-

Apple is the most economically important tree fruit crop in the UK, when dessert, culinary, and cider apples are considered. Commercial trees comprise two genotypes (rootstock and scion), and are clonally propagated by grafting the latter (fruiting cultivar) onto the former. Establishment of young trees in replant orchards may potentially encounter poor establishment, a well-known problem worldwide[1], commonly known as Apple Replant Disease (ARD). ARD symptoms can manifest within three months of replanting and include stunting and shortened internodes aboveground, root tip necrosis, and reduced root biomass. Although the growth rates of surviving trees are similar to those of unaffected trees, they start bearing fruit some 2–3 years later, and yields are reduced by up to ~60% for the duration of the tree's commercial life[2,3]. ARD in dessert and cider apple production (including in the nursery) represents a considerable financial risk to the industry.

Recently, the application of molecular methods has led to the emerging consensus that ARD is a disease complex, primarily caused by a consortium of microorganisms including fungi (Ascomycota and Basidiomycota) and fungus-like eukaryotes (Oomycota)[1]. Although the relative dominance of all contributing pathogenic species may vary greatly from site to site, four principal genera (Cylindrocarpon, Rhizoctonia, Phytophthora, and Pythium) are typically present. In China, ARD is primarily attributed to Fusarium proliferatum[4]. These genera contain well-known soil-borne pathogenic species responsible for causing many plant diseases. Root lesions caused by nematodes, such as Pratylenchus penetrans, can also exacerbate ARD by facilitating pathogen entry into the host's root tissues. In an experimental study, controlling all three ARD components (oomycetes, fungi, and nematodes) by three selected biocides (oxamyl granules against nematodes; fenamidone + fosetyl-aluminium against oomycete; and prochloraz and tolclofos-methyl against ascomycete and basidiomycete fungi) led to the best root development[5]. Effective control of soil-borne diseases is difficult for both technical and logistical reasons, even for those diseases caused by a single agent. ARD inoculum may remain viable in soil in the absence of host roots for up to 20 years[6]. Replanting trees with rootstocks that are genetically different from the previous one can reduce ARD development[7], indicating partial genetic control of tolerance to ARD. However, in adopting this strategy, the extent of genetic relationships among rootstock genotypes needs to be considered. Other factors, such as soil properties and phytoalexin biosynthesis, can also affect ARD development[8,9].

Current ARD management strategies are generally based on the principles of exclusion (crop rotation and tree placement within an orchard), and soil treatment. ARD shows a limited spread in soil, and young trees are less affected by ARD in orchards where trees are replanted in the former grass aisles[7,10]. Avoiding the use of genetically related rootstocks at the same site can also lead to a significant reduction in ARD[7]. However, planting in the alleyway and rotating rootstocks have rarely been practised. Exclusion of apple orchards from a site for 5–8 years (rotation) is commonly recommended to reduce disease severity in replant sites. However, in the long term, both strategies are impractical for perennial crops[11] on a commercial scale, and economically unattractive to both growers and nurseries. Traditional broad-spectrum fumigants have been banned, or their use is severely restricted. Alternative strategies for managing ARD include modification of indigenous soil microbial communities[12] and orchard ground cover management[13]. There is evidence that by altering the microbial community in ARD soil, in terms of both alpha- and beta-diversity, this impacts the normal development of apple rhizosphere and thus the rhizoplane microbiota, and concurrent development of ARD symptoms[14]. However, other studies indicated that ARD development is more likely to be associated with specific beneficial or pathogenic microbes than with the community-level features[15]. Biofumigants, especially Brassicaceae seed meals[1,16], appear to offer reproducible reductions in ARD, but their principal market as biofuels and oils makes them uneconomical as pre-plant treatments for horticultural land.

There is an urgent need for testing the individual and combined use of alternative strategies against ARD, using commercially available products to support the immediate adoption of these strategies in commercial apple production. An extensive orchard study was conducted to assess the effects of soil amendments with commercially available products in the UK at planting on apple establishment and subsequent tree growth in a replant orchard. Specifically, an experiment with a 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design was carried out to study the main effects of the three types of microbial amendments, and their interactions on tree establishment following replanting: (1) a formulated product with a single-strain arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF); (2) two strains of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR); and (3) two microbial biocontrol agents (BCAs)—one bacterial BCA and one fungal BCA. In addition, two further products were also included in the experiment: one was a formulated product with five AMF species/strains, and the other was a Brassicaceae seed meal product. These two products were included for assessing whether they could improve tree establishment when compared to the untreated control, and for comparing the performance of the single-strain AMF product with the five-strain/species mix product.

-

The main objective of this study was to assess the effect of commercially available soil amendments in the UK on tree establishment following replanting in a replant orchard and subsequent tree growth. As such, standard commercial practices to improve fruit production were not applied, such as removing blossoms immediately during the first few years after planting and pruning trees. Trees were left unpruned so that unrestricted growth could be measured following the soil management treatment. The focus here was to assess tree growth (primarily expressed in terms of the girth expansion over time) since better tree establishment is a prerequisite for profitable fruit production.

Location and tree maintenance

-

The trial was established on the site of an old apple orchard (51°17′12.78″ N, 0°27′55.80″ E), planted in the late 1990s, to induce ARD development; the soil pH was ~7.0 with a sandy loam texture (tested by NRM, part of Cawood Scientific Ltd, using analytical methods as described in the UK government department Defra Reference Book 427). Prior to the previous apple crop (planted in the late 1990s), strawberries were grown at the location for many years. The old apple orchard was grubbed in March 2020 and replanted in April 2020; trees of cultivar Gala grafted to M9 were used. Tree girth (5 cm above the graft union) was measured at the time of planting. Trees were planted in two blocks; each block previously had 12 × 12 trees (12 rows, each with 12 trees). Within each block, the central 10 × 10 positions for a Latin square design was used as there were 10 treatments in total (Table 1).

Table 1. Details of individual treatments applied as soil amendment at the time of apple tree planting at East Malling in April 2020. The first eight treatments form the 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design: single AMF strain (yes, no) × biocontrol agents (yes, no), and PGPR (yes, no).

Treatment Name Components (note) Volume/amount per tree 1 (A) East Malling (EM) AMF Diversispora sp. 25 ml (~12,500 propagules per tree) 2 (B) Biocontrol agents Trichoderma harzianum T-22 (Trianum P, Koppert), B. subtilis (Serenade, Bayer) 100 ml water, 0.1 g Trianum, 2 ml Serenade 3 (C) PGPR Azospirillum brassilense sp245*, Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus Pal5 100 ml PGPR mix (~108 CFU per tree) 4 A + B 25 ml Diversispora + 100 ml water 0.1 g Trianum, 2 ml Serenade 5 A + C 25 ml Diversispora + 100 ml PGPR mix 6 B + C 100 ml PGPR mix, 0.1 g Trianum, 2 ml Serenade 7 A + B + C 25 ml Diversispora + 100 ml PGPR mix, 0.1 g Trianum, 2 ml Serenade 8 Nothing Control treatment 9 Biofence Brassica seed meal containing high N 300 g (2 weeks before planting) 10 Mixed AMF Five species mix (Funeliformis geosporum, F. mosseae, Claroideoglomus claroideum, Rhizophagus Irregularis, Glomus microagregatum) 25 ml (~12,500 propagules per tree) * This strain was identified as Paenibacillus sp. through the 16S sequences obtained. Foliar sprays were applied for nutrition (NPK, PK, Ca, Mg, Zn, B, and micronutrients all applied during the trial depending on orchard requirements throughout the season) as well as pest and foliar disease (predominantly products for the control of scab and powdery mildew) control throughout the growing seasons as per standard practise in UK commercial orchards. Weeds were suppressed by herbicide (propyzamide or a 2,4-D and glyphosate mix) sprays to the strips below the trees once or twice a year, and occasional strimming or hand weeding at the base of trees was carried out if necessary. Crop husbandry was the same for all trees and products applied at on-label rates. The trees were not irrigated and, therefore, no nutrient was applied to the base of the tree by fertigation. The trees were not pruned, and fruitlets were not thinned beyond natural June-drop.

