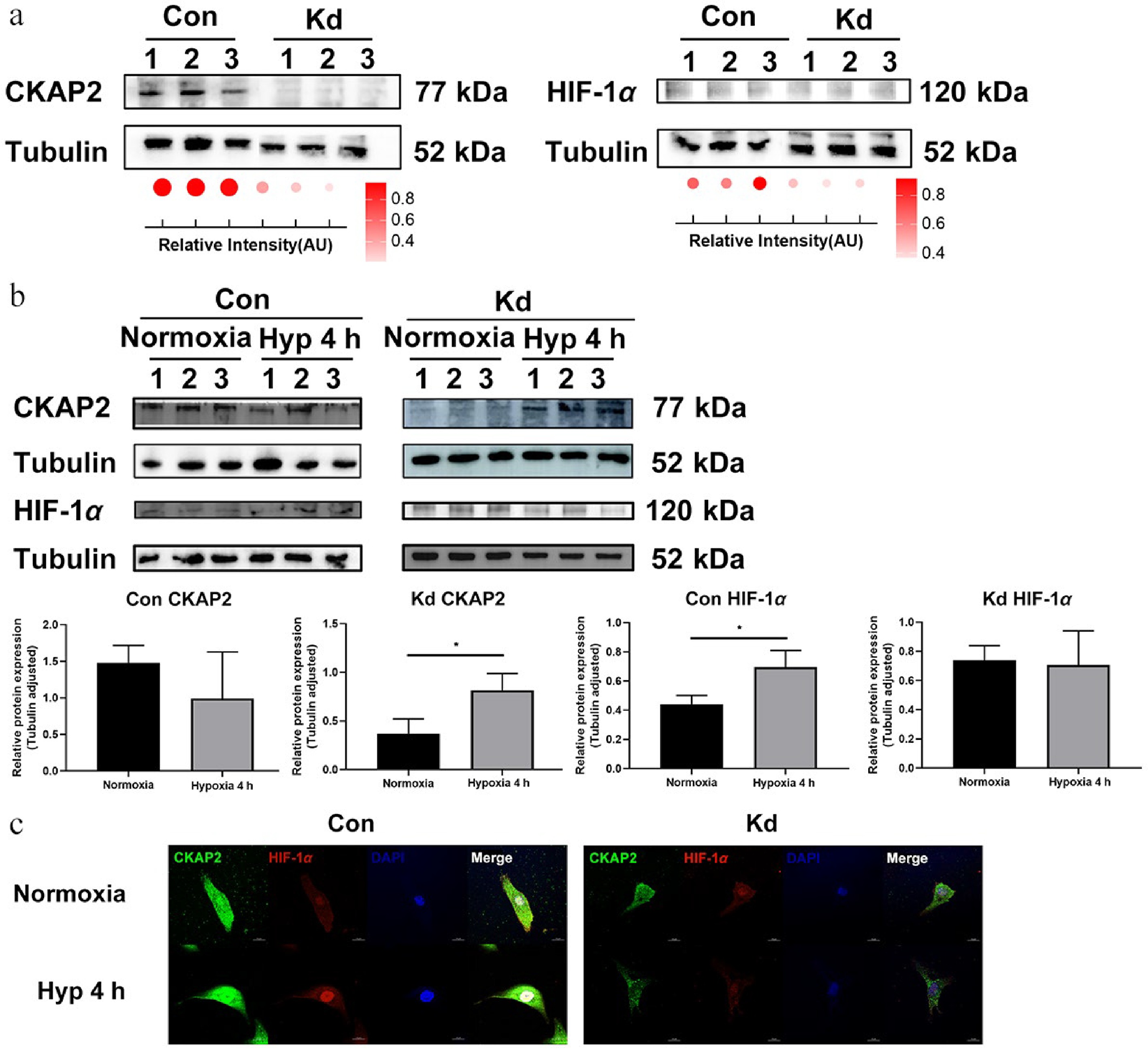

Effects of CKAP2 knockdown on HIF-1α and CKAP2 expression under hypoxic conditions

-

To investigate the role of CKAP2 in regulating hypoxia-induced responses, protein expression analysis of CKAP2 and HIF-1α was performed after CKAP2 knockdown (Kd) under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. As expected, CKAP2 expression was markedly reduced in the knockdown group compared with the control group, confirming the efficiency of gene silencing (Fig. 6a, left). A concurrent reduction in HIF-1α protein expression was observed in CKAP2-deficient cells (Fig. 6a, right).

Figure 6.

