-

Pig production has emerged as a significant industry, producing sufficient animal products to ensure the food security of the global population, particularly the Chinese population[1]. The scarcity of corn and soybeans due to the competition between humans and animals, the primary feedstock materials for pigs, has prompted researchers to explore different alternatives to feedstock materials[2]. Among these alternatives, local resources have been prioritized as potential substitutes for corn and soybean meal in pig farming[3,4]. Among these local resources, palm kernel cake (PKC) has garnered particular attention from the pig feed industry[5].

PKC, a byproduct of palm oil extraction, is currently produced in tropical countries, particularly Indonesia and Malaysia, in quantities estimated to be 58.8 million tons worldwide and has a good amount of crude protein (14%−18%), crude fiber (12%−20%), ether extract (3%−9%), and various minerals, which manifest an interest in pig feeding[5−9]. Its high protein content makes it a potential alternative to corn and soybean since it ranks as the fifth largest protein meal feed after soybean meal, rapeseed meal, sunflower meal, and cottonseed meal[9−11]. The high fiber content of PKC renders it less useful in the pig feed industry. Research has been conducted to reduce this high fiber content, to make it easily digestible by animals, particularly pigs[10]. Among the different techniques proposed, solid-state fermentation employing different cellulolytic bacteria has been identified as beneficial[12]. Cellulolytic bacteria significantly enhance the nutritional value of PKC through the fermentation process by degrading its high fiber content[13].

Lactobacillus plantarum and Bacillus natto are noteworthy among beneficial bacteria due to their applications in the feed industry. It has been demonstrated that supplementing pigs' diets with Lactobacillus plantarum can enhance their body weight, immune responses, intestinal morphology, and digestive enzyme activity[11]. Bacillus natto improves the structure and diversity of intestinal microflora, increases the diversity and richness of immunological function, and enhances growth performance in pigs[14].

This experiment utilized a mixture of Lactobacillus plantarum LY19 (license: CCTCC M 2022043 LY19), Bacillus natto NDI (license: CCTCC M 2022042 ND1), both of which were isolated from biomass and preserved in our laboratory, and hydrolysis enzymes. An in vitro experiment in our laboratory and our previous study on broiler chickens showed that a mix of Lactobacillus plantarum LY19, Bacillus natto NDI, combined with hydrolysis enzymes, greatly decreased the amount of fiber in PKC content from 15.57% to 7.60% of DM basis[15]. This made the nutrients easier for the chickens to digest, increased the digestive enzyme activities, and helped the chickens' digestive organs to grow. This research aimed to incorporate both fermented and unfermented PKC into pigs' diets by proposing a feeding formula that can be a substitute for corn and soybeans in their nutrition. Throughout this study, the effects of incorporating unfermented and fermented PKC into pigs' diets on growth performance, biochemical indices, nutrient digestibility, intestinal morphology, digestive enzyme activity, tight junction, short-chain fatty acid, and colonic microbiota composition were evaluated to ensure that the different formulations are safe for pigs.

-

The PKC fermentation process used Bacillus natto NDI (license: CCTCC M 2022042 ND1) and Lactobacillus plantarum LY19 (license: CCTCC M 2022043 LY19). Before PKC fermentation, 1% of Bacillus natto NDI was added to the resultant obtained to activate it after 1% of Lactobacillus plantarum LY19 had been inoculated. A mixture of Lactobacillus plantarum LY19 and Bacillus natto NDI was produced using a 1:2 volume ratio (v/v). The same water was used to dissolve a combination of mannanase (45 U/g), cellulase (160 U/g), and acid protease (250 U/g). These three enzymes were selected for their ability to break down the crude fiber content in the PKC and their concentrations was chosen according to our previous study[15]. The final solution was then mixed with a previously made blend of Bacillus natto NDI and Lactobacillus plantarum LY19. These two bacteria accounted for 7% of the total weight of the PKC in the solution volume. The PKC and the fully prepared solution were mixed at a ratio of 5:4 (w/v). This solution was thoroughly mixed with PKC before being put inside fermentation bags supplied by Wenzhou Wangting Packaging Co., Ltd (40 cm × 23 cm, and 2 kg in each bag). The fermentation procedure took place in an incubator at 37 °C and pH 4.8 for 48 h. Supplementary Table S1 shows the different nutritional values of PKC before and after the fermentation process.

Animal housing and experimental design

-

A total of 24 finishing pigs (5-month-old fattening male castrated Duroc × Landrace × Large White pigs) with no significant variation (103.92 ± 1.58 kg) were assigned to three groups at random, including the unfermented palm kernel cake group (PKC group), the fermented palm kernel cake group (FPKC group), and the control group (CON). The initial body weight of these pigs did not differ significantly, and each group consisted of eight replications, each containing a single finishing pig. The finishing pigs in the CON group received a basal diet, while the PKC group substituted 30% of the basal diet with unfermented PKC, and the FPKC group replaced 30% of the basal diet with fermented PKC. All pigs were fed in individual pens (2 m × 2 m) with free access to feed (07:30, 12:00, and 17:30, every day). and water for 30 d. After our feed formulation, the cost of the CON group was higher than that of the PKC or the FPKC groups. As indicated in Table 1, the nutritional level and content of the various formulae were established in accordance with the nutrient needs of pigs (NRC, 2012)[16].

Table 1. Chemical composition and nutrient level of different formulae (% of dry matter basis).

Item Diets CON1 PKC2 FPKC3 Ingredients Corn 61.80 40.00 39.80 Soybean meal 14.00 11.00 11.70 Corn gluten meal 3.00 0.00 0.50 Soybean oil 3.20 3.00 3.00 Corn starch 13.00 11.00 10.00 Fish meal 1.00 1.00 1.00 Palm kernel cake 0.00 30.00 0.00 Fermented palm kernel cake 0.00 0.00 30.00 Premix4 4.00 4.00 4.00 Total 100.00 100.00 100.00 Nutrient levels5 Metabolic energy (MJ/kg) 13.91 13.93 13.96 Crude protein 13.20 13.30 13.78 Calcium 0.50 0.51 0.50 Available phosphorus 0.25 0.26 0.25 Lysine 0.62 0.61 0.63 Methionine 0.27 0.25 0.26 Methionine + cysteine 0.53 0.49 0.50 Crude ash 4.97 5.84 5.95 Crude fiber 2.19 5.26 4.48 Crude fat 4.47 5.03 5.38 1 CON: control group (basal diet), 2 PKC: unfermented palm kernel cake group (basal diet substituted with 30% of unfermented palm kernel cake diet), 3 FPKC: fermented palm kernel cake group (basal diet substituted with 30% of fermented palm kernel cake diet). 4 The premix provided the following per kg of diet: vitamin A: 100,000 IU, vitamin D3: 30000 IU, vitamin E: 240 IU, vitamin B2: 78 mg, pantothenic acid: 200 mg, nicotinamide: 300 mg, Fe (from ferrous sulfate): 2,000 mg; Cu (from copper sulfate): 100 mg, Mn (from manganese sulfate): 500 mg, Zn (from zinc sulfate): 1,000 mg, I (from calcium iodate): 10 mg, Se (from sodium selenite): 5.0 mg. 5 ME values were calculated from data provided by Feed Database in China (2020). Sample collection and different parameter detection

Growth performance

-

During the growing phase, the body weight of the finishing pigs was determined on the first day and the last day of this study. Pigs were fasted for 12 h (to ensure drinking water) before taking their body weight measurements. The feed intake was measured daily as the quantity of feed given to the pigs minus the feed not consumed. After calculation of the daily feed intake, initial and final pigs' body weight, the average daily weight gain (ADG), average daily feed intake (ADFI), and feed conversion ratio (FCR) were calculated using the following formulas: ADFI = (Total feed intake per pig (g)) / (Number of the experimental days); FCR = (Total feed consumed in the statistical period (g)) / (Total body weight gain in the experimental period (g)); and ADG = (Body weight gain per pig (g)) / (Number of the experimental days).