Treatments and application

-

There was a total of 10 treatments, eight of which were from the full factorial design of three factors, each with two levels: (1) a single-strain AMF of Diversispora sp. (yes, no); (2) two BCAs (yes, no); and (3) PGPR (yes, no). In addition, two more treatments were included: an AMF product (RootgrowTM) with a five-strain (species) mix, and Brassicaceae (Brassica carinata) seed pellets (Biofence). Table 1 gives the details of each of the ten treatments. All AMF and PGPR products were commercially available and supplied directly from the manufacturer PlantWorks Ltd. (Sittingbourne, UK). The two BCAs (formulated Trichoderma harzianum and Bacillus subtilis commercial products) were purchased commercially from distributors in the UK. Biofence was supplied by Tozer Seeds (Cobham, UK).

Tree stations allocated to the Biofence treatment were amended with Biofence 14 d before planting to avoid tree toxicity. Prior to planting and treatment, 400 ml of water was applied over the roots of every tree. AMF was applied directly with a scoop onto the tree roots in the planting hole. For treatments with one or more liquid components (Table 1), products were made into a total volume of 100 ml per tree, and poured around the root system when the tree was placed into the planting hole. Weeds/grasses around the planting holes were removed to avoid competition. For treatments including liquid products (namely, BCAs or PGPR), the liquid product(s) were reapplied to those trees allocated to the relevant treatments in every other row of both blocks in early May 2022, and again in late April 2023. Thus, half the trees for these treatments were inoculated just once at planting, and the other half were reinoculated twice. Water was applied to all trees in these rows, including those four treatments that were not reinoculated, immediately before re-inoculation, 1 L per tree in 2022, and 0.5 L per tree in 2023, as the ground was much wetter in 2023 than in 2022. BCAs and/or PGPR were applied, and then a further ca. 1 L was applied to all trees in rows, reinoculated ca. 30 mins after inoculation in 2022. In 2023, it rained after reinoculation was complete, and ca. 8.8 ml of rain fell in the next 6 h. In both years, re-inoculation was carried out on overcast days.

Assessment

-

Tree girth (ca. 20 cm above the graft union) was measured annually in the spring period of 2021–2024; in addition, the girth at 5 cm above the graft union was also measured in 2021 since the girth was measured at this position at planting in 2020. Fruit was harvested in the autumn of 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024. In addition to the total number of fruits and total weight per tree, fruits were also divided into two classes: ≥ 60 mm and < 60 mm.

In October 2023, the orchard was phenotyped by drone to estimate canopy cover area and tree height. Data collection and production of 3D point clouds and 2D orthomosaics was conducted following our previously published method[17]. In the trial, ground control point and height reference panels were used in accordance with recommended practices[18]. A low-cost drone (Mavic 2 Pro; DJI, Shenzhen, China) was used for imaging to ensure this imaging protocol can be easily adopted by others. A specific mission plan was designed for tree-level imaging. Flights were conducted at 15 m altitude, with 80% image overlap, in a double grid pattern and a gimbal angle of −45° to capture the whole canopy. 3D point clouds and 2D orthomosaics containing morphological, colour, and textural signals of plants were generated from the drone-collected raw images using the Pix4D Mapper software (Pix4D, Switzerland).

Data analysis

Estimation of tree size from drone images

-

The 3D point clouds and 2D orthomosaics used in this study were generated from the drone-collected image series using the Pix4DMapper software (Pix4D, Lausanne, Switzerland), with parameters tailored for apple orchard phenotyping, including: (1) initial data processing to set up key points, generate quality report, and match images based on geometrically verified information; (2) the generation of 3D point clouds, for which users needed to set up image scale, the minimum number of features needed to be matched between adjacent images, optimal 3D point density, and matching window with processing areas; (3) exporting digital surface model (DSM) and 2D orthomosaics generated by the Pix4DMapper software, with terrain features such as slope removed in mapping area.

After data pre-processing, the AirMeasurer high-throughput phenotyping platform[17] was then applied to automate the generation of a 3D canopy height map (CHM) to represent the apple orchard using the GSP-tagged 2D orthomosaics and 3D point clouds. Tree-scale 3D point clouds were used to provide tree-level 2D canopy projections and canopy height measures. Utilising the 3D CHM produced at the half-inch green or tight cluster stages, an analytic pipeline was established to automate the segment apple trees in the orchard, including: (1) a 2D projection of the CHM from an overhead perspective, producing a projection image to present height signals using greyscale values (0 to 255; the brighter a pixel, the higher the point); (2) using the Local Auto Threshold[19] and morphological open algorithms[20] to identify tree-level region of interest (ROI), resulting in GPS-tagged tree-level masks; (3) 3D apple trees in the orchard were segmented according to the tree masks, with overlapped branches or unwanted canopy edges removed if they were outside the masks. Tree canopy signals within the tree-level ROIs were utilised to measure canopy height based on the top 5% tree signals (i.e. the top 5% brightest pixels), and projected canopy area using a convex hull[21] to enclose all the tree-level pixels.

Statistical analysis

-

Logarithmic transformation was applied to fruit weight, number of fruits, and the estimated canopy cover area before statistical analysis to reduce deviation of residual errors from a normal distribution. Preliminary analysis indicated that the re-inoculation of liquid inoculum did not significantly impact tree development and fruit production. Hence, it was not included in all subsequent analyses; it should, however, be noted that any re-inoculation effect is going to be captured in the row blocking factor and, hence, not in the residuals. Statistical analysis was divided into two parts: (1) analysis of the data from the 2 × 2 × 2 factorial designed study, and (2) comparison of selected four individual treatments (the two AMF only amendments: single or mix AMF strain product), Biofence amendment, and the untreated.

(1) Analysis of the 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design study. Variables that were measured at a single time point were first separately analysed, namely, annual girth data, canopy cover area and height (measured in October in 2023), and annual fruit production data (weight and counts). A linear mixed model framework was used to analyse the data in which the two directional blocking factors (row and column) were treated as random-effect factors, and the initial girth (5 cm above the graft union) at planting was used as a covariate. Then, longitudinal analysis of girth expansion and yield data were carried out. To analyse the girth expansion over seasons, the girth measurements at 20 cm above the graft union since spring 2021 were used; thus, there were four annual girth measurements—spring in each of the four years. A linear mixed model was used to analyse the effect of soil amendments on the annual girth expansion within the random intercept and slope modelling framework. In this analysis, individual trees were the subject. In addition, rows/columns were also included in the model as random-effect factors. The main question was to assess whether the main effect of amendment types and their interactions significantly affected the annual increase in girth, namely, the slope over time in the model (annual girth expansion rate). The treatment factors were assumed not to have affected the intercept since the original trees were randomly assigned to each treatment. A similar linear mixed-effect model was applied to the fruit data (weight and number of fruit) over the four seasons, except that year was treated as a fixed-effect factor instead of a continuous variable. Thus, the model only considered the main effects of treatment factors and their interactions on yield, ignoring their interactions with years. In all linear mixed model analysis, the statistical significance of treatment effects was tested in the framework of deviance comparisons among nested models.

