-

Climate change represents one of the most formidable threats to the stability of natural ecosystems, socio-economic development, and global sustainability[1−3]. Its multifaceted impacts are particularly devastating in developing countries, which are disproportionately vulnerable due to fragile institutional frameworks, limited adaptive capacity, and high dependence on climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture, water resources, and forestry[4,5]. The phenomenon of climate change is no longer a distant future possibility but a present-day reality with intensifying consequences[6,7]. Empirical evidence reveals a marked increase in climate variability and extremes over the past few decades. For instance, the summer of 2019 recorded temperatures 2.7 °C above the long-term average, making it the second warmest on record, and it was simultaneously among the driest years since 1767[8]. The scientific community attributes this intensification to the accumulation of greenhouse gases (GHGs), which trap solar radiation and warm the planet's surface[9,10]. While natural emissions from oceans, wetlands, and geological events contribute to the global GHG budget, anthropogenic sources largely from fossil fuel combustion, industrial operations, deforestation, and land-use changes have significantly disrupted the Earth's carbon equilibrium[11,12]. Yue & Gao's statistical analysis of emissions[12] confirms that while the natural system maintains a degree of self-regulation, anthropogenic activities place an unprecedented and unsustainable burden on this balance.

The environmental, economic, and human costs of climate change are no longer abstract concerns but quantifiable realities manifesting across regions and sectors[13−15]. The World Economic Forum's Global Risks Report (2019) highlighted environmental challenges, especially those driven by climate dynamics, as the most critical risks to global stability. These include increasingly frequent and severe heatwaves, droughts, floods, hurricanes, and sea-level rise, which cause widespread damage to infrastructure, displace populations, and reduce agricultural productivity. Alarmingly, heat-related deaths in 2018 surpassed fatalities from road accidents, underscoring the growing health burden of extreme temperatures[16,17]. Climate-induced biodiversity loss is another urgent concern, as rising temperatures alter habitats and threaten species with extinction. The 2019 Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) report warned that ecosystems are reaching irreversible tipping points, with cascading effects on food security, pollination services, and the global ecological balance[18,19]. The declining population of pollinators, in particular, jeopardizes agricultural yields and undermines food systems that rely on cross-species ecological interdependence[20,21].

Amid this worsening crisis, the global community has undertaken coordinated actions to limit temperature rise and mitigate associated risks. The 2015 Paris Agreement, which entered into force in 2016, sets a legally binding international target to cap global warming well below 2 °C and ideally under 1.5 °C relative to preindustrial levels[22,23]. Achieving this goal requires reaching net-zero greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050, necessitating structural transformations in the global energy system, land-use planning, industrial practices, and consumption behaviors[24,25]. These structural transitions imply a gradual yet irreversible shift away from coal, oil, and natural gas, combined with extensive afforestation and carbon sequestration efforts[25,26]. In this context, countries like those in the European Union have pledged to become climate-neutral by mid-century, recognizing the urgency of accelerating both mitigation and adaptation pathways[27,28]. However, translating these commitments into action, particularly in resource-constrained developing nations, requires more than political will. It demands a robust enabling environment supported by two key pillars: climate finance, which provides the necessary funding for climate action; and climate technology, which supplies the innovation and technical solutions essential for low-carbon, resilient development[29].

Despite significant global attention on these two pillars, critical research and policy gaps remain. First, there is a lack of integrative analysis that explores the synergy between climate finance and climate technology, especially in the context of adaptation and mitigation strategies in low- and middle-income countries[30]. Second, while numerous frameworks have been proposed at global and national levels, there is limited clarity on the governance challenges, institutional bottlenecks, and implementation barriers that hinder the scaling-up of climate technologies through financial mechanisms[31,32]. Third, there is insufficient empirical evidence and policy guidance on how to align international climate finance flows with country-level technology needs and adaptation priorities. As a result, developing countries often face fragmented support systems, delayed technology transfers, and inadequate financial mobilization, which together compromise the effectiveness of climate action[33,34].

In light of these challenges, this review aims to address the following research questions:

(1) How can climate finance be strategically mobilized and structured to support equitable and effective deployment of climate technologies for mitigation and adaptation?

(2) What are the key technological pathways currently available or emerging that can significantly reduce GHG emissions and enhance climate resilience, particularly in vulnerable economies?

(3) How can global and national governance structures be reformed or leveraged to improve access, coordination, and scalability of climate finance and technologies in developing countries?

Through a comprehensive synthesis of recent academic literature, international agreements, policy instruments, and case-based evidence, this review seeks to bridge existing knowledge gaps and propose actionable strategies that link financial flows with technological innovation. By foregrounding the interplay between finance and technology, it provides a novel lens to re-evaluate global climate response mechanisms and offers policy-relevant insights for accelerating climate-compatible development.

Furthermore, a comparative synthesis of existing reviews and the distinctive contributions of this study is presented in Table 1. This analysis clarifies how previous literature has addressed climate finance, technology pathways, and governance reforms in a fragmented manner and highlights the integrated value added by the present review. By systematically mapping existing knowledge, identifying persistent conceptual and operational gaps, and proposing a unified Finance–Technology–Governance (FTG) alignment framework, this study provides actionable insights for researchers, policymakers, and international climate institutions. The review aims to guide future policy design toward more equitable, efficient, and governance-responsive climate action.

Table 1. A summary of the comparative analysis of existing reviews, identified research gaps, and the distinctive contribution of this review, aligned with the research questions

RQ Existing reviews and their contributions Identified gaps in existing reviews Distinctive contributions of this review RQ1. How do existing climate finance mechanisms operate, and to what extent do they support equitable mitigation and adaptation needs in developing countries? • Chen et al. review institutional development of global climate finance architecture[39].

• OECD provides financial flows and mobilization trends[43].

• CPI assesses global climate finance volumes and gaps[122,184].

• Lee et al. examine environmental outcomes of climate finance[42].

• Nakhooda et al. evaluate multilateral fund effectiveness[109].

• UNDP explains access challenges and definitions[36].

• Nedopil & Sun analyze debt-for-climate swaps[38].

• Maltais & Nykvist and Nguyen & Le analyze green bond effectiveness[103,104].• Financial instruments (grants, concessional loans, guarantees, insurance, bonds) are treated separately rather than as a unified system.

• Lack of comparative analysis of mitigation vs adaptation finance outcomes across regions.

• Limited assessment of distributional equity, debt stress, and challenges faced by LDCs and SIDS (only partially addressed by UN/OHRLLS reports[180,181]).

• Insufficient integration of finance instruments with technology readiness and governance capacity.

• Limited cross-country synthesis linking institutional quality to finance absorption.• Develops an integrated typology of climate finance instruments (public, private, blended) directly linked to mitigation and adaptation functions.

• Provides a cross-regional comparative analysis (Africa, South Asia, LDCs/SIDS) using multiple evidence sources[36,42,43,81,122,180].

• Introduces an Finance–Technology–

Governance (FTG) Alignment Framework explaining context-specific variability in finance outcomes.

• Integrates equity, vulnerability, and debt-risk considerations into climate finance assessment, an overlooked dimension in prior reviews.RQ2. Which low-carbon and climate-resilient technology pathways are essential for 1.5–2 °C-aligned transitions, and how can climate finance accelerate their deployment? • IEA and IEA/IRENA reports outline solar, wind, hydro, and renewable energy transitions[24,62,111,112].

• Meylani et al. and other CCS/CCUS reviews synthesize deployment constraints[68,114].

• Wang et al. and Griscom et al. review blue carbon and natural climate solutions[70,71].

• Acosta-Silva et al. review renewable energy use in agriculture[169].

• Alharbi et al. provide global evidence on green finance and renewables[46].

• Khan & Khan and Sarku & Kranjac-Berisavljevic discuss technology adoption impacts in South Asia and Africa[171,172].

• Ojadi et al. discuss digital MRV, blockchain, and transparency tools[173].• Existing reviews examine technologies in silos (renewables OR CCS OR NbS OR digital systems).

• No cross-technology synthesis linking technology maturity (TRL) to appropriate financing instruments.

• Limited integration of digital MRV technology needs into climate finance discussions.

• Weak evidence connecting institutional absorptive capacity and technology uptake.

• Lack of prioritization of 'high-impact technology clusters' for maximizing mitigation/adaptation returns.• Provides cross-technology synthesis integrating CCS/CCUS, renewables, blue carbon/NbS, climate-smart agriculture, urban resilience technologies, and digital MRV tools.

• Proposes a finance-sensitive TRL pathway mapping grants → concessional finance → blended finance → private capital based on technology maturity.

• Identifies high-impact technology clusters where climate finance yields the highest marginal benefits (based on evidence from References[24,46,68,70,71,169,172]).

• Integrates digital technologies (AI, remote sensing, blockchain) into climate finance debates, addressing a major gap in prior literature[173].RQ3. What governance reforms and institutional architectures are required to strengthen climate finance access and accelerate technology deployment in developing countries? • Ha et al evaluate finance–technology alignment gaps in developing countries[30].

• Lakatos et al. and Kweyu et al. review institutional and governance barriers to technology uptake[31,32].

• Obahor & Asibor synthesize institutional bottlenecks in Africa[33].

• UNFCCC TEC/CTCN updates (2021–2023) detail governance requirements for technology transfer[8,97].

• Nega et al. examine inclusive governance for community adaptation[194].

• Tomlinson reviews accountability and governance failures in climate finance[198].

• Minas examines systemic global finance alignment with Article 2.1(c)[121].• Governance literature remains fragmented, with finance, technology transfer, and adaptation governance analyzed separately.

• No integrated framework linking governance quality, MRV systems, procurement capacity, and finance mobilization.

• Limited cross-country comparative evidence for SIDS, LLDCs, and high-vulnerability regions.

