-

Enhancing the recycling of agricultural waste and promoting the use of organic residues from agricultural production are crucial for advancing green development and fostering harmony between humanity and nature. These efforts also represent key strategies for driving comprehensive rural revitalization. Agricultural biomass energy technologies play an essential role in improving the efficient use of agricultural waste. By converting agricultural residues into bioenergy, these technologies mitigate environmental pollution, promote the substitution of fossil fuels to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, and strengthen soil carbon sequestration, water retention, and nutrient conservation, thereby contributing to the achievement of China's dual carbon goals[1].

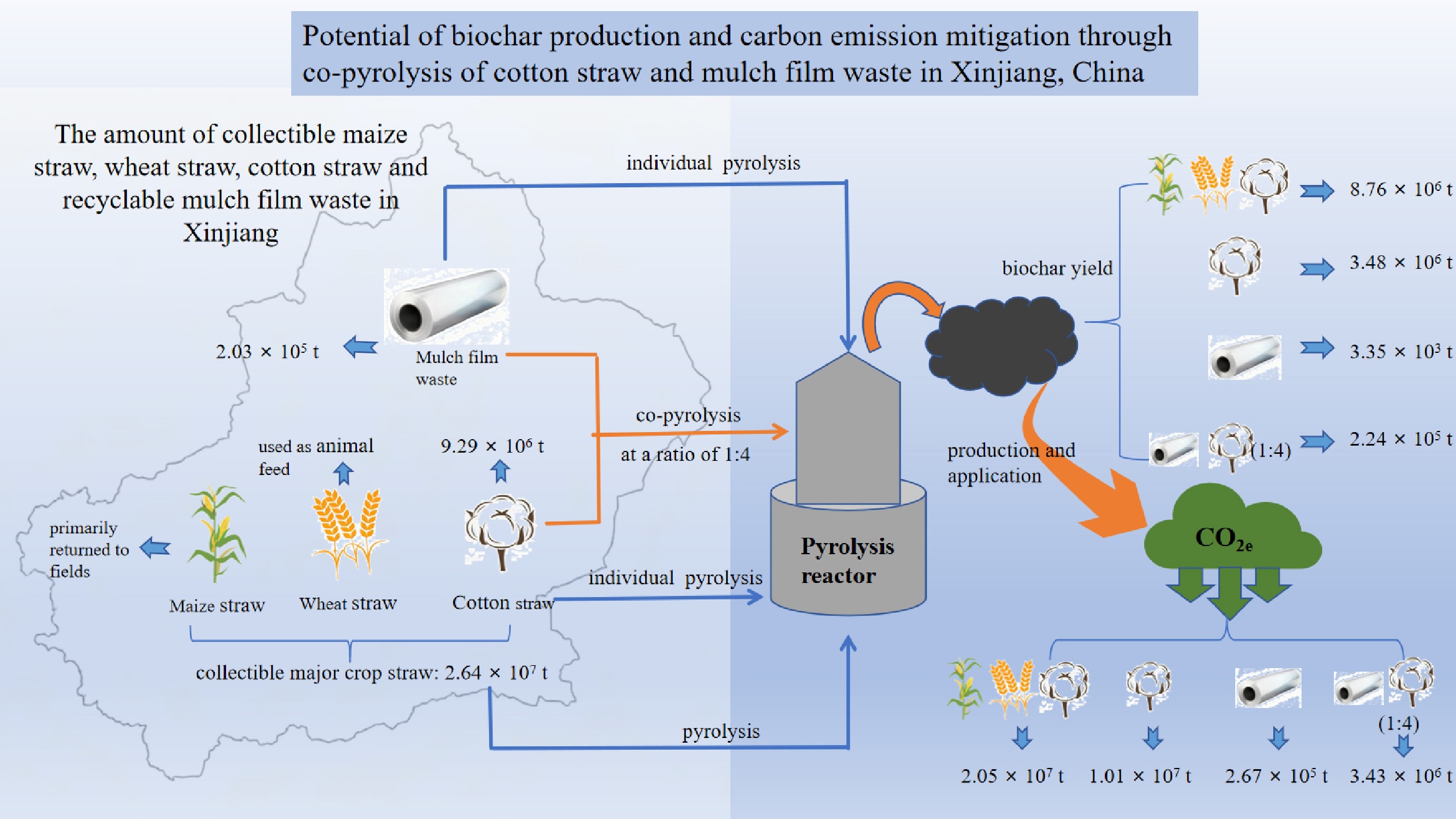

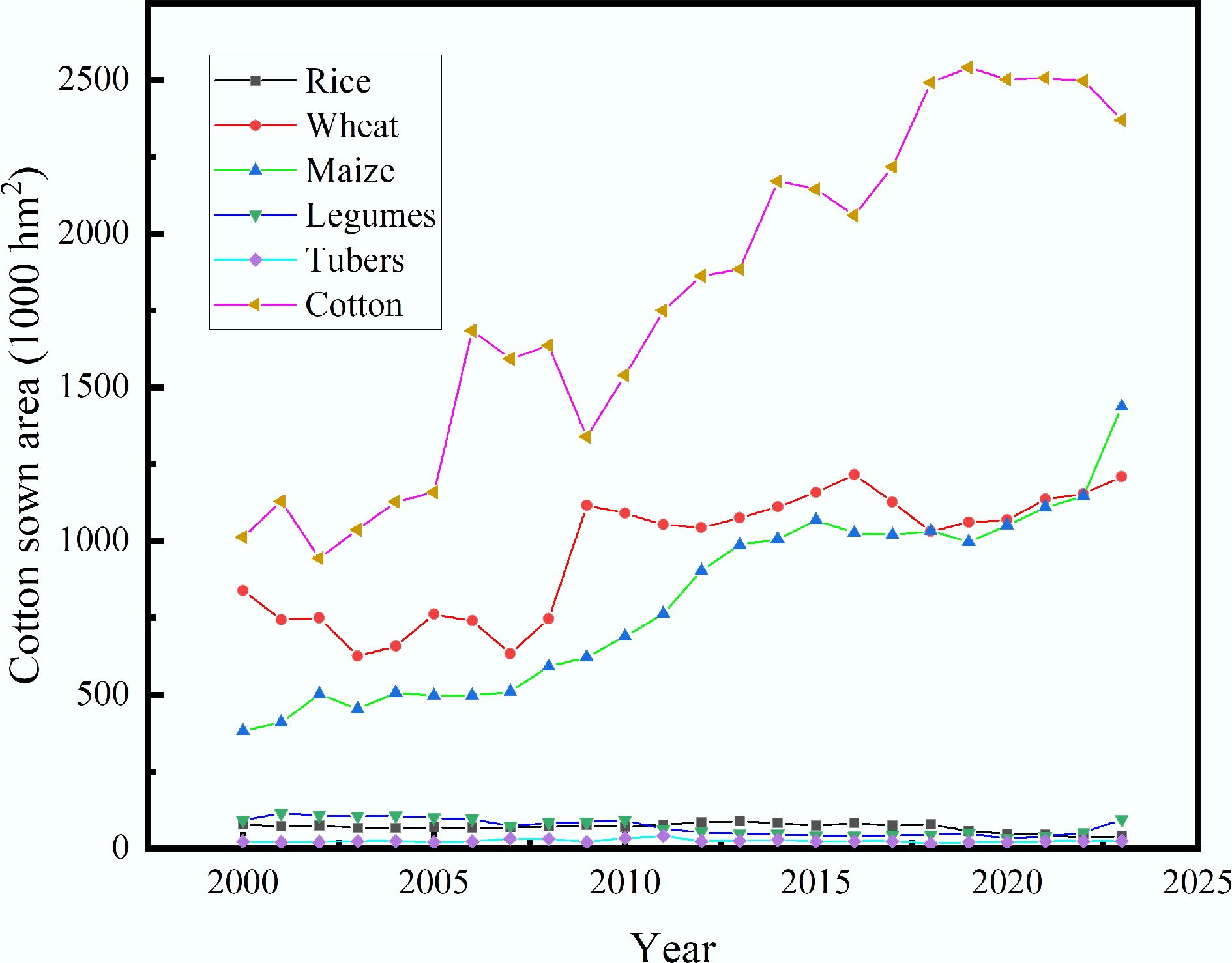

As a major agricultural production region in China, Xinjiang recorded a total sown crop area of 6.8398 × 106 hm2, and a farming output of 2.1192 × 107 t in 2023. The combined amount of maize, wheat, and cotton straw reached approximately 3.39 × 107 t, with an estimated collectible quantity of 2.64 × 107 t[2]. Currently, wheat straw in Xinjiang is mainly returned to the field, and maize straw is predominantly used as livestock feed. The remaining residues, largely cotton straw, are often discarded or directly burned, resulting in a low resource utilization rate. Returning straw to the field provides only temporary carbon storage; once decomposed by microorganisms, much of the carbon is re-emitted into the atmosphere, contributing to new carbon sources. Improper ways of returning straw to the field can also increase the risk of pest infestations and diseases while depleting soil nitrogen, thereby adversely affecting crop growth[3]. Utilizing straw as animal feed offers an alternative reuse pathway; however, due to the high cellulose and lignin contents of most straw types, digestibility is limited, reducing their nutritional value for livestock. Consequently, this approach is primarily suitable for plant residues with low lignin content, such as maize, wheat, and sorghum straw.

Mulch film is also extensively used across Xinjiang's agricultural landscape, covering over 2.5 million hm2, which accounts for more than 60% of the region's total cropland area. Its use significantly enhances crop yields and conserves soil moisture and temperature[4]. However, the widespread use of mulch film has led to growing 'white pollution' concerns. Although measures such as promoting thicker, high-strength films, testing fully biodegradable alternatives, and developing new technologies and machinery for film recovery and treatment have gained traction, residual mulch film pollution remains a persistent issue[5]. Consequently, there is an urgent need to advance research on the integrated utilization of crop straw and mulch film to address pollution control, carbon mitigation, and the broader goals of green and sustainable agricultural development in Xinjiang[6].

It is encouraging that in recent years, several scholars have begun to address this issue. Regarding the estimation of straw and mulch film resources, most existing studies calculate straw availability primarily using the straw-to-grain ratio method[7]. However, many of these studies employ a uniform coefficient for each crop variety at the national scale, without accounting for regional variations in crop yields and straw-to-grain ratios. As a result, the accuracy of such estimates remains limited. In addition, numerous studies have examined straw pyrolysis as a means of carbon reduction and sequestration[8]. Findings consistently demonstrate that, compared to direct straw incorporation into soils, pyrolyzing straw to produce biochar not only enhances crop yields but also substantially reduces greenhouse gas emissions[9,10]. For instance, Chang et al.