(2) Comparing AMF and Biofence treatments. Similar analyses were applied to the four selected individual treatments: comparing ① two AMF only treatments (single or mixed strain) with the untreated control; and ② Biofence amendment with the untreated.

-

All trees established and survived, following planting, until 2023. In 2023, there were 13 dead trees, and a further 12 trees died during the 2024 season due to apple canker lesions on the trunk (resulting from latent infection that likely originated in the nursery). Of the 25 dead trees, there were two from the control treatment, five from the mixed-AMF treatment, and one from the Biofence treatment. The number of dead trees showed no relationship with AMF, PGPR, or BCA treatment.

Tree girth increased with time, along with an increasing variability in the tree expansion over time among trees (Supplementary Fig. S1). Correlation in girth among years was significant but generally decreased with increasing gaps in tree ages (Supplementary Table S1). For instance, Pearson correlation of the girth, at the height of 5 cm above graft union, in March 2020 (at planting) with the girth at 20 cm above graft union in the subsequent four years was 0.844, 0.668, 0.587, and 0.516, respectively, all highly significant (p < 0.001). The corresponding Spearman correlation was 0.841, 0.658, 0.576, and 0.484. The average tree girth at 20 cm above the graft union was 5.44, 6.03, 6.93, and 7.62 mm in March 2021–2024, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). The difference in girth between the lowest and greatest average treatment girth increased with time: from 5.28 to 5.61 mm in 2021, to from 7.21 to 8.07 mm in 2024 (Supplementary Table S2).

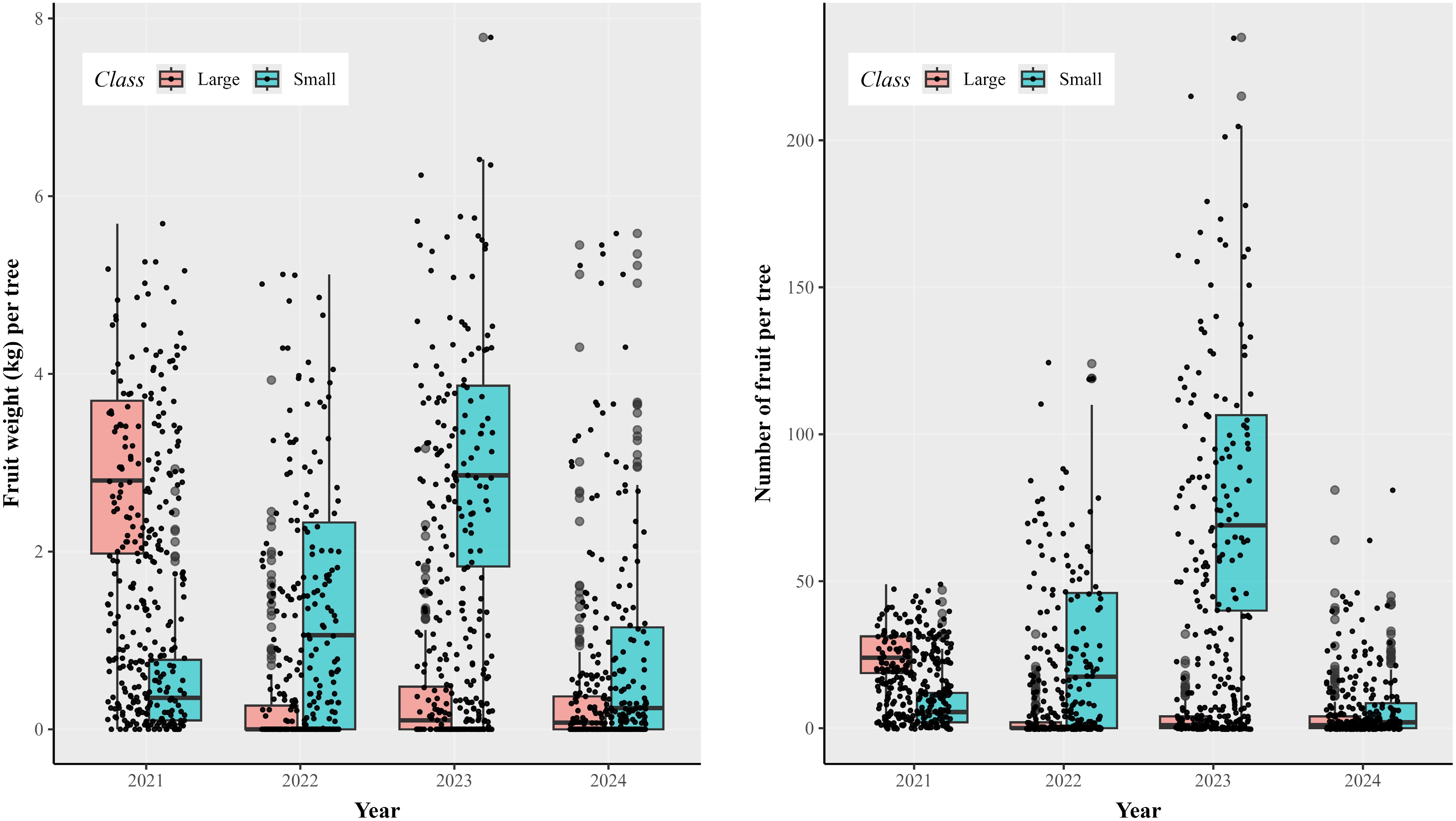

There were large differences in the number of fruit and their weight among the years (Fig. 1), and most fruit were small (< 60 mm in diameter) and unmarketable for all years except 2021. On average, there were 24.3, 2.6, 3.3, and 5.2 large fruits per tree in 2021, 2022, 2023, and 2024, respectively; the corresponding values for unmarketable (small) fruit were 8.4, 26.3, 76.8, and 6.2. The average total number and weight of either large fruit or all (both small and large) fruit did not vary much with treatments, relative to their standard errors (Supplementary Table S2). The correlation between estimated plant height and canopy area was 0.731 (p < 0.001). Correlation of the tree girth with both height and canopy area was small (< 0.29), albeit statistically significant for most correlation values (Supplementary Table S1). There were large variabilities in the estimated canopy cover area among individual trees, as indicated by the large differences in treatment averages, as well as by the large standard error in each treatment (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 1.

Boxplots of the weight (kg), and number of large (diameter ≥ 60 mm) and small (diameter < 60 mm) fruits on individual trees in each year. Trees of the apple cultivar Gala, grafted onto the M9 rootstock, were planted in April 2020 with soils amended with one of nine soil treatments in addition to an unamended control.

Analysis of the 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design experiment

Tree girth

-

Table 2 shows the results of linear mixed models when annual girth data were analysed separately, with the initial girth at planting as a covariate. Overall, amendment with single-strain AMF at planting led to increased girth for 2022, 2023, and 2024 (p < 0.05). Amending soils with BCAs led to a significant increase in girth only in 2023 (p < 0.05), and its main effect was close to statistical significance at p = 0.05 for 2022. For both the AMF and BCA amendments, their main effect increased with increasing time (Table 3). For instance, the main effect size of AMF amendment increased from 0.13 mm in 2021 to 0.36 mm in 2024.

Table 2. Analysis of deviance of nest linear mixed models to test for statistical significance of treatment effects on annual girth and plant height/canopy area measured in October 2023 in the 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design where trees of the apple cultivar Gala, grafted onto the M9 rootstock, were planted in April 2020 and soils amended with a single strain AMF (yes, no), biocontrol agents (BCAs) (yes, no), and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) (yes, no).