• No prior review links governance failures directly to technology under-absorption and finance inefficiency.

• Limited analysis of how institutional reforms improve access to climate finance.• Introduces a three-pillar governance architecture integrating regulatory systems, MRV governance, public-financial management, and technology deployment pathways.

• Synthesizes multi-region evidence (Africa, South Asia, SIDS) using

References[30−33,97,98,121,194].

• Explains how governance reforms—direct access modalities, de-risking frameworks, procurement transparency—improve finance mobilization and technology uptake.

• Presents the FTG Systems Integration Framework, offering a comprehensive governance-centric explanation absent in previous reviews. -

This review adopts a traditional narrative literature review approach to analyze the interlinkages between climate finance, technology pathways, and governance reforms. Given the multidisciplinary, evolving, and highly policy-oriented nature of this domain, the narrative review method allows for a comprehensive integration of conceptual frameworks, empirical evidence, institutional analyses, and documented country experiences. This approach is appropriate for synthesizing diverse strands of knowledge without imposing strict temporal, sectoral, or geographical boundaries.

Relevant literature was identified through structured searches in leading academic databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar, complemented by policy documents and technical reports from major international agencies such as the Green Climate Fund, Global Environment Facility, UNFCCC, UNEP, World Bank, OECD, and IEA. Search terms included combinations of: 'climate finance', 'green finance', 'blended finance', 'climate technology', 'technology transfer', 'renewable energy technology', 'adaptation technology', 'climate governance', 'institutional capacity', 'climate policy instruments', and 'decarbonization pathways'.

Inclusion criteria prioritized studies, reports, and analytical documents that explicitly engaged with (1) the structure, effectiveness, or barriers of climate finance; (2) technology deployment or transfer for mitigation and adaptation; or (3) governance mechanisms shaping financial and technological outcomes. Publications focusing solely on sectoral climate impacts or economic development without a finance–technology–governance dimension were excluded. The reviewed literature was organized thematically into three core categories aligned with the objectives of this study:

(1) mechanisms and instruments through which climate finance supports mitigation and adaptation,

(2) technology pathways that enable low-carbon and climate-resilient transitions, and

(3) governance architectures, institutional barriers, and enabling conditions that influence climate finance mobilization and technology uptake.

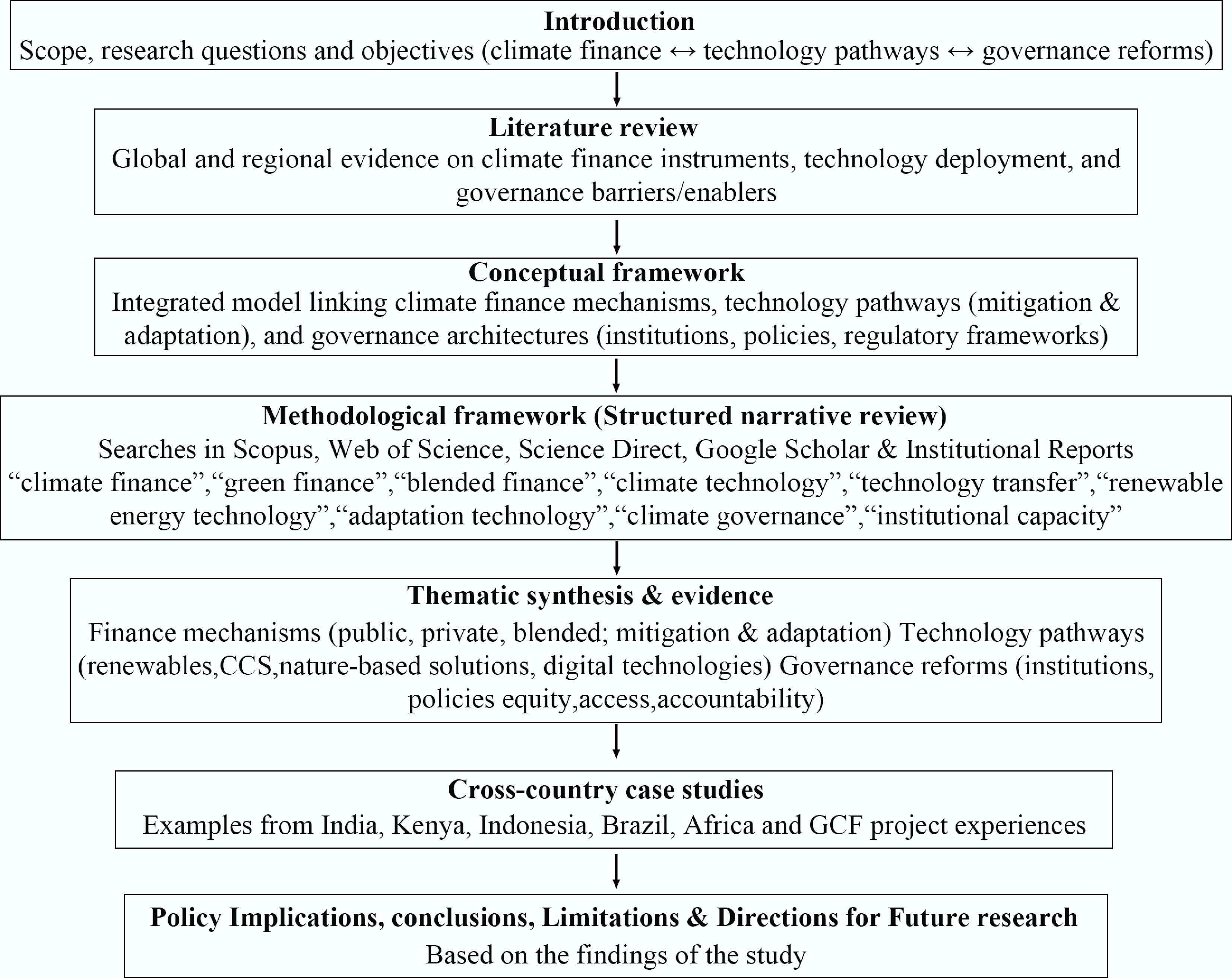

This thematic organization informed the conceptual framing and guided the narrative synthesis presented in the review. The roadmap of the study is provided in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Roadmap of the study. Flow diagram showing the structure of this review: (1) introduction and research questions, (2) literature review, (3) conceptual framework, (4) methodological framework (structured narrative review and search strategy), (5) thematic synthesis of financial mechanisms, technology pathways and governance reforms, (6) Cross-country case studies, and (7) policy implications, conclusions, limitations and directions for future research.

-

Climate finance is formally defined by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change[35] as 'local, national, or transnational financing drawn from public, private, and alternative sources of financing that seeks to support mitigation and adaptation actions to address climate change'. It plays a critical role in catalyzing the investments required by governments, corporations, and individuals to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and simultaneously build adaptive capacities to climate-related shocks. By directing financial flows toward environmentally sound technologies and infrastructure, climate finance aims to reorient the global economy toward a low-carbon development trajectory while enhancing resilience, particularly in climate-vulnerable regions.

Sources and instruments of climate finance

-

Climate finance derives from a diverse range of sources, public or private, national or international, bilateral or multilateral, each governed by differing institutional frameworks and priorities[36]. A variety of instruments exist within this financial landscape, tailored to meet different needs and capacities across geographies. One such instrument is the green bond, a debt security issued by both public and private institutions with an explicit commitment to fund environmental initiatives such as climate mitigation projects. Unlike general credit instruments, green bonds ensure the earmarking of proceeds for climate-related purposes[37]. Another key mechanism is the debt-for-climate swap, where the creditor country sells its foreign currency debt to a third party, often an NGO, which then negotiates with the debtor nation to redirect repayment toward mitigation or adaptation programs[38,39]. Guarantees, on the other hand, serve as pledges by a third party (usually a development bank or donor agency) to fulfil borrower obligations in the case of default, thereby de-risking climate investments[36]. Concessional loans also play a significant role by offering lower-than-market interest rates and longer repayment terms for climate-resilient infrastructure or adaptation technologies[40]. Complementing these are grants and donations, which constitute nonrepayable funding streams for climate emergency response, capacity building, and pilot interventions.

Among the major institutional sources of climate finance, the Green Climate Fund (GCF) stands out as the largest dedicated fund globally[36]. Established under the UNFCCC framework in 2010, the GCF supports developing countries in both mitigation and adaptation, particularly emphasizing the needs of the most climate-vulnerable populations. It plays an instrumental role in achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement by directing climate finance to low- and middle-income countries. Another prominent fund is the Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF), operated by the Global Environment Facility (GEF)[41]. The SCCF provides financial support for climate change adaptation, technology transfer, low-carbon energy, sustainable agriculture, and economic diversification in fossil-fuel-dependent economies. Parallel to this, the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF), also managed by the GEF, targets around 50 countries designated by the UN as least developed, focusing on the implementation of National Adaptation Plans[41]. The UN-REDD Programme, launched in 2008, aims at reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+) in developing nations while strengthening forest governance and enhancing co-benefits like biodiversity and community development[36]. In addition to multilateral instruments, several bilateral climate finance agencies have made significant contributions. Institutions such as the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the Global Climate Change Alliance+ (GCCA+) of the European Union, and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) are examples of donor-driven bilateral mechanisms that blend technical assistance, concessional financing, and policy support to enable climate transitions[36].