[11] reported from a seven-year trial that applying straw biochar to farmland increased average crop yields by 2.28%–9.94%, reduced greenhouse gas emission intensity by 1.6–8.6 times, and decreased the global net warming potential (GWP) by 1.1–7.7 times. These results confirm that biochar production offers significant advantages over conventional straw return to the field. Similarly, Zhu et al.[12] applied a life cycle assessment (LCA) model to assess the carbon reduction potential of biochar used for both energy and soil applications, revealing that more than 2.07 × 105 t CO2e of carbon emissions could be reduced in Weinan City, Shaanxi Province, China. Collectively, these findings underscore that pyrolyzing straw to produce biochar is an effective approach to enhance soil carbon sequestration, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and promote the sustainable utilization of straw residues. However, integrated approaches for the synergistic treatment of crop straw and residual mulch film are still in their early stages and warrant further investigation.

Given the low biochar yield from mulch film pyrolysis alone, researchers have proposed the co-pyrolysis of residual mulch film with crop straw to enhance biochar production and achieve greater carbon reduction. For instance, Zhang et al.[13] co-pyrolyzed cotton straw and mulch film to produce biochar and bio-oil, leading to significantly improved economic returns and achieving negative carbon emissions, with a GWP of approximately 1.298 kg CO2-eq·kg−1. However, most existing research on carbon reduction via straw-derived biochar has been conducted at the national scale, while research at the regional level remains limited. Moreover, comprehensive assessments of the combined carbon reduction potential of the two major agricultural waste types, straw and mulch film, are scarce, particularly for Xinjiang. Therefore, investigating the integrated utilization of these agricultural residues in Xinjiang is particularly important.

To comprehensively assess the potential for biochar production from crop straw and mulch film in Xinjiang, this study first estimated the collectible quantities of crop straw using the straw-to-grain ratio method and the collection coefficients. Subsequently, relevant literature was reviewed to determine the usage intensity and recyclable amount of mulch film in the region. Through this literature analysis, appropriate calculation parameters for biochar yields and carbon sequestration rates of different crop straw and mulch film were established. Employing the LCA approach, the study further evaluated the carbon reduction potential of biochar production under the four scenarios in Xinjiang: (1) Pyrolysis of all major crop straw (maize, wheat, and cotton); (2) Separate pyrolysis of all cotton straw; (3) Separate pyrolysis of all recyclable mulch film; and (4) Co-pyrolysis of all recyclable mulch film and cotton straw at a mass ratio of 1:4. The aims were to provide a scientific reference for understanding the current situation regarding crop straw and mulch film resources in Xinjiang, assess the potential of biochar production and carbon emission mitigation, and promote the sustainable and rational utilization of agricultural residues in this region.