Blood sample collection and serum biochemical variable determination

-

To collect samples, six pigs per treatment were killed on the final day of the experiment. The 10 mL blood sample obtained from each pig's anterior vein was transferred into 10 mL vacuum-sterilized blood collection tubes. Clear sera were extracted from the collected blood samples by centrifuging them for 10 min at 4 °C and 3,000 × g. These were then stored at −80 °C for additional examination. An automatic biochemical analyzer (Chemray 800, Shenzhen Rayto Life Science Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) was then used to measure the albumin (ALB), globulin (G), total protein (TP), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), glucose (Glu), triglyceride (TG), alanine aminotransaminase (ALT), and total cholesterol (TC).

Apparent nutrient digestibility analysis

-

In the last week of the experiment, a plastic tray was set underneath the pig's cage for collecting excrement. Over the next three days, the amount of feed consumed and the excrement from the feces were measured. For three days, 150 g of homogenized excreta samples were taken once a day from each cage. Each sample was immediately placed in a freezer at −20 °C after being treated with 10 mL of a 10% concentrated hydrochloric acid solution. The excrement samples collected over three days from the same cage were combined and blended until homogenized. The excreta samples were dried in an oven at 65 °C for 48 h and subsequently allowed to settle to air condition for 30 min before being quantified. Following that, samples of feed and excrement were pulverized through a 0.45-mm screen. The following parameters were then measured: gross energy (IKA Calorimeter System C 5010; IKA Works, Staufen, Germany); crude fiber (GB/T6433-2006 method); crude protein (method 988.05, AOAC); dry matter (method 934.01, AOAC); and crude ash (method 942.05, AOAC). The following formula was used to calculate the apparent digestibility level:

Apparent nutrient digestibility = 100 (1− [(% AIA feed / % AIA fecal) × (% fecal nutrient / % feed nutrient)]), where, AIA is acid-insoluble ash content[17,18].

Digestive enzyme activity analysis

-

A 0.9% ice-cold NaCl solution and 0.1 g of jejunal digesta sample were combined until they were homogenized. The supernatants were then extracted from the homogenates by centrifuging them for 10 min at 2,500 rpm and 4 °C. The activities of trypsin, chymotrypsin, α-amylase, maltase, sucrase, and lipase were then evaluated using commercial assay kits from Nanjing Jiancheng Bio-Engineering Institute (Nanjing, China). In accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, the protein concentration was also determined.

Intestinal morphology

-

Six healthy pigs per treatment (with no discernible variation in body weight) were chosen at random and sacrified using the routine method at the end of the experiment. For histological analysis, 2 cm samples from the middle of the jejunum were taken and immediately preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h. Each pig's jejunum was cut into pieces, and samples were taken from the middle of the jejunum. Before being embedded in paraffin wax and kept in storage, the tissues were manually dehydrated and fixed in a 10% neutral formalin solution. After being cut into 5 μm slices and stained with hematoxylin and eosin, the preserved tissues were captured on camera using a digital microscope (Olympus BX5; Olympus Optical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Histological indices were computed using Image Pro Plus software (version 6.0, Media Cybernetics, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA). Eight distinct villi or crypt depths were measured for each slice.

Quantitative real-time PCR for tight junction

-

The SteadyPure RNA Kit (AG21024, Accurate, Hunan, China) was used to extract total RNA from the jejunal mucosa. A Nano-Drop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, USA) was then used to measure the RNA's concentration and purity. Using enzyme-free water, all jejunal mucosa samples were maintained at a consistent RNA content of 500 ng/mL. The levels of mRNA gene expression was then assessed using the Thermo-Fisher Scientific Power SYBRR Green PCR MasterMix and BioRad's CFX384 multiplex real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR equipment (Q221-1, Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Primer Premier 6.0 software was used to create the primer sequences, which were then manufactured by Bioengineering Biotechnology, Shanghai, Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). After that, the housekeeping gene (β-actin) primers and tight junction proteins like Claudin-1, Occludin, and Zonula Occludens-1 (ZO-1) were examined. Primers for the genes selected for qPCR expression verification and relative expression levels were ascertained using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ technique. Table 2 shows the primer sequences for the chosen genes.

Table 2. Primer sequences for RT-PCR.

Gene NCBI gene ID Sequence Product length (bp) β-actin XM_021086047.1 F: AACTACCTTCAACTCCATCAT R: GATCTCCTTCTGCATCCTGT 124 CLAUDIN1 NM_001244539.1 F: CTATGACCCCATGACCCCAG R: GGCCTTGGTGTTGGGTAAGA 150 OCCLUDIN NM_001163647.2 F: CAGCCTCATTACAGCAGCAGTGG R: TCGCCGCCCGTCGTGTAG 128 ZO-1 XM_021098856.1 F: CCAGGGAGAGAAGTGCCAGTAGG R: TTTGGTGGGTTTGGTGGGTTGAC 92 CLAUDIN1: tight junction protein-1, OCCLUDIN: closed protein, ZO-1: zonula occludens1. 16S rRNA sequencing analysis of microbiota in colon samples

-

Using cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB), genomic DNA was isolated from finishing pig colonic digesta samples. A 1% agarose gel was used to evaluate the quality of the DNA extraction process, and a UV spectrophotometer was used to measure the amount of DNA. Primers 515F and 907R amplified the 16S rRNA gene's V4−V5 region. The PCR products were purified using magnetic beads and quantified by enzymatic labeling after being identified by agarose gel electrophoresis at a 2% concentration. Following a thorough mixing and homogenization of the samples based on the concentration of the PCR products, the target band products were obtained by identifying the PCR products using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Libraries were constructed using the TruSeq® DNApcr Sample Free Preparation Kit (Illumina, USA). LQubit (Thermo Sciences) and Q-PCR quantified the libraries, while NovaSeq6000 (Kapa Biosciences, Woburn, MA, USA) sequenced them. The singleton ASV was eliminated for alpha and beta diversity analyses based on the collected ASV (feature) feature sequence and abundance table.