Activities supported by climate finance

-

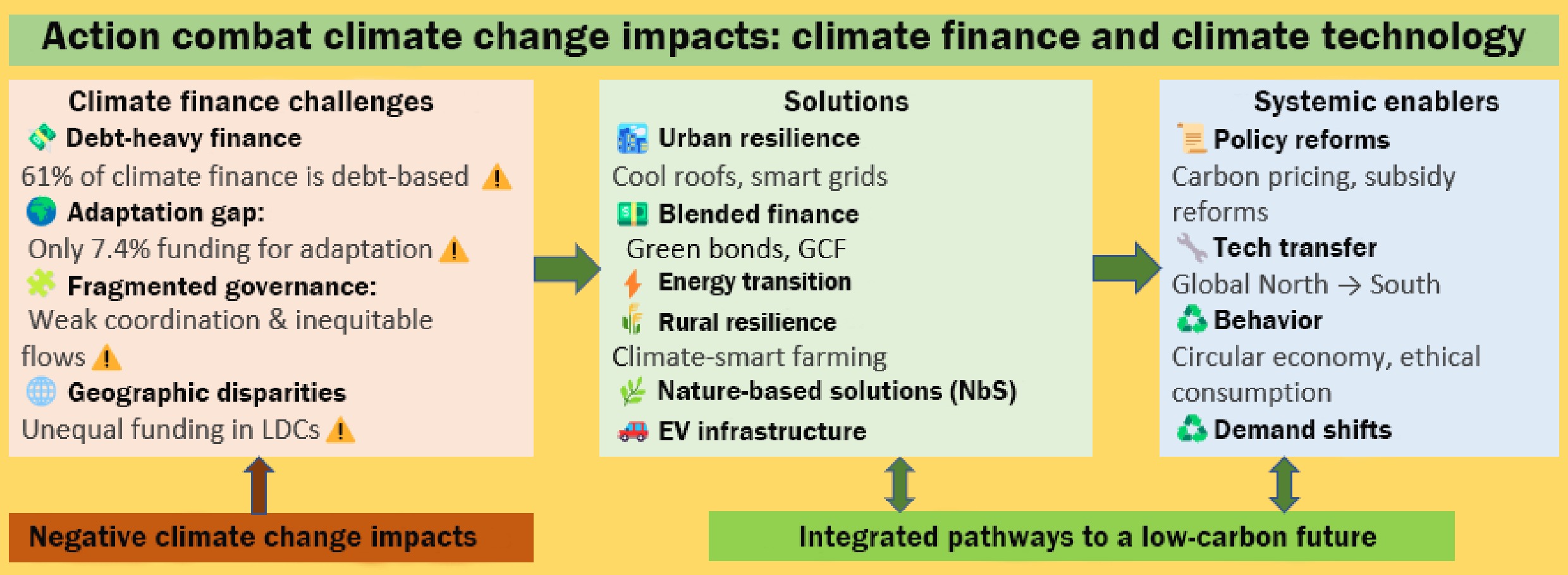

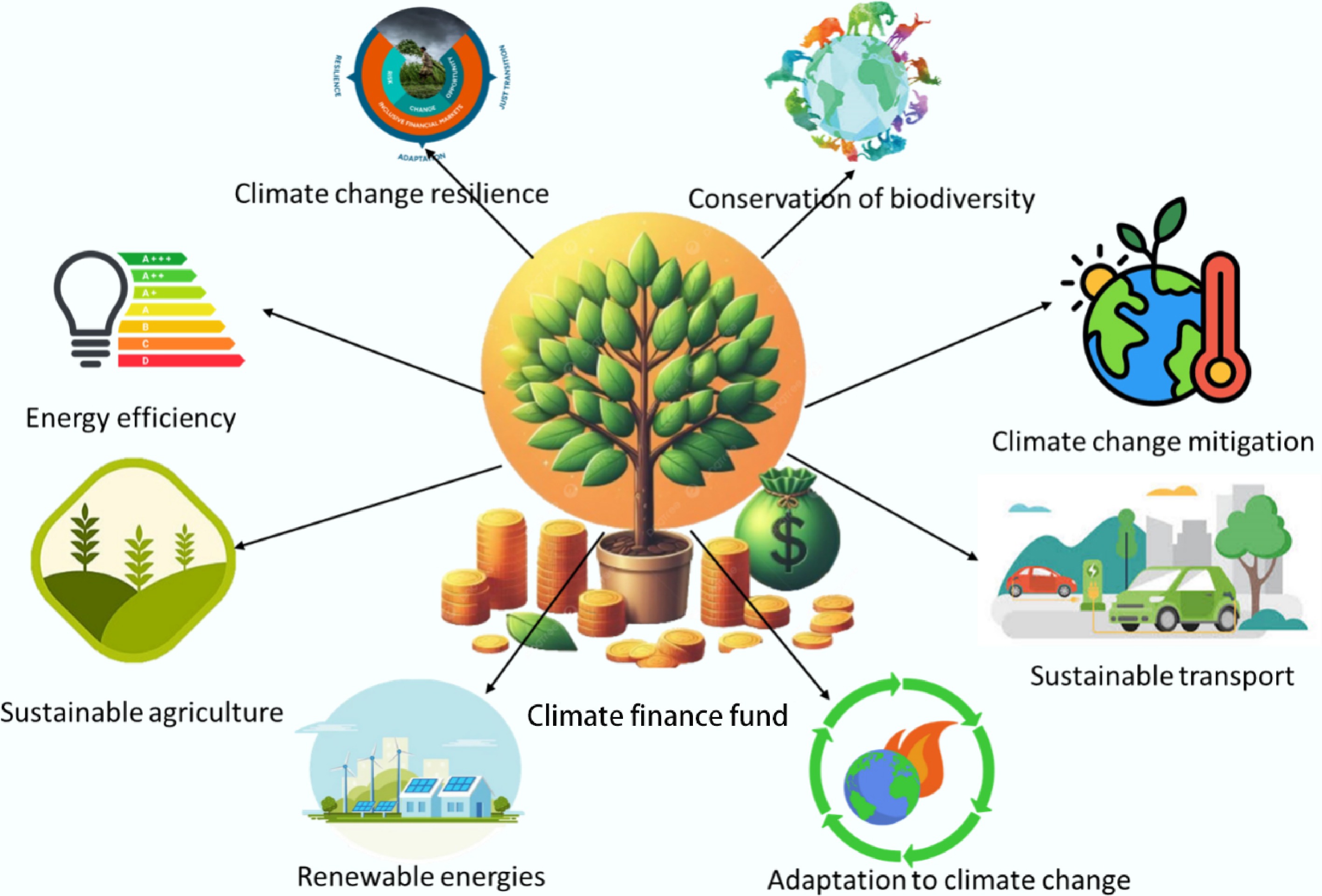

Climate finance supports a diverse portfolio of interventions targeting both mitigation and adaptation goals[42,43]. As depicted in Fig. 2, these activities span sectors such as energy, agriculture, land use, transportation, and waste management, reflecting the multifaceted nature of climate risk and response. One of the core areas of support involves renewable energy deployment. Financial flows are directed toward the establishment of solar, wind, hydro, and biomass-based energy systems, enabling a reduction in carbon intensity and enhancing energy access in underserved regions[44,45]. In parallel, climate finance facilitates the uptake of energy efficiency technologies in industrial and domestic settings by encouraging retrofitting and innovation[46]. This not only reduces emissions but also brings down operational costs[43,47].

The agricultural sector also benefits significantly from climate finance, with investments in sustainable practices such as climate-smart agriculture, conservation tillage, organic inputs, agroforestry, and improved irrigation systems[48,49]. These approaches enhance food security while preserving soil health, water resources, and biodiversity[29]. Climate adaptation and mitigation activities further include reforestation, afforestation, and land restoration programs, aimed at both carbon sequestration and ecosystem resilience[50].

Urban and transport infrastructure are also transformed through climate finance[48]. As Fig. 2 illustrates, electric vehicles and the development of low-emission public transportation systems are promoted to reduce reliance on fossil fuels. Simultaneously, climate finance encourages sustainable urban planning and green building initiatives[51]. The concept of a circular economy is another critical focus area, with funding mechanisms supporting waste minimization, recycling, and renewable material use to improve resource efficiency[52]. Through these comprehensive interventions, climate finance facilitates not only a reduction in greenhouse-gas emissions but also socio-economic co-benefits such as employment generation, improved health, and enhanced adaptive capacity in vulnerable communities[53].

Challenges in climate finance

-

Despite the considerable progress in mobilizing climate finance, several persistent challenges undermine its effectiveness, equity, and accessibility. A key concern is the inconsistency in disbursement rates. Climate finance often reaches recipient countries more slowly than traditional development aid, creating delays and uncertainty in project implementation[54]. This lack of predictability diminishes trust and constrains the integration of climate interventions into long-term development plans. Another critical issue lies in the composition of climate finance. A disproportionately high share of over two-thirds of climate finance is disbursed as loans rather than grants, far exceeding the average loan proportion of 52% in overall development assistance to developing countries[54,55]. This raises concerns about debt sustainability, particularly as the share of loan-based finance directed toward low-income countries at high risk of external debt distress has risen significantly over the past decade[56]. The financial burden created by such lending practices runs counter to the calls from climate-vulnerable nations for more affordable, grant-based support.

Additionally, the proliferation of climate finance providers has paradoxically resulted in greater project fragmentation and a decline in project scale. Although diversity in financing sources is generally seen as positive, the increasing number of small, uncoordinated initiatives hampers transformative outcomes and places a heavy administrative burden on recipient institutions. Coupled with high transaction costs, this fragmentation reduces the efficiency and scalability of climate interventions[57]. A further concern is the allocation of mitigation finance. An increasing proportion, now estimated at nearly one-third of mitigation funding, is unassigned to specific countries[54]. This trend raises questions about the equitable distribution of benefits and responsibilities for global public goods like climate stabilization. It also challenges principles of accountability and country ownership in climate finance.