-

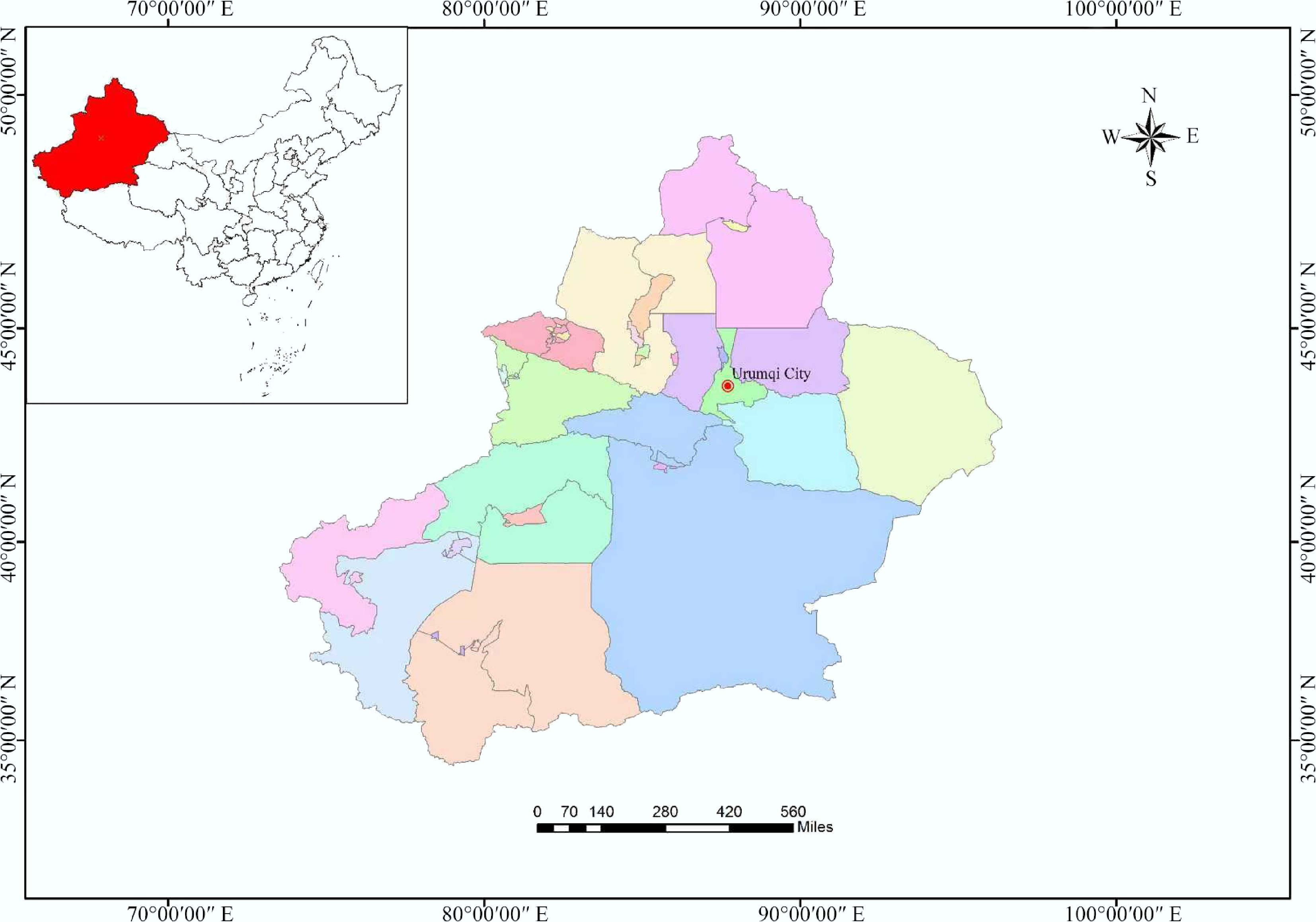

The Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region is located between 73°40' and 96°23' E longitude, and 34°25' and 49°10' N latitude (Fig. 1). As the largest provincial-level administrative region in China, it covers a total area of 1.6649 million km2, accounting for approximately one-sixth of the total land area of the country.

Data sources

-

The data used in this study were sourced from the China Statistical Yearbook 2024 (statistics cover the period up to the end of 2023) and relevant published research papers.

Methods for evaluation and estimation of indicators

-

Following the LCA methodology[14], several key indicators were selected for evaluation: (1) annual theoretical straw resource volume (Q1); (2) annual collectible straw resource volume (Q2); (3) annual mulch film resource recyclable volume (Q3); (4) annual biochar production potential (Q4). These indicators were calculated using Eqs (1)–(4).

$ {Q}_{1}=\sum \limits_{i=1}^{n}\,{p}_{i}\times {r}_{i} $ (1) $ {Q}_{2}=\sum \limits_{i=1}^{n}\,{p}_{i}\times {r}_{i}\times {\alpha }_{i} $ (2) $ {Q}_{3}=q\times \beta $ (3) $ {Q}_{4}=\sum \limits_{i=1}^{n}\,{S}_{i}\times {\eta }_{i} $ (4) where, Q1 denotes the theoretically obtainable quantity of maize, wheat, and cotton straw in Xinjiang; i represents the straw type identifier (i = 1, 2, 3); pi denotes the annual yield of the i-th crop in the region; and ri denotes the straw-to-grain ratio of the i-th crop, defined as the ratio of the wind-dried straw weight to grain yield per unit area. For Xinjiang's main crops, the values of ri are 1.033 for maize, 1.093 for wheat, and 2.455 for cotton[15]. Q2 denotes the collectible amount of straw from the three major crops in Xinjiang; αi denotes the collectible coefficient of the i-th straw, defined as the ratio of the collectible straw quantity to the theoretical straw quantity of that crop. This coefficient is influenced by factors such as plant height, cutting height (mechanical or manual), mechanization rate, and collection and transportation losses. The αi value for major crops in Xinjiang is 0.813 for maize, 0.785 for wheat, and 0.74 for cotton[15]. Q3 denotes the annual recyclable volume of mulch film in Xinjiang; q represents the annual mulch film usage volume; and β denotes the recovery rate of mulch film. Q4 denotes the total biochar yield from crop straw and mulch film. Si denotes the collectible quantity of the i-th type of straw or mulch film, and ŋi refers to the biochar yield for the corresponding material.

The quantity of carbon sequestered via soil application of biochar (Q5) was estimated using Eq. (5):

$ {Q}_{5}=\sum \limits_{i=1}^{n}\,{c}_{i}\times {t}_{i} $ (5) where, Q5 denotes the total amount of soil-sequestered carbon; ci represents the biochar yield derived from the i-th feedstock; and ti indicates the carbon content of the biochar produced from the i-th feedstock.

-

According to the China Statistical Yearbook, the output of major agricultural products in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region has shown a steady upward trend over the past decade (2014–2023). In 2023, the production of maize, wheat, and cotton reached approximately 1.3214 × 107, 7.028 × 106, and 5.112 × 106 t[2]. Based on the straw-to-grain ratios and collectible coefficients for these main crops, the total straw production from maize, wheat, and cotton in 2023 was estimated at 1.36 × 107, 7.68 × 106, and 1.25 × 107 t, respectively. The corresponding collectible straw quantities were calculated to be 1.11 × 107, 6.03 × 106, and 9.29 × 106 t, respectively, for Xinjiang.