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) analysis in colon samples

-

Two milliliters of digesta were extracted from the colon and transferred into a cryopreservation tube following the killing of the pigs (n = 6/treatment) and the removal of the intestinal section components. A microcentrifuge (Microfuge 22R, Beckman Coulter, CA, USA) was used to centrifuge 0.5 g of digesta samples for 10 min at 12,000 rpm after homogenizing them with 1,000 μl of deionized water (ddH2O). The resulting supernatants were mixed with 100 μl of crotonic acid, which was used as the internal standard for the short-chain fatty acid test. With a capillary column (Agilent Technologies, HP-INNOWax, 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, CA, USA), an injector/detector temperature of 180 °C, and a column temperature of 130 °C, the presence of short-chain fatty acids in the contents of the colon sample was evaluated using gas chromatography (GC2010 Plus, Shimadzu, Japan). A gas flow rate of 30 mL/min was set.

Statistical analysis

-

This experiment used a completely randomized design, and the statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS 25 software. Using a polynomial linear model, a one-way ANOVA was performed on all the data (for each parameter). The major claims among the treatments were compared using Tukey's multiple-range test. The data appear in tables as means with standard error of the means (SEM), and there are significant differences (p < 0.05) between the means that do not share common superscript letters (a, b, c, or a, b) within a row (Tables 3−8).

-

Over the 30 d of this experiment, the results presented in Table 3 showed that there were no discernible variations in terms of final body weight (FBW), ADG, and ADFI across the PKC and FPKC or when comparing each treatment to the CON group (p > 0.05). However, the FCR was significantly higher in the PKC group compared to the CON or FPKC groups (p < 0.05), but no noteworthy variation was found across the CON and FPKC groups (p > 0.05).

Table 3. Effect of incorporating unfermented or fermented PKC into finishing pigs' diet on their growth performance (n = 6/treatment).

Items CON1 PKC2 FPKC3 SEM p-value IBW (kg) 104.08 104.17 103.75 0.56 0.96 FBW (kg) 131.92 129.42 130.75 1.04 0.64 ADFI (g/d) 3,098.94 3,156.66 3,118.22 54.38 0.92 ADG (g/d) 922.23 841.65 900.00 24.80 0.42 FCR 3.38b 3.77a 3.48b 0.07 0.03 1 CON: control group (basal diet), 2 PKC: unfermented palm kernel cake group (contains a 30% unfermented palm kernel cake diet), SEM: standard error of means, 3 FPKC: fermented palm kernel cake group (contains a 30% fermented palm kernel cake diet), SEM: standard error of means. a, b Means in the same row with different superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05). IBW: initial body weight, FBW: final body weight, ADFI: average daily feed intake, ADG: average daily gain, FCR: feed conversion ratio. Apparent nutrient digestibility

-

Table 4 indicates that the CON group had considerably higher apparent digestibility of dry matter, total energy, crude protein, and crude fiber compared to the PKC or FPKC groups (p < 0.05). While the digestibility of dry matter and total energy was lower in the PKC group than in the FPKC, there was no discernible difference in the apparent digestibility of crude protein and crude fiber across the two groups (p > 0.05). Crude ash digestibility did not differ substantially across the PKC and FPKC groups, but it was lower in the PKC group than in the CON group.

Table 4. Effect of incorporating unfermented or fermented PKC into finishing pigs' diet on apparent nutrient digestibility (n = 6/treatment).

Items CON1 PKC2 FPKC3 SEM p-value Dry matter (%) 87.50a 76.69c 80.44b 1.17 < 0.01 Total energy (%) 86.84a 77.38c 80.66b 1.05 <0.01 Crude protein (%) 83.95a 64.91b 69.88b 2.17 < 0.01 Crude fat (%) 88.42 85.25 85.49 0.70 0.12 Crude fiber (%) 42.09a 30.60b 35.25b 1.51 < 0.01 Crude ash (%) 45.38a 31.77b 39.75ab 2.11 0.02 1 CON: control group (basal diet), 2 PKC: unfermented palm kernel cake group (contains a 30% unfermented palm kernel cake diet), 3 FPKC: fermented palm kernel cake group (contains a 30% fermented palm kernel cake diet), SEM: standard error of means. a, b, c Means in the same row with different superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05). Serum biochemical variables

-

Table 5 shows that while there were no substantial variations between the PKC and FPKC groups (p > 0.05), the TP and GLB concentrations in the PKC group were substantially lower than those in the CON group (p < 0.05). The ALB/GLB ratio did not change between the CON and FPKC groups, but it was higher in the PKC group than in either the CON or FPKC groups. The FPKC group's TC concentration was substantially lower than the CON group's (p < 0.05), while the FPKC group's TG concentration was substantially lower than the PKC group's (p < 0.05). There was no noteworthy variation in the TC and TG concentrations between the CON and PKC groups (p > 0.05). The FPKC group had a considerably greater GLU concentration than the CON and PKC groups (p < 0.05), although the PKC and CON groups did not vary significantly (p > 0.05). ALB, ALT, AST, and the AST/ALT ratio, however, did not differ significantly (p > 0.05).

Table 5. Effect of incorporating unfermented or fermented PKC into finishing pigs' diet on serum biochemical variables (n = 6/treatment).

Items CON1 PKC2 FPKC3 SEM p-value TP (g/L) 81.85a 72.68b 78.00ab 1.57 0.05 ALB (g/L) 39.56 38.23 38.68 0.53 0.62 GLB (g/L) 42.31a 34.45b 39.32ab 1.18 0.01 ALB/GLB 0.94b 1.11a 0.99b 0.02 <0.01 ALT (U/L) 52.84 57.77 54.22 1.40 0.35 AST (U/L) 62.71 64.77 65.04 2.66 0.93 AST/ALT 1.21 1.12 1.22 0.06 0.81 TG (mmol/L) 0.90ab 1.08a 0.75b 0.06 0.04 TC (mmol/L) 3.58a 3.13ab 2.75b 0.13 0.02 GLU (mmol/L) 2.38b 2.94b 3.89a 0.19 < 0.01 1 CON: control group (basal diet), 2 PKC: unfermented palm kernel cake group (contains a 30% unfermented palm kernel cake diet), 3 FPKC: fermented palm kernel cake group (contains a 30% fermented palm kernel cake diet), SEM: standard error of means, TP: total protein, ALB: albumin, GLB: globulin, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, ALT: alanine aminotransaminase, GLU: glucose, TG: triglyceride, TC: total cholesterol. a, b Means in the same row with different superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05). Intestinal morphology and tight junction