Moreover, there is a noticeable lack of integration of climate finance into national budgets. Most funding continues to be channeled through project-based mechanisms that circumvent domestic financial systems, limiting national control and coordination[55]. Although direct access modalities have been proposed to enhance recipient ownership, their scope and impact remain limited. Finally, the impact of climate finance is poorly documented. Despite the growing volume of climate-related financial flows, the field suffers from a dearth of high-quality evaluations and systematic impact assessments, particularly in comparison to other sectors of development finance. This deficit hinders evidence-based policymaking and limits opportunities for adaptive learning[54,57]. The following section will expand on how targeted financial mechanisms can be more effectively designed and implemented to promote circular economy practices in the livestock sector, a critical nexus for climate action, sustainable agriculture, and financial innovation.

Renewable energy technologies and their transformative role

-

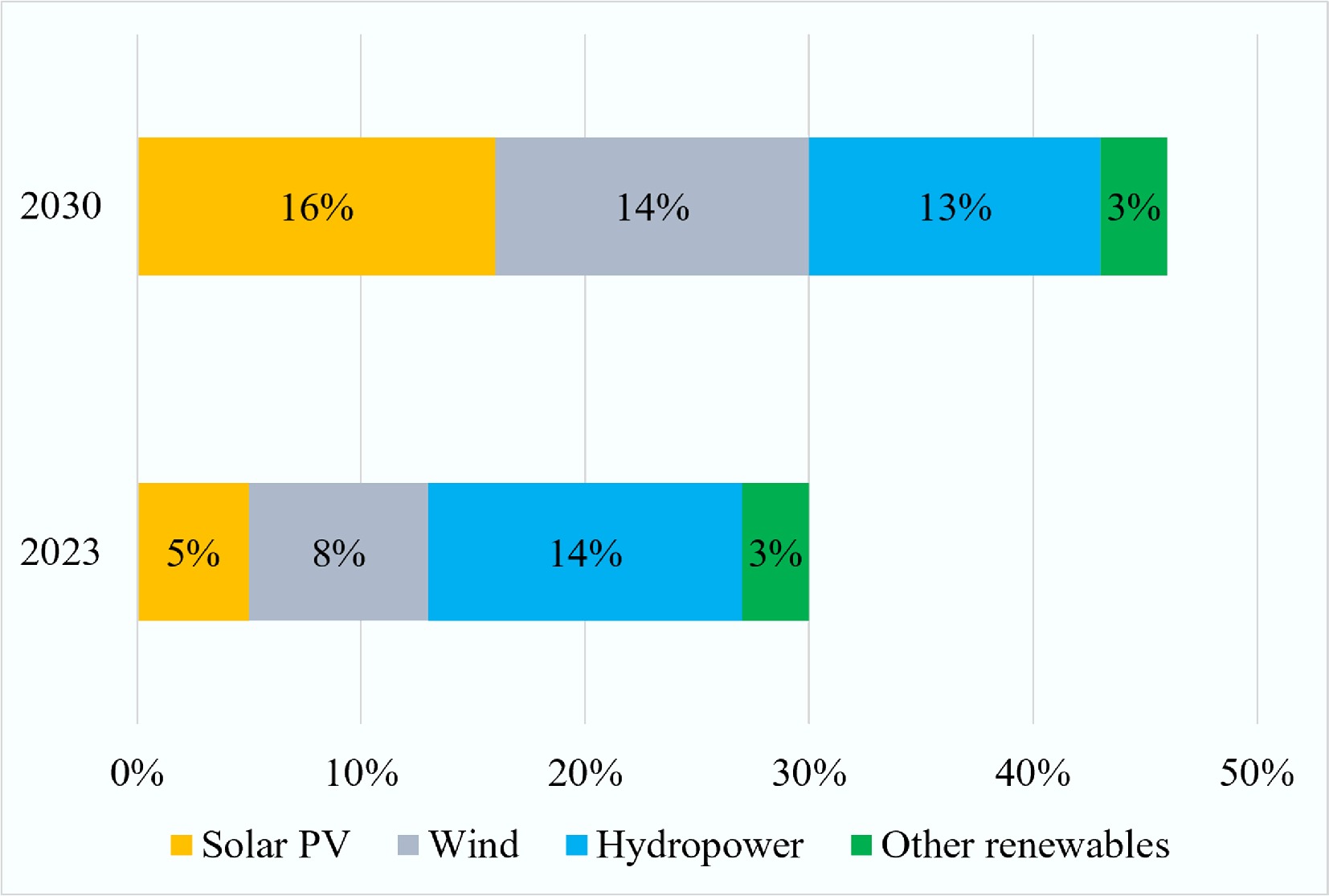

Climate technologies encompass a wide array of tools and innovations aimed at mitigating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and strengthening adaptation to the impacts of climate change. Among them, renewable energy systems such as solar photovoltaics (PV), wind turbines, hydropower facilities, and biomass-based energy form the backbone of global mitigation strategies[56,58]. These energy solutions reduce dependence on fossil fuels and also significantly decrease the carbon footprint of electricity generation[56]. Technological progress in these domains is steadily reshaping global energy portfolios, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

The trajectory of renewable electricity generation suggests a sharp rise in solar and wind energy shares by 2030, increasing from 5% to 16% and from 8% to 14%, respectively. Hydropower, though historically dominant, is expected to witness a marginal decline from 14% to 13%, while other renewables are projected to maintain their current share of 3%[58]. This changing composition marks a deliberate pivot toward less carbon-intensive energy systems and highlights the growing momentum of climate technologies in driving sustainable transitions.

Solar energy has emerged as a cornerstone of renewable innovation. As a nonpolluting, inexhaustible energy source, it plays a critical role in decarbonizing electricity generation[59]. Modern PV systems now benefit from bifacial modules and perovskite-based cells, which enhance both energy capture and storage efficiency[60,61]. Notably, 2023 witnessed a record 25% increase in solar PV output, reaching over 1,600 terawatt-hours, representing the fastest growth among all renewable sources that year[62]. Similarly, wind energy is experiencing a rapid ascent in both onshore and offshore deployment. New turbine designs with larger rotor diameters and more aerodynamic blades are increasing capacity factors while lowering costs[63,64]. Offshore wind, in particular, is proving advantageous due to higher wind consistency and minimal land-use conflicts[65]. The technology added 265 terawatt-hours to global power generation in 2022 alone, bringing the total to over 2,100 terawatt-hours[62]. Hydropower continues to serve as a critical pillar in renewable infrastructure, particularly for its role in grid stability and energy storage. Although its relative share in global electricity is gradually diminishing, innovations in pumped-storage systems and run-of-river configurations are revitalizing its relevance[66,67]. In 2022, hydropower generation rose by 70 terawatt-hours to 4,300 terawatt-hours globally[62]. Bioenergy adds another critical dimension, primarily through the conversion of organic materials into fuel and power. Modern bioenergy, particularly second-generation biofuels derived from nonfood biomass, is reducing the competition with agricultural food systems and offering near-zero carbon emissions[56]. Accounting for over 55% of renewable energy (excluding traditional uses), bioenergy contributes more than 6% of global energy demand[62]. These advancements collectively reflect a dynamic shift toward a diversified, low-carbon energy future, integral to achieving long-term climate objectives.

Carbon capture and mitigation technologies

-

Beyond the transition to renewable energy, climate change mitigation also hinges on emerging carbon capture and storage (CCS) solutions. These technologies serve to intercept CO2 emissions either at the source or directly from the atmosphere and store them in stable geological or biological reservoirs[68]. As emphasized by Holz et al.[69], CCS is poised to play a decisive role in achieving global net-zero targets by mid-century. CCS technologies are broadly classified into biological and geological approaches. Biological sequestration leverages the natural carbon absorption capacity of ecosystems such as forests, grasslands, wetlands, and oceans. Notably, wetlands and coastal systems have demonstrated higher carbon sequestration rates per hectare compared to terrestrial forests, rendering them critical assets in natural climate solutions[70,71].

Geological carbon capture, on the other hand, involves the injection of compressed CO2 into subterranean formations such as saline aquifers and depleted oil and gas reservoirs[72,73]. These geological sinks offer vast potential for long-term storage. For example, the Endurance aquifer beneath the North Sea, a formation approximately the size of Manhattan, has been identified as a high-capacity CCS site[74]. Similar progress has been made in North America, where Alabama's Citronelle Project successfully stored over 150,000 tonnes of CO2 per year during its operational phase, using adjacent industrial CO2 sources[75,76]. Technological innovations are also introducing engineered carbon capture solutions. One of the most promising examples is the deployment of large-scale air purification towers in China, capable of filtering over 353 million cubic feet of air daily[77,78]. These towers leverage solar-heated glass chambers to accelerate air movement and filtration, creating a localized greenhouse effect to trap and process airborne pollutants. Prototypes suggest scalability, with new towers designed to purify air at the level of a small urban population[79,80].

In addition, chemical engineering is making breakthroughs in the design of novel absorbents such as ionic liquid compounds with unique molecular properties that exhibit high CO2 affinity[81,82]. Their two-dimensional structures allow for enhanced gas capture efficiency, while their low volatility and tunable chemistry render them both effective and environmentally benign. This line of innovation presents a promising pathway for the next generation of CCS solutions, particularly in sectors where direct decarbonization remains technologically constrained. Altogether, these developments in carbon management underscore the need for integrated climate strategies that combine emission reduction, renewable energy expansion, and negative emission technologies. As the carbon budget tightens, the role of CCS, complementing renewables, will be indispensable in offsetting residual emissions and achieving climate neutrality[69,73].