Xinjiang ranks first nationwide in both mulch film usage and coverage area. According to the China Rural Statistical Yearbook, the region's annual mulch film usage reached 2.5 × 105 t, and the mulch film coverage exceeded 4 × 106 hm2, which accounts for more than a quarter of the total national mulch film usage. The mulching rate for major crops such as cotton and maize exceeded 90%[16]. Data from the China Agriculture Network indicate that Xinjiang has made significant progress in the recovery of waste mulch film. By 2021, the recovery rate had reached 81%, with an estimated recyclable quantity of 2.03 × 105 t.

Potential of biochar production and carbon emission reduction through pyrolysis of crop straw and mulch film

-

Crop straw, a major component of agricultural waste, is characterized by high volume, diverse composition, and rich carbon content[17]. Meanwhile, recycled agricultural mulch film often contains excessive impurities, which hinder efficient resource recovery. The mixture of straw and mulch film poses particular challenges, as separation is exceptionally difficult; consequently, such mixed residues have become a major non-point source of agricultural pollution[5]. Pyrolysis technology provides an effective pathway for converting agricultural waste, such as straw and mulch film, into high-value, eco-friendly products, including biochar, combustible gases, and bio-oil[18]. This process offers advantages such as simplified treatment procedures and controllable conversion costs[19]. In the energy sector, biochar can be further processed into biochar-based briquettes[20]. Moreover, owing to its high carbon content, large specific surface area, stable chemical properties, and the presence of elements such as hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, phosphorus, and minerals, biochar serves as an excellent soil conditioner. Its long-term stability allows it to persist in soil for centuries to millennia, improving soil structure and fertility while providing substantial carbon sequestration benefits[18]. In this study, the LCA approach was employed to evaluate the potential for biochar production and carbon emission reduction from the pyrolysis of crop straw and residual mulch film in Xinjiang. The objective of the LCA was to quantitatively assess the net CO2e balance associated with the production and application of biochar derived from these resources. The assessment scope primarily encompassed: (1) the CO2e balance across key stages, including raw material collection, biochar production, and transportation of both feedstocks and biochar; and (2) the beneficial impacts from renewable energy by-products and biochar application on the overall CO2e balance[21].

Potential of biochar production and carbon reduction from the pyrolysis of wheat, maize, and cotton straw in Xinjiang

-

The key parameters for biochar production using the total collectible quantities of wheat, maize, and cotton straw in Xinjiang for 2023 are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Relevant parameters and estimated potential for greenhouse gas mitigation through biochar production from major collectible crop straw resources in Xinjiang, 2023

Parameter Value1 Parameter

code2Calculation process Ref. The heat energy generated during biochar production can replace the combustion of

fossil fuelsTotal amount of straw feedstock (t) 2.64 × 107 A1 Eq. (2) This study Biogas yield (%) 35% A2 [22] Calorific value of biogas (MJ·kg−1) 6 A3 [23] Electricity conversion coefficient (%) 35% A4 [24] CO2 emissions from power generation (kg·kWh−1) 0.8426 A5 [25] Electricity output during biochar production (kWh) 5.39 × 109 A6 A1 × A2 × A3 × A4/3.6 × 1,000 —3 CO2 emissions reduction from coal substitution (t) 4.54 × 106 A7 A6 × A5/1,000 — Calculation of biochar yield and carbon sequestration rate Biochar yield (%) 30.34% (m), 31.71% (w), 37.5% (c) A8 [26,27] Biochar carbon content (%) 59.76% (m), 62.89% (w), 73.4% (c) A9 [26, 28] The ratio of biochar's stable component (%) 80% A10 [21] C-CO2 conversion coefficient 3.67 A11 — Total biochar produced (t) 8.76 × 106 A12 Eq. (4) This study Amount of carbon sequestered via soil application of biochar (t) 4.62 × 106 A13 Eq. (5) This study Amount of CO2 sequestered via soil application of biochar (t) 1.70 × 107 A14 A13 × A11 — The inhibition of N2O emissions by biochar The rate of N2O emission suppression by biochar (%) 87% A15 [29] N2O emissions (kg·hm−2) 1.86 (m), 1.54 (w), 2.10 (c) A16 [12, 30] Proportion of biochar applied to soil (t·hm−2) 50 A17 [31] Area available for biochar application (hm2) 6.74 × 104 (m), 3.82 × 103 (w),

6.97 × 104 (c)A18 A12 /A17 — N2O-CO2 conversion coefficient 298 A19 [21] The reduction in N2O emissions (t) 241.53 A20 ∑A15 × A16 × A18/1,000 — The reduction in CO2 emissions (t) 7.2 × 104 A21 A20 × A19 — Fertilizer reduction from biochar application (calculated in CO2e) Fertilizer input rate (kg·hm−2) 167.41 (N); 98.66 (P); 35.44 (K) A22 [32] Reduction amount of agricultural fertilizer input (%) 10% (N); 5% (P); 10% (K) A23 [31] CO2e emission amount from fertilizer production (kg) 3; 0.7; 1 A24 [21] CO2e emission avoidance from reduced fertilizer application (t) 8.06 × 103 A25 ∑A18 × A22 × A23 × A24 — Greenhouse gas emissions from the storage and transportation of biochar and feedstock Greenhouse gas emission factor from the storage and transportation of straw (kg·t−1) 27.53 A26 [33] Emissions of CO2e per ton for biochar (kg) 45.32 A27 [34] CO2e emissions from straw feedstock (t) 7.27 × 105 A28 A1 × A26 — Emissions of CO2e attributable to biochar (t) 3.97 × 105 A29 A12 × A27 — Total emissions (CO2e) (t) 1.12 × 106 A30 A28 + A29 Net reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (CO2e) (t) 2.05 × 107 A32 A7 + A14 + A21 + A25–A30 — 1 m, w, and c represent maize, wheat, and cotton, respectively. 2 Parameter codes are assigned to illustrate calculation procedures. 3 — indicates that the relevant data is derived via calculation. In terms of the carbon reduction potential derived from thermal energy generated during the biochar production process, particularly through the substitution of fossil fuel combustion, both bio-oil and biogas produced during pyrolysis possess notable calorific values. However, due to current technological constraints, bio-oil cannot be directly utilized for electricity generation[35]. In 2023, the total quantity of collectible straw from major crops in Xinjiang was 2.64 × 107 t. The biogas generated during biochar production can be utilized for electricity generation (as shown in Table 1), yielding approximately 5.39 × 109 kWh, which could replace coal combustion and thereby reduce CO2 emissions by 4.54 × 106 t.