Terms Girth (20 cm above the graft union) Height Canopy Fruit weight and number 2021 2022 2023 2024 2021 2022 2023 2024 Weight Number Weight Number Weight Number Weight Number Base model† + AMF& 1.94 5.26* 5.46* 6.53* 7.55** 7.38** 1.47 1.20 2.94+ 3.13+ 0.80 0.74 0.71 0.18 + BCA 2.39 2.92+ 4.44* 1.66 3.29+ 1.07 3.14+ 2.13 0.65 1.20 0.17 0.72 0.98 1.23 + PGPR 0.36 0.55 0.26 0.27 0.01 0.09 1.30 0.42 0.01 0.01 0.41 0.25 0.06 0.01 + AMF : BCA 0.38 1.63 1.17 0.51 0.87 0.1 0.13 0.06 0.19 0.12 0.42 0.78 1.66 1.21 + PGPR : BCA 8.92** 3.58+ 4.18* 1.99 0.31 0.03 0.50 0.36 0.10 < 0.01 1.84 2.49 0.72 0.69 + AMF : PGPR 4.61* 3.56+ 3.3+ 5.64* 0.01 0.15 0.07 0.83 0.86 0.05 3.01+ 2.75+ 2.08 1.31 + AMF : PGPR : BCA 0.81 1.11 0.39 0.33 < 0.01 0.05 0.14 0.04 0.92 0.58 0.39 0.08 0.86 0.20 † Base model for the growth contains the fixed effects of intercept, random intercept for the two block factors (rows and columns), and girth 5 cm above the graft union measured at the planting time (April 2020) as a co-variate. & All terms have one degree of freedom. Tree girth 20 cm above the graft union and yield were assessed annually in 2021–2024. Statistical significance based on the Chi-square test in the nested linear mixed models at the level of 0.001, 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1 is indicated by ***, **, *, and +, respectively. Table 3. Individual factor level mean (± standard error) of annual tree girth, height, and canopy cover area (measured in October 2023), and total fruit weight and number over the period of 2021–2024 for three soil amendment product types in the 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design experiment: with or without single AMF strain (AMF), with or without biocontrol agents (BCAs), and with or without plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR).

Factor level Girth (mm, 20 cm above the graft union) Height (cm) Canopy cover area Total fruit yield Large fruit (≥ 60 mm) 2021 2022 2023 2024 Weight Number Weight Number Without AMF 5.39 ± 0.050 5.93 ± 0.061 6.8 ± 0.076 7.47 ± 0.093 68.6 ± 2.92 2968 ± 353.7 9.21 ± 0.352 145.4 ± 5.04 3.77 ± 0.223 35.1 ± 2.06 With AMF 5.52 ± 0.047 6.13 ± 0.055 7.07 ± 0.073 7.83 ± 0.091 80.2 ± 3.12 4293 ± 531.8 9.66 ± 0.346 159.6 ± 5.58 3.91 ± 0.207 35.7 ± 1.80 Without PGPR 5.45 ± 0.045 6.02 ± 0.061 6.92 ± 0.079 7.62 ± 0.100 74.3 ± 3.14 3645 ± 504.5 9.27 ± 0.331 152.1 ± 5.23 3.69 ± 0.211 34.4 ± 1.92 With PGPR 5.45 ± 0.052 6.04 ± 0.058 6.95 ± 0.073 7.67 ± 0.088 74.5 ± 3.05 3608 ± 406.5 9.60 ± 0.366 153.1 ± 5.52 3.98 ± 0.217 36.4 ± 1.95 Without BCA 5.40 ± 0.045 5.96 ± 0.060 6.82 ± 0.075 7.55 ± 0.097 70.6 ± 2.97 3369 ± 459.3 9.55 ± 0.364 146.7 ± 4.78 3.79 ± 0.23 35.1 ± 2.07 With BCA 5.50 ± 0.051 6.10 ± 0.058 7.05 ± 0.075 7.74 ± 0.091 77.9 ± 3.15 3866 ± 453.4 9.33 ± 0.335 158.3 ± 5.82 3.9 ± 0.199 35.7 ± 1.80 Trees of the apple cultivar Gala, grafted onto the M9 rootstock, were planted in April 2020 and soils amended with appropriate product(s). For each factor level, there were 80 trees. Although the main effects of amending soils with PGPR were not statistically significant, its interaction with AMF and BCAs was all significant or close to statistical significance at p = 0.05 except its interaction with BCAs in 2024 (Table 2). In all cases where there were significant interactions involving PGPR, amending soils with PGPR as well as AMF or BCAs led to reduced girth. For instance, linear mixed model analysis estimated that joint amendment with PGPR and BCAs led to an overall reduction of 0.193 (± 0.0638) mm in girth in 2021, and a corresponding reduction of 0.135 (± 0.0638) mm for combined use of PGPR and the single-strain AMF product.