Disaster management and monitoring

-

The prediction and prevention of natural disasters remain among the most complex tasks in climate resilience efforts. Nonetheless, the imperative of proactive disaster management has grown substantially, given the escalating frequency, scale, and unpredictability of extreme events. Disasters not only threaten human lives and infrastructure but also impede socio-economic progress and exacerbate vulnerabilities across developing regions[83,84]. The increasing variety and intensity of such hazards necessitate state-level disaster governance informed by scientific planning and technological integration. Among the most transformative innovations in this domain is the use of satellite remote sensing, which provides continuous, high-resolution imaging of the Earth's surface[85]. Its capacity for real-time and wide-swath observation makes it indispensable for responding to weather-related disasters such as floods, cyclones, and landslides. Particularly in inaccessible terrains and during adverse climatic conditions, remote sensing technologies have enabled timely situational awareness and effective mobilization of emergency services[86−88]. By combining satellite imagery with spatial data analytics, authorities can delineate disaster-prone zones, assess post-disaster damage, and identify potential shelters, improving the speed and precision of relief efforts[89]. Advanced applications now involve Geographic Information Systems (GIS) integrated with multi-temporal datasets to support both anticipatory action and recovery operations[88,90].

The recent convergence of satellite remote sensing with artificial intelligence (AI) further amplifies disaster management capabilities. With growing volumes of Earth observation data, AI algorithms are being used to automate change detection, map flooded areas, assess structural damage, and predict hazard propagation in near real-time[91]. In the evolving space sector, there is also a paradigm shift from large, government-funded satellites to microsatellite constellations launched by private firms. These constellations offer the advantage of high-frequency, low-cost monitoring, addressing both temporal and spatial limitations[85]. The Korean-developed microsatellite constellation No. 1 exemplifies this trend toward decentralized, agile space infrastructure[85,92]. This new space age is marked by increased commercial engagement, democratized access to space-based data, and cross-sectoral collaborations in disaster analytics. As AI-driven systems continue to ingest and process multi-source geo-spatial data, they are being deployed not only for situational mapping but also for strategic planning, such as simulating evacuation routes, modelling infrastructure vulnerabilities, and identifying resource bottlenecks[89]. These advances signify a transformative moment in disaster governance, where climate-resilient infrastructure is supported by intelligent monitoring systems that integrate Earth observation, big data, and predictive analytics to enable real-time and anticipatory disaster response.

Technology transfer and capacity building

-

Technology transfer constitutes a cornerstone of climate change mitigation and adaptation, especially for enabling low-emission development in developing economies. It facilitates the diffusion of environmentally sound innovations, ranging from renewable energy systems and resilient infrastructure to early warning systems and sustainable agriculture techniques[93,94]. The policy landscape supporting this process is structured under several global mechanisms initiated through multilateral agreements. One foundational framework is the Technology Transfer Framework established under the Marrakesh Accords in 2001, followed by the Poznań Strategic Program in 2008 and the establishment of the Technology Mechanism during the Cancún negotiations in 2010. The Technology Mechanism comprises two main bodies: the Technology Executive Committee (TEC) and the Climate Technology Centre and Network (CTCN). The TEC, composed of 20 expert members, plays a pivotal role in identifying national technology needs and recommending policies that promote climate technology development and diffusion. It engages with stakeholders through meetings, workshops, and publications such as TEC Briefs to share knowledge on best practices and policy pathways for technology adoption, particularly in adaptation planning and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs)[95].

The CTCN acts as the operational arm of the Technology Mechanism, hosted by UNEP and supported by a consortium of 14 leading institutions. Through its extensive network of over 700 partner organizations, the CTCN offers technical assistance, capacity-building, and policy advisory services tailored to country-specific climate challenges. As of March 2022, the CTCN had served 108 countries, facilitating the rapid transfer of low-carbon and climate-resilient technologies[96]. Its support includes enabling frameworks, technology customization, and access to a broad repository of climate innovation data[97]. Several other international institutions complement these efforts. The UNEP Copenhagen Climate Centre (UNEP CCC), formerly UNEP DTU Partnership, is a leading research entity focused on supporting developing countries through knowledge generation and system-level innovation[98]. It specializes in market-based approaches, policy integration, and transition strategies that catalyze climate technology diffusion[99]. United Nations Office for South-South Cooperation (UNOSSC) plays a critical role in matching technological solutions from one developing region to another, fostering adaptive learning across similar ecological and socio-economic conditions. Such collaboration helps ensure contextual appropriateness, cost-effectiveness, and community acceptance of transferred technologies[100].

United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) further supports industrial-scale climate technology adoption through technical cooperation, quality standards, and policy advisory services[101]. By building institutional networks and supporting technology deployment, UNIDO addresses barriers to innovation diffusion and fosters inclusive climate-resilient industrial development. Similarly, the UN Technology Bank for LDCs, operational since 2018, focuses on strengthening science and innovation systems in the Least Developed Countries. It facilitates multi-sectoral cooperation, identifies country-relevant technologies, and supports national innovation ecosystems[102]. Finally, the World Trade Organization (WTO) underpins climate technology dissemination through its legal framework, particularly the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement. Article 7 of TRIPS emphasizes that intellectual property rights should encourage the promotion of technological innovation and facilitate technology transfer, benefiting both producers and users of technological knowledge[100,101]. This balance is critical for equitable access to climate technologies while maintaining incentives for innovation. Table 2 summarizes the whole climate finance scenario in a shorter frame.

Table 2. Climate finance landscape

Section Key focus Instruments Key institutions Challenges Ref. Sources and instruments Types and structures of climate finance Green bonds, debt-for-climate swaps, guarantees, concessional loans, grants UNDP, GCF, GEF (SCCF, LDCF), UN-REDD, JICA, USAID Fragmentation, slow disbursement, over-reliance on loans [103−105] Activities supported Sectors receiving climate finance Renewable energy, energy efficiency, sustainable agriculture, reforestation, EVs, circular economy OECD, World Bank, GEF, IADB Benefits: GHG reduction, improved health, food security, jobs [106−108] Challenges in climate finance Barriers to efficient climate finance Delayed disbursement, loan-heavy finance, fragmented projects, poor integration with budgets CGD, ODI, IPCC, Yale Environment Review Lack of impact assessments, low national ownership, inequitable mitigation finance distribution [43,56,109] Renewable energy technologies Role of renewable energy in climate mitigation Solar PV, wind turbines, hydropower, biomass IEA, IPCC, IRENA, DOE Fastest growth in solar; innovation in bifacial/perovskite PV, turbine efficiency [43,110,111] Carbon capture technologies Carbon capture & storage (CCS) methods Biological and geological CCS, CO2 injection, air purification towers, ionic liquids IEA, IPCC Vital for net-zero goals; supports hard-to-decarbonize sectors [113−115] Disaster management and monitoring Climate-resilient disaster response via technology Satellite remote sensing, GIS, microsatellite constellations, AI-driven mapping NDMI, MDPI, Nature Sci. Reports, Korean Space Agency Real-time hazard monitoring; shift to decentralized, private-led space infrastructure [89,116] Technology transfer and capacity Technology diffusion mechanisms and institutional support for developing nations CTCN, TEC, UN Technology Bank, UNEP CCC, UNOSSC, UNIDO UNFCCC, WIPO, WTO, TRIPS Supportive frameworks for tech transfer, IP rights balance, capacity-building focus [43,117] -

Unlocking the full potential of climate action requires integrating technology and proper financing mechanisms. Climate finance may propel scalable, high-impact interventions by coordinating financial instruments with cutting-edge technology, such as carbon capture systems, precision agriculture, and renewable energy systems. Green bonds, de-risking tools, and blended finance structures can all help raise private funds for tech-enabled adaptation and mitigation initiatives. Transparency, efficacy, and accountability in the delivery of climate funding are also improved by investments in digital infrastructure, climate information systems, and intelligent monitoring technologies. This collaboration guarantees that finance flows are based on long-term resilience and sensitive to technology advancements, in addition to expediting low-carbon transitions.

Integrating finance and technology for climate resilience

-

International climate finance plays a pivotal role in supporting the transition of vulnerable countries, particularly in the Global South, toward climate-resilient development (CRD) pathways while also addressing the overarching goal of emissions reduction[118,119]. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change[43] underscored the necessity of aligning financial flows with low-carbon and climate-resilient development trajectories. This imperative was reinforced under Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement, which explicitly advocates for the reorientation of global financial systems toward climate-aligned investments[120,121]. However, recent reports, including the UNFCCC[120] Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan, emphasize that achieving this transformation demands a systemic overhaul of existing financial institutions, governance architectures, and capital allocation practices[120,122]. The estimated requirement of USD four to six trillion annually to meet low-emissions targets underscores the sheer magnitude of this challenge[43,122]. Despite these projections, adaptation finance remains significantly underfunded, with most funds skewed toward mitigation rather than building resilience[123]. The integration of financial systems and climate technologies is critical to developing scalable interventions that address the multidimensional risks posed by climate change[124,125]. Technological innovation alone cannot suffice without the parallel development of financial frameworks that facilitate its adoption, especially in sectors that are capital-intensive or face heightened climate vulnerability[118,126].