Regarding biochar production and its carbon sequestration capacity, a review of relevant studies[22] reveals that carbon content varies slightly across different types of crop straw, leading to differing biochar yields and biochar carbon content. Reported biochar yields are 30.34%, 31.71%, and 37.5% for maize, wheat, and cotton straw, respectively[26,27], suggesting a total biochar production potential from Xinjiang's major crop straw in 2023 of approximately 8.76 × 106 t. Research indicates that the carbon contents of biochar from maize, wheat, and cotton straw are 59.76%[26], 62.89%[26], and 73.40%[28], respectively. According to Roberts et al., about 20% of biochar carbon exists in unstable forms[21]. Thus, the estimated amount of carbon fixed in soil through biochar application is 4.62 × 106 t, equivalent to 1.70 × 107 t of CO2.

In terms of the inhibition of N2O release by biochar, N2O is an important greenhouse gas, with a global warming potential (GWP) as high as 298 times that of carbon dioxide[21]. N2O emissions originate from multiple pathways, and agricultural soil is one of their primary sources. Biochar application to farmland has been proven to be an effective technical measure for significantly suppressing N2O emissions from agricultural soil. Since only a portion of the arable land area is suitable for biochar application, this study focused on maize, wheat, and cotton. Biochar was assumed to be applied at an average rate of 50 t·hm−2[31]. The total arable area suitable for application is 1.73 × 105 hm2. Selecting different emission standards for N2O, and combined with the ratio of biochar inhibiting N2O emissions, the reduction in N2O emissions is 241.53 t, equivalent to 7.2 × 104 t CO2.

With regard to CO2e reduction through reduced chemical fertilizer use, biochar's rich trace element content enhances soil microbial diversity, fertility, and nutrient use efficiency[36]. When applied at appropriate rates, biochar reduces the need for conventional fertilizers while increasing nitrogen recovery[37]. Generally, vegetable and fruit crops require significantly higher fertilizer inputs than grain crops. In this study, the fertilizer application rates for grain crops were set at 167.41 kg·hm−2 (N), 98.66 kg·hm−2 (P), and 35.44 kg·hm−2 (K)[32]. Compared with conventional fertilization, biochar application reduces nitrogen and potassium supplementation by 10 % and phosphorus supplementation by 5%[31]. The resulting reduction in fertilizer use was estimated to avoid 8.06 × 103 t CO2e emissions.

To estimate greenhouse gas emissions during the storage and transportation of raw materials and biochar, the CO2 emission factor for the storage and transportation of straw is 27.53 kg·t−1[36]. Based on this, emissions from the straw feedstock were estimated at 7.27 × 105 t. Additionally, biochar releases greenhouse gases during storage and transportation. Based on the estimates by West & Gregg[34], the CO2e emission per ton of biochar is 45.32 kg. Consequently, the CO2e emissions from the storage and transportation of biochar are 3.97 × 105 t. Thus, the combined emissions from straw feedstock and biochar storage and transportation total 1.12 × 106 t CO2e.

Integrating these factors, the net CO2e reduction from producing biochar from maize, wheat, and cotton straw in Xinjiang was estimated at 2.05 × 107 t.

Potential of biochar production and carbon reduction from pyrolysis of cotton straw in Xinjiang

-

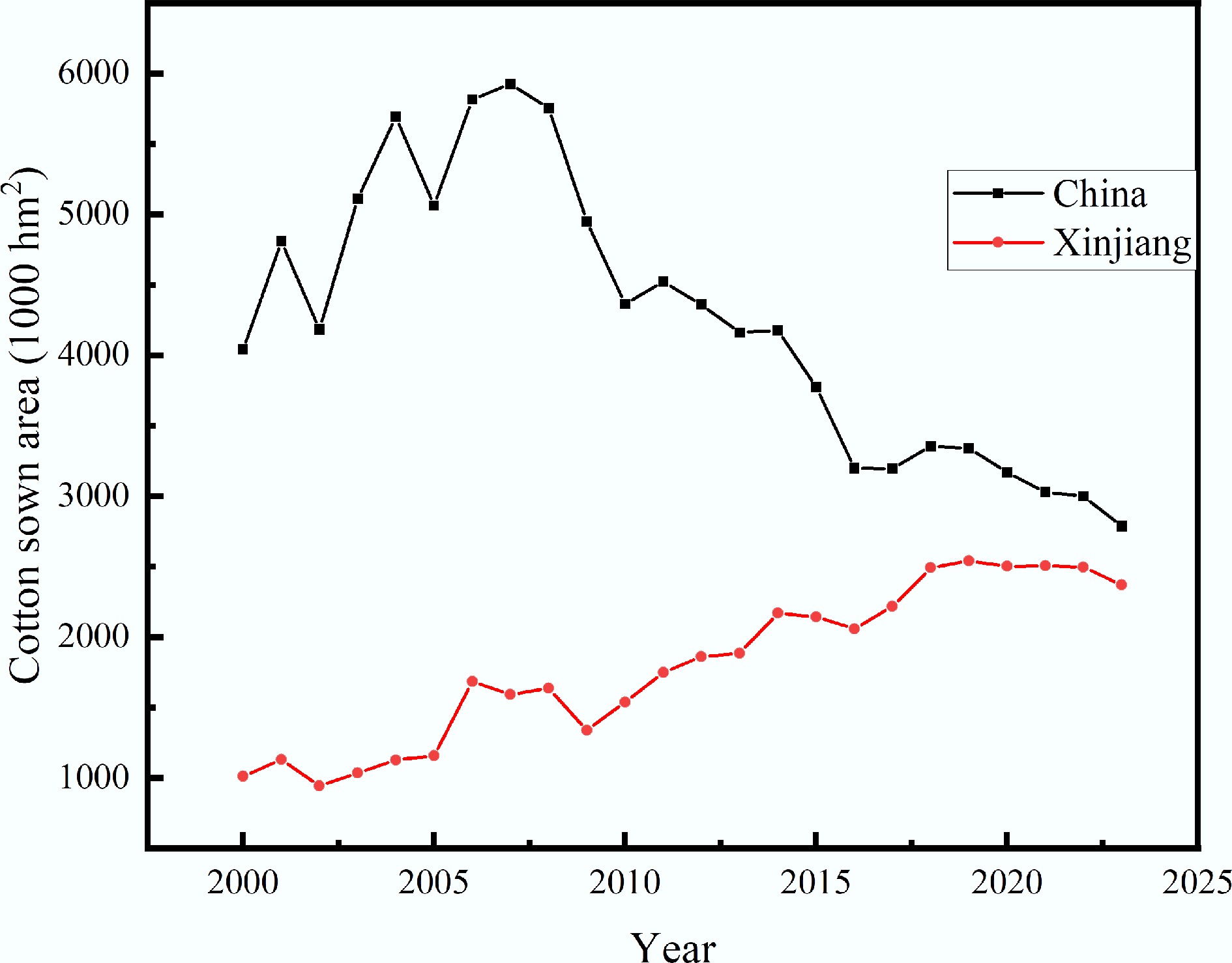

The Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region is China's primary cotton-producing area and also a globally significant base for high-quality cotton, with its cotton planting area accounting for 85% of the total cotton planting area in China (Fig. 2), and 34.6% of the total cultivated area in Xinjiang, 2023 (Fig. 3).