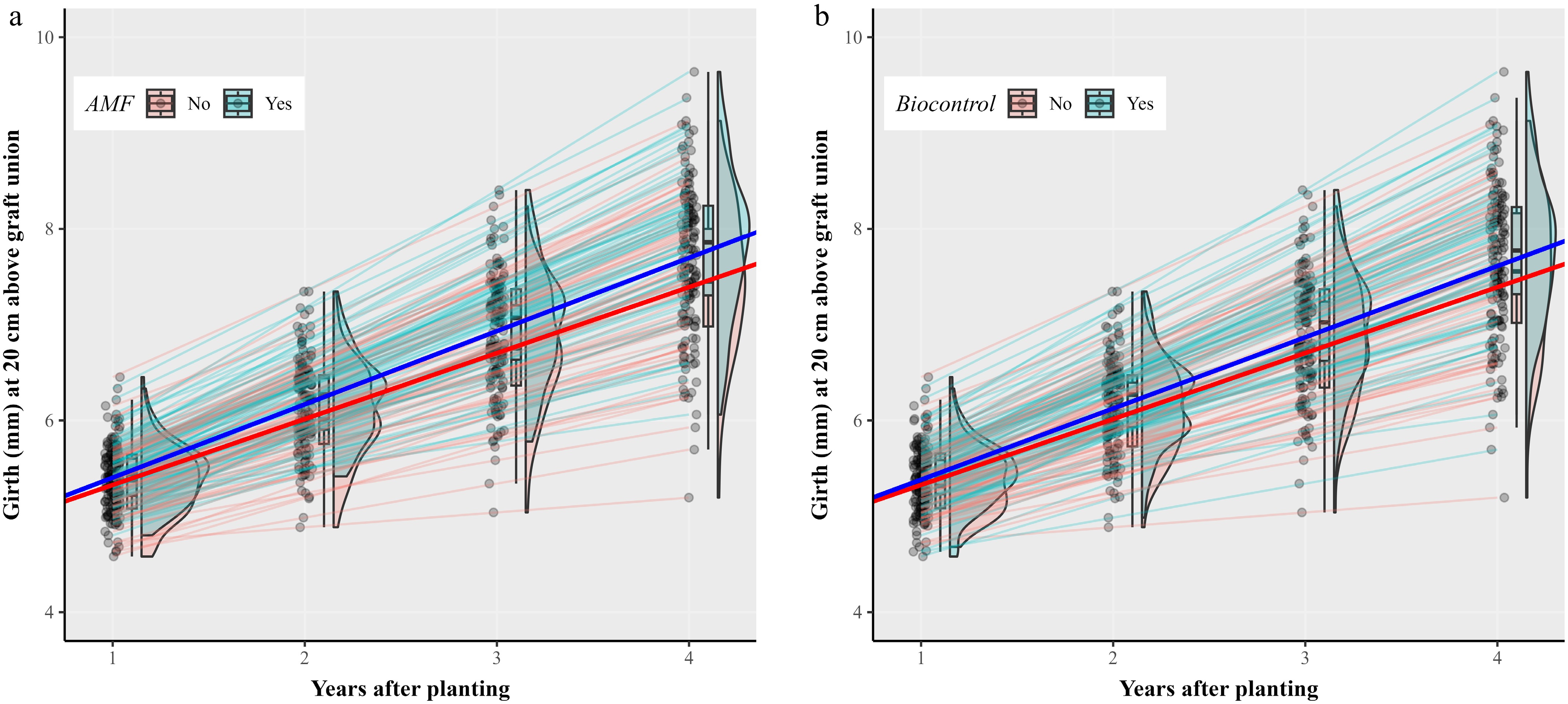

Linear mixed model analysis of the longitudinal girth data showed significant main effects of amendment with either single-strain AMF (p < 0.01), or BCAs (p < 0.05) (Table 4). The annual rate of girth expansion was 0.688 (mm/year) and 0.764 (mm/year) for trees without and with the single species AMF amendment, respectively (Fig. 2a), representing an 11.1% increase in the annual girth expansion rate. The AMF effect size is 0.076 mm with a confidence interval of 0.0223 to 0.1321. The annual girth expansion rate was 0.688 (mm/year), and 0.743 (mm/year) for trees without and with BCA amendment, respectively (Fig. 2b). The BCA effect size is 0.055 (confidence interval: 0.0007 to 0.1093). Amending soils with PGPR at planting time did not result in any significant impact on tree girth expansion. There were no significant interactions among the three factors in influencing girth expansion. Thus, on average, amending soils at planting with both AMF and BCAs led to an average increase of 18.3% in the annual girth expansion over the unamended.

Table 4. Analysis of deviance of nest linear mixed models to test for statistical significance of longitudinal treatment effects in the 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design where trees of the apple cultivar Gala, grafted onto the M9 rootstock, were planted in April 2020 and soils amended with a single strain AMF (yes, no), biocontrol agents (BCAs) (yes, no), and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) (yes, no).

Model Girth Fruit production Large fruit (≥ 60 mm) Total Weight Number Weight Number Base model† + AMF& 7.37** 0.35 0.63 0.93 1.59 + BCA 3.94* 0.11 2.18 0.8 0.93 + PGPR 0.07 0.42 0.13 < 0.01 0.24 + AMF : BCA 0.41 1.36 1.09 0.06 < 0.01 + PGPR : BCA 1.49 1.36 2.16 0.59 0.22 + AMF : PGPR 1.85 4.85* 5.1* 1.59 0.28 + AMF : PGPR : BCA < 0.01 1.12 0.67 0.21 0.06 † Base model for the growth contains the fixed effects of annual growth (slope) and intercept, and random intercept and slope for the two block factors (rows and columns), and individual trees. Base model for the yield contains the fixed intercept, random intercept for the two block factors (rows and columns), and individual trees, and the annual effect on the yield (i.e., years were treated as a factor instead of a continuous variable in the girth model. & For the girth, the treatment effect is on the annual expansion rate (slope); for the yield, the treatment effect was on the overall yield across years. All terms have one degree of freedom. Girth 20 cm above the graft union and yield were assessed annually in 2021–2024. Statistical significance based on the Chi-square test in the nested linear mixed models at the level of 0.001, 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1 is indicated by ***, **, *, and +, respectively.

Figure 2.

Fitted random intercept and coefficient models describing the girth increase over time of individual trees in relation to amendment with a single AMF strain or biocontrol agents (BCAs) at planting in a 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design of soil amendment (AMF [yes, no], BCA [yes, no] and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria [yes, no]). There were significant main effects of amending soils with AMF (p < 0.01) or BCA (p < 0.05), increasing the annual girth expansion rate (the thick blue and red lines represents the main effect). Thin lines are the fitted models for individual trees. The density plots show the annual girth distribution patterns of those trees with and without (a) AMF, or (b) BCA amendment. Trees of the apple cultivar Gala, grafted onto the M9 rootstock, were planted in April 2020.

Fruit production

-

Table 2 shows the results of linear mixed model analysis when fruit production was analysed separately for each year. There was an indication that amending soils with BCAs at planting increased the total weight of large fruits (p < 0.1) in 2021, increasing fruit weight from an average of 2.7 to 3.0 kg/tree. Similarly, AMF amendment appeared to have increased (p < 0.1) both the number and weight of large fruits in 2022: 3.1 vs 2.0, and 0.35 kg vs 0.23 kg per tree. There was also an indication of interactions between AMF and PGPR for both the weight and number of large fruits in 2023 (p < 0.1, Table 2)—joint amendment with AMF and PGPR led to reduced fruit production.