-

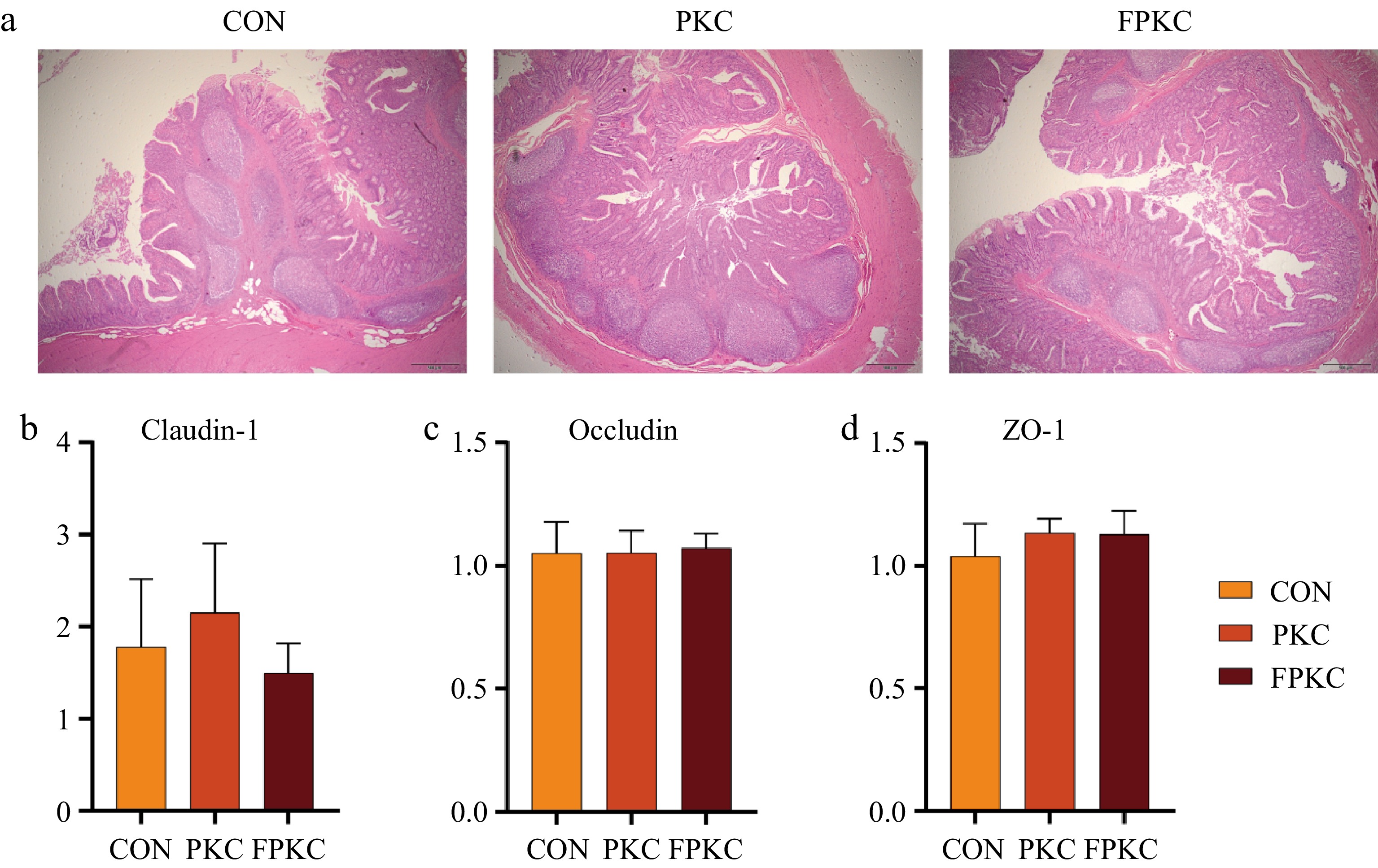

As shown in Fig. 1a, the jejunal villi showed some shedding and damage in all three groups. Table 6 demonstrated that the villus height in the PKC group was significantly lower than that in the CON group (p < 0.05), but no noteworthy variation was observed across the CON and FPKC groups (p > 0.05). The VCR in the CON and FPKC groups was considerably higher than that in the PKC group (p < 0.05), while there was no variation found across the CON and FPKC groups (p > 0.05). As illustrated by Figure 1b−d, the gene expression of ZO-1, OCCLUDIN, and CLAUDIN-1 did not differ among the PKC, FPKC, and CON groups (p > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Effect of incorporating unfermented or fermented palm kernel cake on the jejunum morphology and tight junction protein of finishing pigs. (a) H&E staining of the jejunum tissues. (b)−(d) Gene expression of tight junction protein (claudin-1, occludin, ZO-1).

Table 6. Effect of incorporating unfermented or fermented PKC into finishing pigs' diet on jejunal morphology (n = 6/treatment).

Items CON1 PKC2 FPKC3 SEM p-value Villus height (μm) 557.08a 473.81b 519.86ab 15.19 0.02 Crypt depth (μm) 366.15 367.84 356.48 10.08 0.90 VCR 1.52a 1.29b 1.46a 0.03 < 0.01 1 CON: control group (basal diet), 2 PKC: unfermented palm kernel cake group (contains a 30% unfermented palm kernel cake diet), 3 FPKC: fermented palm kernel cake group (contains a 30% fermented palm kernel cake diet), SEM: standard error of means, VCR: villi/crypt ratio. a, b Means in the same row with different superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05). Digestive enzyme activity

-

Table 7 demonstrates that the α-amylase, sucrase, and trypsin activities were lower in the PKC group than in the CON group (p < 0.05), but there was not a substantial variation across the CON and FPKC groups (p > 0.05). Chymotrypsin activity did not differ between the CON and FPKC groups; however, it was lower in the PKC group than in the CON or FPKC groups (p < 0.05). Lipase activity did not differ between the PKC and FPKC groups; however, it was considerably higher in the PKC and FPKC groups than in the CON group (p < 0.05). Maltase activity did not, however, change significantly between the regimens (p > 0.05).

Table 7. Effect of incorporating unfermented or fermented PKC into finishing pigs' diet on digestive enzyme activity (n = 6/treatment).

Items CON1 PKC2 FPKC3 SEM p-value α-amylase (U/gprot) 164.76a 131.40b 137.07ab 5.84 0.03 Maltase (U/mgprot) 90.00 86.89 80.24 2.26 0.20 Sucrase (U/mgprot) 216.43a 175.45b 194.46ab 6.53 0.03 Trypsin (U/mgprot) 362.61a 290.75b 313.02ab 10.53 < 0.01 Chymotrypsin (U/mgprot) 4.72a 3.44b 5.11a 0.25 < 0.01 Lipase (U/mgprot) 54.29b 69.77a 74.86a 2.76 < 0.01 1 CON: control group (basal diet), 2 PKC: unfermented palm kernel cake group (contains a 30% unfermented palm kernel cake diet), 3 FPKC: fermented palm kernel cake group (contains a 30% fermented palm kernel cake diet), SEM: standard error of means. a, b Means in the same row with different superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05). Colonic microbiota diversity and composition