Synergistic climate strategies and innovative instruments

-

Creating synergistic strategies that integrate finance with climate technology involves the careful orchestration of capital allocation, regulatory incentives, and market-based instruments to facilitate widespread adoption[126,127]. Instruments such as green bonds and climate insurance illustrate the strategic intersection of financial innovation and technological deployment[128,129]. Green bonds, for example, have emerged as a robust tool for channeling capital toward climate-resilient infrastructure. The genesis of this instrument can be traced to the IPCC's pivotal report, which catalyzed institutional interest in climate-related investments. The World Bank pioneered green bonds in 2008, followed by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) in 2010, signaling the market's institutionalization. According to Mejía-Escobar et al.[130], green bonds exhibited an annual growth rate of 49% in the 5 years leading up to 2021, with market projections suggesting issuances exceeding US

${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ Climate insurance, another financial innovation, offers adaptive risk management for weather-related shocks. These mechanisms transfer risk from governments and vulnerable communities to insurance pools and capital markets[124,129]. Hellmuth et al.[134] emphasized that climate insurance provides rapid liquidity for recovery following extreme events. The efficacy of such schemes is evidenced by Vanuatu, which received US

${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ The role of public-private partnerships (PPPs) and bridging integration gaps

-

PPPs are emerging as central to financing and operationalizing low-carbon, climate-resilient (LCCR) infrastructure. Initially conceived as procurement models in the early 1990s[137], PPPs have evolved into robust institutional frameworks for resource mobilization and infrastructure delivery[138,139]. Casady et al.[141] highlight that PPPs facilitate collaborative governance that combines public oversight with private-sector efficiency, innovation, and capital. Globally, PPPs have been mobilized to deliver infrastructure for climate mitigation and adaptation, particularly in sectors such as energy, water, and transportation. Nevertheless, structural and operational barriers persist. Governments often face fiscal constraints, political costs, and institutional inertia that hinder their capacity to undertake capital-intensive LCCR projects[142,143]. This includes reluctance to fund unproven technologies, redistributive concerns, and limited access to subnational debt instruments[144]. Private investors, on the other hand, demonstrate a preference for bankable mitigation projects like renewable energy over adaptation projects, which are often characterized by uncertain returns and high systemic risk[140,145,146]. Cautions should also be taken against potential private sector cooptation of environmental narratives, raising concerns that market-driven solutions may reinforce existing inequities[143,147,148].

Despite these limitations, the imperative for collaborative approaches continues to grow. Multilateral agreements such as the Paris Agreement (2015) and Glasgow Climate Pact (2021), along with institutions like the UNEP[149] and OECD[150], advocate for expanding the role of private finance in delivering climate outcomes[146,151]. PPPs are thus positioned not only as mechanisms for capital mobilization but also as platforms for risk-sharing and innovation diffusion[138,146]. Their structured agreements provide predictability in uncertain climate scenarios and promote transparent allocation of climate-related liabilities, thereby enhancing investor confidence[138,142]. Addressing persistent integration gaps remains critical. Disconnected policymaking between technology developers, financiers, and regulators hampers cohesive solutions. Risk aversion among institutional investors delays funding for emerging technologies, while financial barriers in developing economies inhibit small businesses and communities from adopting climate innovations[142,143,146]. Furthermore, the lack of supportive policies and market guarantees limits the scalability of novel financial products such as blended finance or outcome-based instruments[142,146].

Building a climate-resilient future requires a systemic closing of these gaps through institutional reform, coordinated governance, and inclusive capacity development. Ensuring knowledge exchange, technical support, and investment readiness is fundamental. This entails establishing robust enabling environments with policy certainty, fiscal incentives, and targeted public support that crowds in private capital[138,148]. Equally vital is enhancing regional and local institutional capacities to adapt climate technologies contextually and sustainably[142,143]. Through multi-level cooperation among governments, private actors, and civil society, finance and technology can be meaningfully integrated to drive transformative climate resilience globally[138,146].

-

Analyzing global case studies and empirical data is crucial for understanding the real-world effectiveness of climate finance and technology deployment. These examples not only demonstrate successful transitions toward low-carbon systems but also reveal best practices, pitfalls, and scalable innovations that enhance resilience, equity, and sustainability. This section draws from cross-continental evidence to highlight the multidimensional impacts of financial mechanisms and climate technologies (Table 2).

Success stories in climate finance and community-based innovations

-

Several prominent examples show how targeted climate finance can drive significant ecological and socio-economic transformation. Tesla Inc., a global leader in electric vehicles (EVs), leveraged private capital and favorable policy frameworks to disrupt the automobile sector. Its rapid growth demonstrates the capacity of green finance to unlock markets and shift industry trajectories toward sustainability[152,153]. Similarly, Ørsted's transition from fossil fuels to offshore wind generation in Denmark exemplifies the use of green bonds and syndicated loans to align corporate strategies with climate goals[154,155]. The Indian agri-tech startup DeHaat (Green Agrevolution Group) has successfully promoted climate-resilient and organic farming through bundled green financing, benefiting thousands of smallholders[156,157].

In real estate, The Edge building in Amsterdam, widely recognized as the world's greenest office space, illustrates how ESG-linked finance and smart technologies can produce net-positive energy outcomes while boosting property values and tenant satisfaction[158,159]. In Bangladesh and other parts of the Global South, BRAC's green microfinance initiatives demonstrate how small loans can enable sustainable agriculture and decentralized solar energy, reducing poverty while enhancing environmental outcomes[160,161]. Localized community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) models have also proven highly effective. From the Caiman Ecological Refuge in Brazil to Tanzania's Mpingo and Yaeda Valley initiatives, public-private partnerships have mobilized climate finance through ecotourism, REDD+, and carbon markets[162,163]. These models blend ecological restoration with livelihood enhancement, particularly among indigenous communities and marginalized groups. Projects such as the Shea and PACOFIDE initiatives in West Africa, the Alto Mayo coffee program in Peru, and Kenya's Mara Naboisho Conservancy further illustrate how local stewardship, when coupled with climate-linked finance, generates durable environmental and social benefits[164−166]. Table 3 showcases some successful case studies of climate finance and community-led innovations from all over the globe, highlighting their technological, environmental, financial and socio-economics aspects and components.

Table 3. Comprehensive global case study

Initiative/country Financial mechanism Technology/practice Stakeholders involved Environmental impact Economic impact Social impact Ref. Tesla (global) Private equity, carbon credits Electric vehicles (EVs), lithium batteries (decline in battery cost by 87% by 2010–2022) Investors, regulators, consumers CO2 emission reduction (more than 40 million tons per year) Industry transformation, EV affordability Behaviour change, job creation [152,153] Ørsted (Denmark) Green bonds, climate loans Offshore wind (7.6 GW installation), power grids Gov., banks, utilities Fossil fuel replacement Profitable green investment Clean energy access (Renewable energy's share rose substantially, expanding from 17% in 2006 to 90% by 2023) [154,155] DeHaat (India) Impact investment, agri-loans Organic and digital agriculture Farmers, investors, NGOs Soil health, lower emissions Yield rise (10 to 25%), lower input cost Farmer empowerment (supported two million farmers) [156,157] The Edge (Netherlands) Sustainable real estate finance Solar PV, smart energy tech Developers, tenants Net energy positive, carbon neutral (reduction of emission of 85 tons CO2 per year) Asset value ↑, O&M cost ↓ Worker wellness, innovation [158,159] BRAC (global south) Green microfinance (given to seven million stakeholders) Solar homes, climate-smart farming MFIs, rural poor Deforestation ↓, renewable access ↑ Household income ↑ Financial inclusion [160,161] Caiman Refuge (Brazil) Ecotourism revenue Biodiversity restoration (53,000 hectares area protected) NGOs, local tribes Jaguar habitat recovery Community infrastructure Environmental education [162,163] Shea and PACOFIDE (Africa) Blended finance, CSR funds Agroforestry, sustainable processing Women's co-ops, buyers Tree cover ↑, carbon sinks Global market entry Gender equity [164−166] Tmatboey (Cambodia) Revenue recycling Avian protection, eco-tourism Villagers, tourists Forest conservation Tourism income ↑ Eco-governance [167] Mpingo (Tanzania) REDD+, timber certification Controlled harvesting Locals, NGOs, buyers Carbon sequestration ↑ Certified timber premium Community training [162,163] Yaeda Valley (Tanzania) Carbon credits (50,000–70,000 tons CO2/year) Wild honey, forest protection Hadza community, investors Ecosystem

services ↑Product sales ↑ Indigenous land rights [162,163] Alto Mayo (Peru) PPPs, Starbucks funds Shade coffee, agroforestry (182,000 hectares forest area conserved) Gov., farmers, brands Deforestation ↓ Carbon credits, coffee yield ↑ Fair trade, resilience [164−166] Katingan Mentaya (Indonesia) Verified offsets Peatland restoration (149,800 hectares restored) Local villages, buyers Methane emission ↓ Carbon revenue Infrastructure upliftment [168] Northern Rangelands (Kenya) REDD+, ecotourism Wildlife monitoring Conservancies (6.3 million hectares), donors Habitat preservation Tourism and carbon finance Youth jobs, anti-poaching [162,163] Mara Naboisho (Kenya) Conservation leases Wildlife conservation, eco-tourism Maasai owners, tour ops Biodiversity protection Eco-tourism profits Cultural sustainability [164−166] Impact of climate technology deployment

-

Climate technology contributes directly to emission reductions, resource efficiency, and biodiversity conservation. Solar, wind, and agroecological technologies have significantly reduced greenhouse-gas emissions by displacing fossil fuels and enhancing carbon sequestration[169,170]. Advances in water purification, precision farming, and clean cooking have improved environmental quality and health outcomes in underserved regions[171]. Economically, these technologies have stimulated green job creation, reduced operating costs, and opened new market opportunities[172]. From efficient irrigation systems to digital agri-platforms and AI-enabled monitoring, technology adoption has enhanced productivity and climate resilience[89]. Furthermore, climate technologies have strengthened national energy security and mitigated the risks of global price volatility[170]. Socially, climate technologies have enabled inclusive development. Projects integrating IoT, blockchain, and remote sensing have promoted transparency and accountability in climate finance[173]. Moreover, the alignment of climate innovations with corporate social responsibility (CSR) and ESG mandates has improved brand reputation and compliance.