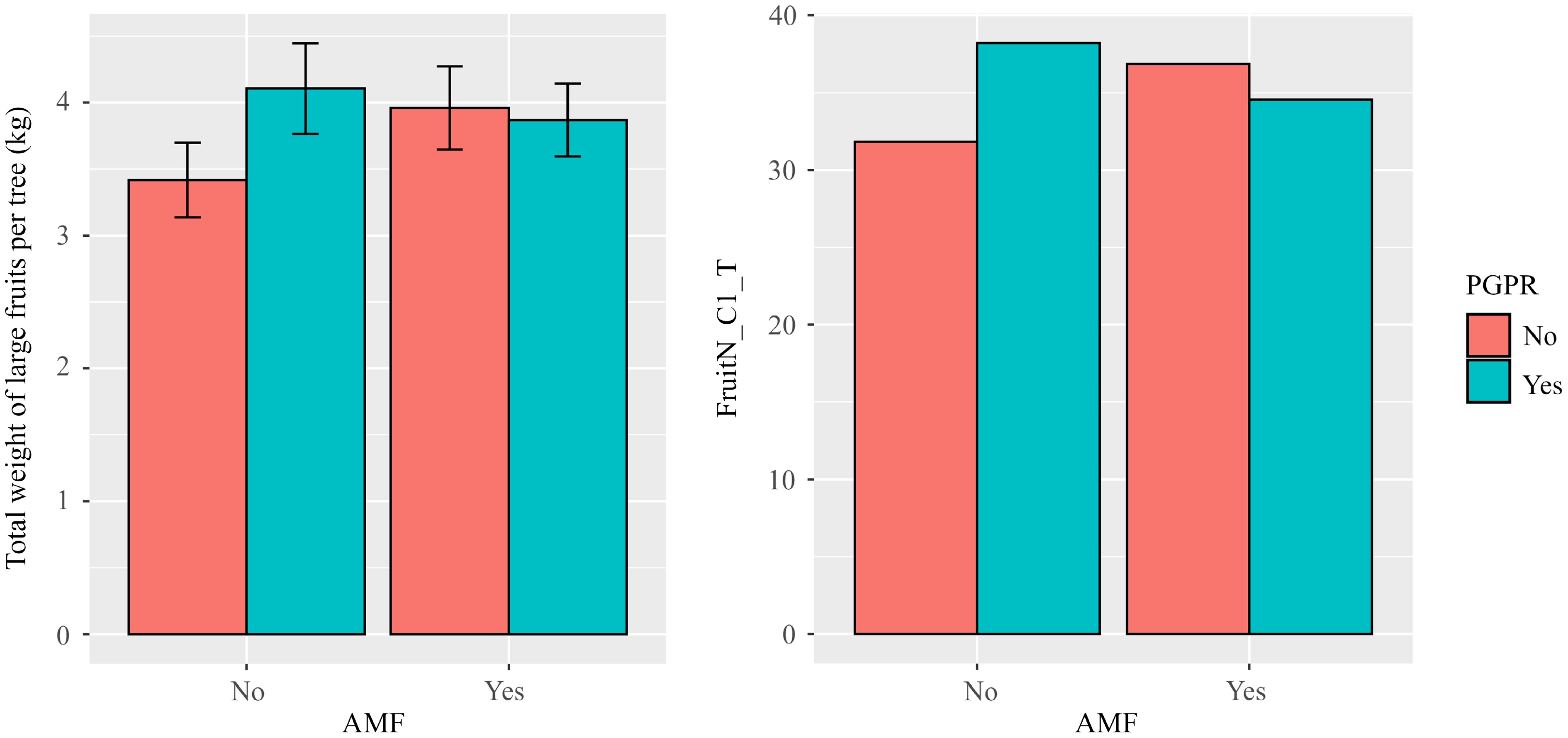

There were no significant treatment effects on the number and weight of large fruit when the longitudinal data were analysed, except for the significant negative interaction (p < 0.05) between AMF and PGPR for both the weight and number of large fruit (Table 4). This negative interaction is illustrated by Fig. 3—joint amendment with AMF and PGPR led to much reduced fruit production than expected from the individual amendment with AMF or PGPR. When the total fruit weight and number (summarised over both small and large fruit) were analysed, none of the treatment effects was statistically significant (Table 4).

Figure 3.

Average total weight (kg) and number of large fruits per tree over the four years (2021–2024) for soil amendment with each combination of single-strain AMF and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR); the bar indicates one standard error. Trees of the apple cultivar Gala, grafted onto M9 rootstocks, were planted in April 2020, and soils amended at planting in a 2 × 2 × 2 factorial amendment design (a single AMF strain [yes, no], biocontrol agents [yes, no] and PGPR [yes, no]). There were significant negative interactions between AMF and PGPR amendment (p < 0.05) for the total weight and number of large fruits per tree.