-

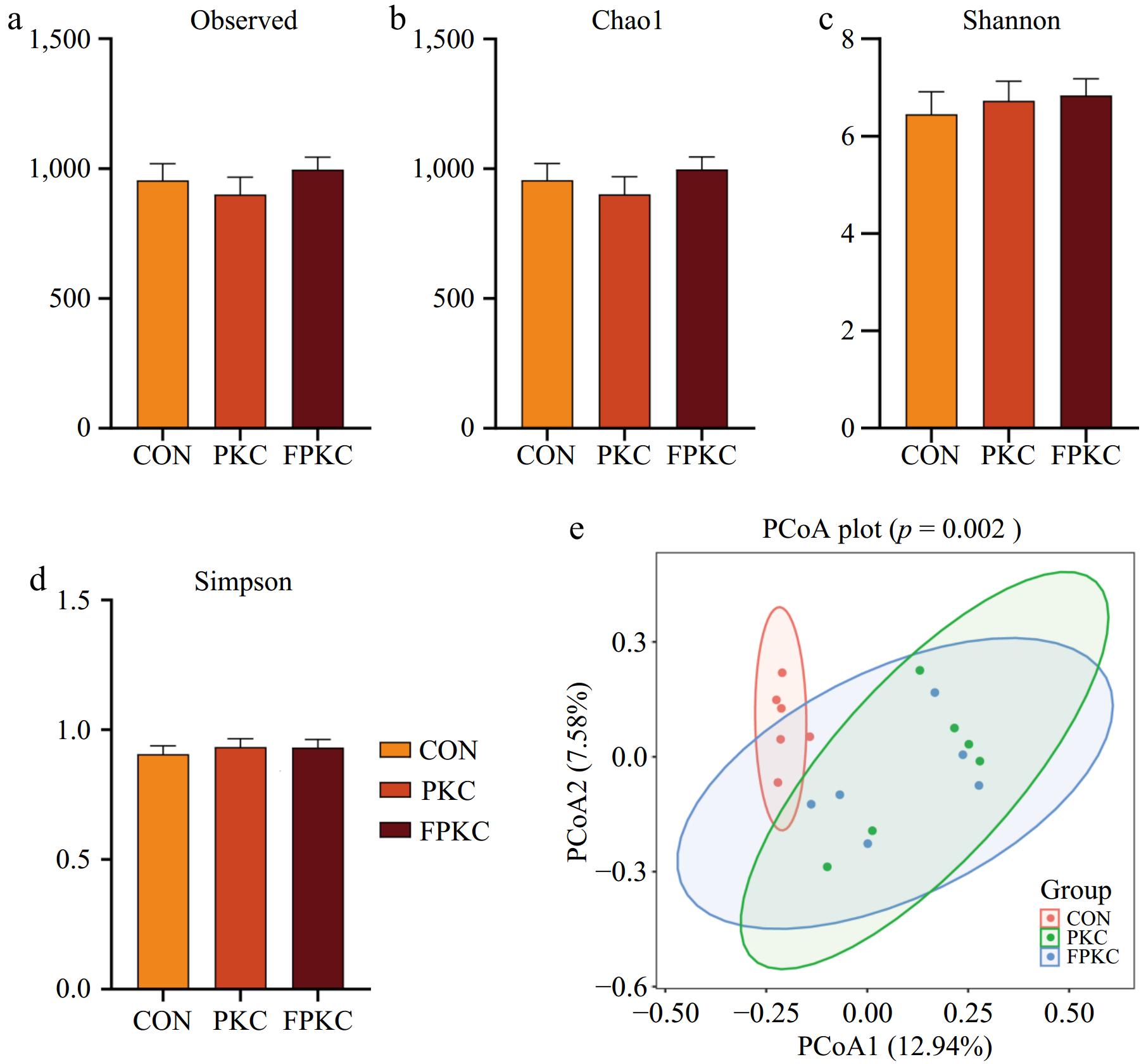

Figure 2a−d shows that there were no substantial variations among the CON, PKC, and FPKC groups in the α-diversity index, which includes the Shannon, Simpson, Ace, and Chao indices. Figure 2e shows that the CON group's β-diversity tended to be much different from that of the PKC and FPKC groups.

Figure 2.

Effect of incorporating unfermented or fermented palm kernel cake into finishing pigs' diets on colonic microbiota diversity (n = 6/treatment). (a)−(d) Alpha diversity index analysis of colon bacterial diversity and richness. (e) Beta diversity analysis of colon microbial community through principal coordinate analysis (PCoA).

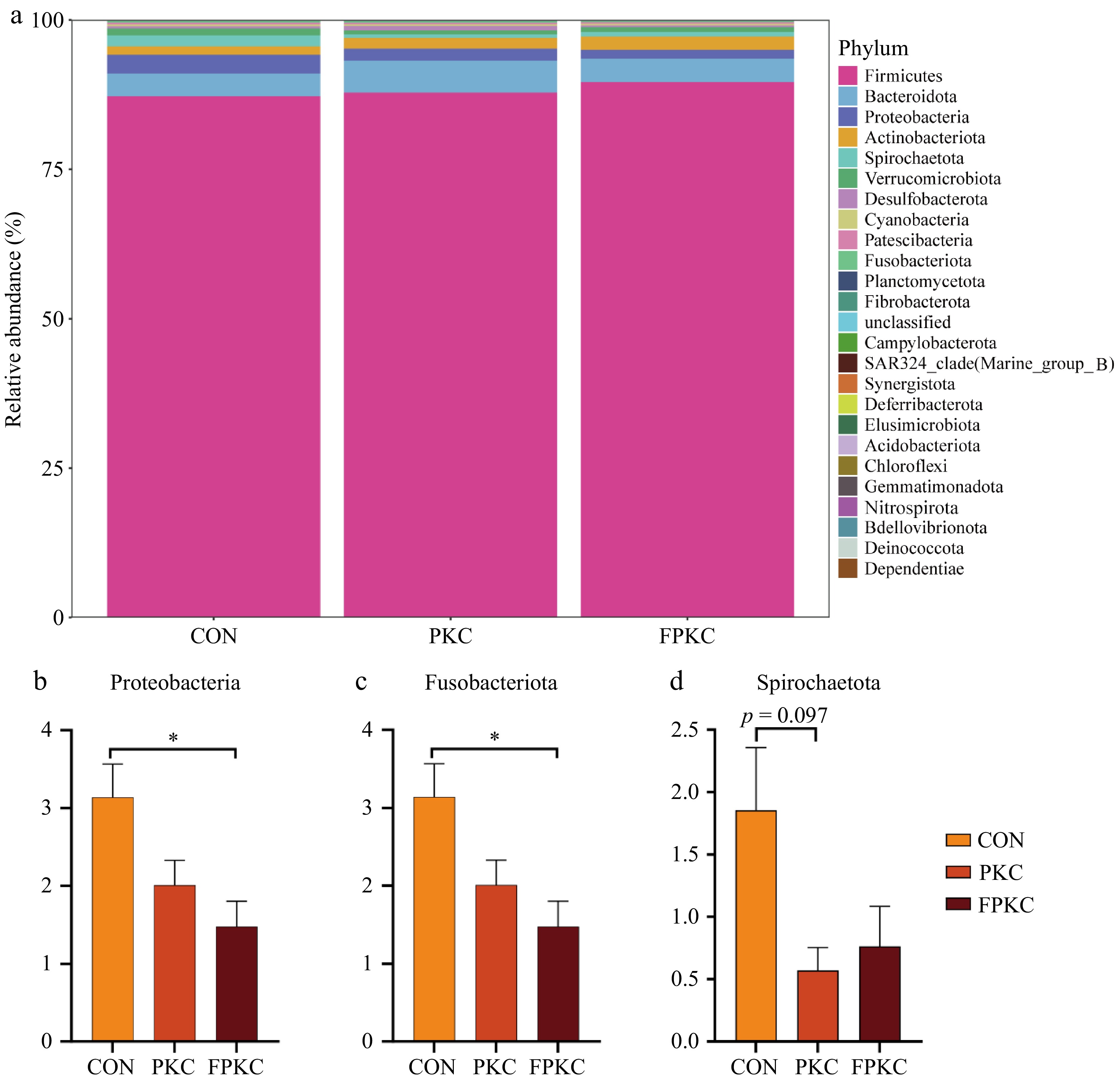

At the phylum level, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria dominated the colon of finishing pigs (Fig. 3a). The FPKC group significantly decreased the relative abundance of Proteobacteria compared to the CON group (Fig. 3b, p <0.05), but no substantial variation was found across the PKC and FPKC groups. The relative abundance of Fusobacteriota did not differ across the CON and PKC groups, but it was considerably lower in the FPKC group compared to the CON and PKC groups (Fig. 3c, p <0.05). Spirochaetota's relative abundance tended to substantially reduce in the PKC group than the CON group (Fig. 3d, p = 0.097), but it did not significantly vary from the CON group to the FPKC group.