Effects of Ckap2 knockdown on HIF-1α expression under hypoxic conditions in HRMECs. (a) Western blot analysis of CKAP2 and HIF-1α protein levels in Ckap2 Kd and Con HRMECs under normoxic conditions. Tubulin served as a loading control. Quantification of band intensities is represented by dot plots below, indicating relative signal intensity normalized to tubulin. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3); comparisons between Con and Kd groups were performed using unpaired two-tailed t-tests. (b) Time-course western blot analysis of CKAP2 and HIF-1α protein expression in Con HRMECs (left panel) and Ckap2 Kd HRMECs (right panel) under hypoxic conditions (at 4 h). From bottom left to right: CKAP2 expression in the Con group, CKAP2 expression in the Kd group, HIF-1α expression in the Con group, and HIF-1α expression in the Kd group. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3); comparisons among multiple time points within each group were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by appropriate post hoc multiple-comparison tests (* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001). Quantitative data normalized to tubulin are shown below. (c) Immunofluorescence imaging of CKAP2 (green) and HIF-1α (red) in Ckap2 Kd and Con HRMECs under normoxia and hypoxia (at 4 h). DAPI (blue) was used to stain nuclei. CKAP2, cytoskeleton-associated protein 2; HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha; HRMEC, human retinal microvascular endothelial cell; Con, control; Kd, knockdown; Hyp, hypoxia. Scale bar: 20 µm. Images are representative of n = 3 independent experiments. For presentation, brightness and contrast were adjusted uniformly across all images within each channel to improve visualization of CKAP2–HIF-1α colocalization while maintaining data integrity.

Hypoxic treatment revealed that HIF-1α expression was significantly elevated at 4 h of hypoxia in the control group, but there was no significant change in the knockdown group (Fig. 6b, c). These results suggest that CKAP2 knockdown could influence the regulation of HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions, implying a complex interplay in the cellular response to hypoxia.

-

In this study, the expression and potential relationship of CKAP2 and HIF-1α in the context of hypoxia-induced retinal neovascularization were explored. CKAP2 and HIF-1α exhibited distinct complementary expression patterns and a potential interaction under hypoxia, providing new insights into their involvement in the hypoxia-driven pathogenesis of ischemic retinopathy.

Reanalysis of scRNA-seq data from the OIR model provided valuable insights into the spatial and temporal expression of CKAP2 and HIF-1α in different retinal cell types[15]. CKAP2 was predominantly expressed in endothelial cells, particularly in stalk cells, which were critical for angiogenesis during hypoxia[21]. Previous study found that CKAP2 is involved in the pathogenesis of PDR and regulated by VEGF and p53 under high-glucose conditions[7], suggesting its role as a pro-angiogenic factor. In contrast, HIF-1α is more broadly expressed, with particularly high expression in retinal neurons. These findings suggest that CKAP2 and HIF-1α have complementary roles in retinal neovascularization, with CKAP2 acting more specifically in endothelial cells and HIF-1α serving as a broader regulator of hypoxic responses across retinal cell types.

Developmental-stage analysis of CKAP2 and HIF-1α expression in the OIR model demonstrated that CKAP2 expression was significantly upregulated on P17 and P22, stages coinciding with the peak pathological angiogenesis and angiogenesis remodeling phase[20,22], which supported the hypothesis that CKAP2 plays a crucial role in retinal vascular development. In contrast, HIF-1α expression was elevated on P12, corresponding to early stages of retinal ischemia[23], which was in line with the reported role of HIF-1α in promoting neovascularization during ischemic conditions. These results suggest that both CKAP2 and HIF-1α are key players in the hypoxia-induced retinal neovascularization observed in ischemic retinopathy.

HIF-1α expression was strongly upregulated at early time points (at 2, 4, and 8 h) in HRMECs and underwent nuclear translocation in response to hypoxia, consistent with its established role as a master regulator of hypoxic signaling[24,25]. Interestingly, CKAP2 expression remained relatively stable in HRMECs under hypoxic conditions, which is different from the reports of upregulated expression of CKAP2 in various malignant tumors[26]. These findings suggest that HIF-1α is dynamically regulated under hypoxic stress, while CKAP2 level is less responsive to short-term hypoxia in retinal vascular endothelial cells.