Currently, wheat straw is predominantly returned to the soil, while maize straw is mainly used as livestock feed. Therefore, this study separately evaluates the potential of biochar production and carbon emission reduction from cotton straw in Xinjiang, aiming to provide a scientific reference for the sustainable management of cotton waste (Table 2).

Table 2. Relevant parameters and estimated potential for greenhouse gas mitigation through biochar production from all collectible cotton straw resources in Xinjiang in 2023

Parameter Value Parameter

code1Calculation Ref. The heat energy generated during biochar production can replace the combustion of fossil fuels Total amount of cotton stalk (t) 9.29 × 106 B1 Eq. (2) This study Biogas yield (%) 35.82% B2 [38] Calorific value of biogas (MJ·kg−1) 10.9 B3 [39] Electricity conversion coefficient (%) 35% B4 [24] CO2 emissions from power generation (kg·kWh−1) 0.8426 B5 [25] Electricity output during biochar production (kWh) 3.53 × 109 B6 B1 × B2 × B3 × B4 / 3.6 × 1,000 —2 CO2 emissions reduction from coal substitution (t) 2.97 × 106 B7 B6 × B5/1,000 — Calculation of biochar yield and carbon sequestration rate Biochar yield (%) 37.5% B8 [27] Biochar carbon content (%) 73.4% B9 [28] The ratio of biochar's stable component (%) 80% B10 [21] C-CO2 conversion coefficient 3.67 B11 — Total biochar produced (t) 3.48 × 106 B12 Eq. (4) This study Amount of carbon sequestered via soil application of biochar (t) 2.04 × 106 B13 Eq. (5) This study Amount of CO2 sequestered via soil application of biochar (t) 7.5 × 106 B14 B13 × B11 — The inhibition of N2O emissions by biochar The rate of N2O emission suppression by biochar (%) 87% B15 [29] N2O emissions (kg·hm−2) 2.10 B16 [30] Proportion of biochar applied to soil (t·hm−2) 50 B17 [31] Area available for biochar application (hm2) 6.97 × 104 B18 B12 /B17 — N2O-CO2 conversion coefficient 298 B19 [21] The reduction in N2O emissions (t) 127.34 B20 ∑B15 × B16 × B18/1,000 — The reduction in CO2 emissions (t) 3.79 × 104 B21 B20 × B19 — Fertilizer reduction from biochar application (calculated in CO2e) Fertilizer input rate (kg·hm−2) 167.41 (N); 98.66 (P); 35.44 (K) B22 [32] Reduction in fertilizer input (%) 10% (N); 5% (P); 10% (K) B23 [31] CO2e emissions amount from fertilizer production (kg) 3; 0.7; 1 B24 [21] CO2e emission avoided through reduced fertilizer application (t) 3.99 × 103 B25 B18 × B22 × B23 × B24/1,000 — Greenhouse gas emissions from the storage and transportation of biochar and feedstock Greenhouse gas emission factor from the storage and transportation of straw (kg·t−1) 27.53 B26 [33] Emissions of CO2e per ton for biochar (kg) 45.32 B27 [34] CO2e emissions from cotton stalk (t) 2.56 × 105 B28 B1 × B26 — Emissions of CO2e attributable to biochar (t) 1.58 × 105 B29 B12 × B27 — Total emissions (CO2e) (t) 4.14 × 105 B30 B28 + B29 Net reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (CO2e) (t) 1.01 × 107 B31 B7 + B14 + B21 + B25–B30 — 1 Parameter codes are assigned to illustrate the calculation procedures. 2 — indicates that the relevant data is derived via calculation. The quantity of collectible cotton straw in Xinjiang in 2023 was 9.29 × 106 t. The biogas produced during the pyrolysis process can generate 3.53 × 109 kWh of electricity, resulting in a CO2 emission reduction of 2.97 × 106 t. The estimated amount of biochar yield from cotton straw in 2023 is 3.48 × 106 t, with the amount of carbon fixed in soil through biochar application approximated at 2.04 × 106 t, equivalent to 7.5 × 106 t of CO2. The estimated area for biochar application is 6.97 × 104 hm2. The reduction in N2O emissions is 127.3 t (equivalent to 3.79 × 104 t CO2). Additionally, the reduction in chemical fertilizer use due to biochar application is projected to further decrease CO2e emissions by 3.99 × 103 t. Estimated greenhouse gas emissions from the cotton straw feedstock amount to 2.56 × 105 t, while those generated during biochar storage and transportation total 1.58 × 105 t, yielding combined emissions of 4.14 × 105 t.

Overall, based on these estimates, the net CO2e reduction resulting from the production of biochar from cotton straw is 1.01 × 107 t.

Potential of biochar production and carbon reduction from pyrolysis of mulch film in Xinjiang

-

The quantity of recyclable mulch film in Xinjiang in 2023 was approximately 2.03 × 105 t. The key parameters and corresponding calculation procedures are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Relevant parameters and estimated potential for greenhouse gas mitigation through biochar production from all recyclable mulch film in Xinjiang, 2023

Parameter Value Parameter

code1Calculation Ref. The heat energy generated during biochar production can replace the combustion of fossil fuels Total amount of mulch film feedstock (t) 2.03 × 105 C1 Eq. (3) This study Biogas yield (%) 42% C2 [22] Calorific value of biogas (MJ·kg−1) 38.6 C3 [23] Electricity conversion coefficient (%) 35% C4 [24] CO2 emissions from power generation (kg·kWh−1) 0.8426 C5 [25] Electricity output during biochar production (kWh) 3.2 × 108 C6 C1 × C2 × C3 × C4/