-

The global governance landscape for climate finance is characterized by systemic imbalances in fund allocation, access, and structural design. Despite significant commitments from both public and private actors, the prevailing frameworks often exacerbate inequalities across and within regions. A closer examination of financial flows, instruments, and institutional practices reveals critical challenges that undermine the equitable and effective deployment of climate finance globally. One of the foremost challenges lies in the asymmetry of funding sources and their geographic distribution. In 2019, global climate finance stood at approximately US

${\$} $ Geographic disparities are further entrenched by the limited cross-border flow of climate finance. OECD data from 2018 showed that roughly 60% of climate-related commitments remained within donor countries, with a majority reinvested domestically. A similar trend was evident in 2019, when three-quarters of tracked global climate investments originated and remained within national borders. Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, and Latin America collectively received only 25% of these funds, underscoring a systemic bias that favors donor retention[174,175]. Notably, only 20.5% of climate-related development finance reached least developed countries (LDCs), and a mere 3% was allocated to small island developing states[177]. These statistics reflect an urgent need to overhaul disbursement mechanisms and ensure fairer financial flows aligned with vulnerability and adaptation needs.

A further complication arises from the composition of financial instruments used to deliver climate finance. Debt remains the dominant modality, accounting for 61% (US

${\$} $ Sectoral concentration is another structural challenge in global climate finance governance. Nearly half of the total climate funds mobilized in 2019 were directed toward energy and transportation. Renewable energy alone attracted 54% of mitigation finance, largely from private sources, while 31% was invested in low-carbon transport systems[180]. These sectors benefit from mature technologies, clear revenue streams, and scalable business models, which make them attractive to private investors. In contrast, agriculture, forestry, and land-use sectors which are critical for many developing economies receive far less funding due to higher perceived risks and diffuse returns. This sectoral bias not only limits mitigation co-benefits like carbon sequestration and biodiversity preservation but also neglects the livelihoods of populations heavily dependent on land-based systems. Global governance mechanisms face a legitimacy and coordination dilemma. As climate finance expands, decision-making remains fragmented, with divergent national interests, varying regulatory frameworks, and competing institutional mandates. Multilateralism, though essential for inclusive climate action, often struggles to deliver timely and equitable outcomes. The lack of binding commitments, insufficient representation of the Global South in financial governance bodies, and minimal transparency in climate fund disbursements further erode trust among stakeholders. While pragmatic multilateralism remains the most viable pathway in a fragmented world order, its effectiveness is limited without stronger coordination, capacity building, and institutional accountability. The global governance of climate finance is fraught with systemic imbalances in funding sources, geographic allocations, financial modalities, sectoral targeting, and institutional representation. These challenges must be addressed through reforms that enhance the accessibility, fairness, and effectiveness of climate finance flows ensuring that they align with both global mitigation goals and the localized adaptation needs of the most vulnerable communities. Table 4 summarizes the key challenges in global climate finance governance.

Table 4. Challenges in climate governance

Challenge area Key issues identified Implications Ref. Funding source imbalance Disproportionate reliance on public funding in developing countries; private finance concentrated in developed regions Limits equitable investment; risks marginalization through conditional private capital [178,179] Geographic disparities Majority of finance remains within donor countries; minimal flow to LDCs and SIDS Undermines global equity; vulnerable regions underfunded despite higher exposure to climate risks [180,181] Debt-dominated instruments 61% of finance delivered through debt (mostly non-concessional); grants only 6% Increases debt burden in low-income countries; limits developmental alignment [182,183] Adaptation vs mitigation gap 90% of finance goes to mitigation; only 7.4% to adaptation Fails to meet urgent local needs; adaptation underfunded despite importance for resilience [184,185] Sectoral concentration High funding for energy and transport; low investment in agriculture, forestry, land use Neglects rural livelihoods and land-based mitigation co-benefits [56,186] Governance fragmentation Fragmented decision-making; lack of Global South representation; weak transparency Reduces legitimacy and trust; impedes coordination and inclusive implementation [56,186] -

Climate resilience represents the capacity of communities to anticipate, absorb, adapt to, and recover from the adverse effects of climate change[56]. As global temperatures rise, with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) indicating a 1 °C increase above preindustrial levels, the frequency and severity of extreme weather events and sea-level rise have intensified. These changes demand targeted interventions to strengthen the resilience of both urban and rural communities[56,187]. Urban centers face distinct challenges due to rapid urbanization, infrastructure deficits, and heightened exposure to climate-related hazards. Overcrowding and informal settlements have strained housing systems, while aging infrastructure and inadequate public services exacerbate vulnerabilities. Strategic interventions such as inclusive urban planning, investments in resilient infrastructure, and climate-adaptive architecture are critical[56]. Additionally, marginalized populations disproportionately suffer from urban flooding and heatwaves, necessitating the deployment of green spaces, early warning systems, and equitable access to services[56,188].

In contrast, rural communities contend with limited access to healthcare, education, and communication networks[189,190]. The high dependency on climate-sensitive agriculture heightens their exposure to weather-related shocks. Building resilience in these areas requires diversified, climate-resilient livelihoods, expanded digital infrastructure, and sustainable agricultural practices[189,190]. Moreover, rural-to-urban migration drains vital human capital, necessitating policies that promote local entrepreneurship, agribusiness development, and community-based disaster preparedness frameworks[189].

Empowering communities through localized adaptation

-

Resilience-building must be grounded in community empowerment and knowledge dissemination. Enhancing climate literacy through participatory education, community dialogues, and awareness campaigns fosters informed decision-making and localized innovation[191,192]. Capacity-building initiatives are foundational. Equipping individuals with skills in natural resource governance, renewable energy deployment, and sustainable agriculture cultivates adaptive capabilities[193]. These efforts not only enhance livelihood security but also contribute to emissions reduction. Simultaneously, collaborative governance involving local actors, civil society, and municipal authorities ensures that indigenous knowledge and contextual insights are incorporated into adaptation planning. Such inclusivity improves the legitimacy and uptake of interventions[194].

Access to financial and technical resources remains a major bottleneck. Donors, NGOs, and governments must bridge funding gaps by channeling investments into community-driven projects and infrastructure[129]. Climate insurance programs can mitigate post-disaster recovery burdens and foster long-term resilience. Moreover, implementing locally tailored technologies such as solar microgrids, cool roofing, and bio-digesters enhances community adaptability while promoting environmental co-benefits[195]. Empirical examples underscore the efficacy of community-led models. In India, the Cool Roof Project has demonstrably reduced heat stress and energy consumption in low-income neighborhoods[195]. In the United States, Miami's climate insurance scheme offers protection to vulnerable households against sea-level rise and extreme weather[43]. Globally, the World Bank warns that without robust adaptation, climate-induced displacement could affect up to 143 million people by 2050[138]. Meanwhile, the Global Commission on Adaptation estimates that investing

${\$} $ ${\$} $ Scaling climate finance and technology deployment

-

To align with the Paris Agreement's goals of limiting global temperature rise to below 2 °C, greenhouse-gas emissions must decline by 25%–50% by 2030 relative to pre-2019 levels. Yet, IMF projections reveal a likely reduction of only 11% under current climate pledges, highlighting an urgent need to enhance ambition, expand investment, and implement transformative policies[196]. Meeting climate goals requires mobilizing trillions of dollars annually through 2050. However, the current global climate finance flows stand at approximately

${\$} $ ${\$} $ Simultaneously, strengthening public finance and investment management is imperative. Policymakers must be equipped to identify, appraise, and implement climate-resilient projects, requiring improvements in fiscal risk assessment and project pipeline development. The lack of standardized climate data, disclosure frameworks, and investment taxonomies hampers capital mobilization[199,200]. Investing in climate information systems and institutional capacity can overcome these barriers and enhance the bankability of climate projects. Innovative financial instruments can further facilitate private-sector participation. De-risking tools such as credit guarantees, blended finance structures, and insurance mechanisms can address challenges posed by high upfront costs, currency volatility, and illiquid markets in developing regions[139,197]. Flexibility in financial models including programmatic approaches and regional strategies can broaden participation and improve alignment with national priorities[139].

Nature-based solutions (NbS) offer a promising avenue for integrating climate action with biodiversity conservation and social equity. Supporting the development of robust NbS markets, including biodiversity credits and sustainable land-use finance, requires both regulatory support and market infrastructure. Ensuring the participation of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in NbS design and implementation will strengthen legitimacy and effectiveness[201]. Governments should also phase out environmentally harmful subsidies and redirect public expenditures toward nature-positive outcomes[200]. Development agencies, both bilateral and multilateral, must evaluate their operational effectiveness and harmonize their strategies with broader climate finance architectures[199]. Coordinated governance is vital. A dedicated working group under the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation (GPEDC) could institutionalize periodic reviews of climate finance impact and foster knowledge exchange between climate and development finance domains[198]. The emerging post-2025 climate finance framework must incorporate lessons from current practice and structure its targets to ensure accessible, efficient, and equitable funding flows[39]. Ultimately, scaling climate finance and technology deployment depends not only on capital mobilization but also on institutional reform, inclusive planning, and global solidarity. Only through synergistic public-private partnerships and community-centered action can the dual goals of climate resilience and sustainable development be achieved[139,197]. Table 5 summarizes key scaling interventions needed for climate financing and related technologies.