Estimated canopy cover area and tree height

-

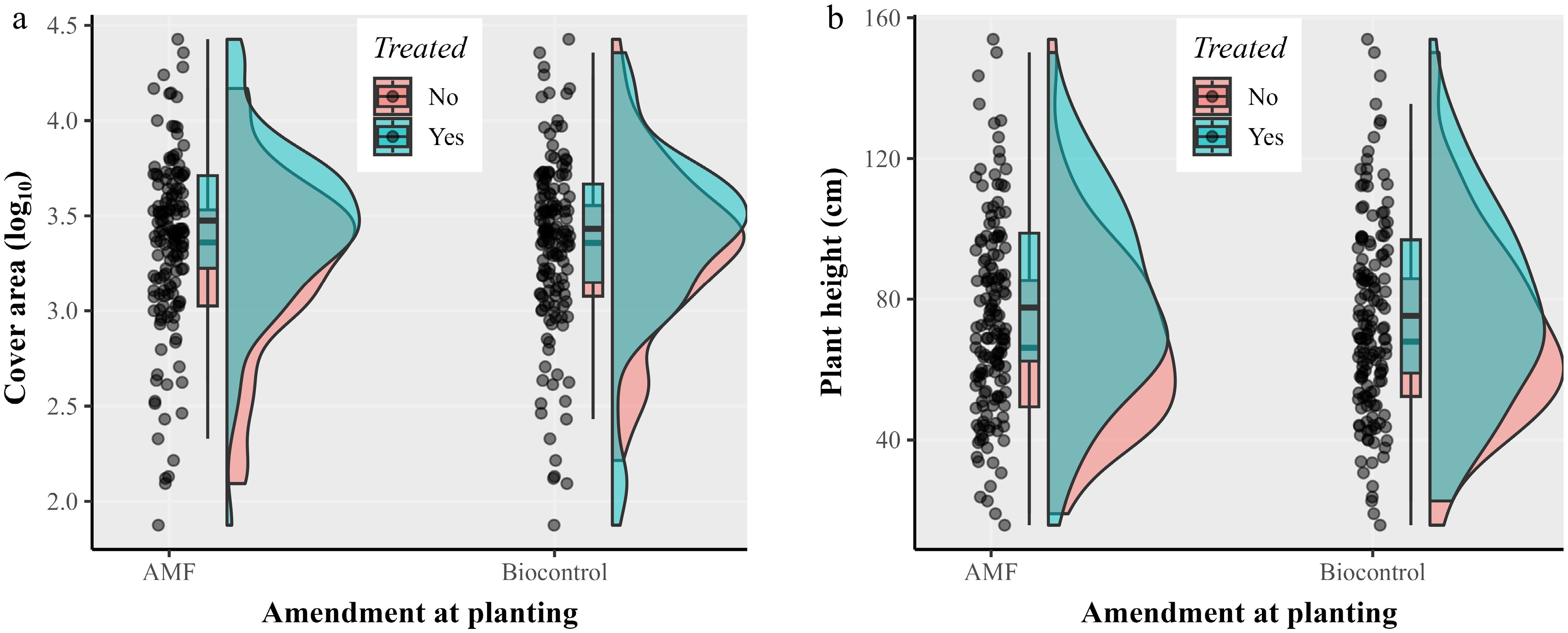

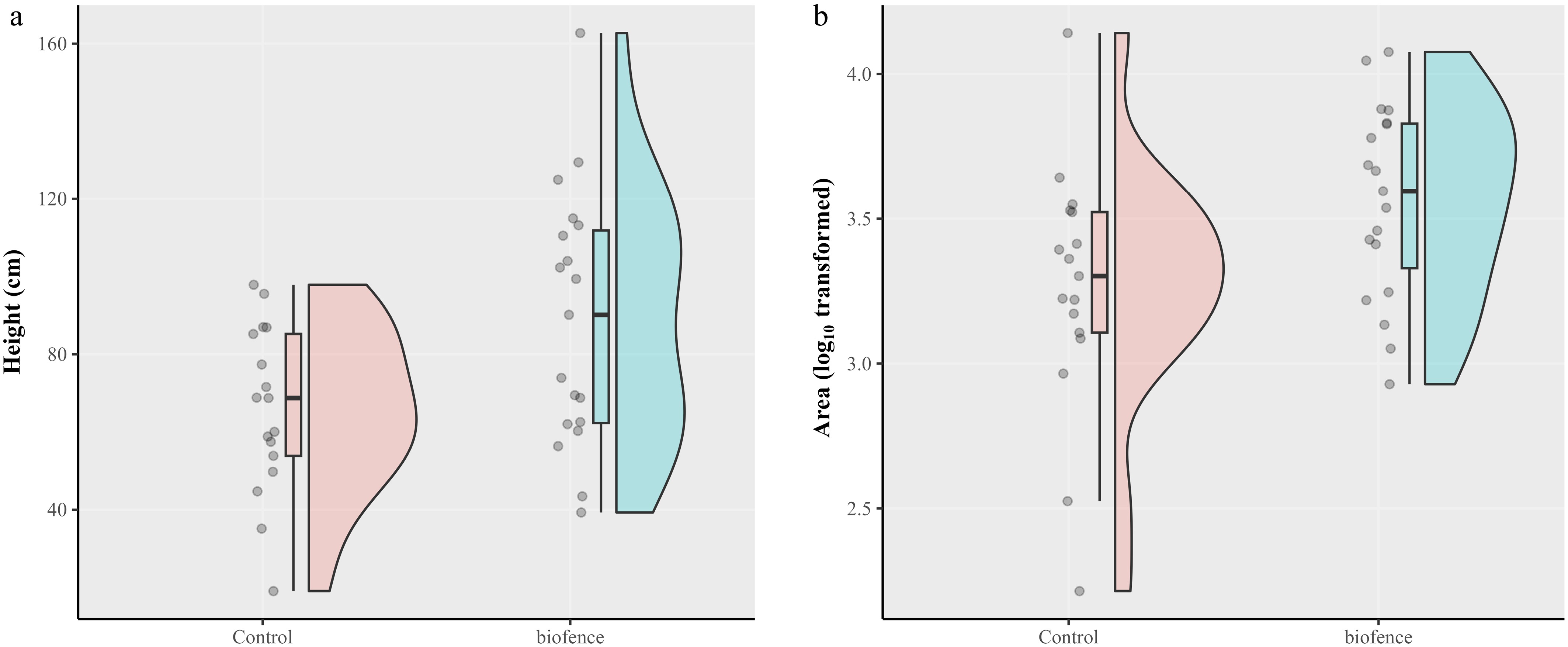

The distribution of untransformed canopy cover area was extremely skewed, and logarithmically transformed values were close to normal distributions (Fig. 4a). Only the main effect of AMF amendment at planting led to a significant (p < 0.01) increase in the estimated canopy area (Fig. 3a, Table 2): 2968 (± 353.7) vs 4293 (± 531.8). The overall positive effect of amending soils with BCAs was also close to statistical significance (p < 0.1, Table 2). For plant height, only the main effect of single AMF-strain amendment was significant (p < 0.01, Table 2), on average increasing plant height from 68.6 (± 2.92) cm (without amendment) to 80.9 (± 3.12) cm (with amendment).

Figure 4.

Scatter and density plots depicting the distribution of estimated tree height (cm) and project canopy cover area via analysis of drone-captured images in October 2023. Trees were planted in April 2020 and soils amended in a 2 × 2 × 2 factorial amendment design (a single AMF strain [yes, no], biocontrol agents [BCAs] [yes, no] and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria [yes, no]). The main effect of AMF amendment was significant (p < 0.01) for both tree height and canopy area, whereas the main effect of BCA amendment was close to statistical significance (p < 0.1) for the tree height only.

Comparisons of AMF only and Biofence amendment with the untreated

-

Supplementary Fig. S2 shows the annual girth expansion of individual trees for the four selected treatments: Biofence, single AMF, mixed AMF, and the untreated control, indicating an overall increased girth expansion associated with AMF amendment compared to Biofence and the untreated. Amendment with the single-strain (species) AMF alone (i.e., without any BCA or PGPR amendment) or the mixed AMF product did not lead to statistically significant differences for all traits assessed. Thus, these two AMF treatments were combined into a single group for comparison with the untreated. Compared to the girth expansion rate of 0.647 mm/year for the untreated control, the average annual girth expansion was 0.756 mm/year for AMF-amended trees, an increase of 18.4%. AMF did not significantly impact fruit production, plant height, and canopy area.

Amending soils with Biofence did not significantly affect girth expansion or fruit production when compared with the untreated control. However, Biofence amendment significantly increased plant height and projected canopy cover area (p < 0.01) over the untreated (Fig. 5). The plant height for the untreated control and Biofence treatment were 65.8 and 88.8 cm, respectively; the corresponding projected canopy cover areas were 2,740 and 4,701 (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 5.

Scatter and density plots depicting distribution of (a) estimated tree height (cm), and (b) projected canopy cover area via analysis of drone-captured images in October 2023 for the untreated and Biofence soil amendment. Trees of the apple cultivars Gala, grafted onto M9 rootstocks, were planted with various soil amendment treatments in April 2020; there were 20 replicate trees per treatment. Biofence amendment significantly (p < 0.01) increased both plant height and projected canopy cover.

-

The withdrawal of broad-spectrum soil fumigants necessitates the search for alternative strategies to manage ARD. The complex nature of ARD suggests that combinations of individual interventions may be required, particularly in locations where multiple ARD-causal organisms are present. This research investigated the individual and combined use of AMF, PGPR, and BCAs at the time of tree planting. A significant improvement in tree growth resulted from the application of AMF and BCA amendment at planting. Furthermore, the effects of the single-strain AMF and the two BCAs on tree growth are additive. However, amending soils with the two specific PGPR strains did not lead to any benefit in tree development.

AMF can assist plant hosts in water and nutrient uptake, and tolerating and resisting plant pathogens in exchange for photosynthetic products[22]. The present results agree with most published findings on the positive effects of AMF on apple tree growth. Inoculation of Funneliformis mosseae improved photosynthesis under high salinity and significantly increased apple root length, surface area, average diameter, and number of root forks[23]. In China, Fusarium spp. are believed to be the main ARD causal agents, and inoculation of apple seedlings with AMF led to increased apple resistance against F. solani and also improved nitrogen absorption[24]. The positive effects of AMF on apple seedling development is, however, soil-dependent[25]. Thus, the effect of AMF inoculation was greater when seedlings were grown in ARD or virgin soil fumigated with formaldehyde. AMF inoculation also led to reduced populations of fungi, bacteria, and actinomycetes in the rhizosphere of apple seedlings grown in ARD soil[25]. Inoculation of apple seedlings with Glomus fasciculatum led to improved apple seedling growth after 12 months, but not with G. macrocarpum[26]. Similarly, the positive effect of AMF on apple rootstock seedling (M29) development varied greatly with the specific AMF species/strains used[27]. Most published work on the use of AMF in apple has been on apple seedlings and/or conducted within a period of 1–2 years. In contrast, in this study, commercially relevant trees were used, and tree development was monitored over a period of four growing seasons. Furthermore, using a single Diversispora species (strain) AMF product resulted in similar effects on tree development as a product with five AMF species (strains). This study demonstrated the long-lasting effects of a single amendment with AMF at planting on apple tree establishment, resulting in a ca. 18% increase in the annual girth expansion. The initial assessment of native AMF presence in the study orchard revealed a low level of AMF inoculum (baseline samples assessed independently by INOCULUM plus [France], showing AMF in the range between 0–586 propagules/kg of soil), which may partially explain the positive AMF effects observed in the study.

This trial was not irrigated and relied on rainfall to provide sufficient water for the trees, as is standard commercial practice in the UK. The 2022 growing season was particularly dry and hot, and tree growth recorded at the end of this season showed significant differences, especially in trunk girth, between treatments. The colonisation of the treated roots by AMF likely decreased drought-induced stress from a lack of available ground water. The use of AMF has been widely shown to allow multiple hosts to tolerate drought-induced conditions[28,29].

Biocontrol against ARD has been studied in many apple-growing regions. In this study, the use of the two commercial BCAs (T. harzianum and B. subtilis [reclassified as B. amyloliquefaciens]) led to significant increases in apple tree development within the four growing seasons after orchard planting. Specific strains from several Bacillus species, including B. licheniformis[30], B. vallismortis[31], and B. amyloliquefaciens[32], have shown biocontrol potential against ARD pathogens (Fusarium spp.) in China. Individual strains from B. subtilis varied greatly in their abilities to improve tree development in ARD soil—only two out of 12 strains led to noticeable improved shoot growth in unfertilised and unpasteurised ARD soil[33]. A specific apple endophytic T. asperellum strain significantly inhibited F. proliferatum, a causal agent of ARD in China[34].