3.6 × 1,000—2 CO2 emission reduction from coal substitution (t) 2.7 × 105 C7 C6 × C5/1,000 — Calculation of biochar yield and carbon sequestration rate Biochar yield (%) 1.65% C8 [22] Biochar carbon content (%) 8.91% C9 [22] The ratio of biochar's stable component (%) 80% C10 [21] C-CO2 conversion coefficient 3.67 C11 — Total biochar produced (t) 3.35 × 103 C12 Eq. (4) This study Amount of carbon sequestered via soil application of biochar (t) 2.39 × 102 C13 Eq. (5) This study Amount of CO2 sequestered via soil application of biochar (t) 8.76 × 102 C14 C13 × C11 — The inhibition of N2O emissions by biochar The rate of N2O emission suppression by biochar (%) 87% C15 [29] N2O emissions (kg·hm−2) 2.10 C16 [30] Proportion of biochar applied to soil (t·hm−2) 50 C17 [31] Area available for biochar application (hm2) 67 C18 C12 / C17 — N2O-CO2 conversion coefficient 298 C19 [21] The reduction in N2O emissions (t) 0.122 C20 C15 × C16 × C18/1,000 — The reduction in CO2 emissions (t) 36.48 C21 C20 × C19 — Fertilizer reduction from biochar application (calculated in CO2e) Fertilizer input rate (kg·hm−2) 167.41 (N); 98.66 (P); 35.44 (K); C22 [32] Reduction in fertilizer input (%) 10% (N); 5% (P); 10% (K) C23 [31] CO2e emissions from fertilizer production (kg) 3; 0.7; 1 C24 [21] CO2e emissions avoided through reduced fertilizer application (t) 3.83 C25 ∑C18 × C22 × C23 × C24/1,000 — Greenhouse gas emissions from the storage and transportation of biochar and feedstock Greenhouse gas emission factor from the storage and transportation of mulch film (kg·t−1) 21 C26 [33] Emissions of CO2e per ton for biochar (kg) 45.32 C27 [34] CO2e emissions from mulch film feedstock (t) 4.26 × 103 C28 C1 × C26 — Emissions of CO2e attributable to biochar (t) 1.52 × 102 C29 C12 × C27 — Total emissions (CO2e) (t) 4.41 × 103 C30 C28 + C29 Net reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (CO2e) (t) 2.67 × 105 C31 C7 + C14 + C21 + C25–C30 — 1 Parameter codes are assigned to illustrate calculation procedures. 2 — indicates that the relevant data is derived via calculation. The biogas produced during the pyrolysis process can generate 3.2 × 108 kWh of electricity, resulting in a CO2 emission reduction of 2.74 × 105 t. According to Xie et al.[22], the biochar yield from plastic film pyrolysis is only 1.65%, with a carbon content of 8.91%. Based on these parameters, the biochar production potential of mulch film in Xinjiang was estimated at 3.35 × 103 t, and the amount of carbon fixation due to soil application of biochar is 2.39 × 102 t, equivalent to 8.76 × 102 t of CO2. The area available for biochar application is 67 hm2. Furthermore, the application of biochar reduces the use of chemical fertilizers, leading to an additional CO2e emission reduction of 3.83 t. To estimate greenhouse gas emissions from storing and transporting raw materials and biochar, the CO2 emission factor from the storage and transportation of mulch film is 21 kg·t−1[33]. Based on this value, the greenhouse gas emissions from mulch film feedstock were estimated at 4.26 × 103 t, while biochar storage and transportation of biochar generate approximately 1.52 × 102 t, giving the total emissions of 4.41 × 103 t. Overall, the net CO2e reduction from producing biochar from mulch film in Xinjiang is 2.67 × 105 t.

Potential of biochar production and carbon reduction from co-pyrolysis of recyclable mulch film and cotton straw in Xinjiang

-

Previous studies have shown that the co-pyrolysis of mulch film and straw can increase the yield and quality of pyrolysis products[40]. Additionally, during the co-pyrolysis of cotton straw and mulch film, the yield of biochar derived from pyrolysis increases with the elevated proportion of cotton straw in the mixture[38]. Additionally, mulch film exhibits a lower density compared to cotton straw. Therefore, the present study employs a 1:4 mass ratio of mulch film to cotton straw for co-pyrolysis, aiming to achieve complete pyrolysis of all recyclable mulch film while maximizing biochar production. This study estimated the potential for biochar production and carbon reduction from the co-pyrolysis of all recyclable mulch film and cotton straw in Xinjiang at a ratio of 1:4 (Table 4).

Table 4. Relevant parameters and estimated potential for greenhouse gas mitigation through biochar production from all recyclable mulch film and cotton straw at a ratio of 1:4 in Xinjiang, 2023

Parameter Value Parameter code1 Calculation Ref. The heat energy generated during biochar production can replace the combustion of fossil fuels Total amount of cotton straw and mulch film feedstock (t) 1.02 × 106 D1 Eqs (2) and (3) This study Biogas yield (%) 32% D2 [38] Calorific value of biogas (MJ·kg−1) 21 D3 [38] Electricity conversion coefficient (%) 35% D4 [24] CO2 emissions from power generation (kg·kWh−1) 0.8426 D5 [25] Electricity output during biochar production (kWh) 6.66 × 108 D6 D1 × D2 × D3 × D4/3.6 × 1,000 —2 CO2 emissions reduction from coal substitution (t) 5.62 × 105 D7 D6 × D5/1,000 — Calculation of biochar yield and carbon sequestration rate Biochar yield (%) 22% D8 [38] Biochar carbon content (%) 69.91% D9 [22] The ratio of biochar's stable component (%) 80% D10 [21] C-CO2 conversion coefficient 3.67 D11 — Total biochar produced (t) 2.24 × 105 D12 Eq. (4) This study Amount of carbon sequestered via soil application of biochar (t) 1.25 × 105 D13 Eq. (5) This study Amount of CO2 sequestered via soil application of biochar (t) 4.6 × 105 D14 D13 × D11 — The inhibition of N2O emissions by biochar The rate of N2O emission suppression by biochar (%) 87% D15 [29] N2O emissions (kg·hm−2) 2.10 D16 [30] Proportion of biochar applied to soil (t·hm−2) 50 D17 [31] Area available for biochar application (hm2) 4.48 × 103 D18 D12 / D17 — N2O-CO2 conversion coefficient 298 D19 [21] The reduction in N2O emissions (t) 8.18 × 103 D20 ∑D15 × D16 × D18/1,000 — The reduction in CO2 emissions (t) 2.44 × 106 D21 D20 × D19 — Fertilizer reduction from biochar application