Table 5. Strengthening resilience and scaling climate finance

Section Theme Key points Ref. Enhancing resilience in vulnerable regions Urban resilience • Rapid urbanization and aging infrastructure increase climate risks

• Requires inclusive planning, resilient infrastructure, and adaptive architecture

• Focus on green spaces, early warning systems, and equitable services[202,203] Rural resilience • Limited access to basic services and high dependence on agriculture

• Need for diversified livelihoods, digital infrastructure, sustainable farming

• Mitigate migration by promoting local entrepreneurship and disaster preparedness[204,205] Empowering communities through localized adaptation Community empowerment • Enhance climate literacy through education, dialogues, and awareness

• Capacity-building in resource governance, energy, and agriculture

• Collaborative governance ensures local knowledge integration[206,207] Financial access and local tech • Bridge funding gaps via donor/NGO/government support

• Promote climate insurance and localized technologies (e.g., solar microgrids, cool roofs)

• Example: India's Cool Roof Project and Miami's insurance scheme[129,195] Scalable models • Mahila Housing Trust shows success in women-led, grassroots climate planning

• Emphasis on local ownership and community-led resilience[39,198] Scaling climate finance and technology deployment Financing needs and gaps • ${\$} $630 B/year falls short of the needed trillions; developing nations underserved

• Developed nations must exceed ${\$} $100 B climate finance pledge[199,200] Policy and investment reform • Align financial incentives with green outcomes via reforms, pricing, and subsidies

• Strengthen public finance systems, standardize data and disclosure frameworks[197] Private sector and innovation • Use de-risking tools: guarantees, blended finance, insurance

• Flexible financial models improve inclusivity and national alignment[203] Nature-based solutions (NbS) • Integrate climate goals with biodiversity and equity

• Support NbS markets; ensure Indigenous and local participation[201] Governance and coordination • Phase out harmful subsidies; redirect funds to nature-positive outcomes

• Use GPEDC to institutionalize climate finance reviews

• Future frameworks must ensure accessibility, equity, and coordination[198−200] -

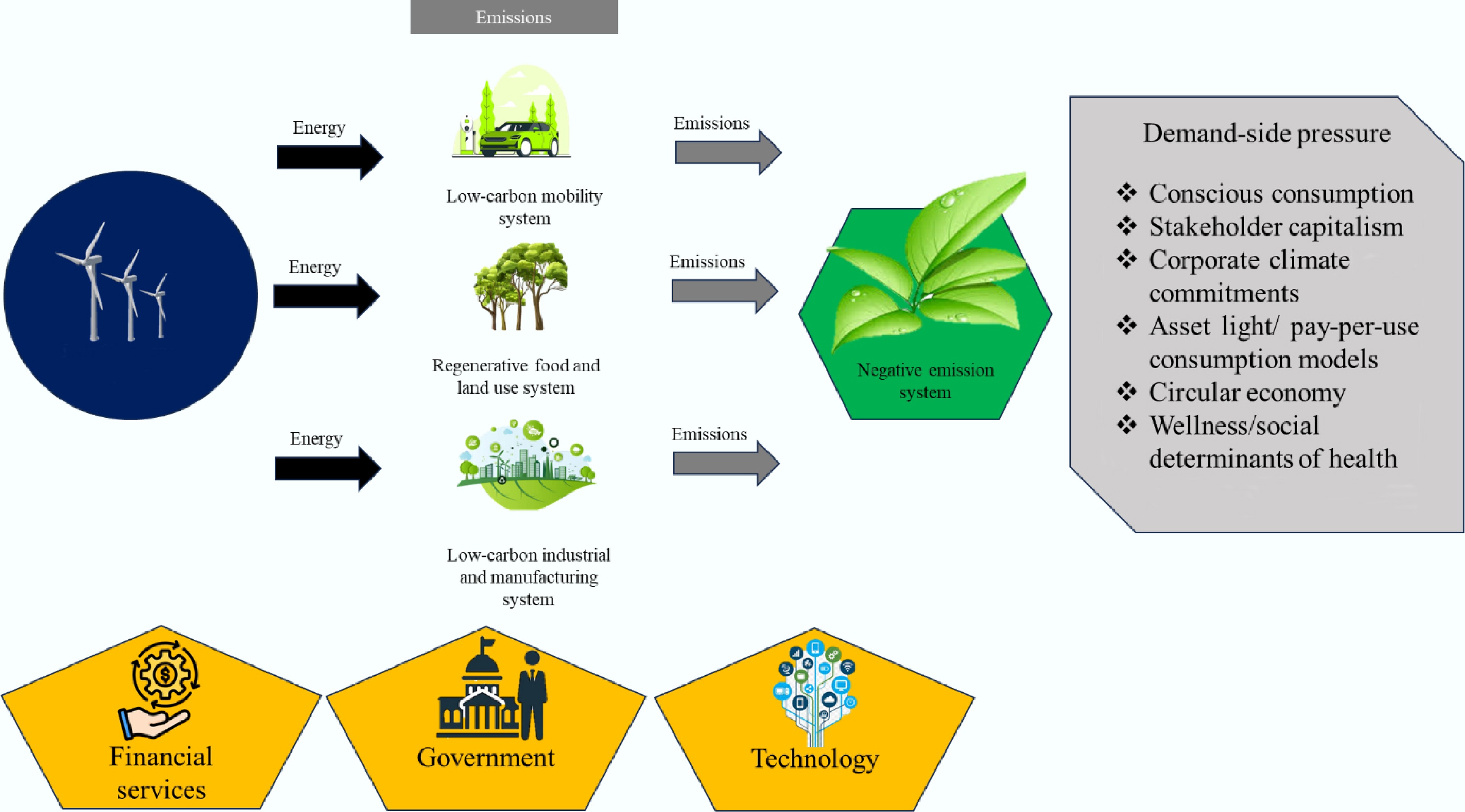

Achieving a sustainable, low-carbon future hinges on a fundamental reconfiguration of production, consumption, and governance systems. Since metropolitan areas consume the lion's share of global energy, materials, and goods, the transition to low-carbon pathways necessitates transformative changes in urban design, transport systems, energy sourcing, and land-use practices. In this context, the integration of low-carbon energy systems, negative emission technologies, and demand-side pressures plays a pivotal role in shaping climate-compatible development trajectories. Figure 4 illustrates the interconnection between low-carbon energy infrastructure and negative emission systems, as well as the behavioral and structural transitions driven by conscious consumption, stakeholder capitalism, and circular economy principles. The transition is also catalyzed by the synergistic role of financial services, technology, and government interventions. This systemic transformation involves several key mechanisms. Conservation and efficiency improvements are necessary to reduce energy intensity across industries, buildings, and transportation. Decarbonization of the energy grid, including a gradual phasing out of fossil fuels and a shift toward renewable energy, is essential. Simultaneously, emission sequestration must be prioritized by enhancing natural carbon sinks such as forests, soils, and agricultural lands while minimizing waste generation and methane emissions from agriculture and urban systems.

Digital technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT), blockchain, and cloud computing are increasingly central to this transition. They enable intelligent monitoring, predictive maintenance, and optimization of low-carbon operations. As industries integrate these solutions, decarbonization becomes not only feasible but economically competitive. Moreover, the demand-side transformation fueled by consumer preference for sustainability has begun reshaping business models. Firms adopting pay-per-use, asset-light, and wellness-driven models are leading the new climate economy, generating demand for cleaner alternatives and high-quality carbon offsets. To operationalize these aspirations, sector-specific pathways must be devised and implemented. The table below (Table 6) presents a detailed taxonomy of transition actions required across key economic sectors, identifying technological, infrastructural, and behavioral levers of change.

Table 6. Sectoral roadmap toward a low-carbon economy

Sector Required transitions Decarbonization strategies Energy supply Upgrade grid systems to integrate demand-side and renewable resources; eliminate coal and gas from the electricity mix; enhance power generation for fuel switching; restructure utility markets to favor decentralized energy. Build resilient transmission infrastructure; enforce policies for renewable energy scale-up; apply grid-balancing algorithms; incentivize solar, wind, and hybrid systems through regulatory frameworks. Transportation Improve fuel efficiency and engine performance; promote electrification and fuel-cell vehicles; decarbonize fuels; reduce vehicle-miles travelled. Integrate e-mobility infrastructure; develop green logistics networks; implement mileage-based taxation; utilize low-carbon fuels in aviation and shipping sectors. Residential and commercial Increase energy efficiency in end-use applications; promote electrification of heating and water systems; improve thermal insulation and appliance efficiency. Integrate smart building systems; deploy rooftop solar; incentivize net-zero energy buildings; adopt performance-based energy codes. Industry Enhance process energy efficiency; recover and reuse waste heat; transition to low-carbon fuels and electrified manufacturing processes. Promote industrial symbiosis; deploy carbon capture and utilization (CCU) in heavy industry; finance energy-as-a-service models for small enterprises. Agriculture and waste Reduce methane from livestock and landfills; optimize nutrient management; enhance carbon sequestration; develop anaerobic digestion systems. Establish climate-smart agriculture programs; finance bio-digesters and composting units; support regenerative farming practices through subsidies and carbon markets. Land use and forestry Preserve carbon sinks; limit deforestation; expand afforestation and reforestation; manage urban natural habitats for carbon storage. Design REDD+ compliant land policies; integrate forestry in national climate plans; support community-based forest governance; incentivize agroforestry and wetland restoration. As shown in Table 6, sector-specific pathways must operate in tandem with cross-sectoral enablers to generate cumulative mitigation impacts. For instance, the energy and transport sectors are interdependent, as electrification of mobility requires a clean power grid. Similarly, carbon sequestration efforts in agriculture must be coordinated with industrial waste reuse and land conservation. To further accelerate the transition, multi-level governance and cross-sectoral cooperation are essential. This includes strengthening institutional capacity, restructuring fiscal policies, and leveraging digital tools for transparency and accountability. Financing mechanisms must shift toward de-risking investments in low-carbon assets and supporting market creation for emerging technologies, especially in developing economies. Moreover, consumer behavior is rapidly evolving. As illustrated in Fig. 4, demand-side transformations are now significant drivers of decarbonization. Ethical consumption, environmental accountability of businesses, and integration of social well-being into sustainability metrics are reconfiguring market dynamics. When combined with robust technological ecosystems and supportive public policies, these trends can yield exponential progress toward climate targets. The pursuit of a low-carbon, climate-resilient future is not merely a technological shift, it is a structural realignment of the economy, society, and environment. It demands a strategic convergence of renewable energy systems, circular consumption models, and strong institutional frameworks. The interplay of supply-side transformations, enabled through innovation and finance, and demand-side pressures rooted in values, awareness, and inclusivity can collectively forge a sustainable pathway toward global net-zero ambitions.

-