Figure 3.

Effect of incorporating unfermented or fermented palm kernel cake into finishing pigs' diets on colonic bacteria beta diversity at phylum level (n = 6/treatment). (a) Abundance of the colonic microbe phylum level. (b)−(d) Bacteria with differences at the phylum level.

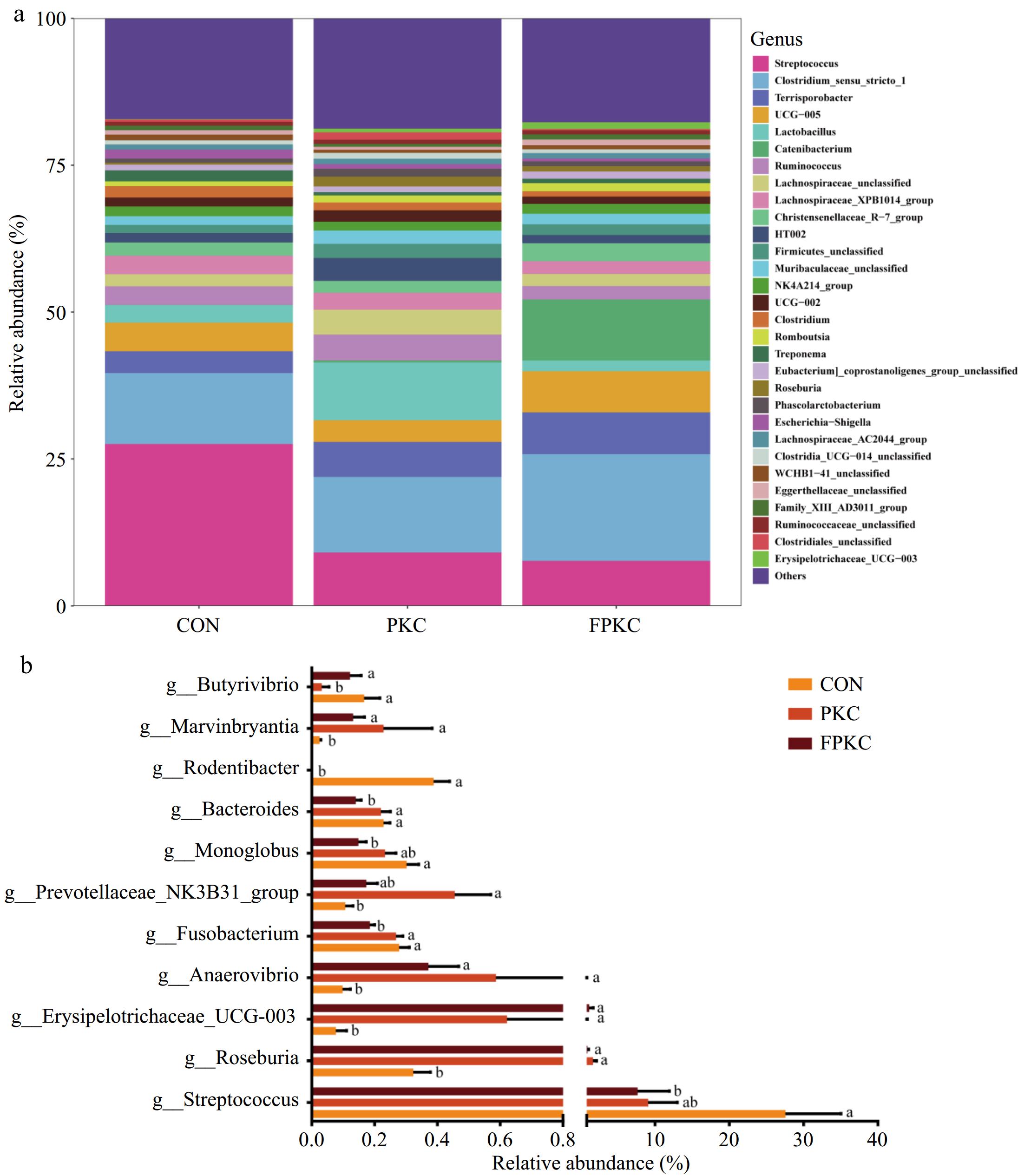

At the genus level, Streptococcus, Clostridium sensu stricto 1, Terrisporobacter, UCG-005, Lactobacillus, and Catenibacterium were the dominant genera (Fig. 4a). Figure 4b illustrates that the PKC and FPKC groups substantially improved the relative abundance of Roseburia, Erysipelotrichaceae (UCG-003), Anaerovibrio, and Marvinbryantia and reduced the relative abundance of Rodentibacter more than the CON group (p < 0.05). A comparison between the PKC group and the CON group showed that the PKC group enhanced the relative abundance of the Prevotellaceae_NK3B31_group (p < 0.05) and lowered the relative abundance of Butyrivibrio (p < 0.05). The FPKC group substantially lowered the relative abundance of Streptococcus, Fusobacterium, Monoglobus, and Bacteroides than the CON group (p < 0.05). The FPKC group decreased substantially the relative abundance of Fusobacterium and Bacteroides and enhanced the abundance of Butyrivibrio than the PKC group (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effect of incorporating unfermented or fermented palm kernel cake into finishing pigs' diet on colonic bacteria beta diversity at genus level (n = 6/treatment). (a) Abundance of the colonic microbe genus level. (b) Bacteria with differences at the genus level. a, b Mean that the different superscripts on the figure are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) concentration

-

The butyric acid and valeric acid concentrations in the PKC group were considerably higher than those in the CON group (p < 0.05), as indicated in Table 8. However, no substantial variation was found between the PKC and FPKC groups or across the CON and FPKC groups (p > 0.05). Furthermore, there were no discernible variations among the PKC, FPKC, and CON groups in terms of total short-chain fatty acids, acetic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, and isovaleric acid (p > 0.05).

Table 8. Effect of incorporating unfermented or fermented PKC into finishing pigs' diet on colonic short chain fatty acids (n = 6/treatment).