(calculated in CO2e)Fertilizer input rate (kg·hm−2) 167.41 (N); 98.66 (P); 35.44 (K) D22 [32] Reduction in fertilizer input (%) 10% (N); 5% (P): 10% (K) D23 [31] CO2e emissions from fertilizer production (kg) 3; 0.7; 1 D24 [21] CO2e emissions avoided through reduced fertilizer application (t) 256.35 D25 ∑D18 × D22 × D23 × D24 — Greenhouse gas emissions from the storage and transportation of biochar and feedstock Greenhouse gas emission factors from the storage and transportation of straw and mulch film (kg·t−1) 27.53, 21 D26 [33] Emissions of CO2e per ton for biochar (kg) 45.32 D27 [34] CO2e emissions from cotton straw and mulch film feedstock (t) 2.66 × 104 D28 D1 × D26 — Emissions of CO2e attributable to biochar (t) 1.02 × 104 D29 D12 × D27 — Total emissions (CO2e) (t) 3.68 × 104 D30 D28 + D29 Net reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (CO2e) (t) 3.43 × 106 D31 D7 + D14 + D21 + D25–D30 — 1 Parameter codes are assigned to illustrate calculation procedures. 2 — indicates that the relevant data is derived via calculation. In Xinjiang, the biogas produced from the co-pyrolysis of all recyclable mulch film and cotton stalk at a 1:4 mass ratio can produce 6.66 × 108 kWh of electricity, leading to a CO2 emission reduction of 5.62 × 105 t. According to Jiang et al.[38], the biochar yield from this process is 22%, giving an estimated biochar production potential of 2.24 × 105 t. The quantity of carbon sequestered through soil application of biochar is 1.25 × 105 t, equivalent to 4.6 × 105 t of CO2. The estimated area for biochar application is 4.48 × 103 hm2, which could enable a reduction in N2O emissions of 8.18 × 103 t, equivalent to 2.44 × 106 t of CO2. In addition, the use of biochar can reduce the demand for chemical fertilizers, leading to a further CO2e reduction of 256.35 t. The greenhouse gas emissions from mulch film and cotton straw feedstock amount to 2.66 × 104 t, while those generated during biochar storage and transportation were estimated at 1.02 × 104 t. Together, these contribute to the total emissions of 3.68 × 104 t CO2e. Overall, the net CO2e reduction achieved through the co-pyrolysis of mulch film and cotton straw at a 1:4 ratio was estimated at 3.43 × 106 t.

After the co-pyrolysis of all mulch film and cotton straw at this ratio, the remaining cotton straw mass is 8.59 × 106 t. Following the estimation approach outlined in Table 2, the biochar produced from this remaining cotton straw could contribute to an additional net CO2e reduction of 9.34 × 106 t.

-

Xinjiang possesses abundant straw and mulch film resources, with maize straw, wheat straw, and cotton straw accounting for 93.5% of the total crop straw. The total quantity of collectible straw for maize, wheat, and cotton in 2023 was estimated at 2.64 × 107 t. The amount of mulch film used in Xinjiang has remained stable at 2.5 × 105 t, of which 2.03 × 105 t is recyclable.

Based on the total amount of collectible maize, wheat, and cotton straw, the biochar production potential was estimated at 8.76 × 106 t, corresponding to a net CO2e reduction of 2.05 × 107 t. Currently, wheat straw is primarily returned to fields, while maize straw is used as animal feed. Thus, the biochar production potential from cotton straw was estimated at 3.48 × 106 t, achieving a net CO2e reduction of 1.01 × 107 t. The pyrolysis of mulch film alone mainly produces gaseous and liquid products, resulting in a low biochar yield. The estimated biochar production from mulch film is 3.35 × 103 t, with a corresponding net CO2e reduction of 2.67 × 105 t. In contrast, the co-pyrolysis of all recyclable mulch film and cotton straw at a 1:4 mass ratio can yield 2.24 × 105 t of biochar, achieving a net CO2e reduction of 3.43 × 106 t. The subsequent pyrolysis of the remaining cotton straw can further contribute to a net CO2e reduction of 9.34 × 106 t.

This study provides a scientific evaluation of the biochar production potential and carbon reduction capacity associated with Xinjiang's major collectible crop straw and recyclable mulch film. The findings confirm that co-pyrolysis of mulch film and straw is an effective approach to enhance the resource utilization efficiency of agricultural waste. To support China's dual carbon goals, it is recommended that government departments provide policy and financial incentives to promote the co-pyrolysis of agricultural straw and mulch film for biochar production. Such efforts would ensure the efficient use of biochar derived from agricultural waste, which would contribute to reduced carbon emissions, improved soil quality, and enhanced agricultural productivity.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: all authors contributed to the study conception and design; Xiaorui Zhao: data collection and analysis; writting the first draft; Mengjiao Ji: data collection and analysis; Haoduo Bai: data collection and analysis; Lei Zeng: methodological approach; KuoK Ho Daniel Tang: language check of the paper; Ronghua Li: methodological approach, manuscript review; Chuanwen Yang: data colection; Jianchun Zhu: data collection; all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This study was funded by the Shaanxi Science and Technology Innovation Team Project (Grant No. 2025RS–CXTD–032).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

Quantities of the collectible major crop (maize, wheat, and cotton) straw and all recyclable mulch film were calculated.

The potential of biochar production and carbon emission mitigation was analyzed from the pyrolysis of major crops' collectible straw, recyclable mulch film, and cotton straw and mulch film mixture, respectively.

A recommendation for the integrated treatment of cotton straw and mulch film waste was proposed in Xinjiang's cotton-production regions.

-

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article.

- Copyright: © 2026 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao X, Ji M, Bai H, Zeng L, Tang KHD, et al. 2026. Potential of biochar production and carbon emission mitigation through co-pyrolysis of cotton straw and mulch film waste in Xinjiang, China. Agricultural Ecology and Environment 2: e003 doi: 10.48130/aee-0025-0016

Potential of biochar production and carbon emission mitigation through co-pyrolysis of cotton straw and mulch film waste in Xinjiang, China

- Received: 03 November 2025

- Revised: 24 December 2025

- Accepted: 30 December 2025

- Published online: 28 January 2026

Abstract: As China's largest crop and cotton production region, Xinjiang faces significant challenges in managing and reusing agricultural residues such as crop straw, cotton straw, and mulch film waste in the agricultural sector. To promote the efficient utilization of these residues and guide sustainable agricultural waste management practices in Xinjiang, this study calculated the collectible quantities of major crop straw (maize, wheat, and cotton) using grass-to-grain ratios and straw collectible coefficients, and determined the quantity of recyclable mulch film based on application and recovery rates. Furthermore, it assessed the biochar production potential and carbon reduction benefits through life cycle assessment (LCA). The pyrolysis of straw (maize, wheat, and cotton) and mulch film for biochar production yielded a net CO2e reduction of 2.05 × 107 and 2.67 × 105 t, respectively. Considering that wheat straw is primarily returned to fields and maize straw serves mainly as animal feed, the biochar production potential of cotton straw alone was estimated at 3.48 × 106 t, corresponding to a net CO2e reduction of 1.01 × 107 t. Although the pyrolysis of mulch film alone produces minimal biochar, co-pyrolysis of all recyclable mulch film with cotton straw at a ratio of 1:4 significantly improves biochar yield, generating 2.24 × 105 t of biochar and achieving a net CO2e emission reduction of 3.43 × 106 t. These results demonstrate that co-pyrolysis significantly enhances both biochar production and carbon emission reduction compared with the pyrolysis of mulch film alone. Overall, this study not only provides a scientific basis for the efficient utilization of major crop residues in Xinjiang but also offers practical insights for the integrated management of cotton straw and mulch film waste in cotton-producing regions.

-

Key words:

- Biochar /

- Cotton straw /

- Mulch film waste /

- Pyrolysis /

- Carbon emission