Importantly, a physical interaction between CKAP2 and HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions was identified, as demonstrated by immunofluorescence staining and IP assays. Furthermore, we observed that CKAP2 and HIF-1α were predominantly colocalized in the nucleus under hypoxia, implying a potential functional interaction in the regulation of HIF-1α activity. Consistent with these findings, nuclear–cytoplasmic fractionation (Fig. 4c) showed that CKAP2 is not restricted to the cytoplasmic/microtubule compartment, but is also clearly detectable in the nuclear fraction under hypoxic conditions. This nuclear pool of CKAP2 is well positioned to participate in HIF-1α-related regulatory processes, for example, by stabilizing HIF-1α–containing transcriptional complexes on chromatin, modulating the assembly of co-activators or co-repressors at HIF-1 target promoters, or influencing local chromatin architecture to facilitate transcription. The effects of Ckap2 knockdown on HIF-1α expression and nuclear translocation provided further evidence of this interaction. Results showed that Ckap2 knockdown attenuated HIF-1α upregulation in response to short-term hypoxia, suggesting that CKAP2 might serve as a stabilizing factor for HIF-1α under stress conditions, consequently affecting cellular adaptation to hypoxic stress in the retina. The precise molecular mechanisms underlying this regulation require further elucidation. Nevertheless, several plausible mechanisms may explain how CKAP2 contributes to HIF-1α stability. First, CKAP2 is a microtubule-associated/spindle protein, and may act as a scaffolding adaptor that facilitates HIF-1α accumulation in the nucleus or protects it from cytoplasmic turnover, thereby prolonging its half-life under hypoxia. Second, CKAP2 may indirectly modulate the proteasomal degradation axis of HIF-1α. Under normoxia, HIF-1α is hydroxylated and targeted by the VHL-E3 ligase complex for ubiquitin-proteasome degradation[27]; CKAP2 deficiency might enhance this pathway or impair hypoxia-driven suppression of degradation, leading to reduced HIF-1α protein. Third, given that HIF-1α can bind within the CKAP2 genomic locus, CKAP2 might participate in a transcriptional co-regulatory loop, stabilizing HIF-1α through chromatin or transcription-complex organization. These possibilities remain speculative and warrant direct testing in future studies.

Furthermore, observation of a rebound in CKAP2 expression at early time points under hypoxia in the knockdown group implies a potential compensatory mechanism: cells may activate alternative pathways to cope with sustained stress. From the perspective of endothelial stress adaptation, hypoxia can trigger rapid survival-oriented feedback programs. The transient CKAP2 rebound may reflect stress-induced re-entry into proliferative/repair states or cytoskeletal remodeling that is required for endothelial resilience. In parallel, hypoxia may activate multiple transcriptional and signaling pathways (e.g., ER stress-UPR, HIF-2α, NF-κB, Nrf2, FOXO)[28−32], which could converge on cell-cycle or microtubule-regulatory modules and partially restore CKAP2 expression despite initial knockdown. Alternatively, the rebound could also stem from a time-dependent reduction of siRNA/shRNA efficacy under hypoxic stress, as hypoxia may alter transfection efficiency, RNA-induced silencing complex activity, or cell-cycle dynamics, thereby allowing partial recovery of CKAP2 levels. Although these explanations cannot be distinguished with the current dataset, the rebound phenomenon itself suggests that CKAP2 is involved in a hypoxia-responsive adaptive network in endothelial cells. Importantly, this reciprocal regulation underscores a complex and multilevel interaction in which CKAP2 may influence HIF-1α stability and activity, thereby affecting cellular adaptation to hypoxic stress in the retina. Although the exact molecular mechanisms remain to be elucidated, CKAP2 may act as a scaffold protein[33] to modulate the localization or activity of HIF-1α in hypoxic endothelial cells.

These findings are consistent with previous studies showing the involvement of HIF-1α in hypoxia-induced angiogenesis and the regulation of pro-angiogenic factors, such as VEGF[34,35]. The observed association between CKAP2 and HIF-1α suggests that CKAP2 may play a complementary role in modulating the hypoxic response, potentially influencing endothelial proliferation and neovascularization. Mechanistically, HIF-1α has been shown to interact with DLEU1 to activate CKAP2 transcription, enhancing malignancy in breast cancer[10]. Given the importance of pathological neovascularization in ischemic retinopathy, CKAP2 may represent a novel therapeutic target for mitigating disease progression.

Although this study yields several potentially significant findings, several limitations warrant consideration. First, despite results indicating a functional relationship between CKAP2 and HIF-1α, the precise molecular mechanisms underlying their interaction remain unclear. Further studies employing MicroScale Thermophoresis or Surface Plasmon Resonance are necessary to prove physical interaction. Second, although CKAP2 knockdown is known to affect HIF-1α localization, it is unclear whether it directly or indirectly, the latter by mediation through other signaling pathways, affects localization. Investigating these pathways is crucial to understanding the broader regulatory network. Moreover, the effect of CKAP2 overexpression on HIF-1α expression. Finally, in vivo validation in OIR models was not performed, which was essential for confirming the translational relevance of these findings.