Items 1CON 2PKC 3FPKC SEM p-value Total acid (mM/L) 93.94 101.14 94.57 2.35 0.41 Acetic acid (mM/L) 56.15 53.65 52.07 1.50 0.56 Propionic acid (mM/L) 22.00 24.44 22.38 0.62 0.23 Isobutyric acid (mM/L) 2.98 3.24 3.33 0.22 0.81 Butyric acid (mM/L) 8.18b 13.80a 11.89ab 0.90 0.02 Isovaleric acid (mM/L) 2.99 3.64 3.02 0.16 0.19 Valeric acid (mM/L) 1.63b 2.37a 1.87ab 0.11 < 0.01 1 CON: control group (basal diet), 2 PKC: unfermented palm kernel cake group (contains a 30% unfermented palm kernel cake diet), 3 FPKC: fermented palm kernel cake group (contains a 30% fermented palm kernel cake diet), SEM: standard error of means. a, b Means in the same row with different superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05). -

In pig farming, growth performance is an essential factor that directly influences the benefit of farmers[19]. Our findings revealed no discernible variations in final body weight, ADG, and AFI among the PKC, FPKC, and CON groups, suggesting that feeding the pigs a diet containing either unfermented or fermented PKC did not negatively impact their growth performance. The FCR was substantially higher in the PKC group than in those in the CON and FPKC. The increase in FCR in the PKC group should be explained by the highest fiber content in unfermented PKC, which is not well converted into different nutrients needed for pigs. The pigs in the PKC group consumed more feed to meet their nutritional needs and maintain their metabolic functions. This observation is supported by the lowest apparent nutrient digestibility found in the PKC group. Furthermore, the digestibility of dry matter, total energy, crude protein, and crude fiber was lower in the PKC or FPKC groups than in the CON group, while the PKC group lowered the digestibility of dry matter and energy more than FPKC. This finding showed that the pigs might not digest well a diet containing a high level of PKC. The activity of Lactobacillus plantarum LY19, Bacillus natto NDI, and enzymatic hydrolysis during the PKC fermentation process should justify the differences in the digestibility of dry matter and energy across the PKC and FPKC. The combination of these bacteria and the hydrolysis enzyme broke down the high fiber content in PKC during fermentation. This turned the complex carbohydrates into simple sugars that are easier for pigs to digest. This finding corroborated with the previous report, which demonstrated that the pigs did not digest well a diet containing a high fiber content[20]. The increase in total bacteria counts after fermentation should also be explained by the decrease in the crude fiber observed in the FPKC, as well as the bacteria using the crude fiber to grow and multiply. Moreover, the source of energy provided to finishing pigs during our feed formulation among the treatments, particularly the crude fat content, might also be another factor that has influenced the apparent digestibility of nutrients.

In pigs, the serum biochemical parameters can reflect their health status and dietary metabolism[21]. The TP, ALB, and GLB are not only relevant indicators that reflect the immune status but also reflect the utilization of proteins in the body[22]. Our findings revealed a significant decrease in TP and GLB in the PKC group, suggesting that feeding pigs a diet containing 30% unfermented PKC reduced their body's protein utilization. Despite the significant differences across the PKC and the CON groups in TP and GLB, their values remained in the normal range for pigs, which would not cause any problem in their life. ALT and AST are the most important indicators of liver function[23]. The results showed no noteworthy differences in serum AST and ALT among treatments, suggesting that the incorporation of either unfermented or fermented PKC into finishing pigs' diets did not cause any effect on their liver function. TG and TC are indicators reflecting the body's lipid metabolism[24]. Our findings showed that TG and TC levels dropped significantly in the FPKC group, while GLU levels rose. This suggests that FPKC decreased the buildup of fat in the bodies of finishing pigs, which is in line with previous research[25]. However, despite the concentration variability in some parameters, the concentrations of all serum biochemical variables tested were within normal ranges for pigs, indicating no impact on the pigs' life status.

In pigs, the role of intestinal morphology and tight junction is crucial to ensure the normal digestion and absorption of nutrients[26]. Our findings showed that the PKC group substantially decreased the jejunum villi height and villi/crypt ratio (VCR) value compared to the CON group, while the FPKC group had no noteworthy effect on villus height and VCR value compared to the CON group. This indicated that feeding the pigs with a diet incorporating unfermented PKC decreased the area of nutrient digestion and absorption, resulting in the lowest nutrient digestibility and absorption. This finding corroborated with the previous study, which reported that the high levels of β-mannans content in PKC could lead to poor palatability of feed containing PKC, resulting in decreased intestinal morphology, nutrient digestibility, and absorption, thus limiting the PKC's incorporation into the pig's diet[6,27]. The VCR was substantially higher in the FPKC group than in the PKC group, showing that the FPKC group significantly improved the intestinal morphology and function compared with the PKC group. The damage of some intestinal villi might be caused by long-term feeding of powder, which corroborated with the previous study indicating that the long-term feeding of powder affected the intestinal development of fattening pigs and caused the shedding of intestinal villi[28]. In pigs, CLAUDIN-1, OCCLUDIN, and ZO-1 are essential proteins for maintaining intestinal barrier integrity and nutrient permeability[29,30]. Our experiment showed that neither PKC nor FPKC had a big effect on the levels of CLAUDIN-1, OCCLUDIN, and ZO-1 mRNA gene expression in the finishing pigs' jejunum than those in the CON group. This demonstrated that feeding the pigs a diet containing unfermented or fermented PKC did not impact the intestinal barrier function or nutrient permeability in the finishing pigs.

The digestive system secretes digestive enzymes in pigs, which are crucial for appropriate nutrient digestion[31]. A comparison between the PKC group and the CON group showed that the PKC group substantially reduced the activities of α-amylase, sucrase, trypsin, and chymotrypsin in the pigs' jejunum. However, there were no discernible variations across the CON and FPKC groups. The unfermented PKC (PKC group) had a lot of fiber, which may explain why the enzyme activities were different. On the other hand, the fermented PKC (FPKC group) had less fiber, which made more nutrients available. The PKC group's lowest digestibility, consistent with a previous report demonstrating a stronger relation between digestive enzyme activity and nutrient absorption, supported this observation[6]. The high amount of crude fat in PKC during our feed formulation should explain why the lipase enzyme activity was much higher in the PKC and FPKC groups in comparison to the CON group.