Most importantly, this study demonstrated that BCAs and AMF acted independently in terms of their growth promotion effects on apple trees—the joint use of the two strategies led to a ca. 18% increase in the annual girth expansion during the four-year period. This contrasts with the combined use of biocontrol microbes against plant pathogens, where nearly all experimental studies indicated competitive interactions among biocontrol microbes[35]. Thus, it is likely that AMF and BCAs promoted apple tree development through independent mechanisms—AMF mainly via improved nutrient and water uptake, whereas BCAs mainly via their direct effects against ARD pathogens. Analysis of annual girth expansion also indicated that the benefit of AMF was absent for the 2020–2021 growing season (immediately following replanting). Establishment of AMF-plant symbiosis may take time (colonising new roots and developing extensive extraradical hyphal networks) and could initially cost host plants more in terms of AMF utilisation of photosynthesis products; once established, plants may benefit more in net from such symbiosis[36,37]. One published study suggested a possible competitive interaction between AMF and Trichoderma spp. in promoting apple tree development in replant soils[38], though no statistical analysis was conducted to validate this statement. Obviously, the nature of the interactions between AMF and BCAs in affecting apple tree development may depend on specific strains used.

In contrast to our initial expectation, amending soils with a few selected known PGPR strains did not lead to improved tree development. One explanation could be that the resident PGPR population was already at a sufficiently high level. Currently, we are analysing amplicon-sequence data from the rhizosphere of individual trees over time, which may shed more light on this specific point. The specific two strains used in the present study had not been tested on apple previously and were used as they were commercially available PGPR products, from a UK company, recommended for use with apple. Thus, the two strains may not have the ability to promote apple tree development in this orchard. Other PGPR strains were shown to possess the ability to improve apple tolerance against ARD, such as fluorescent Pseudomonas sp.[39]. We did not choose Pseudomonas strains since they are also reported to have additional biocontrol effects[40,41]. Finally, the two applied PGPR strains may not be able to persist for sufficient time in the rhizosphere to promote tree development. For annual girth expansion and fruit production in specific years, there is an indication of negative interactions of PGPR with either AMF or BCAs. The underlying biological mechanisms for such negative interactions are unknown. Possibly, augmented application of PGPR at the same time as BCAs or AMF organisms may have resulted in increased competition among these organisms, leading to reduced establishment of BCAs in rhizosphere and AMF in the young roots. Further research is needed to confirm the presence of negative interactions of PGPR with AMF and PGPR and to study the biological mechanisms underlying the negative interactions.

A specific Brassicaceae seed meal product (Biofence) was also used as an amendment at planting, as previous research suggested its long-term suppression of ARD pathogens, including P. penetrans and Pythium spp[16,42]. Mixed cropping with Allium fistulosum or Brassica juncea led to significant suppression of ARD, promoting apple tree growth[43]. However, the present results suggest that Biofence only improved plant height and projected canopy area, which could be due to nitrogen content in the seed meal, but did not lead to improved girth expansion over time. The lack of effect of using Biofence may be due to differences in the composition of ARD inoculum and/or soil microbiome between sites.

In this study, we intentionally did not prune trees or thin blossoms/fruitlets as the objective to observe unrestricted tree growth in the first four years following soil amendment. Nevertheless, there were indications that the amendment with AMF or BCAs led to increased production of marketable fruit. However, the lack of specific commercial management, as well as weather conditions in 2023, resulted in most of the fruits being small (not marketable). We plan to carry out commercial pruning and fruit thinning from late 2024 onwards to study the impact of soil amendment on fruit production.

This study used drone-captured images to estimate plant height and projected canopy cover area, and demonstrated increased height and cover area associated with AMF, BCA, or Biofence amendment. Fruit production and quality are closely related to tree canopy 3D volume and structure[44], partially due to light interception and penetration[45]. Tree 3D volume is a function of the product between height and projected cover area; thus, we would expect even greater differences between treatments in the tree 3D canopy volume. Unfortunately, the information captured in the present images is insufficient to estimate 3D canopy volume. Recently, we developed an analytic pipeline (OrchardQuant-3D) for automating tree-level analysis of key canopy and floral traits for different types of fruit orchards[46]. This tool can be used to monitor tree development for practical management, including pest and disease management.

In the long term, breeding rootstock genotypes for improved tolerance/resistance against ARD pathogens remains the most important component of any ARD management. Recent research has demonstrated the genetic basis for such resistance breeding[7,47,48]. However, in the short term, amending soils with specific products such as AMF, BCAs, biochar, biofumigant-derived products, and compost is a realistic option in the absence of virgin land and broad-spectrum fumigants. The present study demonstrated the potential of using AMF and BCAs at planting to improve tree development in replant soils. Combining these amendments with planting locations (alleyways), and using genetically different rootstocks[7,49] may lead to even better tree development.

This research was performed under the EXCALIBUR project, funded by the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program (Grant No. 817946). We thank Jennifer Kingsnorth and Georgina Fagg for technical assistance.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: secured the funding and designed the experiments: Xu X; conducted the field work: Passey T, Robinson-Boyer L; obtained the drone-based image data: Jackson R; analysed the drone-based image data: Zhou J; analysed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript: Xu X. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Pearson correlation coefficient among tree morphological traits.

- Supplementary Table S2 Treatment mean (± standard error) of annual tree girth, height and canopy cover area (measured in October 2023), and total fruit weight and number over the period of 2021-2024 for nine soil amendment treatment and the untreated control.

- Supplementary Fig. S1 Scatter and density plots depicting the distribution of tree girth measured at 20 cm above the graft union of all individual trees; trees of the apple cultivar Gala, grafted onto the M9 rootstock, were planted in March 2020 with soils amended with one of nine soil treatments in addition to an unamended control. At planting, girth was measured at 5 cm above the graft union. In total there were 200 trees: 20 replicate trees for each treatment.

- Supplementary Fig. S2 Scatter and density plots depicting the distribution of tree girth measured at 20 cm above the graft union measured annually in spring; trees of the apple cultivar Gala, grafted onto the M9 rootstock, were planted in March 2020 and soils amended with a single-strain AMF product, or five-strain AMF mix product, or a Brassicaceae seed meal product (Biofence); the control trees did not receive any amendment. There were 20 replicate trees per treatment.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Passey T, Robinson-Boyer L, Jackson R, Zhou J, Xu X. 2026. Microbial soil amendment to improve apple tree establishment following planting. Technology in Horticulture 6: e004 doi: 10.48130/tihort-0025-0039

Microbial soil amendment to improve apple tree establishment following planting

- Received: 09 July 2025

- Revised: 31 October 2025

- Accepted: 06 November 2025

- Published online: 02 February 2026

Abstract: Symptoms due to Apple Replant Disease (ARD) complex typically appear shortly after replanting when apple trees are replanted in soils where the same, or a closely related species, has grown previously. The individual and combined use of a single-strain of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), and biocontrol agents (BCAs) at planting to support tree establishment were investigated. A Brassicaceae seed meal product (Biofence), and a formulated product of a five AMF species/strains mix were also included as two treatments. Trees were planted in spring 2020 with the soil amendment applied at planting. Tree growth was monitored annually until Spring 2024. Amendment with the single-strain AMF and BCAs resulted in an overall significant increase of 11% and 7% in the annual girth expansion rate, respectively. There were no significant interactions between the single-strain AMF and BCAs regarding the benefit conferred to tree development. Overall, only the single-strain AMF led to significant increases in both plant height and projected canopy area. PGPR failed to improve tree development and, in several cases, interacted negatively with AMF and BCA amendment. Furthermore, annual re-application of BCA and PGPR did not result in any significant additional benefit. The single-strain AMF resulted in similar benefits to plant growth as the five-species AMF mix. Biofence resulted in a significant increase in plant height and canopy cover, but not girth expansion. Present results suggest that amending soils with AMF alone, or jointly with BCAs at planting, can improve tree development and should be exploited in practice.