In conclusion, this study provides new insights into the regulatory roles of CKAP2 and HIF-1α in hypoxic retinal vascular endothelial cells, highlighting their potential interplay in the pathogenesis of ischemic retinopathy. The mechanism underlying CKAP2 and HIF-1α interaction needs to be further explored to support the development of novel therapeutic strategies for this disease.

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos 82171072, 82301246).

-

This study was conducted following the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (Approval No. KY-Z-2021-571-01, September 17, 2021). The research followed the 'Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement' principles to minimize harm to animals. This study involved the use of established human cell lines. The human retinal microvascular endothelial cells (HRMECs) used in this research were purchased from a commercial supplier (Bioesn Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) and were used in accordance with institutional and national ethical standards. These cell lines have been previously validated and are widely used in retinal vascular research. No primary human tissues or samples were collected, and no new human subjects were involved in this study.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Liu J, Meng Q; methodology: Zhu H, Wu G, Wu X, Chen X, Liao S, Li F, Lyu Z; investigation: Liu J, Cheng Z, Meng Q, Lyu Z; data analysis: Huang Y; validation: Liu J, Cheng Z, Zhu H, Wu G, Wu X, Chen X, Liao S, Li F, Lyu Z, Meng Q; draft manuscript preparation: Liu J; writing−review and editing: Cheng Z, Huang Y, Meng Q; funding acquisition: Meng Q. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Junbin Liu, Zhixing Cheng

- Supplementary Table S1 Antibodies for western blot analysis and immunofluorescence.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Retinal vascular changes in the OIR mouse model at different developmental stages. Representative flat-mounted retinal images from control and OIR mice on postnatal days (P) 12, 14, 17, and 22. Retinas were stained with FITC (green) to visualize vasculature and IB4-Alexa Fluor 594 (red) to highlight endothelial cells. Merged images show vascular architecture and remodeling. Compared with controls, OIR retinas exhibited significant vascular disruption and abnormal neovascular tufts beginning on P14, with peak pathological angiogenesis observed on P17, followed by partial vascular regression or remodeling on P22. Scale bar: 500 μm. OIR, oxygen-induced retinopathy.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 HRMECs morphology remains unchanged under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. Immunofluorescence staining of CD31 (red) and DAPI (blue) in HRMECs cultured under normoxia or subjected to 4 hours of hypoxia (Hyp 4h). Scale bars: 20μm. Merged images show intact endothelial morphology with no significant structural alterations following short-term hypoxic exposure. HRMEC, human retinal microvascular endothelial cell.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu J, Cheng Z, Huang Y, Zhu H, Wu G, et al. 2026. The association between CKAP2 and HIF-1α in retinal neovascularization under hypoxic conditions. Visual Neuroscience 43: e004 doi: 10.48130/vns-0026-0002

The association between CKAP2 and HIF-1α in retinal neovascularization under hypoxic conditions

- Received: 23 September 2025

- Revised: 01 December 2025

- Accepted: 09 December 2025

- Published online: 28 January 2026

Abstract: This study aimed to explore the expression patterns and pathological roles between cytoskeleton-associated protein 2 (CKAP2) and hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) under hypoxic conditions, both in vitro and in vivo. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data from an oxygen-induced retinopathy (OIR) model were analyzed to evaluate cell-type-specific expression of CKAP2 and HIF-1α. Protein expression, localization, and potential interaction of CKAP2 and HIF-1α were assessed in hypoxia-stimulated human retinal microvascular endothelial cells (HRMECs). Knockdown of Ckap2 was further employed to examine its effect on HIF-1α signaling. scRNA-seq analysis showed that Ckap2 was notably upregulated in endothelial and stalk cells, whereas Hif-1α was predominantly elevated in retinal neurons. In OIR mice, CKAP2 expression increased progressively at later time points (P17 and P22), contrasting with the early hypoxia-responsive upregulation of HIF-1α (P12). Under hypoxia in HRMECs, HIF-1α level increased rapidly, while CKAP2 expression remained stable. Immunoprecipitation confirmed an interaction between CKAP2 and HIF-1α. Ckap2 knockdown reduced HIF-1α expression under normoxia and limited its induction under hypoxia, implying CKAP2 may contribute to HIF-1α stability and the adaptive cellular response to hypoxia. These findings highlight a functionally significant correlation between CKAP2 and HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions, providing new insights into their cooperative role in ischemic retinopathy.

-

Key words:

- CKAP2 /

- HIF-1α /

- Hypoxia /

- Endothelial cells /

- Ischemic retinopathy