In pigs, the gut microbiota has a potential effect on the host's health and intestinal homeostasis[32]. Our findings showed that there was no noteworthy distinction in α-diversity among the CON, PKC, and FPKC groups. This means that giving pigs a diet that included either unfermented or fermented PKC did not change the number of colonic bacteria or their diversity. The PCoA showed a trend of significant separation between the CON group and the PKC or FPKC groups, but no discernible differentiation across the PKC and FPKC groups was observed. The reason for this difference should be the highest fiber content in the PKC and FPKC groups provided in our feed formulation, which might affect the colonic bacteria population involved in fiber degradation. Our experiment showed that Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes made up most of the pigs' colonic microbiota at the phylum level across all treatments. There is a similarity between our finding and other studies, which have found that Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes dominated in the pigs' colonic bacteria, and they are important for breaking down dietary fiber[33,34]. Compared to the CON and PKC groups, the FPKC group significantly reduced the abundance of Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria, demonstrating its ability to regulate the intestinal microecological balance. Studies have demonstrated that Fusobacterium and Proteobacteria serve as indicators of intestinal microflora imbalance and have a close relationship with inflammation[35,36]. At the genus level, our findings showed that feeding the pigs a diet incorporating 30% PKC or FPKC increased the relative abundance of Roseburia, Erysipelotrichaceae-UCG-003, Anaerovibrio, Marvinbryantia, and Prevotellaceae-NK3B31-group. These bacteria, except Erysipelotrichaceae (UCG-003), are all associated with dietary fiber degradation and SCFA production. Roseburia and Prevotellaceae-NK3B31-group are able to degrade the dietary fiber and produce SCFA. Roseburia mainly produces butyrate, while the Prevotellaceae-NK3B31-group mainly produces propionate[37,38]. Erysipelotrichaceae-UCG-003 has effects on cholesterol and lipid metabolism in the gastrointestinal tract, but the functional role of the UCG-003 isoform has not been reported[39]. Anaerovibrio is a bacterium in the gut that can degrade lipids[40], and its increase in relative abundance might be caused by the increase in lipids in the PKC and FPKC groups. Furthermore, the Marvinbryantia genus is classified as Clostridium cluster XIVa and is positively associated with energy metabolism and butyrate production in intestinal epithelial cells[41]. The decrease in the relative abundance of Streptococcus and Rodentibacter in the PKC and FPKC groups than the CON group indicates that, during the fiber degradation, the microbiota produced the SCFA, resulting in lower pH in the colonic environment, thereby inhibiting the growth of potentially pathogenic bacteria such as Streptococcus and Rodentibacter. Furthermore, FPKC lowered the relative abundance of Fusobacterium, Monoglobus, and Bacteroides. Monoglobus secretes pectase and degrades pectin[42]. According to Tingirikari[43], Bacteroides are the primary carbohydrate-degrading bacteria in the gut, playing a role in the breakdown of complex pectin. Most of the pectin in the PKC was broken down during fermentation, which may explain why there were fewer Monoglobus and Bacteriodes in the FPKC group. It has been suggested that Fusobacterium is associated with intestinal diseases in pigs[44]. The above results show that FPKC can inhibit the growth of colonic bacteria and reduce the incidence of colonic diseases.

Microbial fermentation produces SCFA, which has specific impacts on host metabolism and immunological modulation[45]. Previous research has demonstrated that dietary fiber significantly impacts the synthesis and absorption of SCFA[46]. Although there was no discernible difference between the PKC and FPKC groups or the CON and FPKC groups, our findings revealed that the PKC group considerably raised the butyric acid and valeric acid concentrations compared to those in the CON group. The colonic bacteria in the PKC group, specifically the Roseburia, Anaerovibrio, Marvinbryantia, and Prevotellaceae-NK3B31-group, may explain these variations in butyric acid and valeric acid concentrations. The diverse fiber source in our feed formulation, particularly the PKC group with the highest fiber concentration, may influence the relative abundance of various bacteria involved in fiber degradation.

Given that the cost of the CON group was higher than that of the CON or the PKC groups, our findings suggest that both unfermented and fermented PKC could serve as potential alternatives to the scarcity of corn and soybean meal used in the pig industry.

-

Throughout the fermentation process, Lactobacillus plantarum L19 and Bacillus natto NDI combined with hydrolysis enzymes improved the PKC's nutritional values. Feeding the finishing pigs a diet incorporating unfermented or fermented PKC did not impact their final body weight, ADG, ADFI, or tight junction proteins, and their lives were not affected (all biochemical variables were in the normal range). Unfermented PKC lowered from the CON group the levels of nutrient digestibility, feed conversion ratio, digestive enzyme activity, and intestinal morphology. It also increased the activity of microbiota in the colon that breaks down fiber, which led to higher levels of butyric acid and valeric acid. However, fermented PKC did not significantly differ from the CON group in most of the parameters (growth performance, digestive enzyme activity, short-chain fatty acids, intestinal morphology, tight junction, and most biochemical variables) that were tested in this study and showed a better improvement than unfermented PKC. According to the findings, both fermented and unfermented PKC could substitute for corn and soybeans in pigs' feed. Based on our findings and the feed cost, fermented or unfermented PKC could be suggested to farmers as a better alternative to the lack of the main feedstock material used in pig farming, but FPKC is more suitable for utilization in finishing pigs.

This study is supported by a grant from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2021YFD1300301-5).

-

All procedures were reviewed and preapproved by the Nanjing Agricultural University's Animal Ethics Committee, (Identification No. 20221005N11), approval date: October 5th 2022. The research followed the 'Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement' principles to minimize harm to animals. This article provides details on the housing conditions, care, and pain management for the animals, ensuring that the impact on the animals was minimized during the experiment.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition: Hang S; data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, writing—original draft preparation: Liao J, Daniel S; software: Miao J, Liu Z; writing—review and editing: Hang S, Liao J; investigation: Cao X, Ni J, Deng W, Sui Z. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Jinghong Liao, Sindaye Daniel

- Supplementary Table S1 Comparison of nutrient composition between unfermented palm kernel cake and fermented palm kernel cake.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liao J, Daniel S, Miao J, Liu Z, Cao X, et al. 2025. Finishing pig's responses to a diet incorporating unfermented or fermented palm kernel cake on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, digestive enzyme activity, short-chain fatty acid, and colonic microbiota composition. Animal Advances 2: e013 doi: 10.48130/animadv-0025-0012

Finishing pig's responses to a diet incorporating unfermented or fermented palm kernel cake on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, digestive enzyme activity, short-chain fatty acid, and colonic microbiota composition

- Received: 12 January 2025

- Revised: 17 March 2025

- Accepted: 19 March 2025

- Published online: 15 May 2025

Abstract: This study evaluated the effect of feeding finishing pigs a diet incorporating unfermented or fermented palm kernel cake (PKC) on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, digestive enzyme activity, short-chain fatty acid, and colonic microbiota composition. A total of 24 finishing pigs (5-month-old fattening castrated Duroc × Landrace × Large White pigs) were divided into three groups, namely, the control group (CON), unfermented palm kernel cake group (PKC group), and fermented palm kernel cake group (FPKC group), with eight replicates in each group and one finishing pig in each replicate. The CON group fed the finishing pigs a basal diet, while the PKC and the FPKC groups substituted 30% of the basal diet with either unfermented PKC or fermented PKC. The results showed that an unfermented or fermented PKC diet did not impact the pig's final body weight, average daily gain (ADG), average daily feed intake (ADFI), and tight junction proteins. Unfermented PKC had lower nutrient digestibility, feed conversion ratio, digestive enzyme activity, and intestinal morphology, and increased the activity of microbiota in the colon that breaks down fiber, resulting in an increase of butyric acid and valeric acid compared with the CON group (P < 0.05). However, fermented PKC did not significantly differ from the CON group in most of the parameters (growth performance, digestive enzyme activity, short-chain fatty acids, intestinal morphology, tight junction, and most biochemical variables) that were tested in this study and showed a better improvement than unfermented PKC. Based on our findings (final body weight, colonic bacteria composition, and diversity) and the feed cost, fermented or unfermented PKC could be suggested to farmers as a better alternative to the lack of the main feedstock material used in pig farming, but FPKC is more suitable for utilization in finishing pigs.

-

Key words:

- Palm kernel cake /

- Finishing pig /

- Growth performance /

- Digestive enzyme activity /

- Colonic microbiota